Abstract

Context:

Dosing parameters are needed to ensure the best practice guidelines for knee osteoarthritis.

Objective:

To determine whether resistance training affects pain and physical function in individuals with knee osteoarthritis, and whether a dose-response relationship exists. Second, we will investigate whether the effects are influenced by Kellgren-Lawrence grade or location of osteoarthritis.

Data Sources:

A search for randomized controlled trials was conducted in MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL, from their inception dates, between November 1, 2018, and January 15, 2019. Keywords included knee osteoarthritis, knee joint, resistance training, strength training, and weight lifting.

Study Selection:

Inclusion criteria were randomized controlled trials reporting changes in pain and physical function on humans with knee osteoarthritis comparing resistance training interventions with no intervention. Two reviewers screened 471 abstracts; 12 of the 13 studies assessed were included.

Study Design:

Systematic review.

Level of Evidence:

Level 2.

Data Extraction:

Mean baseline and follow-up Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scores and standard deviations were extracted to calculate the standard mean difference. Articles were assessed for methodological quality using the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) 2010 scale and Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias.

Results:

The 12 included studies had high methodological quality. Of these, 11 studies revealed that resistance training improved pain and/or physical function. The most common regimen was a 30- to 60-minute session of 2 to 3 sets of 8 to 12 repetitions with an initial resistance of 50% to 60% of maximum resistance that progressed over 3 sessions per week for 24 weeks. Seven studies reported Kellgren-Lawrence grade, and 4 studies included osteoarthritis location.

Conclusion:

Resistance training improves pain and physical function in knee osteoarthritis. Large effect sizes were associated with 24 total sessions and 8- to 12-week duration. No optimal number of repetitions, maximum strength, or frequency of sets or repetitions was found. No trends were identified between outcomes and location or Kellgren-Lawrence grade of osteoarthritis.

Keywords: knee osteoarthritis, knee joint, resistance training, strength training, weight lifting

Arthritis, which is a general term that encompasses osteoarthritis and inflammatory joint diseases, is a leading cause of disability and is projected to affect 78.4 million adults by 2040.4,15 Symptomatic knee osteoarthritis (KOA) alone affects 12% of American adults, making it one of the most frequent causes of physical disability and pain among older persons.10 There has been a recent trend in recognizing that KOA is a heterogeneous disease of multiple distinct phenotypes rather than a single disease.8 Dell’Isola et al7 identified 6 distinct knee phenotypes: chronic pain, inflammation, metabolic syndrome, bone and cartilage metabolism, mechanical overload, and minimal joint disease. On the other hand, Deveza et al8 broadly classified the phenotypes into clinical, imaging, and laboratory.

The Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) recommendations for hip and knee OA management note a number of interventions have been universally recommended, though the efficacy of many of these treatments (eg, massage, ultrasound, heat/ice therapy) has not been confirmed.31 However, OARSI reports there is a growing body of evidence for the efficacy of exercise interventions for treating KOA symptoms.31 The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines include specific recommendations for muscle and bone strengthening activity for healthy and chronic disease populations.26 The optimal dose of physical activity and resistance training in individuals with KOA remains unknown. Moreover, whether the effects are generalizable to these proposed phenotypes is also uncertain.

In general, exercise prescription can be complex due to many variables. When recommending resistance training, one must consider repetitions, sets, intensity, duration, frequency, number of total exercises, and resistance progression. Despite the increasing recognition of the importance of resistance training in health promotion and disease management, it remains unknown what dosing parameters (magnitude, duration, frequency) and type of exercise (isometric, eccentric, concentric) affect outcome. It is also unknown whether the location and degree of OA affect the resistance training prescription.

Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews have demonstrated evidence that various types of exercise, including aerobic and resistance training, are effective in reducing pain and disability in those with KOA.2,13,18,19,30 To date, no study has determined whether resistance training alone is an effective modality to relieve KOA pain and improve patient physical function. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review is to determine whether resistance training affects pain and physical function in individuals with KOA, and whether a dose-response relationship exists between training regimen and patient outcomes.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

