This nonrandomized controlled trial develops and assesses the effect of the Elder-Friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment (EASE) model among patients 65 years or older undergoing emergency surgery.

Key Points

Question

Will a novel elder-friendly surgical care model reduce major complications and death in an emergency setting?

Findings

In this nonrandomized controlled study of 684 participants 65 years or older, in-hospital major complications or death decreased by 19% at the intervention site, which is clinically meaningful.

Meaning

This study suggests that an elder-friendly approach to the surgical environment may be clinically effective in an emergency setting, and implementation in other surgical specialties may be warranted.

Abstract

Importance

Older adults, especially those with frailty, have a higher risk for complications and death after emergency surgery. Acute Care for the Elderly models have been successful in medical wards, but little evidence is available for patients in surgical wards.

Objectives

To develop and assess the effect of an Elder-Friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment (EASE) model in an emergency surgical setting.

Design, Setting, and Participants

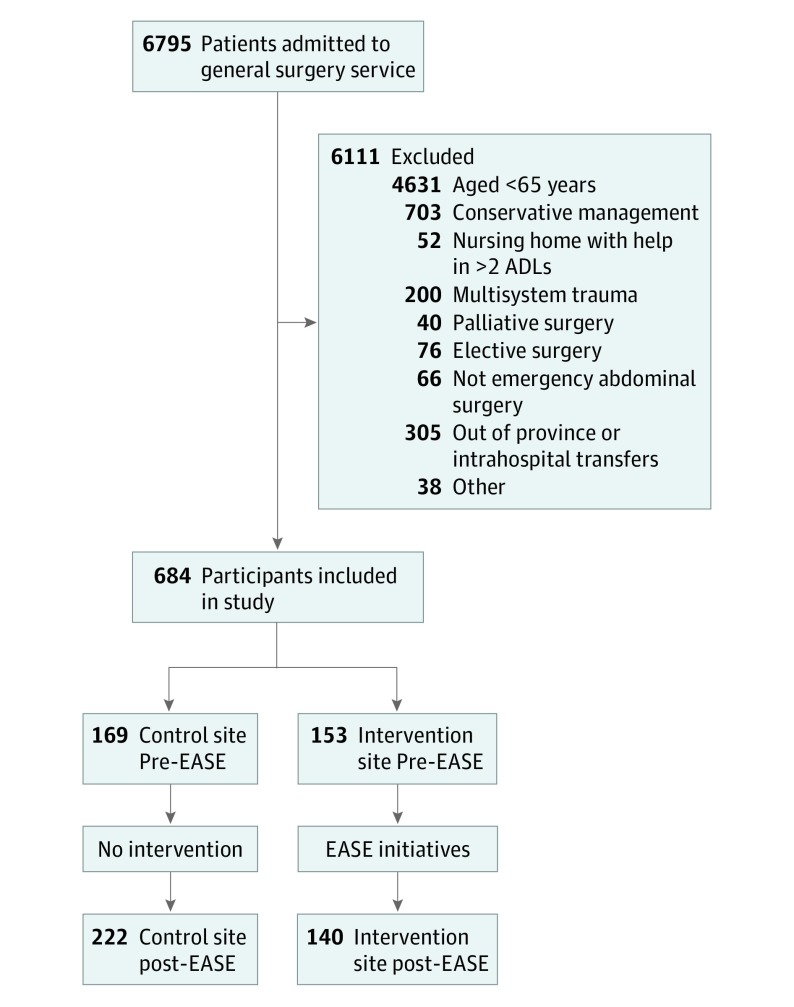

This prospective, nonrandomized, controlled before-and-after study included patients 65 years or older who presented to the emergency general surgery service of 2 tertiary care hospitals in Alberta, Canada. Transfers from other medical services, patients undergoing elective surgery or with trauma, and nursing home residents were excluded. Of 6795 patients screened, a total of 684 (544 in the nonintervention group and 140 in the intervention group) were included. Data were collected from April 14, 2014, to March 28, 2017, and analyzed from November 16, 2018, through May 30, 2019.

Interventions

Integration of a geriatric assessment team, optimization of evidence-based elder-friendly practices, promotion of patient-oriented rehabilitation, and early discharge planning.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Proportion of participants experiencing a major complication or death (composite) in the hospital, Comprehensive Complication Index, length of hospital stay, and proportion of participants who required an alternative level of care on discharge. Covariate-adjusted, within-site change scores were computed, and the overall between-site, preintervention-postintervention difference-in-differences (DID) were analyzed.

Results

A total of 684 patients were included in the analysis (mean [SD] age, 76.0 [7.6] years; 327 women [47.8%] and 357 men [52.2%]), of whom 139 (20.3%) were frail. At the intervention site, in-hospital major complications or death decreased by 19% (51 of 153 [33.3%] vs 19 of 140 [13.6%]; P < .001; DID P = .06), and mean (SE) Comprehensive Complication Index decreased by 12.2 (2.5) points (P < .001; DID P < .001). Median length of stay decreased by 3 days (10 [interquartile range (IQR), 6-17] days to 7 [IQR, 5-14] days; P = .001; DID P = .61), and fewer patients required an alternative level of care at discharge (61 of 153 [39.9%] vs 29 of 140 [20.7%]; P < .001; DID P = .11).

