Abstract

Hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) by 3O2 and HO2• from arenols (ArOH), aryloxyls (ArO•), their tautomers (ArH), and auxiliary compounds has been investigated by means of CBS-QB3 computations. With 3O2, excellent linear correlations have been found between the activation enthalpy and the overall reaction enthalpy. Different pathways have been discerned for HATs involving OH or CH moieties. The results for ArOH + HO2 → ArO• + H2O2 neither afford a linear correlation nor agree with the experiment. The precise mechanism for the liquid-phase autoxidation of anthrahydroquinone (AnH2Q) appears to be not fully understood. A kinetic analysis shows that the HAT by chain-carrying HO2• occurs with a high rate constant of ≥6 × 108 M–1 s–1 (toluene). The second propagation step pertains to a diffusion-controlled HAT by 3O2 from the 10-OH-9-anthroxyl radical. Oxanthrone (AnOH) is a more stable tautomer of AnH2Q with a ratio of 13 (298 K) in non-hydrogen-bonding (HB) solvents, but the reactivity toward 3O2/HO2 is much lower. Combination of the computed free energies and Abrahams’ HB donating (α2H) and accepting (β2) parameters has afforded an α2H(HO2) of 0.86 and an α2H(H2O2) of 0.50.

1. Introduction

Autoxidation or combustion of organic matter (RH) with molecular (triplet state) oxygen is a complex (radical chain) process involving a plethora of individual reaction steps.1−5 The hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from RH toward molecular oxygen may be considered as the first radical-generating initiation reaction under (generally unrealistic) “clean” conditions.

| 1 |

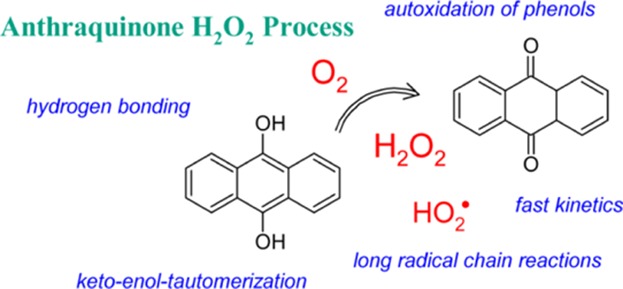

Equation 1 constitutes a reverse radical disproportionation (RRD), whose enthalpy of activation is supposedly (almost) equal to the enthalpy of reaction, that is, ΔH⧧(1) ≅ ΔRH(1). In view of the high endothermicity for closed-shell species, this reaction may only be of some importance at elevated temperatures. Under low-temperature (autoxidation) conditions, an appropriate initiation process (e.g., homolysis of a thermally labile compound, photolytically initiated bond cleavage, radical generation by redox processes, and so forth.) is required for the formation of radical species. One of the exceptions seems to be the (aut)oxidation of anthrahydroquinone (9,10-anthracenediol, AnH2Q), with molecular oxygen in the liquid phase at around 323 K, yielding hydrogen peroxide.6−8 This is the main industrial route (with 2-alkyl-AnH2Q) to hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, an environmentally benign bleaching agent, with a worldwide manufacturing of more than 4 × 106 tons/year.7 Following a vast body of studies dealing with autoxidation processes in chemistry and biology, the prevailing mechanism for the H2O2 synthesis can most reasonably be presented by a straightforward radical chain sequence (Scheme 1), involving initiation, propagation, and termination reactions.3−5 In the rate-determining propagation step (eq 2), the initially formed hydroperoxyl radical, HO2•, abstracts a hydrogen atom from AnH2Q, leading to H2O2 and the anthraquinonyl (anthrasemiquinone) radical, AnHQ•. Subsequently, the HAT from AnHQ• to oxygen regenerates the radical chain carrier, HO2, and yields anthraquinone, AnQ, as the second reaction product (eq 3).

Scheme 1. Anthraquinone Process for H2O2 Production.

In the next stage of the industrial process, AnQ is recycled back to AnH2Q by means of catalytic hydrogenation. A frequently cited erroneous representation of this mechanism is displayed in the Appendix section.

This synthetic method has been developed around 70 years ago. However, in 2011, Yoshizawa et al. claimed that ... the reaction mechanism of the autoxidation process of AnH2Q has remained unknown.9 or, in 2015, ... the reaction mechanism still remains a matter of debate.10 By means of a computational (density functional theory, DFT) investigation, the authors arrive at the conclusion that the rate-determining step consists of hydrogen atom abstraction by triplet oxygen from AnH2Q (Scheme 2, eq 4a). This results in the formation of an intermolecular hydrogen-bonded complex, AnHQ•–HO2•, with the hydroperoxyl radical acting as the hydrogen bond donor (HBD). Then, after intersystem crossing, the in-cage HAT (eq 4b) affords AnQ and hydrogen peroxide. Hence, AnH2Q oxidation proceeds through a straightforward bimolecular reaction.

Scheme 2. Proposed One-Step Mechanism for AnH2Q Oxidation.

However, it should be noted that hydrogen bonding (HB) is an equilibrium phenomenon and occurs at the nanosecond time scale. Under the liquid-phase conditions, the concentrations of other hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), such as AnH2Q or AnQ, or even the solvent, are much higher than [AnHQ•], which would greatly reduce the overall rate of eq 4. A ΔG⧧(4a) of 12 kcal mol–1 has been computed at the B3LYP/6-311G** level of theory, which leads to a rate constant of k(4a) = 1.4 × 106 M–1 s–1 at 323 K.8,9,11 This implies that under the conditions of constant oxygen concentration, the half-life of AnH2Q would be around 50 ms. Such a fast reaction implies that the rate of dissolution of oxygen into the liquid becomes rate-limiting. This feature has not been reported in the literature; thus, it appears highly improbable that eq 4a can be considered as the rate-determining step.

The keto–enol tautomerization of arenols and methylacenes has been studied quite in detail by the experiment and theory.12,13 In a CBS-QB3 computational study on the tautomerization of hydroxyarenes, we confirmed that the keto–enol ratio increases dramatically along the series phenol, 1-naphthol, and 9-anthrol.12 For the latter, the keto form (anthrone) predominates in the gas phase at 298 K with a ratio of ≥102. These results are in satisfying agreement with the experimental observations concerning inert or poor HB solvents.12 However, the anthrone/9-anthrol equilibrium ratio depends strongly on the applied solvent because of the formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonds with the tautomers. A preliminary calculation on the tautomerization of AnH2Q shows that the keto form (oxanthrone, 10-OH-anthrone, AnOH) is present in about 10-fold excess in the gas phase at 298 K. In the liquid phase, the tautomeric ratio is expected to be determined as well by the HB and hydrogen-donating properties of the medium, as exemplified in Scheme 3 with S (e.g., toluene) as the HBA solvent.8 Interestingly, the role of AnOH in the H2O2 synthesis has not been documented before in a quantitative fashion.

Scheme 3. Intermolecular Hydrogen Bonding Determining the AnOH/AnH2Q Ratio.

A literature survey shows that there are only a very few experimental studies dealing with the thermokinetics of the HAT between an O–H or a C–H bond to molecular oxygen from closed-shell molecules. The kinetic parameters of eq 1 may be determined by measuring the oxygen uptake at various temperatures, but the assignment of the experimental results to solely eq 1 would be questionable because of the unavoidable occurrence of various side reactions.

Remarkably, it appears that the thermokinetics for the individual steps in the conversion of AnH2Q to AnQ and H2O2 has not been scrutinized in any thorough manner. Therefore, we embarked on a systematic study quantifying the thermodynamic parameters for the interaction of oxygen and hydroperoxyl with selected arenols, their tautomers, radicals derived therefrom, and auxiliary compounds employing the composite CBS-QB3 procedure. This computational method is known for its accuracy (1–2 kcal mol–1 deviation from the experiment).14−17 Various families of compounds have been chosen in order to further increase the overall accuracy. The results are used to shed more light on the supposedly unknown mechanism for the oxidation of AnH2Q. The solvent effect on the AnOH/AnH2Q ratio has been investigated with the use of empirical solvent/solute parameters. Intermolecular HB between HO2• and H2O2 with various arenols and aryloxyls has been analyzed to quantify the HBD abilities of these species.

2. Computational Methods

Quantum-chemical computations on the CBS-QB318,19 level of theory were performed with the Gaussian 09 suite of programs.20 All geometries were optimized to stationary points with keywords Opt = Tight and Grid = UltraFine. Transition states (TSs) (one imaginary frequency) were located employing the QST3 method. The vibrational displacement vectors related to the imaginary frequencies were examined in order to ensure the correct assignment of the TS. Zero-point vibrational energies were scaled by a factor of 0.99. Solvation was modeled by the solvation model based on density (SMD) continuum model.21

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. COH + 3O2

The thermokinetic parameters for the HAT reaction with molecular oxygen for a series of arenols, aryloxyls, and auxiliary hydroxyl compounds (eqs 6a and 6b) have been computed by CBS-QB3. The auxiliary compounds have been (rather arbitrarily) selected in order to cover a wide range of reaction energies. The HAT process is formally a RRD reaction, but the TS for H-abstraction from closed-shell molecules is an electronic triplet state and not a singlet state as in RH + RH ⇌ R• + RH2• because of the triplet ground-state configuration of 3O2.13 For the radical species, the reaction with oxygen is computed to proceed on the doublet surface. Table 1 summarizes the results including the activation parameters [ΔG⧧(6), ΔH⧧(6), ΔS⧧(6)], the overall reaction enthalpy, ΔRH(6), the intermolecular hydrogen bond enthalpy, ΔHBH(6), between the products (the lowest-enthalpy conformer, see 3.6), and the O–H bond dissociation enthalpy (BDE).11 Pre-reaction triplet state hydrogen-bonded complexes of the nonradical educts with 3O2 have been identified as well. Weak interactions (ΔHBH = −0.67 ± 0.23 kcal mol–1) for closed-shell compounds (ROH–3O2) and quartet-state complexes of hydroxyl-substitued oxyl radicals (•ROH–3O2) are observed. Details are summarized in Table S1 of the Supporting Information. Further elaborations concerning these species are beyond the scope of this paper.

| 6a |

| 6b |

Table 1. CBS-QB3-Calculated RRD Activation Parameters for HAT Reactions from a Series of Arenols, Aryloxyls, and Auxiliary Hydroxyl Compounds by Molecular Oxygen (eqs 6a and 6b)a.

