Abstract

Aim

Ensuring adequate calcium (Ca) intake during childhood and adolescence is critical to acquire good peak bone mass to prevent osteoporosis during older age. As one of the primary strategies to build and maintain healthy bones, we aimed to determine whether dietary Ca intake has an influence on bone mineral density (BMD) in children and adolescents.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study composed of 10,092 individuals from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Dietary Ca intake and total BMD were taken as independent and dependent variables, respectively. To evaluate the association between them, we conducted weighted multivariate linear regression models and smooth curve fittings.

Results

There was a significantly positive association between dietary Ca intake and total BMD. The strongest association was observed in 12–15 year old whites, 8–11 year old and 16–19 year old Mexican Americans, and 16–19 year old individuals from other race/ethnicity, in whom each quintile of Ca intake was increased. We also found that there were significant inflection points in females, blacks, and 12–15 year old adolescents group, which means that their total BMD would decrease when the dietary Ca intake was more than 2.6–2.8 g/d.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study indicated that a considerable proportion of children and adolescents aged 8–19 years would attain greater total BMD if they increased their dietary Ca intake. However, higher dietary Ca intake (more than 2.6–2.8 g/d) is associated with lower total BMD in females, blacks, and 12–15 year old adolescents group.

Keywords: dietary calcium, bone mineral density, child, adolescent, NHANES

Introduction

Calcium (Ca) is the primary nutrient of interest in bone health. It is essential to ensure adequate Ca intake to support the accelerated growth spurt during childhood and adolescence when bone accumulates and grows at a rapid rate (1). During this period, bone mineral density (BMD) acquisition is critical for adult bone mass accrual and skeletal formation; therefore, ensuring adequate Ca intake is critical to acquire a greater peak bone mass to prevent osteoporosis during older age (2).

The recommendations for Ca intake vary by country, and the optimal amount of Ca intake to maintain skeletal growth remains unclear (3). The Ca recommended dietary allowances for US adolescent males and females aged 9 to 18 years is 1.3 g/d and for those aged 4 to 8 and 19 to 50 years old is 1 g/d (4). As one of the primary strategies to build and maintain healthy bones, it is important to determine the influence of dietary Ca intake on BMD. However, the association between Ca intake and better BMD remains controversial (5, 6). Therefore, we aimed to determine whether self-reported dietary Ca intake has an influence on BMD in US children and adolescents at 8–19 years of age using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database.

Methods

Study population

NHANES is the only national survey that provides a cross-sectional picture of nutrition and health in the US population. Its data is collected by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) in biennial cycles. For data researchers and users, the survey data of NHANES are publicly available on the internet. Full details information on NHANES can be found at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/. In the present study, data from 1999 to 2006 were combined for analysis. Of the 12,508 participants aged from 8 to 19 years eligible for this study, only 10,092 participants remained for the final analysis after the exclusion of 2416 subjects with missing dietary Ca intake (n = 492) or total BMD (n = 1924). NCHS ethics review board approved all NHANES protocols, and participants or their proxies provided informed consent prior to participation (7).

Variables

In the present study, the dependent variable was Ca intake. The targeted independent variable was total BMD. The dietary intake of Ca was assessed during an in-person 24-h dietary recall using the automated multiple-pass method (8). The complete descriptions of foods, preparation methods, and portions are ensured by provided prompts. Approximately 7,300 foods are included in the database, and nutrient information for 52 food components can be calculated. Proxy-assisted interviews were completed with children 8–11 years of age, and 12 years and older conducted the interviews on their own. Total BMD measurement was determined by DEXA scans. For covariates in this study, sex, race/ethnicity, physical activity, and Ca supplement use were used as categorical variables; age, BMI, poverty to income ratio, and serum Ca were used as continuous variables. During the mobile examination, BMI was calculated from measured height and weight. The family poverty to income ratio was calculated by dividing family income by the poverty guideline. The information on participation in physical activity over the past 30 days was obtained by open-ended questions from the participants. Ca supplement use was estimated using past 30-day reports. Serum Ca was measured by Beckman Synchron LX20. Details of dietary Ca intake, total BMD measurement process, and other covariate acquisition process can be found at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Statistical analysis