Conclusions and Relevance

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine clinical outcomes associated with a novel elder-friendly surgical care delivery redesign. The findings suggest the clinical effectiveness of such an approach by reducing major complications or death, decreasing hospital stays, and returning patients to their home residence.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02233153

Introduction

With the aging global population, adults 65 years or older represent a significant proportion of patients undergoing acute surgical care across the world. In North America, older adults account for approximately one-third of all patients receiving a surgical intervention and nearly half of all acute inpatient stays.1,2 Frailty is a state of increased vulnerability to diverse stressors, which is increasingly prevalent in later life.3 When older adults with frailty present to the hospital for acute surgical emergencies, they are at a higher risk for postoperative complications, readmission, and death.4,5,6,7 Consequently, frailty has also been shown to be associated with increased health care costs.8

Standard hospital care processes can be risky for older people because they are designed to deal with a single acute illness with expediency.9,10,11,12 Although specialized care for acutely ill older patients is not new, little evidence supported models of geriatric care until the Acute Care for the Elderly (ACE) model.13,14,15,16 Originally developed to curb preventable functional decline experienced by older patients admitted to acute medical hospital wards, the ACE model emphasizes a specialized environment, patient-centered care, medical review, and interdisciplinary care. Compared with traditional care, ACE models on medical wards have demonstrated trends toward decreased cost, length of hospital stay, and readmissions and improved cognition, function, and patient/staff satisfaction.13,15,17 The United Kingdom has led in the incorporation of proactive geriatric surgical care; however, little supporting evidence is available outside of the population undergoing orthopedic procedures.18,19 In particular, no studies, to our knowledge, have evaluated an ACE model for older patients admitted to an acute general surgical ward.

We aimed to develop and assess clinical outcomes after adoption of an Elder-Friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment (EASE) model in an emergency surgical setting. This study was based on the hypothesis that elder-friendly surgical care, including patient co-location, interdisciplinary team-based care, elderly-friendly evidence-based informed practices, patient-oriented rehabilitation, and early discharge planning, would result in decreased major complications and death. The findings from this study should generate new knowledge on acute surgical outcomes in older patients and validate the novel model of care.

Methods

Study Design

The study protocol has been previously published20 and is found in Supplement 1. The EASE study received approval from the research ethics boards of the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, and the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, with a waiver for informed consent granted during the in-hospital phase of the study in those patients who were too critically ill to do so. This study followed the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations With Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) reporting guideline.

Briefly, we conducted a prospective, nonrandomized, controlled before-and-after study at 2 tertiary care hospitals (University of Alberta Hospital, Edmonton, and Foothills Medical Centre, Calgary) in Alberta, Canada, from April 14, 2014, to March 28, 2017. Combined, these 2 sites have an annual volume of more than 1 million unique patients and have similarly structured emergency general surgery services. Data were collected before the intervention from April 14, 2014, to July 23, 2015. This period was followed by a 3-month implementation period when the EASE initiatives were introduced at 1 site with supporting education and compliance monitoring. From September 24, 2015, to March 28, 2017, the intervention site supported the EASE initiatives, whereas the control site provided usual care.

Participant Recruitment

Older patients (aged ≥65 years) were eligible for study inclusion if they had undergone an emergency general operation at either study site. Patients who were transferred from another medical service, resided outside Alberta, or underwent an elective, palliative, trauma, or nonabdominal procedure were excluded. Nursing home residents who required assistance with 3 or more activities of daily living were also excluded given that they already receive the highest level of support and were unlikely to be affected by an intervention focusing on maintenance of independence.

Intervention

The EASE program was a surgical quality improvement initiative that consisted of co-locating older patients to a single unit for better coordination of care; integrating a geriatric assessment team (geriatrician and/or geriatric specialist nurse) into the multidisciplinary health care team; introducing and optimizing evidence-based, elder-friendly practices through the use of a standardized order set (including intentional “comfort” rounds and delirium screening by nursing staff; proactive mobilization; early withdrawal of tubes, lines, urethral catheters, and drains; and elder-friendly appropriate medication use); promoting patient-orientated rehabilitation activities with the BE FIT (Bedside Reconditioning for Functional Improvements) program21; and early discharge planning, which encouraged the team to identify the day of discharge at time of admission with the involvement of the care coordinator (eTable in Supplement 2).

Data Collection

Trained study personnel (including L.M.W.) used standardized case report forms to collect data from medical records review and patient (or surrogate) interviews—in the event that information was missing or unclear in the record—within 48 hours postoperatively and again at the time of discharge. Details included sociodemographic information (age, sex, body mass index [calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters], medical comorbidities, frailty status for the 2 weeks preceding admission, and residence before admission), and hospitalization details (diagnosis, admission vital statistics and blood test results, surgical procedure[s], American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] physical status classification, consultations, requirement for total parenteral nutrition or urinary catheter use, and need for an alternate level of care on discharge). Complications were defined using codes from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision,22 and classified using Clavian-Dindo grade23 as minor (grades I and II) and major (grades III and IV), delirium,24 mortality (in-hospital, 30-day, and 6-month), length of stay, and readmission (within 30 days and 6 months of discharge). Frailty was assessed by the revised Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS).25 Patients with severe or very severe frailty, indicating complete dependence in 3 or more activities of daily living, and terminally ill patients (CFS score ≥7 of a possible 9) were ineligible for the EASE study.

