Abstract

Sexual differences have been observed in the onset and prognosis of human cardiovascular diseases, but the underlying mechanisms are not clear. Here, we found that zebrafish heart regeneration is faster in females, can be accelerated by estrogen and is suppressed by the estrogen-antagonist tamoxifen. Injuries to the zebrafish heart, but not other tissues, increased plasma estrogen levels and the expression of estrogen receptors, especially esr2a. The resulting endocrine disruption induces the expression of the female-specific protein vitellogenin in male zebrafish. Transcriptomic analyses suggested heart injuries triggered pronounced immune and inflammatory responses in females. These responses, previously shown to elicit heart regeneration, could be enhanced by estrogen treatment in males and reduced by tamoxifen in females. Furthermore, a prior exposure to estrogen preconditioned the zebrafish heart for an accelerated regeneration. Altogether, this study reveals that heart regeneration is modulated by an estrogen-inducible inflammatory response to cardiac injury. These findings elucidate a previously unknown layer of control in zebrafish heart regeneration and provide a new model system for the study of sexual differences in human cardiac repair.

Keywords: sexually dimorphic, heart regeneration, estrogen, estrogen receptor, inflammation

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the primary cause of death worldwide: killing 17.9 million people in 2015, more than 30% of the global mortality (Roth et al. 2017). Gender differences have been reported in the clinical manifestation and recovery of CVD (Ostadal & Ostadal 2014, EUGenMed et al. 2015). In various mammalian models of cardiac defects, females consistently demonstrate a lower mortality, less severe disease phenotype and better functional recovery than their male counterparts (Czubryt et al. 2006). An understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying these gender differences will provide an important gateway toward better CVD prevention and treatment. Gene expression profiles of mammalian cardiomyocytes are sexually dimorphic (Isensee et al. 2008, Tsuji et al. 2017), and estrogen receptor expression is deregulated in some cardiomyopathies (Mahmoodzadeh et al. 2006). Despite the apparent involvement of estrogen in CVD, clinical translation of these findings has been lagging, partly due to inconclusive results from large-scale studies on the benefits of post-menopausal hormone replacement in CVD prevention (Low et al. 2002). This is attributed, at least in part, to the lack of a mechanistic understanding of the role of estrogen in cardiomyocyte biology, which prevents optimal study design and subject selection in clinical studies (Whayne Jr & Mukherjee 2015).

While adult human cardiomyocytes are virtually unable to re-enter the cell cycle, other vertebrates, including zebrafish, newts and axolotls, demonstrate a remarkable ability to regenerate their hearts (Garcia-Gonzalez & Morrison 2014, Vivien et al. 2016). Among these organisms, zebrafish have emerged as one of the most well-established model organisms for the study of heart regeneration. Unlike adult mammals, where myocardial lesions are filled with collagen-rich scars that impair cardiac functions (Hsieh et al. 2007, Senyo et al. 2013), the scar in zebrafish can be replaced by newly formed cardiomyocytes within 6 months, through extensive cardiomyocytes proliferation, as indicated by the expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) or phospho-histone H3 (Poss et al. 2002, Chablais et al. 2011, González-Rosa et al. 2011). Additionally, fate mapping experiments have established that proliferating cardiomyocytes originate from mature cardiomyocytes (Jopling et al. 2010, Zhang et al. 2013). In this regard, the rapid disappearance of the sarcomeric structures and re-expression of embryonic genes, such as embryonic cardiac myosin heavy chain gene (embCMHC), suggest that regeneration largely involves the expansion of dedifferentiated cardiomyocytes (Sallin et al. 2015). Interestingly, a recent study has attributed the remarkable regenerative capacity of the zebrafish heart to this organism’s enhanced inflammatory and immune response (Lai et al. 2017).

The conservation of genetic pathways between zebrafish and mammals (Howe et al. 2013), and the technical and genetic resources offered by the zebrafish research community, make this organism an ideal model for the study of gender biases associated with human CVD. Some observations have suggested a role of sex hormones in zebrafish cardiac development and function. Inhibition of E2 synthesis treatment with aromatase enzyme induces a phenotype similar to congestive heart failure and tamponade in zebrafish embryos (Allgood Jr et al. 2013). These conditions are reversed by estradiol (E2) treatment, which has been shown to affect heart rate during zebrafish embryonic development (Romano et al. 2017). Despite these findings, the literature in zebrafish heart regeneration is primarily based on studies of a single sex (usually male) and sexual differences in regeneration have never been investigated. In the present study, we examine, for the first time, sexual dimorphism of zebrafish heart regeneration and factors that influence the rate of cardiac regeneration.

Materials and methods

Zebrafish maintenance

Zebrafish AB line was acquired from the Zebrafish International Resource Center (ZIRC; Eugene, OR, USA). Fish were maintained in a recirculating system at 28 ± 1°C with a photoperiod of 14 h light/10 h dark as described previously (Xu et al. 2018). All the animal procedures used in this study were approved by the Department of Health, Hong Kong, SAR, China (refs (17-18) in DH/HA&P/8/2/5 Pt.1).

Animal surgery

Adult zebrafish (12- to 18-month-old, the weight is 0.35–0.37 g, with cardiac weight accounting for 0.5% of body weight) were anesthetised by immersion in 0.04% MS-222 (E10521; Sigma-Aldrich) for 3–5 min and then immobilized on a wet sponge. In the sham operation, the heart was exposed but without any further treatment. For ventricular amputation, a portion of the ventricle was excised by using surgical fine scissors (Poss et al. 2002). For cryoinjury, the ventricle was touched for 10–12 s with a metal probe pre-chilled in liquid nitrogen (Chablais et al. 2011). For fin amputation, the zebrafish caudal fin was cut using a blade after anesthetization (Nachtrab et al. 2011). After the operation, fish were placed in a tank of fresh water and revitalization was accelerated by pipetting water onto the gills for a couple of minutes and subsequently. Zebrafish were killed by immersion in overdose concentration of MS-222 at different time points.

Chemical exposure

Adult male and female zebrafish, untreated or post surgery, were incubated in water containing 17β-estradiol (E2; E1132, Sigma-Aldrich) at 1 nM, or tamoxifen (T9262, Sigma-Aldrich) at 1 μM, or DMSO (D5879, Sigma-Aldrich), which was used to prepare E2 and tamoxifen, at matching concentrations. The water was changed daily, and the fish were continuously exposed to the vehicle or drugs for durations indicated in Figs 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

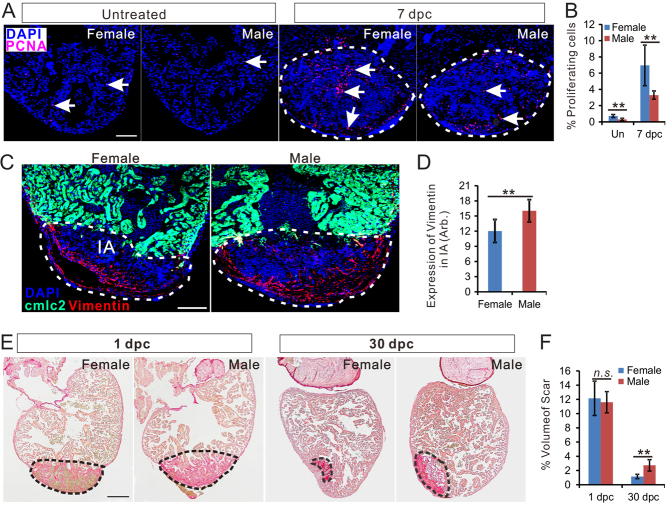

Figure 1.

