Abstract

Objective

To document changes in the clinical features of coeliac disease (CD) at presentation over the last 25 years.

Design

Observational study.

Patients

802 subjects diagnosed between 1993 and 2017 at a single general hospital.

Outcome measures

Date of diagnosis, age, sex, postcode, symptoms, haematinic deficiency, smoking status, serology, family history and autoimmune phenomena.

Results

The incidence of diagnosed CD rose threefold during the course of the study, with a rising prevalence of positive coeliac serology and positive family history of CD, and a falling prevalence of symptoms and haematinic deficiencies. There was little change in the female predominance, age at diagnosis or high prevalence of other autoimmune conditions over the 25 years, and a paucity throughout of cigarette smokers, particularly heavy smokers. A cohort of patients with seronegative CD was identified who shared many of the characteristics of seropositive CD, but with a significantly older age at diagnosis and a higher prevalence of cigarette smokers.

Conclusion

There have been major changes in the epidemiology of CD over the last 25 years, of relevance to both our understanding of the aetiopathogenesis of CD and the requirement for service provision. The implications are discussed.

Keywords: coeliac disease, epidemiology

Summary box.

What is already known about this subject?

The incidence of diagnosed coeliac disease (CD) has risen over recent years.

What are the new findings?

A threefold increase in the incidence of diagnosed CD over the last 25 years, with a rising prevalence of positive coeliac serology, a falling prevalence of symptoms and haematinic deficiencies, and little change in age at diagnosis. Throughout there was a paucity of cigarette smokers, particularly heavy smokers. A distinct sub-group with seronegative CD was characterised.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

These findings have implications for our understanding of the aetiopathogenesis of CD, and for the service provision for diagnosed cases.

Introduction

Coeliac disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the small bowel resulting from mucosal exposure to dietary gluten in genetically predisposed individuals. Evidence implicating the immune system in the inflammatory response in CD includes the strong link with HLA-DQ alleles, the association with other autoimmune disorders and the frequent finding of anti-endomysial (EMA) and anti-gliadin antibodies (AGA) in untreated CD.1 2 Despite this array of observations, the aetiopathogenesis of CD remains incompletely understood.

The clinical presentation of CD is broad, ranging from a classical presentation with weight loss and malabsorption at one end of the spectrum to an incidental finding in an asymptomatic individual at the other.1 2 Population-based studies suggest an overall seroprevalence of CD in gluten-exposed populations of about 1%.1–3 However, the demonstration by screening studies that the majority of cases of CD are never diagnosed has led to the concept of a ‘coeliac iceberg’, with the submerged component representing the atypical and silent forms of the disease.4

Over recent years some inroads have been made in identifying these cases. Contributory factors include increased awareness of the condition in the community and primary care, and serological testing of high-risk groups and of subjects with non-specific or atypical symptoms. Changes in the epidemiology of CD might be expected as a consequence.

The aim of this study is to assess changing patterns in the epidemiology of diagnosed CD in a defined population, and to discuss the potential relevance of these observations for the aetiopathogenesis of CD.

Method

Poole Hospital is a district general hospital in Southern England, with a catchment population of about 250 000. The gastroenterology unit has maintained a prospective register of all incident cases of CD diagnosed since 1 January 1993, for the purposes of clinical follow-up, audit and service assessment. Cases were identified from a range of sources including endoscopy and histopathology records, gastroenterology and paediatric clinics, and a dedicated coeliac clinic.

In all cases the diagnosis was based on the combination of clinical, serological and histological features. Characteristic morphology on small bowel biopsy histology was an absolute requirement, with the exception of paediatric cases following adoption of the 2012 European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) criteria.5 In the minority of cases where there was a degree of diagnostic uncertainty, confirmation of the diagnosis was based on the decision of the responsible clinician. A follow-up biopsy was not considered mandatory unless there was diagnostic uncertainty.

Importantly, positive coeliac serology was not an absolute diagnostic requirement. Some patients underwent small bowel biopsy without prior serological testing – for example, those undergoing gastroscopy for iron deficiency or unexplained weight loss. Cases with negative serology still underwent biopsy if there was sufficient clinical suspicion.

