Abstract

Introduction

Asbestos-related diseases and cancers represent a major public health concern.

Objective

To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to demonstrate that asbestos exposure increases the risk of prostate cancer.

Methods

The PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, and ScienceDirect databases were searched using the keywords (prostate cancer OR prostatic neoplasm) AND (asbestos* OR crocidolite* OR chrysotile* OR amphibole* OR amosite*). To be included, articles needed to describe our primary outcome: Risk of prostate cancer after any asbestos exposure.

Results

We included 33 studies with 15,687 cases of prostate cancer among 723,566 individuals. Asbestos exposure increased the risk of prostate cancer (effect size = 1.10, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.05–1.15). When we considered mode of absorption, respiratory inhalation increased the risk of prostate cancer (1.10, 95% CI = 1.05–1.14). Both environmental and occupational exposure increased the risk of prostate cancer (1.25, 95% CI = 1.01–1.48; and 1.07, 1.04–1.10, respectively). For type of fibers, the amosite group had an increased risk of prostate cancer (1.12, 95% CI = 1.05–1.19), and there were no significant results for the chrysotile/crocidolite group. The risk was higher in Europe (1.12, 95% CI = 1.05–1.19), without significant results in other continents.

Discussion

Asbestos exposure seems to increase prostate cancer risk. The main mechanism of absorption was respiratory. Both environmental and occupational asbestos exposure were linked to increased risk of prostate cancer.

Conclusion

Patients who were exposed to asbestos should possibly be encouraged to complete more frequent prostate cancer screening.

Keywords: amosite, asbestos, chrysolite, crocidolite, environmental asbestos exposure, occupational asbestos exposure, prostate cancer, work asbestos exposure

INTRODUCTION

Asbestos is a major occupational risk factor for workers, because it causes various asbestos-related cancers such as lung, laryngeal, and ovarian cancers, and pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma.1 However, the influence of asbestos exposure on the risk of prostate cancer is still under debate.2,3 Prostate cancer is the most frequent cancer in men in France4 and the second most common in the world5; therefore, the influence of asbestos exposure on prostate cancer is a public health issue. Most studies demonstrate an increased risk of asbestos-related diseases owing to respiratory exposure.6,7 Regarding oral ingestion of asbestos, animal studies have failed to demonstrate an increased risk,8 whereas results of human studies suggest an increased risk of some cancers after drinking asbestos-contaminated water.9,10 For prostate cancer, some studies demonstrated a particular risk both after respiratory11,12 and oral ingestion of specific agents,13–15 but comparisons between modes of absorption of asbestos on the risk of prostate cancer were never investigated. Last, even in countries prohibiting asbestos, asbestos remains widespread at workplaces and in public spaces. For example, some studies stated that nonoccupational exposure is the main cause of some asbestos-related cancers.16 Therefore, the influence of the type of asbestos exposure (occupational or environmental) on prostate cancer also needs to be further investigated.

In view of these elements, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate whether asbestos exposure increases the risk of prostate cancer. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the influence of the mode of absorption (respiratory or oral ingestion), the type of exposure (occupational or environmental), and other factors such as occupational role,17 use of personal protective equipment,18 quantification of asbestos exposure,7 type of asbestos fibers,19 or country.20,21

METHODS

Literature Search

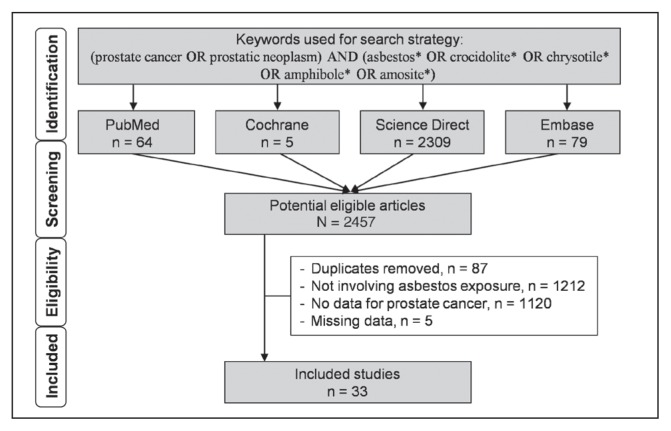

We reviewed all published studies involving asbestos exposure, professional or not, and prostate cancer incidence and/or mortality. The inclusion criterion for the search strategy was asbestos exposure. For the literature search, we used the following keywords: (prostate cancer OR prostatic neoplasm) AND (asbestos* OR crocidolite* OR chrysotile* OR amphibole* OR amosite*). The following databases were searched on September 1, 2019: PubMed, Cochrane Library, ScienceDirect, and Embase. The search was not limited to specific years, and no language restrictions applied. To be included, articles needed to describe our primary outcome: Risk of prostate cancer after asbestos exposure. More specifically, we included all articles with data on incidence of, or mortality from, prostate cancer, or articles with crude data allowing such calculation. In addition, reference lists of all publications meeting the inclusion criteria were manually searched to identify any further studies not found through electronic searching. The search strategy is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Search strategy.

Four authors (LZ-C, VN, FD, and MM) separately conducted all literature searches, collated and reviewed the abstracts, and, on the basis of the selection criteria, decided the suitability of the articles for inclusion. A fifth author (BP) was asked to review the articles when consensus on suitability was debated. Then all authors reviewed the eligible articles.

