Abstract

Background

We compared quantification of MBF and myocardial flow reserve (MFR) with a 99mTc-sestamibi CZT-SPECT to 15O-water PET.

Methods

SPECT-MBF for thirty patients in the WATERDAY study were re-analyzed by QPET software with motion correction and optimal placement of the arterial input function. 15O–water PET MBF was re-quantified using dedicated software. Inter-operator variability was assessed using repeatability coefficients (RPC).

Results

Significant correlations were observed between global (r=0.91, p < 0.001) and regional MBF (r=0.86, p < 0.001) with SPECT compared to PET. Global MBF (rest 0.95 vs. 1.05 ml/min/g, p=0.07; stress 2.62 vs. 2.68 ml/min/g, p=0.17) and MFR (2.65 vs. 2.75, p=0.86) were similar between SPECT and PET. Rest (0.81 vs 0.98 ml/min/g, p=0.03) and stress MBF (1.98 vs. 2.61 ml/min/g, p=0.01) in right coronary artery (RCA) were lower with SPECT compared to PET. However, MFR in the RCA territory was similar (2.54 vs. 2.77, p=0.21). The SPECT-PET RPC for global MBFs and MFR were 0.95 ml/min/g and 0.94, with inter-observer RPC of 0.59 ml/min/g and 0.74 respectively.

Conclusions

MBF and MFR derived from CZT-SPECT with motion correction and optimal placement of the arterial input function showed good agreement with 15O-water PET, as well as low inter-operator variability.

Keywords: myocardial blood flow, single photon emission computed tomography, positron emission tomography

INTRODUCTION

Myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) plays an important role in the diagnosis and management of coronary artery disease (CAD), with 7–8 million scans performed annually in the United States (1). SPECT quantification of ischemia as a regional perfusion deficit has important prognostic value.(2, 3) However, SPECT MPI is inherently insensitive to balanced ischemia due to left main disease or triple-vessel disease.(4)

Myocardial blood flow (MBF), which was initially estimated with positron emission tomography (PET), increases diagnostic accuracy for obstructive CAD (5), and improves prediction of adverse cardiovascular events compared to regional perfusion alone (6). While MBF obtained with PET is considered a gold standard, the potential clinical impact of measuring MBF with SPECT is high, since SPECT is used more widely than cardiac PET—representing over 95% of MPI (7). Cadmium-zinc telluride (CZT) SPECT camera systems have higher photon sensitivity compared to conventional Anger cameras (8, 9), which facilitate MBF measurements from early dynamic acquisitions (10–16).

We recently adapted QPET algorithms (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center) to quantify dynamic SPECT data, which also allows for motion correction and optimal positioning of the arterial input function (AIF). The aim of this study was to evaluate the quantification and interobserver variability of MBF and MFR with a CZT-SPECT camera, utilizing this new algorithm compared to 15O-water PET results using the WATERDAY study image dataset. (10)

METHODS

Study subjects

Details of the study population and the study protocol have been described previously (10). Briefly, from November 2014 to November 2016, 104 stable patients with positive exercise stress test or perfusion imaging who were referred for invasive angiography, were screened for WATER DAY trial (clinicaltrials.gov unique identifier NCT02278497). Among these patients, 45 patients with angiography-proven CAD and fractional flow reserve (FFR) measurements were enrolled in the trial. Thirty out of 45 patients underwent 99mTc-sestamibi SPECT and 15O-water PET within 30 days and are included in the current study. The study protocol was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee (CPP Nord-Ouest Ш, France), written informed consent was obtained from all the patients and the procedures were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Dynamic 99mTc-sestamibi CZT-SPECT acquisition protocol

Rest and stress dynamic images were acquired in list mode over 6 min. For rest imaging, approximately 37 MBq of 99mTc-sestamibi was used to position the patient’s heart within the field of view (17). Three MBq/kg was injected at a rate of 1–2 cm3/s using an automatic injector (Nemoto, Tokyo, Japan) and flushed by 30 mL of saline to ensure consistent delivery of a tight bolus. For stress imaging, 9 MBq/kg of 99mTc-sestamibi was injected after the administration of regadenoson (400 μg). Rest–stress dynamic acquisitions were completed within 75 min. Data were rebinned into 32 frames consisting of 21 × 3-sec, 1 × 9-sec, 1 × 15-sec, 1 × 21-sec, 1 × 27-sec and 7 × 30-sec frames. An ordered subset expectation maximization (OSEM) algorithm was used for image reconstruction with 4 iterations and 32 subsets.