All estimates were calculated accounting for NHANES sample weights. We conducted weighted multivariate linear regression models to evaluate the association of dietary Ca intake with total BMD. Those covariates were adjusted as potential effect modifiers. In the subgroup analyses, we conducted smooth curve fittings to address for the nonlinearity of dietary Ca intake and total BMD after adjustment for the same covariates as in the linear regression models. The continuous variables and categorical variables were expressed as means ± s.d. and percentage, respectively. We conducted weighted linear regression models (continuous variables) or weighted chi-square tests (categorical variables) to calculate the differences among different groups. The statistical software packages R (http://www.R-project.org) and EmpowerStats (http://www.empowerstats.com) were used for the data analyses. Statistical significance was considered when P value was < 0.05.

Results

The description of weighted sociodemographic and medical characteristics is shown in Table 1. Among the participants, 57.14% (n = 5766) are male, 61.47% (n = 6203) are white, 14.57% (n = 1471) are black, and 11.36% (n = 1146) are Mexican American. Among different groups of dietary Ca intake (Quintile, Q1–Q5), age, BMI, income poverty ratio, serum Ca, total BMD, sex, race/ethnicity, physical activity, and Ca supplement use are all significantly different (P < 0.0001). The description of dietary Ca intake and total BMD stratified by age and sex is shown in Supplementary Table 1 (see section on supplementary materials given at the end of this article).

Table 1.

Description of 10,092 participants included in the present study.

| Dietary Ca intake | Total | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 13.56 ± 3.42 | 14.27 ± 3.39 | 13.54 ± 3.42 | 13.20 ± 3.42 | 13.00 ± 3.39 | 13.87 ± 3.33 | <0.0001 |

| Sex (%) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Male | 5766 (57.14%) | 46.21 | 49.37 | 51.74 | 60.80 | 72.62 | |

| Female | 4326 (42.86%) | 53.79 | 50.63 | 48.26 | 39.20 | 27.38 | |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| White | 6203 (61.47%) | 52.64 | 55.92 | 58.97 | 65.43 | 70.91 | |

| Black | 1471 (14.57%) | 21.86 | 17.34 | 15.26 | 12.62 | 8.17 | |

| Mexican American | 1146 (11.36%) | 10.44 | 10.90 | 12.97 | 11.96 | 10.51 | |

| Other | 1272 (12.61%) | 15.05 | 15.83 | 12.80 | 9.98 | 10.41 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.04 ± 5.57 | 23.20 ± 6.10 | 22.26 ± 5.97 | 21.83 ± 5.47 | 21.53 ± 5.21 | 21.64 ± 5.07 | <0.0001 |

| Income poverty ratio | 2.52 ± 1.56 | 2.20 ± 1.51 | 2.45 ± 1.56 | 2.47 ± 1.55 | 2.59 ± 1.54 | 2.77 ± 1.59 | <0.0001 |

| Physical activity (%) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Not walk very much | 307 (3.05%) | 5.13 | 3.98 | 2.89 | 1.98 | 1.88 | |

| Walk a lot | 651 (6.45%) | 9.97 | 6.07 | 6.44 | 4.83 | 5.70 | |

| Climb stairs or hills often | 491 (4.87%) | 6.16 | 4.79 | 3.23 | 4.55 | 5.70 | |

| Weight bearing activity | 1364 (13.50%) | 14.20 | 13.12 | 11.09 | 11.59 | 17.07 | |

| Not recorded | 7279 (72.13%) | 64.54 | 72.04 | 76.35 | 77.04 | 69.72 | |

| Calcium supplement use (%) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| No | 8625 (85.46%) | 89.39 | 87.12 | 84.91 | 82.95 | 83.97 | |

| Yes | 1468 (14.54%) | 10.61 | 12.88 | 15.09 | 17.05 | 16.03 | |

| Serum Ca (mg/dL) | 9.71 ± 0.25 | 9.69 ± 0.28 | 9.71 ± 0.25 | 9.70 ± 0.24 | 9.72 ± 0.24 | 9.74 ± 0.26 | <0.0001 |

| Total BMD (g/cm2) | 1.00 ± 0.16 | <0.0001 | |||||

| 8 to 11 years | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.09 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 0.85 ± 0.08 | 0.85 ± 0.07 | |

| 12 to 15 years | 1.01 ± 0.11 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 1.01 ± 0.10 | 1.01 ± 0.11 | 1.02 ± 0.11 | |

| 16 to 19 years | 1.14 ± 0.11 | 1.13 ± 0.10 | 1.13 ± 0.11 | 1.13 ± 0.10 | 1.15 ± 0.11 | 1.16 ± 0.11 |

