Abstract

Background

Physiological responses of the fetus (especially increase in heart rate) to single, brief bouts of maternal exercise have been documented frequently. Many pregnant women wish to engage in aerobic exercise during pregnancy, but are concerned about possible adverse effects on the outcome of pregnancy.

Objectives

To assess the effects of advising healthy pregnant women to engage in regular aerobic exercise (at least two to three times per week), or to increase or reduce the intensity, duration, or frequency of such exercise, on physical fitness, the course of labour and delivery, and the outcome of pregnancy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (31 August 2009), MEDLINE (1966 to August 2009), EMBASE (1980 to August 2009), Conference Papers Index (earliest to August 2009), contacted researchers in the field and searched reference lists of retrieved articles.

Selection criteria

Acceptably controlled trials of prescribed exercise programs in healthy pregnant women.

Data collection and analysis

Both review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. We contacted study authors for additional information.

Main results

We included 14 trials involving 1014 women. The trials were small and not of high methodologic quality. Of the nine trials reporting on physical fitness, six reported significant improvement in physical fitness in the exercise group, although inconsistencies in summary statistics and measures used to assess fitness prevented quantitative pooling of results. Eleven trials reported on pregnancy outcomes. A pooled increased risk of preterm birth (risk ratio 1.82, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.35 to 9.57) with exercise, albeit statistically non‐significant, does not cohere with the absence of effect on mean gestational age (mean difference +0.10, 95% CI ‐0.11 to +0.30 weeks), while the results bearing on growth of the fetus are inconsistent. One small trial reported that physically fit women who increased the duration of exercise bouts in early pregnancy and then reduced that duration in later pregnancy gave birth to larger infants with larger placentas.

Authors' conclusions

Regular aerobic exercise during pregnancy appears to improve (or maintain) physical fitness. Available data are insufficient to infer important risks or benefits for the mother or infant. Larger and better trials are needed before confident recommendations can be made about the benefits and risk of aerobic exercise in pregnancy.

Plain language summary

Aerobic exercise for women during pregnancy

Regular aerobic exercise during pregnancy appears to improve physical fitness, but the evidence is insufficient to infer important risks or benefits for the mother or baby.

Aerobic exercise is physical activity that stimulates a person's breathing and blood circulation. The review of 14 trials, involving 1014 pregnant women, found that pregnant women who engage in vigorous exercise at least two to three times per week improve (or maintain) their physical fitness, and there is some evidence that these women have pregnancies of the same duration as those who maintain their usual activities. There is too little evidence from trials to show whether there are other effects on the woman and her baby. The trials reviewed included non‐contact exercise such as swimming, static cycling and general floor exercise programs. Most of the trials were small and of insufficient methodologic quality, and larger, better trials are needed before confident recommendations can be made about the benefits and risks of aerobic exercise in pregnancy.

Background

Physically demanding work during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of preterm birth (Henriksen 1995; Mamelle 1984; Mozurkewich 2000; Saurel 2004), prolonged labour (Magann 2002), and reduced fetal growth (Perkins 2007) in some observational studies. Moreover, numerous reports (Brenner 1999; Clapp 1993; Hatoum 1997; Pijpers 1984; Veille 1985) have documented fetal physiological responses (especially increase in the fetal heart rate) to single, brief bouts of maternal exercise. The impact of prolonged and repeated aerobic exercise on outcomes of clinical importance for mothers and infants is unknown, however. Two published meta‐analyses (Leet 2003; Lokey 1991) and a narrative review (Dye 2003) have attempted to summarize the evidence but included observational studies as well as randomized trials. The 2000 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a national population health survey in the United States, the most common leisure‐time physical activities during pregnancy included walking, swimming, and aerobics (Evenson 2004). Given the important health benefits of regular physical activity (e.g., reduced blood pressure, improved well‐being) for non‐pregnant women (Manson 1999), many pregnant women may wish to continue exercising during pregnancy. Evidence‐based recommendations for exercise during pregnancy are therefore important.

Objectives

To assess the effects of advising healthy pregnant women to engage in regular (at least two to three times per week) aerobic exercise, or to increase or reduce the intensity, duration, or frequency of such exercise, on physical fitness, on the course of labour and delivery, and on the outcome of pregnancy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomized and quasi‐randomized trials of prescribed aerobic exercise programmes.

Types of participants

Healthy pregnant women.

Types of interventions

Increase or reduction in regular aerobic exercise. We excluded trials with low frequency or duration of prescribed aerobic exercise (e.g., fewer than two sessions and/or lasting no more than 30 minutes per week), or both.

Types of outcome measures

Outcome measures included: change in level of maternal physical fitness and anthropometric measures; maternal outcomes of pregnancy such as pre‐eclampsia, duration of labour, and type of delivery; and fetal and infant outcomes, or both, such as gestational age, birthweight, birth length, stillbirth, preterm birth, and small‐for‐gestational‐age birth.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (31 August 2009).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

In addition, we searched MEDLINE (1966 to August 2009), EMBASE (1980 to August 2009) and Conference Papers Index (earliest to August 2009) using the search strategies detailed in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We attempted to contact the authors of all studies identified to obtain additional references and unpublished data. In the case of abstracts only, we attempted to find associated papers, if they existed, in either published or unpublished format. We also searched reference lists of retrieved articles. We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 2.