Quality of Assessment

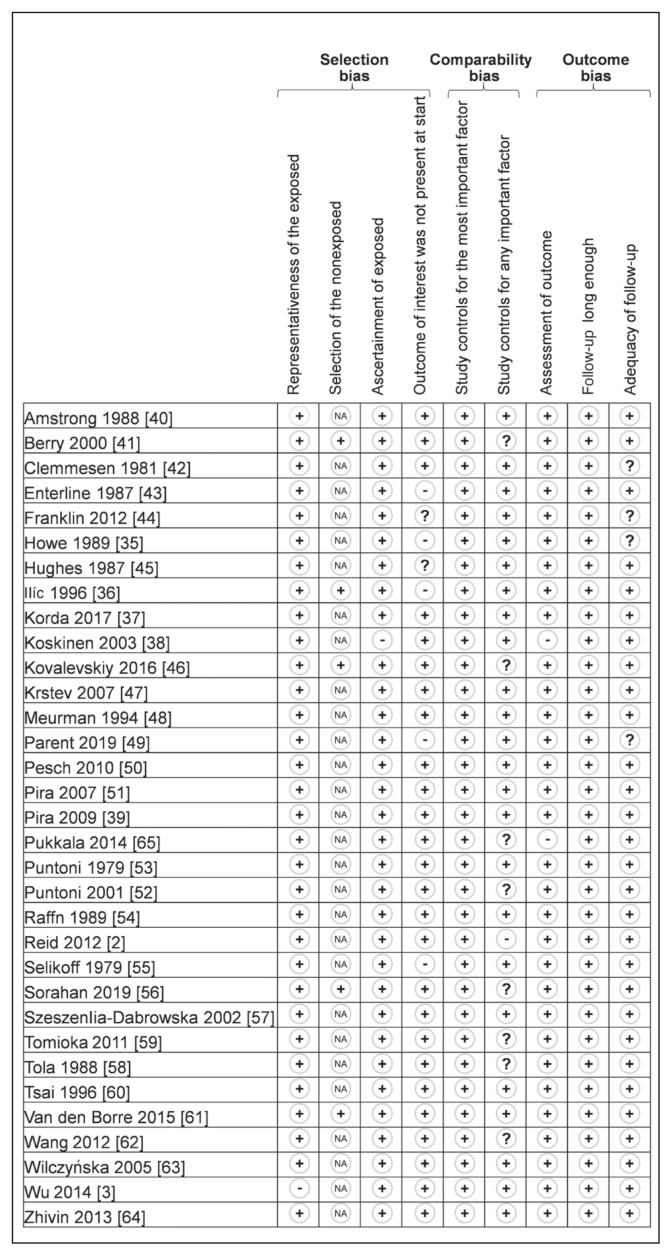

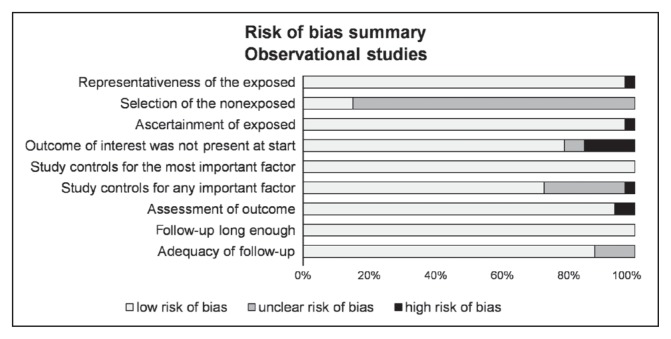

Although not designed for quantifying the integrity of studies,22 the “STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology” (STROBE) criteria were used for checking the quality of reporting.23 The 22 items identified in the STROBE criteria were evaluated for a maximal score of 34 for each study. The methodologic quality of the studies was further evaluated by 3 authors (LZ-C, VN, and FD) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale model.24 The following 9 items were assessed in all cohort studies: 4 items on selection bias (representativeness of the exposed, selection of the nonexposed cohort, ascertainment of exposed, outcome of interest was not present at start), 2 items on comparability bias (design and analysis), and 3 items on outcome bias (assessment of outcome, longer follow-up, and adequacy of follow-up). Similar items were used to evaluate case-control studies. Each item was assigned a judgment of “yes,” “no,” “cannot say,” or “not applicable.” Disagreements were addressed by obtaining a consensus with a third author (BP), shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Methodologic quality of included articles using Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale.a

a The articles by Reid2 and Wang62 were published initally online in 2012 and in print in 2013.

+ = yes; − = no; ? = cannot say; NA = not applicable.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias of included articles using Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using software (Stata version 13, StataCorp, College Station, TX).7,25–31 Characteristics of asbestos exposure, prostate cancer, individuals, or other variables were summarized for each study sample and reported as mean (standard deviation [SD]) and number (percent) for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Heterogeneity in the study results was evaluated by examining forest plots, determining confidence intervals (CIs), and using formal tests for homogeneity based on the I2 statistic, which is the most common metric for measuring the magnitude of between-study heterogeneity and is easily interpretable. The I2 values range between 0% and 100% and are typically considered low for less than 25%, modest for 25% to 50%, and high for more than 50%. This statistical method generally assumes heterogeneity when the p value of the I2 test is less than 0.05. For example, a significant heterogeneity may be caused by the variability between the characteristics of the studies, such as the mode of absorption of asbestos (respiratory or oral ingestion), the type of exposure (occupational or environmental), characteristics of individuals (age, sex, etc), or type of statistics retrieved in the included articles (odds ratio [OR], standardized incidence ratio [SIR], standardized mortality ratio [SMR], standardized rate ratio [SRR], and hazard ratio [HR]). Random-effects meta-analyses (DerSimonian and Laird approach) were conducted when data could be pooled.32 All p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

We conducted meta-analyses on the risk of prostate cancer after asbestos exposure. We stratified these meta-analyses on the mode of absorption of asbestos (respiratory or oral ingestion), the type of exposure (occupational or environmental), type of fibers (amosite and others, chrysotile/crocidolite and nonspecified), type of risk (SMR, SIR, SRR, and HR), and by continent (Europe, North America, Asia, and Oceania). When data were pooled, results were expressed as effect size (ES) of the risk of prostate cancer after asbestos exposure.32 An ES is defined as a unitless measure of the effects of asbestos exposure on the risk of prostate cancer centered at 1. An ES greater than 1 denoted an increased risk.33 For thoroughness, funnel plots of these meta-analyses were used to search for potential publication bias.

To verify the strength of the results, we conducted further meta-analyses, excluding studies that were not evenly distributed around the base of the funnel.34 We further performed a meta-analysis excluding studies with multiple exposures for sensitivity analysis. When possible (sufficient sample size), meta-regressions were proposed to study the relationship between the risk of prostate cancer after asbestos exposure and putatively to explain variables such as characteristics of the population (sex, age, etc),1 working or environmental characteristics,7 or details on asbestos exposure. Results were expressed as regression coefficients and 95% CI.

RESULTS

An initial search produced 2457 articles (Figure 1). Removal of duplicates (n = 87) and application of selection criteria (1212 studies did not involve asbestos exposure, 1120 studies did not report data on prostate cancer, and 5 studies had missing data) reduced these articles to 33 studies.2,3,35–65 All identified articles were written in English.

Quality of Articles

Quality assessment of the 33 included studies, as outlined by the STROBE criteria, varied from 70.644,49,55,64 to 97%,37 with a mean (SD) score of 81.8 (7.94). Overall, the studies performed best for quality in their discussion section and worst in the methods section. With use of the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale models, included studies varied from 6735,49 to 100%,61 with a mean (SD) score of 82.5 (8.79). Detailed characteristics of methodologic quality assessment of each included study are available in Figures 2 and 3.

Inclusion Criteria for Asbestos Exposure

Asbestos exposure was the shared inclusion criterion of the 33 studies.2,3,35–65 Eligibility for asbestos exposure varied: asbestos in drinking water,35 residential airborne exposure,2,37,44,49 and work exposure.a Studies without estimation of durationb or quantityc of asbestos exposure were also included.

Population

Population sizes ranged from 10136 to 1,033,869.37 In total 1,282,066 individuals were included in this meta-analysis.

Regardless of whether age was expressed as a median or a mean value, only 7 studies2,36–38,44,50,57,62 reported age. The age of individuals ranged from 40 years62 to 70.5 years.36 Fifteen studies included only men.d A total of 723,566 men were included in this meta-analysis, ranging from 10136 to 504,660.37 Ten studies reported data on smokinge; no studies reported on alcohol or gave adjusted results taking into account those parameters (Table 1, available online at: www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2020/19.086Table1.pdf).

Asbestos Exposure

Mode of Absorption

A total of 32 studies concerned respiratory inhalation,2,3,36–65 and 1 study concerned oral ingestion from drinking asbestos-contaminated water35 (Table 1, available online at: www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2020/19.086Table1.pdf).

Type and Quantification of Exposure

Twenty-eight studies concerned work exposure,3,36,38–43,45–48,50–65 and 5 studies concerned environmental exposure.2,35,37,44,49 Seven studies were linked with an asbestos mine: 5 on miners (occupational exposure)39,40,46,48,51 and 2 on adults who had an environmental asbestos exposure during childhood by living near a crocidolite mine.2,44 The other studies on occupational asbestos exposure included shipbreaking and shipyards workers,3,38,47,52,53,58,59 workers from the construction industry and asbestos industry,38,45,50,51,54–57,60–64 and firefighters,65 and occupation was unspecified in 1 study.36 The 3 last studies with environmental exposure were on individuals exposed to drinking asbestos-contaminated water35 and individuals with a residential exposure to asbestos insulation37,49 (Table 1, available online at: www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2020/19.086Table1.pdf).

Twelve studies estimated asbestos exposure from measurements on-site.f However, the method of estimation and units of estimation differed between studies: Number of fibers per milliliter of air per year,2,48,50,54,55,57,62 fiber-years,39,40 millions of fibers per liter of water,35 and a unitless number categorizing asbestos exposure.3,51 Therefore, the heterogeneity of quantification of asbestos exposure precluded further analysis.

Type of Asbestos

Twenty-six studies reported type of asbestos: Amosite and others fibers in 15 studies,g chrysotile/crocidolite in 12 studies,h anthophyllite in 1 study,48 and nonspecified in 7 studies3,36,38,56,57,59,64 (Table 1, available online at: www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2020/19.086Table1.pdf).

