Abstract

Mitochondria fulfill the high metabolic energy demands of the kidney and are regularly exposed to oxidative stress causing mitochondrial damage. The selective removal of damaged and dysfunctional mitochondria through a process known as mitophagy is essential in maintaining cellular homeostasis and physiological function. Mitochondrial quality control by mitophagy is particularly crucial for an organ such as the kidney, which is rich in mitochondria. The role of mitophagy in the pathogenesis of kidney diseases has lately gained significant attention. In this review, we summarize the current understanding of the implications of mitophagy during pathological conditions of the kidney, including acute and chronic kidney diseases.

Keywords: Mitophagy, mitochondria, oxidative stress, acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease

Background

The kidney functions to remove wastes and maintains electrolyte reabsorption, and is known to have the highest resting metabolic rate and the number of mitochondria second to the heart1. Mitochondria are highly dynamic and plastic double-membraned organelles that satisfy the high energy requirements of the kidney and perform a wide array of cellular functions1. Mitophagy is a selective autophagy that recycles the dysfunctional or superfluous mitochondria. Over six decades ago, the first illustration of mitophagy was reported in the proximal tubules of the kidney by ultrastructural studies and identified through the presence of the mitochondria in the lysosome-like structure2. A growing body of evidence has since emerged to support the critical role of mitophagy in the maintenance of homeostasis in kidney cells. Under physiological conditions, the counterbalance between mitochondrial fusion and fission, and mitophagy maintains a healthy network of these organelles3–9. The mitochondrial dynamic is maintained collectively by these processes9. Mitophagy is modulated by multiple regulators, including phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-induced kinase1 (PINK1) and Parkin (E3 ubiquitin ligase, encoded by Prkn), FUN14 domain-containing protein 1 (FUNDC1), BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19kDa-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3), and NIP3-like protein X (NIX).

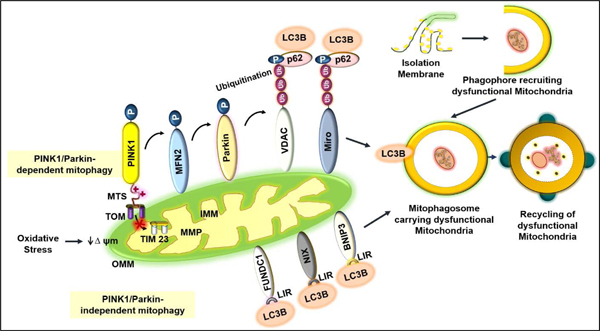

The PINK1/Parkin pathway of mitophagy is well known and widely studied. In a healthy cell, PINK1, a serine-threonine kinase, is recruited into the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) via translocase of the outer membrane (TOM) and translocase of the inner membrane (TIM23). Subsequently, the mitochondrial targeting signal (MTS) of PINK1 is cleaved by matrix metalloprotease (MMP) of mitochondria. However, under cellular stress, damaged mitochondria with a reducing membrane potential fail to import PINK1, and PINK1 accumulates on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), which in turn favors the recruitment of the cytosolic Parkin to the depolarized mitochondria7. We10 and others3 have shown that PINK1 phosphorylates the outer mitochondrial fusion protein mitofusin 2 (MFN2), and MFN2 plays a critical role in the recruitment of Parkin to the depolarized mitochondria. Parkin, after its recruitment, performs the ubiquitination of the OMM proteins, including MFN1 and MFN2, voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), and Miro4. Parkin further promotes the recruitment of autophagy adaptor protein sequestosome 1, also known as p62 (SQSTM1/p62)5. Subsequently, p62 binds with the ubiquitinated OMM proteins and microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) to promote autophagosome formation4–5. However, Narendra et al. demonstrated that the knockout or knockdown of p62 does not affect Parkin-mediated mitophagy, indicating that p62 may be dispensable for Parkin-dependent mitophagy6. In the PINK1/Parkin-independent pathway of mitophagy, LC3 directly binds with the OMM proteins: FUNDC1, BNIP3, and NIX via LC3B interacting region (LIR). The autophagosome that contains mitochondria is termed as mitophagosome, which finally accomplishes the turnover of dysfunctional mitochondria7 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of mitophagy: PINK1/Parkin-dependent and PINK1/Parkin-independent pathways. In the PINK1/Parkin dependent mitophagy, healthy mitochondria allow PINK1 to enter into the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) via translocase of outer membrane (TOM) and translocase of inner membrane (TIM)-23 proteins. The matrix metalloprotease (MMP) cleaves the mitochondrial targeting signal (MTS) of PINK1. Oxidative stress induces mitochondrial damage and a decline in membrane potential inhibits the import of PINK1 to the IMM. PINK1 accumulates on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) and binds with TOM. PINK1 phosphorylates mitofusin 2 (MFN2), resulting in the recruitment of Parkin from the cytoplasm to the OMM. Parkin facilitates the ubiquitination of OMM proteins including voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) and Miro. Subsequently, adaptor protein p62 attaches to the ubiquitinated OMM proteins. Lastly, p62 binds with LC3B and promotes mitophagosome formation. In PINK1/Parkin-independent mitophagy, LC3B directly interacts with OMM proteins: FUN14 domain-containing 1 (FUNDC1), NIP3-like protein X (NIX) and BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19kDa-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) via the LC3B interacting region (LIR). The process of mitophagy involves the formation of the isolation membrane for the recruitment of dysfunctional mitochondria into the mitophagosome, and subsequent lysosome-mediated degradation to recycle the damaged mitochondrial components.

