Abstract

Context:

Recent studies examining return to sport after traumatic shoulder instability suggest faster return-to-sport time lines after bony stabilization when compared with soft tissue stabilization. The purpose of the current study was to define variability across online Latarjet rehabilitation protocols and to compare Latarjet with Bankart repair rehabilitation time lines.

Evidence Acquisition:

Online searches were utilized to identify publicly available rehabilitation protocols from Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited academic orthopaedic surgery programs.

Study Design:

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Level of Evidence:

Level 3.

Results:

Of the 183 ACGME-accredited orthopaedic programs reviewed, 14 institutions (7.65%) had publicly available rehabilitation protocols. A web-based search yielded 17 additional protocols from private sports medicine practices. Of the 31 protocols included, 31 (100%) recommended postoperative sling use and 26 (84%) recommended elbow, wrist, and hand range of motion exercises. Full passive forward flexion goals averaged 3.22 ± 2.38 weeks postoperatively, active range of motion began on average at 5.22 ± 1.28 weeks, and normal scapulothoracic motion by 9.26 ± 4.8 weeks postoperatively. Twenty (65%) protocols provided specific recommendations for return to nonoverhead sport–specific activities, beginning at an average of 17 ± 2.8 weeks postoperatively. This was compared with overhead sports or throwing activities, for which 18 (58%) of protocols recommended beginning at a similar average of 17.1 ± 3.3 weeks.

Conclusion:

Similar to Bankart repair protocols, Latarjet rehabilitation protocols contain a high degree of variability with regard to exercises and motion goal recommendations. However, many milestones and start dates occur earlier in Latarjet protocols when compared with Bankart-specific protocols. Consequently, variability in the timing of rehabilitation goals may contribute to earlier return to play metrics identified in the broader literature for the Latarjet procedure when compared with arthroscopic Bankart repair.

Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT):

Level C.

Keywords: Latarjet, Bankart, rehabilitation, return to sport, shoulder instability

Traumatic anterior shoulder instability is a frequent and disabling condition that affects young athletes and active patients.3,6 Given that shoulder instability most often occurs in patients involved in high-demand impact activities, recurrent instability occurs in up to 90% of patients who experience a primary instability event before the age of 20 years.12 In order to restore glenohumeral joint stability, many patients undergo surgical stabilization to reduce the risk of further instability events. Although arthroscopic Bankart repair remains the gold standard in surgical shoulder stabilization, more emphasis has been placed on quantifying glenohumeral bone defects on preoperative imaging due to increased rates of failure of soft tissue repair and recurrent instability.2,7,13 With increasing knowledge and recognition of bone loss in treating anterior shoulder instability, there has been a noted increase in the number of bone-block stabilization procedures being performed for the treatment of shoulder instability in the United States.6,9

Regardless of the technique or strategy used to treat anterior shoulder instability, the role of postoperative rehabilitation is critical in achieving functional stability and appropriate return to activity.4,5,8 Nonetheless, there is a paucity of high-quality evidence investigating the effect of rehabilitation programs on functional outcomes after both arthroscopic and open stabilization procedures. Furthermore, while The American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Therapists has published a consensus rehabilitation guideline for anterior arthroscopic capsulolabral repair of the shoulder, no similar guidelines have been produced for open stabilization procedures such as the Latarjet.10 Anecdotally, many surgeons consider the postoperative rehabilitation protocols to be similar, given that both procedures treat anterior shoulder instability. Although this hypothesis has not been adequately studied, comparative studies have suggested that patients undergoing Latarjet procedures return to sport more quickly than patients undergoing arthroscopic Bankart repair.1,11

Accordingly, the purpose of the current study was to (1) define the degree of variability across rehabilitation protocols published online for the Latarjet procedure and (2) compare Latarjet rehabilitation programs with published Bankart repair protocols. We hypothesized that the consistency of the programs would vary widely and there would be substantial temporal differences in milestones between Latarjet and Bankart protocols.

