Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have gained increasing attention as they exhibit highly tissue- and cell-type specific expression patterns. LncRNAs are highly expressed in the central nervous system and their roles in the brain have been studied intensively in recent years, but their roles in the spinal motor neurons (MNs) are largely unexplored. Spinal MN development is controlled by precise expression of a gene regulatory network mediated spatiotemporally by transcription factors, representing an elegant paradigm for deciphering the roles of lncRNAs during development. Moreover, many MN-related neurodegenerative diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), are associated with RNA metabolism, yet the link between MN-related diseases and lncRNAs remains obscure. In this review, we summarize lncRNAs known to be involved in MN development and disease, and discuss their potential future therapeutic applications.

Keywords: Long non-coding RNA, Motor neuron, Spinal muscular atrophy, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Introduction

Next-generation RNA sequencing technology has revealed thousands of novel transcripts that possess no potential protein-coding elements. These RNAs are typically annotated as non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in the Human Genome Project and ENCODE Project [31, 59, 147]. Although most of the human genome is transcribed at certain stages during embryonic development, growth, or disease progression, ncRNAs were classically considered transcriptional noise or junk RNA due to their low expression levels relative to canonical mRNAs that generate proteins [19, 60]. However, emerging and accumulating biochemical and genetic evidences have gradually revealed their important regulatory roles in development and disease contexts [11, 109]. In principle, regulatory ncRNAs can be further divided into two groups depending on their lengths. Small RNAs are defined as being shorter than 200 nucleotides (nt), which include well-known small RNAs such as microRNA (miRNA, 22-25 nt), Piwi interacting RNA (piRNA, 21-35 nt), small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA, 60-170 nt), and transfer RNA (tRNA, 70-100 nt). NcRNAs longer than 200 nt are termed as long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) that comprise about 10~30% of transcripts in both human (GENCODE 32) and mouse (GENCODE M23) genomes, suggesting that they may play largely unexplored roles in mammal physiology. LncRNAs can be classified further according to their genomic location. They can be transcribed from introns (intronic lncRNA), coding exons, 3' or 5' untranslated regions (3' or 5' UTRs), or even in an antisense direction overlapping with their own transcripts (natural antisense transcript, NAT) [64, 130]. In regulatory regions, upstream of promoters (promoter upstream transcript, PROMPT) [106], enhancers (eRNA) [76], intergenic regions (lincRNA) [114] and telomeres [81] can be other sources of lncRNAs. Many hallmarks of lncRNA processing are similar to those of mRNAs in post-transcription, such as nascent lncRNAs being 5'-capped, 3'-polyadenylated or alternatively spliced [19]. LncRNA production is less efficient than for mRNAs and their half-lives appear to be shorter [98]. Unlike mRNA that is directly transported to the cytoplasm for translation, many lncRNAs tend to be located in the nucleus rather than in the cytosol, as revealed by experimental approaches such as fluorescent in situ hybridization [20, 67]. However, upon export to cytoplasm, some lncRNAs bind to ribosomes where they can be translated into functional peptides under specific cell contexts [20, 58]. For instance, myoregulin is encoded by a putative lncRNA and binds to sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SRCA) to regulate Ca2+ import in the sarcoplasmic reticulum [6]. Nevertheless, it remains to be established if other ribosome-associated lncRNAs generate functional peptides.

General function of lncRNAs

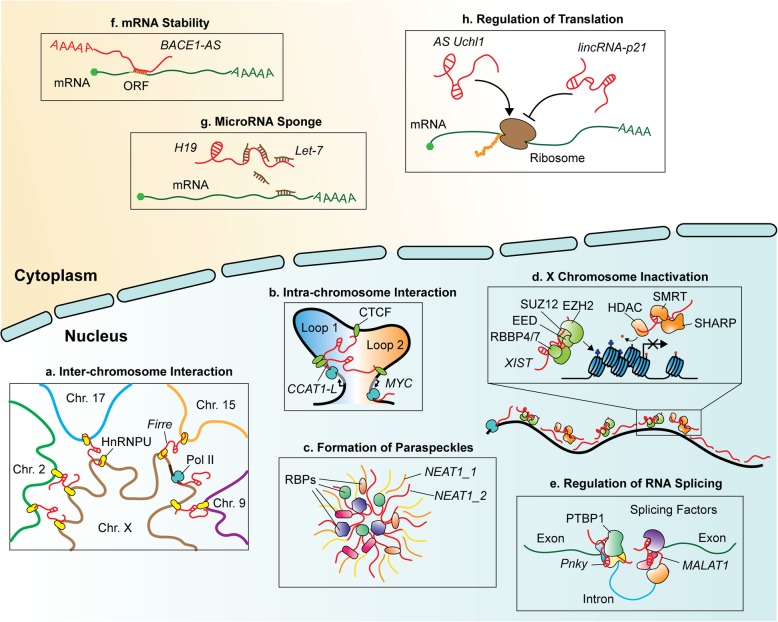

A broad spectrum of evidence demonstrates the multifaceted roles of lncRNAs in regulating cellular processes. In the nucleus, lncRNAs participate in nearly all levels of gene regulation, from maintaining nuclear architecture to transcription per se. To establish nuclear architecture, Functional intergenic repeating RNA element (Firre) escapes from the X chromosome inactivation (XCI) and bridges multi-chromosomes, partly via association with heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U (hnRNPU) (Figure 1a) [54]. CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF)-mediated chromosome looping can also be accomplished by lncRNAs. For example, colorectal cancer associated transcript 1 long isoform (CCAT1-L) facilitates promoter-enhancer looping at the MYC locus by interacting with CTCF, leading to stabilized MYC expression and tumorigenesis (Figure 1b) [153]. In addition, CTCF binds to many X chromosome-derived lncRNAs such as X-inactivation intergenic transcription element (Xite), X-inactive specific transcript (Xist) and the reverse transcript of Xist (Tsix) to establish three-dimensional organization of the X chromosome during XCI [69]. In addition to maintaining nuclear architecture, lncRNAs may also serve as building blocks of nuclear compartments. For example, nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1) is the core element of paraspeckles that participate in various biological processes such as nuclear retention of adenosine-to-inosine-edited mRNAs to restrict their cytoplasmic localization and viral infection response. However, the exact function of paraspeckles has yet to be fully deciphered (Figure 1c) [26, 30, 57]. LncRNAs can also function as a scaffolding component, bridging epigenetic modifiers to coordinate gene expression (e.g. activation or repression). For instance, Xist interacts with polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) and the silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT)/histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1)-associated repressor protein (SHARP) to deposit a methyl group on lysine residue 27 of histone H3 (H3K27) and to deacetylate histones, respectively, leading to transcriptional repression of the X chromosome (Figure 1d) [87]. Similarly, Hox antisense intergenic RNA (Hotair) bridges the PRC2 complex and lysine-specific histone demethylase 1A (LSD1, a H3K4me2 demethylase) to synergistically suppress gene expression [118, 140]. In contrast, HOXA transcript at the distal tip (HOTTIP) interacts with the tryptophan-aspartic acid repeat domain 5 - mixed-lineage leukemia 1 (WDR5-MLL1) complex to maintain the active state of the 5' HOXA locus via deposition of histone 3 lysine 4 tri-methylation (H3K4me3) [149]. LncRNAs also regulate the splicing process by associating with splicing complexes. A neural-specific lncRNA, Pnky, associates with the splicing regulator polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 (PTBP1) to regulate splicing of a subset of neural genes [112]. Moreover, interaction between Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (Malat1) and splicing factors such as serine/arginine rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1) is required for alternative splicing of certain mRNAs (Figure 1e) [139].

Fig. 1.

Summary (with examples) of the multifaceted roles of lncRNAs in the cell. a The X chromosome-derived lncRNA Firre associates with HnRNPU to establish inter-chromosome architecture. bCCAT1-L generated from upstream of MYC loci promotes MYC expression via CTCF-mediated looping. c Paraspeckle formation is regulated by interactions between NEAT1_2 and RBPs. d X chromosome inactivation is accomplished by coordination between Xist-PRC2-mediated deposition of H3K27me3 and Xist-SMRT/SHARP/HDAC-mediated deacetylation of H3ac. e Facilitation of RNA splicing by Pnky/PTBP1 and Malat1/RBPs complexes. fBACE1-AS associates with BACE1 mRNA via the open reading frame to stabilize BACE1 mRNA. gH19 lncRNA sequesters let-7 miRNA to prevent let-7-mediated gene suppression. h Antisense Uchl1 promotes but lincRNA-p21 inhibits the translation process.

