Abstract

An effective epidermal barrier requires structural and functional integration of adherens junctions, tight junctions, gap junctions (GJ), and desmosomes. Desmosomes govern epidermal integrity while GJs facilitate small molecule transfer across cell membranes. Some patients with Severe dermatitis, multiple Allergies, and Metabolic wasting (SAM) syndrome, caused by biallelic Desmoglein 1 (DSG1) mutations, exhibit skin lesions reminiscent of Erythrokeratodermia Variabilis, caused by mutations in Connexin genes (Cxs). We therefore examined whether SAM syndrome-causing DSG1 mutations interfere with Cx expression and GJ function. Lesional skin biopsies from SAM syndrome patients (n=7) revealed decreased Dsg1 and Cx43 plasma membrane localization compared with control and non-lesional skin. Cultured keratinocytes and organotypic skin equivalents depleted of Dsg1 exhibited reduced Cx43 expression, rescued upon re-introduction of wild-type Dsg1, but not Dsg1 constructs modeling SAM syndrome-causing mutations. Ectopic Dsg1 expression increased cell-cell dye transfer, which Cx43 silencing inhibited, suggesting Dsg1 promotes GJ function through Cx43. As GJA1 gene expression was not decreased upon Dsg1 loss, we hypothesized that Cx43 reduction was due to enhanced protein degradation. Supporting this, PKC-dependent Cx43 S368 phosphorylation, which signals Cx43 turnover, increased after Dsg1 depletion, while lysosomal inhibition restored Cx43 levels. These data reveal a role for Dsg1 in regulating epidermal Cx43 turnover.

INTRODUCTION

Intercellular junctions including adherens junctions, tight junctions, gap junctions (GJ), and desmosomes are required for proper epidermal barrier formation and function (Mese et al., 2007). GJs are formed by proteins from the connexin (Cx) family encoded by genes subdivided into five subfamilies (GJA-GJE) (Martin et al., 2014, Beyer et al, 2017). Cx proteins form homomeric or heteromeric hexamers (termed connexons) on two adjacent cells to produce docked hemichannels for direct cell-cell molecular exchange (Boyden et al., 2016, Laird, 2008). Cx43, one of the Cxs expressed in the epidermis, has a short half-life of one to three hours. Its dynamics are regulated by phosphorylation of several C-terminal amino acids, which affects connexin internalization, degradation, and assembly into gap junctions (Solan and Lampe, 2018).

GJs play diverse roles in normal physiology, and skin diseases have been attributed to mutations in genes encoding five of the Cxs-Cx26, Cx30, Cx30.3, Cx31 and Cx43 (Lai-Cheong et al., 2007, Scott et al., 2012, Boyden et al., 2015, Shuja et al., 2016). Erythrokeratodermia Variabilis (EKV) is a group of diseases mainly caused by mutations in Cx-encoding genes. Most frequently mutated are GJB3 and GJB4, encoding Cxs30.3 and 31, respectively (Richard et al., 1998, Macari et al., 2000). While less frequent, mutations in GJA1, encoding Cx43, also cause EKV (Boyden et al., 2015), and EKV-causing mutations in the Cx31-encoding gene can exert trans-dominant functional inhibition on Cx43 (Schnichels et al., 2007, Scott et al., 2012).

Severe dermatitis, multiple Allergies, and Metabolic wasting (SAM) syndrome is caused by bi-allelic mutations in DSG1, encoding the desmosomal cadherin Desmoglein 1 (Dsg1) (Samuelov et al., 2013). Curiously, some SAM syndrome patients present with chronic circumscribed, well demarcated, hyperkeratotic, erythematous to brownish plaques mimicking EKV (Has et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2016; Schlipf et al., 2016; Taiber et al., 2018). Desmosomal components such as Desmoglein 2 (Dsg2), Desmoplakin (DP), Plakoglobin (PG), and Plakophilin 2 (Pkp2) can regulate Cx expression, trafficking, localization, and ubiquitination, especially in cardiac tissue (Oxford et al., 2007, Asimaki et al., 2009, Asimaki et al. 2014, Ghemlich et al, 2010, Patel et al., 2014, Kam et al., 2018). Therefore, we hypothesized that Dsg1 plays a role in GJ dynamics in skin. Here, clinical and histological analysis of biopsies from patients representing families with three different SAM syndrome mutations, along with in vitro analysis of keratinocytes deficient for Dsg1 or expressing Dsg1 constructs representing SAM syndrome mutations, revealed a role for Dsg1 in regulating Cx43 stability and function.

RESULTS

EKV-like clinical features in SAM syndrome

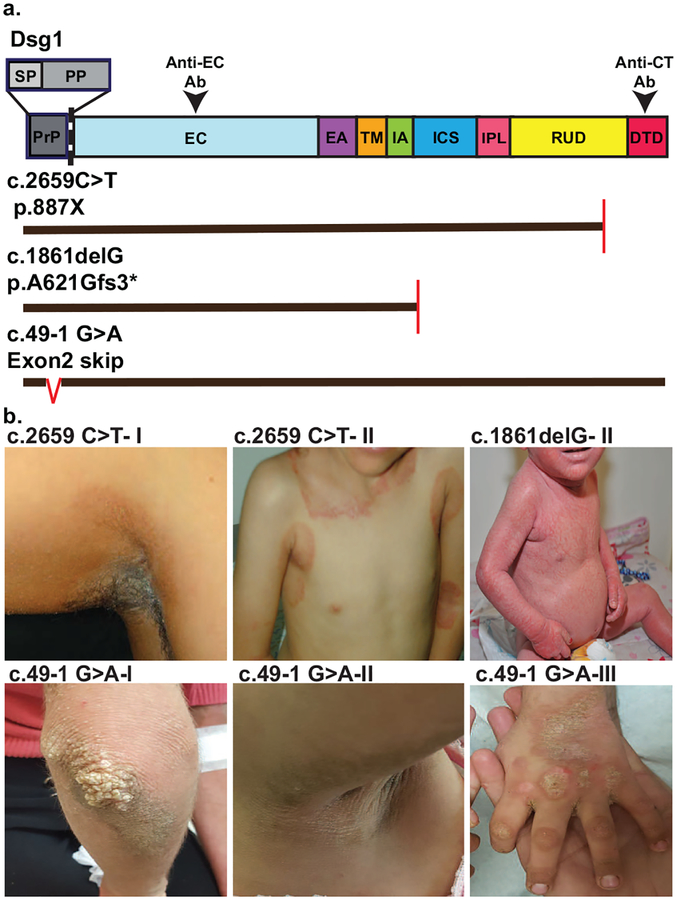

Seven patients from three families were investigated, six females and one male. Ages ranged from 4–32 years. Clinical follow-up ranged from 4–28 years. Figure 1a presents a schematic of the DSG1 mutations associated with these patients.

Figure 1. Some patients with SAM syndrome manifest clinical features of EKV.

a. Schematic of Dsg1 protein domains, mutation positions, predicted impact of mutations on protein structure, and regions of Dsg1 protein recognized by antibodies used in this study for immunofluorescence detection (Anti-EC Ab, Anti-CT Ab). Vertical red lines in mutants denote premature termination, red carrot in C.49–1 G>A denotes skipping. Domains: SP: signal peptide, PP: pro-protein, PrP: SP+ Pro protein, EC: extracellular, EA: EC anchor, TM: transmembrane, IA: intracellular anchor, ICS: intracellular cadherin-like sequence, IPL: intracellular proline-rich linker, RUD: repeat unit domain, DTD: Desmoglein specific terminal domain. b. Seven patients from three families were investigated and family members are denoted with roman numerals (I-III). Patients c.2659 C>T-I, II present with well demarcated brown/erythematous plaques with involvement in skin folds, reminiscent of EKV. Patient c.1861delG-II shows erythroderma with fine scales. Patients c.49–1 G>A I-III present with areas of well-defined hyperkeratotic brown plaques, reminiscent of EKV.