This report is based on analysis of data collected for all cases diagnosed with CD between 1.1.93 and 31.12.17. The recorded information was as relevant on the date of diagnosis, and included:

Demographic data: diagnosis date, age, sex, postcode (outward code).

Clinical features: symptoms, CD family history, concurrent autoimmune disease, smoking status.

Laboratory results: concentrations of haemoglobin and IgA, coeliac serology (test type and titre).

Information was unavailable for smoking status in three cases (0.4%), haemoglobin concentration in 37 cases (4.6%) and coeliac serology in 46 cases (5.7%). Limited statistical analysis was undertaken as described below. This study adheres to the Oslo definitions for CD and related terms.

Results

Population characteristics

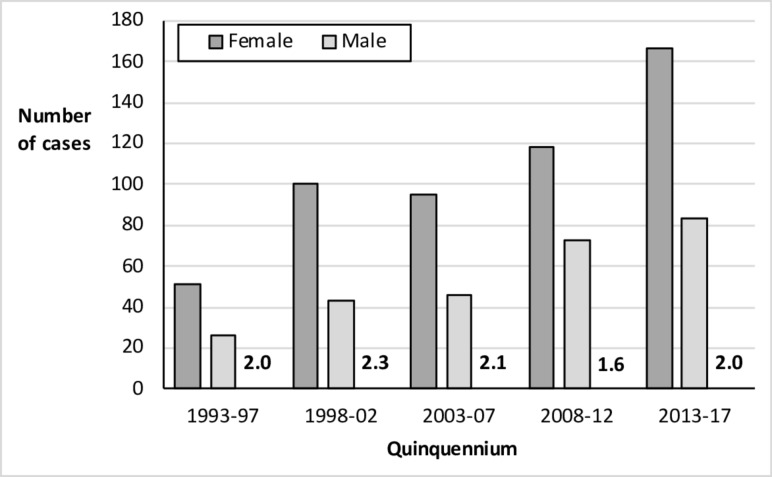

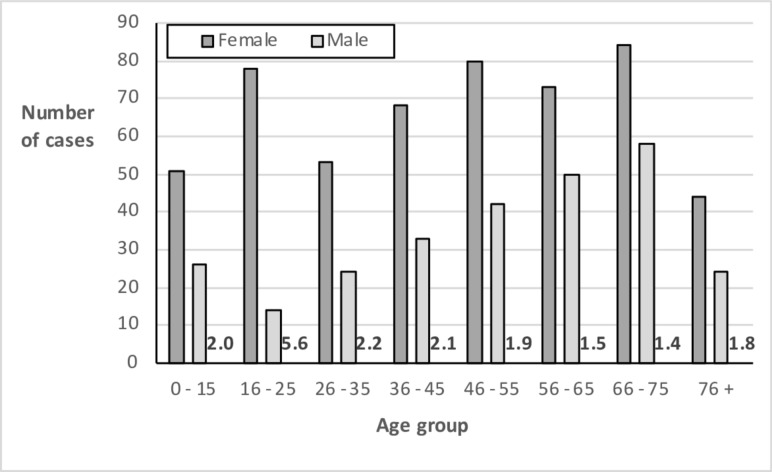

A total of 802 cases were diagnosed over the 25 year study period, with an overall median age at diagnosis of 50 (IQR 29–66) - 36% of incident cases were over the age of 60. The crude incidence of CD rose progressively over the years (figure 1). Assuming a catchment population of 250 000, this corresponds to incidence figures of 6.2 per 100 000 pa in the first quinquennium and 20.0 in the last. The overall female to male case ratio was 2.0—this was consistent throughout the study period (figure 1) but it did vary with age, with the highest proportion of females (F/M=5.6) in the 16–25 age group (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Crude annual incidence of coeliac disease by sex and quinquennium, with F/M sex ratio in numerals.

Figure 2.

Crude incidence of coeliac disease by sex and age-group, with F/M sex ratio in numerals.