Apart from nucleus, lncRNAs in the cytoplasm are typically involved in mRNA biogenesis. For example, in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), β-secretase-1 antisense RNA (BACE1-AS) derived within an important AD-associated enzyme, BACE1, elevates BACE1 protein levels by stabilizing its mRNA through a post-translational feed-forward loop [44]. Mechanistically, BACE1-AS masks the miRNA-485-5p binding site at the open reading frame of BACE1 mRNA to maintain BACE1 mRNA stability (Figure 1f) [45]. H19, a known imprinting gene expressed as a lncRNA from the maternal allele, promotes myogenesis by sequestering lethal-7 (let-7) miRNAs that, in turn, prevents let-7-mediated gene repression (Figure 1g) [62]. LncRNAs not only regulate transcription but also affect translation. Human lincRNA-p21 (Trp53cor1) disrupts translation of CTNNB1 and JUNB via base-pairing at multiple sites of the 5' and 3' UTR and coding regions, resulting in recruitment of the translational repressors RCK and fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) to suppress translation (Figure 1h, right) [158]. In contrast, an antisense RNA generated from ubiquitin carboxyterminal hydrolase L1 (AS Uchl1) promotes translational expression of Uchl1 protein via its embedded short interspersed nuclear elements B2 (SINEB2). In the same study, inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) was shown to trigger cytoplasmic localization of AS Uchl1 and to increase the association between polysomes and Uchl1 mRNA in a eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4F (eIF4F) complex independently of translation (Figure 1h, left) [21]. Finally, compared to mRNAs, lncRNAs seem to manifest a more tissue-specific manner [19]. In agreement with this concept, genome-wide studies have revealed that large numbers of tissue-specific lncRNAs are enriched in brain regions and some of them are involved in neurogenesis [7, 15, 37, 89]. We discuss some of these lncRNAs in greater detail below, with a particular focus on their roles during spinal MN development as this latter serves as one of the best paradigms for studying the development and degeneration of the central nervous system (CNS).

Role of lncRNAs in regulating neural progenitors

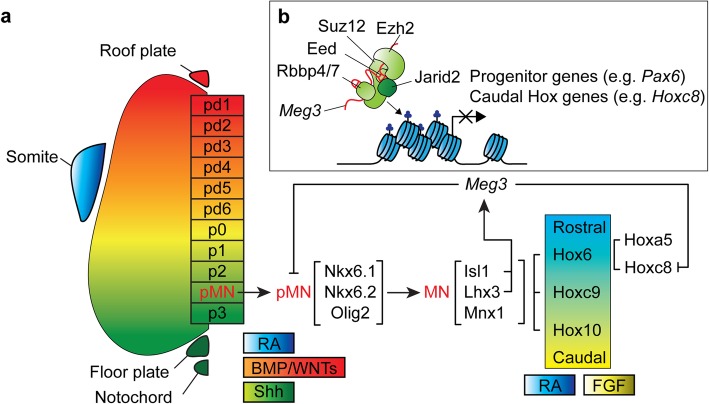

As part of the CNS, spinal MNs are located in the ventral horn of the spinal cord that conveys signals from the brainstem or sensory inputs to the terminal muscles, thereby controlling body movements. MN development requires precise spatiotemporal expression of extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Upon neurulation, the wingless/integrated protein family (WNT) and the bone morphogenetic protein family (BMP) are secreted from the roof plate of the developing neural tube to generate a dorsal to ventral gradient [4, 88]. In contrast, sonic hedgehog (Shh) proteins emanating from the floor plate as well as the notochord generate an opposing ventral to dorsal gradient [16]. Together with paraxial mesoderm-expressed retinoic acid (RA), these factors precisely pattern the neural tube into spinal cord progenitor domains pd1~6, p0, p1, p2, motor neuron progenitor (pMN), and p3 along the dorso-ventral axis (Figure 2a). This patterning is mediated by distinct expression of cross-repressive transcription factors—specifically, Shh-induced class II transcription factors (Nkx2.2, Nkx2.9, Nkx6.1, Nkx6.2, Olig2) or Shh-inhibited class I transcription factors (Pax3, Pax6, Pax7, Irx3, Dbx1, Dbx2)—that further define the formation of each progenitor domain [104, 143]. All spinal MNs are generated from pMNs, and pMNs are established upon co-expression of Olig2, Nkx6.1 and Nkx6.2 under conditions of high Shh levels [2, 105, 132, 162]. Although a series of miRNAs have been shown to facilitate patterning of the neuronal progenitors in the spinal cord and controlling of MN differentiation [24, 25, 27, 74, 141, 142], the roles of lncRNAs during MN development are just beginning to emerge. In Table 1, we summarize the importance of lncRNAs for the regulation of transcription factors in MN contexts. For instance, the lncRNA lncrps25 is located near the S25 gene (which encodes a ribosomal protein) and it shares high sequence similarity with the 3' UTR of neuronal regeneration-related protein (NREP) in zebrafish. Loss of lncrps25 reduces locomotion behavior by regulating pMN development and Olig2 expression [48]. Additionally, depletion of an MN-enriched lncRNA, i.e. Maternally expressed gene 3 (Meg3), results in upregulation of progenitor genes (i.e., Pax6 and Dbx1) in embryonic stem cell (ESC)-derived post-mitotic MNs, as well as in post-mitotic neurons in embryos. Mechanistically, Meg3 associates with the PRC2 complex to facilitate the maintenance of H3K27me3 levels in many progenitor loci, including Pax6 and Dbx1 (Figure 2b) [156]. Apart from lncRNA-mediated regulation of Pax6 in the spinal cord, corticogenesis in primates also seems to rely on the Pax6/lncRNA axis [113, 145]. In this scenario, primate-specific lncRNA neuro-development (Lnc-ND) located in the 2p25.3 locus [131] exhibits an enriched expression pattern in neuronal progenitor cells but reduced expression in the differentiated neurons. Microdeletion of the 2p25.3 locus is associated with intellectual disability. Manipulations of Lnc-ND levels reveals that Lnc-ND is required for Pax6 expression and that overexpression of Lnc-ND by means of in utero electroporation in mouse brain promotes expansion of the Pax6-positive radial glia population [113]. Moreover, expression of the Neurogenin 1 (Ngn1) upstream enhancer-derived eRNA, utNgn1, is necessary for expression of Ngn1 itself in neocortical neural precursor cells and it is suppressed by PcG protein at the ESC stage [108]. Thus, lncRNAs seem to mediate a battery of transcription factors that are important for early neural progenitor patterning and this role might be conserved across vertebrates.

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of spinal motor neuron development. a Notochord- and floor plate-derived sonic hedgehog protein (Shh), and roof plate-generated wingless/integrated (WNT) protein and bone morphogenetic (BMP) protein, as well as retinoic acid (RA) diffusing from the paraxial mesoderm, pattern the identities of spinal neurons by inducing cross-repressive transcription factors along the dorso-ventral axis (pd1~6, p0, p1, p2, pMN, and p3). Motor neuron progenitors (pMNs) are generated by co-expression of Olig2, Nkx6.1 and Nkx6.2. After cell cycle exit, pMNs give rise to generic MNs by concomitantly expressing Isl1, Lhx3 and Mnx1. Along the rostro-caudal axis, Hox6/Hoxc9/Hox10 respond to RA and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) to pattern the brachial, thoracic and lumbar segments, respectively. b In the Hox6on segment, the interaction between PRC2-Jarid2 complex and a Isl1/Lhx3 induced lncRNA Meg3 perpetuates the brachial Hoxa5on MN by repressing caudal Hoxc8 and alternative progenitor genes Irx3 and Pax6 via the maintenance of H3K27me3 epigenetic landscape in these genes. Yet the detailed mechanism how Meg3 targets to these selective genes still needs to be illustrated.

Table 1.

Proposed functions of lncRNAs during spinal motor neuron development

| LncRNA | Proposed function | Organism/cell models | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lncrps25 | Affects Olig2 expression | Zebrafish | [48] |

| CAT7/cat7l | Recruitment of PRC1 and PRC2 complexes to suppress MNX1 expression in progenitor MNs | Zebrafish/hESC~MNs | [115] |

| Meg3 | Association with PRC2 complex to repress MN progenitor and caudal Hox genes in cervical MNs | Mouse/mESC~MNs | [156] |

LncRNAs in the regulation of postmitotic neurons

In addition to their prominent functions in neural progenitors, lncRNAs also play important roles in differentiated neurons. Taking spinal MNs as an example, postmitotic MNs are generated from pMNs, and after cell cycle exit they begin to express a cohort of MN-specific markers such as Insulin gene enhancer protein 1 (Isl1), LIM/homeobox protein 3 (Lhx3), and Motor neuron and pancreas homeobox 1 (Mnx1, Hb9) (Figure 2a). Isl1/Lhx3/NLI forms an MN-hexamer complex to induce a series of MN-specific regulators and to maintain the terminal MN state by repressing alternative interneuron genes [43, 72]. Although the gene regulatory network for MN differentiation is very well characterized, the role of the lncRNAs involved in this process is surprisingly unclear. Only a few examples of that role have been uncovered. For instance, the lncRNA CAT7 is a polyadenylated lncRNA that lies upstream (~400 kb) of MNX1 identified from the RNA-Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) interactome. Loss of CAT7 results in de-repression of MNX1 before committing to neuronal lineage through reduced PRC1 and PRC2 occupancy at the MNX1 locus in hESC~MNs [115]. Furthermore, an antisense lncRNA (MNX1-AS1) shares the same promoter as MNX1, as revealed by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9) screening [53]. These results suggest that in addition to neural progenitors, lncRNAs could have another regulatory role in fine-tuning neurogenesis upon differentiation. However, whether the expression and functions of these lncRNAs are important for MN development in vivo still needs to be further validated. Future experiments to systematically identify lncRNAs involved in this process will greatly enhance our knowledge about lncRNAs and their mysterious roles in early neurogenesis.