The homozygous c.2659 C>T mutation introduces a premature termination codon (p.887X) (Has et al., 2014; Taiber et al., 2018). The homozygous 1861delG mutation is expected to cause a frameshift resulting in a premature stop codon (p.A621Gfs3*) (Samuelov et al, 2013). The homozygous c.49–1 G>A mutation was previously shown to cause an in-frame skipping of DSG1 exon 2. The resulting 12-amino-acid deletion in the Dsg1 signal peptide leads to Dsg1 mislocalization and accumulation in the ER (Samuelov et al., 2013; Figure 1a).

All patients included in the study presented with severe palmoplantar keratoderma and food allergies. In five of the patients, the predominant cutaneous clinical feature was hyperkeratotic / scaly, erythematous to brown plaques, reminiscent of EKV (Dsg1 mutations c.2659 C>T and c.49–1 G>A). Two patients suffered from longstanding, non-remitting erythroderma (Dsg1 mutation c.1861delG). Representative clinical images are shown in Figure 1b and Figure S1.

Dsg1 expression varies within the same individual between lesional and non-lesional skin

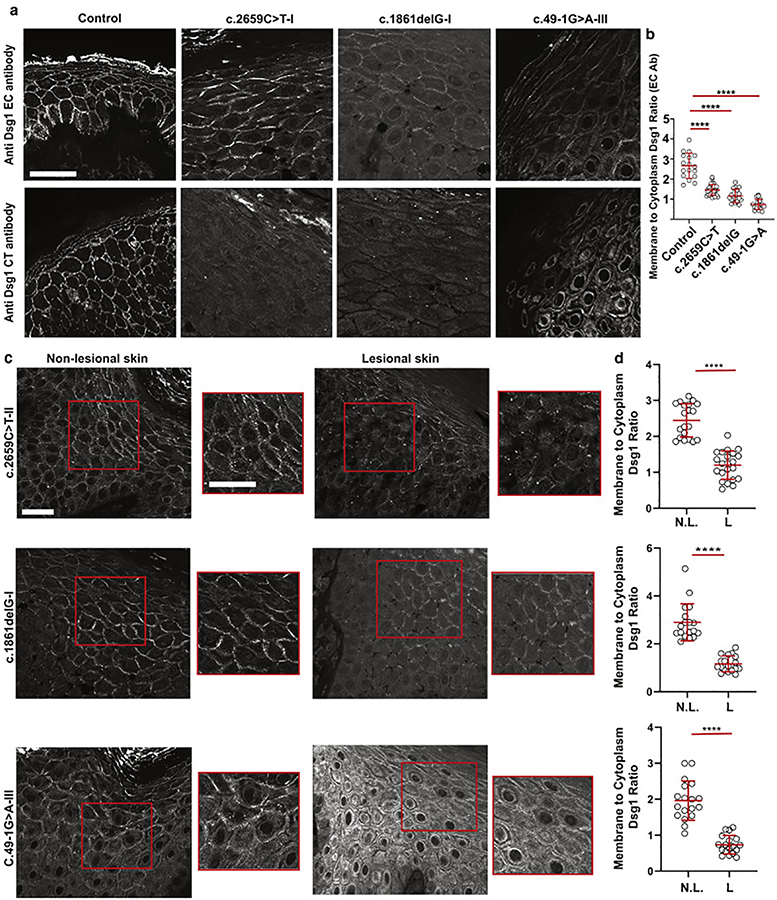

To determine how DSG1 mutations impact Dsg1 protein expression and localization in patient skin, we conducted immunofluorescence (IF) staining of skin biopsies from each of the patients using two different antibodies recognizing Dsg1. One antibody recognizes the Dsg1 extracellular domain (EC). The second antibody recognizes the C-terminal (CT) domain (amino acids 1000–1049).

Compared to the plasma membrane localization of Dsg1 in control skin, plasma membrane Dsg1 was partially lost in all of the patient biopsies using the EC antibody (Figure 2a, b and Figure S2). Increased cytoplasmic signal with patchy plasma membrane staining was observed in patients harboring the c.1861delG and c.49–1 G>A mutations with the EC antibodies, particularly in the lower spinous layers. However, Dsg1 staining was not observed in biopsies from patients carrying either the c.2659C>T or c.1861delG mutation when stained with the CT antibody, consistent with the predicted premature termination of protein translation. The mixed junctional and cytoplasmic staining pattern for the c.49–1 G>A mutation was similar when using either the EC or CT antibody.

Figure 2. Dsg1 expression varies within the same individual between lesional and nonlesional skin.

a. Immunofluorescence staining of biopsies from lesional skin obtained from a patient from each family in the study compared to control skin, using an anti-Dsg1 ectodomain (EC) antibody and an anti-Dsg1 C-terminal (CT) antibody (scale bar = 20 μm). b. Ratio of plasma membrane to cytoplasmic Dsg1staining using the EC antibody (E-cadherin was used as a membrane marker. n = 20 borders per sample. Error bars represent mean difference ± SD. ****p<0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnet’s post hoc test). c. Immunofluorescence staining of lesional and non-lesional skin sections with the EC Dsg1 antibody (scale bar = 20 μm). Red boxed regions of the suprabasal layers of the patient epidermis are shown magnified to the right of the lower magnification images (scale bar = 20 μm). d. Plasma membrane to cytoplasmic Dsg1 ratio (E-cadherin was used as a membrane marker. n = 20 borders per sample. Error bars represent mean difference ± SD. ****p<0.0001 by two-tailed Student’s t test. L = lesional, N.L. = non-lesional).

The c.2659C>T and 1861delG mutations were both previously reported to result in negligible amounts of both protein and RNA, the latter reportedly due to mRNA decay (Samuelov et al., 2013, Has et al., 2014). Since we observed Dsg1 protein in the skin biopsies from these patients, we hypothesized that mutant Dsg1 expression and localization might vary between diseased and healthy skin. Using the EC antibody, we compared Dsg1 expression in biopsies from lesional and non-lesional trunk skin from the same patient (Figure 2c). Significantly reduced membrane to cytoplasmic Dsg1 ratios were observed in all lesional areas compared with the non-lesional skin from the same patient, independent of the mutation type (Figure 2d). Patients with c.1861delG and c.49–1G>A mutations also showed prominent cytoplasmic Dsg1 staining.

Considering that most patients with SAM syndrome do not manifest blistering disease, we hypothesized that the expression of other junctional proteins is sufficient to prevent loss of adhesion. To test this, we first stained lesional skin samples for Desmoplakin (DP), β-catenin and Desmocollin 1 (Dsc1) (Figure S3), which showed that membrane to cytoplasm ratios of DP and β-catenin were not reduced compared to control, while the Dsc1 ratio was even increased in the c.1861delG and c.49–1G>A biopsies. Furthermore, the expression and localization of the junctional proteins DP, PG, E-cadherin and β-catenin were not altered in submerged normal human epidermal keratinocyte cultures (NHEKs) or epidermal raft cultures upon Dsg1 depletion compared to controls (Figure S4a, b, c, d). Finally, the dispase based dissociation assay was used to test the adhesive properties of Dsg1-silenced NHEKs compared to control and DP-silenced NHEKs (Figure S4e, f, g). Control and Dsg1-silenced cell sheets remained intact compared to DP-silenced cell sheets, which showed significant fragmentation (Figure S4f). These results suggest that loss of Dsg1 is insufficient to weaken keratinocyte adhesion when other desmosomal proteins are still expressed and functioning to maintain adhesion at the plasma membrane.

