The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Subcommittee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST SC) is a volunteer-led, multidisciplinary consensus body that develops and publishes standards and guidelines (among other products) for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) methods and results interpretation in the United States and internationally. The Subcommittee (SC) meets face-to-face twice yearly, and its working groups (WGs) are active throughout the year via teleconferences.

ABSTRACT

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Subcommittee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST SC) is a volunteer-led, multidisciplinary consensus body that develops and publishes standards and guidelines (among other products) for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) methods and results interpretation in the United States and internationally. The Subcommittee (SC) meets face-to-face twice yearly, and its working groups (WGs) are active throughout the year via teleconferences. All meetings are open to the public. Participants include clinical microbiologists, infectious disease (ID) pharmacists, and infectious disease physicians representing the health care professions, government, and industry. Individuals who work for a company with a primary financial dependency on drug sales cannot serve as voting members, and well-defined conflict of interest polices are in place. In addition to developing and updating susceptibility breakpoints, the SC develops and validates new testing methods, provides guidance on how results should be interpreted and applied, sets quality control ranges, and educates users through seminars, symposia, and webinars. Based on its work, the SC publishes print and electronic standards and guidelines, including an annual update, the Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (M100). This commentary will describe the background, organization, functions, and operational processes of the AST SC.

TEXT

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY OF CLSI AND THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON ANTIMICROBIAL SUSCEPTIBILITY TESTING

Originally established in 1968 as the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS), the organization renamed itself the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) in 2000 to emphasize its expanding Global Health Partnerships and its more global, as opposed to national, reach. The first antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) document, Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disc Susceptibility Tests, was published in 1975.

The CLSI Subcommittee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST SC) is a multidisciplinary, consensus body that develops and publishes guidelines and procedures for AST in the United States and internationally. It functions under the umbrella of the larger CLSI organizational structure. The hallmarks of an organization that sets laboratory standards affecting medical practice should be transparency, inclusiveness, and consensus decision-making based on established standards. Indeed, these are the principles espoused by CLSI, a volunteer-led not-for-profit organization with almost 2,000 volunteers. CLSI is a widely recognized laboratory medicine standards development organization (SDO) and is the only fully accredited SDO in the laboratory medicine field. It adheres to all principles of international standards development required by the World Trade Organization, is the Executive Secretariat for the International Organization for Standardization committee, and is the only laboratory SDO designated a World Health Organization collaborating center. CLSI has set laboratory standards for the past 50 years, producing a library of approximately 240 standards covering the major disciplines of clinical laboratory medicine. Its standards are used in more than 50 countries.

