Abstract

Background

Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) can cause severe neurological morbidity but our understanding of the mechanisms that drive CCM formation and growth is still incomplete. Recent experimental data suggest that dysfunctional CCM3-deficient endothelial cell clones form cavernous lesions in conjunction with normal endothelial cells.

Objective

In this study, we addressed the question whether endothelial cell mosaicism can be found in human cavernous tissue of CCM1 germline mutation carriers.

Methods and results

Bringing together single-molecule molecular inversion probes in an ultra-sensitive sequencing approach with immunostaining to visualise the lack of CCM1 protein at single cell resolution, we identified a novel late postzygotic CCM1 loss-of-function variant in the cavernous tissue of a de novo CCM1 germline mutation carrier. The extended unilateral CCM had been located in the right central sulcus causing progressive proximal paresis of the left arm at the age of 15 years. Immunohistochemical analyses revealed that individual caverns are lined by both heterozygous (CCM1+/−) and compound heterozygous (CCM1−/−) endothelial cells.

Conclusion

We here demonstrate endothelial cell mosaicism within single caverns of human CCM tissue. In line with recent in vitro data on CCM1-deficient endothelial cells, our results provide further evidence for clonal evolution in human CCM1 pathogenesis.

Keywords: cerebral cavernous malformations, postzygotic mosaicism, two-hit model of knudson, late postzygotic mutation, smmips

Introduction

Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) are dysfunctional, tightly packed sinusoidal vascular channels lined by endothelia that can be found in the brain and spinal cord.1 As a consequence of recurrent bleeding events from these leaky vascular structures, CCM carriers may present with seizures and stroke-like symptoms, ranging from visual impairment to hemiplegia. Autosomal-dominantly inherited CCM (OMIM 116860, 603284, 603285) is associated with heterozygous loss-of-function germline variants in either CCM1 (OMIM: *604214, also known as KRIT1), CCM2 (*607929) or CCM3 (*609118, also known as PDCD10), which can be identified in up to 98% of patients with CCMs and a positive family history.2 3 De novo germline and early postzygotic mutations leading to high-grade mosaicism have only occasionally been reported, although this distinction is crucial for genetic counselling of sporadic CCM cases.4 5 Late postzygotic mutations that are restricted to CCM tissue and can be below the detection level of current routine panel, exome or genome sequencing analyses appear to be one explanation for unsolved sporadic CCM cases, variable expressivity based on multifocality and incomplete penetrance.

Neither the genetic nor the fundamental bio-logical mechanisms that drive CCM development and disease progression have thus far been fully clarified. Decades ago, Rudolf Happle anticipated that mutational events - genetic or epigenetic - could generate new aberrant cell clones that - in case of a lethal mutation - would survive only in close proximity to normal cells, thereby creating characteristic mosaic genodermatoses.6 Happle also predicted that Knudson’s two-hit model of gene inactivation applies to the severe type 2 segmental manifestation of autosomal-dominantly inherited genodermatoses.7 While skin patterns are readily visible and the altered tissue easily accessible, molecular genetic analyses of human cavernous brain tissues remain technically challenging even in the era of next-generation sequencing. The expected allele frequency of a late postzygotic mutation within cavernous lesions is rather low because CCMs are unlike highly proliferating and cellular malignant tumours, blood-filled, often calcified vascular caverns that are typically lined by only a single layer of endothelial cells (ECs). Thus, only little experimental evidence has been published to support a genetic two-step inactivation of CCM1, CCM2 and CCM3 (table 1).8–12 Recent data from two murine models implicate that clonal expansion of ECs after biallelic Ccm3 inactivation initiates cavernoma formation, while incorporation of ECs without a second mutation contributes to their growth.13 14 Lately, a novel human EC culture model specified that CCM3 inactivation results in a survival benefit of functionally impaired ECs that are unable to form spheroids.15

Table 1.