Plasma membrane-localized Cx43 is reduced in patients with SAM syndrome and correlates with Dsg1 expression

Several of the SAM syndrome patients analyzed in this report presented with clinical features similar to EKV. In this work, we focused on Cx43, as it is one of the GJ proteins linked to EKV (Boydon et al. 2015) and its expression and localization are influenced by desmosomes in skin and heart. (Oxford et al., 2007, Noorman et al., 2013, Asimaki et al., 2014, Patel et al., 2014, Kam et al., 2018). We hypothesized that loss of Dsg1 may lead to abnormal GJ protein expression and impaired function.

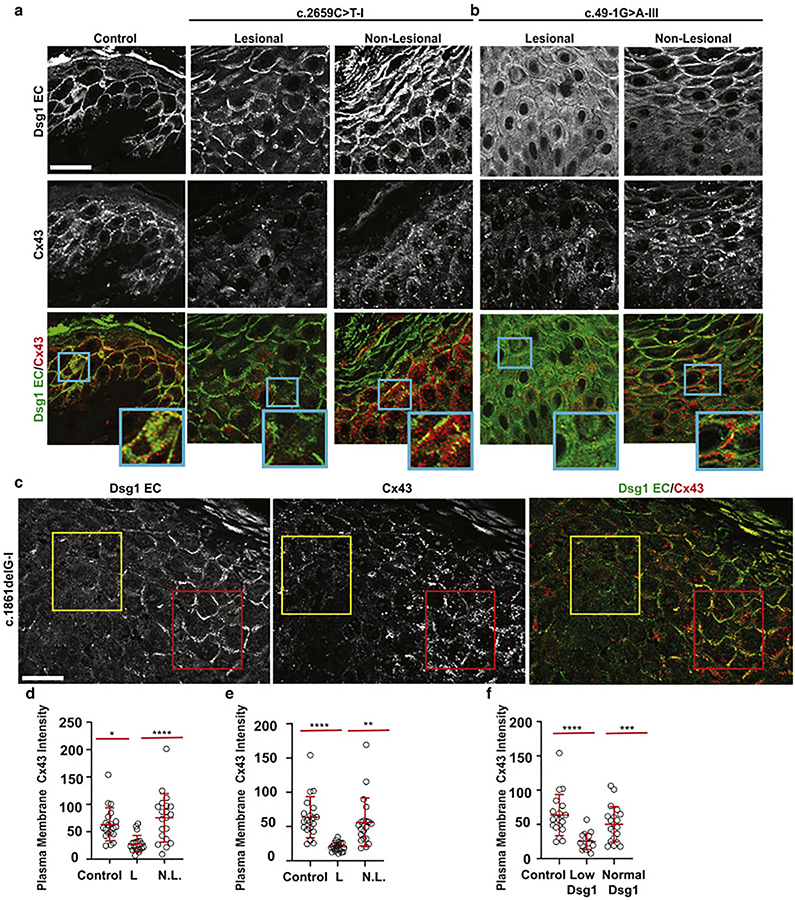

To test this idea, we first carried out immunofluorescence staining for Dsg1 and Cx43 in lesional and non-lesional patient skin (Figure 3a, b, c). Then, using E-cadherin as a plasma membrane marker, we quantified plasma membrane-associated Cx43 (see methods for detailed explanation). This analysis showed that mean plasma membrane-localized Cx43 intensity was higher in control and non-lesional epidermis than in lesional skin from patients with the c.2659C>T mutation and c.49–1G>A mutation (Figure 3d, e). Particularly compelling is a side-by-side comparison of adjacent regions within a biopsy taken at the boundary between lesional and non-lesional skin in a patient with the c.1861delG mutation. In this example, relatively normal Dsg1 expression is observed next to areas lacking Dsg1 staining (Figure 3c). Analysis revealed higher Cx43 levels in Dsg1 positive cells compared to Dsg1 negative cells (Figure 3f).

Figure 3. Plasma membrane-localized Cx43 intensity is reduced in patients with SAM syndrome, correlating with Dsg1 expression.

a, b. Immunofluorescence staining of Dsg1 (ectodomain [EC] antibody) and Cx43 in lesional and non-lesional skin sections from patients with c.2659C>T and c.49–1G>A Dsg1 mutations (scale bar = 20 μm). Insets are magnified regions of plasma membranes demonstrating the level of Dsg1 and Cx43 localization in lesional and non-lesional areas of the biopsies. c. Immunofluorescence staining at the edge of lesional skin (c.1861delG-I) showing areas of low and normal Dsg1 expression and corresponding Cx43 levels (scale bar = 20 μm). d, e, f. Quantification of plasma membrane-associated Cx43 staining intensity from panels a, b, c. (n = 30 borders per sample. Error bars represent mean difference ± SD. *p=0.023; **p=0.0045; ***p=0.0003; ****p<0.0001 by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. L = lesional, N.L. = non-lesional).

Dsg1 loss reduces Cx43 expression, which is restored by ectopically expressed wild type Dsg1, but not SAM syndrome mutants

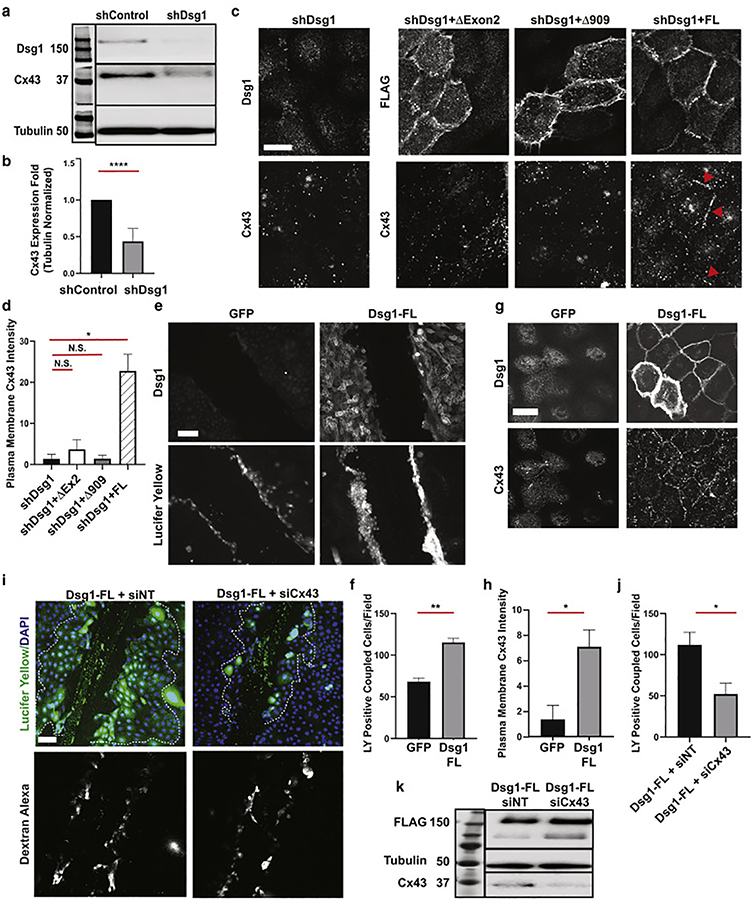

To test the hypothesis that Dsg1 loss affects Cx43 expression, we compared Dsg1 and Cx43 expression in NHEK controls and cells in which Dsg1 was depleted by shRNA. Cx43 expression was significantly reduced when Dsg1 was depleted compared with control cells (Figure 4a, b).

