Abstract

Background

Variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is common in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). However, poor access to endoscopy services precludes the diagnosis of varices.

Objectives

We determined the diagnostic accuracy of routine clinical findings for detection of esophageal varices among patients with UGIB in rural SSA where schistosomiasis is endemic.

Methods

We studied patients with a history of UGIB. The index tests included routine clinical findings and the reference test was diagnostic endoscopy. Multivariable regression with post-estimation provided measures of association and diagnostic accuracy.

Results

We studied 107 participants with UGIB and 21% had active bleeding. One hundred and three (96%) had liver disease and 86(80%) varices. Factors associated with varices (p-value <0.05) were ≥ 4 lifetime episodes of UGIB, prior blood transfusion, splenomegaly, liver fibrosis, thrombocytopenia, platelet count spleen diameter ratio <909, and a dilated portal vein. Two models showed an overall diagnostic accuracy of > 90% in detection of varices with a number needed to misdiagnose of 13(number of patients who needed to be tested in order for one to be misdiagnosed by the test).

Conclusion

Where access to endoscopy is limited, routine clinical findings could improve the diagnosis of patients with UGIB in Africa.

The diagnostic accuracy of routine clinical findings for detection of esophageal varices in rural sub-Saharan Africa where schistosomiasis is endemic.

Introduction

Endoscopy is recommended for anyone with a history of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (vomiting blood or passing black stool or rarely, passing frank blood in one's stool). It is the most accurate and best available diagnostic test for upper gastrointestinal bleeding1,2. On the other hand, limited access to endoscopy is associated with poor disease outcomes3,4. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a frequent cause of hospitalization and death5–8. It is mainly due to bleeding esophageal varices and is a complication of chronic schistosomiasis and/or liver cirrhosis. Diagnosis of varices and UGIB in SSA is challenging because of limited access to endoscopy9,10. This has had undesirable effects like increased frequency of death7,11,12. Just a few studies have identified potential surrogates to endoscopy for diagnosis of UGIB or varices. These include thrombocytopenia, splenomegaly, an abnormal platelet count/spleen diameter ratio, and ultrasound periportal fibrosis patterns13–16. However, none of these parameters have been studied at any primary health care settings in rural SSA were endoscopy services are absent. We studied the diagnostic accuracy of routine clinical findings for detection of esophageal varices among patients reporting one or more lifetime episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Our study was conducted at a primary health facility in rural sub-Saharan Africa where schistosomiasis is endemic and access to endoscopy is limited.

Materials and methods

Overview

Our study was part of one study that profiled upper gastrointestinal bleeding17. It was a diagnostic accuracy study at Pakwach Health Centre IV in Northwestern Uganda. We enrolled participant's ≥12 years of age, with a history of UGIB and/or admitted for acute severe UGIB. For each participant, we obtained consent and administered a questionnaire collecting information on current or past history of UGIB. We then performed a physical examination, laboratory tests, and liver sonography. The above were performed independently of the endoscopy team.

Diagnostic endoscopy

All participants were eligible for a diagnostic endoscopy and underwent diagnostic upper digestive endoscopy. No participant was excluded for any reason. Endoscopy was performed in the unit's operating theatre by a trained gastroenterologist and his team using a Pentax EPKi digital video processor and Pentax 9.8mm video gastroscope18. The esophagus, stomach, and duodenum were examined for evidence of UGIB or cause of UGIB with emphasis on varices, esophageal or gastric/duodenal erosions or ulcers18. Endoscopic findings were reported as recommended by the Japanese research for Portal Hypertension, and/or the modified Forrest classification for upper gastrointestinal bleeding19,20. The report was written and pictures saved. Results were communicated to each participant; appropriate treatment given (propanolol for varices or triple therapy for peptic ulcer disease or hematinics for anemia), and linkage to care ensured.

