Abstract

Introduction

Studies on the determinants of contraceptive use often consider distance to the nearest health facility offering contraception as a key explanatory variable. Women, however, may not seek contraception from the nearest facility, rather opting for a more distant facility with better quality services or to ensure greater privacy and anonymity.

Methods

The dataset used include the name of facility where each women obtained contraception, measures of facility quality, and the distance between each woman’s home and 39 potential facilities she might visit. We use a conditional-multinomial logit model to estimate the determinants of her facility choice to visit and how women tradeoff travelling longer distances to use higher quality facilities.

Results

Only 33% of woman who received contraception from a health facility used their nearest facility. While the nearest facility was 1.2 km away, the average distance to facility used was 2.9 km, indicating women are willing to travel significantly longer distances for higher quality. Women prefer facilities that specialise in providing contraception, provide a large range of methods, do not suffer from stock outs and do not charge fees. Furthermore, on average, women are willing to travel an additional 2 km for a facility that offers more family planning methods, 4.7 km for a facility without one additional health service, 9 km for a facility without fees for contraception and 11 km for a facility not experiencing stock out of an additional contraception.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that quality of services provided is an important driver of facility choice in addition to distance to facility.

Keywords: geographic information systems, health systems, cross-sectional survey

Key questions.

What is already known?

Proximity to facility has been shown to influence a wide range of healthcare utilisation and health outcome measures.

What are the new findings?

Few women who received contraception from a health facility used their nearest facility.

Women prefer facilities that offer more family planning methods, do not charge a fee for family services, have fewer stock-outs and offer fewer health services.

What do the new findings imply?

Women are willing to travel significantly longer distances for higher quality health facilities.

Emphasis should shift from expanding the number of health facilities to improve the quality of services provided.

Introduction

Uptake of family planning services remains low in sub-Saharan Africa, placing millions of women at risk of mistimed and unintended pregnancies, which are, in turn, associated with increased risk of unsafe abortion and poor infant and maternal health outcomes.1–3 In Tanzania, contraceptive prevalence rates are relatively low; only 27% of married and sexually active women ages 15–49 years were using a modern method of family planning in 2016, while 17% of women reported a desire to space or stop childbearing but were not using any method of family planning.4

Easily accessible and high-quality family planning facilities are important for an adequate provision of family planning services, particularly to sexually active women who are minors, unmarried and not working, but have high unmet need.5 All family planning commodities are free in public health facilities in Tanzania.6 In addition, condoms are available to purchase at pharmacies, retails shops, drugstores and guesthouses. Oral contraception pills are also available outside health facilities and can be purchased at pharmacies and drug stores with a doctor’s prescription required for new users only. Emergency contraceptive pills can be bought without a prescription. All other methods of contraception, including injectable, implants and intrauterine devices (IUDs), must be provided by a trained health provider in a health facility.

Facility choice for any health service is influenced by a complex set of facility and patient characteristics, such as hours, fees, geographical access, facility reputation and quality, and patient socioeconomic status. Proximity to facility has been shown to influence a wide range of healthcare utilisation and health outcome measures.7–9 However, women may not necessarily seek health services from the nearest facility but rather, they might seek care from facilities with better quality even if these are located farther away.10 There is increasing evidence to support the notion that high-quality family planning services increase contraceptive use. Tumilson et al (2015) found quality measures capturing information given, and client-provider relations, to be significant predictors of current contraceptive use in Kenya.11 There is also evidence that quality of care at initiation of contraceptive use is positively associated with continuation of use.12

The idea that the emphasis on health provision in low-income countries should shift from access to services, to improving the quality of services, is becoming increasingly common.13 Previous studies that investigate the effect of health facility quality and distance on facility choice geographically link individual and facility-level data from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), to determine the distance to health facility.14 However, the DHS displaces geographic positioning system (GPS) coordinates of participants to maintain participant anonymity, creating ‘noise’.15 This noise can seriously bias the estimates of the effect of distance on service utilisation.16 17 In addition, DHS surveys only report the type of facility that a woman reports visiting, such as hospital, health centre or dispensary, rather than the actual name of facility, and studies often assume clients visit the nearest facility of the type they report.14 18 19

Our study uses a new dataset in which we collected precise GPS coordinates of sampled women, as well as the name of the facility each woman choose to visit for her most recent family planning services. We also conducted a census of facilities that provide family planning services in the study area and created quality indicators through a facility questionnaire. We aim to estimate which indicators of quality are important for womens’ choice of where to take up family planning; understanding this may be important for designing policies to increase uptake. We find that women are willing to travel farther to use a healthcare facility with better quality of family planning services, and we use this to estimate the trade-off women are willing to make between distance and service quality. This detailed information allows us to address the challenging question of the relationship between quality and distance to health facilities, and how women choose a facility for obtaining family planning services.

