Abstract

Background:

Pain is a common and often debilitating symptom in persons with multiple sclerosis (MS). Besides interfering with daily functioning, pain in MS is associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety. Although cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for pain has been found to be an effective treatment in other populations, there has been a dearth of research in persons with MS.

Methods:

Persons with MS with at least moderate pain severity (N = 20) were randomly assigned to one of two groups: CBT plus standard care or MS-related education plus standard care, each of which met for 12 sessions. Changes in pain severity, pain interference, and depressive symptom severity from baseline to 15-week follow-up were assessed using a 2×2 factorial design. Participants also rated their satisfaction with their treatment and accomplishment of personally meaningful behavioral goals.

Results:

Both treatment groups rated their treatment satisfaction as very high and their behavioral goals as largely met, although only the CBT plus standard care group's mean goal accomplishment ratings represented significant improvement. Although there were no significant differences between groups after treatment on the three primary outcomes, there was an overall improvement over time for pain severity, pain interference, and depressive symptom severity.

Conclusions:

Cognitive behavioral therapy or education-based programs may be helpful adjunctive treatments for persons with MS experiencing pain.

Keywords: Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), Multiple sclerosis (MS), Pain, Psychological interventions, Psychosocial issues, Quality of life (QOL)

In persons with multiple sclerosis (MS), pain is a common and often severe symptom.1,2 Pain may be associated with central nervous system damage, inflammation, treatment adverse effects, or an unrelated disease process (eg, arthritis).3 More than 88% of people with MS experience pain in more than one bodily area, with the average being more than six distinct pain locations.4 Pain related to MS can be acute, although it often becomes chronic, negatively affecting physical and emotional functioning.3,5,6 In a longitudinal study of chronic pain in persons with MS, a significant deterioration in quality of life was noted at 10-year follow-up.7 Although MS alone can result in functional difficulties, the presence of pain can contribute to further impairment, such as interference with employment and engagement in recreational activities.5,8 Psychological well-being can also be influenced, as persons with MS with greater pain severity tend to endorse higher levels of depressive symptom severity and anxiety,9 with both of the latter conditions having a prevalence rate of more than 20% in persons with MS.10

Despite the prevalence and functional implications of MS-related pain, adequate treatment and management remain an ongoing issue. Medications are typically the most common treatment, ranging from over-the-counter drugs to prescription opioids.3,8 However, medications have limitations, including decreased effectiveness over time and increasing complexity from polypharmacy.8 In addition, long-term and high-dose opioid therapy carries several safety risks, including addiction.11 Another option is psychotherapeutic interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which target factors that may be perpetuating a person's pain experience.6 Previously, CBT has been used with success in persons with MS for fatigue12 and depression.13 Although CBT has been shown to be an effective treatment in the general chronic pain population,14 it is still an underused treatment in MS. In a recent survey of MS providers, only 26% indicated that they refer patients endorsing pain to a clinical health psychologist.15 Part of the reason for low referral rates may be the limited research. Psychotherapy for pain in MS has been studied as part of an interdisciplinary treatment program, and certain strategies, such as cognitive restructuring and self-hypnosis, have been explored with beneficial results.16,17 However, to our knowledge, to date there has not been a randomized clinical trial of CBT for MS-related pain.

This study aimed to examine the benefits of CBT for MS-related pain compared with a contact-matched educational control group. It was hypothesized that persons with MS in the CBT group, relative to those receiving MS-related education (ED), would demonstrate significant improvements in pain severity, with secondary improvements in pain interference and depressive symptom severity. In addition, treatment satisfaction and accomplishment of personalized and meaningful behavioral goals were examined.