Novel and reported late postzygotic CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3 loss-of-function variants in CCM tissues

| Reference | Gene | Constitutional or high-frequency variant identified in blood and/or CCM tissue* | Late postzygotic variant* | Frequency of the late postzygotic variant (%) | Familial/sporadic CCM | ||

| This report | CCM1 | c.2143-2A>G, p.(Ala715Valfs*14)† | Intron 19 | c.1038C>A, p.(Cys346*) | Exon 12¶ | 5.2– 7.8 | Sporadic |

| 8 | CCM1 | c.1363C>T, p.(Gln455*) (also known as Q455X) |

Exon 14 | c.1465_1498del, p.(Glu489Lysfs*9) | Exon 15§ | 0–21 | Familial |

| 9 | CCM1 | c.1363C>T, p.(Gln455*) | Exon 14 | c.1300del, p.(Val434Leufs*3) | Exon 14§ | 0–4.3 | Sporadic |

| 10 | CCM1 | c.1363C>T, p.(Gln455*) | Exon 14 | c.1271_1274del, p.(Ile424Thrfs*12) (also known as c.1270_1273del) |

Exon 14§ | 11–25 | Unknown |

| 10 | CCM1 | c.1363C>T, p.(Gln455*) | Exon 14 | c.1003G>T, p.(Glu335*) | Exon 12§ | 4–6 | Unknown |

| 10 | CCM2 | Deletion of exons 2–10 | Exons 2–10 | c.55C>T, p.(Arg19*) | Exon 2§ | 6.3–27.5 | Familial |

| 10 | CCM3 | c.474+1G>A, p.? | Intron 7 | c.211dup, p.(Ser71Lysfs*5)‡ (also known as c.205-211insA) |

Exon 5§ | 4.5–10.2 | Familial |

| 11 | CCM1 | c.213_214delinsAT, p.(Tyr71*) (also known as c.213_214CG>AT) |

Exon 6 | c.1890G>A, p.(Trp630*) | Exon 18 | 0–5.3 | Sporadic |

| 11 | CCM1 | None | – | c.993T>G, p.(Tyr331*) and c.1159C>T, p.(Gln387*) |

Exon 12§ Exon 13§ |

3.1–7.2 1.0–6.1 |

Sporadic |

| 11 | CCM1 | None | – | c.1659_1688delinsTAAGCTGATAACATAGTCTG, p.(Leu554Lysfs*5) |

Exon 16 | 0.4–11.9 | Sporadic |

| 11 | CCM1 | None | – | Loss of heterozygosity in a 12–18 kb region (including exons 15–18) |

– | – | Sporadic |

Reference sequences: CCM1: LRG_650t1; CCM2: LRG_664t2; CCM3: LRG_651t1, transcript-specific exon and intron numbering (LRG_650t1 with exons 1–20, LRG_664t2 with exons 1–10, LRG_651t1 with exons 1–9).

*Variants are described according to the recommendations of the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS).

†Constitutional mutation of the index case first reported in Stahl et al.18

‡The postzygotic variant was also detected in an independent tissue sample of a regrown CCM of the index patient.11

§In trans configuration was verified by sequencing of genomic DNA (rather short distance between the two variants) or by cDNA analysis (availability of high-quality RNA samples).

¶An immunohistochemical approach was used to demonstrate endothelial CCM1 inactivation on protein level. Postzygotic inframe and missense variants are listed in online supplementary table 1.

CCM, cerebral cavernous malformation.

jmedgenet-2019-106182supp001.pdf (22.5KB, pdf)

Using an ultra-sensitive sequencing technique, we here report the identification of a novel late postzygotic CCM1 nonsense variant from cavernous tissue of a de novo germline CCM1 mutation carrier. Furthermore, we provide immunohistochemical evidence for EC mosaicism within single caverns of the respective human CCM tissue. Thus, the concept that loss of the second allele results in aberrant EC clones which are more resistant to apoptosis but recruit normal ECs to form cavernous malformations likely also applies to CCM1 and CCM2.