Methods

A single researcher reviewed publicly available physical therapy rehabilitation protocols found by utilizing a web-based search for the following: (Latarjet OR bristow OR bristow-latarjat OR coracoid transfer) AND (rehab OR rehabilitation OR postoperative protocol). This included all available protocols from Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited academic orthopaedic surgery programs. Protocols were excluded if they were not specific to open Latarjet procedures or if they did not include any time points, goals, or specific rehabilitation phases. All rehabilitation protocols were reviewed for components of immobilization and rehabilitation. To effectively compare rehabilitation protocols, categories previously published by DeFroda et al5 were utilized. These included postoperative adjunct therapy, early range of motion (ROM), passive ROM start dates and goals, late ROM exercises and goals, resistance exercises and strengthening, and sport-specific activities. Within each category, specific functional milestones, exercise recommendations, and start times were identified and recorded. A complete list of collected variables by category can be found in Table 1. Statistical comparisons were made between Bankart protocols published by DeFroda et al and the Latarjet protocols reviewed by this study. Binary variables (ie, sling immobilization, hand/wrist ROM, and passive supine external rotation [ER]) were compared between protocols utilizing chi-square analysis, while the average postoperative week at which specific activities were recommended was compared utilizing Student t tests. All statistical tests assumed a type 1 error rate of 5% and were conducted utilizing R Studio software Version 1.0.143 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Table 1.

Collected variables by category a

| Postoperative adjuvant therapies | Immobilization type, sling, sling discontinuation timeline, timeline for ROM restriction, brace for return to sport |

| Postoperative exercises | Elbow/wrist/hand activity, home exercises, pendulum, supine forward flexion (FF), supine external rotation (ER), supine cross-chest adduction, sleeper stretch, hand up back of spine, periscapular stretching, scapular clocks, wands, standing internal rotation (IR), shoulder pinches |

| Passive ROM goals | 60°, 90°, 120°, 145°, 160° passive FF 0°, 20°-30°, 45°, 60°, 90° passive ER 30°, 40°, buttock, L3, T12 passive IR Start passive ROM (PROM), full PROM |

| Late ROM activities | Isometric deltoid, scapular stabilization, submaximal isometric, isotonic resistance, serratus punches, normal scapulothoracic motion, start active ROM |

| Strengthening exercises | Band training, light resistance, cocking weight, plyometrics, medicine ball, closed chain training, push-ups, resisted ER, resisted IR, dumbbell training, light biceps curl, bench press, latissimus pull-downs, pull-ups |

| Sport-specific exercises | Aquatic therapy, treadmill walk, StairMaster, jogging, stationary bike, running, swimming, push-ups, leg exercises, upper body ergometer, throw from mound |

| Return to sport | Return to sport, return to game, brace use, criteria for return specified |

Postoperative adjuvant therapies: examined as a binary variable, for presence or absence of criteria. Strengthening exercises and sport-specific exercises: examined as a continuous variable, indicating start week of therapy.

Results

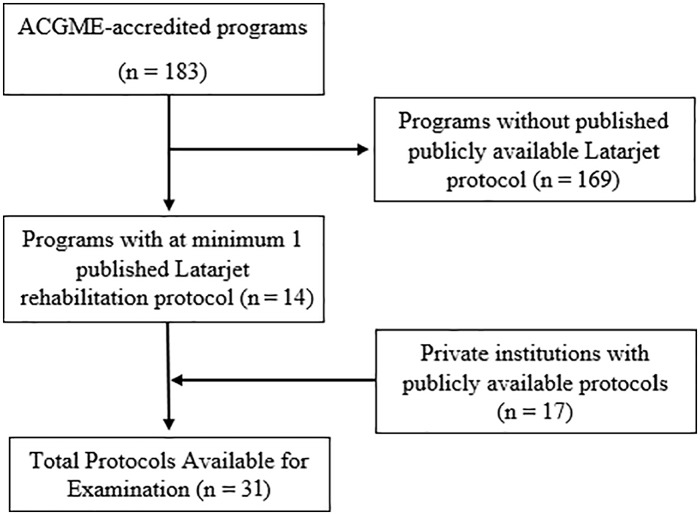

Of the 183 ACGME-accredited orthopaedic programs reviewed, 14 institutions (7.65%) had publicly available rehabilitation protocols. A web-based search yielded 17 additional protocols from various private practices (Figure 1). These protocols were compared with 30 Bankart rehabilitation protocols in the published literature.5

Figure 1.

CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram. ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Postoperative Adjunct Therapy

Of the 31 protocols included, 31 (100%) recommended postoperative sling use. Of these, 11 (35%) specified sling immobilization, 3 (9.6%) specified a sling immobilization with an abduction pillow, and 1 (3.2%) specified a sling and swath. The average duration in the sling was 5.3 ± 1.2 weeks. Although the majority of protocols did not specify any time period of strict immobilization, 8 (25.8%) protocols recommended some duration of strict immobilization (mean, 1.6 ± 0.7 weeks). No protocols recommended the use of a brace after return to sport or on discharge for any activities (Table 2).

Table 2.

Postoperative Adjunctive Therapy Recommendations a

| n | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Sling immobilization | 11 | 35 |

| Sling immobilization with abduction pillow | 3 | 9.6 |

| Sling and swath | 1 | 3.2 |

| Strict immobilization | 8 | 25.8 |

| Brace | 0 | 0 |

Average duration of sling use 5.29 ± 1.16 weeks.

Early ROM

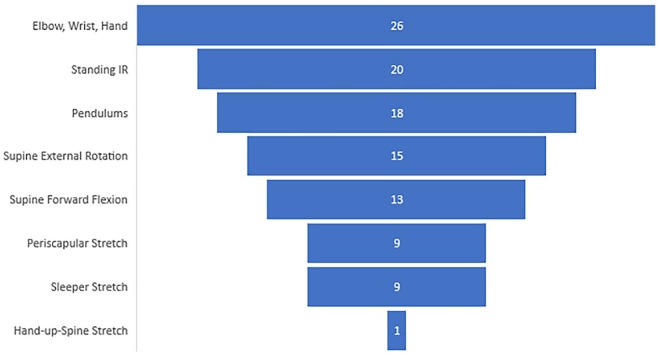

Initiation of ROM within the protocols was highly variable. Elbow, wrist, and hand ROM was the most often recommended activity (26 protocols; 84%), followed by standing internal rotation (20 protocols; 64%), and pendulums (18 protocols; 58%). The least frequent immediate postoperative therapy recommended exercises included hand up the back of the spine (1 protocol; 3%), the sleeper stretch (9 protocols; 29%), and periscapular stretching (9 protocols; 29%). Immediate postoperative passive supine forward flexion (FF) was recommended by 13 protocols (42%), and supine ER by 15 protocols (48%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Early range of motion (ROM) exercises. Data labels represent total counts across n = 31, with elbow/hand/wrist exercises representing the most commonly referenced early ROM exercise (n = 26; 84%) and hand-up-spine stretches representing the least common (n = 1; 3%). IR, internal rotation.

Passive ROM Start Dates and Goals

Postoperative passive ROM was started at an average of 0.8 ± 1.1 weeks. Achieving the goal of 60° passive FF averaged 1.1 ± 1.2 weeks, and full passive FF was achieved at an average of 3.2 ± 2.4 postoperative weeks. A 20° to 30° ER goal averaged 1.5 ± 1.8 weeks postoperatively, and the mean time to achieve full passive ER was 6.5 ± 2.0 weeks postoperatively. Finally, the mean time to achieve full passive ROM in all planes was 8.4 ± 3.2 weeks postoperatively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Passive range of motion time line. PIR behind back, buttock, L3, and T12 excluded due to lack of tabulated data across protocols. PER, passive external rotation; PFF, passive forward flexion; PIR, passive internal rotation; PROM, passive range of motion.