After generic postmitotic MNs have been produced, they are further programmed into versatile subtype identities along the rostro-caudal spinal cord according to discrete expression of signaling molecules, including retinoic acid (RA), WNT, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and growth differentiation factor 11 (GDF11), all distributed asymmetrically along the rostro-caudal axis (Figure 2a). Antagonistic signaling of rostral RA and caudal FGF/GDF11 further elicits a set of Homeobox (Hox) proteins that abut each other, namely Hox6, Hox9 and Hox10 at the brachial, thoracic and lumbar segments, respectively [12, 77, 129]. These Hox proteins further activate downstream transcription factors that are required to establish MN subtype identity. For instance, formation of lateral motor column (LMC) MNs in the brachial and lumbar regions is regulated by Hox-activated Forkhead box protein P1 (Foxp1) [35, 119]. It is conceivable that lncRNAs might also participate in this MN subtype diversification process. For example, the lncRNA FOXP1-IT1, which is transcribed from an intron of the human FOXP1 gene, counteracts integrin Mac-1-mediated downregulation of FOXP1 partly by decoying HDAC4 away from the FOXP1 promoter during macrophage differentiation [128]. However, it remains to be verified if this Foxp1/lncRNA axis is also functionally important in a spinal cord context. An array of studies in various cell models has demonstrated regulation of Hox genes by lncRNAs such as Hotair, Hottip and Haglr [118, 149, 160]. However, to date, only one study has established a link between the roles of lncRNAs in MN development and Hox regulation. Using an embryonic stem cell differentiation system, a battery of MN hallmark lncRNAs have been identified [14, 156]. Among these MN-hallmark lncRNAs, knockdown of Meg3 leads to the dysregulation of Hox genes whereby caudal Hox gene expression (Hox9~Hox13) is increased but rostral Hox gene expression (Hox1~ Hox8) declines in cervical MNs. Analysis of maternally-inherited intergenic differentially methylated region deletion (IG-DMRmatΔ) mice in which Meg3 and its downstream transcripts are further depleted has further revealed ectopic expression of caudal Hoxc8 in the rostral Hoxa5 region of the brachial segment, together with a concomitant erosion of Hox-mediated downstream genes and axon arborization (Figure 2b) [156]. Given that dozens of lncRNAs have been identified as hallmarks of postmitotic MNs, it remains to be determined if these other lncRNAs are functionally important in vivo. Furthermore, lncRNA knockout has been shown to exert a very mild or no phenotype in vivo [52]. Based on several lncRNA-knockout mouse models, it seems that the physiological functions of lncRNAs might not be as prominent as transcription factors during the developmental process [8, 123], yet their functions become more critical under stress conditions such as cancer progression or neurodegeneration [102, 124]. Therefore, next we discuss how lncRNAs have been implicated in MN-related diseases.

Motor neuron-related diseases

Since lncRNAs regulate MN development and function, it is conceivable that their dysregulation or mutation would cause neurological disorders. Indeed, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and comparative transcriptomic studies have associated lncRNAs with a series of neurodegenerative diseases, including the age-onset MN-associated disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [86, 164]. Similarly, lncRNAs have also been linked to spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) [33, 152]. However, most of these studies have described associations but do not present unequivocal evidence of causation. Below and in Table 2, we summarize some of these studies linking lncRNAs to MN-related diseases.

Table 2.

Proposed functions of lncRNAs in spinal motor neuron diseases

| LncRNA | Disease | Proposed function | Organism/cell models | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATXN2-AS | ALS | (CUG)n repeat expansions induce neurotoxicity. | SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells and lymphoblastoid cell lines from ALS patients | [75] |

| C9ORF72 antisense RNA | ALS | Forms RNA foci and repeat-associated non-AUG (RAN) translation generates dipeptides to cause neurotoxicity. | Drosophila, Zebrafish/Neuro-2a, mouse primary cortical and motor neurons | [91, 96, 134, 138, 151, 155, 161] |

| NEAT1 | ALS | Facilitates paraspeckle formation. High levels of NEAT1 trigger neurotoxicity. | Mouse/NSC-34 MN-like cells | [30, 133] |

| SMN-AS1 | SMA | Recruits PRC2 complex to suppress the SMN gene. | Mouse/human SMA-iPSC-derived MNs, SMNΔ7 mouse cortical neurons | [33, 152] |

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

ALS is a neurodegenerative disease resulting in progressive loss of upper and lower MNs, leading to only 5-10 years median survival after diagnosis. More than 90% of ALS patients are characterized as sporadic (sALS), with less than 10% being diagnosed as familial (fALS) [17]. Some ALS-causing genes—such as superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) and fused in sarcoma/translocated in sarcoma (FUS/TLS)—have been identified in both sALS and fALS patients, whereas other culprit genes are either predominantly sALS-associated (e.g. unc-13 homolog A, UNC13A) or fALS-associated (e.g. D-amino acid oxidase, DAO). These findings indicate that complex underlying mechanisms contribute to the selective susceptibility to MN degeneration in ALS. Since many characterized ALS-causing genes encode RNA-binding proteins (RBPs)—such as angiogenin (ANG), TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43), FUS, Ataxin-2 (ATXN2), chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9ORF72), TATA-box binding protein associated factor 15 (TAF15) and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (HNRNPA1)—it is not surprising that global and/or selective RBP-RNAs, including lncRNAs, might participate in ALS onset or disease progression. Below, we discuss some representative examples.

Nuclear Enriched Abundant Transcript 1 (NEAT1)

NEAT1 is an lncRNA that appears to play an important structural role in nuclear paraspeckles [30]. Specifically, there are two NEAT1 transcripts: NEAT1_1 (3.7 kb) is dispensable whereas NEAT1_2 (23 kb) is essential for paraspeckle formation [30, 100]. However, expression of NEAT1_2 is low in the CNS of mouse ALS models relative to ALS patients, indicating a difference between rodent and human systems [101, 103]. Although crosslinking and immunoprecipitation assay (CLIP) has revealed that NEAT1 associates with TDP-43 [103, 137, 154] and FUS/TLS [103], the first evidence linking NEAT1 and paraspeckles to ALS was the observation of co-localization of NEAT1_2 with TDP-43 and FUS/TLS in paraspeckles of early-onset ALS patients [103]. A more detailed analysis has revealed that NEAT1_2 is highly enriched in neurons of the anterior horn of the spinal cord and in cortical tissues of ALS patients [126, 137]. Indeed, increased paraspeckle formation has been reported in the spinal cords of sALS and fALS patients relative to healthy individuals [126], indicating that paraspeckle formation might be a common hallmark of ALS patients. Interestingly, by utilizing an ESC-derived neuron system, a significant increase in paraspeckles was observed at the neuron progenitor stage, suggesting that paraspeckles may exist in the short time-window of neural development [126]. Manipulating ALS-related RBPs (i.e. FUS, TDP-43, and MATR3) impacts levels of NEAT1, showing that these RBPs not only interact with NEAT1 but also regulate NEAT1 RNA levels. The level of NEAT1_2 increases upon FUS, TDP-43 or MATR3 deletion [10, 100]. In contrast, elimination of TAF15, hnRNPA1 or splicing factor proline and glutamine rich (SFPQ) downregulates NEAT1_2 levels [103]. There are conflicting results with regard to whether manipulation of TDP-43 affects NEAT1_2 [100, 126]. Introducing patient-mutated FUS (e.g. P525L) also results in impaired paraspeckle formation by regulating NEAT1 transcription and misassemble of other paraspeckle proteins in the cytoplasm or nucleus [5, 127]. Together, these results seem to indicate that mutation of ALS-related RBPs affects NEAT1 expression and paraspeckle formation during disease progression.

Although many studies have depicted how mutated ALS-related proteins regulate paraspeckle formation, levels of NEAT1_2, inappropriate protein assembly into granules or sub-organelles, and the role of NEAT1_2 in ALS progression remain poorly understood. Recently, direct activation of endogenous NEAT1 using a CRISPR-Cas9 system suggested that elevated NEAT1 expression is somewhat neurotoxic in NSC-34 cells, a mouse MN-like hybrid cell line. Though no direct evidence showing that this effect is mediated by NEAT1_2 was presented in that study, it did at least exclude NEAT1_1 as the mediator [133]. This outcome may imply that increased NEAT1_2 facilitates paraspeckle formation and also somehow induces cell death or degeneration. However, more direct evidence of correlations and concordant links between RBP-lncRNA associations and ALS are needed to strengthen the rationale of utilizing lncRNAs for future therapeutic purposes.

