This post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial evaluates change in visual field throughout 5 years among eyes treated with panretinal photocoagulation injectable ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Key Points

Question

What are the visual field (VF) changes throughout 5 years after randomized assignment to intravitreal ranibizumab or panretinal photocoagulation for proliferative diabetic retinopathy?

Findings

In this post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial of 234 eyes, eyes in the panretinal photocoagulation group had substantial loss of VF at 1 year and additional VF loss over time. Eyes in the ranibizumab group lost VF sensitivity after 2 years in the absence of laser treatments.

Meaning

While laser treatments account for some of the VF loss over time, these data suggest that other processes may be associated with VF deterioration; however, limitations of the available data prevent more specific conclusions.

Abstract

Importance

Preservation of peripheral visual field (VF) is considered an advantage for anti–vascular endothelial growth factor agents compared with panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) for treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Long-term data on VF are important when considering either treatment approach.

Objective

To further evaluate changes in VF throughout 5 years among eyes enrolled in the Protocol S clinical trial, conducted by the DRCR Retina Network.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Post hoc analyses of an ancillary study within a multicenter (55 US sites) randomized clinical trial. Individuals with eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy enrolled in Protocol S were included. Data were collected from February 2012 to February 2018. Analysis began in June 2018.

Interventions

Panretinal photocoagulation or intravitreous injections of 0.5-mg ranibizumab. Diabetic macular edema, whenever present, was treated with ranibizumab in both groups. Panretinal photocoagulation could be administered to eyes in the ranibizumab group when failure or futility criteria were met.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Mean change in total point score on VF testing with the Humphrey Field Analyzer 30-2 and 60-4 test patterns.

Results

Of 394 eyes enrolled in Protocol S, 234 (59.4%) were targeted for this ancillary study. Of these, 167 (71.4%) had VF meeting acceptable quality criteria at baseline (median [interquartile range] age, 50 [43-58] years; 90 men [53.9%]). At 5 years, 79 (33.8%) had results available. The mean (SD) change in total point score in the PRP and ranibizumab groups was −305 (521) dB and −36 (486) dB at 1 year, respectively, increasing to −527 (635) dB and −330 (645) dB at 5 years, respectively (P = .04). After censoring VF results after PRP treatments in the ranibizumab group, the 5-year mean change in total point score was −201 (442) dB. In a longitudinal regression analysis of change in total point score including both treatment groups, laser treatment was associated with a mean point decrease of 208 (95% CI, 112-304) dB for the initial PRP session, 77 (95% CI, 21-132) dB for additional PRP sessions, and 325 (95% CI, 211-439) dB for endolaser. No association was found between change in point score and the number of ranibizumab injections during the previous year (−9 per injection [95% CI, −22 to 3]).

Conclusions and Relevance

The limited data available from Protocol S suggest that there are factors besides PRP associated with VF loss in eyes treated for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Further clinical research is warranted to clarify the finding.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01489189

Introduction

Although panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) has been the standard treatment for proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) for almost half a century, anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents provide an alternative approach that is safe and effective through at least 5 years.1 Data from the DRCR Retina Network Protocol S indicated that patients randomly assigned to either PRP or ranibizumab treatment maintained good visual acuity through 5 years with low rates of complications of PDR.1 An important difference between treatment groups was the pattern of visual field (VF) loss. Panretinal photocoagulation burns cause VF loss and the PRP group in Protocol S had large losses at 1 year,1,2 as expected, with further decline over the next 4 years. At the primary outcome annual visit of 2 years after initiation of treatment for PDR, there was little change in VF indices in the ranibizumab group; however, VF losses accumulated between 2 and 5 years such that by 5 years, the mean loss in the ranibizumab group was approximately half the amount in the PRP group.1,2 Given that loss of VF with PRP contributes to the decision in choosing between PRP or anti-VEGF monotherapy, additional post hoc analyses were undertaken to explore VF loss in both treatment groups.