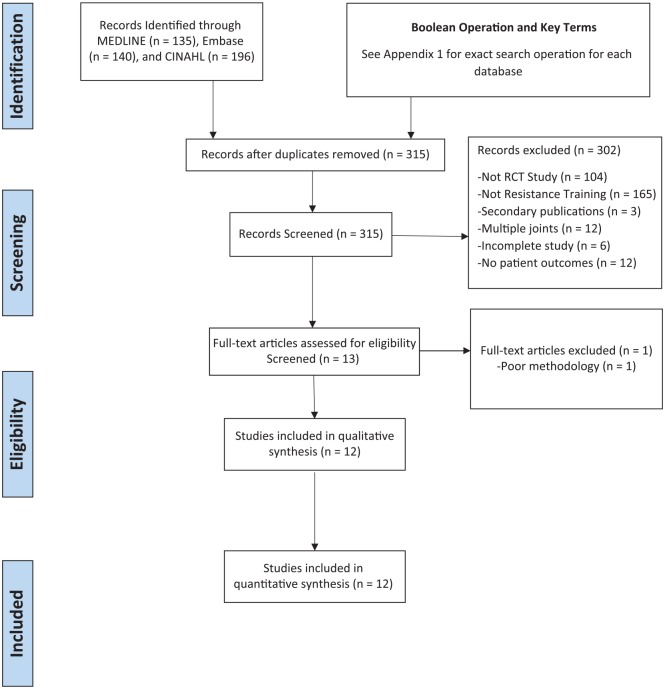

Prior to writing, the study selection, eligibility criteria, data extraction, and standard mean difference (SMD) calculations were conducted based on a prespecified protocol and registered on PROSPERO (ID CRD 42019128275).3 Our approach follows the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement and PRISMA flowchart of selecting articles for review (Figure 1).25

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria consisted of humans with symptomatic primary KOA in at least 1 knee who were included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing resistance training interventions alone with no intervention, sham, placebo, self-management, education, or balance exercises. Resistance training was defined as exercising a muscle or muscle group against external resistance. Only studies providing patient-reported outcomes on pain or disability were eligible. There were no restrictions regarding age, body mass index (BMI), or sex. Only published trials written in the English language were included.

Information Sources

A comprehensive search for randomized controlled trials was conducted in MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase (Elsevier, Embase.com), and CINAHL (EBSCO), from each database’s inception date. A search strategy, using a combination of subject headings and keywords for KOA and resistance training, was developed by one of the authors (J.M.R.), a trained medical librarian. RCTs on humans were identified by the authors using the sensitivity- and precision-maximizing version of Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategies (2011 revision).20 No date restrictions were used during the search phase. Complete search strategies are available in Appendix 1 (available in the online version of this article). The literature search was performed between November 1, 2018, and January 15, 2019.

Study Selection

Two reviewers independently performed an eligibility assessment on each trial in the database search by initially eliminating studies that did not investigate resistance training. Titles and abstracts were screened, followed by a full-text article review if the trial was deemed eligible by at least 1 reviewer. If there was any discordance, the same 2 reviewers engaged in a detailed discussion and a final consensus was reached.

Data Collection

Using Microsoft Excel, data extraction included the following: authors, year of publication, number of participants, resistance training intervention type, control intervention, location of KOA, Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) score, baseline and follow-up outcome measures for knee pain, and self-reported physical function. The following details of the interventions were also recorded: single session duration, repetitions and sets, maximum resistance strength, frequency (number of sessions per week), total number of sessions, and overall intervention duration (Appendix 2, Table A1, available online). The mean baseline and follow-up values with corresponding standard deviations were extracted and used to calculate the SMD, where possible. Trials that compared more than 1 intervention to resistance training were treated as separate comparisons and analyzed independently.

Assessment of Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias

The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) 2010 statement is an evidence-based reporting guideline that aims to improve research transparency and reduce waste to address methodological issues specific to trials of nonpharmacologic treatments, such as surgery, rehabilitation, or psychotherapy. The CONSORT scale is composed of a 25-item checklist with emphasis on reporting how the trial was designed, analyzed, and interpreted.24 Studies were assessed independently by 2 reviewers, and scoring discrepancies were resolved by consensus discussion. The reviewers agreed that a study with a score greater than 20 was considered high quality, a score between 16 and 20 was considered good quality, a score between 11 and 15 was deemed fair quality, and a score of 10 or less was considered poor quality.

The Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials was utilized to further assess the risk of potential bias.14 The 2 reviewers independently assessed risk for bias using this tool and supplementary material from the Cochrane handbook criteria (Appendix 2, Table A2, available online). Any disagreement was resolved by consensus discussion.

