Abstract

Context:

The Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) is a clinical tool often used in research and practice to identify athletes presenting high injury-risk biomechanical patterns during a jump-landing task.

Objective:

To systematically review the literature addressing the psychometric properties of the LESS.

Data Sources:

Three electronic databases (PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus) were searched on March 28, 2018, using the term “Landing Error Scoring System.”

Study Selection:

All studies using the LESS as main outcome measure and addressing its reliability, validity against motion capture system, and predictive validity were included. Original English-language studies published in peer-reviewed journals were reviewed. Studies using modified versions of the LESS were excluded.

Study Design:

Systematic literature review.

Level of Evidence:

Level 4.

Data Extraction:

Study design, population, LESS testing procedures, LESS scores, statistical analysis, and main results were extracted from studies using a standardized template.

Results:

Ten studies met inclusion criteria and were appraised using Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies. The overall LESS score demonstrated good-to-excellent intrarater (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC], 0.82-0.99), interrater (ICC, 0.83-0.92), and intersession reliability (ICC, 0.81). The validity of the overall LESS score against 3-dimensional jump-landing biomechanics was good when individuals were divided into 4 quartiles based on LESS scores. The validity of individual LESS items versus 3-dimensional motion capture data was moderate-to-excellent for most of the items addressing key risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury. The predictive value of the LESS for ACL and other noncontact lower-extremity injuries remains uncertain based on the current scientific evidence.

Conclusion:

The LESS is a reliable screening tool. However, further work is needed to improve the LESS validity against motion capture system and confirm its predictive validity for ACL and other noncontact lower-extremity injuries.

Keywords: injury risk, injury prevention, movement screen, sport injury, jump-landing

Increased participation in physical activities increases the likelihood of sustaining sport-related injuries.54 Noncontact mechanisms explain approximately 18% of injuries in game situations and 37% of injuries in practice or training situations.22 Neuromuscular and biomechanical factors are key in the prevention of noncontact injuries, as modifiable through targeted training interventions.17,42

The Landing Error Scoring System (LESS; Appendix Table A1, available in the online version of this article) is a clinical assessment tool40 often used in research to identify individuals at high risk of sustaining noncontact injuries and to quantify changes in neuromuscular and biomechanical performance subsequent to intervention across sports14,15,18 and performance levels.27,49 The LESS has also been used in participants with a history of injury24,30 and after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction2,20 to quantify residual functional impairments and outcomes from rehabilitation.

It is essential that testing methods provide outcomes that are reproducible and valid so that changes in scores reflect meaningful changes in function of individuals and identify individuals with differing abilities. In the LESS, lower scores should reflect a reduction in injury risk and high injury-risk movement patterns. The LESS was previously addressed in critically appraised topics32,44,47 and literature reviews4,7,19,34,48; however, no systematic review has critically appraised and summarized research on its psychometrics properties (reliability and validity). Such a systematic review is warranted to ensure the justified use of the LESS in large-scale screening initiatives, monitoring changes in risk factors, establishing the effects of injury prevention programs, and identifying athletes at high risk of injuries. Therefore, our aim was to systematically review and critically appraise studies addressing the psychometric properties of the LESS.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

Literature review methods and inclusion criteria were specified in advance and registered on PROSPERO (CRD42018107210).

Eligibility Criteria

Studies that used the LESS as a main outcome measure and examined its reliability, validity against motion capture, and predictive validity were included for review regardless of participant, intervention, or study design characteristics. Only original research published in English in peer-reviewed (abstract available) journals were considered. Letters to the editor, symposium publications, conference abstracts, books, expert opinions, critically appraised topics, and literature reviews were excluded. Studies using modified versions of the original LESS protocol (eg, iLESS, real-time LESS, and automated quantification of the LESS) were excluded.23,33,50

