Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: discoverability, readership, scientific communication, scientific impact

Abstract

Publishing the results of scientific research is more than a personal choice; it is an ethical and increasingly regulatory obligation. It is generally accepted that top-ranking journals attract wider audiences than specialist publications and scientists have long recognised that the importance of targeting so-called high impact journal in getting their work noticed. However, gaining access to top-flight journals is difficult and a broader exposure is not necessarily guaranteed. Huge competition exists for attention within the scientific literature. Traditionally, scientists have viewed promoting their own research as somewhat self-serving and gauche, preferring its value to speak (passively) for itself. However, times have changed. Researchers can now be divided into two camps: those who see publication of their research as the final step in the process and those who see it as the first step in sharing their findings with the wider world. We summarize here 10 considerations for peri-publication activities that, when used in the right measure and appropriately to the work involved should aid those looking to increase the discoverability, readership and impact of their scientific research. The internet has transformed scientific communication. If you ignore this development, it is possible that your research will not get the recognition it deserves. You need to identify the specific issues to focus on (scope) and how much effort (resource) you are prepared to commit.

Video abstract: http://links.lww.com/CAEN/A22.

Introduction

Publishing the results of scientific research is more than a personal choice; it is an ethical and increasingly regulatory obligation [1]. Research study audits indicate that less than half of all research is ever published and this may go some way to explaining why up to 80% or reported results are not reproducible [2]. Human and animal research is only justified when the knowledge gained is shared with the scientific community and made available for all [3].Reporting is doubly mandated when research involves human participants or is funded through charitable donations or public funds. Grant providing bodies must demonstrate knowledge returns on their investments. Requests for funding now often require investigators to provide details of how investigators intend to disseminate their findings and establish a lasting legacy for the work they fund. Furthermore, academic career progression is increasingly dependent on both journal and individual publication metrics. We must therefore infer that it is somewhat irresponsible to leave wider recognition of your findings to serendipity [4].

It is generally accepted that top-ranking journals attract wider audiences than specialist publications and scientists have long recognized that the importance of targeting so-called high impact journal in getting their work noticed [5]. However, gaining access to top-flight journals is difficult and a broader exposure is not necessarily guaranteed. Huge competition exists for attention within the scientific literature, with more than 2.5 million new items being added each year [6]. We are also bombarded with news articles, e-newsletters, blogs, podcasts, videos, etc. Even with powerful online search engines, it is getting harder for scientists to keep up to date and for authors to get their voices heard.

Traditionally, scientists have viewed promoting their own research as somewhat self-serving and gauche, preferring its value to speak (passively) for itself. However, times have changed. Scientists need to grasp the concept of ‘share of voice’ and engage in activities that aid in increasing the profile of their work to gain appropriate recognition. Many authors appreciate that a robust process of dissemination after publication builds stronger scientific reputations and increases opportunities for future support [7]. Researchers can now be divided into two camps: those who see publication of their research as the final step in the process and those who see it as the first step in sharing their findings with the wider world.

We summarise here 10 considerations for peri-publication activities that when used in the right measure and appropriately to the work involved should aid those looking to increase the discoverability, readership and impact of their scientific research. Although our perspective is primarily from the standpoint of medical science, we believe the principles are transferable across all research disciplines.