For this update we used the following methods when assessing the trials identified by the updated search (Aittasalo 2008; Barakat 2008; Callaway 2008; Granath 2006; Haakstad 2008; Hofman 2005; Hui 2006; Ko 2008; McAuley 2005; McDonald 2001; Memari 2006; Morkved 2007; Oostdam 2009; Quinlivan 2007; Santos 2005; Satyapriya 2009; Yeo 2008) as well as the study that was already awaiting classification (Lee 1996).

Selection of studies

The two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreements through discussion.

Data extraction and management

For eligible studies, the two review authors extracted the data independently by entering them into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We resolved discrepancies through discussion and checked all data for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

One of the authors (SW McDonald) assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008); the other author (MS Kramer) then reviewed and approved these assessments .

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We describe for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

adequate (any truly random process, e.g., random number table; computer random number generator);

inadequate (any non‐random process, e.g., odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We describe for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We judged studies at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate, inadequate or unclear for participants;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for personnel;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We describe for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We state whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information is reported, or can be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertake. We assessed methods as:

adequate;

inadequate:

unclear.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We describe for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

inadequate (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

(6) Other sources of bias

We describe for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

yes;

no;

unclear.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We make explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2008). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it is likely to impact on the findings.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we present results as summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we use the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials.

Unit of analysis issues

All included studies are based on randomization of individual participants.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we note levels of attrition.

For all outcomes we have carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempt to include all participants randomized to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial the number randomized minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We use the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspect reporting bias (see ‘Selective reporting bias’ above), we have attempted to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data.

Data synthesis

We carry out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We use fixed‐effect inverse variance meta‐analysis for combining data where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. We have used random‐effects models to pool results when I² is greater than 50%.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not undertake any subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not undertake any sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

We identified 30 trials.

Included studies

We included 14 trials (Bell 2000; Carpenter 1990; Clapp 2000; Clapp 2002; Collings 1983; Erkkola 1976; Lee 1996; Marquez 2000; Memari 2006; Prevedel 2003; Santos 2005; Sibley 1981; South‐Paul 1988; Wolfe 1999). SeeCharacteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded 16 trials (Aittasalo 2008; Asbee 2009; Barakat 2008; Callaway 2008; Granath 2006; Hui 2006; Kihlstrand 1999; Kulpa 1987; Lawani 2003; McAuley 2005; McDonald 2001; Polley 2002; Quinlivan 2007; Satyapriya 2009; Varrassi 1989; Yeo 2008). SeeCharacteristics of excluded studies for details.

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, the trials are quite small, and none are of high methodologic quality. In most of the trials, the method of treatment allocation was either by alternation or was not described. Most did not specify the number of women originally allocated and the numbers of, and reasons for, losses to follow up. Very few provided data on compliance with the prescribed exercise program, and three excluded non‐compliers from the analysis. Those studies excluding non‐compliers also excluded women developing obstetric contraindications (e.g., bleeding, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth). These exclusions did not appear to have substantially biased the overall results, however. Nor did we identify other sources of bias in any of the included studies that could impact results apart from those already mentioned.

Effects of interventions

Carpenter 1990; Collings 1983; Erkkola 1976; Marquez 2000; Prevedel 2003 and Santos 2005 all reported significant improvement in physical fitness in sedentary women who increased their exercise during pregnancy. South‐Paul 1988 reported similar, albeit statistically non‐significant, findings, while the even smaller Sibley 1981 trial reported no significant increase in fitness in the exercise group. Inconsistency in the measures used to measure physical fitness across studies (e.g., aerobic capacity, cardiopulmonary measures, or physical work capacity) and the absence of 'change' data made it difficult to statistically combine the results on physical fitness.

Results on pregnancy outcomes in the above trials are limited to Bell 2000; Clapp 2000; Clapp 2002; Collings 1983; Erkkola 1976; Lee 1996; Marquez 2000; Memari 2006; Prevedel 2003 and Santos 2005. As shown by the wide confidence intervals, the small size of these trials permits exclusion of only extremely large effects for most of the reported outcomes. Increasing exercise in sedentary women had no significant effect on mean birthweight (mean difference (MD) +49.49, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐27.74 to +126.73 g). The data are somewhat reassuring (albeit based only on two small trials) that increasing exercise in sedentary women does not result in a clinically important shortening of gestation (MD +0.10, 95% CI ‐0.11 to +0.30 weeks). Despite that result, increasing exercise was associated with a non‐significant increase in the risk of preterm birth (risk ratio (RR) 1.82, 95% CI 0.35 to 9.57). No significant effects were observed on mean five‐minute Apgar score (MD 0.15, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.39) or on risk of cesarean delivery (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.53). Data on stillbirth, neonatal death, pre‐eclampsia, and cesarean section are limited to one or two trials each, with small sample sizes and hence inconclusive results.

Other than outcomes related to maternal physical fitness, consistency of results across these trials is evaluable for preterm birth, cesarean delivery, gestational (maternal) weight gain, gestational age, birthweight, and five‐minute Apgar score, each of which was reported by at least three trials. Within these limits and those imposed by small sample sizes, the results appear reasonably consistent except perhaps for five‐minute Apgar score. Because of the small sample sizes and other methodologic limitations of the reported trials, however, heterogeneity is difficult to assess. Despite not contributing quantitative data for pooling, the results by Wolfe 1999 are in line with those already described.

The single trial (Bell 2000) investigating the effects of reducing high‐frequency (at least five times per week) to lower‐frequency (no more than three times per week) aerobic exercise is too small to make confident inferences about the benefits or risks of such a reduction.