At the time of discharge (to not influence the uptake of the intervention after the implementation phase), medical records were also reviewed to assess for adherence to the intervention. At the intervention site, study personnel retrieved details regarding placement on the specific EASE unit (co-location), use of the standardized postoperative order set (evidence-informed practices and transition optimization), notes of participation in the exercise program (reconditioning), and comprehensive geriatric assessment (interdisciplinary care).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was a composite of the proportion of participants who experienced a major postoperative in-hospital complication (Clavian-Dindo grades III and IV; eg, intensive care unit admission, vascular complications, serious infections, or protracted delirium24) or death. The Comprehensive Complication Index,26,27 a validated, continuous scale that summarizes all postoperative complications weighted by severity, was also calculated. Secondary outcomes included the composite proportion of patients who died or were readmitted within 30 days and 6 months of initial discharge, the proportion of patients who experienced minor in-hospital complications, length of hospital stay, and requirement for alternative level of care (defined as being discharged to a facility providing a higher level of care than they were receiving before admission).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from November 16, 2018, through May 30, 2019. We conducted descriptive analyses for participant characteristics and hospitalization details and outcomes, calculating means and SDs, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), proportions, and measures of central tendency. Separate pre-EASE and post-EASE comparisons within sites were performed using χ2 tests for categorical variables, unpaired 2-tailed t tests for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for nonnormally distributed variables. For our primary and secondary outcomes, within-site pre-EASE vs post-EASE effects were estimated using a logistic regression, generalized linear regression with negative binomial or a Poisson regression model depending on the characteristics of the data. All models were adjusted using stepwise selection (significance level to allow into the model, 2-sided P = .25; significance level to keep in the model, 2-sided P = .25) with baseline age, sex, body mass index, ethnicity, blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, hemoglobin level, creatinine level, diagnosis, medical comorbidities, operative procedure, CFS, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and/or ASA physical status classification. Degree of frailty was defined as very fit to well (termed well; CFS score of 1 or 2), managing well to vulnerable (termed vulnerable; CFS score of 3 or 4), or mildly to moderately frail (termed frail; CFS score of 5 or 6). Subsequently, we used a difference-in-differences (DID) approach to directly compare estimated within-site effects between sites. In detail, we used the estimated within-site effects and SEs to generate normal distributions, then calculated the size of the overlap of the area between the distributions as an estimate of the difference in effect between sites. Because estimated within-site effects are maximal likelihood estimates, form asymptotic theory in statistics suggests that we may reasonably view them as having normal distribution. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 15 (StataCorp LLC), and SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc) statistical software.

Results

Recruitment and Participant Characteristics

Of 6795 patients screened, most were excluded because of age and nonsurgical management (Figure 1). A total of 684 participants (322 before and 362 after the intervention) were included (mean [SD] age, 76.0 [7.6] years; 327 women [47.8%] and 357 men [52.2%]), with 544 patients receiving standard care and 140 patients receiving EASE interventions.

Figure 1. Participant Flow Diagram.

ADLs indicates activities of daily living; EASE, Elder-Friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment.

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean (SD) body mass index was 27.1 (5.9). One hundred fifty patients (21.9%) were classified as well, 395 (57.7%) as vulnerable, and 139 (20.3%) as frail. Charlson comorbidity scores ranged from 0 to 7 and mean (SD) ASA physical status classification was 2.7 (0.8). Most participants were living within the community without formal support (626 [91.5%]), and most were admitted through the emergency department (576 [84.2%]). The most frequent diagnoses included cholecystitis (177 diagnoses [25.9%]), intestinal obstruction (128 [18.7%]), hernia (99 [14.5%]), and appendicitis (82 [12.0%]). After surgery, most participants returned to the acute care surgery ward (607 [88.7%]), with 67 (11.0%) of these requiring an intensive care admission immediately postoperatively. When we compared pre-EASE and post-EASE findings within each site, participant characteristics and hospitalization details largely remained similar.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Control Site | Intervention Site | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-EASE (n = 169) | Post-EASE (n = 222) | Pre-EASE (n = 153) | Post-EASE (n = 140) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 76.0 (7.6) | 75.0 (7.6) | 76.1 (7.7) | 75.1 (7.6) |

| Female, No. (%) | 74 (43.8) | 108 (48.6) | 72 (47.1) | 73 (52.1) |

| Married, No. (%) | 115 (68.0) | 148 (66.7) | 115 (75.2) | 85 (60.7) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27.8 (6.5) | 27.1 (5.5) | 26.4 (5.6) | 27.0 (6.1) |

| No. of admission medications, mean (SD) | 4.72 (3.44) | 4.28 (3.05) | 5.01 (3.69) | 4.95 (4.39) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR)a | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-2) |

| CFS score, No. (%)b | ||||

| Well | 28 (16.6) | 40 (18.0) | 44 (28.8) | 38 (27.1) |

| Vulnerable | 103 (60.9) | 149 (67.1) | 69 (45.1) | 74 (52.9) |

| Frail | 38 (22.5) | 33 (14.9) | 40 (26.1) | 28 (20.0) |

| No. of surgical procedures, median (IQR) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) |

| ASA physical system classification, mean (SD)c | 2.6 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.9 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.7)d |

| Surgery type, No. (%) | ||||

| Closed appendectomy/cholecystectomy | 62 (36.7) | 86 (38.7)d | 25 (16.3) | 45 (32.1)d |

