Abstract

As polytrauma cases are on the rise, a large number of patients presents with temporal bone fractures, which can result in various types of injuries varying from trivial to more serious injuries. Early diagnosis and appropriate management in required in case of serious injuries for a better outcome. The aim of my study is to study the incidence, the different injuries occurring and the effect of early diagnosis on hearing loss. Patients coming to our emergency department with polytrauma are studied and clinically evaluated for any temporal bone injuries. Based on the type of injuries audiological and radiological studies are done. And if required, biochemical tests like CSF analysis will be done. Also hearing assessment will be done as early as possible and appropriate treatment required will be started. The outcome is then assessed and followed up on a regular basis. In our study there were 90 patients with temporal bone fracture out of the 2748 polytrauma cases. The incidence was calculated to be 32 per 1000 cases. 69 patients (76.7%) had longitudinal fracture of temporal bone; 13 patients (14.4%) had transverse fracture; 2 patients (2.2%) had oblique fractures and 6 patients (6.6%) had comminuted fractures. Hearing loss was found to be the most common injury seen in 56 patients (62.2%). Of which 30 (53.5%) had conductive hearing loss (CHL); 9 (16%) had sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL); 17 had mixed hearing loss (MHL). 27 (90%) out of 30 patients with CHL showed improvement in hearing. Out of the 26 patients with SNHL and MHL, 22 patients (84.61%) showed improvement. 5 out of 6 with immediate onset facial palsy and 6 out of 8 with late onset facial palsy showed improvement. The hearing outcome in our study was found to be much better than the previous year which shows that the difference might be due to the early diagnosis and management. In our study hearing improvement was noted in most patients with hearing loss when compared to the previous year, which may have been due to the detection of the injuries at the earliest and managing the same with appropriate treatment modalities.

Keywords: Hearing loss, Otic capsule, Facial palsy, Temporal bone

Introduction

Temporal bone is the only bone which lodges a sensory organ within. It serves as a rigid boundary of the middle and posterior cranial fossae, acts as an important gateway between the intracranial contents and the head and neck, and acts as a receiver for information essential to proper hearing and balance. It houses many vital structures, including the cochlear and vestibular end organs, the facial nerve, the carotid artery, and the jugular vein [1]. Trauma to the temporal bone may injure any of the above structures.

Most temporal bone fractures are a result of high energy blunt head trauma [1]. As the polytrauma cases are on the rise we have a large number of patients with temporal bone fractures attending the emergency department [2]. Yet trauma to temporal bone is often overlooked in the initial evaluation.

There are a variety of injuries occurring in relation to the ear ranging from trivial injury of the external auditory canal (EAC) to facial nerve involvement and CSF (Cerebrospinal fluid) otorrhoea.

Injuries involving the external auditory canal-laceration and bleeding from ear canal

Injuries involving middle ear-tympanic membrane perforations, ossicular damage and hemotympanum (causing conductive hearing loss)

Injuries involving the inner ear-labyrinthine concussion, Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), perilymphatic leak, facial nerve injuries (causing giddiness and Sensorineural hearing loss(SNHL)

Injuries involving the dura and cranial cavity causing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhoea

Of the above given injuries facial nerve injuries, sensorineural hearing loss, perilymphatic leak and CSF otorrhea are grave injuries [3, 4]. And initial evaluation is necessary to recognize this. In acute trauma these are overlooked due to other serious underlying injuries and the level of consciousness of the patient. But once patient gets stabilized these injuries become obvious. But there is a considerable time lapse between time of injury and identification of the injury. These injuries should be identified as early as possible with frequent follow up. Delay in identifying facial nerve injuries and SNHL may have a poor outcome after treatment [5]. Hearing loss can be conductive or SNHL.

CHL can be due to

Hemotympanum

Tympanic membrane perforation

Ossicular chain disruption

SNHL can be due to

Disruption of the membranous labyrinth

Avulsion or trauma to the cochlear nerve

Interruption of the cochlear blood supply

Hemorrhage into the cochlea

Perilymphatic fistulas

Obstruction of the endolymphatic duct by the temporal bone fracture

SNHL requires immediate attention [6]. But is difficult to assess unless patient is well stabilized. If identified early can be started on steroid treatment to improve the outcome. Hence this study also aims to find whether early identification of hearing loss has an effect on its outcome. So the preventive measure to decrease the impact of trauma on outcome is to deliberately look for such injuries and address them at the earliest. Hearing loss can be assessed once the patient is stable. Mostly due to the unconscious status of the patient and other severe injuries requiring urgent intervention there occurs a delay in otolaryngologic evaluation and management. This study is aimed to study the regional incidence of temporal bone involvement in polytrauma patient, to analyse different type of injuries involving the temporal bone, to prioritise the requirements of appropriate treatment and to determine the need for early expert involvement, to study the impact of delay in initializing the treatment and its outcome on hearing.