Ethical approval was obtained from the School of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee of Makerere University College of Health Sciences, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. Our study was carried out in accordance with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data management and analysis

The reference standard test was endoscopy. The dependent variable was esophageal varices and independent variables were routine clinical findings. Data was recorded in forms and transcribed into Microsoft Access database software 2007 (Microsoft Corporation) daily and exported to Stata version 13 (StataCorp, Lakeway, College Station, Texas, USA) for analysis. Descriptive statistics included frequencies and proportions. Inferential statistics involved logistic regression with esophageal varices as the dependent variable. A significance level (p-value < 0.05) was chosen. Odds ratios and confidence intervals were used for inference. Purposeful selection of covariates was performed and models generated. The best-fit model was selected on clinical plausibility, Akaike information criterion, and Bayesian information criterion. The outputs of the 2 best-fit models were represented graphically as nomograms. Post-estimation in Stata generated measures of diagnostic accuracy by a confusion matrix for the best two models and other clinical parameters associated with esophageal varices. Measures of diagnostic accuracy included specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, correct classification rate (overall accuracy), and number needed to misdiagnose-number of patients who needed to be tested in order for one to be misdiagnosed by the test21–24. These results are detailed in the subsequent text and tables.

Results

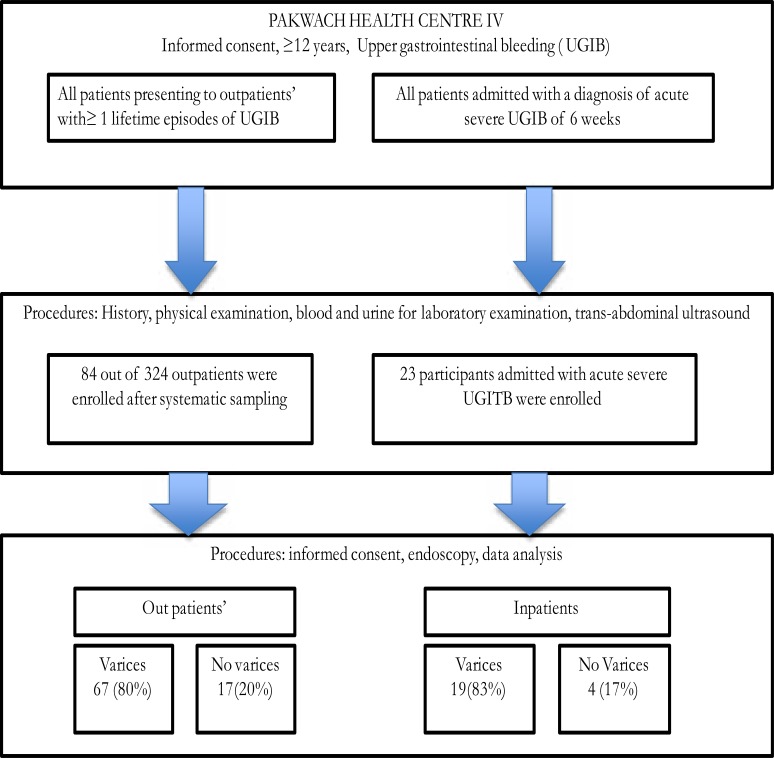

From July to August 2014, one hundred and seven participants underwent endoscopy to determine the possible cause of their UGIB. Eighty-four (78%) were outpatients and 23 (22%) in-patients with severe acute UGIB (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart describing enrollment and the proportion of participants from outpatients and inpatients with esophageal varices.

The youngest and oldest participants were 25 years and 75 years of age respectively. The median age was 45 years and IQR 13 years. Sixty-four (60%) were females, all participants reported ≥2 contacts with the waters of the Nile every week, 94(88%) reported prior treatment with praziquantel, 103 (96%) reported a past admission for UGIB, and none of the study participants had ever had an endoscopy. Among the 107 participants, 57% (95% CI 47%–66%) experienced two or more episodes of UGIB during their lifetime. At ultrasonography 92% had liver disease with 40% having cirrhosis and 60% had periportal fibrosis. We found esophageal varices in 80% (95% CI, 72%-87%), gastric varices in 17% (95% CI, 11–25%), portal hypertensive gastropathy 78% (95% CI, 69%-84%), and actively bleeding or oozing gastric or duodenal mucosa in 10% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Endoscopy findings, their proportions, and/or 95% confidence intervals for proportions