Methods

Data and sample

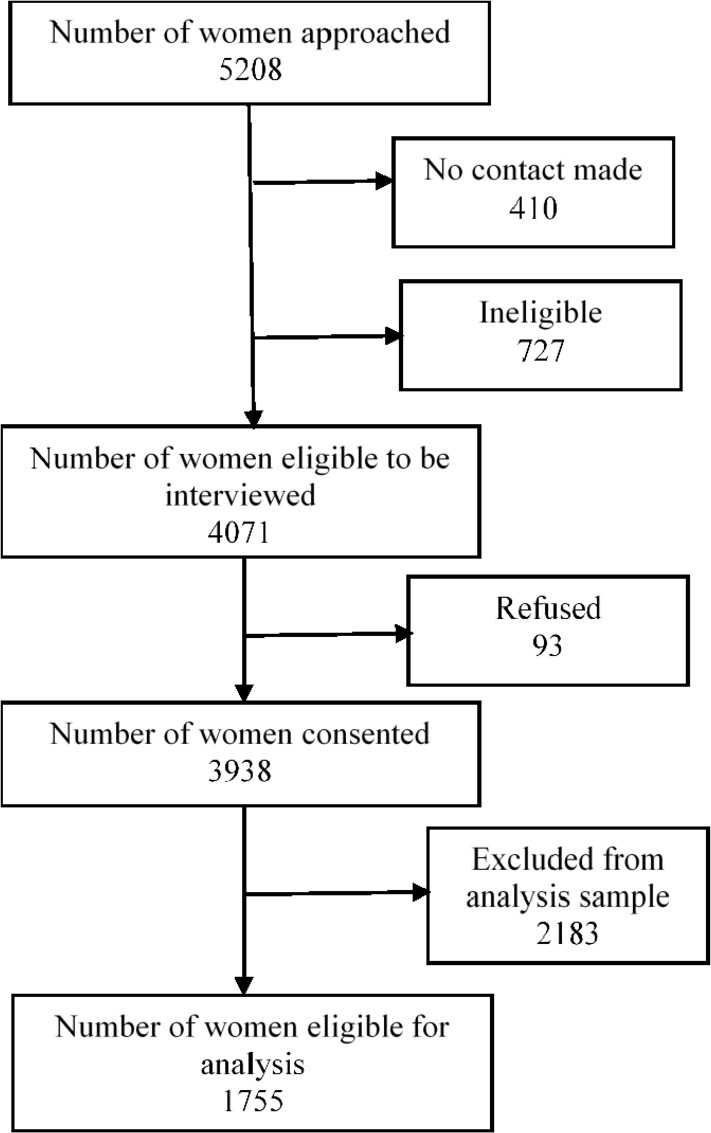

Data for this study were collected between December 2017 and June 2018 in the urban Arusha region of Tanzania. Arusha is located in the north-eastern region of Tanzania and the study area covered three wards in Arusha district and two wards in Meru district. Wards in Arusha were part of an impact evaluation of a reproductive health programme occurring in those wards and the wards in Meru were selected as a control site for the evaluation. The study area used administrative boundaries of all streets and villages in each ward as determined by the reproductive health programme implementers. This study used two primary data sources. The first was a comprehensive reproductive health survey conducted among a representative sample of women living within the study area. This survey was conducted among women 16- to 44-years old who were usual residents, could speak English or Swahili and were not mentally incapacitated. A three-stage random sampling procedure was used to select participants. The first stage involved randomly selecting 200 clusters in the study sites. Each cluster contained an average of 60 households. Within each cluster, a random sample of 26 households with eligible women were selected in the second stage of sampling. If there was more than one eligible woman in each household, a third stage involved randomly selecting one woman from each household. Sampled women were informed of the nature of the study and asked for consent to participate. The survey was adapted from the DHS Questionnaire for Tanzania.4 In particular, participants were asked if they had ever used or were currently using any method of family planning. Going further than the DHS, those who reported previous or current family planning use were then asked the name of the place and the type of facility they received their last or current method from. Only women who had ever used a method of contraception and received their last method from a health facility in the surrounding area were included in our analysis sample (n=1755) as seen in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sample selection diagram.