Information Sources and Search Strategy

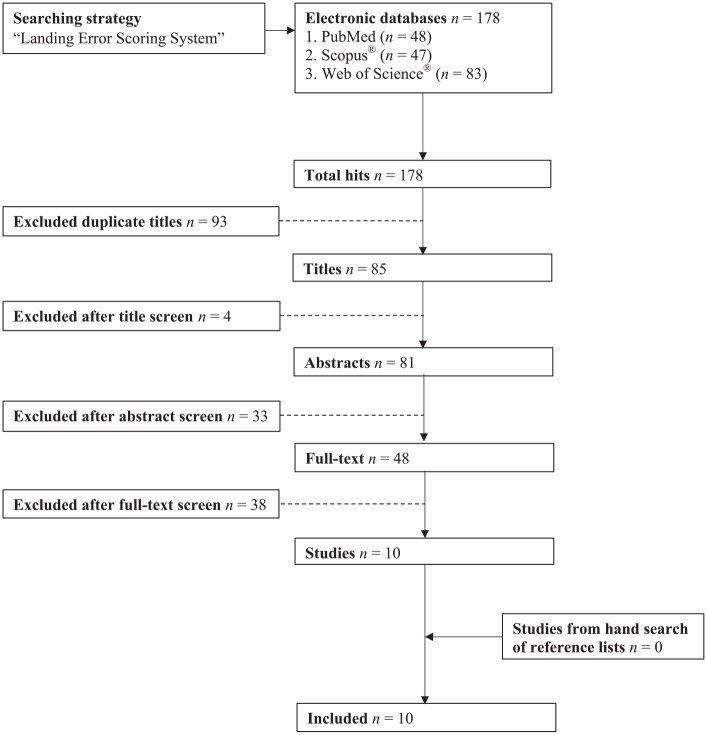

Three electronic databases (Figure 1) were searched using the keywords “Landing Error Scoring System” on March 28, 2018. Psychometric property terms were not included in the search strategy to favor an all-inclusive approach and avoid missing studies that addressed the reliability or validity of the LESS as part of their methodology without its being a primary aim. In addition, a hand search of the reference lists of all included studies was conducted.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the search strategy and study selection process.

Study Selection

The electronic search was conducted by 1 reviewer. Duplicate hits were removed first. Titles, abstracts, and full texts were screened sequentially for inclusion and exclusion criteria. In case of uncertainty regarding inclusion, a second reviewer was consulted.

Data Collection Process

Data concerning study design, population (number, sex, age, and activity level), LESS testing procedures, LESS scores, statistical analysis, and main results were extracted from studies using a standardized template by 1 reviewer, with the completeness of extraction verified by a second reviewer. The study design was reported according to Parab and Bhalerao.41 Studies were categorized into the following subcategories: reliability, validity against motion capture, and LESS predictive value for injury incidence. Four authors were contacted by email to request additional information regarding 8 of the included studies. Three authors responded, with 2 authors providing additional data for 2 studies.

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies (n = 10) using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) adapted for cross-sectional studies.36 Potentially identifiable information from studies was removed prior to quality appraisal to reduce assessment bias. The 2 reviewers achieved a consensus rating on all quality scores without the need for a third reviewer.

The NOS uses a “star system,” wherein more stars indicates a superior methodological quality. The NOS adapted for cross-sectional studies awards a maximum of 10 stars: 5 for selection (representativeness of the sample, sample size, nonrespondents, and ascertainment of the exposure), 2 for comparability, and 3 for outcome (assessment of outcome and statistical test). Reviewers agreed that for the statistical test item, the highest star rating would be allocated for the reporting of confidence intervals, quartiles, or limits of agreement. The methodological quality of studies was divided into 3 groups based on the number of stars awarded: weak (0-3 stars), moderate (4-6 stars), and strong (7-10 stars). Given that the reliability for NOS adapted for cross-sectional studies has not yet been determined, we assessed intra- and interrater reliability of our scores. Based on intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and confidence interval values, intrarater (ICC, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99) and interrater (ICC, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.80-0.98) reliability of scores was excellent.37 Finally, the level of evidence for each study was determined using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 table.