Mean ± s.d. for continuous variables: P value was calculated by weighted linear regression model. % for Categorical variables: P value was calculated by weighted chi-square test.

Association between dietary Ca intake and total BMD

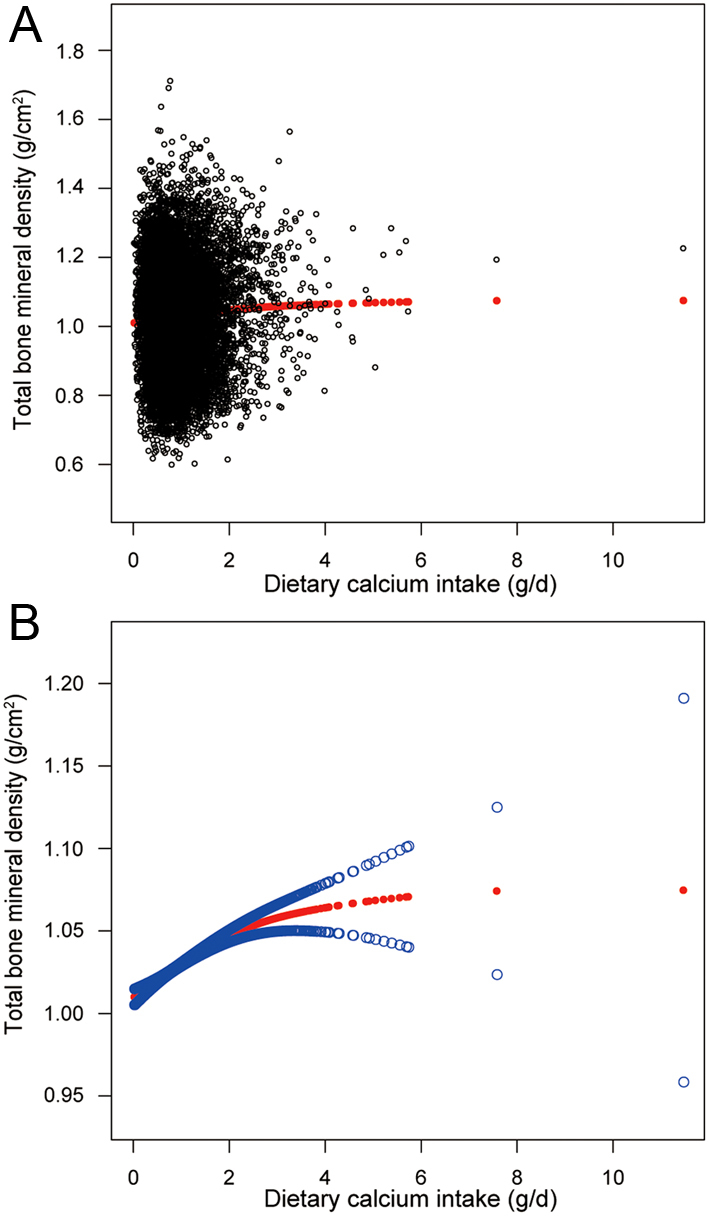

In the fully-adjusted model (Fig. 1 and Table 2), after controlling for the potential confounding factors, we observed a significantly positive association between dietary Ca intake and total BMD (0.0181 (0.0153, 0.0209)).

Figure 1.

The illustrated curved line relation between dietary Ca intake and total bone mineral density. (A) Each black point represents a sample. (B) The area between two blue dotted lines is expressed as a 95% CI. Each point shows the magnitude of the dietary Ca intake and is connected to form a continuous line.