Data Synthesis—Effect Sizes

For study designs utilizing a resistance and control group, reported Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Pain and Physical Function scales were determined, independently, to express the size of the intervention effect in each study relative to the variability observed in the particular study’s WOMAC measure(s) of follow-up. The SMD for each group was determined by calculating the mean difference between reported baseline and follow-up WOMAC assessments and dividing the result by their pooled standard deviation.

Notably, the longest reported time frame of follow-up was established to identify the mean difference among studies with multiple postintervention time periods. For studies without reported measures to quantify variation, the standard deviation used to calculate SMD was obtained from the reported standard error of the mean and confidence intervals, respectively (Appendix 2, Table A3, available online).1,29 Thereby, the SMD measures of effect size, typically reported as Cohen d, are characterized by the standard interpretation (large, 0.8; moderate, 0.5; small, 0.2).6

Results

Study Selection

The initial literature search resulted in 471 articles (135 in Medline, 196 in CINAHL, and 140 in Embase). After removal of duplications, 315 articles were screened on title and abstract. Thirteen articles were assessed for eligibility, and 12 studies1,5,9,11,12,16,17,21,22,23,27,29 were included. One article28 was excluded given poor quality of methodology (Figure 1).

Study Characteristics

The 12 studies involved 1428 participants (71.3% female) allocated to resistance training or control groups. Mean age ranged from 51.9 to 71.2 years. Mean BMI ranged from 25.0 to 32.7 kg/m2. The mean BMI was available in 9 of 12 studies (Table 1). The diagnostic criteria for KOA used to determine participant inclusion in individual studies varied. Five studies utilized the American College of Rheumatology criteria for diagnosing KOA.5,11,12,27,29 Seven studies1,9,16,17,21-23 utilized a combination of clinical criteria and radiographic criteria (KL score) for diagnosing KOA.1,9,16,21-23

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Study | Participants (M:F) | Groups (M:F) | Age, y, Mean (SD) | BMI, kg/m2, Mean (SD) | KL Grade | OA Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker 20011 | 46 (10:36) | Attention control (4:19) Exercise (6:17) |

68 (6) 69 (6) |

32 (5) 31 (4) |

3 | TF and/or PF |

| Chaipinyo 20095 | 48 (11:37) | Balance (9:15) Strength (2:22) |

62 (6) 70 (6) |

25 (4) 25 (3) |

N/A | N/A |

| DeVita 20189 | 30 (12:18) | Control (7:8) Training (5:10) |

56.2 (8.9) 58.1 (6.5) |

27.9 (3.9) 26.4 (4.0) |

N/A | TF |

| Ettinger 199711 | 439 (131:308) | Health education (47:102) Resistance exercise (39:107) Aerobic exercise (45:99) |

69 (6) 68 (6) 69 (6) |

N/A | N/A | TF |

| Foroughi 201112 | 45 (0:54) | Sham (0:28) PRT (0:26) |

65 (7) 66 (8) |

32.7 (8.4) 31.4 (5) |

2 | N/A |

| Jan 200816 | 98 (19:79) | Control (5:25) HR (7:27) LR (7:27) |

62.8 (6.3) 63.3 (6.6) 61.8 (7.1) |

N/A (H&W provided) |

2 | N/A |

| Jorge 201517 | 60 (F) | Control group (31 F) Experimental group (29 F) |

59.9 (7.5) 61.7 (6.4) |

31.4 (4.42) 30.6 (5.75) |

1 | N/A |

| Lin 200921 | 108 (33:75) | Control (10:26) Prop training (11:25) Strength training (12:24) |

62.2 (6.7) 63.7 (8.2) 61.6 (7.2) |

N/A (H&W provided) |

<3 | N/A |

| McKnight 201022 | 273 (63:210) | Self-management (22:65) Strength training (18:73) Combination (23:72) |

52.6 (6.5) 53.3 (7.2) 51.9 (7.7) |

27.9 (4.1) 27.9 (4.5) 27.4 (4.1) |

2 | N/A |

| Mikesky 200623 | 221 (93:128) | Range of motion (44:64) Strength training (49:64) |

68.6 (7.5) 69.4 (8.0) |

29.0 (5.4) 29.6 (5.6) |

>2 | TF |

| Rogers 201227 | 33 (13:20) | Sham KBA Resistance training KBA + RT |

71.2 (10.9) 70.7 (10.7) 70.8 (6.5) 68.8 (10.1) |

30.8 28.9 28.2 29.2 |

N/A | N/A |

| Topp 200229 | 102 (28:74) | Control (7:28) Dynamic (10:25) Isometric (11:21) |

60.94 (1.92) 65.57 (1.82) 63.53 (1.90) |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

BMI, body mass index; F, female; H&W, height and weight; HR, high resistance; KBA, kinesthesia, balance, and agility; KL, Kellgren-Lawrence; LR, low resistance; M, male; N/A, not applicable; OA, osteoarthritis; PF, patellofemoral; PRT, progressive resistance training; RT, resistance training; TF, tibiofemoral.