Summary Measures

Descriptive statistics were computed using Microsoft Office Excel 2016 and expressed in terms of means and SDs, minimum to maximum ranges (min to max), percentages (%), and counts (n). Weighted mean ± SD values based on sample size were computed to describe age and LESS scores of participants across studies. ICC values were interpreted according to Koo and Li26 using thresholds of 0.50, 0.75, and 0.90 to indicate moderate, good, and excellent reliability, respectively, with ICCs <0.50 indicating poor reliability. Standard error of measurement and minimal detectable change values were calculated for reliability studies when possible. Percentage of agreement between individual LESS items or categories based on LESS score (excellent, good, moderate, and poor) and 3-dimensional (3D) motion capture was reported for construct validity.

Results

Study Selection

Figure 1 illustrates the search strategy and study selection process. A total of 10 studies met inclusion requirements and were reviewed.

Study Characteristics

Since the majority of studies did not report descriptive characteristics of the sample used for reliability assessment, study characteristics were calculated from all participants tested with the LESS in included studies (Tables 1 and 2). The study sample size ranged from 13 participants49 to 2691 participants.40 A total of 3835 participants were represented across the 10 studies. All studies tested physically active populations. Sex distribution was described in all studies, totaling 2102 males (55%) and 1733 (45%) females. The mean age was reported in all but one40 of the 10 studies. The weighted mean age was 15.7 ± 2.0 years (minimum mean age 13.9 years39 and maximum mean age 28.5 years9). Overall LESS scores were reported in all but one38 of the 10 studies. Note that for interventional studies, LESS score before intervention was included in calculation. The calculated weighted mean for overall LESS score was 5.2 ± 1.7 errors (minimum mean LESS score of 4.4 errors39 and maximum mean LESS score 6.5 errors1). Only 3 studies reported the range of LESS scores,9,18,24 with the smallest and largest values being 0.0 errors9,18 and 13.3 errors.24

Table 1.

Summary of studies reporting reliability of the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS)

| Study (Year) | Quality a (Category) | Sample Size [Study Sample Size] | Population | Age, y b | LESS Score b | Intrarater | Interrater | Intersession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Padua et al (2009)40 | 6 stars (moderate) | 50 (M: 25, F: 25) [2691] | US military freshmen | Not specified | 4.9 ± 1.7 | ICC = 0.91 SEM = 0.42 MDC = 1.16 |

ICC = 0.84 SEM = 0.71 MDC = 1.97 |

× |

| Onate et al (2010)38 | 4 stars (moderate) | 19 (M: 0, F: 19) [19] | Division I college soccer players | 19.6 ± 0.8 | Not specified | × | ICC = 0.84 | × |

| Smith et al (2012)53 | 8 stars (strong) | 10 [92] | College and high school athletes | 18.3 ± 2.0 | 5.1 ± 1.95 c | ICC = 0.97 SEM = 0.52 MDC = 1.44 |

ICC = 0.92 | × |

| Beese et al (2015)1 | 8 stars (strong) | 40 (M: 0, F: 40) [40] | Soccer players and multisport athletes | 15.2 ± 1.2 | 6.5 ±1.9 | ICC = 0.91 SEM = 0.48 MDC = 1.33 |

× | × |

| Wesley et al (2015)55 | 7 stars (moderate) | 5 [36] | Athletes | 19.3 ± 1.15 c | 5.0 ± 2.0 | ICC = 0.99 SEM = 0.19 MDC = 0.53 |

× | × |

| James et al (2016)24 | 6 stars (moderate) | 34 (M: 19, F: 15) [34] | NCAA Division I soccer players | 19.6 ± 1.2 | 5.4 | ICC = 0.95 | × | × |

| Fox et al (2017)18 | 6 stars (moderate) | 10 (M: 0, F: 10) [32] | Subelite netball players | 23.2 ± 3.1 | 4.9 ± 2.3 | Cohen κ = 0.93 | Cohen κ = 0.75 | × |

| Scarneo et al (2017)49 | 9 stars (strong) | 13 (M: 2, F: 11) [13] | Recreationally active population | 21 ± 2 | 6.2 ± 1.7 | × | × | ICC = 0.81 SEM = 0.81 MDC = 2.25 |

| Dar et al (2019)9 | 8 stars (strong) | 10 [49] | Recreationally active population | 28.5 ± 5.6 | 4.8 ± 2.3 | ICC = 0.82 (CI = 0.571-0.947) |

ICC = 0.83 (CI = 0.451-0.956) |

× |

F, females; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; M, males; MDC, minimal detectable change; NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association.