The role of mitophagy in kidney diseases has recently captured considerable attention. This review summarizes the literature on the role of mitophagy during kidney diseases, with a focus on the functional significance of PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in the various experimental models for acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Table 1). The mitochondrial structural and functional alterations1, 8–9 during AKI11–13 and CKD14–15 are well recognized. The timely removal of dysfunctional mitochondria through mitophagy is crucial for normal homeostasis and regulating kidney function. Recently published findings suggest the cytoprotective role of mitophagy during both AKI16–19 and CKD10, 20–23.

Table 1.

Studies on the role of mitophagy and mitochondrial fission and fusion mediators using different experimental model of kidney diseases.

| Disease | Models | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AKI | IRI | Single and double Pink1 and Prkn knockout mice show severe renal tubular damage after IRI | 16 |

| Proximal tubule-specific Mfn2 knockout mice show improved renal function and better survival post-IRI | 30 | ||

| Proximal tubule-specific deletion of Drp1 protects against IRI-induced renal inflammation and apoptosis | 33 | ||

| BNIP3 expression in renal tubules increases after IRI | 18 | ||

| Bnip3 knockout mice after IRI exhibit higher oxidative stress, accumulation of damaged mitochondria, and severe renal injury | 19 | ||

| CIA | Pink1 or Prkn knockout mice show higher mitochondrial damage after CIA | 35 | |

| Cisplatin | Cisplatin-treated Pink1 and Prkn knockout mice display severe kidney damage and loss of renal function | 17 | |

| Pink1 deficiency prevents cisplatin-induced tubular damage and apoptosis | 36 | ||

| CKD | TIF: UUO or adenine diet | Pink1, Prkn, and LysM-specific Mfn2 single knockout mice display higher kidney fibrosis, frequency of profibrotic macrophages in the kidney after UUO, or adenine diet. | 10 |

| Pink1 or Prkn knockout mice show severe mitochondrial damage and higher mROS production in the kidney after UUO | 40 | ||

| DN: STZ | LC3 puncta, PINK1, and MFN2 expression decrease while the expression of DRP1 and Fis1 increase in the kidneys of STZ-induced diabetic mice | 14 | |

| DN: db/db mice | DRP1 expression increases while MFN2 and LC3 II expression and mitochondrial DNA copy number decrease in the kidney of db/db mice. MitoQ reverses these changes. | 21 |

AKI: acute kidney injury; IRI: ischemia-reperfusion injury; PINK1: Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-induced kinase1; MFN2: mitofusin 2; DRP1: dynamin-related protein 1; BNIP3: BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19kDa-interacting protein 3; CIA: Contrast-induced AKI; CKD: chronic kidney disease; TIF: tubulointerstitial fibrosis; UUO: Unilateral ureteral obstruction; DN: diabetic nephropathy; STZ: Streptozotocin; LC3: microtubule-associated protein light chain 3; MitoQ: mitoquinone.