C9ORF72 antisense RNA

In 2011, the C9ORF72 gene with a hexanucleotide GGGGCC (G4C2) repeat expansion was identified as the most frequent genetic cause of both ALS and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) in Europe and North America [36, 117]. ALS and FTD represent a disease spectrum of overlapping genetic causes, with some patients manifesting symptoms of both diseases. Whereas ALS is defined by loss of upper and/or lower MNs leading to paralysis, FTD is characterized by degeneration of the frontal and temporal lobes and corresponding behavioral changes. The abnormal (G4C2) repeat expansion in the first intron of C9ORF72 not only accounts for almost 40% of fALS and familial FTD (fFTD), but it is also found in a small cohort of sALS and sporadic FTD (sFTD) patients [36, 85, 111, 117]. Healthy individuals exhibit up to 20 copies of the (G4C2) repeat, but it is dramatically increased to hundreds to thousands of copies in ALS patients [36]. Loss of normal C9ORF92 protein function and gain of toxicity through abnormal repeat expansion have both been implicated in C9ORF72-associated FTD/ALS. Several C9ORF72 transcripts have been characterized and, surprisingly, antisense transcripts were found to be transcribed from intron 1 of the C9ORF72 gene [97]. Both C9ORF72 sense (C9ORF72-S) and antisense (C9ORF72-AS) transcripts harboring hexanucleotide expansions could be translated into poly-dipeptides and were found in the MNs of C9ORF72-associated ALS patients [47, 50, 95, 121, 151, 163]. Although C9ORF72-S RNA and consequent proteins have been investigated extensively, the functional relevance of C9ORF7-AS is still poorly understood. C9ORF72-AS contains the reverse-repeated hexanucleotide (GGCCCC, G2C4) located in intron 1. Similar to C9ORF72-S, C9ORF72-AS also forms RNA foci in brain regions such as the frontal cortex and cerebellum, as well as the spinal cord (in MNs and occasionally in interneurons) of ALS [49, 163] and FTD patients [36, 49, 92]. Intriguingly, a higher frequency of C9ORF72-AS RNA foci and dipeptides relative to those of C9ORF72-S have been observed in the MNs of a C9ORF72-associated ALS patient, with a concomitant loss of nuclear TDP-43 [32]. In contrast, another study suggested that compared to C9ORF72-S-generated dipeptides (poly-Gly-Ala and poly-Gly-Arg), fewer dipeptides (poly-Pro-Arg and poly-Pro-Ala) derived from C9ORF72-AS were found in the CNS region of C9ORF72-associated FTD patients [83]. These apparently contradictory results perhaps are due to differing sensitivities of the antibodies used in those studies. It has further been suggested that a fraction of the C9ORF72-AS RNA foci is found in the perinucleolar region, indicating that nucleolar stress may contribute to C9ORF72-associated ALS/FTD disease progression [70, 93, 136]. Interestingly, compared to the C9ORF72-S G4C2 repeats, a large number of C9ORF72-AS G2C4 repeats are associated with mono-ribosomes [135], suggesting that fewer dipeptides are generated in the former scenario. This outcome may indicate that C9ORF72-AS RNA may also contribute to the pathology caused by C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion. Whereas C9ORF72-S can form G-quadruplexes [46, 55, 116] that are known to regulate transcription and gene expression [150], the C-rich C9ORF72-AS repeats may not form similar structures. Instead, the G2C4 expansions in C9ORF72-AS may form a C-rich motif [65] that likely affects genome stability and transcription [1]. Notably, an A-form-like double-helix with a tandem C:C mismatch has been observed in a crystal structure of the C9ORF72-AS repeat expansion, suggesting that different structural forms of C9ORF72-AS might regulate disease progression [38]. Thus, during disease progression, not only may C9ORF72-AS form RNA foci to sequester RBPs, but it could also indirectly regulate gene expression via its secondary structure.

Several C9ORF72 gain-of-function and loss-of-function animal models have been generated [9, 91, 138, 155]. A new Drosophila melanogaster (fly) model expressing the G4C2 or G2C4 RNA repeat followed by polyA (termed “polyA”) or these repeats within spliced GFP exons followed by polyA (termed “intronic”) reveals that both sense and antisense “polyA” accumulates in cytoplasm but sense and antisense “intronic” occur in the nucleus, with this latter mimicking actual pathological conditions [94]. However, expression of these repeated RNAs does not result in an obvious motor deficit phenotype, such as climbing ability of the Drosophila model, indicating that the repeats per se may not be sufficient to induce disease progression [94]. Nevertheless, applying that approach in a Danio rerio (zebrafish) model resulted in an outcome contradictory to that in Drosophila, with both sense and antisense repeated RNAs inducing clear neurotoxicity [134]. This discrepancy may be due to differing tolerances to RNA toxicity between the model species and the status of their neurons. Several mouse models have been established by introducing human C9ORF72 repeats only or the gene itself with its upstream and downstream regions via transduction of adeno-associated virus (AAV) or bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) constructs (reviewed in [9]). In the models that harbor full-length human C9ORF72 with repeat expansions as well as upstream and downstream regions, dipeptide inclusions and RNA foci from C9ORF72-S and -AS have been observed and some of them develop motor [78] or cognition (working and spatial memory) defects [61] but others appear normal [107, 110]. Similarly, utilizing differentiated MNs from patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), C9ORF72-associated dipeptides and RNA foci have been observed but some of the expected pathologies were not fully recapitulated [3, 34, 39, 80]. These inconsistent findings may be due to the different genetic backgrounds used or the differing stress conditions applied.

Most studies on C9ORF72 have focused on the pathology caused by repeat expansion, but how C9ORF72 itself is regulated is only beginning to be revealed. Knockdown of a transcription elongation factor, Spt4, rescues C9ORF72-mediated pathology in a Drosophila model and decreases C9ORF72-S and -AS transcripts as well as poly-Gly-Pro protein production in iPSC-derived neurons from a C9ORF72-associated ALS patient [66]. Another CDC73/PAF1 protein complex (PAF1C), which is a transcriptional regulator of RNA polymerase II, has been shown to positively regulate both C9ORF72-S and -AS repeat transcripts [51]. Moreover, reduced expression of hnRNPA3, an G4C2 repeat RNA binding protein, elevates the G4C2 repeat RNA and dipeptide production in primary neurons [96]. Nevertheless, the RNA helicase DDX3X mitigates pathologies elicited by C9ORF72 repeat expansion by binding to G4C2 repeat RNA, which in turn inhibits repeat-associated non-AUG translation (RAN) but does not affect antisense G2C4 repeat RNA in iPSC-derived neurons and the Drosophila model [28]. Collectively, these findings reveal an alternative strategy for targeting C9ORF72 repeat expansions in that antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) could be utilized against C9ORF72-S to attenuate RNA foci and reverse disease-specific transcriptional changes in iPSC-derived neurons [39, 122, 161].

Ataxin 2 antisense (ATXN2-AS) transcripts

Ataxin-2 is an RBP and it serves as a genetic determinant or risk factor for various diseases including spinocerebellar ataxia type II (SCA2) and ALS. ATXN2-AS is transcribed from the reverse strand of intron 1 of the ATXN2 gene. Similar to the G4C2 repeats of C9ORF72-AS, the (CUG)n expansions of ATXN2-AS may promote mRNA stability by binding to U-rich motifs in mRNAs and they have been associated with ALS risk [40, 157]. Furthermore, ATXN2-AS with repeat expansions were shown to induce neurotoxicity in cortical neurons in a length-dependent manner [75]. In that same study, the authors also demonstrated that it is the transcripts rather than the polypeptides generated via RAN translation that are responsible for neurotoxicity. It has been suggested that the toxicity of CUG repeats is due to hairpin formation sequestering RBPs in the cell [68]. Thus, it is likely that the RNA repeats of ATXN2-AS or C9ORF72-S/AS might function in parallel to RAN peptide-induced neurotoxicity to exacerbate degeneration of MNs in ALS.

Other lncRNAs implicated in ALS

By means of an ESC~MN system, several lncRNAs have been shown to be dysregulated in loss-of-function FUS MNs. Compared to FUS+/+ MNs, Lhx1os upregulation and lncMN-1 (2610316D01Rik) and lncMN-2 (5330434G04Rik) downregulation were observed in FUSP517L/P517L and FUS-/- MNs, suggesting that loss of FUS function affects some lncRNAs conserved among mouse and human [14]. A series of lncRNAs that have not been directly implicated in ALS-associated genetic mutations have been identified to participate in ALS contexts. For instance, MALAT1 that contributes to nuclear speckles formation exhibits increased expression and TDP-43 binding in the cortical tissues of sporadic frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) patients, whereas downregulation of Meg3 is associated with expression and binding to TDP-43 in the same system [137]. UV-CLIP analysis has revealed that TDP-43 associates with other lncRNAs such as BDNFOS and TFEBα in SHSY5Y cells [154]. In muscle cells, Myolinc (AK142388) associates with TDP-43 to facilitate binding of this latter protein to myogenic genes, thereby promoting myogenesis [90]. However, whether these lncRNAs play roles in ALS progression needs to be further investigated.