One small trial (Clapp 2002) reported that physically fit women who increased the duration of their exercise bouts in early pregnancy, then reduced the duration in later pregnancy ('Hi‐Lo' pattern), gave birth to much larger infants (difference in mean birthweight 460.00, 95% CI 251.63 to 668.37 g) with larger placentas than control women who maintained a moderate exercise duration throughout gestation. Women with the opposite pattern ('Lo‐Hi') had similar outcomes to those in the control group.

One small trial (Santos 2005) in overweight women (body mass index 25 to 30 kg/m2) found no significant difference in risk of preterm birth (RR 1.89, 95% CI 0.18 to 19.95) or mean birthweight (MD ‐5.00, 95% CI ‐241.27 to +231.27 g) associated with the intervention.

Discussion

Regular exercise during pregnancy appears to improve (or maintain) physical fitness. The available data are insufficient to infer other important risks or benefits for the mother or infant.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Regular exercise during pregnancy appears to improve (or maintain) physical fitness. Unfortunately, the available data are insufficient to infer important risks or benefits for the mother or infant.

Implications for research.

Future trials will require much larger sample sizes to detect potential effects on maternal and infant health. The suggestion that regular exercise may increase the risk of preterm birth (despite its inconsistency with the absence of effect on mean gestational age) requires further study, especially in light of the results of some observational studies of heavy work or prolonged standing (Henriksen 1995; Mamelle 1984). The report of large increases in birthweight and placental size in physically fit women who prolonged their bouts of exercise in early pregnancy followed by reduction in later pregnancy requires confirmation in larger trials. Besides the traditional focus on fetal growth and gestational duration, future trials should assess the potential impacts on pain and duration of labour and on the risk of cesarean section, as well as possible reduction in risks of pregnancy‐induced hypertension and pre‐eclampsia (Weissgerber 2004). Given the differential risks and benefits of weight‐bearing versus nonweight‐bearing aerobic exercise for women in general and during pregnancy (Artal 1989), future trials should also compare types of aerobic exercise.

Feedback

Vlassov, 15 March 2008

Summary

The Abstract for this review is misleading. It comments that 11 studies are included, and then states that five reported increased physical fitness. No data are presented and it is unclear why the authors conclude that aerobic exercise increases physical fitness.

Reply

In the Abstract, we clearly indicate that the measures of physical fitness were highly heterogeneous, and thus data presentation would require separate tables for all measures in all studies reporting on fitness.

Contributors

Summary of feedback from Vasiliy Vlassov, March 2008.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 23 December 2009 | New search has been performed | Search updated: 18 new reports added. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1996 Review first published: Issue 3, 1996

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 June 2008 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback from Vasiliy Vlassov added. |

| 23 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 30 April 2006 | New citation required and minor changes | New author. |

| 30 June 2005 | New search has been performed | Search updated. New studies were added to the Background and Implications for research sections, expanding these sections; one new trial was added (Wolfe 1999) and one trial, previously included, was removed pending clarification of further information received from the authors of the trial (Lee 1996a); one study which was included only as an abstract in a previous review is now included as a published article, adding more outcomes; new comparisons were added; general updates and modifications were made; despite all this, our conclusions remain unchanged. |

Acknowledgements

Edward Plaisance Jr translated Memari 2006 from Persian.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Authors searched the following:

MEDLINE (1966 to August 2009)

1. exp *Pregnancy/ or exp *PREGNANT WOMEN/ or exp Pregnancy Complications/ 2. exp EXERCISE THERAPY/ or exp *EXERCISE/ or exp EXERCISE TEST/ or exp EXERCISE TOLERANCE/ 3. 1 and 2 4. random$.mp. 5. 3 and 4

EMBASE (1980 to August 2009)

1. exp *Pregnancy/ or exp *PREGNANT WOMAN/ 2. exp ISOKINETIC EXERCISE/ or exp*EXERCISE/ or exp EXERCISE TOLERANCE/ or exp STATIC EXERCISE/ or TREADMILL EXERCISE/ 3. 1 and 2 4. controlled.mp. 5. 3 and 4

Conference Papers Index (to August 2009)

(pregnant or pregnancy) and (exercise or aerobic)

Appendix 2. Methods used to assess trials included in previous versions of this review

The following methods were used to assess Bell 2000; Carpenter 1990; Clapp 2000; Clapp 2002; Collings 1983; Erkkola 1976; Marquez 2000; Prevedel 2003; Sibley 1981; South‐Paul 1988; Wolfe 1999.

Both review authors independently evaluated trials under consideration for methodological quality and appropriateness for inclusion without consideration of their results. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion.

We assessed the validity of each study using criteria outlined in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Alderson 2004). We operationalized selection bias using quality scores for allocation concealment: adequate (A), unclear (B), or inadequate (C). We assessed attrition bias in terms of percentage loss of participants (dropouts, withdrawals) and whether the losses were asymmetric, that is, different in the randomized groups. Attempts were made to contact study authors to provide missing data.

Both review authors independently extracted study data. RevMan5 was used for data entry and meta‐analysis; reported effect measures are relative risks and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous outcomes and weighted mean differences and their 95% CIs for continuous outcomes. We report outcomes within data type (dichotomous versus continuous), with dichotomous outcomes presented first. Results are reported for three different comparisons, based on the types of participants and specific nature of the trial interventions: (1) increase in exercise among sedentary pregnant women; (2) initial increase followed by reduction in exercise among fit pregnant women; and (3) initial reduction followed by increase in exercise among fit pregnant women.

