Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is considered one of the most important foodborne bacterial pathogens causing food poisoning and related illnesses. S. aureus strains harbor plasmids encoding genes for virulence and antimicrobial resistance, but few studies have investigated S. aureus plasmids, especially megaplasmids, in isolates from retail meats. Furthermore, knowledge about the distribution of genes encoding replication (rep) initiation proteins in food isolates is lacking. In this study, the prevalence of plasmids in S. aureus strains isolated from retail meats purchased in Oklahoma was investigated; furthermore, we evaluated associations between rep families, selected virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes, and food source origin. Two hundred and twenty-two S. aureus isolates from chicken (n = 55), beef liver (n = 43), pork (n = 42), chicken liver (n = 29), beef (n = 24), turkey (n = 22), and chicken gizzards (n = 7) were subjected to plasmid screening with alkaline lysis and PFGE to detect small-to-medium sized and large plasmids, respectively. The S. aureus isolates contained variable sizes of plasmids, and PFGE was superior to alkaline lysis in detecting large megaplasmids. A total of 26 rep families were identified by PCR, and the most dominant rep families were rep10 and rep7 in 164 isolates (89%), rep21 in 124 isolates (56%), and rep12 in 99 isolates (45%). Relationships between selected rep genes, antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes, and meat sources were detected. In conclusion, S. aureus strains isolated from retail meats harbor plasmids with various sizes and there is an association between rep genes on these plasmids and the meat source or the antimicrobial resistance of the strains harboring them.

Keywords: Staphylococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, plasmid, retail meats, replicon, PFGE, megaplasmids, antimicrobial resistance

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus was discovered by the surgeon Sir Alexander Ogston in sepsis and abscess (Ogston, 1882), and has continued to be one of the most prominent and well-studied human pathogens in hospital and community infections. S. aureus occurs in the microflora of humans and animals, both on the skin and in the respiratory tract; however, it is also an opportunistic pathogen causing diseases that vary widely in severity (DeLeo and Chambers, 2009).

In the United States, S. aureus is one of the top foodborne pathogens and causes an estimated 241,000 illnesses per year (Scallan et al., 2011). Many food products become contaminated with S. aureus due to its ability to tolerate and grow under different stressful environments (Kadariya et al., 2014), and this can result in staphylococcal food poisoning due to the production of S. aureus enterotoxins (Argudín et al., 2010). On the other hand, multiple studies in the US have revealed a high prevalence of multidrug-resistant S. aureus strains (MDR) in retail meats (Waters et al., 2011; O’Brien et al., 2012; Jackson et al., 2013) indicating the potential threat for acquisition of virulent strains by meat industry workers. Furthermore, contaminated meat consumers might be at risk for MDR S. aureus colonization, and in rare cases may develop severe infections (Kluytmans et al., 1995) or act as healthy carriers for S. aureus transmission (Fritz et al., 2009). The meat production process can also contribute to the contamination of retail meats via workers, food animals, meat processing surfaces and equipment (Kadariya et al., 2014).

In the food chain, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) is the most significant mechanism for exchange of antimicrobial resistance and virulence determinants in bacterial populations (Aarestrup et al., 2008). In S. aureus, MGEs can be categorized into plasmids, transposons, insertion sequences, bacteriophages, pathogenicity islands, and chromosomal cassettes (Malachowa and DeLeo, 2010). S. aureus plasmids can confer resistance to antimicrobials, biocides, and heavy metals (Jensen and Lyon, 2009) and may encode host survival elements, virulence factors, and toxins (Malachowa and DeLeo, 2010). The acquisition of these different genetic elements in a single large plasmid can enhance adaptation and dissemination of S. aureus in different environments due to co-selective advantage (Wall et al., 2016). A recent study investigating ST239 MRSA strains evolution over the last 32 years revealed that plasmids coevolved with strains and enhanced resistance to multiple antibiotics (Baines et al., 2019).

The classification of plasmids by replicon typing has been a useful tool to investigate the dynamics of these molecules within bacterial populations in different ecological niches (Orlek et al., 2017). This system originally classified plasmids in vitro according to incompatibility (Inc.) groups, which is defined as the inability of plasmids with the same replication machinery to be hosted by the same bacterial cell (Novick, 1987). Inc. groups have been identified in Enterobacteriaceae (n = 27 Inc. groups), Pseudomonas (n = 14), and Staphylococcus (n = 18) (Shintani et al., 2015). PCR based replicon typing (PBRT) methods that target different replicon sequences have replaced the classic Inc. scheme. More recently, a PBRT scheme was developed for enterococci and staphylococci, which included 26 rep families and 10 unique families (Jensen et al., 2010; Lozano et al., 2012).

Despite years of study, our current understanding of plasmids and how they are distributed within S. aureus populations remains lacking. Most studies that have characterized S. aureus plasmids have been biased toward clinical strains, especially MRSA (Caddick et al., 2005; Kadlec and Schwarz, 2010; Shahkarami et al., 2014); whereas, those focusing on food or retail meats are extremely limited with respect to the role of extrachromosomal DNA. Furthermore, the ambiguity surrounding plasmid distribution in different species is likely due to inconsistent replicon typing schemes. Shintani et al. (2015) reported that only 8.4% of publicly available plasmids could be classified by the 26 rep families, and only few plasmids were classified by both rep family and Inc. group. Additionally, studies that used rep families for investigating S. aureus plasmids were biased toward European geographical origin and did not include diverse sources. For example, Lozano et al. (2012) investigated 92 S. aureus isolates originating from Spain and Denmark; only five isolates were from food sources (pigs). In another study, the sequences of 243 S. aureus plasmids available from the public domain were analyzed, but the source of the strains harboring the plasmids was largely unknown (McCarthy and Lindsay, 2012).

The aims of this study were several-fold. One objective was to determine the prevalence of plasmids in 222 S. aureus strains isolated from various Oklahoma retail meats. The aim was to understand how S. aureus plasmids are distributed in various ecological niches that are different from human and animal isolates. Secondly, the 222 strains were screened for various rep families to determine plasmid diversity. Finally, we sought to investigate possible links between rep families, retail meat origin, and antimicrobial resistance.

Materials and Methods

Strains Used for Plasmid Isolation

A total of 222 S. aureus strains were used in this study and were previously isolated from the following retail meats: chicken (n = 55), beef liver (n = 43), pork (n = 42), chicken liver (n = 29), beef (n = 24), turkey (n = 22), and chicken gizzards (n = 7). These strains were previously isolated and screened for antimicrobial susceptibility to 16 different antibiotics (Abdalrahman et al., 2015a, b; Abdalrahman and Fakhr, 2015). Resistance of these 222 S. aureus strains to the following twelve antimicrobials (azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, oxacillin, tetracycline, vancomycin, trimethoprim/sulfamethazole, clindamycin, penicillin, erythromycin, rifampin, and chloramphenicol) were reassessed following the most recent CLSI published breakpoints to determine any possible association with rep types (CLSI, 2019).