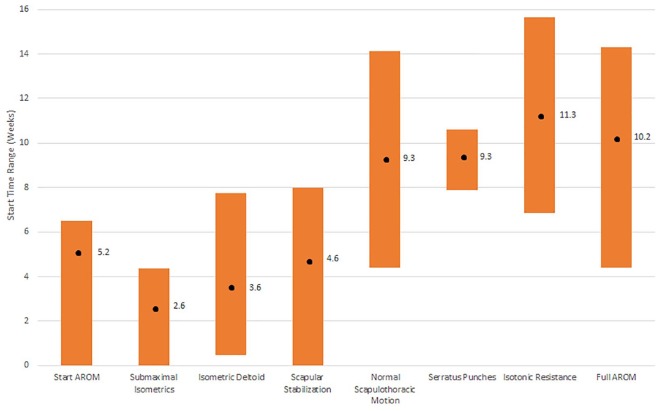

Late ROM Exercises and Goals

Active ROM began on average at 5.2 ± 1.3 weeks, with a goal of full active ROM by 10.2 ± 4.0 weeks postoperatively. Finally, normal scapulothoracic motion was to be achieved by a mean of 9.3 ± 4.8 weeks postoperatively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Active range of motion time line. Black dot represents mean, with bar representing 1 SD from the mean in weeks. AROM, active range of motion.

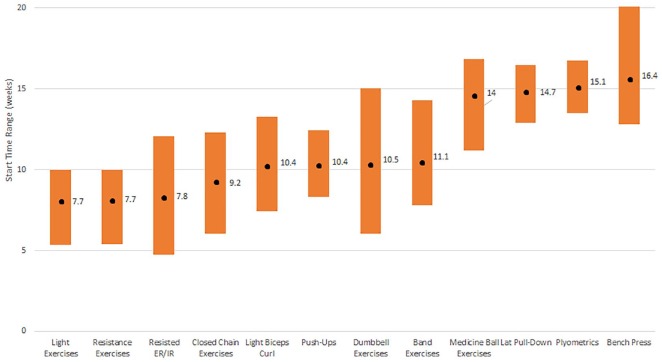

Resistance Exercises and Strengthening

On average, resistance exercises began at 7.7 ± 2.1 weeks postoperatively. Closed chain training was initiated at an average of 9.2 ± 3.1 postoperative weeks. Plyometric exercises began at an average of 15.1 ± 1.6 weeks postoperatively. Start dates varied by the specific exercise: resisted internal and external cables were started at an average of 7.8 ± 2.2 weeks, push-ups were allowed at an average of 10.4 ± 2.0 weeks, dumbbell training and free weights at 10.5 ± 4.5 weeks, and light biceps curls at 10.4 ± 2.9 weeks postoperatively (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Resistance exercise and strengthening time line. Black dot: mean of start times; bar representing the range of earliest to latest start times in weeks. ER, external rotation; IR, internal rotation.

Sport-Specific Activities

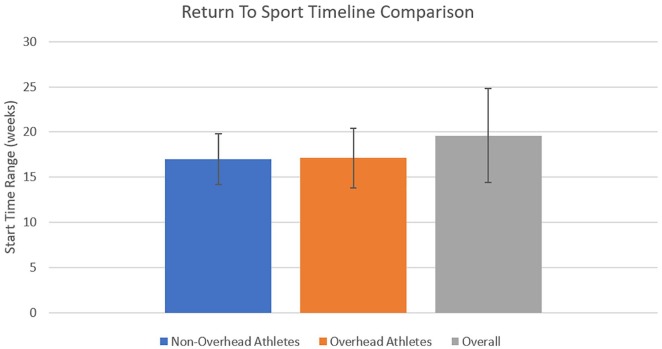

Sport-specific activity was consistently the last portion of the rehabilitation protocols. Twenty (65%) protocols provided specific recommendations for return to nonoverhead sport–specific activities, which began at an average of 17 ± 2.8 weeks postoperatively. This was compared with overhead sports or throwing activities, for which 18 (58%) of protocols recommended beginning at a similar average of 17.1 ± 3.3 weeks. One protocol (3.2%) recommended upper body ergometer use starting at 16 weeks. Five (16.1%) protocols recommended initiation of stationary bike use at an average of 4.5 ± 3.3 weeks, whereas 4 (12.9%) protocols recommended treadmill use starting as early as 1 week postoperatively. Initiation of running was specifically recommended at 11 ± 4.6 weeks by 3 protocols, and no protocols mentioned recommendations for use of the StairMaster machine or swimming. The time line to return to sport was specified in 22 (71%) protocols and averaged 19.6 ± 5.2 weeks. In addition, 23 (74%) of protocols offered return-to-sport criteria (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Return-to-sport time line for nonoverhead versus overhead athletes versus all protocols.