All analyses were based on the principle of intention to treat, whether or not the original studies presented their results as such.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Increase in exercise in sedentary women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Small‐for‐gestational‐age birth | 2 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Preterm birth | 3 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.82 [0.35, 9.57] |

| 3 Pre‐eclampsia | 2 | 82 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.44, 3.08] |

| 4 Stillbirth | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Neonatal death | 2 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Cesarean section | 3 | 386 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.60, 1.53] |

| 7 Total gestational weight gain (kg) | 4 | 122 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [‐0.73, 2.31] |

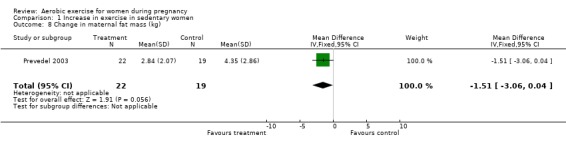

| 8 Change in maternal fat mass (kg) | 1 | 41 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.51 [‐3.06, 0.04] |

| 9 Change in maternal lean mass (kg) | 1 | 41 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.59 [0.38, 2.80] |

| 10 Birthweight (g) | 6 | 556 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 49.49 [‐27.74, 126.73] |

| 11 Birth fat mass (g) | 1 | 46 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 30.0 [‐82.72, 142.72] |

| 12 Birth lean mass (g) | 1 | 46 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 19.0 [‐161.21, 199.21] |

| 13 Birth % body fat | 1 | 46 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [‐1.78, 2.38] |

| 14 Birth length (cm) | 2 | 64 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.48, 2.07] |

| 15 Birth head circumference (cm) | 1 | 46 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [‐0.43, 1.23] |

| 16 Birth ponderal index (g/cm3 x 100) | 1 | 46 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.04 [‐0.07, 0.15] |

| 17 Gestational age (wk) | 4 | 495 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.11, 0.30] |

| 18 Placental volume at delivery (cm3) | 1 | 46 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 48.00 [3.30, 92.70] |

| 19 Mid‐trimester placental growth rate (cm3/wk) | 1 | 46 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [4.07, 5.93] |

| 20 Placental weight at delivery (g) | 1 | 16 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 14.30 [‐118.70, 147.30] |

| 21 Duration of labour, first stage (hr) | 1 | 18 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.00 [‐1.15, 5.15] |

| 22 Duration of labour, second stage (min) | 2 | 316 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.72 [‐15.22, 3.78] |

| 23 1‐minute Apgar score | 1 | 20 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [‐1.37, 3.37] |

| 24 5‐minute Apgar score | 4 | 462 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.15 [‐0.10, 0.39] |

| 25 Relative heart volume post‐delivery (cm3/m2) | 1 | 44 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 39.0 [1.78, 76.22] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 1 Small‐for‐gestational‐age birth.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 2 Preterm birth.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 3 Pre‐eclampsia.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 4 Stillbirth.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 5 Neonatal death.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 6 Cesarean section.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 7 Total gestational weight gain (kg).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 8 Change in maternal fat mass (kg).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 9 Change in maternal lean mass (kg).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 10 Birthweight (g).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 11 Birth fat mass (g).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 12 Birth lean mass (g).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 13 Birth % body fat.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 14 Birth length (cm).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 15 Birth head circumference (cm).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 16 Birth ponderal index (g/cm3 x 100).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 17 Gestational age (wk).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 18 Placental volume at delivery (cm3).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 19 Mid‐trimester placental growth rate (cm3/wk).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 20 Placental weight at delivery (g).

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 21 Duration of labour, first stage (hr).

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 22 Duration of labour, second stage (min).

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 23 1‐minute Apgar score.

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 24 5‐minute Apgar score.

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Increase in exercise in sedentary women, Outcome 25 Relative heart volume post‐delivery (cm3/m2).

Comparison 2. Reduction in exercise in physically fit women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Preterm birth | 1 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.08, 17.99] |

| 2 Birthweight (g) | 1 | 61 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐135.0 [‐368.66, 98.66] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 1 Preterm birth.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 2 Birthweight (g).

Comparison 3. Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gestational weight gain (kg) | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [‐1.59, 3.39] |

| 2 Birthweight (g) | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 460.0 [251.63, 668.37] |

| 3 Birth fat mass (g) | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 210.0 [148.02, 271.98] |

| 4 Birth lean mass (g) | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 260.0 [79.28, 440.72] |

| 5 Birth % body fat | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.20 [2.71, 5.69] |

| 6 Birth length (cm) | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.40 [0.69, 2.11] |

| 7 Birth head circumference (cm) | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [‐0.21, 1.21] |

| 8 Birth ponderal index (g/cm3 x 100) | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.03, 0.25] |

| 9 Gestational age (wk) | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [‐0.36, 1.22] |

| 10 Placental volume at delivery (cm3) | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 65.0 [‐5.26, 135.26] |

| 11 Mid‐trimester placental growth rate (cm3/wk) | 1 | 49 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [‐4.54, 6.54] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 1 Gestational weight gain (kg).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 2 Birthweight (g).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 3 Birth fat mass (g).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 4 Birth lean mass (g).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 5 Birth % body fat.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 6 Birth length (cm).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 7 Birth head circumference (cm).