Table 2.

Association of Ca intake with total bone mineral density.

| Model 1 β (95% CI) | Model 2 β (95% CI) | Model 3 β (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca intake | 0.0204 (0.0154, 0.0253) | 0.0177 (0.0148, 0.0206) | 0.0181 (0.0153, 0.0209) |

| Quintiles of Ca intake | |||

| Lowest quintile | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 2nd | −0.026 (−0.036, −0.016) | 0.003 (−0.003, 0.009) | 0.003 (−0.002, 0.008) |

| 3rd | −0.031 (−0.041, −0.021) | 0.011 (0.005, 0.017) | 0.012 (0.006, 0.017) |

| 4th | −0.030 (−0.040, −0.020) | 0.019 (0.014, 0.025) | 0.020 (0.015, 0.026) |

| Highest quintile | 0.010 (0.001, 0.020) | 0.027 (0.022, 0.033) | 0.029 (0.023, 0.034) |

Model 1: no covariates were adjusted. Model 2: age, sex, and race/ethnicity were adjusted. Model 3: age, sex, race/ethnicity, BMI, income poverty ratio, physical activity, Ca supplement use, and serum Ca were adjusted.

In the subgroup analysis stratified by age and race/ethnicity, we observed a positive association of dietary Ca intake with total BMD (Table 3) in whites, blacks, Mexican Americans, and the 12 to 15 years group and 16 to 19 years group of other race/ethnicity. The strongest association was observed in 12–15 year old whites, 8–11 year old and 16–19 year old Mexican Americans, and 16–19 year old individuals from other race/ethnicity, in whom each quintile of Ca intake was increased. Compared with the lowest quintile of dietary Ca intake, the mean BMD was greater in the highest quintile in all groups. We found that trend tests remained significant in all groups except 8–11 year old individuals from other race/ethnicity.

Table 3.

Total bone mineral density by quintiles of dietary Ca intake, stratified by race/ethnicity and age.

| Quintiles of Ca intake | Whites | Blacks | Mexican Americans | Other race |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total BMD g/cm2 (95% CI) | ||||

| 8 to 11 years | ||||

| Lowest quintile | 0.826 (0.810, 0.841) | 0.872 (0.860, 0.883) | 0.805 (0.788, 0.821) | 0.834 (0.810, 0.858) |

| 2nd | 0.819 (0.806, 0.831) | 0.883 (0.872, 0.894) | 0.821 (0.808, 0.834) | 0.830 (0.811, 0.848) |

| 3rd | 0.838 (0.826, 0.849) | 0.881 (0.870, 0.893) | 0.827 (0.817, 0.838) | 0.838 (0.820, 0.856) |

| 4th | 0.848 (0.838, 0.858) | 0.889 (0.878, 0.901) | 0.832 (0.821, 0.842) | 0.852 (0.832, 0.872) |

| Highest quintile | 0.848 (0.837, 0.860) | 0.896 (0.882, 0.911) | 0.837 (0.826, 0.847) | 0.839 (0.817, 0.862) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.284 |

| 12 to 15 years | ||||

| Lowest quintile | 0.982 (0.966, 0.997) | 1.044 (1.033, 1.055) | 0.980 (0.966, 0.993) | 0.989 (0.966, 1.011) |

| 2nd | 0.985 (0.971, 0.998) | 1.065 (1.053, 1.077) | 0.995 (0.983, 1.008) | 0.997 (0.975, 1.019) |

| 3rd | 0.994 (0.980, 1.007) | 1.061 (1.049, 1.074) | 0.988 (0.976, 0.999) | 1.021 (0.995, 1.046) |

| 4th | 1.005 (0.992, 1.018) | 1.061 (1.048, 1.074) | 0.989 (0.978, 1.001) | 0.988 (0.963, 1.012) |

| Highest quintile | 1.024 (1.012, 1.036) | 1.068 (1.052, 1.084) | 1.019 (1.007, 1.031) | 1.028 (1.006, 1.050) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | 0.023 | <0.001 | 0.036 |