Statistical Comparison of Bankart and Latarjet Protocols

Statistically significant differences were found between the recommendation of sling immobilization, with Bankart protocols recommending sling immobilization more often than Latarjet protocols (80% vs 35.5%; P < 0.001) (Table 3). In addition, Bankart protocols reported greater passive supine ER goals than did Latarjet protocols (63° vs 42°, P = 0.03). Other significant differences between groups included longer average time lines for 60° passive FF (1.7 ± 0.6 vs 1.1 ± 1.2 weeks), full passive FF (7.2 ± 2.4 vs 3.2 ± 2.4 weeks), 20° to 30° ER (3.6 ± 1.6 vs 1.5 ± 1.8 weeks), normal scapulothoracic motion (14.7 ± 4.6 vs 9.3 ± 4.8 weeks), and return to sport (32.4 ± 9.3 vs 19.6 ± 5.2 weeks) for Bankart repair protocols relative to Latarjet rehabilitation protocols (P = 0.03 to P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Statistical Comparison Of Rehabilitation Timeline Data

| Rehabilitation Goal | DeFroda et al5 (B) | Current Study (L) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sling immobilization | 80% | 35.4% | <0.001 |

| Hand/wrist/elbow ROM | 66.7% | 84% | 0.12 |

| Passive supine ER | 63.3° | 42° | 0.03 |

| Strict immobilization | 2.8 ± 1.6 weeks | 1.6 ± 0.7 weeks | 0.07 |

| Time of sling | 4.8 ± 1.8 weeks | 5.3 ± 1.2 weeks | 0.42 |

| 60° passive FF | 1.7 ± 0.6 weeks | 1.1 ± 1.2 weeks | 0.03 |

| Full passive FF | 7.2 ± 2.4 weeks | 3.2 ± 2.4 weeks | <0.001 |

| 20°-30° ER | 3.6 ± 1.6 weeks | 1.5 ± 1.8 weeks | <0.001 |

| Full passive ER | 9.1 ± 2.6 weeks | 6.8 ± 2.0 weeks | 0.001 |

| Full AROM | 12.2 ± 2.8 weeks | 10.2 ± 4.0 weeks | 0.077 |

| Normal scapular motion | 14.7 ± 4.6 weeks | 9.3 ± 4.8 weeks | <0.001 |

| Resistance bands | 5.6 ± 2.1 weeks | 7.5 ± 2.2 weeks | 0.008 |

| Push-ups | 11.1 ± 2.2 weeks | 10.3 ± 2.0 weeks | 0.312 |

| Nonoverhead sport | 15 ± 4.2 weeks | 17 ± 2.8 weeks | 0.141 |

| RTS | 32.4 ± 9.3 weeks | 19.6 ± 5.2 weeks | <0.001 |

AROM, active range of motion; B, Bankart repair protocols; ER, external rotation; FF, forward flexion; L, Latarjet coracoid transfer protocols; ROM, range of motion; RTS, return to sport. Boldfaced values are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Discussion

There is a high degree of variability with regard to specific types of exercises and recommended timing of rehabilitation milestones within publicly available Latarjet rehabilitation protocols. While there are similarities between types of motion and exercises in the protocols reviewed, which is similar to that seen in Bankart protocols, there is no clear consensus protocol.5 There appear to be marked differences in how surgeons rehabilitate and advance patients undergoing Latarjet procedures compared with those undergoing soft tissue stabilization as reflected in the protocols reviewed.

