Abstract

Murine typhus is a tropical disease caused by Rickettsia typhi and is endemic in resource-limited settings such as Southeast Asian countries. Early diagnosis of R. typhi infection facilitates appropriate management and reduces the risk of severe disease. However, molecular detection of R. typhi in blood is insensitive due to low rickettsemia. Furthermore, the gold standard of sero-diagnosis by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) is cumbersome, subjective, impractical, and unavailable in many endemic areas. In an attempt to identify a practical diagnostic approach that can be applied in Indonesia, we evaluated the performance of commercial R. typhi IgM and IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and IFA using paired plasma from previously studied R. typhi PCR-positive cases and controls with other known infections. Sensitivity and specificity of combined ELISA IgM and IgG anti-R. typhi using paired specimens were excellent (95.0% and 98.3%, respectively), comparable to combined IFA IgM and IgG (97.5% and 100%, respectively); sensitivity of ELISA IgM from acute specimens only was poor (45.0%), but specificity was excellent (98.3%). IFA IgM was more sensitive (77.5%), but less specific (89.7%) for single specimens.

Keywords: validation, Rickettsia typhi, Indonesia, immunofluorescence assay (IFA), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Introduction

Murine typhus is a disease caused by an intracellular gram-negative bacteria called Rickettsia typhi, and manifested clinically with acute fever, chills, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, cough, and rash (Aung et al. 2014). It has a worldwide distribution, though outbreaks are more common in Southeast Asia, Northern Africa, and North America. Most R. typhi cases occur in areas with large rat populations (Tsioutis et al. 2017). R. typhi infection should be treated promptly to prevent complications that may involve liver, kidneys, lungs, brain, and heart (Aung et al. 2014). Appropriate rapid diagnostics are needed to distinguish it from other tropical infections, as patient management varies. Due to low rickettsemia during acute illness, the sensitivity of real-time PCR is highly variable. Thus, sero-diagnosis using immunofluorescence assay (IFA) remains the gold standard. However, IFA has several disadvantages, including need for a fluorescence microscope, which is often unavailable in endemic resource-limited settings such as Southeast Asian countries, and experienced technicians. Automated microscopy is an alternative that reduces subjectivity, but the cost is prohibitive. R. typhi IgM and IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) are more feasible in resource-limited settings. However, little data are available on ELISA performance with well-characterized patient sera (Paris and Dumler 2016).

Materials and Methods

Main study

Samples used for this study were obtained as part of a longitudinal study on acute fever requiring hospitalization/AFIRE study (NCT02763462), which has been described previously (Lie et al. 2018). This study was conducted by the Indonesia Research Partnership on Infectious Disease (INA-RESPOND) (Karyana et al. 2015), recruiting participants at eight government referral teaching hospitals in seven provincial capitals (Jakarta, Bandung, Semarang, Yogyakarta, Surabaya, Denpasar, and Makassar). Participants were enrolled between July 2013 and June 2016. Acute plasma was collected within 24 h after admission, and convalescent plasma was collected 14–28 days later. Clinical data, including day of fever onset and results from standard-of-care diagnostic examination at the hospitals, were collected. This study was approved by the IRB of Dr. Soetomo Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, and the National Institute of Health Research and Development, Ministry of Health, Indonesia.

Study groups

Paired acute and convalescent plasma samples from 40 cases with confirmed R. typhi and 58 controls with another confirmed infection were used to evaluate the performance of commercial IgM and IgG ELISA and IFA. The 58 paired plasma specimens that we used for controls were negative for R. typhi and Rickettsia spp., but positive for other pathogens by culture or molecular testing (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pathogens Identified in the Serum Samples Used as Controls