Isolation of Small Plasmids by Alkaline Lysis

Plasmids were isolated using a modified midi-preparation method as described previously for small plasmids (<60 kb) (Sambrook and Russell, 2001). Briefly, cells were grown in 15–20 ml of Luria Broth (LB) (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, United States) with agitation at 200 rpm at 37°C for 12–16 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 6 min, and pellets were re-suspended in 500 μl Tris-EDTA buffer (TE) (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8) (Amresco, Solon, OH, United States) and 3 μl of lysostaphin stock solution (1 mg/ml lysostaphin in 20 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States). After a 30-min incubation at 37°C in the water bath, 6 ml of alkaline lysis solution of pH 12.4 (TE buffer containing 0.1 N NaOH and 0.5% SDS) was added and mixed by inversion until the cell suspension was clear. A 3 ml solution of 3.0 M sodium Acetate, pH 5.2 (Sigma-Aldrich) was added, and the suspension was centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was then transferred to a fresh 50 ml tube, mixed with 9 ml of isopropanol and centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 rpm. After the supernatant was discarded, the plasmid DNA pellet was rinsed with 70% ethanol (5 ml), resuspended in 250 μl of TE buffer and then stored at −20°C. Plasmids were electrophoretically separated in 0.8% agarose gels (VWR, Radnor, PA, United States) at 120 V for 2.75 h; E. coli strains NCTC 50192 and 50193 and a 100 bp DNA ladder (Bioneer corporation, Alameda, CA, United States) were used as references and size standards, respectively. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide, and images were captured using a Bio-Rad Gel DocTM XR UV gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States).

Detection of Large Plasmids by Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis

Large plasmids (>60 kb) were screened by PFGE using protocols supplied by the CDC Pulse Net (McDougal et al., 2003; Marasini and Fakhr, 2014). Strains were grown in Typtic Soy Agar (TSA) (Himedia, Mumbai, India) at 37°C for 16–18 h, harvested by centrifugation, and resuspended in cell suspension buffer (CSB) (100 mM Tris, 100 mM EDTA, PH 8.0) to an OD of 0.9–1.1 at 610 nm. The adjusted cell suspension (200 μl) was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 3–4 min, the supernatant was decanted, and the pellet was resuspended in TE buffer (300 μl). The adjusted cell suspension incubated at 37°C for 10 min and then supplemented with 4 μl lysostaphin stock solution and 300 μl of 1.8% SeaKem Gold agarose (Lonza, Allendale, NJ, United States) in TE buffer (equilibrated to 55°C). This mixture was dispensed into the wells of plug molds and allowed to solidify at room temperature for 10–15 min. Plugs were then removed and transferred to a tube containing 3 ml of EC lysis buffer (6 mM Tris HCl, 1 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, 0.5% Brij 58, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% sodium lauroylsarcosine). After a 4-h incubation at 37°C, the EC lysis buffer was decanted and TE buffer (4 ml) was added; tubes were then agitated for 30 min at room temperature. The buffer was removed, and the washing was repeated three more times; after the final wash, 4 ml of TE buffer was added and samples were stored at 4°C. A small section was excised from the plugs and linearized with S1 nuclease as described previously (Marasini and Fakhr, 2014). The plugs were inserted into 1% agarose wells in TBE buffer and electrophoresed with XbaI Salmonella serovar Braenderup H9812 for 14 h in 0.5 X TBE as described (Marasini and Fakhr, 2014). Gels were stained and DNA bands were visualized as described above.

PCR Analysis of rep Genes

Total DNA was extracted by single cell lysing buffer (SCLB) as described previously (Marmur, 1961; Noormohamed and Fakhr, 2012). One colony from each TSA plate was mixed with 40 μl SCLB containing 1 ml of TE and 10 μl of 5 mg/ml proteinase K (Amresco, Solon, OH, United States). This mixture was incubated for 10 min at the following temperatures; 80, 55, and 95°C. Mixtures were then diluted (1:2) in double distilled water (80 μl) and centrifuged for 1 min at 4500 rpm. DNA samples were then screened for rep genes using seven multiplex PCRs for 26 different primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, United States) (Supplementary Table S1). These primers targeted rep genes of defined plasmid groups previously detected in Gram positive taxa (Jensen et al., 2010; Lozano et al., 2012). PCR reactions consisted of the following: Master Mix, 10 μl; sterile distilled water, 4 μl; primers, 1 μl each, and DNA template, 2 μl. Multiplex PCR was conducted as described (Abdalrahman and Fakhr, 2015), and stored at −20°C after PCR. Multiplex PCR products (10 μl) were loaded into 2% agarose gels containing 1X TAE buffer and separated by electrophoresis (140 V, 80 min); gels were stained and DNA bands were visualized as described above.

Statistical Analysis

A Chi-Square test of independence was performed to evaluate associations between plasmid rep families and meat sources (Sokal and Rohlf, 1995). This test posits that the occurrence of a rep-type in a meat-type is simply the relative-frequency of a particular rep-type × the relative-frequency of reps in particular meat type (multiplied by the sample size). The statistic calculation is that of any chi-square (X2 = ∑(oi−ei)2/ei) where oi = observed cell value and ei = expected cell value). This tests limits the number of cells that can have very small expected values, so we eliminated rep-types that were very rare (1, 3, 9, 10b), and the meat type with very few samples (chicken gizzards).

Results

Prevalence of Plasmids in S. aureus Strains

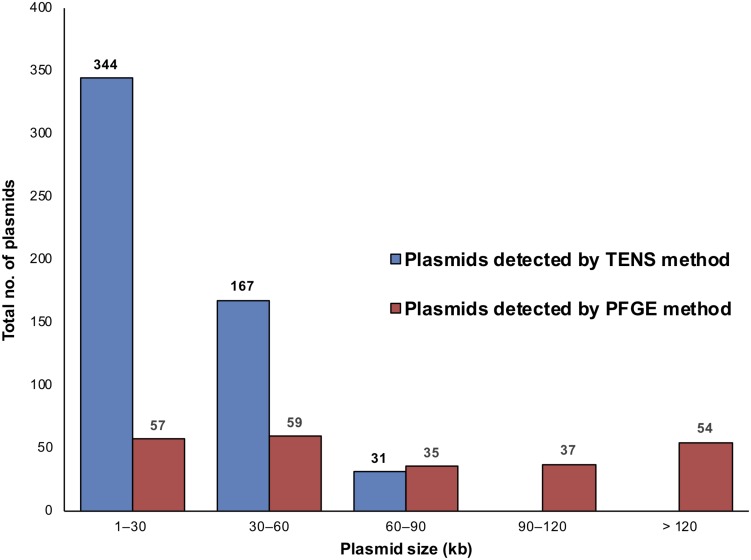

The plasmid content of 222 S. aureus isolates (55 chicken, 43 beef liver, 42 pork, 29 chicken liver, 24 beef, 22 turkeys, and 7 chicken gizzard) was analyzed using both alkaline lysis and PFGE (Table 1). PFGE was helpful in detecting large plasmids (Supplementary Figure S1), which were generally undetectable using the alkaline lysis method (Figure 1). For instance, among the 222 S. aureus isolates, alkaline lysis method (TENS) detected 542 plasmids smaller than 90 kb while PFGE identified only 151 plasmids within that size range. On the other hand, PFGE identified 91 plasmids larger than 90 kb. None of these plasmids have been detected by TENS method (Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

The prevalence of plasmids in S. aureus isolated from various retail meats by alkaline lysis (TENS) and PFGE.

| Source | No. of isolates |

No. of isolates with plasmids |

|||

|

Detected by TENS |

Detected by PFGE |

||||

| 2–60 kb | >60 kb | 2–60 kb | >60 kb | ||

| Chicken | 55 | 55(100%) | 4(7.3%) | 30(54.0%) | 27(49.1%) |

| Beef liver | 43 | 43(100%) | 4(9.3%) | 11(25.6%) | 19(44.2%) |

| Pork | 42 | 42(100%) | 7(16.7%) | 11(26.2%) | 19(45.2%) |

| Chicken liver | 29 | 29(100%) | 3(10.3%) | 13(44.8%) | 15(51.7%) |

| Beef | 24 | 24(100%) | 2(8.3%) | 6(25.0%) | 8(33.3%) |

| Turkey | 22 | 22(100%) | 10(45.4%) | 15(68.2%) | 12(54.5%) |

| Chicken gizzard | 7 | 7(100%) | 1(14.3%) | 2(28.6%) | 1(14.3%) |

| Total | 222 | 222(100%) | 31(14.0%) | 88(39.6%) | 101(45.5%) |

FIGURE 1.