Rule 1: work with dissemination in mind

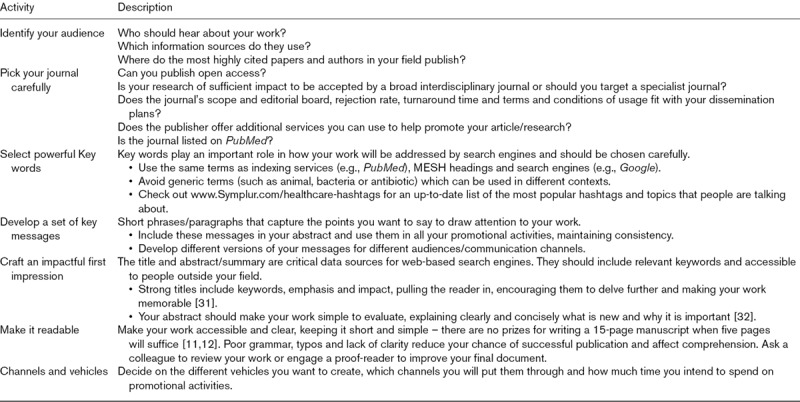

The best advice we can give scientists is contained within Rule #1 of the 2015 Ten Simple Rules article on online outreach [8]. Stop viewing research and dissemination of your findings as two separate activities. Substantial groundwork can be done while preparing manuscripts for publication to identify and create materials you can use in promoting your research to a wider audience (Table 1). Aim to exploit these materials. Adopt a reuse, recycle, repurpose and retarget mind-set if you don’t want your work to become ‘tomorrow’s fish-n-chips paper’. Succinct and articulate writing that complies with the target journal’s ‘guidelines to authors’ using a clear style, with accurate spelling and the correct use of grammar (preferably avoiding jargon) is more likely to be published. Careful consideration needs to be given to your titles and abstracts as they are often the only parts of a paper featured on webpages or accessible to search engines [9,10]. Most journals request that authors keep their submissions concise; however, it seems that longer articles tend to get more citations [11,12]. It should be noted that bibliographic studies can only review data from published articles (i.e., after authors have adhered to any length restrictions) and increasingly journals limit both length of submissions and number of references.

Table 1.

Summary of prepublication activities in preparation for promotion

You should consider first sharing any findings you mights later publish at a relevant scientific conference, both posters and oral presentations are appropriate as both are increasingly discoverable electronically after the event. Writing a review article based on your work and putting it in context with the field is also useful as many scientists discover primary research in review articles. Consider contextualizing your findings in narrative reviews, systematic literature summaries and meta-analyses, noting their respective strengths and weaknesses.

Few researchers have unlimited access to pay-to-view resources. Accessibility is possibly the greatest single factor affecting dissemination [13]. If possible (and in line with your budget), publish your article as ‘open access’ as researchers with limited resources will always select (and cite) the open-access option first compared with any ‘pay-to-view’ article. A manuscript has to promise significant value before an investment of $30+ can be justified. Furthermore, open-access electronic journals may be better than traditional publications where wider dissemination is required. Be aware of the difference between ‘open-access’ and ‘free-to-access’ publication policies; the former will usually involve a fee (which could be $2–3000), whereas the latter does not require payment for publication.

Rule 2: deploy preprints

A preprint is a full draft of a research paper that is shared publicly before it has been peer reviewed. Preprints are frequently given a digital object identifier so they can be cited. Scientists in physics and maths have long embraced electronic preprints, but only with the introduction of bioRxiv in 2013 (https://www.biorxiv.org) did the life sciences get its own preprint service. Although some researchers continue to have concerns about preprints, they continue to become more popular [14]. By posting a citable preprint with your research results, you can firmly stake claim to your work. Other researchers can discover your work sooner, potentially point out critical flaws or errors and suggest new studies or add data that strengthen your argument. They can even suggest a collaboration that will lead to publication in a more prestigious journal. The issue of targeting journal submission has been covered elsewhere [15], but it is well recognized that libraries generally carry well known journals (or publisher journal catalogues) and that external institutions or researchers not necessarily knowledgeable about the details of a field are more impressed by publication in a prestigious journal. Preprints and infrastructure link providers (e.g., CrossRef, https://www.crossref.org) can bring new readers to your published paper. Attention scores that capture mentions on social and other media are higher when preprint servers are used as they increase the chance of work being discovered [16].

Rule 3: exploit the journal’s resources

Most publishers provide guidance and support to help people find, read, comment and ultimately cite publications that appear in their journals. These might include Really Simple Syndication feeds linking to newly published material and customized links that (may even) provide free access to your article. Journal newsletters and ‘table of contents’ alerts forward updates on your paper to interested colleagues. Some publishers/journals encourage authors to provide/create additional materials to entice readers to ‘dig deeper’. These can include microblogs, interviews or Twitter summaries. The value of journal add-on services will depend on the amount of promotion you expect to undertake once your work is published. Plan how you can best make use of each of these services while your manuscript is undergoing editorial review. Providing detailed protocols, checklists or primary data used in your research not only promotes more reproducible science, but also draws additional attention and encourages citations.