| compound | ΔG⧧(6) | ΔH⧧(6) | ΔS⧧(6) | ΔRH(6)b | –ΔHBH(6)c | BDEd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ethenol | 39.4 | 30.0 | 31.5 | 35.6 | 9.0 | 84.8 |

| 2-OH-2-CN-ethenol | 30.8 | 21.1 | 32.4 | 24.4 | 7.8 | 73.6 |

| 2-OH-2-CN-ethenoxyl | 8.2 | –3.0 | 37.7 | 0.8 | 5.6 | 50.1 |

| dimethylhydroxylamine | 26.5 | 17.6 | 30.1 | 24.7 | 10.1 | 73.9 |

| phenol | 39.1 | 30.3 | 29.4 | 37.8 | 10.5 | 87.1 |

| 4-OH-phenol | 34.8 | 26.3 | 28.6 | 33.5 | 11.3 | 82.8 |

| 4-OH-phenoxyl | 16.0 | 5.5 | 35.2 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 57.3 |

| 4-MeO-phenol | 34.5 | 25.8 | 29.4 | 33.1 | 11.5 | 82.4 |

| 4-Cl-phenol | 38.2 | 29.4 | 29.5 | 36.8 | 10.4 | 86.0 |

| 2,5-dimethyl-4-OH-phenol | 32.2 | 22.1 | 33.9 | 31.4 | 11.9 | 80.6 |

| 2,5-dimethyl-4-OH-phenoxyl | 14.0 | 3.0 | 37.0 | 6.1 | 9.5 | 55.4 |

| TEMPOHe | 22.1 | 12.3 | 32.8 | 20.8 | 12.5 | 70.1 |

| 1-naphthol | 35.7 | 26.7 | 30.0 | 32.8 | 11.0 | 82.2 |

| 2-methyl-1-naphthol | 32.2 | 23.0 | 31.0 | 30.6 | 9.9 | 79.9 |

| 4-OH-1-naphtholf | 32.0 | 22.9 | 30.5 | 28.9 | 11.9 | 78.2 |

| 4-OH-1-naphthoxyl | 9.4 | –1.5 | 36.6 | 1.1 | 9.4 | 50.4 |

| 9-anthrol | 28.9 | 18.3 | 35.6 | 23.3 | 10.2 | 72.6 |

| 10-OH-9-anthrol | 23.8 | 14.8 | 30.1 | 20.1 | 10.6 | 69.4 |

| 10-OH-9-anthroxyl | 3.1 | –8.9 | 40.1 | –6.4 | 9.1 | 42.9 |

In (k)cal mol–1 (K–1) at T = 298 K. The CBS-QB3 computed ΔfH0(3O2) = −0.83 kcal mol–1 and BDE(H–O2•) = 49.3 kcal mol–1. The ΔG⧧ and ΔS⧧ data are corrected for the rotational symmetry numbers σ. All thermodynamic quantities refer to the standard state of 1 atm. To convert (for A + B → C, Δn = −1) to the standard state of 1 M at 298 K, ΔG1M = ΔG1atm – 1.89, ΔH1M = ΔH1atm – 0.59, ΔS1M = ΔS1atm – 8.34.

The overall reaction enthalpy toward the non-hydrogen-bonded products.

The intermolecular hydrogen bond enthalpy between the products; details are given in 3.6.

The O–H BDE.

1-Hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidine.

Hydroxylic groups both in the away orientation.

An excellent linear [Bell–Evans–Polanyi (BEP)] correlation between ΔH⧧(6) and ΔRH(6) is observed for closed-shell molecules and radicals (eq 7, Figure S1a; n = 19, r2 = 0.988).22 The range in ΔRH(6) covers about 50 kcal mol–123

| 7 |

Equation 7 pertains to the HAT between two oxygen centers. The enthalpy of activation, ΔH⧧(6) is lower than ΔRH(6), the reaction enthalpy for formation of the non-hydrogen-bonded products.24 The variation in ΔRH(6) is directly related to the O–H BDE(O–H), of the compounds under study (Table 1). The BDE(O–H)s for the arenols decrease when ortho and/or para hydrogens are replaced by electron-donating substituents (CH3, OH) or by extending the aromatic system (phenol vs 9-anthrol).12,25 It should be noted that eq 7 is only applicable when additional (neighboring) lone pair interactions in the TS can be ruled out.26 The intermolecular hydrogen bond enthalpy, ΔHBH(6), formed between the products shows only a minor fluctuation (see 3.6) and appears to be not correlated with ΔRH(6). In Figures 1 and S2, the optimized TS structures for a family of compounds (arenols and derived aryloxyls) are displayed. The oxygen–hydrogen bond distances in the reactants are almost invariant with 0.9625 ± 0.0015 Å despite the fact that the BDE(O–H)s span a range of about 44 kcal mol–1. In contrast, within the series (phenol to 10-OH-9-anthroxyl), the ArO–H bond length in the TS decreases from 1.3982 to 1.0992 Å with a concomitant increase of the H–O2• bond length from 1.0636 to 1.3410 Å, which is well consistent with the shift from a late to an early TS.

Figure 1.

B3LYP/CBSB7-optimized TS structures for the HAT from 9-anthrol, 10-OH-9-anthrol, and 10-OH-9-anthroxyl by 3O2, showing bond distances (Å), bond angles, and the imaginary frequencies. r(OH)ArOH denotes the O–H bond length in the parent ArOH reactant. Bond length in isolated HO2•, r(H–O2) = 0.9754 Å.

The Arrhenius pre-exponential factor, A, using conventional TS theory, can be derived from the ΔS⧧(6) data in Table 1.11 For example, the gas phase A values at 298 K for phenol and 4-OH-phenoxyl are calculated as 4.2 × 108 and 2.3 × 107 M–1 s–1, respectively, suggesting a tight TS at least in the latter case. This may be associated with the formation of a hydrogen-bonded complex along the reaction coordinate. However, as has been concluded before, the computed entropies for complexes (such as a TS or an intermolecular hydrogen-bonded ensemble) are systemically underestimated, which is related to the erroneous handling of low-lying frequencies. Therefore, the use of ΔG⧧(6) from Table 1 to predict absolute rate constants needs to be handled with some caution.

A typical enthalpy diagram for the HAT from an arenol (AnH2Q) to molecular oxygen is displayed in Figure 2. The lowest-enthalpy pathway gives a hydrogen-bonded complex between the aryloxyl oxygen and the hydroperoxyl radical (ArO•–HΟ2•). Hence, the overall reaction to the separate products involves a two-step mechanism: a HAT with simultaneous formation of an intermolecular hydrogen bond in the TS, followed by the dissociation of the hydrogen-bonded complex. This implies that based on the principle of microscopic reversibility, the disproportionation between an aryloxyl and a hydroperoxyl radical or the HAT with a quinone (the backward steps of eqs 6a and 6b) sets in with the formation of an intermolecular hydrogen-bonded complex. In the gas phase, such an encounter occurs without an enthalpic barrier, that is, ΔH⧧(−6) ≅ 0 kcal mol–1. Therefore, the overall activation enthalpy, ΔH⧧(6), for the formation of the free species equals ΔRH(6), that is, Ea(6) = ΔRH(6) + 2RT.11 In the liquid phase, a diffusional barrier of ΔH⧧(−6) ≤ 2 kcal mol–1 for organic solvents of low viscosity is expected.

Figure 2.

Enthalpy diagrams (kcal mol–1) for the HAT by 3O2 from anthrahydroquinone (AnH2Q) and 10-OH-anthrone (AnOH).

A kinetic study in the liquid phase (benzene, ∼25 atm air) has afforded Ea(6a)s for phenol, 4-MeO-phenol, and 1-naphthol of 35, 27, and 25 kcal mol–1 at 403 K, respectively, in poor agreement with the Ea(6a)s which can be derived from the data of Table 1.27,28 The reported pre-exponential factor for phenol (A = 7.0 × 1012 M–1 s–1) is unexpectedly about 103 times higher than that for the other two arenols. To the best of our knowledge, experimental gas phase kinetic parameters for eq 6a dealing with phenol or any other compound listed in Table 1 are not available in the literature.

The HAT to oxygen with a series of aryloxyl radicals (4-OH-phenoxyl, 4-OH-1-naphthoxyl, and 10-OH-9-anthroxyl radicals) yields a closed-shell compound (a p-quinone) and HO2•. The thermodynamically favored product for the (formally) radical–radical disproportionation constitutes of an intermolecular hydrogen-bonded complex between the oxygen of the quinone and HO2. The ΔHBHs for the (C=O–HO2•) complexes, eq 6b, are quite comparable with those computed for HB in the (ArO•–HO2) ensembles, eq 6a (see 3.6).

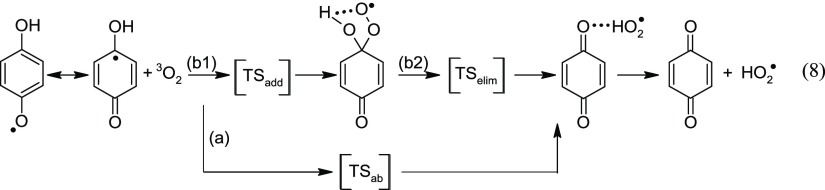

An alternative pathway can be pictured for the formation of p-quinones from the aforementioned aryloxyl radicals. As an example, the fate of the 4-OH-phenoxyl radical has been explored in more detail. The mechanism starting with the 1,4-semiquinone radical and oxygen leading to 1,4-benzoquinone and HO2• can be envisaged as an one- or a two-step process (Scheme 4): (a) by direct HAT (eq 8a) or (b) addition of oxygen to the •C4OH moiety (eq 8b1), followed by an intramolecular elimination of HO2 (eq 8b2). The two pathways have been confirmed by intrinsic reaction coordinate computations (see the Supporting Information, p S6). Unfortunately, a TS (TSelim) for the intramolecular elimination of HO2• from the adduct (eq 8b2) could not be located. Numerous optimization attempts (by varying starting geometries and/or optimization conditions) always ended up with TSs reflecting conformational changes in the complexes with 3O2 or HO2 or the HO2• adduct, respectively.

Scheme 4. Two Distinct Pathways Leading to p-Benzoquinone.

The corresponding enthalpy diagram for eq 8 is shown in Figure 3. The computations reveal that the addition of oxygen to the •C4OH moiety is, rather surprisingly, an activated process with ΔH⧧(8b1) of 7.3 kcal mol–1 [ΔRH(8b1) = −0.1 kcal mol–1]. For comparison, the para-addition of oxygen to the phenoxyl radical (•C4H moiety) requires an ΔHadd⧧ of 7.8 kcal mol–1 (ΔRHadd = −1.8 kcal mol–1).29−31 In contrast, the experimentally determined rate constants for the addition of oxygen to (resonance stabilized) carbon-centered radicals in the gas phase are without an activation barrier, that is, ΔHadd ≅ 0 kcal mol–1.32

Figure 3.

Enthalpy diagrams (kcal mol–1; see Table 1) for HAT from 4-OH-phenoxyl, 4-OH-1-naphthoxyl, and 10-OH-9-anthroxyl by 3O2 yielding 1,4-benzoquinone, 1,4-naphthoquinone, and 9,10-anthraquinone, respectively; overall reaction enthalpies in italics. The ΔaddH⧧ for 10-OH-9-anthroxyl is estimated (±1 kcal mol–1), see text. The bond lengths (in Å) for the intra-HB in the three peroxyl radicals are as follows: r(C–OO): 1.6100, 1.6319, 1.6999; r(OO–HO): 1.8862, 1.8315, 1.6920; r(O–H): 0.9797, 0.9822, 0.9945; the dihedral angles (OOCOH) are 24.09, 20.25, 0.0°.