Zebrafish heart regeneration is sexually dimorphic. (A) PCNA immunofluorescence (red) in the heart of untreated female, untreated male, 7 dpc female (c) and 7 dpc male. Scale bars: 100μm. (B) Quantification of percentage of PCNA-positive cells (mean ± s.d., n = 7) in panel A. (C) Vimentin immunofluorescence (red) in female and male Tg (cmlc2: eGFP, green) zebrafish hearts at 7 dpc. Scale bars: 100 μm. (D) Quantification of vimentin expression in the injured area of female and male zebrafish heart (marked by dashed lines, mean ± s.d., n = 8). (E) Picrosirus red staining of female and male zebrafish hearts at 1 dpc and 30 dpc. (F) Quantification of scar volume (marked by dashed lines, mean ± s.d., n = 9~12) between females and male zebrafish. Scale bars: 200 μm. Two-tail t test in figure B, D and F, **P < 0.01, n.s., not significant. Un, untreated; Dpc, days post-cryoinjury; CI, Cryoinjury.

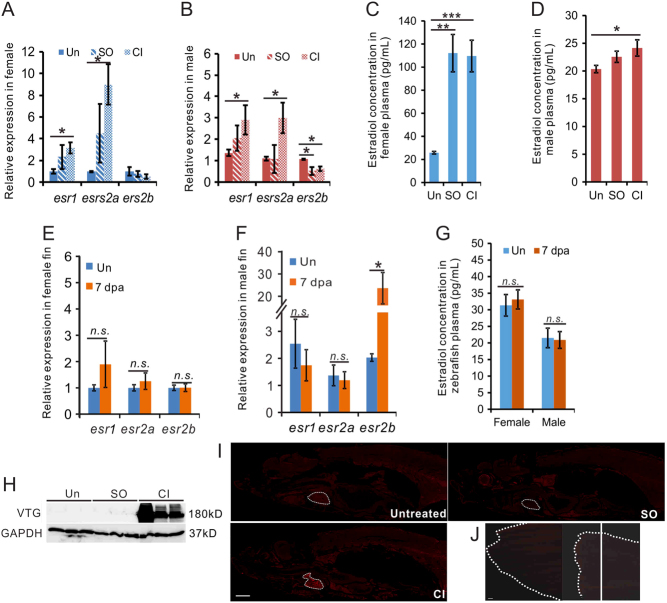

Figure 2.

Cardiac damage increased estrogen expression in zebrafish. (A, B, C, D, E, F and G) qRT-PCR showing the expression of estrogen receptor genes in the heart (A, B) and fin (E, F) of zebrafish 7 days after CI; and plasma E2 concentration in zebrafish with heart (C, D) or fin (G) injury at 7 days. n = 3, two-tail t test (A, B, E, F, G), and one-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc test (C, D), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n.s, not significant. (H) Detection of vitellogenin by Western blotting of plasma collected from three independent untreated male zebrafish and fish one day after SO and CI. (I) Detection of VTG (red) in untreated male zebrafish and in male zebrafish on day 7 after heart CI and SO. Scale bars: 1 mm. (J) Detection of VTG in uninjured caudal fin and on 7 days after fin amputation. The dashed white line showed the shape of fin, and the white line showed the amputation site. Scale bar: 1 mm. Un, untreated; SO, sham-operation; and CI, cryoinjury.

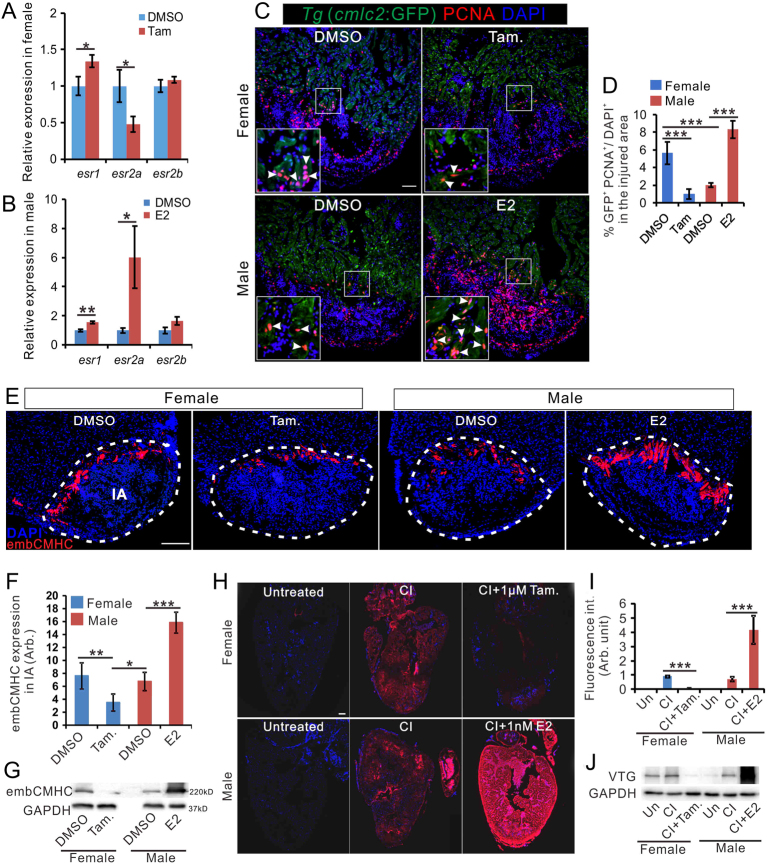

Figure 3.

Estrogen promotes regeneration in zebrafish heart. (A and B) qRT-PCR showing the expression of estrogen receptor genes in the heart of female fish (A) and male zebrafish (B) with DMSO, tamoxifen or E2 treatment at 7 days after cryoinjury. n = 3. (C) PCNA immunofluorescence (red) in the heart of male Tg (cmlc2: eGFP) zebrafish exposed to 1 nM E2 for 7 days after CI. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D). Quantification of proliferating cardiomyocytes in panel C (mean ± s.d., n = 5). One-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc test, *P = 0.05, ***P < 0.001. (E) embCMHC immunofluorescence (red) in the heart of untreated females, females treated with 1 μM tamoxifen (Tam.), untreated males, and males treated with 1 nM E2 for 7 days after CI. Scale bar: 200μm. (F) Quantification of embCMHC staining in panel E (mean ± s.d., n = 4~5) in the injured area. One-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc test, *P = 0.05, **P = 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (G) Expression of embCMHC in the sample shown in E, as detected by Western blotting. (H) Vitellogenin (VTG) immunofluorescence (red) in the heart of untreated females, 7 dpc females, 7 dpc females treated with 1 μM Tamoxifen, untreated males, 7 dpc males, and 7 dpc males treated with 1nM E2. Scale bar: 100 μm. (I) Quantification of VTG staining (mean ± s.d., n = 4~5) in panel H. One-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc test, ***P < 0.001. (J) Expression of VTG in samples shown in panel H, as detected by Western blotting. Un, untreated, SO, sham-operation, and CI, cryoinjury.