ORGANIZATION OF THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON ANTIMICROBIAL SUSCEPTIBILITY TESTING

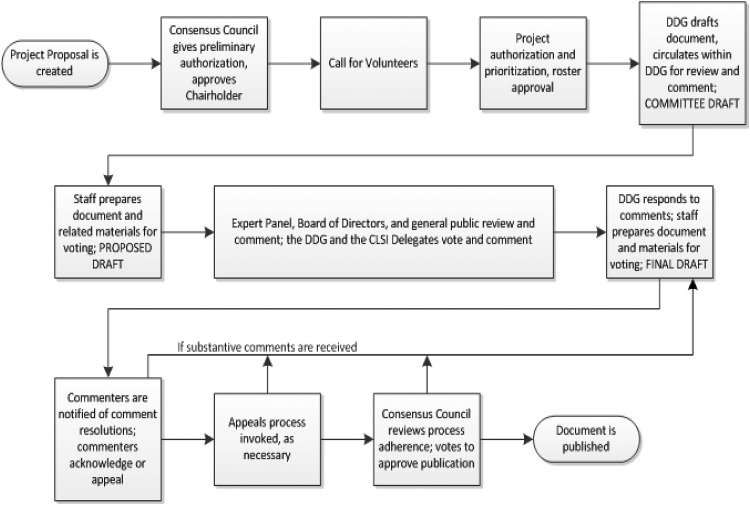

Within the subspecialty of AST, CLSI subcommittees (SC) set standards for the scope of bacterial and fungal AST performed in clinical and veterinary practice. Standards for bacteria from human infections are set by the AST SC. This subcommittee consists of volunteers who serve as chairholder, vice-chairholder, voting members, advisors, and reviewers. All volunteers, regardless of their position, can participate in working groups (WGs) of the subcommittee. The AST SC’s work is reviewed by the CLSI Microbiology Expert Panel, and all decisions are approved by the CLSI Consensus Council (see Fig. 1). CLSI salaried staff support the AST SC with project management, meeting logistics, database management, and related non-subject matter support. The AST SC is responsible for setting standard testing methods, updating interpretive criteria (often referred to as breakpoints), establishing data standards for setting breakpoints and quality control ranges, setting guidelines for reporting cumulative susceptibility data (e.g., an antibiogram), and educating health care providers on all aspects of antimicrobial susceptibility testing. The work output of the AST SC includes numerous standards, guidelines, reports, and rationale documents for AST. These include a number of documents that are widely used in clinical microbiology laboratories throughout the United States and the world. Several current examples are:

FIG 1.

High-level view of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute document development and consensus process.

-

•

Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests, 13th ed. CLSI standard M02 (1).

-

•

Performance Standards for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, 11th ed. CLSI standard M07 (2).

-

•

Methods for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Anaerobic Bacteria, 9th ed. CLSI standard M11 (3).

-

•

Methods for Antimicrobial Dilution and Disk Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria, 3rd ed. CLSI guideline M45 (4).

-

•

Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th ed. CLSI supplement M100 (5).

-

•

Development of In Vitro Susceptibility Testing Criteria and Quality Control Parameters. 5th ed. CLSI standard M23 (6).

To accomplish this work, the AST SC works throughout the year through teleconferences for working groups and holds two 3- to 4-day face-to-face meetings per year (January and June). These meetings are open to the public (find future meetings here: https://clsi.org/meetings/clsi-committees-weeks/), and meeting minutes and presentations are posted on the CLSI website (https://clsi.org/meetings/ast-file-resources/). The AST SC meetings typically draw 150 to 200 participants. All meetings are conducted using Robert’s Rules of Order, with documented voting procedures. AST SC deliberations are conducted in the presence of all meeting participants to ensure complete transparency and ample opportunities to contribute to the discussion.

Experts in clinical microbiology, infectious disease (ID) pharmacy, and infectious disease medicine work together on the AST SC, and representation from the three disciplines is carefully balanced. In addition, CLSI includes representation from health care professionals, government, and industry. The CLSI consensus process is predicated on the inclusion of the three constituencies. Eliminating any one group means the elimination of a critical knowledge base, and AST SC decisions would suffer as a result. To ensure no undue influence of financial interests on breakpoint decisions, any individual who works for a company with a primary financial dependency on drug sales is not eligible to be a voting member of the AST SC. In addition, conflict-of-interest policies are in place and require full disclosure of financial contributions from industry for all voting members and advisors. The policy of complete transparency is a second-level deterrent against undue financial influence. Because meetings are open, participants’ actions are held accountable by a room full of peers, the AST SC, and CLSI leaders.

CLSI standards are used internationally, and, to ensure a global viewpoint, members of the subcommittee include international experts. The chair of the European Union Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) serves as an advisor of the AST SC. In addition to representation from the European Union, the AST SC includes experts from other countries and regions of the world, including Australia, Japan, China, Canada, and Latin America. Official liaisons from professional societies are members of the subcommittee; these societies include the American Society for Microbiology, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the College of American Pathologists, the Association of Public Health Laboratories, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists, the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society, and the Susceptibility Testing Manufacturers Association.

FUNCTIONS OF THE AST SUBCOMMITTEE

Most clinical microbiologists, ID physicians, and ID pharmacists know that the AST SC develops and updates interpretive breakpoint criteria, but they may not be familiar with the processes and procedures by which this takes place. Also, it is less well known that the AST SC has a number of other functions, most of which come under the purview of several standing working groups (WGs).

The SC’s Breakpoint WG reviews proposed breakpoints for new antimicrobial agents (usually brought to the SC by the drug’s manufacturer), and it also reassesses breakpoints for existing antimicrobial agents and classes thereof when there is evidence of new resistance mechanisms (e.g., extended-spectrum beta-lactamases, carbapenemases) or new scientific data that mandate breakpoint changes (recent examples include pharmacokinetic and clinical data related to daptomycin versus enterococci, ceftaroline versus Staphylococcus aureus, and polymyxin B/colistin versus Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter spp.).