| Confirmed pathogen | No. | Method of confirmation |

|---|---|---|

| Dengue | 13 | RT-PCR and serology |

| Dengue serotype 1 | 4 | |

| Dengue serotype 2 | 2 | |

| Dengue serotype 3 | 7 | |

| Leptospira spp. | 8 | PCR and serology |

| Chikungunya | 7 | RT-PCR and serology |

| Salmonella typhi | 4 | Blood culture, PCR (2) |

| Salmonella paratyphi A | Blood culture (2) | |

| 1 | Blood culture (1) | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 5 | PCR (blood) |

| Entamoeba coli | 4 | Feces, microscopy |

| Influenza (A/H3N2 and B) | 3 | Sputum, RT-PCR |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2 | Throat swab (1), sputum culture (1) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 2 | Sputum culture (1), PCR and sequencing (1) |

| Escherichia coli | 1 | Blood culture |

| Measles | 1 | RT-PCR and serology |

| Streptococcus viridans | 1 | Blood culture |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 1 | Sputum culture |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 | Blood culture |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 | Sputum culture |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 | Sputum culture |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 1 | Blood culture |

| HHV-6 | 1 | Quantitative RT-PCR, sequencing |

Case identification by R. typhi PCR

Bacterial DNA from 200 μL of acute plasma and buffy coat was extracted using the QIAamp Bacterial DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) per manufacturer's protocol. The real-time PCR for Rickettsia spp. detection targets are the 17-kD outer membrane protein (omp) gene of genus Rickettsia (Jiang et al. 2012) and the outer membrane protein B (ompB) gene of R. typhi (Henry et al. 2007). Of 40 identified R. typhi cases, 28 were positive for Rickettsia spp. and Rickettsia typhi, and 12 for R. typhi only. DNA sequencing targeting a 743-bp fragment of the ompB gene successfully sequenced in 16 specimens, all of which were most homologous to R. typhi strain B 9991 CWPP. No other pathogens were identified based on blood culture, sputum culture (if available), and molecular and/or serological assays for dengue, chikungunya, and influenza viruses, Salmonella spp., and Leptospira spp.

Immunofluorescence Assay

IFA was performed per manufacturer's specifications using kits from Focus Diagnostics® (California) (Kantso et al. 2009). The dilution for study samples was 1:64, and for provided positive controls was 1:32. Acute and convalescent specimens from each subject were performed simultaneously. The IFA slides were examined by fluorescence microscopy (Nikon) at a magnification of 200 × . The positive control provided by the manufacturer was considered the cutoff (1+ apple green fluorescence of Rickettsial bodies). Fluorescence that did not match the morphology and distribution of the positive control was considered negative. Slides were independently examined by three trained technicians. Discrepant results, defined as disagreement about negative or positive results, or between positivity grades (1, 2, 3, 4) among raters, were adjudicated by the Indonesia Research Partnership on Infectious Diseases (INA-RESPOND) laboratory chief. Of the 40 paired specimens used as R. typhi cases for this validation, 35 R. typhi cases showed ≥4-fold increase in IFA IgM, and 5 R. typhi cases showed a <4-fold increase but very high titers (1: 8192 to 1:16384).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Acute and convalescent plasma were tested simultaneously using kits from Fuller Laboratories® (California) per manufacturer's instructions. Microwells were coated with rOmp B purified from R. typhi. To test for IgM, 6-μL patient plasma was diluted in 54-μL IgM plasma preparation (buffer containing goat anti-human Fc(γ)-specific IgG), which aggregates IgG and rheumatoid factor, followed by a further 1:10 dilution in sample diluent for a final plasma dilution of 1:100. For IgG, plasma was diluted 1:100 in sample diluent. After a 60-min incubation at room temperature, microwells were washed. A peroxidase-labeled goat anti-human IgM or IgG, tetramethylbenzidine substrate, and sulfuric acid were used to detect positive reaction. Optical density (OD) was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm (Multiskan GO; ThermoFisher Scientific, Vantaa, Finland). The index sample (INDX) was calculated by comparing the sample OD with the mean of cut-off calibration OD; INDX ≥1.1 for IgM and INDX ≥1.2 for IgG were considered positive.

