Abstract

Context:

Cannabis use has increased, in large part due to decriminalization. Despite this increase in usage, it remains unclear what proportion of athletes use cannabis and what effect it has on athletic performance and recovery.

Objective:

To systematically review cannabis use among athletes, including epidemiology, effect on performance and recovery, and regulations for use in sport.

Data Sources:

PubMed, MEDLINE, and EMBASE databases were queried from database inception through November 15, 2018. A hand search of policies, official documents, and media reports was performed for relevant information.

Study Selection:

All studies related to cannabis use in athletes, including impact on athletic performance or recovery, were included.

Study Design:

Systematic review.

Level of Evidence:

Level 4.

Data Extraction:

Demographic and descriptive data of included studies relating to epidemiology of cannabis use in athletes were extracted and presented in weighted means or percentages where applicable.

Results:

Overall, 37 studies were included, of which the majority were cross-sectional studies of elite and university athletes. Among 11 studies reporting use among athletes (n = 46,202), approximately 23.4% of respondents reported using cannabis in the past 12 months. Two studies found a negative impact on performance, while another 2 studies found no impact. There was no literature on the influence of cannabis on athletic recovery. Across athletic organizations and leagues, there is considerable variability in acceptable thresholds for urine tetrahydrocannabinol levels (>15 to 150 ng/mL) and penalties for athletes found to be above these accepted thresholds.

Conclusion:

Overall, these results suggest that approximately 1 in 4 athletes report using cannabis within the past year. Based on the available evidence, cannabis does not appear to positively affect performance, but the literature surrounding this is generally poor. Given the variability in regulation across different sport types and competition levels, as well as the growing number of states legalizing recreational cannabis use, there is a need to improve our understanding of the effects of cannabis use on the athlete and perhaps adopt a clearer and overarching policy for the use of cannabis by athletes in all sports and at all levels.

Keywords: cannabis, athletes, sports, performance, recovery

Cannabis is commonly used for recreational or medicinal purposes. While there are more than 104 different compounds in cannabis, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) are the most well-known, researched, and consumed.7 THC is the main psychoactive component and has garnered attention because of its ability to act as a partial agonist for CB1 and CB2 receptors, leading to the intoxicating effects that many recreational users seek. Alternatively, CBD elicits pharmacological effects devoid of psychoactivity, making it ideal for medicinal use because of its limited impact on the central nervous system and its reported antiepileptic, anxiolytic, antipsychotic, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects.7,43

In North America, cannabis use in adults has increased over the past decade largely because of changing attitudes regarding its harm, use, and acceptability.2,49 Most recently, Canada and many states in the United States (US) have legalized the recreational use of cannabis, reflecting the shifting public opinion. There is an interest in understanding how these changes will influence sport, from the individual athlete to how different sporting organizations will adopt regulations keeping with or against these trends. The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the available literature on cannabis use in sport, specifically (1) the epidemiology of cannabis use among athletes, (2) the impact of cannabis use on athletic performance and recovery, and (3) the current regulations surrounding the use of cannabis and sport participation.

Methods

Search Strategy

Three online databases (PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE) were searched by 2 independent reviewers in duplicate for relevant articles from data inception to November 15, 2018. Search terms such as sports, athletes, exercise, cannabis, marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol, performance enhancement, and athletic performance were utilized. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) for MEDLINE and EMTREE terms for EMBASE were utilized in various combinations and supplemented with free text to increase search sensitivity. A hand search of up-to-date policies, official documents, and media reports was also performed on November 15, 2018. The search strategy can be found in Appendix 1 (available in the online version of this article).

Study Screening

All titles, abstracts, and full texts were screened in duplicate by 2 independent reviewers. Any disagreements at the title and abstract stages were moved forward to the next round of screening to ensure relevant articles were not missed. Disagreements at the full-text stage were discussed among the 2 reviewers. Consensus was reached for final eligibility of all articles.

Assessment of Study Eligibility

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for this systematic review were determined a priori. Inclusion criteria were studies (1) in English, (2) on humans, (3) pertaining to the use of cannabis by athletes, and (4) pertaining to the effects of cannabis on performance. Exclusion criteria consisted of systematic or narrative reviews and nonclinical studies.

Data Abstraction and Statistical Analysis

Data relating to the epidemiology of cannabis use among athletes were abstracted from the included studies. Demographic data were also abstracted, including author, year of publication, study type, level of sport, mean age, and percentage female. Descriptive statistics are presented in weighted means or percentages where applicable. A kappa (κ) statistic was used to evaluate interreviewer agreement at all screening stages. Agreement was categorized as per the guidelines of Landis and Koch as follows: 0.81 to 0.99, almost perfect agreement; 0.61 to 0.80, substantial agreement; 0.41 to 0.60, moderate agreement; 0.21 to 0.40, fair agreement; and 0.20 or less, slight agreement.28 Other major recurrent themes found in the literature relating to cannabis use in athletes are summarized under various subheadings. Important and relevant topics to be included in the review were decided on by all authors.