When investigators develop a new or innovative method for susceptibility testing or detection of resistance, the Methods Development and Standardization WG assesses the proposed methodology and determines whether the new technique can be added to the repertoire of tests described in the CLSI AST documents (1–5). Recent examples include the colistin broth disk elution and agar diffusion tests, validation of Mueller-Hinton fastidious agar for Streptococcus pneumoniae, the broth microdilution and agar disk diffusion tests for cefiderocol, and a direct susceptibility test for blood culture isolates (to be finalized in 2020). A third standing WG is the Methods Application and Interpretation WG. This WG provides guidance on how a given new or revised testing method can be applied in the clinical microbiology laboratory and how the results should be interpreted. Several notable examples of this working group’s efforts include the expanded and refined definition of “susceptible dose-dependent” and the addition of the Î breakpoint categories (see http://em100.edaptivedocs.net/Login.aspx [click to use guest access and then select M100]) published in the January 2020 update of M100; the revised and updated table that provides guidance for confirming resistant, intermediate, and nonsusceptible AST results (Appendix A in M100) (5); the Intrinsic Resistance table (Appendix B in M100) (5); and the addition of screening methods for carbapenemases (modified carbapenem inactivation method [mCIM]) and enhanced carbapenem inactivation method ([eCIM] tests) (see Tables 3B and C in M100) (5). The Quality Control (QC) WG reviews and assesses proposed QC ranges for new antimicrobials that are in development, and it reassesses and sometimes revises QC ranges for existing antimicrobials based on feedback from users. Each year, the SC publishes updated susceptibility breakpoint tables in the CLSI M100 document, and the SC’s Text and Tables WG reviews and edits all revisions prior to publication. The Text and Tables WG also oversees and reviews the other AST-related documents, such as M02, M07, and M45, for clarity and accuracy prior to their periodic revisions and publication (usually every 2 to 5 years). Lastly, the SC’s Outreach WG publishes semiannual newsletters and conducts symposia and webinars that inform the clinical microbiology community and other users about the latest updates based on the SC’s deliberations.

SETTING BREAKPOINTS—HOW DOES THE AST SC ACCOMPLISH THIS TASK?

Decisions about breakpoints are rarely black and white. Making an ethically and scientifically sound decision requires standards for data and the decision-making process. These standards are outlined in CLSI document M23, which is entitled Development of In Vitro Susceptibility Testing Criteria and Quality Control Parameters (6). These standards not only provide critical parameters for AST SC action but also a level of predictability for drug sponsors whose antibiotics are under consideration. M23 is also the basis for FDA breakpoint decision making, so data needed for FDA approval are also appropriate for CLSI submission. The following three types of data are analyzed: MIC distribution data, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, and clinical trial data. No one data source is sufficient to determine where a breakpoint should be set. Where there is scientific uncertainty, there is debate. In the case of breakpoint setting, scientific and technical debate is not a sign of ignorance or inconsistency. It is a necessary process that leads to the best answer, namely, one that makes sense in the laboratory, in clinical practice, and for patient protection. When making decisions about methods and breakpoints, there is a tension between the time needed for identifying data sources and formal deliberations about those data and the need for timely decisions that can improve patient care. CLSI continues to review its process to best deal with this tension. On the AST SC, the decision-making process was streamlined in recent years by creating small ad hoc working groups that focus on a single issue and develop a well-researched proposal before the larger group, the AST SC, is asked to make a decision. This change has significantly expedited the time to a decision. In practice, the Breakpoint WG reviews a comprehensive scientific data packet, questions the sponsor or presenter of the data, and accepts or revises the proposed breakpoints. Then, at the face-to-face meeting of the AST SC, the proposal is reviewed by the full SC, and all in attendance have the opportunity to raise questions and comment before there is an open vote. It should be noted that the meeting agenda materials are provided to all SC members, advisors, reviewers, and guests who have registered for the meeting at least 4 weeks prior to the meeting, so that there is adequate time for review of the materials before the meeting.