Methods

Participants

The criteria for inclusion were a confirmed diagnosis of MS with at least 3 months of MS-related pain (eg, neuropathic pain, pain related to muscle spasms, neuralgias) of at least moderate intensity, defined as a score of 4 or greater on the 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) Numeric Rating Scale (NRS).18 There was at least one study neurologist at each study site with specific expertise in MS management who reviewed potential participants' electronic health records (EHRs) to confirm that 1) reported pain was directly related (eg, pain associated with optic neuritis) or indirectly related (eg, pain due to muscle contractions) to MS19; 2) documentation of “optimal pharmacologic management” of MS-related pain was present; and 3) appropriate pharmaceutical interventions were currently being used. Optimized pharmacologic management of MS-related pain was based on the judgment of a study neurologist and review of available EHRs for use of analgesic medications for musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain, including nonsteroids, topicals, opioids, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants and evidence of benefit and avoidance of adverse effects, harms, and misuse. The third aforementioned criterion was applied because of the expectation that psychological or educational interventions would most often be used in the context of optimized pharmacologic management of pain. Persons with life-threatening or acute physical illnesses (eg, cancer, end-stage renal disease), current alcohol or substance abuse or dependence (defined as active use within the past 3 months), current psychosis, suicidal or homicidal ideation as noted in medical progress notes or inpatient psychiatric hospitalization within the past 3 months, or pending surgical or interventional pain management procedures were excluded. Persons with MS with physical disabilities (eg, severe dysarthria) or profound cognitive impairments that would have impeded successful participation in the treatment sessions were also excluded. If persons had two or more documented exacerbations (ie, an event attributed to new disease activity by their treating neurologists and causing a clinically significant worsening of existing symptoms or development of new symptoms) during the past year or experienced an exacerbation within 24 hours of enrollment, they were excluded until they completed 1 month of appropriate treatment or were 3 months postexacerbation.

Participants were recruited from the greater Yale–New Haven community (New Haven, CT), VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) (West Haven, CT), VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) (Boston, MA), and Griffin Hospital (Derby, CT), as well as through the National MS Society and the Connecticut MS Society. Potential participants identified via the VACHS and Yale MS Center were sent opt-in letters describing the study and eligibility criteria and inviting their participation.

A total of 251 potentially eligible patients were identified via these recruitment methods (Figure S1 (166.9KB, pdf) , published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org). After EHR review by the study psychologist and neurologist (described later herein), 186 persons were found not to be eligible. An additional 42 persons were unable to be contacted or had travel difficulties, and 3 were not interested in the study. The remaining 20 participants completed the baseline assessments and were randomized using SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC), random allocation codes in equal numbers between the two conditions. All the participants continued their usual or standard care (SC) for MS, pain, and other comorbid conditions.

Procedures

Potential participants were screened for eligibility by both a study psychologist and neurologist by a review of available EHRs. Eligible participants were scheduled for an in-person session with a study research assistant during which eligibility was confirmed and signature informed consent was obtained. Sociodemographic, pain-descriptive (eg, pain locations, pain duration), and MS-descriptive (eg, MS subtype and duration) data were collected, and pain-relevant self-report questionnaires described later herein were completed. Given the literature on the effects of MS on cognitive abilities,20 participants met with a study clinical neuropsychologist or a supervised psychology technician for a brief neuropsychological examination, during which time they completed the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC).

Participants who completed all the baseline evaluations were randomly assigned to receive either CBT plus standard care (CBT/SC) or ED plus standard care (ED/SC). After completion of treatment, participants completed immediate posttreatment evaluations with a study research assistant (R.C.) who was not blinded to intervention condition. Data were collected via the mail or during an in-person visit with the research assistant. Although there was a baseline appointment and 12 treatment sessions, there was a window of 15 weeks from collection of the baseline data to collection of the immediate posttreatment data to permit flexibility in scheduling sessions and to accommodate significant symptom exacerbations and associated delays in treatment delivery.

Participants were not compensated for their participation in the study sessions; however, they were eligible for compensation for their participation in the baseline evaluation and each of the four follow-up evaluations, for a possible total of $225. The procedures and protocol were approved by the VACHS, VABHS, and Yale University School of Medicine institutional review boards.

Study Treatments

Treatments (CBT/SC and ED/SC) involved 12 sessions, including seven 60-minute, outpatient, individual sessions and five 30-minute individual telephone sessions. Both treatment arms were delivered by clinical health psychologists with training in care of persons with MS and delivering CBT for chronic pain. Psychologists followed treatment manuals developed for each of the two conditions. The same psychologists delivered both interventions.