In addition to the women survey, a facility survey of health facilities that provide family planning services and products in or close to the study area was conducted (n=39). All facilities in the study area were identified with the help of the district family planning coordinators for Arusha and Meru. We also included all facilities outside but close to the study area if at least five women reported visiting the location. The facility survey measured variables that reflect service quality through direct observation and employee interviews. Surveys were conducted in hospitals, health centres and dispensaries and completed by facility administrators who were familiar with the facility activities. Our facility survey did not cover pharmacies or retail stores which are a potential source of some family planning methods.

Measures

The two datasets were combined to construct the primary outcome variable facility choice. To create this variable, each woman was assigned 39 possible choices. Facility choice is a binary variable that captures the health facility each woman chose to get her last or current family planning method. That is, she could choose to obtain family planning from one of the 39 facilities included in our facility survey (choices 1–39). Each possible woman choice is a data point in our analysis giving us an analysis set of 68 445 observations, that is, 39 choices × 1755 women in our sample. The outcome variable takes the value zero if a woman did not make that choice and a value 1 if she did. Hence, each women will have 38 values of zero and one value of 1. Women who did not use family planning, or received their contraceptives from pharmacies, retails stores or a drug store were excluded from these analysis. These establishments are ubiquitous, every women has access to one nearby and they offer only condoms and oral contraceptive pills.

The explanatory variables for an observation are the characteristics of each woman and the facility characteristics for the facility in the woman-facility pairing.

Facility characteristics

Based on the GPS coordinates of the woman’s home and the facility, we constructed a distance variable (in km) capturing the straight-line distance of each woman from home to every facility using Stata. On average, the accuracy of the GPS measure was 15 m as recorded by the data collection device. Several variables were created to capture the quality of family planning services offered at each facility.

Type of facility: hospital, health centre and dispensary.

A count for the number of family planning methods each facility provides. The family planning methods included were as follows: combined oral contraceptive pills, progestin-only contraceptive pills, combined injectable contraceptives, progestin-only injectable contraceptives, male condoms, female condoms, IUD, implant, emergency contraceptive pills, cycle beads for standard days method/calendar method, tubal ligation (female sterilisation), vasectomy (male sterilisation) and other methods (eg, spermicide or diaphragm). The range of possible family planning count ranged from 0 to 13.

A score for the range of other health services available at each facility in addition to family planning. These services were as follows: vaccination, antenatal care services, normal delivery and/or newborn care, caesarean section, surgical abortion, medical abortion and Comprehensive Post Abortive Care Services. The range of services variable score ranged from 0 to 8.

The availability of follow-up appointments for family planning services (yes or no). Facilities were asked if family planning clients were given appointments for follow-up consultation/ examination.

Stock out of family planning commodities. Facilities were asked if they had ever ran out of stock of each family planning commodity in the past 3 months. Each facility was given a score based on the number of contraceptive methods that had experienced such stock out. In all, 13 family planning methods were considered. The range of stock out score ranged from 0 to 4 for all facilities in the facility survey meaning that at least one facility experienced a stock out of four family planning methods within the last 3 months.

Fees charged for family planning services (yes or no). Facilities were asked if they have routine user-fees or charges for family planning client services.

Women characteristics

Variables that captured characteristics for each women were also added in the model.

Education was categorised as a binary variable with women with no education or primary education (0) and women with higher education (1).

Marital status was categorised as a binary variable with women currently married or living with a partner (1) and women formerly married or living with a partner or never married or lived with partner (0).

Age was included as a continuous variable.

A wealth index variable was first created as a composite, asset-based measure from a series of questions and then standardised to quintiles. In this analysis, wealth was categorised as a binary variable with women who are in the highest two categories, rich and richest (1) and women in the last three index categories poor, poorest or middle wealth index (0).

Analysis

We employed the alternative specific conditional logit model, asclogit command in Stata, which has previously been used to predict choice of facility.20 This model assigns a woman a utility for each choice and is based on the assumption that she chooses the facility that gives her the highest utility. The utility for woman i from choosing facility j is given as follows:

There are M variables that vary across woman and facility that affect her utility. These may include measures of facility quality and distance to facility. Note that these variables may only vary across facilities, such as indicators of quality, or may vary across facilities and women, for example distance from the woman’s home to that facility. Each facility-related variable m has a utility weight . In addition to these facility-related variables, there are P woman level variables , namely her age, marital status and education level that affect the utility of each facility. Note that the coefficients on the woman level variables vary with facility. Each woman level variable, , therefore affects the utility of going to each facility j in a different way given by the parameter . This allows each facility to be attractive to different subsets of women. There is an error term given by a woman cross facility random utility term with a Gumbel extreme value distribution. The parameters estimates of the model are constructed so as to maximise the probability of the facility choices women are observed to make. We are particularly interested in the parameters that describe how such measures as facility quality, and distance to the facility, affect utility and the choice of facility. Finally, to control for the multi-stage sample design, we clustered our standard errors at the sample cluster level to allow for correlation in the error structure among women in the same cluster.

The estimated coefficients are not directly interpretable. A positive implies that the variable increases utility, and the likelihood a woman chooses the facility, while a negative value implies lower utility, and less likelihood of choosing that facility. However, the scale of these coefficients depends on an arbitrary normalisation—if we multiply all the coefficients the utility function, and the error term, by an arbitrary positive constant the relative ranking of choices remains the same and the likelihood of each choice is unchanged. However, we can construct a more meaningful measure of the effect of facility quality on choice21; based on how the probability that woman i chooses health facility j, given by changes when the variable increases by one unit. The effect of changing the characteristic of facility j, on the probability woman i chooses this facility, , is given by , where is the estimate coefficient on in the conditional logit model. If a facility increases a quality measure that improves utility (a measure with a positive ), women are more likely to choose it. The cross effect of changing, the value of variable m in facility k, on , the probability the woman chooses facility j for , is given by . As facility k increases a quality indicator the probability that a woman visits an alternative facility j declines. Finally, we can construct the distance equivalent of a quality measure , the amount that distance would have to increase to offset the increased attractiveness of a facility when it increases a quality measure. This is given by the implicit function , where is the distance from the home of woman i to facility j. That is, if we increase the quality measure by one unit and the distance to facility by kilometres the utility of woman i, and her likelihood of choosing facility j, remains the same. The extra distance a woman is willing to travel to a facility for additional unit of quality is therefore . While the absolute value of the coefficients in the utility model is arbitrary, their relative values have an intuitive interpretation, and we can derive the willingness to pay for quality in terms of distance travelled.

Ethical approval was received from the National Institute of Medical Research (NIMR), the Kilimanjaro Christ Medical College Institutional Review Board and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Institutional Review Board to conduct the health facility and women’s survey.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in any way with this study.

Results

Women’s characteristics

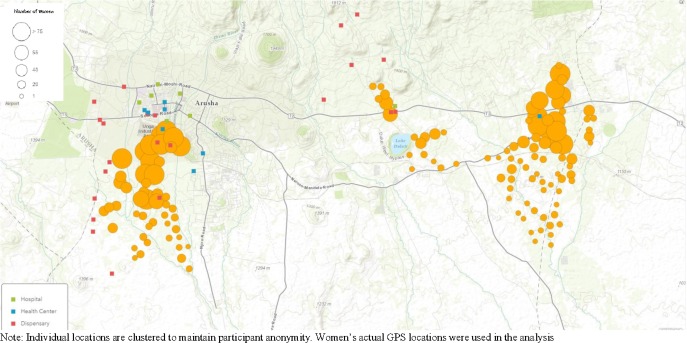

Table 1 shows the characteristics of women in our study sample. The average age of women was 31 years. Sixty-nine per cent of women had no education or only had a primary school education, 83% of women was currently married and a little over half of women lived in the top two wealth index groups. By examining the distribution of women in our sample by the distance to the health facility where they received their last family planning method, we see that only 33% of women who had ever used a method of family planning and received that method from the health facility went to the health facility nearest to them (table 1). Furthermore, we see that the average distance to the chosen health facility was 2.9 km even though the average distance to the nearest facility was around 1.2 indicating women are willing to travel significantly longer distances for higher quality. The same pattern is observed when the sample is stratified by district. Figure 2 is a map which shows the distribution of women and health facilities in the study area. It also shows the spatial distribution of the different types of health facilities available in the study area. Table 2 shows the types of contraceptive methods used by women included in our analysis sample and those used by women excluded from our analysis sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women in analysis sample