Figure 4.

Estrogen accelerates scar reduction and promotes recovery of cardiac function. (A) Picrosirus red staining of the heart from female zebrafish treated with DMSO, E2 (1 nM) and tamoxifen (1 μM); and male zebrafish treated with DMSO and E2 (1 nM) at 30 dpc. Scale bar: 200 μm. (B) Quantification of scar volume from samples in panel A (marked by dash lines, mean ± s.d., n = 5~6). One-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. (C) Fractional shortening (FS) measured by echocardiography of male zebrafish before (basal) and at different time points during recovery in DMSO or E2 (1 nM) after CI. Two-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc test, *P < 0.05, n = 5~6.

Figure 5.

Estrogen induces inflammation in the injured zebrafish heart. A. Gene Ontogeny (GO) terms significantly enriched in genes differentially expressed in female vs male hearts at 7 dpc, n = 3. (B) Comparison of gene expression patterns at 7 dpc in the hearts of female vs male, E2 (1 nM)-treated male vs untreated male, and tamoxifen (1 μM)-treated female vs untreated female, n = 3. (C) Expression of immune and inflammation-related genes in the datasets, n = 3. (D, E and F) Expression of ifn-γ at 7dpc in female and male zebrafish heart and uninjured fish (D). Tamoxifen decreased (E) and E2 increased (F) the expression of ifn-γ in females and males at 7 dpc. n = 4, two-tail t test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (G and H) Western blot of STAT1 and STAT3 in female and male heart at 7 dpc using different treatments. H, bar chart showing the quantification of STAT1 expression in male fish in panel G, n = 3, two-tail t test, *P < 0.05.

Western blotting

Proteins from zebrafish hearts were extracted by using RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer (89901, Thermo Scientific) according to manufacturers’ instructions. The BCA Protein Assay kit (23225; Thermo Scientific) was used to determine the total protein concentration of zebrafish plasma and heart protein extract, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A sample of 20 μg protein per lane was separated in a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to a PVDF membrane (10600023; GE Healthcare Life Science). The blot was blocked in 5% no fat milk in PBST (0.05% Tween 20 in 1× PBS) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation in primary antibodies diluted in PBST overnight at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-GAPDH (60004-1; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA) at 1:10000, mouse anti-zebrafish vitellogenin, JE-2A6 (V01408102; Biosense, Bergen, Norway) at 1:2000, mouse anti-embCMHC (N261.1, DSHB, Iowa City, IA, USA) at 1:500, rabbit anti-STAT1 and rabbit anti-STAT3 (R1408-2 and ET1607-38, both from Huabio, Hangzhou, China) at 1:2000. The following secondary antibodies (all from Millipore) were used: HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (AP160P) at 1:5000, and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (AP307P) at 1:5000. The proteins were detected with the EMD Millipore Luminata Western HRP chemiluminescence substrate (WBLUF0500; Millipore) and the signals were visualized with the Western blotting system (C600; Azure Biosystems, Dublin, CA, USA). The band densities were quantified using ImageJ.

Histology

Organs dissected from zebrafish were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin as previously described (Chablais et al. 2011). To measure scar size, the scar volume percentage to the entire ventricle was calculated by summating data from all sections (Xu et al. 2018). For the whole mount paraffin sections, the fish were fixed with 2% PFA and 0.05% glutaraldehyde in 80% HistoChoice (H120, Amresco, Cleveland, OH, USA) with 1% sucrose and 1% CaCl2 at 4°C for 24 h. The paraffin sections were prepared according to Kong et al. (2008).

For immunohistochemistry, antigen retrieval was performed on dewaxed sections in sodium citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0) at 95°C for 15 min. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-vimentin (ab8978; Abcam) at 1:200; mouse anti-PCNA (sc-56; Santa Cruz) at 1:200; mouse anti-zebrafish vitellogenin, JE-2A6 at 1:200, mouse anti-embCMHC at 1:50, rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP (ab13970; Abcam) at 1:200. The following secondary antibodies (all from Invitrogen) were used: Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse (A10521) or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (A11034) antibodies at 1:500. The sections were mounted with a cover slide in 50% glycerol with PBS and images were acquired using an Olympus BX61 microscope.

Plasma E2 concentration measurement

Plasma from three individual females or males were pooled, and three biological replicates were performed (Babaei et al. 2013). The concentration of E2 in plasma was measured using Estradiol ELISA Kit (582251, Cayman).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from zebrafish heart and fin using NucleoZOL reagent (740404; MACHEREY-NAGEL, Düren, Germany). Three fish were pooled together as one biological replicate, and three replications were performed. A sample of 1 μg total RNA was decontaminated using RQ1 RNA-free DNase (M6101; Promega) and then cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (6210B; Takara) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The expression of each gene was determined by qRT-PCR using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq (RR402A; Takara), and β-actin was used as the reference gene. The qRT-PCR analysis was performed in triplicate for each gene, and the results were analysed using the 2ΔΔCT method. All levels of gene expression were normalized to β-actin and fold change was calculated by setting the control females to 1. The primer sequences are list in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequence for qRT-PCR.

| Gene | Sequence |

|---|---|

| esr F | CAGGACCAGCCCGATTCC |

| esr R | TTAGGGTACATGGGTGAGAGTTTG |

| esr2a F | CTCACAGCACGGACCCTAAAC |

| esr2a R | GGTTGTCCATCCTCCCGAAAC |

| esr2b F | CGCTCGGCATGGACAAC |

| esr2b R | CCCATGCGGTGGAGAGTAAT |

| ifn-γ F | CTATGGGCGATCAAGGAAAA |

| ifn-γ R | CTTTAGCCTGCCGTCTCTTG |

| β-actin F | GCTGACAGGATGCAGAAGGA |

| β-actin R | TAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGGAC |

| vtg1 F | ACTACCAACTGGCTGCTTAC |

| vtg1 R | ACCATCGGCACAGATCTTC |

| vtg2 F | GGTGACTGGAAGATCCAAG |

| vtg2 R | TCATGCGGCATTGGCTGG |

| vtg3 F | CAGATGGCTTTATCGGCGTGAC |

| vtg3 R | CACGGCAGGCCCATTGAAAC |

| vtg4 F | TCACTGTTCCCATCAATCCA |

| vtg4 R | TACAAACATCTCAACAATTAGCA |

| vtg5 F | GATTCCAGAGATCACAATGTCA |

| vtg5 R | CAATTAAACATTCATCACACATG |

| vtg6 F | GGATTCACAAGTATATTAAGGAGG |

| vtg6 R | ACACTTGCAGGGTATTTATTAGC |

| vtg7 F | ATTCCTCTGCCAGTTGCTGT |

| vtg7 R | ACTTGCAGAGAGGACGTTTATT |

For RNA sequencing, total RNA was extracted and decontaminated, and sequencing was performed using the BGISEQ-500 platform, generating an average of 21.83 M reads per sample. The reference genome can be accessed at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/50?genome_assembly_id=210873. The sequencing and primary analysis were performed by BGI (Shenzhen, China), three replicates of each sample were performed. Comparative GSEA (Gene set enrichment analysis) was performed and union enrichment maps were constructed using the R package HTSanalyzeR2 (https://github.com/CityUHK-CompBio/HTSanalyzeR2). The purpose here was on biological processes using Gene Ontology (GO). A 1000 folds permutation was employed to derive statistical significance with an adjusted P value <0.05.