Rule 4: liaise with your institution

Academic and commercial institutions are eager to promote any successful research being conducted by their scientists. Inform your institution’s press office or public relations team of any pending publications. Ask if they would be interested in developing a press release or a summary of your work to be included on their website or within in-house publications. Alert the publisher’s social media managers/public relations team if your institution plans to produce a press release as they may want to work with it to maximize efforts to draw attention to the article (and institution) and coordinate timings (and possible news embargos) prior to release. Most organizations often have a repository where you can post your publication and this will improve accessibility. Make sure that you have the right permissions (particularly related to copyright restrictions) to post your article. Keep any materials or content linking to your manuscript fresh. For example, ensure that your professional profile on your institution’s website or on professional social media sites is up to date and includes a description of your current activities, past successes and any awards.

Rule 5: access your networks

Coworkers, colleagues and peers are the easiest audience to access. E-mail your wider network, telling them about your publication and providing a link to the article. Ask colleagues to share the news of your publication [10]. You might also want to use the timely opportunity of publication to reach out to others in your field with whom you do not currently collaborate. Many disciplines have active scientific communities, where involvement will extend your network of potential ‘readers’ eager to discuss or cite your findings [17]. Encourage readers to comment on your work if they spot errors or ambiguities – perhaps in a ‘letter to the editor’ – any resulting discussion within the literature will serve to correct any erroneous messages and further boost your profile. For a time, you may want to add a web link to your manuscript to your e-mail signature. This will keep your success fresh in people’s minds. Ensure your research partners understand the importance of promotion and their role in it, so they are prepared to ‘echo’ your own activities. If you are a member of a professional society, you should ask if they would be interested in commenting on your findings in newsletters and/or alerts. You should exploit all possible opportunities to promote your work at scientific/professional conferences, citing your work in posters, presentations and ‘echo’ communications; and do not forget to mention your work when talking with colleagues at the bar. Even in this digital age, face-to-face meetings remain powerful and are less subject to electronic noise. They provide the greatest opportunity to convince others to value your work and share your passion. Create and learn elevator pitches to communicate your point quickly.

Rule 6: engage with scholarly collaboration to extend your reach

Sharing your research accomplishments through scholarly networks is an excellent way to increase your reach and raise your visibility. Create an Open Research and Contributors ID (ORCiD) account (https://orcid.org), ORCiD provides a persistent digital identifier that distinguishes you from other researchers and, through integration in key research workflows such as manuscript and grant submissions, supports automated linkages between you and your professional activities. You may choose to post your article’s research data on community-recognized repositories or to general-science repositories [e.g., Figshare (https://figshare.com) and the Dryad Digital Repository (https://datadryad.org)]. Recommendations suggest that, where possible, data should be submitted to discipline-specific, community-recognized repositories or generalist repositories if no suitable community resource is available [18]. There is a lively ongoing discussion over whether sharing scientific data brings any clear benefit to authors [19]. Whatever the requirement of your granting agency, data sharing has the potential to raise awareness about your research, perhaps opening the door to new collaborative projects. Other options to record your successes and maintain your professional visibility include online resources like ResearchGate, Mendeley and LinkedIn (Box 1). Use these resources to create links with colleagues and peers to extend your network and keep the information on projects and research up to date. GitHub repositories are freely visible to all; they provide developers and researchers with a dynamic and collaborative environment, often referred to as a social coding platform, which supports peer review, commenting and discussion. Many share their work publicly and openly from the start of the project in order to attract visibility and to benefit from early contributions from online communities. This service is catching on with the life sciences community [20].

Box 1.

Online academic databases

Rule 7: enrich your content

Traditional publishing, scholarly networks and academic forums use standard journal content when sharing information. This might appear in the form of a summary or abstract, the publication’s title or a figure from the manuscript describing your data. These dry, academic descriptions need to be ‘enriched’ when you are seeking to engage broader audiences. Create different ‘vehicles’ that can communicate your message on various levels. Writing a compelling plain language summary or short ‘call-outs’ that can pique curiosity. Some journals include such summaries and publish them in parallel with your scientific abstract (in some cases, it is mandatory). You might consider using Google Translate to increase the accessibility of a summary by providing it in different languages if your work has international implications. Alternatively, compose an article for use on nonacademic communication channels on how your work fits with current thinking.

