Abstract

Marriage protects against loneliness, but not all marriages are equally protective. While marriage is a highly interdependent relationship, loneliness in marital dyads has received very little research attention. Unlike most studies proposing that positive and negative marital qualities independently affect loneliness at the individual level, we used a contextual approach to characterize each partner’s ratings of the marriage as supportive (high support, low strain), ambivalent (high support, high strain), indifferent (low support, low strain), or aversive (low support, high strain), and examined how these qualities associate with own and partner’s loneliness. Using couple data from the Wave II National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (N=953 couples), we found that more than half of the older adults live in an ambivalent, indifferent, or aversive marriage. Actor-partner interdependence models showed that positive and negative marital qualities synergistically predict couple loneliness. Spouses in aversive marriages are lonelier than their supportively married counterparts (actor effect), and that marital aversion increases the loneliness of their partners (partner effect). In addition, wives (but not husbands) in indifferent marriages are lonelier than their supportively married counterparts. These effects of poor marital quality on loneliness were not ameliorated by good relationships with friends and relatives. Results highlight the prominent role of the marriage relationship for imbuing a sense of connectedness among older adults, and underscore the need for additional research to identify strategies to help older adults optimize their marital relationship.

Keywords: Actor-Partner Interdependence Model, Ambivalence, Dyadic Data Analysis, Gender, Indifference, Loneliness, Marital Quality

Being married protects against loneliness, a finding that has been replicated in many cultures and countries (Stack, 1998). In older age, when family members, friends, and neighbors are lost to death and geographic relocation, the marital partner becomes increasingly important in maintaining a sense of social connectedness (de Jong Gierveld, Broese van Groenou, Hoogendoorn, & Smit, 2009; Dykstra & de Jong Gierveld, 2004; Pinquart, 2003; Tornstam, 1992). Nevertheless, about 1 in 6 older married men and women report moderate or intense feelings of loneliness (de Jong Gierveld & Broese van Groenou, 2016). Among the factors that contribute to loneliness in the older adult marriage, the quality of the marriage relationship looms large (de Jong Gierveld et al., 2009; Warner & Kelley-Moore, 2012). For instance, past research has shown that marriage is associated with reduced loneliness only to the extent that the marital partner serves as a confidant (Hawkley et al., 2008). Such findings are consistent with the definition of loneliness as a subjective state of perceived isolation in which one’s relationships are viewed as inadequate not simply in number but particularly in quality (Peplau & Perlman, 1982).

Marriage is a highly interdependent relationship, and each individual’s perceptions, preferences, behaviors, and emotions contribute not only to their own marital experience, but also color the marital experience of the partner. To date, however, loneliness in marital dyads has received very little research attention. One recent exception (Moorman, 2015), a study of older adults in the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP), showed that perceiving stronger positive spousal qualities was as highly inversely associated with the spouse’s loneliness as with one’s own loneliness. In addition, perceiving stronger negative spousal qualities was associated with higher loneliness in oneself but was unexpectedly associated with lower loneliness in the spouse.

What this and other studies have not examined is whether the particular combination or balance of positive and negative qualities in the marriage is reciprocally influential for the loneliness of each partner in the marriage. The present study explores how positive and negative qualities (i.e., spousal support and strain) combine to produce marriages that can be characterized as supportive, ambivalent, indifferent, and aversive, and how these marriage types differentially affect each partner’s loneliness in an older adult marriage. In addition, we examine whether the quality of each partner’s relationships with friends and relatives buffer the effect of his/her marriage type on his/her loneliness. Finally, because prior research has shown that men and women differ in their appraisals of marital quality and in the effect of marital quality on outcomes, we test for gender differences in all the above dyadic associations. We do so drawing from a nationally representative sample of older adults, a segment of the population that is growing and in which, accordingly, the number of marriages that continue into old age is increasing.

Marital quality and loneliness in later life

Marital quality tends to deteriorate with marital duration (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Chen, & Campbell, 2005), and this effect is explained, at least in part, by life circumstances and events. For instance, declines in one’s own and particularly in one’s spouse’s health have been associated with declines in marital quality (Wong & Hsieh, 2017; Yorgason, Booth, & Johnson, 2008). Disability has been associated with loneliness in one or both partners (Korporaal, Broese van Groenou, & van Tilburg, 2008). In other circumstances, older marital partners may experience the strain of a small and shrinking social network that leaves them more reliant on each other, with little or no buffering social relationships to minimize their experience of negativity in the marriage. The immediate post-retirement years have been characterized as more conflict-ridden in part due to changing social roles and fewer social interaction opportunities that could buffer marital strain (Moen, Kim, & Hofmeister, 2001). In addition, age-related cognitive changes can impair inhibitory and perspective-taking abilities, and the resulting adverse effect on social skills can damage relationship quality (Smith & Baron, 2016). In sum, social and health transitions in older age can increase stress and diminish marital quality, leaving the door open to feelings of disconnectedness, isolation, and loneliness.

Marital quality has in fact been associated with loneliness. Partners in marriages characterized by lower cohesion (i.e., a lesser degree of communication and emotional intimacy) are lonelier than those in more cohesive relationships (Olson & Wong, 2001). De Jong Gierveld et al. (2009) found that older adults who could not count on the emotional support of their spouse, and those spouses who were frequently in disagreement, were lonelier. Other research has taken a bi-dimensional approach that considers positive and negative marital characteristics as separate and independent sources of information about the quality of the marital relationship (Fincham & Rogge, 2010; Smith & Baron, 2016; Uchino, Holt-Lunstad, Uno, & Flinders, 2001). For instance, positive and negative marital quality scores predicted reports of relationship behaviors and attributions over and above the effect of a bipolar global measure of marital quality (Fincham & Linfield, 1997). Likewise, positive and negative social exchanges (e.g., supportive and insensitive, respectively) have been independently related to loneliness in married older adults (Liu & Rook, 2013), as have spousal support and spousal strain (Ayalon, Shiovitz-Ezra, & Palgi, 2013).

Marital quality is characterized not only by the independent effects of positivity and negativity, but also by their joint effects. Positive and negative spousal qualities are contextualized such that the impact of positivity depends on the co-occurrence of negativity and vice versa. Importantly, marital types defined by combinations of positive and negative characteristics are not reducible to interactions of positivity and negativity. Analytically, interaction terms are introduced at the nomothetic and not idiographic level, and therefore refer to the general/average effect of positivity (or negativity) in the presence of negativity (or positivity, respectively). In reality, each spouse experiences a very specific combination of positivity and negativity in his or her marriage, and analysts must look beyond statistical interaction terms to understand the effects of these idiographic marital types.