MBF quantification by Dynamic 99mTc-sestamibi CZT-SPECT

A global myocardial region of interest (ROI) was placed semi-automatically to obtain the myocardial time activity curves from the summed dynamic image data, starting 2 minutes after the last frame images of the dynamic SPECT data (18). First, MBF was automatically derived by the software without motion correction and with the AIF positioned in the center of the LV cavity along the mitral valve (19). The 3D cylindrical region of interest (ROI) used for AIF extraction was automatically set in the LV cavity based on early uptake images, using a cube oriented along the long axis of the heart (19). Subsequently, operators manually corrected the motion effect on each set of dynamic frames and placed the 3D cylindric ROI, avoiding the overlap with the myocardial wall, in the center of left atrium (LA) cavity on the early frame images to obtain the AIF (Fig. 1). For each frame in each dataset, two operators (Y.O. and O.M) shifted the ROIs in the short-axis, horizontal long-axis, and vertical long-axis images in each of the 3-coordinate axes (x, y, z). The 99mTc-sestamibi model used a one-tissue compartment model with k2 set to 0 (equivalent to net retention model) (20) with blood-to-myocardium spillover fraction and myocardial partial-volume corrections (21). MBF is obtained by correcting the K1 values for the flow-dependent extraction fraction based on the model by Leppo et al (20). Regional analysis was performed with standardized myocardial wall segmentation for the left anterior descending (LAD), left circumflex (LCX) and right coronary artery (RCA)(22). Two operators independently performed MBF quantification by dynamic 99mTc-sestamibi CZT-SPECT using motion correction and optimal AIF placement. The operators were blinded to clinical information, PET MBF results, and SPECT MBF results quantified by the other operator, with all analyses performed in a random order.

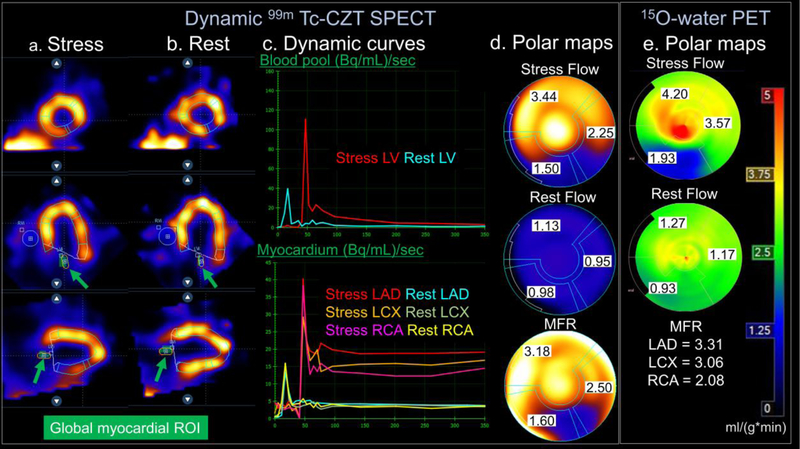

Figure 1. MBF quantification using dynamic 99mTc-CZT SPECT.

SPECT images at stress (a), and rest (b) showing a fixed regional perfusion deficit in the infero-basal segment. Global myocardial ROI are shown as green circles. Dynamic curves of blood pool and myocardium (c) and polar maps (d) demonstrate decreased stress myocardial blood flow in the RCA distribution which was confirmed with and 15O-water PET imaging (e).

Dynamic 15O-water PET acquisition protocol

Participants were instructed to fast for 4 h and abstain from caffeine, theophylline and cigarette smoking for 24 h. All PET acquisitions were performed using a GE Discovery VCT RX (GE Healthcare, Buc, France). After a low-dose transmission CT scan for attenuation correction (AC; helical coverage: 40 mm, rotation time: 0.5 s, pitch 0.516:1, table speed: 20.62 mm/rot, helical thickness: 3.75 mm, 120 kV and 10 mA, leading to a DLP of 15.35 mGy.cm and a radiation exposure of 0.21 mSv in all patients), a hand injection of 15O-water (1.5 to 3 MBq/kg) was performed at rest simultaneously with rest image acquisition. Pharmacological stress was induced by a bolus injection of regadenoson (400 μg), followed by a hand injection of 15O-water (1.5 to 3 MBq/kg) for the stress scan. PET scans were executed in 3 dimensional (3D) dynamic mode with a 24-frame (14 × 5 sec, 3 × 10 sec, 3 × 20 sec and 4 × 30 sec).