Materials and methods

Samples

DNA was isolated from neutral-buffered formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) CCM tissue slices of three CCM probands using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) was used to measure DNA concentrations on a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Immunohistochemical analyses were performed as described before.12

Molecular analysis

All coding exons and 20 bp of flanking intronic regions of CCM1 (reference sequence: LRG_650t1), CCM2 (LRG_664t2) and CCM3 (LRG_651t1) were defined as target region for single-molecule molecular inversion probe (smMIP)-based ultra-sensitive sequencing. The smMIP design was performed as previously described.16 In brief, each individual smMIP had a target gap fill region of 80 bp and was designed to contain a molecular tag of 2×5 random nucleotides. Sense and antisense DNA strands were targeted with independent smMIPs. Libraries were prepared from 100 ng of genomic DNA with an smMIP to genomic DNA molecule ratio of 800:1 according to established protocols,16 17 pooled and sequenced on a MiSeq instrument with 2×75 cycles (MiSeq Reagent Kit V.3, Illumina, San Diego, California, USA). FASTQ files were generated with the MiSeq Reporter (V.2.5.1.3). The SeqNext module of the Sequence Pilot Software (JSI medical systems, Ettenheim, Germany) was used for read mapping, alignment, consensus read building and variant calling. Sequence alignments were visualised with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (http://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/).

Verification of the late postzygotic CCM1 c.1038=/C>A nonsense variant

A custom Nextera Rapid Capture enrichment panel was used to verify the somatic CCM1 mutation identified in an index case of our previously published cohort.4 12 18 Libaries were pooled and sequenced with 2×150 cycles (MiSeq Reagent Kit V.2., Illumina). Targeted PCR amplicon sequencing from DNA that had been isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes was performed as described before.4