Materials and Methods

Study Design Prospective study

Study Setting The study is carried out among polytrauma patients presenting to the emergency department of Jubilee Mission Medical College and Research institute, Thrissur during a period of 12 months.

Study Period March 2017–March 2018 (12 months)

Sample Size All polytrauma patients with temporal bone involvement presenting to the emergency department during a time period of 12 months.

Inclusion Criteria All polytrauma patients with temporal bone involvement presenting to the emergency department.

Exclusion Criteria Patients who expires or get transferred out.

Methods of Data Collection Patients coming to our emergency department are studied and clinically evaluated for any temporal bone injuries. The total number of polytrauma cases were collected to calculate the regional incidence of temporal bone fractures. After obtaining demographic data, thorough history was taken eliciting the cause and the mode of injury. Clinical evaluation included general physical examination and ENT evaluation. Examination of ear was done to look for any injuries. Facial nerve function was also assessed. Age, gender distribution, side of fracture, etiology of injuries, presence of blood otorrhea, CSF otorrhea, tympanic membrane perforation, hearing loss (conductive, sensorineural or mixed), hemotympanum, and facial nerve palsies, computerized tomography (CT) reports, and follow-up results were evaluated. The collected data were then analyzed and compared with the literature series. Patients were followed up daily. Audiological evaluation with the help of tuning fork and pure tone audiogram was done as soon as the patient was stable. Appropriate treatment was given to those patients detected to have hearing loss. The outcome was later assessed by doing a repeat audiogram. Patient was followed up on a daily basis till discharge and monitored for development of any symptoms like hearing loss, vertigo, facial palsy etc. Based on the type of injuries, further investigations were done. In case of suspected CSF otorrhea biochemical tests were done to confirm the same.

Facial nerve functions were assessed when the patient presents to the emergency department and also during the daily follow up. Development of delayed onset facial palsy was looked for. Steroid treatment, physiotherapy and other measures were taken for treatment of facial palsy. And the improvement in facial palsy was also followed up. Further radiological investigations like HRCT temporal bone were taken in some cases, especially in those with facial palsy and hearing loss. HRCT was taken to know the type of fracture, whether facial canal has been involved and to look for any ossicular discontinuity. In those presenting with vertigo, nystagmus was checked for and hallpike maneuver was done to rule out BPPV.

To study the effect of early diagnosis on hearing loss, a comparison was done between the improvements in hearing in our study with that of the previous year. Data of the previous year were collected from the records and case sheets.

Results

There were a total of 90 cases of temporal bone fracures out of the 2748 polytrauma cases. The incidence was calculated to be 32 per 1000 cases. There were 76 males and 14 females. Youngest patient was 4 years and oldest patient 80 years old, with a mean age of 34.32 years and a standard deviation of 17.39. There were 85 cases of unilateral temporal bone fracture and 5 bilateral cases. Of the 85 cases, 51 patients had left sided fracture and 34 had right sided fracture. Majority of temporal bone fractures were caused by RTA—60 cases (66.7%). There were 14 cases (15.6%) were it was caused by RTA in an unhelemted rider. In 8 cases (8.9%) it was due to fall from height, in 4 cases (4.4%) it was due to slip and fall, in 3 cases (3.3%) it was due to assault and there was 1 case (1.1%) of sports injury (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Bar diagram showing the causes of trauma