MBF quantification by 15O-water PET image analysis

Emission sinograms were corrected for random coincidences and dead time after Fourier rebinning and then reconstructed with the PET manufacturer’s attenuation and scatter correction using filtered back projection (Hanning filter, cut-off 8 mm). MBF values for 15O-water PET were re-quantified using dedicated software (Carimas, Turuk, Finland) (23) for the current study analysis, blinded to the results obtained for the WATERDAY study. Briefly, ROIs were drawn over the global left ventricle (LV) myocardium automatically. The ROI for AIF was placed in the center of LA cavity on the early uptake images. For each frame in each dataset, operators shifted the ROIs in the short-axis, horizontal long-axis, and vertical long-axis images in each of the 3-coordinate axes (x, y, z). Arterial and myocardial tissue activity curves were derived and were fitted to a single-tissue-compartment tracer kinetic model to calculate MBF for the global LV and for each coronary territory.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as median values with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers with percentages. The correlation of MBF values between SPECT and PET were assessed using linear regression analyses and Bland-Altman plots with calculation of the repeatability coefficient (RPC = 1.96 × standard deviation [SD] of differences). Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to evaluate the concordance between the MBF values obtained at each acquisition. Mann–Whitney U test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for intra-group comparisons as appropriate. Receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to evaluate the ability of SPECT-MFR quantification, with motion correction and optimal placement of the AIF, to predict reduced PET-regional MFR (<2.0 and <1.5). Optimal thresholds of SPECT-regional MFR to predict reduced PET-regional MFR were established using the Youden index. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was required for statistical significance. Statistical calculations were carried out using SAS (JMP version 13, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Hemodynamic data on SPECT and PET acquisitions

In total, 30 patients were included with population characteristics outlined in Table 1. The hemodynamic data from SPECT and PET acquisitions are presented in Table 2. There were no significant differences in any of the hemodynamic data, including heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and rate pressure product (RPP) between SPECT and PET data acquisitions.

Table 1.

Population characteristics

| (n = 30) | n (frequency %) |

|---|---|

| Male gender | 21 (70%) |

| Mean age ± SD (years) | 65 ± 7.1 |

| CAD risk factors | |

| BMI >30 | 8 (27%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (33%) |

| Hypertension | 20 (67%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 18 (60%) |

| Smoking history | 17 (57%) |

| Family history | 7 (23%) |

| >3 CAD risk factors | 15 (50%) |

| Chest pain | 15 (50%) |

| Medical Therapy | |

| Clopidogrel | 4 (13%) |

| Aspirin | 30 (100%) |

| β-blocker | 18 (60%) |

| ACE inhibitor or AT-II antagonist | 17 (57%) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 6 (20%) |

| Coumadin | 2 (7%) |

| Statin | 25 (83%) |

| Oral hypoglycemic agent | 12 (40%) |

| Long acting nitrate | 6 (20%) |

| Diuretic | 3 (10%) |

| Insulin | 3 (10%) |

ACE inhibitor= angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, AT-II antagonist= angiotensin receptor blocker, BMI= body mass index, CAD= coronary artery disease, SD= standard deviation

Table 2.

Hemodynamic data during CZT-SPECT and PET Acquisitions

| CZT-SPECT | PET | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | |||

| HR (bpm) | 64.3±12.3 | 65.5±13.2 | 0.23 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 123.9±21.3 | 125.2±20.0 | 0.20 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 64.1±10.5 | 61.7±7.8 | 0.06 |

| RPP (bpm x mmHg) | 7936.9±1755.2 | 7865.9±1691.8 | 0.22 |

| Stress | |||

| HR (bpm) | 82.0±20.1 | 80.15±20.3 | 0.28 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 131.03±22.7 | 130.20±18.3 | 0.37 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 64.3±12.5 | 61.2±9.1 | 0.07 |

| RPP (bpm x mmHg) | 11074.6±3043.7* | 9741.2±4136.9 ** | 0.26 |

Values are shown as mean ± SD.

p=0.0004 (rest RPP vs stress RPP) on SPECT

p=0.001 (rest RPP vs stress RPP) on PET

DBP= diastolic blood pressure, HR= heart rate, RPP= rate pressure product, SBP= systolic blood pressure

MBF quantification by 99mTc-sestamibi CZT-SPECT and 15O-Water PET MBF

Table 3 compares MBF and MFR measurements between SPECT and PET. Global MBF at rest and stress, and both global and regional MFR were similar between SPECT and PET (p for all= not significant). Regional MBF was also similar in the LAD and LCX territories at stress and LAD territory at rest, while it was underestimated by SPECT in the RCA territory at stress (p=0.01) and the LCX (p=0.01) and RCA territories (p=0.03) at rest.

Table 3.