Mitophagy in Acute Kidney Injury

Mitochondrial damage is known to exert a critical role in the progression of AKI. The renal tubules, which perform active reabsorption of ions, proteins, and solutes from the filtrate that passes through the glomerular filtration barrier, are particularly susceptible to injury in AKI. The number of mitochondria in the renal tubular epithelial cells is higher than any other cell types of the kidney1. Therefore, the published studies on the role of mitochondrial quality control in AKI have mostly focused on the tubules. The proximal convoluted tubules (PCT) display a higher oxygen consumption rate24 and greater mitophagy compared to distal convoluted tubules (DCT)25–26. However, the mitochondrial content of DCT is higher than PCT26, suggesting that the degree of mitophagy is not entirely dependent on the mitochondrial mass of a cell. The mitochondrial membrane potential of PCT is lower than that of DCT27. In addition, PCT display a higher production of mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species (mROS) than DCT27. These findings suggest that lower mitochondrial membrane potential and higher mROS production in the tubules are directly related to the activation of mitophagy during AKI.

Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury-induced AKI

The ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI)-induced AKI is common in patients undergoing kidney transplantation28. The mitochondrial dysfunction exerts a critical role in worsening IRI-induced AKI. The mitochondrial content of proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTEC) decreased after renal IRI29, suggesting that mitophagy is active during AKI. Tan and colleagues confirmed that the mitophagy in PTEC increased following IR-induced kidney injury16. The deficiency of mitophagy modulators, i.e. PINK1 and Parkin, exaggerated the mitochondrial injury, oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in tubular cells after IRI16, suggesting that mitophagy is protective against AKI. The mitochondrial fusion protein MFN2, but not MFN1, is known to promote mitophagy3,10. However, Gall et al. reported that the proximal tubule-specific conditional deletion of Mfn2 resulted in improved renal function and better survival after IRI30, challenging the role of MFN2 in mitophagy or the role of mitophagy during AKI. Interestingly, the study by the same group previously reported that the PTEC from kidney-specific Mfn2 knockout mice showed mitochondrial fragmentation with no change in the renal function under non-stress conditions31. The inhibition of mitochondrial fission protein, dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) is known to induce mitophagy32. A study by Perry and colleagues showed that the proximal tubule-specific deletion of Drp1 protected against IRI-induced renal inflammation and apoptosis33, suggesting that the activation of mitophagy due to inhibition of mitochondrial fission may prevent AKI. Moreover, the protective effects of ischemic preconditioning (IPC) against IRI have also been attributed to activation of mitophagy with increased mitophagosome formation and clearance of damaged mitochondria. The mitophagy-dependent cytoprotection following simulated IPC in vitro was abolished in Pink1 knockdown proximal tubular cells34. These findings suggest that PINK1-dependent mitophagy exerts protective functions after IPC to prevent IRI-induced renal damage.

Contrast-induced AKI

The PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy has also been implicated to play protective roles during contrast-induced AKI (CIA). Mitophagy in the renal tubular epithelial cells was activated in both in vivo and in vitro models of CIA35. The deficiency of Pink1 or Prkn in tubular epithelial cells in the experimental CIA mice model resulted in a higher oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial damage, cell death, and tissue injury35. This study also confirmed that the activation of mitophagy after CIA prevented renal tubular epithelial cell death and tissue damage by suppressing the production of mROS and the activation of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome.

Cisplatin-induced AKI

The treatment with cisplatin, a chemotherapeutic agent that contributes to nephrotoxicity and AKI, resulted in increased expression of PINK1 and Parkin17, indicating that mitophagy is induced after cisplatin treatment. Cisplatin-treated Pink1 and Prkn knockout mice displayed severe kidney damage, and loss of renal function, suggesting that mitophagy exerts protective function against cisplatin-induced AKI17. However, a contrasting study showed that the deficiency of Pink1 prevented cisplatin-induced tubular damage and apoptosis36. The knockdown of Drp1 in human proximal tubular cell line (HK2) cells has also been shown to protect against cisplatin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis37, suggesting that the activation of mitophagy due to suppression of mitochondrial fission prevents cisplatin-induced mitochondrial damage. These studies suggest that mitophagy, by regulating damaged mitochondrial-derived oxidative stress prevents cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and loss of renal function.

Role of PINK1/Parkin-independent Mitophagy in AKI

The PINK1/Parkin-independent mitophagy does not require ubiquitin to recycle the damaged mitochondria. BNIP3 plays an essential role in the PINK1/Parkin-independent pathway of mitophagy18. The increase in the expression of BNIP3 in PTEC after IRI suggests that the BNIP3-dependent mitophagy is activated during AKI18–19. The expression of BNIP3 in PTEC and renal tubules increased after oxygen-glucose deprivation-reperfusion and IRI, respectively18. Bnip3 knockout mice after IRI displayed severe renal injury, higher oxidative stress, and accumulation of damaged mitochondria19. These observations in different experimental models of AKI suggest that the mitophagy is activated during AKI, and it maintains mitochondrial quality control and protects against oxidative stress-induced tubular damage.

Mitophagy in Chronic Kidney Disease

CKD is characterized by the progressive loss of renal function and the development of kidney fibrosis. The elevated mitochondrial fragmentation and mROS production have been reported during CKD14–15. Removal of superfluous mitochondria in the kidney is critically important to maintain cellular homeostasis. The accumulation of damaged mitochondria leads to increased oxidative stress-induced tubular apoptosis and kidney injury during CKD14. Here, we summarize the studies on functions of mitophagy in CKD, mainly focusing on its role in the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial fibrosis and diabetic nephropathy (DN).

Mitophagy in Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis

Kidney fibrosis represents a common pathological outcome of CKD38. Using two different experimental models, unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) and adenine diet, we have recently delineated the cytoprotective role of PINK1/MFN2/Parkin-dependent mitophagy against kidney fibrosis10. The expression of mitophagy regulators PINK1, MFN2, and Parkin in the kidney tissues was lower in the experimental models of kidney fibrosis as well as in patients with CKD10. Similarly, the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with CKD showed reduced expression of mitophagy regulatory proteins. Loss of either Pink1 or Prkn promoted renal extracellular matrix accumulation and kidney fibrosis induced by UUO or adenine diet10. Others have also reported the lower mRNA expression of PINK1, MFN2, and Parkin22, and higher production of mROS39 in PBMCs from CKD patients. In line with our observations, Li and colleagues recently showed that the deficiency of Pink1 or Prkn resulted in higher mROS production in hypoxia-treated HK2 cells and in the kidney after UUO that was associated with severe mitochondrial damage, increased renal tubule expression of transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1), and worsened tubulointerstitial fibrosis40. These findings provide further evidence for the protective role of mitophagy against kidney fibrosis. Interestingly, they also reported the upregulation of PINK1, Parkin, and LC3 II (a lipidated form of LC3 involved in mitophagosome formation) in the isolated mitochondrial fraction from the obstructed kidneys and hypoxia-treated HK2 cells40 that may represent a stress response. We had reported decreased expression of Parkin and LC3 II in the mouse whole kidney tissue lysate after UUO and the isolated mitochondrial fraction from TGF-β1-treated macrophages10. The seemingly contrasting findings might be that mitophagy functions in context and cell-type specific fashion, and warrant further investigations using corresponding conditional gene knockout mouse models. Nevertheless, both studies demonstrate that the deficiency of Pink1 or Prkn exacerbates mitochondrial damage and kidney fibrosis, indicating a renoprotective role of mitophagy.

We also uncovered the role of mitophagy in macrophages, which are one of the critical contributors to renal inflammation and fibrosis41. Our findings indicate that the deficiency of PINK1-dependent mitophagy resulted in a higher number of abnormal mitochondria in the renal macrophages and an increase in the frequency of renal profibrotic/M2 macrophages after UUO or adenine diet10. Similarly, TGF-β1-treated Pink1 deficient bone marrow-derived macrophages exhibited compromised mitochondrial respiration and higher mitochondrial-derived superoxide production. These observations highlight the role of PINK1-mediated mitophagy in maintaining macrophage mitochondrial quality control and homeostasis in the kidney. Although our understanding of the role of mitophagy in kidney fibrosis remains incompletely understood, investigations to date suggest that mitophagy is generally renoprotective and prevents the progression of kidney fibrosis.

