Abstract

The Socialization of Emotion (Eisenberg et al., 1998a; 1998b) model creates a theoretical framework for understanding parents’ direct and indirect influences on children’s emotional development, including the influence of parent characteristics on subsequent emotion specific parenting. Large numbers of children live in families with fathers who have alcohol problems, setting the stage for cascading risk across development. For instance, fathers’ alcohol problems are a marker of risk for higher family conflict, increased parental depression and antisociality, and less sensitive parenting, leading to dysregulated child emotion and behavior. We examined a conceptual model for emotion socialization in a community sample of alcoholic and non-alcoholic father families (N = 227) recruited in infancy (i.e., 12 months) with follow-ups to adolescence (i.e., 15–19 years), and examined if hypothesized paths differed by child sex or group status (alcoholic vs. non-alcoholic families). Results indicated significant indirect effects between parent psychopathology and sensitivity in early childhood to both adaptive (e.g., emotion regulation) and maladaptive (e.g., aggression and peer delinquency) outcomes in middle childhood to adolescence via child negative emotionality and supportive emotion socialization. There were significant differences by child sex and alcohol group status. Implications for intervention and prevention are discussed.

Keywords: Emotion socialization, children of alcoholics, aggression, parenting, infancy, adolescence

Parent socialization of emotion in a high-risk sample

Developmental models emphasize the cascading influence of early experiences (e.g., negative parent-child interactions) for children’s social-emotional outcomes (Dodge et al., 2009; Raby, Roisman, Fraley, & Simpson, 2015), such as emotional and behavioral dysregulation. Parents influence their children’s emotional development through direct parent-child interactions that include specific responses to children’s negative emotions (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998a; Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Cumberland, 1998b), as well as indirectly through their own emotional functioning and parent-parent interactions in the home. Parent psychopathology, and paternal alcohol dependence specifically, is often associated with a breakdown in the family system and early parental socialization processes, and may set the stage for cascading negative processes across development. Understanding these cascading processes is critical for prevention and intervention as children of fathers with alcohol problems are at higher risk for aggression and engaging with delinquent peers (Eiden, 2018; Leonard & Eiden, 2007). The present study examines the Eisenberg and colleagues’ model of the Socialization of Emotion (SE; Eisenberg et al., 1998a; 1998b) in the context of fathers’ alcohol problems.

Paternal Alcohol Problems and Comorbid Risk

Approximately 10.5% of children ages 17 and younger live in a household with at least one parent with an alcohol use disorder (Lipari & Van Horn, 2017) and there is a robust literature on the negative outcomes for children of alcoholics, including higher risk for emotional and behavioral maladjustment such as aggression (Eiden, 2018; Finan, Schulz, Gordon, & McCauley Ohannessian, 2015). Fathers’ alcohol problems are often a marker for comorbid risks including higher antisocial behavior and depression symptoms in both parents (Eiden et al., 2016; Fitzgerald & Eiden, 2007; Hussong et al., 2007, 2008), which may not only have direct effects on children’s emotions, but also pose significant risk for parenting quality (Eiden, 2018) and child risk trajectories for problem behaviors (Goodman et al., 2011; Hussong et al., 2007, 2008). For example, parental depression has been found to be associated with harsh parenting (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000) and less effective emotional scaffolding (Hoffman, Crnic, & Baker, 2006). Parent depression may be a particularly significant predictor of children’s maladjustment during early development when parents are especially central in children’s lives (e.g., Goodman et al., 2011). Results from studies of risk trajectories across childhood indicate increases in risk for child behavior problems (reflecting poor behavioral regulation) when parent alcohol problems were comorbid with antisocial behavior or depression (Hussong et al., 2007, 2008). Studies have also noted prospective associations between co-occurring maternal depression and antisocial behavior with child psychopathology via lower maternal warmth and higher hostility (Sellers et al., 2014); associations between fathers’ antisocial behavior and increased risk for child behavior problems when fathers resided in the home (Jaffee, Moffitt, Caspi, & Taylor, 2003); and that parenting quality partially mediated the association between parent and child antisocial behavior across generations (Smith & Farrington, 2004).

Families with alcoholic fathers also report higher levels of partner conflict and aggression (Eiden, 2018). A number of developmental theories such as the ecological, relational and family systems theories (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Cox & Paley, 2003; Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000; Pruett, Pruett, Cowan, & Cowan, 2017) highlight intimate partner relationship quality as a significant influence on the parent-child relationship, child health, and development. Intimate partner relationship quality may impact children’s development either directly by providing social learning contexts (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961) or increasing child distress (Cummings, Pellegrini, Notarius, & Cummings, 1989), or indirectly by spilling over into parent-child interactions (Cox & Paley, 2003) or reducing parent’s emotional availability (Davies & Cummings, 1994). Parental stress, including marital dissatisfaction, has been found to negatively impact parent SE (Nelson, O’Brien, Blankson, Calkins, & Keane, 2009). Children exposed to interparental conflict may have heightened emotional insecurity and thus less capacity for emotion regulation and subsequently greater negative affect and lability (Davies & Cummings, 1994). Altogether, fathers’ alcohol problems create a high risk environment and may be a critical catalyst for a cascade of processes that increase risk for poor parenting and children’s maladaptive outcomes (e.g., Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2007).

Parent-Child Interactions and Socialization of Emotion

Children’s capacity to regulate emotions develops in the context of dyadic parent-infant interactions (Schore, 1994). Empirical evidence points to the critical protective role of maternal sensitivity in the infant toddler period as a proximal predictor of children’s emotional and behavioral regulation across development (Feldman, Dollberg, & Nadam, 2011). Previous work from the current sample has highlighted the role of fathers’ alcohol problems and associated risks in early infancy predicting lower maternal and paternal warmth and sensitivity in the toddler period (e.g., Eiden, Leonard, Hoyle, & Chavez, 2004). Taken together, this evidence indicates the enduring effects of parental warmth and sensitivity in early childhood and reflects continuity of supportive parenting (Eiden, 2018; Raby et al., 2015). Thus, parental sensitivity in early childhood may be predictive of parents’ supportive reactions to children’s negative experiences.

The SE model (Eisenberg et al., 1998a: 1998b) emphasizes the importance of parents’ reactions to children’s experiences with and expression of emotion. Direct SE that occurs within the context of child negative emotion may be especially critical for social and emotional competence (Eisenberg, Fabes, & Murphy, 1996a; Eisenberg et al., 1998a; 1998b). For example, parents may react non-supportively, such as responding to a child’s negative emotion with negative affect themselves or responding punitively, which can undermine learning about emotion management and increase negative arousal, emotional insecurity, and promote behavioral dysregulation (e.g., aggression; Carson & Parke, 1996; Davies & Cummings, 1994; Eisenberg et al., 1996a). Supportive parental reactions, on the other hand, may help children reduce their own arousal, learn effective coping strategies, and promote emotional security and regulation (Eisenberg et al., 1996a; Fabes, Leonard, Kupanoff, & Martin, 2001).

Parents’ capacity or ability to provide supportive reactions and positive parenting may be compromised by other parent characteristics, such as their mental health and partner relationship (Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007). Parental psychopathology and partner conflict not only impact parenting, but also may have a direct negative impact on children through social learning and creation of a negative emotional climate within the home (Morris et al., 2007). Parent alcohol problems have a cascading influence on many of the parent characteristics and family processes implicated in children’s emotional development. Emotion socialization may be particularly maladaptive in families with alcoholic or heavy drinking parents since parents may also be drinking to cope with negative emotions (e.g., Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995), that may be partially due to negative parent-child interactions (e.g., Pelham et al., 1998). However, there are no studies of emotion specific parenting and parent responses to child negative emotion within the context of fathers’ alcohol problems.