Country of Exposure

As shown in Table 1 (available online at: www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2020/19.086Table1.pdf), a total of 18 studies were in Europe (Belgium,61 Denmark,42,54 Finland,38,48,58,65 France,64 Germany,50 Italy,39,51–53 Poland,57,63 Serbia,36 and the UK41,56), 4 studies were in Asia (China,3,62 Japan,59 and Russia46), 7 studies were in North America (Canada49,55 and US35,43,45,47,55,60), and 4 studies were in Oceania (Australia2,37,40,4).

Chronology or Duration of Exposure

The date of the beginning of exposure was retrieved in 18 studiesi and ranged from 192045 to 1980.37 However, duration of exposure was retrieved in only 2 studies as a mean38 or a median.2 Similarly, periods of exposure was retrieved in only 11 studiesj and covered a long period without further details: From 20 years (1946–1966)2 to 45 years (1930–1975).39 Therefore, meta-regressions were possible only on the basis of the date of beginning exposure.

Outcome and Aim of Studies

Nine studies shared similar outcomes: To evaluate the incidence of several cancers after any asbestos exposure.3,3,35,37,38,44,48,58,65 Twenty-four studies evaluated mortality from cancer, and 1 other evaluated both incidence and mortality from cancer after asbestos exposure.k One study aimed to determinate risk factors for prostate cancer, inter alia, and specific occupational exposure as asbestos.36

Study Designs and Other Exposure

Thirty-two studies described a cohort follow-up design, analysing incidence and/or mortality of all cancer in population exposed,2,3,35,37–65 and also giving results for prostate cancer. One was a case-control study of risk factors for prostate cancer, with 1 variable consisting of a broad category of occupational exposures without focusing only on asbestos.36 Eighteen studies described an exposure to multiple agents without focusing only on asbestos exposurel (Table 1, available online at: www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2020/19.086Table1.pdf).

Incidence of Prostate Cancer

Among 723,566 male participants, 15,687 cases of prostate cancer were diagnosed. Results were expressed with SIR in 9 studies,2,3,35,37,38,44,48,58,65 ranging from 0.703 to 2.4744; with SMR in 19 studiesm; with SRR in 1 study56; and with HR in 1 study.3 Eight studies found an increased risk of prostate cancer,35,37,38,44,55–57,65 with a risk from 1.06 (95% CI = 1.02–1.09)56 to 2.91 (95% CI = 1.26–5.73).57 Twenty-five studies did not retrieve an increased risk of prostate cancer,2,3,36,38–43,45–54,58–63 with a nonsignificant risk from 0.70 (95% CI = 0.23–1.63)41 to 2.56 (95% CI = 0.06–14.27).59

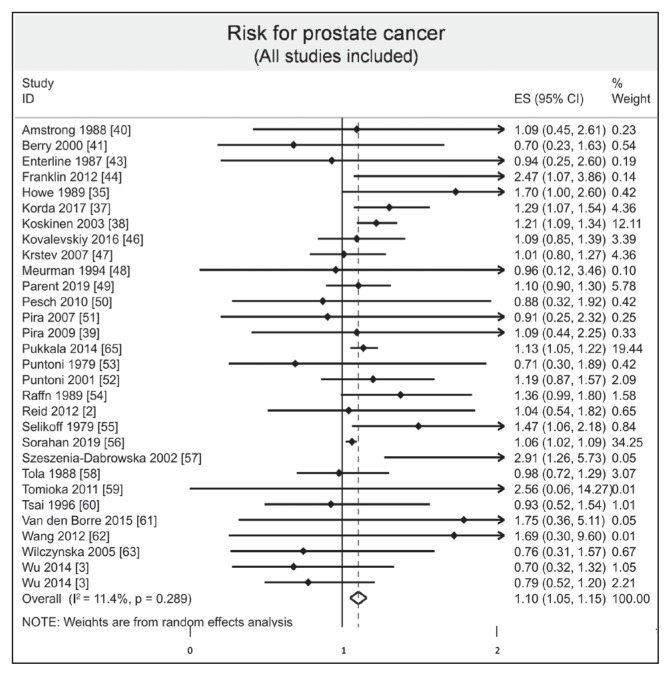

Meta-Analysis

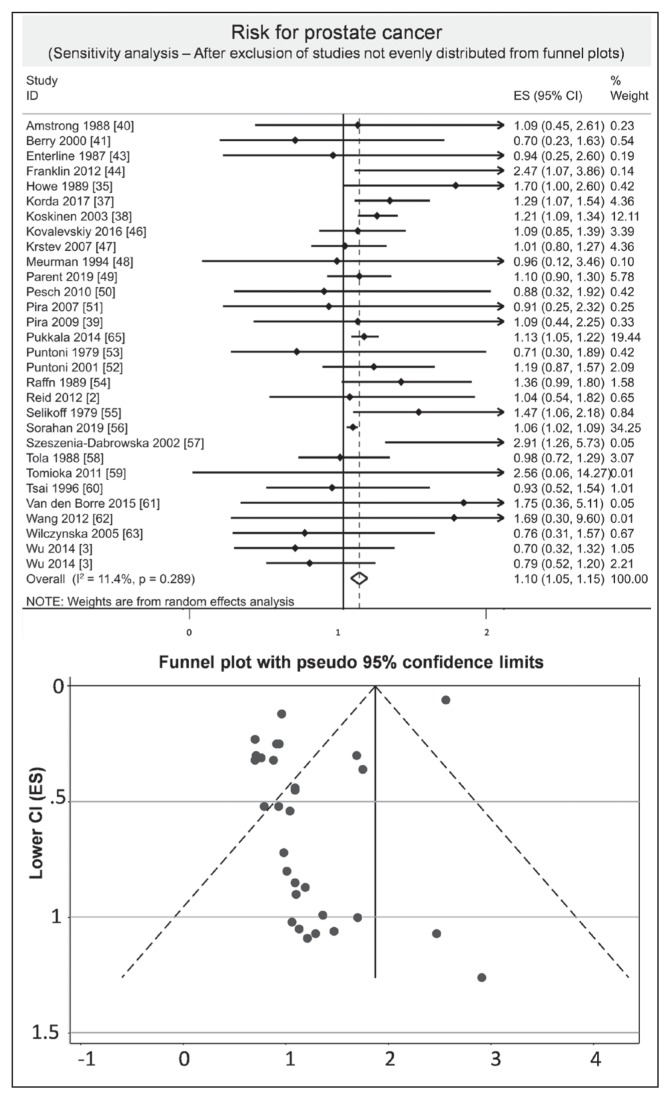

We included 30 studies.2,3,35–41,43,44,46–63,65 The overall result of the meta-analysis including all the studies was that asbestos exposure could possibly increase the risk of prostate cancer (ES = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.05–1.15, I2 = 11.4%; Figure 4). After exclusion of studies not evenly distributed from funnel plots, we found an overall risk of 1.12 (95% CI = 1.07–1.18, I2 = 20.9%; Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of risk of prostate cancer after asbestos exposure.a

a Each horizontal black line represents the 95% confidence interval for the risk (represented by small solid diamond) of prostate cancer of each individual study. Open diamond represents overall risk (result of meta-analysis) considering all included studies. The articles by Reid2 and Wang62 were published initally online in 2012 and in print in 2013.

CI = confidence interval; ES = effect size; ID = identification.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis of prostate cancer risk after exclusion of studies out of funnel plot.a

a Each horizontal black line represents the 95% confidence interval for the risk (represented by small solid diamond) of prostate cancer of each individual study. Open diamond represents overall risk (result of meta-analysis) considering all included studies. The articles by Reid2 and Wang62 were published initally online in 2012 and in print in 2013.

CI = confidence interval; ES = effect size; ID = identification.

