Key Points

Question

Can endovascular treatment improve the clinical outcomes of patients with acute stroke and basilar artery occlusion?

Findings

In this nonrandomized cohort study of 829 consecutive patients with acute ischemic stroke and an acute, symptomatic, radiologically confirmed basilar artery occlusion, standard medical treatment plus endovascular treatment was associated with better outcomes than standard medical treatment alone (adjusted common odds ratio, 3.08 [95% CI, 2.09-4.55]; P < .001).

Meaning

In acute ischemic stroke attributable to basilar artery occlusion, endovascular treatment should be considered in addition to standard care in selected patients.

This nonrandomized cohort study evaluates the association between endovascular treatment and the clinical outcomes of patients with stroke and acute basilar artery occlusion, compared with patients who received standard medical treatment only.

Abstract

Importance

Several randomized clinical trials have recently established the safety and efficacy of endovascular treatment (EVT) of acute ischemic stroke in the anterior circulation. However, it remains uncertain whether patients with acute basilar artery occlusion (BAO) benefit from EVT.

Objective

To evaluate the association between EVT and clinical outcomes of patients with acute BAO.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nonrandomized cohort study, the EVT for Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion Study (BASILAR) study, was a nationwide prospective registry of consecutive patients presenting with an acute, symptomatic, radiologically confirmed BAO to 47 comprehensive stroke centers across 15 provinces in China between January 2014 and May 2019. Patients with acute BAO within 24 hours of estimated occlusion time were divided into groups receiving standard medical treatment plus EVT or standard medical treatment alone.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the improvement in modified Rankin Scale scores (range, 0 to 6 points, with higher scores indicating greater disability) at 90 days across the 2 groups assessed as a common odds ratio using ordinal logistic regression shift analysis, adjusted for prespecified prognostic factors. The secondary efficacy outcome was the rate of favorable functional outcomes defined as modified Rankin Scale scores of 3 or less (indicating an ability to walk unassisted) at 90 days. Safety outcomes included symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage and 90-day mortality.

Results

A total of 1254 patients were assessed, and 829 patients (of whom 612 were men [73.8%]; median [interquartile] age, 65 [57-74] years) were recruited into the study. Of these, 647 were treated with standard medical treatment plus EVT and 182 with standard medical treatment alone. Ninety-day functional outcomes were substantially improved by EVT (adjusted common odds ratio, 3.08 [95% CI, 2.09-4.55]; P < .001). Moreover, EVT was associated with a significantly higher rate of 90-day modified Rankin Scale scores of 3 or less (adjusted odds ratio, 4.70 [95% CI, 2.53-8.75]; P < .001) and a lower rate of 90-day mortality (adjusted odds ratio, 2.93 [95% CI, 1.95-4.40]; P < .001) despite an increase in symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (45 of 636 patients [7.1%] vs 1 of 182 patients [0.5%]; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with acute BAO, EVT administered within 24 hours of estimated occlusion time is associated with better functional outcomes and reduced mortality.

Introduction

Acute basilar artery occlusion (BAO) is a rare but potentially catastrophic medical condition accounting for 1% of all ischemic strokes and 5% of large vessel occlusion (LVO) strokes.1,2 Despite recent advances in the treatment of acute stroke, up to 68% of the patients with acute BAO die or remain severely disabled.3,4 Early recanalization of an occluded artery in acute stroke has been proven to be associated with favorable functional outcomes.5 Recanalization treatments include intravenous thrombolysis (IVT), intra-arterial thrombolysis, mechanical thrombectomy (MT), angioplasty, stenting, or combination therapies.2 Although intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA; Alteplase) remains the first-line treatment for acute ischemic stroke (AIS), its benefit is hampered by a short therapeutic window and limited recanalization in LVO strokes.6

Recently, 8 landmark endovascular treatment (EVT) trials have shown MT to be a safe and effective treatment for AIS attributable to LVO in the anterior circulation up 24 hours from stroke onset.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 However, it remains uncertain whether patients with an acute BAO benefit from EVT. Since 2013, 3 randomized clinical trials have been initiated: the Basilar Artery International Cooperation Study (BASICS), the Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion: Endovascular Interventions vs Standard Medical Treatment Trial (BEST), and Basilar Artery Occlusion: Chinese Endovascular Trial (BAOCHE; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02737189). All have aimed to investigate the benefit of standard medical treatment (SMT) plus EVT vs SMT alone in acute BAO.15,16 The BEST trial was terminated prematurely because of loss of equipoise that led to a high crossover rate and drop in valid recruitment,17 while the other 2 trials (BASICS and BAOCHE) are facing the challenge of whether they will achieve their inclusion target, because a growing number of stroke centers are unwilling to randomize patients to SMT alone after the many positive results of trials for EVT in patients with anterior-circulation stroke. Prospective data on EVT for acute BAO remain scarce. The BASICS trial used a prospective registry that enrolled 619 patients over the course of 5 years; BASICS did not find a significant difference in terms of functional outcome between patients undergoing EVT and usual care.3 However, because the study was concluded 10 years ago and therefore considerably before modern EVT techniques and mechanical recanalization devices became available, its findings may not be applicable to current practice.

Even though EVT for acute BAO has been previously evaluated in many case series and meta-analyses, these previous studies are limited by their single-arm nature, small sample sizes, heterogeneous treatment approaches, the use of outdated EVT techniques (ie, intra-arterial thrombolysis without mechanical recanalization or the use of first-generation mechanical recanalization devices, such as the mechanical embolus removal in cerebral ischemia [MERCI] retriever or small-bore Penumbra devices).4,18,19,20,21,22,23 The EVT for Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion Study (BASILAR) aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy of modern EVT plus SMT vs SMT alone in acute BAO within 24 hours of estimated occlusion time.

Method

Study Design

BASILAR is a nationwide prospective registry of consecutive patients 18 years or older who presented with an acute, symptomatic, radiologically confirmed BAO in 47 comprehensive stroke centers across 15 provinces in China. To avoid selection bias, all participating centers were obliged to enter all consecutive patients in the study. To be fully eligible for participation in this study, study centers were required to have performed at least 30 endovascular procedures annually, including at least 15 thrombectomy procedures with stent retriever devices. Moreover, all interventionists had to be certified in EVT of LVO strokes. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Xinqiao Hospital, Army Medical University, in Chongqing, China, and each subcenter. All patients or their legally authorized representatives provided signed, informed consent. BASILAR is registered on the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (http://www.chictr.org.cn; ChiCTR1800014759) (Protocol in Supplement 1).

Patients Selection

We included data of consecutive patients with AIS if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) an age 18 years or older; (2) presentation within 24 hours of estimated time of BAO; (3) a BAO confirmed by computed tomographic angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, or digital subtraction angiography; (4) initiation of intravenous rt-PA within 4.5 hours or intravenous urokinase within 6 hours of the estimated time of BAO; and (5) an ability to provide informed consent. For the SMT plus EVT group, EVT also had to be initiated within 24 hours of estimated time of BAO. Patients were excluded from the study in the case of (1) a clinically significant preexisting disability with a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score greater than 2; (2) neuroimaging evidence of cerebral hemorrhage on presentation; (3) a lack of follow-up information on outcomes at 90 days; (4) current pregnancy or lactation; (5) a serious, advanced, or terminal illness; and (6) incomplete baseline imaging and time-metric data.