CBT/SC Treatment

Psychologists followed a previously developed treatment protocol21 that was revised to be specific to MS-related pain. The protocol also incorporated motivational interviewing strategies to encourage treatment engagement and adherence to therapist recommendations for pain coping skill practice. Treatment was tailored and paced according to participant interests, previous knowledge, and learning capacity. Components of CBT treatment included 1) identification of idiosyncratic beliefs about pain and pain treatment, 2) instruction in cognitive (eg, distraction) and behavioral (eg, activity pacing) skills, and 3) consolidation of cognitive and behavioral skills through activities such as role-playing. As a method to reinforce material presented during the session, each participant collaborated with the psychologist to develop intersession behavioral goals and plans for using pain coping skill practice in the form of “homework.” This allowed psychologists to provide corrective feedback. During telephone sessions the therapists emphasized adherence to behavioral goal accomplishment, reviewed previous materials, and presented new didactic material.

ED/SC Treatment

An ED/SC control group was chosen instead of an SC-only group to control for nonspecific factors that might contribute to outcomes, such as attending treatment sessions and having personal contact with a health professional. Furthermore, education about MS-related symptoms is often encouraged as an adjunct to routine medical care.22 The National MS Society Sourcebook was used as a therapist manual and for participant handouts. Topics for the 12 sessions include information on MS etiology, diagnosis and prognosis, pain in MS, medications for symptom management, disease-modifying medications, alternative therapies, rehabilitation, exercise, lifestyle issues, alcohol use and smoking, preventive health, adapting the home and assistive devices, and caregiver support. Topics that were psychological in nature, such as the emotional aspects of MS, were not included in the sourcebook. To make the two treatment arms equivalent, time was spent with participants creating weekly behavioral goals corresponding to those developed in CBT as well as discussing the implications of the content covered in each session. The discussions were unstructured, and no specific skills were covered.

Standard Care

In both conditions, participants continued to receive routine care for their MS and MS-related symptoms, including pain management, from their current health care providers (not research staff). Standard of care usually consisted of being seen in an outpatient specialty clinic by a neurologist who collaborated with other clinicians to care for patients in all stages of the disease. No efforts were made to influence the management of MS, MS-related pain, or other health concerns. Medication use, including changes in medication, self-reported adherence, and extra doses of pain medications, however, were monitored by participant completion of a weekly questionnaire. Eight participants in the CBT/SC group and seven in the ED/SC group had changes in their medications.

Measures

Outcomes

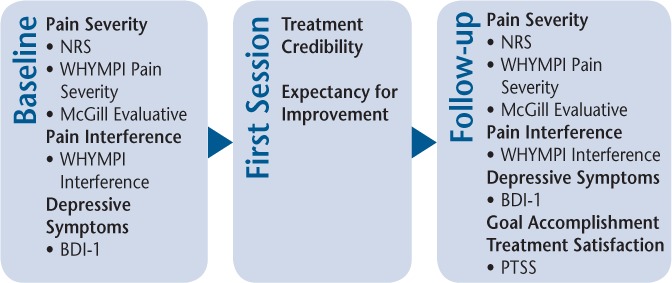

Outcome measures (Figure 1) were selected to represent core outcome domains for clinical trials for chronic pain as recommended by the Initiative on Methods, Measures, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT).23 Three measures were used to assess participants' pain severity: the NRS,24 the West Haven–Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI),25 and the McGill Pain Questionnaire.26 To minimize type I errors due to multiple comparisons, a Pain Severity Composite Score was created using the NRS, the WHYMPI Pain Severity subscale, and the McGill Evaluative subscale, which had moderately high internal consistency (α = 0.77). Participants' perceived level of pain interference with social role functioning (ie, day-to-day activities, work, recreational and other social activities, family-related activities, and household chores) was also measured using the WHYMPI Interference subscale. Depressive symptom severity was measured using the Beck Depression Inventory.27

Figure 1.

Outcome measures at baseline through follow-up for both groups

BDI-1, Beck Depression Inventory; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; PTSS, Pain Treatment Satisfaction Scale; WHYMPI, West Haven–Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory.