Results

Study Identification

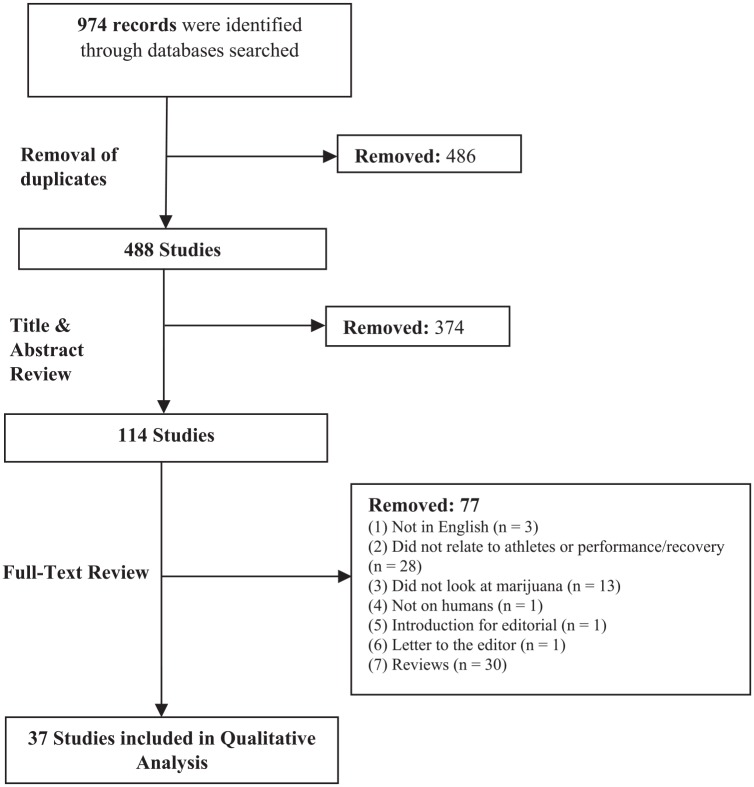

The initial search yielded 974 studies, of which 37 full-text articles met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). There was almost perfect agreement between reviewers at the title and abstract (κ = 0.96) and full-text screening stages (κ = 0.94). Of the 37 studies, we categorized them into studies looking at epidemiology of use, athletic performance, and recovery. In studies looking at use, the majority were level 4 studies of high school, elite, and university-level athletes, including 31 cross-sectional studies and 2 longitudinal survey studies. Among the studies examining athletic performance, 2 randomized control trials and 2 prospective cohort studies were found. No studies were found for the topic of cannabis use and athletic recovery.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram.

Epidemiology of Use

Of the 33 studies evaluating the epidemiology of use, 26 studies reported on the prevalence of self-reported cannabis use in athletes at various levels of sport (Table 1). The majority of studies did not specify route of administration, but among those that did, inhaled and edible forms remain the most common.22,63 The age range among these studies was 13 to 48 years, and level of sport ranged from high school to elite athletes. Eleven studies (n = 46,202) reported on use over the past 12 months. Among these studies, the pooled weighted frequency of cannabis use within the past year was 23.4% (range, 2.5% to 62%). Use in past 6 months (3 studies; n = 6800) or 30 days (2 studies; n = 3248) ranged from 5% to 19% and 11.2% to 32.7%, respectively (Table 1). There was significant variability in the frequency of use reported between studies evaluating marijuana use, where some considered use as 1 joint smoked in their life21,33,42,58,71 and others reported daily and weekly use,27 which could explain the wide ranges in values.

Table 1.

Studies that reported on the frequency of self-reported marijuana use among athletes (n = 26)

| Study, Year | Type of Study | Level of Sport | Participants (N) | Age, y, Mean (SD) or Range | Female, % | Self-reported Marijuana Use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have Used ≥1 in Lifetime, % | Have Used ≥1 in Past 12 Months, % | Have Used ≥1 in Past 6 Months, % | Have Used ≥1 Time in Past 30 Days, % | ||||||

| Ohaeri et al, 199341 | Cross-sectional | Nigerian professional sportspeople | 250 | 25 | 28 | 0.8 | |||

| Forman et al, 199521 | Cross-sectional | American male high school athletes | 1117 | 14-18 | 0 | 18.5 | |||

| Spence and Guavin, 199652 | Cross-sectional | Canadian university athletes | 754 | NR | 37.4 | 19.8 | |||

| Tricker and Connolly, 199759 | Cross-sectional | NCAA Division I | 562 | NR | NR | 32 | 19 | ||

| Wechsler et al, 199766 | Cross-sectional | American college athletes | 2096 | NR | 38 | 11.2 | |||

| Baumert et al, 19983 | Cross-sectional | American adolescent athletes | 4039 | NR | 42 | 5 | |||

| Green et al, 200123 | Cross-sectional | NCAA Division I, II, and III | 13,914 | NR | 33.9 | 28.4 | |||

| Peretti-Watel et al, 200345 | Cross-sectional | Southeast French elite student-athletes | 458 | 18.3 | 65.3 | 24.2 | |||

| Laure et al, 200430 | Cross-sectional | Eastern French high school athletes | 1459 | 14-18 | 42 | 19 (at least once in the past 2 months) | |||

| Lorente et al, 200533 | Cross-sectional | French departmental, regional, national, and international sport athletes | 1152 | 20.7 | 42.2 | 66.8 | 32.7 | ||