| Endoscopy findings | N (%) | 95% CI (%) |

| Esophageal varices present | 86(80%) | (72%–87%) |

| Grades of varices | ||

| F0: lesions assuming no varicose appearance | 21 (19.6%) | |

| F1: straight small-calibered varices | 12 (11.1%) | |

| F2: moderately enlarged, beady varices | 32 (29.9%) | |

| F3: markedly enlarged, nodular, or tumor-shaped varices | 42 (39.4%) | |

| Red color sign (RC) with esophageal varices | ||

| Red wale marking, cherry Red Spot, hematocytic spot | ||

| RC0: absent | 11 (12.8%) | |

| RC1: small in number and localized | 10 (11.6%) | |

| RC2: intermediate between 1 and 3 | 27 (31.3%) | |

| RC3: large in number and circumferential | 38 (44.2%) | |

| Esophageal varices with | ||

| Gushing | 0 | |

| Spurting | 2 (2%) | |

| Red plug | 13 (12%) | |

| White plug | 8 (8%) | |

| Gastric varices present | 18(17%) | (11%–25%) |

| Portal hypertensive gastropathy (mosaic pattern) | 83 (78%) | (69%–84%) |

| Abnormal mucosa stomach or duodenal mucosa (erosions or ulcerations) and presence of stigmata of bleeding |

||

| Forrest classification | ||

| I a (spurting hemorrhage) | 0 | |

| Ib (oozing hemorrhage) | 11 (10%) | |

| IIa&b (non bleeding visible vessel or adherent clot) | 0 | |

| II c (flat pigmented hematin) | 1 (1%) | |

| III (lesions without any signs of recent hemorrhage or fibrin) | 17 (16%) | |

A number of routine clinical findings were more frequent and more likely to occur among those with varices than those without varices (95% CI for odds ratio >1) at univariable analysis. These included having ≥ 4 lifetime episodes of UGIB, prior history of blood transfusion, palpable spleen, WHO ultrasound periportal fibrosis patterns DEF or X, platelet count ≤140 x109/L, platelet count /spleen diameter ratio ≤909, portal vein diameter ≥13 mm (Table 2).

Table 2.

Routine clinical findings associated with the presence of esophageal varices at endoscopy: proportions, crude odds ratios, and their 95% confidence intervals

| Factor variables | Varices | No varices | Crude odds ratios (95%CI) |

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age ≤39 years | 25 (29) | 4 (19) | 1.7 (0.5–6) |

| Female gender | 53 (62) | 11 (52) | 1.5 (0.6–3.8) |

| Born in Pakwach | 67 (78) | 15 (71) | 1.4 (0.5–4.1) |

| Resident in Pakwach> 10 years | 77 (90) | 17 (81) | 2.0 (0.6–7.3) |

| >2 contacts a week with the waters of the Nile | 86 (100) | 21 (100) | - |

| Farmer (occupation) | 63 (73) | 16 (76) | 0.9 (0.3–2.6) |

| Prior Praziquantel use | 75 (87) | 18 (85) | 1.1 (0.3–4.5) |

| Previously admitted for upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 84 (98) | 19 (90) | 4.4 (0.6–33.4) |

| Currently admitted for severe acute variceal bleeding | 19 (22) | 4 (19) | 1.2 (0.4–4) |

| Number lifetime of episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding | |||

| 1 | 33 (39) | 13 (62) | |

| 2–3 | 27 (31) | 7 (33) | 2.4 (1.2–4.9)* |

| 4 and more | 26 (30) | 1 (5) | |

| Previous blood transfusion | 64 (72) | 9 (43) | 3.9 (1.4–10.5)* |

| Alcohol use | 4 (5) | 0 | - |

| Jaundice | 10 (11) | 1 (5) | 2.6 (0.3–21.8) |

| Ascites | 17 (20) | 1 (5) | 4.9 (0.6–39.3) |

| Liver flap | 8 (9) | 2 (10) | 0.9 (0.2–4.9) |

| Edema | 11 (13) | 1 (5) | |

| #Splenomegaly at palpation | 78 (96) | 14 (67) | 13 (3–56) * |

| WHO ultrasound patterns | |||

| A+C | 1 (1) | 8 (38) | 4.8 (1.9–12.3)* |

| D+E+F | 51 (59) | 8 (38) | |

| X | 34 (40) | 5 (24) | |

| Platelet count spleen diameter ratio .909 | 79 (92) | 6 (29) | 28 (8–96)* |

| Portal vein diameter ≤13 mm | 69 (80) | 10 (48) | 4.5 (1.6–12.2)* |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen positive | 5 (6) | 2 (9) | 0.54 (0.1–3.25) |

| Hepatitis C-antibody positive | 21 (24) | 7 (33) | 0.65 (0.23–1.81) |

| Urine circulating cathodic antigen positive | 5 (6) | 4 (19) | 0.26 (0.06–1.07) |

| Platelet count ≤ 140 x109/L | 82 (95) | 12 (43) | 27 (7.3–103)* |

| Hemoglobin level ≤80g/L | 26 (30) | 6 (29) | 1.1 (0.4–3.1) |

P-value <0.05; 95% confidence intervals do not cross 1

#5 missing evaluations due to tense ascites.