Middle Childhood to Adolescent Outcomes

Both emotion regulation and negative emotionality are key factors in the development of problem behavior (Eisenberg et al., 1996b; Eisenberg et al., 2001a). These skills play an especially important role in social relationships and ultimately social competence with peers (Carson & Parke, 1996). Emotion regulation is competency with emotion management and modulation processes and strategies (Eisenberg, Hofer, & Vaughan, 2007; Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, 2010), such as shifting attention away from distressing stimuli, cognitive reframing, or self-soothing (Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, & Rieser, 2000; Schwartz & Proctor, 2000). Negative emotionality is experiencing high levels of negativity in emotional expression and emotional lability (e.g., hostility, angry reactivity; Eisenberg et al., 2001a; Shields & Cicchetti, 1998). The common threads tying much of child and adolescent problem behavior together are negative affect and a lack of emotional and behavioral control (Eisenberg et al., 1996b). Conversely, more effective emotion regulation (i.e., responding to emotion in a socially appropriate and adaptive manner) and positive emotionality are associated with peer acceptance and competence (Carson & Parke, 1996; Eisenberg et al., 2000). Therefore, parent-child interactions and parenting specific to emotions may shape how children interact with their peers (see Parke, Cassidy, Burks, Carson, & Boyum, 1992) via the socialization of emotional displays and emotion management skills. Emotion and emotion management are important mechanisms through which parents influence their children’s social and emotional development (Parke et al., 1992), including behavioral problems such as aggression (Chang, Schwartz, Dodge, & Chang, 2003).

Within the SE model (Eisenberg et al., 1998a; 1998b), individual and contextual factors predict parent reactions to children’s negative emotions. For example, child characteristics such as dispositional emotionality, parenting and parent characteristics (e.g., parental warmth and sensitivity, psychopathology), and context (e.g., partner conflict) may influence parent SE, which subsequently influences child emotion regulation and social behavior (Eisenberg et al., 1998a; 1998b). Given the pervasive, negative consequences of fathers’ alcohol problems across each of the hypothesized factors, these risk and protective processes may be more salient predictors of adolescent problem behavior in alcoholic vs. non-alcoholic families.

Role of Fathers.

Fathers have an important role in child development and as social cultural context has been evolving, father involvement and family systems have also been changing. Less is known about the influence of fathers on emotion socialization, both independently and within the context of the co-parenting dyad, and the literature is mixed on the relative effects of mothers vs. fathers’ influence (e.g., Lytton & Romney, 1991). In parent-child relationships, mothers may be more socialized to provide warmth while fathers may be socialized to discipline, thus fathers may not only show less warmth but be more likely to respond in a non-supportive way to children’s negative emotions (Hosley & Montemayor, 1997). Indeed, Cassano, Perry-Parrish, and Zeman (2007) found fathers were more likely to respond to child sadness with non-supportive (i.e., minimizing) reactions. Mothers and fathers may thus have differential influences on their children’s emotional development (e.g., Carson & Parke, 1996; Eisenberg et al., 1996a), especially depending on the sex constellation of the parent-child dyads (e.g., father-daughter, father-son; Hart, Nelson, Robinson, Olsen, & McNeilly-Choque, 1998), and research based solely on maternal factors may not reflect the same processes that occur in father-child interactions (Stolz, Barber, & Olsen, 2005). For example, past research demonstrated that maternal parenting has a greater impact on child emotion regulation whereas paternal parenting has a greater impact on the development of child aggression (Chang et al., 2003). Prior results from the current sample have also demonstrated that associations between fathers’ alcohol problems and child effortful control (a critical component of self-regulation) may occur indirectly, via fathers’ warmth during father-infant interactions. Alcoholic fathers displayed lower warmth during father-infant play interactions and lower warmth was associated with lower effortful control, especially among boys. In contrast, maternal warmth accounted for unique variance in effortful control, with high maternal warmth associated with high effortful control regardless of fathers’ alcohol group status (Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2004).

Developmental Cascade and Timing.

Overall, parental expression of positive emotion with their children and sensitivity to child cues may have a protective and promotive impact on their children’s emotional development (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2001b). However, the timing of experiences with positive emotion and parenting may also be an important factor, as early relational experiences (i.e., infancy to early childhood) may have an especially enduring impact on adolescent and adult social-emotional functioning (Raby et al., 2015). The early parent-child relationship is thought to set the stage for later peer and romantic relationships and for general perceptions about relationships (e.g., internal working models, schemas, expectations; Bowlby, 1973; Raby et al., 2015; Sroufe, Carlson, Levy, & Egeland, 1999). For example, experiences with higher levels of warmth and sensitivity in the first years of life may be particularly protective and predict higher levels of social competence and lower levels of dysregulation and aggression into adulthood (Raby et al., 2015). In contrast, experiences with reduced warmth and sensitivity and parent psychopathology (e.g., maternal depression) early in life are more likely to lead to disrupted emotion regulation for children (Maughan, Cicchetti, Toth, & Rogosch, 2007; Morris et al., 2007). As such it is important to consider experiences during this early sensitive period in setting the stage for social and emotional development. The developmental cascade model also emphasizes the importance of early experiences and factors in setting into motion a cascade of effects and events that may lead to problem behavior in adolescence (Dodge et al., 2009). This model posits that early risk factors may influence a parent’s ability to parent effectively which leads to compounding emotional and behavioral problems for children as they move through middle childhood and adolescence (Dodge et al., 2009). For emotion socialization, early parent and child characteristics may influence a parent’s ability to respond supportively to children’s negative emotion, which may then impact children’s emotionality and emotion regulation and subsequent aggression and behavioral dysregulation (Eisenberg et al., 1998a).

Alcohol Problems as Moderator.

Diatheses stress or dual risk models are supportive of interactive effects of alcohol problems with antisocial behavior or depression on parenting and children’s negative emotions (Ingram & Luxton, 2005). Diathesis stress or dual risk models hypothesize that individuals with developmental vulnerability may be more adversely impacted by environmental risk (e.g., Roisman et al., 2012). Indeed, the developmental processes discussed above may be particularly problematic within alcoholic families as drinking may be exacerbated within the context of parental negative affect or in order to cope with negative emotion (Cooper et al., 1995). Parents with alcohol problems may socialize their children to have higher levels of negative emotionality, either directly through social learning processes (e.g., conflictual partner relationships and maladaptive coping strategies such as drinking) or via parenting. Thus, developmental pathways from parental psychopathology and negative family context to child outcomes via parents’ non-supportive emotion socialization may be particularly pronounced among father alcoholic compared to non-alcoholic families.

Child Sex as Moderator.

Sex differences may be particularly salient in the development of externalizing behavior (e.g., Bongers, Koot, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2004) and emotional expression (e.g., Chaplin, Cole, & Zahn-Waxler, 2005;for review see Grant et al., 2006). In particular, boys may be more likely develop externalizing symptoms in response to environmental stressors (Grant et al., 2006) and experience greater pressure to engage in persistent delinquent, antisocial behavior and interactions with deviant peers (Mears, Ploeger, & Warr, 1998; Moffitt & Caspi, 2001), especially when environmental stressors increase the risk for conflict within the family (Grant et al., 2006). Parent and family influences, including the influence of parental alcohol problems, could also differentially impact daughters versus sons (Finan et al., 2012). Past research has demonstrated the influence of the parent-child sex constellation on parenting and child social-emotional development (e.g., Carson & Parke, 1996; Chaplin et al., 2005; Eisenberg et al., 1996a). For example, paternal problematic drinking has been found to be associated with adolescent aggression and delinquent behavior indirectly via parent-child interactions and family cohesion; however, communication with fathers was particularly important for girls’ outcomes (Finan et al., 2012). Yet findings have been inconsistent regarding predicting adolescent externalizing outcomes when considering both child sex as well as parent and family risk and protective factors. Therefore, the role of sex on influencing parenting and child outcomes were explored.

Present Study

We examined a conceptual model for the development of social-emotional maladjustment in late adolescence integrating the Eisenberg et al. (1998a; 1998b) SE model within a developmental cascade framework from infancy to adolescence. Based on the theoretical models mentioned earlier, we included individual differences in child emotionality and emotion regulation, parent characteristics (i.e., parent depression, antisocial behavior), context (i.e., partner conflict) and parental warmth and sensitivity in early childhood as predictors of emotion specific parenting in early school age and child emotional and behavioral outcomes. We also examined the intermediary role of parenting specific to emotions at early school age on child negative emotionality and emotion regulation in middle childhood and aggression and behavioral dysregulation to late adolescence. Finally, we examined if specific paths from parent comorbid risks and parent warmth and sensitivity in early childhood to later outcomes differed for families with alcoholic vs. non-alcoholic fathers and explored variability in child sex. We hypothesized that the associations between early childhood risk to parent SE, and child social-emotional outcomes would be stronger under conditions of parents’ alcohol problems.

Method

Participants

Participants included 227 families recruited from birth records when their infants were 12 months of age (111 females, 116 males). Families were classified into one of two groups: the control group consisted of parents with no or few alcohol problems (n = 102), and the father alcoholic group consisted of families in which the father met diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence (n = 125). Of families in the alcoholic group, 95 mothers were abstainers or light drinkers, and 30 mothers were heavy drinkers or met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence (see Eiden et al., 2007 for procedural details and inclusion/exclusion criteria). The majority of both mothers (94%) and fathers (89%) were Caucasian, 5% of mothers and 7% of fathers were African American, and the remainder were Hispanic or Native American. Maternal age at recruitment ranged from 19–41 years (M = 30.7, SD = 4.5), while paternal age ranged from 21–58 years (M = 33.0, SD = 5.9). The majority of parents (59% of mothers and 54% of fathers) completed some post-secondary education or earned a college degree, and the average family income at time of recruitment was $41,824 (SD = $19,423). Biological parents were all residing together at recruitment, and 88% were married.

Procedures

Family assessments were conducted in the laboratory at 9 different child ages, including five assessments in early childhood (12, 18, 24, 36, and 48 months child age), one assessment at kindergarten (5–6 years child age), one assessment in middle childhood (4th grade, approximately 9–10 years child age), one assessment in early adolescence (8th grade, approximately 13–14 years of age), and one assessment in late adolescence (11th/12th grade, approximately 15–19 years of age). Mother-child and father-child assessments were conducted separately with a one to two week separation, standard consent procedures were followed, and procedures for the Buffalo Longitudinal Study were approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Early childhood.

Measures included in early childhood were collected between child ages of 12 and 48 months. Composites were created for early childhood variables to reflect experiences throughout this critical period and chronic exposure to parent maladjustment.

Parents ‘ alcohol use.

In addition to screening criteria, a self-report measure adapted from the University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Anthony, Warner, & Kessler, 1994; Kessler et al., 1994) was utilized to assess issues with parental alcohol abuse and dependence and both screening and diagnostic information was used to assign families to father alcoholic and control groups (see Eiden et al., 2007 for details).

Partner conflict.

Partner conflict was measured using a combination of both physical and verbal partner aggression. Physical aggression was measured using mothers’ and fathers’ self-reports on the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979), the maximum of mother and father reports were computed, and internal consistencies were adequate (Cronbach’s α = .82–86). Verbal aggression was assessed with a modified, 15-item version of the Index of Spouse Abuse scale (ISA; Hudson & McIntosh, 1981); only the verbal items from the ISA were utilized in the current study, with a composite measure created by averaging the total scores (Cronbach’s α =.88-.91). The physical and verbal aggression scales were significantly correlated at every time point (rs = .39 - .51,p < .001). Scores were subsequently standardized and then averaged across time to create a composite partner conflict score.

Depression.

Both maternal and paternal depression were measured at 4 time points (12, 24, 36, and 48 months child age) using self-reports of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CESD; Radloff, 1977). Scores were averaged across time for both mother (M = 7.54, SD = 6.06) and father (M = 6.94, SD = 5.67) separately, internal consistency ranged from α = .86 to .90 for mothers and α = .84 to .89 for fathers, and across time correlations ranged from .47 to .66 for mothers and .49 to .72 for fathers.

Parental warmth and sensitivity.

At the 12, 18, 24, and 36-month appointments, parents were asked to interact with their infants as they normally would at home for 5 minute period in a room filled with age appropriate toys. These interactions were coded at 12, 18, and 24 months using the Parent Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA; Clark, 1999; see Eiden et al., 2007, 2016 for details). The warmth/sensitivity subscale was used in the current study, and the internal consistency for this subscale ranged from Cronbach’s α = .90 to .93 for mothers’ and α = .90 to .95 for fathers. At 36 months, interactions were coding using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Melby et al., 1998), a global rating system designed to measure both verbal and non-verbal behaviors as well as affective aspects of the interaction (see Eiden et al., 2016 for details). The internal consistency for the warmth/sensitivity scale was Cronbach’s α = .89 for both mothers and fathers. Given the change in coding schemes, scores were standardized before being aggregated across time for both mothers and fathers. Two coders were trained on these scales by the second author until they achieved at least 80% reliability, were blind to group status, and random reliability checks were conducted on at least 15% of observations, with interrater reliability ranging from intraclass correlation coefficients of .80 to .97.

Child emotion regulation.

Child emotion regulation was assessed at both 18 and 24 months using the Behavior Rating Scale (BRS) of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development – II (BSID-II; Bayley, 1993). Examiners blind to group status administered the BSID-II and completed the BRS after test administration had been completed. The emotion regulation subscale was used in the current analyses, with higher scores indicating higher levels of emotion regulation. A composite emotion regulation score across time was computed by taking the mean of the 18 and 24 month scores (correlated at r = .34).

Antisocial behavior.

Mothers and fathers self-reported antisocial behavior was measured using a modified (28-item) version of the Antisocial Behavior Checklist (ASB; Ham, Zucker, & Fitzgerald, 1993; Zucker & Noll, 1980) at 12 months of child age (see Eiden et al., 2007, 2016 for further details). Given that the ASB is a measure of lifetime antisocial behavior, this measure was not administered at any subsequent time point. Internal consistency in the current sample was α = .82 for mothers and α= .90 for fathers.

Early school age.

Measures included in the early school age wave were collected during the child’s kindergarten year (child age M = 71.20 months, SD = 4.07).

Non-supportive and supportive reactions.

Parent responses to child negative emotion and distress were assessed with the parent-report measure Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES; Fabes, Eisenberg, & Bernzweig, 1990) at early school age. In this measure, parents report on how likely they are to respond with minimizing, punitive, distress, expressive encouragement, emotion-focused, or problem-focused reactions to their children expressing negative emotion on a scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely). Based on the procedures of Denham and Kochanoff (2002), means for reaction styles were calculated for non-supportive reactions (i.e., minimizing, punitive, distress reactions) and supportive reactions (i.e., expressive encouragement, emotion-focused, or problem-focused reactions) for both mothers and fathers. Both non-supportive (α = .84 for fathers, α = .78 for mothers) and supportive reactions (α = .91 for fathers, α = .93 for mothers) were internally consistent.

Middle childhood.

Measures included in the middle childhood wave were collected during the child’s 4th grade year.

Child negative emotionality/lability and emotion regulation.

Parents reported on their children’s behavioral display of emotion regulation using the Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields & Cicchetti, 1997), a 24-item questionnaire consisting of two subscales: negative emotionality/lability subscale (Cronbach’s α = .86) and the emotion regulation subscale (Cronbach’s α = .74). Maternal and paternal report of the subscales were averaged (r’s between parent reports were .39 for negative emotionality and .44 for emotion regulation).

Early and late adolescence.

Measures included in the early adolescent wave were collected during the child’s 8th grade year. Measures included in the late adolescent wave were collected during the child’s 11/12th grade year.

Peer delinquency.

Peer delinquency in both early and late adolescence was measured using an abbreviated version of the Adolescent Crime and Delinquency scale from the PhenX Toolkit (Hamilton et al., 2011). Internal consistency was good in both early (Cronbach’s α = .73) and late (Cronbach’s α = .87) adolescence waves.

Aggression and behavioral dysregulation.

Aggressive behavior and behavioral dysregulation in both early and late adolescence was measured using the aggressive behavior subscale of the Youth Self-Report (YSR: Achenbach, 1991), with acceptable reliability in both the early (Cronbach’s α = .77) and late (Cronbach’s α = .78) adolescence waves. For ease, this will be referred to as aggression although this construct reflects both aggression and behavioral dysregulation (e.g., arguing a lot).

Analytic Strategy

Prior to conducting any analyses, several phases of data cleaning were conducted following recommendations by Kline (Kline, 2016). Of the 227 families that provided data at the 12 month visit, 227 (100%) also provided data at 18 months, 222 (98%) provided data at 24 months, 205 (90%) provided data at 36 months, 182 (80%) provided data at 48 months, 187 (82%) provided data at Kindergarten, 159 (70%) provided data at 4th Grade, 162 (71%) provided data at 8th grade, and 184 (81%) at 11/12th grade. There were no group differences between families with missing versus complete data on analytic or demographic variables with the exception of paternal warmth and sensitivity (Ms = −0.39 and 0.03, SDs = 0.84 and 0.74, for those missing versus not missing data respectively), thus meeting criteria for missing at random (Little, 1988). Path analysis was used to test the conceptual model (see Figure 1) and was conducted using Mplus, Version 8 software (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2018) and full information maximum likelihood was used to estimate parameters to handle missing data (Arbuckle, 1996). Indirect effects were tested using the bias-corrected bootstrap method (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004), with 5,000 bootstrap samples and the 95% bias-corrected intervals (CIs) were used to test significance of indirect effects. Models were analyzed including both mothers and fathers, as past research has found that comparing the relative influences and differential effects is important (e.g., Stolz et al., 2005). Multiple group analyses testing specific paths were used to examine differences between alcoholic and non-alcoholic families and sex differences in hypothesized paths (e.g., from exogenous variables to child outcomes, cross-lagged paths and stability coefficients for child aggression and peer delinquency).

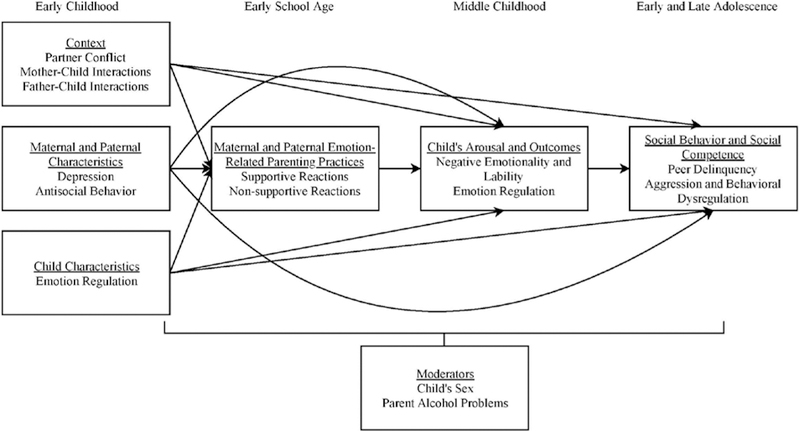

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model. Note: Framed within the Eisenberg and colleagues’ model of the Socialization of Emotion (Eisenberg et al., 1998a; 1998b)

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Group differences in the variables included in the model are presented in Table 1 and correlations among variables included in the model are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Mean differences by alcohol group status

| Control Group Mean (SD) |

Alcoholic Group Mean (SD) |

t | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paternal Depression | 6.07 (5.70) | 7.65 (5.56) | t(225) = −2.10, |

| p = .037 | |||

| Maternal Depression | 6.23 (5.18) | 8.62 (6.51) | t(225) = −3.01, |

| p = .003 | |||

| Paternal Warmth and Sensitivity | 0.05 (0.80) | −0.07 (0.73) | t(225) = 1.14, |

| n.s. | |||

| Maternal Warmth and Sensitivity | 0.13 (0.84) | −0.15 (0.74) | t(225) = 2.59, |

| p = .01 | |||

| Paternal Antisocial Behavior | 36.16 (6.34) | 42.68 (9.56) | t(225) = −5.92, |

| p < .001 | |||

| Maternal Antisocial Behavior | 34.27 (4.42) | 37.32 (5.85) | t(225) = −4.35, |

| p < .001 | |||

| Partner Conflict | −0.66 (1.59) | 0.65 (2.20) | t(225) = −4.99, |

| p < .001 | |||

| Emotion Regulation (Early Childhood) | 40.07 (5.09) | 39.75 (5.28) | t(225) = 0.46, |

| n.s. | |||

| Paternal Supportive Reactions | 15.73 (2.10) | 15.60 (1.93) | t(173) = 0.44, |

| n.s. | |||

| Maternal Supportive Reactions | 17.26 (1.88) | 17.03 (2.05) | t(183) = 0.76, |

| n.s. | |||

| Paternal Non-supportive Reactions | 8.79 (1.62) | 8.89 (1.76) | t(173) = −0.36, |

| n.s. | |||

| Maternal Non-supportive Reactions | 7.73 (1.47) | 7.98 (1.35) | t(183) = −1.21, |

| n.s. | |||

| Negative Emotionality and Lability (Middle Childhood) | 25.14 (4.71) | 26.30 (4.71) | t(177) = −1.62, |

| n.s. | |||

| Emotion Regulation (Middle Childhood) | 26.97 (2.87) | 26.75 (2.84) | t(177) = 0.53, |

| n.s. | |||

| Aggression and Behavioral Dysregulation (Early Adolescence) | 4.67 (3.54) | 5.51 (3.91) | t(159) = −1.41, |

| n.s. | |||

| Aggression and Behavioral Dysregulation (Late Adolescence) | 5.39 (3.81) | 6.23 (4.05) | t(180) = −0.92, |

| n.s. | |||

| Peer Delinquency (Early Adolescence) | 2.70 (2.61) | 3.92 (3.15) | t(159) = −2.62, |

| p = .01 | |||

| Peer Delinquency (Late Adolescence) | 2.78 (2.89) | 4.71 (5.47) | t(182) = −2.87, |

| p = .005 | |||

Note. Warmth and Sensitivity and partner conflict composite variables are standardized.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. | 18. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l.Paternal | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Depression | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2.Maternal | .21** | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Depression | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3.Paternal | −.07 | −.18** | X | |||||||||||||||

| Sensitivity | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4.Maternal | − 17** | −.15* | .50*** | X | ||||||||||||||

| Sensitivity | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5.Paternal | .30*** | 31*** | −.14* | −.16* | X | |||||||||||||

| Antisocial Beh. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 6.Maternal | .23** | .36*** | −.13+ | −.13+ | .44*** | X | ||||||||||||

| Antisocial Beh. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 7.Partner Conflict | 43*** | .43*** | − 31*** | −.30*** | .36*** | .40*** | X | |||||||||||

| 8.Emotion | −.02 | −.11+ | .29** | .33*** | .03 | −.05 | −.16* | X | ||||||||||

| Regulation EC | ||||||||||||||||||

| 9.Paternal | −.15* | −.04 | .11 | .21** | .07 | .14+ | −.06 | .06 | X | |||||||||

| Supportive Rea. | ||||||||||||||||||

| l0.Maternal | −.06 | −.22** | .16* | .23** | −.08 | −.05 | −.08 | .04 | .25** | X | ||||||||

| Supportive Rea. | ||||||||||||||||||

| ll.Paternal Non- | .11 | .11 | −.20** | −.27*** | −.08 | −.09 | .23** | .01 | −.31*** | −.18* | X | |||||||

| Supportive Rea. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 12.Maternal Non- | .08 | .06 | −.22** | −.09 | −.05 | −.09 | .07 | −.08 | −.16* | −.20** | .13+ | X | ||||||

| Supportive Rea. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 13.Negative | .31*** | 31*** | −.15* | −.18* | .23** | .12 | .36*** | −.22** | −.09 | −.06 | .16* | .08 | X | |||||

| Emotionality MC | ||||||||||||||||||

| 14.Emotion | −.14+ | −.21** | .25** | .21** | −.17* | −.02 | −.10 | .20** | .25** | .28*** | −.20* | −.05 | −.54*** | X | ||||

| Regulation MC | ||||||||||||||||||

| 15.Aggression EA | .03 | .09 | −.06 | −.07 | .16* | .06 | .17* | .01 | .04 | .04 | .08 | −.06 | .23** | −.02 | X | |||

| 16.Aggression LA | −.05 | .12 | −.02 | .01 | .03 | −.08 | .05 | .09 | −.00 | .02 | −.02 | .06 | .23** | −.04 | .57*** | X | ||

| 17.Peer | −.06 | −.01 | −.14+ | −.15+ | .11 | .06 | .14+ | .03 | −.02 | −.01 | .13 | −.06 | .11 | .06 | .42*** | .28*** | X | |

| Delinquency EA | ||||||||||||||||||

| 18.Peer | −.09 | .09 | −.07 | −.11 | .17* | .08 | .11 | −.00 | .14 | .18* | −.01 | −.16* | .05 | −.01 | .27** | .42*** | .45*** | X |

| Delinquency LA | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mean | 6.94 | 7.54 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 39.75 | 35.95 | 0.06 | 39.89 | 15.66 | 17.14 | 8.84 | 7.86 | 25.79 | 26.84 | 5.15 | 5.86 | 3.39 | 3.87 |

| SD | 5.67 | 6.06 | .76 | .80 | 8.87 | 5.46 | 2.05 | 5.19 | 2.01 | 1.96 | 1.70 | 1.41 | 4.73 | 2.85 | 3.77 | 3.96 | 2.99 | 4.63 |

Note.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001;

Warmth and Sensitivity and parent partner conflict composite variables are standardized. Beh: Behavior, Rea.: Reactions, EC: Early Childhood, MC: Middle Childhood, EA: Early Adolescence, LA: Late Adolescence.

Model Testing

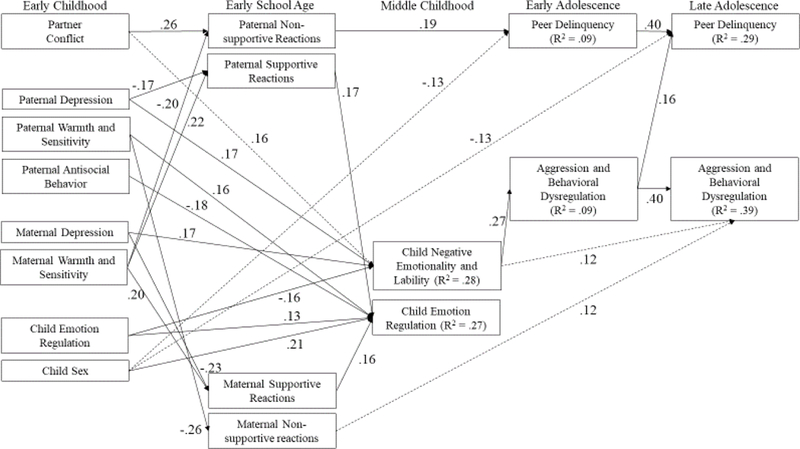

The analytic model included early childhood predictors (i.e., parent depression and antisocial behavior, partner conflict, parent warmth and sensitivity during parent–child interactions, parent alcohol problems, child emotion regulation during developmental testing, and child sex) as exogenous variables; causal paths from these variables to parent supportive and non-supportive reactions to child negative emotions at early school age, child negative emotionality and emotion regulation in middle childhood, and adolescent report of peer delinquency as well as aggression in early and late adolescence (see Figure 2). We also included paths from child negative emotionality and emotion regulation in middle childhood to peer delinquency and aggression at both adolescent time points, and the cross-lagged paths between peer delinquency and aggression in adolescence. The model included covariances between the exogenous variables.

Figure 2.

Path analysis model for the development of social-emotional maladjustment in late adolescence. Note: Non-significant paths and residuals are not depicted in the model for ease of presentation. The numbers are standardized path coefficients. Solid lines indicate paths that are p < .05 and dotted lines indicate paths that are p < .10. For child sex, male = 1 and female = 2. Maternal antisocial behavior was trimmed from models as it was not significantly associated with the endogenous variables. Maternal and paternal alcohol problems were included in the model but removed for ease of presentation as these variables were not significantly associated with the endogenous variables. Alcohol group status was associated with greater engagement with delinquent peers in early adolescence but is not depicted in the figure for ease of communication.

Overall Model.

Goodness of fit indices indicated that this hypothesized model fit the data well, χ2(64) = 93.06, p = .01, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .05, 95% CI [.02, .06]. Parents’ depressive symptoms in early childhood were prospectively predictive of higher negative emotionality in middle childhood. Higher paternal antisocial behavior in infancy predicted decreased child emotion regulation and paternal warmth and sensitivity was predictive of higher emotion regulation in middle childhood. Child sex predicted emotion regulation and tended to predict peer delinquency, such that girls had higher emotion regulation and boys tended to have higher levels of peer delinquency at both adolescent time points. There were no significant direct pathways from early childhood predictors to early or late adolescence aggression or involvement with delinquent peers. Neither maternal nor paternal alcohol problems were significantly associated with the endogenous variables. However, alcohol group status (i.e., alcoholic vs. nonalcoholic families) was associated with greater engagement with delinquent peers in early adolescence (β = .20, p = .009).

There was stability in emotion regulation from early to middle childhood. There was also stability in mothers’ parenting, with maternal warmth and sensitivity in early childhood predicting maternal supportive reactions at early school age. Interestingly, there were some cross-parent effects, particularly from observations of warmth and sensitivity in early childhood to emotion specific parenting at early school age. For example, mothers’ and fathers’ warmth and sensitivity predicted the other parent using less non-supportive reactions at early school age. Maternal warmth and sensitivity also predicted paternal supportive reactions. Partner conflict tended to predict higher child negative emotionality in middle childhood.

Both maternal and paternal supportive reactions to child negative emotion predicted higher child emotion regulation in middle childhood. Paternal non-supportive reactions predicted engagement with delinquent peers in early adolescence. Maternal non-supportive reactions tended to predict higher aggression in late adolescence. Higher negative emotionality predicted more aggression in early adolescence and tended to predict late adolescence aggression. Adolescent report of aggression in early adolescence predicted greater engagement with delinquent peers in late adolescence.

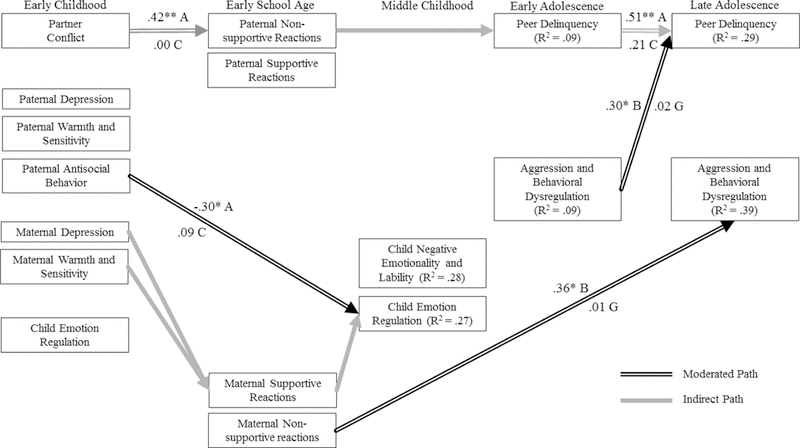

Indirect Effects.

Indirect pathways via parent emotion specific parenting were examined (see Figure 3). The indirect association between parent partner conflict and engaging with delinquent peers in early adolescence via paternal non-supportive reactions was significant, β = .08, 95% CI [.001, .26] as was the indirect pathway from parent conflict to late adolescent engagement with delinquent peers via paternal non-supportive reactions and early adolescent delinquent peer involvement, β = .05, 95% CI [.002, .20]. The indirect pathway from paternal depression during early childhood to child emotion regulation via paternal supportive reactions to child emotion was not significant, β = −.02, 95% CI [−.06, .001]. However, the associations from early childhood maternal warmth and sensitivity, β = .12, 95% CI [.02, .35], and maternal depression in early childhood, β = −.02, 95% CI [−.05, −.003] to child emotion regulation in middle childhood via maternal supportive reactions to child emotion were significant.

Figure 3.

Path analysis model with only moderated and indirect paths emphasized. Note: Moderated and indirect paths from Figure 2 emphasized; *p < .01, ** p < .001; A = Families with Alcoholic Fathers; C = Control Group; B = Boys; G = Girls.

Moderation by Paternal Alcohol Problems.

We used multiple group analyses (see Figure 3) to examine if the associations between the early childhood risk variables, SE variables, and child outcomes varied for alcoholic and non-alcoholic families. Hypothesized paths were each constrained and compared to the unconstrained parameter model. There were several hypothesized paths that did significantly differ across groups. The path from partner conflict in early childhood to paternal non-supportive reactions at early school age was significant for alcoholic fathers but not for fathers in the control group Δχ2 = 3.98, p = .046). Fathers’ antisocial behavior was also predictive of lower emotion regulation for children in the alcoholic families but not in the non-alcoholic families (Δχ2 = 4.90, p = .027). Further, results indicated greater stability in engagement with delinquent peers from early to late adolescence for children in alcoholic families compared to those from non-alcoholic families (Δχ2 = 6.52, p = .011).

Moderation by Child Sex.

Finally, we conducted multiple group analyses to determine if the stability or cross-lagged paths for peer delinquency and aggression differed for boys and girls. We also examined if the predictive paths from SE variables to adolescent outcomes differed for boys and girls. Hypothesized pathways were again each constrained and compared to the unconstrained model. Results indicated that aggression in early adolescence was predictive of engagement with delinquent peers in late adolescence for boys but not girls (Δχ2 = 4.93, p = .026). Further, maternal non-supportive reactions to child negative emotion was a significant prospective predictor of late adolescent aggression for boys but not girls (Δχ2 = 4.62, p = .026).

Discussion

We examined a conceptual model for the development of social-emotional maladjustment from infancy to late adolescence integrating a developmental cascade framework with the Eisenberg et al. (1998a; 1998b) SE model. In particular, we examined parent SE as a primary mechanism in the association between early childhood risks and development of aggression and behavioral dysregulation. We also assessed if these pathways were different for alcoholic vs. non-alcoholic families given potential interactive effects of alcohol problems and early childhood risk on children’s emotional development. In addition to the intermediary role of parenting specific to emotion, we examined early childhood predictors of emotion specific parenting in early school age and child emotional and behavioral outcomes from middle childhood to adolescence and if there were sex differences in specific hypothesized paths.

Results indicated that early experiences with parental depression may be especially impactful. Indeed, previous studies indicate that even when depression remits later in development, the consequences of early experiences with this parental psychopathology are enduring (Maughan et al., 2007). Parental depression in early childhood directly predicted children’s negative emotionality and lability in middle childhood. The current findings are consistent with past research suggesting an early childhood sensitive period during which exposure to parental, especially maternal, depression has an enduring impact (e.g., Goodman et al., 2011) and when parental depression and substance use problems are comorbid, depression has a more pronounced effect on child psychopathology (Luthar & Sexton, 2007). Depression may disrupt affective transactions between parent and child, as depressive symptoms could inhibit a parent’s ability to effectively manage, accurately interpret, as well as sensitively and predictably respond to child negative affect during the first few years of life (e.g., Goodman et al., 2011; Maughan et al., 2007) when warm and consistent care are particularly important (Raby et al., 2015). Indeed, early exposure to a parent’s disrupted, depressive emotional expression and less effective regulation may provide a socialization context for modeling and ultimately internalization of negative emotionality and dysregulated strategies (Bariola, Gullone, & Hughes, 2011). Conversely, lower levels of reported parental depression and maternal warmth and sensitivity in early childhood were predictive of having supportive reactions to child negative emotion at early school age. Parental depression accounted for unique variance in reactions to child negative emotion even with alcohol problems in the model. However, it is important to note that fathers’ depression occurred in the context of an alcohol disorder for fathers in the alcohol group, and may reflect the affective impact of heavy drinking and alcohol problems. In addition, few parents scored in the clinical range for depression. Thus, the associations with parent depression are even more noteworthy, and may be stronger in samples with higher numbers of clinically depressed parents (e.g., Luthar & Sexton, 2007).

Subsequently, negative emotionality was predictive of maladaptive social-emotional outcomes, such as aggression in early adolescence, whereas supportive reactions and positive parenting specific to emotion was predictive of adaptive social-emotional outcomes, such as greater emotion regulation for children in middle childhood. In addition, paternal supportive reactions to child negative emotion were also associated with more skilled child emotion regulation in middle childhood and maternal non-supportive reactions tended to predict late adolescent aggression. As past research has demonstrated that children may particularly rely on mothers for support and comfort over fathers (Lieberman, Doyle, & Markiewicz, 1999), nonsupportive responses from mothers in the context of a child’s negative emotion and potentially comfort-seeking may be especially impactful for children. Mothers are also more likely to be the primary caregivers, especially in the context of fathers’ alcohol problems. Partner conflict was indirectly predictive of engaging with delinquent peers in adolescence via paternal non-supportive reactions. These findings support the SE model (Eisenberg et al., 1998a; 1998b) that emphasizes the importance of parenting characteristics, such as parental depression and warmth and sensitivity, in predicting emotion specific parenting and the indirect, intermediary protective role of positive parenting in response to child negative emotion for later child adjustment. This finding is also consistent with past research suggesting that spillover from marital discord onto parent SE is especially impactful for fathers (Nelson et al., 2009). These results are similar to those reported in earlier waves of this study indicating stronger spillover effects of partner conflict on paternal warmth and sensitivity during father-child interactions compared to maternal warmth and sensitivity (Finger, Eiden, Edwards, Leonard, & Kachadourian, 2010). Therefore, fathers’ parenting abilities may be more dependent on the quality and satisfaction of their partner relationship than for mothers (Nelson et al., 2009). Fathers’ relationships and interactions with their children could also have a greater impact on adaptive peer skills, such as conflict resolution (Lieberman et al., 1999). The finding that child negative emotionality was predictive of adolescent maladjustment is also consistent with past work suggesting the underlying importance of children’s emotional expression in peer and social-emotional adjustment (Parke et al., 1992).

Although the pathways via maternal supportive reactions and paternal non-supportive reactions were the only significant indirect effects, several parent characteristics during early childhood also predicted emotion specific parenting. Interestingly, maternal warmth and sensitivity during early childhood was predictive of both paternal supportive reactions and reduced paternal non-supportive reactions to child negative emotion. Similarly, paternal warmth and sensitivity was associated with reduced maternal non-supportive reactions at early school age. However, results are not entirely consistent with the SE model (Eisenberg et al., 1998a; 1998b) as there was only an indirect pathway via parent SE to child adjustment in adolescence. In at risk contexts, considering the role of other caregivers, such as fathers, and the detrimental impact of fathers engaging in non-supportive emotion specific parenting may be important. Indeed, past research has suggested the negative impact of fathers’ involvement when they are not contributing positive influences to child development (Jaffee et al., 2003). These results also emphasize the importance of considering the co-parenting dyad and how parent characteristics may impact not only intraindividual parenting practices but also their co-parent’s behavior.

Impact of Fathers’ Alcohol Problems

Both mothers and fathers in alcohol problem families report higher depression and antisocial behavior (see Eiden, 2018). The association between paternal antisocial behavior in early childhood and lower child emotion regulation in middle childhood was moderated by fathers’ alcohol group status, as this association was significant for alcoholic families but not control families. These results are similar to those reported in previous studies of children of alcoholic fathers beginning in the preschool period (e.g., Loukas, Zucker, Fitzgerald, & Krull, 2003), with significant associations between paternal antisocial behavior within the context of alcohol problems and higher levels of child behavioral problems and regulatory deficits. Families with alcoholic fathers reported greater partner conflict across early childhood. Fathers’ alcohol problems also moderated the association between parent partner conflict in early childhood and fathers’ non-supportive reactions to child negative emotions. This prospective path was significant for fathers with alcohol problems but not for the control group fathers. This is consistent with past research suggesting the negative impact of heavy drinking on partner relationships and the potential spillover effect of marital or partner conflict to the parent-child relationship (Finger et al., 2010). Finally, there was greater stability in engagement with delinquent peers among children in alcoholic families compared to those in non-alcoholic families. Children of alcoholic fathers may be at particular risk due to their experiences with higher levels of conflict and parental antisocial behavior within the home for exacerbating deviant behavior that may contribute to involvement with delinquent peers and for creating schemas and normative beliefs about peer interactions that may lead them to choose peers that fit with these schemas (e.g., Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). Associations with delinquent peers may then reinforce or exacerbate risk taking or inappropriate social behavior (Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, 1991; Patterson et al., 1989).

Sex Differences

Consistent with past work suggesting differing rates and onset of antisocial behavior and involvement with delinquent peers for males and females (Mears et al., 1998; Moffitt & Caspi, 2001), child sex moderated the association between early adolescence aggression and late adolescence association with delinquent peers. This association was positive and significant for boys but not for girls. Boys and girls may differ in regards to risk factors for delinquent behavior and associating with deviant peers (e.g., Hubbard & Pratt, 2002). For boys, behaving in an aggressive and dysregulated manner in early adolescence may lead to associating with peers who are delinquent and deviant either by choice (Scarr & McCartney, 1983) or due to peer rejection limiting options for affiliation (e.g., Dishion et al., 1991). Further, the association between maternal non-supportive reactions and late adolescence aggression was significant for boys. Mothers may be more likely to use harsh parenting with their sons than with daughters (e.g., Barnett & Scaramella, 2013). These findings suggest the importance of both maternal and paternal influences on child outcomes as well as the sex-constellation of the parent-child relationship (e.g., Finan et al., 2015) on the impact of parenting and child outcomes.

Limitations and Future Research

The present study had many strengths, including longitudinal design from infancy to late adolescence and multi-method, multi-informant assessments of maternal, paternal, and child behavior. However, this study was not without limitations. One major limitation was sample size given the complexity of the model and multiple group analyses. It is difficult to have large samples and at the same time, include multi-method observational assessments of mothers and fathers in any one study. Future work may attain larger samples by aggregating across multiple studies with similar methods and then may be better able to examine if the hypothesized model differed for boys and girls within the alcoholic and control groups. A second major limitation was that the results may not generalize to families of single mothers who either separated from or never cohabited with a partner with alcohol problems. Our inclusion criteria at recruitment consisted of families with biological parents who had cohabited since the child’s birth. This was essential for examining family processes in families with alcoholic fathers. However, this also impacted generalizability and resulted in less diversity in the sample because many minority families did not meet this inclusion criterion. The results are also not generalizable to families with heavy drinking/alcoholic mothers who had partners with no alcohol problems. However in the majority of families, maternal alcohol problems co-occur with paternal alcohol problems.

Future research could investigate the mechanisms through which parenting specific to emotion influences child behavior, emotional expression, and emotion modulation. In particular, these mechanisms may differ for alcoholic versus non-alcoholic families. In addition, observations of parenting specific to emotion could be utilized in future research, as the present study relied on parent-report. Negative emotionality may also contribute to later substance use problems, especially within the context of less adaptive parenting (Measselle, Stice, & Springer, 2006), delinquent peer association, and utilizing drinking as an affect regulation strategy (Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000). This effect may be exacerbated for children of alcoholics.

Conclusions and Implications

Results highlighted the importance of both mothers’ and fathers’ influence on emotional and behavioral development. Further, experiences of fathers’ alcohol problems increase the risk for partner conflict between parents and fathers’ use of non-supportive responses to their children’s emotions. Early experiences with parental psychopathology were also a central factor in both parenting specific to emotion and children’s negative emotionality and subsequent outcomes. Intervening with alcoholic families may need to target not only parental alcohol problems but also at the level of the marital or partner relationship to support effective parenting and co-parenting (e.g., Pruett et al., 2017). Focusing on alleviating parental mood disruptions may also be an important component for intervention efforts, given the pervasive and robust associations with child psychopathology and reduced supportive responses to child negative emotion even in the context of parent substance use problems (e.g., Luthar & Sexton, 2007). It may also be beneficial to increase parents’ awareness of the impact of their partner relationships and affective states on their parenting practices and children, especially reactions to their children’s negative emotions, while also promoting strategies for reducing potential spillover. Overall, providing support for parent mental health and enhancing warmth and sensitivity in parent-child interactions may have cascading positive effects for the family system.