| Laure and Binsinger, 200729 | Cross-sectional | Eastern French high school athletes (4-year follow-up) | 2199 | 11.2 (0.6) | 46.8 | 6.3 | |||

| Thevis et al, 200856 | Cross-sectional | German university athletes | 719 | 22.13 (1.7) | 45.5 | 0 | |||

| Wiefferink et al, 200868 | Cross-sectional | Netherlands gym users | 144 | 32 | 16 | 43 (unspecified) | |||

| Yusko et al, 200874 | Cross-sectional | Varsity and NCAA Division I athletes | 391 | 19.9 | 40.4 | 54.2 | 32.3 | ||

| Wichstrøm and Wichstrøm, 200967 | Longitudinal | Norwegian high school athletes | 1355 | 13-18 | NR | 12.5% (at last follow-up) | |||

| LaBrie et al, 200927 | Cross-sectional | NCAA Division I athletes | 522 | 19.5 (1.27) | NR | 62a | |||

| Zenic et al, 201075 | Cross-sectional | Croatian athletes in amateur, semi-professional, and professional sport | 69 | 18-30+ | 100 | 17 (unspecified) | |||

| Thomas et al, 201157 | Cross-sectional | Elite Australian athletes | 974 | 23 (18-30) | 24.3 | 21 | 3.2 | ||

| Lentillon-Kaestner and Ohl, 201131 | Cross-sectional | French Swiss amateur athletes | 1810 | NR | 45.1 | 9.8 (unspecified) | |||

| Harcourt et al, 201224 | Longitudinal | Australian Football League male athletes | 640 | 23 | 0 | 0% (at last follow up) | |||

| Diehl et al, 201417 | Cross-sectional | German elite adolescent athletes | 1138 | 16.4 | 44 | 2.7 | |||

| Egan et al, 201619 | Cross-sectional | NCAA Division I, II, and III athletes | 3276 | 18-25+ | 48.6 | 2.5 | |||

| NCAA, 201838 | Cross-sectional | NCAA Division I, II, and III athletes | 23,028 | 18-23 | 43.1 | 24.7 | |||

| Davis et al, 201716 | Cross-sectional | NCAA Division III athletes | 173 | 18-22 | 100 | Reported mean 1.27 (SD, 0.86) on Likert scale for 30 day use (1 = never, 7 = 100 or more times) | |||

| Buckman et al, 20119 | Cross-sectional | Undergraduate student-athletes | 392 | 40.1 | 40.1 | 32.3 | |||

| Dunn and Thomas, 201218 | Cross-sectional | Convenience sample of 18 national sporting organizations in Australia | 1684 | 18-48 | 28 | 8 (at least 1 of the 6 illicit drugs: ecstasy, cannabis, cocaine, meth, GHB, or ketamine) b | |||

GHB, γ-hydroxybutyrate; NCAA, National College Athletic Association; NR, not reported; unspecified, unspecified timeline for self-reported marijuana use.

In this study, 9.9% reported using once a month, 12% reported using 2 to 3 times a month, 8.9% reported using between 1 and 6 times a week, and 7.8% reported daily marijuana use.

Study not included in weighted calculation.

The remaining 7 studies reported on either risk factors associated with cannabis use or cannabis frequency in urine samples from doping labs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Main findings from studies on cannabis and risk factors or doping laboratory analysis (n = 7)

| Study, Year | Type of Study | Participants, n | Age Range, y | Female, % | Cohort | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ewing, 199820 | Cross-sectional | 1458 | NR | 46.7 | National Longitudinal Youth Survey (1992) | Male athletes were more likely to have used marijuana than non-athletes. |

| Peretti-Watel et al, 200244 | Cross-sectional | 10,807 | 14-19 | 52.1 | French national school survey of all adolescents (1999) | U-shaped curve was found between male sport participation and cannabis use. |

| Van Eenoo and Delbeke, 200361 | Cross-sectional | 14,995 | NR | 13.4 | Urine samples from the IOC and Flanders analyzed in a doping control laboratory, Ghent, Belgium (1996-2000) | Reports showed a significant increase in samples containing cannabis over time, and it was detected in all types of sports studied. |

| Strano Rossi and Botrè, 201155 | Cross-sectional | 95,000 | 18-35 | 25 | Athlete urine samples taken from the Italian Anti-Doping Laboratory over a 10-year period (2000-2009) | Marijuana (THC metabolite) was the most frequently found drug (0.2%-0.4% of samples). |

| Buckman et al, 20138 | Cross-sectional | 11,559 | 18-23 | 0 | Male undergraduate NCAA college student-athletes (2008-2009) | Reports showed a higher prevalence of marijuana among performance-enhancing substance users compared with nonusers. |

| Veliz et al, 201662 | Cross-sectional | 21,049 | 13-18 | 50.9 | American College Health Association—National College Health Assessment Study (2008-2012) | Participation in competitive sport was not associated with 30-day marijuana use. However, odds of past 30-day use was higher in high-contact sports. |

| Boyes et al, 20176 | Cross-sectional | 13,817 | 14-15 | 49.3 | National Canadian adolescents from the Health Behaviour in School Age Children data (2013-2014) | Team sport participation was associated with lower prevalence levels of cannabis use and a protective effect of cannabis use for females. |