Stronger peroxyl bonds are formed with the cyclohexadienyl (para-addition) and allyl radicals, and lower activation enthalpies are predicted (ΔHadd⧧ = 3.3 and 2.4, ΔRHadd = −11.033 and −19.134 kcal mol–1, respectively) (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. Pathways (in kcal mol–1) for Cyclohexadienyl and Allyl Radicals with 3O2.

The TS for C–OO bond formation with a nonresonance stabilized radical, such as methyl, could not be located at this level of theory, meaning ΔHadd⧧ ≈ 0 kcal mol–1 (ΔRHadd = −33.1 kcal mol–135). These computational findings indicate, in a qualitative sense, a BEP-type relationship between ΔHadd and ΔRHadd for the addition of oxygen to a carbon-centered radical. The ΔRHadds for the addition of oxygen to carbon-centered radicals by the theory and by the experiment are in good agreement, but that does not hold for the related activation enthalpies. More work is required to resolve this discrepancy.

The overall reaction enthalpy for eq 8 to the non-hydrogen bonded products amounts to 8.0 kcal mol–1 (Table 1) which is in accordance with ΔRH(8) = 9.2 ± 1.0 kcal mol–1 derived from a compilation of experimental and computed thermodynamic data (see the Supporting Information, p. S7). The reverse reaction, 1,4-C6H4O2 + HO2•, is without an enthalpic barrier, as outlined above. Therefore, irrespective of the mechanism, the overall Ea(8) obtained by theory measures in the gas phase 9.2 kcal mol–1 (= ΔRH(8) + 2RT) at 298 K. In the liquid phase, including a diffusional barrier, a Ea(8) ≅ 11 kcal mol–1 is proposed. A rate constant, k(8), of ca. 43 M–1 s–1 is now calculated using an estimated pre-exponential factor of A(8) = 5 × 109 M–1 s–1 for a bimolecular pathway. The inhibition by 1,4-hydroquinone (a natural occurring antioxidant) of styrene autoxidation has been studied, affording a k(8) = 2.7 × 102 M–1 s–1 for the 1,4-semiquinone radical (chlorobenzene, T = 323 K).36 Extrapolation to 298 K gives a k(8) of ca. 80 M–1 s–1, in excellent agreement with the computational results. Such a low rate constant implies that eq 8 may only be of some importance at high oxygen concentrations. At low [O2], the 4-OH-phenoxyl radicals will be involved in chain termination reactions (e.g., trapping peroxyl radicals). At high [3O2], the generated hydroperoxyl radical by eq 8 starts to contribute to the chain propagation, making 1,4-hydroquinone a less effective chain-breaking antioxidant. A laser flash photolysis study on the HAT from the 2,5-di-tert-butyl-1,4-semiquinone radical to oxygen, eq 9, has yielded a k(9) of (1.3 ± 0.5) × 106 M–1 s–1 (chlorobenzene, T = 298 K).37 In the same work, a k(9) of (2.4 ± 0.4) × 106 M–1 s–1 has been reported, based on the inhibition of styrene autoxidation by 2,5-di-tert-butyl-1,4-hydroquinone (chlorobenzene, T = 303 K).37 Our CBS-QB3 computations (with the tert-butyl group modeled by methyl, which is assumed to have only a marginal effect on the reaction enthalpy) predicts a ΔRH(9) of 6.1 kcal mol–1 (≡ΔRH(6b), see Table 1), 1.9 kcal mol–1 lower than that for the 1,4-semiquinone radical. With Ea(9) ≅ 9 kcal mol–1 (see above), a rate constant in solution of k(9) ≅ 1 × 103 M–1 s–1 (298 K) is obtained, 103 times lower than the experimental values.37 Clearly, more experimental work needs to be done to clarify the disagreement.

|

9 |

The lowest enthalpy pathway for 4-OH-1-naphthoxyl reacting with oxygen involves the direct HAT mechanism. Figure 3 shows that the HAT process is associated with a small negative activation barrier (ΔH⧧(6b) = −1.5 kcal mol–1), while the barrier for addition amounts to 6.4 kcal mol–1. According to the computations, ΔRH(6b) = 1.1 kcal mol–1, leading to Ea(6b) ≅ 4 kcal mol–1 in solution with a concomitant overall rate constant, k(6b), of ca. 6 × 106 M–1 s–1 at 298 K. An experimental k(6b) in a mixture of toluene and 10% (v/v) isopropanol has been reported as 6.2 × 105 M–1 s–1 at 298 K. Hence, computations and experiment are in reasonable agreement.38

The computed BDE(O–H) in 4-OH-1-naphthol (78.2 kcal mol–1) is comparable with the BDE(O–H) of 77.1 kcal mol–1 for the naturally occurring antioxidant α-tocopherol (vitamin E),1 suggesting that 4-OH-1-naphthol may well be a robust radical chain-breaking compound. However, the facile generation of HO2• from the intermediate aroxyl radical greatly diminishes the inhibition properties.

In Figure 3, the enthalpy diagram is displayed for the various pathways concerning the 10-OH-9-anthroxyl radical + 3O2 interaction. The TSab geometry for hydrogen abstraction (Figure 1, right) is similar to that for the almost thermoneutral reaction of 4-OH-1-naphthoxyl, but the barrier is significantly more negative [ΔH⧧(6a) = −8.9 kcal mol–1]. Thus, the direct H-transfer appears to be entropy-controlled [ΔG⧧(6a) = 3.1 kcal mol–1].39 In this case, the TS for 3O2 addition (TSadd) could not be located. A linear correlation predicts a ΔHadd⧧ of around 5 ± 1 kcal mol–1.40 Therefore, the addition of oxygen is likely to be insignificant with regard to product formation. The direct HAT reaction is, in contrast to the other two aryloxyl radicals, exothermic by −6.4 kcal mol–1 (see Figure 3). Accepting a linear BEP-type correlation for these reactions, the rate constant for the formation of anthraquinone from the 10-OH-9-anthroxyl radical in a non-HB solvent is clearly close to the diffusion-controlled limit, that is, k(6b) = k(3) ≥ 109 M–1 s–1 at 298 K, in accordance with the experiment.38

3.2. CH + 3O2

The thermodynamic parameters for the HAT between C–H and oxygen, eqs 10a and 10b, involving closed-shell molecules (tautomers of arenols, methylaromatics, and their tautomers), derived radicals, and various auxiliary compounds/radicals have been computed by CBS-QB3. Table 2 summarizes the results, including the activation parameters, ΔG⧧(10), ΔH⧧(10), ΔS⧧(10), the overall reaction enthalpy ΔRH(10), the intermolecular hydrogen bond enthalpy ΔHBH(10) between the product species, and the related C–H BDE.11 Similar to what has been found for •R/ROH–3O2 interactions (see 3.1), prereaction triplet state hydrogen-bonded complexes of the non-radical educts with 3O2 (RCH–3O2) are weak (ΔHBH = −0.84 ± 0.60 kcal mol–1) for closed-shell compounds. Details are presented in Table S3 of the Supporting Information. Further elaborations concerning these species are beyond the scope of this paper.

| 10a |

| 10b |

Table 2. CBS-QB3-Calculated RRD Activation Parameters for HAT Reactions (eqs 10a and 10b)a.

| compound | ΔG⧧(10) | ΔH⧧(10) | –ΔS⧧(10) | ΔRH(10)b | –ΔHBH(10)c | BDEd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ethyl | 24.4 | 14.4 | 33.5 | –13.9 | 3.7 | 35.4 |

| 1-hydroxy-ethyl, s-trans | 21.0 | 11.8 | 30.7 | –12.4 | 6.9 | 36.8 |

| vinyl | 23.6 | 14.1 | 31.9 | –13.0 | 4.1 | 36.3 |

| propene | 47.2 | 39.9 | 24.7 | 37.9 | 3.4 | 87.2 |

| allyl | 31.6 | 21.1 | 35.0 | 8.2 | 3.5 | 57.5 |

| formyl | 9.1 | –0.4 | 31.8 | –33.8 | 2.6 | 15.6 |

| iminyl | 13.2 | 4.9 | 28.0 | –31.1 | 6.2 | 18.2 |

| methoxyl | 16.1 | 5.9 | 34.2 | –28.8 | 7.5 | 20.5 |

| dimethylether | 48.7 | 41.6 | 23.6 | 47.7 | 5.9 | 97.0 |

| pentadienyl | 36.5 | 26.3 | 34.2 | 16.0 | 4.0 | 65.3 |

| cyclopentadiene | 43.0 | 34.4 | 28.8 | 32.9 | 4.5 | 82.1 |

| 1,4-cyclohexadiene | 35.5 | 27.9 | 25.6 | 25.0 | 5.5 | 74.4 |

| cyclohexadienyl | 14.0 | 3.8 | 34.1 | –26.6 | 4.6 | 22.7 |

| 4-OH-cyclohexadienyl | 12.9 | 1.3 | 38.9 | –26.9 | 7.4 | 22.6 |

| t-toluene | 32.1 | 23.4 | 29.1 | 12.1 | 4.2 | 61.4 |

| toluene | 47.1 | 38.8 | 27.6 | 41.3 | 4.4 | 90.6 |

| t-1-Me-naphthalene | 35.5 | 26.0 | 31.8 | 18.4 | 4.7 | 67.7 |

| 1-Me-naphthalene | 48.3 | 40.3 | 26.7 | 41.0 | 4.8 | 90.2 |

| t-9-Me-anthracene | 38.0 | 30.1 | 26.5 | 27.4 | 4.5 | 76.6 |

| 9-Me-anthracene | 46.7 | 38.5 | 27.7 | 36.0 | 5.3 | 85.3 |

| t-phenol | 36.5 | 28.2 | 27.8 | 20.1 | 2.7 | 69.4 |

| 4-OH-t-phenol | 33.9 | 24.1 | 32.6 | 10.8 | 6.3 | 60.0 |

| 2,5-di-Me-4-OH-t-phenol | 32.8 | 23.0 | 32.7 | 11.3 | 6.3 | 60.6 |

| t-1-naphthol | 38.7 | 29.9 | 29.7 | 23.8 | 3.6 | 73.1 |

| 4-OH-t-1-naphthol | 36.7 | 26.9 | 32.9 | 15.8 | 6.5 | 65.0 |

| anthrone | 39.9 | 31.3 | 28.6 | 27.1 | 4.3 | 76.4 |

| 10-OH-anthrone | 37.4 | 27.5 | 33.0 | 21.5 | 7.1 | 70.7 |

In parallel with the O–H system discussed above, the plot of ΔH⧧(10) versus ΔRH(10) (Figure S4a) shows an excellent BEP correlation (n = 27, r2 = 0.981) following eq 11(41)

| 11 |

This equation pertains to the HAT from carbon to oxygen, with a ΔRH(10) range spanning more than 80 kcal mol–1. A typical enthalpy diagram for the HAT from C–H (10-OH-anthrone) to oxygen is displayed in Figure 2. In contrast to the HAT from COH to oxygen, ΔH⧧(10) > ΔRH(10), with toluene as the only exception.