| 16 to 19 years | ||||

| Lowest quintile | 1.000 (0.991, 1.009) | 1.062 (1.056, 1.069) | 0.985 (0.978, 0.993) | 1.006 (0.993, 1.019) |

| 2nd | 0.997 (0.989, 1.005) | 1.201 (1.190, 1.212) | 0.998 (0.991, 1.005) | 1.007 (0.995, 1.019) |

| 3rd | 1.010 (1.002, 1.018) | 1.195 (1.182, 1.208) | 0.999 (0.992, 1.005) | 1.018 (1.004, 1.031) |

| 4th | 1.020 (1.013, 1.027) | 1.205 (1.191, 1.219) | 1.004 (0.997, 1.010) | 1.021 (1.006, 1.035) |

| Highest quintile | 1.031 (1.024, 1.037) | 1.223 (1.208, 1.239) | 1.015 (1.008, 1.022) | 1.028 (1.014, 1.042) |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

Sex, BMI, income poverty ratio, physical activity, Ca supplement use, and serum Ca were adjusted.

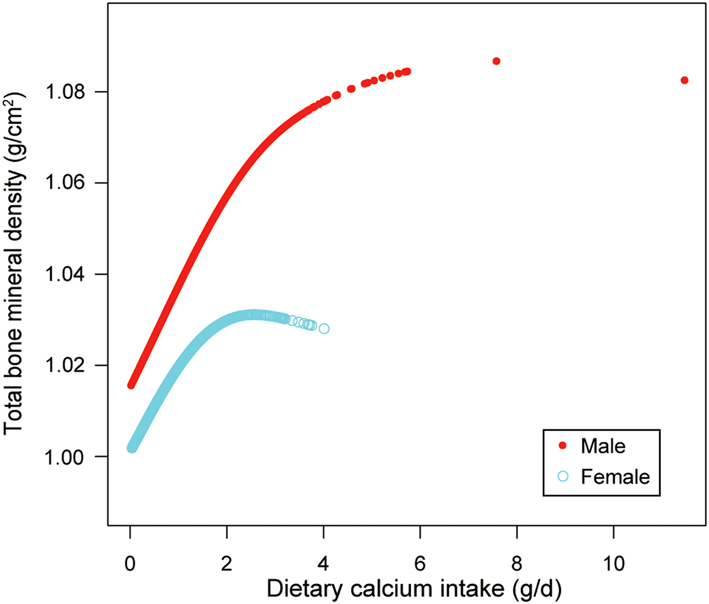

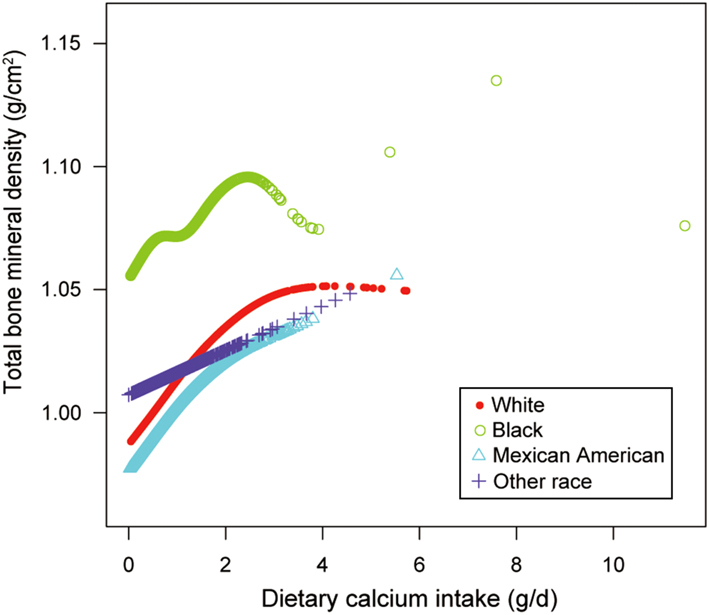

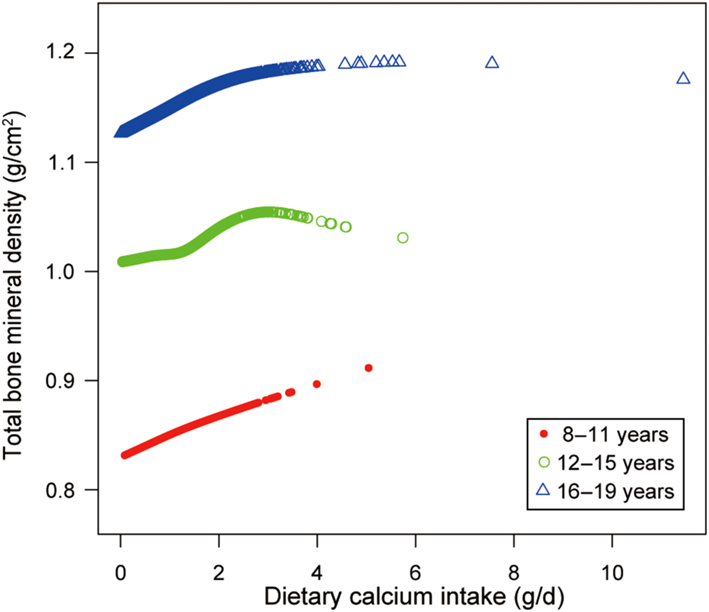

We also tried to use smooth curve fittings to find the nonlinear relationship between dietary Ca intake and total BMD, stratified by age, sex, and race/ethnicity (Figs 2, 3 and 4). We found there were significant inflection points in the 12–15 year group, females, and blacks. These inflection points were almost near 2.6–2.8 g/d.

Figure 2.

The correlation between dietary Ca intake and total bone mineral density, stratified by sex.

Figure 3.

The correlation between dietary Ca intake and total bone mineral density, stratified by race/ethnicity.

Figure 4.

The correlation between dietary Ca intake and total bone mineral density, stratified by age.

Discussion

During the children and pubertal growth spurt, bone modelings require adequate Ca to form and lay down new bone properly. Poor bone mineralization might be prevented from childhood by guaranteeing adequate dietary Ca intake for optimizing bone health (9, 10). In the present cross-sectional study, we found dietary Ca intake positively correlated with total BMD. In addition, the strongest association was observed in 12–15 year old whites, 8–11 year old and 16–19 year old Mexican Americans, and 16–19 year old individuals from other races, in whom each quintile of Ca intake was increased. The trend tests remained significant in all groups except the 8–11 year old other race group.