Treatments

Patients were divided into the SMT-alone group (control group) or SMT-plus-EVT group (EVT group) according to the treatment they received. The SMT-alone group received SMT (eg, IVT with rt-PA or urokinase, antiplatelet drugs, systematic anticoagulation, or combinations of these medical treatments), as described in the guidelines for the management of AIS.24 Patients in the EVT group underwent SMT plus EVTs, which included MT with stent retrievers and/or thromboaspiration, balloon angioplasty, stenting, intra-arterial thrombolysis, or the various combinations of these approaches (eMethods 2 in Supplement 2).

Data Collection

We recorded patients’ baseline characteristics, stroke risk factors, laboratory findings, estimated time of BAO, stroke severity and neurological deficits at time of treatment, pretreatment and posttreatment imaging findings, type of treatment, EVT characteristics, complications, presumed stroke causative mechanism, and functional outcomes at 90 days. Details of the data elements are available in eTable 3 in Supplement 2.

Stroke severity at time of treatment was dichotomized as severe or mild to moderate. Patients in a coma, with tetraplegia, or in a locked-in state were classified as having a severe stroke, whereas mild-to-moderate stroke was defined as any deficit that was less than severe. The presumed stroke causative mechanism was assessed based on the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification.25 The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was used to assess neurological deficit at the time of treatment.26 The posterior circulation–Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score (pc-ASPECTS; range, 0 to 10, with scores ≥8 correlating with favorable outcomes) was used to quantify the ischemic changes on baseline imaging.27 Estimated time of BAO was defined as the time of onset of symptoms, as described by the patient or witness; consistent with the clinical diagnosis of BAO, on the judgment of the treating physician; or, if the exact time was not known, recorded as the last time the patient was seen well.

Outcome Measures

The primary clinical efficacy outcome was the score on the mRS at 90 days, as assessed by trained local neurologists who were blinded to the treatment-group assignments. The mRS is a 7-level scale (range, 0 [no symptoms] to 6 [death]) for the assessment of neurologic functional disability.28

The main secondary clinical efficacy outcome was the rate of favorable functional outcomes defined as mRS of 3 or less (indicating an ability to walk unassisted) at 90 days. Other outcome of interest included the change of the NIHSS score from baseline at 24 hours and at 5 to 7 days (or discharge, if earlier), as assessed by trained local neurologists. The technical efficacy outcomes regarding recanalization were substantial reperfusion, as assessed by means of catheter angiography in the EVT group and defined as a modified Treatment in Cerebral Infarction score of 2b (50%-99% reperfusion) or 3 (complete reperfusion).29

Safety outcomes were the incidence of death within 90 days and symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage at 48 hours as confirmed on neuroimaging (CT or MRI). Intracerebral hemorrhages were evaluated according to the Heidelberg Bleeding Classification (eMethods 3 in Supplement 2).30 Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage was diagnosed if the newly observed intracranial hemorrhage was associated with any of the following conditions: (1) an NIHSS score that increased more than 4 points than the score immediately before worsening; (2) an NIHSS score that increased more than 2 points in a category; or (3) deterioration that led to intubation, hemicraniectomy, external ventricular drain placement, or any other major interventions. Additionally, the symptom deteriorations had to be unexplained by causes other than the observed intracranial hemorrhage. An independent clinical events committee adjudicated safety outcomes, procedure-associated complications (eg, arterial perforation, arterial dissection, and embolization in a previously uninvolved vascular territory), and serious adverse events.

Radiologic Assessment

The imaging core laboratory evaluated the findings on baseline noncontrast computed tomography for the pc-ASPECTS, baseline vessel imaging (computed tomographic angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, or digital subtraction angiography) for the location of the occlusion, angiographic outcomes on digital subtraction angiography imaging for technical efficacy outcomes regarding reperfusion, follow-up computed tomographic angiography or magnetic resonance angiography within 48 hours for vessel recanalization, and the follow-up computed tomography for the presence of intracerebral hemorrhage.

All neuroimaging studies were evaluated independently by 2 neuroradiologists (W. Liu and W. Huang) who were unaware of the treatment-group assignments, clinical data, and outcomes. For cases with disagreement, decisions were made by a third experienced neuroradiologist (Z. Shi).

Statistical Analysis

We compared baseline characteristics, treatment profiles, outcomes, and severe adverse events between the SMT-alone and EVT groups. Data are presented as medians (interquartile ranges [IQRs]) or numbers with percentages, unless otherwise indicated. Univariate analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. The primary outcome variable was the adjusted common odds ratio for a shift in the direction of a better outcome on the mRS score; this ratio was estimated with multivariable ordinal logistic regression. The adjusted common odds ratios are reported with 95% CIs to indicate statistical precision. Adjusted estimates of outcome (common odds ratio, odds ratio, and β) were calculated by taking the following variables into account: age, baseline NIHSS, baseline pc-ASPECTS, onset-to-imaging diagnosis time, sex, diabetes mellitus, ischemic stroke, IVT, onset-to-outcome measurement time, and location of occlusion. For propensity score matching analysis, we performed a 1:1 matching based on the nearest-neighbor matching algorithm with a caliper width of 0.2 of the propensity score with age, systolic blood pressure, baseline pc-ASPECTS, baseline NIHSS, TOAST classification, occlusion site, and medical history, such as diabetes mellitus, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and ischemic stroke as covariates (eMethods 1 in Supplement 2).31 Furthermore, supportive analyses used the propensity score, computed based on multivariable regression models accounting for additional explanatory variables. The significance level was set to P < .05, and all tests of hypotheses were 2-sided. Because we excluded patients with missing essential data from our analysis, we did not impute for missing data. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 23.0 (IBM). Figures were drawn with the use of Excel software 2019 (Microsoft).

Results

Patient Characteristics

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we initially screened 1254 patients from 51 comprehensive stroke centers in China. Among them, 4 centers and 22 patients were excluded from participation in the registry because not all pertinent data on consecutive patients were being recorded. Another 71 patients were excluded because they had a BAO accompanied by anterior circulation LVO, 121 patients because of a chronic BAO, 187 patients because of missing critical baseline data (92 without records of time and 95 with poor quality of images), and 11 survivors because of lack of 90-day mRS scores. The remaining 829 patients (of whom 612 were men [73.8%]; median [interquartile] age, 65 [57-74] years) constituted the study population. The flowchart is shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 2; eFigure 2 in Supplement 2 shows the distribution of the participated centers in China. Participating centers and the number of patients recruited per center are listed in eTable 4 in Supplement 2.

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 182 patients were treated with SMT alone and 647 patients were treated with SMT plus EVT. Of the patients treated with SMT alone, 47 (25.8%) were treated with IVT (27 with rt-PA and 20 with urokinase). A total of 119 patients (18.4%) in the EVT group were treated with IVT (95 with rt-PA, 23 with urokinase, and 1 missing information about the thrombolytic type) in conjunction with EVT. Overall, 644 patients (77.7%) had severe deficits, and 185 patients (22.3%) had mild to moderate deficits. All patients completed the 90 days of follow-up.

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of these patients. Compared with the SMT-alone group, patients in the EVT group had a younger age (67 [59-76] years vs 64 [56-73] years; P = .002), higher pc-ASPECTS score (median [IQR], 7 [6-8] vs 8 [7-9]; P < .001), lower systolic blood pressure levels (median [IQR], 160 [142-174] mm Hg vs 150 [134-166] mm Hg; P < .001), higher proportions of smoking (42 of 182 patients [23.1%] vs 235 of 647 patients [36.3%]; P = .001) and atrial fibrillation (24 of 182 patients [13.2%] vs 136 of 647 patients [21.0%]; P = .02), and a significant difference of stroke causative mechanism (eg, cardioembolism: 32 of 182 patients [17.6%] vs 173 of 647 patients [26.7%]; P = .001) and occlusion sites (distal basilar artery: 45 of 182 [24.7%] vs 222 of 647 [34.3%]; middle basilar artery: 100 of 182 [54.9%] vs 195 of 647 [30.1%]; proximal basilar artery: 14 of 182 [7.7%] vs 107 of 647 [16.5%]; vertebral artery–V4 segment: 23 of 182 [12.6%] vs 123 of 647 [19.0%]; P < .001). Other baseline characteristics were not statistically different between the 2 groups.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics and Process Measures.

| Baseline Characteristic | No./Total No. (%) | χ2/z Value | P Value | Propensity Score Matching | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Control | EVT | No./No. (%) | χ2/z Value | P Value | |||||

| All | Control | EVT | ||||||||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 65 (57-74) | 67 (59-76) | 64 (56-73) | z = −3.057 | .002 | 67 (59-75) | 66 (59-75) | 67 (60-75) | z = −0.185 | .85 |

| ≥65 | 428/829 (51.6) | 109/182 (59.9) | 319/647 (49.3) | χ21 = 6.373 | .01 | 190/334 (56.9) | 96/167 (57.5) | 94/167 (56.3) | χ21 = 0.049 | .83 |

| Male | 612/829 (73.8) | 129/182 (70.9) | 483/647 (74.7) | χ21 = 1.046 | .31 | 233/334 (69.8) | 120/167 (71.9) | 113/167 (67.7) | χ21 = 0.695 | .40 |

| Baseline NIHSS score, median (IQR) | 27 (16-33) | 26.5 (16-33) | 27 (17-33) | z = −0.658 | .51 | 25 (14-32) | 25 (15-32) | 24 (14-32) | z = −0.469 | .64 |

| ≥27 | 417/829 (50.3) | 91/182 (50.0) | 326/647 (50.4) | χ21 = 0.008 | .93 | 154/334 (46.1) | 80/167 (47.9) | 74/167 (44.3) | χ21 = 0.434 | .51 |

| Deficit at time of treatment | ||||||||||

| Mild to moderate | 185/829 (22.3) | 45/182 (24.7) | 140/647 (21.6) | χ21 = 0.781 | .38 | 88/334 (26.3) | 44/167 (26.3) | 44/167 (26.3) | χ21 = 0.000 | >.99 |

| Severe | 644/829 (77.7) | 137/182 (75.3) | 507/647 (78.4) | 246/334 (73.7) | 123/167 (73.7) | 123/167 (73.7) | ||||

| Baseline pc-ASPECTS, median (IQR) | 8 (7-9) | 7 (6-8) | 8 (7-9) | z = −5.351 | <.001 | 7 (6-9) | 7 (6-8) | 8 (7-9) | z = −1.562 | .12 |

| ≥8 | 468/823 (56.9) | 78/180 (43.3) | 390/643 (60.7) | χ21 = 17.199 | <.001 | 163/334 (48.8) | 78/167 (46.7) | 85/167 (50.9) | χ21 = 0.587 | .44 |

| ASITN/SIR grade | ||||||||||

| 0-1 | 509/829 (61.4) | 119/182 (65.4) | 390/647 (60.3) | χ22 = 2.831 | .24 | 200/334 (59.9) | 105/167 (62.9) | 95/167 (56.9) | χ22 = 4.140 | .13 |

| 2 | 213/829 (25.7) | 38/182 (20.9) | 175/647 (27.0) | 92/334 (27.5) | 38/167 (22.8) | 54/167 (32.3) | ||||

| 3-4 | 107/829 (12.9) | 25/182 (13.7) | 82/647 (12.7) | 42/334 (12.6) | 24/167 (14.4) | 18/167 (10.8) | ||||

| PC-CS score, median (IQR) | 4 (3-6) | 4 (3-6) | 4 (3-6) | z = −1.147 | .25 | 5 (4-6) | 5 (4-6) | 5 (4-6) | z = −0.287 | .77 |

| ≥5 | 410/828 (49.5) | 89/182 (48.9) | 321/646 (49.7) | χ21 = 0.035 | .85 | 181/334 (54.2) | 87/167 (52.1) | 94/167 (56.3) | χ21 = 0.591 | .44 |

| Prodromal transient ischemic attack or minor stroke | 397/829 (47.9) | 95/182 (52.2) | 302/647 (46.7) | χ21 = 1.735 | .19 | 167/334 (50.0) | 89/167 (53.3) | 78/167 (46.7) | χ21 = 1.449 | .23 |

| Body temperature, median (IQR), °C | 36.6 (36.5-36.8) | 36.6 (36.5-36.9) | 36.6 (36.5-36.8) | z = −1.521 | .13 | 36.6 (36.5-36.8) | 36.6 (36.5-36.9) | 36.6 (36.5-36.8) | z = −0.890 | .37 |

| Serum glucose, median (IQR), mmol/L | 7.4 (6.0-9.6) | 7.3 (5.8-9.0) | 7.4 (6.1-9.7) | z = −1.271 | .20 | 7.3 (5.9-9.4) | 7.3 (5.7-9.0) | 7.3 (6.1-9.6) | z = −1.020 | .31 |

| Blood pressure on admission, median (IQR), mm Hg | ||||||||||

| Systolic | 151 (135-169) | 160 (142-174) | 150 (134-166) | z = −4.004 | <.001 | 155 (140-171) | 156 (140-171) | 152 (133-173) | z = −1.066 | .29 |

| Diastolic | 85 (78-98) | 89 (80-100) | 85 (77-97) | z = −2.446 | .01 | 87 (80-97) | 88 (80-98) | 86 (78-97) | z = −1.210 | .23 |

| Medical history | ||||||||||

| Hypertension | 585/829 (70.6) | 134/182 (73.6) | 451/647 (69.7) | χ21 = 1.051 | .31 | 249/334 (74.6) | 126/167 (75.4) | 123/167 (73.7) | χ21 = 0.142 | .71 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 283/829 (34.1) | 69/182 (37.9) | 214/647 (33.1) | χ21 = 1.478 | .22 | 118/334 (35.3) | 65/167 (38.9) | 53/167 (31.7) | χ21 = 1.887 | .17 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 189/829 (22.8) | 40/182 (22.0) | 149/647 (23.0) | χ21 = 0.089 | .77 | 77/334 (23.1) | 36/167 (21.6) | 41/167 (24.6) | χ21 = 0.422 | .52 |

| Smoking | 277/829 (33.4) | 42/182 (23.1) | 235/647 (36.3) | χ21 = 11.199 | .001 | 86/334 (25.7) | 42/167 (25.1) | 44/167 (26.3) | χ21 = 0.063 | .80 |

| Ischemic stroke | 188/829 (22.7) | 48/182 (26.4) | 140/647 (21.6) | χ21 = 1.816 | .18 | 81/334 (24.3) | 43/167 (25.7) | 38/167 (22.8) | χ21 = 0.407 | .52 |

| Coronary heart disease | 132/829 (15.9) | 27/182 (14.8) | 105/647 (16.2) | χ21 = 0.206 | .65 | 53/334 (15.9) | 26/167 (15.6) | 27/167 (16.2) | χ21 = 0.022 | .88 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 160/829 (19.3) | 24/182 (13.2) | 136/647 (21.0) | χ21 = 5.596 | .02 | 53/334 (15.9) | 22/167 (13.2) | 31/167 (18.6) | χ21 = 1.817 | .18 |

| Stroke causative mechanism | ||||||||||

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 539/829 (65.0) | 121/182 (66.5) | 418/647 (64.6) | χ23 = 17.381 | .001 | 232/334 (69.5) | 117/167 (70.7) | 115/167 (68.9) | χ23 = 2.356 | .50 |

| Cardioembolism | 205/829 (24.7) | 32/182 (17.6) | 173/647 (26.7) | 69/334 (20.7) | 31/167 (18.6) | 38/167 (22.8) | ||||

| Other | 23/829 (2.8) | 4/182 (2.2) | 19/647 (2.9) | 9/334 (2.7) | 4/167 (2.4) | 5/167 (3.0) | ||||

| Unknown | 62/829 (7.5) | 25/182 (13.7) | 37/647 (5.7) | 24/334 (7.2) | 15/167 (9.0) | 9/167 (5.4) | ||||

| Occlusion sites | ||||||||||

| Distal basilar artery | 267/829 (32.2) | 45/182 (24.7) | 222/647 (34.3) | χ23 = 39.506 | <.001 | 80/334 (24.0) | 40/167 (24.0) | 40/167 (24.0) | χ23 = 0.000 | >.99 |

| Middle basilar artery | 295/829 (35.6) | 100/182 (54.9) | 195/647 (30.1) | 188/334 (56.3) | 94/167 (56.3) | 94/167 (56.3) | ||||

| Proximal basilar artery | 121/829 (14.6) | 14/182 (7.7) | 107/647 (16.5) | 26/334 (7.8) | 13/167 (7.8) | 13/167 (7.8) | ||||

| Vertebral artery–V4 segment | 146/829 (17.6) | 23/182 (12.6) | 123/647 (19.0) | 40/334 (12.0) | 20/167 (12.0) | 20/167 (12.0) | ||||

| Treatment profiles | ||||||||||

| Intravenous thrombolysis | 166/829 (20.0) | 47/182 (25.8) | 119/647 (18.4) | χ21 = 4.899 | .03 | 73/334 (21.9) | 43/167 (25.7) | 30/167 (18.0) | χ21 = 2.963 | .09 |

| Onset to imaging diagnosis time, median (IQR), min | 204 (88-356) | 194 (87-388) | 210 (88-354) | z = −1.323 | .19 | 204 (79-358) | 185 (80-351) | 216 (72-361) | z = 0.468 | .64 |

| Onset to treatment, median (IQR), min | 245 (128.5-393.5) | 221.5 (116.25-407) | 246 (132-390) | z = −0.272 | .79 | 240.5 (117-393.25) | 219 (111-398) | 253 (125-385) | z = −0.483 | .63 |

| Onset to treatment, h | ||||||||||

| 0-3 | 303/829 (36.6) | 71/182 (39.0) | 232/647 (35.9) | χ23 = 3.554 | .31 | 129/334 (38.6) | 67/167 (40.1) | 62/167 (37.1) | χ23 = 1.450 | .69 |

| 3-6 | 287/829 (34.6) | 56/182 (30.8) | 231/647 (35.7) | 107/334 (32.0) | 51/167 (30.5) | 56/167 (33.5) | ||||

| 6-9 | 124/829 (15.0) | 24/182 (13.2) | 100/647 (15.5) | 47/334 (14.1) | 21/167 (12.6) | 26/167 (15.6) | ||||

| >9 | 115/829 (13.9) | 31/182 (17.0) | 84/647 (13.0) | 51/334 (15.3) | 28/167 (16.8) | 23/167 (13.8) | ||||

| Onset to groin puncture, median (IQR), min | NA | NA | 328 (220-493) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 350 (219-531) | NA | NA |

| Onset to revascularization, median (IQR), min | NA | NA | 441 (328-627) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 470 (326-680) | NA | NA |

| Groin puncture to revascularization, median (IQR), min | NA | NA | 105 (71-151) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 112 (75-169) | NA | NA |

| General anesthesia | NA | NA | 257/639 (40.2) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 64/164 (39.0) | NA | NA |

| Type of endovascular treatment | ||||||||||

| Stent retriever thrombectomy | NA | NA | 482/643 (75.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 120/167 (71.9) | NA | NA |

| Aspiration | NA | NA | 20/643 (3.1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4/167 (2.4) | NA | NA |

| Balloon angioplasty and/or stenting | NA | NA | 66/643 (10.2) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 22/167 (13.2) | NA | NA |

| Intra-arterial medication and/or mechanical fragmentation | NA | NA | 75/643 (11.7) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 21/167 (12.6) | NA | NA |

| Combination | NA | NA | 422/643 (65.6) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 116/167 (69.5) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: ASITN/SIR, American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology/Society of Interventional Radiology System; EVT, endovascular treatment; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; pc-ASPECTS, Posterior Circulation-Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score; PC-CS, Posterior Circulation Collateral Score.

SI conversion factor: To convert glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555.

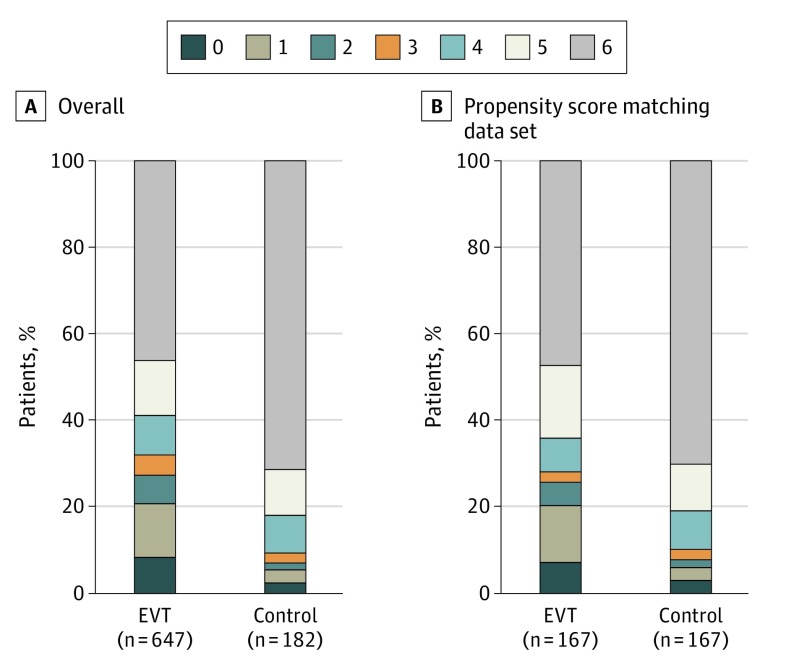

Primary Efficacy Outcome

Analysis of the primary outcome showed an adjusted common odds ratio (OR) for any improvement in the distribution of the mRS score of 3.08 (95% CI, 2.09-4.55) favoring EVT (Table 2; Figure 1). The median 90-day mRS score was 5 (IQR, 2-6) in the EVT group and 6 (IQR, 5-6) in the SMT-alone group (P < .001; Table 2).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Efficacy Outcomes and Safety Outcomes.

| Characteristic | No./No. (%) | Unadjusted Outcome Variable Value (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted Value (95% CI)a | P Value | Propensity Score Matching | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Control | EVT | No./Total No. (%) | χ2/z Value | P Value | |||||||

| All | Control | EVT | ||||||||||

| Primary efficacy outcome | ||||||||||||

| Modified Rankin Scale score at 90 d, median (IQR) | 6 (3-6) | 6 (5-6) | 5 (2-6) | 3.09 (2.17-4.39)b | <.001 | 3.08 (2.09-4.55) | <.001 | 6 (4-6) | 6 (5-6) | 5 (2-6) | z = −4.513 | <.001 |

| Secondary efficacy outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Modified Rankin Scale score at 90 d | ||||||||||||

| 0-3 | 224/829 (27.0) | 17/182 (9.3) | 207/647 (32.0) | 4.57 (2.70-7.73)c | <.001 | 4.70 (2.53-8.75) | <.001 | 64/334 (19.2) | 17/167 (10.2) | 47/167 (28.1) | χ21 = 17.396 | <.001 |

| 0-2 | 190/829 (22.9) | 13/182 (7.1) | 177/647 (27.4) | 4.90 (2.71-8.83)c | <.001 | 4.90 (2.43-9.87) | <.001 | 56/334 (16.8) | 13/167 (7.8) | 43/167 (25.7) | χ21 = 19.309 | <.001 |

| 0-1 | 144/829 (17.4) | 10/182 (5.5) | 134/647 (20.7) | 4.49 (2.31-8.74)c | <.001 | 4.54 (2.16-9.56) | <.001 | 44/334 (13.2) | 10/167 (6.0) | 34/167 (20.4) | χ21 = 15.077 | <.001 |

| NIHSS score, median (IQR) | ||||||||||||

| Change from baseline at 24 he | 0 (−2 to 3) | 0 (0-6) | 0 (−4 to 3) | −4.16 (−5.77 to −2.55)d | <.001 | −3.35 (−4.98 to −1.71) | <.001 | 0 (0-4) | 0 (0-5) | 0 (−3 to 4) | z = −1.794 | .07 |

| Change from baseline at 5-7 df | 0 (−9 to 4) | 1 (0-9.5) | −2 (−12 to 3) | −7.20 (−9.25 to −5.16)d | <.001 | −6.28 (−8.33 to −4.21) | <.001 | 0 (−5 to 6) | 1 (0-10) | 0 (−8 to 4) | z = −4.077 | <.001 |

| mTICI score of 2b or 3 at final angiogram | 533/829 (64.3) | 11/182 (6.0) | 522/647 (80.7) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 143/334 (42.8) | 11/167 (6.6) | 132/167 (79.0) | χ21 = 179.039 | <.001 |

| Safety outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Mortality at 90 d | 429/829 (51.7) | 130/182 (71.4) | 299/647 (46.2) | 2.91 (2.04-4.16)c | <.001 | 2.93 (1.95-4.40) | <.001 | 196/334 (58.7) | 117/167 (70.1) | 79/167 (47.3) | χ21 = 17.831 | <.001 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | <.001 | NA | ||||||||||

| Symptomatic | 46/818 (5.6) | 1/182 (0.5) | 45/636 (7.1) | NA | NA | 13/331 (3.9) | 1/167 (0.6) | 12/164 (7.3) | χ22 = 19.029 | <.001 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 17/818 (2.1) | 0 | 17/636 (2.7) | NA | NA | 5/331 (1.5) | 0 | 5/164 (3.0) | ||||

Abbreviations: EVT, endovascular treatment; mTICI, Modified Treatment in Cerebral Infarction; NA, not applicable; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Adjusted estimates of outcome were calculated using multiple regression, taking the following variables into account: age, baseline NIHSS score, baseline pc-ASPECTS, onset-to-imaging diagnosis time, sex, intravenous thrombolysis, diabetes mellitus, ischemic stroke, onset-to–outcome measurement time, and location of occlusion.

Common odds ratio; the primary analysis involved 647 patients in the endovascular treatment group and 182 patients in the control group. Scores on the mRS of functional disability range from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death). The common odds ratio was estimated from an ordinal logistic regression model and indicates the odds of improvement of 1 point on the mRS, with a common odds ratio greater than 1 favoring the endovascular treatment.

The odds ratios were estimated from a binary logistic regression model.

The β values were estimated from a multivariable linear regression model.

The NIHSS score was determined for survivors only. The score was not available for 7 patients; 4 died before assessment was finished, and 3 had missing scores. In the propensity score matching data set, the score was not available for 1 patient who died before assessment was finished.

The NIHSS score was determined for survivors only. The score was not available for 40 patients; 37 died before assessment was finished, and 3 had missing scores. In the propensity score matching data set, the score was not available for 16 patients because they died before assessment was finished.

Figure 1. Distribution of the Modified Rankin Scale Score at 90 Days in All Patients and the Propensity Score Matching Data Set.

EVT indicates endovascular treatment.

Secondary Efficacy Outcomes

Secondary clinical efficacy outcomes and technical efficacy outcomes regarding recanalization are shown in Table 2. The proportion of favorable outcomes (mRS score ≤3) at 90 days was significantly higher in the EVT group than in the SMT-alone group (207 of 647 patients [32.0%] vs 17 of 182 patients [9.3%]; P < .001; absolute difference: 22.7% [95% CI, 17.1%-28.2%]) with an adjusted OR of 4.70 (95% CI, 2.53-8.75; P < .001; number needed to treat for 1 additional patient to be able to walk unassisted, 4.4). The differences in the NIHSS scores between baseline and 24 hours and baseline and at 5 to 7 days or discharge were 0 (IQR, 0-6) points vs 0 (IQR, −4 to 3) points (β, −3.35 [95% CI, −4.98 to −1.71]) and 1 (IQR, 0-9.5) points vs −2 (IQR, −12 to 3) points (β, −6.28 [95% CI, −8.33 to −4.21]) across the SMT-alone and EVT groups, respectively (P < .001). In the EVT group, substantial reperfusion at the end of the procedure occurred in 522 of the 647 patients (80.7%).

Safety Outcomes

Mortality at 90 days was significantly higher in the SMT-alone group than in the EVT group (299 of 647 patients [46.2%] vs 130 of 182 patients [71.4%]; P < .001; absolute difference: 25.2% [95% CI, 17.6%-2.8%]), with an adjusted OR of 2.93 (95% CI, 1.95-4.40; P < .001). The rate of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage was 7.1% (45 of 636 patients) in the EVT group and 0.5% (1 of 182 patients) in the SMT-alone group (P < .001). Device-associated or procedural complications were observed in 62 patients (9.6%). Rates of other serious adverse events during the 90-day follow-up period were similar in the 2 study groups, except deep-vein thrombosis. A complete list of procedural complications and adverse events were provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Procedural-Associated Complications and Reported Severe Adverse Events.

| Characteristic | No./Total No. (%) | χ2 Valuea | P Value | Propensity Score Matching | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Control | EVT | No./ Total No. (%) | χ2 Valuea | P Value | |||||

| All | Control | EVT | ||||||||

| Procedural-associated complications | ||||||||||

| Arterial perforation | NA | NA | 7/647 (1.1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1/167 (0.6) | NA | NA |

| Arterial dissection | NA | NA | 10/647 (1.5) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3/167 (1.8) | NA | NA |

| Distal embolization | NA | NA | 27/647 (4.2) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5/167 (3.0) | NA | NA |

| Cerebral vasospasm requiring treatmentb | NA | NA | 18/647 (2.8) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5/167 (3.0) | NA | NA |

| Severe adverse events within 90 d | ||||||||||

| Hemicraniectomy | 16/829 (1.9) | 2/182 (1.1) | 14/647 (2.2) | 0.965 | .33 | 8/334 (2.4) | 2/167 (1.2) | 6/167 (3.6) | 2.142 | .14 |

| Pneumonia | 624/829 (75.3) | 141/182 (77.5) | 483/647 (74.7) | 0.607 | .47 | 259/334 (77.5) | 132/167 (79.0) | 127/167 (76.0) | 0.430 | .51 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 336/829 (40.5) | 73/182 (40.1) | 263/647 (40.6) | 0.017 | .90 | 141/334 (42.2) | 65/167 (38.9) | 76/167 (45.5) | 1.485 | .22 |

| Acute heart failure | 197/829 (23.8) | 47/182 (25.8) | 150/647 (23.2) | 0.547 | .46 | 89/334 (26.6) | 43/167 (25.7) | 46/167 (27.5) | 0.138 | .71 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 152/829 (18.3) | 38/182 (20.9) | 114/647 (17.6) | 1.008 | .32 | 70/334 (21.0) | 37/167 (22.2) | 33/167 (19.8) | 0.289 | .59 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 48/829 (5.8) | 5/182 (2.7) | 43/647 (6.6) | 3.958 | .047 | 21/334 (6.3) | 4/167 (2.4) | 17/167 (10.2) | 8.588 | .003 |

Abbreviations: EVT, endovascular treatment; NA, not available.

Degrees of freedom for all χ2 values were equal to 1.

Vasospasm events were reported by local investigators and the angiography core laboratory.

Propensity Score Matching Analysis

After 1:1 propensity score matching analysis, baseline characteristics between the groups achieved good balance. Details are available in Table 1. A total of 167 patients who had EVT were evaluable for the matched-pairs analysis with the multivariable method. The score on the mRS at 90 days, indicating a primary efficacy functional outcome, was significantly lower in the EVT group than in the SMT-alone group (5 [IQR, 2-6] vs 6 [IQR, 4-6]; P < .001). Compared with the SMT-alone group, the proportion of favorable 90-day functional outcome (mRS score ≤3) in the EVT group was significantly higher (47 of 167 patients [28.1%] vs 17 of 167 patients [10.2%]; P < .001). Mortality at 90 days occurred in 79 of 167 patients (47.3%) in the EVT group and 117 of 167 patients (70.1%) in the SMT-alone group (P < .001). The rate of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage was 7.3% (12 of 164 patients) in the EVT group and 0.6% in the SMT-alone group (1 of 167 patients; P < .001). Substantial reperfusion was achieved in 132 of 167 patients (79.0%) in the EVT group. Results are shown in Table 2. In addition, supportive analyses, in which propensity scores were included into multivariable regression models as a covariate, were performed. The results were consistent (eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 2).

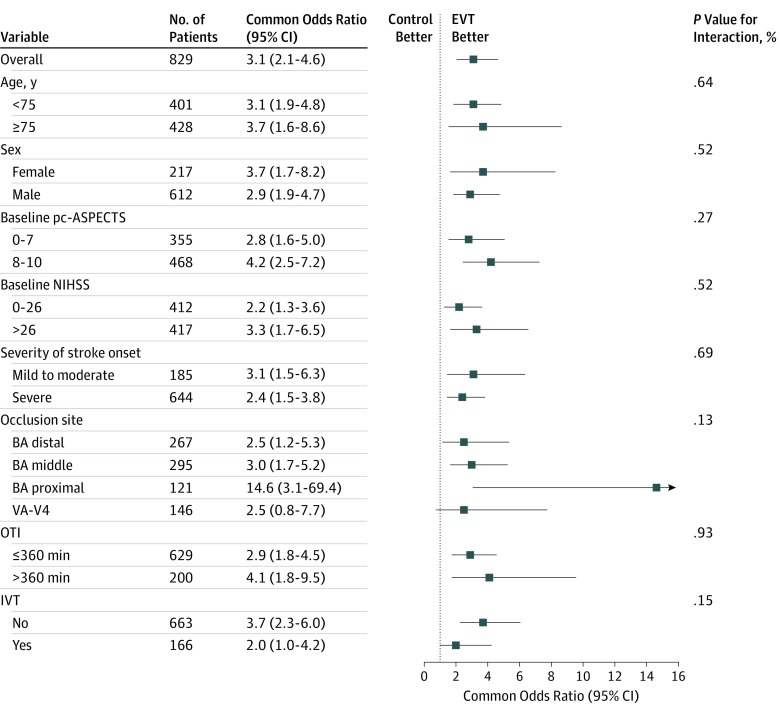

Subgroup Analyses

Subgroup analyses were based on the full data set. The treatment outcome remained consistent in almost all of predefined subgroups, including those based on age, sex, baseline pc-ASPECTS, baseline NIHSS, site of occlusion, time from onset to imaging diagnosis, and IVT (Figure 2; eFigures 3 through 20 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Subgroup Analyses.

This forest plot shows that the difference in the primary clinical outcome (common odds ratio indicating the odds of improvement of 1 point on the modified Rankin Scale at 90 days, analyzed with the use of ordinal logistic regression) favored the endovascular treatment (EVT) group across all prespecified subgroups. The common odds ratio was calculated by using ordinal logistic regression taking the following variables into account: age, baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score (NIHSS), baseline posterior circulation–Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score (pc-ASPECTS), onset to imaging diagnosis time, sex, diabetes mellitus, ischemic stroke, intravenous thrombolysis, onset to outcome measurement time, and location of occlusion. The thresholds for baseline NIHSS and baseline pc-ASPECTS were chosen at the median, and the thresholds for age and time from stroke onset to imaging diagnosis were chosen at the 75th percentile. BA indicates basilar artery; IVT, intravenous thrombolysis; OTI, onset-to-imaging diagnosis time; VA–V4, the fourth segment of vertebral artery.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current analysis represents the largest prospective, multicenter registry of consecutive patients presenting with acute symptomatic BAO. The importance of our study becomes even more important in face of the paucity of prospective data comparing the outcomes of SMT plus EVT vs SMT alone for patients with BAO, as well as the challenges faced to randomization in this patient population.32 Our study showed that, in the real-world practice, patients with AIS and confirmed acute symptomatic BAO appear to benefit with respect to functional recovery when EVT is administered within 24 hours of estimated occlusion time. Patients treated with EVT were more likely able to walk independently at 90-day follow-up visits.

Our findings stand in clear distinction to the BASICS registry, which failed to show a benefit of EVT. The efficacy EVT for AIS caused by anterior-circulation LVO has come a long way to be proven in the past decade. Unlike the Interventional Management of Stroke III trial,33 Mechanical Retrieval and Recanalization of Stroke Clots Using Embolectomy (MR RESCUE) trial,34 and the Local vs Systemic Thrombolysis for AIS (SYNTHESIS Expansion) trial,35 6 landmark EVT early-window trials had positive results because of better patient selection, application of EVT with adjunctive thrombolysis, and the use of modern stent retrievers.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 In the BASICS registry, the benefit from the EVT was limited to the use of outdated EVT techniques (ie, intra-arterial thrombolysis without mechanical recanalization) and the use of first-generation mechanical recanalization devices.3 As reported previously, the frequency of recanalization after stent retrievers (81%) exceeds that of previously published recanalization rates of 46.2% or 63.2% after intravenous rt-PA or intra-arterial thrombolysis, respectively.36 In the Solitaire with the Intention for Thrombectomy (SWIFT) trial, recanalization was achieved more often in the Solitaire group than in the Merci group (61% vs 24%; P < .001), and more patients had a good 90-day functional outcome with Solitaire than Merci (58% vs 33%; P = .02).37 Similar superiority over the Merci device was subsequently reported in a randomized comparison trial with the Trevo device.38

In the EVT group of our study, we observed a good outcome (mRS scores ≤2) in 27.5% of the patients. Although this may seem relatively low compared with other recent studies (34%-45%),4,19,21,39,40,41 including a meta-analysis by Gory et al23 of case series of EVT for patients with BAO, this study had more patients with large-artery atherosclerosis stroke (418 of 647 [64.6%]), with 20.3% having a mRS score of 2 or less. This result was consistent with the previous study,39,42 which found that stroke mechanism has a major influence on outcomes and in situ atherosclerotic thrombosis mechanism (compared with embolism) was significantly associated with poor outcomes. Severe neurological condition on admission, particularly reduced consciousness, may lessen the benefits of recanalization and hinder prognosis. In addition, given the high proportion of poor outcome in the natural history of BAO3 and the fact that only 7% of patients included in the SMT-alone group of our study had a good outcome, our rates of observed mRS scores of 0 to 2 become relatively favorable. However, patients treated with antithrombotics or IVT in the BASICS registry had a much higher good outcome rate of 38%. This much higher chance of a good outcome among patients treated with SMT in the BASICS registry can be explained by the limited number of patients treated with additional EVT after IVT. Moreover, about 44.7% patients in the antithrombotic or IVT group of the BASICS registry had an NIHSS of more than 20, which was much lower than that of the BASILAR registry (44.7% vs 61.0%; P < .001). The rate of substantial reperfusion we observed (80.7%) was comparable with the 81% reported in the previous meta-analysis by Gory et al.23

As reported previously, our study also confirmed the safety of EVT for acute BAO is acceptable. The rate of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage was 7.1% in the EVT group of the present study, which was comparable with the rate of 4% (95% CI, 2%-8%) reported in the meta-analysis by Gory et al23 and much lower than the 14% reported in the BASICS registry, probably reflecting the more advanced intervention techniques available today. The mortality rate observed in the EVT group of our study was 46.2%, which was significantly lower than 72.2% in the SMT-alone group and relatively higher than those previously reported after mechanical recanalization (Kang et al,19 16%; Weber et al,41 34%; Mokin et al,21 30%; Singer et al,4 35%; and a meta-analysis by Gory et al,23 30%). However, our mortality rate was comparable with that reported in other previous studies (Gory et al,40 44%; Bouslama et al,22 46.7%). The high mortality rate observed here could be explained by the delayed observed reperfusion times and the severity of stroke deficits, both well-known factors for worse prognosis.23 The rate of procedure-associated complications was 9.6% in our study, comparable with the 10% reported in a meta-analysis study by Lee et al.42

Limitations

Our study has all the inherent limitations of a nonrandomized study. The reasons for clinicians to select a specific treatment option are more complex than can be covered by the scope of a prospective observational study. Propensity score matching or multivariable analyses can never adjust completely for systematic differences between treatment groups, which is the aim of randomization in clinical trials. The high number of patients who received SMT and EVT compared with SMT alone may suggest the existence of a lack of equipoise among participating centers in regards to the efficacy of EVT in patients with BAO. However, our registry makes up a good representation of daily clinical practice for patients with acute symptomatic BAO, and despite its limitations, it still constitutes one of the best available data about BAO treatment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study contributes evidence to support the safety and efficacy of EVT for patients with AIS caused by BAO who could be treated within 24 hours of estimated occlusion time. We are looking forward to the results of the 2 randomized clinical trials, BASICS and BAOCHE, that may have important influence on the management of these patients.

Protocol.

eMethods 1. Propensity Matching Score Analysis,

eMethods 2. Treatment method.

eMethods 3. Definition of sICH and aICH.

eTable 1. Ordinal regression model of primary outcome based on PSM dataset including the propensity score as a covariate.

eTable 2. Multivariate regression models of outcomes based on the full dataset including the propensity score as a covariate.

eTable 3. Data elements in the BASILAR cohort study.

eTable 4. Participating centers and eligible patients.

eFigure 1. Consort flow diagram of the BASILAR study.

eFigure 2. Distribution of the BASILAR study centers on the map of China.

eFigure 3. Horizontal stacked bar graphs of mRS outcome by key co-variables in all subjects. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects with age >= 65 years vs. < 65 years. Threshold for age was chosen at the median. EVT denotes endovascular treatment.

eFigure 4. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects stratified by sex.

eFigure 5. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects with stratified by baseline NIHSS ( >= 27 or < 27 ).

eFigure 6. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects with baseline pc-ASPECTS < 8 vs. >= 8.

eFigure 7. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects stratified by TOAST subtype (large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) or cardiac embolism (CE) or other).

eFigure 8. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects stratified by occlusion site (BA distal or BA middle or BA proximal or VA-V4).

eFigure 9. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects stratified by occlusion site (BA middle or non BA middle).

eFigure 10. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects with time from stroke onset to imaging diagnosis (OTI) <= 360 min vs. > 360 min.

eFigure 11. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects stratified by intravenous thrombolysis (IVT).

eFigure 12. Horizontal stacked bar graphs of mRS outcome by key co-variables in the propensity score matching (PSM) dataset Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset with age >= 65 years vs. < 65 years.

eFigure 13. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset stratified by sex.

eFigure 14. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset with stratified by baseline NIHSS ( >= 26 or < 26 ).

eFigure 15. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset with baseline pc-ASPECTS < 8 vs. >= 8.

eFigure 16. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset stratified by TOAST subtype (large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) or cardiac embolism (CE) or other).

eFigure 17. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset stratified by occlusion site (BA distal or BA middle or BA proximal or VA-V4).

eFigure 18. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset stratified by occlusion site (BA middle or non BA middle).

eFigure 19. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset with time from stroke onset to imaging diagnosis (OTI) <= 360 min vs. > 360 min.

eFigure 20. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset stratified by intravenous thrombolysis (IVT).

eReferences.

References

- 1.Smith WS, Lev MH, English JD, et al. . Significance of large vessel intracranial occlusion causing acute ischemic stroke and TIA. Stroke. 2009;40(12):3834-3840. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.561787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattle HP, Arnold M, Lindsberg PJ, Schonewille WJ, Schroth G. Basilar artery occlusion. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(11):1002-1014. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70229-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schonewille WJ, Wijman CA, Michel P, et al. ; BASICS study group . Treatment and outcomes of acute basilar artery occlusion in the Basilar Artery International Cooperation Study (BASICS): a prospective registry study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(8):724-730. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70173-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singer OC, Berkefeld J, Nolte CH, et al. ; ENDOSTROKE Study Group . Mechanical recanalization in basilar artery occlusion: the ENDOSTROKE study. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(3):415-424. doi: 10.1002/ana.24336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kharitonova TV, Melo TP, Andersen G, Egido JA, Castillo J, Wahlgren N; SITS investigators . Importance of cerebral artery recanalization in patients with stroke with and without neurological improvement after intravenous thrombolysis. Stroke. 2013;44(9):2513-2518. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asadi H, Dowling R, Yan B, Wong S, Mitchell P. Advances in endovascular treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. Intern Med J. 2015;45(8):798-805. doi: 10.1111/imj.12652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bracard S, Ducrocq X, Mas JL, et al. ; THRACE investigators . Mechanical thrombectomy after intravenous alteplase versus alteplase alone after stroke (THRACE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(11):1138-1147. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30177-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. ; SWIFT PRIME Investigators . Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2285-2295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, et al. ; REVASCAT Trial Investigators . Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2296-2306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, et al. ; MR CLEAN Investigators . A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):11-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. ; EXTEND-IA Investigators . Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(11):1009-1018. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. ; ESCAPE Trial Investigators . Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(11):1019-1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, et al. ; DEFUSE 3 Investigators . Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):708-718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nogueira RG, Jadhav AP, Haussen DC, et al. ; DAWN Trial Investigators . Thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke with a mismatch between deficit and infarct. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):11-21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Hoeven EJ, Schonewille WJ, Vos JA, et al. ; BASICS Study Group . The Basilar Artery International Cooperation Study (BASICS): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:200. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, Xu G, Liu Y, et al. ; BEST Trial Investigators . Acute basilar artery occlusion: endovascular interventions versus standard medical treatment (BEST) trial-design and protocol for a randomized, controlled, multicenter study. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(7):779-785. doi: 10.1177/1747493017701153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Dai Q, Ye R, et al. ; BEST Trial Investigators . Endovascular treatment versus standard medical treatment for vertebrobasilar artery occlusion (BEST): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(2):115-122. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30395-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Houwelingen RC, Luijckx GJ, Mazuri A, Bokkers RP, Eshghi OS, Uyttenboogaart M. Safety and outcome of intra-arterial treatment for basilar artery occlusion. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(10):1225-1230. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang DH, Jung C, Yoon W, et al. . Endovascular thrombectomy for acute basilar artery occlusion: a multicenter retrospective observational study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(14):e009419. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baek JM, Yoon W, Kim SK, et al. . Acute basilar artery occlusion: outcome of mechanical thrombectomy with Solitaire stent within 8 hours of stroke onset. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35(5):989-993. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mokin M, Sonig A, Sivakanthan S, et al. . Clinical and procedural predictors of outcomes from the endovascular treatment of posterior circulation strokes. Stroke. 2016;47(3):782-788. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouslama M, Haussen DC, Aghaebrahim A, et al. . Predictors of good outcome after endovascular therapy for vertebrobasilar occlusion stroke. Stroke. 2017;48(12):3252-3257. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gory B, Eldesouky I, Sivan-Hoffmann R, et al. . Outcomes of stent retriever thrombectomy in basilar artery occlusion: an observational study and systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(5):520-525. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-310250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council . 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association focused update of the 2013 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke regarding endovascular treatment: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015;46(10):3020-3035. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. . Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial: TOAST, Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24(1):35-41. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brott T, Adams HP Jr, Olinger CP, et al. . Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20(7):864-870. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.20.7.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puetz V, Sylaja PN, Coutts SB, et al. . Extent of hypoattenuation on CT angiography source images predicts functional outcome in patients with basilar artery occlusion. Stroke. 2008;39(9):2485-2490. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.511162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19(5):604-607. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.19.5.604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaidat OO, Yoo AJ, Khatri P, et al. ; Cerebral Angiographic Revascularization Grading (CARG) Collaborators; STIR Revascularization working group; STIR Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (TICI) Task Force . Recommendations on angiographic revascularization grading standards for acute ischemic stroke: a consensus statement. Stroke. 2013;44(9):2650-2663. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Kummer R, Broderick JP, Campbell BC, et al. . The Heidelberg bleeding classification: classification of bleeding events after ischemic stroke and reperfusion therapy. Stroke. 2015;46(10):2981-2986. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurth T, Walker AM, Glynn RJ, et al. . Results of multivariable logistic regression, propensity matching, propensity adjustment, and propensity-based weighting under conditions of nonuniform effect. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(3):262-270. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaijser M, Holmin S. Basilar artery occlusion and unwarranted clinical trials. Interv Neuroradiol. 2020;26(1):5-6. doi: 10.1177/1591019919874568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Broderick JP, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM, et al. ; Interventional Management of Stroke (IMS) III Investigators . Endovascular therapy after intravenous t-PA versus t-PA alone for stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):893-903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kidwell CS, Jahan R, Gornbein J, et al. ; MR RESCUE Investigators . A trial of imaging selection and endovascular treatment for ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):914-923. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciccone A, Valvassori L, Nichelatti M, et al. ; SYNTHESIS Expansion Investigators . Endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):904-913. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strbian D, Sairanen T, Silvennoinen H, Salonen O, Kaste M, Lindsberg PJ. Thrombolysis of basilar artery occlusion: impact of baseline ischemia and time. Ann Neurol. 2013;73(6):688-694. doi: 10.1002/ana.23904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saver JL, Jahan R, Levy EI, et al. ; SWIFT Trialists . Solitaire flow restoration device versus the Merci Retriever in patients with acute ischaemic stroke (SWIFT): a randomised, parallel-group, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9849):1241-1249. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61384-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nogueira RG, Lutsep HL, Gupta R, et al. ; TREVO 2 Trialists . Trevo versus Merci retrievers for thrombectomy revascularisation of large vessel occlusions in acute ischaemic stroke (TREVO 2): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9849):1231-1240. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61299-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baik SH, Park HJ, Kim JH, Jang CK, Kim BM, Kim DJ. Mechanical thrombectomy in subtypes of basilar artery occlusion: relationship to recanalization rate and clinical outcome. Radiology. 2019;291(3):730-737. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019181924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gory B, Mazighi M, Blanc R, et al. . Mechanical thrombectomy in basilar artery occlusion: influence of reperfusion on clinical outcome and impact of the first-line strategy (ADAPT vs stent retriever). J Neurosurg. 2018;129(6):1482-1491. doi: 10.3171/2017.7.JNS171043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber R, Minnerup J, Nordmeyer H, et al. ; REVASK investigators . Thrombectomy in posterior circulation stroke: differences in procedures and outcome compared to anterior circulation stroke in the prospective multicentre REVASK registry. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(2):299-305. doi: 10.1111/ene.13809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee WJ, Jung KH, Ryu YJ, et al. . Impact of stroke mechanism in acute basilar occlusion with reperfusion therapy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(3):357-368. doi: 10.1002/acn3.536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Protocol.

eMethods 1. Propensity Matching Score Analysis,

eMethods 2. Treatment method.

eMethods 3. Definition of sICH and aICH.

eTable 1. Ordinal regression model of primary outcome based on PSM dataset including the propensity score as a covariate.

eTable 2. Multivariate regression models of outcomes based on the full dataset including the propensity score as a covariate.

eTable 3. Data elements in the BASILAR cohort study.

eTable 4. Participating centers and eligible patients.

eFigure 1. Consort flow diagram of the BASILAR study.

eFigure 2. Distribution of the BASILAR study centers on the map of China.

eFigure 3. Horizontal stacked bar graphs of mRS outcome by key co-variables in all subjects. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects with age >= 65 years vs. < 65 years. Threshold for age was chosen at the median. EVT denotes endovascular treatment.

eFigure 4. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects stratified by sex.

eFigure 5. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects with stratified by baseline NIHSS ( >= 27 or < 27 ).

eFigure 6. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects with baseline pc-ASPECTS < 8 vs. >= 8.

eFigure 7. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects stratified by TOAST subtype (large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) or cardiac embolism (CE) or other).

eFigure 8. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects stratified by occlusion site (BA distal or BA middle or BA proximal or VA-V4).

eFigure 9. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects stratified by occlusion site (BA middle or non BA middle).

eFigure 10. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects with time from stroke onset to imaging diagnosis (OTI) <= 360 min vs. > 360 min.

eFigure 11. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of all subjects stratified by intravenous thrombolysis (IVT).

eFigure 12. Horizontal stacked bar graphs of mRS outcome by key co-variables in the propensity score matching (PSM) dataset Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset with age >= 65 years vs. < 65 years.

eFigure 13. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset stratified by sex.

eFigure 14. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset with stratified by baseline NIHSS ( >= 26 or < 26 ).

eFigure 15. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset with baseline pc-ASPECTS < 8 vs. >= 8.

eFigure 16. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset stratified by TOAST subtype (large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) or cardiac embolism (CE) or other).

eFigure 17. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset stratified by occlusion site (BA distal or BA middle or BA proximal or VA-V4).

eFigure 18. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset stratified by occlusion site (BA middle or non BA middle).

eFigure 19. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset with time from stroke onset to imaging diagnosis (OTI) <= 360 min vs. > 360 min.

eFigure 20. Distribution of modified Rankin Scale score at 90 days of the patients in the PSM dataset stratified by intravenous thrombolysis (IVT).

eReferences.