The intermolecular hydrogen bond enthalpies, ΔHBH(10), between the products, that is, radical R• or compound R(−H2), and the hydroperoxyl radical, HO2•, are in the range of −3 to −7 kcal mol–1. The formation of the HB product complex does not occur simultaneously with the transfer of a hydrogen atom in the TS as is the case with COH compounds (eq 6).

In Figures 4 and S5, the TS structures for selected compounds (such as the tautomers of arenols) are displayed. The elongation of the C–H bond in the TS for the formyl radical is only ca. 3% (an exothermic reaction) with ΔRH(10b) (=–33.8 kcal mol–1) while with oxanthrone (endothermic by 21.5 kcal mol–1), the C–H bond length increases by ca. 25%.

Figure 4.

B3LYP/CBSB7-optimized TS structures for HAT from t-phenol, t-4-OH-phenol, and 10-OH-9-anthrone (AnOH) by 3O2, showing bond distances (Å), bond angles, and the imaginary frequencies. r(CH)tArOH denotes the C–H bond length in the parent tautomer. Bond length in isolated HΟ2•, r(H–O2) = 0.9754 Å.

The number of kinetic studies dealing with the HAT from CH to oxygen from closed-shell molecules (all endothermic reactions) is rather limited. An experimental activation enthalpy, Ea,exp, of 39.0 ± 1.4 kcal mol–1 for the propene + 3O2 reaction in the gas phase (700–800 K) has been reported, which is in reasonable agreement with the computed Ea(10a) of 41.1 kcal mol–1 (298 K, Table 2).42 However, an evaluation of all available gas-phase data has resulted in a preferred Ea,exp of 35.7 kcal mol–1 (600–1500 K).43 The agreement for toluene + 3O2 is less satisfying, with a recommended gas phase Ea,exp of 44.9 kcal mol–1 (500–2000 K)43 (later remeasured as 46.0 kcal mol–1),44 while CBS-QB3 predicts Ea(10a) = 40.0 kcal mol–1 (298 K). The Ea,exp of 32 kcal mol–1 derived from liquid-phase experiments with toluene is incompatible with any data.28 The Ea(10b) of 0.8 kcal mol–1 (298 K) for the formyl radical (an exothermic reaction) is in line with the experiment.32

The reactivity of carbon-centered radicals toward oxygen has been examined extensively in the gas32 and in the liquid phase.4 The addition of oxygen, leading to a peroxyl intermediate, is the predominant reaction channel. Studies dealing with C6H7• + 3O2 ⇌ products in solution have yielded kexps of (1.2 ± 0.4) × 109 M–1 s–1 (in cyclohexane45) and 1.6 × 109 M–1 s–1 (in benzene46) at 298 K, hence, diffusion-controlled rate constants. They relate exclusively to the ortho and para addition route (see Scheme 5), yielding the corresponding C6H7OO• radicals.33,45,47 Conversely, a gas phase study has yielded a kexp = 3.1 × 107 M–1 s–1 at 298 K.48 The apparent discrepancy between the liquid and gas phase kexps is most likely due to a change in mechanism.45 In the gas phase, the oxygen addition is (partially) reversible under the experimental conditions (e.g., at low oxygen concentration). This means that the HAT pathway toward benzene and HO2 remains as the only exit channel.45 The reversibility is associated with the weak incipient peroxyl bond in C6H7OO•. The computed BDE(C–OO)s (at 1 M), 11.9 (ortho), and 10.8 (para) kcal mol–1 in cyclohexane49 are in good agreement with the experimental global value of 12 ± 1 kcal mol–1 measured in isooctane.33 According to the CBS-QB3 calculations in cyclohexane, the Eas for ortho and para addition amount to 4.6 and 3.4 kcal mol–1, respectively, next to an Ea(10b) of 5.1 kcal mol–1 for the HAT, suggesting a global rate constant to be much lower than the experimental ones in solution. With ΔG⧧s for the three reaction channels, an addition/abstraction ratio in the gas phase of 10 is calculated, increasing to around 20 in cyclohexane. Thus, perhaps fortuitously, the selectivity (in solution) is in agreement with the experimental data.49 As a consequence of the microscopic reversibility, the relationship between ΔH⧧(−10) and ΔRH(−10) [=−ΔRH(10)] for disproportionation between two radical species (R• + RH2• ⇌ RH + RH) can now be presented by eq 12

| 12 |

It is a general belief (dogma) that in the gas phase, the hydrogen atom shuttle is without an enthalpic barrier, whereas in solution, the rates are dictated by the temperature-dependent diffusion/viscosity. However, eq 12 evidently demonstrates that this is not the case. For the hypothetical thermoneutral radical disproportionation, an activation barrier as high as 18 kcal mol–1 can be expected.13

The termination step in an autoxidation sequence involves radical–radical recombination and/or disproportionation reactions. With HO2• and ArO• as the reactive species, the latter reaction may occur through formation of a hydrogen-bonded complex or by a direct HAT (Figure 2). The disproportionation of 10-OH-9-anthroxyl with HO2 results in AnH2Q and oxygen and is without an activation barrier (ΔH⧧ ≅ 0, ΔRH = −20.1 kcal mol–1) (see Figure 2). In contrast, the HAT yielding AnOH is much slower with ΔH⧧ = 6.0 and ΔRH = −21.5 kcal mol–1.

3.3. COH/CH + HO2•

The CBS-QB3-computed thermokinetic parameters for the O–H HAT by HO2• with series of arenols and aryloxyls radicals (eqs 13a and 13b) are compiled in Table 3.11 The optimized TS structures are shown in Figures 5 and S6. The data refer to the lowest-energy species.

| 13a |

| 13b |

Table 3. CBS-QB3-Calculated Activation Parameters for the HAT Reaction (eqs 13a and 13b)a.

| compound | ΔG⧧(13) | ΔH⧧(13) | –ΔS⧧(13) | –ΔRH(13)b | –ΔHBHed(13)c | –ΔHBH(13)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| phenol | 19.3 | 9.1 | 34.1 | 0.7 | 7.4 | 7.7 |

| phenole | 20.7 | 10.6 | 33.9 | 1.5 | 5.8 | 5.9 |

| phenolf | 22.8 | 12.8 | 33.6 | 2.4 | 4.3 | 3.9 |

| phenolg | 21.1 | 8.2 | 43.2 | –2.3 | 5.6h | 8.6 |

| 4-OH-phenol | 16.3 | 6.5 | 32.9 | 5.0 | 7.3 | 8.2 |

| 4-OH-phenoxyl | 17.0 | 5.1 | 40.1 | 30.5 | 6.3 | 8.2 |

| 4-MeO-phenol | 16.2 | 6.1 | 33.8 | 5.3 | 7.6 | 8.3 |

| 4-Cl-phenol | 19.0 | 8.9 | 33.9 | 1.7 | 7.1 | 7.1 |

| 1-naphthol | 26.6 | 16.9 | 32.7 | 5.6 | 7.3 | 8.0 |

| 4-OH-1-naphtholi | 20.5 | 10.6 | 33.2 | 9.5 | 7.6 | 8.6 |

| 4-OH-1-naphthoxyl | 10.4 | –1.8 | 40.8 | 37.3 | 6.5 | 7.0 |

| 9-anthrol | 21.7 | 10.4 | 38.1 | 15.2 | 7.9 | 7.6 |

| 10-OH-9-anthrol | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 18.4 | 8.1 | 7.2 |

| 10-OH-9-anthroxyl | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 44.8 | 7.1 | 6.9 |

See footnote a, Table 1; n.a.: no stable TS structure found. The computed ΔfH0(HO2•) = 2.90, BDE(HO2–H) = 87.7, and BDE((CH3)3COO–H) = 84.7 kcal mol–1.

The overall reaction enthalpy, ΔRH, without HB in reactants or products.

ΔHBHed, the intermolecular hydrogen bond enthalpy for the educt complex (ROH as the HBA), details are given in Table S7.1.

The intermolecular hydrogen bond enthalpy for the product complex (RO• as the HBA), details are given in Table S7.2.

(SMD)CBS-QB3: solvent cyclohexane.

(SMD)CBS-QB3: solvent water.

With (CH3)3COO• as the H atom abstracting peroxyl radical.

Refers to ROH as the HBD.

Hydroxylic groups both in the away orientation.

Figure 5.

B3LYP/CBSB7-optimized TS structures for HAT from phenol, 4-OH-phenol, and 4-OH-phenoxyl by HO2•, showing bond distances (Å), bond angles, and the imaginary frequencies, d(HOOH) denotes the dihedral angle of the HOOH fragment. The r(O–H) bond lengths in the parent ArOHs are presented in Figure S2.

The ΔRH(13) [=BDE(RO–H) – BDE(HOO–H)], without hydrogen-bonding in reactants or products, ranges from −0.65 (phenol) to −18.4 kcal mol–1 (AnH2Q). Table 3 shows that an (acceptable) BEP relationship between ΔH⧧(13) and ΔRH(13) is lacking. For example, the ΔH⧧(13a)s for phenol and 9-anthrol are calculated as 9.1 and 10.4 kcal mol–1, respectively, while the corresponding ΔRH(13a)s toward the non-hydrogen-bonded products are −0.7 and −15.2 kcal mol–1, respectively. However, the TS structures for the phenol/9-anthrol HAT differ clearly, in the O–H–OOH bond lengths (Figure S6). The r(O–H) decreases from 1.1539 to 1.0504 while the r(H–OOH) increases from 1.2193 and 1.4119 (in Å), in accordance with an earlier TS in the case of 9-anthrol. For the disproportionation reaction with the 4-OH-phenoxyl and 4-OH-naphthoxyl radicals, the large exothermicity suggest an early TS, but this is not reflected in the R(O–H) but rather in the dihedral angle of HOOH. There is an overwhelming amount of experimental kinetic information dealing with the HAT by peroxyl radicals from arenols (phenolic antioxidants). It is well established that the HAT rate with, for example, alkyl-peroxyls increases with a decreasing BDE(O–H).3,4 The reason for this discrepancy between the theory and experiment is not entirely clear. It seems reasonable to attribute the larger scatter of the data, compared to the O2 system, to the possibility to form additional HB (donor) interactions and/or adopting additional conformeric arrangements in the educt [ROH–HO2•] and in the product [RO•–HO2H] complexes, as well as in the TS. In fact, for most of the compounds in Table 3, more than one stable arrangement of the educt/product complex and/or the TS was found. Most likely, the HAT and the formation of the hydrogen bond occur concerted.