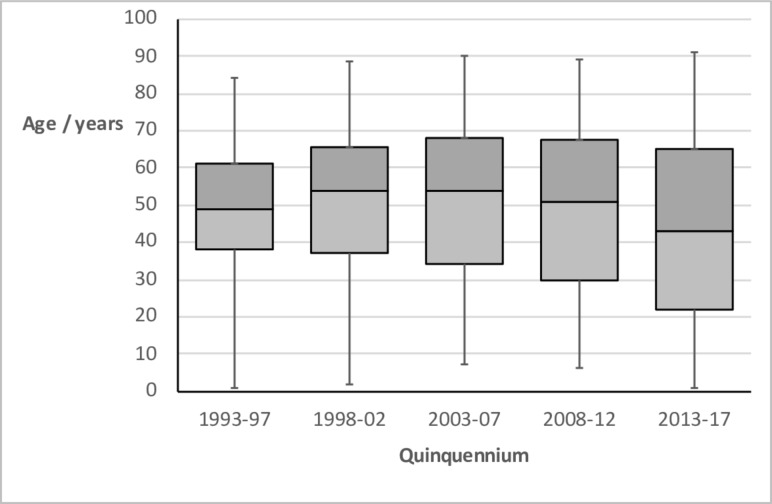

There was little change in the median age at diagnosis over the study period (figure 3), other than a slight fall in the final quinquennium (p<0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test) largely due to a surge of paediatric cases following adoption of the 2012 ESPGHAN criteria.5 There was no significant association between disease incidence and either month of birth or month of diagnosis.

Figure 3.

Box and whisker plot of age at diagnosis of coeliac disease by quinquennium, showing minimum, median and maximum values, and IQR

The incidence of CD by year was assessed for three representative postcode-based areas well within the hospital catchment area. The outward codes (with population size in brackets, derived from 2011 census data) were BH21 (40571), BH14 +BH15 (56484) and BH17 +BH18 (34111). The findings provided some evidence of clustering in time and space, with a striking and statistically significant peak in for BH21 in 2002 as previously reported6 and one of similar magnitude for BH17/18 in 2014.

Clinical features

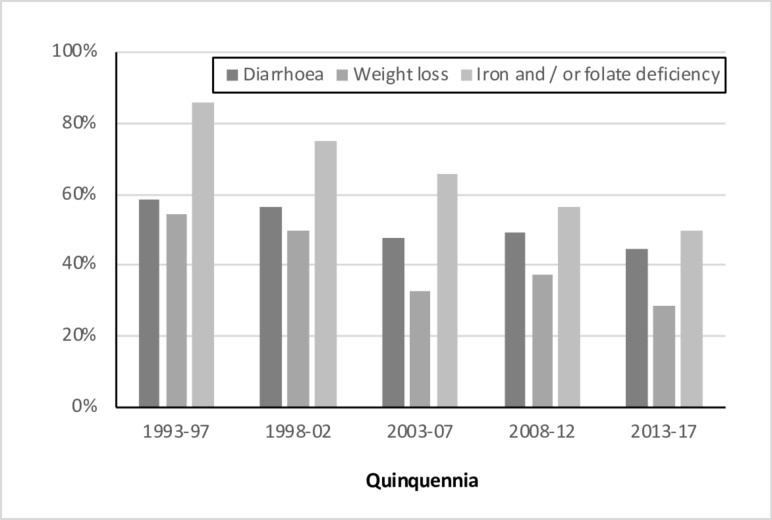

The proportion of subjects with diarrhoea, weight loss or haematinic deficiency at presentation fell progressively over the study period (figure 4). For example, the proportion with evidence of haematinic deficiency fell from 86% in 1993-1998 to 50% in 2012–2017. Mirroring these changes, the median haemoglobin concentration at diagnosis rose progressively—57% diagnosed in the first quinquennia had a figure of less than 120 g/L (the lower limit of normal), compared with 24% in the last.

Figure 4.

The percentage of cases presenting with each clinical feature, by quinquennium.

The proportion of cases reporting an affected first or second degree relative rose from 9.1% in 1993-1998 to 22.4% in 2012–2017. A family history was most common in those under the age of 25, reported by 29.0%. The overall prevalence of other autoimmune disorders (excluding dermatitis herpetiformis) at the time of diagnosis was 17.6%, with no consistent trend over the study period. The majority of these associations were accounted for by autoimmune thyroid disease and type 1 diabetes.