Methods

Methods for the DRCR Retina Network Protocol S clinical trial have been published elsewhere1,2 (study protocol available at http://www.drcr.net). Participants were 18 years or older, had type 1 or 2 diabetes, and had at least 1 eye with PDR in the investigator’s judgement and visual acuity of 20/320 or better. A total of 394 study eyes of 305 participants were enrolled from 55 sites in the United States and were randomly assigned 1:1 to either 0.5-mg intravitreous ranibizumab or PRP treatment. Participants with 2 study eyes were randomly assigned to ranibizumab in 1 eye and PRP in the other. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.3 Written informed consent was obtained from participants. The protocol and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant informed consent forms were approved by institutional review boards associated with each site.2 Data were collected from February 2012 to February 2018.

Eyes initially received the assigned treatment. Regardless of treatment assignment, eyes with center-involved diabetic macular edema (DME) and visual impairment were treated with ranibizumab at baseline; treatment of DME with ranibizumab during follow-up was at investigator discretion. The protocol required visits every 16 weeks for both groups, while participants in the ranibizumab group had additional visits every 4 to 16 weeks based on the study retreatment algorithm. Panretinal photocoagulation was allowed in the ranibizumab group if an eye met the protocol-specified failure or futility criteria. Additional PRP could be administered in the PRP group if neovascularization increased.

Annual VF testing was performed at a subset of sites. Participants had perimetry using the Humphrey Field Analyzer 30-2 (76 points) and 60-4 (60 points) test patterns, both with a size V target and FastPac testing strategy.4 A refraction was performed and used for the 30-2 testing only. Graders at the University of Iowa Visual Field Reading Center determined the validity of results. Total point (decibel) scores from each test were summed to provide a combined total point score. The combined mean deviation was the average of the mean deviation from each test pattern weighted by the number of points in the test pattern.

The main analysis was a comparison of mean change from baseline in the combined total point score among the eyes with valid fields and without excessive false positives (>33%) or fixation losses (>33%) at baseline. Outlying values were truncated to 3 SDs from the mean (18 of 491 values [3.7%]). Outcomes were analyzed with a longitudinal, mixed-effects linear regression model including baseline point score, indicator variables for presence of both eyes in the study and baseline central subfield thickness (randomization stratification factors), years after baseline, and time-dependent variables for PRP and endolaser applications and number of ranibizumab injections in the previous year. The intercept and years after treatment were considered random effects, and an autoregressive dependence of scores over time was assumed. The Akaike information criterion statistic was used to measure the fit of the model to the data. Least squares mean values for each annual visit were calculated using the baseline mean values for the total VF point score, inclusion of both eyes in the study, and central subfield thickness, and using 0 ranibizumab injections in the previous year and 0 laser treatments of any kind. All P values and confidence intervals were 2-sided. For these exploratory analyses, P values less than .05 were considered of interest. The analyses for this article were generated using SAS/STAT software, version 15.1 (SAS Institute). Analysis began June 2018.