| Open appendectomy/cholecystectomy | 6 (3.6) | 10 (4.5)d | 17 (11.1) | 9 (6.4)d |

| Hernia repair | 17 (10.1) | 26 (11.7)d | 28 (18.3) | 22 (15.7)d |

| Small intestine surgery | 53 (31.4) | 47 (21.2)d | 38 (24.8) | 36 (25.7)d |

| Colon surgery | 15 (8.9) | 40 (18.0)d | 31 (20.3) | 20 (14.3)d |

| Other | 16 (9.5) | 13 (5.9)d | 14 (9.2) | 8 (6)d |

| Time in operating room, mean (SD), min | 88.9 (42.6) | 95.4 (43.7) | 136 (60.0) | 134 (62.7) |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters); CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; EASE, Elder-Friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment; IQR, interquartile range.

Scores range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating a greater number of comorbidities.

Well indicates CFS score of 1 or 2; vulnerable, CFS score of 3 or 4; and frail, CFS score of 5 or 6.

Scores range from 1 to 6, with higher scores indicating worse physical status.

P ≤ .05 compared with within-site pre-EASE group.

Intervention Adherence and Care Implications

One hundred thirty participants (92.9%) in the intervention group received at least some portion of the EASE initiatives; of those who received no intervention (n = 10), 7 were discharged on postoperative day 1. Adherence to each EASE initiative varied from 52.1% to 60.6% (Table 2). Geriatric consultations increased more than 8-fold at the intervention site (10 of 153 [6.5%] to 79 of 136 [58.1%]; P < .001).

Table 2. Intervention Adherence Measures.

| Measure | Control Site | Intervention Site | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-EASE (n = 169) | Post-EASE (n = 222) | Pre-EASE (n = 153) | Post-EASE (n = 140) | |

| EASE unit after operation, No. (%) | NA | NA | NA | 73 (52.1) |

| EASE standardized order set used, No. (%)a | NA | NA | NA | 69 (52.3) |

| BE FIT reconditioning program, No. (%)a | NA | NA | NA | 80 (60.6) |

| Geriatric consultations, No. (%)b | 2 (1.2) | 11 (5.0)c | 10 (6.5) | 79 (58.1)c |

| Time to mobilization, mean (SD), h | 30.2 (68.3) | 27.5 (47.8) | 46.4 (76.6) | 29.1 (68.3)c |

| Patients with urinary catheter, No. (%) | 99 (58.6) | 120 (54.1) | 117 (76.5) | 89 (63.6)c |

| Duration of urinary catheter use, median (IQR), d | 3 (2-5) | 2 (1-5) | 3 (2-6) | 2 (1-5)c |

| Patients with total parenteral nutrition, No. (%) | 30 (17.8) | 30 (13.5) | 42 (27.5) | 19 (13.6)c |

| Duration of total parenteral nutrition, median (IQR), d | 7 (5-12) | 7 (4-11) | 6.5 (3-13) | 7 (5-13) |

| Patients with delirium, No. (%) | 34 (20.1) | 44 (19.8) | 39 (25.5) | 18 (12.9)c |

| Patients waiting for discharge, No. (%) | 18 (10.7) | 65 (29.3)c | 29 (19.0) | 15 (10.7)c |

| Duration of wait for discharge, median (IQR), d | 2 (1-5) | 1 (1-2) | 4 (2-8) | 2 (1-12) |

Abbreviations: BE FIT, Bedside Reconditioning for Functional Improvements; EASE, Elder-Friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable.

For post-EASE measures at the intervention site, 132 patients were included; patients in the intensive care unit were not eligible for this intervention.

For post-EASE measures at the intervention site, 136 patients were included; those discharged within 24 hours of admission were not eligible for this intervention.

P < .05 compared with within-site pre-EASE group.

When we compared pre-EASE and post-EASE findings within the intervention site, there were statistically significant decreases in the use of urinary catheters (117 of 153 patients [76.5%] to 89 of 140 [63.6%]) and in total parenteral nutrition (42 of 153 [27.5%] to 19 of 140 [13.6%]), and participants were quicker to mobilize after surgery (mean [SD] time, 46.4 [76.6] to 29.1 [68.3] hours) (P < .05 for all) (Table 2). Incidence of delirium was reduced by half (39 of 153 [25.5%] to 18 of 140 [12.9%]; P = .006) at the intervention site. There was no significant change in the control site. Although a statistically significant increase in the proportion of geriatric consultations from 1.2% (2 of 169) to 5.0% (11 of 222) (P = .05) occurred at the control site, the proportion of participants diagnosed with delirium did not change (34 of 169 [20.1%] in the pre-EASE period and 44 of 222 [19.8%] in the post-EASE period; P = .95).