A literature survey learns that the computational outcome for the HAT by HO2• from phenol depends strongly on the applied level of theory (see Table S4). For this elementary reaction, the computed ΔH⧧(13a) ranges from 1.5 to 13 kcal mol–1. To the best of our knowledge, an experimental gas-phase study on this reaction has never been reported.

Additionally, we explored the thermodynamic parameters for the HAT (C–H) by HO2• with some prototype closed-shell compounds (eq 14).

| 14 |

The results, together with some data from the literature, are presented in Table S5. A reasonable BEP correlation (n = 12, r2 = 0.957), eq 15, is found (see Figure S7).

| 15 |

However, the general outcome is inconclusive. For example, the calculated ΔH⧧(14) of 5.4 kcal mol–1 for RH = 1,4-cyclohexadiene suggests a much faster reaction compared to the experiment (see 3.5). Moreover, when an adjacent oxygen is present, that is, CH(OH), the linear correlation between ΔH⧧(14) and ΔRH(14) is not obeyed by all conformational arrangements of educts and TSs (compare 4-OH-t-phenol and 10-OH-anthrone, Figure S7). Also, the radical species (see Table S5) exhibit a stronger deviation from linearity. Clearly, more efforts are required to predict accurately by theory the ΔH⧧s when dealing with HO2• as the hydrogen abstracting species.

3.4. Anthrahydroquinone Versus 10-OH-Anthrone: Solvent Effect

The anthraquinone process is carried out in the liquid phase (commonly referred to as the “working solution”) at around 323 K. The medium consists of, for example, a mixture of alkylaromatics and long-chain alcohols to accommodate the difference in solubility of the reactants and the products.8 The thermodynamic parameters for tautomerization (AnH2Q ⇌ AnOH) are calculated as follows: ΔtG = −1.52 kcal mol–1, ΔtH = −1.35 kcal mol–1, and ΔtS = 0.57 cal mol–1 K–1, with the OH in the s-trans orientation as the lowest-enthalpy keto conformer. This leads to an AnOH/AnH2Q ratio (Kt) of 13.0 in the gas phase and inert solvents at 298 K (ca. 11 at 323 K). By ignoring the small difference in entropy between the two species, the keto–enol ratio for any arenol can be derived using ΔtG ≅ ΔtH = BDE(O–H)enol – BDE(C–H)keto (see Tables 1 and 2). The computations on a similar equilibrium, 9-anthrol ⇌ anthrone, have yielded a Kt of 95.6 (298 K), in satisfying agreement with the experiment.12 The difference in the tautomeric ratios between AnH2Q and 9-anthrol can be rationalized by considering the related BDE(O–H)s and BDE(C10–H)s (see Tables 1 and 2). A more pronounced decrease in the BDE(C10–H) in AnOH occurs because of the replacement of the C10H moiety by the radical-stabilizing C10OH.

Experimentally, it has been found that the anthrone/9-anthrol ratio in solution depends strongly on the applied solvent. For example, the ratio reduces from ca. 500 (isooctane)50 to 6.6 (ethanol)51 to about 0.3 [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)]52 at 298 K. The reason is not the change of the bulk solvent properties (i.e., the polarity) but rather the formation of 1:1 intermolecular hydrogen-bonded complexes between the tautomers (solutes) and the solvent.12 The ratio is therefore determined by the hydrogen bond-accepting (HBA) and/or a hydrogen bond-donating (HBD) abilities of the species involved. The strong hydrogen bond between the S=O (DMSO) moiety (acceptor) and the arenolic OH (donor) ensures that 9-anthrol is present in excess in this solvent.

Quantitative data of the solvent effect on the AnOH/AnH2Q ratio are scarce. In 1911, Meyer reported that AnOH did not tautomerize, even after prolonged heating in solvents such as CHCl3, benzene, or ethanol. Starting with either AnOH or AnH2Q, dissolved in ethanol and in the presence of a small amount of HCl, a Kt ≅ 0.03 at 298 K could be derived (after an equilibration time of two days).53 Conversely, in 1969, Sterk measured a Kt of about 6 in neat 1-butanol at 313 K. The range in Kt (ca. 2 to 19) employing various solvents, such as CHCl3, pyridine, and DMSO, is rather limited.54 According to a study by Bredereck et al., Kt equals 0.13 (pH = 9.4, 298 K) in ethanol/water (50/50, v/v).55 The noncatalyzed tautomerization is a slow process, and the presence of an acid or base is required to ensure a fully equilibrated mixture within the time frame of the experiment. For the noncatalyzed tautomerization of AnOH to AnH2Q in ethanol (endothermic by only 1.4 kcal mol–1), a rate constant of 3 × 10–6 s–1 has been reported, underscoring the sluggishness of the equilibration. The presence of 0.1 M HCl results in a hundred fold rate acceleration.56

The HBD (acidity) and the HBA (basicity) abilities for an extensive range of compounds have been parametrized by the α2H and the β2 descriptor, respectively, ranging from 0 to 1.57,58 In most cases, these constants have been determined under dilute conditions and in inert solvents. The KHB for the formation of a 1:1 intermolecular hydrogen bonded complex between a HBD and a HBA is given by eq 16

| 16 |

Numerous α2H and β2 values are known from experimental studies, and eq 16 allows the calculation of KHB for a large number of donor and acceptor combinations with remarkable precision. According to Scheme 3, the AnOH/AnH2Q ratio in a neat HBA solvent, S, is given by eq 17

| 17 |

with KHB1,1 and KHB1,2 as the equilibrium constants for inter-HB formation with the two arenolic groups in AnH2Q, and KHB2 for the inter-HB formation with the OH in AnOH. Furthermore, [AnH2Q]s = [AnH2Q] + [AnH2Q(S)] + [AnH2Q(S2)] and [AnOH]s = [AnOH] + [AnOH(S)]. In our study on the solvent effect on the 9-anthrol ⇌ anthrone equilibrium, it has been concluded that with ethanol (an HBA and an HBD) as a solvent, the HBD ability is greatly reduced. The hydroxylic hydrogens in neat ethanol are associated in cyclic oligomers and are not available for HB with the solute, that is, α2H ≅ 0.12 For both arenolic hydroxyls in AnH2Q, α2 = 0.40 has been proposed.59 Combined with α2H = 0.3257 for the COH moiety in AnOH (as for a secondary alcohol) and the β2s58 for the S, eq 17 can be applied to predict the ratio in any HBA solvent. In neat methanol, eq 17 yields a [AnOH]s/[AnH2Q]s ratio of 0.27, in reasonable agreement with the experimental observations. Hence, the percentage of anthracenyl moieties in solution increases from 7 (inert solvent) to 79%, but the total amount of non-HB hydroxyl groups in [AnH2Q]s decreases from 14 to 2.9%. In other HBA solvents, the ratios are calculated as 5.0 (toluene) and 0.02 (DMSO), all at 298 K. It should be noted that at high [AnH2Q]8 and in a poor HB solvent, self-association may occur as well.

We have explored the effect of solvent on Kt on the (SMD)B3LYP/CBSB7 level of theory. In DMSO, Kt is predicted to increase (and not to decrease) from 13 to 77, while in water or ethanol, Kt drops to around 6 (see Table S6). The results reinforce that common continuum solvent models are not adequate for cases where intermolecular HB is determining the equilibrium ratio. Evidently, under the conditions (temperature, working solution) of the anthraquinone process, the AnOH tautomer is still present in excess.

3.5. Anthrahydroquinone Versus 10-OH-Anthrone: Kinetics

The ΔRHs for the HAT by oxygen from AnH2Q and AnOH, yielding the non-hydrogen-bonded products, are 20.1 (eq 6a) and 21.4 (eq 10a) kcal mol–1, respectively. In contrast, the corresponding activation enthalpies are quite different with ΔH⧧(6a) ≈ ΔRH(6a) = 20.1 and ΔH⧧(10a) = 27.5 kcal mol–1 (see Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 2). Consequently, oxygen reacts about 105 times faster with AnH2Q than with AnOH in an inert solvent at 298 K. According to eqs 7 and 11, the intrinsic activation barrier for a hypothetical thermoneutral HAT from an OH moiety is substantially lower than that from a CH moiety. The magnitude of the TS barrier for RX–H–OO (X = O, C) can be associated with the stability of the RX–OO bond. A low BDE reduces the triplet repulsion (because of the three-electron ensemble) in the TS, and consequently, the ΔH⧧ decreases.2−5,60 Indeed, the RO–OO bond is much weaker than the RC–OO bond. Our CBS-QB3-computed activation free energy, ΔG⧧(4a) [=ΔG⧧(6a)], of 22.7 kcal mol–1 for the formation of the hydrogen-bonded complex (10-OH-9-AnO•–HO2•, see Scheme 2) is a far cry from the 12 kcal mol–1 reported by Yoshizawa et al.9,61 In any case, eq 4a is a rather slow reaction which may serve only as a radical initiating step and cannot be regarded as the rate-determining step in the oxidation of AnH2Q.62

At present, a reasonable estimate of the HAT rate constant by HO2• from AnH2Q can only be obtained with the use of (experimental) thermokinetic data from the literature (see 3.3). Several studies in non- or poor HB solvents dealing with the H-transfer by an alkylperoxyl radical from phenol (an almost thermoneutral reaction)63,64 have yielded an average rate constant of (2.6 ± 0.3) × 103 M–1 s–1 at ca. 300 K (Table S4). For the HAT by HO2 from the arenol 2,2,5,7,8-pentamethyl-6-chromanol (a model compound for α-tocopherol, vitamin E), a rate constant of 1.6 × 107 M–1 s–1 (303 K) in CCl4 (β2H ≅ 0) has been reported.66 The corresponding ΔRH has been estimated as −10.5 kcal mol–1.1 When postulating a BEP relationship for the HAT from the hydroxyl group of arenols by HO2, the rate constant for the more exothermic H-transfer with AnH2Q, eq 2, (ΔRH = −18.4 kcal mol–1, see Table 3) can be approximated as k(2) ≥ 109 M–1 s–1 (per OH) in an inert solvent. Hence, eq 2 is an (almost) diffusion-controlled reaction, which may be the reason why CBS-QB3 calculations failed to locate the TS. Hydroxylic hydrogen involved in a linear intermolecular hydrogen bond is not available for HAT (the kinetic solvent effect).67,68 With the use of eq 17, it is calculated that in toluene about 29% of the hydroxyls are non-hydrogen-bonded, leading to an apparent (experimental) rate constant of k(2) ≥ 6 × 108 M–1 s–1 (per molecule).