Figure 4. Dsg1 loss reduces Cx43 expression while Dsg1 expression promotes GJ function through Cx43.

a. Immunoblot of Dsg1 and Cx43 in NHEKs infected with shControl or shDsg1 72h after calcium switch (Tubulin = loading control, n = 6). b. Quantification of fold changes in Cx43 protein expression presented in a. Error bars = mean ± SD. ****p<0.0001, two-tailed Student’s t test. c. Immunofluorescence of Dsg1, FLAG, and Cx43 in NHEKs infected with shDsg1, or shDsg1 in combination with Dsg1-ΔExon2-FLAG, Dsg1-Δ909-FLAG, or Dsg1-FL-FLAG 72 h after switching cells to high calcium containing medium. Red arrowheads highlight examples of Cx43 localization at cell borders, coincident with Dsg1-FL construct expression (scale bar = 10 μm). Refer to Supplemental Figure 5d for Dsg1 and Cx43 staining of shControl infected suprabasal cells. d. Quantification of plasma membrane localized Cx43 from c (PG intensities were comparable among samples and was used as a membrane marker. Average of 3 independent experiments with at least 20 borders/condition/experiment; Error bars = mean ± SD. *p=0.012, by one-way ANOVA with Dunnet’s post hoc test, N.S. = not significant). e. Representative images of Dsg1 immunofluorescence and Lucifer yellow (LY) dye in GJIC transfer assays from GFP or Dsg1-FL retrovirally-infected NHEKs 16h after switching cells to high calcium containing medium. (Scale bar = 100 μm). f. Quantification of LY dye transfer (Average of 3 independent experiments with at least 15 fields/condition/experiment; Error bars = mean ± SD. Error bars represent mean ± SD. **p=0.009 by two-tailed Student’s t test). g. Immunofluorescence of Dsg1 and Cx43 in GFP and Dsg1-FL-FLAG infected NHEKs (scale bar = 20 μm). h. Quantification of plasma membrane localized Cx43 from g (PG intensities were comparable among samples and was used as a membrane marker. Average of 3 independent experiments with at least 15 fields/condition/experiment; Error bars = mean ± SD. Error bars represent mean ± SD. *p=0.038 by two-tailed Student’s t test). i. Representative images of GJIC dye transfer assays from Dsg1-FL-FLAG-infected NHEKs, transfected with siCx43 vs siNT, 16h after switch to high calcium-containing medium. Dextran-Alexa-Fluor 647 was used to identify cells at the edge of the wound that are loaded due to membrane damage and not indicative of GJ function. Dashed white lines indicate regions included in the quantification in j (scale bar = 100μm). j. Quantification of LY dye transfer from i (Average of 3 independent experiments with at least 15 fields/condition/experiment; Error bars = mean ± SD. Error bars represent mean ± SD. *p=0.019 by two-tailed Student’s t test). k. Immunoblot of Dsg1, Tubulin and Cx43 from i demonstrating Cx43 knockdown and Dsg1-FL expression.

To demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship between Dsg1 and Cx43, we infected control or Dsg1-silenced NHEKs with retroviruses expressing full-length-Dsg1-FLAG (FL), or constructs simulating the SAM syndrome-causing mutations. The -Dsg1-ΔExon2-FLAG (ΔEx2) construct simulates the c.49–1 G>A mutation, while the Dsg1-Δ909-FLAG (Δ909) has a premature termination codon in close proximity to that created by the c.2659 C>T mutation (p.887X). A schematic of these constructs, their expression in NHEKs, and quantification of membrane-to-cytoplasmic fluorescence intensities are provided in Figure S5. FL-Dsg1 expression restored Cx43 staining intensity in Dsg1 knockdown NHEKs, but neither ΔEx2 nor Δ909 was able to do so (Figure 4c, d, S5d). Reduced expression of Cx43 at the plasma membrane was also observed in Dsg1-silenced 3D organotypic cultures when compared to controls (Figure S6a, b).

Dsg1 promotes GJ function through Cx43

We next used a dye transfer assay to test the functional impact of Dsg1 on GJ intercellular communication (GJIC), evaluating the cell-to-cell transfer of the GJ permeable dye Lucifer Yellow (LY) as an indicator of GJIC. NHEKs infected with GFP or FLAG-tagged-FLDsg1 were grown to confluence and cultured in 1.2 mM calcium containing media for 16 h, which is enough time to ensure that FL-Dsg1 is localized to the membrane, but not enough time for endogenous Dsg1 to be expressed (Figure 4e). Cells expressing FL-Dsg1 had significantly higher cell-to-cell LY dye transfer than controls (115.36+4.95 vs 68.2+4.26) (Figure 4f), indicating a functional role for Dsg1 in GJIC.

Plasma membrane-localized Cx43 was significantly higher in the FL-Dsg1 infected cells compared to GFP infected controls (7.08+1.32 vs 1.36+1.09), consistent with the idea that Dsg1 promotes GJIC through Cx43 (Figure 4g, h). To directly test the role of Cx43 in Dsg1-mediated GJIC, we silenced Cx43 using siRNA against Cx43 in NHEKs infected with FL-Dsg1, effectively reducing LY transfer compared with transfer in control FL-Dsg1 expressing NHEKs treated with non-targeting siRNA (siNT) (52.2+12.9 vs 111.9+15.2) (Figure 4 i, j, k).

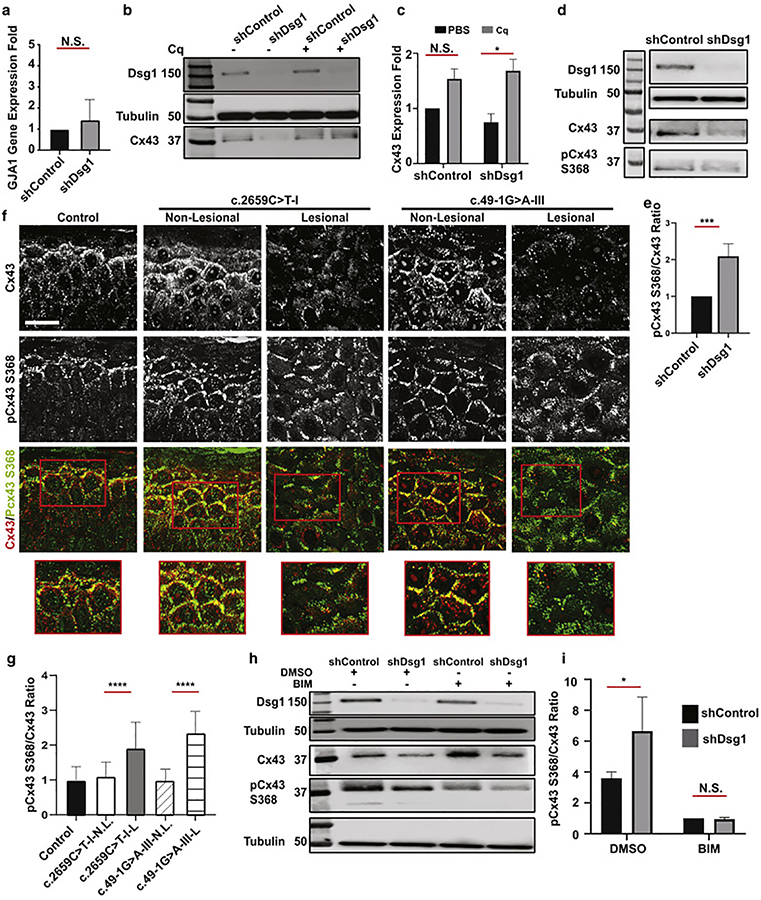

Dsg1 loss is associated with enhanced Cx43 degradation involving PKC-mediated phosphorylation of Cx43 Serine 368