Results

Identification of a novel late postzygotic CCM1 nonsense variant

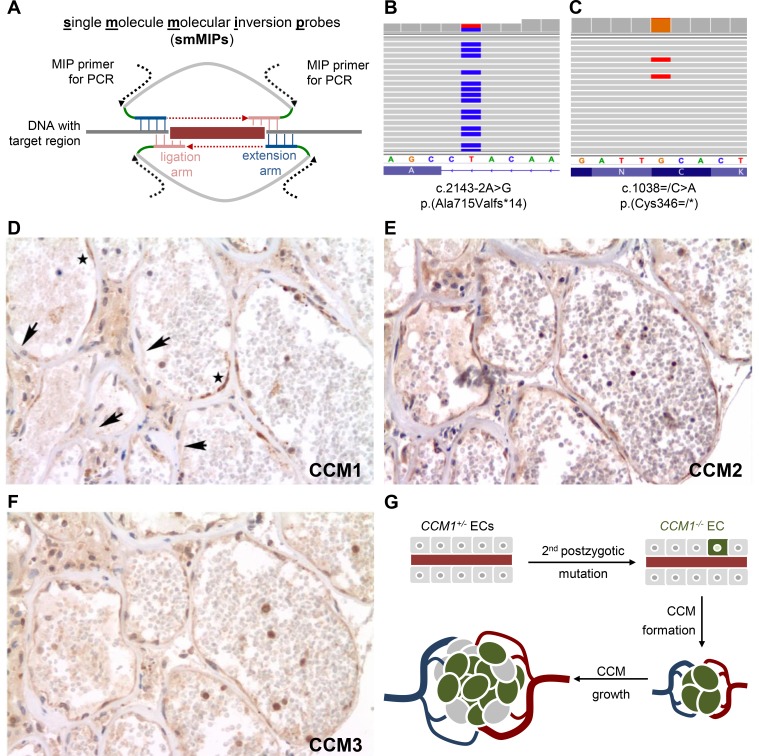

Using ultra-sensitive smMIPs (figure 1A),19 we analysed cavernoma tissues of three CCM probands with known inherited or de novo germline variants. A late postzygotic CCM1 variant was identified in a large cavernoma resected from the right central sulcus of a female proband who had experienced progressive proximal paresis of the left arm at the age of 15 years. Further clinically asymptomatic lesions were documented in both cerebral hemispheres. The proband had previously been shown to be a heterozygous carrier of the CCM1 splice site mutation c.2143-2A>G, p.(Ala715Valfs*14) which was neither detected in her parents nor her dizygotic twin sister.18 Notably, paternity had been confirmed. Later, targeted amplicon deep sequencing analyses with read depths >1 000× did not reveal the mutation as low-level variant in blood-derived DNA samples of any parent.4

Figure 1.

Late postzygotic CCM1 nonsense variant and endothelial cell mosaicism within the cerebral cavernous malformation tissue from a proband with a de novo CCM1 germline mutation. (A) Genomic target regions were enriched and amplified using the smMIP technology. Hybridisation of smMIPs targeting each DNA strand, gap fill, ligation and binding sites for PCR primers are schematically depicted. Molecular tag sequences are marked in green. (B, C) Next generation sequencing analyses verified the heterozygous CCM1 germline mutation (B) and identified a postzygotic CCM1 nonsense variant (C). Endothelia of caverns presented with scattered immunopositivity and immunonegativity for CCM1 (D, arrows indicate negative and asterisks positive immunostaining), while CCM2 (E) and CCM3 (F) were uniformly present in serial sections. (G) Model of clonal evolution of an EC that acquired a second postzygotic mutation (CCM1−/−) and incorporation of ECs with an intact CCM allele (CCM1+/−) into the growing CCM. CCM, cerebral cavernous malformation; ECs, endothelial cells; smMIP, single-molecule molecular inversion probe.

Following target enrichment of DNA isolated from the CCM lesion and deep sequencing, a total of 4 636 019 reads could be mapped and aligned to the coding exons and exon–intron junctions of CCM1, CCM2 and CCM3. Thus, the 4.8 kb-spanning region of interest (ROI) was covered with a mean raw read depth of 35 546×. After consensus read assembly, a mean read depth of 280× was observed and 96% of the ROI was covered with a consensus read depth of >30×. As expected, the heterozygous CCM1 germline mutation in intron 19 was detected in 50% of all consensus reads (126/252) (figure 1B). In addition, a second loss-of-function variant was identified in exon 12 of CCM1 which encodes for parts of the CCM1 ankyrin repeat domain, while no pathogenic variants were found in CCM2 or CCM3.

The novel transversion c.1038C>A leads to a premature termination codon (p.(Cys346*)) and was found in 5.2% of the consensus reads (21/407; figure 1C). As it was covered by two smMIPs that targeted the sense and antisense DNA strand, respectively, the mutation was classified as candidate somatic variant and selected for further analysis. Using an independent target enrichment approach, we verified the c.1038C>A, p.(Cys346*) variant with an next generation sequencing (NGS) read frequency of 7.8% (39/499 reads; online supplementary figure S1) in the CCM tissue sample. As expected, the c.1038C>A substitution was not found in lymphocyte-derived DNA of the index case (0/297 reads; online supplementary figure S1). In accordance with the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines, the late postzygotic CCM1 variant c.1038=/C>A; p.(Cys346=/*) was classified as pathogenic.20

jmedgenet-2019-106182supp002.pdf (118.7KB, pdf)

CCM1 immunostaining demonstrates a mosaic pattern within cavernous endothelia

The genomic distance between the germline variant and the identified late postzygotic mutation was too large (>25.8 kb) to get phase information by short-read sequencing. Since high molecular weight DNA or high-quality RNA could not be obtained from the FFPE sample, ultra-long read sequencing, allele-specific long-range PCR amplification or transcript analyses could not be used to formally confirm the suspected in trans configuration of the two variants on genomic or transcript level.