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 8 Birth ponderal index (g/cm3 x 100).

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 9 Gestational age (wk).

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 10 Placental volume at delivery (cm3).

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Increase, then reduction in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 11 Mid‐trimester placental growth rate (cm3/wk).

Comparison 4. Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gestational weight gain (kg) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.60 [‐4.96, ‐0.24] |

| 2 Birthweight (g) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐100.0 [‐308.39, 108.39] |

| 3 Birth fat mass (g) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 20.0 [‐7.72, 47.72] |

| 4 Birth lean mass (g) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐100.00 [‐280.74, 80.74] |

| 5 Birth % body fat | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [‐0.38, 1.58] |

| 6 Birth length (cm) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐0.93, 0.73] |

| 7 Birth head circumference (cm) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.20 [‐0.91, 0.51] |

| 8 Birth ponderal index (g/cm3 x 100) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.07 [‐0.17, 0.03] |

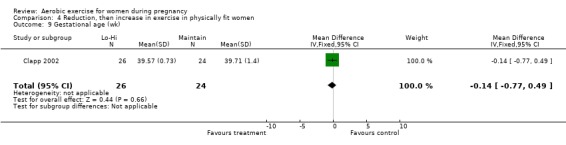

| 9 Gestational age (wk) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.14 [‐0.77, 0.49] |

| 10 Placental volume at delivery (cm3) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐33.0 [‐73.36, 7.36] |

| 11 Mid‐trimester placental growth rate (cm3/wk) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.00 [‐7.38, 1.38] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 1 Gestational weight gain (kg).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 2 Birthweight (g).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 3 Birth fat mass (g).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 4 Birth lean mass (g).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 5 Birth % body fat.

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 6 Birth length (cm).

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 7 Birth head circumference (cm).

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 8 Birth ponderal index (g/cm3 x 100).

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 9 Gestational age (wk).

4.10. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 10 Placental volume at delivery (cm3).

4.11. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Reduction, then increase in exercise in physically fit women, Outcome 11 Mid‐trimester placental growth rate (cm3/wk).

Comparison 5. Increase in exercise in overweight women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Preterm birth | 1 | 72 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.89 [0.18, 19.95] |

| 2 Birthweight (g) | 1 | 72 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.0 [‐241.27, 231.27] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Increase in exercise in overweight women, Outcome 1 Preterm birth.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Increase in exercise in overweight women, Outcome 2 Birthweight (g).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bell 2000.

| Methods | Randomization by use of a random numbers table and consecutively numbered opaque envelopes. | |

| Participants | 61 pregnant women intending to exercise at least 5 times per week throughout pregnancy. All women exercised regularly pre‐pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: continued strenuous exercise >= 5 times per week from 24 weeks. Control: strenuous exercise reduced to <= 3 times per week from 24 weeks. | |

| Outcomes | Mean birthweight and preterm birth rate. | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Random number table. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. No mention of blinding of outcome assessors, but most outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | No reported losses or post‐randomization exclusions. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Carpenter 1990.

| Methods | Randomization method not described. | |

| Participants | 14 sedentary women at an average of 21 weeks' gestational age. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: 30 minutes of aerobic exercise 4 times per week for 10 weeks. Control: no exercise. | |

| Outcomes | Physical fitness; no data reported on pregnancy outcomes. | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. No mention of blinding of outcome assessors, but most outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Unable to assess based on information provided. |

Clapp 2000.

| Methods | Randomization "by envelope" not otherwise described. | |

| Participants | 50 healthy pregnant women who did not exercise regularly before pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: 20 minutes of aerobic exercise 3‐5 times per week beginning at 8‐9 weeks and continuing until delivery. Control: no aerobic exercise. | |

| Outcomes | Gestational weight gain, mid‐trimester placental growth rate, placental volume, birthweight, length, ponderal index, and head circumference, preterm birth, infant lean mass, fat mass, %fat. | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Inadequate information provided. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. Except for placental morphometry, outcome assessors were unblinded, but most other outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Balanced losses. Anayses not ITT, but bias unlikely. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | Authors state that development of pregnancy complications merited exclusion from data analysis, but only 2 participants excluded for this reason. |

Clapp 2002.

| Methods | Randomization "by envelope" not otherwise described. | |

| Participants | 80 healthy, physically fit pregnant women who exercised >= 3 times per week before pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Experimental (2 groups): 60 minutes weight‐bearing exercise 5 days per week from 8 to 20 weeks, then reduced to 20 minutes 5 times per week from 24 weeks to delivery ('Hi‐Lo' group); opposite pattern ('Lo‐Hi' group). Control: intermediate intensity, constant pattern (40 minutes 5 days per week from 8 weeks to delivery). | |

| Outcomes | Gestational weight gain, mid‐trimester placental growth rate, placental volume, birthweight, length, ponderal index, and head circumference, preterm birth, infant lean mass, fat mass, % body fat, gestational age. | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. Except for placental morphometry, outcome assessors were unblinded, but most other outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Post‐randomization exclusions symmetrical (1 from each group). Analyses not ITT but bias unlikely. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Collings 1983.