Methodology quality assessment score based on Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies, weak (0-3 stars), moderate (4-6 stars), and strong (7-10 stars).36

Mean ± SD values for age (years) and LESS scores (errors) are shown for all the participants in the study, not the subsample assessed for reliability.

Weighted mean and weighted SD.

Table 2.

Summary of studies exploring Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) predictive value for injury incidence

| Study (Year) | Quality a (Category) | Study Sample Size | Type of Lower-Extremity Injury | Population | Age, y b | LESS Score Uninjured b | LESS Score Injured b | Significance Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith et al (2012)53 | 8 stars (strong) | 92 (U: 64, I: 28) | Noncontact ACL | College and high school athletes | 18.3 ± 2.0 | 5.0 ± 2.0 | 5.5 ± 1.9 | P = 0.320 |

| Padua et al (2015)39 | 8 stars (strong) | 829 (U: 822, I: 7) | Noncontact ACL | Elite youth soccer players | 13.9 ± 1.8 | 4.4 ± 1.7 | 6.2 ± 1.8 | P = 0.005 |

| James et al (2016)24 | 6 stars (moderate) | 34 (U: 11, I: 10) | Any injury that causes a player to miss 1 or more practices | NCAA Division I soccer players | 19.6 ± 1.2 | 5.8 ± 3.4 | 5.5 ± 2.5 | P = 0.830 |

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; I, injured; NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association; U, uninjured.

Methodology quality assessment score based on Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies, weak (0-3 stars), moderate (4-6 stars), and strong (7-10 stars).36

Mean ± SD values for age (years) and LESS (errors).

Risk of Bias Within Studies

Quality scores, levels of evidence, and study designs are presented in Appendix Table A2 (available online). Overall, studies were of moderate quality based on the NOS adapted for cross-sectional studies (10-point scale: mean 7.0 ± 1.5 points; range, 4-9). The level of evidence ranged between 2 and 4 based on the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 table.

Psychometric Properties of the LESS

Reliability

Reliability values for LESS were reported in 9 studies1,9,18,24,38,40,49,53,55 and derived from a total of 191 participants (Table 1). Both intra- and interrater reliability of the total LESS score was good to excellent based on ICCs (0.82-0.99 and 0.83-0.92, respectively). In addition to data reported in Table 1, Onate et al38 reported percentage agreement and kappa statistics between novice and expert raters for all individual LESS items, except for hip flexion at initial contact (IC) and hip flexion at maximal knee flexion, which were not clearly addressed. There was no significant agreement between raters for knee and trunk flexion at IC, and moderate agreement (65% agreement; κ = 0.533; P = 0.011) between raters for overall impression. For the remaining items, agreement between novice and expert raters ranged from 80% to 100% (κ = 0.459-1.0; P < 0.015). Only 1 study assessed the intersession reliability of the overall LESS score,49 which was good (ICC, 0.81).

Validity Against Motion Capture System

Two studies reported the validity of the LESS against “gold standard” 3D motion capture.38,40 Padua et al40 found that numerous lower-extremity kinematics and kinetics jump-landing measures significantly differed between participants subdivided into 4 quartiles based on excellent (LESS ≤ 4), good (4 < LESS ≤ 5), moderate (5 < LESS ≤ 6), and poor (LESS > 6) LESS performances. Accordingly, the authors concluded the LESS is a valid clinical assessment tool for detecting poor jump-landing biomechanics.40 Onate et al38 dichotomized 3D motion capture data into 0 and 1 to match LESS scoring and investigated the association between LESS scores and 3D motion data using phi correlations and percentage agreements. The last 2 items (joint displacement and overall impression) were not included because of the subjective nature of scoring, and the authors did not report any results for the hip flexion at IC and hip flexion at maximal knee flexion. Poor agreement (10% to 42%) was found for knee flexion at IC, lateral trunk flexion at IC, and symmetric foot contact at IC. Moderate agreement (68% to 74%) was found for trunk flexion at IC, knee valgus at IC, stance width (narrow), and knee valgus displacement. The remaining LESS items showed excellent agreement (84% to 100%). Hence, Onate et al concluded that validity of the LESS was item dependent.