Similar to our conclusion, a cross-sectional study of the Korea National Survey suggested that a large proportion of young Koreans would attain greater bone mineral content if they increased dietary Ca intake (11). Their data indicated that dietary Ca intake plays a supportive role in bone mass for early adolescents and young adult males. The results of another two cross-sectional studies in Spanish revealed that high Ca intake associated with a higher BMD in children between 5 and 12 years old (12), and total BMD was positively related to Ca intakes in adolescents aged 12.5 to 17.5 years (13), respectively. However, some other studies supported that Ca intake had no effect on BMD (14, 15, 16, 17, 18). A previous review by Lanou et al. (6) reported that nine cross-sectional studies of 13 did not find an association of dietary Ca intake with BMD or bone mineral content in adolescent girls. They also found no significant associations between Ca intake and BMD in eight prospective studies of nine. The inconsistent conclusions of these studies may be mainly attributed to heterogeneity among studies, including differences in sex, age-stage, and race/ethnicity. According to the STROBE statement (19), subgroup analysis can make better use of data. In our subgroup analysis, we found inflection points in the 12–15 year old group, female, and blacks. Their total BMD decreased when the dietary Ca intake was more than 2.6–2.8 g/d.

Although Ca is only one factor contributing to bone mass and strength, it is essential for skeletal mineralization and bone development, especially in individuals with a low intake (20). Thus, adequate dietary Ca intake is considered to be beneficial and has been widely recommended. However, Ca intake exceeding the upper limit was associated with the increased risk of adverse events, such as hypercalciuria, hypercalcemia, and kidney stones (21, 22, 23). Therefore, it is important to balance potential risks against potential benefits. Our results supported that increased dietary Ca intake will be beneficial to bone health in the low Ca intake population. A meta-analysis concluded that Ca intake within tolerable upper intake levels (2000 to 2500 mg/d) is not associated with cardiovascular disease risk in generally healthy adults (24). However, this conclusion still needs to be confirmed by larger prospective studies.