We next determined whether Dsg1 regulates the expression of Cx43 at the mRNA or protein level. GJA1 mRNA expression was not reduced in shDsg1-compared to shControl-infected NHEKs (Figure 5a), suggesting that post-transcriptional regulation is involved. Cx43 and other GJ proteins have short half-lives, indicating high rates of remodeling and turnover (Laird, 1991, Lampe and Lau, 2004. Solan and Lampe, 2014). Cx43 turnover is tightly regulated, and mis-regulation contributes to pathogenicity (Fernandes et al., 2004, Kam et al., 2018). The lysosome is the main site of Cx43 degradation (Cone et al., 2014, Su et al., 2014). To test whether loss of Dsg1 results in Cx43 protein degradation, we treated shControl- and shDsg1-infected NHEKs with the lysosomal inhibitor chloroquine. Chloroquine increased Cx43 protein to comparable levels in control and shDsg1-expressing NHEKs, consistent with a role for Dsg1 in preventing Cx43 degradation (Figure 5b, c). Similar results were observed using Leupeptin, another lysosome inhibitor (Figure S6c).

Figure 5. Dsg1 loss associates with enhanced Cx43 degradation involving PKC-mediated phosphorylation of Cx43 Serine 368.

a. GJA1 gene expression in shControl or shDsg1infected NHEKs (n = 3. Error bars = mean ± SD, by two-tailed Student’s t test, N.S. = not significant). b. Immunoblot of Dsg1, Cx43 in shControl or shDsg1 infected NHEKs treated with PBS or100 μM chloroquine (Cq) for 16h (Tubulin used as a loading control. Representative of n = 3). c. Fold changes of total Cx43 from b. (Error bars = mean ± SD. *p = 0.03 by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test, N.S. = not significant). d. Immunoblot of Cx43, pCx43 S368 in NHEKs infected with shControl or shDsg1 harvested 72h after switch to high calcium medium (representative of n = 5). e. Fold changes in the ratio of pCx43 S368 to total Cx43 from d. (Error bars = mean ± SD. ***p = 0.0005 by two-tailed Student’s t test). f. Lesional and non-lesional skin from two patients with different Dsg1 mutations stained for total Cx43 and pCx43 S368 (scale bar = 30 mm). g. Quantification of plasma membrane pCx43 S368/Cx43 ratios from f. (n = 30 borders from each sample, Error bars = mean ± SD. ****p<0.0001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnet’s post hoc test). h. Immunoblot of total Cx43 and pCx43 S368 in NHEKs infected with shControl or shDsg1 retrovirus, harvested 72h after a switch to high calcium medium and following 1h treatment with DMSO, or the PKC inhibitor BIM (n = 3). i. Ratio of pCx43 S368 to total Cx43 from h. (* p=0.02 by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test, N.S. = not significant).

Phosphorylation of multiple serine residues at the C-terminus of Cx43 regulates GJ transport, assembly, and internalization; Cx43 phosphorylation is regulated by several signaling pathways (ERK, AKT, PKC) (Solan and Lampe, 2014). Phosphorylation of S325, S328, S330, S364/365, and S373 enhance GJIC, while phosphorylation of S255, S262, S279/282, and S368 downregulate Cx43 (Alstrom et al., 2015, Bao et al., 2004). We previously demonstrated that DP loss results in Cx43 degradation through Erk-dependent phosphorylation of S279/282 (Kam et al., 2018); therefore, we evaluated the level of phosphorylation at Cx43 residues S279/282 in shDsg1-infected NHEKs compared to shControl-infected NHEKs. There was no change in the level of pCx43 S279/282 phosphorylation (Figure S6d, e). PKC regulates internalization and degradation of Cx43 by phosphorylating S368 (Rivedeal et al., 2001, Cone et al., 2014, Su et al., 2014) and desmosomes have also been linked to PKC regulation (Johnson et al., 2014a), thus we next evaluated the PKC-dependent Cx43 phosphorylation site, S368. The ratio of pCx43 S368/total Cx43 was significantly higher in shDsg1-infected cells compared to shControl-infected NHEKs, suggesting Cx43 phosphorylation at that site leads to increased degradation secondarily to Dsg1 loss (Figure 5d, e).

We then stained skin biopsies obtained from SAM syndrome patients for pCx43 S368 to determine whether SAM syndrome-associated Dsg1 mutations correlated with increased pCx43 S368 phosphorylation in vivo (Figure 5f). A significantly higher ratio of pCx43 S368/Cx43 was observed in lesional patient skin compared to non-lesional and control skin (Figure 5g). Finally, we tested whether PKC inhibition with Bisindolylmaleimide-I (BIM) would reduce pCx43 S368 and upregulate total Cx43 expression in NHEKs infected with shControl- or shDsg1-expressing retroviruses. PKC inhibition significantly decreased the ratio of pCx43 S368/total Cx43 in the context of Dsg1 depletion (Figure 5h, i). In addition, we observed an increase in total Cx43 in BIM-treated controls, and recovery of total Cx43 in BIM-treated shDsg1 cells. Together, these data suggest that PKC-mediated phosphorylation of pCx43 S368 is responsible for Cx43 turnover downstream of Dsg1 loss.

DISCUSSION

In the present work, recognition of shared clinical phenotypes in patients with SAM syndrome and EKV led to the elucidation of a role for Dsg1 in Cx43 stabilization and GJ function in the epidermis. Supporting a role for Dsg1 in stabilizing Cx43, we observed a positive association between plasma membrane-localized Dsg1 and robust Cx43 intensity in non-lesional skin, while areas of Dsg1 loss were associated with decreased Cx43 intensity in lesional skin of SAM syndrome patients. In vitro, Dsg1 loss decreased Cx43 expression, which was rescued by ectopic Dsg1-FL expression, but not by constructs modeling SAM syndrome mutations. Ectopic expression of Dsg1-FL enhanced dye transfer between cells, which was prevented by Cx43 silencing. This observation supports a role for Dsg1 in promoting GJIC through regulation of Cx43 expression and localization in the connexon.

As desmosome components can regulate and scaffold PKC (Bass-Zubek et al., 2008; Johnson et al., 2014a) and desmosome instability can activate PKC (Osada et al., 1997), we hypothesized that PKC-mediated phosphorylation of Cx43 S368 regulates Cx43 turnover (Cone et al., 2014) downstream of Dsg1 loss. Indeed, Dsg1 loss was associated with an increased pCx43 S368/total Cx43 ratio both in genetically manipulated cells and in lesional skin of SAM syndrome patients. PKC inhibition blocked S368 phosphorylation, significantly reversing the pCx43 s368/total Cx43 ratio in Dsg1-depleted cells. Thus, disturbance of Dsg1 expression alters PKC signaling to impact GJs.