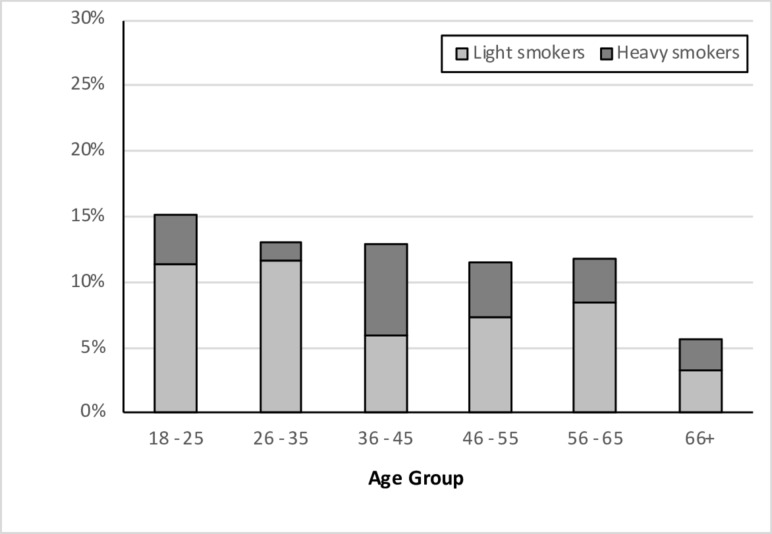

As might be anticipated from trends in the general population,7 there was a gradual fall in the percentage of current smokers and rise in the percentage of never smokers over the duration of the study, along with a relationship between smoking status and age. The striking finding throughout however was the relative paucity of current smokers, and in particular current heavy smokers, in all age groups (figure 5)—regardless of whether compared with published national or regional smoking data. For example, Office for National Statistics data for 2005 (the mid-point year of the study) reveals national prevalence figures for cigarette smoking in adults up to the age of 60 of 24%–31%, with most individuals falling into the heavy smoker category.7 In contrast, our coeliac dataset reveals that less than 15% were smokers at diagnosis—and the majority of these were light smokers.

Figure 5.

The percentage of current smokers at diagnosis by age-group, sub-divided by cigarette usage : light (>1–10/day) or heavy (>10/day).

Coeliac serology

Results for coeliac serology prior to the introduction of a gluten-free diet were available for 756 cases (94%). The test undertaken evolved from AGA in the early years through endomysial antibody (EMA) to tissue transglutaminase antibody (tTGAb), making direct comparison difficult. However, a consistent feature throughout the study period was the presence of a minority of diagnosed coeliacs with negative serology. Overall, 76 of 756 cases (10.1%) were negative for the serological test(s) available at the time, and selective IgA deficiency accounted for just 10 (13.9%) of the 72 seronegative cases tested.