The distribution of plasmids in the 222 S. aureus isolates according to plasmid size and method of detection, TENS and PFGE. Each method type is denoted by a different color, as shown in the color code at the right. The horizontal axis distributes plasmids according to the size windows shown. The vertical axis denotes the number of plasmids in each size window. Here, more plasmids were seen than the number of isolates as some isolates contained multiple plasmids.

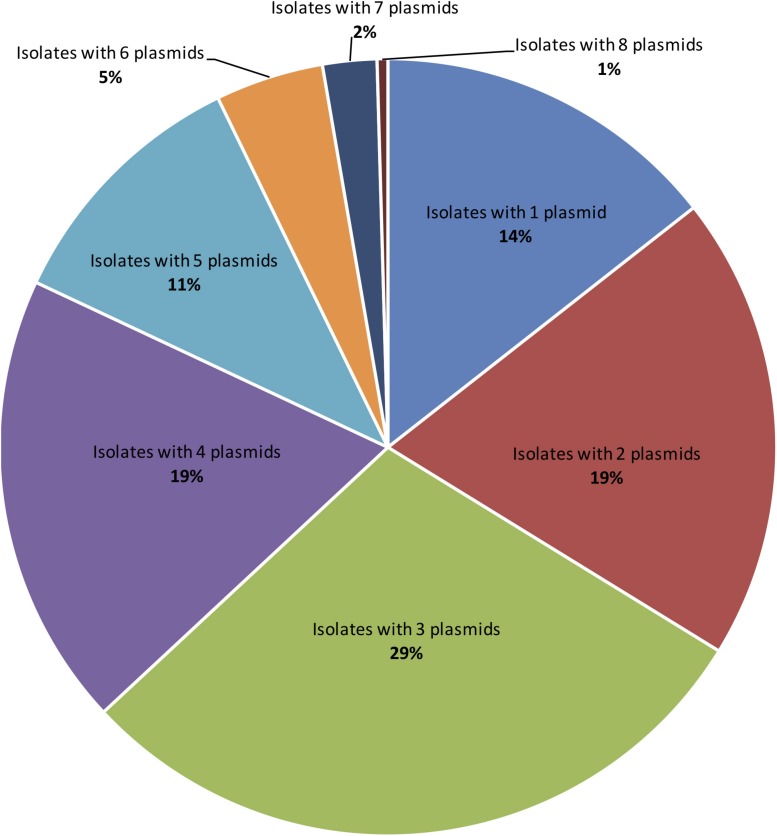

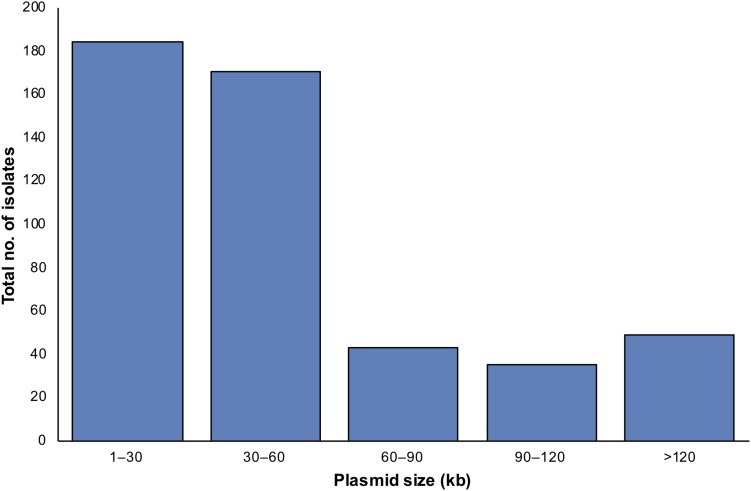

Applying both methods, all 222 S. aureus strains contained plasmids, with an average of four plasmids per isolate (Figure 2). Small-to-medium sized plasmids (1–60 kb) were most abundant among the isolates (Figure 3). For example, 184/222 of S. aureus strains contained 1–30 kb plasmids and 170/222 isolates harbored 30–60 kb plasmids. On the other hand, larger plasmids were less common among isolates; 43/222 of S. aureus trains harbored 60–90 kb plasmids, 35/222 contained 90–120 kb plasmids, and 49/222 harbored > 120 kb plasmids (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

The distribution of number of plasmids detected per a single S. aureus isolate applying TENS and PFGE methods. Each colored slice in the pie chart refers to counts of isolates with particular plasmid numbers. In case the same plasmid size were detected by both methods, only one plasmid was counted.

FIGURE 3.

The distribution of detected plasmids in S. aureus isolates according to plasmid sizes applying TENS and PFGE methods. In case the same plasmid size were detected by both methods, only one plasmid was counted.

Using PFGE, the highest prevalence of large plasmids (>60 kb) consecutively was; turkey isolates (12/22), chicken liver (15/29), chicken (27/55), pork (19/42), beef liver (19/43), beef (8/24), and 36 chicken gizzard (1/7) (Table 1). Furthermore, PFGE method was able to detect plasmids of size up to 336 kb (data not shown).

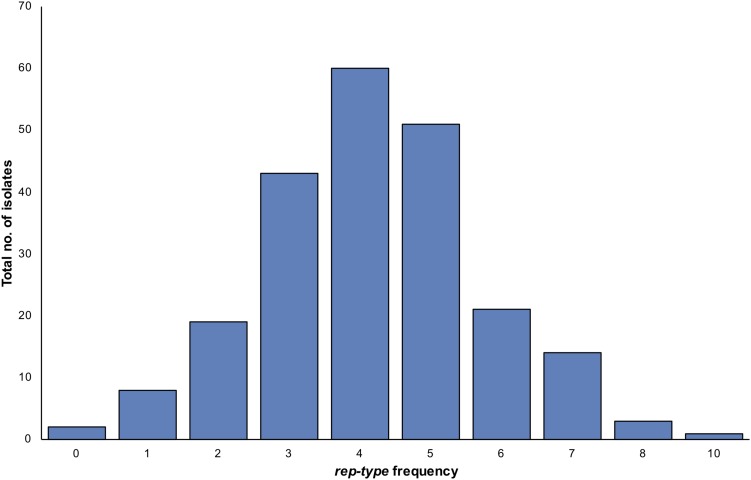

Plasmid rep Types

A total of 26 rep types (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 7b, 8, 9, 10, 10b, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24) were tested on the 222 S. aureus isolates (Supplementary Table S1). Seventeen rep types were detected among isolates while nine rep types were absent. When investigating the occurrence of a rep type on a single isolate, several S. aureus isolates harbored more than one rep type (Figure 4). One S. aureus isolates contained up to 10 rep types, while the majority of isolates were carrying four different rep types (Figure 4). Based on the assumption of one rep type per plasmid, some isolates showed more plasmids than rep types and vice versa. The most dominant rep types among S. aureus strains were rep10 andrep7 (n = 164), rep21 (n = 125), rep12 (n = 99), rep7b (n = 77), rep13 (n = 62), rep16 (n = 55), rep22 (n = 43), and rep20 (n = 40). Other rep types had a lower prevalence including rep5 (n = 31), rep19 (n = 19), rep15 (n = 18), rep6 (n = 17), rep9 (n = 9), rep1 (n = 3), rep3 (n = 1), and rep10b (n = 1). Positive amplicons were not identified for rep2, rep4, rep8, rep11, rep14, rep17, rep18, rep23 or rep24.

FIGURE 4.

The variation in numbers of plasmid rep types per a single S. aureus isolate. The frequency refers to counts of isolates with particular rep type numbers. Here, more rep types were seen than the number of isolates as some isolates contained more than one rep type.

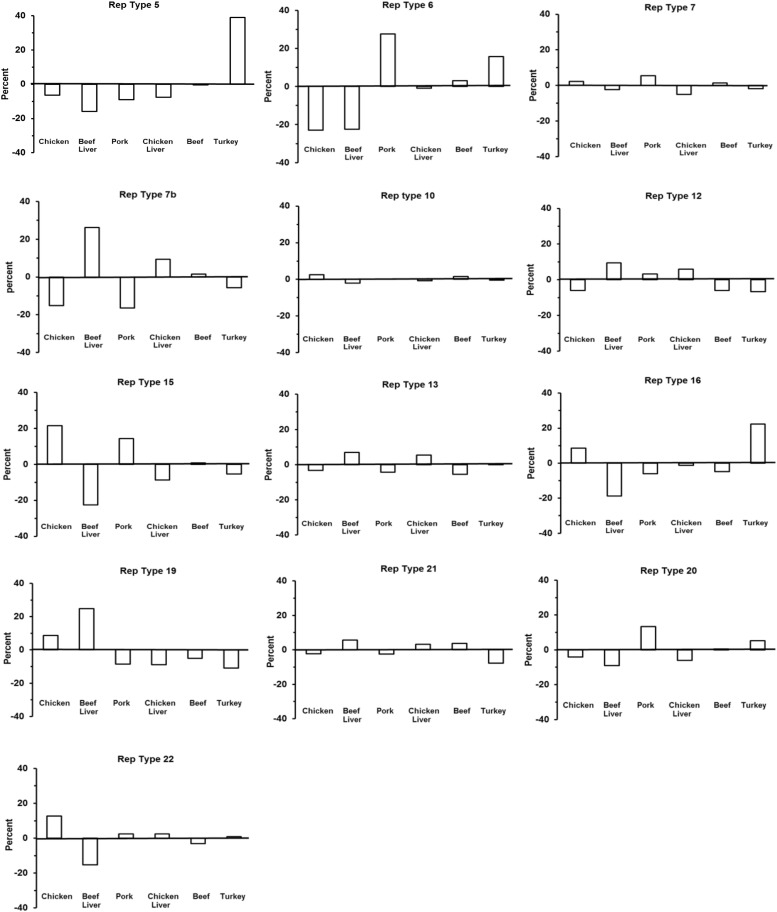

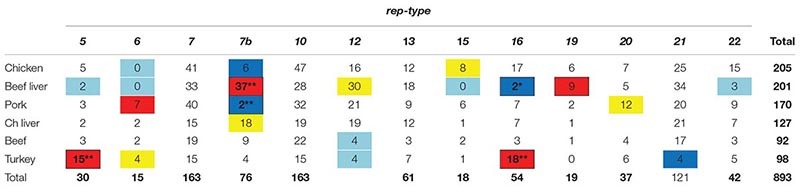

Distribution of rep Types According to Meat Origin

To test whether an association exists between S. aureus rep-types and meat origin, a chi-square test of independence was performed as described in the section “Materials and Methods.” Due to small sample size, chicken gizzard isolates were eliminated (which was n = 22 reps of any type), as well as rep 1 (n = 3), rep 3 (n = 1), rep 9 (n = 9) and rep 10b (n = 1) isolates of any meat origin. Distribution of rep-types was found not to be independent of meat origin (X2 = 232.3, df = 60, P < 0.0001).

Based on the results of the chi-square test of independence we wondered whether the significance of the test was due to (1) a rather uniform departure from expected across all cells of the test (cell = rep-type by meat-type), or (2) a situation where a few cells departed greatly from expected values, but most did not. To this end we created a heat-map depicting deviation of individual chi-square cell values to use as a visual guide (Table 2). The chi-square cell values are those which we had summed to give the chi-square statistic [i.e., the cell value is (oi−ei)2/ei]. Approximately 75% of the test of independence chi-square value (i.e., X2 = 232.3) was generated by about 27% (n = 21) of the individual chi square cell values. Thus, deviation from expected cell values did not appear to be uniformly distributed across table cells.

TABLE 2.

Data used for the chi-square test of independence between rep-type and meat origin.

|

Observed occurrence of rep-types in meats of different origins is shown. Meat origin and rep-type were shown not to be independent (X2 = 232.3, df = 60). The color overlay is a heat map visualizing cell departure from expected; they total 75% of the X2 = 232.3 value. Red denotes that a specific chi-square element (oi – ei)2/ei > 5, and yellow > 3 where the observed value was greater than expected. Dark-blue denotes (oi – ei)2/ei > 5, and light-blue > 3 where observed value was less than expected. **Denotes significant departures from expected using a familywise error of α = 0.05 based on the Holm–Bonferroni method. This test limits the number of cells that can have very small expected values, so rep types that were rare (1, 3, 9, 10b), and the meat type with few samples (chicken gizzards) were eliminated.

The visual results led us to test for significant departure from expect separately in each of the 27 cells identified in the heat-map. We used a binomial model based on the expected value of a cell to calculate the mean and standard error, and the Holm–Bonferroni method to control the familywise error associated with multiple comparisons (Holm, 1979). We used a familywise error of α = 0.05). This is a conservative test (prone to Type I errors: false negative), but slightly less so that the Bonferroni test (Holm, 1979). Even so, significant departures from expected were seen for rep 7b in beef liver, rep 7b in pork, rep 5 in turkey, and rep 16 in turkey. If the familywise error is relaxed to α = 0.06 then rep 16 in beef lever is also significant.

There were significant differences between some rep types and observed and expected frequencies for a certain meat origin, thus indicating a strong relationship (Table 2) (Figure 5). For example, a large, positive difference was observed for the following rep types and meat origins: rep5 and rep16, turkey; rep7b and rep19, beef liver; rep6, pork; and rep7b, chicken liver. Similarly, the absence of rep types in a specific meat origin was not random but instead more likely due to a strong interdependency between rep type and meat origin. Examples that support this statement include the absence of the following rep groups from selected meat origins: rep7b in pork and chicken isolates; rep16 in beef liver; rep21 in turkey; and rep22 and rep15 in beef liver isolates. Some rep types exhibited a reduced relationship (or lack of relationship) with meat sources including rep12 (beef liver; turkey), rep15 (chicken), rep20 (pork), rep6 (turkey; chicken and beef liver isolates), rep5 (beef liver), and rep7b (beef). Although rep types assigned to rep7 and rep10 occurred frequently in all meat types, there was not a significant association with a particular meat origin. Similarly, the frequency of rep13 was equal for the different meat types.

FIGURE 5.

The distribution of 13 rep families in S. aureus from six different meat sources. This chart is a visual representative for the chi-square results in Table 2.

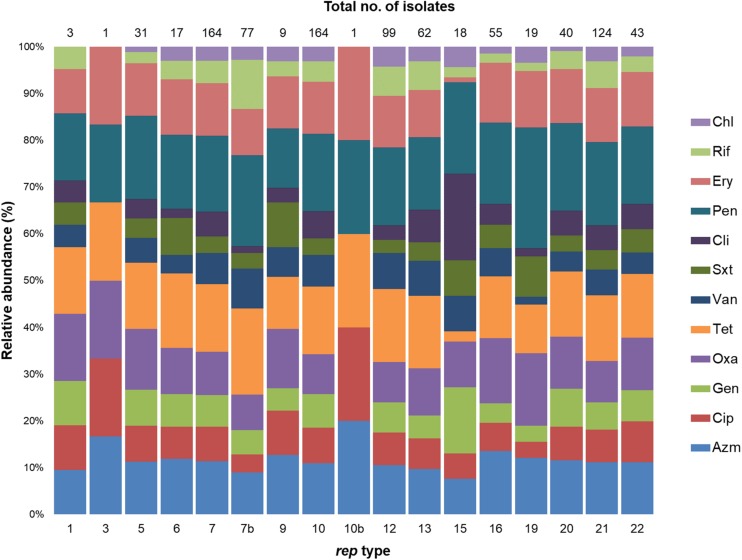

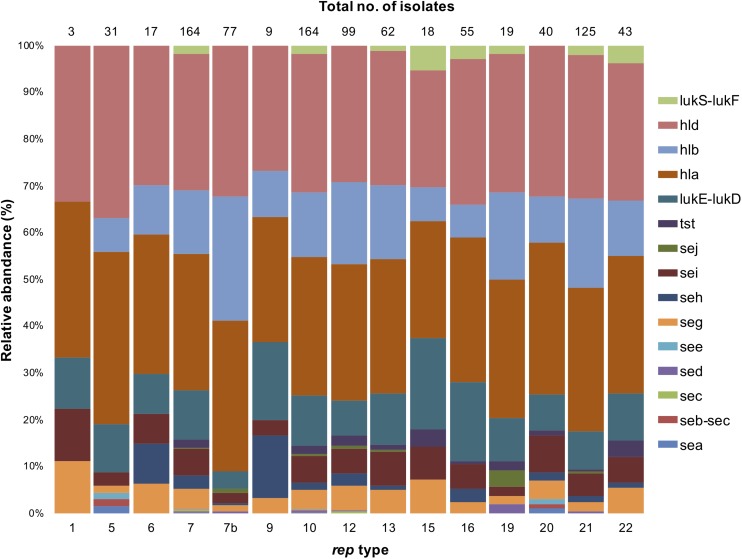

Distribution of Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Genes in rep Types

The 222 S. aureus strains used in this study were previously screened for antimicrobial susceptibility to 16 different antibiotics (Abdalrahman et al., 2015a, b; Abdalrahman and Fakhr, 2015). Resistance of these 222 S. aureus strains to the following twelve antimicrobials (azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, oxacillin, tetracycline, vancomycin, trimethoprim/sulfamethazole, clindamycin, penicillin, erythromycin, rifampin, and chloramphenicol) were reassessed following the most recent CLSI published breakpoints to determine any possible association with rep types (CLSI, 2019). The distribution of antimicrobial resistance in these 222 S. aureus isolates was as follows: penicillin, PenR (n = 159), tetracycline, TetR (n = 143), azithromycin, AzmR (n = 107), erythromycin, EryR (n = 105), oxacillin, OxaR (n = 88), ciprofloxacin, CipR (n = 68), vancomycin, VanR (n = 66), gentamicin, GenR (n = 62), rifampin, RifR (n = 50), clindamycin, CliR (n = 48), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, SxtR (n = 37), and chloramphenicol, ChlR (n = 28) (Abdalrahman et al., 2015a, b; Abdalrahman and Fakhr, 2015). Furthermore, these isolates were evaluated for the presence of 18 genes encoding toxins including hemolysins (hla, n = 195; hld, n = 195; hlb, n = 95), enterotoxins (sei, n = 45; seg, n = 31; seh, n = 15; sej, n = 2; sea, n = 1; seb, n = 1; sec, n = 1; sed, n = 1; see; n = 1), toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (tst, n = 9), leucocidins (lukE-lukD, n = 73; lukM, n = 0), Panton-Valentine leucocidin (PVL) (lukS-lukF, n = 8), and exfoliative toxins (eta and etb, n = 0).

The distribution of antimicrobial resistance genes in rep types is shown in Figure 6. All rep1 isolates were OxaR PenR TetR, but were sensitive to chloramphenicol. In isolates with rep5 amplicons, 97% were PenR, and most were also resistant to TetR (77%), OxaR (71%), EryR AzmR (61%). Strains with rep6 plasmids exhibited resistance to PenR TetR (94%) and EryR AzmR (71%). Similarly, 75 and 67% of rep7 isolates were resistant to PenR and TetR, respectively. Over 50% of isolates with rep7b amplicons were PenR TetR, with lower levels of resistance for other antimicrobial agents. Furthermore, rep7b was frequently identified in isolates resistant to Azm, Oxa, and Pen (89%); Ery, and Tet (78%); and Cip, and Sxt (67%). The rep10 and rep12 plasmids exhibited high levels of resistance to Pen (70–72%) and Tet (66–67%). rep13 exhibited PenR TetR. All rep15 strains were PenR and also showed resistance to CliR (94%), and GenR (72%). rep16 amplicons were highly resistant to Pen (84%), and also demonstrated 62-67% resistance to Oxa, Azm, Tet, and Ery. Isolates containing rep19 were PenR (79%), while resistance to other antibiotics was less frequent. Isolates with rep20 plasmids were PenR (98%), TetR (73%), and AzmR EryR (60%). For isolates with rep21 plasmids, PenR (93%), were predominant, followed by resistance to Tet (79%), Ery (65%), and Oxa Ery (63%).

FIGURE 6.

Stacked column bar graph showing the relative abundance of S. aureus isolates with antimicrobial resistance according to rep type. Antimicrobial resistance is differentiated by color as shown.

Although each rep type had a distinct resistance profile, PenR was common and ChlR, RifR and VanR were infrequent. Among AzmR isolates, the most dominant types were rep9 (89%); rep6 (71%); and rep5,rep16, rep20, andrep22 (60–65%). For isolates resistant to Cip and Sxt, rep9 was predominant (67% CipR SxtR), and rep15 was prevalent for CliR (97%) and GenR (72%). Oxacillin resistance was common in rep9 (89%), rep5 (71%), rep16 (67%), and rep22 (63%) amplicons. The rep6 amplicon was predominant among TetR and OxaR isolates (94% and 88%); while rep15 and rep19 were rare in TetR (11%) isolates. In EryR isolates, rep9 occurred at a high frequency (78%) compared to other rep types.

In general, toxin genes were relatively rare in S. aureus except for those encoding hemolysin; hla and hld were predominant among all rep types, except rep3 and rep10b. (Figure 7). While the distribution of hla and hld in rep isolates was similar (74–100%), hlb was more abundant in rep7b isolates (78%). Only isolates containing rep5,rep7, rep10 and rep20 were positive for enterotoxin genes sea, seb, and see (Figure 7). The sec gene was present in rep7 and rep12, sed was identified in rep7b, rep10,rep12, rep19, and rep21, and sej was in isolates containing rep7, rep7b, rep10, rep12–13, rep19, and rep21. Interestingly, seg and sei were identified in all rep types except rep3 and rep10b, and seh was present in all rep isolates with the exception of rep1,rep3, rep5, rep10b, rep15, and rep19.