Results

Study Cohort

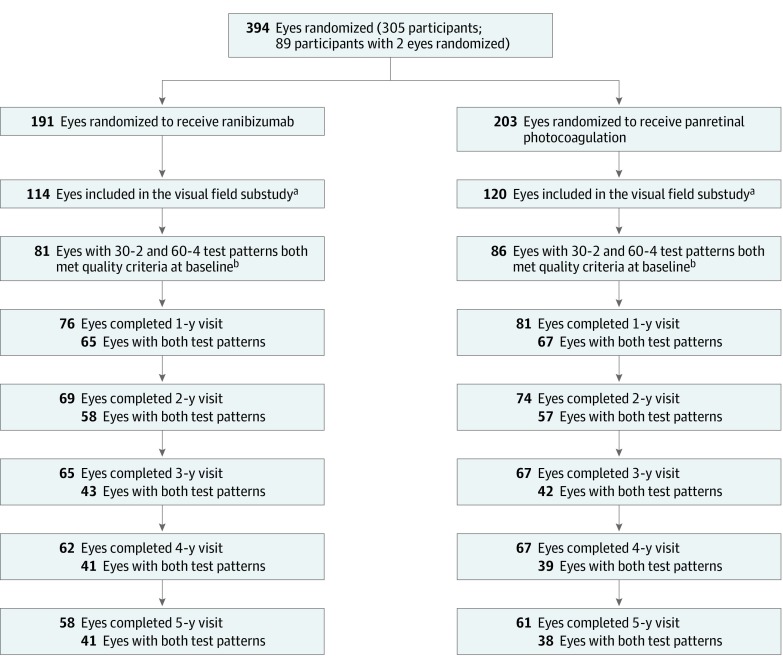

Among 234 study eyes of 177 participants enrolled at 36 sites participating in the ancillary study, 81 of 114 eyes (71.1%) in the ranibizumab group and 86 of 120 eyes (71.7%) in the PRP group completed both test patterns with results that met the quality criteria for VF at baseline, ie, without excessive false positives, excessive fixation losses, or other irregularities invalidating the results (Figure 1). Because of missed visits or participant refusals to undergo VF testing during follow-up, eyes with results for both test patterns decreased at 5 years to 41 of 114 (36.0%) in the ranibizumab group and 38 of 120 (31.7%) in the PRP group. Within the cohort of 167 eyes with baseline VF data meeting the quality criteria, study participants who did not complete the 5-year visit (n = 48) compared with those who had 5-year VF data (n = 79) had a higher proportion of non-Hispanic African American individuals (12 [25%] vs 6 [8%]), shorter median (interquartile range) duration of diabetes (15 [11-21] vs 20 [10-24] years), worse mean visual acuity at baseline (20/40 vs 20/32) and at 2 years (20/32 vs 20/25), and worse mean deviation at baseline (−7.5 dB vs −6.6 dB) (Table 1).5 Participants who completed the 5-year visit but did not have VF testing (n = 40) compared with those with 5-year VF data (n = 79) had a higher proportion of non-Hispanic African American individuals (8 [20%] vs 6 [8%]), a lower proportion with high-risk PDR or worse PDR (8 [21%] vs 37 [47%]), and similar baseline mean visual acuity and VF indices.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Eyes Included in the Ancillary Study on Visual Fields of Participants Enrolled in the Protocol S Clinical Trial.

aDefined as eyes with at least 1 test pattern (either Humphrey Field Analyzer [HFA] 30-2 or HFA 60-4) available at baseline.

bDefined as eyes with both test patterns (HFA 30-2 and HFA 60-4) available and excluding eyes that had excessive false positive or excessive fixation loss at baseline or other irregularities invalidating the results. For HFA 30-2 test, 28 and 32 scans were excluded from ranibizumab and panretinal photocoagulation groups, respectively; for HFA 60-4 test, 30 and 31 scans were excluded, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 167 Eyes With VF Data Available for Analysis at Baseline by 5-Year VF Testing Completion.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-y VF Available | Visit Completed VF Unavailable | Visit Not Completed | |

| No. of eyes | 79 | 40 | 48 |

| Baseline Participant Characteristics | |||

| Female | 40 (51) | 20 (50) | 17 (35) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 49 (43-56) | 51 (45-56) | 51 (40- 60) |

| Participants with 2 study eyes | 42 (53) | 24 (60) | 24 (50) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 44 (56) | 24 (60) | 20 (42) |

| Hispanic | 29 (37) | 4 (10) | 13 (27) |

| Non-Hispanic black/African American | 6 (8) | 8 (20) | 12 (25) |

| Othera | 0 | 4 (10) | 3 (6) |

| Diabetes type | |||

| Type 1 | 18 (23) | 9 (23) | 10 (21) |

| Type 2 | 55 (70) | 29 (73) | 38 (79) |

| Uncertain | 6 (8) | 2 (5) | 0 |

| Duration of diabetes, median (IQR), y | 20 (10-24) | 20 (13- 27) | 15 (11-21) |

| Baseline Ocular Characteristics | |||

| Visual acuity letter score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 79 (11) | 77 (10) | 72 (14) |

| Mean Snellen equivalent | 20/32 | 20/32 | 20/40 |

| OCT central subfield thickness, mean (SD), μmb,c | 254 (92) | 255 (99) | 280 (123) |

| Diabetic retinopathy severity (ETDRS level)d | |||

| ≤Mild PDR (level 61) | 22 (28) | 18 (46) | 13(27) |

| Moderate PDR (level 65) | 20 (25) | 13 (33) | 17 (35) |

| High-risk PDR or worse (level 71, 75, 81, or 85) | 37 (47) | 8 (21) | 18 (38) |