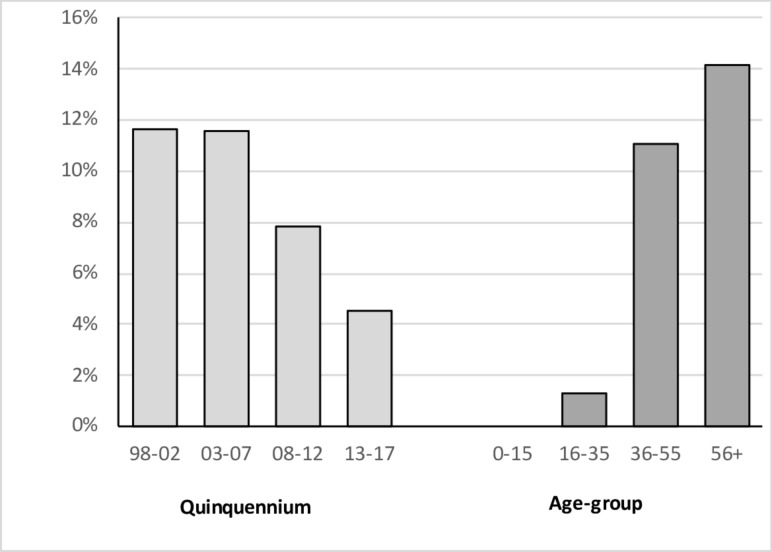

Figure 6 and table 1 show the results of a more detailed subgroup analysis, arbitrarily defining seronegative CD as a characteristic clinical and histological picture in the face of negative EMA/tTGAb serology and normal levels of IgA. By this definition the prevalence of seronegativity was 9.1%—the figure fell during the study period but was still 4.5% in the final quinquennium. There was a strong relationship between seronegative status and age. Seropositive and seronegative subjects shared a number of characteristics, including sex ratio and a substantially increased prevalence of a family history of CD and other autoimmune disorders. However, seronegative subjects were significantly older (p<0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test), and more likely to be cigarette smokers (p<0.03, χ2 test).

Figure 6.

Percentage of seronegative cases by (A) quinquennium and (B) age-group—see text for definition of seronegativity.

Table 1.

Comparison of the clinical characteristics of seronegative and seropositive subjects—see text for definition of seronegativity)

| Coeliac serology | |||

| Negative | Positive | P value | |

| Number | 66 | 660 | – |

| Sex ratio (F/M) | 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.85 |

| Family history of coeliac disease | 9.1% | 20.0% | < 0.05 |

| Other autoimmune condition(s) | 22.7% | 17.4% | 0.37 |

| Cigarette smokers* | 19.7% | 9.8% | < 0.03 |

| Median age (IQR)/years | 63 (50–73) | 48 (26–65) | < 0.0001 |

*Cigarette smoking analysis relates to subjects over the age of 17.

In an attempt to estimate the true prevalence of seronegative CD as a percentage of the total, a subgroup of adults diagnosed with CD through our iron deficiency anaemia service was analysed. This eliminated verification bias, as coeliac serology in this cohort was not checked until after the histological diagnosis was made (but before gluten withdrawal). Of 53 cases, 14 (26%) were seronegative by the definition above.

Discussion

As a single-centre cohort study, our report has the strength of uniformity of diagnostic approach, and the weakness of uncertain applicability to other populations. Nevertheless, figures for the absolute incidence of diagnosed CD over the last 25 years in this study are remarkably consistent with recent large population studies from the UK and Denmark.8–10 While the true incidence of CD may be increasing,2 it is likely that the striking threefold increase in the incidence of diagnosed CD over the study period predominantly reflects increased case ascertainment—fitting with the concept of the coeliac iceberg.1 4 6 The observations of a falling percentage with symptoms, haematinic deficiency and/or anaemia at diagnosis would support the notion that CD is increasingly being diagnosed at an earlier and/or milder stage in the disease course.

There are a number of plausible explanations for this, including greater disease awareness among primary care physicians and the general public, adoption of the ESPAGHAN criteria in paediatric practice, systematic screening of at-risk groups such as type 1 diabetics and increasing sensitivity of serological screening tests for CD. Furthermore, serological screening of individuals with non-specific presentations has dramatically risen—annual requests to our local laboratory for coeliac serology testing has risen from less than 1000 in the early 1990s to over 14 000 since 2015, a figure far in excess of the number of diagnosed cases.

The female predominance of diagnosed CD is well established, and our findings confirm that this is particularly marked among young adults.9 This might perhaps reflect hormonal influences on the disease process. In keeping with this, the sex ratio approximates to unity over the age of 55 when corrected for the excess of females in the population of this age. Seroprevalence studies of unselected adults however do not reveal a sex predominance for undiagnosed CD, and therefore the observation for diagnosed CD may simply reflect well-recognised differences between the sexes in terms of utilisation of healthcare.11 12

Our findings confirm previous observations relating to smoking and the risk of CD, with a paucity of cigarette smokers—in particular heavy smokers—in the coeliac population.13–16 The magnitude of risk reduction depends on the comparator population but holds for both local and national published statistics.7 We need to consider the possibility of ascertainment bias in the collection of smoking data from our patient population. However, this is certainly not what we find in smoking related conditions such as Crohn’s disease, and this explanation does not fit with the substantially reduced prevalence of current smokers in undiagnosed seropositive populations.12 The alternative interpretation is that smoking may protect against the development of CD, in a dose-related fashion.17 This is perhaps not so surprising, given the range of other autoimmune disorders which in one way or another relate to smoking status.18

The existence of seronegative CD is well established,1 2 with only a minority of cases due to selective IgA deficiency.19–21 It is however unclear exactly how common this is. Figures in the literature are rather variable, probably because of varying degrees of verification bias. Understandably, seropositive subjects are more likely to acquire a diagnosis of CD than their seronegative counterparts. Our data would suggest that up to 26% of coeliacs may be seronegative, and perhaps higher still in the elderly population.