Therefore, we returned to our established alternative immunohistochemical approach to prove CCM1 inactivation on protein level.12 Notably, endothelia of caverns presented with scattered immunopositivity and immunonegativity for CCM1 in a significant proportion of the endothelial circumference, while CCM2 and CCM3 were uniformly immunopositive (figure 1D–F). In contrast to cavernous ECs, capillaries in the vicinity of the cavernoma demonstrated homogeneous immunopositivity for CCM1, CCM2 and CCM3 (online supplementary figure S2). Taken together, our immunohistochemical approach revealed EC mosaicism in cavernous tissue suggesting an in trans configuration of the postzygotic and germline variant in a higher proportion of ECs than it would have been expected from our NGS data. NGS read frequencies of 5.2%–7.8% indicated that the c.1038C>A; p.(Cys346*) variant was present in 10.4%–15.6% of all cells. Due to the limited material available, however, we could not enrich the endothelial compartment prior to DNA extraction. Thus, DNA from CCM1 +/− non-endothelial stromal cells, neuroectodermal cells, blood leucocytes and macrophages diluted genomic material from the endothelial compartment and thereby led to an under-representation of CCM1−/− ECs in NGS data analyses.

jmedgenet-2019-106182supp003.pdf (41.9KB, pdf)

Discussion

The identification of a postzygotic loss-of-function variant in extended unilateral cavernous tissue associated with the occurrence of disseminated small asymptomatic lesions in both cerebral hemispheres of a teenage germline mutation carrier suggests that CCMs might belong to the list of disorders that may show an equivalent of segmental type 2 manifestations.7 These originate from embryonal loss of the normal allele, show patchy involvement early in life after normal appearance at birth, and develop similar disseminated lesions with progression of variable severity throughout life.

Our data also illustrate that the lining endothelium within human cavernous tissues is not a homogeneous cellular compartment of ECs that all had acquired a second postzygotic loss-of-function variant (CCM1 −/−), but a mosaic of ECs with retained CCM1 expression and with complete CCM1 inactivation. This observation is reminiscent to what has recently been shown in two mouse models for CCM3, in which endothelial mosaicism of mutant and wild-type ECs was observed in expanded lesions.13 14 Similarly, the large cavernoma of our index patient is most likely the product of a clonally expanded CCM1 −/− EC and heterozygous CCM1 +/− ECs (figure 1G). In agreement with our hypothesis of clonal evolution in CCM1 pathogenesis, we have recently shown that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated inactivation of the CCM1 wild-type allele in blood outgrowth endothelial cells (BOECs) of a CCM patient with a heterozygous pathogenic CCM1 germline variant led to a survival advantage for CCM1−/− BOECs in vitro.21 In particular, CCM1−/− BOECs replaced heterozygous CCM1 +/− as well as CRISPR/Cas9-corrected CCM1+/+ BOECs in coculture experiments.21 Additionally, reduced staurosporine-induced Caspase-3 activation in CCM1−/− cells confirmed the conserved role of CCM1 as a positive regulator of apoptotic cell death22 and implicated that its inactivation facilitates the clonal expansion of ECs.21

Since 2005, only a total of seven CCMs that had been resected from five CCM1, one CCM2 and one CCM3 mutation carriers have been reported to harbour a second postzygotic variant (table 1).8–11 Of note, only 4 out of 10 (40%) lesions from carriers of a germline or early postzygotic mutation could be shown to contain a novel biallelic postzygotic variant.10 Similarly, the success rate was 36% (4 out of 11) for surgically resected lesions from patients with sporadic CCM.11 Since non-ECs in the resected CCM tissue reduce the fraction of cells that are expected to harbour an acquired postzygotic mutation, we chose an ultra-sensitive sequencing approach. smMIPs allow extremely accurate variant calling with per-base error rates of 2.6×10−5 and identification of late postzygotic mutations with variant allele frequencies of 0.5% and less.19 However, even with the use of smMIPs, only one out of three tissues analysed revealed a second late postzygotic mutation.