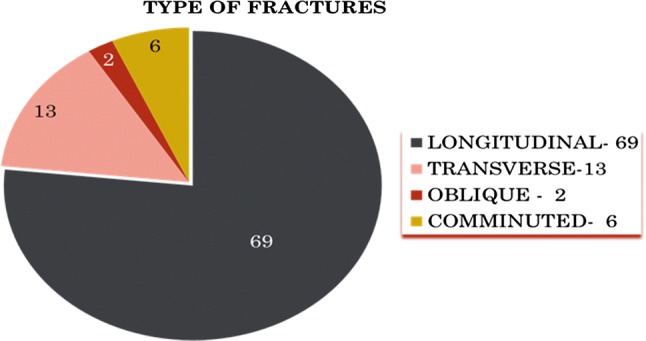

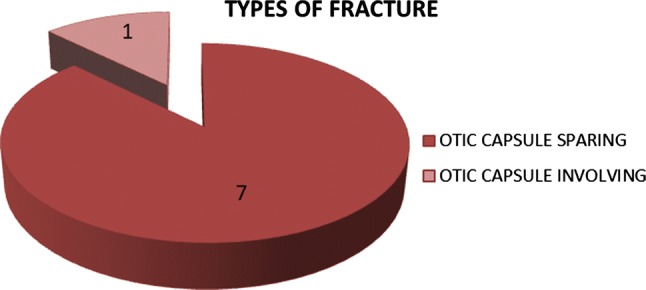

Based on older classification, 69 patients (76.7%) had longitudinal fracture of temporal bone. 13 patients (14.4%) had transverse fracture; 2 patients (2.2%) had oblique fractures and 6 patients (6.6%) had comminuted fractures (Fig. 2). Based on the newer classification, 86% patients had otic capsule sparing type of fracture, where as 14% had a capsule involving type of fracture (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Pie diagram showing types of fractures—old classification

Fig. 3.

Pie diagram showing types of fractures—new classification

Majority of the patients—56 patients (62.2%) complained of hearing loss. 9 patients (10%) complained of tinnitus and 15 patients (16.6%) complained of vertigo. Of the 15 patients, 11 patients (12.2%) had peripheral vertigo. Hearing loss was found to be the most common injury (56 patients). The other injuries were: hemotympanum in 25 patients, EAC laceration in 21 patients, TM perforation in 9 patients, CSF otorrhea in 5 patients, Ossicular discontinuity in 3 patients, Immediate onset facial palsy in 6 patients and late onset facial palsy in 8 patients (Table 1). There were 60 patients (66.7%) who had intracranial injuries associated with temporal bone fracture.

Table 1.

Showing types of injuries

| Type of injury | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Hearing loss | 56 | 62.2 |

| 2. | Hemotympanum | 25 | 27.8 |

| 3. | EAC laceration | 21 | 23.3 |

| 3. | TM perforation | 9 | 10 |

| 4. | CSF otorrhea | 5 | 5.6 |

| 5. | Ossicular discontinuity | 3 | 3.3 |

| 6. | Immediate onset facial palsy | 6 | 6.7 |

| 7. | Late onset facial palsy | 8 | 8.9 |

There were a total of 56 patients with hearing loss in our study. Of which 30 patients (53.5%) had conductive hearing loss; 9 patients (16.07%) had SNHL; 17 patients (30.3%) had MHL. Appropriate treatment were given for these patients. Steroid treatment was given to 23 patients among the 26 patients with SNHL and MHL. PTA was taken post treatment to look for any improvement in hearing. 26 patient with CHL showed improvement in hearing. Out of the 26 patients with SNHL and MHL 22 showed improvement.

Conductive hearing loss was seen in 30 patients. Of which 27 patients (90%) showed improvement. 3 patients (10%) did not show improvement. The improvement of CHL was statistically confirmed by applying the paired t test. There was a mean improvement of 13.07 db between the pre and post treatment PTA. And the p value was found to be < 0.001, hence statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Showing improvement in CHL

| n | Mean (db) | SD | Mean improvement | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment PTA | 30 | 36.980 | 10.20 | 13.077 | < 0.001 |

| Post treatment PTA | 30 | 23.903 | 7.66 |

There were 17 patients with MHL and 9 patients with SNHL. Improvement in hearing was noted in 22 patients. The improvement of hearing was statistically confirmed by applying the paired t test. There was a mean improvement of 12.375 db between the pre and post treatment PTA. And the p value was found to be < 0.001, hence statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Showing improvement in SNHL and MHL

| n | Mean (db) | SD | Mean improvement | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment PTA | 26 | 43.958 | 16.02 | 12.375 | < 0.001 |

| Post treatment PTA | 26 | 31.583 | 13.09 |

Steroid treatment was given for 23 patients and improvement was noted in 20 patients. The improvement of hearing was statistically confirmed by applying the paired t test. There was a mean improvement of 12.714 db between the pre and post treatment PTA. And the p value was found to be < 0.001, hence statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 4.