Echocardiography

For echocardiography, zebrafish were anaesthetized with 0.02% MS-222 and fixed on a sponge in the supine position. The echocardiography was performed using the Vevo LAZR Multi-modality Imaging Platform (FUJIFILM VisualSonics) under B-mode (50 MHz, 77 fps) at 20°C as previously described (González-Rosa et al. 2014, Hein et al. 2015, Wang et al. 2017). Ejection fraction (EF, which indicates the volumetric output of blood from the heart) and fractional shortening (FS, which indicates the systolic function of the heart) were acquired using a plug-in of Vevo LAB (Vevo Strain) under B-mode images. The window was set to be 300 frames long, starting with diastalsis.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Three different images were taken for each heart to use for immunofluorescent quantification. The percentages of proliferating cells in the ventricle or injured area was calculated as the ratio of PCNA positive cells/DAPI. For untreated fish, all nuclei in the whole ventricle were counted; for the cryoinjured zebrafish, only the nuclei in the injured area were counted (marked by a white dash line in Fig. 1). The area of vimentin and embCMHC expression were quantified in the injured area using ImageJ. The percentage of the expression with respect to the area of the injured area was calculated as previously described (de Preux Charles et al. 2016b ). For quantification of proliferating cardiomyocytes, the PCNA+/GPF+/double positive cardiomyocytes within 100 μm of the vicinity of the injured area were calculated, and normalized with the injured area as seen in Figs 3C and 6B. The data were expressed as the mean ± s.d.. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s two-tailed t-test and a one-way ANOVA. In some experiments (as indicated in Figure legends, a two-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc test was used.

Figure 6.

Estrogen preconditioning treatment promotes zebrafish heart regenerative process. (A) Experimental design of data presented in this figure. (B) PCNA immunofluorescence (red) in the heart of male Tg (cmlc2: eGFP) zebrafish heart from regimens R1-R4. Arrowheads in the white line bounded area indicate proliferating cardiomyocytes (PCNA+/GFP+). Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Quantification of proliferating cardiomyocytes (PCNA+/GFP+) in panel B (mean ± s.d., n = 4~5). One-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc test, *P < 0.05. (D) embCMHC immunofluorescence (red) in the male heart from regimens R1-R4. (E) Quantification of embCMHC staining in panel E (mean ± s.d., n = 5~6) in the injured area. Scale bars: 100 μm. One-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc test, *P = 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Results

Zebrafish heart regeneration is sexually dimorphic

Female and male zebrafish, matched for age and weight, were subjected to cardiac damage by cryoinjury. On day 7 post cryoinjury (7 dpc), female hearts contained a significantly higher number of PCNA-positive cells (Fig. 1A) and less vimentin immunoreactivity (Fig. 1C) compared to male zebrafish (Fig. 1B and D). These results indicate more cell proliferation and fewer scar-forming fibroblasts in the regenerating female heart. Uninjured female hearts contained a significantly higher number of PCNA-positive cells compared to male hearts (Fig. 1A and B), indicating a higher baseline proliferative activity in female cardiomyocytes. We compared the relative scar volume in female and male hearts and showed that while scar volume was similar in both sexes at 1 dpc, scar volume in male fish was about two-folds larger than in female fish at 30 dpc (Fig. 1E and F). Together, these data support sexual dimorphism of zebrafish heart regeneration, with females regenerating their hearts faster than males.

Endocrine disruption of zebrafish following cardiac injury

Our observations on the sexual dimorphism of zebrafish heart regeneration prompted us to examine the involvement of estrogen in this process. toward this aim, the expression of all three nuclear ERs (Lu et al. 2017) was examined in zebrafish heart after cryoinjury or sham operation, as well as in the heart of uninjured fish (untreated). A sham operation was performed by identical procedures that preceded in cryoinjury, including the opening of thoracic cavity and exposing the heart. At 7 days post surgery, the expression of esr1 and esr2a was significantly induced in female hearts (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the expression of these two ERs in male hearts was also significantly increased, though their increase was not as pronounced as in the female heart (Fig. 2B). Sham operation induced the expression level of esr2a (in female) and esr1 (in both sexes), but to a lesser extent compared to the effect of cryoinjury. Esr2b was suppressed by both cryoinjury and sham operation in either sex.

We asked whether the E2 level in fish was affected after heart injury, as ERs are estrogen inducible genes. As expected, the plasma E2 level in untreated female fish (~25.8 pg/mL) was slightly higher than in males (~20.4 pg/mL) (Fig. 2C and D). Consistent with the upregulation of esr1 and esr2a, the plasma E2 level was increased ~5-fold in both sham-operated and cryoinjured female fish (Fig. 2C). Plasma E2 in male fish was increased by 20 and 10% after cryoinjury and sham-operation, respectively (Fig. 2D). However, the expression of esr1 and esr2a in the fin was not significantly altered after amputation in either female or male fish, though the expression of esr2b was significantly increased after amputation (Fig. 2E and F). Further, plasma E2 levels after caudal fin amputation were virtually unchanged as compared to untreated controls (Fig. 2G). Overall, these data suggest that injury to the heart, but not other tissues, induces estrogen secretion and response in zebrafish.

To test the biochemical consequence of this hormonal change, we examined the sexual dimorphism in zebrafish plasma proteins (Babaei et al. 2013, Li et al. 2016). Quantitative proteomic analysis was used to study the relative abundance of 18 known sexually dimorphic plasma proteins in plasma collected from untreated, sham-operated and ventricular amputated male zebrafish (Supplementary Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 1, see section on supplementary materials given at the end of this article). Most female-biased plasma proteins increased after cardiac damage, as compared to sham operation. Conversely, all but two male-biased plasma proteins were downregulated after ventricular injury. These data indicate that although the impact of heart injury on estrogen levels in males was relatively minor, it was sufficient enough to shift the gender characteristic of the male zebrafish plasma toward a more feminised phenotype.

Western blotting detected vitellogenin in the plasma of male zebrafish as early as day 1 after both cryoinjury (Fig. 2H) compared to sham or uninjured fish. Our plasma proteomic analysis indicated the presence of vitellogenin isoforms in the plasma of male zebrafish after heart injury (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Vitellogenin is specifically expressed in females and is routinely used as a biomarker for endocrine disruption in males (Scott & Robinson 2008). Vitellogenin has been reported to be an acute phase response protein, overexpressed within hours after LPS stimulation (Tong et al. 2010). However, the abundance of vitellogenin in the plasma was much higher in heart-damaged fish than in sham-operated fish, even though the latter also suffered from extensive tissue damage. Moreover, plasma proteomics showed that other known acute phase response proteins (Roy et al. 2017), such as the complement and coagulating factors, were downregulated in the regenerating fish heart compared to the sham-operated fish (Supplementary Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table 2). This suggests that the presence of vitellogenin in male plasma after heart injury is not a consequence of the injury-related infection, but is specifically associated with heart regeneration.

In female fish, vitellogenin is synthesised in the liver and transported via plasma to the oocytes (Hara et al. 2016). To test whether the overexpression of vitellogenin in male fish could be traced back to liver, we measured the mRNA levels of seven known vitellogenin isoforms (Wang et al. 2005) in zebrafish after SO or CI (Supplementary Fig. 3). We observed that both treatments led to a significant increase of all vitellogenin isoforms, especially VTG5. The increase of vitellogenin expression at RNA level in the liver of SO fish was not consistent with our immunofluorescence observations, suggesting that post-transcriptional mechanisms may be involved in regulating VTG protein levels in heart regeneration.