One study assessed the severity of the OA in each compartment of the knee (medial, lateral, and patellofemoral).1 Three studies reported the location of OA as tibiofemoral,9,11,23 and 1 study reported tibiofemoral and/or patellofemoral OA.29 The remaining studies did not specify OA location9,11,23,29 (Table 1).

Assessment of Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias

Overall, 13 studies were included for methodological quality analysis. Of these, 12 were rated with high methodological quality, and 1 study28 was excluded due to poor quality (CONSORT score, 9). The mean CONSORT quality score was 20.3 (range, 17-24.5). Adequate sequence generation was reported in 11 studies (91.6%),1,5,9,11,12,16,17,21,22,27,29 and adequate allocation concealment was reported in 9 studies (75%).1,5,11,12,17,21,22,27,29

None of the studies met the criteria of blinding to intervention because of the inherent challenge in blinding clinicians and participants in studies involving exercise. Furthermore, the study designs did not clearly state whether participants were informed that there was more than 1 group (control vs intervention) or which group they were in. The majority of the studies did not provide sufficient details on selective outcome reporting and other forms of bias such as ethics or funding.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Of the studies, 11 revealed resistance training improved pain and/or quality of life.1,5,9,11,12,16,17,21,23,27,29 Six studies with 297 participants demonstrated that resistance training was associated with large effect sizes for WOMAC Pain scores1,9,16,17,21,27 (Appendix Table A3, available online). One study21 found both resistance training and proprioception training individually to be associated with a large effect size. Two studies12,29 demonstrated medium effect sizes for WOMAC Pain scores. In contrast, 1 study22 found resistance training alone had a small effect size, compared with a medium effect size in the combination group that underwent strength training with self-management and education.

Similarly, 6 studies showed that resistance training was related to large effect sizes for WOMAC Physical Function scores.1,9,16,17,21,27 One study revealed a large effect size between Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score function in activities of daily living and the strength training group compared with a small effect size in the balance group.5

The effect size could not be calculated in 1 study, as change in WOMAC was reported rather than postintervention WOMAC score.23 In another study,11 researchers created a questionnaire to provide self-reported disability and pain intensity scores. Effect sizes were not calculated for this unique outcome scale as the values would not be comparable with those of the other included studies, which all used the WOMAC to report outcomes.

Optimal Dosing

Several of the studies did not report details of session duration.1,5,12,17,21-23,27 Of the studies that did provide session details, the sessions ranged from 30 to 60 minutes. Large effect sizes for the WOMAC Pain and Physical Function subscales were associated with 20 minutes of seated concentric/eccentric quad strengthening; 30 and 50 minutes of high-resistance and low-resistance full knee flexion/extension exercises, respectively; and 60-minute strength training sessions of quad strengthening consisting of leg extension, leg press, and forward lunges.9,16,21 Small (WOMAC, isometric) and medium (WOMAC, dynamic group) effect sizes for the WOMAC Pain and Physical Function subscales were associated with 40-minute sessions for dynamic and isometric strength training exercises that included warm-up sessions and a 5-minute cool down.29

A wide range of sets and repetitions were implemented in the studies’ interventions. Two to 3 sets of 8 to 12 repetitions were the most commonly prescribed. One of the studies was noted to have a large effect size with fewer sets (3 sets) for their high-resistance strength training group compared with the low-resistance group (10 sets).16 There was also wide variability among the measurement, prescription, and progression of resistance used in training. Resistance maximum was the most commonly used measurement of resistance; however, some studies used weight in kilograms subjective to a participant’s perceived fatigue after a certain number of repetitions or contracting as hard as possible without pain. The most common regimen was to start at 50% to 60% of maximum resistance. There was no identifiable trend in progression of maximum strength because of the extensive variability in which progression was implemented in the studies’ designs.