The biggest strength of this study is that the present study includes representative samples of the multiracial population and better generalizability of the US population. Besides, the large sample size allows us to conduct further subgroup analysis. There are also some limitations in our study. First, the observational design of the cross-sectional study does not allow us to determine whether dietary Ca intake influences change in total BMD over time and the cause-effect relations can not be assessed. Second, the use of the 24-h dietary recalls may not reflect habitual intakes, relies on memory, and is susceptible to over-reporting and under-reporting. Besides, the methodology that dietary intake was assessed does not correct for systematic bias that can create excessive noise in the estimation of dietary intake (25). Third, the biases caused by other potential confounding factors are not excluded. For example, as the database of NHANES 1999–2006 lacks the information of dietary vitamin D intake, we did not adjust this potential confounding factor in the present study.

Overall, this cross-sectional study indicated that a considerable proportion of children and adolescents aged 8–19 years would attain greater total BMD if they increased their dietary Ca intake. However, higher dietary Ca intake (more than 2.6–2.8 g/d) is associated with lower total BMD in females, blacks, and 12–15 year old adolescents group. Such a conclusion would warrant further prospective studies of intervention trials.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This work did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Ethical statement

The ethics review board of the National Center for Health Statistics approved all NHANES protocols, and written informed consents were obtained from all participants or their proxies.

Author contribution statement

K Y P and C Y Z contributed to data collection, analysis, and writing of the manuscript. X C Y contributed to study design. Z X Z contributed to study design and writing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the time and effort given by participants during the data collection phase of the NHANES project.