Showing effect of steroids in treatment of hearing loss

| n | Mean (db) | SD | Mean improvement | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre treatment PTA | 23 | 44.523 | 16.764 | 12.714 | < 0.001 |

| Post treatment PTA | 23 | 31.809 | 13.387 |

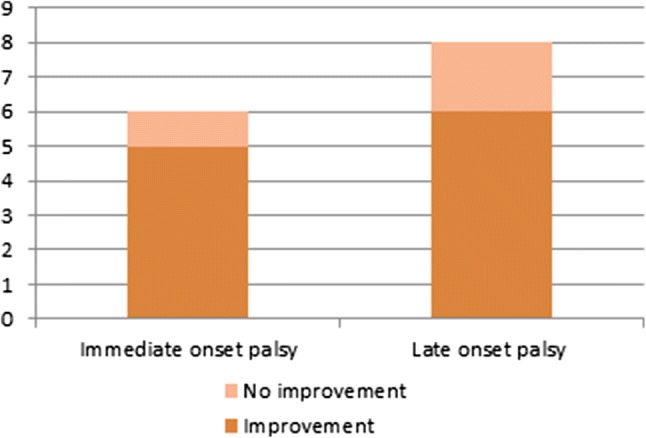

There were 14 patient with facial palsy of which 6 patients (6.7%) had immediate onset facial palsy and 8 patients (8.9%) had late onset facial palsy. Steroid treatment, physiotherapy were given for the patients with facial palsy and 2 patients underwent facial nerve decompression. 5 patients with immediate onset facial palsy showed improvement (83.3%). And 6 patients with late onset facial palsy showed improvement (75%) (Fig. 4). Out of these 5 (35.7%) patients had transverse type of temporal bone fracture and 9 (64.28%) patients had longitudinal fracture.

Fig. 4.

Bar chart showing improvement in facial palsy

Out of the 30 conductive hearing loss patients, 21 (70%) patients had longitudinal fracture, 4 (13.3%) patients had transverse fractures, 3 (10%) patients had comminuted fractures and 2 (6%) patients had oblique fractures. Out of the 9 SNHL (sensorineural hearing loss) patients, 7(77.7%) patients had longitudinal fracture, 1 (11.1%) patient had transverse fracture and 1 (11.1%) patient had comminuted fracture. And out of the 17 MHL (mixed hearing loss) patients, 10(58.8%) patients had longitudinal fracture, 6 (35.29%) patients had transverse fractures and 1 (5.8%) patient had comminuted fracture (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Bar diagram showing hearing loss and type of fractures

To study the effect of early diagnosis and treatment on hearing loss, we compared similar cases of temporal bone fractures of the previous year and the outcome of hearing in both the groups. During the previous year (March 2016 to March 2017), a total of 54 cases of temporal bone fractures were there. Of this 31 patients had hearing loss. 11 patients showed improvement and 20 patients showed no improvement. Using the Chi square test, p value was found to be < 0.0001. This shows that the association between groups and outcomes is considered to be extremely statistically significant. From this study it shows that the improvement in hearing is much better in the present year when compared to the previous year. And the difference in the outcome between the two groups could be due to the early diagnosis and management. So the recognition of hearing loss at the earliest and starting treatment at the earliest has a better outcome on hearing.

Discussion

With polytrauma cases on the rise, we have a large number of patients with temporal bone fractures attending the emergency department. Yet trauma to temporal bone is often overlooked in the initial evaluation. There are a variety of injuries occurring in relation to the ear ranging from trivial injury of the external auditory canal (EAC) to facial nerve involvement and CSF (Cerebrospinal fluid) otorrhoea. In this study, 90 patients had temporal bone fractures out of 2748 polytrauma cases. All the 90 patients were clinically evaluated. The incidence was calculated to be 32 per 1000 cases. In a study conducted by Brodie et al. shows temporal bone injury in 14–22% of patients with skull fractures. The male female ratio obtained in our study was 5.42:1. As compared with study by K. Jack Momose et al. where the ratio was 2.3:1 [7].

In our study, majority of temporal bone fractures were caused by RTA—60 cases (66.7%). There were 14 cases (15.6%) were it was caused by RTA in an unhelemted rider. Similar to study done by Yalciner et al. traffic accidents were found to be the most common cause of temporal bone fracture accounting to 54.54% cases [8] and in another study by Z Amin et al. motor vehicle accident were seen in 85.9% cases [9]. RTA is the most common cause for temporal bone fractures. Simple measures like wearing helmets and seat belts, careful driving, taking safety measures can reduce the number of such injuries.

In our study, 69 patients (76.7%) had longitudinal fracture,13 (14.4%) had transverse fracture; 2 (2.2%) had oblique fractures and 6 patients (6.6%) had comminuted fractures and newer classification, 86% patients had otic capsule sparing type of fracture, whereas 14% had an capsule involving type of fracture. Compared prospective study by Nagaraj et al. 33 cases had longitudinal or oblique fractures, while 12 had transverse fractures [10] and in a retrospective study by Z Amin et al. 86% patients had otic capsule sparing type of fracture, whereas 14% had an capsule involving type of fracture [9].