| Presence of CI-DME with visual acuity impairmentc,e | 15 (19) | 6 (15) | 19 (40) |

| Prior treatment for DME | 18 (23) | 11 (28) | 11 (23) |

| Prior anti-VEGF for DME | 6 (8) | 2 (5) | 5 (10) |

| Lens status | |||

| Phakic | 73 (92) | 37 (93) | 44 (92) |

| PC IOL | 6 (8) | 3 (8) | 4 (8) |

| Baseline Humphrey VF Testing Data | |||

| HFA 30-2, mean (SD) | |||

| Cumulative score | 2170 (411) | 2220 (365) | 2130 (358) |

| Mean deviation, dB | −5.7 (5.4) | −5.0 (4.4) | −5.7 (4.1) |

| HFA 60-4, mean (SD) | |||

| Cumulative score | 1290 (338) | 1319 (336) | 1150 (397) |

| Mean deviation, dB | −7.8 (5.4) | −7.2 (5.4) | −9.8 (6.1) |

| HFA 30-2 and HFA 60-4 combined, mean (SD) | |||

| Cumulative score | 3460 (726) | 3539 (654) | 3281 (719) |

| Mean deviation, dB | −6.6 (5.2) | -6.0 (4.4) | −7.5 (4.7) |

| 2-y Ocular Characteristics | |||

| Completers | 78 (99) | 40 (100) | 25 (52) |

| Visual acuity letter score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 81 (12) | 82 (15) | 75 (19) |

| Mean Snellen equivalent | 20/25 | 20/25 | 20/32 |

| Development of CI-DME by 2 yc,d,f | 29 (37) | 13 (33) | 25 (53) |

| 5-y Ocular Characteristics | |||

| Completers | 79 (100) | 40 (100) | 0 |

| Visual acuity letter score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 83 (10) | 81 (15) | NA |

| Mean Snellen equivalent | 20/25 | 20/25 | NA |

| Development of CI-DME by 5 yc,e,f | 36 (46) | 15 (38) | 26 (55) |

Abbreviations: anti-VEGF, anti–vascular endothelial growth factor; CI-DME, center-involved diabetic macular edema; DME, diabetic macular edema; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; HFA, Humphrey Field Analyzer; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PC IOL, posterior chamber intraocular lens; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; VF, visual field.

The Other category included Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, more than 1 race, and unknown/not reported.

Assessments from OCT machines other than Zeiss Stratus were converted to equivalent on Zeiss Stratus.5

Baseline OCT central subfield thickness was unavailable for 1 eye that had available 5-year VF and 1 eye that did not complete 5-year visit.

Baseline diabetic retinopathy severity was unavailable for 1 eye that completed the 5-year visit with VF unavailable.

Defined as visual acuity letter scores of ≤78 (20/32 or worse) and presence of CI-DME on OCT (for Heidelberg Spectralis machines, defined as central subfield thickness ≥305 μm for women and ≥320 μm for men; for Zeiss Cirrus and Optovue RTVue machines, defined as central subfield thickness ≥290 μm for women and ≥305 μm for men; for Zeiss Stratus machines, defined as central subfield thickness ≥250 μm) at baseline. Excluding eyes without baseline OCT central subfield thickness.

Defined as presence of CI-DME with vision impairment at baseline or development of CI-DME on OCT with ≥25-μm increase from baseline at any visit during follow-up. Excluding eyes without baseline OCT central subfield thickness.

Treatment During Follow-up

Among eyes with VF data available at baseline and at least 1 follow-up visit, 4 of 69 eyes (6%) in the ranibizumab group had standard PRP and 8 (12%) had endolaser associated with vitrectomy during follow-up. In the PRP group, 38 of 74 eyes (51%) had 1 or more additional PRP sessions, with most sessions (56 of 71 [79%]) occurring within the first 2 years after randomization; 9 eyes (12%) had 1 or more endolaser sessions during vitrectomy with most eyes (7 of 9 [78%]) treated during the second year after randomization. The mean (SD) number of injections of ranibizumab among patients in the ranibizumab group who completed each annual visit without having had a PRP treatment was 7 (3) in the first year, 4 (3) in the second year, and 3 (3) in each subsequent year. The mean (SD) number of ranibizumab injections after randomization in the PRP group was 3 (4) in the first year, 2 (2) in the second year, 1 (2) in the third, 1 (1) in the fourth year, and 0 (2) in the fifth year.