Several studies using Drosophila as a model have uncovered relationships between lncRNAs and ALS. Knockdown of CR18854, an lncRNA associated with the RBP Staufen [71], rescues the climbing ability defects arising from dysregulated Cabeza (the orthologue of human FUS, hereafter referred to as dFUS) in Drosophila [99]. In contrast, knockdown of the lncRNA heat shock RNA ω (hsrω) in Drosophila MNs gives rise to severe motor deficiency by affecting presynaptic terminals. Mechanistically, hsrω interacts with dFUS, and depletion of hsrω results in dFUS translocation into the cytoplasm and abrogation of its nuclear function [79]. Levels of hsrω are positively regulated by TDP-43 via direct binding of TDP-43 to the hsrω locus in Drosophila [29]. The human orthologue of Drosophila hsrω, stress-induced Satellite III repeat RNA (Sat III), has also been shown to be elevated upon TDP-43 overexpression in the frontal cortex of FTLD-TDP patients [29]. It would be interesting to investigate the relationship between Sat III and ALS in human patients.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA)

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic disorder characterized by prominent weakness and wasting (atrophy) of skeletal muscles due to progressive MN degeneration. SMA is the number one worldwide case of neurodegeneration-associated mortality in infants younger than two years old. SMA is caused by autosomal recessive mutation or deletion of the Survival Motor Neuron 1 (SMN1) gene, which can be ameliorated by elevated expression of SMN2, a nearly identical paralogous gene of SMN1 [82]. Since the discovery of SMN1-causing phenotypes in SMA two decades ago [73], many researchers have highlighted SMN2 regulation as a rational approach to boost the generation of full-length SMN2 to offset disease effects [18, 22]. Recently, accumulating evidence has shown a critical role for lncRNAs in regulating the expression of SMN protein. For example, the antisense lncRNA SMN-AS1 derived from the SMN locus suppresses SMN expression, and species-specific non-overlapping SMN-antisense RNAs have been identified in mouse and human [33, 152]. In both these studies, SMN-AS1 recruits the PRC2 complex to suppress expression of SMN protein, which could be rescued by either inhibiting PRC2 activity or by targeted degradation of SMN-AS1 using ASOs. Moreover, a cocktail treatment of SMN2 splice-switching oligonucleotides (SSOs), which enhanced inclusion of exon 7 to generate functional SMN2, with SMN-AS1 ASOs enhanced mean survival of SMA mice from 18 days to 37 days, with ~25% of the mice surviving more than 120 days [33]. These finding suggest that in addition to SSO treatment, targeting SMN-AS1 could be another potential therapeutic strategy for SMA. Moreover, transcriptome analysis has revealed certain lncRNA defects in SMA mice exhibiting early or late-symptomatic stages [13]. By comparing the translatomes (RNA-ribosome complex) of control and SMA mice, some of the lncRNAs were shown to bind to polyribosomes and to alter translation efficiency [13]. Although lncRNAs can associate with ribosomes and some of them generate functional small peptides, it needs to be established if this information is relevant in SMA contexts.

LncRNAs in liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) and motor neuron diseases

An emerging theme of many of the genetic mutations leading to the neurodegenerative MN diseases discussed above is their link to RBPs. Interestingly, many of these RBPs participate in granule formation and are associated with proteins/RNAs that undergo liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) (reviewed in [120]). LLPS is a phenomenon where mixtures of two or more components self-segregate into distinct liquid phases (e.g. separation of oil and water phases) and it appears to underlie formation of many transient membrane organelles, such as stress granules that contain many ribonucleoproteins (RNPs). Although it remains unclear why ubiquitously expressed RNP granule proteins aggregate in neurodegenerative disease, one study found that aggregated forms of mutant SOD1, a protein associated with fALS, accumulates in stress granules [41]. These aggregated forms induce mis-localization of several proteins associated with the miRNA biogenesis machinery, including Dicer and Drosha to stress granules. Consequently, miRNA production is compromised, with several miRNAs (i.e. miR-17~92 and miR-218) perhaps directly participating in ALS disease onset and progression [56, 142]. Mislocalization of ALS-related proteins such as FUS and TDP-43 in the cytosol rather than nucleus of MNs has been observed in ALS patients, but the mechanism remains unclear [125, 146].

A recent study highlighted differences in RNA concentration between the nucleus and cytosol. In the nucleus where the concentration of RNA is high, ALS related-proteins such as TDP-43 and FUS are soluble, but protein aggregations form in the cytosol where the concentration of RNA is low, suggesting that RNA could serve as a buffer to prevent LLPS [84]. Collectively, these findings indicate that not only are RNAs the binding blocks for RBPs, but may also serve as a solvent to buffer RBPs and prevent LLPS. Accordingly, persistent phase separation under stress conditions could enhance formation of irreversible toxic aggregates of insoluble solidified oligomers to induce neuronal degeneration [148]. Although many neurodegenerative diseases have been associated with RNP granules, and primarily stress granules, it remains to be verified if stress granules/LLPS are causative disease factors in vivo. Many other questions remain to be answered. For instance, are the lncRNAs/RNPs mentioned above actively involved in RNP granule formation? Given that purified cellular RNA can self-assemble in vitro to form assemblies that closely recapitulate the transcriptome of stress granules and the stress granule transcriptome is dominated by lncRNAs [63, 144], it is likely that the RNA-RNA interactions mediated by abundantly expressed lncRNAs might participate in stress granule formation in ALS contexts. Similarly, do prevalent RNA modification and editing events in lncRNAs [159] change their hydrophobic or charged residues to affect LLPS and the formation of RNP granules to give rise to disease pathologies? It will be tantalizing to investigate these topics in the coming years.

Conclusion and perspective

Over the past decade, increasing evidence has challenged the central dogma of molecular biology that RNA serves solely as a temporary template between interpreting genetic information and generating functional proteins [23]. Although our understanding of lncRNAs under physiological conditions is increasing, it remains to be established if all expressed lncRNAs play particular and functional roles during embryonic development and in disease contexts. Versatile genetic strategies, including CRISPR-Cas9 technology, have allowed us to clarify the roles of lncRNA, the individual lncRNA transcripts per se, and their specific sequence elements and motifs [42]. Taking spinal MN development and degeneration as a paradigm, we have utilized ESC-derived MNs and patient iPSC-derived MNs to dissect the important roles of lncRNAs during MN development and the progression of MN-related diseases such as ALS and SMA. A systematic effort to generate MN-hallmark lncRNA knockout mice is underway, and we believe that this approach will help us understand the mechanisms underlying lncRNA activity, paving the way to develop new therapeutic strategies for treating MN-related diseases.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to researchers not cited in the manuscript due to limited space. Special thanks to Dr. John O’Brien and Ee Shan Liau for further editing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ASO

Antisense oligonucleotides

- ATXN2-AS

Ataxin 2 antisense transcript

- BACE

β-secretase-1

- C9ORF72

Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72

- CTCF

CCCTC-binding factor

- CNS

Central nervous system

- ESC

Embryonic stem cell

- fALS

Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Foxp1

Forkhead box protein P1

- FTD

Frontotemporal dementia

- fFTD

Familial frontotemporal dementia

- FTLD

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

- FUS/TLS

Fused in sarcoma/translocated in sarcoma

- hsrω

Heat shock RNA ω

- Hox

Homeobox

- iPSC

Induced pluripotent stem cell

- LLPS

Liquid-liquid phase separation

- lncRNA

Long non-coding RNA

- Meg3

Maternally expressed gene 3

- miRNA

microRNA

- MN

Motor neuron

- Mnx1

Motor neuron and pancreas homeobox 1

- NEAT1

Nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1

- ncRNA

Non-coding RNA

- nt

Nucleotide

- pMN

Motor neuron progenitor

- PRC2

Polycomb repressive complex 2

- RA

Retinoic acid

- RBP

RNA-binding protein

- RNP

Ribonucleoprotein

- sALS

Sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Shh

Sonic hedgehog

- SMA

Spinal muscular atrophy

- SMN

Survival motor neuron

- TDP-43

TAR DNA-binding protein 43

- Uchl1

Ubiquitin carboxyterminal hydrolase L1

- UTR

Untranslated region

- Xist

X-inactive specific transcript

Authors’ contributions

K.W.C. and J.A.C. drafted, revised and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Work in the Jun-An Chen lab is supported by grants from the NHRI (NHRI-EX108-10831NI), Academia Sinica (CDA-107-L05), and MOST (108-2311-B-001-011).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kuan-Wei Chen, Email: kwchen@gate.sinica.edu.tw.