IOC, International Olympic Committee; NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association; NR, not reported; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

Impact on Performance and Recovery

Our search revealed 4 primary studies (n = 121) that examined marijuana use in athletes or otherwise healthy patients and its impact on athletic performance.32,34,47,54 In terms of a negative effect on performance, Steadward and Singh54 found that heart rate and blood pressure were elevated after marijuana consumption when compared with placebo during exercise, and work capacity decreased 25% at a heart rate of 170 bpm. When observing maximal exercise, Renaud and Cormier47 reported a decrease in maximal work duration as a result of leg fatigue in patients who smoked a cigarette of THC 17 minutes before exercising. In contrast, a recent study by Lisano et al32 comparing exercise performance in marijuana users with nonusers found no significant between-group differences in cardiovascular function or performance. Similarly, in a study by Maksud and Baron34 evaluating marijuana users versus control, no significant differences were found between groups on peak aerobic capacity or physical work capacity. No studies reported on cannabis and the impact on recovery.

Regulations in Sport

A hand search of up-to-date regulations for the use of cannabis in major sporting organizations was conducted. Our findings revealed that cannabis regulations vary widely among sporting organizations, as delineated in Table 3. As the active substance in cannabis, THC, is metabolized into carboxy-THC and excreted in urine, the most common way of testing cannabis use in athletes is through urinalysis.

Table 3.

Regulations of cannabis use in major sporting organizations

| Organization | Year of Policy | Policy | Discipline Schedule | Frequency of Testing | Analysis Tested | Threshold Levels of Carboxy-THC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFL | 2018 | Prohibited39 | 1st violation: Substance abuse program 2nd violation: Fine of 3 game pay 3rd violation: Fine of 2 game pay 4th violation: Suspension for 4 games 5th violation: Suspension for 10 games 6th violation: Suspension for 1 year |

All players tested once during preseason, random testing in-season if permitted in contract | Urine | ≥35 ng/mL |

| NBA | 2017 | Prohibited35 | 1st violation: Entrance into “Marijuana Program” 2nd violation: $25,000 fine 3rd violation: 5-game suspension 4th violation: 10-game suspension |

Random testing (up to 4 times per regular season) | Urine | NA |

| NHL | 2016 | Prohibited list not publicly available | Abnormally high levels for drugs of abuse: Player contacted and referred to NHL/NHLA Substance Abuse and Behavioral Health Program | Random testing | NA | NA |

| MLB | 2018 | Prohibited15 | 1st violation: Treatment program Incompliance of treatment program: progressive fines up to $35,000 Threatening levels of marijuana: discipline by commissioner |

Must have reasonable cause for testing during regular season | Urine | >18 ng/mL |

| MLS | 2016 | NA | Not specified in CBA13 | NA | NA | NA |

| Olympics (WADA) | 2018 | Prohibited in competition72 | Antidoping rule violation leads to disqualification of the results obtained during the competition in question73 | Random testing | Urine | >150 ng/mL71 |

| NCAA | 2018 | Prohibited37 | 1st penalty: Student withheld from competition for 50% of

the season 2nd penalty: Loss of eligible year and withheld from participation for 1 year posttest, negative test required to reinstate eligibility36 |

Random testing or basis of position, ranking, playing time, financial aid status | Urine | >15 ng/mL |

| National standardsa | 2018 | Prohibited in competition11 | Canadian Anti-Doping Program b : Usually 2-month ineligibility10 | Random testing | Urine | >150 ng/mL |

| 2018 | Prohibited in competition60 | US Anti-Doping Agency b : Usually 6-month suspension with 3-month deferral60 | Random testing | Urine | >150 ng/mL |

CBA, Collective Bargaining Agreement; MLB, Major League Baseball; MLS, Major League Soccer; NA, not available; NBA, National Basketball Association; NCAA, National College Athletic Association; NFL, National Football League; NHL, National Hockey League; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol; WADA, World Anti-Doping Agency.

May include other professional- and amateur-level sports.

Adopts the WADA prohibited list, rules only applicable to organizations that enact these antidoping programs.

Discussion

Epidemiology of Use

Overall, 23.4% of athletes reported using cannabis within the past year. Despite this higher-than-anticipated rate of use, these findings are lower than the rate of use in the general population among similarly aged individuals (31.9% in a cohort aged 18-25 years2). One consideration is that the current studies examining cannabis use among athletes were all reliant on athlete self-reporting, which could lead to underreporting for a variety of reasons, including fear of stigma and punishment.64 For instance, in a study by Thevis et al,56 no athletes reported cannabis use, yet 9.8% of urine samples from the same cohort detected THC levels at concentrations indicative of use within the past 24 hours. Similarly, Saugy et al50 suggested that athletes who consume cannabis typically restrict themselves to low doses and consume outside the environment of doctors, coaches, and teammates. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has conducted a Student-Athlete Drug Use Survey every 4 years since 1985 that enables an assessment of health and well-being of student-athletes.38,53 Their most recent survey found that 24.7% of athletes reported using marijuana within the past 12 months.38 On the other hand, a study by Peretti-Watel et al45 found that the use of cannabis was 2 to 3 times lower among elite student-athletes than their nonathlete counterparts, and Baumert et al3 found nonathletes to be at a greater likelihood of using marijuana. Despite this, it is clear that a number of athletes we care for may be using cannabis. In areas where cannabis is legal, education on safe use, in- versus out-of-season use, and information regarding its effects on health and performance should be a priority for the medical staff and other team personnel.