Comparisons in MBF and MFR between CZT-SPECT and PET

| CZT-SPECT | PET | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest MBF (ml/min/g) | Global | 0.95 (0.80–1.06) | 1.05 (0.85–1.20) | 0.07 |

| LAD | 1.00 (0.84–1.17) | 1.12 (0.86–1.29) | 0.14 | |

| LCX | 0.89 (0.76–1.08) | 1.08 (0.91–1.26) | 0.01 | |

| RCA | 0.81 (0.68–0.92) | 0.98 (0.73–1.08) | 0.03 | |

|

| ||||

| Stress MBF (ml/min/g) | Global | 2.62 (1.87–2.91)* | 2.68 (1.94–3.67)* | 0.17 |

| LAD | 2.66 (1.86–3.08)* | 2.62 (2.00–3.76)* | 0.52 | |

| LCX | 2.40 (1.82–2.86)* | 2.65 (2.27–3.59)* | 0.15 | |

| RCA | 1.98 (1.44–2.76)* | 2.61 (1.99–3.60)* | 0.01 | |

|

| ||||

| MFR | Global | 2.65 (2.10–3.21) | 2.75 (2.03–3.37) | 0.86 |

| LAD | 2.54 (2.11–3.30) | 2.56 (1.85–3.24) | 0.71 | |

| LCX | 2.78 (2.17–3.19) | 2.72 (2.10–3.20) | 0.80 | |

| RCA | 2.54 (1.96–3.32) | 2.77 (2.20–3.55) | 0.21 | |

Values are shown as median (interquartile range).

CZT= cadmium zinc telluride, LAD= left anterior descending coronary artery, LCX= left circumflex coronary artery, MBF= myocardial blood flow, MFR= myocardial flow reserve, PET= positron emission tomography, RCA= right coronary artery, SPECT= single photon emission computed tomography

p < 0.0001 vs. Rest MBF

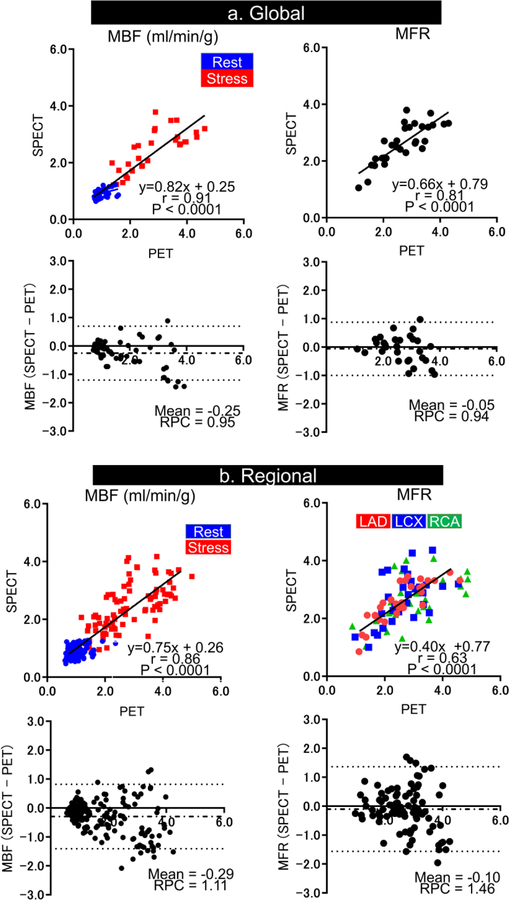

Figure 2 shows correlation and Bland Altman plots of MBF and MFR between CZT-SPECT and PET. The global MBF (r=0.91, p < 0.001) and MFR (r=0.81, p < 0.001) values obtained from CZT-SPECT correlated well with those obtained from 15O-water PET (Fig. 2a). RPC for global MBF was 0.95 ml/min/g and 0.94 for global MFR. The regional MBF (r=0.86, p < 0.001) and MFR (r=0.63, p < 0.001) values by CZT-SPECT also correlated well with PET measurements (Fig. 2b). RPC for regional estimation was 1.11 ml/min/g for MBF and 1.46 for MFR. The motion correction and optimal placement of the arterial input function was performed for dynamic SPECT data at stress and rest in all 30 patients. The fraction of stress studies that required motion correction ≥5mm in any axes and any frames was similar to rest studies (Stress: 93% vs. Rest: 83%, p=0.23). Global and regional MBF by CZT-SPECT demonstrated comparatively worse correlation with 15O-Water PET measurements if only optimal AIF was placed and motion correction was not performed (r=0.65, p<0.0001 for global estimates and r=0.63, p<0.0001 for regional estimates). The MBF after MC decreased from 2.54 ± 0.84 to 2.36 ± 0.83 ml/g/min at stress (p=0.14) and from 0.99 ± 0.19 to 0.91 ± 0.21 ml/g/min at rest (p=0.001).

Figure 2. Correlation between CZT-SPECT and 15O-water PET.

Correlation and Bland-Altman analyses of SPECT compared to PET MBF and MFR measurements for global (a) and regional (b) values.

CZT= cadmium zinc telluride, LAD= left anterior descending coronary artery, LCX= left circumflex coronary artery, MBF= myocardial blood flow, MFR= myocardial flow reserve, PET= positron emission tomography, RCA= right coronary artery, RPC= repeatability coefficient, SPECT= single photon emission computed tomography

ROC analysis per regional analysis demonstrated that the AUC of SPECT regional-MFR with motion correction and optimal placement of the AIF was 0.89 [0.79–0.98] for the detection of PET regional MFR <2.0, and 0.96 [0.91–1.00] for the detection of PET regional MFR <1.5. Optimal cutoffs of SPECT regional MFR were 2.18 for the detection of PET-regional MFR<2.0 (sensitivity 85.0 %, specificity 87.1%) and 2.13 for the detection of PET-regional MFR<1.5 (sensitivity 100.0%, specificity 81.7%).

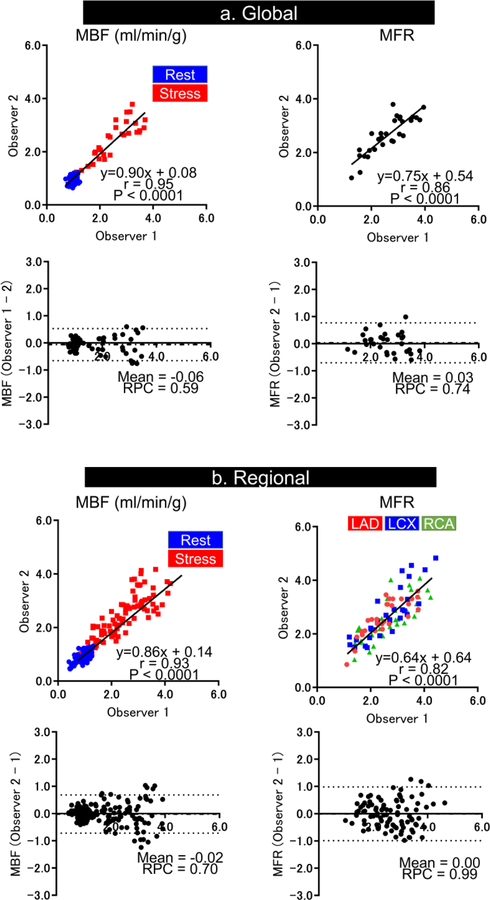

Inter-Operator Variability of CZT-SPECT

Figure 3 shows correlation and Bland-Altman plots for global and regional MBF and MFR by CZT-SPECT between two operators. The plots demonstrate high correlation coefficients for global (r=0.95 for MBF and r=0.86 for MFR) and regional estimates (r=0.93 for MBF and r=0.82 for MFR). RPC for global MBF was 0.59 ml/min/g and 0.70 ml/min/g for regional MBF estimation, while RPC for MFR was 0.74 for global estimates and 0.99 for regional estimates.

Figure 3. Inter-operator variability in MBF and MFR quantification by 99mTc-dynamic CZT-SPECT.

Correlation and Bland-Altman analyses in MBF and MFR measurements for global (a) and regional (b) values between two observers.

CZT= cadmium zinc telluride, LAD= left anterior descending coronary artery, LCX= left circumflex coronary artery, MBF= myocardial blood flow, MFR= myocardial flow reserve, PET= positron emission tomography, RCA= right coronary artery, RPC= repeatability coefficient, SPECT= single photon emission computed tomography

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown the feasibility of MBF quantification from CZT-SPECT using a new PET-based software application. We were able to adjust SPECT MBF measurements for the extraction fraction of 99mTc, with motion correction and optimal placement of the AIF. We show that both MBF and MFR values correlated well with 15O-water PET and demonstrated high inter-operator reproducibility. In addition, the sensitivity and specificity of CZT-SPECT MFR for the detection of reduced PET-MFR were excellent. Lastly, the optimal thresholds for detection of reduced regional MFR by PET in our study (2.18 for PET-MFR<2.0 and 2.13 for PET-MFR<1.5) were similar to the thresholds for CZT-SPECT MFR to predict abnormal FFR reported in the WATERDAY study (cutoff 2.1) (10).