| Methods | First 5 women selected their own treatment, remainder 'randomized' using unspecified method. | |

| Participants | 20 healthy pregnant women in 2nd trimester. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: 3 times per week aerobic exercise (cycle ergometer) for 13 weeks. Control: no regular exercise. | |

| Outcomes | Physical fitness, placental weight, birthweight, birth length, 1‐ and 5‐minute Apgar scores, gestational age, preterm birth, stillbirth, neonatal mortality, low birthweight, small‐for‐gestational age, pre‐eclampsia, gestational weight gain, duration of labour, and cesarean section. Fetal heart rate (acute exercise effect) not reported in review. | |

| Notes | Authors say no losses or non‐compliance with intervention. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Inadequate; first 5 women selected their own treatment. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. No mention of blinding of outcome assessors, but most outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | No reported losses. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Erkkola 1976.

| Methods | Allocation by strict alternation in a consecutive series. | |

| Participants | 76 healthy primips with singleton fetuses. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: training exercise for 1 hour, 3 times per week starting at 10‐14 weeks' gestational age. Control: no instructions for training. | |

| Outcomes | Physical fitness, heart volume, birthweight, gestational age, and pre‐eclampsia. | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Inadequate: alternation. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. No mention of blinding of outcome assessors, but most outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Large but balanced losses. Bias unlikely. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Lee 1996.

| Methods | Random number table used to allocate treatment, but no apparent method used to conceal allocation from research personnel or consenting participants. | |

| Participants | 370 healthy, nonsmoking nulliparae with singleton fetus < 20 weeks of gestation. | |

| Interventions | Intervention: aerobic exercise 1 hour 3 times per week from 20 weeks until delivery. Control: no intervention. |

|

| Outcomes | Duration of 2nd stage of labour, birthweight, gestational age, 5‐minute Apgar score. | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Random number table. |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Author correspondence notes inadequate concealment. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. No mention of blinding of outcome assessors, but most outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Post‐randomization exclusions not compared by group, and the exclusion factors could have been (although probably were not) caused or prevented by the intervention. Study is included, but with caveats about possible bias. |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Published manuscript reports on only a subset of outcomes that were originally obtained. Study is included with caveats about this possible bias. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | Apart from caveats mentioned above, other biases unlikely. |

Marquez 2000.

| Methods | Allocation method not described, yet appears to be quasi‐randomization. | |

| Participants | 20 sedentary primigravidae in second trimester of pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: aerobic exercise 1 hour 3 times per week for 15 weeks. Control: no aerobic exercise during pregnancy. | |

| Outcomes | Physical fitness, gestational weight gain, birthweight, 5‐minute Apgar score, cesarean section, and body image. | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | High risk | Alternate allocation. |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Alternate allocation. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. No mention of blinding of outcome assessors, but most outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Despite unbalanced losses, bias unlikely. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Memari 2006.

| Methods | Randomization method not described. | |

| Participants | 80 healthy but sedentary women from Tehran (Iran) in their second pregnancy recruited at 18 weeks of gestation. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: aerobic exercise 15‐30 minutes per day, 3 days per week, for 8 weeks Control: no intervention. |

|

| Outcomes | Gestational age, birthweight, 5‐minute Apgar score | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. No mention of blinding of outcome assessors, but most outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Translated notes report no withdrawls or losses; no information on post‐randomization exclusions. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Prevedel 2003.

| Methods | Randomization method not described. | |

| Participants | 60 healthy primips at 16 weeks. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: hydrotherapy program 1 hour 3 times per week throughout 2nd half of pregnancy Control: not offered hydrotherapy program. | |

| Outcomes | Physical fitness, gestational weight gain, lean mass, fat mass,%fat, birthweight, gestational age, preterm birth, perinatal death, SGA. | |

| Notes | 19 women were lost to follow up, non‐compliant, or excluded for obstetric/medical reasons (no breakdown for type of loss). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. No mention of blinding of outcome assessors, but most outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Balanced overall losses, although no breakdown provided about type of loss by group. Bias unlikely. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Santos 2005.

| Methods | Randomization via "blocked sequence" (not further specified) generated from a random number table, using numbered opaque envelopes. | |

| Participants | 92 overweight (pre‐pregnancy BMI 25‐30 kg/m2) but otherwise healthy women < 20 weeks of gestation. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: supervised aerobic exercise sessions for 60 minutes per day, 3 times per week, for 12 weeks. Control: weekly relaxation and stretching sessions (no aerobic or weight‐resistance exercise during sessions). |

|

| Outcomes | Physical fitness, preterm birth, mean birthweight, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension/pre‐eclampsia, cesarean delivery. | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Random number table. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Numbered opaque envelopes. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. Outcome assessor for main outcomes blinded to treatment allocation. Low risk of bias. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Balanced losses. Bias unlikely. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Sibley 1981.

| Methods | Randomization method not described. | |

| Participants | 13 healthy women age 18‐35 years and 13‐26 weeks' gestational age. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: aerobic (swimming) exercise for 1 hour, 3 times per week for 10 weeks. Control: normal activity without aerobic exercise. | |

| Outcomes | Physical fitness; no data reported on pregnancy outcomes. Fetal heart rate before and after exercise (acute exercise effect) not included in review. | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described. Authors report that participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups but also describe the design as quasi‐experimental. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. No mention of blinding of outcome assessors, but most outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | No losses reported. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

South‐Paul 1988.

| Methods | Randomization method not described. | |

| Participants | 23 untrained healthy women (primips and multips) age 19‐35 years at beginning of the 2nd trimester. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: progressive aerobic exercise (cycle ergometer) 1 hour 3 times per week. Control: usual physical activity without supervised exercise. | |

| Outcomes | Physical fitness, respiratory fitness; no data reported on pregnancy outcomes. | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. No mention of blinding of outcome assessors, but most outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Asymmetric losses but unlikely to affect results. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | |

Wolfe 1999.

| Methods | Randomization method not described. | |

| Participants | 55 healthy, previously sedentary pregnant women at beginning of second trimester. | |

| Interventions | Experimental: aerobic conditioning (stair stepping) 30 minutes 3 times per week plus light muscular conditioning during second and third trimesters. Control: light muscular conditioning only. | |

| Outcomes | Physical fitness; infant birthweight, length, body circumferences, limb lengths, adiposity. | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Nature of intervention prevents blinding of participants. No mention of blinding of outcome assessors, but most outcomes are objectively measured, and thus risk of biased measurement is low. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information on losses of any type. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | Information insufficient to assess. |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Information insufficient to assess. |

BMI: body mass index ITT: intention to treat IUGR: intrauterine growth restriction SD: standard deviation SEM: standard error of the mean SGA: small‐for‐gestational age

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Aittasalo 2008 | Allocation was not randomly allocated but was self‐selected by clinics. In addition, no outcome data reported. |

| Asbee 2009 | Intervention included both dietary and exercise recommendations, making it difficult to separate the 2 components. |

| Barakat 2008 | Intervention not aerobic: described as "very light resistance and toning exercises." |

| Callaway 2008 | Feasibility/pilot study only. Intervention judged infeasible, no data reported on outcomes. |

| Granath 2006 | Both intervention and control groups included exercise component (water vs land‐based exercise program), and both groups exercised only once per week. |

| Hui 2006 | Intervention included both diet and exercise components. Moreover, the exercise program consisted of only 1 supervised group exercise session per week and a recommendation for home‐based exercise. |

| Kihlstrand 1999 | Exercise intervention was only 30 minutes per week. |

| Kulpa 1987 | Ambiguous methodology (e.g., exercise intervention and participant allocation ill‐defined). |

| Lawani 2003 | Allocation to the groups was neither randomized nor quasi‐randomized. |

| McAuley 2005 | Nearly half of randomized women dropped out "for medical reasons or poor compliance". |

| McDonald 2001 | No mention of randomization or other method of allocation, no data reported on control (no exercise) group. |

| Polley 2002 | Intervention included both dietary and exercise recommendations, making it difficult to separate the 2 components. Also, the 'modest' exercise recommendation resulted in similar exercise levels post‐intervention in the 2 comparison groups, raising concerns about compliance and potency of intervention. |

| Quinlivan 2007 | Intervention includes both dietary and exercise recommendations, making it difficult to separate the 2 components. |

| Satyapriya 2009 | Intervention based on yoga and "deep relaxation" (i.e., not aerobic). |

| Varrassi 1989 | Ambiguous methodology (e.g., exercise intervention and participant allocation ill‐defined). |

| Yeo 2008 | Intervention intensity too low (walking program in which women reached their target heart rate only 35% of the time at 18 weeks and 17% at the end of pregnancy). |

RCT: randomized controlled trial vs: versus

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Haakstad 2008.

| Trial name or title | Haakstad 2008. |

| Methods | RCT. |

| Participants | 100 sedentary primiparous women < 24 weeks' gestation. |

| Interventions | Supervised aerobic exercise for 60 minutes at least 2 times per week, for 12‐16 weeks. |

| Outcomes | Gestational weight gain, physical fitness, birthweight, duration of labour, delivery complications. |

| Starting date | November 2007. |

| Contact information | Lene Haakstad, Norwegian School of Sport Science, Oslo. |

| Notes |

Hofman 2005.

| Trial name or title | Hopkins 2005. |

| Methods | RCT. |

| Participants | 120 healthy nulliparous pregnant women with singleton gestation < 20 weeks' gestation. |

| Interventions | Moderate aerobic exercise for 40 minutes, 5 times per week until term. |

| Outcomes | Maternal insulin sensitivity at 20 and 35 weeks, newborn size and body composition. |

| Starting date | December 2004. |

| Contact information | Sarah Hopkins, Liggins Institute, U of Auckland, NZ. |

| Notes |

Ko 2008.

| Trial name or title | Ko 2008. |

| Methods | RCT. |

| Participants | Healthy pregnant women 18‐45 years of age and < 13 weeks of gestation. |

| Interventions | Advice to increase vigorous physical activity. |

| Outcomes | Central adiposity measured 6‐8 weeks postpartum; maternal leptin, glucose, insulin, and cholesterol; fetal and neonatal adiposity. |

| Starting date | October 2007. |

| Contact information | Cynthia Ko, U of Washington. |

| Notes |

Morkved 2007.

| Trial name or title | Morkved 2007. |

| Methods | RCT. |

| Participants | Healthy pregnant > 18 years with singleton gestation at 18 weeks. |

| Interventions | "Regular exercise." |

| Outcomes | Gestational diabetes, low back and pelvic girdle pain, maternal weight gain, labour and delivery, fetal macrosomia. |

| Starting date | May 2007. |

| Contact information | Siv Morkved, Dept of Communituy Medicine and General Practice, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim. |

| Notes | Vague description of intervention. |

Oostdam 2009.

| Trial name or title | Oostdam 2009. |

| Methods | RCT. |

| Participants | Pregnant women > 18 years of age and at increased risk for gestational diabetes, recruited 14‐20 weeks' gestation. |

| Interventions | Supervised aerobic exercise for 60 minutes, 2 days per week. |

| Outcomes | Maternal fasting glucose and insulin, maternal lipids and HbA1c, gestational weight gain, birthweight. |

| Starting date | Not stated. |

| Contact information | Nicolette Oostdam, Dept of Public and Occupational Health, VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam. |

| Notes | Publication includes study rationale and protocol, but no results. |

RCT: randomized controlled trial

Contributions of authors

Michael Kramer prepared the first draft and the 2002 and 2009 updates of this review. Sheila McDonald developed the 2005 update with mentoring and input from Michael Kramer; she also completed the Risk of bias in included studies and collaborated in all other aspects of the 2009 update.