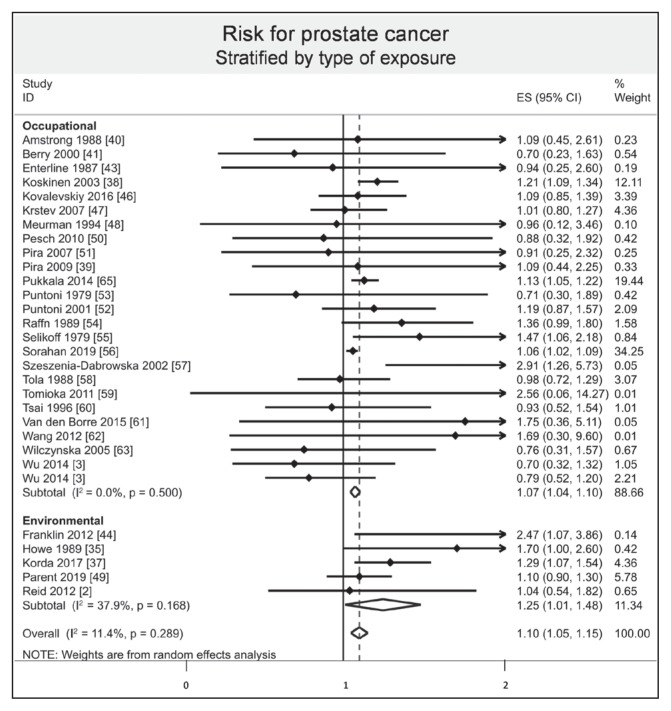

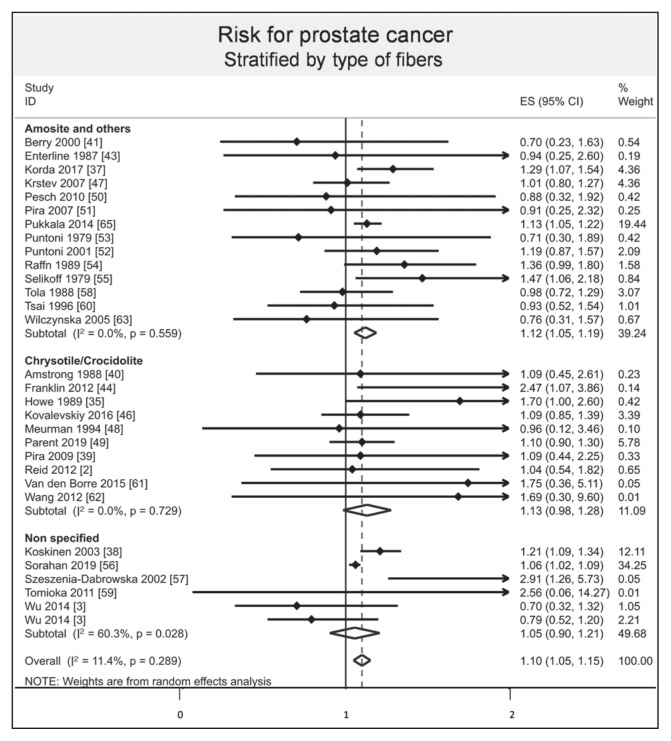

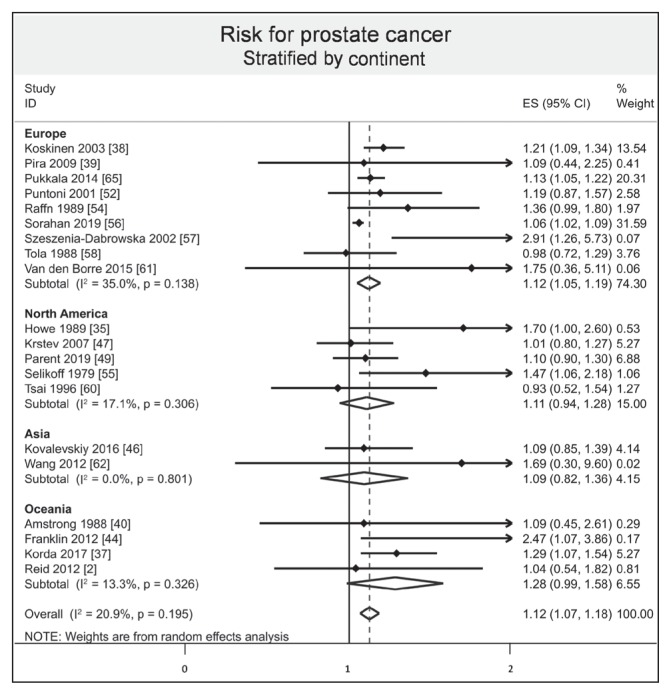

Stratified results by mode of absorption demonstrated an increased risk of prostate cancer by respiratory inhalation (ES = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.05–1.15, I2 = 7.90%), whereas there was no evidence of an increased risk of prostate cancer by oral ingestion (ES = 1.70, 95% CI = 0.90–2.50). Stratified results by type of exposure demonstrated that both environmental and occupational exposure slightly increased the risk of prostate cancer (ES = 1.25, 95% CI = 1.01–1.48, I2 = 37.9%; and 1.07, 1.04–1.10, I2 = 0.0%, respectively; Figure 6). Stratified results by type of fibers demonstrated an increased risk of prostate cancer with the amosite group (ES = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.05–1.19, I2 = 0.0%), whereas there was no evidence of an increased risk with chrysotile/crocidolite and nonspecified groups (ES = 1.13, 95% CI = 0.98–1.28, I2 = 0.0%; and 1.05, 0.90–1.21, I2 = 60.3%, respectively; Figure 7). Stratification by continent demonstrated an increased risk of prostate cancer in Europe (ES = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.05–1.19, I2 = 35.0%), whereas there was no evidence of an increased risk in North America, Asia, and Oceania (ES = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.94–1.28, I2 = 17.1%; 1.09, 0.82–1.36, I2 = 0.0%; and 1.28, 0.99–1.58, I2 = 13.3%, respectively; Figure 8). Stratified results by type of risk demonstrated an increased risk of prostate cancer with SIR (ES = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.04–1.27, I2 = 35.2%) and with SRR (ES = 1.06, 95% CI = 1.04–1.27), whereas there was no evidence of an increased risk with SMR and HR (ES = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.98–1.19, I2 = 0.0%; and 0.79, 0.45 to 1.13, respectively).

Figure 6.

Risk of prostate cancer after asbestos exposure, stratified by type of exposure.a

a Each horizontal black line represents the 95% confidence interval for the risk (represented by small solid diamond) of prostate cancer of each individual study. Open diamond represents overall risk (result of meta-analysis) considering all included studies. The articles by Reid2 and Wang62 were published initally online in 2012 and in print in 2013.

CI = confidence interval; ES = effect size; ID = identification.

Figure 7.

Risk of prostate cancer after asbestos exposure, stratified by type of fibers.a

a Each horizontal black line represents the 95% confidence interval for the risk (represented by small black diamond) of prostate cancer of each individual study. Blue diamond represents overall risk (result of meta-analysis) considering all included studies. The articles by Reid2 and Wang62 were published initally online in 2012 and in print in 2013.

CI = confidence interval; ES = effect size; ID = identification.

Figure 8.

Risk of prostate cancer after asbestos exposure, stratified by continent.a

a Each horizontal black line represents the 95% confidence interval for the risk (represented by small solid diamond) of prostate cancer of each individual study. Open diamond represents overall risk (result of meta-analysis) considering all included studies. The articles by Reid2 and Wang62 were published initally online in 2012 and in print in 2013.

CI = confidence interval; ES = effect size; ID = identification.