The overall reaction enthalpy for the HAT by HO2• from the CH(OH) moiety in AnOH (ΔRH = −17.0 kcal mol–1) is 1.4 kcal mol–1 less exothermic compared to the HAT from the OH group in AnH2Q. However, the intrinsic activation barrier for AnOH is expected to be much higher, as outlined above for the HATs with oxygen.69 Indeed, the HAT rate constant for 1,4-cyclohexadiene (1,4-CHD) has been reported as 2.3 × 102 M–1 s–1 (303 K, n-decane)70 with a ΔRH of −10.8 kcal mol–1.71 The latter is almost equal to the ΔRH for the HAT with 2,2,5,7,8-pentamethyl-6-chromanol, but the rate constants vary by a factor of 105. While AnOH is present as the major tautomer, kinetic considerations learn that this compound is not directly involved in the H2O2 synthesis, despite claims to the contrary.72

The AIBN-initiated autoxidation of 1,4-cyclohexadiene (1,4-CHD) affords exclusively benzene and hydroperoxide as the products (303 K, chlorobenzene). The reaction scheme is similar to that given by eqs 2 and 3, with HO2• as the chain-propagating radical. In the 1,4-CHD autoxidation, the only conceivable termination reaction pertains to the disproportionation between two hydroperoxyl radicals (eq 18), with 2k(18) = 1.34 × 109 M–1 s–1 (303 K, n-decane).70

| 18 |

Equation 18 is probably also the only relevant termination step in AnH2Q autoxidation. In a radical chain process, the chain length is determined by the ratio between the propagation and termination rates [that is, k(2)/2k(18)0.5].4 A large value of this ratio indicates that the oxidation products are (solely) determined by the two propagation reactions. The propagation rate constant (eq 2) is about 106 times higher relative to the HAT from 1,4-CHD, thus underscoring that the AnH2Q autoxidation is an extraordinary efficient long chain radical process.

3.6. Intermolecular HB

Tables 1 and 3 reveal that the hydroperoxyl radical (HO2•) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) form strong hydrogen bonds with acceptors such arenols and aryloxyl radicals. In Table S7.1, the thermodynamic parameters and the hydrogen bond distances are presented. For the interaction of HO2 with phenol, three intermolecular hydrogen-bonded complexes (Ia, Ib, and Ic) could be identified (Scheme 6). In conformers Ia and Ib, the reactants are acting as amphoteric species, that is, as a HBD and a HBA. In complex Ic, HO2• behaves as a double HBA and phenol as a double HBD.

Scheme 6. Three Hydrogen-Bonded Complexes of HO2• with Phenol.

Hydrogen bond lengths (Å): (Ia) r1(PhHO–HOO) = 1.8690, r2(PhOH–OOH) = 2.0608; (Ib) r1(PhHO–HOO) = 1.7893, r2(PhH–OOH) = 2.4665; (Ic): r1(PhOH–OOH) = 1.9858, r2(PhH–OHO) = 2.6422. Thermodynamic data in (k)cal (K–1) mol–1 at 298 K and at 1 M standard state.

The lowest-enthalpy complex, Ia, consists of a planar five-membered ring with the phenolic OH group participating in two hydrogen bonds. From the HB bond distances, it can be concluded that the PhHO–HOO bond will be the strongest interaction. The ΔHBHs for Ia and Ib are almost identical. Because of the free O–H vibration in Ib, the ΔHBS is less negative, meaning that Ib is the lowest free energy conformer.

The effect of the solvent (cyclohexane, water) on the HB formation of HO2• with phenol has been explored with the SMD solvation model. The optimized geometries do not change significantly compared to those in the gas phase, and the ΔHBSs remain almost constant (see Table S7.1). However, the ΔHBH increases because of the partial loss of solvation enthalpy of the reactants, implying that the equilibrium constant in solution will be markedly different (lower) compared to the gas phase.

The HB-arrangement I, as depicted in Scheme 7, is the lowest enthalpy conformer for all arenols studied. The ΔHBHs (−6.7 to −7.3 kcal mol–1, see Table S7.1) demonstrate only a minor change when extending the aromatic system and/or replacing a para hydrogen by an OH group.73 The ArHO–HOO bond distance shows no significant alteration, while the ArOH–OOH bonds with 9-anthrol or AnH2Q are clearly elongated: 2.206 Å (AnH2Q) versus 2.0608 Å (phenol). This is the consequence of a lower HBD ability for these compounds.56 The foregoing results suggest that the ΔHBH is largely determined by the acidity (α2H) of HO2. Water and methanol are better HB acceptors compared to phenol with β2Hs of 0.38 and 0.41 versus 0.22, respectively.58 The inter-HB complexes with HO2 render shorter (O–HOO) bond lengths of 1.7661 Å (H2O) and 1.7490 Å (CH3OH) relative to phenol (1.8690 Å). Conversely, phenol is a stronger HBD,57 which leads to an increase of the OH–OOH bond lengths, ranging from 2.0608 (phenol) to 2.2358 Å (CH3OH).

Scheme 7. CBS-QB3-Calculated Lowest-Enthalpy Conformers of Hydrogen-Bonded HO2• Complexes with Arenols (I), Phenoxyl (II), and Naphthoxyl or Anthroxyl (III); Lowest-Enthalpy Conformers of H2O2 Hydrogen Bond Complexes with Phenoxyl (IV) and Naphthoxyl or Anthroxyl (V).

The lowest-enthalpy HB complexes for the interaction of HO2• with aryloxyl radicals are found to be a seven-membered (phenyl, II) or an eight-membered ring (naphthyl, anthracenyl, III) ensemble. Considering the hydrogen bond distances, the interaction of C–O• with HO2 (1.69 ± 0.01 Å) is much stronger than that for ArH and •OOH (ca. 2.20 Å). For the series investigated, the ΔHBHs vary only slightly from −9.6 to −11.3 kcal mol–1, and the HBs are 2–3 kcal mol–1 stronger than with the corresponding arenols. It has been proposed that the aryloxyl radical can be regarded as a delocalized carbon-centered radical with the C–O• moiety acting as a carbonyl group, which is a stronger HBA.63 For comparison, the HB parameters have also been calculated for model compounds containing a C=O group (acetaldehyde, acetone, 1,4-benzoquinone, 1,4-naphthoquinone; see Table S7.1). The O–HOO bond lengths are somewhat longer than those in II, with a concomitant decrease in ΔHBH. Hence, the HBA ability of aryloxyl radicals is estimated to be slightly higher than that of acetone, that is, β2H(ArO•) = 0.52.

It is of interest to quantify the α2H for the hydroperoxyl radical using the computational data in order to predict the behavior in a HB environment (solution, troposphere74). It is well known that the computed ΔHBSs are underestimated values, leading to erroneous ΔHBGs (and KHBs). Therefore, eq 16 cannot be used in a straightforward way. An alternative approach is utilizing the difference in the computed ΔHBGs (at 1 M, see Tables S7.1 and Scheme 6) for identical conformations (cancelation of errors) for the equilibria C6H5OH + HO2 ⇌ Ib and C6H5O• + HO2• ⇌ II. In this way, an α2(HO2•) = 0.86 is derived using eq 15 combined with β2(C6H5O•) = 0.52 (see above) and β2H(C6H5OH) = 0.22.57 The hydroperoxyl radical is a strong HBD, which is not unexpected in view of its low pKa value (4.88).59 Only one study has reported an estimated α2(HO2•) of about 0.87, based on the analysis of the kinetic solvent effect on the HO2 + HO2• self-reaction.75

Finally, the HB of H2O2 (pKa = 11.75) with aryloxyl radicals (Tables 3 and S7.2) consists of seven-membered (phenyl, IV) or eight-membered (naphthyl, anthracenyl, V) ring ensembles (Scheme 7). The solvent effect on the C6H5O•–H2O2 HB complex is similar to that observed for the C6H5OH–HO2• ensemble. The ΔHBHs are again almost invariant, ranging from −7.0 to −7.8 kcal mol–1. With the computed ΔHBGs (see above) for the equilibria C6H5O• + HO2 ⇌ II and C6H5O• + HO2H ⇌ IV, an α2H(HO2H) = 0.51 is obtained, quite similar to the HBD ability of 2,2,2-trichloroethanol (pKa = 12.02, α2 = 0.50).57

4. Conclusions

The kinetic parameters for the HAT by oxygen, 3O2, from a broad range of arenols (ArOH) and aryloxyl (ArO•) radicals has been quantified by means of CBS-QB3 calculations. The results show an excellent BEP correlation between the enthalpy of activation, ΔH⧧ (TS: O–H–O) and the overall reaction enthalpy, ΔRH. A similar excellent BEP relationship has been obtained for the HAT from the tautomeric forms of the arenols and auxiliary compounds (TS: C–H–O). However, the HATs from the OH and the CH moieties follow different pathways. The lowest-energy route for ArOH compounds (closed-shell species and radicals) involves a simultaneous transfer of the H atom and the formation of a strong intermolecular hydrogen bond (HB) between the product radicals ArO• and HO2•, hence, ΔH⧧ < ΔRH. Conversely, ΔH⧧ > ΔRH holds for the HAT from CH, associated with a high intrinsic barrier. Because the number of experimental studies is quite limited, the computational findings may be of importance to predict the behavior of similar compounds under a variety of reaction conditions. With the hydroperoxyl radical, HO2, as the HAT species, a reasonable BEP relationship could not be observed, while the predicted rate constants are quite at variance with the experiment. Equipped with the kinetic insights acquired from this study, the purportedly unknown mechanism for the (industrial) production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) from the autoxidation of anthrahydroquinone (AnH2Q) has been debunked. The analysis shows that the two propagation steps in the radical chain sequence (eqs 2 and 3) are both at or near the diffusion-controlled limit. Oxanthrone (AnOH) is the thermodynamically more stable tautomer of AnH2Q, and the ratio depends on the HB properties of the solvent. Furthermore, a HB donating ability, “the acidity”, for the hydroperoxyl radical of α2H(HO2) = 0.86 has been derived from computational and empirical data.

Appendix

From a 2006 peer-reviewed paper entitled Hydrogen Peroxide Synthesis: An Outlook beyond the Anthraquinone Process, it can be learned that the oxidation of anthrahydroquinone (AnH2Q) to H2O2 ... occurs by means of a well-documented free-radical chain mechanism.76 Surprisingly, Scheme 3 presented in ref (76) does not refer to the autoxidation of AnH2Q, as presented by eqs 2 and 3 but rather to that of 9,10-dihydroxy-9,10-dihydroanthracene (AnH4Q).77,78 Obviously unaware of the structural flaw, the authors (were forced to) proposed a more complex mechanism because an overall conversion of AnH4Q to the final products anthraquinone (AnQ) and H2O2 would stoichiometrically require two molecules of 3O2. The authors suggested a radical chain mechanism (see Scheme 8) that starts with a nonspecified initiation reaction whereby ketyl radical A is formed. The propagation involves the addition of oxygen to A (eq 19a) yielding a peroxyl radical B, followed by a HAT (eq 20) from AnH4Q leading to an intermediate hydroperoxide (C), and regenerates A. The thermal decomposition of C affords oxanthrone, AnOH, and H2O2 (eq 21). Termination reactions have not been considered. The proposed mechanism is highly improbable. It is well known that ketyl radicals, for example, benzophenone ketyl, react with oxygen at the diffusion-controlled limit to yield ketone according to an addition/elimination mechanism (eqs 19a,b).38 The proposed HAT by the peroxyl radical B (eq 20) will be a rather slow (CH to O) bimolecular reaction (this work). Consequently, the major pathway for ketyl A follows eqs 19a and 19b yielding 10-OH-anthrone (AnOH) and HO2•. Alternatively, a direct HAT by oxygen (eqs 22a and 22b) from A can be envisaged. In that case, the H-transfer from OH to 3O2 (eq 22a) to give AnOH will be the preferred route (this work).