For instance, indifferent marriages have been characterized as low in both strain and support (Fincham & Linfield, 1997; Kim & Waite, 2014). Indifference is reflected in infrequent or shallow interactions, and unimportant or casual social relationships more generally (Campo et al., 2009). Within a marriage, indifference potentially signifies a lack of engagement in, or withdrawal from, the marital relationship. Accordingly, partners whose self-reports of positivity and negativity indicated an indifferent spousal relationship also reported lower levels of marital satisfaction than those in supportive marriages (high positivity, low negativity), but higher levels than those in aversive marriages (low positivity, high negativity) (Fincham & Linfield, 1997). On the other hand, some kind of investment in and expectation from a partner is a prerequisite to having one’s emotional state affected, and indifference potentially signals a lack of investment that may leave one’s own loneliness unaffected. Whether indifference is associated with more or less loneliness remains unexamined in research to date.

A growing literature has shown that the co-existence of high levels of both support and strain that characterize an ambivalent relationship (Fincham & Linfield, 1997; Uchino et al., 2001) has unique effects on psychological and physical health and well-being, where a greater degree of ambivalence (e.g., a larger number of ambivalent relationships, more frequent ambivalent interactions) has been associated with elevated systolic blood pressure (Holt-Lunstad, Uchino, Smith, Olson-Cerny, & Nealey-Moore, 2003), poorer cardiovascular health (Uchino, Smith, & Berg, 2014), and poorer psychological well-being (Fingerman, Pitzer, Lefkowitz, Birditt, & Mroczek, 2008). This body of research points to the generally adverse effects of marital ambivalence, but the association between ambivalence and loneliness has not yet been studied.

Loneliness in marital partners: Actor-partner effects of marital quality

Loneliness is more similar between marital partners than would be expected by chance (Distel et al., 2010). This could be attributable to, among other things, assortative mating, common life stressors (e.g., job loss, death of a child), mutual influences (i.e., one partner’s loneliness influences or causes the other partner’s loneliness), and partner effects (e.g., one partner’s appraisal of marital quality affects the other partner’s loneliness) (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Research has also shown that loneliness spreads among individuals by virtue of the frequency and quality of interactions (Cacioppo, Fowler, & Christakis, 2009; Hawkley et al., 2008), suggesting that spouses should be especially sensitive to partner effects. Individuals who act negatively toward their partner, for example, by withdrawing affection, complaining or criticizing (Carr, Freedman, Cornman, & Schwarz, 2014), can increase their partner’s loneliness. Conversely, individuals who act positively toward their partner can diminish their partner’s loneliness. Consistent with this hypothesis, and as noted earlier, perceived spousal support was negatively associated not only with one’s own loneliness but also with one’s partner’s loneliness among older adults in the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP) (Moorman, 2015). These results were replicated in the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) (Stokes, 2016). Unexpectedly, in both studies, perceiving the spouse more negatively (i.e., demanding, critical) was associated with the spouse feeling less lonely, although one’s own loneliness was higher. In explaining this finding, Moorman (2015) conjectured that partners may be demanding and critical as a way of engaging the spouse, and that any engagement, even if negative, may be better than neglect or indifference in terms of reducing feelings of loneliness. By taking a bi-dimensional approach to marital quality, we can directly assess whether feelings of ambivalence or aversion, relative to feelings of indifference, are associated with less loneliness in the partner.

Moderational effects of friend and family relationships

Most married couples have relationships with family and friends that may counteract any negative influences of marital type on loneliness. For example, spouses who feel negative about their marriage may feel lonely only to the extent that they lack positive, supportive relationships with family members and friends, as suggested by individual-level analyses (Chen & Feeley, 2014). Specifically, Chen and Feeley (2014) found independent exacerbating effects of strain from each of four sources (spouse, children, family, and friends) and independent ameliorating effects of support from the spouse and from friends on feelings of loneliness. However, their analysis did not address moderating effects. Warner and Adams (2012) focused on the buffering role of non-marital relationship quality in married older adults who did versus did not suffer from physical disablement; their results showed that support and strain in non-spousal relationships (friends or other family) did not moderate the effect of disability on loneliness. However, non-spousal support buffered the effect of negative marital quality on loneliness among non-disabled adults. Both Warner and Adams (2012) and Chen and Feeley (2014) conducted their analyses at the individual level and did not consider individuals embedded in marital dyads. In this study, we examine the moderating effects of actor’s non-spousal support and strain on his/her own loneliness.

Gender differences

In heterosexual marriages, marital quality and vulnerability to poor marital quality may differ by gender. Women tend to report lower levels of marital quality in part because traditionally they shoulder more household and childcare duties and possess less power and authority in a marriage (Umberson & Williams, 2005). Some studies further show that relationship quality has a stronger impact on health and well-being among women than men (Thomeer, Reczek, & Umberson, 2015; Walen & Lachman, 2000); however, other studies have found no such gender differences (Ayalon et al., 2013; Moorman, 2015; Umberson & Williams, 2005). From a life course perspective, gender differences, if any, may become less pronounced in late adulthood due to changes in social roles (Carr & Moorman, 2011; Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999; Umberson & Williams, 2005). For example, men may become more emotionally devoted to and rewarded by their marital relationship following retirement. Conversely, however, wives who continue to work after their husband retires appear especially prone to experiencing marital conflict (Davey & Szinovacz, 2004). In a dyadic setting, we test to what extent older wives and husbands assess their marriages differently (as a combination of positive and negative qualities) and whether marital quality exerts stronger actor and partner effects on loneliness for one gender than the other.