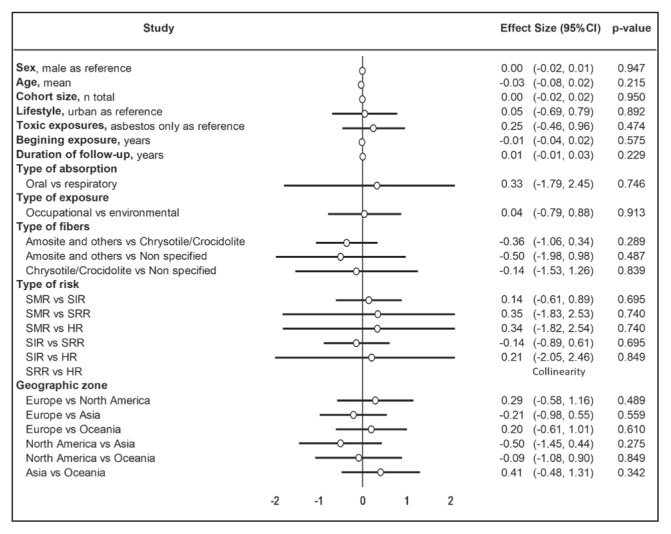

We performed a sensitivity analysis by stratifying results and, after exclusion of studies out of the funnel plot, the meta-analysis demonstrated similar results. We then conducted a meta-regression including sex, age, cohort size, lifestyle, toxic exposures, duration of follow-up, type of absorption, type of exposure, type of fibers, type of risk, and geographic zone. They did not influence the risk of prostate cancer (Figure 9). Insufficient data on quantity and during of exposure as well as use of personal protective equipment precluded further analysis.

Figure 9.

Meta-regression.

CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; SIR = standardized incidence ratio; SMR = standardized mortality ratio; SRR = standardized rate ratio.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study was that asbestos exposure could potentially lead to an increased risk of prostate cancer; however, prospective studies are warranted to confirm this finding. The main mode of asbestos absorption was respiratory, whereas oral ingestion was not found to be statistically significant. Both occupational and environmental exposures increased the risk of prostate cancer. We demonstrated that the risk remained prevalent in Europe and did not decrease over time.

Asbestos Exposure and Increased Risk of Prostate Cancer

In 2012, the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization classified all types of asbestos causing lung, laryngeal, and ovarian cancers, and pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma, and possibly other cancers and diseases.6 Our results suggest that asbestos exposure also may increase the risk of prostate cancer. Screening prostate cancer at an early stage is commonly done by the measurement of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA)66; however, screening remains controversial because of overdiagnosis (up to 40%–50%) and adverse effects of overtreatment.67–69 Indeed, no country has yet introduced a national PSA-based screening program.70 Two recent studies have contradictory results. Results of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer show a relative reduction of mortality of 21% after 13 years of follow-up.71 In the US, the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian screening trial concluded an absence of benefit on mortality.72 However, this US trial had a major bias, because nearly 90% of the control group had at least 1 PSA test. Even the US Preventive Services Task Force changed its recommendations, recommending that clinicians inform men aged 55 to 69 years about the potential benefits and harms of PSA-based screening for prostate cancer.73 In France, several national recommendations propose measuring PSA and performing rectal examination after clear information about benefits and harms to patients age 50 to 75 years. The implication of the present study is that asbestos-exposed male workers older than age 50 years should be encouraged even more to engage in the screening.

Mode of Absorption

Our results showed that respiratory inhalation could increase the risk of prostate cancer, whereas there was no increased risk of oral ingestion of asbestos-contaminated water. The effects of oral ingestion of asbestos on the risk of other cancers are discordant between studies.74 Whereas several studies did not reveal an excess cancer mortality after oral asbestos exposure,75–78 some studies demonstrated an increased risk of some cancers such as gastrointestinal9 or stomach cancer.10 The presence of fibers in organs such as the colon or gastrointestinal tract, kidney, spleen, and liver79–81 is not necessarily linked to the development of a disease.8 However, the inhalation of asbestos undoubtedly has lung and pleural toxicity.82 The key mechanisms of carcinogenesis include oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and genetic and epigenetic alterations as well as cellular toxicity and fibrosis.83 The asbestos fibers can pass the alveolar barrier and reach the lung interstitium, activating several pathways in alveolar and interstitial macrophages and inducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines.84 The fibers accumulate at the site of pleural drainage, passing into the pleural space, which results in chronic damage and inflammation of several cells.85 Then the genotoxic initiation process and/or epigenetic mechanisms mediate the carcinogenic activity of asbestos.83,86 Asbestos fibers are phagocytosed by dividing cells and induce DNA breaks, leading to the presence of fiber-associated iron and reactive oxygen species.87,88 Asbestos has been found in the kidney, brain, and liver but not in the prostate,89 but the translocation pathways for inhaled asbestos fibers are unclear. One hypothesis is that fibers, drained by the pulmonary lymphatic system, could reach the blood and then potentially translocate to all organs.90 A population-based case-control study in 4 Nordic countries concluded that exposure to asbestos might be a risk factor for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.91 For prostate cancer, the mechanism remains unknown.

Type of Exposure

In our study, both environmental and occupational exposures were risk factors for prostate cancer. The World Health Organization estimates that more than 100 million people could be exposed to asbestos in the workplace, resulting in more than 100,000 preventable deaths per year.20 All forms of asbestos are now banned in 63 countries.92 However, a large number of countries still use, import, and export asbestos and asbestos-containing products,21 especially in some new industrial countries.20,21 Attempts to understand the implications of asbestos exposure are ongoing.93,94 Although the risk of occupational asbestos exposure is salient, environmental exposure is also a public health concern.6 In our study, the environmental exposures were by drinking contaminated water or by residential airborne contamination. However, asbestos is also present in geologic formations in several countries, in various forms: Crocidolite in southern Africa, tremolite in Cyprus and Corsica, and erionite in Turkey.95 The International Agency for Research on Cancer classified erionite as a group 1 known human carcinogen and concluded that erionite is the cause of the malignant mesothelioma epidemic in Cappadocia, Turkey.96,97 Other cases of malignant mesothelioma have been reported after environmental exposure, in particular, in the family of asbestos workers.16,98–100 The risk of prostate cancer has never been studied in this population, to our knowledge, and further studies are warranted.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. Meta-analyses inherit the limitations of the individual studies of which they are composed and therefore are subjected to the bias of included studies. Our meta-analyses included studies suffering from confounding bias that precluded our results. Moreover, the meta-analysis is based on a moderate number of studies; however, a previous meta-analysis with fewer studies contributed to effective preventive strategies in asbestos-exposed workers.7 Only 1 study reported an oral ingestion; therefore, stratified results for mode of absorption are inconclusive for oral absorption.35 The difference in screening procedures for prostate cancer between countries101 may have led to bias in the incidence of prostate cancer.

Surprisingly, studies in the European population demonstrated the greater risk without significant results for other continents, whereas it is known that health-related issues caused by asbestos exposure will be a public health problem in new industrial countries.102,103 This finding may be related to a lack of epidemiologic monitoring surveillance.104

One study did not report sex in the total number of participants,37 which can appear problematic in a meta-analysis for prostate cancer. However, this study gave risks of prostate cancer, and calculations in our meta-analysis did not require the number of individuals. Therefore, this study did not alter the quality of the results of the meta-analysis.

Another limitation is the absence of meta-regression based on quantification of asbestos exposure.105 We included several studies2,3,35,39,40,48,62 that estimated exposure on the basis of the address of individuals or job characteristics. Even if such an approach is interesting, heterogeneity of reporting measures between studies precluded further analyses. The last recommendations on measurements of real exposure from the International Labour Organization are more than 30 years old (1986) and do not precisely limit value. Even if the present commonly used limit of 100,000 fibers for 1 cubic meter6 is applied, the recommendations need to be updated in accordance with evidence-based medicine.