Obviously, our smMIP sequencing approach also has limitations. In particular, its sensitivity may be limited by insufficient quality and quantity of DNA isolated from FFPE tissues since DNA damages can cause artificial errors in single-molecule consensus reads.19 Furthermore, the identification of structural variants (eg, deletions, duplications, inversions or translocations), especially of those in a low-level mosaic state, and of deep-intronic splice mutations remains challenging. Archival FFPE samples will likely also not meet the requirements of new sequencing technologies such as ultra-long read sequencing or single cell genomics. In prospective studies, these techniques might help to answer the question whether a second genomic postzygotic mutation is always necessary for CCM formation or whether epigenetic silencing or non-genetic environmental factors can also trigger CCM development.

Acknowledgments

We thank the affected individuals for their participation in this study and for granting permission to publish this information. K Tominski and H Geißel are thanked for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: UF and MR designed the study. MR performed the sequencing experiments. MR and AH analysed the NGS data. AP performed and analysed the immunohistochemical studies. UF and MR drafted the manuscript, and all authors participated in the final draft revisions.

Funding: This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) - RA 2876/2-1.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Approval from local ethics committees (University of Würzburg: 21/05; Philipps-University Marburg: 149/05; University Medicine Greifswald: BB 047/14) and written informed consent from all study participants were obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Batra S, Lin D, Recinos PF, Zhang J, Rigamonti D. Cavernous malformations: natural history, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2009;5:659–70. 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spiegler S, Rath M, Paperlein C, Felbor U. Cerebral cavernous malformations: an update on prevalence, molecular genetic analyses, and genetic counselling. Mol Syndromol 2018;9:60–9. 10.1159/000486292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akers A, Al-Shahi Salman R, A Awad I, Dahlem K, Flemming K, Hart B, Kim H, Jusue-Torres I, Kondziolka D, Lee C, Morrison L, Rigamonti D, Rebeiz T, Tournier-Lasserve E, Waggoner D, Whitehead K. Synopsis of guidelines for the clinical management of cerebral cavernous malformations: consensus recommendations based on systematic literature review by the angioma alliance scientific Advisory board clinical experts panel. Neurosurgery 2017;80:665–80. 10.1093/neuros/nyx091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rath M, Spiegler S, Nath N, Schwefel K, Di Donato N, Gerber J, Korenke GC, Hellenbroich Y, Hehr U, Gross S, Sure U, Zoll B, Gilberg E, Kaderali L, Felbor U. Constitutional de novo and postzygotic mutations in isolated cases of cerebral cavernous malformations. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2017;5:21–7. 10.1002/mgg3.256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. D'Gama AM, Walsh CA. Somatic mosaicism and neurodevelopmental disease. Nat Neurosci 2018;21:1504–14. 10.1038/s41593-018-0257-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Happle R. Lethal genes surviving by mosaicism: a possible explanation for sporadic birth defects involving the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;16:899–906. 10.1016/S0190-9622(87)80249-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Happle R. The concept of type 2 segmental mosaicism, expanding from dermatology to general medicine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018;32:1075–88. 10.1111/jdv.14838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gault J, Shenkar R, Recksiek P, Awad IA. Biallelic somatic and germ line CCM1 truncating mutations in a cerebral cavernous malformation lesion. Stroke 2005;36:872–4. 