Desmosomal proteins have previously been reported to play roles in Cx43 dynamics in both the heart and skin. In fact, Cx43 is the main GJ protein affected by modulation of desmosomes (Oxford et al., 2007, Noorman et al., 2013, Asimaki et al. 2014, Patel et al., 2014, Kam et al., 2018). For instance, we previously showed that DP’s N-terminus interacts with end-binding (EB-1) protein to promote microtubule stabilization at the cell surface, associated with an increase in plasma membrane localized Cx43 in both cardiomyocytes and keratinocytes. Furthermore, N-terminal DP mutations associated with Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (AC) and skin fragility-wooly hair syndrome interfere with the DP-EB1 interaction, resulting in Cx43 mis-localization. This mis-localization is thought to be due to a failure of Cx43 to undergo plus-ended microtubule-mediated delivery of Cx43 to the membrane (Patel et al., 2014). We also previously demonstrated that loss of DP triggers ERK1/2-MAPK dependent phosphorylation of Cx43 at residues S279/S282, signaling the internalization and lysosomal degradation of the connexin (Kam et al. 2018). Other desmosomal proteins have also been shown to regulate Cx43 localization. For example, AC resulting from Dsg2 mutations was associated with Cx43 mis-localization (Ghemlich et al, 2012, Schlipp et al, 2014, Kant et al, 2015). Mis-localized Cx43 was observed in a zebrafish model of AC caused by a JUP (Junctional PG encoding gene) 2057del2 mutation (Asimaki et al., 2014) Thus, diverse mechanisms have evolved to mediate Cx43 positioning and function via desmosome molecules.

In light of these observations, we tested the extent to which Cx43 loss in SAM syndrome is caused directly by impaired Dsg1 or by a more general adhesion defect. Toward this end, we determined the expression and distribution of other junctional proteins, including DP, Dsc1, E-cadherin and β-catenin. All of these proteins were preserved in the skin of the SAM syndrome patients analyzed in this study (Figure S3), as well as in cell culture and epidermal raft models of Dsg1 loss (Figure S4). We further found no significant change in the adhesive properties of Dsg1-deficient NHEKs compared to controls, while DP-silencing increased monolayer fragility, as has been previously reported (Carbal et al, 2012). Consistent with these results, SAM syndrome patients do not typically present with blistering of the sort observed in toxin/autoantibody-mediated Dsg1 diseases like staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and pemphigus foliaceus (Amagai et al., 2010). While we do not rule out that other junctional proteins contribute to GJ function, Dsg1 clearly plays a critical role in controlling Cx43 under the in vitro and in vivo conditions studied here (Figure 4). Together with our previous observations, Dsg1 and DP, through distinct mechanisms, both inhibit plasma membrane turnover of Cx43.

So far, SAM syndrome has been reported in 13 patients from 9 families (Samuelov et al., 2013, Has et al., 2014, Cheng et al., 2015, Schlipf et al., 2016, Danescu et al., 2016, Lee et al., 2016, Taiber et al., 2018). The patients share features of dermatitis, palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK), and allergy, yet present with phenotypic variability, even between patients harboring the same mutation (Cheng et al., 2015). In this study, we showed differences in Dsg1 expression at the same anatomic location and within the same patient when comparing samples obtained from lesional and non-lesional areas. We show that at least some SAM syndrome-associated Dsg1 mutants are expressed, and are capable of localization at the cell membrane.

It is known that physiologic expression of Dsg1 is impaired by external stimuli such as UV irradiation (Johnson et al, 2014b), S. aureus-stimulated serine proteases (Williams et al., 2017) and inflammatory cytokines (Davis et al., 2016), the latter which are expressed by keratinocytes isolated from SAM syndrome patients (Samuelov et al., 2013). It is possible that mutant Dsg1 proteins may be more susceptible to degradation or turnover compared with wild type Dsg1. Future delineation of the detailed mechanisms underlying Dsg1 turnover could provide new therapeutic targets for SAM syndrome patients.

Shared clinical features between SAM syndrome and EKV patients led us to uncover molecular and mechanistic connections between Dsg1 and Cx43. However, even though Cx43 is reduced in areas of Dsg1 loss in lesional biopsies from patients with c.1861delG Dsg1 mutations, these patients present with sustained erythroderma, rather than EKV-like symptoms. It may be the case that additional epidermal barrier components were compromised in these patients, resulting in the observed differences in phenotype.

The role of Cx43 in epidermal differentiation is still obscure. Cx43 KD caused impaired differentiation in 3D epidermal rafts (Langlois et al., 2007). A truncated Cx43 variant caused lethal permeable epidermis in a knock-in mouse model (Maass et al., 2004), despite the preserved ability of the truncated protein to form functional GJs. This implies that Cx43’s role in epidermal barrier formation may go beyond GJIC. Cx43 interacts with other important components of epidermal differentiation such as the tight junction protein Zonula Occludens 1 (ZO1), and β-Catenin (Thevenin et al., 2017, Leithe et al., 2018). Hence, Dsg1-governed stabilization of Cx43 might contribute directly to the establishment of an efficient epidermal barrier, and its loss may result in perturbed barrier as occurs in SAM syndrome.

In summary, here we demonstrate a role for Dsg1 in stabilizing the GJ protein Cx43, strengthening the evidence that desmosomes and GJs work together to govern proper epidermal architecture and barrier formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients were recruited from the Department of Dermatology of Emek Medical Center (EMC), Afula, Israel during the years 2016–2018. Some of the patients were reported previously (Samuelov et al., 2013, Taiber et al., 2018). Patients or their legal guardians signed written informed consents prior to their inclusion in the study, according to a protocol approved by the EMC (IRB Protocol #0086–15). Patients or their legal guardians signed written informed consents for publication of clinical photos. De-identified control skin biopsies were obtained from volunteers that signed written informed consents and the biopsies were provided by the Skin Biology and Diseases Resource-Based Center of Northwestern University (IRB Protocol#STU00009443).

Cell culture

Primary normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) were obtained through the Skin Biology and Diseases Resource-Based Center of Northwestern University, where mycoplasma testing is routinely performed. The NHEKs were isolated from human foreskin as previously described (Halbert et al., 1992) and grown in M154 media (Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 0.07 mM CaCl2, human keratinocyte growth supplement (HKGS), and gentamicin/amphotericin B solution (Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Keratinocytes were infected as described in Supplemental Materials with supernatants from Phoenix cells that produce retroviruses (provided by G. Nolan, Stanford University, Stanford CA) as previously described (Getsios et al., 2004). Keratinocytes were then grown to confluency in M154 media (0.07mM CaCl2) and switched to M154 media supplemented with 1.2 mM CaCl2 for 72h to induce differentiation. To test inhibition of lysosomal degradation NHEKs were differentiated for 72h and then treated overnight with 100 μM Chloroquine (lysosomal inhibitor) (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) or 200 μM Leupeptin (Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO) vs PBS as control. To inhibit PKC activity, NHEKs differentiated for 72h were treated for 1h with 12.5 mM BIM (PKC inhibitor) (Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or DMSO as a control.