Another limitation of our study is scarce information about type of fibers to which individuals were exposed. Indeed, asbestos fibers are divided in 2 groups: Serpentine fibers such as chrysotile and amphibole fibers with crocidolite and amosite, the most used in the past.106 Their toxicity is associated with physicochemical properties of the material, such as length diameter and biopersistence.107–109 We demonstrated that amosite exposure increased the risk of prostate cancer the most; nonetheless, the amosite group also included chrysotile/crocidolite and the percentage of each type of fibers was not reported in the included studies. Thus, incomplete classification precluded robust conclusions on the specific effect of each type of fiber.

Another limitation is the existence of other sources of exposure in addition to asbestos in some included articles.n However, there was no statistical influence of additional exposure on the risk of prostate cancer. Some articles also did not control for addictive behavior such as smoking and alcoholo; nevertheless, associations with prostate cancer incidence are unlikely but still a matter of debate.110–113

Some ecological studies2,35,37,44 in our meta-analysis determined an asbestos environmental exposure based on the patient’s address at the time of the study and did not account for patients who migrated in or out of the area, thus potentially leading to a misclassification of exposure to asbestos. However, sensitivity analyses did not modify our findings (ES = 1.08; 95% CI = 1.05–1.10, I2 = 0.0%). Finally, no studies gave details on the use of personal protective equipment.

CONCLUSION

Asbestos exposure seems to increase the risk of prostate cancer. Considering mode of absorption, the main mechanism was respiratory, without significant results for oral asbestos ingestion. Both environmental and occupational asbestos exposure were linked with increased risk of prostate cancer. Insufficient data did not permit us to analyze the influence of age and the use of protective equipment. The findings of this study imply that people who were exposed to asbestos should possibly be encouraged to complete more frequent prostate cancer screening.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to the University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand, France, which funded the study.

