This study shows that the regulatory innate lymphoid cell (ILCreg), a recently described IL-10–producing innate lymphocyte, is not present in mice bred in four different facilities. Instead, group 2 ILCs provide an inducible source of IL-10 in the intestine.

Abstract

Although innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) functionally analogous to T helper type 1 (Th1), Th2, and Th17 cells are well characterized, an ILC subset strictly equivalent to IL-10–secreting regulatory T cells has only recently been proposed. Here, we report the absence of an intestinal regulatory ILC population distinct from group 1 ILCs (ILC1s), ILC2s, and ILC3s in (1) mice bred in our animal facility; (2) mice from The Jackson Laboratory, Taconic Biosciences, and Charles River Laboratories; and (3) mice subjected to intestinal inflammation. Instead, a low percentage of intestinal ILC2s produced IL-10 at steady state. A screen for putative IL-10 elicitors revealed that IL-2, IL-4, IL-27, IL-10, and neuromedin U (NMU) increased IL-10 production in activated intestinal ILC2s, while TL1A suppressed IL-10 production. Secreted IL-10 further induced IL-10 production in ILC2s through a positive feedback loop. In summary, ILC2s provide an inducible source of IL-10 in the gastrointestinal tract, whereas ILCregs are not a generalizable immune cell population in mice.

Introduction

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are a family of cytokine-activated, cytokine-secreting lymphocytes that reside in barrier tissues and participate in maintaining mucosal homeostasis and host defense against infection (Branzk et al., 2018; Sonnenberg and Artis, 2015). ILCs functionally analogous to polarized CD4+ T cell subsets are well characterized: group 1 ILC (ILC1) produce IFNγ and are analogous to T helper (Th) type 1 (Th1) cells; ILC2 produce IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 and are analogous to Th2 cells; and ILC3 produce IL-17 and IL-22 and are analogous to Th17 cells (Eberl et al., 2015; Vivier et al., 2018). ILCs acquire effector functions during their development and are thus able to rapidly secrete cytokines upon encountering activating signals.

CD4+ regulatory T cells (T reg cells) are a major source of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. IL-10 is required for maintaining intestinal homeostasis, as demonstrated by Il10-deficient mice, which on susceptible genetic backgrounds develop spontaneous colitis due to dysregulated activation of CX3CR1+ macrophages and Th1 cells (Berg et al., 1996; Davidson et al., 1996; Kühn et al., 1993). The functional parallels between polarized CD4+ T cells and ILC subsets have raised the question of whether ILC analogous to T reg cells are present in the gut. Recently, a novel IL-10–secreting ILC fitting this role, termed the regulatory ILC (ILCreg), was reported in the intestine (Wang et al., 2017). ILCregs were a distinct population from ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC3s and were functionally analogous to T reg cells based on their ability to suppress cytokine production in intestinal ILC1s and ILC3s via IL-10. ILCregs were most abundant in small intestine lamina propria, and these cells expanded in number during multiple models of intestinal inflammation. However, evidence of other IL-10–producing ILCs in barrier tissues has emerged with reports that activated lung ILC2s can produce IL-10 after chronic treatment with papain (Miyamoto et al., 2019; Seehus et al., 2017). These findings raise the possibility that ILC2s may be major IL-10–producing ILCs in the gut, particularly in the context of type 2 immune activation induced by protozoa and parasitic helminths. The relative contributions of IL-10 by ILCregs and ILC2s in the gastrointestinal tract remain undefined.

Here, we used a cytokine reporter mouse to identify innate lymphocytes that produce IL-10 in the intestine. We show that mice bred in our facility lacked ILCregs based on IL-10 reporter expression. Confirming this finding, mice bred in our facility or purchased from laboratory mouse vendors (The Jackson Laboratory [JAX], Taconic Biosciences, and Charles River Laboratories) showed no evidence of ILCregs based on staining for ILCs distinct from ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC3s. Additionally, ILCregs were not observed during dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)–induced colitis or Citrobacter rodentium infection, two models of intestinal inflammation. Instead, within the lineage-negative lymphocyte compartment, a small percentage of ILC2s produced IL-10. Using screens to investigate the signals that induce IL-10 production in ILC2s, we found that multiple soluble mediators elicited IL-10, while the TNF superfamily member TL1A strongly inhibited IL-10 production. These data indicate that ILCregs are not broadly observed across laboratory mice, and that instead, ILC2s provide an inducible source of IL-10 in the gastrointestinal tract.

Results and discussion

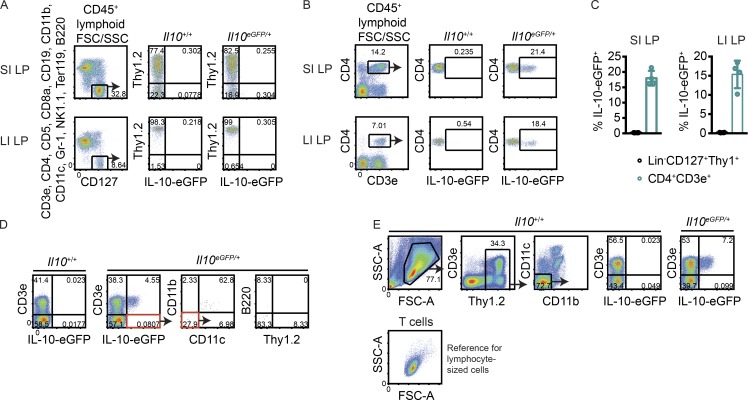

No evidence for IL-10–eGFP+ expression in Lin−CD127+Thy1+ cells from naive small and large intestine

ILCregs were previously described as lineage marker-negative (Lin)−CD127+eGFP+ cells in Il10eGFP/+ (B6.129S6-Il10tm1Flv/J, also known as IL-10–eGFP) reporter mice (Wang et al., 2017). These cells were reported to express Thy1 but lacked markers that define ILC1s (NKp46, NK1.1, and T-bet), ILC2s (KLRG1 and high amounts of GATA3), and ILC3s (RORγt). To identify innate lymphoid producers of IL-10, we obtained the same reporter mice from JAX, bred them with C57BL/6J mice purchased from JAX, and processed the intestinal lamina propria of their heterozygous progeny. CD45+Lin−CD127+Thy1+ lymphocytes lacked eGFP in the small and large intestine (Fig. 1, A and C), whereas CD4+ T cells expressed IL-10 in both tissues (Fig. 1, B and C).

Figure 1.

No evidence for IL-10–producing Lin−CD127+Thy1+ cells in naive small and large intestine. (A and B) Representative FACS plots showing IL-10–eGFP expression in small intestine (SI) and large intestine (LI) lamina propria (LP) CD45+ lymphocyte-sized Lin−CD45+CD127+ cells (A) and CD4+ T cells (B). (C) Frequencies of eGFP+ cells among lymphocyte-sized Lin−CD45+CD127+Thy1+ cells and CD4+ T cells in small intestine and large intestine lamina propria in multiple mice (n = 4). (D) Modified gating scheme to account for all cell lineages that expressed eGFP within the lymphocyte-based FSC/SSC gate. (E) Modified gating scheme to include cells with an expanded FSC/SSC profile. Below, the FSC/SSC profile of CD3e+ cells is shown as a reference for where lymphocytes lie in the plot. Bars indicate means ± SD. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

To determine whether the lineage-negative gate excluded IL-10 producers, an alternate staining strategy was used to account for all cell lineages that expressed eGFP within the live lymphocyte-based forward scatter (FSC)/side scatter (SSC) gate. The majority of eGFP+ cells were T cells, with non-T cell GFP+ events either being CD11b+CD11c+ or CD11b−CD11c−B220− cells that lacked Thy1 (Fig. 1 D). A separate gating scheme with an expanded FSC/SSC gate that included larger and more granular cells, such as monocytes, also did not reveal eGFP+ ILCregs (Fig. 1 E). Thus, naive mice bred in our facility lacked an intestinal cell population that corresponded to ILCregs based on IL-10 reporter expression.

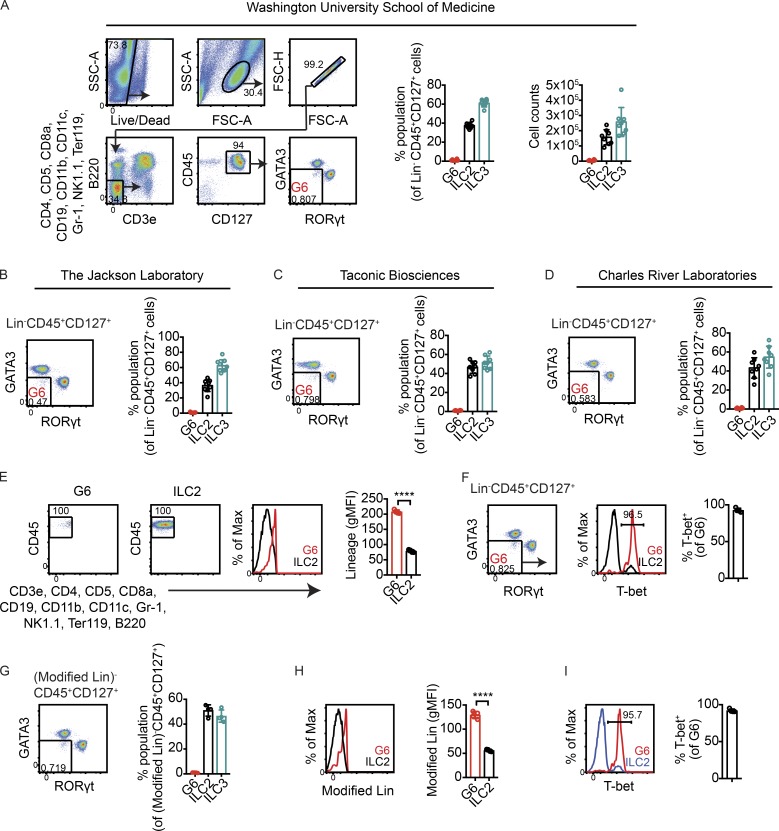

No evidence for ILCregs based on staining for ILCs distinct from ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC3s in small intestines of mice bred at Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM), mice purchased from commercial vendors, and mice subjected to intestinal inflammation

Differences in microbiota have been shown to impact cytokine production in T cells (Brown et al., 2019). To address the possibility that ILCregs might not produce IL-10 in our animal facility at WUSM due to environmental conditions, an antibody staining strategy was used in an attempt to identify these cells without relying on cytokine reporter expression. Small intestine lamina propria single-cell suspensions were stained with antibodies for cell surface markers and transcription factors to identify a population of ILCs separate from ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC3s. With ILC1 and natural killer (NK) cell markers excluded by lineage staining, >99% of Lin−CD45+CD127+ small intestine lymphocytes were either GATA3hi ILC2s or RORγt+ ILC3s; on average, <1% of Lin−CD45+CD127+ small intestine lymphocytes (which excluded ILC1s and NK cells) lacked ILC2 and ILC3 markers (Fig. 2 A). Thus, regardless of IL-10–eGFP expression, mice bred in our facility lacked a population that corresponded to ILCregs, which was previously reported to be ∼13% of lineage-negative small intestine lamina propria cells based on function marking alone (Wang et al., 2017).

Figure 2.

No evidence for lineage-negative ILCs distinct from ILC2s and ILC3s in small intestines of mice bred at WUSM and mice purchased from commercial vendors. (A) Left: Gating strategy to identify lineage-negative events that lacked markers for ILC2s and ILC3s. Right: Frequencies and total numbers of Lin−CD45+CD127+ cells that were GATA3hi (ILC2s) or RORγt+ (ILC3s) or that lacked markers for both ILC2s and ILC3s (G6) in small intestine lamina propria of WT mice bred at WUSM (n = 8). (B–D) Frequencies of Lin−CD45+CD127+ cells that lacked ILC2 and ILC3 markers in mice purchased from JAX (n = 8; B), Taconic Biosciences (n = 8; C), and Charles River Laboratories (n = 8; D). (E) Representative flow cytometry plots showing backgated G6. ILC2s are shown as a reference for lineage-negative cells. Right, quantified gMFI of lineage staining in G6 and ILC2s (n = 4). (F) T-bet staining in G6 (n = 4). (G) Frequencies of G6, ILC2s, and ILC3s using a modified lineage staining panel (Modified Lin) in which anti-F4/80 antibodies were added while anti-B220 antibodies were excluded (n = 4). (H) gMFI of Modified Lin staining in G6 and ILC2s (n = 4). (I) Frequencies of T-bet+ cells within G6 obtained using Modified Lin staining (n = 4). Bars indicate means ± SD. Data were pooled from two independent experiments (A–D) or are representative of two independent experiments (D–I). ****, P < 0.0001.

To test whether these results were unique to mice bred in our facility, WT mice were obtained from the mouse vendors JAX (C57BL/6J), Taconic Biosciences (C57BL/6N), and Charles River Laboratories (C57BL/6N). Microbiota associated with these facilities were previously shown to differentially impact abundances of intestinal Th17 cells and CD4+CD8αα+ intraepithelial lymphocytes (Cervantes-Barragan et al., 2017; Ivanov et al., 2008). Similar to what was observed in mice bred at WUSM, ILC2s and ILC3s accounted for >99% of all Lin−CD45+CD127+ small intestinal lamina propria cells in C57BL/6 mice purchased from each of the three vendor facilities; in each case, <1% of Lin−CD45+CD127+ flow cytometry events were neither ILC2s nor ILC3s (Fig. 2, B–D). Thus, in mice obtained from multiple animal facilities, we found no evidence for ILCs distinct from ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC3s in frequencies consistent with what was previously reported for ILCregs. Additionally, the absence of this population was not due to genetic differences between C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N substrains.

Next we determined whether the few Lin−CD45+CD127+ flow cytometry events that lacked ILC2 and ILC3 markers (events within the flow cytometry gate denoted gate 6 [G6]) had markers consistent with ILCregs. Backgating revealed that G6 events primarily existed on the edge of the gate that interfaced with lineage-positive cells, suggesting that the majority of these events expressed lineage markers (Fig. 2 E). Indeed, events in G6 stained positively for the transcription factor T-bet (Fig. 2 F). Similar results were obtained with a modified lineage cocktail in which anti-F4/80 antibodies were added but anti-B220 antibodies were excluded (Fig. 2, G–I), used to replicate the lineage markers previously used to identify ILCregs (Wang et al., 2017). These data show that G6 events were T-bet–expressing, lineage-positive cells, inconsistent with the reported phenotype of ILCregs.

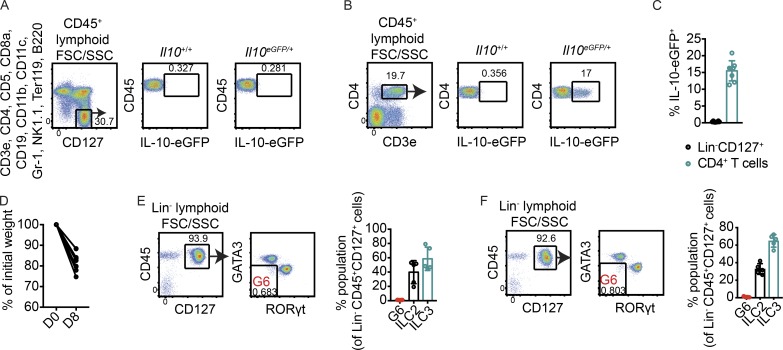

Intestinal inflammation resulting from DSS-induced injury and infection with C. rodentium was previously reported to increase frequencies of ILCregs in the small intestine (Wang et al., 2017). To test whether intestinal inflammation would give rise to a population of IL-10–producing ILCs in our laboratory, mice were treated with 3% DSS in drinking water. On day 8, eGFP was absent in Lin−CD45+CD127+ cells in small intestine lamina propria but was expressed by CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3, A–C). Disease was confirmed at this time point by body weight loss (Fig. 3 D). Mirroring observations in naive mice, >99% of Lin−CD45+CD127+ cells in small intestine lamina propria of DSS-treated mice were ILC2s or ILC3s; there was no increase in an ILC population distinct from ILC1s, ILC2s, or ILC3s (Fig. 3 E). Similarly, there was no increase in an innate lymphoid population lacking ILC1, ILC2, and ILC3 markers on day 8 of infection with the enteric pathogenic bacterium C. rodentium (Fig. 3 F). Taken together, these data show that ILCregs are not generalizable across mice.

Figure 3.

No evidence for ILCreg induction during intestinal inflammation. (A and B) Representative flow cytometry plots showing IL-10–eGFP expression in Lin−CD45+CD127+ cells (A) and CD4+ T cells (B) on day 8 of DSS treatment. (C) Frequencies of Lin−CD45+CD127+ cells and CD4+ T cells expressing eGFP in small intestine lamina propria in multiple mice (n = 8). (D) Body weight loss as a percentage of initial weight at day 8 of DSS treatment (n = 6). D0, day 0; D8, day 8. (E and F) Frequencies of Lin−CD45+CD127+ cells that lacked markers for both ILC2s and ILC3s in small intestine lamina propria of mice treated with DSS in drinking water for 8 d (n = 5; E) or in mice infected for 8 d with C. rodentium (n = 5; F). Frequencies of ILC2s and ILC3s are shown as controls. Bars indicate means ± SD. Data were pooled from two independent experiments (C) or are representative of two independent experiments (D–F).

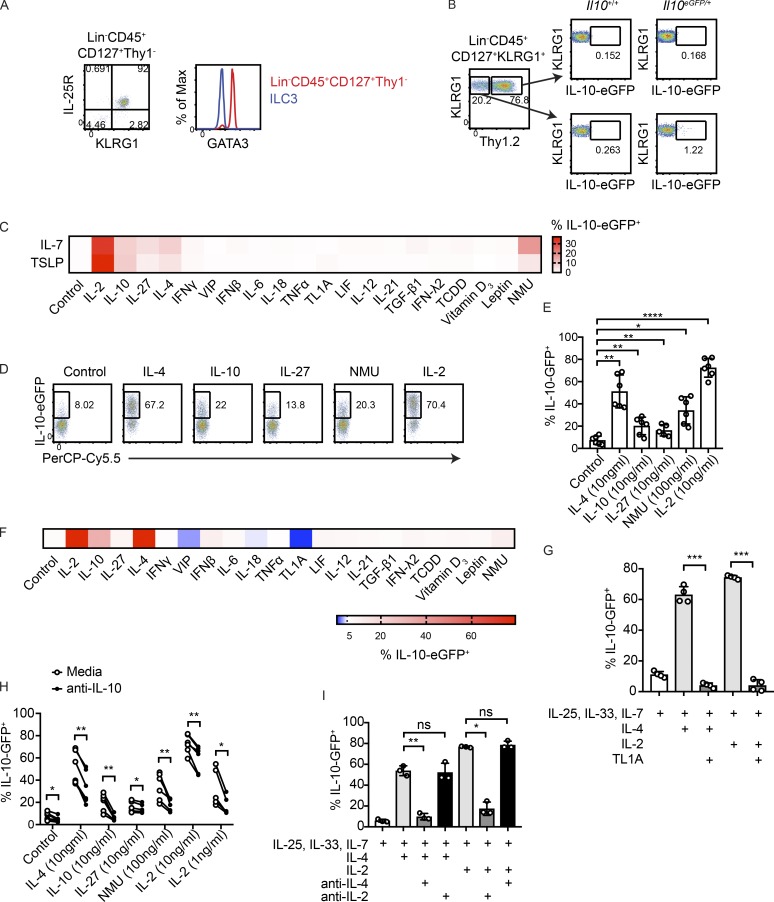

IL-10 production is inducible in intestinal ILC2s by IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-27, and neuromedin U (NMU), and suppressed by TL1A

While IL-10–eGFP expression was absent in Lin−CD127+Thy1+ ILCs, a small population of Lin−CD127+ ILCs that lacked Thy1 was found to express eGFP in the small intestine, but not large intestine (Fig. 1 A). Lin−CD127+Thy1− cells expressed the ILC2 markers KLRG1 and IL-25R (Fig. 4 A). Consistent with an ILC2 phenotype, Lin−CD127+Thy1− cells expressed high amounts of GATA3, a transcription factor required for ILC2 development and maintenance (Fig. 4 A; Hoyler et al., 2012). Gating on Lin−CD45+CD127+KLRG1+ ILC2s that lacked Thy1 enriched for IL-10GFP+ cells (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

IL-10 production by intestinal ILC2s is induced by IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-27, and NMU, and suppressed by TL1A. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing IL-25R, KLRG1, and GATA3 staining in Lin−CD45+CD127+Thy1− cells. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots showing expression of eGFP in Lin−CD45+CD127+KLRG1+ ILC2s that are Thy1+ and Thy1−. (C) Heatmap depicting frequencies of eGFP+ cells obtained by flow cytometric analysis of ILC2s cultured 2 d with IL-33, IL-25, and either IL-7 or TSLP, in combination with the indicated molecules. (D and E) Validation of results in C. Cells were cultured for 3 d with IL-33, IL-25, IL-7, and the indicated conditions (n = 5–6). (F) ILC2s cultured as in C using pre-activated ILC2s. (G) IL-4- or IL-2-elicited eGFP expression in ILC2s treated with TL1A (n = 4). (H and I) Isolated ILC2s were treated with IL-25, IL-33, IL-7, and the indicated molecules in the presence or absence of IL-10–blocking antibodies (n = 5–6; H) or in the presence or absence of IL-2- and IL-4–blocking antibodies (n = 3; I). Bars indicate means ± SD. Data from D, E, and H were analyzed from the same experiments. Data were pooled from two independent experiments (E and H) or are representative of two independent experiments (A, B, G, and I). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Activated lung ILC2s were previously shown to produce IL-10 after chronic papain exposure and in response to IL-2 (Miyamoto et al., 2019; Seehus et al., 2017). To identify factors that could induce IL-10 in intestinal ILC2s, purified eGFP-negative ILC2s from the small intestine lamina propria of IL-10–eGFP mice were subjected to a screen using candidate soluble mediators previously reported to impact ILC2 activity, T reg cell differentiation, and/or T reg cell function (Cardoso et al., 2017; Duerr et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2009; Josefowicz et al., 2012; Klose et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Lim et al., 2016; Mchedlidze et al., 2016; Meylan et al., 2014; Moro et al., 2016; Nussbaum et al., 2013; Ohne et al., 2016; Ricardo-Gonzalez et al., 2018; Ruiter et al., 2015; Symowski and Voehringer, 2019; Wallrapp et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2016). In this screen, cells were cultured with the ILC2-activating cytokines IL-25 and IL-33, together with either IL-7 or TSLP, and a candidate soluble mediator. Percentages of eGFP+ cells were determined by flow cytometry after 2 d. Confirming previous findings with lung ILC2s (Seehus et al., 2017), IL-2 strongly increased eGFP expression in intestinal ILC2s (Fig. 4 C). eGFP expression was also induced in ILC2s by IL-10 itself, as well as IL-27, IL-4, and the neuropeptide NMU. TSLP-treated cells did not exhibit increased eGFP production compared with IL-7–treated cells, and for that reason IL-7 was used instead of TSLP in subsequent experiments. IL-2, IL-10, IL-27, IL-4, and NMU were validated as positive regulators of IL-10 using intestinal ILC2s sorted from biological replicates (Fig. 4, D and E). A separate screen conducted with preactivated ILC2s, which had a higher baseline of eGFP across all treatments, revealed that the TNF superfamily member TL1A was a candidate negative regulator of IL-10 production in ILC2s (Fig. 4 F). TL1A was previously shown to induce IL-5 and IL-13 production by ILC2s (Meylan et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2014). Consistent with the results from the screen, TL1A strongly abrogated IL-10 production induced by IL-2 or IL-4 in vitro (Fig. 4 G).

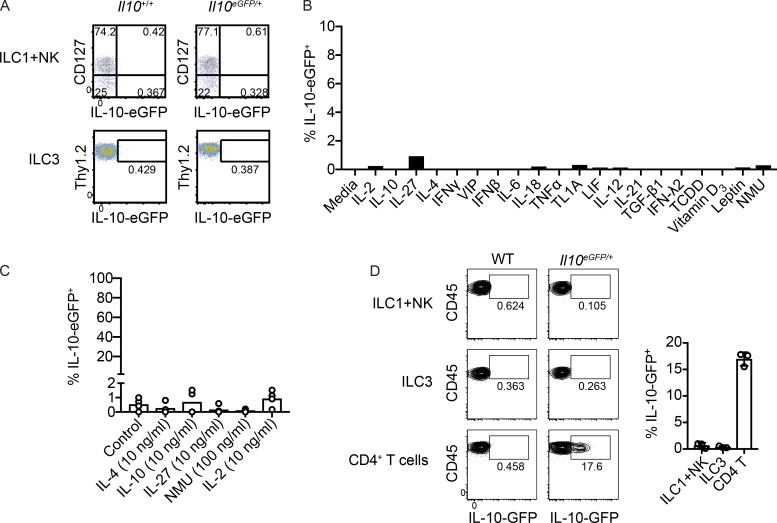

While a low percentage of eGFP was detected in ILC2s in the naive mouse small intestine, eGFP was not expressed by NK cells, ILC1s, or ILC3s (Fig. S1 A). None of the soluble mediators tested on ILC2s induced IL-10 production in activated ILC3s (Fig. S1, B and C). Additionally, IL-10 was not induced in ILC1s, NK cells, or ILC3s during Clostridium difficile infection (Fig. S1 D). Use of Tg Il10 bacterial artificial chromosome in transgene (10BiT) IL-10 reporter mice confirmed that KLRG1+ ILC2s, but not other lineage-negative ILCs, produced IL-10 at steady state (data not shown; Maynard et al., 2007). Although this area requires further investigation, these results suggest that small intestine ILC1s and ILC3s are less poised to produce IL-10 than small intestine ILC2s.

Figure S1.

IL-10 production in NK cells, ILC1s, and ILC3s. (A) Expression of IL-10–eGFP in NK1.1+ cells (pooled ILC1s and NK cells) and ILC3s isolated from naive small intestine lamina propria. (B) Screen for IL-10 elicitors using sorted small intestine ILC3s cultured for 2 d with IL-23, IL-1β, IL-7, and a candidate mediator. (C) Expression of IL-10–eGFP in small intestine lamina propria ILC3s sorted from biological replicates and cultured for 2 d with IL-23, IL-1β, IL-7, and molecules that were found to induce IL-10 in ILC2s (n = 4). (D) Expression of IL-10–eGFP in NK1.1+ cells (pooled ILC1s and NK cells), ILC3s, and CD4+ T cells isolated from small intestine lamina propria of mice 4 d after inoculation with 108 CFU of C. difficile VPI 10463 (n = 3). Bars indicate means ± SD. Data from A, C, and D are representative of two independent experiments.

Secreted IL-10 activates IL-10 production through a positive feedback loop

Our results suggested that IL-10 secreted by ILC2s might activate a feedback loop that amplified IL-10 production. To determine the impact of secreted IL-10 in vitro, cultures containing ILC2s and positive regulators of IL-10 were treated with IL-10–blocking antibodies. eGFP expression in ILC2s was blunted by IL-10 inhibition, indicating that ILC2s can act to amplify IL-10 signals (Fig. 4 H). This result also provided functional validation that IL-10 protein was secreted by ILC2s. Since IL-2 and IL-4, the strongest elicitors of IL-10 in the screen, are molecules that can be secreted by ILC2s, we tested whether one of these cytokines might induce the other to activate IL-10 production (Moro et al., 2010). The use of blocking antibodies revealed that the activation of IL-10 production by IL-4 did not require IL-2, and likewise, the induction of IL-10 by IL-2 did not require IL-4 (Fig. 4 I). Thus, IL-2 and IL-4 can induce IL-10 in ILC2s independently of one another.

In this study, we showed that the ILCreg, a recently described Thy1+CD127+ IL-10–producing ILC, is not a generalizable immune population across mice. Support for this conclusion was provided by multiple experiments. First, using the same reporter mouse that was used to originally identify this population, we found no evidence for ILCregs based on IL-10 (eGFP) expression in naive mice (Wang et al., 2017). These results were not due to overly stringent lineage- or FSC/SSC-gating, since relaxing these parameters did not enable ILCreg detection. Second, while ILCregs were previously reported to be ∼13% of lineage-negative cells in small intestine lamina propria based on function marking alone (Wang et al., 2017), we found that >99% of lineage-negative, CD45+CD127+ lymphocytes were either ILC2s or ILC3s (ILC1s being excluded by lineage gating) in mice bred at WUSM. Further examination of the <1% of Lin−CD45+CD127+ cells that lacked ILC2 and ILC3 markers showed that they exhibited a high geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI) in the lineage dump channel and expressed T-bet, indicating that these rare events were lineage-positive cells that had been inadequately excluded. These data indicate that the absence of ILCregs could not be explained by insufficient eGFP fluorescence detection or reduced IL-10 production caused by environmental factors such as diet or microbiota, since regardless of eGFP production, ILCregs were absent in the small intestine. Third, analyses of C57BL/6 mice purchased from JAX, Taconic Biosciences, and Charles River Laboratories indicated that ILCregs were absent from mice from multiple facilities. Use of C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N mice showed that ILCreg detection was not caused by genetic differences between C57BL/6 substrains. Finally, there was no observed expansion of an ILC distinct from ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC3s during two models of gut inflammation (DSS colitis and C. rodentium infection) previously reported to increase ILCreg numbers, negating a generalizable role for ILCregs under these conditions (Wang et al., 2017). Taken together, these data show that ILCregs are not universally present in mice.

The possibility remains that specific microbiota may be required for the development of ILCregs. Such a strict requirement would indicate that ILCregs are unlike other ILCs, which are ubiquitously present in C57BL/6 mice across animal facilities.

In one of the first reports that identified ILC2s, sorted splenic ILC2s were shown to secrete IL-10 (Neill et al., 2010). More recently, IL-10 was shown to be produced by lung ILC2s in response to treatment with papain (Miyamoto et al., 2019; Seehus et al., 2017). In our study, we showed that a modest percentage of ILC2s produced IL-10 in the naive mouse small intestine. Production of IL-10 in intestinal ILC2s was enhanced by IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-27, and NMU, and suppressed by the TNF superfamily member TL1A. Several of the molecules found to impact IL-10 production in ILC2s have also been shown to affect IL-10 production in T cells, creating additional parallels between the two cell types (Bando and Colonna, 2016; Saraiva and O’Garra, 2010). Our finding that secreted IL-10 induced additional IL-10 production indicates that a positive feedback loop in ILC2s may rapidly suppress effector cell cytokine production via IL-10. Together, data generated from these experiments suggest that the production of IL-10 by ILC2s in vivo is tuned by the cytokine milieu, which is likely dependent on tissue microenvironment.

We feel that it is unlikely that the Lin−CD127+eGFP+ population previously identified as ILCregs was comprised of misidentified ILC2s based on reported differences between these two populations: (1) ILCregs expressed low or no GATA3 and KLRG1, while both markers are highly expressed in ILC2s; (2) ILCregs lacked lineage tracing with PLZF, which labels ILC2s due to expression of this gene in a common ILC precursor (Constantinides et al., 2014); and (3) IL-10 production in ILCregs was previously reported to be induced by TGF-β, while IL-10 production in ILC2s has been shown to be suppressed by this cytokine (Seehus et al., 2017). In addition, the types of inflammatory conditions that were previously reported to expand ILCregs would not be expected to activate ILC2s.

The physiological relevance of ILC2-derived IL-10 in the intestine remains an area for future investigation. Unique functions of IL-10 secreted by intestinal ILC2s will require further work to determine when these cells produce IL-10 in vivo, and to identify the specific cell types impacted by ILC2-derived IL-10.

Materials and methods

Animals

B6.129S6-Il10tm1Flv/J (IL-10–eGFP) mice backcrossed to C57BL/6 for over 10 generations were purchased from JAX (#008379; Kamanaka et al., 2006). IL-10–eGFP mice were then crossed to C57BL/6J mice purchased from JAX (#00064). C57BL/6N mice were purchased from Taconic Biosciences (#B6NTac) and Charles River Laboratories (#027). Mice were used for experiments at 6–14 wk of age. Both sexes were used, with the exception of the mouse vendor comparison experiments, in which male mice were purchased. Mice in vendor comparison experiments were euthanized within 48 h of arriving at our animal facility. All animals were housed in specific pathogen-free facilities at WUSM in St. Louis, and studies were conducted in accordance with the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

Cell isolation

Single-cell suspensions of intestinal lamina propria were generated as previously described (Bando et al., 2018). Peyer’s patches were removed from small intestines. Large intestines consisted of both cecum and colon combined. Intestines were cleaned and opened lengthwise and then agitated for 20 min in HBSS (Gibco) that contained EDTA (Corning), bovine calf serum (Atlanta Biologics), and Hepes (Corning). Tissues were vortexed, and then agitated for an additional 20 min in fresh HBSS buffer that contained EDTA, bovine calf serum, and Hepes, followed by vortexing. Intestines were then rinsed with HBSS supplemented with Hepes to remove traces of EDTA, and then digested with collagenase IV (Sigma) in complete RPMI under agitation for 40 min for small intestines or 1 h for large intestines. Complete RPMI contained RPMI from Sigma enriched with 10% bovine calf serum, L-alanyl-L-glutamine dipeptide (Gibco), nonessential amino acids (Corning), Hepes, kanamycin sulfate (Gibco), sodium pyruvate (Corning), and β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). Digests were filtered through 100-micron nylon mesh and subjected to density gradient centrifugation using Percoll (GE Healthcare).

Flow cytometry

Cells were incubated with Fragment, crystallizable (Fc) block for 15–20 min, and then stained with primary antibodies (Table S1) for 20–30 min in buffer that contained Fc block. Stains with fluorescently labeled streptavidin were incubated for 20 min. Live cells were stained using a Live/Dead Fixable Cell Stain Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or DAPI (Sigma). Intracellular staining was conducted using the eBioscience Transcription Factor staining kit. Cells were run on a FACSCantoII (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo (FlowJo LLC). Lineage cocktails included antibodies to CD3e, CD4, CD5, CD8a, CD19, CD11b, CD11c, Gr-1, NK1.1, Ter119, and B220. “Modified” lineage cocktails included antibodies to CD3e, CD4, CD5, CD8a, CD19, CD11b, CD11c, Gr-1, NK1.1, Ter119, and F4/80.

Table S1. Antibodies and secondary reagents.

| Antibody or secondary reagent | Catalog number | Company |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD3e PerCP-cy5.5 | 100328 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD4 PerCP-cy5.5 | 100434 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD5 PerCP-cy5.5 | 100624 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD8a PerCP-cy5.5 | 100734 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD19 PerCP-cy5.5 | 115534 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD11b PerCP-cy5.5 | 101228 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD11c PerCP-cy5.5 | 45-0114-82 | eBioscience |

| Anti-Gr-1 PerCP-cy5.5 | 108428 | BioLegend |

| Anti-NK1.1 PerCP-cy5.5 | 108728 | BioLegend |

| Anti-Ter119 PerCP-cy5.5 | 116228 | BioLegend |

| Anti-B220 PerCP-cy5.5 | 103236 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD45 APC/cy7 | 103116 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD127 biotin | 135006 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD90.2 APC | 105312 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD4 APC | 17-0041-83 | eBioscience |

| Anti-CD11c PE-cy7 | 117318 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD11b APC/cy7 | 101226 | BioLegend |

| Anti-B220 Pacific Blue | 103227 | BioLegend |

| Anti-CD3e BV421 | 562600 | BD Biosciences |

| Anti-GATA3 AF488 | 560163 | BD Biosciences |

| Anti-RORgt PE | 12-6988-82 | eBioscience |

| Anti-F4/80 PerCP-cy5.5 | 123128 | BioLegend |

| Anti-T-bet BV421 | 563318 | BD Biosciences |

| Anti-IL-25R PE | 12-7361-80 | eBioscience |

| Anti-KLRG1 APC | 138412 | BioLegend |

| Anti-NKp46 biotin | 137616 | BioLegend |

| Anti-NK1.1 PE-cy7 | 108714 | BioLegend |

| SA-PE-cy7 | 25-4317-82 | eBioscience |

| SA-BV421 | 563259 | BD Biosciences |

Intestinal inflammation models

Mice were infected with 2 × 109 C. rodentium (strain DBS100; ATCC) via oral gavage. For DSS colitis studies, mice were provided 3% DSS (#160110; MP Biomedicals) in drinking water.

Cell culture

ILC2s and ILC3s were purified from small intestine lamina propria with an Aria II (BD Biosciences). 12 × 103 ILC2s were cultured in complete RPMI with 10 ng/ml IL-33 and IL-25 in the presence of IL-7 or TSLP (50 ng/ml) for 2 d (screens) or 3 d (validation studies) with candidate molecules (Table S2). 50 × 103 ILC3s werecultured with 10 ng/ml IL-1β and IL-23 in the presence of IL-7 for 2 d. For screens, cells were treated with 10 ng/ml of candidate molecules, except for IL-27, VIP, leptin, and NMU (50 ng/ml); 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzodioxin (31 nM); and vitamin D3 (100 nM). Blocking antibodies to IL-2, IL-4, and IL-10 were purchased from BioXCell and were used at a concentration of 15 μg/ml. To generate pre-activated ILC2s, sorted ILC2s were cultured for 7 d with IL-25, IL-33, and IL-7 before being resorted for eGFP-negative cells.

Table S2. Soluble mediators.

| Molecule | Catalog number | Company |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse IL-25 | 1399-IL | R&D |

| Mouse IL-33 | 210-33 | Peprotech |

| Mouse TSLP | 555-TS | R&D |

| Mouse IL-2 | 402-ML | R&D |

| Mouse IL-10 | 210-10 | Peprotech |

| Mouse IL-27 | 577402 | BioLegend |

| Mouse IL-4 | 214-14 | Peprotech |

| Mouse IFNγ | 315-05 | Peprotech |

| VIP | 1911 | Tocris |

| Mouse IFNβ | 12400-1 | PBL Assay Science |

| Mouse IL-6 | 406-ML | R&D |

| Mouse IL-18 | 767002 | BioLegend |

| Mouse TL1A | 1896-TL/CF | R&D |

| TNFα | 315-01A | Peprotech |

| Human LIF | 300-05 | Peprotech |

| Mouse IL-12 p70 | 210-12 | Peprotech |

| Mouse IL-21 | 210-21 | Peprotech |

| Human TGF-β1 | 100-21 | Peprotech |

| Human IFN-λ2 | 300-02K | Peprotech |

| 2,3,7,8-TCDD | 48599 | Supelco |

| 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 | D1530 | Sigma |

| Human leptin | 300-27 | Peprotech |

| Human NMU-25 | 17617 | Cayman Chemical |

| Mouse IL-1β | 401-ML | R&D |

| Mouse IL-23 | 1887-ML | R&D |

Statistical analysis

Paired and unpaired student’s t tests and one-way ANOVA were conducted using Prism software.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows IL-10–eGFP expression in intestinal NK cells, ILC1s, and ILC3s. Table S1 lists catalog numbers for antibodies used for flow cytometry. Table S2 lists catalog numbers for soluble mediators used in screens.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Brian Edelson and Nicholas Jarjour for reagents (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO). We would also like to thank Michael Patnode and Adelle McFarland for scientific discussion and for critical reading of the manuscript.

These studies were supported by the National Institutes of Health grants AI095542, DE025884, and AI134236 (to M. Colonna); AI134035 (to M. Colonna); and K99 DK118110 (to J.K. Bando). M. Colonna received research support from Pfizer.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions:J.K. Bando, S. Gilfillan, M. Cella, and M. Colonna designed experiments. J.K. Bando, S. Gilfillan, B. DiLuccia, J.L. Fachi, and C. Sécca performed experiments. J.K. Bando analyzed data and wrote the paper.

References

- Bando J.K., and Colonna M.. 2016. Innate lymphoid cell function in the context of adaptive immunity. Nat. Immunol. 17:783–789. 10.1038/ni.3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando J.K., Gilfillan S., Song C., McDonald K.G., Huang S.C., Newberry R.D., Kobayashi Y., Allan D.S.J., Carlyle J.R., Cella M., and Colonna M.. 2018. The tumor necrosis factor superfamily member RANKL suppresses effector cytokine production in group 3 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 48:1208–1219.e4. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg D.J., Davidson N., Kühn R., Müller W., Menon S., Holland G., Thompson-Snipes L., Leach M.W., and Rennick D.. 1996. Enterocolitis and colon cancer in interleukin-10-deficient mice are associated with aberrant cytokine production and CD4(+) TH1-like responses. J. Clin. Invest. 98:1010–1020. 10.1172/JCI118861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzk N., Gronke K., and Diefenbach A.. 2018. Innate lymphoid cells, mediators of tissue homeostasis, adaptation and disease tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 286:86–101. 10.1111/imr.12718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E.M., Kenny D.J., and Xavier R.J.. 2019. Gut microbiota regulation of T cells during inflammation and autoimmunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 37:599–624. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso V., Chesné J., Ribeiro H., García-Cassani B., Carvalho T., Bouchery T., Shah K., Barbosa-Morais N.L., Harris N., and Veiga-Fernandes H.. 2017. Neuronal regulation of type 2 innate lymphoid cells via neuromedin U. Nature. 549:277–281. 10.1038/nature23469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes-Barragan L., Chai J.N., Tianero M.D., Di Luccia B., Ahern P.P., Merriman J., Cortez V.S., Caparon M.G., Donia M.S., Gilfillan S., et al. . 2017. Lactobacillus reuteri induces gut intraepithelial CD4+CD8αα+ T cells. Science. 357:806–810. 10.1126/science.aah5825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinides M.G., McDonald B.D., Verhoef P.A., and Bendelac A.. 2014. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 508:397–401. 10.1038/nature13047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson N.J., Leach M.W., Fort M.M., Thompson-Snipes L., Kühn R., Müller W., Berg D.J., and Rennick D.M.. 1996. T helper cell 1-type CD4+ T cells, but not B cells, mediate colitis in interleukin 10-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 184:241–251. 10.1084/jem.184.1.241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerr C.U., McCarthy C.D., Mindt B.C., Rubio M., Meli A.P., Pothlichet J., Eva M.M., Gauchat J.F., Qureshi S.T., Mazer B.D., et al. . 2016. Type I interferon restricts type 2 immunopathology through the regulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 17:65–75. 10.1038/ni.3308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl G., Colonna M., Di Santo J.P., and McKenzie A.N.. 2015. Innate lymphoid cells. Innate lymphoid cells: a new paradigm in immunology. Science. 348:aaa6566 10.1126/science.aaa6566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W., Thompson L., Zhou Q., Putheti P., Fahmy T.M., Strom T.B., and Metcalfe S.M.. 2009. Treg versus Th17 lymphocyte lineages are cross-regulated by LIF versus IL-6. Cell Cycle. 8:1444–1450. 10.4161/cc.8.9.8348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyler T., Klose C.S., Souabni A., Turqueti-Neves A., Pfeifer D., Rawlins E.L., Voehringer D., Busslinger M., and Diefenbach A.. 2012. The transcription factor GATA-3 controls cell fate and maintenance of type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 37:634–648. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov I.I., Frutos R.L., Manel N., Yoshinaga K., Rifkin D.B., Sartor R.B., Finlay B.B., and Littman D.R.. 2008. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe. 4:337–349. 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefowicz S.Z., Lu L.F., and Rudensky A.Y.. 2012. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30:531–564. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamanaka M., Kim S.T., Wan Y.Y., Sutterwala F.S., Lara-Tejero M., Galán J.E., Harhaj E., and Flavell R.A.. 2006. Expression of interleukin-10 in intestinal lymphocytes detected by an interleukin-10 reporter knockin tiger mouse. Immunity. 25:941–952. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose C.S.N., Mahlakõiv T., Moeller J.B., Rankin L.C., Flamar A.L., Kabata H., Monticelli L.A., Moriyama S., Putzel G.G., Rakhilin N., et al. . 2017. The neuropeptide neuromedin U stimulates innate lymphoid cells and type 2 inflammation. Nature. 549:282–286. 10.1038/nature23676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn R., Löhler J., Rennick D., Rajewsky K., and Müller W.. 1993. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 75:263–274. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Bostick J.W., Ye J., Qiu J., Zhang B., Urban J.F. Jr., Avram D., and Zhou L.. 2018. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling cell intrinsically inhibits intestinal group 2 innate lymphoid cell function. Immunity. 49:915–928.e5. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim A.I., Menegatti S., Bustamante J., Le Bourhis L., Allez M., Rogge L., Casanova J.L., Yssel H., and Di Santo J.P.. 2016. IL-12 drives functional plasticity of human group 2 innate lymphoid cells. J. Exp. Med. 213:569–583. 10.1084/jem.20151750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard C.L., Harrington L.E., Janowski K.M., Oliver J.R., Zindl C.L., Rudensky A.Y., and Weaver C.T.. 2007. Regulatory T cells expressing interleukin 10 develop from Foxp3+ and Foxp3- precursor cells in the absence of interleukin 10. Nat. Immunol. 8:931–941. 10.1038/ni1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mchedlidze T., Kindermann M., Neves A.T., Voehringer D., Neurath M.F., and Wirtz S.. 2016. IL-27 suppresses type 2 immune responses in vivo via direct effects on group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Mucosal Immunol. 9:1384–1394. 10.1038/mi.2016.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan F., Hawley E.T., Barron L., Barlow J.L., Penumetcha P., Pelletier M., Sciumè G., Richard A.C., Hayes E.T., Gomez-Rodriguez J., et al. . 2014. The TNF-family cytokine TL1A promotes allergic immunopathology through group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Mucosal Immunol. 7:958–968. 10.1038/mi.2013.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto C., Kojo S., Yamashita M., Moro K., Lacaud G., Shiroguchi K., Taniuchi I., and Ebihara T.. 2019. Runx/Cbfβ complexes protect group 2 innate lymphoid cells from exhausted-like hyporesponsiveness during allergic airway inflammation. Nat. Commun. 10:447 10.1038/s41467-019-08365-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro K., Yamada T., Tanabe M., Takeuchi T., Ikawa T., Kawamoto H., Furusawa J., Ohtani M., Fujii H., and Koyasu S.. 2010. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 463:540–544. 10.1038/nature08636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro K., Kabata H., Tanabe M., Koga S., Takeno N., Mochizuki M., Fukunaga K., Asano K., Betsuyaku T., and Koyasu S.. 2016. Interferon and IL-27 antagonize the function of group 2 innate lymphoid cells and type 2 innate immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 17:76–86. 10.1038/ni.3309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill D.R., Wong S.H., Bellosi A., Flynn R.J., Daly M., Langford T.K., Bucks C., Kane C.M., Fallon P.G., Pannell R., et al. . 2010. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 464:1367–1370. 10.1038/nature08900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum J.C., Van Dyken S.J., von Moltke J., Cheng L.E., Mohapatra A., Molofsky A.B., Thornton E.E., Krummel M.F., Chawla A., Liang H.E., and Locksley R.M.. 2013. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 502:245–248. 10.1038/nature12526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohne Y., Silver J.S., Thompson-Snipes L., Collet M.A., Blanck J.P., Cantarel B.L., Copenhaver A.M., Humbles A.A., and Liu Y.J.. 2016. IL-1 is a critical regulator of group 2 innate lymphoid cell function and plasticity. Nat. Immunol. 17:646–655. 10.1038/ni.3447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo-Gonzalez R.R., Van Dyken S.J., Schneider C., Lee J., Nussbaum J.C., Liang H.E., Vaka D., Eckalbar W.L., Molofsky A.B., Erle D.J., and Locksley R.M.. 2018. Tissue signals imprint ILC2 identity with anticipatory function. Nat. Immunol. 19:1093–1099. 10.1038/s41590-018-0201-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiter B., Patil S.U., and Shreffler W.G.. 2015. Vitamins A and D have antagonistic effects on expression of effector cytokines and gut-homing integrin in human innate lymphoid cells. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 45:1214–1225. 10.1111/cea.12568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva M., and O’Garra A.. 2010. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10:170–181. 10.1038/nri2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehus C.R., Kadavallore A., Torre B., Yeckes A.R., Wang Y., Tang J., and Kaye J.. 2017. Alternative activation generates IL-10 producing type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Commun. 8:1900 10.1038/s41467-017-02023-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg G.F., and Artis D.. 2015. Innate lymphoid cells in the initiation, regulation and resolution of inflammation. Nat. Med. 21:698–708. 10.1038/nm.3892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symowski C., and Voehringer D.. 2019. Th2 cell-derived IL-4/IL-13 promote ILC2 accumulation in the lung by ILC2-intrinsic STAT6 signaling in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 49:1421–1432. 10.1002/eji.201948161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivier E., Artis D., Colonna M., Diefenbach A., Di Santo J.P., Eberl G., Koyasu S., Locksley R.M., McKenzie A.N.J., Mebius R.E., et al. . 2018. Innate lymphoid cells: 10 years on. Cell. 174:1054–1066. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallrapp A., Riesenfeld S.J., Burkett P.R., Abdulnour R.E., Nyman J., Dionne D., Hofree M., Cuoco M.S., Rodman C., Farouq D., et al. . 2017. The neuropeptide NMU amplifies ILC2-driven allergic lung inflammation. Nature. 549:351–356. 10.1038/nature24029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Xia P., Chen Y., Qu Y., Xiong Z., Ye B., Du Y., Tian Y., Yin Z., Xu Z., and Fan Z.. 2017. Regulatory innate lymphoid cells control innate intestinal inflammation. Cell. 171:201–216.e18. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X., Pappu R., Ramirez-Carrozzi V., Ota N., Caplazi P., Zhang J., Yan D., Xu M., Lee W.P., and Grogan J.L.. 2014. TNF superfamily member TL1A elicits type 2 innate lymphoid cells at mucosal barriers. Mucosal Immunol. 7:730–740. 10.1038/mi.2013.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H., Zhang X., Castillo E.F., Luo Y., Liu M., and Yang X.O.. 2016. Leptin enhances TH2 and ILC2 responses in allergic airway disease. J. Biol. Chem. 291:22043–22052. 10.1074/jbc.M116.743187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]