Multimedia (podcasts, videos, slides, etc.) adds a new dimension to your research. Many publishers and journals encourage authors to create/provide supporting multi-media materials to accompany their manuscripts. Correlations exist between the number of views of a video abstract gets and article accessions [21]. A graphical summary (e.g., a visual abstract, infogram, photograph or cartoon) will significantly boost engagement through online resources. You can combine a plethora of resources on free web-based outreach services like Kudos (www.growkudos.com). Consider preparing a press release and submitting it to various news outlets – but remember that there is no certainty that your story will be reported. Consider making podcasts for release on YouTube or Vimeo. YouTube is the world’s second biggest search engine and can be an untapped source of traffic – with over 30 million visitors per day. All of these, if successful, will greatly increase your readership, both within academia and beyond.

Rule 8: use Twitter and social media

Twitter and social networks are rich and reliable channels for exchanging highly specialised information. Twitter plays a significant role in scholarly information and cross-disciplinary knowledge-sharing and also contributes to the nonacademic impact of scholarly research [22]. It is an excellent dissemination tool, but it is not a passive medium. Twitter requires you to generate an audience by engaging with the ‘community’ and maintaining their interest while establishing your specific credentials. Success requires you to interact with your peers (following them and hopefully being followed back), regularly tweeting and retweeting items of interest and getting involved with Twitter ‘lists’ and ‘tweet chats’. Your goal is to build an audience of avid followers eager to receive your tweets – ready for the day when you have work of your own to tweet about. Then hook your audience with a tweet of 280 characters or less and a mouth-watering image – directing them to your publication.

Sharing a link to your newly published manuscript, webpage, tweet or blog via social media helps generate further interest in your article. You can start simply by using your own social media account, for example, linking your article on your Facebook page (www.facebook.com) [22,23], or adding references on your LinkedIn profile (www.linkedin.com) [24]. There may be other social media platforms worth investigating that could contribute in efforts to extend the reach of your work (e.g., Instagram, Snapchat, Pinterest, Reddit, etc.).

A nontechnical summary of your research paper is often a great ‘share’ for social media and news websites. These activities will drive those within your social network to your article. Ensure you comment on other posts, and include links to other blogs, etc., to demonstrate that you are an active participant rather than just trying to exploit the medium for advertising. If you collaborate with other scientists and possibly patient groups, you may want to consider starting your own specialist forum or joining one. The more ambitious social media-minded researcher can try to build an audience by becoming a curator and distributor of key information for their field. Manually searching out relevant content to publish across multiple channels can be time consuming but can be augmented by automation software to assemble tweets, etc., which they can then be posted in blogs and on social media as topical science stories, conference reports, etc. For example, it is relatively simple to create a free newsletter service providing regular posts through Nuzzel (https://www.nuzzel.com).

Rule 9: create a website and/or blog

As a researcher, you will have both a vision and an opinion. Traditional scientific channels are conservative in the forum they offer for explaining or expanding on the meaning of your research, particularly with general audiences, or for speculating on its broader value. Academic publishing is relatively slow and incapable of contextualising your work with regards to ongoing developments. In contrast, blogs and self-run websites are good at introducing new research, conversations and initiating new collaborations. A blog or website provides the freedom to develop a backstory for your work; show your expertise and describe the time and effort that has gone into achieving your findings. They can serve as a good information resource to ‘point at’ when communicating via other channels (Twitter, LinkedIn or e-mails); and can be useful if your publication is locked behind paywalls. When commenting on your work, remember to create a compelling title or headline – think of these as calls-to-action to drive people to read your post. As well as summarizing the content, your title should include key words and hashtags.

You cannot be certain that an established reputation will ensure the reach of your research and you should, therefore, be actively involved in a process of building that reputation [25]. Do not wait to be asked for a contribution, get involved in discourse in your scientific community; the smooth running of many organisations relies on volunteers [17]. For example, engage with your society or find out if there is a Wikipedia page about your research topic, contribute to the content (Wikipedia has many guidelines for writing an entry, so check its website for details) [26].