LESS Predictive Value for Injury Incidence

Two studies with total sample size of 921 participants reported the predictive value of the LESS for noncontact ACL injury incidence (Table 2).39,53 The longitudinal cohort study39 concluded that the LESS has a screening potential for noncontact ACL injury, identifying 5 errors as an optimal cutoff point, yielding a sensitivity of 86% (95% CI, 42% to 99%) and specificity of 64% (95% CI, 62% to 67%). On the other hand, the case-control study53 did not find any significant relationship between LESS score and risk of suffering ACL injury, either for all participants as a combined group (P = 0.32) or for subgroups of male (P = 0.67), female (P = 0.16), high school (P = 0.37), or college (P = 0.66) participants. Likewise, there was no significant relationship between LESS as categorical variable (ie, poor, moderate, good, and excellent performances) and noncontact ACL injury incidence (P = 0.35).

One study24 compared preseason LESS scores between soccer players with no previous lower-extremity injury who suffered an injury in the subsequent season and those who remained uninjured (Table 2). Lower-extremity injury was defined as any injury that caused players to miss 1 or more practices or games. There were no statistically significant differences (P = 0.83) in preseason LESS scores between those who sustained a lower-extremity injury and those who remained uninjured.

Discussion

Reliability

Findings from 9 studies of relatively strong methodological quality indicated good-to-excellent intrarater, interrater, and intersession reliabilities. Noteworthy is that reliability of the overall LESS score was derived from uninjured military freshmen and sportspeople with a mean age between 15 and 28 years. Although LESS has been used in younger14,46 and injured20,29 individuals; generalizability of reliability findings across these population groups is not confirmed. Furthermore, the findings showed that some individual items in LESS scoring are less reliable than others.38 More specifically, no significant agreement between raters was found for knee and trunk flexion at IC and moderate agreement for overall impression. Given that knee flexion during landing and stiff landing with less ankle, knee, hip, and trunk flexion are key risk factors for knee injury incidence,13,31,43 the lack of agreement in these LESS metrics is of concern. In the LESS, a knee flexion at IC of less than 30° defines an error (Appendix Table A1, available online). Accurately determining an angular measure from visual observations is challenging,16,25 which can explain the lower reliability of the knee flexion angle at IC item. The overall impression item is subjective in nature, and the representation of an excellent, average, and poor landing may differ between raters. One solution could be to use a video analysis software to objectively assess angle-related items during LESS scoring to decrease the subjective nature of items. Although outcomes from such assessments might be more accurate, the scoring process would take more time. To decrease scoring time and improve consistency of LESS ratings, the automated quantification of the LESS using markerless motion capture technology has been developed recently.9,33 The markerless method is as reliable as expert LESS raters.33 The time and cost saving benefits of the markerless method, however, need to be weighed against the additional hardware and software expenditures.

Validity Against Motion Capture System

Some of the most frequently addressed biomechanical risk factors linked with ACL injury include increased knee valgus angle and moment8,11,12,21,28,35 and increased ground-reaction force resulting from stiff landing.5,6,10,13,45,51,52 Padua et al40 associated poor LESS scores with decreased peak knee and hip flexion angles and increased peak knee valgus angles and moments. Onate et al38 found that the validity of LESS items was strictly item dependent. Again, one of the main concerns is that angles are difficult to estimate visually. A small kinematic difference (eg, knee angle 29° = error present; knee angle 30° = error absent) in performance can result in poor agreement between clinical LESS scoring and motion capture scoring. Onate et al suggested creating a range of acceptable angular values (eg, knee angle at IC between 25° to 30°) to improve scoring validity, although no further studies were undertaken.

The validity of the LESS was strictly item dependent,38 which might mean modification of the original LESS scoring template. The fact that most of the key factors for ACL injury had moderate and excellent agreement nonetheless supports the LESS as a valid screening tool for assessing ACL injury risk jump-landing biomechanics.

