Abstract

Improving quality of postoperative surgical care in head and neck surgery requires reporting of complications. Clavien–Dindo classification system can be used in grading complications related to head and neck surgery and to assess interobserver variability in grading complex complication scenarios. Data was collected from 242 patients who underwent Head and Neck Surgery from 2015 to 2018 at Dept. of ENT and Head and Neck Surgery at a tertiary care hospital. 177 patients had complications were graded based on Clavien–Dindo classification system, into a 5-scale classification system. Interobserver reliability scores for the complication grading scenarios were found to be statistically significant. Construct validity was confirmed as the length of stay in the hospital was statistically related to complication grade (P = 0.032) Reporting of complications is critical to quality improvement in surgical practice. The Clavien–Dindo complication grading scale system was found to be a useful tool for grading head and neck surgery complications.

Keywords: Clavien classification, Head and neck, Quality improvement, Surgical complications

Introduction

In Head and Neck surgery, complications can arise due to airway compromise, vascular injury, infections and rarely physiologic causes. The importance of reporting and grading surgical complications is central to quality improvement in head and neck surgery. A surgical complication is defined as “any deviation from the normal postoperative course [1].” Despite the accepted definitions of complications, problems arise with documentation of complications which includes variability of interpretation of complications between different surgeons, centres, and studies. Therefore reporting complications requires a standardized grading system.

A large number of patients presenting with head and neck cancer undergo surgical intervention. During the course of such surgery complications can arise which have the potential to be severe, and sometimes fatal. Due to the anatomic location of the vital organs of speech, swallowing, and respiration, the adverse effects of surgery for head and neck cancer are more common than similar treatments for cancers at other sites. It is essential that these potential complications are classified and graded by a robust classification system that helps to review and compare such complications in the head and neck surgeries between hospitals and centres.

A standardized method of grading surgical complications increases the accuracy of reporting, allows for more effective comparison between studies and centres, and allows early identification of areas of practice that can be improved [1]. Clavien et al. proposed a simple and effective system for grading surgical complications [1]. In 2004, Dindo et al. modified the original proposal into a more robust and standardized grading system [2]. Since its inception, the Clavien–Dindo classification system has been used to accurately grade surgical complications in numerous general surgical [3] procedures (Fig. 1).

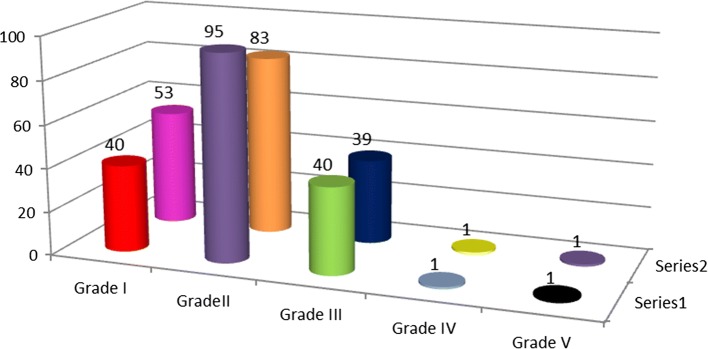

Fig. 1.

First and second observer grading of complications according to Clavien Dindo severity. Series 1 represents first observer grading, series 2 represents second observer grading of complications (n represents no. of complications)

The development of a new 5-scale classification system with the aim of presenting an objective, simple, reliable, and reproducible way of reporting negative events after surgery [2] (Table 1). Similar to the initial classification [1], this new system [2] was based on the type of therapy required to treat the complication. The rationale of this approach was to eliminate subjective interpretation of serious adverse events and any tendency to down-grade complications, because it is based on data that are usually well documented and easily verified. Finally, the classification offered the possibility to combine grades of complications to simplify its use depending on the patient cohort that was being analysed.

Table 1.

Clavien Dindo grading of surgical complications

| Grades | Definition |

|---|---|

| Classification of surgical complications | |

| Grade I |

Any deviation from the normal postoperative course without the need for pharmacological treatment or surgical, endoscopic and radiological interventions Acceptable therapeutic regimens are: drugs as antiemetics, antipyretics, analgesics, diuretics and electrolytes and physiotherapy This grade also includes wound infections at the bedside |

| Grade II |

Requiring pharmacological treatment with drugs other than such allowed for grade I complications Blood transfusions and total parenteral nutrition are also included |

| Grade III | Requiring surgical, endoscopic or radiological intervention |

| Grade III-a | Intervention not under general anaesthesia |

| Grade III-b | Intervention under general anaesthesia |

| Grade IV | Life-threatening complication (including CNS complications)* requiring IC/ICU-management |

| Grade IV-a | Single organ dysfunction (including dialysis) |

| Grade IV-b | Multi organ dysfunction |

| Grade V | Death of a patient |

| Suffix ‘d’ | If the patient suffers from a complication at the time of discharge, the suffix “d” (for ‘disability’) is added to the respective grade of complication. This label indicates the need for a follow-up to fully evaluate the complication |