Kathleen Louden, ESL, of Louden Health Communications performed a primary copy edit.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Frédéric Dutheil, MD, PhD, conceived, designed, and performed the experiments; analyzed the data; contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools; helped write the article; and is responsible for integrity of the data analysis. Laetitia Zaragoza-Civale, MD, and Valentin Navel, MD, performed the experiments; analyzed the data; contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools; helped write the article; and are responsible for integrity of the data analysis. Bruno Pereira, PhD, and Julien S Baker, PhD, analyzed the data and contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. Martial Mermillod, PhD; Jeannot Schmidt, MD; and Fares Moustafa, MD, PhD, helped write the article; participated in the literature review; and contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. All authors have given final approval to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kang D-M, Kim J-E, Kim Y-K, Lee H-H, Kim S-Y. Occupational burden of asbestos-related diseases in Korea, 1998–2013: Asbestosis, mesothelioma, lung cancer, laryngeal cancer, and ovarian cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2018 Jul 19;33(35):e226. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid A, Franklin P, Olsen N, et al. All-cause mortality and cancer incidence among adults exposed to blue asbestos during childhood. Am J Ind Med. 2013 Feb;56(2):133–45. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu W-T, Lin Y-J, Shiue H-S, et al. Cancer incidence of Taiwanese shipbreaking workers who have been potentially exposed to asbestos. Environ Res. 2014 Jul;132:370–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rozet F, Hennequin C, Beauval J-B, et al. [CCAFU French national guidelines 2016–2018 on prostate cancer. .[Article in French]]. Prog Urol. 2016 Nov;27(Suppl 1):S95–143. doi: 10.1016/S1166-7087(16)30705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Nov;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuya S, Chimed-Ochir O, Takahashi K, David A, Takala J. Global asbestos disaster. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 May 16;15(5):E1000. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15051000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ollier M, Chamoux A, Naughton G, Pereira B, Dutheil F. Chest CT scan screening for lung cancer in asbestos occupational exposure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2014 Jun;145(6):1339–46. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Condie LW. Review of published studies of orally administered asbestos. Environ Health Perspect. 1983 Nov;53:3–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.83533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mi J, Peng W, Jia X, et al. [A case-control study on the relationship of crocidolite pollution in drinking water with the risk of gastrointestinal cancer in Dayao County. [Article in Chinese]]. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2015 Jan;44(1):28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kjaerheim K, Ulvestad B, Martinsen JI, Andersen A. Cancer of the gastrointestinal tract and exposure to asbestos in drinking water among lighthouse keepers (Norway) Cancer Causes Control. 2005 Jun;16(5):593–8. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-7844-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Band PR, Abanto Z, Bert J, et al. Prostate cancer risk and exposure to pesticides in British Columbia farmers. Prostate. 2011 Feb 1;71(2):168–83. doi: 10.1002/pros.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koutros S, Beane Freeman LE, Lubin JH, et al. Risk of total and aggressive prostate cancer and pesticide use in the Agricultural Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 Jan 1;177(1):59–74. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Multigner L, Ndong JR, Giusti A, et al. Chlordecone exposure and risk of prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Jul 20;28(21):3457–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun FV, Hu QF, Xia GW. [Roles of folate metabolism in prostate cancer. [Article in Chinese]]. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2015 Jul;21(7):659–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pike E, Wien TN, Wisløff T, Harboe I, Klemp M. Cancer risk with folic acid supplements [Internet] Oslo, Norway: Knowledge Centre for the Health Services at The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH). Report form Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services (NOKC) No. 25-2011; 2011. Dec, [cited 2019 Sep 11]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK464903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panou V, Vyberg M, Meristoudis C, et al. Non-occupational exposure to asbestos is the main cause of malignant mesothelioma in women in North Jutland, Denmark. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2019 Jan 1;45(1):82–9. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barbiero F, Zanin T, Pisa FE, et al. Mortality in a cohort of asbestos-exposed workers undergoing health surveillance. Med Lav. 2018 Feb 6;109(2):83–6. doi: 10.23749/mdl.v109i2.5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng Y-S, Holmes TD, Fan B. Evaluation of respirator filters for asbestos fibers. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2006 Jan;3(1):26–35. doi: 10.1080/15459620500444046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank AL, Joshi TK. The global spread of asbestos. Ann Glob Health. 2014 Jul-Aug;80(4):257–62. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stayner L, Welch LS, Lemen R. The worldwide pandemic of asbestos-related diseases. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34(1):205–16. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaDou J, Castleman B, Frank A, et al. The case for a global ban on asbestos. Environ Health Perspect. 2010 Jul;118(7):897–901. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.da Costa BR, Cevallos M, Altman DG, Rutjes AWS, Egger M. Uses and misuses of the STROBE statement: Bibliographic study. BMJ Open. 2011 Feb 26;1(1):e000048–000048. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014 Dec;12(12):1495–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [Internet] Ottawa, Canada: The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2014. [cited 2019 Dec 5]. Available from: www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navel V, Mulliez A, Benoist d’Azy C, et al. Efficacy of treatments for Demodex blepharitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ocul Surf. 2019 Oct;17(4):655–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage F-X, Dutheil F. Creatine supplementation and lower limb strength performance: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Sports Med. 2015 Sep;45(9):1285–94. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage F-X, Dutheil F. Creatine supplementation and upper limb strength performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017 Jan;47(1):163–73. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benichou T, Pereira B, Mermillod M, et al. Heart rate variability in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. In: Malik RA, editor. PLoS One. 4. Vol. 13. 2018. Apr 2, p. e0195166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benoist d’Azy C, Pereira B, Chiambaretta F, Dutheil F. Oxidative and anti-oxidative stress markers in chronic glaucoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016 Dec 1;11(12):e0166915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benoist d’Azy C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Chiambaretta F, Dutheil F. Antibioprophylaxis in prevention of endophthalmitis in intravitreal injection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 3;11(6):e0156431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Courtin R, Pereira B, Naughton G, et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease in visual display terminal workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016 Jan 14;6(1):e009675. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986 Sep;7(3):177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2000 Nov 30;19(22):3127–31. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3127::AID-SIM784>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russo MW. How to review a meta-analysis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2007 Aug;3(8):637–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howe HL, Wolfgang PE, Burnett WS, Nasca PC, Youngblood L. Cancer incidence following exposure to drinking water with asbestos leachate. Public Health Rep. 1989 May-Jun;104(3):251–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ilić M, Vlajinac H, Marinković J. Case-control study of risk factors for prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996 Nov;74(10):1682–6. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korda RJ, Clements MS, Armstrong BK, et al. Risk of cancer associated with residential exposure to asbestos insulation: A whole-population cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2017 Nov;2(11):e522–8. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koskinen K, Pukkala E, Reijula K, Karjalainen A. Incidence of cancer among the participants of the Finnish Asbestos Screening Campaign. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003 Feb;29(1):64–70. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pira E, Pelucchi C, Piolatto PG, Negri E, Bilei T, La Vecchia C. Mortality from cancer and other causes in the Balangero cohort of chrysotile asbestos miners. Occup Environ Med. 2009 Dec;66(12):805–9. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.044693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armstrong BK, de Klerk NH, Musk AW, Hobbs MS. Mortality in miners and millers of crocidolite in Western Australia. Br J Ind Med. 1988 Jan;45(1):5–13. doi: 10.1136/oem.45.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berry G, Newhouse ML, Wagner JC. Mortality from all cancers of asbestos factory workers in east London 1933–80. Occup Environ Med. 2000 Nov;57(11):782–5. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.11.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clemmesen J, Hjalgrim-Jensen S. Cancer incidence among 5686 asbestos-cement workers followed from 1943 through 1976. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 1981 Mar;5(1):15–23. doi: 10.1016/0147-6513(81)90042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Enterline PE, Hartley J, Henderson V. Asbestos and cancer: A cohort followed up to death. Br J Ind Med. 1987 Jun;44(6):396–401. doi: 10.1136/oem.44.6.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Franklin P, Reid A, Samuel L, Olsen N. Cancer incidence in individuals exposed to asbestos in childhood. Respirology. 2012;17:12–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02142.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughes JM, Weill H, Hammad YY. Mortality of workers employed in two asbestos cement manufacturing plants. Br J Ind Med. 1987 Mar;44(3):161–74. doi: 10.1136/oem.44.3.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kovalevskiy EV, Schonfeld SJ, Feletto E, et al. Comparison of mortality in Asbest city and the Sverdlovsk region in the Russian Federation: 1997–2010. Environ Health. 2016 Mar 1;15(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12940-016-0125-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krstev S, Stewart P, Rusiecki J, Blair A. Mortality among shipyard Coast Guard workers: A retrospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2007 Oct;64(10):651–8. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.029652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meurman LO, Pukkala E, Hakama M. Incidence of cancer among anthophyllite asbestos miners in Finland. Occup Environ Med. 1994 Jun;51(6):421–5. doi: 10.1136/oem.51.6.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parent M-E, Hugues Richard M. O8A.4 Asbestos exposure and prostate cancer, really? Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(Suppl 1):A71. doi: 10.1136/OEM-2019-EPI.190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pesch B, Taeger D, Johnen G, et al. Cancer mortality in a surveillance cohort of German males formerly exposed to asbestos. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2010 Jan;213(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pira E, Pelucchi C, Piolatto PG, Negri E, Discalzi G, La Vecchia C. First and subsequent asbestos exposures in relation to mesothelioma and lung cancer mortality. Br J Cancer. 2007 Nov 5;97(9):1300–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Puntoni R, Merlo F, Borsa L, Reggiardo G, Garrone E, Ceppi M. A historical cohort mortality study among shipyard workers in Genoa, Italy. Am J Ind Med. 2001 Oct;40(4):363–70. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Puntoni R, Vercelli M, Merlo F, Valerio F, Santi L. Mortality among shipyard workers in Genoa, Italy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1979;330(1 Health Hazard):353–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1979.tb18738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raffn E, Lynge E, Juel K, Korsgaard B. Incidence of cancer and mortality among employees in the asbestos cement industry in Denmark. Br J Ind Med. 1989 Feb;46(2):90–6. doi: 10.1136/oem.46.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Selikoff IJ, Hammond EC, Seidman H. Mortality experience of insulation workers in the United States and Canada, 1943–1976. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1979;330:91–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1979.tb18711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sorahan TM. Cancer incidence in UK electricity generation and transmission workers, 1973–2015. Occup Med (Lond) 2019 Aug 22;69(5):342–51. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqz082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Urszula W, Szymczak W, Strzelecka A. Mortality study of workers compensated for asbestosis in Poland, 1970–1997. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2002;15(3):267–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tola S, Kalliomäki PL, Pukkala E, Asp S, Korkala ML. Incidence of cancer among welders, platers, machinists, and pipe fitters in shipyards and machine shops. Br J Ind Med. 1988 Apr;45(4):209–18. doi: 10.1136/oem.45.4.