Rule 10: track your activity

Promoting your research requires investment of your time and resources and you need to track which activity has the greatest effect on the reach, impact and legacy of your research so that you can focus your efforts. The journal impact factor and h-index are the best-known indicators of impact but these statistics are based on citation analysis and have attracted criticism [27]. The data lack immediacy – taking months to years to provide any clear assessment of quality or value. Scholars need to carefully balance a journal’s stature, as measured by its impact factor, with the need for a wide readership. One alternative might be to consider targeting a journal that cuts across traditional scientific boundaries. Cardiometabolic medicine is a good example where emerging therapies for glucose management interest not only diabetes and endocrinology communities but also cardiologists, renal physicians, not to mention primary care [28].

Altmetrics or article-level metrics complement traditional citation impact metrics and are a way to track in real time the attention and conversations around individual items. They gather data from a variety of online sources (including social media, blogs and news outlets) and give a measurement of digital impact and reach. Altmetrics measure ‘Attention’ – whether good, bad or simply ridiculous. Some of the highest Altmetric attention scores are associated with popularist, general interest or even fictitious articles that rightly or wrongly capture the attention to the public. Various publishing houses (Wiley, Elsevier, etc.) provide access to altmetric data as do some independent service providers. Funders (including the UK Medical Research Council) have started showing interest in these metrics [29]. It is now possible to determine whether a specific activity boosts your altmetrics score. Many publisher platforms such as PLoS, ScienceDirect and Nature Publishing Group, as well as software tools like the Altmetric bookmarklet provide article usage reports. You can also track traffic to your website/blog using Google Analytics. Ensure your website/blog is optimized for search engines – use keywords, MESH headings and text in metadata to attract views through search sites.

Conclusion

The internet has transformed scientific communication. If you ignore this development, it is possible that your research will not get the recognition it deserves. You need to identify the specific issues to focus on (scope) and how much effort (resource) you are prepared to commit. Accept that you do not need to promote your article on every single social media outlet or channel. You will benefit from knowing ‘Who’ and ‘Where’ to target your efforts. Find out how your articles are being read, shared and cited. Even a small amount of self-promotion in the right areas will have a significant impact, making you more discoverable. Once you have set yourself up, you can easily manage your profile by performing a few activities for 10–15 min every week.

The conventional wisdom on scientific communication may need to be jettisoned. ‘Click bait’ websites clearly tap the depths of the human psyche, creating compelling, ‘click me’ headlines for exploitation on social media. The marketing analytical site Buzz Sumo studied the 100 million headlines that generated the most engagement on Facebook and Twitter in terms of ‘likes’, ‘shares’, clicks and comment [30]. As a species, we cannot resist a list: ‘X reasons why…’ and ‘X things you can …’ are the most effective phrases to gain traction online. The study showed 5, 10 and 15 are the most click-worthy numbers. The most powerful three-word phrase for use anywhere in a headline or title was ‘will make you …’. Make of that what you can.

The lasting value of the various new communication/dissemination channels is presently unclear. The adoption of Twitter is having a measurable effect on individual scientific reputations, even if the jury is still out on a correlation between Tweets and citations [31]. A high Altmetric score is not always a true indicator that your article has made a significant impact on the science or in your area of study – just as is the case for traditional bibliographic statistics [32].

Sharing research, accomplishments and ambitions with a wider audience makes you more visible in your field [5,33]. This helps you get cited, cultivates your reputation, promotes your research and your career [6]. The history of science is critically related to the promotion of its findings. Where once we had the Lunar (or Royal) Society, nowadays we have the internet and its resources. Plus ça change plus c’est la meme chose (Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, Les Guêpes, 1849).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the many academic partners they have worked with over the years who have taught them that, where the promotion of science is concerned, ignorance is bliss. The authors would also like to thank Daniel Hyde from Wolters Kluwer for generously sharing his insights.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.cardiovascularendocrinology.com.

References

- 1.World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Ferney-Voltaire France. World Medical Association; https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects. [Accessed on 30 July 2019] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker M. Biotech giant publishes failures to confirm high-profile science. Nature. 2016; 530:141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical?. JAMA. 2000; 283:2701–2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Union. Horizon 2020 Rules of Participation. European Union; http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/legal_basis/rules_participation/h2020-rules-participation_en.pdf. [Accessed on 30 July 2019] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harley D, Acord SK, Earl-Novell S, Lawrence S, King C.Assessing the future landscape of scholarly communication: an exploration of faculty values and needs in seven disciplines. 2010. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/15x7385g. [Accessed on 27 March 2019]