LESS Predictive Value for Injury Incidence

Two studies of strong methodological quality explored the predictive value of the LESS for ACL injury incidence and reported equivocal results.39,53 Padua et al39 employed a prospective study design. Of the 829 elite young soccer players with a mean age of 13.9 ± 1.8 years, 7 participants suffered a noncontact ACL injury during the 2.5-year observation period. Based on the data, 5 errors were identified as an optimal cut point for distinguishing between athletes with low and high risk of ACL injury. Sample size calculations and post hoc power analyses were not reported.

The study conducted by Smith et al53 assessed a population of college and high school athletes from a range of sports with a mean age of 18.3 ± 2.0 years. The study was designed as a prospective cohort with 5047 screenings within a 3-year period. Smith et al did not find any significant relationship between LESS scores and risk of ACL injury.

The lack of agreement in the predictive value of the LESS between studies can be explained by differences in sampled populations in terms of age, main sporting events, and exclusion criteria (Smith et al53 excluded athletes with a history of ACL injury, whereas Padua et al39 did not). Furthermore, the lack of statistical power in both studies39,53 is a limiting factor to the generalization of results.

One moderate quality study24 recorded preseason LESS scores of soccer players without lower-extremity injury history and did not find any significant difference between participants who sustained an injury during the subsequent season and those who remained uninjured. The study is deemed to have several limitations that could explain the lack of association between LESS and lower-extremity injuries, including the relatively small sample size (n = 34), short follow-up period, and lack of differentiation between contact and noncontact mechanisms of injury. Fundamentally, the LESS was developed as an injury risk screening tool that identifies poor biomechanical control, which is a risk factor for noncontact, rather than contact, lower-extremity injuries. Thus, the relevance of the findings from James et al24 is questioned.

Based on the current scientific evidence, the predictive value of the LESS for noncontact lower-extremity injury incidence remains uncertain. Studies with a greater statistical power are needed to affirm the relationship between LESS scores and noncontact ACL injury incidence, as well as incidence of other noncontact lower-extremity injuries.

Limitations

This systematic review combines data across studies to detail the reliability, validity against motion capture, and predictive validity of the LESS. The main limitations of this review were the varied methodological quality of studies and the inability to perform meta-analysis of data due to lack of detail. Another important limitation is that populations included, testing protocols, and calculations of total LESS score varied across studies. Population characteristics—for example, age, sex, and activity level—can significantly influence LESS scores,3,27,53 and therefore the results of this literature review are most relevant to uninjured military freshmen and sportspeople with a mean age between 14 and 28 years.

Conclusion

The current evidence indicates that the overall LESS score has good-to-excellent intrarater, interrater, and intersession reliabilities. The validity of the individual LESS items against 3D motion capture is item dependent; however, the validity of LESS items addressing key knee-injury risk factors is moderate to excellent. The LESS predictive value for noncontact ACL injury and other noncontact lower-extremity injury incidence cannot be ascertained based on the current scientific evidence. Larger scale multicenter studies are needed to confirm the association between LESS scores and ACL injury incidence, as well as other noncontact lower-extremity injury incidence.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 34793_Appendix for Is the Landing Error Scoring System Reliable and Valid? A Systematic Review by Ivana Hanzlíková and Kim Hébert-Losier in Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach

Footnotes

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest in the development and publication of this article.