Two studies had a medium effect size in WOMAC Pain and Physical Function, and it was unclear how maximum strength influenced sets and repetitions.5,12 McKnight et al22 demonstrated small size effects for the strength group, whose maximum resistance was not clearly defined, as it was reported as “based on the participants needs.” Jan et al16 reported large effect sizes for both low- and high-resistance training.

Three supervised sessions per week was the most common regimen in the selected studies. Only 1 study prescribed strength training twice per week.17 Another study reported 5 sessions per week.5 One study increased the frequency of intervention from 3 times per week for the first 6 months to 5 times per week, which was then tapered down to once per week in the last 3 months of the study.23 Among the studies with large effect size in WOMAC Pain and Physical Function subscales, 4 studies had 3 dose resistance sessions per week9,16,21,27 whereas 1 study had only 2 sessions per week.17 The remaining studies with small to medium effect sizes also had 3 sessions per week.12,22,29 There was a wide range in the total number of sessions. The most common number of sessions was 24 (range, 20-312). More specifically, 20 to 36 sessions were associated with a large effect size.9,16,17,21,27 The total duration of resistance training ranged from 4 weeks to 18 months, with the average being 27 weeks.

Discussion

The main purpose of this systematic review was to determine whether resistance training affects pain and physical function in patients with KOA. The major finding was that large and medium effect sizes were related to decreased pain and improved physical function. A common theme appears to be with quadriceps muscle strengthening and its positive effects on pain and function, whether that be with open or closed chain techniques. No trends between resistance training outcomes and location or KL grade of KOA were identified.

Furthermore, this review aimed to discern whether a dose-response relationship exists between training regimen and patient outcomes. Several observations arose from the results. In total, 24 resistance training sessions and 8- to 12-week duration were most frequently associated with large effect sizes. It was not possible to draw a firm conclusion about the optimal number of repetitions, maximum strength, or frequency of intervention sets or repetitions. However, the most common regimens prescribed are 2 to 3 sets of 8 to 12 repetitions, starting at a resistance maximum of 50% to 60% with a progressive scale for 3 supervised sessions per week, for an average of 27 weeks. Seven of the 12 studies commented on single-session duration length. No specific single-session duration was associated with greater effect size. Based on the studies reviewed, it appears that there is no impact of duration of care on the effect size in WOMAC Pain and Physical Function. Alternatively, the results of 1 study that demonstrate small effects of WOMAC Pain and Physical Function with a 24-month exercise program may not be necessarily as beneficial as one would think.22

There were several limitations in the methodology of the selected studies, with the most significant issue being that none of the study designs clearly stated that participants were blinded. The authors recognize that because of the participant engagement, it is difficult to blind participants to physical training interventions. Furthermore, it is not possible to blind participants to self-reported outcome measures. However, it would be possible to blind participants to which group they were in, and this was not reported in any of the studies. Adequate allocation concealment was reported in 75% of the studies. Most of the included studies are lacking sufficient details on selective outcome reporting and other forms of bias such as ethics or funding.

The heterogeneity among studies, especially the significant lack of conformity in dosing variables, makes evaluating the result of strength challenging, and therefore we are unable to determine concrete optimal dosing for resistance training in patients with KOA. It is particularly difficult to advise a formal recommendation for the number of repetitions required given that each study used different strength training exercises among the intervention group. Furthermore, methods determining maximum strength varied in each study as these studies used different dose resistance techniques, which subsequently helped determine the increments required to increase resistance in successive sets. Perhaps this suggests that more clear quantification of resistance measures is needed for true benefits to be seen. Furthermore, the lack of standardization of pain outcome and function scores in each of the studies reviewed additionally makes it difficult to draw inferences.

Conclusion

This systematic review suggests that there may be resistance training–specific dosing variables that improve pain and quality of life for patients suffering from KOA, but specific optimal resistance dosing recommendations remain unclear due to the heterogeneity of the strength training techniques, sets, repetitions, maximum strength, total number of sessions, and duration of regimen. Lack of standardization of pain outcome and function scores in each of the studies reviewed additionally make it difficult to draw inferences, as there were 2 studies that did not use WOMAC Pain and Physical Function subscores.5,11 A pervasive premise appears to be that quadriceps muscle strengthening has positive effects on pain and function, whether that be with open or closed chain techniques as demonstrated by our reviewed studies.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 35501_Appendix_1 for The Role of Resistance Training Dosing on Pain and Physical Function in Individuals With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review by Meredith N. Turner, Daniel O. Hernandez, William Cade, Christopher P. Emerson, John Reynolds and Thomas M. Best in Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach

Supplemental material, 35501_Appendix_2 for The Role of Resistance Training Dosing on Pain and Physical Function in Individuals With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review by Meredith N. Turner, Daniel O. Hernandez, William Cade, Christopher P. Emerson, John Reynolds and Thomas M. Best in Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach

Footnotes

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest in the development and publication of this article.