We then examined the tissue distribution of vitellogenin in male zebrafish during heart regeneration. Whole mount immunohistochemistry showed that vitellogenin accumulated in the injured heart of male fish (Fig. 2I) and was not observed in the proximity of the chest wound of sham-operated fish. This indicates that vitellogenin accumulation in male fish is specifically associated with cardiac damage and is not related to general wound healing. Moreover, vitellogenin was not detectable in the male caudal fin on day 7 after amputation (Fig. 2J), confirming that vitellogenin accumulation is not a general consequence of tissue regeneration or repair, but more pertinent to cardiac injury. The individual tissue immunohistochemistry analysis confirmed that vitellogenin was detected in the heart, but not in the gill, kidney and liver (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Vitellogenin was observed in the entire regenerating heart, not restricted to the wound.

Estrogen promotes heart regeneration in zebrafish

What is the effect of estrogen on heart regeneration? At 7 dpc, tamoxifen inhibited the expression of esr2a in the female heart (Fig. 3A), while E2 increased the expression of esr2a in the male heart (Fig. 3B). Male zebrafish exposed to E2 after cryoinjury displayed a ~4-fold increase in cardiomyocyte proliferation in the vicinity of the injured area (Fig. 3C and D). Additionally, male fish treated with E2 increased cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation, as judged by the expression of embCMHC (Fig. 3E, F and G). Conversely, treatment of female fish with the estrogen receptor antagonist tamoxifen resulted in a ~4-fold decrease in cardiomyocyte proliferation in the vicinity of injured area (Fig. 3A) and ~2-fold decrease in embCMHC expression (Fig. 3E, F and G). Furthermore, E2 treatment of male fish increased the level of vitellogenin in regenerating hearts, while tamoxifen treatment of female fish reduced vitellogenin accumulation (Fig. 3H, I and J).

We then investigated whether tamoxifen and estrogen affected scar degradation after heart injury. Tamoxifen significantly increased scar volume in female fish (Fig. 4A and B), whereas E2 quickened scar degradation in both female and male fish. Moreover, echocardiography, which allows the non-invasive monitoring of cardiac performance of the same fish during regeneration (Wang et al. 2017), indicated that E2 treatment of male fish after cryoinjury accelerated the restoration of fractional shortening (FS) time (but not EF, data not show) to the pre-injury level (Fig. 4C). FS is a parameter that indicates the cardiac contractile force and has previously been shown to correlate with zebrafish cardiac recovery after cryoinjury (Hein et al. 2015). Here, the restoration of FS confirms the role of E2 in promoting the recovery of physiological function after cardiac damage in male zebrafish. Overall, our data show that estrogen promoted the regeneration and the recovery of heart function.

Estrogen enhances immune and inflammatory responses in regenerating heart

To elucidate the mechanism underlying the sexual difference in zebrafish heart regeneration, we performed comparative transcriptomic analyses on RNA extracted from female and male hearts at 7 dpc. A total of 1050 genes were found to be differentially expressed (more than two-fold) and statistically significant across the three replicates between the two sexes (Supplementary File 3). Gene ontology (GO) analyses revealed that most of the biological processes enriched for the female-biased genes were related to immunological functions, such as immune response, inflammatory response and chemotaxis for immune cells. On the other hand, male-biased genes were more diverse in function, such as protein homeostasis, stress response and muscle contraction (Fig. 5A and Supplementary File 4). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Subramanian et al. 2005) confirmed that immune-related pathways were among the most sexually dimorphic in post-injured zebrafish hearts (Supplementary Fig. 2).

To test how much the observed female-specific gene expression pattern in heart regeneration was shaped by estrogen, the respective effects of E2 treatment of male fish, and tamoxifen treatment of female fish, on the transcriptome of injured hearts were investigated. Figure 5B (Supplementary File 5) shows that tamoxifen treatment reversed female-specific gene expression signatures in the injured heart, whereas genes involved in immune response and neutrophil chemotaxis were upregulated in estrogen-treated males. Among the genes whose expression level in injured hearts were sexually dimorphic, and/or reciprocally regulated by E2 and tamoxifen, were interferon-gamma (ifn-γ), interferon regulatory factor 1b (irf1b) and various isoforms of cxcl11 (Fig. 5C and Supplementary File 6). In mammals, both irf1 and cxcl11 are ifn-γ-inducible (Yang et al. 2007, Flodström & Eizirik 1997), suggesting the interferon-gamma pathway maybe instrumental to the sexual dimorphism in heart regeneration. The qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that the expression level of ifn-γ was higher in female than male in both uninjured and 7 dpc heart, though its expression was increased in the female and male heart after injury (Fig. 5D). However, the ifn-γ expression after heart injury was significantly stimulated by E2 treatment in male zebrafish and suppressed by tamoxifen treatment in female zebrafish (Fig. 5E and F), consistent with the role of estrogen in ifn-γ expression in other tissues (Fox et al. 1991, Hao et al. 2013).

Consistent with the female-specific induction of ifn-γ expression, a significant increase in STAT1, whose expression is known to be upregulated by IFN-γ in mammals (Horvath 2004), was observed in regenerating female hearts, but not in males (Fig. 5G). The upregulation of STAT1 in female hearts could be reversed by tamoxifen (Fig. 5G). In males, E2 treatment resulted in a moderate, but statistically significant increase in STAT1 protein in regenerating hearts (Fig. 5G and H). These results are consistent with the recent observation that STAT1 is an estrogen-responsive gene in mammals (Young et al. 2017). Interestingly, it is known that the STAT3 gene is essential to injury-induced cardiomyocyte proliferation (Fang et al. 2013). Our data showed that STAT3 was also induced in female hearts after injury, but this induction was not tamoxifen-sensitive (Fig. 5G), suggesting STAT1 may be more important than STAT3 in orchestrating sexual differences in regeneration rates.

Early estrogen preconditioning sensitizes the zebrafish heart for regeneration

Sham operation preconditioned zebrafish showed more efficient regeneration if their hearts were damaged shortly afterwards, possibly due to an increase in inflammation as a result of thoracotomy (de Preux Charles et al. 2016a ,b ). We observed that sham operation led to a significant increase in the expression of estrogen receptors (Fig. 2A and B) and plasma E2 (Fig. 2C and D) at 7 dpc. To test whether estrogen is instrumental to the preconditioning effect, we treated thoracotomised male zebrafish with tamoxifen and normal male zebrafish with E2 for 2 days prior to cryoinjury (Fig. 6A). As expected, regeneration, as judged by the number of proliferating cardiomyocytes and the expression of embCMHC, were enhanced by thoracotomy (Fig. 6B, C and D), confirming the occurrence of the preconditioning effect. However, this effect was significantly reduced when the fish were exposed to tamoxifen during the preconditioning period (Fig. 6B, C and D). Furthermore, male zebrafish pre-treated with E2 for 2 days prior to cryoinjury showed a significant increase in proliferating cardiomyocytes and embCMHC expression, when compared to DMSO pre-treated fish. Hence, E2 pre-treatment is effective in inducing the preconditioning effect on heart regeneration.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated by cellular, anatomical, physiological and biochemical methods (Figs 1 and 2) that zebrafish heart regeneration is sexually dimorphic. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence of sexual dimorphism in heart regeneration. Sexual differences in regeneration of other tissues have been observed in mammals, but have not been documented for the heart (Harada et al. 2003, Deasy et al. 2007). In zebrafish, the pectoral fin is the only tissue that has been shown to demonstrate a sexually dimorphic regenerative capacity (Nachtrab et al. 2011). Like their hearts, males regenerate the pectoral fin more slowly and often incompletely. However, this phenomenon was not observed as robustly in other fins of the zebrafish (Nachtrab et al. 2011), suggesting that this sexual dimorphism is related to the unique role of pectoral fins in reproduction (Kang et al. 2013).