Scheme 8. Mechanism for the Anthraquinone H2O2 Process as Proposed in ref (76), with the CBS-QB3-Calculated Reaction Enthalpies in kcal mol–1 (This Work).

The lowest-enthalpy conformer of AnH4Q consists of the two hydroxyls in the s-trans orientation. BDE(C–H) in AnH4Q is 77.8 kcal mol–1. The bond lengths (in Å) for the intra-HB in B are as follows: r(C–OO): 1.6519; r(OO–HO), 1.7195; r(O–H): 0.9898; and the OOCOH dihedral angle is 0.0° (see also Figure 3).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.9b03286.

Two tables of CBS-QB3-computed thermochemical parameters of prereaction 3O2 complexes; five figures pertaining to the BEP correlations for hydrogen atom abstraction by molecular oxygen and HO2•; assessment of the thermodynamics for the reaction of 4-OH-phenoxyl with oxygen; overview of the computed and experimental kinetic parameters for hydrogen abstraction from (4-OH/MeO−) phenol: CBS-QB3 computed thermokinetic parameters for the C–H hydrogen abstraction by HO2 from various compounds; three figures showing selected computed transition structures for the foregoing hydrogen transfer reactions; effect of solvation on the AnH2Q tautomeric equilibrium; thermodynamic parameters and bond distances for the intermolecular HB of HO2• and H2O2 with arenols and auxiliary species; and B3LYP/CBSB7- and CBS-QB3-computed energies and structure coordinates (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Dedication

This paper is dedicated to Keith U. Ingold on the occasion of his 90th birthday.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lucarini M.; Pedulli G. F. Free Radical Intermediates in the Inhibition of the Autoxidation Reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 2106–2119. 10.1039/b901838g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhiya L.; Zipse H. Initiation Chemistries in Hydrocarbon (Aut)Oxidation. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015, 21, 14060–14067. 10.1002/chem.201502384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J. A. In The Chemistry of Free Radicals: Peroxyl Radicals; Alfassi Z. B., Ed.; John Wiley: Chichester, U.K., 1997; pp 283–334. [Google Scholar]

- Denisov E. T.; Afanas’ev I. B.. Oxidation and Antioxidants in Organic Chemistry and Biology; CRC Press: Baco Raton, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Denisov E. T.; Sarkisov O. M.; Likhtenshtein G. I.. Chemical Kinetics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2003; Part 4, p 317. [Google Scholar]

- Goor G.; Glenneberg J.; Jacobi S.. Hydrogen Peroxide. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 7th ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2012; Vol. 18, pp 393–427. [Google Scholar]

- http://www.essentialchemicalindustry.org/chemicals/hydrogen-peroxide.html (accessed August/October 2019).

- From the variety of operating conditions in the industrial oxidation of 2-alkyl-anthrahydroquinone to 2-alkyl-9,10-anthraquinone and hydrogen peroxide, the following characteristic reaction conditions have been selected: (1) temperature: 323 K, (2) air pressure: 5 atm, (3) toluene as a model for the working solution, (4) [AnH2Q]0 = 0.4 M. The oxygen concentration in this solution is estimated as 9.6 × 10–3 M, see:; a Battino R.; Rettich T. R.; Tominaga T. The Solubility of Oxygen and Ozone in Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1983, 12, 163–178. 10.1063/1.555680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; and; b Battino R.; Rettich T. R.; Tominaga T. The Solubility of Nitrogen and Air in Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1984, 13, 563–600. 10.1063/1.555713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimi T.; Kamachi T.; Kato K.; Kato T.; Yoshizawa K. Mechanistic Study on the Production of Hydrogen Peroxide in the Anthraquinone Process. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 4113–4120. 10.1002/ejoc.201100300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamachi T.; Ogata T.; Mori E.; Iura K.; Okuda N.; Nagata M.; Yoshizawa K. Computational Exploration of the Mechanism of the Hydrogenation Step of the Anthraquinone Process for Hydrogen Peroxide Production. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 8748–8754. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b01325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The computed thermodynamic parameters ΔG⧧, ΔH⧧, ΔS⧧, ΔRH, and ΔHBH are all at the standard state of 1 atm. According to the conventional transition state theory (TST), the rate constant at the 1 M standard state for a bimolecular reaction is given by k = (kT/h) × (R′T) × exp(−ΔG⧧/RT). The corresponding Arrhenius parameters are A (M–1 s–1) = (e2kT/h) × (R′T) × exp(ΔS⧧/R) and Ea = ΔH⧧ + 2RT, R′ = 0.082 L atm mol–1 K–1.

- Korth H.-G.; Mulder P. Anthrone and Related Hydroxyarenes: Tautomerization and Hydrogen Bonding. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 7674–7682. 10.1021/jo401243b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth H.-G.; Mulder P. Tautomerization of Some Methylacenes and the Role of Reverse Radical Disproportionation. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 8206–8216. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. The DBH24/08 Database and Its Use to Assess Electronic Structure Model Chemistries for Chemical Reaction Barrier Heights. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5, 808–821. 10.1021/ct800568m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeys M.; Reyniers M.-F.; Marin G. B.; Van Speybroeck V.; Waroquier M. Ab Initio Calculations for Hydrocarbons: Enthalpy of Formation, Transition State Geometry, and Activation Energy for Radical Reactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 9147–9159. 10.1021/jp021706d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saeys M.; Reyniers M.-F.; Van Speybroeck V.; Waroquier M.; Marin G. B. Ab Initio Group Contribution Method for Activation Energies of Hydrogen Abstraction Reactions. ChemPhysChem 2006, 7, 188–199. 10.1002/cphc.200500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan B.; Radom L. Hierarchy of Relative Bond Dissociation Enthalpies and Their Use to Efficiently Compute Accurate Absolute Bond Dissociation Enthalpies for C–H, C–C, and C–F Bonds. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 3666–3675. 10.1021/jp401248r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Frisch M. J.; Ochterski J. W.; Petersson G. A. A Complete Basis Set Model Chemistry. VI. Use of Density Functional Geometries and Frequencies. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 2822–2827. 10.1063/1.477924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Frisch M. J.; Ochterski J. W.; Petersson G. A. A complete basis set model chemistry. VII. Use of the minimum population localization method. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 6532–6542. 10.1063/1.481224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009; see Supporting Information for the full reference.

- Marenich A. V.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell G. A. In Free Radicals; Kochi J. K., Ed.; Wiley: New York, 1973; Vol. 1, p 275. [Google Scholar]

- The related free energies also follow a similarly excellent linear relationship: ΔG⧧(6) = 0.84 × ΔRG(6) + 9.00 (n = 19, r2 = 0.989; Figure S1b).

- On the less advanced B3LYP/CBSB7 level of theory (the geometry optimization + frequency steps of CBS-QB3), markedly lower (3–13 kcal mol–1) ΔH⧧(6)s were obtained compared to the full CBS-QB3 scheme, e.g., 7.0, 9.9, and 9.3 kcal mol–1 lower for phenol, 1-naphthol, and 9-anthrol, respectively. This reflects the (well known) poor performance of B3LYP (and qualitatively similar DFT methods) in establishing transition state energies.14−17

- Pratt D. A.; DiLabio G. A.; Mulder P.; Ingold K. U. Bond Strengths of Toluenes, Anilines, and Phenols: To Hammett or Not. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 334–340. 10.1021/ar010010k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The substituent effect on the BDE(O–H) for arenols is the consequence of the molecule and the radical stabilization or destabilization. The BDE(O–H) reduction in 9-anthrol relative to phenol of 14.5 kcal mol–1 is (almost) exclusively due to the enhanced stabilization in the 9-anthroxyl radical

- CBS-QB3 calculations on 2-ClC6H4OH (non-intraHB) + 3O2 ⇌ 2-ClC6H4O• + HO2• yields ΔH⧧(6a) = 35.6 and ΔRH(6a) = 36.6 kcal mol–1, i.e., ΔH⧧(6a) ≅ ΔRH(6a). In contrast, eq 7 predicts a lower ΔH⧧(6a) of 29.3 kcal mol–1. The ΔHBH(6a) of −10.1 kcal mol–1 between the products appears to have no impact on ΔH⧧(6a). With 4-ClC6H4OH (see Table 1) the ΔH⧧(6a) of 29.4 kcal mol–1 is in full agreement with eq 7 (29.5 kcal mol–1). Additional computations show that the BEP relationship between ΔH⧧ and ΔRH is markedly different when lone pairs in the vicinity are directed to the reaction center (as in, e.g., H2O2, HO2•, 2-ClC6H4OH). A computational study using BB1K and B3LYP methods has yielded ΔH⧧(6a) of 33.3 and 27.2 kcal mol–1, with ΔRH(6a) of 40.6 and 36.4 kcal mol–1, hence ΔH⧧(6a) < ΔRH(6a) see:Altarawneh M.; Dlugogorski B. Z.; Kennedy E. M.; Mackie J. C. Quantum Chemical and Kinetic Study of Formation of 2-Chlorophenoxy Radical from 2-Chlorophenol: Unimolecular Decomposition and Bimolecular Reactions with H, OH, Cl, and O2. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 3680–3692. 10.1021/jp712168n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denisova A. N.; Denisov E. T.; Metelitsa D. I. Oxidation of Phenols and Naphthols by Molecular Oxygen. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR, Div. Chem. Sci. 1969, 18, 1537–1542. 10.1007/bf00906375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denisov E. T.; Denisova L. N. Estimation of the R–H Bond Energy from the Activation Energy for the Reaction RH + O2 → R• + HO2•. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1976, 8, 123–130. 10.1002/kin.550080113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Substituting C4H in phenoxyl by C4OH leads to minor change in ΔHadd. Actually, the ΔHadd of −0.1 kcal mol–1 for 4-OH-phenoxyl is lower than expected since the OH substituent is supposed to weaken the incipient OO–C4OH bond. The reason is the formation of a stabilizing intramolecular hydrogen bond in the peroxyl radical; with ΔHBG and ΔHBH of −2.6 and −3.6 kcal mol–1, respectively. When replacing C4OH by C4OCH3 (intra-HB formation is not possible), the addition of oxygen is endothermic by 2.0 kcal mol–1. According to (SMD)CBS-QB3, the equilibrium constant for intramolecular HB formation reduces from 75.9 (gas phase) to 0.964 (DMSO) due to the loss of solvation enthalpy.