Impact on Performance and Recovery

While it is clear that a lack of strong evidence exists to make definitive conclusions on the association between cannabis use and athletic performance, it is worth noting that among 4 studies, there was no clearly demonstrated benefit of cannabis use on athletic performance32,34,47,54; in fact, 2 studies47,54 demonstrated that cannabis use negatively influenced performance on noncontact cycle ergometer exercises. This is consistent with the pharmacological effects, which categorize it as an ergolytic substance rather than ergogenic.50

Although there is no evidence of improvements in physical performance, alterations in cognition and affect have been postulated to affect performance due to the euphoric feelings after use, which may have stress- and anxiety-relieving effects in a competitive setting.25,45 THC has anxiolytic effects at low doses, which may lead athletes to it use for anxiety relief before, during, and after performance.5,25,50 Three studies revealed reasons athletes used cannabis.23,33,57 In a study using NCAA data from 2001, Green et al23 found that only 0.6% of athletes reported using cannabis to enhance athletic performance. Lorente et al33 found that 85.7% of athletes reported that the drug was never used to enhance performance, while Thomas et al56 found that the majority believed it would negatively affect their performance. On the other hand, athletes also cited psychological factors such as increased relaxation, pleasure, and improved sleep,33,50 factors that could be perceived to also affect performance. It is important to note that these potential benefits of cannabis are primarily from self-reports; as such, future research should focus on better understanding how cannabis influences the mental state of an athlete, specifically its role in managing anxiety associated with participation in sport.

While there is no data on the role of cannabis in athletic recovery, some have pointed to its potential role. Cannabis may play a role in pain management after injury and training fatigue because of its analgesic effects.64 There is considerable literature that suggests cannabinoids have a moderate positive effect in managing neuropathic pain.7 Medicinal marijuana has been approved in many states for a number of conditions, including severe chronic pain,7 and it is well-known that many current and former athletes suffer from chronic pain. Furthermore, benefits may also serve Paralympic athletes, who suffer from neuropathic pain related to spinal cord injury or muscle spasticity.64 In a study examining chronic neuropathic pain, a single inhalation of 25 milligrams 3 times daily for 5 days reduced pain intensity and improved sleep.65 In a narrative review published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, medicinal cannabis producers are hopeful that it may serve as a safer alternative to pharmaceutical-based pain management.14 Former National Football League (NFL) players are advocating for the legalization of cannabis, citing that it may help with the chronic pain and opioid addiction that accompany years of injuries sustained in the contact sport.14,69

One interesting consideration in the discussion of cannabis use among athletes is its impact on concussion recovery. The risk of concussion has been a concerning and harrowing reality of many contact sports. In particular, the rates of sport-related concussions have grown significantly in youth.1 The recovery from concussion can be a long and arduous one, depending on the severity, and may leave the athlete with a lost sense of self and isolation.12,26 No studies to date have tested cannabis use and concussion recovery. In a retrospective study by Nguyen et al,40 a positive correlation was found between THC use and improved survival after traumatic brain injury, not specific to concussion. In a narrative review by Schurman and Lichtman,51 a pharmacological analysis of endocannabinoids and their relation to traumatic brain injury pathology suggests a promising avenue of basic science research to explore the neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory characteristics, which could have potential therapeutic benefits in concussion management.

Regulation in Sport

There is clear variability across different sports and competition levels with regard to the acceptability of cannabis use in and outside of competition. While some have discernibly defined sanctions on THC-positive athletes, such as the NFL and National Basketball Association, others like the National Hockey League (NHL) have little discipline for athletes who use THC.48 There is also notable variability in the acceptable level of THC at the time of testing, whereby the NCAA appears the harshest (where the urine threshold levels of THC exceed >15 ng/mL),37 yet a much larger >150 ng/mL threshold is held by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), which regulates the Olympics, the Canadian Anti-Doping Policy, and the US Anti-Doping Agency.71 Another noteworthy finding is that the WADA only prohibits cannabis use “in competition,” which means athletes may be using outside of competition time without penalty from their sporting organization.25,46 Furthermore, in the NCAA, for example, the testing and penalties for marijuana may vary greatly between colleges given that the majority also conduct their own institutional drug testing independent of the NCAA and are then responsible for applicable penalties.36 In contrast, in professional organizations such as the Major League Baseball, the NHL, the NFL, and Major League Soccer, leagues oversee and enact punishments. At the national level, it is the choice of individual sporting organizations to adopt standards such as the Canadian Anti-Doping Program or US Anti-Doping Agency, who then provide code-compliant antidoping services.11 Last, it is important to note that regulations in sport largely focus on the consumption of THC, while CBD appears to be widely accepted. For example, the WADA permits the use of CBD.55 Despite this, athletes should recognize the inherent risk in consuming what is perceived to be pure hemp-derived CBD (legally considered to have THC levels <0.3%).70 Literature suggests that there is wide variability in the purity of CBD products, and consumers have little quality guarantees when it comes to the numerous oils on the market.42 Given this variability, it is possible that THC levels in reportedly pure CBD products can reach a level that may result in a positive urine test depending on the threshold for the sport and competition level that the athlete is participating in.