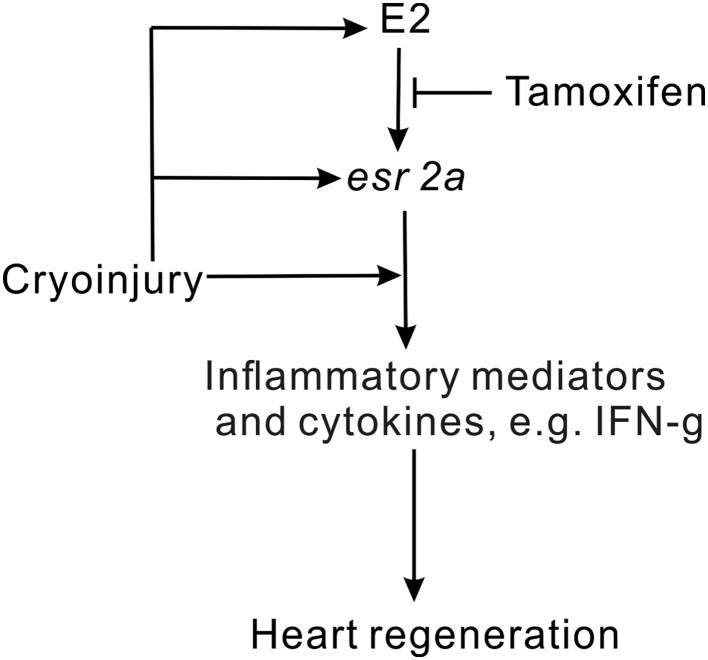

We demonstrated the positive effect of estrogen on heart regeneration: E2 accelerated heart regeneration in males (Figs 3 and 4), and tamoxifen retarded heart regeneration in females (Figs 3 and 4). Our gene expression analyses suggested that female hearts demonstrated a stronger immune and inflammatory responses to cryoinjury. In particular, the expression of ifn-γ, as well as ifn-γ-inducible factors, in regenerating hearts was highly sexually dimorphic and E2 sensitive (Fig. 5). As inflammation is essential for tissue regeneration (Eming et al. 2017), including cardiac repair, our observation is consistent with the higher heart regeneration rate in female zebrafish. Importantly, a comparison between fish species with different heart regeneration rates, reveals that the high heart regeneration capacity of zebrafish is likely due to its enhanced inflammatory response to heart injury (Lai et al. 2017). These authors also discovered that treatment with poly I:C, a viral mimic known to stimulate ifn-γ-responsive genes (Farina et al. 2010), can enable heart regeneration in medaka, a species normally unable to repair heart injuries. The immune-promoting effects of estrogen have been well documented in fish and mammals (Burgos-Aceves et al. 2016, Taneja 2018). In addition, sham operation preconditioning induced inflammation and promoted heart regenerative program (de Preux Charles et al. 2016b ). Interestingly, our data showed that sham-operation was sufficient in increasing the plasma level of E2 in zebrafish (Fig. 2C and D) and that this preconditioning effect is E2 dependent (Fig. 6).

We have revealed a previously unknown aspect of tissue regeneration in zebrafish: endocrine disruption induces the expression of female-specific proteins in males (i.e. vitellogenin). Our data reveal that cardiac damage triggers the expression of estrogen receptors, notably esr2a (Fig. 2A and B) and secretion of E2 (Fig. 2C and D), in both sexes. Interestingly, a genetic variant of esr2 has been identified as a risk factor of myocardial infraction (Domingues-Montanari et al. 2008). Additionally, ERbeta, a mammalian homologue of esr2a, has recently been found to locate in mitochondria and play bioenergetic roles (Liao et al. 2015). In this regard, a ~9-fold increase in esr2a expression in female hearts was observed at 7 dpc (Fig. 2A). Such a dramatic increase in ER expression, compounded by the ~5-fold increase of plasma E2 levels (Fig. 2C), likely sensitises estrogen-responsive genes and amplifies the estrogen-dependent inflammatory response of the female heart. We postulate this can further enhance heart regeneration in females and establish the sexual dimorphism of this process (Fig. 7). The stimulation of estrogen levels and receptors by heart injury also operates in male fish, albeit to a lesser extent. Interestingly, the level of serum estrogen among acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina patients was found to be significantly higher than in the normal group and intensive care patients (AKSUT et al. 1986), suggesting that cardiac lesions, but not other traumas, can lead to an increase in estrogen level in humans. We now show that the unique role of estrogen in heart repair is evolutionarily conserved. For example, endocrine disruption was not associated with zebrafish fin regeneration (this study, Fig. 2J) and estrogen does not affect the rate of fin regeneration in zebrafish larvae (Sun et al. 2019).

Figure 7.

Proposed model estrogen role in zebrafish heart regeneration. Heart cryoinjury triggers the inflammation response and plasma estrogen upregulation. The increase of plasma estrogen induces expression of esr2a, which can be inhibited by tamoxifen. Estrogen promotes heart regeneration through esr2a induced and injury directly induced inflammation response.

It is interesting to examine how the systemic increase of estrogen as a result of heart injury may impact the function of other organs during heart regeneration. One of the consequences of endocrine disruption is the detection of vitellogenin in males, an occurrence generally regarded as the hallmark of endocrine disruption by environmental agents (Scott & Robinson 2008). The accumulation of vitellogenin in regenerating hearts, but not in other tissues (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2C), suggests a functional role in cardiac regeneration, rather than as a collateral consequence of estrogen secretion. We did not detect a significant level of vitellogenin transcripts in regenerating hearts of either sex (data not shown). Our data reveal the synthesis of vitellogenin, especially VTG5, in the male liver after cardiac damage (Supplementary Fig. 3) and its presence in plasma (Fig. 2H and Supplementary Fig. 1B), suggesting that vitellogenin was delivered and accumulated in the damaged hearts. The canonical function of vitellogenin is to transport lipids, calcium and phosphate to developing oocytes (Arukwe & Goksøyr 2003, Hara et al. 2016). We hypothesise that vitellogenin, especially VTG5, might play a similar role in the regenerating heart. Future investigations will include the identification of the target cell types of vitellogenin in the regenerating heart and the characterisation of vitellogenin cargo(s) delivered to these cells.