10.1161/01.STR.0000157586.20479.fd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gault J, Awad IA, Recksiek P, Shenkar R, Breeze R, Handler M, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Cerebral cavernous malformations: somatic mutations in vascular endothelial cells. Neurosurgery 2009;65:138–44. discussion 44-5 10.1227/01.NEU.0000348049.81121.C1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Akers AL, Johnson E, Steinberg GK, Zabramski JM, Marchuk DA. Biallelic somatic and germline mutations in cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs): evidence for a two-hit mechanism of CCM pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet 2009;18:919–30. 10.1093/hmg/ddn430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McDonald DA, Shi C, Shenkar R, Gallione CJ, Akers AL, Li S, De Castro N, Berg MJ, Corcoran DL, Awad IA, Marchuk DA. Lesions from patients with sporadic cerebral cavernous malformations harbor somatic mutations in the CCM genes: evidence for a common biochemical pathway for CCM pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:4357–70. 10.1093/hmg/ddu153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pagenstecher A, Stahl S, Sure U, Felbor U. A two-hit mechanism causes cerebral cavernous malformations: complete inactivation of CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3 in affected endothelial cells. Hum Mol Genet 2009;18:911–8. 10.1093/hmg/ddn420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Detter MR, Snellings DA, Marchuk DA. Cerebral cavernous malformations develop through clonal expansion of mutant endothelial cells. Circ Res 2018;123:1143–51. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malinverno M, Maderna C, Abu Taha A, Corada M, Orsenigo F, Valentino M, Pisati F, Fusco C, Graziano P, Giannotta M, Yu QC, Zeng YA, Lampugnani MG, Magnusson PU, Dejana E. Endothelial cell clonal expansion in the development of cerebral cavernous malformations. Nat Commun 2019;10:2761 10.1038/s41467-019-10707-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwefel K, Spiegler S, Ameling S, Much CD, Pilz RA, Otto O, Völker U, Felbor U, Rath M. Biallelic CCM3 mutations cause a clonogenic survival advantage and endothelial cell stiffening. J Cell Mol Med 2019;23:1771–83. 10.1111/jcmm.14075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Acuna-Hidalgo R, Sengul H, Steehouwer M, van de Vorst M, Vermeulen SH, Kiemeney LALM, Veltman JA, Gilissen C, Hoischen A. Ultra-Sensitive sequencing identifies high prevalence of clonal Hematopoiesis-Associated mutations throughout adult life. Am J Hum Genet 2017;101:50–64. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eijkelenboom A, Kamping EJ, Kastner-van Raaij AW, Hendriks-Cornelissen SJ, Neveling K, Kuiper RP, Hoischen A, Nelen MR, Ligtenberg MJL, Tops BBJ. Reliable next-generation sequencing of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue using single molecule tags. J Mol Diagn 2016;18:851–63. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stahl S, Gaetzner S, Voss K, Brackertz B, Schleider E, Sürücü O, Kunze E, Netzer C, Korenke C, Finckh U, Habek M, Poljakovic Z, Elbracht M, Rudnik-Schöneborn S, Bertalanffy H, Sure U, Felbor U. Novel CCM1, CCM2, and CCM3 mutations in patients with cerebral cavernous malformations: in-frame deletion in CCM2 prevents formation of a CCM1/CCM2/CCM3 protein complex. Hum Mutat 2008;29:709–17. 10.1002/humu.20712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hiatt JB, Pritchard CC, Salipante SJ, O'Roak BJ, Shendure J. Single molecule molecular inversion probes for targeted, high-accuracy detection of low-frequency variation. Genome Res 2013;23:843–54. 10.1101/gr.147686.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL, Committee A, ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee . Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med 2015;17:405–23. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spiegler S, Rath M, Much CD, Sendtner BS, Felbor U. Precise CCM1 gene correction and inactivation in patient-derived endothelial cells: modeling Knudson's two-hit hypothesis in vitro. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2019;7 10.1002/mgg3.755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ito S, Greiss S, Gartner A, Derry WB. Cell-nonautonomous regulation of C. elegans germ cell death by kri-1. Curr Biol 2010;20:333–8. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jmedgenet-2019-106182supp001.pdf (22.5KB, pdf)

jmedgenet-2019-106182supp002.pdf (118.7KB, pdf)

jmedgenet-2019-106182supp003.pdf (41.9KB, pdf)