Despite all the variability in regulations surrounding cannabis use in sport, the debate of whether cannabis is considered “doping” remains. In a commentary by Bergamaschi and Crippa,4 they detail the 3 inclusion criteria for a substance to be included in the prohibited list by the WADA: (1) potential to enhance performance, (2) imposes health risks, and (3) violates the spirit of sport. Whether cannabis meets these criteria and how remain in question with the changing landscape of sport and available evidence. With the decriminalization in Canada and some US states, athletes and league administrators may be deliberating the presence of cannabis on prohibited substance lists.

Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review is the first to outline and summarize the available literature on cannabis use in athletes, providing an overview of both the epidemiology of use and the impact cannabis has on athletic performance and recovery. It identifies numerous voids in the available literature and areas where further research can aid in our understanding of the effect of cannabis on athletes. Our review is limited to the strength of evidence available on this topic, which was primarily level 4 and 5 evidence. Another limitation is that pooled analysis on usage may be under- or overestimated because of the wide variability among studies on factors including level and type of sport, athlete age, and year of study. Some other considerations we did not detail include dosage and potency of marijuana and how the alterations in dose may influence performance. Last, “cannabis use” is a common umbrella term that encapsulates both THC and CBD, though the studies in this review and others have historically focused on THC use. The legalization of cannabis has given rise to CBD-related product use, and we suspect that CBD use among athletes has also risen exponentially. Given our findings on the growing use of cannabis overall, it is worthwhile to relay the dire need to researchers to study the prevalence of use and effects of CBD in the athletic population.

Conclusion

Overall, approximately 1 in 4 athletes reported using cannabis in the past year, but this may be underreported. Cannabis use is thought to either have no benefit or to impair athletic performance, as indicated in the available low-level evidence; moreover, there is no evidence evaluating the impact of cannabis on recovery. Current regulations in sport show that most organizations have prohibited cannabis, but discipline schedules and THC urine levels vary by organization. As the legal landscape and acceptability of cannabis use is changing, further research is needed to delineate its true effects on performance and recovery and to guide its regulation in sport.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_1 for Cannabis Use and Sport: A Systematic Review by Shgufta Docter, Moin Khan, Chetan Gohal, Bheeshma Ravi, Mohit Bhandari, Rajiv Gandhi and Timothy Leroux in Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach

Footnotes

The following authors declared potential conflicts of interest: M.B. is a paid consultant for AgNovos Healthcare, Sanofi Aventis, Smith & Nephew, and Stryker and has received grant support from DJ Orthopedics. R.G. has received divisional research support from Smith & Nephew and Zimmer-Biomet.

References

- 1. Amoo-Achampong K, Rosas S, Schmoke N, Accilien Y-D, Nwachukwu BU, McCormick F. Trends in sports-related concussion diagnoses in the USA: a population-based analysis using a private-payor database. Phys Sportsmed. 2017;45:239-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azofeifa A, Mattson ME, Schauer G, McAfee T, Grant A, Lyerla R. National estimates of marijuana use and related indicators—National Survey on Drug Use and Health, United States, 2002–2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(11):1-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baumert PW, Henderson JM, Thompson NJ. Health risk behaviors of adolescent participants in organized sports. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:460-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bergamaschi MM, Crippa JAS. Why should cannabis be considered doping in sports? Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berrendero F, Maldonado R. Involvement of the opioid system in the anxiolytic-like effects induced by Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2002;163:111-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boyes R, O’Sullivan DE, Linden B, McIsaac M, Pickett W. Gender-specific associations between involvement in team sport culture and Canadian adolescents’ substance-use behavior. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:663-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bridgeman MB, Abazia DT. Medicinal cannabis: history, pharmacology, and implications for the acute care setting. P T. 2017;42:180-188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buckman JF, Farris SG, Yusko DA. A national study of substance use behaviors among NCAA male athletes who use banned performance enhancing substances. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131:50-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buckman JF, Yusko DA, Farris SG, White HR, Pandina RJ. Risk of marijuana use in male and female college student athletes and nonathletes. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:586-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Canadian Anti-Doping Agency Sanctions. 2018-2017. https://www.cces.ca/sites/default/files/content/docs/pdf/cces-mr-2017-2018details-e.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2018.

- 11. Canadian Anti-Doping Program. September 2017. https://cces.ca/sites/default/files/content/docs/pdf/cces-policy-cadp-2015-v2-e.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- 12. Cole WR, Bailie JM. Neurocognitive and psychiatric symptoms following mild traumatic brain injury. In: Laskowitz D, Grant G, eds. Translational Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (Frontiers in Neuroscience). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group; 2016:379-394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Collective Bargaining Agreement between Major League Soccer and Major League Soccer Players Union. February 2015. https://s3.amazonaws.com/mlspa/Collective-Bargaining-Agreement-February-1-2015.pdf?mtime=20180213190926. Accessed December 1, 2018.