Visual Field Over Time

At baseline, the mean (SD) combined total point score was 3487 (659) in the PRP group and 3365 (759) in the ranibizumab group; corresponding values for mean deviation were −6.4 (4.6) dB and −7.0 (5.2) dB, respectively. The mean (SD) total point score change from baseline in the PRP group was −305 (521) at 1 year and −422 (518) at 2 years, with additional loss over time through 5 years, at which the mean (SD) total point score change was −527 (635) (Figure 2). In the ranibizumab group, the mean (SD) total point score change was −36 (486) at 1 year, −23 (410) at 2 years, and −330 (645) at 5 years. As reported previously, the difference in mean VF loss between the 2 groups was significant at both 2 and 5 years.1,2 When results of VF testing after application of standard PRP or endolaser were excluded (censored) in the ranibizumab group, the mean (SD) total point score was −201 (442) at 5 years (Figure 2). The point score declined between years 3 and 5 for both the pericentral 30-2 and peripheral 60-4 test patterns for the PRP group and for the ranibizumab group with data censored after laser treatment (eFigures 1 and 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Mean Change From Baseline in the Combined Total Score From the 30-2 and 60-4 Test Pattern.

Outlying values were truncated to 3 SDs from the mean. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The orange line indicates the mean change from baseline over time censoring ranibizumab eyes after the initiation of panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) treatment. NA indicates not applicable.

The mean values over time for the combined mean deviation from the 30-2 and 60-4 test patterns for the same 3 groups as in Figure 2 are shown in eFigure 3 in the Supplement. The average mean deviations for the ranibizumab groups were stable over the first 3 years and decreased between years 3 and 5.

Association Between Visual Field Changes and Treatment

Longitudinal regression modeling was used to assess the associations of ranibizumab injections, laser treatments, and time with total point score during the follow-up period. The mean change in total point score associated with the number of ranibizumab injections in the previous year was −9 (95% CI, −22 to 3; P = .15; Table 2). Application of any type of laser treatment was associated with lower total point score, with mean changes of −208 (95% CI, −304 to −112), −77 (95% CI, −133 to −21), and −325 (95% CI, −439 to −211) associated with the initial PRP session, each additional PRP session, and each endolaser application, respectively. The model with years after baseline as a continuous variable (ie, linear slope) did not fit the data as well as the model with time as a categorical variable (difference in Akaike information criterion = 109.6). Mean change in total point score associated with time from baseline, after accounting for laser treatments and injections, was −34 (95% CI, −175 to 106) at 1 year, −48 (95% CI, −171 to 75) at 2 years, −125 (95% CI, −250 to 1) at 3 years, −168 (95% CI, −294 to −43) at 4 years, and −201 (95% CI, −327 to −74) at 5 years (P value for differences between times = .04). Similar results regarding the associations with the VF total point score of ranibizumab injections, laser treatment, and time were observed under a number of alternative approaches such as using mean deviation as the outcome instead of total point score, including eyes regardless of excessive false positives or fixation losses at baseline, excluding follow-up VF with excessive false positives or fixation losses, using only the 30-2 test pattern or using only the 60-4 test pattern (eTable in the Supplement).

Table 2. Estimates of Mean Change in Total Point Scores Associated With Ranibizumab Injections and Laser Treatment From a Longitudinal Regression Analysis of Change From Baseline in the Total Point Score.

| Factora | Mean Change in Total Point Score (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| No. of ranibizumab injections within the last year | −9 (−22 to 3) | .15 |

| First panretinal photocoagulation | −208 (−304 to −112) | <.001 |

| Each additional panretinal photocoagulation session | −77 (−133 to −21) | .008 |

| Endolaser | −325 (−439 to −211) | <.001 |

Years after baseline as a categorical variable, baseline total point score, number of study eyes per participant, and central subfield thickness on optical coherence tomography at baseline were also included in the model.