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomioka K, Natori Y, Kumagai S, Kurumatani N. An updated historical cohort mortality study of workers exposed to asbestos in a refitting shipyard, 1947–2007. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011 Dec;84(8):959–67. doi: 10.1007/s00420-011-0655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsai SP, Waddell LC, Gilstrap EL, Ransdell JD, Ross CE. Mortality among maintenance employees potentially exposed to asbestos in a refinery and petrochemical plant. Am J Ind Med. 1996 Jan;29(1):89–98. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199601)29:1<89::AID-AJIM11>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van den Borre L, Deboosere P. Enduring health effects of asbestos use in Belgian industries: A record-linked cohort study of cause-specific mortality (2001–2009) BMJ Open. 2015 Jun 24;5(6):e007384. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang X, Lin S, Yu I, Qiu H, Lan Y, Yano E. Cause-specific mortality in a Chinese chrysotile textile worker cohort. Cancer Sci. 2013 Feb;104(2):245–9. doi: 10.1111/cas.12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilczyńska U, Szymczak W, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N. Mortality from malignant neoplasms among workers of an asbestos processing plant in Poland: Results of prolonged observation. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2005;18(4):313–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhivin S, Laurier D, Caër-Lorho S, Acker A, Guseva Canu I. Impact of chemical exposure on cancer mortality in a French cohort of uranium processing workers. Am J Ind Med. 2013 Nov;56(11):1262–71. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pukkala E, Martinsen JI, Weiderpass E, et al. Cancer incidence among firefighters: 45 years of follow-up in five Nordic countries. Occup Environ Med. 2014 Jun;71(6):398–404. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2013-101803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratliff TL, et al. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991 Apr 25;324(17):1156–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104253241702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Draisma G, Boer R, Otto SJ, et al. Lead times and overdetection due to prostate-specific antigen screening: Estimates from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003 Jun 18;95(12):868–78. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.12.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Meng MV, Mehta SS, Carroll PR. The changing face of low-risk prostate cancer: Trends in clinical presentation and primary management. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Jun 1;22(11):2141–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Heijnsdijk EA, Wever EM, Auvinen A, et al. Quality-of-life effects of prostate-specific antigen screening. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 16;367(7):595–605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arnsrud Godtman R, Holmberg E, Lilja H, Stranne J, Hugosson J. Opportunistic testing versus organized prostate-specific antigen screening: Outcome after 18 years in the Göteborg randomized population-based prostate cancer screening trial. Eur Urol. 2015 Sep;68(3):354–60. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. ERSPC Investigators. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: Results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014 Dec 6;384(9959):2027–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, 3rd, et al. PLCO Project Team. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: Mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012 Jan 18;104(2):125–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ. The US Preventive Services Task Force 2017 draft recommendation statement on screening for prostate cancer: An invitation to review and comment. JAMA. 2017 May 16;317(19):1949–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wigle DT. Cancer mortality in relation to asbestos in municipal water supplies. Arch Environ Health. 1977 Jul-Aug;32(4):185–90. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1977.10667278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Harrington JM, Craun GF, Meigs JW, Landrigan PJ, Flannery JT, Woodhull RS. An investigation of the use of asbestos cement pipe for public water supply and the incidence of gastrointestinal cancer in Connecticut, 1935–1973. Am J Epidemiol. 1978 Feb;107(2):96–103. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Millette JR, Craun GF, Stober JA, et al. Epidemiology study of the use of asbestos-cement pipe for the distribution of drinking water in Escambia County, Florida. Environ Health Perspect. 1983 Nov;53:91–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.835391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McCullagh SF. Is there a risk to health in using asbestos—Cement pipes for the carriage of drinking water? Ann Occup Hyg. 1980;23(2):189–93. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/23.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fiorenzuolo G, Moroni V, Cerrone T, Bartolucci E, Rossetti S, Tarsi R. [Evaluation of the quality of drinking water in Senigallia (Italy), including the presence of asbestos fibres, and of morbidity and mortality due to gastrointestinal tumours. [Article in Italian]]. Ig Sanita Pubbl. 2013 May-Jun;69(3):325–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Levine DS. Does asbestos exposure cause gastrointestinal cancer? Dig Dis Sci. 1985 Dec;30(12):1189–98. doi: 10.1007/BF01314055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Patel-Mandlik K, Millette J. Accumulation of ingested asbestos fibers in rat tissues over time. Environ Health Perspect. 1983 Nov;53:197–200. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8353197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Donham KJ, Berg JW, Will LA, Leininger JR. The effects of long-term ingestion of asbestos on the colon of F344 rats. Cancer. 1980 Mar 15;45(5 Suppl):1073–84. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800315)45:5+<1073::AID-CNCR2820451308>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pascolo L, Gianoncelli A, Schneider G, et al. The interaction of asbestos and iron in lung tissue revealed by synchrotron-based scanning X-ray microscopy. Sci Rep. 2013;3(1):1123. doi: 10.1038/srep01123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huang SXL, Jaurand M-C, Kamp DW, Whysner J, Hei TK. Role of mutagenicity in asbestos fiber-induced carcinogenicity and other diseases. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2011;14(1–4):179–245. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2011.556051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dostert C, Pétrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J. Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science. 2008 May 2;320(5876):674–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Comertpay S, Pastorino S, Tanji M, et al. Evaluation of clonal origin of malignant mesothelioma. J Transl Med. 2014 Dec 4;12(1):301. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0301-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Møller P, Danielsen PH, Jantzen K, Roursgaard M, Loft S. Oxidatively damaged DNA in animals exposed to particles. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2013 Feb;43(2):96–118. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2012.756456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kane AB. Mechanisms of mineral fibre carcinogenesis. IARC Sci Publ. 1996;(140):11–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shukla A, Gulumian M, Hei TK, Kamp D, Rahman Q, Mossman BT. Multiple roles of oxidants in the pathogenesis of asbestos-induced diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003 May 1;34(9):1117–29. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(03)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Auerbach O, Conston AS, Garfinkel L, Parks VR, Kaslow HD, Hammond EC. Presence of asbestos bodies in organs other than the lung. Chest. 1980 Feb;77(2):133–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.77.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Miserocchi G, Sancini G, Mantegazza F, Chiappino G. Translocation pathways for inhaled asbestos fibers. Environ Health. 2008 Jan 24;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Farioli A, Straif K, Brandi G, et al. Occupational exposure to asbestos and risk of cholangiocarcinoma: A population-based case-control study in four Nordic countries. Occup Environ Med. 2018 Mar;75(3):191–8. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2017-104603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Felley-Bosco E, MacFarlane M. Asbestos: Modern Insights for Toxicology in the Era of Engineered Nanomaterials. Chem Res Toxicol. 2018 Oct 15;31(10):994–1008. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.8b00146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.An YS, Kim HD, Kim HC, Jeong KS, Ahn YS. The characteristics of asbestos-related disease claims made to the Korea Workers’ Compensation and Welfare Service (KCOMWEL) from 2011 to 2015. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2018 Jul 11;30(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s40557-018-0256-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lin R-T, Chang Y-Y, Wang J-D, Lee LJ-H. Upcoming epidemic of asbestos-related malignant pleural mesothelioma in Taiwan: A prediction of incidence in the next 30 years. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019 Jan;118(1 Pt 3):463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Koike S. [Health effects of non-occupational exposure to asbestos. [Article in Japanese]]. Sangyo Igaku. 1992 May;34(3):205–15. doi: 10.1539/joh1959.34.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Carbone M, Baris YI, Bertino P, et al. Erionite exposure in North Dakota and Turkish villages with mesothelioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011 Aug 16;108(33):13618–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105887108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Baris YI, Grandjean P. Prospective study of mesothelioma mortality in Turkish villages with exposure to fibrous zeolite. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006 Mar 15;98(6):414–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mensi C, Riboldi L, De Matteis S, Bertazzi PA, Consonni D. Impact of an asbestos cement factory on mesothelioma incidence: Global assessment of effects of occupational, familial, and environmental exposure. Environ Int. 2015 Jan;74:191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Metintas S, Ak G, Metintas M. A review of the cohorts with environmental and occupational mineral fiber exposure. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2019;74(1–2):76–84. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2018.1467873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.D’Agostin F, de Michieli P, Negro C. Pleural mesothelioma in household members of asbestos-exposed workers in Friuli Venezia Giulia, Italy. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2017 May 8;30(3):419–31. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Drazer MW, Huo D, Eggener SE. National prostate cancer screening rates after the 2012 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation discouraging prostate-specific antigen-based screening. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Aug 1;33(22):2416–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Choi Y, Lim S, Paek D. Trades of dangers: A study of asbestos industry transfer cases in Asia. Am J Ind Med. 2013 Mar;56(3):335–46. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Subramanian V, Madhavan N. Asbestos problem in India. Lung Cancer. 2005 Jul;49(Suppl 1):S9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Le GV, Takahashi K, Park E-K, et al. Asbestos use and asbestos-related diseases in Asia: Past, present and future. Respirology. 2011 Jul;16(5):767–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.01975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gramond C, Rolland P, Lacourt A, et al. PNSM Study Group. Choice of rating method for assessing occupational asbestos exposure: Study for compensation purposes in France. Am J Ind Med. 2012 May;55(5):440–9. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bernstein D, Dunnigan J, Hesterberg T, et al. Health risk of chrysotile revisited. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2013 Feb;43(2):154–83. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2012.756454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Donaldson K, Murphy FA, Duffin R, Poland CA. Asbestos, carbon nanotubes and the pleural mesothelium: A review of the hypothesis regarding the role of long fibre retention in the parietal pleura, inflammation and mesothelioma. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2010 Mar 22;7(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fenoglio I, Aldieri E, Gazzano E, et al. Thickness of multiwalled carbon nanotubes affects their lung toxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012 Jan 13;25(1):74–82. doi: 10.1021/tx200255h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fenoglio I, Fubini B, Ghibaudi EM, Turci F. Multiple aspects of the interaction of biomacromolecules with inorganic surfaces. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011 Oct;63(13):1186–209. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Huncharek M, Haddock KS, Reid R, Kupelnick B. Smoking as a risk factor for prostate cancer: A meta-analysis of 24 prospective cohort studies. Am J Public Health. 2010 Apr;100(4):693–701. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.150508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rohrmann S, Linseisen J, Allen N, et al. Smoking and the risk of prostate cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Br J Cancer. 2013 Feb 19;108(3):708–14. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ordóñez-Mena JM, Schöttker B, Mons U, et al. Consortium on Health and Ageing: Network of Cohorts in Europe and the United States (CHANCES) Quantification of the smoking-associated cancer risk with rate advancement periods: Meta-analysis of individual participant data from cohorts of the CHANCES consortium. BMC Med. 2016 Apr 5;14(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0607-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: A comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2015 Feb 3;112(3):580–93. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]