As a major physiological challenge, tissue regeneration likely requires the coordinated contributions from multiple tissue systems. This study reveals, for the first time, that the involvement of the endocrine and immune systems in zebrafish heart regeneration and establish the use of zebrafish as a model for the study of sexual differences in human cardiac pathology.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This work was supported by a general research fund grant (Project No. CityU 160213) from the Research Grants Council (RGC) of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China, to S H C, and a Strategic Research Grant (Project No. CityU 7004661) from City University of Hong Kong to Y W L.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the University Research Facility in Life Sciences of Hong Kong Polytechnic University for providing Vevo 2100 for this research.

References

- Aksut SV, Aksüt G, Karamehmetoglu A, Oram E. 1986. The determination of serum estradiol, testosterone and progesterone in acute myocardial infarction. Japanese Heart Journal 27 825–837. ( 10.1536/ihj.27.825) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allgood OE, Jr, Hamad A, Fox J, Defrank A, Gilley R, Dawson F, Sykes B, Underwood TJ, Naylor RC, et al 2013. Estrogen prevents cardiac and vascular failure in the ‘listless’ zebrafish (Danio rerio) developmental model. General and Comparative Endocrinology 189 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arukwe A, Goksøyr A. 2003. Eggshell and egg yolk proteins in fish: hepatic proteins for the next generation: oogenetic, population, and evolutionary implications of endocrine disruption. Comparative Hepatology 2 4 ( 10.1186/1476-5926-2-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babaei F, Ramalingam R, Tavendale A, Liang Y, Yan LSK, Ajuh P, Cheng SH, Lam YW. 2013. Novel blood collection method allows plasma proteome analysis from single zebrafish. Journal of Proteome Research 12 1580–1590. ( 10.1021/pr3009226) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos-Aceves MA, Cohen A, Smith Y, Faggio C. 2016. Estrogen regulation of gene expression in the teleost fish immune system. Fish and Shellfish Immunology 58 42–49. ( 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.09.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chablais F, Veit J, Rainer G, Jaźwińska A. 2011. The zebrafish heart regenerates after cryoinjury-induced myocardial infarction. BMC Developmental Biology 11 21 ( 10.1186/1471-213X-11-21) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czubryt MP, Espira L, Lamoureux L, Abrenica B. 2006. The role of sex in cardiac function and disease. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 84 93–109. ( 10.1139/y05-151) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Preux Charles AS, Bise T, Baier F, Marro J, Jaźwińska A. 2016a. Distinct effects of inflammation on preconditioning and regeneration of the adult zebrafish heart. Open Biology 6 160102 ( 10.1098/rsob.160102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Preux Charles AS, Bise T, Baier F, Sallin P, Jaźwińska A. 2016b. Preconditioning boosts regenerative programmes in the adult zebrafish heart. Open Biology 6 160101 ( 10.1098/rsob.160101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deasy BM, Lu A, Tebbets JC, Feduska JM, Schugar RC, Pollett JB, Sun B, Urish KL, Gharaibeh BM, Cao B, et al 2007. A role for cell sex in stem cell-mediated skeletal muscle regeneration: female cells have higher muscle regeneration efficiency. Journal of Cell Biology 177 73–86. ( 10.1083/jcb.200612094) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingues-Montanari S, Subirana I, Tomás M, Marrugat J, Sentí M. 2008. Association between ESR2 genetic variants and risk of myocardial infarction. Clinical Chemistry 54 1183–1189. ( 10.1373/clinchem.2007.102400) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eming SA, Wynn TA, Martin P. 2017. Inflammation and metabolism in tissue repair and regeneration. Science 356 1026–1030. ( 10.1126/science.aam7928) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUGenMed Cardiovascular Clinical Study Group, Regitz-Zagrosek CCS, Oertelt-Prigione V, Prescott S, Franconi E, Gerdts F, Foryst-Ludwig E, Maas AH, Kautzky-Willer A, et al 2015. Gender in cardiovascular diseases: impact on clinical manifestations, management, and outcomes. European Heart Journal 37 24–34. ( 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv598) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Gupta V, Karra R, Holdway JE, Kikuchi K, Poss KD. 2013. Translational profiling of cardiomyocytes identifies an early Jak1/Stat3 injury response required for zebrafish heart regeneration. PNAS 110 13416–13421. ( 10.1073/pnas.1309810110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina GA, York MR, Di Marzio M, Collins CA, Meller S, Homey B, Rifkin IR, Marshak-Rothstein A, Radstake TR, Lafyatis R. 2010. Poly (I:C) drives type I IFN-and TGFβ-mediated inflammation and dermal fibrosis simulating altered gene expression in systemic sclerosis. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 130 2583–2593. ( 10.1038/jid.2010.200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flodström M, Eizirik DL. 1997. Interferon-gamma-induced interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) expression in rodent and human islet cells precedes nitric oxide production. Endocrinology 138 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HS, Bond BL, Parslow TG. 1991. Estrogen regulates the IFN-gamma promoter. Journal of Immunology 146 4362–4367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalez C, Morrison JI. 2014. Cardiac regeneration in non-mammalian vertebrates. Experimental Cell Research 321 58–63. ( 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.08.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Rosa JM, Martín V, Peralta M, Torres M, Mercader N. 2011. Extensive scar formation and regression during heart regeneration after cryoinjury in zebrafish. Development 138 1663–1674. ( 10.1242/dev.060897) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Rosa JM, Guzmán-Martínez G, Marques IJ, Sánchez-Iranzo H, Jiménez-Borreguero LJ, Mercader N. 2014. Use of echocardiography reveals reestablishment of ventricular pumping efficiency and partial ventricular wall motion recovery upon ventricular cryoinjury in the zebrafish. PLoS ONE 9 e115604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao R, Bondesson M, Singh AV, Riu A, Mccollum CW, Knudsen TB, Gorelick DA, Gustafsson JÅ. 2013. Identification of estrogen target genes during zebrafish embryonic development through transcriptomic analysis. PLoS ONE 8 e79020 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0079020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara A, Hiramatsu N, Fujita T. 2016. Vitellogenesis and choriogenesis in fishes. Fisheries Science 82 187–202. ( 10.1007/s12562-015-0957-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H, Pavlick KP, Hines IN, Lefer DJ, Hoffman JM, Bharwani S, Wolf RE, Grisham MB. 2003. Sexual dimorphism in reduced-size liver ischemia and reperfusion injury in mice: role of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase. PNAS 100 739–744. ( 10.1073/pnas.0235680100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein SJ, Lehmann LH, Kossack M, Juergensen L, Fuchs D, Katus HA, Hassel D. 2015. Advanced echocardiography in adult zebrafish reveals delayed recovery of heart function after myocardial cryoinjury. PLoS ONE 10 e0122665 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0122665) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath CM. 2004. The Jak-STAT pathway stimulated by interferon γ. Science’s STKE 2004 tr8 ( 10.1126/stke.2602004tr8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe K, Clark MD, Torroja CF, Torrance J, Berthelot C, Muffato M, Collins JE, Humphray S, Mclaren K, Matthews L, et al 2013. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 496 498–503. ( 10.1038/nature12111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh PC, Segers VF, Davis ME, Macgillivray C, Gannon J, Molkentin JD, Robbins J, Lee RT. 2007. Evidence from a genetic fate-mapping study that stem cells refresh adult mammalian cardiomyocytes after injury. Nature Medicine 13 970–974. ( 10.1038/nm1618) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isensee J, Witt H, Pregla R, Hetzer R, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Noppinger PR. 2008. Sexually dimorphic gene expression in the heart of mice and men. Journal of Molecular Medicine 86 61–74. ( 10.1007/s00109-007-0240-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling C, Sleep E, Raya M, Martí M, Raya A, Belmonte JCI. 2010. Zebrafish heart regeneration occurs by cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nature 464 606–609. ( 10.1038/nature08899) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Nachtrab G, Poss KD. 2013. Local Dkk1 crosstalk from breeding ornaments impedes regeneration of injured male zebrafish fins. Developmental Cell 27 19–31. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong RY, Giesy JP, Wu RS, Chen EX, Chiang MW, Lim PL, Yuen BB, Yip BW, Mok HO, Au DW. 2008. Development of a marine fish model for studying in vivo molecular responses in ecotoxicology. Aquatic Toxicology 86 131–141. ( 10.1016/j.aquatox.2007.10.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai SL, Marin-Juez R, Moura PL, Kuenne C, Lai JKH, Tsedeke AT, Guenther S, Looso M, Stainier DY. 2017. Reciprocal analyses in zebrafish and medaka reveal that harnessing the immune response promotes cardiac regeneration. eLife 6 e25605 ( 10.7554/eLife.25605) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Tan XF, Lim TK, Lin Q, Gong Z. 2016. Comprehensive and quantitative proteomic analyses of zebrafish plasma reveals conserved protein profiles between genders and between zebrafish and human. Scientific Reports 6 24329 ( 10.1038/srep24329) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao TL, Tzeng CR, Yu CL, Wang YP, Kao SH. 2015. Estrogen receptor-β in mitochondria: implications for mitochondrial bioenergetics and tumorigenesis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1350 52–60. ( 10.1111/nyas.12872) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low AK, Russell LD, Holman HE, Shepherd JM, Hicks GS, Brown CA. 2002. Hormone replacement therapy and coronary heart disease in women: a review of the evidence. American Journal of the Medical Sciences 324 180–184. ( 10.1097/00000441-200210000-00003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Cui Y, Jiang L, Ge W. 2017. Functional analysis of nuclear estrogen receptors in zebrafish reproduction by genome editing approach. Endocrinology 158 2292–2308. ( 10.1210/en.2017-00215) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodzadeh S, Eder S, Nordmeyer J, Ehler E, Huber O, Martus P, Weiske JR, Pregla R, Hetzer R, Regitz-Zagrosek V. 2006. Estrogen receptor alpha up-regulation and redistribution in human heart failure. FASEB Journal 20 926–934. ( 10.1096/fj.05-5148com) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachtrab G, Czerwinski M, Poss KD. 2011. Sexually dimorphic fin regeneration in zebrafish controlled by androgen/GSK3 signaling. Current Biology 21 1912–1917. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.050) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostadal B, Ostadal P. 2014. Sex-based differences in cardiac ischaemic injury and protection: therapeutic implications. British Journal of Pharmacology 171 541–554. ( 10.1111/bph.12270) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poss KD, Wilson LG, Keating MT. 2002. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science 298 2188–2190. ( 10.1126/science.1077857) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano SN, Edwards HE, Souder JP, Ryan KJ, Cui X, Gorelick DA. 2017. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor regulates embryonic heart rate in zebrafish. PLoS Genetics 13 e1007069 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007069) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, Ahmed M, Aksut B, Alam T, Alam K, et al 2017. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 70 1–25. ( 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Kumar V, Kumar V, Behera BK. 2017. Acute phase proteins and their potential role as an indicator for fish health and in diagnosis of fish diseases. Protein and Peptide Letters 24 78–89. ( 10.2174/0929866524666161121142221) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallin P, de Preux Charles AS, Duruz V, Pfefferli C, Jaźwińska A. 2015. A dual epimorphic and compensatory mode of heart regeneration in zebrafish. Developmental Biology 399 27–40. ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.12.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott AP, Robinson CD. 2008. Fish vitellogenin as a biological effect marker of oestrogenic endocrine disruption in the open sea. Advances in Fisheries Science 50 472–490. [Google Scholar]