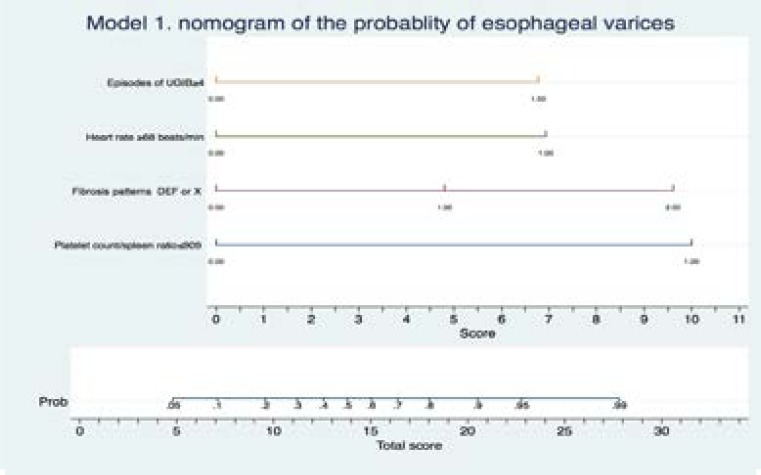

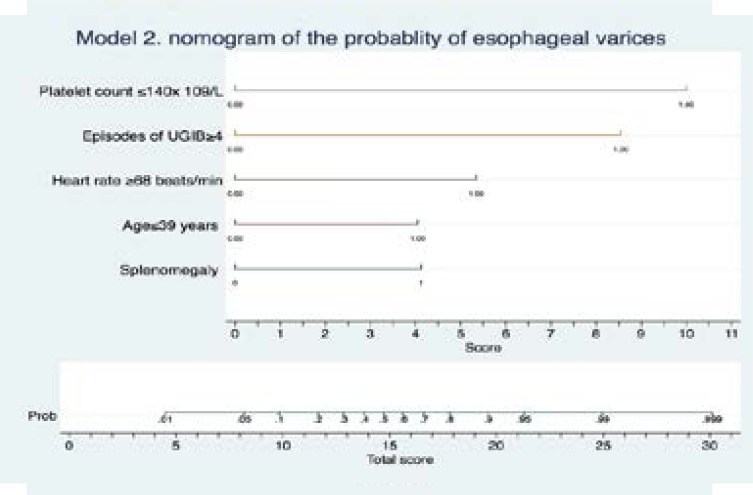

At multivariable logistic regression we identified two of the best-fit models 1 and 2. These are summarized visually as two nomograms, Figure 2 and Figure 3. These represent an approximate graphical computation of a mathematical function of each model. The sums of the scores of all factors in the graphs indicate the predicted probability of having varices. This is obtained by linking the total scores with the corresponding probability. The diagnostic accuracy of these clinical factors and statistical models are summarized in Table 3. All factors were found to have very good sensitivity (>90%) while model 1 and 2 had the best specificity. Model 1 and 2 had the best number needed to misdiagnose esophageal varices of 13.

Figure 2.

A nomogram of model 1 consisting of platelet count spleen diameter ratio ≤909, WHO peri-portal fibrosis patterns EF or X, number lifetime of episodes of UGIB≥4, heart rate ≥68beats/minute. This enables one to calculate output probabilities for predictive models with a visual approach. Estimate the probability of having varices through 3 steps. Step 1 -establish scores for all variable values, step 2-obtain the total score adding up all the scores obtained in the previous step, step 3-obtain the probability of the event (total Score -> Probability of event).

Figure 3.

A nomogram of model 2 consisting of includes age ≤39 years, heart rate ≥68 beats/minute, palpable spleen, ≥4 Number lifetime of episodes of UGIB, platelet count< 140x109/L This enables one to calculate output probabilities for predictive models with a visual approach. Estimate the probability of having varices through 3 steps. Step 1 -establish scores for all variable values, step 2-obtain the total score adding up all the scores obtained in the previous step, step 3-obtain the probability of the event (total Score -> Probability of event).