Research questions and hypotheses

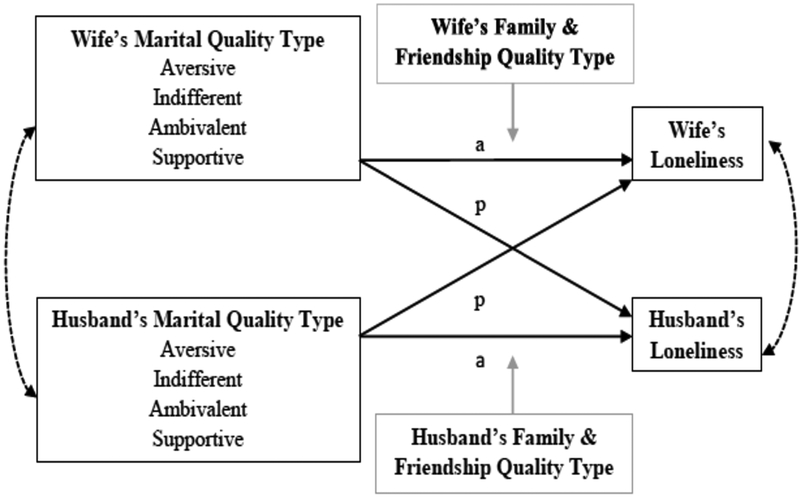

In the present research, we create a marital quality typology that represents combinations of high and low levels of co-occurring spousal support and strain, and examine the effects of husbands’ and wives’ marital types on actor and partner loneliness. Our conceptual model is illustrated in Figure 1. Based on prior research, we hypothesize that marital ambivalence (high support, high strain) and indifference (low support, low strain) will be associated with greater actor loneliness (“a” paths) and partner loneliness (“p” paths) than is observed for individuals in supportive marriages (high support, low strain), but with less actor and partner loneliness than those in aversive marriages (low support, high strain). We also test whether marital ambivalence and indifference are differentially related to loneliness in the actor and partner. In addition, we address whether the types of relationships with other network members, specifically with friends and with relatives, buffer or exacerbate the effects of marital type on loneliness. Finally, we test for gender differences in these associations; prior related research shows conflicting findings, and we have no basis for hypothesizing the direction of differences should they exist.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of marital quality type and loneliness in dyads

Notes: a=Actor effects on loneliness. p=Partner effects on loneliness. Dashed paths refer to correlations between wife’s and husband’s marital quality type and loneliness.

Methods

Participants

Sample selection.

The study uses dyadic data from the second wave (2010–11) of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP). NSHAP is a nationally representative study of 3,005 older adults aged 57–85 years in Wave 1 (2005–06). About 88% of the Wave 1 respondents were re-interviewed 5 years later in Wave 2. In addition, a random subsample of co-resident spouses and partners were invited to be part of the study in Wave 2, regardless of their age, and 86% of them completed the interview (O’Muircheartaigh, English, Pedlow, & Kwok, 2014). Ultimately, both partners in 955 married or cohabiting couples were interviewed. Because we were interested in studying gender differences, our final sample included 953 heterosexual couples (1906 husbands and wives). Some of the measures, including loneliness, have more missing values because the questions were asked in the leave-behind questionnaire which exhibited a somewhat higher rate of missing data than the in-person interview (Hawkley, Kocherginsky, Wong, Kim, & Cagney, 2014). However, we kept these cases in our analysis by using the full-information maximum likelihood method for model estimation. A robustness check that excluded cases with any missing values (N=294) showed highly consistent results with those reported here.

Measures

Loneliness, the outcome variable, is a three-item measure that asks how often the respondent feels lack of companionship, left out, and isolated from others (Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2004). Each item is rated on a 3-point scale (0 = never/hardly ever, 1 = some of the time, 2 = often) and responses are summed to generate a total loneliness score, which ranges from 0–6 (alpha = .8).

Marital quality type, the main independent variable, was categorized based on responses to questions about spousal support and strain that were derived from the 10-item scale of Schuster, Kessler, and Aseltine (1990). Spousal support was assessed with two items asking partners the degree to which they could open up to and rely on their spouse, and spousal strain asked two questions about the degree to which their spouse made too many demands on them and criticized them. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale (0 = never/hardly ever, 1 = some of the time, 2 = often). High (versus low) support was defined as responding “often” to both support items. Low (versus high) strain was defined as responding “never” or “hardly ever” to both strain items. We defined the levels of support and strain asymmetrically because research has long shown that negative experiences occur much less frequently but have greater psychological impact than positive experiences (Krause & Rook, 2003; Rook, 1984; Schuster et al., 1990). Indeed, the majority of our sample adults reported that their spouse never or hardly ever makes too many demands on them (62% for men; 68% for women) or criticizes them (50% for men; 65% for women), and the vast majority of them often open up to their spouse (75% for men; 71% for women) and rely on them (91% for men; 83% for women) (see Appendix 1 for more details). Therefore, respondents who perceived spousal demands or criticisms at least some of the time were defined as high (rather than low) in spousal strain. The dichotomous support and strain variables were then used to generate four marital quality types: supportive (high support and low strain), ambivalent (high support and high strain), indifferent (low support and low strain), and aversive (low support and high strain). In the analysis, the supportive marriage type was treated as the reference group for the other three types. Similar categorization has been used in previous studies to examine the quality of marriage, family, friendship, and other social relationships (Campo et al., 2009; Windsor & Butterworth, 2010). Nevertheless, we conducted robustness checks and confirmed that results remain highly consistent when instead we used median splits to define high versus low support or strain. We chose to present the current categorization because its reliance on discrete response options provides a clear and replicable definition of the marital categories.

Family quality and friendship quality, two potential moderators of the association between marital quality and loneliness, were measured in the same way as marital quality (support and strain items), and were categorized in the same manner as supportive, ambivalent, indifferent, or aversive. Descriptive data for the individual items comprising spousal, family, and friend support and strain are provided in Appendix 1.

Covariates included husband’s and wife’s respective age, education, race/ethnicity, network size, and number of difficulties with Activities of Daily Living (ADL). According to previous studies, each of these factors is correlated with social and/or emotional wellbeing (Hawkley et al., 2008; Victor, Scambler, Bowling, & Bond, 2005). Age is a continuous measure ranging from 36 to 99 years. Education has four response categories: less than high school, high school diploma, associate degree or some college education, and bachelor’s degree or higher. Race/ethnicity includes four categories: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other. Network size was obtained from the social network interview and is a count of the number of confidants the respondent identified as someone with whom they discussed important matters. Number of ADLs is the count of any difficulties with the following 7 activities: walking across a room, walking one block, dressing, bathing/showering, eating, getting in or out of bed, and using the toilet. Additionally, all the structural equation models are adjusted for household income as reported by husbands; wives’ reports of household income were missing at a higher rate than husbands’ (12.7% versus 6.8%), and husbands’ reports were assumed to be more accurate in this age group. Annual household income, a shared characteristic between marriage partners, includes four categories: lower than $25,000, between $25,000 and $50,000, between $50,000 and $100,000, and more than $100,000.