The criticism could be levelled that seronegative subjects do not actually have CD at all. Careful resolution of the differential, including confirmation of a histological response to gluten withdrawal, is certainly important in this sub-group.21 Our data support the existence of seronegative CD on the grounds that this sub-group shares a number of characteristics with the seropositive subgroup. These include gluten-driven histological changes, sex ratio and prevalence figures for other autoimmune disorders and a family history of CD (table 1) that are far higher than found in the general population.10 To this can be added the high prevalence of HLA DQ2 in seronegative CD.19–21

The higher prevalence of other autoimmune conditions and lower prevalence of a family history in seronegative CD may simply be because this group are significantly older than the seropositive subgroup. What is more difficult to explain, particularly given the fall in the prevalence of smoking with age in the general population, is the much higher prevalence of current smokers in the seronegative subgroup. The implication is that smoking status specifically relates to the risk of seropositive CD.

A number of factors are likely to have contributed to the falling proportion of coeliacs who are seronegative at diagnosis over the last 25 years. These include increasing sensitivity of the serological tests employed, and rising verification bias given the increasing use of serological testing—particularly in individuals with symptoms that are unlikely to be due to CD, or with no symptoms at all.

It is interesting that although the two major recognised prerequisites for the development of CD–HLA genes and gluten—are present from an early age, the median age at diagnosis in this cases series was 50 years. The explanation for this might be that CD is a lifelong condition that defies diagnosis for decades—and certainly delayed diagnosis is well recognised.1 22 However, if this were the case one might predict a marked fall in the age at diagnosis over the study period, given the rapidly rising incidence of CD and the marked trend towards ‘earlier’ diagnosis outlined above.

In reality, there has been little change in the median age at diagnosis over the study period (figure 3), with just a slight fall in the final quinquennium following adoption of the ESPGHAN criteria. The implication is that CD is an acquired condition requiring not only the appropriate HLA genotype and gluten exposure, but also an additional environmental trigger or triggers. This would fit with a number of other observations including the acquired nature of most other HLA-related autoimmune disorders,18 the exposure-related association with cigarette smoking,17 the incomplete concordance for CD in monozygotic twins,23 and the evidence that only a minority of individuals with the high-risk genotype develop CD.24

The nature of the environmental trigger(s) remains a matter for speculation. However, the evidence of clustering in time and/or space6 8 10 25 supports the suspicion of an infective event, and fits with other evidence implicating viral infection as the trigger in genetically predisposed individuals.26 27

In conclusion, the epidemiology of CD is changing, with a rapidly rising incidence of diagnosed CD and a trend towards diagnosis at an ‘earlier’ stage in the disease course. This is likely to relate at least in part to improving case ascertainment, though a true rise in incidence as observed in some other autoimmune conditions may also be contributing. These changes are likely to impact on healthcare provision, with increasing demand for diagnostic and management services.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Mark Tighe for help with data collection, and to Professor Duncan Colin-Jones and Dr Nicholas Sharer for their critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was devised by IKW and JAS, data collection was by DSN, SK and SLS, and the report was written by CS, OAM and JAS. All authors approved the final draft, and the guarantor is JAS.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Hopper AD, Hadjivassiliou M, Butt S, et al. Adult coeliac disease. BMJ 2007;335:558–62. 10.1136/bmj.39316.442338.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lebwohl B, Sanders DS. Green PHR coeliac disease. Lancet 2018;391:70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dubé C, Rostom A, Sy R, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in average-risk and at-risk Western European populations: a systematic review. Gastroenterology 2005;128:S57–67. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Catassi C, Rätsch I-M, Fabiani E, et al. Coeliac disease in the year 2000: exploring the iceberg. The Lancet 1994;343:200–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90989-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, et al. European Society for pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;54:136–60. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821a23d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fowell AJ, Thomas PW, Surgenor SL, et al. The epidemiology of coeliac disease in East Dorset 1993-2002: an assessment of the 'coeliac iceberg', and preliminary evidence of case clustering. QJM 2006;99:453–60. 10.1093/qjmed/hcl061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Office for National Statistics Adult smoking habits in Great Britain. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/drugusealcoholandsmoking/datasets/adultsmokinghabitsingreatbritain [Accessed Nov 2018].