- Senyo SE, Steinhauser ML, Pizzimenti CL, Yang VK, Cai L, Wang M, Wu TD, Guerquin-Kern JL, Lechene CP, Lee RT. 2013. Mammalian heart renewal by pre-existing cardiomyocytes. Nature 493 433–436. ( 10.1038/nature11682) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al 2005. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. PNAS 102 15545–15550. ( 10.1073/pnas.0506580102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Gu L, Tan H, Liu P, Gao G, Tian L, Chen H, Lu T, Qian H, Fu Z, et al 2019. Effects of 17αethinylestradiol on caudal fin regeneration in zebrafish larvae. Science of the Total Environment 653 10–22. ( 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.275) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja V. 2018. Sex hormones determine immune response. Frontiers in Immunology 9 1931 ( 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01931) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Li L, Pawar R, Zhang S. 2010. Vitellogenin is an acute phase protein with bacterial-binding and inhibiting activities. Immunobiology 215 898–902. ( 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.10.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji M, Kawasaki T, Matsuda T, Arai T, Gojo S, Takeuchi JK. 2017. Sexual dimorphisms of mRNA and miRNA in human/murine heart disease. PLoS ONE 12 e0177988 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0177988) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivien CJ, Hudson JE, Porrello ER. 2016. Evolution, comparative biology and ontogeny of vertebrate heart regeneration. NPJ Regenerative Medicine 1 16012 ( 10.1038/npjregenmed.2016.12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Tan JT, Emelyanov A, Korzh V, Gong Z. 2005. Hepatic and extrahepatic expression of vitellogenin genes in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Gene 356 91–100. ( 10.1016/j.gene.2005.03.041) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LW, Huttner IG, Santiago CF, Kesteven SH, Yu ZY, Feneley MP, Fatkin D. 2017. Standardized echocardiographic assessment of cardiac function in normal adult zebrafish and heart disease models. Disease Models and Mechanisms 10 63–76. ( 10.1242/dmm.026989) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whayne TF, Mukherjee D. 2015. Women, the menopause, hormone replacement therapy and coronary heart disease. Current Opinion in Cardiology 30 432–438. ( 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000157) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Webb SE, Lau TCK, Cheng SH. 2018. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) mediate leukocyte recruitment during the inflammatory phase of zebrafish heart regeneration. Scientific Reports 8 7199 ( 10.1038/s41598-018-25490-w) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CH, Wei L, Pfeffer SR, Du Z, Murti A, Valentine WJ, Zheng Y, Pfeffer LM. 2007. Identification of CXCL11 as a STAT3-dependent gene induced by IFN. Journal of Immunology 178 986–992. ( 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.986) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young NA, Valiente GR, Hampton JM, Wu LC, Burd CJ, Willis WL, Bruss M, Steigelman H, Gotsatsenko M, Amici SA, et al 2017. Estrogen-regulated STAT1 activation promotes TLR8 expression to facilitate signaling via microRNA-21 in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical Immunology 176 12–22. ( 10.1016/j.clim.2016.12.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Han P, Yang H, Ouyang K, Lee D, Lin YF, Ocorr K, Kang G, Chen J, Stainier DY, et al 2013. In vivo cardiac reprogramming contributes to zebrafish heart regeneration. Nature 498 497–501. ( 10.1038/nature12322) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a