FIGURE 7.

Stacked column bar graph showing the relative abundance of virulent S. aureus isolates according to the rep type. Isolates are denoted by different colors according to toxin genes as shown.

The toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 gene (tst) was identified in S. aureus isolates with rep7, rep10, rep12–13, rep15–16, rep19, and rep20–22 amplicons. The leucocidin genes, lukE-lukD, were associated with all rep types but rep3 and rep10b. The rep9,rep15, and rep16 plasmids were the most prevalent types carrying lukE-lukD (61, 56, and 53%, respectively). The PVL genes, lukS-lukF, were found exclusively in S. aureus isolates containing rep7, rep10, rep13, rep15–16, rep19, and rep21–22. It is important to note that while these PVL and lukS-lukF genes may be associated with strains carrying plasmids with the above-mentioned rep-types, these toxin genes may not be carried on these plasmids.

Discussion

Our understanding of S. aureus plasmids is biased toward clinical strains, and limited information is available regarding plasmids harbored by foodborne S. aureus, especially in retail meats. Furthermore, no standardized typing approach is available to classify plasmids from various bacterial species. In this study, a PCR-based approach targeting rep genes was used to investigate plasmids in 222 S. aureus isolated from seven different retail meats; the aim was to expand the current plasmid classification system for gram-positive bacteria and to analyze the distribution and prevalence of these plasmids.

Many genes associated with S. aureus survival and persistence are plasmid-encoded, including those associated with antimicrobial resistance, biofilm formation and toxin production (Bukowski et al., 2019). In this study, the plasmids in S. aureus strains from retail meats exhibited diverse rep types, which might confer a selective advantage. In other words, the presence of multiple plasmids encoding different virulence factors or resistance traits provide a selective advantage for the bacterial host in different environments (Carattoli, 2013). Some isolates contained plasmids that were not assigned to a rep type; this might be due to the presence of novel or mutated rep genes that were not be identified by the primers (Yano et al., 2016). On the other hand, some strains harbored more rep sequences than number of plasmids; this can be explained by plasmid integration or fusion with another plasmid (Monk and Foster, 2012), existence of more than one plasmid of a given size, or failure to identify a plasmid by alkaline lysis and PFGE. While the occurrence of rep genes likely indicates the presence of a particular plasmid type, definite conclusions cannot be derived and caution must be applied. Future studies using a whole genome sequencing approach are therefore recommended.

The majority of isolates in the present study harbored plasmids > 20 kb; large plasmids are key contributors to HGT and host adaptation to different environments (Haaber et al., 2017). Indeed, our study revealed a high occurrence of large plasmids in S. aureus populations isolated from retail meats. Large plasmids often encode a diverse range of virulence genes and genetic modules to ensure their stability within the host and facilitate transfer to other bacteria (Shearer et al., 2011). Recent studies demonstrated that larger plasmids undergo mutations in genes encoding plasmid replication initiation proteins to increase adaptation to bacterial hosts (Yano et al., 2016) or may acquire stabilizing traits from other resident plasmids (Loftie-Eaton et al., 2016). It is important to mention that S. aureus carries an efficient restriction-modification system to prevent the entry of unrecognizable DNA (Waldron and Lindsay, 2006); however, conjugative plasmids may avoid the S. aureus restriction system by losing restriction sites (Roberts et al., 2013). Although they play an important role in host survival, virulence, and gene exchange, the larger plasmids in S. aureus remain poorly studied. For example, a recent study showed that only the origin of replication in small plasmids was required for transfer to co-resident conjugative plasmids (O’Brien et al., 2012).

Our study shows that rep families are diverse among S. aureus meat isolates, and some rep types were more abundant than others. The two dominant rep families, rep7 and rep10, had no significant association with a particular meat product. These findings agree with a European study that reported identical rep families in S. aureus strains from humans, animals, and food (Lozano et al., 2012). Many commensal S. aureus strains can be shared between humans and food animals that can serve as reservoirs for rep plasmid families (Smith, 2015). Interestingly, the rep7b and rep12 types were fairly abundant in this study and were significantly linked to S. aureus isolated from liver. In the slaughterhouse, edible offal (internal organs) are prepared in the early stage of slaughtering, and many studies have suggested improper human processing and handling as primary sources for offal contamination (Im et al., 2016; Rouger et al., 2017). It is important to note that typing of S. aureus isolates was not conducted in this current study, and this is critical to accurately track the source of identified plasmids in retail meats.

In this study, selected rep families showed a remarkable specificity for certain meat origins, thus indicating that food animals can serve as reservoirs for these plasmids. We found that rep5 and rep16 were dominant types in turkey, rep6 in pork and turkey, rep15 in chicken, and rep20 in pork isolates. S. aureus strains occur as commensal organisms on the skin, nose and mucous membranes of food animals (Lozano et al., 2012) and food production animals are often colonized with specific S. aureus strains (Wall et al., 2016). When exposed to the selective pressure of antimicrobial use, S. aureus adapts by acquiring genes from other organisms and can become more persistent in the livestock production system. This was supported by the observed correlation between the above-mentioned rep families and isolates resistant to antimicrobials commonly used in food animals (e.g., Sxt and Tet). Another interesting result in the current study was the link between the rep6 type and multiple food animals, whereas other rep families were exclusive to a single source. In contrast to other rep types, the rep6 family is prevalent in broad-host-range plasmids (Jensen et al., 2010), which confirms the role of plasmids in distributing genes in S. aureus isolates. Although our study was restricted to S. aureus strains from retail meats, it suggests the potential role of food animals as a source for S. aureus plasmids in the meat pyramid.

Meat products may also become contaminated with S. aureus strains that harbor plasmids that originated from other gram-positive organisms. Surprisingly, rep3 and rep12 plasmid families were detected in the S. aureus strains analyzed in this study. These rep families were previously found in Bacillus spp. and are thought to have a narrow host range (Jensen et al., 2010). It is also noteworthy that the rep1 andrep9 amplicons, which were previously detected in few S. aureus strains, are naturally occurring in Enterococcus spp. (Jensen et al., 2010; Lozano et al., 2012). Plasmid transfer from Enterococcus or Bacillus spp. to S. aureus is not unusual and has been observed in previous studies (Gryczan et al., 1978; Zhu et al., 2010). Moreover, S. aureus produces a peptide known to induce bacterial clumping, which initiates HGT of Enterococcus spp. plasmids (Clewell et al., 1985). Other factors can also promote HGT between S. aureus strains such as the occurrence of other bacterial species with S. aureus strains. Both Bacillus and Enterococcus spp. are widespread in the farm environment and can be disseminated to the slaughterhouse by incoming animal carcasses or meat industry workers (Gutiérrez et al., 2012); HGT can occur in biofilms that form within meat production facilities or during colonization of livestock dermis or nasal cavities (Coimbra-E-Souza et al., 2019). Furthermore, the aforementioned plasmid families could harbor biological features that favor HGT into S. aureus strains. For example, the rep12 amplicon type is found in B. thuringiensis pBMB67 plasmids that encode conjugal transfer genes (Chao et al., 2007; Shintani et al., 2015), while the rep9 type was detected in E. faecalis conjugative plasmids (Jensen et al., 2010). Our findings support the contention that intergeneric transfer of plasmids occurs in the meat production chain under selection pressure. Thus, further research is needed to understand the conditions that promote plasmid transfer – if any – in the meat production industry with the aim of limiting the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes in meat-associated bacteria.

An association between rep families and antimicrobial resistance was observed in our study. McCarthy and Lindsay (2012) found a strong association between plasmid groups containing the rep15 sequence and the occurrence of tetK; whereas another study found the same rep type in TetR S. aureus isolates (Lozano et al., 2012). In our study, there was a high prevalence of the rep15 type in TetR strains. Furthermore, the association between rep6 andrep15 types and SxtR, the rep7b type and CipR, and the rep19 type and β-lactam resistance was in agreement with other studies and may indicate that the antimicrobial genes are plasmid-encoded (Lozano et al., 2012; McCarthy and Lindsay, 2012). On the other hand, many rep families were associated with rifamycin-resistant S. aureus. Although Rif resistance generally occurs due to chromosomal mutations (Zhou et al., 2012), it can also be plasmid-mediated (Arlet et al., 2001; Girlich et al., 2001). The mechanistic basis of RifR in our isolates and the role of rep types are worthy of future study.

The excessive use of antibiotics in humans and food animals is a driving force for spreading and maintaining virulent strains and their plasmids (Zurfluh et al., 2014; Wall et al., 2016). Thereby, knowledge of plasmid types carried by resistant strains is pivotal in controlling or impacting plasmid-mediated dissemination of antibiotic resistance. Nevertheless, our data must be interpreted with caution because the resistance profiles for S. aureus isolates were phenotypic; further analysis is required to confirm the association between certain rep families and the resistance of S. aureus in meat products.

The application of the rep typing scheme is a valuable tool for improving knowledge of plasmid dissemination and distribution in S. aureus inhabiting various environments, particularly the meat production system. Furthermore, links between rep families and specific genes would be helpful in future efforts designed to limit the dissemination of virulent strains in the meat pyramid. This study has confirmed the presence of plasmids with diverse sizes in multidrug-resistant S. aureus, which indicates that meat products might play a possible role in disseminating these strains and their plasmids to human consumers. Moreover, our results suggest that multiple sources and factors contribute to the spread and maintenance of plasmid-bearing S. aureus strains in the food chain.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

MF worked on the research design. LN and NR were responsible for the experimental procedures. HW and LN did the statistical analysis. LN and MF prepared the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support from the Research Office of The University of Tulsa (Tulsa, OK, United States) for granting Leena Neyaz a student research grant. The authors would also like to thank the Beta Beta Beta National Biological Honor Society for granting NR a student research grant. LN is grateful to the Saudi Government for granting her a Ph.D. fellowship to cover her study expenses in the U.S.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00223/full#supplementary-material

Detection of plasmids in S. aureus isolates by Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE). Red arrows in lanes 2, 5, 9, and 10 show large plasmids approximately 152 kb (lanes 2, 5) and 120 kb (lanes 9, 10). Yellow arrows indicate plasmids approximately 70 kb (lane 7) and 65 kb (lane 11). Small plasmids approximately 20 kb are shown in lanes 2, 3, 5, 9, and 10 (blue arrows). Lane 9 contains the Salmonella serovar Braenderup H9812 marker.

rep primers and multiplexes used for PCR.

References

- Aarestrup F. M., Wegener H. C., Collignon P. (2008). Resistance in bacteria of the food chain: epidemiology and control strategies. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 6 733–750. 10.1586/14787210.6.5.733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdalrahman L. S., Fakhr M. K. (2015). Incidence, antimicrobial susceptibility, and toxin genes possession screening of Staphylococcus aureus in retail chicken livers and gizzards. Foods 4 115–129. 10.3390/foods4020115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdalrahman L. S., Stanley A., Wells H., Fakhr M. K. (2015a). Isolation, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) Strains from Oklahoma Retail Poultry Meats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12 6148–6161. 10.3390/ijerph120606148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdalrahman L. S., Wells H., Fakhr M. K. (2015b). Staphylococcus aureus is more prevalent in retail beef livers than in pork and other beef cuts. Pathogens 4 182–198. 10.3390/pathogens4020182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argudín M. A., Mendoza M. C., Rodicio M. R. (2010). Food poisoning and Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins. Toxins 2 1751–1773. 10.3390/toxins2071751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlet G., Nadjar D., Herrmann J. L., Donay J. L., Lagrange P. H., Philippon A. (2001). Plasmid-mediated rifampin resistance encoded by an arr-2-like gene cassette in Klebsiella pneumoniae producing an ACC-1 class C beta-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45 2971–2972. 10.1128/aac.45.10.2971-2972.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines S. L., Jensen S. O., Firth N., da Silva A., Seemann T., Carter G. P., et al. (2019). Remodeling of pSK1 family plasmids and enhanced chlorhexidine tolerance in a dominant hospital lineage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63:e002356-18. 10.1128/AAC.02356-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski M., Piwowarczyk R., Madry A., Zagorski-Przybylo R., Hydzik M., Wladyka B. (2019). Prevalence of antibiotic and heavy metal resistance determinants and virulence-related genetic elements in plasmids of Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 10:805. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caddick J. M., Hilton A. C., Rollason J., Lambert P. A., Worthington T., Elliott T. S. J. (2005). Molecular analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus reveals an absence of plasmid DNA in multidrug-resistant isolates. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 44 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A. (2013). Plasmids and the spread of resistance. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303 298–304. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao L., Qiyu B., Fuping S., Ming S., Dafang H., Guiming L., et al. (2007). Complete nucleotide sequence of pBMB67, a 67-kb plasmid from Bacillus thuringiensis strain YBT-1520. Plasmid 57 44–54. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2006.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clewell D. B., An F. Y., White B. A., Gawron-Burke C. (1985). Streptococcus faecalis sex pheromone (cAM373) also produced by Staphylococcus aureus and identification of a conjugative transposon (Tn918). J. Bacteriol. 162 1212–1220. 10.1128/jb.162.3.1212-1220.1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI, (2019). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 29th Edn, Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Coimbra-E-Souza V., Rossi C. C., Jesus-de Freitas L. J., Brito M. A. V. P., Laport M. S., Giambiagi-deMarval M. (2019). Short communication: diversity of species and transmission of antimicrobial resistance among Staphylococcus spp. isolated from goat milk. J. Dairy Sci. 102 5518–5524. 10.3168/jds.2018-15723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeo F. R., Chambers H. F. (2009). Reemergence of antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the genomics era. J. Clin. Invest. 119 2464–2474. 10.1172/JCI38226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz S. A., Epplin E. K., Garbutt J., Storch G. A. (2009). Skin infection in children colonized with community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. 59 394–401. 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girlich D., Poirel L., Leelaporn A., Karim A., Tribuddharat C., Fennewald M., et al. (2001). Molecular epidemiology of the integron-located VEB-1 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in nosocomial enterobacterial isolates in Bangkok, Thailand. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39 175–182. 10.1128/jcm.39.1.175-182.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryczan T. J., Contente S., Dubnau D. (1978). Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus plasmids introduced by transformation into Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 134 318–329. 10.1128/jb.134.1.318-329.1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez D., Delgado S., Vázquez-Sánchez D., Martínez B., Cabo M. L., Rodríguez A., et al. (2012). Incidence of Staphylococcus aureus and analysis of associated bacterial communities on food industry surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 8547–8554. 10.1128/AEM.02045-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaber J., Penadés J. R., Ingmer H. (2017). Transfer of antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 25 893–905. 10.1016/j.tim.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. (1979). A simple and sequential rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Statist. 6 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Im M. C., Seo K. W., Bae D. H., Lee Y. J. (2016). Bacterial quality and prevalence of foodborne pathogens in edible offal from slaughterhouses in Korea. J. Food Prot. 79 163–168. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-15-251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C. R., Davis J. A., Barrett J. B. (2013). Prevalence and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from retail meat and humans in Georgia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51 1199–1207. 10.1128/JCM.03166-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L. B., Garcia-Migura L., Valenzuela A. J. S., Løhr M., Hasman H., Aarestrup F. M. (2010). A classification system for plasmids from enterococci and other Gram-positive bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 80 25–43. 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen S. O., Lyon B. R. (2009). Genetics of antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Future Microbiol. 4 565–582. 10.2217/fmb.09.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadariya J., Smith T. C., Thapaliya D. (2014). Staphylococcus aureus and staphylococcal food-borne disease: an ongoing challenge in public health. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014:827965. 10.1155/2014/827965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadlec K., Schwarz S. (2010). Identification of a plasmid-borne resistance gene cluster comprising the resistance genes erm(T), dfrK, and tet(L) in a porcine methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54 915–918. 10.1128/AAC.01091-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluytmans J., van Leeuwen W., Goessens W., Hollis R., Messer S., Herwaldt L., et al. (1995). Food-initiated outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus analyzed by pheno- and genotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33 1121–1128. 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1121-1128.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftie-Eaton W., Yano H., Burleigh S., Simmons R. S., Hughes J. M., Rogers L. M., et al. (2016). Evolutionary paths that expand plasmid host-range: implications for spread of antibiotic resistance. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33 885–897. 10.1093/molbev/msv339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano C., García-Migura L., Aspiroz C., Zarazaga M., Torres C., Aarestrup F. M. (2012). Expansion of a plasmid classification system for Gram-positive bacteria and determination of the diversity of plasmids in Staphylococcus aureus strains of human, animal, and food origins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 5948–5955. 10.1128/AEM.00870-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malachowa N., DeLeo F. R. (2010). Mobile genetic elements of Staphylococcus aureus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67 3057–3071. 10.1007/s00018-010-0389-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marasini D., Fakhr M. K. (2014). Exploring PFGE for detecting large plasmids in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from various retail meats. Pathogens 3 833–844. 10.3390/pathogens3040833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmur J. (1961). A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from micro-organisms. J. Mol. Biol. 3 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy A. J., Lindsay J. A. (2012). The distribution of plasmids that carry virulence and resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus is lineage associated. BMC Microbiol. 12:104. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougal L. K., Steward C. D., Killgore G. E., Chaitram J. M., McAllister S. K., Tenover F. C. (2003). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: establishing a national database. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 5113–5120. 10.1128/jcm.41.11.5113-5120.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk I. R., Foster T. J. (2012). Genetic manipulation of Staphylococci-breaking through the barrier. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2:49. 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noormohamed A., Fakhr M. K. (2012). Incidence and antimicrobial resistance profiling of Campylobacter in retail chicken livers and gizzards. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 9 617–624. 10.1089/fpd.2011.1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick R. P. (1987). Plasmid incompatibility. Microbiol. Rev. 51 381–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien A. M., Hanson B. M., Farina S. A., Wu J. Y., Simmering J. E., Wardyn S. E. (2012). MRSA in conventional and alternative retail pork products. PLoS One 7:30092. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogston A. (1882). Micrococcus poisoning. J. Anat. Physiol. 16 526–567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlek A., Phan H., Sheppard A. E., Doumith M., Ellington M., Peto T., et al. (2017). Ordering the mob: insights into replicon and MOB typing schemes from analysis of a curated dataset of publicly available plasmids. Plasmid 91 42–52. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts G. A., Houston P. J., White J. H., Chen K., Stephanou A. S., Cooper L. P., et al. (2013). Impact of target site distribution for Type I restriction enzymes on the evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) populations. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 7472–7484. 10.1093/nar/gkt535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouger A., Tresse O., Zagorec M. (2017). Bacterial contaminants of poultry meat: sources, species, and dynamics. Microorganisms 5:50. 10.3390/microorganisms5030050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Russell D. W. (2001). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd Edn, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E., Hoekstra R. M., Angulo F. J., Tauxe R. V., Widdowson M.-A., Roy S. L., et al. (2011). Foodborne illness acquired in the United States–major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17 7–15. 10.3201/eid1701.P11101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahkarami F., Rashki A., Rashki Ghalehnoo Z. (2014). Microbial susceptibility and plasmid profiles of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 7:e16984. 10.5812/jjm.16984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer J. E. S., Wireman J., Hostetler J., Forberger H., Borman J., Gill J., et al. (2011). Major families of multiresistant plasmids from geographically and epidemiologically diverse staphylococci. G3 1 581–591. 10.1534/g3.111.000760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani M., Sanchez Z. K., Kimbara K. (2015). Genomics of microbial plasmids: classification and identification based on replication and transfer systems and host taxonomy. Front. Microbiol. 6:242. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. C. (2015). Livestock-associated Staphylococcus aureus: the United States experience. PLoS Pathog. 11:e1004564. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal R. R., Rohlf R. J. (1995). Biometry: The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research, 3rd Edn, New York, NY: W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron D. E., Lindsay J. A. (2006). Sau1: a novel lineage-specific type I restriction-modification system that blocks horizontal gene transfer into Staphylococcus aureus and between S. aureus isolates of different lineages. J. Bacteriol. 188 5578–5585. 10.1128/jb.00418-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall B. A., Mateus A., Marshall L., Pfeiffer D. U., Lubroth J., Ormel H. J., et al. (2016). Drivers, Dynamics and Epidemiology of Antimicrobial Resistance in Animal Production. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Waters A. E., Contente-Cuomo T., Buchhagen J., Liu C. M., Watson L., Pearce K., et al. (2011). Multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in US Meat and poultry. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52 1227–1230. 10.1093/cid/cir181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano H., Wegrzyn K., Loftie-Eaton W., Johnson J., Deckert G. E., Rogers L. M., et al. (2016). Evolved plasmid-host interactions reduce plasmid interference cost. Mol. Microbiol. 101 743–756. 10.1111/mmi.13407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Shan W., Ma X., Chang W., Zhou X., Lu H., et al. (2012). Molecular characterization of rifampicin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in a Chinese teaching hospital from Anhui, China. BMC Microbiol. 12:240. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Murray P. R., Huskins W. C., Jernigan J. A., McDonald L. C., Clark N. C., et al. (2010). Dissemination of an Enterococcus Inc18-Like vanA plasmid associated with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54 4314–4320. 10.1128/AAC.00185-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurfluh K., Jakobi G., Stephan R., Hächler H., Nüesch-Inderbinen M. (2014). Replicon typing of plasmids carrying bla CTX-M-1 in Enterobacteriaceae of animal, environmental and human origin. Front. Microbiol. 5:555. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detection of plasmids in S. aureus isolates by Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE). Red arrows in lanes 2, 5, 9, and 10 show large plasmids approximately 152 kb (lanes 2, 5) and 120 kb (lanes 9, 10). Yellow arrows indicate plasmids approximately 70 kb (lane 7) and 65 kb (lane 11). Small plasmids approximately 20 kb are shown in lanes 2, 3, 5, 9, and 10 (blue arrows). Lane 9 contains the Salmonella serovar Braenderup H9812 marker.

rep primers and multiplexes used for PCR.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.