- A computational study at various (five) levels of theory on the para-addition of oxygen to •C4H in phenoxyl shows a range in ΔHadd⧧ of 9.3–20.0 kcal mol–1 and ΔHadd = −0.5–12.1 kcal mol–1, see:McFerrin C. A.; Hall R. W.; Dellinger B. Ab Initio Study of the Formation and Degradation Reactions of Semiquinone and Phenoxyl Radicals. J. Mol. Struct.: Theochem 2008, 848, 16–23. 10.1016/j.theochem.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A computational study at the BB1K/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory has yielded ΔHadd⧧ = 19.3 kcal mol–1 and ΔHadd = 6.4 kcal mol–1 for the para-addition of oxygen to •C4H in phenoxyl, see:Batiha M.; Al-Muhtaseb A. H.; Altarawneh M. Theoretical Study on the Reaction of the Phenoxy Radical with 3O2, OH, and NO2. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2012, 112, 848–857. 10.1002/qua.23074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- https://kinetics.nist.gov (accessed Aug/October 2019).

- Kranenburg M.; Ciriano M. V.; Cherkasov A.; Mulder P. Carbon-Oxygen Bond Dissociation Enthalpies in Peroxyl Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 915–921. 10.1021/jp992404n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; The experimental ΔHadd [= –BDE(C–OO)] for the addition of oxygen to cyclohexadienyl is −12 ± 1.0 kcal mol–1.

- Rissanen M. P.; Amedro D.; Eskola A. J.; Kurten T.; Timonen R. S.. Kinetic (T = 201–298 K) and Equilibrium (T = 320–420 K) Measurements of the C3H5 + O2 ⇌ C3H5O2 Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 3969−3978, and references cited therein. The experimental ΔHadd [= –BDE(C–OO)] for oxygen addition to allyl is −18.0 ± 0.5 kcal mol–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villano S. M.; Huynh L. K.; Carstensen H.-H.; Dean A. M.. High-Pressure Rate Rules for Alkyl + 3O2 Reactions. 1. The Dissociation, Concerted Elimination, and Isomerization Channels of the Alkyl Peroxy Radical. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 13425−13442, and references cited therein. The experimental ΔHadds [= –BDE(C–OO)] for oxygen addition to methyl are −32.7 ± 0.9 and −31.3 ± 1.2 kcal mol–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozdeeva N. N.; Yakushchenko I. K.; Aleksandrov A. L.; Denisov E. T. Mechanism of the Inhibitory Action of Hydroquinone, Crown-Hydroquinone, and Its Complexes with Lithium and Magnesium Salts in Styrene Oxidation. Kinet. Katal. 1991, 32, 1162–1169. . Derived by modelling the oxygen uptake with a complex kinetic scheme. [Google Scholar]

- Valgimigli L.; Amorati R.; Fumo M. G.; DiLabio G. A.; Pedulli G. F.; Ingold K. U.; Pratt D. A. The Unusual Reaction of Semiquinone Radicals with Molecular Oxygen. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 1830–1841. 10.1021/jo7024543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Derived by numerical fitting of the LFP decay traces of the 2,5-di-tert-butyl-1,4-semiquinone radical and of the oxygen uptake in the autoxidation experiments to a complex kinetic scheme comprising five individual reactions (four involving the semiquinone radical)

- Tatikolov A. S. Kinetics of the Interaction of Ketyl and Semiquinone Radicals with Dioxygen. Concerted Electron and Proton Transfer Involving Ketyl and Semiquinone Radicals. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1997, 46, 1082–1088. 10.1007/bf02496202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- See for example:Kapinus E. I.; Rau H. Negative Enthalpies of Activation and Isokinetic Relationships in the Electron Transfer Quenching Reaction of Pd–Tetraphenylporphyrin by Aromatic Nitro Compounds and Quinones. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 5569–5576. 10.1021/jp980171e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- From a linear correlation between the ΔHadd⧧s and ΔRHs of delocalized radicals, including the aroxyls, a ΔHadd = 5 ± 1 kcal mol–1 for the addition reaction of 3O2 to 9-OH-anthroxyl is estimated. The related free energy correlation estimates ΔGadd⧧ = 14 ± 1 kcal mol–1.

- The related free energies also follow a similarly excellent linear relationship: ΔG⧧(10) = 0.49 × ΔRG(10) + 27.91 (n = 27, r2 = 0.981; Figure S4b).

- Stothard N. D.; Walker R. W. Determination of the Arrhenius Parameters for the Initiation Reaction C3H6 + O2 → CH2CHCH2 + HO2. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1991, 87, 241–247. 10.1039/ft9918700241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; An experimental A/M–1 s–1 of 2.0 × 109 is reported

- The recommended Ea,exps are based on an evaluation using a three-parameter fit: k(M–1 s–1) = b × T2.5 × exp(−Ea/RT) (see:Baulch D. L.; Bowman C. T.; Cobos C. J.; Cox R. A.; Just T.; Kerr J. A.; Pilling M. J.; Stocker D.; Troe J.; Tsang W.; Walker R. W.; Warnatz J. Evaluated Kinetic Data for Combustion Modeling: Supplement II. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2005, 34, 757–1397. 10.1063/1.1748524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; )

- Oehlschlaeger M. A.; Davidson D. F.; Hanson R. K. Investigation of the Reaction of Toluene with Molecular Oxygen in Shock-Heated Gases. Combust. Flame 2006, 147, 195–208. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2006.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; The reported Ea,exp of 46.0 kcal mol–1 for toluene + 3O2 in the gas phase is derived from a three-parameter fit of the data (see ref (43)); from a two-parameter fit of the data an Ea,exp = 52.8 kcal mol–1 is obtained with an unexpected A/M–1 s–1 of 1.8 × 1013 (see ref (42))

- Taylor J. W.; Ehlker G.; Carstensen H.-H.; Ruslen L.; Field R. W.; Green W. H. Direct Measurement of the Fast, Reversible Addition of Oxygen to Cyclohexadienyl Radicals in Nonpolar Solvents. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 7193–7203. 10.1021/jp0379547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard B.; Ingold K. U.; Scaiano J. C. Rate Constants for the Reactions of Free Radicals with Oxygen in Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 5095–5099. 10.1021/ja00353a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The rate constant for HO2• elimination from the ortho-peroxyl radical, yielding benzene, has been determined as k ≥ 8 × 105 s–1 in aqueous solution (Scheme 5); see:Pan X.-M.; Schuchmann M. N.; von Sonntag C. Hydroxyl-radical-induced Oxidation of Cyclohexa-1,4-diene by O2 in Aqueous Solution. A Pulse Radiolysis and Product Study. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 1021–1028. 10.1039/p29930001021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The experimental rate constant of 8.4 × 107 exp(−0.6/RT) M–1 s–1 has been derived from a four-point Arrhenius plot. Computations at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory reveals Ea,add = 3.9 kcal mol–1 (position not specified), the TS for the hydrogen abstraction could not be located, i.e., Ea,ab ≈ 0 kcal mol–1 (CBS-QB3, this work: 5.0 kcal mol–1), see:Estupiñán E.; Villenave E.; Raoult S.; Rayez J. C.; Rayez M. T.; Lesclaux R. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Gas-Phase Reaction of the Cyclohexadienyl Radical c-C6H7 with O2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 4840–4845. 10.1039/b308107a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- According to (SMD)CBS-QB3 (all data in kcal mol–1, at 1 atm); BDE(C–OO) in the gas phase: 12.1 (ortho) and 11.0 (para). ΔG⧧(ad)s for the gas phase, cyclohexane are 12.9, 13.7 (ortho), 12.8, 11.8 (para), ΔG⧧(ab)s for the gas phase, cyclohexane are 13.6, 13.6.

- Baba H.; Takemura T. Spectrophotometric Investigations of the Tautomeric Reaction between Anthrone and Anthranol. I. The Keto-Enol Equilibrium. Tetrahedron 1968, 24, 4779–4791. 10.1016/s0040-4020(01)98674-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills S. G.; Beak P. Solvent Effects on Keto-Enol Equilibria: Tests of Quantitative Models. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 1216–1224. 10.1021/jo00208a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham R. J.; Mobli M.; Smith R. J. 1H Chemical Shifts in NMR: Part 19. Carbonyl Anisotropies and Steric Effects in Aromatic Aldehydes and Ketones. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2003, 41, 26–36. 10.1002/mrc.1125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. H. Zur Kenntnis des Anthracens. I. Über Anthranol und Anthrahydrochinon. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1911, 379, 37–78. 10.1002/jlac.19113790104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sterk H. Untersuchungen zur Temperaturabhängigkeit charakteristischer IR- und NMR-Absorptionen, 12. Mitt.: Zur Temperaturabhängigkeit der Transanulartautomerie aromatischer Ketone. Monatsh. Chem. 1969, 100, 916–919. 10.1007/bf00900576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bredereck V. K.; Sommermann E. F. Die reversible Tautomerisierung von 9,10-Anthrahydrochinonen. Tetrahedron Lett. 1966, 7, 5009–5014. 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)90318-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; In ethanol/water (50/50, v/v) the pKa1 and pKa2 for AnH2Q are 8.8 and 13.6, respectively

- Carlson S. A.; Hercules D. M. Photoinduced Luminescence of 9,10-Anthraquinone. Primary Photolysis of 9,10-Dihydroxyanthracene. Anal. Chem. 1973, 45, 1794–1799. 10.1021/ac60333a047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham M. H.; Grellier P. L.; Prior D. V.; Duce P. P.; Morris J. J.; Taylor P. J. Hydrogen Bonding. Part 7. A Scale of Solute Hydrogen-Bond Acidity Based on Log K Values for Complexation in Tetrachloromethane. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1989, 699–711. 10.1039/p29890000699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham M. H.; Grellier P. L.; Prior D. V.; Morris J. J.; Taylor P. J. Hydrogen Bonding. Part 10. A Scale of Solute Hydrogen-Bond Basicity Using Log K Values for Complexation in Tetrachloromethane. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1990, 521–529. 10.1039/p29900000521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- It is well established that a good linear correlation exists between α2H and pKa for a family of compounds, i.e., a lower pKa implies a higher α2. However, that does not hold for 9-anthrol with pKa = 7.8 and α2H = 0.42, to be compared with the properties for phenol (pKa = 9.99, α2 = 0.596). The reason may be the steric congestion in the inter-HB complexes with 9-anthrol due to the adjacent C–H moieties (ref (12)). It seems reasonable to assume that pKas for 9-anthrol and AnH2Q (in water) are about the same as is the case for phenol and 4-MeO-phenol. The latter is slightly less acidic (pKa = 10.27) with a concomitant decrease in α2H to 0.573 (ref (57)). Following this analogy an α2 = 0.40 for AnH2Q is proposed.

- Zavitsas A. A. Energy Barriers to Chemical Reactions. Why, How, and How Much? Non-Arrhenius Behavior in Hydrogen Abstractions by Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 6578–6586. 10.1021/ja973698y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]