IC intermediate care, ICU intensive care unit

*Brain haemorrhage, ischaemic stroke, subarachnoid bleeding, but excluding transient ischaemic attacks (TIA)

There is a need for a standardized and comprehensive scale for grading surgical complications in head and neck surgery procedures. Two recent studies adopted the Clavien–Dindo classification system for grading complications after major head and neck surgical procedures [4, 5]. However there is no Indian study which has used the Clavien–Dindo system to assess complications in Head and Neck surgery (Fig. 2).

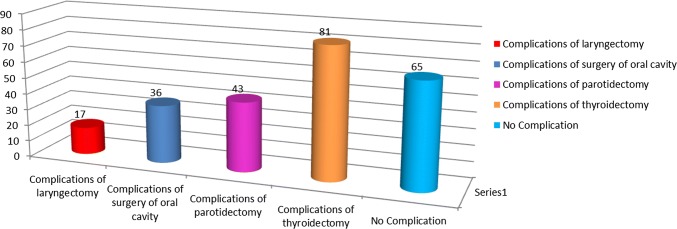

Fig. 2.

Various head and neck surgeries and their complications. Figure showing various head and neck surgeries and their complications (n represents no. of complications)

Aims and Objectives

The importance of reporting and grading surgical complications is central to quality improvement in head and neck surgery. The purpose of this study is to assess the validity of the Clavien–Dindo classification system for use in grading complications related to head and neck surgery.

Materials and Methods

Data collected from 242 patients who underwent Head and Neck Surgery retrospectively from 2014 to 2018 at Dept. of ENT and Head and Neck Surgery, Command Hospital Airforce Bengaluru. 177 patients had complications were graded based on Clavien–Dindo classification system, into a 5-scale classification system (Fig. 3).

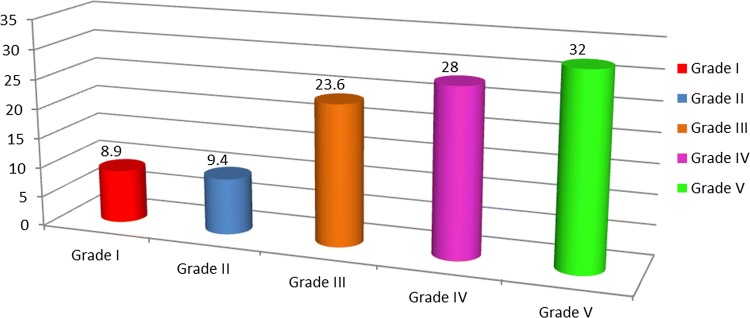

Fig. 3.

Mean length of stay plotted against Clavien–Dindo Severity. Figure showing mean length of hospital stay with grade of complication (n represents mean length of hospital stay)

The interobserver reliability of each complication scenario was calculated using an unweighted kappa statistic. Standard interpretation of kappa values were used; < 0.2 is slight, 0.2–0.4 is fair, 0.4–0.6 is moderate, 0.6–0.8 is substantial, and 0.8–1.0 is almost perfect. The association between complication grade and length of stay score was calculated using analysis of variance. Statistical significance was defined as P value < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (version 21; IBM, Armonk, NY).

Grade I complication mean length of stay is 8.9 days, grade II complication mean length of stay 9.4 days, grade III complication mean length of stay is 23.6 days, grade IV complication mean length of stay is 28 days and grade V complication mean length of stay is 32 days. There was a statistically significant trend between the grade of complication and the mean length of stay score (P = 0.032). Higher the grade of complication, longer was the length of hospital stay.