Major Complications and Death

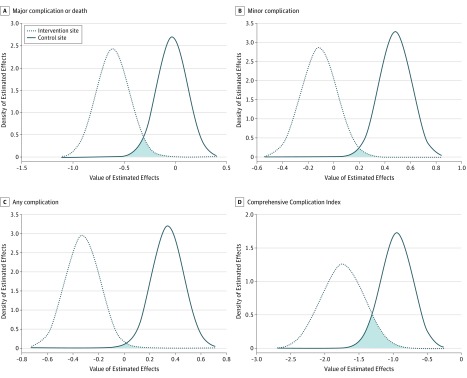

Overall, 29 participants (4.2%) died within the hospital, with 26 of those participants (89.7%) also having a complication during their hospital stay. In the pre-EASE and post-EASE comparison at the intervention site, a statistically significant 19% decrease occurred in our composite primary outcome of in-hospital major complication or death (P < .001) and a 19% decrease in all complications (P < .001) (Table 3). After adjustment, a significant before-after intervention effect was found for the proportion of participants who experienced any complication (β coefficient [SE], −0.32 [0.13]; P = .01). The mean (SE) Comprehensive Complication Index decreased by 12.2 (2.5) points, which has a statistically significant before-after intervention effect after adjustment (β coefficient [SE], −1.74 [0.32]; P < .001). There was also a significant decrease in minor complications at the intervention site compared with an increase at the control site (54 of 153 [35.3%] to 38 of 140 [27.1%] vs 54 of 169 [32.0%] to 110 of 222 [49.5%]; DID P = .02) (Table 3). At the control site, there was no change in the proportion of participants who experienced a major in-hospital complication or death (38 of 169 [22.5%] vs 48 of 222 [21.6%]; P = .83), but there was an 11% increase in total complications (P = .03) and 18% increase in minor complications (P < .001), which had statistically significant before-after effects after adjustment (β coefficient [SE] for total complications, 0.34 [0.12] [P = .006]; β coefficient [SE] for minor complications, 0.48 [0.12] [P < .001]) (Table 3). Comparing sites, there was a significant DID effect for total complications (DID estimate [SD], −0.6673 [0.1833]; DID P = .01) and the Comprehensive Complication Index (DID estimate [SD], −0.7932 [0.3924]; DID P < .001) (Figure 2).

Table 3. Outcomes: Complications and Death, Length of Stay, Discharge Status, and Postdischarge Death or Readmission.

| Outcome | Control Site | Intervention Site | DID P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-EASE (n = 169) | Post-EASE (n = 222) | Adjusted Pre-EASE to Post-EASE Effect, β Coefficient (SE) | Pre-EASE (n = 153) | Post-EASE (n = 140) | Adjusted Pre-EASE to Post-EASE Effect, β Coefficient (SE) |

||

| Major complication or death, composite, No. (%) | 38 (22.5) | 48 (21.6) | −0.03 (0.14) | 51 (33.3) | 19 (13.6)a | −0.61 (0.16) | .06 |

| Comprehensive Complication Index, mean (SD) | 24.1 (2.5) | 29.5 (2.6) | −0.95 (0.23) | 31.2 (3.1) | 19.0 (3.2)a | −1.74 (0.32)a | <.001 |

| Any complication, No. (%) | 72 (42.6) | 120 (54.1)a | 0.34 (0.12)a | 77 (50.3) | 43 (30.7)a | −0.32 (0.13)a | .01 |

| Minor complication, No. (%) | 54 (32.0) | 110 (49.5)a | 0.48 (0.12)a | 54 (35.3) | 38 (27.1) | −0.12 (0.13) | .02 |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 8 (5-12) | 8 (5-14) | −0.97 (0.07)a | 10 (6-17) | 7 (5-14)a | −1.04 (0.09) | .61 |

| Alternative level of care at discharge, No. (%) | 31 (18.3) | 51 (23.0) | 0.28 (0.17) | 61 (39.9) | 29 (20.7)a | −0.30 (0.19) | .11 |

| Death or readmission within 30 d, No. (%) | 26 (15.4) | 30 (13.5) | −0.45 (0.21)a | 30 (19.6) | 18 (12.9) | −0.24 (0.17) | .58 |

| Death or readmission within 6 mo, No. (%) | 58 (34.3) | 50 (22.5)a | −0.42 (0.15)a | 61 (39.9) | 41 (29.3) | −0.17 (0.15) | .41 |

Abbreviations: DID, difference-in-differences; EASE, Elder-Friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment; IQR, interquartile range; SE, standard error.

P < .05.

Figure 2. Primary Outcome Effects Distributions.

Secondary Outcomes

At the intervention site, the median length of stay decreased by 3 days (10 [IQR, 6-17] vs 7 [IQR, 5-14] days; P = .001), whereas there was no change at the control site (8 [IQR, 5-12] vs 8 [5-14] days; P = .75) (Table 3). The number of participants requiring an alternative level of care at discharge decreased by almost half at the intervention site (61 of 153 [39.9%] vs 29 of 140 [20.7%]; P < .001), with no change observed at the control site (31 of 169 [18.3%] to 51 of 222 [23.0%]; P = .28). Death or readmission was unchanged at 30 days (control group, 26 of 169 [15.4%] vs 30 of 222 [13.5%] [P = .03]; intervention group, 30 of 153 [19.6%] vs 18 of 140 [12.9%] [P = .15]; DID P = .58) and 6 months (control group, 58 of 169 [34.3%] vs 50 of 222 [22.5%] [P = .005]; intervention group, 61 of 153 [39.9%] vs 41 of 140 [29.3%] [P = .26]; DID P = .41).