Analytic strategy

We analyzed the dyadic data using structural equation modeling, specifically, the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM). This model corrects for biased variances that occur when the individual is treated as the unit of analysis and nonindependence between dyad members is ignored. In our case, the nonindependence of loneliness between marriage partners is significant: the intraclass correlation indicated that 28% of the variance in loneliness was attributable to couple-level (rather than individual-level) differences (95% CI: 0.21–0.35). Further, the APIM is able to test partner effects over and above actor effects (e.g., partner’s marital ratings affect the actor’s loneliness over and above the effect of the actor’s marital ratings on own loneliness). We used Wald tests to determine if partner and actor effects are equivalent in size, and if the effect sizes are equivalent by gender (i.e., between wives and husbands). All the APIM analyses were estimated by the full-information maximum likelihood method and adjusted for couples’ sampling weights (O’Muircheartaigh et al., 2014). The models allow and estimate correlations among variables, including husbands’ and wives’ socio-demographic characteristics.

Results

Descriptive statistics by marital quality type

Overall, most women and men perceive their intimate relationship as supportive. Women are most likely to live in a supportive marriage (42.0%) or an ambivalent marriage (25.0%). While these two marriage types are also prevalent among men, men are more likely than women to perceive their marriage as ambivalent (38.6%) and less likely than women to perceive their marriage as supportive (35.0%) (Table 1). Regardless of gender, about a fifth of the older adults live in an aversive marriage with low support and high strain. Interestingly, marital quality types were often inconsistent between husbands and wives. The inter-rater agreement of marital quality type between wives and husbands was only slightly higher than agreement by chance (kappa statistic = .12, p < .01). Discrepancies in marital quality ratings indicate that marital quality is not a characteristic shared by the couple but differs between partners and thus allows for the possibility of independent actor and partner effects.

Table 1.

Dyadic distribution of marital quality type (%).

| Husband’s Marital Quality Type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wife’s Marital Quality Type | Aversive | Indifferent | Ambivalent | Supportive | Total |

| Aversive | 6.45 | 1.38 | 10.39 | 3.41 | 21.63 |

| Indifferent | 2.58 | 0.84 | 4.38 | 3.62 | 11.42 |

| Ambivalent | 4.83 | 1.85 | 11.39 | 6.92 | 24.99 |

| Supportive | 4.68 | 3.81 | 12.39 | 21.08 | 41.96 |

| Total | 18.54 | 7.88 | 38.55 | 35.03 | 100.00 |

Loneliness differed significantly among marital quality types. Tables 2a (women) and 2b (men) show that loneliness levels were highest in women and men in an aversive marriage relative to ambivalent and supportive marriages (ps < .05). In addition, individuals in an indifferent or ambivalent marriage were lonelier than those in a supportive marriage. One gender difference was noted; women in an indifferent marriage were lonelier than those in an ambivalent marriage, but this effect was not evident in men.

Table 2a.

Descriptive statistics by marital quality type: women.

| Total | Aversive | Indifferent | Ambivalent | Supportive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness (scale:0–6)*** | 0.93 | 1.81 | 1.34 | 0.77 | 0.50 |

| SD | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.06 |

| Family quality (%)*** | |||||

| Aversive | 19.85 | 29.15 | 18.61 | 22.36 | 14.02 |

| Indifferent | 31.44 | 27.96 | 52.61 | 25.60 | 30.72 |

| Ambivalent | 16.05 | 19.11 | 7.45 | 22.62 | 13.06 |

| Supportive | 32.66 | 23.77 | 21.32 | 29.41 | 42.2 |

| Friendship quality (%)*** | |||||

| Aversive | 7.53 | 12.79 | 8.42 | 7.51 | 4.66 |

| Indifferent | 62.22 | 62.26 | 72.90 | 64.40 | 57.94 |

| Ambivalent | 3.62 | 2.83 | 2.68 | 7.93 | 1.74 |

| Supportive | 26.63 | 22.11 | 15.99 | 20.15 | 35.67 |

| Age | 67.60 | 68.35 | 68.59 | 66.67 | 67.48 |

| SD | 0.35 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.51 |

| Number of ADL (scale: 0–7) | 0.72 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.85 | 0.55 |

| SD | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.07 |

| Network size | 4.95 | 5.17 | 4.76 | 4.89 | 4.95 |

| SD | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| Household income (%) | |||||

| <25K | 15.11 | 17.28 | 21.74 | 16.55 | 11.16 |

| 25–50K | 27.28 | 27.69 | 26.09 | 22.22 | 30.52 |

| 50–100K | 35.24 | 36.15 | 35.74 | 36.79 | 33.67 |

| >100K | 22.37 | 18.87 | 16.43 | 24.44 | 24.64 |

| Education (%) | |||||

| < HS | 10.79 | 13.21 | 20.37 | 8.26 | 8.37 |

| HS/equiv | 24.86 | 25.50 | 19.97 | 23.50 | 26.69 |

| Voc cert/some college/assoc | 39.74 | 40.89 | 42.98 | 39.30 | 38.50 |

| Bachelor’s or more | 24.62 | 20.41 | 16.68 | 28.93 | 26.44 |

| Race/ethnicity (%)* | |||||

| White | 83.79 | 78.99 | 81.61 | 80.85 | 88.65 |

| Black | 6.34 | 11.09 | 3.99 | 7.71 | 3.69 |

| Hispanic | 7.39 | 7.44 | 10.61 | 9.39 | 5.27 |

| Other | 2.48 | 2.48 | 3.79 | 2.05 | 2.39 |

Notes:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001 for significance tests across groups of different marriage types. Percentages for family and friendship quality, household income, education, or race/ethnicity may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Older men and women in different marriage types also reported different family and friendship quality (ps < .05). In general, marital quality aligned with family and friend relationship quality. Those in a supportive marriage tended to also have supportive family and friend relationships, whereas those in an aversive marriage were more likely to have aversive family and friend relationships. This pattern suggests that older adults suffering from poor marital quality may not have other social resources to mitigate their marital distress.

Marital quality types differed among racial-ethnic groups. In particular, relative to White women and men, Black women and men were more likely to live in an aversive marriage (ps < .05), and Hispanic men were more likely to live in an ambivalent marriage (p < .05). In contrast, White women were more likely to be in a supportive marriage than their Black and Hispanic counterparts, and White men were also more likely be in a supportive marriage than Black men (ps < .05).

Actor-partner effects of marital quality types on loneliness

In support of our hypothesis, we found that an aversive marriage is related to a significantly higher level of loneliness for both wives and husbands and from both actor and partner perspectives (Table 3). Individuals in an aversive marriage are lonelier than those in a supportive marriage, and they are also lonelier than individuals in an indifferent or ambivalent marriage (ps < .05). In addition, a partner who is classified as having an aversive marriage predicts higher loneliness of the actor (i.e., the self). However, the partner effects are weaker than the actor effects, particularly among women (i.e., wife’s marital quality type has a stronger effect on her own loneliness than her husband’s marital quality type does). These findings highlight the interdependence of marital partners, suggesting that both actor’s and partner’s marital quality type is associated with the actor’s sense of loneliness.

Table 3.

Actor and partner effects of marital quality type on loneliness.

| Wife’s Loneliness | Husband’s Loneliness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wife’s Marital Quality Type | Coeff. | S.E. | Coeff. | S.E. |

| Supportive (ref) | ||||

| Ambivalent | 0.18 | 0.12 | –0.02 | 0.12 |

| Indifferent | 0.71*** | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.15 |

| Aversive | 1.14*** | 0.14 | 0.61*** | 0.14 |

| Husband’s Marital Quality Type | ||||

| Supportive (ref) | ||||

| Ambivalent | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| Indifferent | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.22 |

| Aversive | 0.60*** | 0.17 | 0.82*** | 0.15 |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001. Boldface indicates actor effects and regular type indicates partner effects. All the coefficients are adjusted for husband’s and wife’s respective age, number of ADL, network size, education, and race/ethnicity, and husband’s report of household income.

Although the overall pattern applies to both women and men, there is one notable gender difference. Wives in an indifferent marriage are lonelier than their counterparts in an ambivalent or supportive marriage (ps < .05). However, an indifferent marriage is not associated with higher loneliness than an ambivalent or supportive marriage among husbands.

Finally, when intra-couple dependence is taken into account, the loneliness differences among individuals in supportive versus ambivalent (or indifferent) marriages are no longer significant (except the gender pattern described above). This finding highlights that supportive, ambivalent, and indifferent marriages, despite being qualitatively distinct, may be relatively similar in relation to loneliness. It also reveals that the aversive marriage is distinctly isolating compared to all the other marriage types.

Moderating effects of non-marital relationships

We hypothesized that the relationship between actor’s marital quality and loneliness may be moderated by his/her own quality of relationships with family and friends. However, this hypothesis was not supported for either gender. Specifically, having a supportive family relationship did not ameliorate the lonely effects of an aversive marriage (interaction effects are .11 for women and .26 for men, ps > .6). Neither did a supportive friendship ameliorate such loneliness effects (interaction effects are –.06 for women and .01 for men, ps > .8). Consistently, an aversive family or friend relationship did not exacerbate the loneliness effects of an aversive marriage. The findings suggest that non-marital relationships may be peripheral to married elders’ social life. In fact, many husbands and wives perceived their friendships and family relationships as indifferent (62–71% of friendships; 31–52% of family relationships), that is, providing low support and having low strain (Tables 2a and 2b). Supportive family and friend relationships, which are characterized by concurrent high support and low strain, were not very common (14–27% of friendships; 21–33% of family relationships).

Table 2b.

Descriptive statistics by marital quality type: men.

| Total | Aversive | Indifferent | Ambivalent | Supportive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness (scale:0–6)*** | 0.84 | 1.56 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.57 |

| SD | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| Family quality (%)*** | |||||

| Aversive | 19.78 | 26.60 | 11.15 | 25.19 | 11.73 |

| Indifferent | 52.18 | 53.05 | 69.21 | 44.55 | 56.52 |

| Ambivalent | 7.14 | 9.07 | 2.17 | 11.44 | 2.23 |

| Supportive | 20.90 | 11.28 | 17.47 | 18.82 | 29.52 |

| Friendship quality (%)* | |||||

| Aversive | 12.98 | 22.39 | 8.07 | 13.29 | 8.81 |

| Indifferent | 70.88 | 69.97 | 81.24 | 65.63 | 74.87 |

| Ambivalent | 1.64 | 1.04 | 0.00 | 2.49 | 1.38 |

| Supportive | 14.50 | 6.60 | 10.69 | 18.59 | 14.94 |

| Age | 71.11 | 71.37 | 68.69 | 71.83 | 70.54 |

| SD | 0.33 | 0.56 | 1.05 | 0.53 | 0.61 |

| Number of ADL (scale: 0–7) | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.37 | 0.76 | 0.83 |

| SD | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.20 |

| Network size | 4.17 | 4.19 | 3.28 | 4.27 | 4.26 |

| SD | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| Household income (%) | |||||

| <25K | 15.04 | 18.10 | 13.03 | 15.67 | 13.08 |

| 25–50K | 26.97 | 24.42 | 27.83 | 28.52 | 27.86 |

| 50–100K | 35.51 | 37.55 | 35.65 | 34.49 | 35.68 |

| >100K | 22.48 | 19.94 | 23.49 | 21.32 | 23.39 |

| Education (%) | |||||

| < HS | 14.83 | 19.94 | 8.04 | 13.83 | 14.74 |

| HS/equiv | 23.38 | 25.52 | 20.14 | 26.32 | 19.74 |

| Voc cert/some college/assoc | 26.49 | 21.30 | 23.11 | 27.16 | 29.24 |

| Bachelor’s or more | 35.31 | 33.24 | 48.70 | 32.69 | 36.27 |

| Race/ethnicity (%)* | |||||

| White | 83.90 | 79.26 | 90.01 | 81.44 | 87.68 |

| Black | 6.31 | 11.87 | 4.00 | 6.27 | 3.94 |

| Hispanic | 7.42 | 5.86 | 4.68 | 9.93 | 6.10 |

| Other | 2.37 | 3.02 | 1.31 | 2.35 | 2.28 |

Notes:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001 for significance tests across groups of different marriage types within each gender. Percentages for family and friendship quality, household income, education, or race/ethnicity may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Discussion

We posited that positive and negative marital qualities would exhibit contextual effects on loneliness in one or both partners. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that individuals in an aversive marriage – high strain embedded in low support – are not only lonelier than those in supportive marriages, but also lonelier than those in ambivalent and indifferent marriages. Moreover, individuals in an aversive marriage contribute to the loneliness of their partner. An indifferent marriage was associated with greater loneliness than supportive and ambivalent marriages, but this effect was unique to wives and did not spill over to affect husbands’ loneliness. Relationships with family and friends, regardless of their quality, did not buffer or exacerbate the effects of marital quality on loneliness.