OTHER BREAKPOINT SETTING ORGANIZATIONS

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) has statutory authority for setting antimicrobial susceptibility breakpoints. Until recently, FDA breakpoints were published in each antimicrobial agent’s drug label. However, after passage of the 21st Century Cures Act in 2016, FDA breakpoints were moved to the Agency’s Susceptibility Test Interpretative Category (STIC) website (https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/fda-recognized-antimicrobial-susceptibility-test-interpretive-criteria). CLSI applied for and was approved as an FDA-designated standards development organization (SDO). This has resulted in most, but not all, of the CLSI breakpoints in M100 being listed in the STIC table. A discussion of the reasons why certain CLSI breakpoints are not in the FDA STIC table can be found elsewhere (7).

In addition to the FDA and CLSI AST SC, there are organizations in other parts of the world that set interpretive breakpoints, the most well known of which is EUCAST. This organization has established subsidiary committees in other countries, one of which is the United States Committee on AST (USCAST), that have the opportunity to provide additional scientific information to the EUCAST Steering Committee, which is that organization’s voting body. However, the subsidiary committees, while providing input, only have a vote in the final decision on a rotational basis. Key process differences between the CLSI AST SC and EUCAST are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Key differences between CLSI and EUCAST processes

| Function | Organization |

|

|---|---|---|

| CLSI subcommittee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing | EUCAST | |

| The primary decision-making body | Voting members of the Subcommittee, which consists of individuals, regardless of country of origin, with recognized expertise in a discipline related to antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Individuals working for a company whose revenues are directly or indirectly dependent upon the sales of antimicrobials cannot be a voting member. | The Steering Committee, which consists of representatives from selected European Union countries (national delegates) with recognized expertise in a discipline related to antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Committee members are traditionally academics. |

| Additional participants/consultants | Subcommittee advisors and reviewers, which consist of representatives from professions, government, and industry. | The General Committee, which includes members of National AST Committees (NAC). Industry is represented on the General Committee, and includes those invited to attend closed-door Steering Committee meetings where breakpoints are determined. |

| Breakpoint decisions meetings | Subcommittee discussions and voting occurs in open, transparent, and inclusive meetings (2 meetings per year). | Steering Committee members and 2–4 invited members of the General Committee make decisions behind closed doors (5 meetings per year). |

| Conflict of interest | All Subcommittee voting members and advisors submit conflict of interest statements that are publicly available on the CLSI website and are updated at the beginning of each meeting. | Steering Committee members submit a list of commercial interests to the Steering Committee chairperson. These are not publicly available, but can be made available upon request to the committee chairman. It is not clear if statements are required from General Committee members who participate in Steering Committee meetings. |

| Representation from the other organization | Formal appointment of a EUCAST advisor. | No CLSI representation. |

| Meeting minutes | Minutes and presentations from all Subcommittee meetings are available on the CLSI website (http://clsi.org). | Minutes from the Steering Committee meetings are on the EUCAST website (http://www.eucast.org/meetings/recent_meeting_minutes/). |

| Appeals process for those concerned with an undisclosed conflict of interest or that a consensus process has not been followed | Yes | No |

| Accredited standards development organization | Yes | No |

Even though breakpoint decisions are rarely clear-cut, it is noteworthy that CLSI and EUCAST breakpoints are so similar. If “susceptible” breakpoints are compared, most differences are a single MIC doubling dilution—a value that is within the technical error range of an MIC test. One reason breakpoint differences can occur is if different doses of a drug are used, and this is often cited as a theoretical reason for not attempting to harmonize breakpoints. However, differences in drug dose have rarely been the basis for differences between CLSI and EUCAST breakpoints, and they are unlikely to be a factor in the future because the same clinical trials are often used to obtain FDA and European Medicines Agency drug approval. Dosage differences are more likely to be a problem for older drugs and in parts of the world where prescribing practices may differ.