Sensitivity and specificity analysis

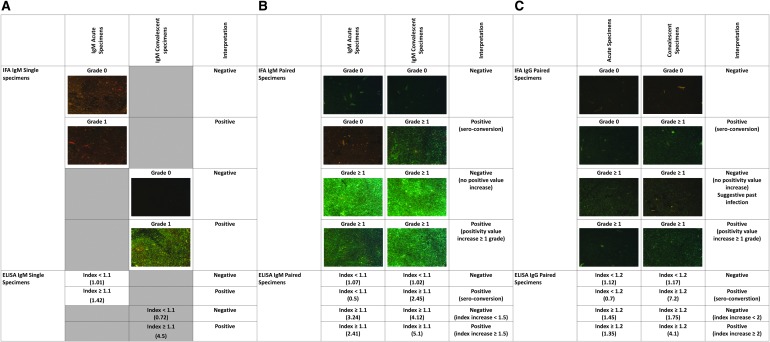

To evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of ELISA and IFA in the detection of early rickettsial infection, we looked at the performance of IgM in only acute specimens for cases and controls. IgM was considered positive when INDX was ≥1.1 (ELISA) or when fluorescence of rickettsial bodies was detected (positivity grade 1). In addition, the performance of IgM in only convalescent specimens using similar positivity criteria as above was evaluated (Fig. 1). The performance of paired specimens was also analyzed to assess utility in confirming a diagnosis. IFA was considered positive when IgM and/or IgG sero-conversion was identified (Fig. 1) or there was an increase in positivity grade between acute and convalescent specimens (Fig. 1); otherwise the specimens were considered negative. ELISA was considered positive if any of the following occurred: (1) sero-conversion of IgM (index <1.1 in acute to ≥1.1 in convalescent) or 1.5-fold increase in INDX between acute and convalescent specimens, (2) sero-conversion of IgG (index <1.2 in acute to ≥1.2 in convalescent) or twofold increase in INDX between acute and convalescent specimens (Fig. 1). These increased IgM and IgG cut-offs (1.5- and 2-fold, respectively) were calculated using a receiver operating characteristic curve, with sensitivity of 97.5% and 100% and specificity of 96.6% and 96.5%, respectively. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA® 12 (StataCorp LLC, Texas).

FIG. 1.

Criteria to interpret the results of IFA and ELISA IgM in single acute or convalescent specimens (A), IFA and ELISA IgM using paired acute and convalescent specimens (B), and IFA and ELISA IgG using paired specimens (C). The number in parentheses shows IgM/IgG positivity grade for IFA and IgM/IgG index for ELISA results. ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IFA, immunofluorescence assay.

Results

Day of fever onset

The mean days of fever at time of acute and convalescent specimen collection was significantly longer among cases compared with controls (acute specimens: 6.8 [95% confidence interval, 6.3–7.4] vs. 4.5 [3.8–5.2] days, p < 0.01; convalescent specimens: 29.1 [27.2–30.9] vs. 26.1 [24.5–27.7] days, p < 0.01).

IgM sensitivity

Among R. typhi cases, IFA was more sensitive than ELISA (31 of 40 [77.5%] vs. 18 of 40 [45%], p < 0.01) for the detection of IgM in acute specimens.

Twenty-one of 22 acute specimens with negative ELISA IgM demonstrated sero-conversion in the corresponding convalescent specimens. In the case without IgM sero-conversion, IgG sero-converted. Among 18 cases with detected ELISA IgM in acute specimens, INDX values increased in 17 convalescent specimens between 1.6 and 6.2-fold (3.4 [2.8–4.0]); IgM in the other case did not change though IgG increased 6.8-fold. Similarly, all nine negative acute specimen IFAs sero-converted in the convalescent specimen. In 31 cases with positive acute specimen IFA IgM, 30 showed increased positivity grade and the other case manifested very high IFA IgM positivity in both acute and convalescent specimens.