Discussion

Because preservation of VF sensitivity is considered an advantage of anti-VEGF monotherapy compared with PRP for treatment of PDR, the changes in VF sensitivity in eyes in both the ranibizumab group and the PRP group of Protocol S of the DRCR Retina Network were evaluated in more detail than presented in our previous reports.1,2 As expected, loss of VF sensitivity was observed in the PRP group; however, the losses observed in the ranibizumab group between years 2 and 5 were unexpected. In the ranibizumab group, there was little or no VF loss on average until after 2 years of follow-up with additional losses through 5 years; however, the magnitude of loss did not reach the level observed in the PRP group through 5 years (P = .04).1 Closer examination of the data has suggested factors that might contribute to some of the loss in VF in the ranibizumab group and raised questions about the possible influence of other factors while also revealing the limitations of the available data.

Based on the data available, there was substantial loss of VF associated with application of laser treatment for PDR, both in the pericentral field corresponding to the 30-2 testing pattern and the peripheral field corresponding in the 60-4 testing pattern. In the longitudinal model describing total VF point score loss, the amount of loss depended on the type of laser treatment applied. On average, additional PRP sessions were associated with less VF loss than an initial PRP session, and endolaser application during vitrectomy was associated with more loss than an initial PRP session. The losses may be direct and immediate effects of heavier vs lighter photocoagulation or reflections of delayed deleterious effects of the treatments, conditions associated with the persistence or return of neovascularization necessitating additional treatment, cataract progression, or, in the case of endolaser with vitrectomy, adverse effects of vitreous hemorrhage or the surgical procedure, such as cataract.

The mean value for the combined mean deviation from the 30-2 and 60-4 test pattern (eFigure 3 in the Supplement) decreased in the ranibizumab group between years 3 to 5 compared with the decrease for the total point score between years 2 and 5 (Figure 2). We have less confidence in the mean deviation results as there is some concern about the accuracy of the age-adjusted normal values for the size V target used for VF testing in this study. Owing to its relatively small size, the normative database used for the age-specific normal values may not be sufficient to provide accurate mean deviation values, especially for older and younger patients.4

After removing the VF data for eyes in the ranibizumab group after laser treatment, the average loss of VF sensitivity was less than when all VF testing during follow-up in the ranibizumab group was included (Figure 2). However, the mean total point score was still less than at baseline by approximately 200 points at 5 years, which is approximately equivalent to a decrease of 1.5 dB in mean deviation. Within this group, the loss of VF did not appear to be a constant amount each year but with more loss in later years; however, the lower number of eyes each year available for analysis limits the ability to accurately identify the pattern of VF loss over time.

Although definitive conclusions cannot be drawn from these results, there are multiple possible reasons for the progression of VF loss seen in the eyes treated only with anti-VEGF therapy in this study. One possible explanation is that progression of the underlying diabetic retinopathy is affecting VF sensitivity. There is evidence that diabetic retinal neurodegeneration progresses with duration of diabetes and may precede signs of diabetic retinopathy.6,7,8,9 Deterioration of the VF in eyes of patients with diabetes in the absence of treatment with laser or pharmacologic agents is evident by the mean deviation at baseline of approximately −6.5 dB for this cohort. Increasing retinal ischemia associated with PDR may cause further deterioration of VF sensitivity despite laser or anti-VEGF. This hypothesis is supported by the results of the CLARITY study of aflibercept vs PRP for PDR where the mean total areas of retinal nonperfusion in both treatment groups increased by 1 year after initiation of treatment.10 A second possible explanation is that the greater cumulative number of ranibizumab injections over time may have caused loss of VF sensitivity. Vascular endothelial growth factor is neuroprotective for retinal cells in a variety of animal models and suppression could theoretically cause VF loss.11,12 A final possible explanation is that ranibizumab may have protected eyes with PDR from VF loss during years 1 and 2 of the study; then, as the number of injections decreased from 7 in year 1, to 4 in year 2, to 3 in later years, the VF loss that is part of the natural history of PDR became apparent. We do not believe that prior or new DME had a strong influence on VF loss because only 4 to 12 testing locations located in the macula among the 76 locations of the 30-2 testing would likely be affected to any degree by center-involved DME and none of the 60 locations in the 60-4 test pattern would be affected.

Limitations

The number of eyes with VF data available and the degree of missing data preclude definitive conclusions about VF changes in eyes treated for PDR. Among the 394 eyes enrolled in Protocol S, 234 eyes were from sites participating in the VF ancillary study. Reliable completion of VF testing proved challenging for patients, and only 167 eyes had VF testing results at baseline deemed sufficiently reliable for further analysis. Further attrition from participants missing annual visits and refusing VF testing resulted in only 79 of 234 eyes (33.8%; 20.1% of total eyes enrolled) with VF results at 5 years. Although the percentage of eyes with 5-year VF data was similar between treatment groups, ocular and participant characteristics differed between those with and without 5-year VF data (Table 1). All the reasons for attrition and differences between those with VF data and those without VF data might be associated with VF loss and could yield results that do not reflect a true estimate of VF changes in the general population of eyes that receive initial anti-VEGF vs PRP for PDR.

Conclusions

In summary, eyes enrolled in Protocol S had substantial VF loss at baseline. Application of scatter laser treatment, particularly endolaser during vitrectomy, was associated with large losses in VF. The VF loss in the ranibizumab group, which occurred predominantly after 2 years of follow-up, was explained only in part by laser treatments during follow-up. More precise conclusions are precluded by the limitations of the available data. Further clinical research is warranted to clarify the situation.

eFigure 1. Mean change from baseline in the total point score from the 30-2 test pattern

eFigure 2. Mean change from baseline in the total point score from the 60-4 test pattern

eFigure 3. Mean value for the combined mean deviation from the 30-2 and 60-4 test patterns

eTable. Estimates of mean change in visual field outcomes associated with ranibizumab injections, laser treatment and time from longitudinal regression analyses of change from baseline level in multiple sensitivity analyses

References

- 1.Gross JG, Glassman AR, Liu D, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Five-year outcomes of panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(10):1138-1148. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.3255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross JG, Glassman AR, Jampol LM, et al. ; Writing Committee for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(20):2137-2146. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wall M, Brito CF, Woodward KR, Doyle CK, Kardon RH, Johnson CA. Total deviation probability plots for stimulus size v perimetry: a comparison with size III stimuli. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(4):473-479. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.4.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Writing Committee, Bressler SB, Edwards AR, Chalam KV, et al. Reproducibility of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography retinal thickness measurements and conversion to equivalent time-domain metrics in diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(9):1113-1122. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellgren KJ, Agardh E, Bengtsson B. Progression of early retinal dysfunction in diabetes over time: results of a long-term prospective clinical study. Diabetes. 2014;63(9):3104-3111. doi: 10.2337/db13-1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynch SK, Abràmoff MD. Diabetic retinopathy is a neurodegenerative disorder. Vision Res. 2017;139:101-107. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barber AJ, Lieth E, Khin SA, Antonetti DA, Buchanan AG, Gardner TW. Neural apoptosis in the retina during experimental and human diabetes: early onset and effect of insulin. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(4):783-791. doi: 10.1172/JCI2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bresnick GH. Diabetic retinopathy viewed as a neurosensory disorder. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104(7):989-990. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050190047037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicholson L, Crosby-Nwaobi R, Vasconcelos JC, et al. Mechanistic evaluation of panretinal photocoagulation versus aflibercept in proliferative diabetic retinopathy: CLARITY substudy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(10):4277-4284. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-23509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foxton RH, Finkelstein A, Vijay S, et al. VEGF-A is necessary and sufficient for retinal neuroprotection in models of experimental glaucoma. Am J Pathol. 2013;182(4):1379-1390. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.12.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Zhang F, Nagai N, et al. VEGF-B inhibits apoptosis via VEGFR-1-mediated suppression of the expression of BH3-only protein genes in mice and rats. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(3):913-923. doi: 10.1172/JCI33673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Mean change from baseline in the total point score from the 30-2 test pattern

eFigure 2. Mean change from baseline in the total point score from the 60-4 test pattern

eFigure 3. Mean value for the combined mean deviation from the 30-2 and 60-4 test patterns

eTable. Estimates of mean change in visual field outcomes associated with ranibizumab injections, laser treatment and time from longitudinal regression analyses of change from baseline level in multiple sensitivity analyses