Multiple reports have demonstrated the feasibility of SPECT MBF quantification (10–16, 24–27). Two studies have performed head-to head comparisons between SPECT with a CZT camera system and PET. Nkoulo et al. studied 28 patients who underwent 99mTc-tetrofosmin CZT-SPECT and 13N-ammonia PET using the PMOD software package (PMOD technologies Ltd, Zurich, Switzerland) (15). There was moderate correlation, assessed using Spearman’s correlation, between SPECT and PET for stress (ρ=0.51, p<0.001) and rest (ρ=0.30, p= not significant) measurements. Stress MBF was underestimated by SPECT at high flow conditions, resulting in underestimation of MFR. However, the authors did not correct for the extraction fraction of 99mTc, which is a significant limitation of SPECT MBF measurements, particularly at high flows. The WATERDAY study compared MBF quantification between 99m Tc-sestamibi CZT-SPECT and 15 O-water PET. They demonstrated good correlation in MBF and MFR between SPECT and PET using Corridor 4DM software (INVIA, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) (10). Correlation coefficients between SPECT and PET was r=0.83 for MBF (p<0.001) and r=0.75(p <0.001) for MFR, with a mean difference of 0.33 for MBF and 0.13 for MFR (10). In contrast to results from Nkoulo et al. global stress MBF by 99mTc-sestamibi CZT-SPECT was higher compared to 15O-water PET values. In the same population as the WATERDAY study but with different software, we demonstrated slightly better correlation between SPECT and PET MBF (r=0.91 vs. r=0.83) and MFR (r=0.81 vs. r=0.75) with no significant differences in global MBF or MFR measurements between SPECT and PET. Our results provide critical external validation of the WATERDAY results, by demonstrating similar results with new software and different observers. These findings suggest that comparable measurements of MBF with PET and SPECT can be obtained by integrating corrections for extraction fraction with motion correction and optimal AIF placement. Previous studies have shown that myocardial spillover contamination of arterial input in the LV cavity was higher compared with the LA using 15O-water and nitrogen-13 ammonia PET (28, 29). In a different study, Vasquez et al assessed MBF quantification using various anatomic arterial inputs (30). They demonstrated that rest MBF in the LV cavity was higher than in the aorta or LA, while rest MBF in the LA was not significantly different from that in the aorta. These previous PET studies have shown that MBF quantification with positioning of the AIF to the left atrium is more accurate and reproducible.

While our global measurements of MBF and MFR were comparable between SPECT and PET, we demonstrated important regional differences. Rest MBF measurements were lower in the RCA and LCX territories by SPECT compared to PET and stress MBF was lower in the RCA territory. Interestingly, the WATERDAY study found higher SPECT MBF values at rest and stress in the LAD and LCX territories, but not the RCA. This may be due to the differences in software methods. Attenuation artifacts with CZT-SPECT camera systems are more common in the inferolateral and lateral wall (31), which may impact MBF measurements in these territories. Wells et al. demonstrated that CT attenuation correction improved the correlation between regional MBF by SPECT compared to PET, but led to worse correlation with global values.(11) Therefore attenuation correction may be particularly beneficial for the RCA and LCX territories, but does not seem to be necessary when considering global measurements.

Multiple previous PET studies have shown that patient motion is problematic for MBF measurement (32, 33). Wells et al has reported that motion correction improved the accuracy and precision of global and regional SPECT MBF measurements compared with PET (11). In the current study, two operators independently corrected motion using a semi-automated program which resulted in good correlation in for global (r=0.95 for MBF, r=0.86 for MFR) and regional estimates (r=0.93 for MBF, r=0.82 for MFR). Our results build upon the prior data demonstrating the importance of motion correction by comparing to 15O-water PET, the gold-standard for non-invasive MBF measurement (34–36). Additionally, our semi—automated approach may help decrease result variability, which may be particularly important for patients with serial testing.

Limitations

Out study has a few important limitations. The sample size was relatively small, but still demonstrates the feasibility of SPECT MBF measurements with the PET-based software. Attenuation correction has not been used, but previous studies have shown that attenuation correction does not significantly change global MBF measurements. Lastly, SPECT measurements were performed with a CZT camera system, which are not yet widely used, however there are over 800 of these systems currently installed worldwide and most cardiac replacement cameras are solid state.

New Knowledge Gained

Dynamic 99mTc-sestamibi CZT-SPECT allows MBF and MFR quantification, which correlate well with 15O-water values. There was close inter-operator correlation in MBF and MFR for global and regional estimations using this semi-automated approach.

Conclusions

Our quantitative method demonstrated a good correlation in MBF and MFR between 99mTc-sestamibi CZT-SPECT and 15O-water PET with high inter-operator reproducibility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Drs. Daniel Berman, Guido Germano and Piotr Slomka participate royalties for QPS software at Cedars-Sinai. Dr. Denis Agostini is a consultant for Spectrum Dynamics. The work was supported in part by the Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation. Dr. Miller receives funding support from the Arthur J E Child Fellowship grant.

Abbreviations;

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CZT

cadmium zinc telluride

- MBF

myocardial blood flow

- MFR

myocardial flow reserve

- MPI

myocardial perfusion imaging

- PET

positron emission tomography

- ROI

region of interest

- RPC

repeatability coefficient

- SPECT

single photon emission computed tomography

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- (1).Chen J. The frontiers of nuclear cardiology research. J Biomed Res 2013;27:437–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Berman DS, Hachamovitch R, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico JA, Wang FP et al. Incremental value of prognostic testing in patients with known or suspected ischemic heart disease: a basis for optimal utilization of exercise technetium-99m sestamibi myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26:639–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico JA, Friedman J et al. Exercise myocardial perfusion SPECT in patients without known coronary artery disease: incremental prognostic value and use in risk stratification. Circulation 1996;93:905–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Berman DS, Kang X, Slomka PJ, Gerlach J, de Yang L, Hayes SW et al. Underestimation of extent of ischemia by gated SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with left main coronary artery disease. Journal of Nuclear Cardiology 2007;14:521–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Yoshinaga K, Katoh C, Manabe O, Klein R, Naya M, Sakakibara M et al. Incremental diagnostic value of regional myocardial blood flow quantification over relative perfusion imaging with generator-produced rubidium-82 PET. Circ J 2011;75:2628–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Farhad H, Dunet V, Bachelard K, Allenbach G, Kaufmann PA, Prior JO. Added prognostic value of myocardial blood flow quantitation in rubidium-82 positron emission tomography imaging. European heart journal cardiovascular Imaging 2013;14:1203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Levin DC, Parker L, Halpern EJ, Rao VM. Recent Trends in Imaging for Suspected Coronary Artery Disease: What Is the Best Approach? Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR 2016;13:381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sharir T, Ben-Haim S, Merzon K, Prochorov V, Dickman D, Ben-Haim S et al. High-Speed Myocardial Perfusion Imaging: Initial Clinical Comparison With Conventional Dual Detector Anger Camera Imaging. JACC Cardiovascular Imaging 2008;1:156–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Imbert L, Poussier S, Franken PR, Songy B, Verger A, Morel O et al. Compared Performance of High-Sensitivity Cameras Dedicated to Myocardial Perfusion SPECT: A Comprehensive Analysis of Phantom and Human Images. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2012;53:1897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Agostini D, Roule V, Nganoa C, Roth N, Baavour R, Parienti JJ et al. First validation of myocardial flow reserve assessed by dynamic (99m)Tc-sestamibi CZT-SPECT camera: head to head comparison with (15)O-water PET and fractional flow reserve in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. The WATERDAY study. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2018;45:1079–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wells RG, Marvin B, Poirier M, Renaud J, deKemp RA, Ruddy TD. Optimization of SPECT Measurement of Myocardial Blood Flow with Corrections for Attenuation, Motion, and Blood Binding Compared with PET. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2017;58:2013–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ben-Haim S, Murthy VL, Breault C, Allie R, Sitek A, Roth N et al. Quantification of Myocardial Perfusion Reserve Using Dynamic SPECT Imaging in Humans: A Feasibility Study. J Nucl Med 2013;54:873–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Han S, Kim YH, Ahn JM, Kang SJ, Oh JS, Shin E et al. Feasibility of dynamic stress (201)Tl/rest (99m)Tc-tetrofosmin single photon emission computed tomography for quantification of myocardial perfusion reserve in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2018;45:2173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ma R, Wang L, Wu D, Wang M, Sun X, Hsu B et al. Myocardial blood flow quantitation in patients with congestive heart failure: head-to-head comparison between rapid-rotating gantry SPECT and CZT SPECT. J Nucl Cardiol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- (15).Nkoulou R, Fuchs TA, Pazhenkottil AP, Kuest SM, Ghadri JR, Stehli J et al. Absolute Myocardial Blood Flow and Flow Reserve Assessed by Gated SPECT with Cadmium-Zinc-Telluride Detectors Using 99mTc-Tetrofosmin: Head-to-Head Comparison with 13N-Ammonia PET. J Nucl Med 2016;57:1887–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ben Bouallegue F, Roubille F, Lattuca B, Cung TT, Macia JC, Gervasoni R et al. SPECT Myocardial Perfusion Reserve in Patients with Multivessel Coronary Disease: Correlation with Angiographic Findings and Invasive Fractional Flow Reserve Measurements. J Nucl Med 2015;56:1712–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bellevre D, Manrique A, Legallois D, Bross S, Baavour R, Roth N et al. First determination of the heart-to-mediastinum ratio using cardiac dual isotope ((1)(2)(3)I-MIBG/(9)(9)mTc-tetrofosmin) CZT imaging in patients with heart failure: the ADRECARD study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2015;42:1912–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Germano G, Kavanagh PB, Chen J, Waechter P, Su HT, Kiat H et al. Operator-less processing of myocardial perfusion SPECT studies. J Nucl Med 1995;36:2127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Dekemp RA, Declerck J, Klein R, Pan XB, Nakazato R, Tonge C et al. Multisoftware reproducibility study of stress and rest myocardial blood flow assessed with 3D dynamic PET/CT and a 1-tissue-compartment model of 82Rb kinetics. J Nucl Med 2013;54:571–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Leppo JA, Meerdink DJ. Comparison of the myocardial uptake of a technetium-labeled isonitrile analogue and thallium. Circ Res 1989;65:632–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Nesterov SV, Deshayes E, Sciagra R, Settimo L, Declerck JM, Pan XB et al. Quantification of myocardial blood flow in absolute terms using (82)Rb PET imaging: the RUBY-10 Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7:1119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK et al. Standardized Myocardial Segmentation and Nomenclature for Tomographic Imaging of the Heart. Circulation 2002;105:539–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Nesterov SV, Han C, Maki M, Kajander S, Naum AG, Helenius H et al. Myocardial perfusion quantitation with 15O-labelled water PET: high reproducibility of the new cardiac analysis software (Carimas). Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2009;36:1594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Shrestha U, Sciammarella M, Alhassen F, Yeghiazarians Y, Ellin J, Verdin E et al. Measurement of absolute myocardial blood flow in humans using dynamic cardiac SPECT and 99mTc-tetrofosmin: Method and validation. Journal of nuclear cardiology : official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (25).Hsu B, Chen F-C, Wu T-C, Huang W-S, Hou P-N, Chen C-C et al. Quantitation of myocardial blood flow and myocardial flow reserve with 99mTc-sestamibi dynamic SPECT/CT to enhance detection of coronary artery disease. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2014;41:2294–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Klein R, Hung G, Wu T, Huang W, Li D, DeKemp R et al. Feasibility and Operator Variability of Myocardial Blood Flow and Reserve Measurements with 99mTc-Sestamibi Quantitative Dynamic SPECT/CT Imaging. Journal of nuclear cardiology : official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- (27).Wells RG, Timmins R, Klein R, Lockwood J, Marvin B, deKemp RA et al. Dynamic SPECT Measurement of Absolute Myocardial Blood Flow in a Porcine Model. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2014:(epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- (28).Hove JD, Iida H, Kofoed KF, Freiberg J, Holm S, Kelbaek H. Left atrial versus left ventricular input function for quantification of the myocardial blood flow with nitrogen-13 ammonia and positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2004;31:71–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Iida H, Rhodes CG, de Silva R, Araujo LI, Bloomfield PM, Lammertsma AA et al. Use of the left ventricular time-activity curve as a noninvasive input function in dynamic oxygen-15-water positron emission tomography. J Nucl Med 1992;33:1669–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Vasquez AF, Johnson NP, Gould KL. Variation in quantitative myocardial perfusion due to arterial input selection. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:559–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Oddstig J, Martinsson E, Jogi J, Engblom H, Hindorf C. Differences in attenuation pattern in myocardial SPECT between CZT and conventional gamma cameras. Journal of nuclear cardiology : official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (32).Hunter CR, Klein R, Beanlands RS, deKemp RA. Patient motion effects on the quantification of regional myocardial blood flow with dynamic PET imaging. Med Phys 2016;43:1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Hunter C, Klein R, Alessio AM, deKemp RA. Patient body motion correction for dynamic cardiac PET-CT by attenuation-emission alignment according to projection consistency conditions. Med Phys 2019;46:1697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Bergmann SR, Herrero P, Markham J, Weinheimer CJ, Walsh MN. Noninvasive quantitation of myocardial blood flow in human subjects with oxygen-15-labeled water and positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989;14:639–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Driessen RS, Danad I, Stuijfzand WJ, Schumacher SP, Knuuti J, Maki M et al. Impact of Revascularization on Absolute Myocardial Blood Flow as Assessed by Serial [(15)O]H2O Positron Emission Tomography Imaging: A Comparison With Fractional Flow Reserve. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11:e007417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Danad I, Raijmakers PG, Appelman YE, Harms HJ, de Haan S, van den Oever ML et al. Hybrid imaging using quantitative H215O PET and CT-based coronary angiography for the detection of coronary artery disease. J Nucl Med 2013;54:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.