Table 3.

The diagnostic accuracy of routine clinical findings or their combinations for detection of esophageal varices in rural Africa where schistosomiasis is endemic: diagnostic tests, study size, and measures of diagnostic accuracy

| Diagnostic tests | N | Sensitivity (95%CI) |

Specificity (95%CI) |

PPV (95%CI) |

NPV (95%CI) |

Accuracy (95%CI) |

NNM (95%CI) |

| Model 1 (involves ultrasonography) | 107 | 97% (90–99%) |

71% (48–89%) |

93% (88–97%) |

83% (61–94%) |

92% (85–96%) |

13 (7–25) |

| Model 2 (no ultrasonography) | 102 | 96% (90–99%) |

76% (53–92%) |

94% (89–97%) |

84% (63–94%) |

92% (85–97%) |

13 (7–25) |

| Platelet count spleen diameter ratio <909 | 107 | 92% (84–97%) |

71% (48–89%) |

93% (87–96%) |

68% (50–82%) |

88% (80–93%) |

8 (5–14) |

| ≥4 Number lifetime of episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) | 107 | 100% (96–100%) |

0 (0–16%) |

83% - | - | 80% (72–87%) |

5 (4–8) |

| Fibrosis patterns EF or X* | 107 | 99% (94–100%) |

38% (18–62%) |

87% (82–90%) |

89% (51–98%) |

87% (79–93%) |

8 (5–14) |

| Palpable spleen | 102 | 96% (90–99%) |

33% (15–57%) |

85% (80–88%) |

70% 40-89% | 83% (79–90%) |

6 (5–10) |

| Platelet count ≤140 x109/L | 107 | 95% (89–99%) |

57% (34–79%) |

90% (85–94%) |

75% (56–89%) |

88% (80–93%) |

8 (5–14) |

| Heart rate ≥68beats/min | 107 | 100% (96–100%) |

0 (0–16%) |

80% - | - | 80% (72–87%) |

5 (4–8) |

| Age ≤39 years | 107 | 100% (96–100%) |

0 (0–16%) |

80% - | - | 80% (72–87%) |

5 (4–8) |

Model 1 includes following factor variables platelet count spleen diameter ratio <909, WHO periportal fibrosis patterns EF or X, number lifetime of episodes of UGIB≥4, heart rate ≥68beats/minute.

Model 2 includes age ≤39 years, heart rate ≥68 beats/minute, palpable spleen, ≥4 Number lifetime of episodes of UGIB, platelet count≤140 x 109 /L.

PPV-positive predictive value, NPV-negative predictive value, NNM . number needed to misdiagnose.

Discussion

These results showed our two models of different routine clinical findings demonstrated good diagnostic accuracy in detecting esophageal varices. To our knowledge, this is the first study from a primary health facility in rural SSA that has studied detection of varices using clinical findings. We chose participants with UGIB because UGIB is a well-defined indication for endoscopy4,20. Most participants had recurrent UGIB (≥2 episodes of UGIB). Recurrent UGIB is with associated varices, further re-bleeding, and greatest risk of death25. Like most studies from SSA, we found esophageal varices were the most common endoscopic finding in UGIB6–8,26. This contrasts with other parts of the world where peptic ulcer disease is the most frequent endoscopic finding27,28. As other researchers, we identified clinical findings that were associated with varices7,29–32. However, our models 1 and 2 have not been described elsewhere. These two models showed the highest accuracy and best diagnostic test effectiveness than any other routine clinical finding. Model 1 is distinct in that requires ultrasonography unlike model 2 that involves only a medical history, a physical examination, and platelet count. A manual platelet count is possible in every rural health facility laboratory33. Abdominal ultrasonography has the advantage of simplifying diagnosis of periportal fibrosis, to a lesser extent liver cirrhosis, and other hepatobiliary diseases such as hepatocellular cancer, gallstones, portal vein thrombosis, and others34,35. Our nomograms have potential advantages for rural health facilities. They permit straightforward estimation of each individual patient's test probability, are simple to understand, can be mass-produced at low cost, and can be easily alidated23. We acknowledge that these models cannot replace endoscopy as the diagnostic test of choice for detection of varices. However, nomograms have the potential to strengthen clinical decision making in settings were endoscopy is poorly accessible. Specifically, these nomograms could assist in prioritizing referral of patients for endoscopy; justifying the use of emergency medications like terlipressin in acute variceal bleeding and/or chronic use of propranolol to prevent recurrent variceal bleeding while awaiting endoscopy31,36,37. Using emergency drugs as terlipressin or ocreotide controls acute variceal hemorrhage is effective in up to 90% of individuals with bleeding varices38. While chronic treatment with propranolol decreases the risk of re-bleeding from 80% to 20% over one year among patients with Schistosomiasis31.