Jun-An Chen, Email: jachen@imb.sinica.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Abou AH, Garavis M, Gonzalez C, Damha MJ. i-Motif DNA: structural features and significance to cell biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(16):8038–8056. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alaynick WA, Jessell TM, Pfaff SL. SnapShot: spinal cord development. Cell. 2011;146(1):178–178 e171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almeida S, Gascon E, Tran H, Chou HJ, Gendron TF, Degroot S, Tapper AR, Sellier C, Charlet-Berguerand N, Karydas A, Seeley WW, Boxer AL, Petrucelli L, Miller BL, Gao FB. Modeling key pathological features of frontotemporal dementia with C9ORF72 repeat expansion in iPSC-derived human neurons. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(3):385–399. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1149-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez-Medina R, Cayuso J, Okubo T, Takada S, Marti E. Wnt canonical pathway restricts graded Shh/Gli patterning activity through the regulation of Gli3 expression. Development. 2008;135(2):237–247. doi: 10.1242/dev.012054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An H, Skelt L, Notaro A, Highley JR, Fox AH, La Bella V, Buchman VL, Shelkovnikova TA. ALS-linked FUS mutations confer loss and gain of function in the nucleus by promoting excessive formation of dysfunctional paraspeckles. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s40478-019-0658-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson DM, Anderson KM, Chang CL, Makarewich CA, Nelson BR, McAnally JR, Kasaragod P, Shelton JM, Liou J, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. A micropeptide encoded by a putative long noncoding RNA regulates muscle performance. Cell. 2015;160(4):595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aprea J, Calegari F. Long non-coding RNAs in corticogenesis: deciphering the non-coding code of the brain. EMBO J. 2015;34(23):2865–2884. doi: 10.15252/embj.201592655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnes L, Akerman I, Balderes DA, Ferrer J, Sussel L. betalinc1 encodes a long noncoding RNA that regulates islet beta-cell formation and function. Genes Dev. 2016;30(5):502–507. doi: 10.1101/gad.273821.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balendra R, Isaacs AM. C9orf72-mediated ALS and FTD: multiple pathways to disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(9):544–558. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee A, Vest KE, Pavlath GK, Corbett AH. Nuclear poly(A) binding protein 1 (PABPN1) and Matrin3 interact in muscle cells and regulate RNA processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(18):10706–10725. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beermann J, Piccoli MT, Viereck J, Thum T. Non-coding RNAs in Development and Disease: Background, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Approaches. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(4):1297–1325. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bel-Vialar S, Itasaki N, Krumlauf R. Initiating Hox gene expression: in the early chick neural tube differential sensitivity to FGF and RA signaling subdivides the HoxB genes in two distinct groups. Development. 2002;129(22):5103–5115. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.22.5103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernabo P, Tebaldi T, Groen EJN, Lane FM, Perenthaler E, Mattedi F, Newbery HJ, Zhou H, Zuccotti P, Potrich V, Shorrock HK, Muntoni F, Quattrone A, Gillingwater TH, Viero G. In Vivo Translatome Profiling in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Reveals a Role for SMN Protein in Ribosome Biology. Cell Rep. 2017;21(4):953–965. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biscarini S, Capauto D, Peruzzi G, Lu L, Colantoni A, Santini T, Shneider NA, Caffarelli E, Laneve P, Bozzoni I. Characterization of the lncRNA transcriptome in mESC-derived motor neurons: Implications for FUS-ALS. Stem Cell Res. 2018;27:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2018.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briggs JA, Wolvetang EJ, Mattick JS, Rinn JL, Barry G. Mechanisms of Long Non-coding RNAs in Mammalian Nervous System Development, Plasticity, Disease, and Evolution. Neuron. 2015;88(5):861–877. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briscoe J, Ericson J. The specification of neuronal identity by graded sonic hedgehog signalling. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1999;10(3):353–362. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1999.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown RH, Al-Chalabi A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(2):162–172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1603471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burghes AH, Beattie CE. Spinal muscular atrophy: why do low levels of survival motor neuron protein make motor neurons sick? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(8):597–609. doi: 10.1038/nrn2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cabili MN, Trapnell C, Goff L, Koziol M, Tazon-Vega B, Regev A, Rinn JL. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes Dev. 2011;25(18):1915–1927. doi: 10.1101/gad.17446611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlevaro-Fita J, Rahim A, Guigo R, Vardy LA, Johnson R. Cytoplasmic long noncoding RNAs are frequently bound to and degraded at ribosomes in human cells. RNA. 2016;22(6):867–882. doi: 10.1261/rna.053561.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrieri C, Cimatti L, Biagioli M, Beugnet A, Zucchelli S, Fedele S, Pesce E, Ferrer I, Collavin L, Santoro C, Forrest AR, Carninci P, Biffo S, Stupka E, Gustincich S. Long non-coding antisense RNA controls Uchl1 translation through an embedded SINEB2 repeat. Nature. 2012;491(7424):454–457. doi: 10.1038/nature11508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaytow H, Huang YT, Gillingwater TH, Faller KME. The role of survival motor neuron protein (SMN) in protein homeostasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(21):3877–3894. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2849-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen JA, Conn S. Canonical mRNA is the exception, rather than the rule. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1268-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen JA, Huang YP, Mazzoni EO, Tan GC, Zavadil J, Wichterle H. Mir-17-3p controls spinal neural progenitor patterning by regulating Olig2/Irx3 cross-repressive loop. Neuron. 2011;69(4):721–735. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JA, Wichterle H. Apoptosis of limb innervating motor neurons and erosion of motor pool identity upon lineage specific dicer inactivation. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:69. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen LL, Carmichael GG. Altered nuclear retention of mRNAs containing inverted repeats in human embryonic stem cells: functional role of a nuclear noncoding RNA. Mol Cell. 2009;35(4):467–478. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen TH, Chen JA. Multifaceted roles of microRNAs: From motor neuron generation in embryos to degeneration in spinal muscular atrophy. Elife. 2019;8:e50848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Cheng Weiwei, Wang Shaopeng, Zhang Zhe, Morgens David W., Hayes Lindsey R., Lee Soojin, Portz Bede, Xie Yongzhi, Nguyen Baotram V., Haney Michael S., Yan Shirui, Dong Daoyuan, Coyne Alyssa N., Yang Junhua, Xian Fengfan, Cleveland Don W., Qiu Zhaozhu, Rothstein Jeffrey D., Shorter James, Gao Fen-Biao, Bassik Michael C., Sun Shuying. CRISPR-Cas9 Screens Identify the RNA Helicase DDX3X as a Repressor of C9ORF72 (GGGGCC)n Repeat-Associated Non-AUG Translation. Neuron. 2019;104(5):885-898.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung CY, Berson A, Kennerdell JR, Sartoris A, Unger T, Porta S, Kim HJ, Smith ER, Shilatifard A, Van Deerlin V, Lee VM, Chen-Plotkin A, Bonini NM. Aberrant activation of non-coding RNA targets of transcriptional elongation complexes contributes to TDP-43 toxicity. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4406. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06543-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clemson CM, Hutchinson JN, Sara SA, Ensminger AW, Fox AH, Chess A, Lawrence JB. An architectural role for a nuclear noncoding RNA: NEAT1 RNA is essential for the structure of paraspeckles. Mol Cell. 2009;33(6):717–726. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consortium EP. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414):57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper-Knock J, Higginbottom A, Stopford MJ, Highley JR, Ince PG, Wharton SB, Pickering-Brown S, Kirby J, Hautbergue GM, Shaw PJ. Antisense RNA foci in the motor neurons of C9ORF72-ALS patients are associated with TDP-43 proteinopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130(1):63–75. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1429-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.d'Ydewalle C, Ramos DM, Pyles NJ, Ng SY, Gorz M, Pilato CM, Ling K, Kong L, Ward AJ, Rubin LL, Rigo F, Bennett CF, Sumner CJ. The Antisense Transcript SMN-AS1 Regulates SMN Expression and Is a Novel Therapeutic Target for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Neuron. 2017;93(1):66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dafinca R, Scaber J, Ababneh N, Lalic T, Weir G, Christian H, Vowles J, Douglas AG, Fletcher-Jones A, Browne C, Nakanishi M, Turner MR, Wade-Martins R, Cowley SA, Talbot K. C9orf72 Hexanucleotide Expansions Are Associated with Altered Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Homeostasis and Stress Granule Formation in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Neurons from Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia. Stem Cells. 2016;34(8):2063–2078. doi: 10.1002/stem.2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dasen JS, De Camilli A, Wang B, Tucker PW, Jessell TM. Hox repertoires for motor neuron diversity and connectivity gated by a single accessory factor, FoxP1. Cell. 2008;134(2):304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, Nicholson AM, Finch NA, Flynn H, Adamson J, Kouri N, Wojtas A, Sengdy P, Hsiung GY, Karydas A, Seeley WW, Josephs KA, Coppola G, Geschwind DH, Wszolek ZK, Feldman H, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Miller BL, Dickson DW, Boylan KB, Graff-Radford NR, Rademakers R. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron. 2011;72(2):245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G, Tanzer A, Djebali S, Tilgner H, Guernec G, Martin D, Merkel A, Knowles DG, Lagarde J, Veeravalli L, Ruan X, Ruan Y, Lassmann T, Carninci P, Brown JB, Lipovich L, Gonzalez JM, Thomas M, Davis CA, Shiekhattar R, Gingeras TR, Hubbard TJ, Notredame C, Harrow J, Guigo R. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012;22(9):1775–1789. doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dodd DW, Tomchick DR, Corey DR, Gagnon KT. Pathogenic C9ORF72 Antisense Repeat RNA Forms a Double Helix with Tandem C:C Mismatches. Biochemistry. 2016;55(9):1283–1286. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donnelly CJ, Zhang PW, Pham JT, Haeusler AR, Mistry NA, Vidensky S, Daley EL, Poth EM, Hoover B, Fines DM, Maragakis N, Tienari PJ, Petrucelli L, Traynor BJ, Wang J, Rigo F, Bennett CF, Blackshaw S, Sattler R, Rothstein JD. RNA toxicity from the ALS/FTD C9ORF72 expansion is mitigated by antisense intervention. Neuron. 2013;80(2):415–428. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elden AC, Kim HJ, Hart MP, Chen-Plotkin AS, Johnson BS, Fang X, Armakola M, Geser F, Greene R, Lu MM, Padmanabhan A, Clay-Falcone D, McCluskey L, Elman L, Juhr D, Gruber PJ, Rub U, Auburger G, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Van Deerlin VM, Bonini NM, Gitler AD. Ataxin-2 intermediate-length polyglutamine expansions are associated with increased risk for ALS. Nature. 2010;466(7310):1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature09320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emde A, Eitan C, Liou LL, Libby RT, Rivkin N, Magen I, Reichenstein I, Oppenheim H, Eilam R, Silvestroni A, Alajajian B, Ben-Dov IZ, Aebischer J, Savidor A, Levin Y, Sons R, Hammond SM, Ravits JM, Moller T, Hornstein E. Dysregulated miRNA biogenesis downstream of cellular stress and ALS-causing mutations: a new mechanism for ALS. EMBO J. 2015;34(21):2633–2651. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Engreitz JM, Haines JE, Perez EM, Munson G, Chen J, Kane M, McDonel PE, Guttman M, Lander ES. Local regulation of gene expression by lncRNA promoters, transcription and splicing. Nature. 2016;539(7629):452–455. doi: 10.1038/nature20149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erb Madalynn, Lee Bora, Yeon Seo So, Lee Jae W., Lee Seunghee, Lee Soo-Kyung. The Isl1-Lhx3 Complex Promotes Motor Neuron Specification by Activating Transcriptional Pathways that Enhance Its Own Expression and Formation. eneuro. 2017;4(2):ENEURO.0349-16.2017. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0349-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faghihi MA, Modarresi F, Khalil AM, Wood DE, Sahagan BG, Morgan TE, Finch CE, St Laurent G, 3rd, Kenny PJ, Wahlestedt C. Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer's disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of beta-secretase. Nat Med. 2008;14(7):723–730. doi: 10.1038/nm1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faghihi MA, Zhang M, Huang J, Modarresi F, Van der Brug MP, Nalls MA, Cookson MR, St-Laurent G, 3rd, Wahlestedt C. Evidence for natural antisense transcript-mediated inhibition of microRNA function. Genome Biol. 2010;11(5):R56. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-r56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fratta P, Mizielinska S, Nicoll AJ, Zloh M, Fisher EM, Parkinson G, Isaacs AM. C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia forms RNA G-quadruplexes. Sci Rep. 2012;2:1016. doi: 10.1038/srep01016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Freibaum BD, Taylor JP. The Role of Dipeptide Repeats in C9ORF72-Related ALS-FTD. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:35. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao T, Li J, Li N, Gao Y, Yu L, Zhuang S, Zhao Y, Dong X. lncrps25 play an essential role in motor neuron development through controlling the expression of olig2 in zebrafish. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:3485-96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Gendron TF, Bieniek KF, Zhang YJ, Jansen-West K, Ash PE, Caulfield T, Daughrity L, Dunmore JH, Castanedes-Casey M, Chew J, Cosio DM, van Blitterswijk M, Lee WC, Rademakers R, Boylan KB, Dickson DW, Petrucelli L. Antisense transcripts of the expanded C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat form nuclear RNA foci and undergo repeat-associated non-ATG translation in c9FTD/ALS. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(6):829–844. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1192-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gendron Tania F., Chew Jeannie, Stankowski Jeannette N., Hayes Lindsey R., Zhang Yong-Jie, Prudencio Mercedes, Carlomagno Yari, Daughrity Lillian M., Jansen-West Karen, Perkerson Emilie A., O’Raw Aliesha, Cook Casey, Pregent Luc, Belzil Veronique, van Blitterswijk Marka, Tabassian Lilia J., Lee Chris W., Yue Mei, Tong Jimei, Song Yuping, Castanedes-Casey Monica, Rousseau Linda, Phillips Virginia, Dickson Dennis W., Rademakers Rosa, Fryer John D., Rush Beth K., Pedraza Otto, Caputo Ana M., Desaro Pamela, Palmucci Carla, Robertson Amelia, Heckman Michael G., Diehl Nancy N., Wiggs Edythe, Tierney Michael, Braun Laura, Farren Jennifer, Lacomis David, Ladha Shafeeq, Fournier Christina N., McCluskey Leo F., Elman Lauren B., Toledo Jon B., McBride Jennifer D., Tiloca Cinzia, Morelli Claudia, Poletti Barbara, Solca Federica, Prelle Alessandro, Wuu Joanne, Jockel-Balsarotti Jennifer, Rigo Frank, Ambrose Christine, Datta Abhishek, Yang Weixing, Raitcheva Denitza, Antognetti Giovanna, McCampbell Alexander, Van Swieten John C., Miller Bruce L., Boxer Adam L., Brown Robert H., Bowser Robert, Miller Timothy M., Trojanowski John Q., Grossman Murray, Berry James D., Hu William T., Ratti Antonia, Traynor Bryan J., Disney Matthew D., Benatar Michael, Silani Vincenzo, Glass Jonathan D., Floeter Mary Kay, Rothstein Jeffrey D., Boylan Kevin B., Petrucelli Leonard. Poly(GP) proteins are a useful pharmacodynamic marker forC9ORF72-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science Translational Medicine. 2017;9(383):eaai7866. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goodman LD, Prudencio M, Kramer NJ, Martinez-Ramirez LF, Srinivasan AR, Lan M, Parisi MJ, Zhu Y, Chew J, Cook CN, Berson A, Gitler AD, Petrucelli L, Bonini NM. Toxic expanded GGGGCC repeat transcription is mediated by the PAF1 complex in C9orf72-associated FTD. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(6):863–874. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0396-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goudarzi M, Berg K, Pieper LM, Schier AF. Individual long non-coding RNAs have no overt functions in zebrafish embryogenesis, viability and fertility. Elife. 2019;8:e40815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Goyal A, Myacheva K, Gross M, Klingenberg M, Duran AB, Diederichs S. Challenges of CRISPR/Cas9 applications for long non-coding RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(3):e12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hacisuleyman E, Goff LA, Trapnell C, Williams A, Henao-Mejia J, Sun L, McClanahan P, Hendrickson DG, Sauvageau M, Kelley DR, Morse M, Engreitz J, Lander ES, Guttman M, Lodish HF, Flavell R, Raj A, Rinn JL. Topological organization of multichromosomal regions by the long intergenic noncoding RNA Firre. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21(2):198–206. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haeusler AR, Donnelly CJ, Periz G, Simko EA, Shaw PG, Kim MS, Maragakis NJ, Troncoso JC, Pandey A, Sattler R, Rothstein JD, Wang J. C9orf72 nucleotide repeat structures initiate molecular cascades of disease. Nature. 2014;507(7491):195–200. doi: 10.1038/nature13124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoye ML, Koval ED, Wegener AJ, Hyman TS, Yang C, O'Brien DR, Miller RL, Cole T, Schoch KM, Shen T, Kunikata T, Richard JP, Gutmann DH, Maragakis NJ, Kordasiewicz HB, Dougherty JD, Miller TM. MicroRNA Profiling Reveals Marker of Motor Neuron Disease in ALS Models. J Neurosci. 2017;37(22):5574–5586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3582-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Imamura K, Imamachi N, Akizuki G, Kumakura M, Kawaguchi A, Nagata K, Kato A, Kawaguchi Y, Sato H, Yoneda M, Kai C, Yada T, Suzuki Y, Yamada T, Ozawa T, Kaneki K, Inoue T, Kobayashi M, Kodama T, Wada Y, Sekimizu K, Akimitsu N. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1-dependent SFPQ relocation from promoter region to paraspeckle mediates IL8 expression upon immune stimuli. Mol Cell. 2014;53(3):393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell. 2011;147(4):789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.International Human Genome Sequencing C Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature. 2004;431(7011):931–945. doi: 10.1038/nature03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iyer MK, Niknafs YS, Malik R, Singhal U, Sahu A, Hosono Y, Barrette TR, Prensner JR, Evans JR, Zhao S, Poliakov A, Cao X, Dhanasekaran SM, Wu YM, Robinson DR, Beer DG, Feng FY, Iyer HK, Chinnaiyan AM. The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat Genet. 2015;47(3):199–208. doi: 10.1038/ng.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang J, Zhu Q, Gendron TF, Saberi S, McAlonis-Downes M, Seelman A, Stauffer JE, Jafar-Nejad P, Drenner K, Schulte D, Chun S, Sun S, Ling SC, Myers B, Engelhardt J, Katz M, Baughn M, Platoshyn O, Marsala M, Watt A, Heyser CJ, Ard MC, De Muynck L, Daughrity LM, Swing DA, Tessarollo L, Jung CJ, Delpoux A, Utzschneider DT, Hedrick SM, de Jong PJ, Edbauer D, Van Damme P, Petrucelli L, Shaw CE, Bennett CF, Da Cruz S, Ravits J, Rigo F, Cleveland DW, Lagier-Tourenne C. Gain of Toxicity from ALS/FTD-Linked Repeat Expansions in C9ORF72 Is Alleviated by Antisense Oligonucleotides Targeting GGGGCC-Containing RNAs. Neuron. 2016;90(3):535–550. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kallen AN, Zhou XB, Xu J, Qiao C, Ma J, Yan L, Lu L, Liu C, Yi JS, Zhang H, Min W, Bennett AM, Gregory RI, Ding Y, Huang Y. The imprinted H19 lncRNA antagonizes let-7 microRNAs. Mol Cell. 2013;52(1):101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khong A, Matheny T, Jain S, Mitchell SF, Wheeler JR, Parker R. The Stress Granule Transcriptome Reveals Principles of mRNA Accumulation in Stress Granules. Mol Cell. 2017;68(4):808–820 e805. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khorkova O, Myers AJ, Hsiao J, Wahlestedt C. Natural antisense transcripts. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(R1):R54–R63. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kovanda A, Zalar M, Sket P, Plavec J, Rogelj B. Anti-sense DNA d(GGCCCC)n expansions in C9ORF72 form i-motifs and protonated hairpins. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17944. doi: 10.1038/srep17944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kramer NJ, Carlomagno Y, Zhang YJ, Almeida S, Cook CN, Gendron TF, Prudencio M, Van Blitterswijk M, Belzil V, Couthouis J, Paul JW, 3rd, Goodman LD, Daughrity L, Chew J, Garrett A, Pregent L, Jansen-West K, Tabassian LJ, Rademakers R, Boylan K, Graff-Radford NR, Josephs KA, Parisi JE, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Boeve BF, Deng N, Feng Y, Cheng TH, Dickson DW, Cohen SN, Bonini NM, Link CD, Gao FB, Petrucelli L, Gitler AD. Spt4 selectively regulates the expression of C9orf72 sense and antisense mutant transcripts. Science. 2016;353(6300):708–712. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kretz M, Siprashvili Z, Chu C, Webster DE, Zehnder A, Qu K, Lee CS, Flockhart RJ, Groff AF, Chow J, Johnston D, Kim GE, Spitale RC, Flynn RA, Zheng GX, Aiyer S, Raj A, Rinn JL, Chang HY, Khavari PA. Control of somatic tissue differentiation by the long non-coding RNA TINCR. Nature. 2013;493(7431):231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature11661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krzyzosiak WJ, Sobczak K, Wojciechowska M, Fiszer A, Mykowska A, Kozlowski P. Triplet repeat RNA structure and its role as pathogenic agent and therapeutic target. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(1):11–26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kung JT, Kesner B, An JY, Ahn JY, Cifuentes-Rojas C, Colognori D, Jeon Y, Szanto A, del Rosario BC, Pinter SF, Erwin JA, Lee JT. Locus-specific targeting to the X chromosome revealed by the RNA interactome of CTCF. Mol Cell. 2015;57(2):361–375. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kwon I, Xiang S, Kato M, Wu L, Theodoropoulos P, Wang T, Kim J, Yun J, Xie Y, McKnight SL. Poly-dipeptides encoded by the C9orf72 repeats bind nucleoli, impede RNA biogenesis, and kill cells. Science. 2014;345(6201):1139–1145. doi: 10.1126/science.1254917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laver JD, Li X, Ancevicius K, Westwood JT, Smibert CA, Morris QD, Lipshitz HD. Genome-wide analysis of Staufen-associated mRNAs identifies secondary structures that confer target specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(20):9438–9460. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee S, Cuvillier JM, Lee B, Shen R, Lee JW, Lee SK. Fusion protein Isl1-Lhx3 specifies motor neuron fate by inducing motor neuron genes and concomitantly suppressing the interneuron programs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(9):3383–3388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114515109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lefebvre S, Burglen L, Reboullet S, Clermont O, Burlet P, Viollet L, Benichou B, Cruaud C, Millasseau P, Zeviani M, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995;80(1):155–165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li CJ, Hong T, Tung YT, Yen YP, Hsu HC, Lu YL, Chang M, Nie Q, Chen JA. MicroRNA filters Hox temporal transcription noise to confer boundary formation in the spinal cord. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14685. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li PP, Sun X, Xia G, Arbez N, Paul S, Zhu S, Peng HB, Ross CA, Koeppen AH, Margolis RL, Pulst SM, Ashizawa T, Rudnicki DD. ATXN2-AS, a gene antisense to ATXN2, is associated with spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(4):600–615. doi: 10.1002/ana.24761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li W, Notani D, Rosenfeld MG. Enhancers as non-coding RNA transcription units: recent insights and future perspectives. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(4):207–223. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu JP, Laufer E, Jessell TM. Assigning the positional identity of spinal motor neurons: rostrocaudal patterning of Hox-c expression by FGFs, Gdf11, and retinoids. Neuron. 2001;32(6):997–1012. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00544-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu Y, Pattamatta A, Zu T, Reid T, Bardhi O, Borchelt DR, Yachnis AT, Ranum LP. C9orf72 BAC Mouse Model with Motor Deficits and Neurodegenerative Features of ALS/FTD. Neuron. 2016;90(3):521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lo PL, Yamaguchi M. RNAi of arcRNA hsromega affects sub-cellular localization of Drosophila FUS to drive neurodiseases. Exp Neurol. 2017;292:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lopez-Gonzalez R, Lu Y, Gendron TF, Karydas A, Tran H, Yang D, Petrucelli L, Miller BL, Almeida S, Gao FB. Poly(GR) in C9ORF72-Related ALS/FTD Compromises Mitochondrial Function and Increases Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage in iPSC-Derived Motor Neurons. Neuron. 2016;92(2):383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Luke B, Lingner J. TERRA: telomeric repeat-containing RNA. EMBO J. 2009;28(17):2503–2510. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lunn MR, Wang CH. Spinal muscular atrophy. Lancet. 2008;371(9630):2120–2133. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60921-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mackenzie IR, Frick P, Grasser FA, Gendron TF, Petrucelli L, Cashman NR, Edbauer D, Kremmer E, Prudlo J, Troost D, Neumann M. Quantitative analysis and clinico-pathological correlations of different dipeptide repeat protein pathologies in C9ORF72 mutation carriers. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130(6):845–861. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maharana S, Wang J, Papadopoulos DK, Richter D, Pozniakovsky A, Poser I, Bickle M, Rizk S, Guillen-Boixet J, Franzmann TM, Jahnel M, Marrone L, Chang YT, Sterneckert J, Tomancak P, Hyman AA, Alberti S. RNA buffers the phase separation behavior of prion-like RNA binding proteins. Science. 2018;360(6391):918–921. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Majounie E., Renton A.E., Mok K., Dopper E.G., Waite A., Rollinson S., Chio A., Restagno G., Nicolaou N., Simon-Sanchez J., van Swieten J.C., Abramzon Y., Johnson J.O., Sendtner M., Pamphlett R., Orrell R.W., Mead S., Sidle K.C., Houlden H., Rohrer J.D., Morrison K.E., Pall H., Talbot K., Ansorge O., Chromosome A.L.S.F.T.D.C., French research network on F.F.A, Consortium I., Hernandez D.G., Arepalli S., Sabatelli M., Mora G., Corbo M., Giannini F., Calvo A., Englund E., Borghero G., Floris G.L., Remes A.M., Laaksovirta H., McCluskey L., Trojanowski J.Q., Van Deerlin V.M., Schellenberg G.D., Nalls M.A., Drory V.E., Lu C.S., Yeh T.H., Ishiura H., Takahashi Y., Tsuji S., Le Ber I., Brice A., Drepper C., Williams N., Kirby J., Shaw P., Hardy J., Tienari P.J., Heutink P., Morris H.R., Pickering-Brown S. and Traynor B.J. Frequency of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol 11(4):323-330, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Maniatis S, Aijo T, Vickovic S, Braine C, Kang K, Mollbrink A, Fagegaltier D, Andrusivova Z, Saarenpaa S, Saiz-Castro G, Cuevas M, Watters A, Lundeberg J, Bonneau R, Phatnani H. Spatiotemporal dynamics of molecular pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2019;364(6435):89–93. doi: 10.1126/science.aav9776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McHugh CA, Chen CK, Chow A, Surka CF, Tran C, McDonel P, Pandya-Jones A, Blanco M, Burghard C, Moradian A, Sweredoski MJ, Shishkin AA, Su J, Lander ES, Hess S, Plath K, Guttman M. The Xist lncRNA interacts directly with SHARP to silence transcription through HDAC3. Nature. 2015;521(7551):232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature14443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mehler MF, Mabie PC, Zhang DM, Kessler JA. Bone morphogenetic proteins in the nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20(7):309–317. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)01046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Sunkin SM, Mehler MF, Mattick JS. Specific expression of long noncoding RNAs in the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(2):716–721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706729105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Militello G, Hosen MR, Ponomareva Y, Gellert P, Weirick T, John D, Hindi SM, Mamchaoui K, Mouly V, Doring C, Zhang L, Nakamura M, Kumar A, Fukada SI, Dimmeler S, Uchida S. A novel long non-coding RNA Myolinc regulates myogenesis through TDP-43 and Filip1. J Mol Cell Biol. 2018;10(2):102–117. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjy025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mizielinska S, Gronke S, Niccoli T, Ridler CE, Clayton EL, Devoy A, Moens T, Norona FE, Woollacott IOC, Pietrzyk J, Cleverley K, Nicoll AJ, Pickering-Brown S, Dols J, Cabecinha M, Hendrich O, Fratta P, Fisher EMC, Partridge L, Isaacs AM. C9orf72 repeat expansions cause neurodegeneration in Drosophila through arginine-rich proteins. Science. 2014;345(6201):1192–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1256800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mizielinska S, Lashley T, Norona FE, Clayton EL, Ridler CE, Fratta P, Isaacs AM. C9orf72 frontotemporal lobar degeneration is characterised by frequent neuronal sense and antisense RNA foci. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(6):845–857. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1200-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mizielinska S, Ridler CE, Balendra R, Thoeng A, Woodling NS, Grasser FA, Plagnol V, Lashley T, Partridge L, Isaacs AM. Bidirectional nucleolar dysfunction in C9orf72 frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0432-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moens TG, Mizielinska S, Niccoli T, Mitchell JS, Thoeng A, Ridler CE, Gronke S, Esser J, Heslegrave A, Zetterberg H, Partridge L, Isaacs AM. Sense and antisense RNA are not toxic in Drosophila models of C9orf72-associated ALS/FTD. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;135(3):445–457. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1798-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mori K, Arzberger T, Grasser FA, Gijselinck I, May S, Rentzsch K, Weng SM, Schludi MH, van der Zee J, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C, Kremmer E, Kretzschmar HA, Haass C, Edbauer D. Bidirectional transcripts of the expanded C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat are translated into aggregating dipeptide repeat proteins. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126(6):881–893. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]