Rehabilitation plays a critical role in the success of restoring glenohumeral stability following the Latarjet procedure. Protocols demand a balance between bony union of the coracoid to the glenoid, preventing postoperative stiffness and motion loss, and preparing athletes to return to play in a timely manner. Glenoid augmentation bony union takes approximately 6 to 8 weeks.8 This is compared with soft tissue labral healing, which can take up to 12 weeks and relies on less rigid suture fixation than that of screws in the Latarjet procedure.8 Thus, given the earlier expected healing and more rigid initial fixation, these patients can advance more quickly through postoperative rehabilitation ROM and exercise milestones; however, this has not been demonstrated in the literature. In a similar study, DeFroda et al5 reviewed 30 Bankart repair protocols from ACGME-accredited orthopaedic surgery programs and reported high variability among protocols in addition to significant discrepancies when compared with published consensus protocols. Similarly, when we compare milestones for exercises and motion between Bankart and Latarjet protocols, there are both similarities and differences. For instance, nearly all protocols recommend a period of postoperative immobilization and similar combinations of sling, sling and abduction pillow, and sling and swath use. However, Bankart repair protocols were more likely than Latarjet protocols to specifically recommend immobilization with a sling, despite there not being a significant difference in the average duration of sling immobilization between procedures (P = 0.42). Nonetheless, the period of strict immobilization irrespective of methodology trended toward a significant difference, suggesting Bankart protocols tend to recommend longer periods of immobilization than do Latarjet protocols (P = 0.07). This may reflect a higher level of comfort and confidence in the early fixation strength of the Latarjet procedure compared with the soft tissue fixation achieved in a Bankart repair.

With regard to early ROM there were no significant differences in the percentages of Latarjet and Bankart protocols recommending elbow, wrist, and hand ROM or pendulum exercises. However, exercises involving internal rotation were similarly avoided by both protocols. These included the sleeper stretch and hand up the back of the spine (29% and 3%) in the Latarjet protocols, and any internal rotation (3.3%) in the Bankart protocols. However, with respect to passive ROM, the current study found that Bankart protocols delayed average time of initiation for passive ER and FF relative to Latarjet protocols. A similar trend was found for initiation of active 20° to 30° ER (3.6 vs 1.5 weeks; P < 0.001), suggesting that surgeons may feel more comfortable advancing Latarjet patients more quickly through milestones secondary to the reliable bony healing. These trends are further reinforced when goals of achieving full active ROM of the shoulder and full scapulothoracic motion are compared. In the Latarjet group, the goal of achieving full active ROM averaged 10.2 ± 4.0 weeks, compared with 12.2 ± 2.8 weeks as reported by DeFroda et al.5 Similarly, the goal of achieving full scapulothoracic motion was more than 5 weeks quicker in the Latarjet group compared with that reported in the Bankart study. Other important relative delays in rehabilitative time lines for Bankart repair were observed for closed chain activities such as push-ups and bench press, which were allowed 1 to 2 weeks sooner in Latarjet protocols. All in all, these data suggest that important differences exist in the time line of passive ROM, active ROM, and exercise-specific rehabilitation between Bankart and Latarjet rehabilitation protocols.

Although the success of shoulder instability surgery is largely defined by the lack of recurrence, the time to return to sport has emerged as an important and clinically significant metric indicative of success following shoulder stabilization.1 A recent systematic review of 16 articles1 reported a return to sport rate of 97.5% and 83.6% after arthroscopic Bankart and open Latarjet procedures, respectively. Furthermore, the time to return to sport was 5.07 months for Latarjet compared with 5.9 months after arthroscopic Bankart. While surgeon experience, surgical technique, and a multitude of patient-related factors highly influence the ability and timing of return to sport for an athlete after shoulder stabilization, perhaps a more understated component of this metric is postoperative rehabilitation. In the current study, Latarjet protocols allowed return to sport at an average of 19.6 ± 5.2 weeks, compared with 32.4 ± 9.3 weeks in Bankart protocols reviewed by DeFroda et al.5 Based on our review of Latarjet and Bankart protocols, Latarjet patients undergo earlier mobilization, ROM, and exercise programs that may contribute to the earlier return-to-sport times published in the broader literature. We hypothesize that surgeons may be more comfortable with the initial fixation strength and reliability of bony healing compared with that achieved with arthroscopic Bankart repair techniques, and this may translate into a more accelerated rehabilitation process. Finally, we encourage surgeons to see these 2 procedures and their rehabilitation strategies as separate.