- 8. West J, Fleming KM, Tata LJ, et al. Incidence and prevalence of celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis in the UK over two decades: population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:757–68. 10.1038/ajg.2014.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Holmes GKT. Muirhead a epidemiology of coeliac disease in a single centre in southern Derbyshire 1958–2014. BMJ Open Access Gastroenterology 2017;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grode L, Bech BH, Jensen TM, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and autoimmune comorbidities of celiac disease: a nationwide, population-based study in Denmark from 1977 to 2016. EJGH 2018;30:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McMillan SA, Watson RP, McCrum EE, et al. Factors associated with serum antibodies to reticulin, endomysium, and gliadin in an adult population. Gut 1996;39:43–7. 10.1136/gut.39.1.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. West J, et al. Seroprevalence, correlates, and characteristics of undetected coeliac disease in England. Gut 2003;52:960–5. 10.1136/gut.52.7.960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Snook JA, Dwyer L, Lee-Elliott C, et al. Adult coeliac disease and cigarette smoking. Gut 1996;39:60–2. 10.1136/gut.39.1.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vazquez H, Smecuol E, Flores D, et al. Relation between cigarette smoking and celiac disease: evidence from a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:798–802. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03625.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Todi D, Tsai HH. Coeliac disease is associated with non-smoking and cessation of smoking. Gut 1997;40(suppl 1). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Austin AS, Logan RFA, Thomason K, et al. Cigarette smoking and adult coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;37:978–82. 10.1080/003655202760230973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Suman S, Williams EJ, Thomas PW, et al. Is the risk of adult coeliac disease causally related to cigarette exposure? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;15:995–1000. 10.1097/00042737-200309000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Costenbader KH, Karlson EW. Cigarette smoking and autoimmune disease: what can we learn from epidemiology? Lupus 2006;15:737–45. 10.1177/0961203306069344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boger CPC, Thomas PW, Nicholas DS, et al. Determinants of endomysial antibody status in untreated coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;19:890–5. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282eeb472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Salmi TT, Collin P, Korponay-Szabó IR, et al. Endomysial antibody-negative coeliac disease: clinical characteristics and intestinal autoantibody deposits. Gut 2006;55:1746–53. 10.1136/gut.2005.071514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aziz I, Peerally MF, Barnes J-H, et al. The clinical and phenotypical assessment of seronegative villous atrophy; a prospective UK centre experience evaluating 200 adult cases over a 15-year period (2000-2015). Gut 2017;66:1563–72. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vavricka SR, Vadasz N, Stotz M, et al. Celiac disease diagnosis still significantly delayed - Doctor's but not patients' delay responsive for the increased total delay in women. Dig Liver Dis 2016;48:1148–54. 10.1016/j.dld.2016.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuja-Halkola R, Lebwohl B, Halfvarson J, et al. Heritability of non-HLA genetics in coeliac disease: a population-based study in 107 000 twins. Gut 2016;65:1793–8. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pietzak MM, Schofield TC, McGinniss MJ, et al. Stratifying risk for celiac disease in a large at-risk United States population by using HLA alleles. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:966–71. 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olsson C, Stenlund H, Hörnell A, et al. Regional variation in celiac disease risk within Sweden revealed by the nationwide prospective incidence register. Acta Paediatica 2009;98:337–42. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stene LC, Honeyman MC, Hoffenberg EJ, et al. Rotavirus infection frequency and risk of celiac disease autoimmunity in early childhood: a longitudinal study. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:2333–40. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00741.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bouziat R, Hinterleitner R, Brown JJ, et al. Reovirus infection triggers inflammatory responses to dietary antigens and development of celiac disease. Science 2017;356:44–50. 10.1126/science.aah5298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]