Physical and Cognitive Measures

Level of disability was assessed using the MSFC, a composite score that includes measures of cognitive processing speed (Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test), fine motor functioning (Nine-Hole Peg Test), and ambulation (25-foot walk).28 The MSFC was calculated using the equation and National MS Society normative data that were provided in the manual.29

Treatment Goals, Credibility, and Satisfaction

Before receiving the interventions, all the participants were asked to identify up to five S.M.A.R.T. (specific, measurable, achievable, results-focused, and time-bound) treatment goals. After treatment, they rated their level of accomplishment on a scale from −2 (100% decline) to 2 (100% improvement).30 During their first session, participants rated the credibility and expectancy for improvement for their assigned treatment.31 At week 15, participants completed the Pain Outcomes Questionnaire–Pain Treatment Satisfaction Scale, in which they rated their level of satisfaction with the overall treatment, staff warmth and skills, ease of getting appointments, and recommendation of the treatment to others on a scale from 0 (no satisfaction) to 10 (complete satisfaction). A total score was generated by averaging the sum of the five questions.32

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were approached as intention-to-treat. Missing values analysis was conducted (χ267 = 12.54, P > .99), which justified the use of the expectation maximization method to impute values for missing outcome data points. Differences between the two treatment groups' demographic and disease-related characteristics were assessed using t tests for continuous data and χ2 tests for categorical data. Changes on the outcome measures were evaluated using a 2 (CBT/SC and ED/SC) × 2 (before and after treatment) factorial design. Treatment credibility, treatment satisfaction, and behavioral goal accomplishment between the two conditions were compared using t tests.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The overall sample (Table 1) was largely composed of persons with relapsing-remitting MS (70%), with a mean ± SD age of 52.60 ± 10.95 years and 15.05 ± 2.14 years of education. There was a higher ratio of men to women (3:2), and 75% of the sample was white. Participants reported that they had been diagnosed as having MS for a mean ± SD of 13.25 ± 10.23 years and had been experiencing pain for 13.23 ± 13.00 years. The mean ± SD level of disability on the MSFC was −1.17 ± 2.28. Participants reported a mean ± SD of 4.25 ± 1.45 pain locations, most commonly in the legs/feet (95%) and lower back (80%). Participants attended a mean ± SD of 10 ± 3.92 sessions in the CBT/SC group and 8 ± 5.42 sessions in the ED/SC group. There were no differences between the two treatment groups at baseline in terms of age, gender, race/ethnicity, MS subtype, MSFC, MS duration, pain duration, or pain locations. During the study period, no adverse events or serious adverse events were reported.

Table 1.

Participants' demographic and outcome information

| Characteristic | Total (N = 20) | CBT/SC group (n = 10) | ED/SC group (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 52.60 ± 10.95 | 52.20 ± 9.61 | 53.00 ± 12.66 |

| Education, y | 15.05 ± 2.14 | 15.50 ± 2.15 | 14.60 ± 2.12 |

| Gender, F/M | 8/12 | 4/6 | 4/6 |

| Race | |||

| White | 15 | 7 | 8 |

| African American | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Mixed | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| MS type | |||

| RRMS | 14 | 8 | 6 |

| RPMS | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| PPMS | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| MS duration, y | 13.25 ± 10.23 | 12.60 ± 7.40 | 13.90 ± 12.86 |

| MSFC score | −1.17 ± 2.28 | −1.71 ± 2.27 | −1.83 ± 2.40 |

| Pain duration, y | 13.23 ± 13.00 | 11.30 ± 10.24 | 15.15 ± 15.61 |

| No. of pain locations | 4.25 ± 1.45 | 3.80 ± 1.03 | 4.70 ± 1.70 |

| Pain locations | |||

| Arms/hands | 60% | 50% | 70% |

| Legs/feet | 95% | 90% | 100% |

| Upper back | 45% | 50% | 40% |

| Lower back | 80% | 70% | 90% |

| Head/facial | 50% | 30% | 70% |

| Neck | 55% | 60% | 50% |

| Other | 40% | 30% | 50% |

| Baseline pain severity score | 4.19 ± 1.21 | 4.11 ± 1.38 | 4.28 ± 1.08 |

| Posttreatment pain severity score | 3.67 ± 1.03 | 3.78 ± 0.94 | 3.57 ± 1.40 |

| Baseline pain interference score | 3.77 ± 1.42 | 2.90 ± 1.31 | 4.64 ± 0.93 |

| Posttreatment pain interference score | 3.16 ± 1.57 | 2.36 ± 1.33 | 3.96 ± 1.42 |

| Baseline depression score | 13.38 ± 7.04 | 10.37 ± 5.72 | 16.32 ± 7.23 |

| Posttreatment depression score | 9.61 ± 6.89 | 8.36 ± 5.56 | 10.85 ± 8.12 |

| Treatment credibility score | 40.41 ± 7.09 | 42.78 ± 7.81 | 37.75 ± 5.47 |

| PTSS total score | 9.59 ± 0.63 | 9.56 ± 0.71 | 9.63 ± 0.57 |

Note: Values are given as mean ± SD or number, unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CBT/SC, cognitive behavioral therapy plus standard care; ED/SC, MS-related education plus standard care; MS, multiple sclerosis; MSFC, Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite; PPMS, primary progressive MS; PTSS, Pain Treatment Satisfaction Scale; RPMS, relapsing progressive MS; RRMS, relapsing-remitting MS.