IgM specificity

Among 58 paired control specimens, IFA and ELISA assays did not detect IgM in 52 and 57 acute specimens, respectively. Neither detected IgM in 53 of 58 convalescent specimens provided a better specificity for ELISA (98.3%) than IFA (89.7%) (p = 0.052) in acute specimens but the same specificity (91.4%) in convalescent specimens. No false-positive was confirmed by both assays.

Sensitivity and specificity in paired specimens

Using the criteria described in the methods, sensitivities of IFA IgM were slightly better compared with ELISA IgM (97.5% vs. 95.0%, respectively), but similar (100%) for both IFA and ELISA IgG.

Paired control specimens demonstrated perfect specificity for IFA IgM (100%), which was significantly better than the specificity of ELISA IgM (93.1%) (p < 0.05). In contrast, the specificity of IgG was lower than for IgM for both IFA and ELISA. Although the point estimate for specificity of IFA IgG (91.4%) was better than for ELISA IgG (82.8%), the difference was not significant (p = 0.16). In five controls that showed increased positivity grade, the titers in convalescent specimens only rose a maximum of twofold. One control sero-converted by both ELISA IgM and IgG; however, only IFA IgG showed a twofold increase.

Sensitivity and specificity results of acute, convalescent, and paired specimens for IFA and ELISA are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and Specificity of Immunofluorescence Assay and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay in Acute, Convalescent, and Paired Specimens

| Single specimens |

Paired specimens (acute and convalescent) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | Convalescent | |||

| Sensitivity (n = 40) | IgM (+) | IgM (+) | IgM (+) | IgG (+) |

| IFA, % (n) | 77.5 (31) | 100 (40) | 97.5 (39) | 100 (40) |

| ELISA, % (n) | 45.0 (18) | 97.5 (39) | 95.0 (38) | 100 (40) |

| Specificity (n = 58) | IgM (−) | IgM (−) | IgM (+) | IgG (+) |

| IFA, % (n) | 89.7 (52)a | 91.4 (53)c | 100 (58) | 91.4 (53)f |

| ELISA, % (n) | 98.3 (57)b | 91.4 (53)d | 93.1 (54)e | 82.8 (48)g |

Criteria to interpret IFA and ELISA results are described in the Materials and Methods section and Figure 1.

Pathogens from controls incorrectly identified as Rickettsia typhi (false-positive) are:

Six cases: Salmonella typhi (2), Streptococcus viridans, Streptococcus pneumoniae, chikungunya, DENV-3 (one each).

One case: DENV-1.

Five cases: S. typhi (2), S. viridans, DENV-3, chikungunya (one each).

Five cases: DENV-1 (2), leptospira (2), DENV-3 (1).

Four cases: Leptospira spp. (2), DENV-1 (1), DENV-3 (1).

Five cases: Leptospira spp. (2), Salmonella typhi (1), Streptococcus pneumoniae (1), chikungunya (1).

Ten cases: Leptospira spp. (4), Streptococcus pneumoniae (3), Salmonella typhi, DENV-3, chikungunya (one each).

ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IFA, immunofluorescence assay.