Discussion

There is a lack of consensus on how to define complications and to stratify them by severity [1, 6–9]. The absence of a definition and a widely accepted ranking system to classify surgical complications has hampered proper interpretation of surgical outcome data for a long time [10]. Terms, such as minor, moderate, major, or severe complications, have been inconsistently used among different authors and centres [1]. A number of attempts had been made in the 1990s to classify surgical complications [1, 6–9], but none of them have gained widespread acceptance. In 1992, a novel approach was presented to rank complications by severity based on the therapy used to treat the complications, and differentiated 3 types of negative outcome after surgery, (a) complication, (b) failure to cure, and (c) sequela [1]. The development of a universal complication grading by Clavien [1] has helped in accuracy and transparency in reporting complications. Some surgical specialties have adopted and used the proposed grading system [11] however there is a paucity of data from the head and neck literature. Two head and neck studies have used the Clavien–Dindo system to grade their complications. However, it has not been assessed whether it is a reliable and valid grading system for complications in this patient population [4, 5]. The current study assessed interobserver reliability and construct validity of use of Clavien–Dindo system to grade complications of head and neck surgeries.

A study conducted by Dindo et al. [2] showed that the new ranking system significantly correlated with complexity of surgery (P < 0.0001) as well as with the length of the hospital stay (P < 0.0001). A total of 144 surgeons from 10 different centers around the world and at different levels of training returned the survey. Ninety percent of the case presentations were correctly graded. The classification was considered to be simple, reproducible, logical, useful, and comprehensive.

A study done by McMahon et al. [5] over a period of 27 months studied 192 patients who had had major head and neck operations with free flaps. Data on complications were gathered prospectively along with patients’ details, factors indicative of the magnitude of the surgical insult, and variations in perioperative care. Complications were classified according to the Clavien–Dindo system. A total of 64% of patients had complications, and in around one-third they were serious; wound and pulmonary complications were the most common. The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications was found to be useful in this group.

Monteiro et al. [12] in their study of 371 patients who underwent Head and Neck surgery had a kappa value of 0.66 which was suggestive of moderate to high interobserver reliability. In this study interobserver reliability scores based on Clavien–Dindo grading scale ranged from moderate to high for most of the grading exercises, with scores dependent on the complication of the scenario. Scenarios with a perfect or near perfect interobserver reliability were those in which the outcome related to the complication were explicitly stated in the wording of the Clavien–Dindo system and not subject to interpretation, such as grade III complications (surgical procedure under general anaesthetic) and grade V complications (death).

In our study 177 cases had complications which were graded according to Clavien–Dindo complication grading by two independent observers. The present study showed kappa value of 0.875 which is almost perfect interobserver reliability and statistically significant. In our study Grade I complication mean length of stay is 8.9 days, grade II complication mean length of stay 9.4 days, grade III complication mean length of stay is 23.6 days, grade IV complication mean length of stay is 28 days and grade V complication mean length of stay is 32 days. As hypothesized, increased length of hospital stay was associated with increasing complication grade, except for grade V complications. Grade V complication is expected often occurs during the early postoperative period. This association has been demonstrated in other validation studies of the Clavien–Dindo grading scale [13–15]. The same was seen in our study also. In our study, we felt that the Clavien–Dindo grading scale was applicable to head and neck surgery and that a standardized system for grading complications would be useful for clinical practice, as well as for reporting complications in research studies.

There have been concerns of the grading system in various studies. One of the major themes expressed was issues with the definition of a “surgical procedure” for grade III complications. There was concern about the ambiguity of what constituted a “surgical procedure.” The grading scale also lacks a definition of what constitutes a “surgical procedure” at bedside [12]. One limitation is its ability to effectively grade wound complications, which is a major component of head and neck surgery complications and for which there is a wide range of severity and potential consequences. For example, wound infections opened at bedside would be recorded as a grade I or II complication, as would a salivary fistula post-laryngectomy managed with wound opening and packing. Both would be assigned a similar grade, but they have significant differences in terms of resources used, length of hospital admission, and potential for catastrophic complications. Another limitation is how one interprets the severity of surgical complications that require a return to the operating room. For example, drainage of a neck hematoma would be assigned the same grade as a flap failure that requires a return to the operating room for a second flap, whereas there are significant differences in the severity of the complication. In addition to wound complications, there was concern that the grading system did not capture unique problems facing the head and neck patient population, such as persistent oral dysphagia following oral cavity and/or oropharyngeal resection. The grading scale also lacks a definition of what constitutes a “surgical procedure” at bedside [12]. There is also the lack of ability to grade injury to major motor or sensory nerves of the head and neck (for example brachial plexus injury, or bilateral vocal cord paralysis) or grade direct injury to sensory organs resulting in blindness or deafness.