Mitophagy in Diabetic Nephropathy

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is the chief cause of CKD in patients who progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and is characterized by clinical presentation of proteinuria, hypertension, and decline in kidney function42. Findings from preclinical studies indicate that renal impairment and oxidative stress in diabetic kidney disease (DKD) are closely linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and directly associated with the worsening of metabolic stress43. Studies also found that the expression of PINK1 and Parkin in the tubules of diabetic mice decreased while the mitochondrial fragmentation increased14,21. The LC3 puncta formation and the expression of PINK1 and mitochondrial fusion protein, MFN2 in the kidneys of streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice decreased while the expression of mitochondrial fission protein DRP1 and Fis1 increased14. These observations suggest that the mitophagy in the kidney during diabetic conditions was compromised, and there was an imbalance between mitochondrial fission/fusion processes. Similarly, mitophagy was suppressed in high-glucose treated human proximal tubular cells and in the kidneys of diabetic mice14,21. Xiao et al. also reported that the expression of MFN2 and LC3 II and the copy number of the mitochondrial DNA in the kidneys of diabetic (db/db) mice decreased while the expression of DRP1 increased21, suggesting that the mitophagy is impaired during DKD.

The mitochondrial fragmentation in renal mesangial cells also increased after high glucose treatment23. The mitophagy was negatively correlated with mROS production, mitochondrial fragmentation, and cell death14. Moreover, PBMCs from patients with DN showed reduced mitochondrial respiration, poor bioenergetic health index than diabetic patients without kidney disease22. The treatment with mitoquinone (MitoQ), an mROS scavenger, helped in partly restoring the expression of PINK1 and Parkin, and prevented mitochondrial damage and tubular injury during DKD21.

These observations indicate that mitophagy is impaired during CKD, and the activation of mitophagy may serve as a potential therapeutic approach in treating CKD and preventing disease progression.

Conclusion and Perspectives

Mitophagy by maintaining mitochondrial quality control has been shown to exert protective functions during both AKI and CKD. Recently published studies using global Pink1 or Prkn, or conditional Mfn2 knockout rodent models have sought to elucidate the functions of mitophagy regulators using different experimental settings of kidney diseases. However, a deeper understanding of the molecular regulation and function of mitophagy during different pathological conditions of the kidney is still warranted. Whether mitophagy occurs as a consequence of mitochondrial fission/fusion mechanism or is entirely an independent event, is still unclear. Additional studies need to determine the functions of mitochondrial fission/fusion machinery in modulating the regulation of mitophagy during kidney diseases. Strategies to enhance mitophagy may be a potential therapeutic approach that may help in attenuating damaged mitochondrial-derived production of ROS and cell death and thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

M.E.C is supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants R01 HL132198 and R01 HL133801.

Abbreviations Used

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- BNIP3

BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19kDa-interacting protein 3

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CIA

Contrast-induced AKI

- DCT

Distal convoluted tubules

- DKD

Diabetic kidney disease

- DN

Diabetic nephropathy

- DRP1

Dynamin-related protein 1

- ESRD

End-stage renal disease

- FUNDC1

FUN14 domain-containing protein 1

- IPC

Ischemic preconditioning

- IRI

Ischemia-reperfusion injury

- IMM

Inner mitochondrial membrane

- LIR

LC3B interacting region

- MMP

Matrix metalloprotease

- LC3

Microtubule-associated protein light chain 3

- MFN

Mitochondrial fusion protein

- mROS

Mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species

- MTS

Mitochondrial targeting signal

- NIX

NIP3-like protein X

- NLRP3

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like pyrin domain-containing protein 3

- OMM

Outer mitochondrial membrane

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PINK1

Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-induced kinase1

- PCT

Proximal convoluted tubules

- PTEC

Proximal tubular epithelial cells

- TGF-β1

Transforming growth factor-beta 1

- TOM

Translocase of the outer membrane

- TIM

Translocase of the inner membrane

- UUO

Unilateral ureteral obstruction

- VDAC

Voltage-dependent anion channel

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement:

The spouse of M.E.C. is a cofounder and shareholder, and serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of Proterris, Inc.

References

- 1.Bhargava P, Schnellmann RJ. Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017;13(10):629–646. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark SL Jr. Cellular differentiation in the kidneys of newborn mice studies with the electron microscope. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1957;3(3):349–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.3.3.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y, Dorn GW II. PINK1-Phosphorylated Mitofusin 2 is a Parkin Receptor for Culling Damaged Mitochondria. Science. 2013;340(6131):471–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1231031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka A, Cleland MM, Xu S, Narendra DP, Suen DF, Karbowski M. et al. Proteasome and p97 mediate mitophagy and degradation of mitofusins induced by Parkin. J Cell Biol. 2010;191(7):1367–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bingol B. and Sheng M. Mechanisms of mitophagy: PINK1, Parkin, USP30 and beyond. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;100:210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narendra DP, Kane LA, Hauser DN, Fearnley IM, Youle RJ. p62/SQSTM1 is required for Parkin-induced mitochondrial clustering but not mitophagy; VDAC1 is dispensable for both. Autophagy. 2010;6(8):1090–1106. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.8.13426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youle RJ, Narendra DP. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(1):9–14. doi: 10.1038/nrm3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Che R, Yuan Y, Huang S, Zhang A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathophysiology of renal diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2014;306(4):F367–F378. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00571.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhan M, Brooks C, Liu F, Sun L, Dong Z. Mitochondrial dynamics: regulatory mechanisms and emerging role in renal pathophysiology. Kidney Int. 2013;83(4):568–81. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatia D, Chung KP, Nakahira K, Patino E, Rice M, Torres L. et al. Mitophagy Dependent Macrophage Reprogramming Protects against Kidney Fibrosis. JCI Insight. 2019;4(23):132826. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.132826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei Q, Dong G, Chen JK, Rames G, Dong Z. Bax and Bak have critical roles in ischemic acute kidney injury in global and proximal tubule-specific knockout mouse models. Kidney Int. 2013;84(1):138–148. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks C, Wei Q, Cho SG, Dong Z. Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in acute kidney injury in cell culture and rodent models. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119(5):1275–1285. doi: 10.1172/JCI37829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall AM, Rhodes GJ, Sandoval RM, Corridon PR, Molitoris BA. In vivo multiphoton imaging of mitochondrial structure and function during acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2013;83(1):72–83. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhan M, Usman IM, Sun L, Kanwar YS. Disruption of renal tubular mitochondrial quality control by Myoinositol oxygenase in diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(6):1304–21. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gamboa JL, Billings FT 4th, Bojanowski MT, Gilliam LA, Yu C, Roshanravan B. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in patients with chronic kidney disease. Physiol Rep. 2016;4(9):e12780. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang C, Han H, Yan M, Zhu S, Liu J, Liu Z. et al. PINK1-PRKN/PARK2 pathway of mitophagy is activated to protect against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Autophagy. 2018;14(5):880–897. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1405880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Tang C, Cai J, Chen G, Zhang D, Zhang Z. et al. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is activated in cisplatin nephrotoxicity to protect against kidney injury. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(11):1113. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1152-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishihara M, Urushido M, Hamada K, Matsumoto T, Shimamura Y, Ogata K. et al. Sestrin-2 and BNIP3 regulate autophagy and mitophagy in renal tubular cells in acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;305(4):F495–509. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00642.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang C, Han H, Liu Z, Liu Y, Yin L, Cai J. et al. Activation of BNIP3-mediated mitophagy protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Death Dis. 2012;10(9):677. doi:0.1038/s41419-019-1899-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui J, Shi S, Sun X, Cai G, Cui S, Hong Q. et al. Mitochondrial autophagy involving renal injury and aging is modulated by caloric intake in aged rat kidneys. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao L, Xu X, Zhang F, Wang M, Xu Y, Tang D, Wang J. et al. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ ameliorated tubular injury mediated by mitophagy in diabetic kidney disease via Nrf2/PINK1. Redox Biol. 2017;11:297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhansali S, Bhansali A, Walia R, Saikia UN, Dhawan V. Alterations in mitochondrial oxidative stress and mitophagy in subjects with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:347. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Czajka A, Ajaz S, Gnudi L, Parsade CK, Jones P, Reid F et al. Altered Mitochondrial Function, Mitochondrial DNA and Reduced Metabolic Flexibility in Patients With Diabetic Nephropathy. EBioMedicine. 2015;11;2(6):499–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansell P, Welch WJ, Blantz RC, Palm F. Determinants of kidney oxygen consumption and their relationship to tissue oxygen tension in diabetes and hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40(2):123–37. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodger CE, McWilliams TG, Ganley IG. Mammalian mitophagy - from in vitro molecules to in vivo models. FEBS J. 2018;285(7):1185–1202. doi: 10.1111/febs.14336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McWilliams TG, Prescott AR, Allen GF, Tamjar J, Munson MJ, Thomson C. et al. mito-QC illuminates mitophagy and mitochondrial architecture in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2016;214(3):333–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201603039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall AM, Unwin RJ, Parker N, Duchen MR. Multiphoton imaging reveals differences in mitochondrial function between nephron segments. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(6):1293–302. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malek M, Nematbakhsh M. Renal ischemia/reperfusion injury; from pathophysiology to treatment. J Ren Inj Prev. 2015;4(2):20–27. doi: 10.12861/jrip.2015.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lan R, Geng H, Singha PK, Saikumar P, Bottinger EP, Weinberg JM. et al. Mitochondrial Pathology and Glycolytic Shift during Proximal Tubule Atrophy after Ischemic AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(11):3356–3367. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015020177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gall JM, Wang Z, Bonegio RG, Havasi A, Liesa M, Vemula P. et al. Conditional knockout of proximal tubule mitofusin 2 accelerates recovery and improves survival after renal ischemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015; 26: 1092–1102. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gall JM, Wang Z, Liesa M, Molina A, Havasi A, Schwartz JH. et al. Role of mitofusin 2 in the renal stress response. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e31074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliver D, Reddy PH. Dynamics of Dynamin-Related Protein 1 in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells. 2019,8(9):961. doi: 10.3390/cells8090961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perry HM, Huang L, Wilson RJ, Bajwa A, Sesaki H, Yan Z. et al. Dynamin-related protein 1 deficiency promotes recovery from AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018;29(1),194–206. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017060659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livingston MJ, Wang J, Zhou J, Wu G, Ganley IG, Hill JA. et al. Clearance of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy is important to the protective effect of ischemic preconditioning in kidneys. Autophagy. 2019;15(12):2142–2162. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2019.1615822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin Q, Li S, Jiang N, Shao X, Zhang M, Jin H, et al. PINK1-parkin pathway of mitophagy protects against contrast-induced acute kidney injury via decreasing mitochondrial ROS and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Redox Biol. 2019;26:101254. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Z, Ling Z, Yu Z, Xuan Y, Xiuping S, Tao Z. et al. PINK1 Deficiency Ameliorates Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Rats. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1225. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao C, Chen Z, Qi J, Duan S, Huang Z, Zhang C. et al. Drp1-dependent mitophagy protects against cisplatin-induced apoptosis of renal tubular epithelial cells by improving mitochondrial function. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):20988–21000. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Djudjaj S, Boor P. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of kidney fibrosis. Mol Aspects Med. 2019;65:16–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Granata S, Masola V, Zoratti E, Scupoli MT, Baruzzi A, Messa M. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation in dialyzed chronic kidney disease patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0122272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li S, Lin Q, Shao X, Zhu X, Wu J, Wu B. et al. Drp1-regulated PARK2-dependent mitophagy protects against renal fibrosis in unilateral ureteral obstruction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019:S0891–5849(19)31684–3. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang PM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. Macrophages: versatile players in renal inflammation and fibrosis. Nature Rev. Nephrol. 2019;15(3):144–158. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stadler M, Auinger M, Anderwald C, Kästenbauer T, Kramar R, Feinböck C. et al. Long-term mortality and incidence of renal dialysis and transplantation in type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(10):3814–20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saxena S, Mathur A, Kakkar P. Critical role of mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired mitophagy in diabetic nephropathy. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(11):19223–19236. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]