Kinetics of R. typhi IgM and IgG antibodies

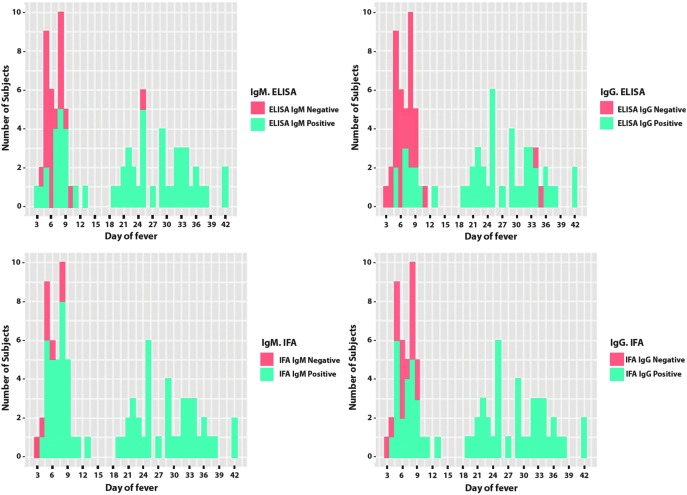

IgM and IgG results by IFA and ELISA of acute and convalescent specimens from 40 confirmed R. typhi cases were plotted by day of fever when the specimens were obtained (Fig. 2). IgM was detected as early as day 3 of fever by ELISA and day 4 by IFA. Starting from day 9 of illness, IgM was detected in all cases by IFA, while ELISA missed two specimens (days 10 and 25). A majority of cases already had IgG in the acute specimens, starting from day 4 of fever. All convalescent specimens had IgG detected by IFA, while two specimens were missed by ELISA.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of Rickettsia typhi IgM antibodies (left) and R. typhi IgG antibodies (right) as detected by ELISA (top) or IFA (bottom) in 40 paired acute and convalescent specimens obtained from molecularly confirmed R. typhi infections. Two specimens missed ELISA for IgM (left above, arrow): first case: IgM was negative in acute (day 10) specimen but sero-converted in convalescent (day 38) specimen; second case: IgM was negative both in acute and convalescent (day 25) specimen. However, ELISA IgG INDX increased >2, IFA IgM increased from 2 to 4, and IFA IgG from 1 to 3. These may be associated with less sensitivity of the kit, delayed occurrence of IgM, or, in the second case, IgM has reached the peak and declined during convalescence. In the two cases with undetected ELISA IgG in convalescent specimens (right above, arrow), INDX IgG was just slightly below the cut-off (1.19 on day 34, and 1.18 on day 35, respectively). In these two cases, ELISA IgM was sero-converted (INDX 0.6–1.54) or increased (INDX 1.4–6.2) as well as IFA IgM (grades 1–3, and grades 1–4, respectively), and IFA IgG (grades 0–2, and grades 1–3, respectively). This may be due to sensitivity issue, declining IgG in late convalescent specimens, or variance between assays.

Discussion

Serologic assays for the diagnosis of R. typhi infection remain essential as molecular assays perform suboptimally with low-level rickettsemia. Furthermore, serologic assays are currently more feasible in a resource-limited country such as Indonesia. Our study evaluated the sensitivity of ELISA and IFA R. typhi antibody assays using confirmed R. typhi cases and specificity of the assays using cases with other confirmed infections. We found that IFA IgM using paired specimens was the best performer with sensitivity and specificity >95%. IFA IgG using paired specimens was equally sensitive but less specific than IFA IgM. The sensitivities of ELISA IgM and IgG using paired specimens were also excellent, but the specificities were lower. The specificity of ELISA IgM and ELISA IgG may be improved by requiring that sero-conversion also have a greater INDX increase, whereas IFA IgG requires a >1 positivity grade increase. A previous study in endemic settings used the criteria of sero-conversion with a twofold increased titer (Reller et al. 2016).

When paired specimens are not available, IFA and ELISA IgG should not be used because these are confounded by high background IgG, as demonstrated by our control group. ELISA IgM and IFA IgM in convalescent specimens performed best, with a sensitivity of 97.5–100% and specificity of 91.4% for both assays. However, the specificities of ELISA and IFA IgM improved by increasing this cut-off without losing sensitivity, as four of five specimens showed low IgM INDX or positivity grade. The detection of low-level IgM may be associated with cross-reactivity with antibodies from infections with other Rickettsia species such as Rickettsia prowazekii (La Scola et al. 2000), Rickettsia felis (Lim et al. 2012), and Rickettsia rickettsi, or other pathogens such as Salmonella spp. and Orientia tsutsugamuchi (Kelly et al. 1995), and/or the remaining IgM from previous R. typhi infection that may still be detectable after 12 months (Kelly et al. 1995).