In our study, we also found that there was also a notable difference in grading of the scenario of post-thyroidectomy hypocalcaemia requiring intravenous infusion, which highlights a deficiency of this grading scale for use in head and neck surgery. Respondents grading this complication were almost evenly distributed between grades I and II. Electrolyte replacement is included in the Clavien–Dindo definition of a grade I complication, but the route of administration is not. If any electrolyte replacement protocol is assigned grade I, as suggested by Clavien–Dindo, then hypocalcaemia treated orally or intravenously would be graded the same despite there being a potential difference in severity of the hypocalcaemia following thyroidectomy.

In our study we felt that it was more appropriate to have a grading system that distinguishes between surgical and medical complications. From a surgical quality improvement perspective, it may be more beneficial to a surgical department to know which complications are related to surgical intervention and which complications arise are associated with the comorbid health status of the head and neck population.

Other surgical grading systems exist in the literature. Some of these are generic classification systems intended to capture all complications; and some have modified the Clavien–Dindo system for specific surgical procedures [14, 16]. The Memorial Sloan Kettering severity grading system is one such modification developed by Martin et al. [17] which is very similar to the original Clavien grading system but differs in details such as scoring.

The Accordion classification [18] is named for its ability to expand and contract to encompass the full range of complications in the literature. In the contracted state, the classification has only four levels, which are headed by self-evident terms rather than grades: mild, moderate, severe, and death [17]. The expanded Accordion classification is used in severe complications, with greater detail on organ failure.

Of current grading systems, we felt that the Clavien–Dindo is an appropriate choice based on its widespread use and dissemination in the literature and among many surgical specialties—as well as its demonstration of construct validity in head and neck surgery.

Conclusion

The accurate and comprehensive collection and recording of surgical complications has wide reaching benefits to describe standardized patient outcomes in clinical research, to identify areas for quality improvement in patient care, and for education. The Clavien–Dindo system has a high level of validity, reliability, and acceptance, however development of a grading system that is specific to head and neck surgery would be a significant improvement to describe the severity and encompass the breadth of postoperative adverse events.

Acknowledgements

We thank the support of Mrs Sowgandhi Statistician, Institute of Aerospace Medicine Bangalore for her help in the statistical research.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards

Permission taken from institutional ethical committee for doing this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Clavien PA, Sanabria JR, Strasberg SM. Proposed classification of complications of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1992;111:518–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P-A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–196. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perisanidis C, Herberger B, Papadogeorgakis N, et al. Complications after free flap surgery: do we need a standardized classification of surgical complications? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMahon JD, Maciver C, Smith M, et al. Postoperative complications after major head and neck surgery with free flap repair-prevalence, patterns, and determinants: a prospective cohort study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:689–695. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pomposelli J, Gupta S, Zacharoulis D, et al. Surgical complication outcome (SCOUT) score: a new method to evaluate quality of care in vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25:1007–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(97)70124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gawande A, Thomas E, Zinner M, Brennan T. The incidence and nature of surgical adverse events in Colorado and Utah in 1992. Surgery. 1999;126:66–75. doi: 10.1067/msy.1999.98664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veen M, Lardenoye J, Kastelein G, et al. Recording and classification of complications in a surgical practice. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:421–424. doi: 10.1080/110241599750006622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pillai S, van Rij A, Williams S, et al. Complexity- and risk-adjusted model for measuring surgical outcome. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1567–1572. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horton R. Surgical research or comic opera: questions, but few answers. Lancet. 1996;347:984–985. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donat SM. Standards for surgical complication reporting in urologic oncology: time for a change. Urology. 2007;69:221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monteiro, et al. Assessment of the Clavien–Dindo classification system for complications in head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(12):2726–2731. doi: 10.1002/lary.24817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivanovic J, Al-Hussaini A, Al-Shehab D, et al. Evaluating the reliability and reproducibility of the Ottawa thoracic morbidity and mortality classification system. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casadei R, Ricci C, Pezzilli R, et al. Assessment of complications according to the Clavien–Dindo classification after distal pancreatectomy. JOP. 2011;12:126–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de la Rosette JJMCH, Opondo D, Daels FPJ, et al. Categorisation of complications and validation of the Clavien score for percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Eur Urol. 2012;62:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sink EL, Leunig M, Zaltz I, Gilbert JC, Clohisy J. Reliability of a complication classification system for orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2220–2226. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2343-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin RC, 2nd, Brennan MF, Jaques DP. Quality of complication reporting in the surgical literature. Ann Surg. 2002;235:803–813. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. The accordion severity grading system of surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2009;250:177–186. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181afde41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]