There are several limitations to the current study. Although we performed an exhaustive online search for all available Latarjet protocols, only 31 protocols were publicly available, and this ultimately represents a likely small percentage of surgeons performing Latarjet procedures in the United States. In addition, there was a high degree of variability of what was specifically listed within the rehabilitation protocols. Mean timeline data for specific rehabilitation milestones (i.e. walking on a treadmill, jogging) was listed across only a few protocols, creating large standard deviations. Similarly, because protocols were not standardized with regard to exercises across both Latarjet and Bankart programs, it was difficult to make more direct comparisons with regard to start times and goals of specific exercises that were not as frequently recommended. Additionally, surgeon technique likely influences rehabilitation protocols; unfortunately, these could not be obtained and were thus not controlled for. Last, many orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons optimize rehabilitation protocols to meet certain sport-specific needs. For example, patients returning to throwing sports differ with regard to loading of the shoulder joint than those returning to contact sports, which often necessitates changes to postoperative rehabilitation protocol. The protocols utilized in this study provided general frameworks for postoperative rehabilitation milestones and did not differentiate based on sport-specific needs.

Conclusion

Similar to Bankart repair protocols, Latarjet rehabilitation protocols contain a high degree of variability with respect to recommended exercises and motion goals. However, when comparing published results of Bankart protocols with Latarjet protocols examined in the current study, it appears that many of these milestones and start dates occur much earlier in Latarjet protocols compared with Bankart programs. This may contribute to the earlier return to play metrics identified in the broader literature for Latarjet compared with arthroscopic Bankart repair.

Footnotes

The following author declared potential conflicts of interest: N.N.V. reports personal fees from Arthrex Inc, DJ Orthopaedics, and Orthospace, and nonfinancial support from Arthrex Inc, Arthroscopy, and Vindico Medical-Orthopedics Hyperguide outside the submitted work; has a Smith & Nephew–Instrumentation patent with royalties paid by Smith & Nephew; and is also a paid consultant and has stock options with Cymedica, Minivasive, and Omeros.

References

- 1. Abdul-Rassoul H, Galvin JW, Curry EJ, Simon J, Li X. Return to sport after surgical treatment for anterior shoulder instability: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1507-1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arciero RA, Parrino A, Bernhardson AS, et al. The effect of a combined glenoid and Hill-Sachs defect on glenohumeral stability. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1422-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonazza NA, Liu G, Leslie DL, Dhawan A. Trends in surgical management of shoulder instability. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5:2325967117712476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Damkjær L, Petersen T, Juul-Kristensen B. Is the American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Therapists’ rehabilitation guideline better than standard care when applied to Bankart-operated patients? A controlled study. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29:154-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DeFroda SF, Mehta N, Owens BD. Physical therapy protocols for arthroscopic Bankart repair. Sports Health. 2018;10:250-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Degen RM, Camp CL, Werner BC, Dines DM, Dines JS. Trends in bone-block augmentation among recently trained orthopaedic surgeons treating anterior shoulder instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Di Giacomo G, Piscitelli L, Pugliese M. The role of bone in glenohumeral stability. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3:632-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fedorka CJ, Mulcahey MK. Recurrent anterior shoulder instability: a review of the Latarjet procedure and its postoperative rehabilitation. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galvin JW, Eichinger JK, Cotter EJ, Greenhouse AR, Parada SA, Waterman BR. Trends in surgical management of anterior shoulder instability: increased utilization of bone augmentation techniques. Mil Med. 2018;183:e201-e206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gaunt BW, Shaffer MA, Sauers EL, Michener LA, McCluskey GM, Thigpen C. The American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Therapists’ consensus rehabilitation guideline for arthroscopic anterior capsulolabral repair of the shoulder. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40:155-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ialenti MN, Mulvihill JD, Feinstein M, Zhang AL, Feeley BT. Return to play following shoulder stabilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5:2325967117726055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robinson CM, Howes J, Murdoch H, Will E, Graham C. Functional outcome and risk of recurrent instability after primary traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation in young patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2326-2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Trivedi S, Pomerantz ML, Gross D, Golijanan P, Provencher MT. Shoulder instability in the setting of bipolar (glenoid and humeral head) bone loss: the glenoid track concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2352-2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]