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

| Women who visited the nearest health facility by age | 31 (years) | 6.6 | 16 | 44 |

| 16–19 | 0.26 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 20–24 | 0.36 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 25–29 | 0.36 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 30–34 | 0.32 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 35–39 | 0.29 | – | 0 | 1 |

| 40–44 | 0.29 | – | 0 | 1 |

| Women with no education or primary school education | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 |

| Women who visited the nearest health facility with no education or primary school education | 0.32 | – | 0 | 1 |

| Women who visited the nearest health facility with more than primary school education | 0.34 | – | 0 | 1 |

| Currently married | 0.83 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 |

| Women who visited the nearest health facility and are currently married | 0.33 | – | 0 | 1 |

| Women who visited the nearest health facility and are not currently married | 0.33 | – | 0 | 1 |

| Wealthiest women | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Women who visited the nearest health facility and are in the poorest wealth groups | 0.29 | – | 0 | 1 |

| Women who visited the nearest health facility and are in the richest wealth groups | 0.37 | – | 0 | 1 |

| Women who visited the nearest health facility | 0.3 | – | 0 | 1 |

| Distance to the facility chosen (km) | 2.9 | 3.4 | 0.05 | 20.8 |

| Distance of the nearest facility to each woman (km) | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.04 | 6.2 |

| Distance of the nearest hospital to each woman (km) | 4.7 | 3.0 | 0.23 | 9.8 |

| Distance of the nearest health centre to each woman (km) | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.05 | 8.0 |

| Distance of the nearest dispensary to each woman (km) | 3.9 | 3.4 | 0.04 | 9.7 |

| Women living in Arusha | ||||

| Woman visited the nearest health facility | 0.07 | – | 0 | 1 |

| Distance to the facility chosen (km) | 2.5 | 1.9 | 0.05 | 19.7 |

| Distance of the nearest facility to each woman (km) | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 3.4 |

| Women living in Meru | ||||

| Woman visited the nearest health facility | 0.5 | – | 0 | 1 |

| Distance to the facility chosen (km) | 3.2 | 4.2 | 0.06 | 20.8 |

| Distance of the nearest facility to each woman (km) | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.04 | 6.2 |

Figure 2.

The distribution of women and health facilities in the study area.

Table 2.

Contraceptive methods used by women in analysis sample and women who were excluded

| Women in analysis sample | Women excluded from analysis sample | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Never used a method | – | – | 0.31 | 0.46 |

| Female sterilisation | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| Male sterilisation | – | – | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| IUD | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| Injectables | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.47 |

| Implants | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.21 |

| Pills | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.26 |

| Condoms | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.27 |

| Female condoms | – | – | 0.001 | 0.03 |

| Emergency contraception | – | – | 0.004 | 0.06 |

| Lactational amenorrhoea method | – | – | 0.003 | 0.06 |

| Standard days/calendar/rhythm/withdrawal | – | – | 0.11 | 0.21 |

| Traditional method | – | – | 0.003 | 0.02 |

IUD, intrauterine device.

Facility characteristics

The average score for family planning commodities offered in health facilities surveyed was 6.5 (range 0–10) while the average score for health services offered was 5.1 (range 1–8) (table 3). Health centres offered more commodities on average; however, hospitals offered more health services. In all, 37 facilities offered follow-up services for family planning services while seven facilities had fees for family planning services. Overall, most facilities surveyed offered follow-up consultation for family planning services. Finally, the table shows that stock outs were more prevalent in health centres and dispensaries than in hospitals.

Table 3.

Distribution of quality indicators by facility type

| Hospital | Health centre | Dispensary | Total | |

| Frequency | 6 | 10 | 23 | 39 |

| Number of family planning methods provided | ||||

| Mean | 7 | 7.9 | 6.1 | 6.5 |

| SD | 3.37 | 2.95 | 1.74 | 2.67 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Max | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Number of health services provided | ||||

| Mean | 7.2 | 7 | 3.7 | 5.1 |

| SD | 0.37 | 1 | 1.2 | 2.25 |

| Min | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| Max | 8 | 8 | 6 | 8 |

| Follow-up for family planning services | ||||

| Yes | 5 | 9 | 13 | 37 |

| No | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Fees for family planning services | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| No | 5 | 7 | 20 | 32 |

| Stock out of family planning commodities | ||||

| Mean | 0.17 | 0.6 | 0.61 | 0.52 |

| SD | 0.37 | 1.2 | 0.87 | 0.91 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

Predictors of facility choice

We estimate a conditional logit model of facility choice. We report our results in table 4 where the coefficients can be interpreted as the effect of each facility characteristic of women’s utility. We include distance to the facility in kilometres, and a dummy for being the facility closest to the women as possible factors influence utility and choice. Not surprisingly, distance to facility was negatively associated with facility choice meaning the farther away a health facility was from a woman’s home, the less likely it was to have been selected. Being the closest facility did mean a facility was more likely to be chosen; if two facilities are approximately equidistant a women is more likely to choose the closest. Our results also show that health centres were more likely to be chosen over hospitals, while dispensaries were less likely to be chosen over hospitals. Four quality measures were significantly associated with facility choice. Health facilities that provided more family planning methods increased the chances of that facility being chosen. On the other hand, facilities that offered other health services, had fees for family services and had a stock out were less likely to have been selected.

Table 4.

Determinants of utility: alternative specific logistic regression

| Outcome: facility choice | T statistics | |

| Distance to facility (km) | −0.38*** | −15.44 |

| Nearest facility to women | 0.52*** | 4.68 |

| Facility type (ref=hospital) | ||

| Health centre | 2.51*** | 4.28 |

| Dispensaries | −4.08*** | −3.93 |

| Range of family planning commodities available at facility | 0.75** | 3.13 |

| Range of other health services offered at facility | −1.79*** | −6.34 |

| Follow-up for family planning services offered at facility (ref=no) | 0.62 | 0.29 |

| Fees for family planning services at facility (ref=no) | −3.36*** | −3.18 |

| Stock out of family planning commodities | −4.26*** | −3.27 |

Output for coefficients of women-level characteristics (age, education, marital status and wealth) are not shown butwere included in the analysis.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Table 5 gives an example of the marginal effects of two health facilities here using the most frequented and median health facilities as examples. Results from table 5 were used to calculate the estimated extra distance a woman is willing to travel for a facility with better quality measures (table 6). We find that a woman is willing to travel 2 km for a facility that offer more family planning services, 4.6 km for a facility without one additional health service, 8.8 km for a facility without fees for family planning and 11 km for a facility not experiencing stock out of an additional family planning commodities.

Table 5.

Average marginal effect of the probability of choosing the largest facility J when regressor increases by one unit for median facility K at the average of other covariates

| Largest facility J | Median facility K | |

| Probability of choosing each facility | 0.112 | 0.069 |

| Distance to facility (km) | ||

| Marginal effect of increasing the distance to own facility by 1 km, reduces the probability of choosing that health facility (own effect) by | −0.038 | 0.003 |

| Marginal effect of increasing the distance to cross facility by 1 km, increases probability of choosing the other health facility (cross effect) by | 0.003 | −0.025 |

| Range of family planning commodities available at facility | ||

| Marginal effect of increasing the range of family planning by one method, increases the probability of choosing the health facility (own effect) by | −0.177 | −0.116 |

| Marginal effect of increasing the range of family planning by one method, decreases the probability of choosing the other health facility (cross effect) by | 0.0139 | 0.0139 |

| Fees for family planning services at facility | ||

| Marginal effect of having fees for family planning, decreases the probability of choosing the health facility (own effect) by | −0.332 | −0.217 |

| Marginal effect of having fees for family planning, increases the probability of choosing the other health facility (cross effect) by | 0.026 | 0.026 |

NB: largest facility is the facility with the most number of women receiving their contraceptive method.

Table 6.

Estimated extra distances (in km) women are willing to travel for an increased quality indicator, at the average values of other covariates

| Estimated extra distance (km) a woman is willing to travel for: | |

| Facility with more family planning methods | 2 |

| Facility with one less health service | 4.7 |

| Facility without fees for family planning | 8.6 |

| Facility not experiencing stock out of one additional family planning method | 11 |

Discussion

Not all women in our study received their last or current method of family planning from the closest facility, calling into question the assumption that women are using the closest facility when the actual facility chosen is not known. Existing studies often use the distance to the nearest health facility as a predictor; our study suggests it may not be a good predictor for health facility choice regarding family planning. This adds to evidence base that individuals, particularly those in urban environments such as our study area, frequently bypass their nearby health facility to obtain higher quality healthcare (Akin and Hutchinson, 1999; Leonard et al, 2003).

Our results also indicate that women have a preference for facilities that offer more methods of family planning, do not charge a fee for family services, have fewer stock-outs and offer fewer health services. The result that women prefer facilities offering fewer services suggests a preference for facilities that are more specialised in providing family planning. Our results imply that women are not only willing to bypass the closest facility but are also willing to travel fairly long distances, to receive family planning services from facilities they prefer. In particular, women have strong preferences for, and are willing to travel long distances to use, health facilities that do not experience stock-outs and who do not charge fees for service.

Women in our sample prefer to receive family planning services at health centres over hospitals but prefer hospitals over dispensaries. Dispensaries are smaller than hospitals and health centres and offer fewer services. To increase access to family planning geographical proximity should be considered. However, our findings suggest that for most women the closest health facility in the setting we study is already quite close, and the emphasis should shift from expanding the number of health facilities to improving the quality of services provided.

This study has a number of limitations. First, we did not have comparable measure of facility quality for the ‘other facilities’. These unobserved facilities largely consisted of pharmacies, drug stores and shops where pills and condoms are readily available without the need to see a clinician. Future extensions to this analysis could include a census of all places that offer and sell family planning products in the study area, including these small pharmacies and shops. Second, it is possible that unobserved quality characteristics such as client–provider interaction are correlated with characteristics that we observe. However clients’ perceptions are impacted by their expectations and prior experience hence may not be accurate in their assessment of quality. An extension of this study did include an exit patient survey that captured clients’ experiences with family planning providers after receiving a family planning product or service at each facility. However, these data were dropped due to lack of variation of responses. Another limitation worth noting is that women not currently using a method of contraception were not asked how long ago they received their last method. It is possible that at the time some women received their method of contraception, a nearby health facility was not available. Finally, our dataset captured the straight-line distance from women’s household to the nearest health facility. It is possible that women do not use the facility nearest to their primary residence but use one that is more convenient to another location such as their place of work, school or other location they frequent. In addition, straight-line distances do not account for road condition and transportation issues especially in an urban area like Arusha. To maintain anonymity of women’s locations, we were unable to combine our survey data with third-party sites with road network information for Arusha. Hence, the results observed here cannot be generalised to other regions in Tanzania without accounting for cost of transportation or road conditions.

This study used health facility data linked to women’s survey data to examine the association of indicators of facility quality and women’s choice of family planning facility. Our findings contribute to the literature on facility choice by having data on the name of the facility chosen, and removing the bias in parameter estimates due to masking of precise location information to protect subject confidentiality. There is little consensus in the literature on the most important quality indicators and how to measure them.22 23 One approach is to use an index of quality, however, we deliberately did not use that approach to have a clear interpretation of the importance of each indicator. As such, this study highlights four facility quality measures that women in this study area consider important and value when they choose a facility for family planning. However, our quality measures may be correlated with other quality-related factors that we do not observe, and the coefficients reflect the effect of broader notions of quality, not just the precise components we measure.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the Willows Impact Evaluation research team in Tanzania for their contributions to this research study and the women who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: BE and DC developed and conceptualised the study design. BE and RS conducted all analysis. RM, SM and BE conducted all data collection. DC and IS conceptualised the data collection procedures. DC, RS and BE contributed to writing of manuscript. All authors reviewed the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Harvard TH Chan School of Public Heath IRB (IRB17-1794); National Institute for Medical Research (NIMRlHQIR.8cNol. 1/1171); KILIMANJARO CHRISTIAN MEDICAL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE (2240).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are not available for sharing to maintain participant anonymity.

References

- 1. Cleland J, Conde-Agudelo A, Peterson H, et al. Contraception and health. The Lancet 2012;380:149–56. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60609-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alan Guttmacher Institute,, United Nations Population Fund . Adding it up: the costs and benefits of investing in family planning and maternal and newborn health [Internet], 2009. Available: http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/dsp01gb19f853p [Accessed 9 Dec 2018].

- 3. WHO Preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries [Internet]. WHO, 2011. Available: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/preventing_early_pregnancy/en/ [Accessed 19 Dec 2018].

- 4. Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC) [Tanzania Mainland], Ministry of Health (MoH) [Zanzibar], National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of the Chief Government Statistician (OCGS), ICF Tanzania demographic and health survey and malaria indicator survey (TDHS-MIS), 2016. Available: https://dhsprogram.com/what-we-do/survey/survey-display-485.cfm [Accessed 19 Dec 2018].

- 5. Michaels-Igbokwe C, Terris-Prestholt F, Lagarde M, et al. Young people's preferences for family planning service providers in rural Malawi: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One 2015;10:e0143287 10.1371/journal.pone.0143287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. United Republic of Tanzania MoHSW The National road map strategic plan to accelerate reduction of maternal, newborn and child deaths in Tanzania 2008–2015, 2008. Available: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The%20National%20Road%20Map%20Strategic%20Plan%20To%20Accelerate%20Reduction%20of%20Maternal%2C%20Newborn%20and%20Child%20Deaths%20in%20Tanzania%202008%E2%80%932015&publication_year=2008 [Accessed 25 Dec 2018].

- 7. Nemet GF, Bailey AJ. Distance and health care utilization among the rural elderly. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1197–208. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00365-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goodman DC, Fisher E, Stukel TA, et al. The distance to community medical care and the likelihood of hospitalization: is closer always better? Am J Public Health 1997;87:1144–50. 10.2105/AJPH.87.7.1144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arcury TA, Gesler WM, Preisser JS, et al. The effects of geography and spatial behavior on health care utilization among the residents of a rural region. Health Serv Res 2005;40:135–56. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00346.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Larson E, Mbaruku G, Mbatia R, et al. Can investment in quality drive use? A cluster-randomised controlled study in rural Tanzania. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:S9 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30138-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tumlinson K, Pence BW, Curtis SL, et al. Quality of care and contraceptive use in urban Kenya. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2015;41:69–79. 10.1363/4106915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. RamaRao S, Lacuesta M, Costello M, et al. The link between quality of care and contraceptive use. Int Fam Plan Perspect 2003;29:76–83. 10.2307/3181061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kruk ME, Pate M, Mullan Z. Introducing the Lancet global health Commission on high-quality health systems in the SDG era. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e480–1. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30101-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gabrysch S, Cousens S, Cox J, et al. The influence of distance and level of care on delivery place in rural Zambia: a study of linked national data in a geographic information system. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000394 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burgert CR, Colston J, Roy T, et al. Geographic displacement procedure and georeferenced data release policy for the demographic and health surveys 2013.

- 16. Arbia G, Espa G, Giuliani D. Measurement errors arising when using distances in microeconometric modelling and the individuals’ position is geo-masked for confidentiality. Econometrics 2015;3:709–18. 10.3390/econometrics3040709 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Elkies N, Fink G, Bärnighausen T. “Scrambling” geo-referenced data to protect privacy induces bias in distance estimation. Popul Environ 2015;37:83–98. 10.1007/s11111-014-0225-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kitui J, Lewis S, Davey G. Factors influencing place of delivery for women in Kenya: an analysis of the Kenya demographic and health survey, 2008/2009. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:40 10.1186/1471-2393-13-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lohela TJ, Campbell OMR, Gabrysch S. Distance to care, facility delivery and early neonatal mortality in Malawi and Zambia. PLoS One 2012;7:e52110 10.1371/journal.pone.0052110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Larson E, Vail D, Mbaruku GM, et al. Moving toward patient-centered care in Africa: a discrete choice experiment of preferences for delivery care among 3,003 Tanzanian women. PLoS One 2015;10:e0135621 10.1371/journal.pone.0135621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics using Stata, revised edition. StataCorp LP, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bessinger RE, Bertrand JT. Monitoring quality of care in family planning programs: a comparison of observations and client exit interviews. Int Fam Plan Perspect 2001;27:63–70. 10.2307/2673816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cuéllar C, Quijada C, Callahan S. The evolution of strategies and measurement methods to assess the quality of family planning services. Qual Meas Fam Plan Past 2016;3. [Google Scholar]