- 6.Ware M, Mabe M. The STM report. An overview of scientific and scholarly journal publishing. 2015, Hague, The Netherlands: International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamali HR, Nicholas D, Herman E. Scholarly reputation in the digital age and the role of emerging platform sand mechanisms. Res Evaluat. 2016; 25:37–45 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bik HM, Dove AD, Goldstein MC, Helm RR, MacPherson R, Martini K, et al. Ten simple rules for effective online outreach. PloS Comput Biol. 2015; 11:e1003906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annesley TM. The title says it all. Clin Chem. 2010; 56:357–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Annesley TM. The abstract and the elevator talk: a tale of two summaries. Clin Chem. 2010; 56:521–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox CW, Paine CET, Sauterey B. Citations increase with manuscript length, author number, and references cited in ecology journals. Ecol Evol. 2016; 6:7717–7726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falagas ME, Zarkali A, Karageorgopoulos DE, Bardakas V, Mavros MN. The impact of article length on the number of future citations: a bibliometric analysis of general medicine journals. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e49476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norris M, Oppenheim C, Rowland F. The citation advantage of open-access articles. J Assoc Inf Sci Tech. 2008; 59:1963–1972 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdill RJ, Blekhman R. Tracking the popularity and outcomes of all bioRxiv preprints. Elife. 2019; 8:e45133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardman TC, Serginson JM. Ready! Aim! Fire! targeting the right medical science journal. Cardiovasc Endocrinol. 2017; 6:95–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serghiou S, Ioannidis JPA. Altmetric scores, citations, and publication of studies posted as preprints. JAMA. 2018; 319:402–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michaut M. Ten simple rules for getting involved in your scientific community. PloS Comput Biol. 2011; 7:e1002232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anonymous. Research data policies: recommended data repositories. 2019, London UK: SpringerNature; https://www.springernature.com/gp/authors/research-data-policy/repositories/12327124. [Accessed on 30 July 2019] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linek SB, Fecher B, Friesike S, Hebing M. Data sharing as social dilemma: influence of the researcher’s personality. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0183216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez-Riverol Y, Gatto L, Wang R, Sachsenberg T, Uszkoreit J, Leprevost Fda V, et al. Ten simple rules for taking advantage of git and github. PloS Comput Biol. 2016; 12:e1004947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spicer S. Exploring video abstracts in science journals: an overview and case study. J Librarianship Scholar Commun. 2014; 2:eP1110 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammadi E, Thelwall M, Kwasny M, Holmes KL. Academic information on twitter: a user survey. PLoS One. 2018; 13:e0197265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seidel RL, Jalilvand A, Kunjummen J, Gilliland L, Duszak R., Jr Radiologists and social media: do not forget about Facebook. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018; 15:224–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Lange C. Naturejobs [Internet]. 2012, London, UK: Nature; http://blogs.nature.com/naturejobs/2012/12/20/linkedin-tips-for-scientists/. [Accessed on 27 Mar 2019] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bourne PE, Barbour V. Ten simple rules for building and maintaining a scientific reputation. PloS Comput Biol. 2011; 7:e1002108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourne PE. Ten simple rules for getting ahead as a computational biologist in Academia. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011; 7:e1002001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moustafa K. Aberration of the citation. Account Res. 2016; 23:230–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krentz AJ, Chilton R. Cardioprotective glucose-lowering medications: evidence and uncertainties in a new therapeutic era. Cardiovasc Endocrinol Metab. 2018; 7:2–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viney I. Altmetrics: research council responds. Nature. 2013; 494:176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rayson S. We analysed 100 million headlines. Here’s what we learned (new research). 2017, Brighton, East Sussex, UK: BuzzSumo; http://buzzsumo.com/blog/most-shared-headlines-study/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eysenbach G. Can tweets predict citations? Metrics of social impact based on Twitter and correlation with traditional metrics of scientific impact. J Med Internet Res. 2011; 13:e123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwok R. Research impact: altmetrics make their mark. Nature. 2013; 500:491–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anonymous. Toot your horn – An Insider’s Insight into self-promotion and dissemination activities. 2016, London UK: Niche Science & Technology Ltd; http://www.niche.org.uk/asset/insider-insight/Insider-Toot-your-horn.pdf. [Accessed on 27 Mar 2019] [Google Scholar]