Since symptomatic R. typhi infection should be treated early to prevent complications and only acute specimens are available when management decisions must be made, the performance of acute specimens is critical. Without accurate diagnostics for acute disease, many patients will be treated empirically when infection is suspected, exposing them to complications of potentially unnecessary treatment and contributing to antimicrobial overuse. For testing acute specimens, IFA remains the recommended test with sensitivity and specificity of 77.5% and 89.7%, respectively. ELISA IgM showed poor sensitivity, suggesting that this assay is not good for screening, though a positive result is highly specific for acute infection. In our study, although IgM may be detected as early as day 3 by ELISA or day 4 by IFA, the chance of IgM detection was high starting on day 5 by IFA and on day 7 by ELISA. This is shorter than reported previously (Biggs et al. 2016). Based on excellent specificity, patients with positive R. typhi IgM by ELISA or IFA should be treated immediately by antibiotics. In addition, negative IgM antibody at <7 days of fever should be retested in later specimens to rule out R. typhi infection.

We also observed the appearance of IgG early in the absence of IgM. This may suggest that IgG in R. typhi infection is produced almost at the same time as IgM (Blanton 2016), and/or the IgG was from past rickettsial infection, suggesting an anamnestic response due to reinfection. This is plausible since R. typhi and other rickettsiae and their vectors are endemic in Indonesia. Also, the detection of IgG in the control group supports endemicity of R. typhi in Indonesia. To better understand the kinetics of R. typhi IgM and IgG, future studies should enroll patients early after onset of fever.

The validation of IFA and ELISA in diagnosing R. typhi infection has not been done using well-characterized acute and convalescent specimens. Thus, it is difficult to compare our results with previous reports. A study in northern Vietnam compared Focus IFA IgG to the in-house IFA IgG, which showed 100% concordance (Hamaguchi et al. 2015). Another report reviewed by Paris and Dumler (2016) suggested results comparable to ours; however, details on the specimens and assays are unavailable. Despite lack of validation, Focus IFA and Fuller ELISA kits have been used in several studies and for surveillance (Reller et al. 2012, Capeding et al. 2013, Mane et al. 2019). Our study provides valuable guidance to laboratories in the selection of diagnostics based on available resources.

This study had several limitations. First, all samples were taken from patients who were hospitalized for febrile illness. It is possible that the IFA and ELISA perform differently in other populations or that antibody kinetics might vary. Second, the use of only two paired specimens, as opposed to daily or semi-weekly ones, limited the assessment of antibody kinetics and relationship to fever. Third, we did not perform the IFA or ELISA until the end of dilution. Thus, we could not analyze the correlation of the titers using both methods. However, the use of INDX (ELISA) or positivity grade (IFA) increase is less costly and more applicable in the hospital setting. Fourth, we did not perform tests using different production lots. Thus, we may have overlooked variation associated with the manufacturing process (reproducibility of the data), which would influence guidance on diagnostics. Fifth, we did not have specimens from other rickettsial infections and therefore could not analyze cross-reactivity within this group. Last, it is possible that controls with R. typhi IgM detected by IFA or ELISA were actually infected with R. typhi, though this is unlikely as other infecting pathogens were identified by molecular or culture methods and R. typhi DNA was not detected by real-time PCR amplification using both R. typhi and Rickettsia spp. primers. The detection of IgM might be due to cross-reactivity with other pathogens or persistence of R. typhi IgM from previous infection.