Marital quality contextualized: Lessons learned & implications

In our nationally representative sample of older adults, the majority of wives reported a purely supportive marital relationship, but a sizeable proportion reported ambivalence (i.e., support in the context of considerable marital strain). More husbands, on the other hand, reported an ambivalent marital relationship, although purely supportive relationships were also prevalent. Indifferent marriages were relatively rare among both husbands and wives, but at least a fifth of marriages among both husbands and wives were strained with little or no redeeming supportive qualities.

The emotional and companionate support afforded by a spouse can buffer the social and health losses of aging (Waldinger & Schulz, 2010), but less is known about the effects of a marriage that although lacking in support is also low in strain (i.e., indifferent). In an indifferent marriage, a spouse who offers little support but also makes few if any demands may leave one or both partners feeling neglected and alone. Indeed, women in indifferent marriages were significantly lonelier than those in supportive marriages even after controlling for the effects of their spouse’s evaluations of the marriage. This effect was significantly smaller in men than women, and contrasts with the absence of gender differences observed by Moorman (2015) and Stokes (2016). The simultaneous co-occurrence of positive and negative marital qualities thus provides an insight into gender-specific effects of marital quality not evident when positivity and negativity are examined independently. Again, these were solely actor effects; the actors’ perceptions of indifferent marriages did not spill over to affect the partners’ loneliness for either husbands or wives.

Partners who feel torn between the positive and negative aspects of their marital relationship (i.e., ambivalent) may suffer even more than those who experience neither negativity nor positivity (i.e., indifferent), but our data show that, at least for women, those in indifferent marriages are lonelier than those in ambivalent marriages. This difference could be attributable to low levels of support in the indifferent group and/or high levels of strain in the ambivalent group. A comparison of the magnitudes of the coefficients suggests that the absence of support may have a larger effect than the presence of strain in explaining loneliness differences between wives in indifferent and ambivalent groups (p < .05). Interestingly, neither indifferent marriages nor ambivalent marriages were related to elevated levels of loneliness among men. This gender difference suggests that in heterosexual marriages women may more highly value the supportive traits than the undemanding/uncritical traits of a spouse. In contrast, men in heterosexual marriages may value high support and low strain more equally, and may not feel lonely as long as the spouse is either supportive or undemanding and uncritical. Gender differences were also reported by Boerner et al. (2014), who found that positive appraisals of marriage were more strongly predictive of global marital satisfaction in women than in men, whereas negative appraisals were relatively more important in men than in women. These findings imply that the negative and positive aspects of the marriage may differentially affect men and women.

Aversive marriages were lonelier than supportive, ambivalent, and indifferent marriages for both husbands and wives. Moreover, aversive marriages also exhibited partner effects, albeit weaker than actor effects. What might account for the partner effect? A spouse who feels little support and much stress in their marital relationship is likely to feel more hostile toward their partner, and feelings of hostility could manifest in less compassionate behavior that would be expected to increase the partner’s feelings of isolation and loneliness (Hawkley et al., 2008). Moreover, according to interpersonal theory (Sadler & Woody, 2003), the quality of the behavior of an actor elicits similar behavior from a partner, thereby setting in motion a spiral that exacerbates poor relationship quality. In an aversive marriage, the reciprocation of negative behaviors is accompanied by a lack of reciprocal positive behaviors, further deteriorating the quality of the marriage. This reinforcing spiral of high negative and low positive behaviors would be expected to perpetuate feelings of loneliness and isolation in both marital partners.

Although aversive marriages were significantly lonelier than supportive, ambivalent, and indifferent marriages, differences in loneliness among these other marriage types, particularly supportive and ambivalent marriages, were much less prominent. This implies that being demanding and critical as a caring spouse (the ambivalent quality) does not contribute to either the self’s or the partner’s loneliness. Demands and criticism are likely motivated by and perceived as benevolence in a supportive context (Warner & Adams, 2016). Demands and criticism from an unconcerned spouse (the aversive quality), on the other hand, could lead to feelings of estrangement and loneliness. This contrast highlights that the impact of negative spousal qualities depends on the co-occurrence of positive spousal qualities.

Moreover, it is a testament to the importance of the marital relationship in older adults that support from family and friends did not compensate for distress in the marriage; loneliness remained significantly higher among older adults in aversive marriages than in their happily married peers regardless of level of support from others. It is interesting in this regard to note that individuals reported less support in their relationships with family and friends than their marital relationship. The fact that these relationships did not moderate or exacerbate the effect of marital quality on loneliness reinforces the conclusion that the marital relationship is unmatched in older age for imbuing each spouse with a sense of connectedness.

Limitations and future directions

Ours was a cross-sectional study; longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether marital happiness, ambivalence, indifference, and distress play a causal role in explaining loneliness and other outcomes. At the individual level, early results (Warner & Adams, 2016) have shown that improvements in positive marital quality were associated with a reduction in loneliness across the 5-year interval between Waves 1 and 2 in NSHAP; changes in negative marital quality were not independently related to changes in loneliness. Fortunately, NSHAP is a panel study in which data from each partner will be available in subsequent waves. This will permit assessment not only of the longer-term influences of marital quality on both members of the dyad, but also the stability of marital quality over time.

The simultaneous consideration of spousal support and strain is only one way of conceiving and operationalizing marital quality. Other features of the marriage may also play a role in determining not only marital quality and loneliness but also downstream consequences for health and well-being. Prior research using the NSHAP data has examined and found that shared leisure activities and sexual frequency do not affect loneliness of either the actor or partner (Moorman, 2015), but these findings did not contextualize leisure activities and sexual frequency in combination with other concurrent positive and negative relationship features. Whether sexual frequency, for example, differs as a function of marital type (e.g., indifferent, supportive), whether sexual frequency contributes to loneliness in the presence of an indifferent versus a supportive marriage (for example), and whether men and women differ in this regard, remain to be tested.

Social desirability may encourage some survey respondents to conceal their true perceptions of marriage by underreporting marital strain or overreporting marital support. This could lead to more conservative results in our analysis. That is, the effects of aversive, indifferent, or ambivalent marriages on own or partner’s loneliness may be larger in real life.

Feeney (2015) has delineated a theoretical model that links qualities of couple relationships with psychological and physiological processes that are directly relevant to health. Because marriages were not experienced uniformly by each partner in the relationship, future research should examine how spousal discrepancies in appraisals of their marriage may affect not only loneliness, but also the physical and emotional health and well-being of each marital partner.

Partner effects are important in the context of interventions. Specifically, for individuals in aversive marriages, attempts to reduce loneliness may do well to intervene with the couple. For instance, couples may benefit from both partners gaining an appreciation for their role and capacity to influence each other’s sense of loneliness, learning how to communicate one’s own support needs and how to satisfy the partner’s support needs, and recognizing and learning how to avoid the potential harm caused by demands and criticism. Couples’ therapy may be helpful for those older adults who are willing and able to take advantage of a therapist’s help. Additional research is needed to determine the feasibility, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of couple-level interventions, given that loneliness interventions to date, even when delivered in groups, have been evaluated for effectiveness only on the individual level (Masi, Chen, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2011). This work awaits evidence that improving the balance of positive and negative spousal qualities can prevent or ameliorate loneliness not only in the actor but, importantly, also in the partner.

Conclusion

Marital quality is an alloy of positive and negative features, and like any alloy, the proportion of each element in the alloy is critical to its strength and resilience. The results reported here indicate that some alloys are not as strong as others. Individuals who perceived a disproportionate share of negativity were lonelier than those with a more balanced proportion of negativity and positivity. Moreover, just as weak metallic alloys in one structure can affect the integrity of adjacent structures, weak marital alloys in one partner can affect the quality of the other partner’s marital experience. We conclude that a dyadic approach to marital quality can inform our understanding of the effects of marriage on a range of outcomes, including physical, cognitive, emotional, and social well-being.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from NIH, including the National Institute on Aging (T32 AG000243, P30 AG012857), the Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research for the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP) (grant numbers R01 AG021487, R37 AG030481), the NSHAP Wave 2 Partner Project (R01 AG033903), and by NORC, which was responsible for the data collection. Earlier drafts of this paper were presented at the 2016 Meeting of the German Psychological Society and the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America.

APPENDIX 1

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics for positive and negative relationship qualities.

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| Marital quality | ||

| Open up to spouse (%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 3.9 | 3.3 |

| Some of the time | 24.6 | 21.0 |

| Often | 71.3 | 75.3 |

| Rely on spouse (%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 3.0 | 1.1 |

| Some of the time | 13.8 | 7.9 |

| Often | 82.9 | 90.8 |

| Spouse makes too many demands on you (%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 68.4 | 62.4 |

| Some of the time | 21.2 | 26.9 |

| Often | 10.0 | 10.3 |

| Spouse criticizes you (%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 65.0 | 50.3 |

| Some of the time | 26.4 | 39.2 |

| Often | 8.2 | 10.0 |

| Family quality | ||

| Open up to family members (%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 9.0 | 28.9 |

| Some of the time | 35.1 | 38.9 |

| Often | 55.9 | 32.2 |

| Rely on family members (%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 5.5 | 12.5 |

| Some of the time | 22.2 | 26.2 |

| Often | 72.3 | 61.3 |

| Family members make too many demands on you(%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 74.8 | 80.9 |

| Some of the time | 19.4 | 15.6 |

| Often | 5.8 | 3.5 |

| Family members criticize you (%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 79.3 | 86.2 |

| Some of the time | 16.5 | 12.2 |

| Often | 4.2 | 1.6 |

| Friendship quality | ||

| Open up to friends (%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 21.7 | 39.7 |

| Some of the time | 39.6 | 41.0 |

| Often | 38.7 | 19.3 |

| Rely on friends (%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 14.3 | 21.4 |

| Some of the time | 34.4 | 39.8 |

| Often | 51.3 | 38.8 |

| Friends make too many demands on you (%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 94.5 | 92.6 |

| Some of the time | 5.2 | 6.9 |

| Often | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Friends criticize you (%) | ||

| Never/hardly ever | 92.8 | 91.0 |

| Some of the time | 6.6 | 8.3 |

| Often | 0.6 | 0.7 |

Contributor Information

Ning Hsieh, Michigan State University.

Louise Hawkley, NORC at the University of Chicago.

References

- Ayalon L, Shiovitz-Ezra S, & Palgi Y (2013). Associations of loneliness in older married men and women. Aging & Mental Health, 17, 33–39. 10.1080/13607863.2012.702725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner K, Jopp DS, Carr D, Sosinsky L, & Kim S-K (2014). “His” and “her” marriage? The role of positive and negative marital characteristics in global marital satisfaction among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, 579–589. 10.1093/geronb/gbu032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Fowler JH, & Christakis NA (2009). Alone in the crowd: The structure and spread of loneliness in a large social network. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 977–991. 10.1037/a0016076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo RA, Uchino BN, Holt-Lunstad J, Vaughn A, Reblin, & Smith TW (2009). The assessment of positivity and negativity in social networks: The reliability and validity of the social relationships index. Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 471–486. 10.1002/jcop.20308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, Freedman VA, Cornman JC, & Schwarz N (2014). Happy marriage, happy life? Marital quality and subjective well-being in later life. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 930–948. 10.1111/jomf.12133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, & Moorman SM (2011). Social relations and aging In Settersten RA & Angel JL (Eds.), Handbook of sociology of aging (pp. 145–160). New York, NY: Springer; 10.1007/978-1-4419-7374-0_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, & Charles ST (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54, 165–181. 10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, & Feeley TH (2014). Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults An analysis of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31, 141–161. 10.1177/0265407513488728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davey A, & Szinovacz ME (2004). Dimensions of marital quality and retirement. Journal of Family Issues, 25, 431–464. 10.1177/0192513X03257698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J, & Broese van Groenou M (2016). Older couple relationships and loneliness In Bookwala J (Ed.), Couple relationships in the middle and later years: Their nature, complexity, and role in health and illness (pp. 57–76). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J, Broese van Groenou M, Hoogendoorn AW, & Smit JH (2009). Quality of marriages in later life and emotional and social loneliness. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64B, 497–506. 10.1093/geronb/gbn043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distel MA, Rebollo-Mesa I, Abdellaoui A, Derom CA, Willemsen G, Cacioppo JT, & Boomsma DI (2010). Familial resemblance for loneliness. Behavior Genetics, 40, 480–494. 10.1007/s10519-010-9341-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA, & de Jong Gierveld J (2004). Gender and marital-history differences in emotional and social loneliness among dutch older adults. Canadian Journal on Aging, 23, 141–155. 10.1353/cja.2004.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA (2016). Close relationships, health, and wellbeing In Fitzgerald J and Byrne G (Eds.), Psychosocial dimensions of medicine (pp. 137–150). Victoria, Australia: IP Communications. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, & Linfield KJ (1997). A new look at marital quality: Can spouses feel positive and negative about their marriage? Journal of Family Psychology, 11, 489–502. 10.1037/0893-3200.11.4.489-502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, & Rogge R (2010). Understanding relationship quality: Theoretical challenges and new tools for assessment. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 2, 227–242. 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00059.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Pitzer L, Lefkowitz ES, Birditt KS, & Mroczek D (2008). Ambivalent relationship qualities between adults and their parents: Implications for the well-being of both parties. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63, P362–P371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Masi CM, Thisted RA, & Cacioppo JT (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63, S375–S384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Kocherginsky M, Wong J, Kim J, & Cagney KA (2014). Missing data in Wave 2 of NSHAP: Prevalence, predictors, and recommended treatment. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, S38–S50. 10.1093/geronb/gbu044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Uchino BN, Smith TW, Olson-Cerny C, & Nealey-Moore JB (2003). Social relationships and ambulatory blood pressure: Structural and qualitative predictors of cardiovascular function during everyday social interactions. Health Psychology, 22, 388–397. 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, & Cacioppo JT (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26, 655–672. 10.1177/0164027504268574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, & Waite LJ (2014). Relationship quality and shared activity in marital and cohabiting dyads in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project, Wave 2. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, S64–S74. 10.1093/geronb/gbu038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korporaal M, Broese van Groenou MI, & van Tilburg TG (2008). Effects of own and spousal disability on loneliness among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 20, 306–325. 10.1177/0898264308315431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, & Rook KS (2003). Negative interaction in late life: Issues in the stability and generalizability of conflict across relationships. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58, P88–P99. 10.1093/geronb/58.2.P88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu BS, & Rook KS (2013). Emotional and social loneliness in later life Associations with positive versus negative social exchanges. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30, 813–832. 10.1177/0265407512471809 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masi CM, Chen H-Y, Hawkley LC, & Cacioppo JT (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 219–266. 10.1177/1088868310377394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Kim JE, & Hofmeister H (2001). Couples’ work/retirement transitions, gender, and marital quality. Social Psychology Quarterly, 64, 55–71. 10.2307/3090150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman SM (2015). Dyadic perspectives on marital quality and loneliness in later life. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33, 600–618. 10.1177/0265407515584504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KL, & Wong EH (2001). Loneliness in marriage. Family Therapy, 28, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- O’Muircheartaigh C, English N, Pedlow S, & Kwok PK (2014). Sample design, sample augmentation, and estimation for Wave 2 of the NSHAP. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69, S15–S26. 10.1093/geronb/gbu053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA, & Perlman D (1982). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M (2003). Loneliness in married, widowed, divorced, and never-married older adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 20, 31–53. 10.1177/02654075030201002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS (1984). The negative side of social interaction: Impact on psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 1097–1108. 10.1037/0022-3514.46.5.1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler P, & Woody E (2003). Is who you are who you’re talking to? Interpersonal style and complementarily in mixed-sex interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 80–96. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster TL, Kessler RC, & Aseltine RH (1990). Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18, 423–438. 10.1007/BF00938116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TM, & Baron C (2016). Marital discord in the later years In Bookwala J (Ed.), Couple relationships in the middle and later years: Their nature, complexity, and role in health and illness (pp. 37–56). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Stack S (1998). Marriage, family and loneliness: A cross-national study. Sociological Perspectives, 41, 415–432. 10.2307/1389484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JE (2016). Marital quality and loneliness in later life A dyadic analysis of older married couples in Ireland. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34, 114–135. 10.1177/0265407515626309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomeer MB, Reczek C, & Umberson D (2015). Gendered emotion work around physical health problems in mid- and later-life marriages. Journal of Aging Studies, 32, 12–22. 10.1016/j.jaging.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornstam L (1992). Loneliness in marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9, 197–217. 10.1177/0265407592092003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Holt-Lunstad J, Uno D, & Flinders JB (2001). Heterogeneity in the social networks of young and older adults: Prediction of mental health and cardiovascular reactivity during acute stress. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 24, 361–382. 10.1023/A:1010634902498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Smith TW, & Berg CA (2014). Spousal relationship quality and cardiovascular risk Dyadic perceptions of relationship ambivalence are associated with coronary-artery calcification. Psychological Science, 25, 1037–1042. 10.1177/0956797613520015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, & Williams K (2005). Marital quality, health, and aging: gender equity? The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, S109–S113. 10.1093/geronb/60.Special_Issue_2.S109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Williams K, Powers DA, Chen MD, & Campbell AM (2005). As good as it gets? A life course perspective on marital quality. Social Forces, 84, 493–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor CR, Scambler SJ, Bowling A, & Bond J (2005). The prevalence of, and risk factors for, loneliness in later life: A survey of older people in Great Britain. Ageing & Society, 25, 357–375. 10.1017/S0144686X04003332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger RJ, & Schulz MS (2010). What’s love got to do with it? Social functioning, perceived health, and daily happiness in married octogenarians. Psychology and Aging, 25, 422–431. 10.1037/a0019087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walen HR, & Lachman ME (2000). Social support and strain from partner, family, and friends: Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17, 5–30. 10.1177/0265407500171001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warner DF, & Adams SA (2012). Widening the social context of disablement among married older adults: Considering the role of nonmarital relationships for loneliness. Social Science Research, 41, 1529–1545. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner DF, & Adams SA (2016). Physical disability and increased loneliness among married older adults The role of changing social relations. Society and Mental Health, 6, 106–128. 10.1177/2156869315616257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner DF, & Kelley-Moore J (2012). The social context of disablement among older adults Does marital quality matter for loneliness? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53, 50–66. 10.1177/0022146512439540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor TD, & Butterworth P (2010). Supportive, aversive, ambivalent, and indifferent partner evaluations in midlife and young-old adulthood. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B, 287–295. 10.1093/geronb/gbq016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JS, & Hsieh N (2017). Functional status, cognition, and social relationships in dyadic perspective. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. Retrieved from 10.1093/geronb/gbx024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorgason JB, Booth A, & Johnson D (2008). Health, disability, and marital quality: Is the association different for younger versus older cohorts? Research on Aging, 30, 623–648. 10.1177/0164027508322570 [DOI] [Google Scholar]