- 14. Collier R. A place for pot in sports? CMAJ. 2017;189:e448-e449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Commissioner of Baseball, Major League Baseball Players Association. Major League Baseball’s Joint Drug Prevention and Treatment Program. 2021. http://www.mlb.com/pa/pdf/jda.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- 16. Davis AN, Carlo G, Hardy SA, Olthuis JV, Zamboanga BL. Bidirectional relations between different forms of prosocial behaviors and substance use among female college student athletes. J Soc Psychol. 2017;157:645-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Diehl K, Thiel A, Zipfel S, Mayer J, Schneider S. Substance use among elite adolescent athletes: findings from the GOAL Study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24:250-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dunn M, Thomas JO. A risk profile of elite Australian athletes who use illicit drugs. Addict Behav. 2012;37:144-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Egan KL, Erausquin JT, Milroy JJ, Wyrick DL. Synthetic cannabinoid use and descriptive norms among collegiate student-athletes. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2016;48:166-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ewing BT. High school athletes and marijuana use. J Drug Educ. 1998;28:147-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Forman ES, Dekker AH, Javors JR, Davison DT. High-risk behaviors in teenage male athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 1995;5:36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Friese B, Slater MD, Annechino R, Battle RS. Teen use of marijuana edibles: a focus group study of an emerging issue. J Prim Prev. 2016;37:303-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Green GA, Uryasz FD, Petr TA, Bray CD. NCAA study of substance use and abuse habits of college student-athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2001;11:51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harcourt PR, Unglik H, Cook JL. A strategy to reduce illicit drug use is effective in elite Australian football. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:943-945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huestis MA, Mazzoni I, Rabin O. Cannabis in sport: anti-doping perspective. Sports Med. 2011;41:949-966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kontos AP, Collins M, Russo SA. An introduction to sports concussion for the sport psychology consultant. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2004;16:220-235. [Google Scholar]

- 27. LaBrie JW, Grossbard JR, Hummer JF. Normative misperceptions and marijuana use among male and female college athletes. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2009;21(suppl 1):S77-S85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Laure P, Binsinger C. Doping prevalence among preadolescent athletes: a 4-year follow-up. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(10):660-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Laure P, Lecerf T, Friser A, Binsinger C. Drugs, recreational drug use and attitudes towards doping of high school athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2004;25:133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lentillon-Kaestner V, Ohl F. Can we measure accurately the prevalence of doping? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21:e132-e142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lisano JK, Smith JD, Mathias AB, et al. Performance and health related characteristics of male athletes using marijuana. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33:1658-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lorente FO, Peretti-Watel P, Grelot L. Cannabis use to enhance sportive and non-sportive performances among French sport students. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1382-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maksud MG, Baron A. Physiological responses to exercise in chronic cigarette and marijuana users. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1980;43:127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. National Basketball Association. NBA Collective Bargaining Agreement. 2017. https://official.nba.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2017/12/2017-18-CBA-101-December-2017.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2018.

- 36. National Collegiate Athletic Association. Frequently asked questions about drug testing. http://www.ncaa.org/sport-science-institute/topics/frequently-asked-questions-about-drug-testing. Accessed December 1, 2018.

- 37. National Collegiate Athletic Association. NCAA banned drugs. 2018-2019. http://www.ncaa.org/sites/default/files/2018-19NCAA_Banned_Drugs_20180608.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- 38. National Collegiate Athletic Association. NCAA Student-Athlete Substance Use Study. June 2018. http://www.ncaa.org/sites/default/files/2018RES_Substance_Use_Final_Report_FINAL_20180611.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2018.

- 39. National Football League Players Association, National Football League Management Council. National Football League policy and program on substances of abuse. 2018. https://nflpaweb.blob.core.windows.net/media/Default/PDFs/2018%20Policy%20and%20Program%20on%20Substances%20of%20Abuse.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- 40. Nguyen BM, Kim D, Bricker S, et al. Effect of marijuana use on outcomes in traumatic brain injury. Am Surg. 2014;80:979-983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ohaeri JU, Ikpeme E, Ikwuagwu PU, Zamani A, Odejide OA. Use and awareness of effects of anabolic steroids and psychoactive substances among a cohort of Nigerian professional sports men and women. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 1993;8:429-432. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pavlovic R, Nenna G, Calvi L, et al. Quality traits of “cannabidiol oils”: cannabinoids content, terpene fingerprint and oxidation stability of European commercially available preparations. Molecules. 2018;23:1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pellati F, Borgonetti V, Brighenti V, Biagi M, Benvenuti S, Corsi L. Cannabis sativa L. and nonpsychoactive cannabinoids: their chemistry and role against oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Peretti-Watel P, Beck F, Legleye S. Beyond the U-curve: the relationship between sport and alcohol, cigarette and cannabis use in adolescents. Addiction. 2002;97:707-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Peretti-Watel P, Guagliardo V, Verger P, Pruvost J, Mignon P, Obadia Y. Sporting activity and drug use: alcohol, cigarette and cannabis use among elite student athletes. Addiction. 2003;98:1249-1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pesta DH, Angadi SS, Burtscher M, Roberts CK. The effects of caffeine, nicotine, ethanol, and tetrahydrocannabinol on exercise performance. Nutr Metab. 2013;10:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Renaud AM, Cormier Y. Acute effects of marihuana smoking on maximal exercise performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1986;18:685-689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Robson D. Should the NHL change its approach to marijuana after legalization? Maclean’s. https://www.macleans.ca/society/should-the-nhl-change-its-policy-on-marijuana-after-legalization/. Published November 25, 2017. Accessed November 9, 2018.