References

- 1. Beese ME, Joy E, Switzler CL, Hicks-Little CA. Landing Error Scoring System differences between single-sport and multi-sport female high school-aged athletes. J Athl Train. 2015;50:806-811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bell DR, Smith MD, Pennuto AP, Stiffler MR, Olson ME. Jump-landing mechanics after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a Landing Error Scoring System study. J Athl Train. 2014;49:435-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beutler AI, de la Motte SJ, Marshall SW, Padua DA, Boden BP. Muscle strength and qualitative jump-landing differences in male and female military cadets: the jump-ACL study. J Sports Sci Med. 2009;8:663-671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bird SP, Markwick WJ. Musculoskeletal screening and functional testing: considerations for basketball athletes. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11:784-802. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chappell JD, Herman DC, Knight BS, Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE, Yu B. Effect of fatigue on knee kinetics and kinematics in stop-jump tasks. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1022-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chappell JD, Yu B, Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE. A comparison of knee kinetics between male and female recreational athletes in stop-jump tasks. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:261-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chimera NJ, Warren M. Use of clinical movement screening tests to predict injury in sport. World J Orthop. 2016;7:202-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cronström A, Creaby MW, Smith M, Blackmore T, Nae J, Ageberg E. Alterations in trunk and lower extremity muscle activation are associated with knee abduction during weight-bearing activities in patients with anterior cruciate ligament injury. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25:S119. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dar G, Yehiel A, Cale’ Benzoor M. Concurrent criterion validity of a novel portable motion analysis system for assessing the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) test. Sports Biomech. 2019:18(4):426-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Decker MJ, Torry MR, Wyland DJ, Sterett WI, Steadman JR. Gender differences in lower extremity kinematics, kinetics and energy absorption during landing. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2003;18:662-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dempsey AR, Elliott BC, Munro BJ, Steele JR, Lloyd DG. Whole body kinematics and knee moments that occur during an overhead catch and landing task in sport. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2012;27:466-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dempsey AR, Lloyd DG, Elliott BC, Steele JR, Munro BJ, Russo KA. The effect of technique change on knee loads during sidestep cutting. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1765-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Devita P, Skelly WA. Effect of landing stiffness on joint kinetics and energetics in the lower extremity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24:108-115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DiStefano LJ, Beltz EM, Root HJ, et al. Sport sampling is associated with improved landing technique in youth athletes. Sports Health. 2018;10:160-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DiStefano LJ, Padua DA, DiStefano MJ, Marshall SW. Influence of age, sex, technique, and exercise program on movement patterns after an anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention program in youth soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:495-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ekegren CL, Miller WC, Celebrini RG, Eng JJ, Macintyre DL. Reliability and validity of observational risk screening in evaluating dynamic knee valgus. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:665-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Emery CA, Roy T-O, Whittaker JL, Nettel-Aguirre A, Van Mechelen W. Neuromuscular training injury prevention strategies in youth sport: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:865-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fox AS, Bonacci J, McLean SG, Saunders N. Efficacy of ACL injury risk screening methods in identifying high-risk landing patterns during a sport-specific task. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27:525-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fox AS, Bonacci J, McLean SG, Spittle M, Saunders N. A systematic evaluation of field-based screening methods for the assessment of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury risk. Sports Med. 2016;46:715-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gokeler A, Eppinga P, Dijkstra PU, et al. Effect of fatigue on landing performance assessed with the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) in patients after ACL reconstruction. A pilot study. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9:302-311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, et al. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:492-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J Athl Train. 2007;42:311-319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hueber GA, Hall EA, Sage BW, Docherty CL. Prophylactic bracing has no effect on lower extremity alignment or functional performance. Int J Sports Med. 2017;38:637-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. James J, Ambegaonkar JP, Caswell SV, Onate J, Cortes N. Analyses of landing mechanics in Division I athletes using the Landing Error Scoring System. Sports Health. 2016;8:182-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Knudson D. Validity and reliability of visual ratings of the vertical jump. Percept Mot Skills. 1999;89:642-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropract Med. 2016;15:155-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kraus K, Schütz E, Doyscher R. The relationship between a jump-landing task and Functional Movement Screen items: a validation study. J Strength Condition Res. 2019;33:1855-1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krosshaug T, Nakamae A, Boden BP, et al. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury in basketball: video analysis of 39 cases. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:359-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kuenze CM, Foot N, Saliba SA, Hart JM. Drop-landing performance and knee-extension strength after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Athl Train. 2015;50:596-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lam KC, McLeod TCV. The impact of sex and knee injury history on jump-landing patterns in collegiate athletes: a clinical evaluation. Clin J Sport Med. 2014;24:373-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leppänen M, Pasanen K, Kujala UM, et al. Stiff landings are associated with increased ACL injury risk in young female basketball and floorball players. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:386-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Markbreiter JG, Sagon BK, McLeod TCV, Welch CE. Reliability of clinician scoring of the landing error scoring system to assess jump-landing movement patterns. J Sport Rehabil. 2015;24:214-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mauntel TC, Padua DA, Stanley LE, et al. Automated quantification of the Landing Error Scoring System with a markerless motion-capture system. J Athl Train. 2017;52:1002-1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McCunn R, aus der Fünten K, Fullagar HH, McKeown I, Meyer T. Reliability and association with injury of movement screens: a critical review. Sports Med. 2016;46:763-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McLean SG, Fellin RE, Suedekum N, Calabrese G, Passerallo A, Joy S. Impact of fatigue on gender-based high-risk landing strategies. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:502-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Modesti PA, Reboldi G, Cappuccio FP, et al. Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mukaka MM. A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med J. 2012;24:69-71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Onate J, Cortes N, Welch C, Van Lunen B. Expert versus novice interrater reliability and criterion validity of the Landing Error Scoring System. J Sport Rehabil. 2010;19:41-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Padua DA, DiStefano LJ, Beutler AI, de la Motte SJ, DiStefano MJ, Marshall SW. The Landing Error Scoring System as a screening tool for an anterior cruciate ligament injury-prevention program in elite-youth soccer athletes. J Athl Train. 2015;50:589-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Padua DA, Marshall SW, Boling MC, Thigpen CA, Garrett WE, Jr, Beutler AI. The Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) is a valid and reliable clinical assessment tool of jump-landing biomechanics: the JUMP-ACL study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:1996-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Parab S, Bhalerao S. Study designs. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1:128-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Parkkari J, Taanila H, Suni J, et al. Neuromuscular training with injury prevention counselling to decrease the risk of acute musculoskeletal injury in young men during military service: a population-based, randomised study. BMC Med. 2011;9:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Podraza JT, White SC. Effect of knee flexion angle on ground reaction forces, knee moments and muscle co-contraction during an impact-like deceleration landing: implications for the non-contact mechanism of ACL injury. Knee. 2010;17:291-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pointer CE, Reems TD, Hartley EM, Hoch JM. The ability of the Landing Error Scoring System to detect changes in landing mechanics: a critically appraised topic. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2017;22(5):12-20. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pollard CD, Sigward SM, Powers CM. Limited hip and knee flexion during landing is associated with increased frontal plane knee motion and moments. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2010;25(2):142-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pryor JL, Root HJ, Vandermark LW, et al. Coach-led preventive training program in youth soccer players improves movement technique. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20:861-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ramang DS. The landing error scoring system as a tool for assessing anterior cruciate ligament injury. Adv Sci Lett. 2017;23:6694-6696. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Read PJ, Oliver JL, De Ste Croix MBA, Myer GD, Lloyd RS. A review of field-based assessments of neuromuscular control and their utility in male youth soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33:283-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Scarneo SE, Root HJ, Martinez JC, et al. Landing technique improvements after an aquatic-based neuromuscular training program in physically active women. J Sport Rehabil. 2017;26:8-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schussler E, Chaudhari AM, Cortes N, et al. iLESS visual estimation is a valid measure of knee valgus during drop vertical jump. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:407.24441216 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shimokochi Y, Ambegaonkar JP, Meyer EG, Lee SY, Shultz SJ. Changing sagittal plane body position during single-leg landings influences the risk of non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:888-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shimokochi Y, Yong Lee S, Shultz SJ, Schmitz RJ. The relationships among sagittal-plane lower extremity moments: implications for landing strategy in anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention. J Athl Train. 2009;44:33-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Smith HC, Johnson RJ, Shultz SJ, et al. A prospective evaluation of the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) as a screening tool for anterior cruciate ligament injury risk. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:521-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tiirikainen K, Lounamaa A, Paavola M, Kumpula H, Parkkari J. Trend in sports injuries among young people in Finland. Int J Sports Med. 2008;29:529-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wesley CA, Aronson PA, Docherty CL. Lower extremity landing biomechanics in both sexes after a functional exercise protocol. J Athl Train. 2015;50:914-920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, 34793_Appendix for Is the Landing Error Scoring System Reliable and Valid? A Systematic Review by Ivana Hanzlíková and Kim Hébert-Losier in Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach