Abstract

The current study evaluated bidirectional associations between mother and father positive parenting and child effortful control during childhood. Data were drawn from 220 families when children were 3, 4, 5, and 6 years old. Parenting and effortful control were assessed when the child was 3, 4, and 5 years old. These variables were used to statistically predict child externalizing and school performance assessed when the child was 6 years old. The study used random intercept cross-lagged panel models (RI-CLPM) to evaluate within-person and between-person associations between parenting and effortful control. Results suggested that prior positive parenting was associated with later effortful control whereas effortful control was not associated with subsequent parenting from ages 3 to 5. Stable between-child differences in effortful control from ages 3 to 5 were associated with school performance at age 6. These stable between-child differences in effortful control were correlated with externalizing at age 3.

Keywords: effortful control, positive parenting, externalizing behavior, school performance, random intercept cross-lagged panel models

Contemporary transactional perspectives on human development emphasize the dynamic interplay between children and their social environments and interactions with caregivers (see Sameroff & MacKenzie, 2003). This concept of a mutually influencing process is a central theme of current research about temperament, parenting, and developmental outcomes (e.g., Rothbart, 2011). Some studies suggest that parents influence child temperament (Sulik, Blair, Mills-Koonce, Berry, & Greenberg, 2015), others find that child temperament influences parenting behavior (Ganiban, Ulbricht, Saudino, Reiss, & Neiderhiser, 2011) and still others provide evidence for bidirectional effects of parenting and child temperament (Lee, Zhou, Eisenberg, & Wang, 2012; Sameroff & MacKenzie, 2003). The current study adds to this literature by evaluating the longitudinal associations between positive parenting and child effortful control given that effortful control seems to play a fundamental role in self-regulation (Durbin, 2018; Rothbart & Rueda, 2005) and has been associated with academic performance and externalizing behaviors (Blair & Razza, 2007; Eisenberg et al., 2004).

The model of the socialization of emotion proposed by Eisenberg and her colleagues (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998) is a clear example of theorizing about transactional processes in human development. This model posits that both parent and child characteristics related to emotion regulation influence parental behaviors such as the expression and discussion of emotion. It further suggests that unsupportive or negative parental reactions likely heighten children’s emotional arousal whereas supportive or positive parental reactions may attenuate child arousal. Child emotional arousal is then associated with subsequent child outcomes. This model and transactional perspectives on human development informed the current study focused on effortful control, a broad individual difference implicated in self-control and emotion regulation.

Parent socialization patterns of emotion-regulation might depend on parent gender (Elam, Chassin, Eisenberg, & Spinrad, 2017). However, previous studies have primarily examined the behavior of mothers or the primary caregiver (i.e., Eisenberg, Taylor, Widaman, & Spinard, 2015; Eisenberg et al., 2005). Thus, we evaluate associations between children’s effortful control and both mother and father positive parenting across 3-waves of data when children were between the ages of 3 and 5 years old. We also test how these constructs relate to externalizing problems and school performance at age 6. We now turn to a review of the literature surrounding our primary constructs – effortful control and parenting.

Effortful Control and Child Development

Effortful control is defined as “the ability to inhibit a dominant response to perform a subdominant response, to detect errors, and to engage in planning” (Rothbart & Rueda, 2005, p. 3) and is considered to be a major domain of temperament (e.g., Rothbart, 2007). Effortful control includes the dimensions of inhibitory control, attentional focusing, and attentional shifting (Eisenberg et al., 2001). Self-regulatory abilities like effortful control seem to emerge between 6 and 12 months of age (Rothbart & Bates, 1998) and increase during the preschool years (Carlson, 2005). At the same time, there is evidence of consistent individual differences in effortful control such that children with relatively high (or low) levels at one time point also tend to exhibit relatively high (or low) levels in the future (e.g., Neppl et al., 2010). Thus, effortful control appears to be a relatively stable individual characteristic (Kochanska & Knaack, 2003).

One important component of effortful control is the ability to initiate or suppress a behavior. Hence, effortful control has been associated with externalizing problems, especially after 54 months of age (Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, 2010). For example, Eisenberg et al. (2004) found that low effortful control directly related to children’s externalizing problems. They also tested for bidirectional associations between externalizing problems and effortful control and concluded that the evidence was more consistent with a unidirectional association whereby effortful control had a prospective association with externalizing behavior but not vice versa (Eisenberg et al., 2004). Similarly, Schoppe-Sullivan, Weldon, Cook, Davis, and Buckley (2009) found effortful control at age 4 predicted externalizing behavior approximately one year later while taking into account externalizing behavior at age 4.

In addition to externalizing behavior, effortful control is linked to school achievement. For example, Blair and Razza, (2007) examined the association between self-regulation and academic ability in a sample of 3- to 5-year old children. They found that measures of effortful control in preschool were associated with math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Similarly, Feldmann, Martinez-Pons, and Shaham (1995) found that higher control correlated with academic achievement as measured by grades. Sánchez-Pérez, Fuentes, Eisenberg, and González-Salinas (2018) found that effortful control was indirectly related to academic achievement through learning-related behaviors. Finally, effortful control in kindergarten was associated with academic achievement in first grade (Hernández et al., 2017), and effortful control in first grade was related to school achievement in third grade, controlling for age, IQ, gender, ethnicity, and economic adversity (Liew, McTigue, Barrois, & Hughes, 2008).

Parenting and Effortful Control

Research suggests that parents help their child regulate emotions and behaviors, thus parenting is often associated with the development of effortful control (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005). For example, harsh parenting behavior may lead to over aroused children who are less able to focus or shift attention as needed (Hoffman, 2000). In contrast, parents who are warm and supportive may foster children to be more self-regulated and less likely to become frustrated or angry. That is, parents who display high levels of positive emotion help their children understand and express similar types of emotion (Valiente et al., 2004). Thus, children may be less likely to display externalizing behaviors elicited from such emotional responses (Eisenberg et al., 2005). Brody and Ge (2001) found that supportive parenting was associated with early adolescent self-control, which was associated with problematic adjustment. However, they did not find that effortful control was associated with later supportive parenting. Similarly, Spinrad et al. (2007) found that maternal supportive parenting during the preschool years was associated with child effortful control both concurrently and across time. Moreover, mothers who used communication with a positive emotional tone related to their children’s effortful control over two years later (Cipriano & Stifter, 2010). Belsky, Pasco Fearon, and Bell (2007) examined maternal sensitivity and found that it was associated with child attentional control two years later. Thus, positive parenting may facilitate the development of effortful control.

Conversely, there is some evidence to suggest that attributes of children may elicit particular parenting behaviors such as positive guidance in the way of praise, positive affect and positive feedback (see Eisenberg, Vidmar, et al., 2010). For example, Belsky et al. (2007) found that child attention regulation predicted mother support across time, and Lengua (2006) found that lower levels of child effortful control related to more parental rejection and inconsistent discipline. Eisenberg, Vidmar, et al. (2010) found that children’s effortful control in early childhood predicted mothers’ use of verbal strategies to scaffold her child’s knowledge a year later, even after controlling for prior levels of parenting. More recently, Blair, Raver, Berry, and the Family Life Project Investigators (2014) found that executive function at age 36 months predicted changes in parenting from 36 to 60 months old. Similarly, Ansari and Crosnoe (2015) found positive changes in parenting for those children who demonstrated early reading skills and less problematic behavior.

There is also evidence for bidirectional associations between temperament and parenting. For example, Eisenberg et al. (1999) found that child negative emotionality at age 6 to 8 years related to parental distress reaction at 8 to 10 years. This was then associated with children’s higher negative emotionality at ages 10 to 12 years. Lee et al. (2012) found bidirectional associations between parenting and child effortful control. Specifically, low effortful control predicted authoritarian parenting over time, and high authoritarian parenting predicted less child self-regulation across time. Moreover, Eisenberg et al. (2015) examined bidirectional longitudinal relations between parenting, effortful control, and externalizing behavior and found evidence for both kinds of effects. That is, they found a predictive effect of effortful control on parenting, as well as a predictive effect of parenting on children’s effortful control. Likewise, Tiberio et al. (2016) found that for younger children, effortful control influenced positive parenting and at older ages, parenting influenced effortful control.

An unresolved issue in the parenting and temperament literature concerns the possibility of differential parenting effects for mothers and fathers. The literature is somewhat limited for making strong predictions because many studies on parenting and children’s self-regulation primarily focus on the mother-child relationship with less attention to the role of fathers (see Eisenberg, Taylor, Widaman, & Spinard, 2015; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Karreman, van Tuijl, van Aken, & Deković, 2010). Nonetheless, including fathers in studies of temperament and parenting is important as about 88% of families with children under the age of 12 have a father in the household (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018). In addition, fathers are spending an increased amount of time with their children (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004).

Existing studies suggest that some of the behavioral interactions with children are different for fathers and mothers. For example, earlier studies suggest that fathers tend to be more playmates to their children whereas mothers tend to be caregivers (Lamb, 2004). Often through physical play, fathers may encourage more emotional stimulation, problem solving, and taking chances with the outside world (see Paquette, 2004). Thus, due to cognitive stimulation, high arousal and excitement levels yielded from such interactions with fathers may be important in the development of executive functioning (Grossman, Grossman, Kindler, & Zimmerman, 2008). On the other hand, mothers tend to be the source of comfort in stressful situations and verbalize more emotion-related content. This process may lead to expectations for stronger maternal effects. Karreman et al. (2010) examined the relation between child effortful control and parenting behavior that displayed positive control and reasoning separately for mothers and fathers. They found that maternal and paternal parenting were both associated with effortful control, and paternal parenting related to child effortful control above maternal parenting. In addition, children’s difficult behavior may be more influential for mother versus father parenting (Elam et al., 2017). Given the state of the existing literature, we think it is important to include both mothers and fathers in research and to test whether the associations between temperament and parenting differ by parental gender. This strategy will provide more needed data on this topic. Accordingly, we evaluate associations between children’s effortful control and both mother and father positive parenting across 3-waves of data when children were between the ages of 3 and 5 years old.

Does Effortful Control Explain Associations Between Parenting and Child Outcomes?

Effortful control may help explain associations between parenting and child developmental outcomes. For instance, Eisenberg et al. (2005) found that children’s effortful control mediated the relation between positive parenting and children’s externalizing behavior. Specifically, parenting that included positive affect and verbal affection in the mid-elementary school years predicted children’s effortful control two years later, which was associated with lower externalizing problems during adolescence. This was true even after controlling for the stability of relations over time. Similarly, Chang, Olson, Sameroff, and Sexton (2011) found that effortful control in 3-year old boys mediated the association between warm responsive parenting (i.e., nurturance, responsiveness, and reasoning or talking to the child) via maternal report at age 3 and externalizing behavior at age 6. Likewise, Eiden, Edwards, and Leonard (2007) found that self-regulation at age 3 mediated the relation between parenting at age 2 and externalizing behavior at age 5 among children of alcoholic parents. More recently, Sulik et al. (2015) showed that the association between primary caregiver parenting at 36-months and externalizing at 60-months was mediated by 48-month executive functioning.

In addition, Swanson, et al. (2014) prospectively examined relations between parental reaction to children’s negative emotions, effortful control, and math achievement. They found evidence that effortful control in first grade mediated the relation between parents’ positive reactions at kindergarten and math achievement in second grade. Wang, Deng, and Du (2018) found that harsh parenting negatively related to academic achievement through effortful control in a sample of sixth through eighth graders. Kopystynska, Spinrad, Seay, and Eisenberg (2016) found that when mother sensitivity was high, effortful control mediated the association between mother gentle control and child academic functioning. However, when mother sensitivity was low, this relation was not significant. Collectively, these results suggest effortful control may partially explain associations between parenting and important developmental outcomes. However, not all studies find evidence for mediation, especially at younger ages. For example, Eisenberg and colleagues (2010) found that effortful control at 30 months did not mediate the association between maternal parenting at 18 months and externalizing behavior at 42 months.

The Present Investigation

The present investigation extends earlier research by evaluating bidirectional relations between parenting and young children’s effortful control across time and testing how both relate to subsequent developmental outcomes. The association between parenting and effortful control is well documented with studies that examine mother behavior or combine mother and father in relation to child effortful control and externalizing behavior. For example, Eisenberg et al. (2015) examined observed intrusive maternal parenting, effortful control, and externalizing behavior of young children. Eisenberg et al. (2005) found that effortful control mediated the relation between the primary caregiver’s positive parenting and low levels of externalizing behavior for early adolescents. We extend this work by examining parenting behavior of both mothers and fathers separately in the model. We also add to the dearth research on the association between positive parenting and effortful control on school performance (Swanson, Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant, Bradley, & Eggum-Wilkens, 2014). Finally, we used a recently proposed statistical model that helps to disentangle between-person and within-person variability to more precisely estimate relations between parenting, effortful control, and developmental outcomes. Previous work has tended to use a standard cross-lagged model which is becoming increasingly controversial in developmental research (Berry & Willoughby, 2016). A concern about the standard cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) is that trait-like individual differences are not completely isolated from within-person processes when evaluating reciprocal associations.

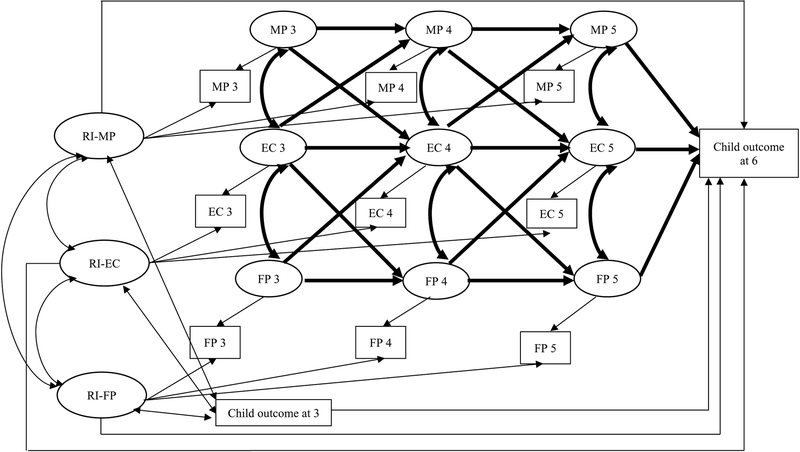

To address the concerns with the traditional CLPM, we used the random intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM; Hamaker, Kuiper, & Grasman 2015) to evaluate how parenting and child effortful control are associated across the preschool years. By adding random intercepts for psychological constructs to the CLPM, the RI-CLPM can separate consistent individual differences (i.e., stable individual difference) from within-person (or parent) variations for the three developmental constructs (i.e., mother parenting, father parenting, and effortful control) across time. In the present study, the RI-CLPM allowed us to model the associations between stable individual differences in effortful control and positive parenting, as well as the associations between within-person variation in effortful control and within-family variation in parenting over time. We then used these separate sources of variability to predict externalizing problems and school performance at age 6 (see Figure 1). To provide additional constraints on inferences, we included age 3 controls of externalizing behavior and receptive vocabulary. We expect that within person variations in effortful control will partially mediate the association between positive parenting and child developmental outcomes. Further, we tested whether paternal and maternal positive parenting had differential associations with child effortful control. Van Lissa, Keizer, Van Lier, Meeus, and Branje (2019) showed that mothers showed more support with their child, while fathers displayed more behavioral control. Others have found that greater levels of positivity in both parents related to child prosocial behavior (Gryczkowski, Jordan, & Mercer, 2018). Thus, it could be that mother positive parenting may have a differential association from fathers, or it could also be there will be no differential effects between mothers and fathers.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model.

Notes: Example of the random intercept cross lagged panel model (RI-CLPM). Bolded lines indicate intraindividual changes. Un-bolded lines indicate interindividual differences. MP = mother parenting, FP = father parenting, EC = effortful control. Specific child ages are indicated by numbers after MP, FP and EC: 3 = age 3, 4 = age 4, 5 = age 5.

In addition to age 3 covariates of externalizing behavior and receptive vocabulary, we also controlled for parental age, parental relationship status, per capita income, and child gender. Previous research shows these control variables may relate to child and parenting behaviors. For example, children born to younger parents display poorer impulse control and parenting behavior (Florsheim et al., 2003). Girls may also be rated higher than boys in both observational and other reports of effortful control (Li-Grining, 2007). In terms of income, it has been found that the relation between parenting and child regulation may be stronger for young children in disadvantaged circumstances (Raver, 2004).

Method

Participants

Data are drawn from the Family Transitions Project (FTP), a longitudinal study of 559 target youth and their families of origin. The FTP represents an extension of two earlier studies: The Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP; N = 451) and the Iowa Single Parent Project (ISPP; N = 108). In the IYFP, data were collected annually from 1989 through 1992. Participants included the target adolescent, his/her parents, and a sibling within 4 years of age of the target adolescent (217 females, 234 males). These families were originally recruited for a study of family economic stress in the rural Midwest. When interviewed in 1989, the target adolescent was in seventh grade (M age = 12.7 years; 236 females, 215 males). Families were recruited from schools in eight rural Iowa counties. Due to the rural nature of the sample there were few minority families; therefore, all participants were Caucasian. Seventy-eight percent of eligible families agreed to participate in the study. Families were primarily lower middle- or middle-class with 34% residing on farms, 12% living in nonfarm rural areas, and 54% living in towns with fewer than 6,500 residents. In 1989, parents averaged 13 years of schooling and had a median family income of $33,700. Fathers’ average age was 40 years and mothers’ average age was 38.

The ISPP began in 1991 when the target adolescent was in 9th grade (M age = 14.8 years), the same year of school as the IYFP target youth. Participants included the target adolescent, his/her single-parent mother, and a sibling within 4 years of age of the target. Families were headed by a mother who had experienced divorce within two years prior to the start of the study. All but three eligible families agreed to participate. The participants were Caucasian, primarily lower middle- or middle-class, one-parent families that lived in the same general geographic area as the IYFP families. Measures and procedures for the IYFP and ISPP were identical.

In 1994, ISPP families were combined with the IYFP to create the FTP. At that time adolescents from both studies were in 12th grade. In 1994, the target adolescent participated with their parents as they had during earlier years of adolescence. Beginning in 1995, the target adolescent (1 year after completion of high school) participated in the study with a romantic partner. In 1997, the study was expanded to include the first-born child of the target adolescent, now a young adult. To be eligible for the study, the target’s child had to be at least 18 months of age. By 2005, the children of the FTP targets ranged in age from 18 months to 13 years old.

The present report included 220 target adults (M age = 26; female = 60%) who had an eligible child (male = 53%) participating in the study at least once by 2005. The report also includes the target’s romantic partner (spouse, cohabitating partner, or boy/girlfriend) who was either the other biological parent, step-parent, or parental figure to the target’s child. Thus, only families with two parents were included in the analyses. In addition, mothers could either be the target parent or the target’s partner, with the same being true for fathers. The data were analyzed at four time points when the eligible child was 3, 4, 5 and 6 years old. Time 1 included 186 children at age 3 (boys = 93, 50%). Time 2 included 149 children at age 4 (boys = 80, 54%). Time 3 included 147 children at age 5 (boys = 85, 58%). Time 4 included 114 children at age 6 (boys = 71, 62%). There were 31% who participated at all four time points, 31% who participated at three time points, 16% who participated at two time points, and 22% who participated at one time point. The FTP has been approved by the Institutional Review Board at Iowa State University (The Family Transitions Project, #06–086).

Procedure

From 1997 through 2005, the target parent, his/her romantic partner, and the target’s first-born child were visited in their home each year by a trained interviewer. During the visit, the target parent and romantic partner completed a number of questionnaires, some of which included measures of child characteristics. In addition to questionnaires, the target parent and romantic partner each participated in separate videotaped structured interaction tasks that included a 5-minute puzzle completion task with their child. First fathers completed a puzzle with the child, then mothers completed a different puzzle with the child. Each parent and their child were presented with a puzzle that was too difficult for the child to complete alone. Parents were instructed that children must complete the puzzle alone, but they could provide any assistance necessary. Puzzles varied by age group so that the puzzle slightly exceeded the child’s skill level. This was to create a stressful environment for both parent and child, and thus, the resulting behaviors indicated how well the parent handled the stress and how adaptive the child was to an environmental challenge. It was expected that positive and nurturing parents would remain supportive toward the child throughout the task. Trained observers, who met 80% criterion, coded aspects of positive parenting from video recordings of the puzzle task using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Melby et al., 1998). To ensure reliability, 25% of the observed interaction tasks were rated by two randomly assigned independent coders. The number of coders varied in any given wave but ranged from 4 to 8 over the years of data collection.

Measures

The means, standard deviations, minimum, and maximum scores for all study variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for study variables (N =220)

| Variables | Min | Max | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effortful Control Age 3 | 3.14 | 5.63 | 4.19 | .46 |

| Effortful Control Age 4 | 1.85 | 5.70 | 4.22 | .59 |

| Effortful Control Age 5 | 2.85 | 6.44 | 4.26 | .56 |

| Mother Positive Parenting Age 3 | 2.00 | 8.67 | 5.85 | 1.33 |

| Mother Positive Parenting Age 4 | 1.33 | 9.00 | 5.42 | 1.41 |

| Mother Positive Parenting Age 5 | 1.00 | 8.67 | 5.74 | 1.59 |

| Father Positive Parenting Age 3 | 1.33 | 9.00 | 5.71 | 1.47 |

| Father Positive Parenting Age 4 | 2.33 | 8.67 | 5.45 | 1.38 |

| Father Positive Parenting Age 5 | 1.00 | 8.00 | 5.31 | 1.48 |

| Child Externalizing Age 6 | .00 | .80 | .23 | .17 |

| Child Externalizing Age 3 | .03 | 1.23 | .48 | .21 |

| School Performance Age 6 | 2.25 | 5.00 | 3.94 | .52 |

| Receptive vocabulary skills Age 3 | 55 | 131 | 96.83 | 15.68 |

| Mother Age | 20 | 42 | 25.68 | 3.00 |

| Father Age | 20 | 49 | 27.54 | 3.89 |

| Relationship Status (1= married or cohabitating) | 68% | |||

| Per Capita Income | .00 | 145,166 | 16,573 | 13,737 |

| Child Gender (1=male) | 53% |

Effortful control.

Effortful control was measured as a manifest variable using the mean of the three indicators: Inhibitory control, attentional focusing and attentional shifting (Child Behavior Questionnaire; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001). The three indicators were scored by mothers and fathers when the child was 3, 4 and 5 years old. Inhibitory control is the capacity to plan and to suppress inappropriate approach responses under instructions or in novel or uncertain situations. The inhibitory control scale included thirteen questions such as: “Can lower his/her voice when asked to do so”, “Has a hard time following instructions”, and “Has trouble sitting still when she/he is told to”. Attention focusing is the tendency to maintain attentional focus upon task-related channels. This scale included nine questions such as: “Will move from one task to another without completing” and “When drawing or coloring in a book, shows strong concentration”. Attentional shifting is the ability to transfer attentional focus from one activity/task to another. This scale included five questions such as “Can easily shift from one activity to another”, “Has a lot of trouble stopping an activity when called to”, and “Has an easy time leaving play to come to dinner”. All responses ranged from 1 = extremely untrue to 7 = extremely true. For each indicator, items were first averaged for each parent and then averaged across mother and father responses. The average of the three indicators was used as a manifest variable at age 3, 4 and 5 in the final model. A high score indicates a higher level of child effortful control. The three indicators were correlated with each other at each age except that attention focusing was trending with attentional shifting at age 3. The alpha coefficients for the averaged mother and father subscales of inhibitory control, attentional focusing, and attentional shifting were .84, .78, and .59, respectively at age 3, .88, .77, and .71, respectively at age 4, and .85, .79, and .70, respectively at age 5. Correlations for the average of the three indicators of effortful control between mother and father report were .42, .56, .50 (at ages 3, 4, and 5 respectively).

Positive parenting.

Direct observations assessed both mother and father behavior toward the child at ages 3, 4, and 5 during the videotaped puzzle task. One score on a 9-point scale, ranging from 1 (no evidence of the behavior) to 9 (the behavior is highly characteristic of the parent) was given for each of the 5-minute mother-child and father-child puzzle tasks by trained observers. Positive mood involves the degree to which the parent demonstrates happiness, optimism, and positive behavior. It assesses how positive the parent seems to feel through smiling, laughing, and interacting positively with the child. Communication measures verbal expressive skills and content of statements. It assesses the parent’s ability to convey needs/wants, and clarify points of view in a positive manner. This scale involves soliciting the child’s views, explaining viewpoints, and responding reasonably and appropriately to ongoing conversation. Assertiveness is the manner and style of confident and positive expression while exhibiting patience with the responses of the child. It includes the parent expressing his/her views in an open and straightforward style through appropriate, clear, and positive avenues. It also assess nonverbal communication such as having eye contact and orienting the body toward the child when interacting. The scores on the three indicators created separate manifest variables of positive parenting for each parent when the child was 3, 4, or 5 years old. Scores for the positive parenting construct (positive mood, communication, and assertiveness) were internally consistent for mothers (α = .80 at age 3; α = .84 at age 4; α = .86 at age 5) and fathers (α = .85 at age 3; α = .79 at age 4; α = .85 at age 5). Inter-rater reliability between the primary and reliability coders for positive parenting across the three time points was significant and adequate for mothers: positive mood (r = .82 at age 3, r = .85 at age 4, r = 81 at age 5), communication (r = .55 at age 3, r = .28 (marginal) at age 4, r = .66 at age 5), and assertiveness (r = .69 at age 3, r = .42 at age 4, r = .52 at age 5). The inter-rater reliability was also significant for father positive mood (r = .86 at age 3, r = .87 at age 4, r = .83 at age 5), communication (r = .60 at age 3, r = .47 at age 4, r = 79 at age 5), and assertiveness (r = .71 at age 3, r = .36 at age 4, r = .84 at age 5).

Child externalizing behavior.

When the child was 6 years old, mothers and fathers completed the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 6–18 (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). Externalizing behavior included the 17 item rule breaking and 18 item aggressive behavior subscales. Parents rated each statement on a 3-point scale ranging from not true to very true regarding their child’s behavior during the past 2 months. Sample items from the rule-breaking subscale include lacks guilt, runs away, and lies or cheats. Sample items from the aggressive behavior subscale include argues a lot, gets in fights, attacks people, and is disobedient at home and at school. Mother reported rule breaking was not associated with father reported rule breaking (r = .14 p = .22) but was associated with father reported aggressive behavior (r =.24, p <.05). Mother reported aggressive behavior was associated with father reported rule breaking and aggressive behavior (r =.21 p < .05; r = 40, p < .001). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients indicated very good internal consistency (α = .91). Items were averaged across parents and subscales to create a total score. We used this aggregation strategy to be as inclusive as possible when measuring externalizing problems.

Child school performance.

Mothers and fathers reported on their child’s school performance when the child was 6 years old. Child school performance was assessed with two items. The first item asked parents about their child’s performance in school. Responses ranged from 1 = superior to 5 = far below average. The second item asked parents about how their child keeps up with school work. Responses ranged from 1 = far behind and hard to catch up to 5 = ahead of most classmates. The two items were averaged across parents and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient indicated good internal consistency (α = .78).

Control variables.

The control variables included parental age, parental relationship status (1= married or cohabitating, 0= not married or cohabitating), per capita income (measured by calculating the family’s total income and then dividing this by the number of members in the household), and child gender (0= female, 1= male). We also controlled for externalizing behavior at age 3 using parent report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000; α =.90) for the externalizing model and receptive vocabulary from the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Dunn & Dunn, 1981, 1997) at age 3 for the school performance model.

Results

We first conducted supplementary analyses to identify whether there were differences in demographic characteristics and main study constructs between those who were missing and those who remained in the study. Results of the one-way ANOVA showed that parents who participated at one time point were more likely to be older and have higher income than parents who participated in all time points. Correlations between all study variables are presented in Table 2. In general, the patterns of association suggest that there was stability in the core constructs. These correlations provide the descriptive context for interpreting the longitudinal models. We estimated the RI-CLPM using Mplus Version 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) with Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML; Muthén & Muthén, 2012). FIML is widely used and recommended for dealing with missing data (Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker, 2013). Several indices were used to evaluate model fit: the standard chi–square index, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1992) and the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990). RMSEA values under .05 indicate close fit to the data, and values between .05 and .08 represent reasonable fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1992). Values greater than .95 for the CFI were interpreted as excellent whereas values above .90 were considered acceptable (e.g., Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Table 2.

Correlations between the variables used in analyses (N =220)

| Study constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Effortful Control Age 3 | - | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Effortful Control Age 4 | .75*** | - | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Effortful Control Age 5 | .67*** | .74*** | - | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Mother Positive Parenting Age 3 | .11 | .23** | .10 | - | |||||||||||||

| 5. Mother Positive Parenting Age 4 | .18* | .26** | .25** | .57*** | - | ||||||||||||

| 6. Mother Positive Parenting Age 5 | .15 | .21* | .24** | .47*** | .51*** | - | |||||||||||

| 7. Father Positive Parenting Age 3 | .16* | .30*** | .20* | .50*** | .55*** | .34*** | - | ||||||||||

| 8. Father Positive Parenting Age 4 | .08 | .11 | .19 | .36*** | .38*** | .16 | .50*** | - | |||||||||

| 9. Father Positive Parenting Age 5 | −.01 | .06 | .01 | .35*** | .26** | .15 | .46*** | .55*** | - | ||||||||

| 10. Child Externalizing Age 6 | −.33*** | −.45*** | −.35*** | −.03 | −.15 | −.07 | −.18 | .03 | −.06 | - | |||||||

| 11. Child Externalizing Age 3 | −.53*** | −.48*** | −.38*** | −.21** | −.22** | −.22* | −.25** | .03 | −.07 | .42*** | |||||||

| 12. School Performance Age 6 | .40*** | .49*** | .51*** | .30** | .20 | .13 | .33*** | .17 | .20 | −.35*** | −.42*** | ||||||

| 13. Receptive vocabulary Age 3 | .15* | .20* | .22* | .34*** | .23** | .17 | .34*** | .30** | .34*** | −.01 | −.10 | .34*** | |||||

| 14. Mother Age | .00 | .11 | .03 | .58*** | .35*** | .27** | .44*** | .19 | .29** | −.02 | −.24** | .37** | .24** | ||||

| 15. Father Age | .09 | .21** | .18* | .25*** | .15 | .05 | .15* | .09 | .02 | −.08 | −.13 | .23** | .25*** | .48*** | |||

| 16. Relationship Status | −.01 | .08 | .01 | −.18* | −.15 | −.21* | −.25** | 31*** | −.38*** | −.02 | .05 | −.02 | −.15 | −.17* | −.12 | ||

| 17. Per Capita Income | .08 | .11 | .03 | .21* | .20* | .19* | .22** | .12 | −.05 | −.09 | −.28*** | .14 | .06 | .28** | −.18* | −.20* | |

| 18. Child Gender (male=1) | −.26*** | −.18* | −.21** | .01 | −.07 | −.12 | .05 | −.04 | −.08 | .12 | .18** | −.25** | −.17* | −.15* | −.07 | .01 | −.06 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

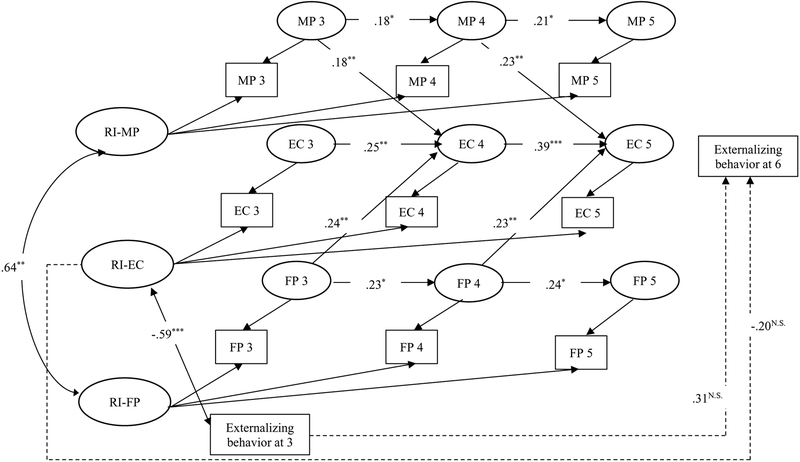

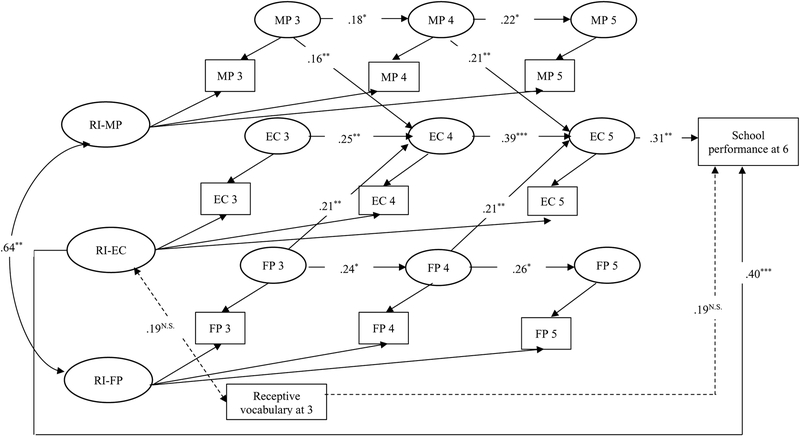

Two models were analyzed; one for externalizing behavior (see Figure 2) and the other for school performance (see Figure 3). We also tested “free” and “fixed” versions of each model. The free version separately estimated all parameters, whereas the fixed model imposed equality constraints on the autoregressive and cross-lagged paths of each construct (i.e. positive parenting and effortful control) over time, as well as imposing equality constraints on the mother and father paths. For example, in the fixed model the autoregressive path from mother and father positive parenting at 3 to 4 (a) and the path from mother and father positive parenting at 4 to 5 (a) were equated. Likewise the autoregressive paths of effortful control were equated in the same way [i.e., effortful control at age 3 to 4 (b) and effortful control at age 4 to 5 (b)]. In addition, the cross-lagged path from mother and father positive parenting at 3 to effortful control at 4 (c) and the path from mother and father positive parenting at 4 to effortful control at 5 (c) were equated. Similarly, the cross-lagged paths from effortful control to mother and father positive parenting were equated (d). Correlations between random intercepts of mother and father parenting and random intercept of effortful were equated (e) and paths from random intercepts of mother and father parenting to externalizing behavior were equated (f).

Figure 2. Random intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM) for externalizing behavior (N =220).

Notes: Results of the random intercept cross lagged panel model (RI-CLPM) with externalizing behavior at age 6 as the outcome. MP = mother parenting, FP = father parenting, EC = effortful control. Specific child ages are indicated by numbers after MP, FP and EC: 3 = age 3, 4 = age 4, 5 = age 5. Except for behavior at age 3, only significant standardized coefficients were provided. *p < .05, **p < .01. Model fit: χ2 =119.18, df =78, p < .01, CFI =.93, RMSEA =.05 [.03, 07].

Figure 3. Random intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM) for school performance (N =220).

Notes: Results of the random intercept cross lagged panel model (RI-CLPM) with school performance at age 6 as the outcome. MP = mother parenting, FP = father parenting, EC = effortful control. Specific child ages are indicated by numbers after MP, FP and EC: 3 = mother parenting, FP = father parenting, EC = effortful control. Specific child ages are indicated by numbers after MP, FP and EC: 3 = age 3, 4 = age 4, 5 = age 5. Except for vocabulary at age 3, only significant standardized coefficients were provided. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Model fit χ2 =114.72, df =78, p < .01, CFI =.93, RMSEA =.05 [.03, 06].

The free and fixed versions of the models for both the externalizing and school performance models (externalizing model: Δχ2 = 24.61, Δdf =21, p =.26, school performance model: Δχ2 = 25.12, Δdf = 21, p =.24) were not significantly different based on the chi-square difference tests. Thus, the fixed model which is considered a more parsimonious model was used as the final model for both externalizing and school performance. The final fixed models had the following fit statistics: Externalizing model χ2 = 119.18, df = 78, p <. 01 CFI = .93, and RMSEA =.05 [.03, 07]; school performance model χ2 = 114.72, df = 78, p <. 01 CFI = .93, and RMSEA =.05 [.03, 06]. We also estimated an externalizing and school performance model without cross-lagged effects (χ2 = 129.97, df = 80, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .91; χ2 = 123.56, df = 80, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .92) and compared these models with the fixed models including cross-lagged effects. We found the models without cross-lagged paths were significantly different with the final fixed models based on the chi-square difference test (Δχ2 = 10.79, Δdf = 2, p < .01; Δχ2 = 8.84, Δdf = 2, p < .05). This test suggests that it was reasonable to consider cross-lagged associations for positive parenting and parental perceptions’ of children’s effortful control.

For the externalizing model (see Figure 2), which included child externalizing behavior at age 3, the random intercept for effortful control was not significantly associated with the random intercepts for mother and father positive parenting. That is, stable between-child differences in effortful control were not associated with stable between-parent differences in positive parenting (b=.05, SE=.04). Autoregressive paths for effortful control and mother and father positive parenting were significant across time. Results indicate that children who were relatively high (or low) on effortful control compared to their stable baseline at a given assessment, also tended to be high or low at the next occasion. Similarly, mothers and fathers who were relatively high (or low) on positive parenting compared to their stable baseline, also tended to be high or low at the next occasion.

In terms of cross-lagged effects, mother and father positive parenting at age 3 predicted effortful control at age 4, and mother and father positive parenting at age 4 predicted effortful control at age 5. These pathways suggest that within-family variability in both mother and father positive parenting were associated with future within-child variability in effortful control. In other words, when parents were more (or less) positive than their baseline at a given wave, the child tended to have higher (or lower) levels of effortful control at the subsequent wave. Effortful control did not have cross-lagged effects on parenting. The random intercept of effortful control and externalizing behavior at age 3 were strongly correlated (r = −.59, SE =.07, p <.001; see also Table 2). This reflects the well-known association between effortful control and externalizing problems (Eisenberg et al., 2004). This correlation, however, may create an issue for interpreting the path coefficients to age 6 externalizing problems. Indeed, both the path from the random intercept of effortful control to externalizing behavior at age 6 and the path from externalizing behavior at 3 to externalizing behavior at 6 were not statistically significant (b= −.09, 95% CI = − .25 ~ .07; b = .25, 95% CI = −.02 ~ .52).

In terms of the school performance model (see Figure 3), which included receptive vocabulary skills at age 3, the results were similar to the externalizing model in terms of the associations between parenting and effortful control. However, the random-intercept of effortful control positively predicted school performance at age 6. In addition, the intra-individual effortful control at age 5 was also related to school performance at age 6. This suggests that children who were especially high (versus low) in effortful control relative to their baseline at age 5 were also doing better in school at age 6. This raises the possibility that within-person fluctuations in effortful control and trait-like individual differences are relevant for school performance in childhood. Moreover, the evidence for truly prospective effects of effortful control on subsequent outcomes appear to be stronger for school performance than for externalizing problems.

Finally, we tested for mediational effects and found two specific indirect paths from the school performance model. First, when parents were more (or less) positive at age 3 than their baseline at a given wave, the child tended to have higher (or lower) levels of effortful control at the subsequent waves (at age 4 and 5) which, in turn, was associated with children’s school performance at age 6 (β = .026, 95% confidence interval [CI] [.001 ~ .051]. Second, when parents were more (or less) positive at age 4 than their baseline at a given wave, the child tended to have higher (or lower) levels of effortful control at age 5 which, in turn, was associated with children’s school performance at age 6 (β = .066, 95% confidence interval [CI] [.007 ~ .126]. The results suggest that higher (or lower) levels of effortful control while controlling for baseline effortful control (i.e., trait-like) mediated the association between higher (or lower) levels of positive parenting given their baseline (i.e., trait-like) and child’s school performance. However, we did not find similar mediational effects of effortful control between positive parenting and child externalizing behavior.

Supplementary analyses

In addition to the models presented (see Figures 2 and 3), we also analyzed one model for child externalizing behavior and one model for child school performance each separately for mothers and fathers. For example, mother models included observational maternal parenting and mother reported child effortful control while the father only models included observational paternal parenting and father reported child effortful. We obtained similar results for the mother models as found with the original models, which included combined mother and father reported effortful control and equated mothers and fathers’ paths. However, we found differences in the father models compared to the original models where intraindividual changes (i.e., autoregressive associations) in father parenting were not significantly associated across time (b = .18, SE = .20) and effortful control at age 5 did not predict school performance at age 6 (b = .13, SE = .17). However, as explained in the main results sections these associations become significant once we used pooled variances by constraining the estimates to equality for mother and father paths. This simplifying constraint did not impair model fit (i.e., chi-square difference test). Furthermore, confidence intervals for the path from mother reported effortful control at age 5 to school performance at age 6 (b = .40, 95% CI = .14 ~ .66) were similar to the confidence interval for the path from father reported effortful control at age 5 to school performance at age 6 (b = .13, 95% CI = −.20 ~ .45). This also suggests some degree of caution when interpreting differences in the individual parent models. In short, we believe the interpretations from the constrained models in the previous section are on the strongest footing. Thus, the main findings of the present study that mother and father positive parenting at earlier time points predicted their child effortful control in later time points and the random intercept that effortful control predicted child outcomes at age 6 were consistent between the original models and the new individual parent models.

Discussion

The present investigation evaluated how mother and father positive parenting and effortful control were related over time from ages 3 to 5, and evaluated how aspects of parenting and effortful control were related to important developmental outcomes at age 6 in models with age 3 controls. These longitudinal associations between positive parenting and effortful control were evaluated with a longitudinal model that helped to distinguish between-person/parent differences from within-person variability – the random intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM; Hamaker et al., 2015). This is considered a potential advance over traditional cross-lagged models when studying reciprocal effects. Results are in line with the original Eisenberg et al. (1998) model of the Socialization of Emotion where parenting practices (positive parenting), informed by parent characteristics (sex) and cultural factors (gender stereotypes), related to emotion-related child socialization behaviors (effortful control, a temperamental characteristic contributing to emotion regulation), which in turn related to children’s developmental outcomes.

Several key results are worth emphasizing. First, both effortful control and positive parenting had appreciable levels of stability from one wave to the next when considering correlations across time. This is consistent with prior work (Tiberio et al., 2016). For example, effortful control at age 4 was strongly associated with effortful control at age 5 (r = .74). Positive parenting at age 4 was also associated with positive parenting at age 5 (r = .51 for mothers and r = .55 for fathers). The RI-CLPM provided additional insights into stability and suggested that within-child deviations from their baseline at a given wave were associated with within-child deviations at a future wave. Children who had particularly high (or low) levels of effortful control relative to their “trait-like” levels, also had relatively high (or low) levels at a subsequent wave. Similarly, both mothers and fathers who showed particularly high (or low) levels of positive parenting relative to their “trait-like” levels, also had relatively high (or low) levels at a subsequent wave.

In the current study, stable between-family variation in positive parenting was not associated with stable between-child variation in effortful control. This result should be replicated in future studies but could suggest that some of the association between these constructs in cross-sectional studies is likely due to associations between within-person (child and parent) deviations in effortful control and positive parenting. In terms of cross-lagged effects, there was an interesting pattern whereby within-child variability in effortful control was associated with prior levels of positive parenting but not vice versa. This suggests that fluctuations in effortful control from a child’s stable baseline are associated with parenting but within-family fluctuations in positive parenting are not consistently associated with prior fluctuations in effortful control. Thus, the current results could be taken to suggest the existence of parenting effects on effortful control but not vice versa. Again, the results should be replicated but such findings are consistent with Taylor, Eisenberg, Spinrad, and Widaman (2013) who found that intrusive parenting predicted subsequent levels of effortful control in childhood. Early childhood is a time where there is a rapid development of skills affiliated with effortful control, and the current findings suggest that parents may play a role in shaping within-child variability in such behavior during this developmental period. It is also important that future studies replicate the approach used in the current study especially with older children to determine whether this pattern is consistent across development. It might be that temperamental influences on parenting are easier to detect with older children and adolescents.

Further, results from the mediational analyses showed that within-family deviations in positive parenting at age 3 were eventually associated with child’s school performance through a complex pathway. This mediational pathway was independent of the statistical effect of trait-like levels of effortful control (i.e., random intercept) on school performance. This result implies that within-family deviations might have developmental implications for school performance. In contrast, we did not find evidence that trait-like levels of effortful control were associated with externalizing behavior at age 6 while including age 3 externalizing behavior. This result should be interpreted with some caution given the strong overlap between trait-like levels of effortful control and externalizing behavior at age 3. The association between these two variables might reflect some overlap in item content along with a stable association between effortful control and externalizing behavior. Previous research suggests that effortful control is an antecedent to externalizing problems so we are reluctant to conclude that effortful control is unimportant for externalizing problems based on these results. Instead we think it would be fruitful to apply the analytic strategy in this paper to other multi-method datasets.

In addition, we did not find evidence that within-person components of individual changes in parenting and effortful control predicted later externalizing behavior. This result is inconsistent with a number of studies that have found support for a mediational process of parenting, effortful control, and externalizing behavior (Chang et al., 2011; Eiden et al., 2007; Eisenberg et al, 2005; Sulik et al., 2015). However, many studies examine mother behavior or behavior of the primary caretaker, rather than examining mother and father separately in the model. It is also the case that Eisenberg et al. (2010) concluded the true underlying causal associations between parenting, effortful control, and child maladjustment might differ for children in the preschool years compared to those in older age groups. Thus, additional research is needed to determine if our result is a false negative or whether it is developmentally relevant.

Finally, a last result was that we could not reject a simple model that posited that processes involving effortful control and positive parenting operated similarly for mothers and fathers. This is consistent with Karreman, et al. (2010) who found that maternal and paternal parenting were both associated with child effortful control. It is important that future studies evaluate both mothers and fathers to determine when and if there are statistical differences in the patterns of association. Following the general gender similarities hypothesis (e.g., Hyde, 2014) or the idea that women and men are similar on many psychological variables, the baseline assumption would be these processes operate similarly for mothers and fathers. This is instantiated in our modeling approach which tested whether a less constrained model that freely estimated focal parameters for women and men fit appreciably better than a simpler model that constrained those parameters to the same values for women and men. In the current analyses, we could not reject the simpler model. We therefore tentatively conclude that the processes seem similar for mothers and fathers when it comes to the constructs we investigated. Nonetheless, higher-powered tests are needed before drawing strong conclusions and we think future studies should routinely include mothers and fathers to test for differences.

Limitations and Qualifications

Our conclusions are restricted by our research design using observer reports of positive parenting and parent reports of temperament. These are important caveats as the pattern of stability and cross-lagged relations might change as a function of measurement strategy. Age is another consideration given that our focus covered early childhood to the start of middle childhood. Tiberio et al. (2016) found that cross-lagged effects shifted from childhood to adolescence so this is important to test. It should also be acknowledged there may be alternative explanations for some of the findings. For example, it could be genetically influenced individual differences in children’s sensitivity or responsivity to parenting (Li et al., 2016) or shared genetic factors passed directly from parent to child help explain some of the associations. Smith et al. (2012) found that children’s DRD4 genotypes moderated the association between parenting and effortful control. Thus, future research should explore not only the importance of parenting and effortful control, but also how genetic factors influence such associations. We hasten to point out that Reuben et al. (2016) found that effortful control moderated the association between warm parenting and child externalizing behavior in a sample of adoptive families, so there is some support for environmental processes when considering the influence of parenting on child behavior.

Additional limitations of this study are worthy of comment. First, the sample was primarily white and came from the rural Midwest which could limit generalizability of the findings. Future research using more diverse samples is needed. Second, the data are correlational. In order to provide a more adequate test of model effects, quasi-experimental or experimental data are needed. It would be especially valuable to test whether parenting interventions have a lasting impact on effortful control.

Third, there are concerns with shared method variance for parent report of effortful control and the outcome variables. In addition, school performance was assessed via parent report rather than using objective tests of achievement. Therefore, results should be interpreted with some degree of caution. For example, findings could be due to shared reporter bias where effects are from parental perceptions of effortful control on parent reported outcomes rather than effortful control as reported by other raters or observed in standardized paradigms. It could be the case that parental perceptions of temperament are effectively driving the observed results. Indeed, the issue of parent report of temperament is relevant when considering the underlying processes. It might be the case that parental perceptions of temperament are a factor in how parents respond to children and eventually how children respond to their parents. More broadly, it is important to keep in mind how the nature of informants in any study generates methodological limitations that may also have substantive implications. Understanding how parents develop perceptions of their children and whether such perceptions have downstream implications for child development is an important avenue for future studies. Finally, a larger sample size is necessary to examine differences between mothers and fathers in relation to child gender. This would increase the understanding of how positive parenting and effortful control may operate differently for girls and boys.

Implications and Future Directions

The current results contribute to the existing literature about the transactional nature of temperament, parenting, and developmental outcomes in several ways. First, we found evidence that stable between-children differences in effortful control during the preschool years were associated with school performance at age 6. This general result was consistent with prior findings (e.g., Blair & Razza, 2007; Eisenberg et al., 2010; Feldmann et al., 1995; Hernández et al., 2017; Liew et al., 2008; Sánchez-Pérez et al., 2018). Such a result further underscores that individual differences in temperament have developmental consequences (Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Rothbart, 2007) and supports the continued emphasis on the relevance of effortful control for child development (e.g., Durbin, 2018). Of note, such results are consistent with findings in the adult personality literature pointing to the conclusion that between-person individual differences relate to a wide range of outcomes (e.g., Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007).

A second finding concerned associations between effortful control and parenting at the within-person level. Our conclusion that effortful control is a relatively stable attribute does not mean that it is an immutable characteristic or that effortful control is insensitive to contextual factors like parenting. The RI-CLPM results suggest that positive parenting was related to child effortful control across early childhood, whereas effortful control was not associated with later positive parenting when these constructs are modeled at the within-child and within-parent level. This result provides a lens to view ongoing debates about the interplay between parenting, temperament, and development outcomes and supports the key tenants of transactional perspectives on human development and Eisenberg’s et al. (1998) heuristic model of the socialization of emotion (see also Eisenberg et al., 2005). Parents who are positive and supportive of their children in stressful situations (like the puzzle task used here) may help children deploy attention and focus and reduce negative arousal. Such supportive parental practices may help children to constructively deal with their emotions and engage in successful coping (Eisenberg et al., 1998).

Moreover, parenting influences on developmental outcomes might operate, in part, through their impact on within-child processes related to self-regulation. That is, parents who are especially positive, who communicate, and exhibit patience with their children relative to a stable parenting “baseline” may help children develop greater effortful control relative to their stable individual differences in that construct. This suggests that parenting and temperament associations might occur in terms of within-parent and within-child processes. Such a finding attests to the importance of longitudinal data in developmental research and to the need for statistical models that isolate both between and within person (both parent and child) processes.

A related aspect of the importance of focusing on with-person processes is the direction of the cross-lagged statistical effects. We found indications for prospective positive parenting associations with subsequent measures of effortful control. This finding is consistent with results in the literature suggesting that individual characteristics of children and adolescents are responsive to parenting practices (e.g., Belsky et al., 2007; Brody & Ge, 2001; Cipriano & Stifter, 2010; Eisenberg et al., 2012; Spinrad et al., 2007; Tiberio et al., 2016). We believe the current results are intriguing but are cautious about drawing strong conclusions about the relative primacy of parenting and effortful control. We suspect such relationships are mutually reinforcing and hope future studies use different measures of parenting and older samples with the RI-CLPM. This approach may help to clarify the nature of the transactions between parenting and temperament.

In sum, we believe the current results highlight the value of longitudinal data and more advanced statistical models for helping to clarify transactions among temperament, parenting, and developmental outcomes. Indeed, we believe that understanding how effortful control can be fostered in children is an important topic (Durbin, 2018). The current work suggests that positive parenting may play a role in the development of effortful control when considering parental behavior that is especially positive (or negative) relative to baseline levels. We suspect that interventions that work to bolster positive parenting may have applied value when considering externalizing problems and school achievement. We also hope to see greater attention to both between-person and within-person processes when thinking about parenting behaviors and temperament as this level of analysis seems to bring research into closer alignment with the transactional perspectives on human development of the sort found in the theorizing of Eisenberg and her colleagues.

Acknowledgments

This research is currently supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (AG043599). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. Support for earlier years of the study also came from multiple sources, including the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD064687), National Institute of Mental Health (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, MH48165, MH051361), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05347), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD027724, HD051746, HD047573), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings.

Contributor Information

Tricia K. Neppl, Dept. of Human Development and Family Studies, Iowa State University, 4389 Palmer Suite 2356, Ames, IA 50011;.

Shinyoung Jeon, Early Childhood Education Institute, University of Oklahoma-Tulsa, 4502 E 41st St. Room 4201-G;.

Olivia Diggs, Dept. of Human Development and Family Studies, Iowa State University, 064 LeBaron Hall, Ames, Ames, IA 50011;.

M. Brent Donnellan, Dept. of Psychology, Michigan State University, 252C Psychology Building, East Lansing, MI 48824;.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2000). Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari A, & Crosnoe R (2015). Children’s elicitation of changes in parenting during the early childhood years. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 32, 139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pasco Fearon RM, & Bell B (2007). Parenting, attention and externalizing problems: Testing mediation longitudinally, repeatedly and reciprocally. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 1233–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01807.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D, & Willoughby MT (2016). On the practical interpretability of cross lagged panel models: Rethinking a developmental workhorse. Child Development, 88, 1186–1206. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Raver CC, & Berry DJ, & Family Life Project Investigators. (2014). Two approaches to estimating the effect of parenting on the development of executive function in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 50, 554–565. doi: 10.1037/a0033647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, & Razza RP (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78, 647–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, & Ge X (2001). Linking parenting processes and self-regulation to psychological functioning and alcohol use during early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology, 15, 82–94. 10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage Focus Editions, 154, 136–136. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM (2005). Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 28, 595–616. 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, & Sexton HR (2011). Child effortful control as a mediator of parenting practices on externalizing behavior: Evidence for a sex-differentiated pathway across the transition from preschool to school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 71–81. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9437-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano EA, & Stifter CA (2010). Predicitng preschool effortful control from toddler temperament and parenting behavior. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 221–230. 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, & Dunn L (1981). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test - Revised manual for Forms L and M. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, & Dunn LM (1997). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (3rd ed.). Bloomington, MN: Pearson Assessments. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, & Strycker LA (2013). An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling: Concepts, issues, and application. Routledge Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Durbin CE (2018). Applied implications of understanding the natural development of effortful control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27, 386–390. 10.1177/0963721418776643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, & Leonard KE (2007). A conceptual model for the development of externalizing behavior problems among kindergarten children of alcoholic families: role of parenting and children’s self-regulation. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1187–1201. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, … & Guthrie IK (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72, 1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, & Reiser M (1999). Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development, 70, 513–534. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, & Eggum ND (2010). Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 495–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Eggum ND, Silva KM, Reiser M, Hofer C, … & Michalik N (2010). Relations among maternal socialization, effortful control, and maladjustment in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 507–525. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Cumberland A, Shepard SA, … & Thompson M (2004). The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s resiliency and adjustment. Child Development, 75, 25–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00652.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Taylor ZE, Widaman KF, & Spinrad TL (2015). Externalizing symptoms, effortful control, and intrusive parenting: A test of bidirectional longitudinal relations during early childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 27, 953–968. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Vidmar M, Spinrad TL, Eggum ND, Edwards A, Gaertner B, & Kupfer A (2010). Mothers’ teaching strategies and children’s effortful control: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1294–1308. doi: 10.1037/a0020236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Spinrad TL, Valiente C, Fabes RA, & Liew J (2005). Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development, 76, 1055–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00897.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elam KK, Chassin L, Eisenberg N, & Spinrad TL (2017). Marital stress and children’s externalizing behavior as predictors of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 1305–1318. 10.1017/S0954579416001322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann SC, Martinez-Pons M, & Shaham D (1995). The relationship of self-efficacy, self-regulation, and collaborative verbal behavior with grades: Preliminary findings. Psychological Reports, 77, 971–978. [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, Sumida E, McCann C, Winstanley M, Fukui R, Seefeldt T, & Moore D (2003). The transition to parenthood among young African American and Latino couples: Relational predictors of risk for parental dysfunction. Journal of family Psychology, 17, 65–79. 10.1037/0893-3200.17.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganiban JM, Ulbricht J, Saudino KJ, Reiss D, & Neiderhiser JM (2011). Understanding child-based effects on parenting: temperament as a moderator of genetic and environmental contributions to parenting. Developmental Psychology, 47, 676–692. doi: 10.1037/a0021812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann K, Grossmann KE, Kindler H, & Zimmermann P (2008). A wider view of attachment and exploration: The influence of mothers and fathers on the development of psychological security from infancy to young adulthood In Cassidy J & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 857–879). New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gryczkowski M, Jordan SS & Mercer SH (2018). Moderators of the relations between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting practices and children’s prosocial behavior. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 49, 409–419. 10.1007/s10578-017-0759-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaker EL, Kuiper RM, & Grasman RP (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20, 102–116. 10.1037/a0038889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández MM, Valiente C, Eisenberg E, Berger RH, Spinrad TL, VanSchyndel SK, Silva KM, Southworth J, & Thompson MS (2017). Elementary students’ effortful control and academic achievement: The mediating role of teacher-student relationship quality. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 40, 98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML (2000). Empathy and moral development: Implications for caring and justice Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Coventional criteria versus new alternatives, Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JS (2014). Gender similarities and differences. Annual review of psychology, 65, 373–398. Doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karreman A, van Tuijl C, van Aken MAG, & Deković M (2010). Parenting, coparenting, and effortful control in preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 30–40. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, & Knaack A (2003). Effortful control as a personality characteristic of young children: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Personality, 71, 1087–1112. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopystynska O, Spinrad TL, Seay DM, & Eisenberg N (2016). The interplay of maternal sensitivity and gentle control when predicting children’s subsequent academic functioning: Evidence of mediation by effortful control. Developmental Psychology, 52, 909–921. doi: 10.1037/dev0000122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME (Ed.). (2004). The role of the father in child development. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lee EH, Zhou Q, Eisenberg N, & Wang Y (2012). Bidirectional relations between temperament and parenting styles in Chinese children. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 37, 57–67. doi: 10.1177/0165025412460795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ (2006). Growth in temperament and parenting as predictors of adjustment during children’s transition to adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 42, 819–832. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Grining CP (2007). Effortful control among low-income preschoolers in three cities: Stability, change, and individual differences. Developmental Psychology, 43, 208–221. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Sulik MJ, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Lemery-Chalfant K, Stover DA, & Verrelli BC (2016). Predicting childhood effortful control from interactions between early parenting quality and children’s dopamine transporter gene haplotypes. Development and Psychopathology, 28, 199–212. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew J, McTigue EM, Barrois L, & Hughes JN (2008). Adaptive and effortful control and academic self-efficacy beliefs on achievement: A longitudinal study of 1st through 3rd graders. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 515–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD, Book R, Rueter M, Lucy L, Repinski D, et al. (1998). The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (5th ed.): Iowa State University: Institute for Social and Behavioral Research. [Google Scholar]

- Neppl TK, Donnellan MB, Scaramella LV, Widaman KF, Spilman SK, Ontai LL, & Conger RD (2010). Differential stability of temperament and personality from toddlerhood to middle childhood. Journal of research in personality, 44, 386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK & Muthén BO (2012). Mplus User’s Guide. Fifth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette D (2004). Theorizing the father-child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Human Development, 47, 193–219. doi: 10.1159/000078723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, & Masciadrelli BP (2004). Paternal involvement by U.S. residential fathers: Levels, sources, and consequences In Lamb ME (Ed.), The role of the father in child development, 4th ed. (pp. 222–271). New York: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC (2004). Placing emotional self-regulation in sociocultural and socioeconomic contexts. Child Development, 75, 346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00676.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]