Pain Severity and Interference

At baseline there was no difference between the CBT/SC and ED/SC groups in terms of the composite pain severity score (t18 = −0.30, P = .767). There was a significant effect for time (F1,18 = 4.61, P = .046), indicating a beneficial treatment effect on pain severity, but the time × treatment interaction was not statistically significant (F1,18 = 0.61, P = .444).

The CBT/SC group reported lower pain interference than the ED/SC group at baseline, which was a significant difference (t18 = −3.42, P = .003). As with pain severity, there was a significant effect from time (F1,18 = 4.63, P = .045), with an overall decrease in pain interference at 15-week follow-up. Time × treatment effects were not statistically significant (F1,18 = 0.06, P = .813).

Depressive Symptoms

Participants in the CBT/SC condition, relative to those in the ED/SC condition, reported lower depressive symptom severity in the CBT/SC group at baseline compared with the ED/SC group, but this difference did not reach significance (t18 = −2.04, P = .056). Similar to both pain outcomes, a statistically significant effect of time was observed (F1,18 = 5.79, P = .027), indicating a significant decrease in depressive symptom severity as a function of treatment, and the time × treatment effect was not statistically significant (F1,18 = 1.24, P = .280).

Treatment Credibility and Satisfaction

The CBT/SC group's ratings of their treatment credibility and expectancy for improvement was higher than those of the ED/SC group, although the difference did not reach significance (t15 = 1.52, P = .150). Both groups' treatment total satisfaction ratings were high. The difference between the two groups was not significantly different (t16 = −0.04, P = .967).

Goal Accomplishment

The mean ± SD behavioral goal accomplishment rating for the CBT/SC group was significantly different from zero (1.27 ± 0.55 [95% CI, 0.87 to 1.66]), indicating significant improvement. In contrast, the ED/SC group's mean ± SD goal accomplishment rating was not significantly different from zero (0.65 ± 1.20 [95% CI, −0.35 to 1.65]). The mean goal accomplishment ratings were not significantly different between the two groups (t9,37 = 1.36, P = .207).

Discussion

More than half of all people with MS endorse having pain, which can affect their daily functioning, emotional well-being, and quality of life.2,5–9 Although pharmacologic treatments are most often used,3,8 they do not target the cognitive, behavioral, and psychosocial factors that may be contributing to the pain experience.6 The present study investigated whether CBT, an effective intervention in the general chronic pain population,14 could be beneficial for MS-related pain. MS-related education was used as a comparison condition in this randomized controlled trial.

Overall, both the CBT/SC and ED/SC groups were observed to improve as a function of treatment on important outcome measures, namely pain severity, pain interference, and depressive symptom severity. Contrary to the stated hypothesis, there was no evidence that participants in the CBT/SC condition accrued greater benefit in terms of any of these outcomes relative to participants in the ED/SC condition. Similarly, participants in both treatment conditions also endorsed very high levels of treatment satisfaction, and no difference between the two conditions in these ratings was observed. Finally, both groups largely reported that they completed their treatment goals. Although no significant differences in goal accomplishment were noted between participants in the two conditions, only the CBT/SC group's ratings were significantly different from zero, suggesting clinically meaningful achievement of personally meaningful goals. As this is seemingly the first clinical trial of CBT for the treatment of pain among persons with MS, these findings are encouraging, albeit preliminary. At the same time, the observed benefits of a structured and intensive educational condition and the lack of significant incremental benefits of CBT relative to the education condition suggest that either approach may be beneficial for the management of pain in persons with MS.

Because the measure of pain severity was a composite of three standardized measures of this construct, there are no published guidelines for interpreting clinically significant change. For the measure of pain interference, the observed mean reduction across both interventions (0.61) was consistent with IMMPACT recommendations for determining a clinically significant change.33 Similarly, for the measure of depressive symptom severity, Vlaeyen and colleagues34 recommended that a mean reduction of 4 points and a final score of 10 or less could be considered evidence of clinically meaningful improvement. In the present study, the observed reduction of 3.77 was slightly below the recommendations for a clinically significant improvement, and the mean score after treatment was less than 10. Together, the observed data could be interpreted as being consistent with clinically meaningful improvements in at least pain interference, and possibly depressive symptoms and pain severity. As such, physicians and other providers may consider referring persons with MS experiencing pain to one of these interventions as part of a comprehensive pain management strategy.

The findings of this study should be interpreted with caution. Of particular relevance is the fact that the study is substantially underpowered to detect effects of the two treatment conditions and especially between-group effects. Despite extensive recruitment efforts, a relatively small number of persons with MS were referred or otherwise conveyed interest in participating in the study, and, of these, less than 10% of persons who were screened met the eligibility criteria and provided consent to participate. Among a range of factors apparently contributing to the low rates of engagement observed, the inability of the study neurologist to confirm the diagnosis of MS was particularly noted. Failure to meet a minimal threshold for pain severity, sometimes due to apparent successful medication management, was also a significant limiting factor. Ultimately, these persons with MS were most often white men, well-educated, and relatively high functioning. These observations may suggest a recruitment bias that undermines generalization to women, minorities, less well-educated individuals, and more impaired persons with MS.

Although demographic characteristics and pain severity were controlled during the randomization process, the CBT group had lower levels of pain interference at baseline, which may have influenced their response to the treatment. Previous research has suggested that higher levels of pain interference at baseline in clinical trials of CBT for chronic pain may be associated with poorer rates of treatment completion.35

For some potentially eligible and interested persons with MS, barriers to accessing care, such as difficulties with mobility and transportation, were salient factors that may have precluded weekly on-site attendance. Future research may explore whether other intervention delivery methods may increase attendance levels, such as telehealth, which has shown promising results in physical rehabilitation,36 medication adherence,37 and self-management38 in persons with MS. In addition, although pain can be a severe and intrusive symptom for persons with MS,1,5,8 it may not be prioritized in relation to other MS symptoms. Persons who participated in this study endorsed similar pain and MS durations, potentially suggesting that if pain is a significant portion of their MS presentation, they may be more likely to participate in MS-related pain research. As such, future studies may examine the role of pain's intrusiveness to individuals' overall experience of MS-related impairment and symptoms.

The findings suggest that persons with MS who have pain were very satisfied and largely completed their treatment goals after completion of a CBT or educational program. Given the overall improvements in aspects of pain and emotional well-being, further investigation of nonpharmacologic interventions for MS-related pain is warranted.

PRACTICE POINTS

Although pain can have psychological effects on persons with MS, there is limited research on behavioral treatments.

Persons with MS who underwent 12 weeks of a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or an MS-related educational program were very satisfied with their treatment and reported largely meeting their behavioral goals.

Participation in either treatment resulted in improvements in pain severity, pain interference, and emotional well-being, suggesting that nonpharmacologic treatment for pain may be beneficial for persons with MS.

Financial Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support

Support for this project was provided by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service (D4150R) and Health Services Research and Development Service, Center of Innovation (COIN), Pain Research, Informatics, Multimorbidities, and Education (PRIME) Center, West Haven, CT (CIN 13-047).