Conclusion

We characterized the performance of ELISA and IFA in the diagnosis of R. typhi infections using plasma from cases with confirmed R. typhi infection and controls with other confirmed infections. Our data support the validity of ELISA in the diagnosis of R. typhi infection. As the specificity in acute specimens as well as sensitivity and specificity in convalescent specimens and paired specimens were excellent, ELISA is recommended when fluorescence microscopy is not feasible. However, IFA remains the method of choice if resources are available. ELISA is appropriate for resource-limited settings as it is easy to read, is objective, and has a high throughput. A larger prospective study in endemic areas that addresses the limitations of our study may further inform diagnostics for R. typhi infection.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the AFIRE study teams from all hospitals in INA-RESPOND network; Susana Widjaja for her critical input to the article; and Helmi Aziz, Aly Diana, and Nurhayati for their technical assistance. This project has been funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, under contract nos. HHSN261200800001E and HHSN261201500003I.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- Aung AK, Spelman DW, Murray RJ, Graves S. Rickettsial infections in Southeast Asia: Implications for local populace and febrile returned travelers. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014; 91:451–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs HM, Behravesh CB, Bradley KK, Dahlgren FS, et al. Diagnosis and management of tickborne rickettsial diseases: Rocky mountain spotted fever and other spotted fever group rickettsioses, ehrlichioses, and anaplasmosis—United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016; 65:1–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton LS. Rickettsiales: Laboratory Diagnosis. S. Thomas. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Capeding MR, Chua MN, Hadinegoro SR, Hussain II, et al. A. Wartel. Dengue and other common causes of acute febrile illness in Asia: An active surveillance study in children. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7:e2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi S, Cuong NC, Tra DT, Doan YH, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of scrub typhus and murine typhus among hospitalized patients with acute undifferentiated fever in Northern Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 92:972–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KM, Jiang J, Rozmajzl PJ, Azad AF, et al. Development of quantitative real-time PCR assays to detect Rickettsia typhi and Rickettsia felis, the causative agents of murine typhus and flea-borne spotted fever. Mol Cell Probes 2007; 21:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Stromdahl EY, Richards AL. Detection of Rickettsia parkeri and Candidatus Rickettsia andeanae in Amblyomma maculatum Gulf Coast ticks collected from humans in the United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2012; 12:175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantsø B, Svendsen CB, Jørgensen S, Krogfelt KA. Evaluation of serological tests for the diagnosis of rickettsiosis in Denmark. J Microbiol Meth 2009; 76:285–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karyana M, Kosasih H, Samaan G, Tjitra E, et al. Lane, Siswanto and S. Siddiqui. INA-RESPOND: A multi-centre clinical research network in Indonesia. Health Res Policy Syst 2015; 13:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DJ, Chan CT, Paxton H, Thompson K, et al. Comparative evaluation of a commercial enzyme immunoassay for the detection of human antibody to Rickettsia typhi. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 1995; 2:356–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Scola B, Rydkina L, Ndihokubwayo JB, Vene S, et al. Serological differentiation of murine typhus and epidemic typhus using cross-adsorption and Western blotting. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2000; 7:612–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie KC, Aziz MH, Kosasih H, Neal A, et al. Case report: Two confirmed cases of human Seoul virus infections in Indonesia. BMC Infect Dis 2018; 18:578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MY, Brady H, Hambling T, Sexton K, et al. Rickettsia felis infections, New Zealand. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18:167–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mane A, Kamble S, Singh MK, Ratnaparakhi M, et al. Seroprevalence of spotted fever group and typhus group rickettsiae in individuals with acute febrile illness from Gorakhpur, India. Int J Infect Dis 2019; 79:195–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris DH, Dumler JS. State of the art of diagnosis of rickettsial diseases: The use of blood specimens for diagnosis of scrub typhus, spotted fever group rickettsiosis, and murine typhus. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2016; 29:433–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reller ME, Bodinayake C, Nagahawatte A, Devasiri V, et al. Unsuspected rickettsioses among patients with acute febrile illness, Sri Lanka, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18:825–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reller ME, Chikeka I, Miles JJ, Dumler JS, et al. First identification and description of rickettsioses and Q fever as causes of acute febrile illness in Nicaragua. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016; 10:e0005185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsioutis C, Zafeiri M, Avramopoulos A, Prousali E, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics, epidemiology, and outcomes of murine typhus: A systematic review. Acta Trop 2017; 166:16–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]