- 49. Rotermann M, Macdonald R. Analysis of trends in the prevalence of cannabis use in Canada, 1985 to 2015. 2018. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2018002/article/54908-eng.htm. Accessed December 1, 2018. [PubMed]

- 50. Saugy M, Avois L, Saudan C, et al. Cannabis and sport. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(suppl 1):i13-i15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schurman LD, Lichtman AH. Endocannabinoids: a promising impact for traumatic brain injury. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Spence JC, Gauvin L. Drug and alcohol use by Canadian university athletes: a national survey. J Drug Educ. 1996;26:275-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sport Science Institute, NCAA. Mind, body and sport: substance use and abuse. http://www.ncaa.org/sport-science-institute/mind-body-and-sport-substance-use-and-abuse. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- 54. Steadward RD, Singh M. The effects of smoking marihuana on physical performance. Med Sci Sports. 1975;7:309-311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Strano Rossi S, Botrè F. Prevalence of illicit drug use among the Italian athlete population with special attention on drugs of abuse: a 10-year review. J Sports Sci. 2011;29:471-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Thevis M, Sauer M, Geyer H, Sigmund G, Mareck U, Schänzer W. Determination of the prevalence of anabolic steroids, stimulants, and selected drugs subject to doping controls among elite sport students using analytical chemistry. J Sports Sci. 2008;26:1059-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Thomas JO, Dunn M, Swift W, Burns L. Elite athletes’ perceptions of the effects of illicit drug use on athletic performance. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20:189-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thomas JO, Dunn M, Swift W, Burns L. Illicit drug knowledge and information-seeking behaviours among elite athletes. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14:278-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tricker R, Connolly D. Drugs and the college athlete: an analysis of the attitudes of student athletes at risk. J Drug Educ. 1997;27:105-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. US Anti-Doping Agency Sanctions. 2018. https://www.usada.org/testing/results/sanctions/. Accessed November 9, 2018.

- 61. Van Eenoo P, Delbeke FT. The prevalence of doping in Flanders in comparison to the prevalence of doping in international sports. Int J Sports Med. 2003;24:565-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Veliz P, Epstein-Ngo Q, Zdroik J, Boyd CJ, McCabe SE. Substance use among sexual minority collegiate athletes: a national study. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51:517-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SRB. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2219-2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ware MA, Jensen D, Barrette A, Vernec A, Derman W. Cannabis and the health and performance of the elite athlete. Clin J Sport Med. 2018;28:480-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ware MA, Wang T, Shapiro S, et al. Smoked cannabis for chronic neuropathic pain: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2010;182:e694-e701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wechsler H, Davenport AE, Dowdall GW, Grossman SJ, Zanakos SI. Binge drinking, tobacco, and illicit drug use and involvement in college athletics. A survey of students at 140 American colleges. J Am Coll Health. 1997;45:195-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wichstrøm T, Wichstrøm L. Does sports participation during adolescence prevent later alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use? Addiction. 2009;104:138-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wiefferink CH, Detmar SB, Coumans B, Vogels T, Paulussen TGW. Social psychological determinants of the use of performance-enhancing drugs by gym users. Health Educ Res. 2008;23:70-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Woodhams SG, Sagar DR, Burston JJ, Chapman V. The role of the endocannabinoid system in pain. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;227:119-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. World Anti-Doping Agency. Athletes: 6 Things to Know About Cannabidiol. October 2018. https://www.usada.org/spirit-of-sport/education/six-things-know-about-cannabidiol/. Accessed November 9, 2018.

- 71. World Anti-Doping Agency. New threshold levels on cannabis. May 2013. https://www.wada-ama.org/en/media/news/2013-05/new-threshold-level-for-cannabis. Accessed November 9, 2018.

- 72. World Anti-Doping Agency. The World Anti-Doping Code International Standard Prohibited List. 2019. https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/wada_2019_english_prohibited_list.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2018.

- 73. World Anti-Doping Agency. World Anti-Doping Code 2015 with 2018 amendments.; 2018. https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada_anti-doping_code_2018_english_final.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2018.

- 74. Yusko DA, Buckman JF, White HR, Pandina RJ. Alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs, and performance enhancers: a comparison of use by college student athletes and nonathletes. J Am Coll Health. 2008;57:281-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zenic N, Peric M, Zubcevic NG, Ostojic Z, Ostojic L. Comparative analysis of substance use in ballet, dance sport, and synchronized swimming: results of a longitudinal study. Med Probl Perform Art. 2010;25:75-81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Appendix_1 for Cannabis Use and Sport: A Systematic Review by Shgufta Docter, Moin Khan, Chetan Gohal, Bheeshma Ravi, Mohit Bhandari, Rajiv Gandhi and Timothy Leroux in Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach