This cross-sectional study of 6147 English olderadults examines associations between concurrent multisensory impairments and aspects of well-being and mental health.

Key Points

Question

Are impairments in multiple senses associated with quality of life and depression?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of a representative sample of 6147 English adults 52 years and older, reporting a greater number of sensory impairments was strongly and linearly associated with lower quality of life and increased risk of depressive symptoms. The associations were mainly driven by impairment in hearing, vision, and taste but not smell, and they tended to be stronger in individuals younger than 65 years compared with older individuals.

Meaning

Preventing sensory impairments may reduce the risks of poor well-being, potentially increasing the chances of independent living.

Abstract

Importance

Sensory acuity tends to decrease with age, but little is known about the relationship between having multiple sensory impairments and well-being in later life.

Objective

To examine associations between concurrent multisensory impairments and aspects of well-being and mental health, namely quality of life and depressive symptoms.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Cross-sectional analysis of participants in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging wave 8 (May 2016 to June 2017). This is a representative sample of free-living English individuals 52 years and older. Analysis began April 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Linear and logistic regression models were used to assess the association of self-reported concurrent impairments in hearing, vision, smell, and taste with quality of life (0-57 on the 19-item CASP-19 scale; Control, Autonomy, Self-realization and Pleasure) and depressive symptoms (≥4 items on the 8-item Centre for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale).

Results

Using a representative sample of 6147 individuals, 52% (weighted) were women (n = 3455; unweighted, 56%) and the mean (95% CI) age was 66.6 (66.2-67.0) years. Multiple sensory impairments were associated with poorer quality of life and greater odds of depressive symptoms after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, chronic conditions, and cognitive function. Compared with no sensory impairment, quality of life decreased linearly as the number of senses impaired increased, with individuals reporting 3 to 4 sensory impairments displaying the poorest quality of life (−4.68; 95% CI, −6.13 to −3.23 points on the CASP-19 scale). Similarly, odds of depressive symptoms increased linearly as the number of impairments increased. Individuals with 3 to 4 senses impaired had more than a 3-fold risk of depressive symptoms (odds ratio, 3.36; 95% CI, 2.28-4.96).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study, concurrent sensory impairments were associated with poorer quality of life and increased risks of depressive symptoms. Therefore, assessing and managing sensory impairments could help improve older adults’ well-being.

Introduction

In many countries including England, the population is aging.1,2 Sensory impairments are common in later life. In particular, hearing impairment is estimated to affect 22% of English adults aged 50 to 80 years, a figure that increases to 55% in those 75 years and older,3 and vision impairment affects 12% of English adults 60 years and older.4 The prevalence of other sensory impairments such as taste, smell, or touch in older English adults is unknown.5 However, in the United States, smell impairment affects 25% of adults aged 53 to 97 years,6 and taste impairment affects 15% of US adults aged 57 to 85 years.7

A poor sensory function can cause wide-ranging problems for the individual, including reduced ability to undertake everyday activities8,9; increased risks of frailty,10,11 dementia,12,13 and depression14,15; and reduced quality of life.16,17 While most previous research has focused on a single sensory impairment, fewer studies have examined relationships of combined sensory impairments, including dual sensory impairments (most commonly combined hearing and vision impairment) with adverse health and well-being in older age. Existing research includes evidence of relationships between dual sensory impairments and symptoms of depression,18 cognitive impairment,19 poorer quality of life,20 and loneliness.21 Two of these studies did not find interactions between sensory impairments with age,18,19 whereas 1 study suggested that advanced age (≥80 years) might influence the associations between dual sensory impairments and quality of life.20 Moreover, having more than 1 sensory impairment has been shown to have worse consequences for health compared with a single sensory impairment.20,22 Therefore, experiencing impairment in more than 2 senses may cause even more detrimental health effects.23 However, apart from hearing and vision, concurrent impairments in the other senses have been little studied. One study has shown associations between combined impairments of hearing, vision, and smell (olfactory impairment) with poorer cognitive performance in the general population.24 Another reports associations between concurrent multisensory impairments (hearing, vision, smell, taste, and touch) and difficulty performing everyday activities, worse cognitive function, and lower overall health.25 Nevertheless, to our knowledge, there is no evidence of relationships between multisensory impairment and aspects of mental health and well-being such as symptoms of depression and quality of life.

Depression is common in older age, estimated to affect 22% of men and 28% of women 65 years and older.26 Quality of life refers to multiple aspects of functioning, including perceived sense of control, autonomy, self-realization, and pleasure in life.27 Research has shown that maintaining mental health and well-being is important to remain independent in later life.28

Therefore, this study aims to examine the association of self-rated multisensory impairments (concurrent impairments in vision, hearing, smell, and taste) with quality of life and depressive symptoms in older age. This will clarify whether multisensory impairments have a linear, synergistic (the total association is greater than the sum of the individual associations), or asymptotic (ceiling effect) association with quality of life and depressive symptoms. A secondary aim is to examine each of the 4 sensory impairments individually to assess if the associations are driven by 1 particular sense and to examine the role of loneliness as potential key mediator. Finally, we aim to explore whether the age at which sensory impairment is assessed can modify the association of sensory impairments and well-being.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional study uses data from the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSA), an ongoing nationally representative cohort of community-dwelling adults 52 years and older.29 Every 2 years since 2002 (wave 1), a face-to-face interview is conducted and a self-completion questionnaire is also administered. The present study uses data from May 2016 to June 2017 (wave 8), the most recent data collection available. Participants with complete data on hearing, vision, taste, smell, quality of life, depressive symptoms, and covariates in 2016 to 2017 were included in the analyses. Ethical approval was obtained through the National Research Ethics Service (London Multicenter Research Ethics Committee MREC/01/2/91) and all participants provided written informed consent.

Exposure Variables

Each sensory impairment was measured using a self-reported question asking participants to rate each sense on a 5-item Likert-type scale as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. Hearing aids and glasses/corrective lenses were taken into consideration. For hearing, participants were asked to rate their hearing ability using a hearing aid if they use one. This question has previously been demonstrated to be accurate when compared with objectively measured hearing.30 Vision referred to the participant’s eyesight with glasses or corrective lenses if they normally used them, and this item has been correlated with objectively measured eyesight.31 For each of the 4 senses (hearing, vision, smell, and taste) reporting excellent, very good, or good were reclassified as having no self-rated impairment in hearing, vision, smell, and taste. Participants reporting fair or poor were considered having a self-rated impairment in that particular sense.

Data on each of the 4 senses were combined, providing a score ranging from 0 to 4 representing the number of senses impaired. For all analyses, the reference category was the group of respondents with a score of 0 (no sensory impairment).

Outcome Variables

Quality of life was assessed in the self-completion questionnaire using the validated 19-item CASP-19 scale (Control, Autonomy, Self-realization and Pleasure), which conceptualizes self-perceived quality of life as the extent to which needs are satisfied, eg, being able to do things that you want to do.32 Each of the 19 items has 4 answer options (never, not often, often, and sometimes providing 0 to 3 points per question), generating a summary score of 0 to 57, where higher scores indicated higher satisfaction regarding the quality of life. For the analyses, the score was treated as a continuous variable.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the validated 8-item version of the Centre for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale. The occurrence of 4 or more of the 8 items was defined as having depressive symptoms, which is equivalent to the conventional threshold of 16 or higher on the full 20-item Centre for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale.33

Covariates

Covariates included age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, wealth, smoking status, cognitive function, and 4 physician-diagnosed comorbidities (self-reported): coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer, previously associated with sensory impairments.23,25 Wealth was divided in quintiles of total net nonpension wealth of the household; ethnicity into white and nonwhite (ie, black, Asian, mixed/other group); marital status into living with a partner or not; and smoking status into never, former, or current smoker. Cognitive function spanned 2 domains: executive functioning and memory. Executive functioning was measured by the participant’s ability to name as many specific categories of animals as possible in 1 minute, resulting in a score ranging 0 (0 animals) to 9 (≥30 animals) points.29 Memory was assessed by asking the participant to repeat 10 words presented on a computer immediately and again after 5-minute delay (10 + 10 points), resulting in a score 0 to 20 points. Higher scores reflect better cognitive function. Loneliness was assessed by a single question, “How often do you feel lonely?” with 3 possible answers: never/rarely, sometimes, and often.

Statistical Analyses

Pearson correlations between all the impaired senses were calculated. Generalized linear models were used to examine associations between concurrent multisensory impairment and the outcome measure quality of life; logistic regression was used to examine associations with depressive symptoms. Models were weighted to account for nonresponse using self-completion weights. Model 1 included age and sex as covariates, and model 2 further included ethnicity, marital status, wealth, smoking status, cognitive function, and 4 physician-diagnosed comorbidities. In the analysis where the outcome was quality of life, we investigated a model 3 that included loneliness as a potential mediator lying on the pathway between sensory impairment and quality of life. The contribution of loneliness to explain the association was determined by the percent attenuation in the β coefficient for sensory impairment after inclusion of loneliness to model 2: 100 × (β for model 3 – β for model 2) / (β for model 2). Loneliness is one of the depressive symptoms in the Centre for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale; therefore, analyses with depressive symptoms only involved models 1 and 2. For the main analysis, participants presenting 3 or 4 sensory impairments were grouped together owing to low numbers of people with all 4 senses impaired. To test whether the associations were additive or synergistic, contrast tests of linear, quadratic, and cubic trend were used across the 4 categories (0, 1, 2, and 3-4 senses impaired). In a sensitivity analysis, we used the 5 categories (0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 senses impaired). As a second sensitivity analysis, we used a structural equation modeling approach to assess mediation in the association between sensory impairment and quality of life, including simultaneously 2 potential mediators: loneliness and cognitive function (a composite score ranging 0-29, sum of the memory and executive function scores) and allowing cognitive function as a predictor of loneliness, as well as adjusting for all covariates. The percentage of mediation through loneliness and through cognition were calculated as the ratio of indirect association over total association.

We tested for interactions of multisensory impairment with age using the likelihood ratio tests between nested models. Stratified analyses were undertaken in younger (aged 52-64 years) and older participants (aged ≥65 years). In addition, associations between impairments in each of the 4 sensory functions (vision, hearing, taste, and smell) and the 2 outcome measures (quality of life and depressive symptoms) were examined to investigate if such associations were driven by a particular sensory impairment or if there was a cumulative and similar association with each sense. This was done in separate models but also in a model where all 4 senses were included together (mutually adjusted model). All analyses were performed using Stata, version 14 (StataCorp). A 2-sided P value of .05 was statistically significant. Analysis began April 2018.

Results

Of 7223 core members at wave 8 of ELSA, 966 did not respond to the self-completion questionnaire; therefore, 6257 had self-completion weights used to account for nonresponse in the analysis. There were 6147 participants with data on all covariates and depressive symptoms, and 5692 had valid data on the CASP-19 questionnaire and loneliness. Weighted percentages and means presented in Table 1 show that after correction, the sample comprised 52% women, and the mean (95% CI) age was 66.6 (66.2-67.0) years. Weighted prevalence of self-reported sensory impairment was 22% for hearing, 13% for vision, 13% for smell, and 7% for taste; 62% of the participants had no sense impaired, 25% had 1 sense impaired, 9% had 2 senses impaired, 3% had 3 senses impaired, and 1% (not weighted n = 49) had 4 sensory impairments. The correlations between different sensory impairments were low (ranging from r = 0.08 to 0.15), except for taste and smell with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.44.

Table 1. Sample Characteristics of 6147 English Adults 52 Years and Older.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Weighted %a |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 6147 (100) | NA |

| Exposure measures | ||

| No. of senses impaired | ||

| 0 | 3763 (61) | 62 |

| 1 | 1557 (25) | 25 |

| 2 | 603 (10) | 9 |

| 3 | 175 (3) | 3 |

| 4 | 49 (1) | 1 |

| Prevalence of each sensory impairment | ||

| Hearing | 1385 (23) | 22 |

| Vision | 768 (12) | 13 |

| Smell | 879 (14) | 13 |

| Taste | 452 (7) | 7 |

| Outcome measures | ||

| Quality of life (CASP-19)b | 41.7 (8.8)c | 41.2 (40.8-41.5)d |

| Depressive symptoms (≥4 CES-D8) | 765 (12) | 14 |

| Covariates | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 69.9 (8.7) | 66.6 (66.2-67.0)d |

| Age, 52-64 y | 1779 (29) | 47 |

| Age, ≥65 y | 4368 (71) | 53 |

| Female | 3455 (56) | 52 |

| White | 5977 (97) | 95 |

| Living with a partner | 4183 (68) | 70 |

| Wealth in quintiles | ||

| 1 (lowest) | 958 (15) | 20 |

| 2 | 1155 (19) | 20 |

| 3 | 1294 (21) | 20 |

| 4 | 1350 (22) | 20 |

| 5 (highest) | 1390 (23) | 20 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current | 542 (9) | 11 |

| Previous | 3472 (56) | 62 |

| Never | 2133 (35) | 27 |

| Diagnosed | ||

| Coronary heart disease | 472 (8) | 7 |

| Stroke | 333 (5) | 5 |

| Diabetes | 805 (13) | 13 |

| Cancer | 425 (7) | 6 |

| Cognitive function | ||

| Memory score | 10.7 (3.6)c | 10.8 (10.6-10.9)d |

| Executive function score | 6.1 (2.2)c | 6.1 (6.0-6.2)d |

| Loneliness feelinge | ||

| Hardly ever or never | 4284 (70) | 68 |

| Some of the time | 1414 (23) | 25 |

| Often | 388 (6) | 7 |

Abbreviations: CASP-19, Control, Autonomy, Self-realization and Pleasure 19-item scale; CES-D8, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (8 items); NA, not applicable.

Means and percentages are weighted for nonresponse to the self-completion questionnaire.

n = 5707.

Reported as mean (SD).

Reported as mean (95% CI).

n = 6086.

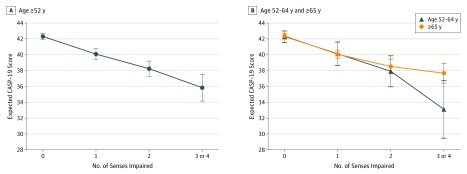

Concurrent Multisensory Impairment and Quality of Life

Findings presented in Table 2 and the Figure show that the greater the number of sensory impairments, the poorer the quality of life, and this decrease was linear (P value for linear trend < .001). Individuals reporting 3 to 4 sensory impairments had the poorest quality of life scoring −4.68 (95% CI, −6.13 to −3.23) fewer points on the CASP-19 scale compared with individuals with no sense impaired, adjusted for sociodemographic factors (age, sex, ethnicity, wealth, marital status), smoking, comorbidities (coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer), and cognitive function. After inclusion of loneliness in the model, all estimates were attenuated but remained significant. The coefficient associated with 3 to 4 sensory impairments was attenuated by 28%, meaning that 28% of the association can be explained by loneliness. Using a structural equation model including both loneliness and cognition, the percentage of association mediated by loneliness was 27% and by cognition was 2% (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). An interaction was found between the number of impairments and age associated with quality of life (P for interaction < .001). In stratified analyses, having 1 or more sensory impairments was negatively associated with lower quality of life in both younger (aged 52-64 years) and older participants (aged ≥65 years), but the magnitude was greater in the younger group (Table 2 and the Figure). Moreover, while the trend was linear in the younger group, it tended to plateau in the older group (quadratic trend P = .10). The stronger association observed in the younger sample was more mediated by loneliness (45%) than in the older sample (10%). These results were more apparent, even if precision was lower when 3 and 4 senses impaired were considered as 2 distinct categories (eTable 1 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Findings presented in Table 3 show that all sensory impairments were individually associated with poorer quality of life, in particular vision and taste. When included together in the same model, smell impairment was not significantly associated with quality of life. Considering that impaired smell can affect taste, as shown by the moderately high correlation between smell and taste impairment, the association between smell impairment and quality of life is likely driven by the association with taste impairment.

Table 2. Associations From the Generalized Linear Model Between the Number of Impaired Senses and Quality of Life (Control, Autonomy, Self-realization and Pleasure 19-Item Scale) in 5692 English Adults Aged 52 Years and Older.

| Model | No. of Impaired Senses, β (95% CI)a | P Value for Trend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1 | 2 | 3 or 4 | Linear | Quadratic | Cubic | |

| Overall, No. (n = 5692) | 3531 | 1423 | 537 | 201 | NA | NA | NA |

| Model 1b | [Reference] | −3.06 (−3.95 to −2.16) | −5.56 (−6.71 to −4.40) | −8.93 (−10.76 to −7.11) | <.001 | .78 | .51 |

| Model 2c | [Reference] | −2.24 (−3.05 to −1.42) | −4.07 (−5.12 to −3.02) | −6.47 (−8.22 to −4.73) | <.001 | .88 | .62 |

| Model 3d | [Reference] | −1.80 (−2.51 to −1.10) | −3.25 (−4.10 to −2.40) | −4.68 (−6.13 to −3.23) | <.001 | .67 | .83 |

| Age 52-64 y, No. (n = 1721)e | 1227 | 325 | 122 | 47 | NA | NA | NA |

| Model 1b | [Reference] | −2.77 (−4.58 to −0.96) | −6.34 (−8.64 to −4.04) | −12.82 (−16.43 to −9.22) | <.001 | .11 | .64 |

| Model 2c | [Reference] | −2.22 (−3.83 to −0.62) | −4.31 (−6.38 to −2.23) | −8.99 (−12.67 to −5.32) | <.001 | .27 | .49 |

| Model 3d | [Reference] | −1.41 (−2.78 to −0.04) | −3.42 (−4.95 to −1.89) | −4.94 (−8.07 to −1.81) | <.001 | .67 | .83 |

| Age ≥65 y, No. (n = 3971)e | 2304 | 1098 | 415 | 154 | NA | NA | NA |

| Model 1b | [Reference] | −2.95 (−3.60 to −2.29) | −4.72 (−5.77 to −3.68) | −5.85 (−7.26 to −4.45) | <.001 | .05 | .78 |

| Model 2c | [Reference] | −2.25 (−2.87 to −1.64) | −3.73 (−4.73 to −2.73) | −4.61 (−5.94 to −3.28) | <.001 | .11 | .92 |

| Model 3d | [Reference] | −2.08 (−2.64 to −1.52) | −3.11 (−4.00 to −2.21) | −4.14 (−5.39 to −2.89) | <.001 | .19 | .51 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Values are unstandardized regression coefficients.

Model 1: age (continuous) and sex.

Model 2: age, sex, ethnicity (white, nonwhite), marital status (cohabiting, not cohabiting), wealth (quintiles), smoking status (current, former, never smoker), cognitive function (memory score and executive function score, continuous), and physician-diagnosed diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer (yes/no).

Model 3: model 2 + loneliness.

P value for interaction between number of impaired senses and age (continuous) P < .001.

Figure. Adjusted Expected Values of Quality of Life Score by the Number of Senses Impaired in 5692 English Adults.

The adjusted model 2 used the Control, Autonomy, Self-realization and Pleasure 19-item scale and included age, sex, ethnicity (white, nonwhite), marital status (cohabiting, not cohabiting), wealth (quintiles), smoking status (current, former, never smoker), cognitive function (memory score and executive function score, continuous), and physician-diagnosed diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer (yes/no).

Table 3. Multivariable Estimates From Generalized Linear Models of the Association Between Impaired Sense and Quality of Life and Depressive Symptoms.

| Model | Individual Sensory Impairments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing | Vision | Taste | Smell | |

| Quality of Life, β (95% CI)a | ||||

| Separate models | ||||

| Model 1b | −3.58 (−4.50 to −2.66) | −6.17 (−7.15 to −5.18) | −5.60 (−7.02 to −4.18) | −2.30 (−3.39 to −1.20) |

| Model 2c | −2.75 (−3.60 to −1.90) | −3.79 (−4.73 to −2.84) | −4.31 (−5.52 to −3.10) | −1.77 (−2.69 to −0.84) |

| Model 3d | −1.93 (−2.65 to −1.20) | −2.88 (−3.68 to −2.09) | −3.44 (−4.35 to −2.53) | −1.51 (−2.27 to −0.74) |

| Mutually adjusted | ||||

| Model 1b | −2.60 (−3.53 to −1.67) | −5.27 (−6.24 to −4.30) | −4.05 (−5.58 to −2.51) | −0.17 (−1.28 to 0.93) |

| Model 2c | −2.16 (−3.01 to −1.31) | −3.14 (−4.06 to −2.22) | −3.33 (−4.69 to −1.97) | −0.19 (−1.18 to 0.80) |

| Model 3d | −1.47 (−2.20 to −0.73) | −2.41 (−3.20 to −1.62) | −2.66 (−3.74 to −1.58) | −0.30 (−1.15 to 0.55) |

| Depressive Symptoms, Odds Ratio (95% CI)e | ||||

| Separate models | ||||

| Model 1b | 2.18 (1.72 to 2.75) | 2.86 (2.26 to 3.63) | 2.29 (1.69 to 3.09) | 1.46 (1.11 to 1.91) |

| Model 2c | 1.91 (1.51 to 2.42) | 1.84 (1.43 to 2.38) | 1.79 (1.33 to 2.41) | 1.26 (0.95 to 1.67) |

| Mutually adjusted | ||||

| Model 1b | 1.83 (1.43 to 2.34) | 2.44 (1.91 to 3.10) | 1.75 (1.22 to 2.53) | 0.98 (0.71 to 1.36) |

| Model 2c | 1.74 (1.37 to 2.23) | 1.64 (1.27 to 2.13) | 1.55 (1.09 to 2.21) | 0.94 (0.67 to 1.30) |

Values are unstandardized regression coefficients compared with no impairment (reference category). The Control, Autonomy, Self-realization and Pleasure 19-item scale was used.

Model 1: age (continuous) and sex.

Model 2: age, sex, ethnicity (white, nonwhite), marital status (cohabiting, not cohabiting), wealth (quintiles), smoking status (current, former, never smoker), cognitive function (memory score and executive function score, continuous), and physician-diagnosed diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer (yes/no).

Model 3: model 2 + loneliness.

Values are odds ratios compared with no impairment (reference category). Four or more of the 8-item Centre for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale was used to define presence of depressive symptoms.

Concurrent Multisensory Impairment and Depressive Symptoms

Reporting a greater number of impaired senses was associated with higher odds of depressive symptoms and the trend was linear, but the cubic trend was borderline significant (P = .07), reflected by odds ratios (ORs) of same magnitude for 1 (1.66; 95% CI, 1.30-2.12) and for 2 (1.78; 95% CI, 1.26-2.51) senses impaired but much greater for 3 or 4 senses impaired (Table 4). However, the trend was more clearly linear when separating 3 and 4 senses impaired (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Participants with 3 or 4 impaired senses had more than 3-fold risks of experiencing depressive symptoms (OR, 3.36; 95% CI, 2.28-4.96). There was a marginal interaction with age (P for interaction = .10). The OR for depressive symptoms associated with having 3 or 4 senses impaired was greater in younger than in older individuals. As seen in Table 3, hearing, vision, and taste impairment displayed significant associations with depressive symptoms of similar magnitude (ranging from 55% to 74% greater odds in mutually adjusted model), whereas the association with smell impairment was nonsignificant (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.67-1.30).

Table 4. Multivariable Odds Ratios and 95% CI of the Associations Between the Number of Impaired Senses and Depressive Symptoms in 6147 English Adults 52 Years and Oldera.

| Model | No. of Impaired Senses, Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value for Trend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1 | 2 | 3 or 4 | Linear | Quadratic | Cubic | |

| Overall, No. (n = 6147) | 3763 | 1557 | 603 | 224 | |||

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 1.93 (1.51-2.47) | 2.45 (1.79-3.35) | 5.33 (3.60-7.89) | <.001 | .64 | .07 |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 1.66 (1.30-2.12) | 1.78 (1.26-2.51) | 3.36 (2.28-4.96) | <.001 | .62 | .07 |

| Age 52-64 y, No. (n = 1779)d | 1271 | 333 | 127 | 48 | |||

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 1.87 (1.18-2.96) | 2.81 (1.57-5.05) | 9.88 (4.60-21.23) | <.001 | .21 | .32 |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 1.60 (1.00-2.57) | 1.86 (0.92-3.73) | 4.89 (2.26-10.60) | <.001 | .36 | .34 |

| Age ≥65 y, No. (n = 4368)d | 2492 | 1224 | 476 | 176 | |||

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 1.89 (1.50-2.39) | 2.11 (1.54-2.90) | 3.33 (2.20-5.04) | <.001 | .50 | .11 |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 1.68 (1.33-2.12) | 1.72 (1.23-2.40) | 2.61 (1.70-4.03) | <.001 | .72 | .11 |

Four or more of the 8-item Centre for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale was used to define presence of depressive symptoms.

Model 1: age (continuous) and sex.

Model 2: age, sex, ethnicity (white, nonwhite), marital status (cohabiting, not cohabiting), wealth (quintiles), smoking status (current, former, never smoker), cognitive function (memory score and executive function score, continuous), physician-diagnosed diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer (yes/no).

P value for interaction between the number of impaired senses and age (continuous) P = .10.

Discussion

In this study of 6147 community-dwelling English adults 52 years and older, we found that reporting a greater number of sensory impairments is strongly and linearly associated with lower quality of life and increased risk of depressive symptoms. The associations were mainly driven by impairment in hearing, vision, taste, but not smell, and they tended to be stronger in individuals younger than 65 years compared with individuals 65 and older.

We report a prevalence of impairments in hearing (22%) and vision (13%) in English adults 52 years and older similar to previous national estimates using objective measures.3,4 Internationally, estimates of smell impairment and taste impairment in the general population range from 3% to 25% and 1% to 20%, respectively.34 The wide variation is likely to be explained by how the sensory functions were assessed, the threshold used to define impairment, and the characteristics of the sample. Such characteristics include the population’s age, which is important as sensory functions decline with advanced age,3,23,31 in particular hearing but less so taste.23 Little is known about the prevalence of impairments in smell and taste in the older English population.5 In our study, the prevalence of impairments in smell (15%) and taste (7%) were lower than objectively assessed in US adults older than 50 years (25% and 15%, respectively).6,7 It is likely that self-reported sensory impairments can be subject to underreporting of loss because of unawareness or denial.35 The prevalence reported in our study are therefore likely to be underestimated.

This study adds to current literature, as it is the first population-based study to examine concurrent multisensory impairment and the number of impairments associated with mental health and well-being, to our knowledge. Previous research has shown an association between concurrent hearing, vision, and smell impairments and worse cognitive function; however, that study did not include taste and was undertaken in the general population rather than the aging population.24 In 1 study, concurrent impairments in hearing, vision, smell, taste, and touch have been associated with difficulty performing everyday activities, worse cognitive function and lower overall health in community-dwelling adults aged 57 to 85 years.25 However, aspects of mental health and well-being were not assessed. Studies examining dual sensory impairment (hearing and vision) in older adults have demonstrated that in comparison with having none or 1, having 2 sensory deficits is associated with higher risk of depression36 and poor quality of life.37 To our knowledge, our study is the first to find that self-reported sensory impairments are associated with poorer quality of life and greater risks of depressive symptoms in a dose-response fashion. Moreover, we found that sensory impairments occurring earlier in late-adult life (before 65 years) were associated more strongly with worse well-being. Various mechanisms can explain this. Younger individuals are more likely to work, where sensory impairments can be a great disadvantage in performing certain tasks; sensory impairments can be perceived as aging signs, which can have a strong effect on an individual’s morale. Conversely, at older age, sensory impairment is more likely to be perceived as part of the aging process, and individuals may be less affected by it. An implication of this finding is that if left untreated at early old age, a sensory impairment may have detrimental long-term consequences on quality of life. Taking the example of hearing, knowing that more than 60% of people with hearing impairment in the United Kingdom do not use hearing aids,38 despite being covered by the National Health Service, emphasis should be put in detecting and treating hearing loss as early as possible.

Impairments in hearing, vision, and smell have previously been associated with reduced social interaction, social isolation, and loneliness,21,39,40 which in turn is a strong determinant of poorer quality of life. We found that loneliness explained a substantial part, but not all, of the association. It appears then that sensory impairments can influence directly the quality of life by affecting sense of control over one’s life, future prospects, or sense of enjoyment. Sensory impairments can be preventable on their own or at least their onset delayed.41 Therefore, addressing sensory impairments, in particular hearing, vision, and taste, might help to alleviate loneliness and maintain positive well-being in later life by not restricting participation, which in turn can help decrease the risk of future cognitive impairment and functional dependence. Our results are in the scope of the International Classification of Function, Disability and Health framework42 and add to the body of research that links impairment in body structures or functions with limitations in activities and restriction in social participation.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is that data are from a nationally representative cohort of community-dwelling English women and men 52 years and older. To our knowledge, it is the first study to explore associations between concurrent multisensory impairments and mental health and quality of life. The measures of the assessed outcomes (quality of life and depressive symptoms) have been validated,32,33 and a wide range of potential confounders were considered.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, ELSA participants with incomplete data on the variables relevant to this study were excluded from the analyses. Nonrespondents were younger, more likely to be in the lower wealth quintiles, and to be smokers compared with respondents, which raises the issue of selection bias; however, we intended to overcome this limitation by applying weights for nonresponse to the regression models to remain representative of the overall ELSA sample. Second, this is a cross-sectional study using data from the latest wave of ELSA (wave 8, 2016-2017), which was the first time questions on taste and smell were asked. Owing to the cross-sectional design of the study, causality and directionality cannot be established. It also remains unclear whether the associations observed in the current study are direct or indirect. Cognitive function, previously associated with sensory impairments,19,25 might be linking multisensory impairments with depression and quality of life, in particular because sensory impairment was self-rated. In our study, cognitive function did not attenuate the associations observed; however, this may be explained by unmeasured aspects of cognition, eg, problem-solving tasks not part of the cognitive tests. Although we adjusted for several potential confounders, there may be other influential yet unmeasured confounders not available in ELSA such as anxiety. Third, data on the sense of touch have not been collected in ELSA, resulting in our study being restricted to analyses of the remaining 4 senses. Fourth, data on the 4 senses included were self-reported rather than objectively assessed. Finally, the sample comprised mostly of white English adults 52 years and older, and the findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study shows that self-reported concurrent multisensory impairments are additively associated with poorer quality of life and depressive symptoms in adults 52 years and older. These findings are of public health importance as sensory impairments, poor quality of life, and depressive symptoms affect a large number of individuals in older age, and this number is likely to increase as the aging population is rapidly growing. Preventing sensory impairments could reduce the risks of poor well-being, potentially increasing the chances of independent living. However, prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings.

eTable 1. Associations from generalized linear model between the number of impaired senses and quality of life (CASP-19) separating the group of participants with three and with four senses impaired, in 5692 English adults aged 52 years and over, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing 2016-2017

eTable 2. Multivariable odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of the associations between the number of impaired senses and depressive symptoms (≥4 of the 8-item CES-D) separating the group of participants with three and with four senses impaired in 6147 English adults aged 52 years and over, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing 2016-2017

eFigure 1. Structural equation model for the assessment of mediation by loneliness and cognitive function

eFigure 2. Adjusted (Model 2) expected values of quality of life (CASP-19) score by number of senses impaired in 5692 English adults aged 52 years and over (Panel A), and separately for age 52-64y and age ≥65y (Panel B), the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing 2016-2017

References

- 1.World Report on Ageing and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/186463/1/9789240694811_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed December 19, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office for National Statistics National population projections: 2016-based statistical bulletin. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationprojections/bulletins/nationalpopulationprojections/2016basedstatisticalbulletin#a-growing-number-of-older-people. Accessed December 19, 2019.

- 3.Action on Hearing Loss Facts and figures. hhttps://www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/about-us/our-research-and-evidence/facts-and-figures/. Accessed January 3, 2020.

- 4.Sight Loss UK 2013: The Latest Evidence. London, UK: Royal National Institute of Blind People; 2013. https://www.rnib.org.uk/sites/default/files/Sight_loss_UK_2013.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fifth Sense http://www.fifthsense.org.uk/. Accessed December 19, 2019.

- 6.Murphy C, Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Nondahl DM. Prevalence of olfactory impairment in older adults. JAMA. 2002;288(18):2307-2312. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boesveldt S, Lindau ST, McClintock MK, Hummel T, Lundstrom JN. Gustatory and olfactory dysfunction in older adults: a national probability study. Rhinology. 2011;49(3):324-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liljas AEM, Wannamethee SG, Whincup PH, et al. Hearing impairment and incident disability and all-cause mortality in older British community-dwelling men. Age Ageing. 2016;45(5):662-667. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones N, Bartlett HE, Cooke R. An analysis of the impact of visual impairment on activities of daily living and vision-related quality of life in a visually impaired adult population. Br J Vis Impairment. 2018;37(1):50-63. doi: 10.1177/0264619618814071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liljas AEM, Carvalho LA, Papachristou E, et al. Self-reported vision impairment and incident prefrailty and frailty in English community-dwelling older adults: findings from a 4-year follow-up study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(11):1053-1058. doi: 10.1136/jech-2017-209207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liljas AEM, Carvalho LA, Papachristou E, et al. Self-reported hearing impairment and incident frailty in English community-dwelling older adults: a 4-year follow-up study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):958-965. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies HR, Cadar D, Herbert A, Orrell M, Steptoe A. Hearing impairment and incident dementia: findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(9):2074-2081. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts RO, Christianson TJ, Kremers WK, et al. Association between olfactory dysfunction and amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(1):93-101. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.2952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hur K, Choi JS, Zheng M, Shen J, Wrobel B. Association of alterations in smell and taste with depression in older adults. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2018;3(2):94-99. doi: 10.1002/lio2.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu A, Liljas AEM. The relationship between self-reported sensory impairments and psychosocial health in older adults: a 4-year follow-up study using the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Public Health. 2019;169:140-148. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hummel T, Nordin S. Olfactory disorders and their consequences for quality of life. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125(2):116-121. doi: 10.1080/00016480410022787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer ME, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Schubert CR, Wiley TL. Multiple sensory impairment and quality of life. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2009;16(6):346-353. doi: 10.3109/09286580903312236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cosh S, von Hanno T, Helmer C, Bertelsen G, Delcourt C, Schirmer H; SENSE-Cog Group . The association amongst visual, hearing, and dual sensory loss with depression and anxiety over 6 years: the Tromsø Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(4):598-605. doi: 10.1002/gps.4827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liljas AEM, Walters K, de Oliveira C, Wannamethee SG, Ramsay SE, Carvalho LA. Self-reported sensory impairments and changes in cognitive performance: a longitudinal 6-year follow-up study of English community-dwelling adults aged ⩾50 years. J Aging Health. 2018:898264318815391. doi: 10.1177/0898264318815391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng YC, Liu SH, Lou MF, Huang GS. Quality of life in older adults with sensory impairments: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(8):1957-1971. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1799-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viljanen A, Törmäkangas T, Vestergaard S, Andersen-Ranberg K. Dual sensory loss and social participation in older Europeans. Eur J Ageing. 2014;11:155-167. doi: 10.1007/s10433-013-0291-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider JM, Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Leeder SR, Mitchell P, Wang JJ. Dual sensory impairment in older age. J Aging Health. 2011;23(8):1309-1324. doi: 10.1177/0898264311408418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Correia C, Lopez KJ, Wroblewski KE, et al. Global sensory impairment in older adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):306-313. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Fischer ME, et al. Sensory impairments and cognitive function in middle-aged adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(8):1087-1090. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinto JM, Wroblewski KE, Huisingh-Scheetz M, et al. Global sensory impairment predicts morbidity and mortality in older US adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(12):2587-2595. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Health Service Health survey for England: 2005, health of older people. Published March 23, 2007. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/health-survey-for-england-2005-health-of-older-people. Accessed December 19, 2019.

- 27.Nussbaum M, Sen A. The Quality of Life. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1993. doi: 10.1093/0198287976.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet. 2015;385(9968):640-648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.UK Data Service. English longitudinal study of ageing: waves 0-8, 1998-2017. https://beta.ukdataservice.ac.uk/datacatalogue/studies/study?id=5050. Accessed December 19, 2019.

- 30.Ferrite S, Santana VS, Marshall SW. Validity of self-reported hearing loss in adults: performance of three single questions. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45(5):824-830. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102011005000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimdars A, Nazroo J, Gjonca E. The circumstances of older people in England with self-reported visual impairment: a secondary analysis of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). Br J Vis Impairment. 2012;30:22-30. doi: 10.1177/0264619611427374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hyde M, Wiggins RD, Higgs P, Blane DB. A measure of quality of life in early old age: the theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging Ment Health. 2003;7(3):186-194. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000101157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steffick DE. Documentation of affective functioning measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Arbor, MI. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/dr-005.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu G, Zong G, Doty RL, Sun Q. Prevalence and risk factors of taste and smell impairment in a nationwide representative sample of the US population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e013246. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liljas AE, Wannamethee SG, Whincup PH, et al. Sensory impairments and cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality in older British community-dwelling men: a 10-year follow-up study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):442-444. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guthrie DM, Declercq A, Finne-Soveri H, Fries BE, Hirdes JP. The health and well-being of older adults with dual sensory impairment (DSI) in four countries. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chia EM, Mitchell P, Rochtchina E, Foran S, Golding M, Wang JJ. Association between vision and hearing impairments and their combined effects on quality of life. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(10):1465-1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scholes S, Biddulph J, Davis A, Mindell JS. Socioeconomic differences in hearing among middle-aged and older adults: cross-sectional analyses using the Health Survey for England. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e019615. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mick P, Parfyonov M, Wittich W, Phillips N, Guthrie D, Kathleen Pichora-Fuller M. Associations between sensory loss and social networks, participation, support, and loneliness: analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(1):e33-e41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sivam A, Wroblewski KE, Alkorta-Aranburu G, et al. Olfactory dysfunction in older adults is associated with feelings of depression and loneliness. Chem Senses. 2016;41(4):293-299. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjv088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saunders GH, Echt KV. An overview of dual sensory impairment in older adults: perspectives for rehabilitation. Trends Amplif. 2007;11(4):243-258. doi: 10.1177/1084713807308365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.WHO International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/. Accessed December 19, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Associations from generalized linear model between the number of impaired senses and quality of life (CASP-19) separating the group of participants with three and with four senses impaired, in 5692 English adults aged 52 years and over, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing 2016-2017

eTable 2. Multivariable odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of the associations between the number of impaired senses and depressive symptoms (≥4 of the 8-item CES-D) separating the group of participants with three and with four senses impaired in 6147 English adults aged 52 years and over, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing 2016-2017

eFigure 1. Structural equation model for the assessment of mediation by loneliness and cognitive function

eFigure 2. Adjusted (Model 2) expected values of quality of life (CASP-19) score by number of senses impaired in 5692 English adults aged 52 years and over (Panel A), and separately for age 52-64y and age ≥65y (Panel B), the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing 2016-2017