More often, differences between CLSI and EUCAST breakpoints reflect different philosophical viewpoints on how to interpret and communicate results. A good example is the use of the “intermediate” interpretive category (8). This category can be applied for multiple reasons, such as to reflect the uncertainty in the MIC result because of technical variability in MIC testing and to account for clinical efficacy if high drug exposure is possible because a higher dose of a drug is used or the drug concentrated at the site of infection. EUCAST is less likely to include an intermediate range when setting breakpoints and has eliminated technical variability as a reason for setting an intermediate range. Instead, “intermediate” is used when a higher dose of the drug (i.e., a dose higher than the dose used to set the susceptible breakpoint) is available. CLSI has maintained technical variability as a reason to use an intermediate category because MIC testing does have an inherent variability, and failure to include an intermediate range can result in susceptible isolates being falsely reported as resistant, thus removing a potentially lifesaving drug from consideration as a treatment option. In contrast, CLSI has recommended using “susceptible dose-dependent” instead of “intermediate” in some cases where multiple drug dose options are frequently used and both clinical and pharmacokinetic data point to susceptibility at higher MICs if maximum dosing is used. As a practical matter, a “susceptible dose-dependent” result from CLSI and an “intermediate” result from EUCAST communicate very similar information to the clinician. Communicating susceptibility results is a challenging problem with no single solution, but it clearly calls for international dialogue and, if possible, alignment.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing methodological differences exist between CLSI and EUCAST. Specifically, EUCAST recommends the use of some disks with different concentrations than those recommended by CLSI. In a recent assessment by CLSI, the EUCAST disks did not result in significant differences in category (e.g., susceptible versus resistant) assignment (summary minutes of the January 2016 AST Subcommittee are available at https://clsi.org/meetings/ast-file-resources/). As a result, CLSI decided not to convert to the EUCAST disks because the studies needed to meet M23 data requirements would require a significant financial and scientific investment with little to no effect on patient care. Both groups informally agreed to harmonize disk drug content moving forward, and the two organizations have established a joint WG to achieve this goal. Recommendations for media used to test fastidious bacteria also differ. In most cases it is expected that the different medium types are similar enough that breakpoint recommendations do not differ (9). Again, the organizations should agree to harmonize methodology moving forward and identify a process for ensuring that this occurs.

Is complete harmonization necessary? Harmonization would mean less confusion for laboratorians and infectious diseases clinicians and would significantly facilitate the implementation of new drugs and new breakpoints on commercial tests systems by making these changes simpler and less expensive. Harmonization would also simplify global surveillance efforts that rely upon data generated as part of routine health care practices. The argument against harmonization is the tremendous amount of work required to reassess breakpoints of older drugs where breakpoint differences are often minor (e.g., within the technical variability of the test) and there is no clinical indication that a breakpoint change is needed. To ensure efficient use of resources, priorities for harmonization should be identified.

A big challenge to harmonization is identifying an improved process for working together. Both CLSI and EUCAST intend to stay in the business of revising breakpoints and, optimally, working together would result in synergizing efforts so that each organization can work more efficiently because of the other’s efforts. In such an environment, these two organizations would spend more energy trying to find ways to work together rather than how to set themselves apart. For more than a decade, CLSI has appointed the current Chairperson of EUCAST as an advisor on the AST SC. However, to date, EUCAST has not reciprocated. Both groups are currently engaged in a Transatlantic Task for Antimicrobial Resistance (TATFAR) working group on harmonization and have identified first priorities for harmonization. CLSI will continue to work toward increased harmonization internationally, recognizing that scientific and philosophical disagreements may limit this ideal goal.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jean B. Patel for her valued contributions to the manuscript.

M.P.W. and J.S.L. are the chair and vice chair, respectively, of the CLSI Subcommittee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of the journal or of ASM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2018. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 13th ed CLSI standard M02 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2018. Performance standards for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 11th ed CLSI standard M07 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2018. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria, 9th ed CLSI standard M11 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2016. Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk susceptibility testing of infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria, 3rd ed CLSI guideline M45 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2020. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 30th ed CLSI supplement M100 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2018. Development of in vitro susceptibility testing criteria and quality control parameters, 5th ed CLSI standard M23 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humphries RM, Abbott AN, Hindler JA. 2019. Understanding and addressing CLSI breakpoint revisions: a primer for clinical laboratories. J Clin Microbiol 57:e00203-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00203-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahlmeter G, Giske CG, Kirn TJ, Sharp SE. 2019. Point-counterpoint: differences between the European Union Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for reporting antimicrobial susceptibility results. J Clin Microbiol 57:e01129-19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01129-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs MR, Bajaksouzian S, Windau A, Applebaum PC, Liu G, Felmingham D, Dencer C, Koeth L, Singer M, Good CE. 2002. Effects of various test media on the activities of 21 antimicrobial agents against Haemophilus influenzae. J Clin Microbiol 40:3269–3276. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3269-3276.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]