Discussion

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to examine clinical outcomes after the adoption of a novel care delivery redesign—EASE—for older patients receiving emergency general surgery. This multicenter study successfully implemented elder-friendly care practices, with surrogate measures of compliance showing initiative uptake and sustained care implications. We demonstrated clinically important improvements to in-hospital major complications and death, and the intervention was associated with significant clinical improvements in minor complications, length of hospitalization, and need for alternative level of care. Our findings suggest that implementation of low-cost, elder-friendly surgical care may improve outcomes in patients undergoing emergency general surgery, similar to the benefits shown in medical inpatient ACE programs. We anticipate that the EASE interventions can be adapted to other surgical centers to benefit all older patients undergoing surgery.

Adverse outcomes in this group involve a complex association between baseline vulnerability and precipitating insults occurring during hospitalization.9,28 Mortality and complications increase progressively with age.29 An important complication, delirium, is associated with poor outcome30,31,32 and is highly prevalent in the surgical population, ranging from 18% to 55%.33,34 In previous work, prolonged postoperative delirium was associated with urinary catheter use and frailty status.28 By providing standardized, evidence-informed education and materials to the surgical team members, having early involvement of a multidisciplinary team that included a geriatrician and/or geriatric nurse specialist, and following established elder-friendly protocols and practices, we were able to enact preventive measures or quickly intervene on emerging complications among a cohort of co-located older surgical patients. Of importance, Sheetz et al35 demonstrated that the failure to rescue patients from major complications was the leading factor in the variation in mortality rates. Their work emphasizes the importance of the development of age-specific care practices, which allow care teams to prevent and promptly identify complications. Further research is necessary to establish whether ACE models of care can reduce failure to rescue. The diminished physiological reserve of our older patients does not allow grace in missing early signs of issues or errors in treatment.36

Assessing frailty is essential to improving postoperative care among older patients because patients identified as vulnerable (without evident disability) are also at higher risk for readmission and death.5 Few surgical studies have screened patients for and intervened on their frailty status.37,38 Evidence supports the use of well-validated frailty assessments within a comprehensive geriatric assessment.19,39,40,41 Comprehensive geriatric assessment, although proven effective and considered the criterion standard for assessing preoperative risk, is difficult to deliver given the amount of time required to evaluate patients in the acute care setting and limitations in the number of individuals trained to do these assessments.42 Our study added a geriatrician to the surgical team; however, many centers may not have this resource. Frailty assessment is truly a missed opportunity for the surgical team,43 and with a plethora of instruments available,44 physicians have the ability in incorporate clinical judgments about frailty into their assessment to yield useful predictive information about their older patients.

Sarcopenia, a frailty-related loss of skeletal muscle, is significantly associated with postoperative complications and in-hospital mortality45; bed rest leads to an accelerated loss of muscle strength and has been established as a risk for complications.46,47,48 Although medically ready at the time of discharge, hospitalized older patients frequently experience a loss of independence in activities of daily living, resulting in the need for additional support or a higher level of care.7,49 This experience suggests that mobilization during hospitalization to maintain muscle strength is critical for older patients undergoing surgery. Current guidelines50,51 promote early mobilization. In our study, the BE FIT program was able to reduce the time to first mobilization and has been shown to improve functional outcomes in a subset of participants.21

Limitations

Limitations of our study relate to the before-and-after intervention design. Although our control group provides some evidence that changes occurring over time were not the result of natural temporal trends or of unmeasured events that occurred contemporaneously with the exposure under study, a risk of unidentified confounders in studies that lack randomization always remains.52 Before-and-after studies with controls are recognized by the Effective Practice Organization and Change arm of the Cochrane Collaboration as being valid, high-quality sources of evidence to inform decision-making in the absence of randomized clinical trials.52

Statistically, the DID analysis assumes that if the treated participants had not been subjected to the treatment, both subpopulations would have experienced the same outcome trends over time (parallel trend assumption)53; the ability of our statistical analysis to detect true between-site differences is severely limited because this assumption is violated due to the inherent variability seen in emergency general surgery services. Schuster et al54(p909) state perfectly: “While the diversity of EGS [emergency general surgery] conditions makes for a stimulating clinical practice, this same diversity poses challenges for EGS research and quality improvement initiatives.” For this reason, along with the intrinsic potential for misinterpretation of results based on P value alone,55,56 care must be taken in focusing on the DID P values. We have thus strengthened our approach by providing several complication outcome measures.

Last, because this was a bundled intervention, it was impossible to measure the effect of each component. However, complex problems require multimodal solutions; for example, the prevention of vascular catheter-related bloodstream infections has been addressed by implementing central line bundles based on a landmark study by Pronovost et al.57 The process allowed each team to implement and tailor the intervention to the barriers and contextual factors on their unit. This procedure was adopted by the Canadian Patient Safety Institute in 2011 and is now used throughout the world. Similarly, EASE provided a low-cost multimodal care framework to address the concurrent issues of acute illness, multimorbidity, and intrahospitalization stressors that affect the elderly surgical population.

Conclusions

General surgeons traditionally pride themselves on having a holistic approach to their patients and being able to care for most of their patients’ clinical needs.58,59 Given the increase in older patients admitted for surgery, their complex comorbidities and frailty, and the resulting burden to the health care system, general surgeons need to reassess their approach to caring for older adults. Failure to consider these factors results in poor outcomes and longer lengths of hospital stay and increases the need for institutionalization after surgery. These outcomes ultimately result in increased use of health care resources and cost.8,60,61 The dissemination of ACE as a surgical intervention has been limited because it requires the transformation of the culture of usual care.16 The present study demonstrates a novel approach of elder-friendly initiatives in an acute care surgery environment, which resulted in a reduction in major complications and death. This patient-centered care also resulted in earlier mobilization and return to home.