References

- 1. Baker KR, Nelson ME, Felson DT, Layne JE, Sarno R, Roubenoff R. The efficacy of home based progressive strength training in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1655-1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bennell KL, Hunt MA, Wrigley TV, et al. Hip strengthening reduces symptoms but not knee load in people with medial knee osteoarthritis and varus malalignment: a randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:621-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, et al. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2012;1:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults—United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:421-426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chaipinyo K, Karoonsupcharoen O. No difference between home-based strength training and home-based balance training on pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomised trial. Aust J Physiother. 2009;55:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dell’Isola A, Allan R, Smith SL, Marreiros SS, Steultjens M. Identification of clinical phenotypes in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deveza LA, Melo L, Yamato TP, Mills K, Ravi V, Hunter DJ. Knee osteoarthritis phenotypes and their relevance for outcomes: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25:1926-1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DeVita P, Aaboe J, Bartholdy C, Leonardis JM, Bliddal H, Henriksen M. Quadriceps-strengthening exercise and quadriceps and knee biomechanics during walking in knee osteoarthritis: a two-centre randomized controlled trial. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2018;59:199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, Hirsch R. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991-94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271-2279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ettinger WH, Jr, Burns R, Messier SP, et al. A randomized trial comparing aerobic exercise and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. The Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST). JAMA. 1997;277:25-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Foroughi N, Smith RM, Lange AK, Baker MK, Fiatarone Singh MA, Vanwanseele B. Lower limb muscle strengthening does not change frontal plane moments in women with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2011;26:167-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD004376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:D5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Barbour KE, Theis KA, Boring MA. Updated projected prevalence of self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation among US adults, 2015-2040. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1582-1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jan MH, Lin JJ, Liau JJ, Lin YF, Lin DH. Investigation of clinical effects of high- and low-resistance training for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2008;88:427-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jorge RT, Souza MC, Chiari A, et al. Progressive resistance exercise in women with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29:234-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Juhl C, Christensen R, Roos EM, Zhang W, Lund H. Impact of exercise type and dose on pain and disability in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:622-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lange AK, Vanwanseele B, Fiatarone Singh MA. Strength training for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1488-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J; Cochrane Information Retrieval Methods Group. Chapter 6: Searching for studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S. eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Vol 51.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin DH, Lin CH, Lin YF, Jan MH. Efficacy of 2 non-weight-bearing interventions, proprioception training versus strength training, for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:450-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McKnight PE, Kasle S, Going S, et al. A comparison of strength training, self-management, and the combination for early osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:45-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mikesky AE, Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, Perkins SM, Damush T, Lane KA. Effects of strength training on the incidence and progression of knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:690-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:C869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rogers MW, Tamulevicius N, Semple SJ, Krkeljas Z. Efficacy of home-based kinesthesia, balance & agility exercise training among persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. J Sports Sci Med. 2012;11:751-758. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schilke JM, Johnson GO, Housh TJ, O’Dell JR. Effects of muscle-strength training on the functional status of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee joint. Nurs Res. 1996;45:68-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Topp R, Woolley S, Hornyak J, 3rd, Khuder S, Kahaleh B. The effect of dynamic versus isometric resistance training on pain and functioning among adults with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1187-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zacharias A, Green RA, Semciw AI, Kingsley MI, Pizzari T. Efficacy of rehabilitation programs for improving muscle strength in people with hip or knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22:1752-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:476-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, 35501_Appendix_1 for The Role of Resistance Training Dosing on Pain and Physical Function in Individuals With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review by Meredith N. Turner, Daniel O. Hernandez, William Cade, Christopher P. Emerson, John Reynolds and Thomas M. Best in Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach

Supplemental material, 35501_Appendix_2 for The Role of Resistance Training Dosing on Pain and Physical Function in Individuals With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review by Meredith N. Turner, Daniel O. Hernandez, William Cade, Christopher P. Emerson, John Reynolds and Thomas M. Best in Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach