Thymocyte egress is a critical determinant of T cell homeostasis and adaptive immunity. Du et al. describe unexpected roles of mevalonate metabolism–fueled protein geranylgeranylation, but not farnesylation, in driving thymocyte egress through modulating Cdc42 and Pak activities.

Abstract

Thymocyte egress is a critical determinant of T cell homeostasis and adaptive immunity. Despite the roles of G protein–coupled receptors in thymocyte emigration, the downstream signaling mechanism remains poorly defined. Here, we report the discrete roles for the two branches of mevalonate metabolism–fueled protein prenylation pathway in thymocyte egress and immune homeostasis. The protein geranylgeranyltransferase Pggt1b is up-regulated in single-positive thymocytes, and loss of Pggt1b leads to marked defects in thymocyte egress and T cell lymphopenia in peripheral lymphoid organs in vivo. Mechanistically, Pggt1b bridges sphingosine-1-phosphate and chemokine-induced migratory signals with the activation of Cdc42 and Pak signaling and mevalonate-dependent thymocyte trafficking. In contrast, the farnesyltransferase Fntb, which mediates a biochemically similar process of protein farnesylation, is dispensable for thymocyte egress but contributes to peripheral T cell homeostasis. Collectively, our studies establish context-dependent effects of protein prenylation and unique roles of geranylgeranylation in thymic egress and highlight that the interplay between cellular metabolism and posttranslational modification underlies immune homeostasis.

Introduction

T cells play a crucial role in adaptive immunity to foreign pathogens and malignancies. For effective immunity, the peripheral T cell pool must be maintained by combinatorial effects of developmental and peripheral homeostatic programs. The thymic microenvironment provides the instructive cues for T cell development, which culminates in the generation of mature T cells with a diverse repertoire exiting from the thymus to peripheral organs. Various chemokines, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), and their receptors direct thymocyte migration within and out of the thymus (Lancaster et al., 2018; Cyster and Schwab, 2012). In particular, thymocyte migration from the cortex to the medulla is critically dependent upon the chemokine receptor CCR7 (Ueno et al., 2004; Kwan and Killeen, 2004; Kurobe et al., 2006), whereas subsequent egress from the medulla to the blood is mediated by the S1P receptor 1 (S1P1; Matloubian et al., 2004). Expression of CCR7 and S1P1 is tightly regulated by the transcription factors Klf2, Foxo1, and Gfi1 (Carlson et al., 2006; Kerdiles et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2017), while the production of the ligands for these receptors is also under precise spatiotemporal control (Baeyens et al., 2015; Lancaster et al., 2018). Despite the emerging information on the functional importance and upstream signals for these chemokines and receptors, the pathways downstream of chemokine receptors, especially those integrating thymocyte migratory signals, remain poorly defined.

The past few years have witnessed remarkable advances in immunometabolism, in part by establishing the central roles of metabolic reprogramming for T cell activation and fate decisions (Buck et al., 2017; Geltink et al., 2018). The application of this concept to immune development and homeostasis is an emerging area in immunology. For instance, we recently described dynamic rewiring of metabolic programs in early thymocyte development and a key role for anabolic and oxidative metabolism in directing αβ and γδ T cell fate decisions (Yang et al., 2018). Interestingly, thymic egress is required for the establishment of metabolic quiescence in recent thymic emigrants (Zhang et al., 2018), and S1P1 orchestrates energetic fitness of naive T cells in the periphery (Mendoza et al., 2017). However, whether and how thymocyte egress is regulated by cellular metabolism and the underlying signaling pathways remain unclear.

The mevalonate metabolic pathway generates isoprenoids (geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate and farnesyl pyrophosphate) that serve as posttranslational lipid modifications of proteins at carboxyl-terminal CaaX motifs (Wang and Casey, 2016; Palsuledesai and Distefano, 2015). These modifications, called protein prenylation, are catalyzed by the cytosolic enzymes protein geranylgeranyltransferase type I (GGTase-I; modification called geranylgeranylation) and protein farnesyltransferase (FTase; modification called farnesylation), respectively. Protein prenylation affects the subcellular localization, protein–protein interaction, and stability of proteins (Palsuledesai and Distefano, 2015; Wang and Casey, 2016). While recent studies have linked protein prenylation to the suppression of inflammatory responses in macrophages (Akula et al., 2016), in part by dampening small GTPase activity (Khan et al., 2011), the physiological function and molecular mechanisms of protein prenylation in the adaptive immune system, especially in T cells, are unknown.

Capitalizing on genetic models to specifically disrupt protein geranylgeranylation or farnesylation by deletion of Pggt1b (encoding GGTase-I catalytic β-subunit) or Fntb (encoding FTase catalytic β-subunit), respectively, we demonstrate crucial roles for the protein prenylation pathway in thymocyte egress. Unexpectedly, protein geranylgeranylation, but not farnesylation, is selectively required for this process. Expression of Pggt1b is up-regulated in single-positive (SP) thymocytes compared with double-positive (DP) cells, and loss of Pggt1b impairs thymocyte egress, leading to severe T cell lymphopenia in peripheral lymphoid organs. Pggt1b promotes the activity of the Cdc42–Pak–Tiam1 signaling axis, and Pggt1b-deficient SP thymocytes have impaired actin polarization and chemotaxis in response to chemokines. In sharp contrast to Pggt1b deficiency, loss of Fntb does not affect thymocyte egress and instead disrupts peripheral T cell homeostasis. Collectively, our results establish mevalonate metabolism–fueled posttranslational modifications as fundamental and selective regulators of thymocyte egress and peripheral immune homeostasis.

Results and discussion

Pggt1b deficiency leads to peripheral lymphopenia but accumulation of mature thymocytes

To investigate the function of protein geranylgeranylation in T cells, we generated mice with T cell–specific deletion of Pggt1b (Pggt1b−/−) by crossing loxP-flanked Pggt1b alleles (Pggt1bfl/fl; Sjogren et al., 2007) with CD4-Cre transgenic mice, which express Cre recombinase starting at the late double-negative (DN) stage (Lee et al., 2001). Pggt1b was efficiently deleted in CD4SP, CD8SP and DP thymocytes isolated from Pggt1b−/− mice (Fig. S1 A). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that Pggt1b deficiency resulted in greatly reduced frequencies and numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen, peripheral LNs (PLNs), mesenteric LNs (MLNs), and blood (Fig. 1, A–C). The remaining peripheral T cells in Pggt1b−/− mice showed hyperactivation phenotypes, as indicated by the reduction of CD44loCD62Lhi naive cells and accumulation of CD44hiCD62Llo effector/memory cells (Fig. S1, B and C), excessive cytokine production (Fig. S1 D), and increased expression of the proliferative marker Ki-67 (Fig. S1 E), while cell apoptosis as detected by active caspase-3 staining was largely undisturbed (Fig. S1 F). Immunofluorescence microscopy also revealed the significant reduction of T cells in PLN of Pggt1b−/− mice (Fig. 1 D). Thus, Pggt1b deficiency results in profound T cell lymphopenia in peripheral lymphoid organs.

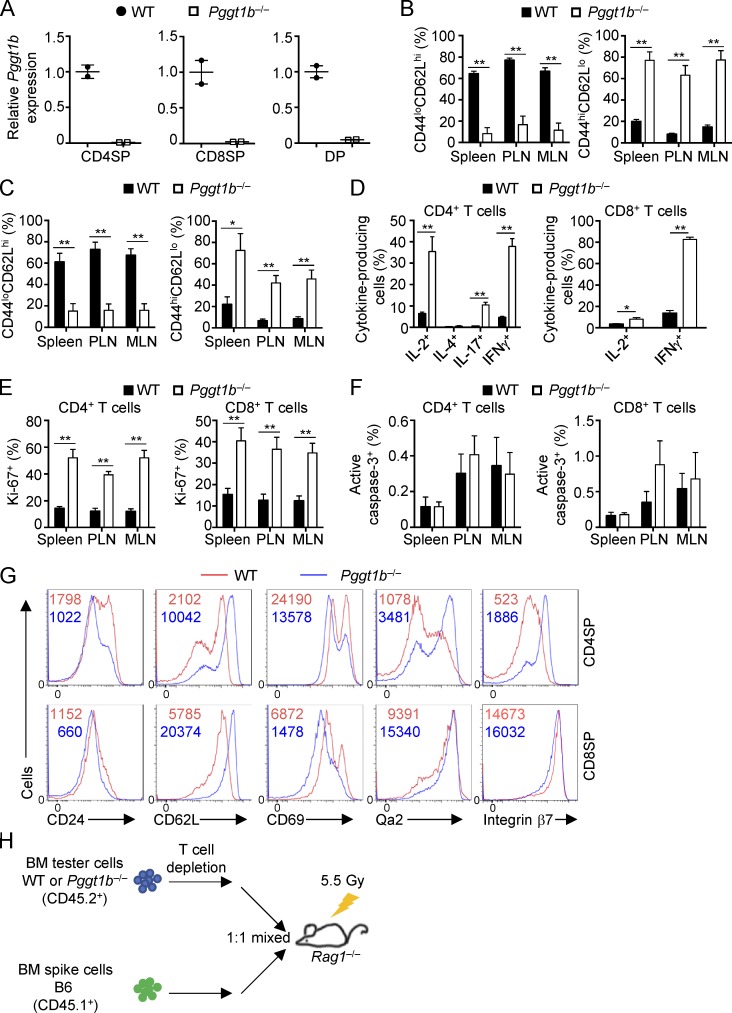

Figure S1.

Pggt1b mRNA expression, peripheral immune homeostasis, and thymic maturation marker expression in WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (A) Real-time PCR analyses of Pggt1b mRNA expression in CD4SP, CD8SP, and DP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (B and C) Frequencies of CD44loCD62Lhi naive and CD44hiCD62Llo effector/memory cells in CD4+ (B) or CD8+ (C) T cells from spleen, PLNs, and MLNs of WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (D) Frequencies of cytokine-producing cells in splenic CD4+ (left) or CD8+ (right) T cells from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (E and F) Frequencies of Ki-67+ (E) and active caspase-3+ (F) cells in CD4+ (left) or CD8+ (right) T cells from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (G) Flow cytometry analysis of CD24, CD62L, CD69, Qa2, and integrin β7 expression on CD4SP and CD8SP cells from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (H) Strategy for generation of mixed BM chimeras. BM cells from CD45.2+ WT or Pggt1b−/− mice were mixed with BM cells from CD45.1+ mice at a 1:1 ratio and transferred into sublethally irradiated Rag1−/− mice. Numbers in graphs indicate MFI. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test in B–E. Data are from four (B, C, E, and F) or three (D and G) independent experiments.

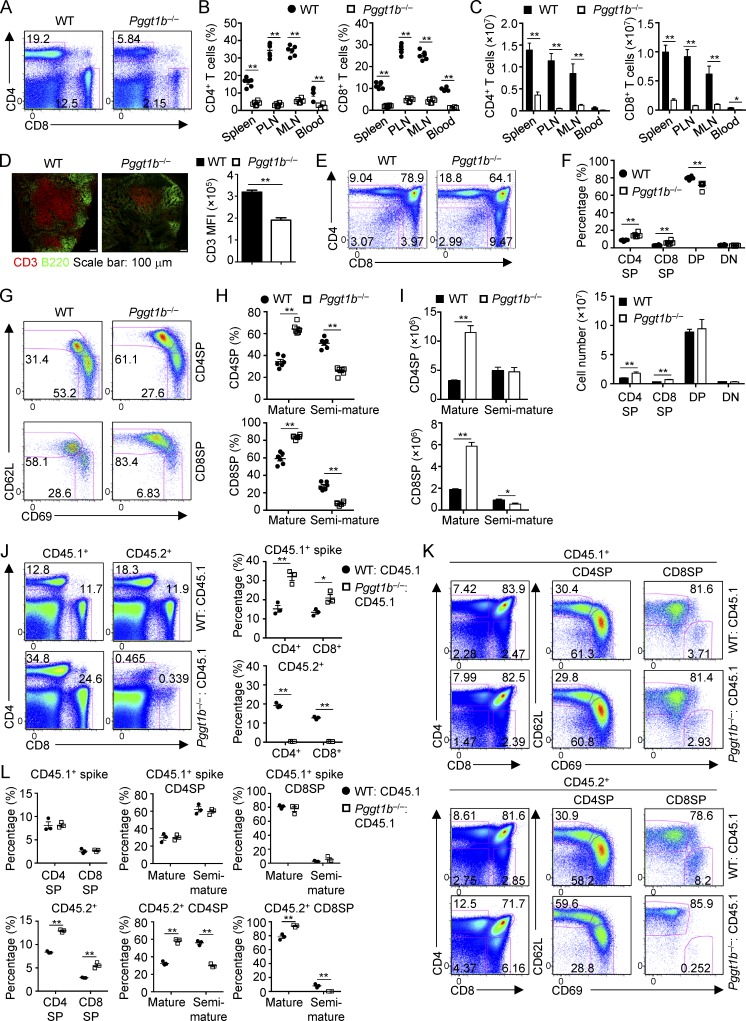

Figure 1.

Pggt1b deficiency leads to lymphopenia of peripheral T cells and accumulation of mature thymocytes in a cell-autonomous manner. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations in WT and Pggt1b−/− (Pggt1bfl/fl; CD4-Cre) mice. (B and C) Frequencies (B) and numbers (C) of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen, PLNs, MLNs, and blood of WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. 100 µl blood was used for cell number counting. (D) Immunofluorescence staining (left) of frozen tissue sections of PLNs from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice for B cells (B220; green) and T cells (CD3; red) and statistical analysis (right) of CD3 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). (E and F) Flow cytometry analysis (E) and frequencies (F, top) and numbers (F, bottom) of thymic T cell populations in WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (G–I) Flow cytometry analysis (G), frequencies (H), and numbers (I) of mature (CD62LhiCD69lo) and semimature (CD62LloCD69hi) CD4SP (top) and CD8SP (bottom) thymocytes in WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (J) Flow cytometry analysis (left) and frequencies (right) of splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations derived from CD45.1+ spike and CD45.2+ WT or Pggt1b−/− BM cells in the mixed BM chimeras. (K and L) Flow cytometry analysis (K) and frequencies (L) of thymic T cell populations derived from CD45.1+ spike and CD45.2+ WT or Pggt1b−/− BM cells in mixed BM chimeras. Numbers in gates indicate percentage of cells. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test in B–D, F, H–J, and L. Data are from three (A–C and E–I) or two (D and J–L) independent experiments.

We next examined the thymocyte populations in Pggt1b−/− mice and found that thymic development of Pggt1b−/− T cells was grossly normal (Fig. 1, E and F). However, in sharp contrast to T cell lymphopenia in peripheral lymphoid organs of Pggt1b−/− mice, the frequencies and numbers of CD4SP and CD8SP cells, but not DN or DP cells, were significantly increased in the thymus of Pggt1b−/− mice (Fig. 1, E and F). CD4SP or CD8SP cells contain CD62LhiCD69lo mature and CD62LloCD69hi semimature subpopulations, and only mature SP cells have the capacity to egress from the thymus to peripheral lymphoid organs (Carlson et al., 2006; Phee et al., 2014). Between these SP thymocyte subsets, CD62LhiCD69lo mature, but not CD62LloCD69hi semimature, CD4SP and CD8SP cells accumulated in the thymus of Pggt1b−/− mice (Fig. 1, G–I). Consistent with this notion, the expression of CD62L and other maturation markers, such as Qa2 and integrin β7, was increased in Pggt1b-deficient CD4SP and CD8SP cells, whereas immature cell markers CD24 and CD69 were decreased (Fig. S1 G). Thus, Pggt1b deficiency results in selective accumulation of mature CD4SP and CD8SP cells in the thymus.

A cell-intrinsic role of Pggt1b in T cell homeostasis

To determine whether T cell lymphopenia and increased mature SP thymocytes in Pggt1b−/− mice were a cell-autonomous effect or secondary to altered microenvironment, we generated mixed bone marrow (BM) chimeras by reconstituting irradiated Rag1−/− mice with a 1:1 mixture of WT or Pggt1b−/− (CD45.2+; donor) and WT (CD45.1+; spike) BM cells (Fig. S1 H). In the mixed BM chimeras containing Pggt1b-deficient donors, the frequencies of splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were significantly lower as compared with the WT counterparts, accompanied by a reciprocal increase of CD45.1+ BM cell-derived T cells (Fig. 1 J). This observation indicates a competitive disadvantage of peripheral T cells in the absence of Pggt1b. In contrast, the frequencies of CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes derived from the Pggt1b-deficient donors were significantly higher than either CD45.2+ WT or CD45.1+ spike controls (Fig. 1, K and L). Further, these mutant thymocytes contained elevated frequency of mature and reduced frequency of semimature SP cells (Fig. 1, K and L). Altogether, Pggt1b deficiency leads to a cell-intrinsic reduction in peripheral T cells and the accumulation of mature thymocytes.

Pggt1b deficiency blocks thymocyte egress and in vitro chemotaxis and polarization

We next determined the cellular mechanisms underlying Pggt1b-mediated regulation of thymocyte and peripheral immune homeostasis. First, we hypothesized that Pggt1b deficiency may alter proliferation and/or apoptosis of thymocytes. To this end, we examined the proliferation and apoptosis of Pggt1b-deficient SP thymocytes by flow cytometry analysis of Ki-67 and active caspase-3 expression, respectively. Pggt1b deficiency did not result in abnormal apoptosis of SP thymocytes (Fig. S2 A). Increased proliferation also was unlikely to account for the increase of mature SP thymocytes, as Pggt1b-deficient mature SP cells had significantly impaired proliferation (Fig. S2 B). Further, induction of CD69 and TCR on DP thymocytes, which are early events associated with positive selection (Shi et al., 2017), was comparable between WT and Pggt1b−/− mice (Fig. S2 C).

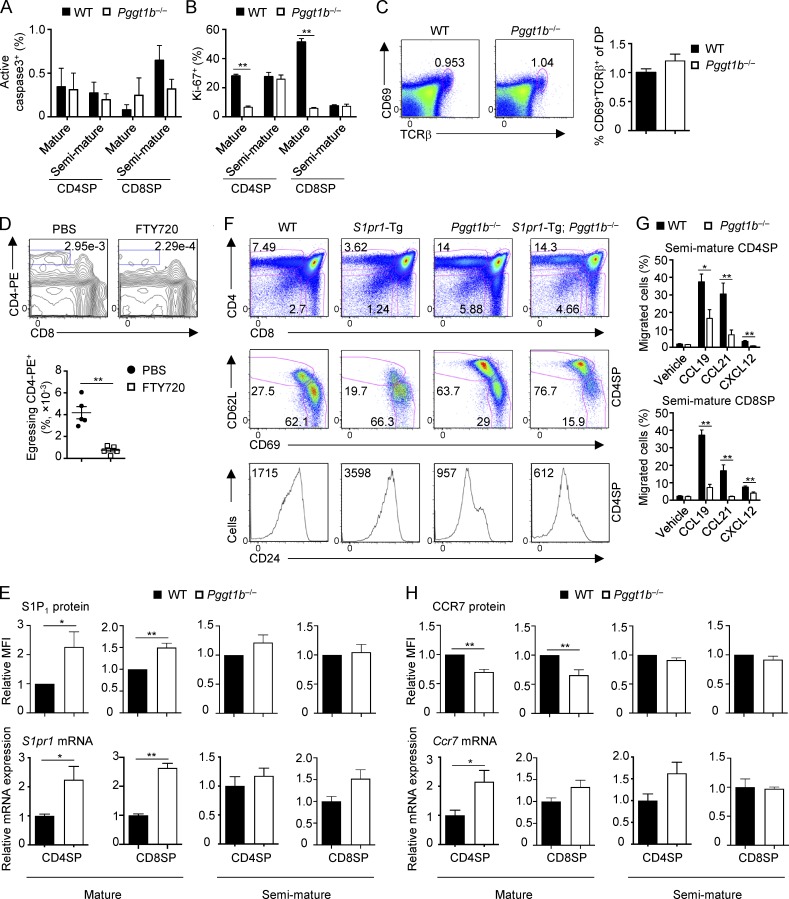

Figure S2.

Homeostasis and migration of WT and Pggt1b−/− thymocytes. (A and B) Frequencies of active caspase-3+ (A) and Ki-67+ (B) cells in mature and semimature CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (C) Flow cytometry analysis (left) and frequency (right) of thymic CD69+TCRβ+ DP cells in WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (D) Flow cytometry analysis (upper) and statistics (lower) of egressing CD4SP thymocytes gated as CD4-PE+CD8− cells in WT mice treated with PBS or FTY720 (to inhibit egress) for 16 h. (E) Flow cytometry (top) and real-time PCR (bottom) analyses of S1P1 protein and S1pr1 mRNA expression in mature and semimature SP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (F) Flow cytometry analysis of total thymic T cells (top), mature and semimature CD4SP thymocytes (middle), and CD24 expression on CD4SP thymocytes (bottom) in WT, S1pr1-Tg, Pggt1b−/−, and S1pr1-Tg; Pggt1b−/− mice. (G) Chemotactic response of semimature CD4SP (top) and CD8SP (bottom) thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. Migration through 5-µm transwells in response to CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL12 was assessed by flow cytometry after 3 h of treatment. (H) Flow cytometry (top) and real-time PCR (bottom) analyses of CCR7 protein and Ccr7 mRNA expression in mature and semimature SP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. Numbers in gates indicate percentage of cells. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test in B, D, E, G, and H. Data are from three (A and B), seven (C), two (D, F, and lower panels of E and H), four (G), or five (upper panels of E and H) independent experiments.

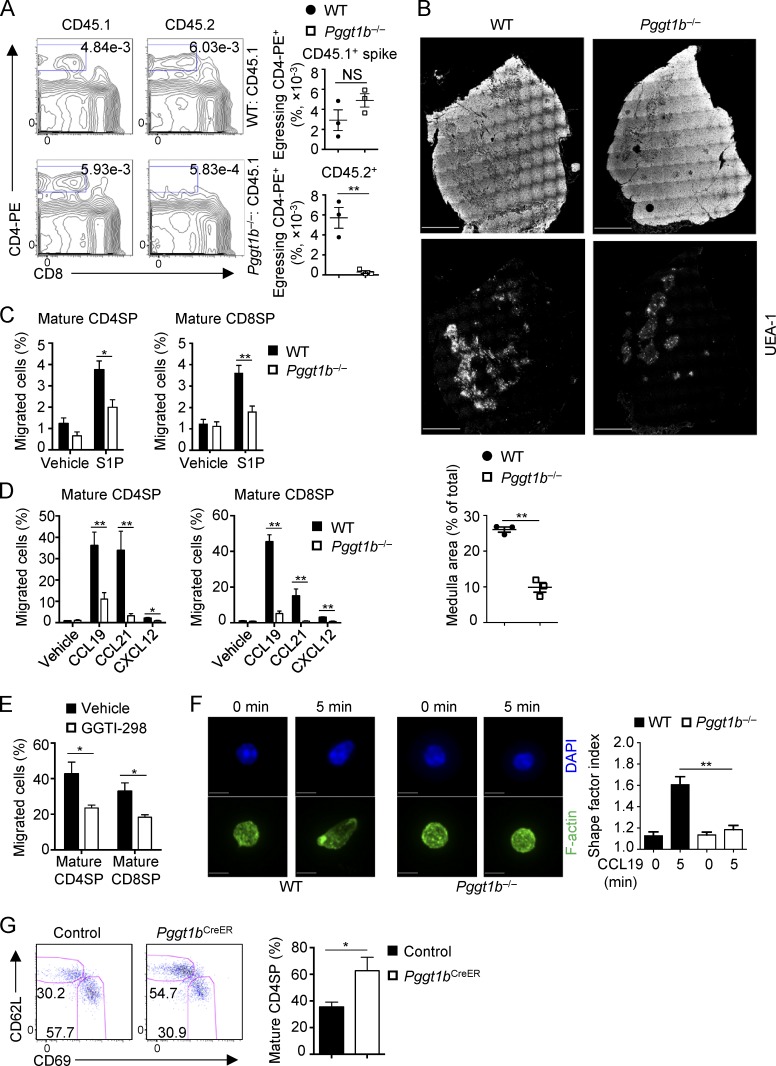

Second, we tested whether defective thymocyte egress could lead to the accumulation of mature SP thymocytes in Pggt1b−/− mice and the subsequent loss of peripheral T cells. To this end, we directly visualized egressing thymocytes by i.v. injection of PE-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody, a well-established procedure to selectively label blood-exposed egressing thymocytes (Zachariah and Cyster, 2010; Willinger et al., 2014). We first confirmed the specific labeling of egressing thymocytes (CD4-PE+) by treating mice with the high-affinity S1P agonist FTY720, which blocks thymocyte egress by inducing S1P1 degradation (Cyster and Schwab, 2012). As expected, FTY720 treatment significantly reduced the percentage of egressing CD4-PE+ cells in the thymus (Fig. S2 D). Using this method, we next examined the role of Pggt1b in thymocyte egress by injecting anti-CD4-PE antibody into the mixed BM chimeras (as described in Fig. 1), which allowed us to exclude any secondary contributions of the lymphopenic environment in order to examine cell-intrinsic effects. There was a significant reduction of egressing thymocytes in the absence of Pggt1b (Fig. 2 A). We also found that the medullary region, as indicated by immunofluorescence staining of UEA-1 (a marker for thymic medullary epithelial cells), was reduced in Pggt1b−/− mice as compared with WT mice (Fig. 2 B). This observation is consistent with the notion that impaired thymocyte egress may alter the structure of the thymus (Mou et al., 2012). Collectively, these results indicate that Pggt1b deficiency impairs thymocyte egress.

Figure 2.

Pggt1b deficiency blocks thymocyte egress and impairs its chemotaxis and actin polarization. (A) Flow cytometry analysis (left) and frequencies (right) of egressing CD4SP cells gated as CD4-PE+CD8− cells derived from CD45.2+ WT or Pggt1b−/− BM cells or CD45.1+ spike cells in mixed BM chimeras. Mixed BM chimeras generated as in Fig. S1 H were injected i.v. with 1 µg PE-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody, and thymi were harvested 4 min later for analysis. (B) Representative pictures of thymic sections showing the overall thymic morphology (top) and UEA-1 immunofluorescence staining (middle) and quantification of thymic medulla areas (bottom) of WT or Pggt1b−/− mice. Scale bar, 1 mm. (C and D) Chemotactic response of mature CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. Migration through 5-µm transwells in response to S1P (C) or CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL12 (D) was assessed by flow cytometry after 3 h of treatment. (E) Chemotactic response of WT mature CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes pretreated with vehicle or GGTI-298 for 5 h. Migration through 5-µm transwells in response to CCL19 was assessed by flow cytometry after 2 h of CCL19 treatment. (F) Representative images of actin polarization in mature CD4SP thymocytes (left) and statistics of the cell shape factor of mature CD4SP thymocytes (right) from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice after stimulation with CCL19 for 5 min. Scale bar, 5 μm. (G) Flow cytometry analysis of mature and semimature CD4SP thymocytes (left) and frequency of mature CD4SP cells among total CD4SP thymocytes (right) in control (Pggt1bfl/+ CD4-CreERT2 ROSA-YFP) and Pggt1bCreER (Pggt1bfl/fl CD4-CreERT2 ROSA-YFP) mice 7 d after tamoxifen treatment. Numbers in gates indicate percentage of cells. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test in A–E and G and one-way ANOVA in F. Data are from two (A, B, E, and F), three (G), or four (C and D) independent experiments.

Emigration of mature SP thymocytes to peripheral organs requires sensing S1P gradients that are higher in the blood than medulla (Drennan et al., 2009). To dissect the cellular basis of impaired egress of Pggt1b-deficient thymocytes, we performed in vitro chemotaxis assays. The migration of Pggt1b-deficient mature CD4SP and CD8SP cells toward S1P was reduced (Fig. 2 C). However, S1P1 expression was elevated in these cells (Fig. S2 E), suggesting a possible role of Pggt1b in promoting S1P1 downstream signaling, but not its expression. To further test the requirement of Pggt1b in S1P1-mediated thymocyte egress in vivo, we crossed Pggt1b−/− mice to S1P1 transgenic (S1pr1-Tg) mice (Liu et al., 2009). Consistent with the role of Pggt1b as a downstream pathway of S1P1 signaling, Pggt1b deficiency blocked the effects of S1P1 in promoting thymocyte egress, as revealed by the comparable percentages of total or mature CD62LhiCD69lo CD4SP cells and CD24 expression on CD4SP cells between Pggt1b−/− and S1pr1-Tg; Pggt1b−/− mice (Fig. S2 F). Thus, Pggt1b deficiency blocks S1P/S1P1-mediated thymocyte trafficking in vitro and in vivo.

Next, we tested the roles of Pggt1b in chemokine-mediated thymocyte trafficking. Pggt1b-deficient thymocytes had markedly impaired migration toward chemokines CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL12, all of which are implicated in thymocyte trafficking (James et al., 2018; Figs. 2 D and S2 G). Associated with the impaired chemotaxis of Pggt1b-deficient mature SP thymocytes to CCL19 and CCL21, these cells had slightly reduced surface expression of their receptor CCR7, although Ccr7 mRNA was increased in Pggt1b-deficient CD4SP mature thymocytes (Fig. S2 H). Moreover, acute treatment of WT thymocytes with GGTI-298, a GGTase-I–specific inhibitor (Balaz et al., 2019), further verified these effects (Fig. 2 E). Thus, protein geranylgeranylation is required for chemotactic migration of thymocytes in response to chemokines that regulate thymocyte trafficking. Moreover, these migratory defects in Pggt1b-deficient mature CD4SP thymocytes were accompanied by the failure of CCL19 to promote actin polarization (Fig. 2 F), which is crucial for cell trafficking (Ridley et al., 2003; Dupré et al., 2015). Together, Pggt1b is required for thymocyte egress in vivo and chemokine-induced migratory response and actin polarization in vitro.

To conclusively investigate the role of Pggt1b in thymocyte egress, we crossed Pggt1bfl/fl mice with the tamoxifen-inducible CD4-CreERT2 mice to generate Pggt1bfl/fl CD4-CreERT2 ROSA-YFP (Pggt1bCreER) or Pggt1bfl/+ CD4-CreERT2 ROSA-YFP (control) mice. This acute deletion strategy allowed us to bypass any potential early developmental defects, as described previously (Sledzińska et al., 2013). After tamoxifen treatment, YFP-expressing CD4SP cells contained more mature thymocytes in Pggt1bCreER mice than in control mice (Fig. 2 G), further supporting a direct role of Pggt1b in thymocyte egress.

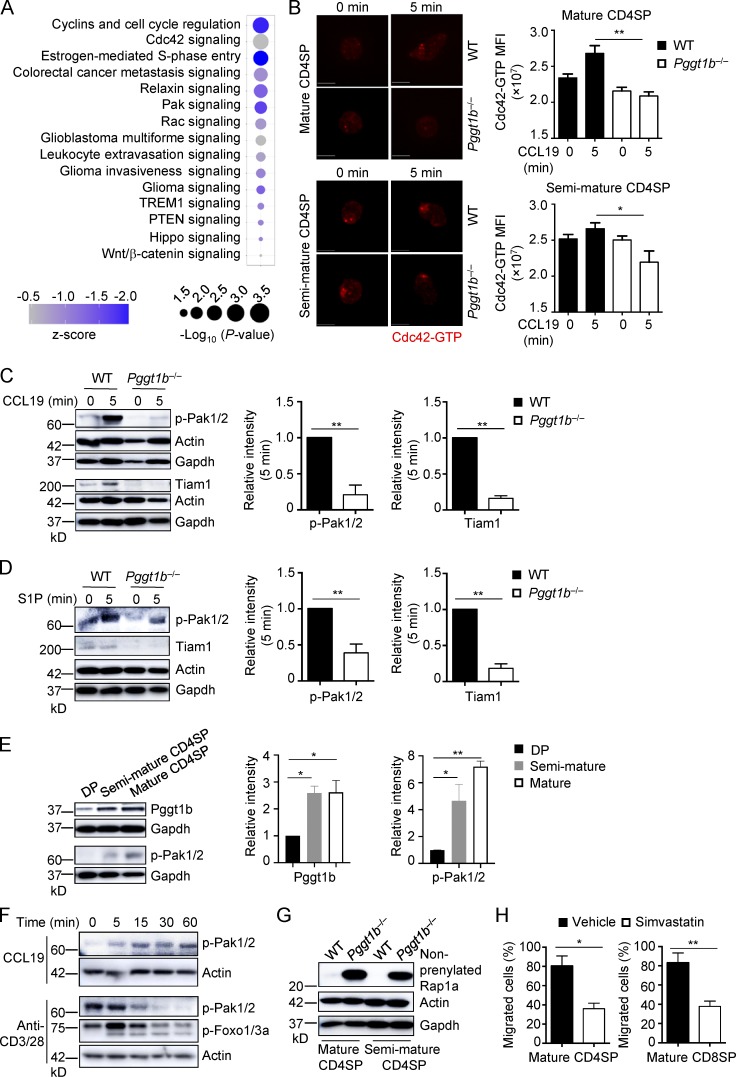

Pggt1b promotes Cdc42 and Pak signaling and Tiam1 expression

To systemically understand the molecular mechanisms underlying defective thymocyte egress in Pggt1b−/− mice, we performed transcriptome analysis of purified CD4SP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. A total of 509 genes were up- or down-regulated, with >0.5 log2 fold change, by Pggt1b deficiency (data not shown). We next used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis to identify canonical pathways controlled by Pggt1b in CD4SP thymocytes. Among the top 15 pathways down-regulated by Pggt1b deficiency (P < 0.05) included Cdc42, Pak, Rac, and Hippo signaling (Fig. 3 A), all of which are involved in cellular trafficking (Guo et al., 2011; Faroudi et al., 2010; Mou et al., 2012; Phee et al., 2014). Imaging analysis revealed reduced Cdc42-GTP signaling in CCL19-stimulated Pggt1b−/− CD4SP thymocytes compared with WT controls (Fig. 3 B), indicating impaired Cdc42 activity in these cells. Also, upon stimulation with CCL19 (Figs. 3 C and S3 A) or S1P (Fig. 3 D), Pggt1b−/− CD4SP thymocytes had decreased phosphorylation of Pak1/2 (p-Pak1/2), which are downstream effectors of the Rho family GTPases Cdc42 and Rac (Radu et al., 2014). Therefore, Pggt1b is important for the activation of the small G protein Cdc42 and downstream Pak signaling in thymocytes.

Figure 3.

Pggt1b integrates Cdc42, Pak signaling, and lipid metabolism in thymocyte trafficking, and its expression is up-regulated during thymocyte maturation. (A) Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of differentially expressed genes between WT and Pggt1b-deficient CD4SP cells identified in microarray assay. The top 15 down-regulated (z-score < 0) pathways are shown. (B) Representative immunofluorescent images (left) and MFI (right) of Cdc42-GTP expression in mature (top) and semimature (bottom) CD4SP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice after stimulation with CCL19 for 5 min. Scale bar, 5 μm. (C) Immunoblot analysis (left) and quantifications (right; after normalization to actin) of p-Pak1/2 and Tiam1 expression in mature CD4SP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice upon CCL19 stimulation. (D) Immunoblot analysis (left) and quantifications (right; after normalization to actin) of p-Pak1/2 and Tiam1 expression in mature CD4SP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice upon S1P stimulation. (E) Immunoblot analysis (left) and quantifications (right) of Pggt1b and p-Pak1/2 expression in different thymic T cell populations of WT mice. (F) Immunoblot analysis of p-Pak1/2 or p-Foxo1/3a expression in mature CD4SP thymocytes from WT mice upon CCL19 or anti-CD3/28 stimulation. (G) Immunoblot analysis of nonprenylated Rap1a expression in mature and semimature CD4SP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice. (H) Chemotactic response of mature CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes from WT mice pretreated with simvastatin or vehicle for 5 d. Migration through 5-µm transwells in response to CCL19 was assessed by flow cytometry. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA in B and E and two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test in C, D, and H. Data are from two (B and E–H) or three (C and D) independent experiments.

Next, we explored the mechanisms that link Pggt1b to small G protein signaling. We found that Tiam1, an upstream guanine nucleotide exchange factor of small G proteins (Boissier and Huynh-Do, 2014), was significantly reduced in Pggt1b−/− CD4SP thymocytes upon stimulation with CCL19 (Figs. 3 C and S3 A) or S1P (Fig. 3 D). Moreover, phosphorylation of Mob1, a conventional target of Hippo/Mst signaling that is implicated in small G protein activation (Mou et al., 2012), was reduced in Pggt1b-deficient cells stimulated with CCL19 (Fig. S3 B). Collectively, Pggt1b is required for Tiam1 expression and Hippo signaling, in line with a role in shaping T cell trafficking and Cdc42 activity.

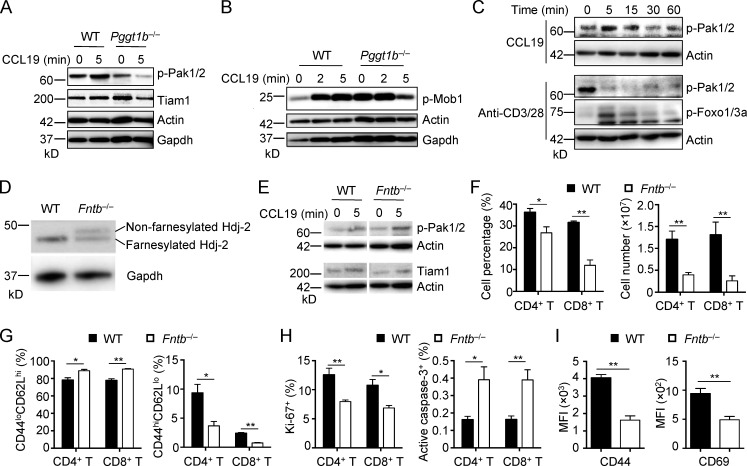

Figure S3.

Signaling events in Pggt1b−/− thymocyte and homeostasis of Fntb−/− mice. (A) Immunoblot analysis of p-Pak1/2 and Tiam1 in semimature CD4SP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice upon CCL19 stimulation. (B) Immunoblot analysis of p-Mob1 in mature CD4SP thymocytes from WT and Pggt1b−/− mice upon CCL19 stimulation. (C) Immunoblot analysis of p-Pak1/2 or p-Foxo1/3a in semimature CD4SP thymocytes from WT mice upon CCL19 or anti-CD3/28 stimulation. (D) Immunoblot analysis of Hdj-2 in mature CD4SP thymocytes from WT and Fntb−/− mice. (E) Immunoblot analysis of p-Pak1/2 and Tiam1 in mature CD4SP thymocytes from WT and Fntb−/− mice upon CCL19 stimulation. (F) Frequencies (left) and numbers (right) of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells in PLN of WT and Fntb−/− mice. (G) Frequencies of CD44loCD62Lhi naive (left) and CD44hiCD62Llo effector/memory (right) cells in CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from PLNs of WT and Fntb−/− mice. (H) Frequencies of Ki-67+ (left) and active caspase-3+ (right) cells in CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from PLNs of WT and Fntb−/− mice. (I) Expression of CD44 and CD69, as indicated by MFI, on WT and Fntb−/− naive CD4+ T cells upon overnight stimulation with plate-bound anti-CD3/28 (n = 9 per genotype). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test in F–I. Data are from two (A–D) or four (F–H) independent experiments.

Context-dependent regulation of Pggt1b function and protein geranylgeranylation

The key roles of Pggt1b in thymocyte trafficking prompted us to investigate the upstream signals involved in this process. We first examined Pggt1b expression in different thymic populations from WT mice. Pggt1b protein expression was increased in SP thymocytes compared with DP thymocytes (Fig. 3 E). Consistent with this observation, p-Pak1/2 were also greatly up-regulated in SP thymocytes (Fig. 3 E). Additionally, p-Pak1/2 were induced in SP thymocytes after treatment with CCL19, but not by TCR stimulation, while p-Foxo1/3a were upregulated by TCR stimulation (Figs. 3 F and S3 C). Thus, accompanying thymocyte maturation, Pggt1b expression and downstream Pak signaling are up-regulated in SP thymocytes.

Consistent with the role of Pggt1b as a protein geranylgeranyltransferase (Wang and Casey, 2016; Palsuledesai and Distefano, 2015), Pggt1b deficiency blocked protein geranylgeranylation, as revealed by accumulation in Pggt1b−/− thymocytes of the nonprenylated Rap1a, an established downstream event of impaired protein geranylgeranylation (Khan et al., 2011; Fig. 3 G). Aside from the catalytic enzyme Pggt1b, protein geranylgeranylation also depends upon the availability of the cofactor geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, a metabolic intermediate derived from the mevalonate pathway (Wang and Casey, 2016; Palsuledesai and Distefano, 2015). To test whether the mevalonate pathway contributes to thymocyte trafficking, we treated mice with simvastatin, a specific inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutary-CoA reductase, which catalyzes the rate-limiting step of the mevalonate pathway (Wang and Casey, 2016). Thymocytes treated with simvastatin had impaired migration in response to CCL19 (Fig. 3 H), indicating a role of the mevalonate pathway in thymocyte trafficking.

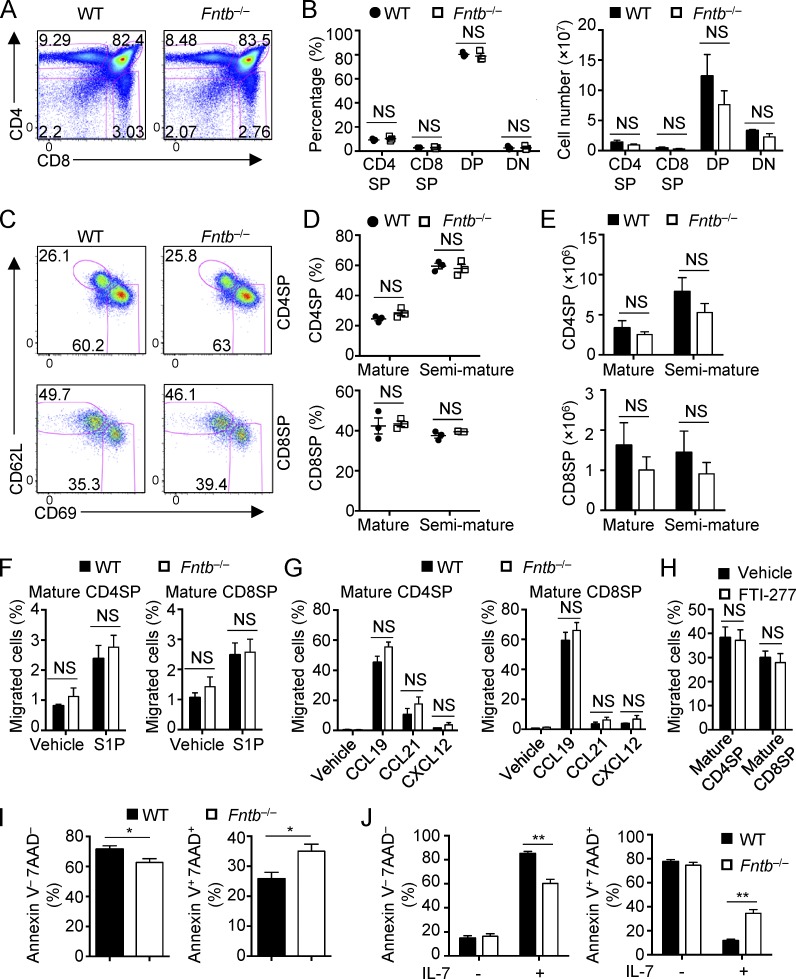

Fntb-mediated protein farnesylation is dispensable for thymocyte egress but contributes to peripheral T cell homeostasis

As protein geranylgeranylation and farnesylation orchestrate similar biochemical processes (Palsuledesai and Distefano, 2015; Wang and Casey, 2016), we examined whether protein farnesylation also regulates thymocyte egress. To this end, we generated mice with T cell–specific deficiency of Fntb (Fntb−/−) by crossing loxP-flanked Fntb alleles (Fntbfl/fl; Liu et al., 2010) with CD4-Cre transgenic mice. We confirmed that Fntb deficiency impaired protein farnesylation, as revealed by reduced electrophoretic mobility of Hdj-2 (a known farnesylation substrate) in Fntb-deficient thymocytes (Fig. S3 D). We then analyzed thymocyte populations in Fntb−/− mice by flow cytometry. To our surprise, Fntb deficiency did not disturb the percentages or numbers of CD4SP, CD8SP, DP, and DN cells in the thymus (Fig. 4, A and B). Furthermore, the percentages and numbers of CD62LhiCD69lo mature CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes were comparable between WT and Fntb−/− mice (Fig. 4, C–E). To directly access the migration ability of Fntb-deficient thymocytes, we performed in vitro chemotaxis assay. Fntb-deficient mature CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes showed normal in vitro migration toward S1P, CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL12 (Fig. 4, F and G). Moreover, the protein farnesylation inhibitor FTI-277 (Balaz et al., 2019) had no effect on WT thymocyte chemotaxis (Fig. 4 H). Finally, Pak1/2 phosphorylation and Tiam1 expression levels were comparable between WT and Fntb-deficient mature CD4SP cells (Fig. S3 E). Thus, Fntb is not required for thymocyte egress.

Figure 4.

Fntb-mediated protein farnesylation is not required for thymocyte egress but is critical for peripheral T cell homeostasis. (A and B) Flow cytometry analysis (A) and frequencies (B, left) and numbers (B, right) of thymic T cell populations in WT and Fntb−/− mice. (C–E) Flow cytometry analysis (C), frequencies (D), and numbers (E) of mature and semimature CD4SP (top) and CD8SP (bottom) thymocytes in WT and Fntb−/− mice. (F and G) Chemotactic response of mature CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes from WT and Fntb−/− mice. Migration through 5-µm transwells in response to S1P (F) or CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL12 (G) was assessed by flow cytometry after 3 h of treatment. (H) Chemotactic response of mature CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes from WT mice pretreated with vehicle or FTI-277 for 5 h. Migration through 5-µm transwells in response to CCL19 was assessed by flow cytometry after 2 h of treatment. (I) Frequencies of live Annexin V−7AAD− cells and apoptotic Annexin V+7AAD+ cells of WT and Fntb−/− naive CD4+ T cells after overnight stimulation with plate-bound anti-CD3/28 (n = 9 per genotype). (J) Frequencies of live Annexin V−7AAD− cells and apoptotic Annexin V+7AAD+ cells of WT and Fntb−/− naive CD4+ T cells after culture with or without IL-7 for 3 d (n = 6 per genotype). Numbers in gates indicate percentage of cells. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test in B and D–J. Data are from three (A–E, G, and H) or two (F) independent experiments.

In contrast to the normal thymocyte populations and trafficking, the percentages and numbers of PLN CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were reduced in Fntb−/− mice (Fig. S3 F). Peripheral T cells in Fntb−/− mice showed a less activated phenotype, as indicated by the increase of CD44loCD62Lhi naive cells and the corresponding reduction of CD44hiCD62Llo effector/memory cells (Fig. S3 G). Additionally, Fntb-deficient T cells showed decreased expression of the proliferative marker Ki-67 (Fig. S3 H) but increased expression of apoptotic maker active caspase-3 (Fig. S3 H). We then further verified these observations by in vitro studies. Fntb-deficient T cells had impaired TCR-induced events, as indicated by reduced expression of activation markers CD44 and CD69 (Fig. S3 I). In addition, the survival of Fntb-deficient T cells was compromised after stimulation with TCR (Fig. 4 I) or the homeostatic cytokine IL-7 (Fig. 4 J). Collectively, Fntb-mediated protein farnesylation is dispensable for thymocyte egress but contributes to peripheral T cell homeostasis, highlighting context-dependent effects of prenylation pathway in T cells.

Concluding remarks

Although Pggt1b- and Fntb-mediated protein prenylation has important roles in certain physiological systems (Liu et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2010), the function of this pathway in T cell biology is unknown. Moreover, Pggt1b and Fntb play a similar role in promoting tumor growth (Liu et al., 2010), but context-specific requirement and regulation remain poorly understood. Here, we investigate the physiological function of protein prenylation in T cells using genetic models with T cell–specific deletion of Pggt1b and Fntb. Our findings reveal an obligatory role of Pggt1b-mediated protein geranylgeranylation in thymocyte egress and trafficking. Deficiency of Pggt1b results in a profound lymphopenia in the peripheral lymphoid organs, associated with disrupted thymocyte egress but not loss of cell proliferative fitness or survival in the periphery. Accordingly, Pggt1b expression and the activation of downstream Pak signaling are up-regulated during thymocyte maturation and upon chemokine stimulation. In contrast to Pggt1b, Fntb-mediated protein farnesylation is not required in this process but contributes to T cell homeostasis in the periphery and to responses to TCR and IL-7 signals. Thus, our studies identify a previously unappreciated signaling requirement for thymocyte egress and highlight context-dependent function and regulation of protein geranylgeranylation and farnesylation.

It is well appreciated that the chemokines, S1P, and their receptors direct thymocyte migration within and out of the thymus (Lancaster et al., 2018; Cyster and Schwab, 2012). However, the pathways downstream of chemokine receptors, especially those integrating thymocyte migratory signals, remain poorly understood. In this report, we find that Pggt1b-deficient thymocytes are impaired in the migration toward both S1P and chemokines, including CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL12. Impaired trafficking is associated with defective activation of Cdc42 and other trafficking-associated pathways. These observations suggest that Pggt1b-mediated protein geranylgeranylation integrates S1P1 and chemokine receptor signals to promote thymocyte trafficking and egress. Cellular metabolism has emerged as a fundamental requirement of multiple T cell biological processes (Buck et al., 2017; Geltink et al., 2018). However, despite our emphasis on the role of signaling pathways in the control of metabolic activities, there is little evidence of whether and how metabolic intermediates can signal (Wellen and Thompson, 2012). Our studies reveal a link between the mevalonate pathway, the posttranslational protein modification geranylgeranylation, and thymocyte egress. Further investigation of the reciprocal interplay between cell signaling and immunometabolism will advance our understanding of T cell biology and may manifest therapeutic opportunities for immune-mediated disorders.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6, CD45.1+, and Rag1−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. CD4-Cre, Pggt1bfl, Fntbfl, and S1pr1-Tg mice were described previously (Liu et al., 2009, 2010; Lee et al., 2001; Sjogren et al., 2007). All mice have been backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background, and littermate mice were used as controls. For mixed BM chimera generation, BM cells from CD45.2+ WT or Pggt1b−/− mice were mixed with cells from CD45.1+ mice at a 1:1 ratio and transferred into sublethally irradiated (5.5 Gy) Rag1−/− mice, followed by reconstitution for 6–8 wk. For simvastatin treatment, mice were given simvastatin (40 mg/kg) by i.p. injection daily for 5 consecutive days and analyzed at day 6. All mice were housed in a specific pathogen–free facility in the Animal Resource Center at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Flow cytometry and cell purification

Lymphocytes were isolated from the thymus, spleen, PLNs, MLNs, and blood. For analysis of surface markers, cells were stained in PBS containing 2% BSA with appropriate surface antibodies: anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-CCR7 (4B12), anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD8a (53–6.7), anti-CD24 (M1/69), anti-CD25 (PC61.5), anti-CD44 (1M7), anti-CD45.1 (A20), anti-CD45.2 (104), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), anti-CD69 (H1.2F3), anti-Qa2 (69H1-9-9), anti-TCRβ (H57-597), anti-integrin β7 (FIB504; all from eBioscience), and anti-S1P1 (713412; R&D Systems). For analysis of intracellular Ki-67 expression, Foxp3 fixation/permeabilization buffers were used per manufacturer’s instructions (00-5523-00; ThermoFisher). Active caspase-3 staining was performed per the manufacturer’s instructions (550914; BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data were acquired on LSRII or LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). DP (CD4+CD8+), CD4SP (CD4+CD8−TCRβ+), mature CD4SP (CD4+CD8–TCRβ+CD62LhiCD69lo), and semimature CD4SP (CD4+CD8–TCRβ+CD62LloCD69hi) thymocytes and naive CD4+ T cells (CD4+CD25−CD44loCD62Lhi) were sorted using a MoFlow (Beckman-Coulter) or Reflection (i-Cyt).

Anti-CD4 PE labeling of egressing thymocytes

Anti-CD4 PE labeling of egressing thymocytes was performed as previously described (Willinger et al., 2014; Zachariah and Cyster, 2010). Briefly, mixed BM chimeras were injected i.v. with 1 µg PE-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody (clone GK1.5; BD Biosciences), and then thymocytes were harvested 4 min after injection and stained for flow cytometry analysis. Egressing CD4SP thymocytes were gated as CD4-PE+CD8− cells.

Chemotaxis assays

Thymocyte chemotaxis assays were performed as previously described (Dong et al., 2009). Briefly, 106 SP thymocytes in 100 µl media were loaded into the upper chamber of a transwell insert (3421; Corning) and allowed to transmigrate into the lower chamber containing 200 ng/ml CCL19 (Peprotech), 200 ng/ml CCL21 (Peprotech), 200 ng/ml CXCL12 (Peprotech), or 10 nM S1P (Sigma) for 3 h. When SP thymocytes treated with GGTI-298 or FTI-277 were used, the cells were washed extensively after 5 h of inhibitor treatment, and then chemotaxis assay was performed for 2 h to avoid extended in vitro culture that may lead to cell death. The input cells and the cells that migrated to the lower chamber were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD62L, anti-CD69, and anti-TCRβ antibodies for flow cytometry analysis. Cell number was counted using CountBright Absolute Counting Beads (C36950; ThermoFisher).

In vitro T cell cultures

Sorted naive CD4+ T cells were used for in vitro cultures in Click’s medium supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. For T cell activation, naive T cells were activated with plate-bound 5 µg/ml anti-CD3 (2C11) and 5 µg/ml anti-CD28 (37.51) in the presence of 100 U/ml IL-2 (R&D Systems) for 18 h and analyzed by flow cytometry for activation and apoptotic markers. For T cell survival in response to IL-7, naive T cells were cultured with or without 2 ng/ml IL-7 (R&D Systems) for 3 d and analyzed by flow cytometry.

RNA and immunoblot analyses

Real-time PCR analysis was performed as previously described with probe sets from Applied Biosystems (Du et al., 2018). Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously (Du et al., 2018) using the following antibodies: p-Foxo1 (Thr24)/Foxo3a (Thr32; 9464), p-Mob1 (Thr35; D2F10), p-Pak1 (Thr423)/2(Thr402; 2601), β-tubulin (9F3), and β-actin (8H10D10; all from Cell Signaling Technology), Pggt1b (5E4; Sigma), Tiam1 (AF-5038, R&D Systems), Rap1a (SC-1482; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Gapdh (1E6D9; Proteintech), and Hdj-2 (KA2A5.6; Lab Vision).

Histological analysis and fluorescence microscopy

For immunofluorescence staining of LN sections, LNs were isolated and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, 0.1% Triton-100, and 1% DMSO for 24 h before cryoprotection with 30% sucrose in PBS for an additional 24 h. Tissues were cryosectioned at 10 µm thickness and blocked in buffer composed of PBS containing 2% BSA and 5% donkey serum. Tissues were stained overnight in blocking buffer containing AF488-conjugated B220 (clone RA3-6B2; BioLegend), and AF594-conjugated CD3 (clone 17A2; BioLegend). Sections were washed in PBS and mounted with prolong glass hardset mounting medium (ThermoFisher). High-resolution images were acquired using a Marianis spinning disk confocal microscope (Intelligent Imaging Innovations) equipped with a 40× 1.3-NA objective; 405-nm, 488-nm, 561-nm, and 647-nm laser lines and a Prime 95B CMOS camera (Photometrics); and analyzed using Slidebook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). For immunofluorescence staining of thymus, freshly frozen thymi were cryosectioned and stained as outlined above using biotinylated UEA-1 lectin (Vector Labs). Sections were washed in PBS before incubation with AF568-conjugated streptavidin (ThermoFisher) and 10 nM DAPI. Samples were mounted with prolong glass hardset medium and imaged using confocal microscopy as outlined above.

For immunofluorescence staining of thymocytes, mature and semimature CD4SP thymocytes were rested in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 0.1% fatty acid–free BSA (Sigma) for 2 h at 37°C. Medium alone or medium containing 1 µg/ml CCL19 chemokine (final concentration) was added and cells were stimulated for 5 min. Cells were then analyzed following fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilization with 0.1% Triton-100, and incubation with mouse anti-Cdc42 (26905; NewEast Bioscience) diluted at 1:400 in PBS containing 2% BSA and 5% donkey serum. Cells were washed and incubated with donkey anti-mouse CF568-conjugated secondary antibody (Biotium) and AF499-conjugated phalloidin (for staining actin; ThermoFisher). Cells were imaged using a 1.4-NA 100× objective and confocal microscope outlined above and analyzed using Slidebook software. Shape factor index was used as a measure of polarization, where the ratio of the longest axis to the shortest axis having a value >1 would indicate elongation and actin polarization.

Gene expression profiling and bioinformatic analysis

CD4SP thymocytes (n = 4 per genotype) were isolated from the thymus of WT and Pggt1b−/− mice as described above. RNA was obtained with an RNeasy Micro Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). RNA samples were then analyzed with the Affymetrix Mouse Gene 2.0 ST array. Differentially expressed transcripts were identified by ANOVA (Partek Genomics Suite version 6.5), and the Benjamini-Hochberg method was used to estimate the false discovery rate. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of canonical pathways from these microarray samples was performed as previously described (Shrestha et al., 2014). Microarray data are available via the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession no. GSE135301.

Statistical analysis

P values were calculated by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism, unless otherwise noted. P < 0.05 was considered significant. All error bars represent the SEM.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 provides information on Pggt1b deletion efficiency, peripheral T cell homeostasis (including T cell activation, proliferation, apoptosis, and cytokine production), SP thymocyte maturation marker expression of Pggt1b−/− mice, and the strategy used to generate mixed BM chimeras. Fig. S2 shows proliferation and apoptosis of Pggt1b−/− SP thymocytes and DP thymocyte maturation of Pggt1b−/− mice, validation of the method for anti-CD4 PE labeling of egressing thymocytes, thymic T cell population analysis of S1pr1-Tg; Pggt1b−/− mice, the semimature SP thymocyte migration assay, and S1P1 and CCR7 expression in Pggt1b−/− SP thymocytes. Fig. S3 shows the immunoblot analysis of p-Pak1/2, Tiam1, and p-Mob1 expression in Pggt1b−/− mice, p-Pak1/2 and p-Foxo1/3a induction in WT thymocytes, Hdj-2 farnesylation, p-Pak1/2 and Tiam1 expression in Fntb−/− mice, and T cell homeostasis in Fntb−/− mice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Y. Feng for reagents and scientific discussions; N. Chapman and Y. Wang for critical reading of the manuscript; M. Hendren, A. KC, and S. Rankin for animal colony maintenance and technical assistance, and the Immunology FACS core facility for cell sorting.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI105887, AI131703, AI140761, AI150514, CA221290, and NS064599 (to H. Chi).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: X. Du designed, performed, and analyzed in vitro and in vivo experiments and wrote the manuscript; H. Zeng contributed to flow cytometry analysis; S. Liu contributed to biochemical experiments and flow cytometry analysis; C. Guy performed the imaging assay; Y. Dhungana and G. Neale performed bioinformatic analyses; M.O. Bergo provided critical reagents and scientific insights; and H. Chi designed experiments, wrote the manuscript, and provided overall direction.

References

- Akula M.K., Shi M., Jiang Z., Foster C.E., Miao D., Li A.S., Zhang X., Gavin R.M., Forde S.D., Germain G., et al. . 2016. Control of the innate immune response by the mevalonate pathway. Nat. Immunol. 17:922–929. 10.1038/ni.3487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeyens A., Fang V., Chen C., and Schwab S.R.. 2015. Exit Strategies: S1P Signaling and T Cell Migration. Trends Immunol. 36:778–787. 10.1016/j.it.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaz M., Becker A.S., Balazova L., Straub L., Müller J., Gashi G., Maushart C.I., Sun W., Dong H., Moser C., et al. . 2019. Inhibition of Mevalonate Pathway Prevents Adipocyte Browning in Mice and Men by Affecting Protein Prenylation. Cell Metab. 29:901–916.e8. 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissier P., and Huynh-Do U.. 2014. The guanine nucleotide exchange factor Tiam1: a Janus-faced molecule in cellular signaling. Cell. Signal. 26:483–491. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck M.D., Sowell R.T., Kaech S.M., and Pearce E.L.. 2017. Metabolic Instruction of Immunity. Cell. 169:570–586. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson C.M., Endrizzi B.T., Wu J., Ding X., Weinreich M.A., Walsh E.R., Wani M.A., Lingrel J.B., Hogquist K.A., and Jameson S.C.. 2006. Kruppel-like factor 2 regulates thymocyte and T-cell migration. Nature. 442:299–302. 10.1038/nature04882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyster J.G., and Schwab S.R.. 2012. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30:69–94. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y., Du X., Ye J., Han M., Xu T., Zhuang Y., and Tao W.. 2009. A cell-intrinsic role for Mst1 in regulating thymocyte egress. J. Immunol. 183:3865–3872. 10.4049/jimmunol.0900678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drennan M.B., Elewaut D., and Hogquist K.A.. 2009. Thymic emigration: sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1-dependent models and beyond. Eur. J. Immunol. 39:925–930. 10.1002/eji.200838912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X., Wen J., Wang Y., Karmaus P.W.F., Khatamian A., Tan H., Li Y., Guy C., Nguyen T.M., Dhungana Y., et al. . 2018. Hippo/Mst signalling couples metabolic state and immune function of CD8α+ dendritic cells. Nature. 558:141–145. 10.1038/s41586-018-0177-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupré L., Houmadi R., Tang C., and Rey-Barroso J.. 2015. T lymphocyte migration: An action movie starring the actin and associated actors. Front. Immunol. 6:586 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faroudi M., Hons M., Zachacz A., Dumont C., Lyck R., Stein J.V., and Tybulewicz V.L.J.. 2010. Critical roles for Rac GTPases in T-cell migration to and within lymph nodes. Blood. 116:5536–5547. 10.1182/blood-2010-08-299438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geltink R.I.K., Kyle R.L., and Pearce E.L.. 2018. Unraveling the Complex Interplay Between T Cell Metabolism and Function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 36:461–488. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F., Zhang S., Tripathi P., Mattner J., Phelan J., Sproles A., Mo J., Wills-Karp M., Grimes H.L., Hildeman D., and Zheng Y.. 2011. Distinct roles of Cdc42 in thymopoiesis and effector and memory T cell differentiation. PLoS One. 6:e18002 10.1371/journal.pone.0018002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James K.D., Jenkinson W.E., and Anderson G.. 2018. T-cell egress from the thymus: Should I stay or should I go? J. Leukoc. Biol. 104:275–284. 10.1002/JLB.1MR1217-496R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerdiles Y.M., Beisner D.R., Tinoco R., Dejean A.S., Castrillon D.H., DePinho R.A., and Hedrick S.M.. 2009. Foxo1 links homing and survival of naive T cells by regulating L-selectin, CCR7 and interleukin 7 receptor. Nat. Immunol. 10:176–184. 10.1038/ni.1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan O.M., Ibrahim M.X., Jonsson I.M., Karlsson C., Liu M., Sjogren A.K.M., Olofsson F.J., Brisslert M., Andersson S., Ohlsson C., et al. . 2011. Geranylgeranyltransferase type I (GGTase-I) deficiency hyperactivates macrophages and induces erosive arthritis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121:628–639. 10.1172/JCI43758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.V., Ouyang W., Liao W., Zhang M.Q., and Li M.O.. 2013. The transcription factor Foxo1 controls central-memory CD8+ T cell responses to infection. Immunity. 39:286–297. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurobe H., Liu C., Ueno T., Saito F., Ohigashi I., Seach N., Arakaki R., Hayashi Y., Kitagawa T., Lipp M., et al. . 2006. CCR7-dependent cortex-to-medulla migration of positively selected thymocytes is essential for establishing central tolerance. Immunity. 24:165–177. 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan J., and Killeen N.. 2004. CCR7 directs the migration of thymocytes into the thymic medulla. J. Immunol. 172:3999–4007. 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.3999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster J.N., Li Y., and Ehrlich L.I.R.. 2018. Chemokine-Mediated Choreography of Thymocyte Development and Selection. Trends Immunol. 39:86–98. 10.1016/j.it.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P.P., Fitzpatrick D.R., Beard C., Jessup H.K., Lehar S., Makar K.W., Pérez-Melgosa M., Sweetser M.T., Schlissel M.S., Nguyen S., et al. . 2001. A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity. 15:763–774. 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00227-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R., Chang S.Y., Trinh H., Tu Y., White A.C., Davies B.S.J., Bergo M.O., Fong L.G., Lowry W.E., and Young S.G.. 2010. Genetic studies on the functional relevance of the protein prenyltransferases in skin keratinocytes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19:1603–1617. 10.1093/hmg/ddq036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Burns S., Huang G., Boyd K., Proia R.L., Flavell R.A., and Chi H.. 2009. The receptor S1P1 overrides regulatory T cell-mediated immune suppression through Akt-mTOR. Nat. Immunol. 10:769–777. 10.1038/ni.1743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Sjogren A.-K.M., Karlsson C., Ibrahim M.X., Andersson K.M.E., Olofsson F.J., Wahlstrom A.M., Dalin M., Yu H., Chen Z., et al. . 2010. Targeting the protein prenyltransferases efficiently reduces tumor development in mice with K-RAS-induced lung cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:6471–6476. 10.1073/pnas.0908396107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloubian M., Lo C.G., Cinamon G., Lesneski M.J., Xu Y., Brinkmann V., Allende M.L., Proia R.L., and Cyster J.G.. 2004. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 427:355–360. 10.1038/nature02284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza A., Fang V., Chen C., Serasinghe M., Verma A., Muller J., Chaluvadi V.S., Dustin M.L., Hla T., Elemento O., et al. . 2017. Lymphatic endothelial S1P promotes mitochondrial function and survival in naive T cells. Nature. 546:158–161. 10.1038/nature22352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou F., Praskova M., Xia F., Van Buren D., Hock H., Avruch J., and Zhou D.. 2012. The Mst1 and Mst2 kinases control activation of rho family GTPases and thymic egress of mature thymocytes. J. Exp. Med. 209:741–759. 10.1084/jem.20111692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palsuledesai C.C., and Distefano M.D.. 2015. Protein prenylation: enzymes, therapeutics, and biotechnology applications. ACS Chem. Biol. 10:51–62. 10.1021/cb500791f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phee H., Au-Yeung B.B., Pryshchep O., O’Hagan K.L., Fairbairn S.G., Radu M., Kosoff R., Mollenauer M., Cheng D., Chernoff J., and Weiss A.. 2014. Pak2 is required for actin cytoskeleton remodeling, TCR signaling, and normal thymocyte development and maturation. eLife. 3:e02270 10.7554/eLife.02270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radu M., Semenova G., Kosoff R., and Chernoff J.. 2014. PAK signalling during the development and progression of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 14:13–25. 10.1038/nrc3645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley A.J., Schwartz M.A., Burridge K., Firtel R.A., Ginsberg M.H., Borisy G., Parsons J.T., and Horwitz A.R.. 2003. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 302:1704–1709. 10.1126/science.1092053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L.Z., Saravia J., Zeng H., Kalupahana N.S., Guy C.S., Neale G., and Chi H.. 2017. Gfi1-Foxo1 axis controls the fidelity of effector gene expression and developmental maturation of thymocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 114:E67–E74. 10.1073/pnas.1617669114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha S., Yang K., Wei J., Karmaus P.W.F., Neale G., and Chi H.. 2014. Tsc1 promotes the differentiation of memory CD8+ T cells via orchestrating the transcriptional and metabolic programs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:14858–14863. 10.1073/pnas.1404264111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjogren A.K.M., Andersson K.M.E., Liu M., Cutts B.A., Karlsson C., Wahlstrom A.M., Dalin M., Weinbaum C., Casey P.J., Tarkowski A., et al. . 2007. GGTase-I deficiency reduces tumor formation and improves survival in mice with K-RAS-induced lung cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 117:1294–1304. 10.1172/JCI30868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledzińska A., Hemmers S., Mair F., Gorka O., Ruland J., Fairbairn L., Nissler A., Müller W., Waisman A., Becher B., and Buch T.. 2013. TGF-β signalling is required for CD4+ T cell homeostasis but dispensable for regulatory T cell function. PLoS Biol. 11:e1001674 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno T., Saito F., Gray D.H.D., Kuse S., Hieshima K., Nakano H., Kakiuchi T., Lipp M., Boyd R.L., and Takahama Y.. 2004. CCR7 signals are essential for cortex-medulla migration of developing thymocytes. J. Exp. Med. 200:493–505. 10.1084/jem.20040643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., and Casey P.J.. 2016. Protein prenylation: unique fats make their mark on biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17:110–122. 10.1038/nrm.2015.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellen K.E., and Thompson C.B.. 2012. A two-way street: reciprocal regulation of metabolism and signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13:270–276. 10.1038/nrm3305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willinger T., Ferguson S.M., Pereira J.P., De Camilli P., and Flavell R.A.. 2014. Dynamin 2-dependent endocytosis is required for sustained S1PR1 signaling. J. Exp. Med. 211:685–700. 10.1084/jem.20131343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.H., Chang S.Y., Tu Y., Lawson G.W., Bergo M.O., Fong L.G., and Young S.G.. 2012. Severe hepatocellular disease in mice lacking one or both CaaX prenyltransferases. J. Lipid Res. 53:77–86. 10.1194/jlr.m021220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K., Blanco D.B., Chen X., Dash P., Neale G., Rosencrance C., Easton J., Chen W., Cheng C., Dhungana Y., et al. . 2018. Metabolic signaling directs the reciprocal lineage decisions of and T cells. Sci. Immunol. 3:eaas9818 10.1126/sciimmunol.aas9818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariah M.A., and Cyster J.G.. 2010. Neural crest-derived pericytes promote egress of mature thymocytes at the corticomedullary junction. Science. 328:1129–1135. 10.1126/science.1188222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Zhang X., Wang K., Xu X., Li M., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Hao J., Sun X., Chen Y., et al. . 2018. Newly Generated CD4 + T Cells Acquire Metabolic Quiescence after Thymic Egress. J. Immunol. 200:1064–1077. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]