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Stenager E, Knudsen L, Jensen K. Acute and chronic pain syndromes in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1991;84:197–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1991.tb04937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foley PL, Vesterinen HM, Laird BJ et al. Prevalence and natural history of pain in adults with multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2013;154:632–642. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Namerow NS. Geisser BS. Primer on Multiple Sclerosis. Oxford University Press; 2011. Multiple sclerosis and pain; pp. 275–288. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehde DM, Osborne TL, Hanley MA, Jensen MP, Kraft GH. The scope and nature of pain in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2006;12:629–638. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerns RD, Kassirer M, Otis J. Pain in multiple sclerosis: a biopsychosocial perspective. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2002;39:225–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerns RD. Psychosocial aspects of pain. Int J MS Care. 2000;2:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young J, Amatya B, Galea MP, Khan F. Chronic pain in multiple sclerosis: a 10-year longitudinal study. Scand J Pain. 2017;16:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadjimichael O, Kerns RD, Rizzo MA, Cutter G, Vollmer T. Persistent pain and uncomfortable sensations in persons with multiple sclerosis. Pain. 2007;127:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalia LV, OConnor PW. Severity of chronic pain and its relationship to quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:322–327. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1168oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marrie RA, Reingold S, Cohen J et al. The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2015;21:305–317. doi: 10.1177/1352458514564487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:276–286. doi: 10.7326/M14-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Kessel K, Moss-Morris R, Willoughby E, Chalder T, Johnson MH, Robinson E. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy for multiple sclerosis fatigue. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:205–213. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181643065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohr DC, Likosky W, Bertagnolli A et al. Telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:356–361. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999;80:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gromisch ES, Schairer LC, Pasternak E, Kim SH, Foley FW. Assessment and treatment of psychiatric distress, sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbances, and pain in multiple sclerosis: a survey of members of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. Int J MS Care. 2016;18:291–297. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2016-007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan A, Scheman J, LoPresti A, Prayor-Patterson H. Interdisciplinary treatment of patients with multiple sclerosis and chronic pain. Int J MS Care. 2012;14:216–220. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073-14.4.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Gertz KJ et al. Effects of self-hypnosis training and cognitive restructuring on daily pain intensity and catastrophizing in individuals with multiple sclerosis and chronic pain. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2010;59:45–63. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2011.522892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Fisher LD. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain. 1999;83:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudy TE, Turk DC, Brena SF, Stieg RL, Brody MC. Quantification of biomedical findings of chronic pain patients: development of an index of pathology. Pain. 1990;42:167–182. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91160-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1139–1151. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70259-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otis J. Managing Chronic Pain: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach. Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newsome SD, Aliotta PJ, Bainbridge J et al. A framework of care in multiple sclerosis, part 2: symptomatic care and beyond. Int J MS Care. 2017;19:42–56. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2016-062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turk DC, Rudy TE, Sorkin BA. Neglected topics in chronic pain treatment outcome studies: determination of success. Pain. 1993;53:3–16. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90049-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerns RD, Turk DC, Rudy TE. The West Haven-Yale multidimensional pain inventory (WHYMPI) Pain. 1985;23:345–56. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melzack R. Melzack R. Pain Measurement and Assessment. Raven Press; 1983. The McGill Pain Questionnaire; pp. 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer J, Rudick R, Cutter G, Reingold S, National MS Society Clinical Outcomes Assessment Task Force The Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite Measure (MSFC): an integrated approach to MS clinical outcome assessment. Mult Scler. 1999;5:244–250. doi: 10.1177/135245859900500409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer JS, Jak AJ, Kniker JE, Rudick R, Cutter G. Administration and Scoring Manual for the MS Functional Composite Measure (MSFC) Demos; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kerns RD, Turk DC, Holzman AD, Rudy TE. Comparison of cognitive-behavioral and behavioral approaches to the outpatient treatment of chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 1985;1:195–203. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark ME, Gironda RJ, Young RW. Development and validation of the Pain Outcomes Questionnaire-VA. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40:381–395. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2003.09.0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vlaeyen JW, Haazen IW, Schuerman JA, Kole-Snijders AM, van Eek H. Behavioural rehabilitation of chronic low back pain: comparison of an operant treatment, an operant-cognitive treatment and an operant-respondent treatment. Br J Clin Psychol. 1995;34:95–118. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1995.tb01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heapy A, Otis J, Marcus KS et al. Intersession coping skill practice mediates the relationship between readiness for self-management treatment and goal accomplishment. Pain. 2005;118:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finkelstein J, Lapshin O, Castro H, Cha E, Provance PG. Home-based physical telerehabilitation in patients with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45:1361–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner AP, Sloan AP, Kivlahan DR, Haselkorn JK. Telephone counseling and home telehealth monitoring to improve medication adherence: results of a pilot trial among individuals with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2014;59:136–146. doi: 10.1037/a0036322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ehde DM, Elzea JL, Verrall AM, Gibbons LE, Smith AE, Amtmann D. Efficacy of a telephone-delivered self-management intervention for persons with multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial with a one-year follow-up. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1945–1958.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]