To the Editor

Ophthalmologists at primary care centres and optometrists need to be guided by simple signs to recognise microspherophakia in a child early, in order to prevent vision-threatening complications. The ‘Ɛ’ sign is one such sign that can help in early disease recognition.

Microspherophakia is a bilateral congenital anomaly of lenses, wherein there is zonular laxity due to faulty development of secondary lens fibres during embryogenesis, leading to small spherical lenses. The visual outcomes are usually poor and marred by complications arising from very high-refractive myopia, lenticular subluxation, glaucoma, corneal decompensation and retinal detachment. Although the disease is congenital in nature, the mean age of presentation of microspherophakia is in the teens.

Owing to a myriad of complications that may occur with microspherophakia, the frequency of which increases with age, it is not surprising that 59% children may have glaucomatous disc damage at presentation. One-fifth eyes are blind due to glaucoma, which increases to one-third over time on follow-up, two-third blindness being contributed by glaucoma alone [1].

Since 90% individuals diagnosed with glaucoma are 30 years or younger, the frequency of complications can be minimised if the condition is diagnosed early, and patients are followed up regularly beginning at a young age. The hallmark of this condition is visibility of the equator of the lens on pharmacological mydriasis and triad of shallow anterior chambers, lenticular myopia and angle-closure glaucoma [2]. Additional criteria on adjunctive investigative modalities like Ultrasound Biomicroscopy (UBM) [3], such as zonular elongation (anterior zonular fibres >2 vs <1 mm normally), increased lens sphericity and ciliary body flattening in areas with missing zonules, and documentation of very high lens thickness on LensStar, IOL master, USG etc., may help confirm the diagnosis.

However, most primary and secondary eye care government-run hospitals lack facilities like UBM, and lens thickness measurements are required for accurate diagnosis of this condition. Furthermore, a comprehensive eye examination [4], which includes intraocular pressure testing and mydriatic examination, is uncommonly practiced in our country, more so for children, exaggerated by poor residency training and under utilisation of existing eye care facilities [5]. Optometrists who are often the primary contact for many seeking eye examination do not offer anything beyond refraction and spectacle prescription.

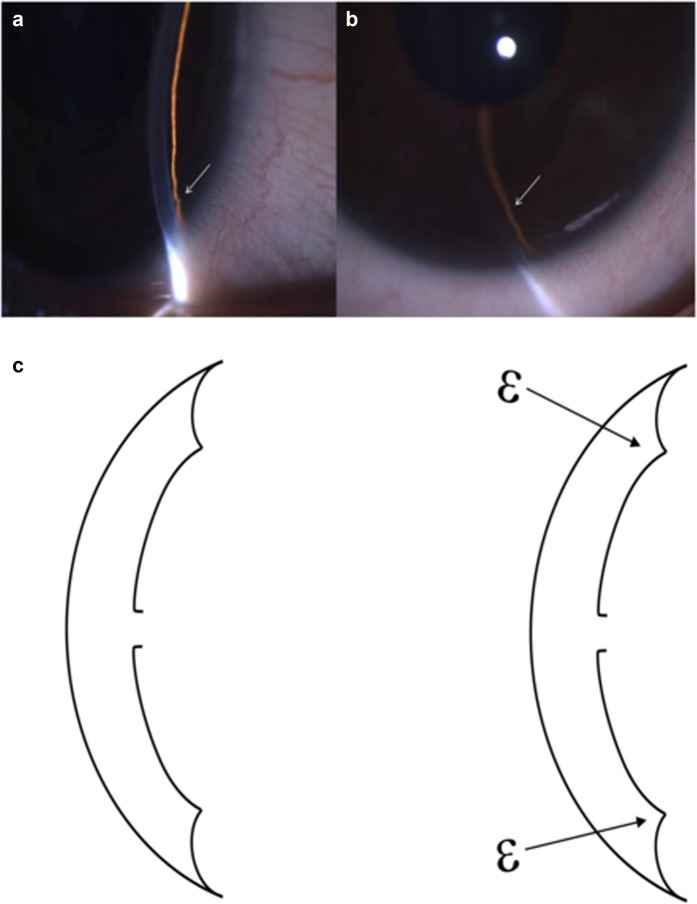

In order to combat this problem of poor detection rate till late, we describe a simple examination technique that can be used by optometrists and ophthalmologists alike to increase their suspicion of microspherophakia even in the absence of mydriatic testing. Due to the presence of small spherical lenses, the silhouette of the lenses can be detected in the undilated state by appreciating a sudden dip in iris contour in the periphery all around on slit-lamp biomicroscopy (Fig. 1a, b). This appearance simulates the Latin ‘Ɛ’ sign (Fig. 1c). The diagnosis later can be confirmed on UBM (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

a–c The arrows in slit-lamp biomicroscopy depict the iris groove caused by sudden dip in iris contour caused by a small spherical lens represented as the ‘Ɛ’ sign in the case of microspherophakia. Diagrammatic representation of the ‘Ɛ’ sign

Fig. 2.

UBM of the same patient confirming microspherophakia with an increased anteroposterior diameter, long anterior ciliary zonules and a shallow anterior chamber

Thus, very high non-axial myopia, very shallow anterior chambers of both eyes or aphakia in one eye and the presence of this ‘Ɛ’ sign on biomicroscopy should alert the primary contact to the possibility of microspherophakia. IOP and fundus examination techniques even if not available can be performed at a higher centre. The aim is to preserve as much vision as possible by early detection and treatment.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Senthil S, Rao H, Hoang N, Jonnadula G, Addepalli U, Mandal A, et al. Glaucoma in Microspherophakia. J Glaucoma. 2014;23:262–7. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3182707437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duke-Elder S. System of ophthalmology vol III normal and abnormal development part 2 congenital deformities. St Louis: The CV Mosby Co; 1963.

- 3.Lambiase A, Abdolrahimzadeh B, Calafiore S, Anselmi G, Mannino C, Mannino G. A review of the role of ultrasound biomicroscopy in glaucoma associated with rare diseases of the anterior segment. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:1453–9. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S112166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas R, Dogra M. An evaluation of medical college departments of ophthalmology in India and change following provision of modern instrumentation and training. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56:9–16. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.37589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nirmalan P. Utilisation of eye care services in rural south India: the Aravind Comprehensive Eye Survey. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1237–41. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.042606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]