As surgeons continue to operate on older, sicker, and more frail patients, elder-friendly surgical care demonstrates significant clinical improvement in hospital stay, complications, and death. Further research is required to evaluate the costs, sustainability, and feasibility of this intervention in other centers and other surgical populations.

Trial Protocol

eTable. EASE Interventions

eReferences

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics National Hospital Discharge Survey. Washington, DC: CDC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Institute for Health Information Health care in Canada, 2011: a focus on seniors and aging. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/HCIC_2011_seniors_report_en.pdf. Published December 1, 2011. Accessed May 23, 2019.

- 3.Rockwood K, Bergman H. FRAILTY: a report from the 3(rd) Joint Workshop of IAGG/WHO/SFGG, Athens, January 2012. Can Geriatr J. 2012;15(2):-. doi: 10.5770/cgj.15.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du Y, Karvellas CJ, Baracos V, Williams DC, Khadaroo RG; Acute Care and Emergency Surgery (ACES) Group . Sarcopenia is a predictor of outcomes in very elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery. Surgery. 2014;156(3):521-527. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Pederson JL, Churchill TA, et al. . Impact of frailty on outcomes after discharge in older surgical patients: a prospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2018;190(7):E184-E190. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.161403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torrance ADW, Powell SL, Griffiths EA. Emergency surgery in the elderly: challenges and solutions. Open Access Emerg Med. 2015;7:55-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lees MC, Merani S, Tauh K, Khadaroo RG. Perioperative factors predicting poor outcome in elderly patients following emergency general surgery: a multivariate regression analysis. Can J Surg. 2015;58(5):312-317. doi: 10.1503/cjs.011614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eamer GJ, Clement F, Holroyd-Leduc J, Wagg A, Padwal R, Khadaroo RG. Frailty predicts increased costs in emergent general surgery patients: a prospective cohort cost analysis. Surgery. 2019;166(1):82-87. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2019.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inouye SK. Prevention of delirium in hospitalized older patients: risk factors and targeted intervention strategies. Ann Med. 2000;32(4):257-263. doi: 10.3109/07853890009011770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parke B, Brand P. An elder-friendly hospital: translating a dream into reality. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont). 2004;17(1):62-76. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2004.16344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelley ML, Parke B, Jokinen N, Stones M, Renaud D. Senior-friendly emergency department care: an environmental assessment. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16(1):6-12. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2010.009132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parke B, Chappell NL. Transactions between older people and the hospital environment: a social ecological analysis. J Aging Stud. 2010;24:115-124. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2008.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steele JS. Current evidence regarding models of acute care for hospitalized geriatric patients. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31(5):331-347. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed NN, Pearce SE. Acute care for the elderly: a literature review. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13(4):219-225. doi: 10.1089/pop.2009.0058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox MT, Persaud M, Maimets I, et al. . Effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care using Acute Care for Elders components: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(12):2237-2245. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer RM. The Acute Care for Elders unit model of care. Geriatrics (Basel). 2018;3(3):59. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics3030059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed N, Taylor K, McDaniel Y, Dyer CB. The role of an Acute Care for the Elderly unit in achieving hospital quality indicators while caring for frail hospitalized elders. Popul Health Manag. 2012;15(4):236-240. doi: 10.1089/pop.2011.0055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harari D, Hopper A, Dhesi J, Babic-Illman G, Lockwood L, Martin F. Proactive care of older people undergoing surgery (“POPS”): designing, embedding, evaluating and funding a comprehensive geriatric assessment service for older elective surgical patients. Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):190-196. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eamer G, Taheri A, Chen SS, et al. . Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older people admitted to a surgical service. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:CD012485. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012485.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khadaroo RG, Padwal RS, Wagg AS, Clement F, Warkentin LM, Holroyd-Leduc J. Optimizing senior’s surgical care: Elder-Friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment (EASE) study: rationale and objectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):338. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1001-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McComb A, Warkentin LM, McNeely ML, Khadaroo RG. Development of a reconditioning program for elderly abdominal surgery patients: the Elder-friendly Approaches to the Surgical Environment-BEdside reconditioning for Functional ImprovemenTs (EASE-BE FIT) pilot study. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13017-018-0180-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P-A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205-213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method: a new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. . A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489-495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slankamenac K, Nederlof N, Pessaux P, et al. . The Comprehensive Complication Index: a novel and more sensitive endpoint for assessing outcome and reducing sample size in randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg. 2014;260(5):757-762. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clavien P-A, Vetter D, Staiger RD, et al. . The Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI®): added value and clinical perspectives 3 years “down the line”. Ann Surg. 2017;265(6):1045-1050. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saravana-Bawan B, Warkentin LM, Rucker D, Carr F, Churchill TA, Khadaroo RG. Incidence and predictors of postoperative delirium in the older acute care surgery population: a prospective study. Can J Surg. 2019;62(1):33-38. doi: 10.1503/cjs.016817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turrentine FE, Wang H, Simpson VB, Jones RS. Surgical risk factors, morbidity, and mortality in elderly patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):865-877. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raats JW, Steunenberg SL, Crolla RM, Wijsman JH, te Slaa A, van der Laan L. Postoperative delirium in elderly after elective and acute colorectal surgery: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;18:216-219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.04.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. . A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271(2):134-139. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510260066030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holroyd-Leduc JM, Abelseth GA, Khandwala F, et al. . A pragmatic study exploring the prevention of delirium among hospitalized older hip fracture patients: applying evidence to routine clinical practice using clinical decision support. Implement Sci. 2010;5:81. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Castro SM, Ünlü Ç, Tuynman JB, et al. . Incidence and risk factors of delirium in the elderly general surgical patient. Am J Surg. 2014;208(1):26-32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ansaloni L, Catena F, Chattat R, et al. . Risk factors and incidence of postoperative delirium in elderly patients after elective and emergency surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97(2):273-280. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheetz KH, Dimick JB, Ghaferi AA. Impact of hospital characteristics on failure to rescue following major surgery. Ann Surg. 2016;263(4):692-697. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheetz KH, Waits SA, Krell RW, Campbell DA Jr, Englesbe MJ, Ghaferi AA. Improving mortality following emergent surgery in older patients requires focus on complication rescue. Ann Surg. 2013;258(4):614-617. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a5021d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engelhardt KE, Reuter Q, Liu J, et al. . Frailty screening and a frailty pathway decrease length of stay, loss of independence, and 30-day readmission rates in frail geriatric trauma and emergency general surgery patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;85(1):167-173. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDonald SR, Heflin MT, Whitson HE, et al. . Association of integrated care coordination with postsurgical outcomes in high-risk older adults: the Perioperative Optimization of Senior Health (POSH) initiative. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(5):454-462. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Partridge JS, Harari D, Martin FC, Dhesi JK. The impact of pre-operative comprehensive geriatric assessment on postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing scheduled surgery: a systematic review. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(suppl 1):8-16. doi: 10.1111/anae.12494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pajulammi HM, Pihlajamäki HK, Luukkaala TH, Jousmäki JJ, Jokipii PH, Nuotio MS. The effect of an in-hospital comprehensive geriatric assessment on short-term mortality during orthogeriatric hip fracture program: which patients benefit the most? Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2017;8(4):183-191. doi: 10.1177/2151458517716516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oo MT, Tencheva A, Khalid N, Chan YP, Ho SF. Assessing frailty in the acute medical admission of elderly patients. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2013;43(4):301-308. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2013.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kocman D, Regen E, Phelps K, et al. . Can comprehensive geriatric assessment be delivered without the need for geriatricians? a formative evaluation in two perioperative surgical settings. Age Ageing. 2019;afz025. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eamer G, Gibson JA, Gillis C, et al. . Surgical frailty assessment: a missed opportunity. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12871-017-0390-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faller JW, Pereira DDN, de Souza S, Nampo FK, Orlandi FS, Matumoto S. Instruments for the detection of frailty syndrome in older adults: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0216166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dag A, Colak T, Turkmenoglu O, Gundogdu R, Aydin S. A randomized controlled trial evaluating early versus traditional oral feeding after colorectal surgery. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66(12):2001-2005. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011001200001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.English KL, Paddon-Jones D. Protecting muscle mass and function in older adults during bed rest. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13(1):34-39. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328333aa66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Morton NA, Keating JL, Jeffs K. Exercise for acutely hospitalised older medical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD005955. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005955.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219-223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. . Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451-458. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carmichael JC, Keller DS, Baldini G, et al. . Clinical practice guidelines for enhanced recovery after colon and rectal surgery from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(8):761-784. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chow WB, Rosenthal RA, Merkow RP, Ko CY, Esnaola NJ; American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; American Geriatrics Society . Optimal perioperative management of the geriatric surgical patient: a best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons NSQIP and the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(5):930-947. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryan R, Hill S, Broclain D, Horey D, Oliver S, Prictor M; Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group Study design guide. https://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources. Published June 2013. Accessed August 21, 2019.