Study limitations

Our study has limitations. It was a single center study in a distinct rural community. This limits its generalizability. We also concede that having a larger study sample size would decrease the uncertainty of some of our findings.

Conclusion

Nomograms consisting of routine clinical findings effectively detect varices in adults with UGIB, schistosomiasis and/or cirrhosis. These nomograms are potential diagnostic triage tests for detection of varices in areas where schistosomiasis is endemic and access to endoscopy is limited.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded through an educational research grant from the Programmatic Award: Medical Education for Services to All Ugandans. http://www.fic.nih.gov/Grants/Search/Pages/MEPI-R24TW008886.aspx

KReLL family for providing the endoscope tower.

Staff and patients at Pakwach health center IV.

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare they have no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Dolmans WM, Mbaga IM, Mwakyusa DH. Diagnostic yield of endoscopy in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Trop Geogr Med. 1983 Jun;35(2):173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garg SK, Anugwom C, Campbell J, Wadhwa V, Gupta N, Lopez R, et al. Early esophagogastroduodenoscopy is associated with better Outcomes in upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a nationwide study. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5(05):E376–E386. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-121665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen P-H, Chen W-C, Hou M-C, Liu T-T, Chang C-J, Liao W-C, et al. Delayed endoscopy increases re-bleeding and mortality in patients with hematemesis and active esophageal variceal bleeding: a cohort study. J Hepatol. 2012;57(6):1207–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dworzynski K, Pollit V, Kelsey A, Higgins B, Palmer K. Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ Br Med J Online. 2012;344 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Cock KM, Awadh S, Raja RS, Wankya BM, Lucas SB. Esophageal varices in Nairobi, Kenya: a study of 68 cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31(3):579–588. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alema ON, Martin DO, Okello TR. Endoscopic findings in upper gastrointestinal bleeding patients at Lacor hospital, northern Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2012;12(4):518–521. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v12i4.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chofle AA, Jaka H, Koy M, Smart LR, Kabangila R, Ewings FM, et al. Oesophageal varices, schistosomiasis, and mortality among patients admitted with haematemesis in Mwanza, Tanzania: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014 Jun 3;14:303. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulima G, Qureshi JS, Shores C, Tamimi S, Klackenberg H, Andrén-Sandberg Å. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding at a Public Referal Hospital in Malawi. Surg Sci. 2014;5(11):501. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuks NS. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2011. Challenges of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in Resource-Poor Countries. In Tech. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheil-Adlung X. Global evidence on inequities in rural health protection. New data on rural deficits in health coverage for 174 countries. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kheir MM, Eltoum IA, Saad AM, Ali MM, Baraka OZ, Homeida MM. Mortality due to schistosomiasis mansoni: a field study in Sudan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999 Feb;60(2):307–310. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moledina SM, Komba E. Risk factors for mortality among patients admitted with upper gastrointestinal bleeding at a tertiary hospital: a prospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17(1):165. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0712-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Araújo Souza MR, De Toledo CF, Borges DR. Thrombocytemia as a predictor of portal hypertension in schistosomiasis. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45(10):1964–1970. doi: 10.1023/a:1005535808464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harries AD, Wirima JJ. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Malawian adults and value of splenomegaly in predicting source of haemorrhage. East Afr Med J. 1989;66(2):97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agha A, Abdulhadi MM, Marenco S, Bella A, AlSaudi D, El-Haddad A, et al. Use of the platelet count/spleen diameter ratio for the noninvasive diagnosis of esophageal varices in patients with schistosomiasis. Saudi J Gastroenterol Off J Saudi Gastroenterol Assoc. 2011;17(5):307. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.84483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu X-D, Xu C-F, Dai J-J, Qian J-Q, Pin X. Ratio of platelet count/spleen diameter predicted the presence of esophageal varices in patients with schistosomiasis liver cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(5):588–591. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Opio CK, Kazibwe F, Ocama P, Rejani L, Belousova EN, Ajal P. Profiling lifetime episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding among patients from rural Sub-Saharan Africa where schistosoma mansoni is endemic. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24 doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.296.9755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S-H, Park Y-K, Cho S-M, Kang J-K, Lee D-J. Technical skills and training of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for new beginners. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2015;21(3):759. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i3.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tajiri T, Yoshida H, Obara K, Onji M, Kage M, Kitano S, et al. General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices (2nd edition) Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc. 2010 Jan;22(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forrest JH, Finlayson NDC, Shearman DJC. Endoscopy in Gastrointestinal bleeding. The Lancet. 1974 Aug 17;304(7877):394–397. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91770-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng C-YJ, So T-SH. Logistic regression analysis and reporting: A primer. Underst Stat Stat Issues Psychol Educ Soc Sci. 2002;1(1):31–70. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Habibzadeh F. Statistical data editing in scientific articles. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32(7):1072–1076. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.7.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chun FK-H, Karakiewicz PI, Briganti A, Walz J, Kattan MW, Huland H, et al. A critical appraisal of logistic regression-based nomograms, artificial neural networks, classification and regression-tree models, look-up tables and risk-group stratification models for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007 Apr 1;99(4):794–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Habibzadeh F, Yadollahie M. Number needed to misdiagnose: a measure of diagnostic test effectiveness. Epidemiology. 2013;24(1):170. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31827825f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Opio CK, Garcia-Tsao G. Managing varices: drugs, bands, and shunts. Gastroenterol Clin. 2011;40(3):561–579. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravera M, Reggiori A, Cocozza E, Ciantia F, Riccioni G. Clinical and endoscopic aspects of hepatosplenic schistosomiasis in Uganda. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8(7):693–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EAJ, Geraedts AAM, Tijssen JGP, Reitsma JB, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change?: Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(7):1494–1499. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malu AO, Wali SS, Kazmi R, Macauley D, Fakunle YM. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in Zaria, northern Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 1990;9(4):279–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdel-Wahab MF, Esmat G, Farrag A, El-Boraey Y, Strickland GT. Ultrasonographic prediction of esophageal varices in Schistosomiasis mansoni. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richter J, Correia Dacal AR, Vergetti Siqueira JG, Poggensee G, Mannsmann U, Deelder A, et al. Sonographic prediction of variceal bleeding in patients with liver fibrosis due to Schistosoma mansoni. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3(9):728–735. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiire CF. Controlled trial of propranolol to prevent recurrent variceal bleeding in patients with non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis. BMJ. 1989;298(6684):1363–1365. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6684.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ibrahim SZ, Shah T, Arbab BM, Abdel-Wahab O. Risk factors for bleeding in patients with asymptomatic oesophageal varices secondary to schistosomal portal hypertension: a longitudinal hospital based study. Sudan Med J. 2009;45(1) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Briggs C, Harrison P, Machin SJ. Continuing developments with the automated platelet count. Int J Lab Hematol. 2007;29(2):77–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2007.00909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El Scheich T, Holtfreter MC, Ekamp H, Singh DD, Mota R, Hatz C, et al. The WHO ultrasonography protocol for assessing hepatic morbidity due to Schistosoma mansoni. Acceptance and evolution over 12 years. Parasitol Res. 2014;113(11):3915–3925. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bélard S, Tamarozzi F, Bustinduy AL, Wallrauch C, Grobusch MP, Kuhn W, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound assessment of tropical infectious diseases—a review of applications and perspectives. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94(1):8–21. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang C, Han J, Xiao L, Jin C, Li D, Yang Z. Efficacy of vasopressin/terlipressin and somatostatin/octreotide for the prevention of early variceal rebleeding after the initial control of bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol Int. 2015;9(1):120–129. doi: 10.1007/s12072-014-9594-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tourabi HE, Amin AE, Shaheen M, Woda SA, Homeida M, Harron DWG. Propranolol reduces mortality in patients with portal hypertension secondary to schistosomiasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;88(5):493–500. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1994.11812896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seo YS, Park SY, Kim MY, Kim JH, Park JY, Yim HJ, et al. Lack of difference among terlipressin, somatostatin, and octreotide in the control of acute gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 2014;60(3):954–963. doi: 10.1002/hep.27006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]