References

- 1.Hodges JK, Cao S, Cladis DP, Weaver CM. Lactose intolerance and bone health: the challenge of ensuring adequate calcium intake. Nutrients 2019. 11 E718 ( 10.3390/nu11040718) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizzoli R, Bianchi ML, Garabedian M, McKay HA, Moreno LA. Maximizing bone mineral mass gain during growth for the prevention of fractures in the adolescents and the elderly. Bone 2010. 46 294–305. ( 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mensink GB, Fletcher R, Gurinovic M, Huybrechts I, Lafay L, Serra-Majem L, Szponar L, Tetens I, Verkaik-Kloosterman J, Baka A, et al Mapping low intake of micronutrients across Europe. British Journal of Nutrition 2013. 110 755–773. ( 10.1017/S000711451200565X) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Gallagher JC, Gallo RL, Jones G, et al The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2011. 96 53–58. ( 10.1210/jc.2010-2704) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huncharek M, Muscat J, Kupelnick B. Impact of dairy products and dietary calcium on bone-mineral content in children: results of a meta-analysis. Bone 2008. 43 312–321. ( 10.1016/j.bone.2008.02.022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanou AJ, Berkow SE, Barnard ND. Calcium, dairy products, and bone health in children and young adults: a reevaluation of the evidence. Pediatrics 2005. 115 736–743. ( 10.1542/peds.2004-0548) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zipf G, Chiappa M, Porter KS, Ostchega Y, Lewis BG, Dostal J. National health and nutrition examination survey: plan and operations, 1999–2010. Vital and Health Statistics: Series 1, Programs and Collection Procedures 2013. 56 1–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moshfegh AJ, Rhodes DG, Baer DJ, Murayi T, Clemens JC, Rumpler WV, Paul DR, Sebastian RS, Kuczynski KJ, Ingwersen LA, et al The US Department of Agriculture Automated Multiple-Pass Method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008. 88 324–332. ( 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.324) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Closa-Monasterolo R, Zaragoza-Jordana M, Ferre N, Luque V, Grote V, Koletzko B, Verduci E, Vecchi F, Escribano J. & Childhood Obesity Project Group. Adequate calcium intake during long periods improves bone mineral density in healthy children. Data from the Childhood Obesity Project. Clinical Nutrition 2018. 37 890–896. ( 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.03.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golden NH. Optimizing bone health in Brazilian teens: using a population-based survey to guide targeted interventions to increase dietary calcium intake. Jornal de Pediatria 2016. 92 220–222. ( 10.1016/j.jped.2016.02.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joo NS, Dawson-Hughes B, Yeum KJ. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, calcium intake, and bone mineral content in adolescents and young adults: analysis of the fourth and fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV-2, 3, 2008–2009 and V-1, 2010). Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2013. 98 3627–3636. ( 10.1210/jc.2013-1480) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suarez Cortina L, Moreno Villares JM, Martinez Suarez V, Aranceta Bartrina J, Dalmau Serra J, Gil Hernandez A, Lama More R, Martín Mateos MA, Pavón Belinchón P. Calcium intake and bone mineral density in a group of Spanish school-children. Anales de Pediatria 2011. 74 3–9. ( 10.1016/j.anpedi.2010.07.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mouratidou T, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Gracia-Marco L, Huybrechts I, Sioen I, Widhalm K, Valtueña J, González-Gross M, Moreno LA. & HELENA StudyGroup. Associations of dietary calcium, vitamin D, milk intakes, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D with bone mass in Spanish adolescents: the HELENA study. Journal of Clinical Densitometry 2013. 16 110–117. ( 10.1016/j.jocd.2012.07.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juzwiak CR, Amancio OM, Vitalle MS, Szejnfeld VL, Pinheiro MM. Effect of calcium intake, tennis playing, and body composition on bone-mineral density of Brazilian male adolescents. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 2008. 18 524–538. ( 10.1123/ijsnem.18.5.524) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward KA, Roberts SA, Adams JE, Lanham-New S, Mughal MZ. Calcium supplementation and weight bearing physical activity – do they have a combined effect on the bone density of pre-pubertal children? Bone 2007. 41 496–504. ( 10.1016/j.bone.2007.06.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbons MJ, Gilchrist NL, Frampton C, Maguire P, Reilly PH, March RL, Wall CR. The effects of a high calcium dairy food on bone health in pre-pubertal children in New Zealand. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2004. 13 341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter LM, Whiting SJ, Drinkwater DT, Zello GA, Faulkner RA, Bailey DA. Self-reported calcium intake and bone mineral content in children and adolescents. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2001. 20 502–509. ( 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719059) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suriawati AA, Majid HA, Al-Sadat N, Mohamed MN, Jalaludin MY. Vitamin D and calcium intakes, physical activity, and calcaneus BMC among school-going 13-year old Malaysian adolescents. Nutrients 2016. 8 E666 ( 10.3390/nu8100666) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. & STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007. 370 1453–1457. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uusi-Rasi K, Karkkainen MU, Lamberg-Allardt CJ. Calcium intake in health maintenance – a systematic review. Food and Nutrition Research 2013. 57 21082 ( 10.3402/fnr.v57i0.21082) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xargay-Torrent S, Espuna-Capote N, Montesinos-Costa M, Prats-Puig A, Carreras-Badosa G, Diaz-Roldan F, De Zegher F, Ibáñez L, Bassols J, López-Bermejo A. Serum alkaline phosphatase relates to cardiovascular risk markers in children with high calcium-phosphorus product. Scientific Reports 2018. 8 17864 ( 10.1038/s41598-018-35973-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chrysant SG, Chrysant GS. Controversy regarding the association of high calcium intake and increased risk for cardiovascular disease. Journal of Clinical Hypertension 2014. 16 545–550. ( 10.1111/jch.12347) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D, Calcium. The National Academies Collection: reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Eds Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL. & Del Valle HB. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press (US), 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung M, Tang AM, Fu Z, Wang DD, Newberry SJ. Calcium intake and cardiovascular disease risk: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine 2016. 165 856–866. ( 10.7326/M16-1165) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mangano KM, Walsh SJ, Kenny AM, Insogna KL, Kerstetter JE. Dietary acid load is associated with lower bone mineral density in men with low intake of dietary calcium. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2014. 29 500–506. ( 10.1002/jbmr.2053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a