- 53.Lechner M. The estimation of causal effects by difference-in-difference methods. Found Trends Econom. 2010;4(3):165-224. doi: 10.1561/0800000014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schuster K, Davis K, Hernandez M, Holena D, Salim A, Crandall M. American Association for the Surgery of Trauma emergency general surgery guidelines gap analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86(5):909-915. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amrhein V, Greenland S, McShane B. Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature. 2019;567(7748):305-307. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-00857-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA statement on P values: context, process, and purpose. Am Stat. 2016;70(2):129-133. doi: 10.1080/00031305.2016.1154108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. . An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(26):2725-2732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taurchini M, Del Naja C, Tancredi A. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a patient centered process. J Vis Surg. 2018;4:40. doi: 10.21037/jovs.2018.01.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ljungqvist O, Young-Fadok T, Demartines N. The history of enhanced recovery after surgery and the ERAS society. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017;27(9):860-862. doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Healy MA, Mullard AJ, Campbell DA Jr, Dimick JB. Hospital and payer costs associated with surgical complications. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(9):823-830. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eamer GJ, Clement F, Pederson JL, Churchill TA, Khadaroo RG. Analysis of postdischarge costs following emergent general surgery in elderly patients. Can J Surg. 2018;61(1):19-27. doi: 10.1503/cjs.002617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable. EASE Interventions

eReferences