Abstract

This secondary analysis of National Survey on Drug Use and Health data examines recent national trends in cannabis use among older adults in the United States to determine whether cannabis use has continued to increase and to examine trends in use among subgroups of older adults.

With the legalization of cannabis in many states for medical and/or recreational purposes, there is increasing interest in using cannabis to treat a variety of long-term health conditions and symptoms common among older adults. The use of cannabis in the past year by adults 65 years and older in the United States increased sharply from 0.4% in 2006 and 2007 to 2.9% in 2015 and 2016.1,2 This study examines the most recent national trends in cannabis use to determine whether cannabis use has continued to increase among older adults and to further examine trends in use among subgroups of older adults.

Methods

We performed secondary analysis of adults 65 years and older from the most recent 4 cohorts (2015-2018) of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, a cross-sectional nationally representative survey of noninstitutionalized individuals in the United States.3 We estimated the prevalence of past-year cannabis use across cohorts and estimated prevalence stratified by each level of sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, household income, marital status, chronic disease, tobacco and alcohol use, mental health treatment, and all-cause emergency department use. Cannabis use was ascertained by asking about marijuana, hashish, pot, grass, and hash oil use either smoked or ingested.3 We calculated the absolute and relative change in prevalence between 2015 and 2018. Using logistic regression, we estimated whether there was a log-linear association between cannabis use and time, and interactions were examined to determine changes across subgroups. Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P value less than .05. We used sample weights (provided by National Survey on Drug Use and Health) to account for the complex survey design, selection probability, nonresponse, and population distribution. This secondary analysis was exempt from review by the New York University’s institutional review board. Analyses were conducted using Stata/SE version 13 (StataCorp).

Results

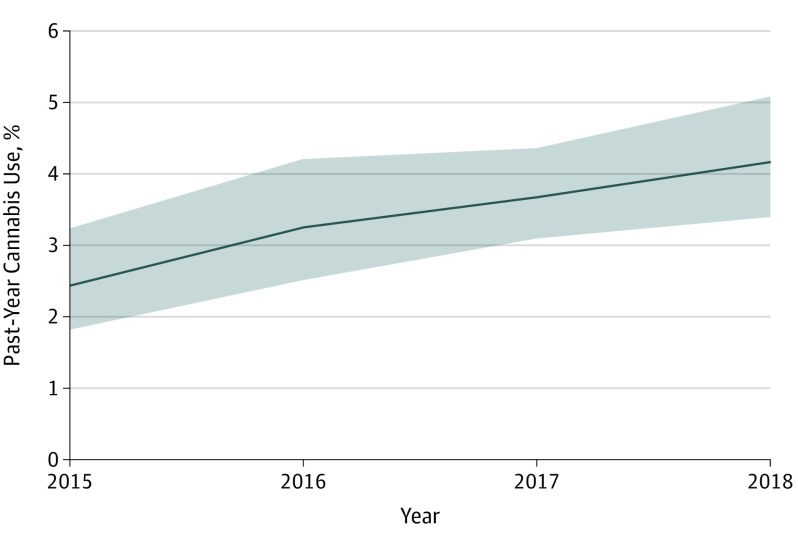

Of 14 896 respondents 65 years and older, 55.2% were men and 77.1% were white. The prevalence of past-year cannabis use among adults 65 years and older increased significantly from 2.4% to 4.2% (P = .001), a 75% relative increase (Figure). The Table presents prevalence trends stratified by participant characteristics. There were significant increases among women, individuals of white and nonwhite races/ethnicities, individuals with a college education, individuals with incomes of $20 000 to $49 000 and $75 000 or greater, and married individuals. In terms of chronic disease, among adults with diabetes, there was a 180% relative increase (1.0% [95% CI, 0.5-2.1] in 2015 vs 2.8% [95% CI, 1.7-4.7] in 2018; P = .02) in cannabis use. Individuals reporting 1 or less chronic diseases had a significant relative increase in cannabis use of 95.8% (2.4% [95% CI, 1.8-3.2] in 2015 vs 4.7% [95% CI, 3.6-6.2] in 2018; P < .001). Those who received mental health treatment also had a significant increase in cannabis use (2.8% [95% CI, 1.3-5.9] in 2015 vs 7.2% [95% CI, 4.8-10.5] in 2018; 157.1% relative increase; P = .02) as well as those reporting past-year alcohol use (2.9% [95% CI, 2.2-4.0] in 2015 vs 6.3% [95% CI, 5.0-8.0] in 2018; 117.2% relative increase; P < .001).

Figure. Trend in Prevalence of Past-Year Cannabis Use Among Adults 65 Years and Older in the United States, 2015 to 2018.

The shading indicates 95% CIs.

Table. Trends in Prevalence of Past-Year Cannabis Use by Sociodemographic, Chronic Disease, Health Care Use, and Substance Use Characteristics Among Adults 65 Years and Older in the United States, 2015-2018a.

| Characteristic | Weighted % (95% CI) | % Change From 2015 to 2018 | Linear Trend P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Absolute Change | Relative Change | ||

| Overall past-year cannabis use | 2.4 (1.8-3.2) | 3.3 (2.5-4.2) | 3.7 (3.1-4.4) | 4.2 (3.4-5.1) | 1.8 | 75.0 | .001 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 3.6 (2.4-5.3) | 5.1 (3.8-6.9) | 4.6 (3.5-5.9) | 5.7 (4.6-7.1) | 2.1 | 58.3 | .05 |

| Female | 1.5 (1.0-2.2) | 1.8 (1.1-2.7) | 3.0 (2.3-4.0) | 2.9 (2.1-4.1) | 1.4 | 93.3 | .01 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2.8 (2.1-3.8) | 3.1 (2.3-4.1) | 3.5 (2.9-4.3) | 4.0 (3.2-4.9) | 1.2 | 42.9 | .02 |

| All other races/ethnicitiesb | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) | 3.8 (2.4-6.2) | 4.2 (2.8-6.2) | 4.8 (3.0-7.9) | 3.7 | 336.4 | .01 |

| Education | |||||||

| High school or less | 2.3 (1.4-3.7) | 2.6 (1.7-3.9) | 2.1 (1.5-3.0) | 2.7 (1.9-3.8) | 0.4 | 17.4 | .71 |

| Some college | 2.1 (1.1-4.1) | 3.7 (2.5-5.3) | 5.0 (3.5-6.9) | 4.0 (2.9-5.5) | 1.9 | 90.5 | .02 |

| College or more | 2.9 (1.8-4.7) | 3.8 (2.6-5.6) | 4.7 (3.2-6.9) | 6.2 (4.3-8.8) | 3.3 | 113.8 | .01 |

| Total family income, $ | |||||||

| <20 000 | 3.7 (2.0-6.6) | 4.6 (2.7-7.6) | 4.8 (3.2-7.0) | 4.3 (2.8-6.5) | 0.6 | 16.2 | .67 |

| 20 000-49 999 | 1.3 (0.9-2.0) | 3.5 (2.4-5.1) | 3.3 (2.4-4.6) | 3.1 (2.1-4.6) | 1.8 | 138.5 | .02 |

| 50 000-74 999 | 3.6 (1.9-7.0) | 3.3 (2.0-5.3) | 1.7 (0.9-3.3) | 3.7 (2.4-5.8) | 0.1 | 2.8 | .75 |

| ≥75 000 | 2.4 (1.5-4.1) | 2.1 (1.1-3.8) | 4.8 (3.2-7.0) | 5.5 (3.7-8.0) | 3.1 | 129.2 | .003 |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 2.1 (1.4-3.2) | 2.3 (1.6-3.2) | 3.1 (2.3-4.1) | 4.2 (3.1-5.6) | 2.1 | 100.0 | .004 |

| Unmarried | 2.9 (2.0-4.2) | 4.7 (3.3-6.6) | 4.6 (3.6-6.0) | 4.2 (3.1-5.6) | 1.3 | 44.8 | .15 |

| Chronic disease | |||||||

| Heart disease | 2.2 (1.2-4.2) | 2.9 (1.7-4.8) | 2.5 (1.5-4.2) | 4.6 (3.4-6.1) | 2.4 | 109.1 | .06 |

| Diabetes | 1.0 (0.5-2.1) | 2.2 (1.4-3.7) | 2.1 (1.2-3.6) | 2.8 (1.7-4.7) | 1.8 | 180.0 | .02 |

| Hypertension | 2.1 (1.3-3.4) | 3.0 (2.0-4.4) | 3.3 (2.5-4.5) | 3.6 (2.4-5.4) | 1.5 | 71.4 | .08 |

| Cancer | 3.3 (1.6-6.6) | 3.2 (1.8-5.5) | 3.4 (2.1-5.5) | 4.4 (3.0-6.2) | 1.1 | 33.3 | .49 |

| Chronic diseasesc | |||||||

| ≥2 | 2.4 (1.4-4.2) | 3.0 (2.1-4.5) | 2.7 (1.8-4.0) | 3.1 (2.1-4.7) | 0.7 | 29.2 | .54 |

| <2 | 2.4 (1.8-3.2) | 3.4 (2.6-4.5) | 4.2 (3.5-5.0) | 4.7 (3.6-6.2) | 2.3 | 95.8 | <.001 |

| Mental health treatment in the past year | 2.8 (1.3-5.9) | 8.7 (5.9-12.6) | 9.0 (5.6-14.1) | 7.2 (4.8-10.5) | 4.4 | 157.1 | .02 |

| Substance use in the past year | |||||||

| Tobacco use | 5.9 (3.8-9.1) | 10.3 (7.2-14.6) | 9.0 (6.1-13.1) | 10.2 (7.6-13.8) | 4.3 | 72.9 | .13 |

| Alcohol use | 2.9 (2.2-4.0) | 4.8 (3.7-6.1) | 5.7 (4.7-7.0) | 6.3 (5.0-8.0) | 3.4 | 117.2 | <.001 |

| All-cause emergency department use in the past year | 2.8 (1.6-4.7) | 2.5 (1.5-4.3) | 4.0 (2.9-5.5) | 4.7 (3.4-6.4) | 1.9 | 67.9 | .05 |

Data from the 2015-2018 US National Survey on Drug Use and Health among respondents 65 years and older (n = 14 896).

Owing to response sizes less than 10 in 2015 for certain races/ethnicities, black, Hispanic, and other nonwhite races were combined into 1 category.

Chronic conditions include asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, diabetes, heart disease, hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, hypertension, cancer, and kidney disease.

Discussion

The use of cannabis continues to increase among older adults nationally. We determined that a number of key subgroups experienced marked increases in cannabis use, including women, racial/ethnic minorities, those with higher family incomes, and those with mental health problems. While we also found an increase in cannabis use among older people with diabetes, in general, it appears that the increase in cannabis use is driven largely by those who do not have multiple chronic medical conditions.

We also detected an increase in cannabis use among older adults who use alcohol. The risk associated with co-use is higher than the risk of using either alone, and a 2019 study of trends in alcohol and cannabis co-use following legalization in Washington state4 found significant increases in simultaneous cannabis and alcohol use among adults 50 years and older. Future research is needed to monitor and educate older patients regarding co-use to minimize potential harms.

Limitations of this study include possible limited recall and social desirability bias. While more older adults use cannabis, the current clinical evidence to support its use in this population is limited.5 Older adults are especially vulnerable to potential adverse effects from cannabis,6 and with their increase in cannabis use, there is an urgent need to better understand both the benefits and risks of cannabis use in this population.

References

- 1.Han BH, Sherman S, Mauro PM, Martins SS, Rotenberg J, Palamar JJ. Demographic trends among older cannabis users in the United States, 2006-13. Addiction. 2017;112(3):516-525. doi: 10.1111/add.13670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han BH, Palamar JJ. Marijuana use by middle-aged and older adults in the United States, 2015-2016. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;191:374-381. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2018 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) releases. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/reports-detailed-tables-2018-NSDUH. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- 4.Subbaraman MS, Kerr WC. Subgroup trends in alcohol and cannabis co-use and related harms during the rollout of recreational cannabis legalization in Washington state. [published online July 24, 2019]. Int J Drug Policy. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briscoe J, Casarett D. Medical marijuana use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(5):859-863. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minerbi A, Häuser W, Fitzcharles MA. Medical cannabis for older patients. Drugs Aging. 2019;36(1):39-51. doi: 10.1007/s40266-018-0616-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]