DNA constructs

LZRS-Non Target (NT)-GFP (shControl), LZRS-GFP (GFP), LZRS-Dsg1-FL-FLAG (FL), and LZRS-shDsg1-GFP (shDsg1) were generated as described (Getsios et al., 2004). LZRS-Dsg1-Δ909-FLAG (Δ909) was generated as described (Nekrasova et al., 2018). LZRS-Dsg1-ΔExon2--FLAG (ΔEx2) was generated to correspond with the human Dsg1 mutation c.49–1 G>A reported by our group (Samuelov et al., 2013). This mutation was shown to cause in-frame skipping of exon 2 in two patients with SAM syndrome. The construct was made using the PCR product of full length Dsg1 NM_001942.2: nucleotides 213–3359 with deletion of exon 2, corresponding to nucleotides 261–296 and ligating this product to a C-terminal flag epitope followed by a stop codon. The resulting ΔEx2-Dsg1-FLAG was then cloned into the pLZRS vector (provided by M. Denning, Loyola University, Chicago, IL). Briefly, NHEKs were infected with shControl, shDsg1 or with dual infection of shDsg1 to deplete endogenous expression of wild type Dsg1 plus constructs-FL, (Δ909), or (ΔEx2). Further details about infection procedures are provided in Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Antibodies

Antibodies utilized in this study are listed in Table S1.

Western blotting

For analysis of protein expression levels, cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed in urea sample buffer (10 M deionized urea, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10% glycerol, 60 mM Tris, pH 6.8, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol). Total protein concentrations were equalized, and samples were run on 7.5–10% SDS-PAGE gels. Gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes to be probed with primary and secondary antibodies against proteins of interest (Table S1). Chemiluminescent imaging was performed using an Odyssey Fc imaging system and densitometry was performed using Fc image studio (iS) version 5.x (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). Densitometry quantification was normalized using GAPDH or Tubulin as loading controls. Full blots are presented in Figure S7 and S8.

Immunofluorescence of cells and paraffin embedded skin sections

Cells grown on glass coverslips were washed in PBS, fixed using 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA), and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes, at room temperature. Primary antibodies diluted in 0.5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS were added to coverslips and incubated at 37°C in a humidified chamber for 1h followed by multiple washes in PBS. Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibodies diluted 1:300 in 0.5% BSA in PBS were added and incubated at 37°C for 30 min followed by PBS washes and mounting of coverslips in ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Thermo-Fisher, Waltham, MA). Formalin fixed tissues were processed by the Northwestern University Skin Biology and Disease Resource-Based Center. Paraffin-embedded sections were baked, deparaffinized in sequential xylene and ethanol washes, followed by permeabilization as described above. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating samples to 95°C in 0.01 M citrate buffer. Sections were blocked in 0.5% BSA in PBS and incubated with primary antibodies for 16h at 4°C, followed by PBS washes. Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibodies were added and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After mounting in ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), sections were visualized as described in Supplemental Materials and Methods.

qPCR of Cx43

The qPCR procedures utilized to quantify Cx43 mRNA were according to the manufacturer’s instructions and are described in Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Statistics

Statistics were analyzed using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego,CA). Biological replicates were quantified separately and compared as repeated measures. All quantifications are presented as mean ±SD. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s post hoc analysis was used for multiple comparisons. For data comparing two conditions, statistical differences were analyzed with a two-tailed Student’s t test. For data comparing two conditions at baseline and after treatment, we used two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post hoc tests. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

For analysis presented as fold change (bar graphs), the mean of data from control samples was assigned a value of 1, and all other samples were calculated relative to the control.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This work was supported by NIH/NIAMS R01 AR041836 and NIH R37 AR43380 to KJG, and by a Fulbright postdoctoral fellowship grant to ECB. MH was supported by an NIH T32 Training Grant (T32 CA009560). Additional support was provided by the JL Mayberry endowment to KJG. We acknowledge support and materials from the Northwestern University Skin Biology and Diseases Resource-Based Center supported by 5P30AR057216. We thank Chen Gafni and Efrat Mamluk from “Emek” Medical Center for their assistance.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- AC

Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy

- Cx43

Connexin 43

- Dsc1

Desmocollin 1

- Dsg1

Desmoglein 1

- Dsg2

Desmoglein 2

- DP

Desmoplakin

- EKV

Erythrokeratodermia Variabilis

- GJ

Gap junctions

- GJIC

Gap junction intercellular communication

- PG

Plakoglobin

- NHEKs

Normal human epidermal keratinocytes

- SAM

Severe dermatitis, multiple Allergies, and Metabolic wasting

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors state no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT: No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- Alstrom JS, Hansen DB, Nielsen MS, MacAulay N. Isoform-specific phosphorylation-dependent regulation of connexin hemichannels. J Neurophysiol 2015;114(5):3014–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amagai M. Autoimmune and infectious skin diseases that target desmogleins. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 2010;86(5):524–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asimaki A, Tandri H, Huang H, Halushka MK, Gautam S, Basso C et al. A new diagnostic test for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2009;360(11):1075–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnette C, Koetsier JL, Hoover P, Getsios S, Green KJ. In Vitro Model of the Epidermis: Connecting Protein Function to 3D Structure. Methods Enzymol 2016;569:287–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asimaki A, Kapoor S, Plovie E, Karin Arndt A, Adams E, Liu Z, et al. Identification of a new modulator of the intercalated disc in a zebrafish model of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med 2014;6(240):240ra74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X, Reuss L, Altenberg GA. Regulation of purified and reconstituted connexin 43 hemichannels by protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation of Serine 368. J Biol Chem 2004;279(19):20058–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass-Zubek AE, Hobbs RP, Amargo EV, Garcia NJ, Hsieh SN, Chen X et al. Plakophilin 2: a critical scaffold for PKC alpha that regulates intercellular junction assembly. J Cell Biol 2008;181(4):605–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer EC, Berthoud VM. Gap junction gene and protein families: Connexins, innexins, and pannexins. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2018;1860(1):5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden LM, Craiglow BG, Zhou J, Hu R, Loring EC, Morel KD, et al. Dominant De Novo Mutations in GJA1 Cause Erythrokeratodermia Variabilis et Progressiva, without Features of Oculodentodigital Dysplasia. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135(6):1540–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden LM, Kam CY, Hernandez-Martin A, Zhou J, Craiglow BG, Sidbury R, et al. Dominant de novo DSP mutations cause erythrokeratodermia-cardiomyopathy syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 2016;25(2):348–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng R, Yan M, Ni C, Zhang J, Li M, Yao Z. Report of Chinese family with severe dermatitis, multiple allergies and metabolic wasting syndrome caused by novel homozygous desmoglein-1 gene mutation. J Dermatol 2016;43(10):1201–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone AC, Cavin G, Ambrosi C, Hakozaki H, Wu-Zhang AX, Kunkel MT, et al. Protein kinase C delta-mediated phosphorylation of Connexin43 gap junction channels causes movement within gap junctions followed by vesicle internalization and protein degradation. J Biol Chem 2014;289(13):8781–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dănescu S, Leppert J, Cosgarea R, Zurac S, Pop S, Baican A, et al. Compound heterozygosity for dominant and recessive DSG1 mutations in a patient with atypical SAM syndrome (severe dermatitis, multiple allergies, metabolic wasting). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31(3):e144–e146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BP, Stucke EM, Khorki ME, Litosh VA, Rymer JK, Rochman M et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis-linked calpain 14 is an IL-13-induced protease that mediates esophageal epithelial barrier impairment. JCI Insight 2016; 4(1): e86355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes R, Girao H, Pereira P. High glucose down-regulates intercellular communication in retinal endothelial cells by enhancing degradation of connexin 43 by a proteasome-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 2004;279(26):27219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehmlich K, Asimaki A, Cahill TJ, Ehler E, Syrris P, Zachara E et al. Novel missense mutations in exon 15 of desmoglein-2: Role of the intracellular cadherin segment in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy? Heart Rhythm 2010; 7(10):1446–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getsios S, Amargo EV, Dusek RL, Ishii K, Sheu L, Godsel LM, et al. Coordinated expression of desmoglein 1 and desmocollin 1 regulates intercellular adhesion. Differentiation 2004;72(8):419–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbert CL, Demers GW, Galloway DA. The E6 and E7 genes of human papillomavirus type 6 have weak immortalizing activity in human epithelial cells. J Virol 1992;66(4):2125–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Has C, Jakob T, He Y, Kiritsi D, Hausser I, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Loss of desmoglein 1 associated with palmoplantar keratoderma, dermatitis and multiple allergies. Br J Dermatol 2015;172(1):257–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a.Johnson JL, Najor NA, Green KJ. Desmosomes: Regulators of Cellular Signaling and Adhesion in Epidermal Health and Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014; 4(11): a015297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- b.Johnson JL Koetsier JL, Sirico A, Agidi AT, Antonini D, Missero C, et al. The desmosomal protein desmoglein 1 aids recovery of epidermal differentiation after acute UV light exposure. J Invest Dermatol 2014;134(8): 2154–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam CY, Dubash AD, Magistrati E, Polo S, Satchell KJF, Sheikh F, et al. Desmoplakin maintains gap junctions by inhibiting Ras/MAPK and lysosomal degradation of connexin-43. J Cell Biol 2018;217(9):3219–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kant S, Holthöfer B, Magin TM, Krusche CA, Leube RE. Desmoglein 2-Dependent Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy Is Caused by a Loss of Adhesive Function. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2015;8:553–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai-Cheong JE, Arita K, McGrath JA. Genetic diseases of junctions. J Invest Dermatol 2007;127(12):2713–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird DW. Closing the gap on autosomal dominant connexin-26 and connexin-43 mutants linked to human disease. J Biol Chem 2008;283(6):2997–3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird DW, Puranam KL, Revel JP. Turnover and phosphorylation dynamics of connexin43 gap junction protein in cultured cardiac myocytes. Biochem J 1991;273(Pt 1):67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe PD, Lau AF. The effects of connexin phosphorylation on gap junctional communication. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2004;36(7):1171–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois S, Maher AC, Manias JL, Shao Q, Kidder GM, Laird DW. Connexin levels regulate keratinocyte differentiation in the epidermis. J Biol Chem 2007;282(41):30171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JYW, Farag A, Tawdy A, Liu L, Michael M, Rashidghamat E, et al. Homozygous acceptor splice site mutation in DSG1 disrupts plakoglobin localization and results in keratoderma and skin fragility. J Dermatol Sci 2018;89(2):198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leithe E, Mesnil M, Aasen T. The connexin 43 C-terminus: A tail of many tales. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2018;1860(1):48–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maass K, Ghanem A, Kim JS, Saathoff M, Urschel S, Kirfel G, et al. Defective epidermal barrier in neonatal mice lacking the C-terminal region of connexin43. Mol Biol Cell 2004;15(10):4597–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macari F, Landau M, Cousin P, Mevorah B, Brenner S, Pannizon R, et al. Mutation in the Gene for Connexin 30.3 in a Family with Erythrokeratodermia Variabilis. Am J Hum Gen 2000;67(5):1296–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PE, Easton JA, Hodgins MB, Wright CS. Connexins: sensors of epidermal integrity that are therapeutic targets. FEBS Lett 2014;588(8):1304–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mese G, Richard G, White TW. Gap junctions: basic structure and function. J Invest Dermatol 2007;127(11):2516–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noorman M, Hakim S, Kessler E, Groeneweg J, Cox M, Asimaki A. Remodeling of the cardiac sodium channel, connexin43, and plakoglobin at the intercalated disk in patients with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rythem 2013;10(3):412–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada K, Seishima M, Kitajima Y. Pemphigus IgG activates and translocates protein kinase C from the cytosol to the particulate/cytoskeleton fractions in human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 1997;108(4):482–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel DM, Dubash AD, Kreitzer G, Green KJ. Disease mutations in desmoplakin inhibit Cx43 membrane targeting mediated by desmoplakin-EB1 interactions. J Cell Biol 2014;206(6):779–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford EM, Musa H, Maass K, Coombs W, Taffet SM, Delmar M. Connexin43 remodeling caused by inhibition of plakophilin-2 expression in cardiac cells. Circ Res 2007;101(7):703–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard G, Smith LE, Bailey RA, Itin P, Hohl D, Epstein EH, et al. Mutations in the human connexin gene GJB3 cause erythrokeratodermia variabilis. Nat Genet 1998;20(4):366–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivedal E, Opsahl H. Role of PKC and MAP kinase in EGF- and TPA-induced connexin43 phosphorylation and inhibition of gap junction intercellular communication in rat liver epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis 2001;22(9):1543–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlipp A, Schinner C, Spindler V, Vielmuth F, Gehmlich K, Syrris P, et al. Desmoglein-2 interaction is crucial for cardiomyocyte cohesion and function. Cardiovasc Res 2014. 1;104(2):245–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelov L, Sarig O, Harmon RM, Rapaport D, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Isakov O, et al. Desmoglein 1 deficiency results in severe dermatitis, multiple allergies and metabolic wasting. Nat Genet 2013;45(10):1244–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlipf NA, Vahlquist A, Teigen N, Virtanen M, Dragomir A, Fismen S, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies novel autosomal recessive DSG1 mutations associated with mild SAM syndrome. Br J Dermatol 2016;174(2):444–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnichels M, Worsdorfer P, Dobrowolski R, Markopoulos C, Kretz M, Schwarz G, et al. The connexin31 F137L mutant mouse as a model for the human skin disease erythrokeratodermia variabilis (EKV). Hum Mol Genet 2007;16(10):1216–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CA, Kelsell DP. Key functions for gap junctions in skin and hearing. Biochem J 2011;438(2):245–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuja Z, Li L, Gupta S, Mese G, White TW. Connexin26 Mutations Causing Palmoplantar Keratoderma and Deafness Interact with Connexin43, Modifying Gap Junction and Hemichannel Properties. J Invest Dermatol 2016;136(1):225–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solan JL, Lampe PD. Specific Cx43 phosphorylation events regulate gap junction turnover in vivo. FEBS Lett 2014;588(8):1423–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solan JL, Lampe PD. Spatio-temporal regulation of connexin43 phosphorylation and gap junction dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2018;1860(1):83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su V, Lau AF. Connexins: Mechanisms regulating protein levels and intercellular Communication. FEBS Lett 2014; 588:1212–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taiber S, Samuelov L, Mohamad J, Barak EC, Sarig O, Shalev SA, et al. SAM syndrome is characterized by extensive phenotypic heterogeneity. Exp Dermatol 2018;27(7):787–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevenin AF, Margraf RA, Fisher CG, Kells-Andrews RM, Falk MM. Phosphorylation regulates connexin43/ZO-1 binding and release, an important step in gap junction turnover. Mol Biol Cell 2017;28(25):3595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschke J, Bruggeman P, Baumgartner W, Zillikens D, Drenckhahn D. Pemphigus foliaceus IgG causes dissociation of desmoglein 1-containing junctions without blocking desmoglein 1 transinteraction. J Clin Invest 2005;115(11):3157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MR, Nakatsuji T, Sanford JA, Vrbanac AF, Gallo RL. Staphylococcus aureus Induces Increased Serine Protease Activity in Keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2017;137(2):377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.