Extending the SE model (Eisenberg et al., 1998a; 1998b) to at risk samples, including information from both mothers and fathers, and considering sex differences (e.g., Morris et al., 2007) expands this theoretical framework. More specifically, our results are supportive of diatheses stress or dual risk models indicating interactive effects of alcohol problems and co-occurring parental and family risks on children’s emotional development. Future research may also explore interactional and transactional processes between parents and children within the context of parent alcohol problems, as child behavior may not only be impacted by parent drinking but also exacerbate parent use. Although we were not able to examine if SE processes differed in families in which both parents had alcohol problems, this may be a good direction for future research. Prior studies have noted the high likelihood of individuals with similar drinking habits associating with each other (often called assortative mating) and significant prospective increases in alcohol use disorders in the spouse when married to a partner with alcohol use disorder (Kendler et al., 2018). Thus, interventions in families with two alcohol problem parents may need to target both parents in order to reduce likelihood of relapse. In addition, future work can incorporate the wider family system (e.g., siblings, extended family) within alcoholic and non-alcoholic families to understand how this network of influences may impact emotional development for children (Morris et al., 2007). Elucidating processes of SE in the context of parental substance use more globally will be especially relevant as substance use patterns evolve (i.e., opioid, electronic cigarette, cannabis, polysubstance use) and impact parent, child, and contextual factors.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Buffalo Longitudinal Study and the participating families for their support. This research was supported by Award 2012-W9-BX-0001, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice and by the National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse of the National Institutes of Health R01 AA010042 and R21AA021617. The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this exhibition are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Achenbach T (1991). Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC. (1994). Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: Basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 2, 244–268. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.2.3.244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data In Marcoulides GA & Shumaker RE (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques (pp. 243–277). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Ross D, & Ross SA (1961). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63(3), 575–582. doi: 10.1037/h0045925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bariola E, Gullone E, & Hughes EK (2011). Child and adolescent emotion regulation: The role of parental emotion regulation and expression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 198–212. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0092-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MA, & Scaramella LV (2013). Mothers’ parenting and child sex differences in behavior problems among African American preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(5), 773–783. doi: 10.1037/a0033792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N (1993). Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bongers IL, Koot HM, Van Der Ende J, & Verhulst FC (2004). Developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Child Development, 75(5), 1523–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00755.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1973). Separation: Anxiety & Anger. Attachment and Loss (vol. 2) International Psycho-analytical Library No.95. London: Hogarth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513–531. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JL, & Parke RD (1996). Reciprocal negative affect in parent-child interactions and children’s peer competency. Child Development, 67(5), 2217–2226. doi: 10.2307/1131619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano M, Perry-Parrish C, & Zeman J (2007). Influence of gender on parental socialization of children’s sadness regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 210–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00381.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Schwartz D, Dodge KA, & McBride-Chang C (2003). Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(4), 598–606. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Cole PM, & Zahn-Waxler C (2005). Parental socialization of emotion expression: gender differences and relations to child adjustment. Emotion, 5(1), 80–88. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R (1999). The Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment: A Factorial Validity Study. Educ. Psych. Measurement, 59, 821–846. doi: 10.1177/00131649921970161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, & Mudar P (1995). Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 990–1005. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Agocha VB, & Sheldon MS (2000). A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality, 68(6), 1059–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, & Paley B (2003). Understanding Families as Systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 193–196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, & Campbell SB (2000). Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JS, Pellegrini DS, Notarius CI, & Cummings EM (1989). Children’s responses to angry adult behavior as a function of marital distress and history of interparent hostility. Child Development, 60, 1035–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, & Cummings EM (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham S, & Kochanoff AT (2002). Parental contributions to preschoolers’ understanding of emotion. Marriage & Family Review, 34(3–4), 311–343. doi: 10.1300/J002v34n03_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, & Skinner ML (1991). Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology, 27(1), 172. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge K, Malone P, Lansford J, Miller S, Pettit G, & Bates J. (2009). A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-abuse onset. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 73(3), 1–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD (2018). Etiological processes for substance use disorders beginning in infancy In: Fitzgerald HE & I Puttler L (Eds.), Alcohol use disorders: A developmental science approach to etiology (pp. 97–113). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, & Leonard KE (2004). Predictors of effortful control among children of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fathers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65(3), 309–319. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, & Leonard KE (2007). A conceptual model for the development of externalizing behavior problems among kindergarten children of alcoholic families: Role of parenting and children’s self-regulation. Developmental Psychology, 43(5), 1187–1201. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Leonard KE, Hoyle RH, & Chavez F (2004). A transactional model of parent-infant interactions in alcoholic families. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(4), 350–361. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Lessard J, Colder CR, Livingston J, Casey M, & Leonard KE (2016). Developmental cascade model for adolescent substance use from infancy to late adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 52(10), 1619–1633.doi: 10.1037/dev0000199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, & Murphy BC (1996a). Parents’ reactions to children’s negative emotions: Relations to children’s social competence and comforting behavior. Child Development, 67(5), 2227–2247. doi: 10.2307/1131620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Maszk P, Holmgren R, & Suh K (1996b). The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology, 8(1), 141–162. doi: 10.1017/S095457940000701X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, & Spinrad TL (1998a). Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry, 9(4), 241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, & Cumberland A (1998b). The socialization of emotion: Reply to commentaries. Psychological Inquiry, 9(4), 317–333. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, & Reiser M (2000). Dispositional emotionality and regulation: their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(1), 136–157. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, ... & Guthrie IK (2001a). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72(4), 1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Gershoff ET, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Cumberland AJ, Losoya SH, ... & Murphy BC (2001b). Mother’s emotional expressivity and children’s behavior problems and social competence: Mediation through children’s regulation. Developmental Psychology, 37(4), 475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Hofer C, & Vaughan J (2007). Effortful control and its socioemotional consequences. Handbook of Emotion Regulation, 2, 287–288. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, & Eggum ND (2010). Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 495–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, & Bernzweig J (1990). The coping with children’s negative emotions scale: Procedures and scoring. Arizona State University. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Leonard SA, Kupanoff K, & Martin CL (2001). Parental coping with children’s negative emotions: Relations with children’s emotional and social responding. Child Development, 72(3), 907–920. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Dollberg D, Nadam R, 2011. The expression and regulation of anger in toddlers: relations to maternal behavior and mental representations. Infant Behav. Dev. 34 (2), 310–320. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan LJ, Schulz J, Gordon MS, & McCauley Ohannessian C (2015). Parental problem drinking and adolescent externalizing behaviors: The mediating role of family functioning. Journal of Adolescence, 43, 100–10. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger B, Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE, & Kachadourian L (2010). Marital aggression and child peer competence: A comparison of three conceptual models. Personal Relationships, 17(3), 357–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01284.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald H, & Eiden RD (2007). Paternal alcoholism, family functioning, and infant mental health. Zero to Three, 27, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, & Heyward D (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant K, Compas B, Thurm A, McMahon S, Gipson P, Campbell A, … & Westerholm R. (2006). Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Evidence of moderating and mediating effects. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 257–83.doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham HP, Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE. (1993). Assessing antisociality with the Antisocial Behavior Checklist: Reliability and validity studies. Poster presented at the annual meetings of the American Psychological Society; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, Maiese D, Hendershot T, Kwok RK, … & Nettles DS (2011) The PhenX Toolkit: Get the Most From Your Measures. American Journal of Epidemiology, 174(3), 253–60. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart C, Nelson D, Robinson C, Olsen S, & McNeilly-Choque M (1998). Overt and relational aggression in Russian nursery-school-age children: Parenting style and marital linkages. Developmental Psychology, 34(4), 687.doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.4.687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman C, Crnic K, & Baker J (2006). Maternal depression and parenting: Implications for children’s emergent emotion regulation and behavioral functioning. Parenting: Science and Practice, 6(4), 271–295. doi: 10.1207/s15327922par0604_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosley CA, & Montemayor R (1997). Fathers and adolescents In Lamb ME (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (pp. 162–178). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard DJ, & Pratt TC (2002). A meta-analysis of the predictors of delinquency among girls. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 34(3), 1–13. doi: 10.1300/J076v34n03_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson WW, & McIntosh SR (1981). The assessment of spouse abuse: Two quantifiable dimensions. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 43, 873–885.doi: 10.2307/351344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Flora DB, Curran PJ, Chassin LA, & Zucker RA (2008). Defining risk heterogeneity for internalizing symptoms among children of alcoholic parents. Development and Psychopathology, 20(1), 165–93. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Wirth RJ, Edwards MC, Curran PJ, Chassin LA, & Zucker RA (2007). Externalizing symptoms among children of alcoholic parents: Entry points for an antisocial pathway to alcoholism. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(3), 529–542. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE & Luxton DD (2005). “Vulnerability-Stress Models” In Hankin BL & Abela JRZ (Eds.), Development of Psychopathology: A vulnerability stress perspective (pp. 32–46). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, & Taylor A (2003). Life with (or without) father: The benefits of living with two biological parents depend on the father’s antisocial behavior. Child Development, 74(1), 109–126.doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Lönn SL, Salvatore J, Sundquist J, & Sundquist K (2018). The origin of spousal resemblance for alcohol use disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(3), 280–286. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wiltchen HE, Kendler KS. (1994). Lifetime and 12 month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2016). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (4th Edition). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE & Eiden RD (2007). Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 285–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman M, Doyle AB, & Markiewicz D (1999). Developmental patterns in security of attachment to mother and father in late childhood and early adolescence: Associations with peer relations. Child Development, 70(1), 202–213. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari RN and Van Horn SL (2017). Children living with parents who have a substance use disorder. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc, 83(404), 1198–1202. doi: 10.2307/2290157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Zucker R, Fitzgerald H, & Krull J (2003). Developmental trajectories of disruptive behavior problems among sons of alcoholics: Effects of parent psychopathology, family conflict, and child undercontrol. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(1), 119–131. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.1.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, & Neuman G (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(5), 561–592. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, & Sexton CC (2007). Maternal drug abuse versus maternal depression: Vulnerability and resilience among school-age and adolescent offspring. Development and Psychopathology, 19(1), 205–225. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H, & Romney DM (1991). Parents’ differential socialization of boys and girls: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 109(2), 267–296.doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.2.267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, & Williams J (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]