Majority of the patients—56 patients (62.2%) complained of hearing loss, hemotympanum in 25 patients (27.8%), EAC laceration in 21 patients(23.3%), TM perforation in 9 patients(10%), Similar results were found in the study by Nagaraj et al. with hearing loss being the most common injury.

30 (53.5%) of 56 patients had CHL, 9 patients (16%) had SNHL; 17 patients had MHL. There were 64.9% cases of CHL, and 5.4% cases of SNHL in the study by Yalciner et al. [8] Steroid treatment was given for 23 patients out of 26 patients and improvement was noted in 22 patients. The improvement of hearing was statistically confirmed by applying the paired t test. There was a mean improvement of 12.714 dB between the pre and post treatment PTA. There were 14 patient with facial palsy of which 6 were immediate onset and 8 late onset facial palsy. Steroid treatment, physiotherapy were given for the patients with facial palsy and 2 patients underwent facial nerve decompression. 5 (35.7%) patients had transverse type of temporal bone fracture and 9 (64.28%) patients had longitudinal fracture. This finding is not concordance with other studies in which it revealed that half of CN VII palsy is found in transverse fracture and only a quarter in longitudinal fractures. In Yalciner et al’s study, there were 9 facial nerve paralysis cases, with 3 of them having early or immediate and 6 having late onset palsy [8]. All of the 6 paralysis cases with late onset were seen with petrous fractures and 2 of the 3 cases with early or immediate onset paralysis were seen with petrous fractures, while 1 had non-petrous, mixed type fracture. In the literature, facial nerve paralysis rates were reported as 10–25% for longitudinal fractures and 38–50% for transverse fractures [4, 11].

Conclusion

There are a large number of patients with temporal bone fractures as polytrauma cases are on the rise. Yet trauma to temporal bone is often overlooked in the initial evaluation. Different types of injuries can occur following temporal bone fractures. It can vary from trivial injuries to grave injures. Injuries like facial nerve palsy and SNHL should be identified at the earliest, so that the outcome following treatment is better. If not identified earlier patient they will have a poorer outcome which can affect the patient’s daily life. Different types of fractures can occur in temporal bone trauma which can be classified as longitudinal, transverse or oblique as per the older classification or as otic capsule sparing and otic capsule involving fractures based on the new classification. Steroid treatment has helped improvement of hearing in patients with SNHL and MHL and in patients with facial nerve palsy. In our study hearing improvement was noted in most patients with hearing loss when compared to the previous year, which may have been due to the detection of the injuries at the earliest and managing the same with appropriate treatment modalities.

Funding

Nil.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Vishnupriya Padmakumar, Email: vpriyapadmakumar@gmail.com.

E. Ramesh Kumar, Email: drerk@rediffmail.com

References

- 1.Zayas JO, Feliciano YZ, Hadley CR, Gomez AA, Vidal JA. Temporal bone trauma and the role of multidetector CT in the emergency department. Radiographics. 2011;31(6):1741–1755. doi: 10.1148/rg.316115506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannon CR, Jahrsdoerfer RA. Temporal bone fractures: review of 90 cases. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109(5):285–288. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1983.00800190007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee D, Honrado C, Har-El G, Goldsmith A. Pediatric temporal bone fractures. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(6):816–821. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199806000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson F, Semaan MT, Megerian CA. Temporal bone fracture: evaluation and management in the modern era. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41(3):597–618. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel A, Groppo E. Management of temporal bone trauma. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2010;3(2):105–113. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung MA, Flaherty A, Zhang JA, Hara J, Barber W, Burgess L. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss: primary care update. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2016;75(6):172–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Momose KJ, Davis KR, Rhea JT. Hearing loss in skull fractures. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1983;4(3):781–785. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yalçıner G, Kutluhan A, Bozdemir K, Cetin H, Tarlak B, Bilgen AS. Temporal bone fractures: evaluation of 77 patients and a management algorithm. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2012;18(5):424–428. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2012.98957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amin Z, Sayuti R, Kahairi A, Islah W, Ahmad R. Head injury with temporal bone fracture: one year review of case incidence, causes, clinical features and outcome. Med J Malaysia. 2008;63(5):373–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishman SL, Friedland DR. Temporal bone fractures: traditional classification and clinical relevance. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(10):1734–1741. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200410000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katzen JT, Jarrahy R, Eby JB, Mathiasen RA, Margulies DR, Shahinian HK. Craniofacial and skull base trauma. J Trauma. 2003;54(5):1026–1034. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000066180.14666.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]