Sources of support

Internal sources

McGill University, Canada.

External sources

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada.

Declarations of interest

We certify that we have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter of the review or our criticisms (e.g., employment, consultancies, stock ownership, honoraria, expert testimony).

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Bell 2000 {published data only}

- Bell R, Palma S. Antenatal exercise and birthweight. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2000;40(1):70‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carpenter 1990 {published data only}

- Carpenter MW, Sady SP, Haydon BB, Coustan DR, Thompson PD. Effects of exercise training in midpregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Proceedings of 37th Annual Meeting of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation; 1990; St Louis, USA. 1990:345.

Clapp 2000 {published data only}

- Clapp JF, Kim H, Burciu B, Lopez B. Beginning regular exercise in early pregnancy: effect on fetoplacental growth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;183(6):1484‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clapp 2002 {published data only}

- Clapp JF, Kim H, Burciu B, Schmidt S, Petry K, Lopez B. Continuing regular exercise during pregnancy: effect of exercise volume on fetoplacental growth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2002;186(1):142‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collings 1983 {published and unpublished data}

- Collings CA, Curet LB, Mullin JP. Maternal and fetal responses to a maternal aerobic exercise program. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1983;145:702‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Erkkola 1976 {published and unpublished data}

- Erkkola R. Physical Work Capacity and Pregnancy [thesis]. Turku, Finland: University Central Hospital, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Erkkola R. The influence of physical exercise during pregnancy upon physical work capacity and circulatory parameters. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 1976;6:747‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkkola R, Makela M. Heart volume and physical fitness of parturients. Annals of Clinical Research 1976;8:15‐21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 1996 {published and unpublished data}

- Lee G. Exercise in pregnancy. Personal communication 30th December 1991‐30th April 1994.

- Lee G, Challenger S, McNabb M, Sheridan M. A randomised controlled trial on exercise in pregnancy. International Confederation of Midwives 24th Triennial Congress; 1996 May 26‐31; Oslo. 1996:9.

- Lee G, Challenger S, McNabb M, Sheridan M. Exercise in pregnancy. Modern Midwife 1996;6:28‐33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marquez 2000 {published data only}

- Marquez‐Sterling S, Perry AC, Kaplan TA, Halberstein RA, Signorile JF. Physical and psychological changes with vigorous exercise in sedentary primigravidae. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise 2000;32(1):58‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Memari 2006 {published data only}

- Memari AA, Ramim T, Amini M, Mehran A, Akharlu A, Shkiba'i P. The effects of aerobic exercise on pregnancy and its outcomes. HAYAT. Journal of the School of Nursing and Midwifery 2006;12(4):35‐41. [Google Scholar]

Prevedel 2003 {published data only}

- Prevedel T, Calderon I, Abadde J, Borges V, Rudge M. Maternal effects of hydrotherapy in normal women. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 2001;29 Suppl 1(Pt 2):665‐6. [Google Scholar]

- Prevedel T, Calderon I, DeConti M, Consonni E, Rudge M. Maternal and perinatal effects of hydrotherapy in pregnancy. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia y Obstetricia 2003;25(1):53‐9. [Google Scholar]

Santos 2005 {published data only}

- Santos IA, Stein R, Fuchs SC, Duncan BB, Ribeiro JP, Kroeff LR, et al. Aerobic exercise and submaximal functional capacity in overweight pregnant women: a randomized trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2005;106(2):243‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sibley 1981 {published data only}

- Sibley L, Ruhling RO, Cameron‐Foster J, Christensen C, Bolen T. Swimming and physical fitness during pregnancy. Journal of Nurse‐Midwifery 1981;26:3‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

South‐Paul 1988 {published data only}

- South‐Paul JE, Rajagopal KR, Tenholder MF. The effect of participation in a regular exercise program upon aerobic capacity during pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1988;71:175‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wolfe 1999 {published data only}

- Wolfe L, Mottola M, Bonen A, MacPhail A, Sloboda D, Hains S, et al. Controlled, randomized study of aerobic conditioning effects on neonatal morphometrics. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise 1999;31(5 Suppl):S138. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Aittasalo 2008 {published data only}

- Aittasalo M, Pasanen M, Fogelholm M, Kinnunen TI, Ojala K, Luoto R. Physical activity counseling in maternity and child health care ‐ a controlled trial. BMC Women's Health 2008;8:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Asbee 2009 {published data only}

- Asbee SM, Jenkins TR, Butler JR, White J, Elliot M, Rutledge A. Preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy through dietary and lifestyle counselling. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2009;113:305‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Barakat 2008 {published data only}

- Barakat R, Stirling JR, Lucia A. Does exercise training during pregnancy affect gestational age? A randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2008;42(8):674‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Callaway 2008 {published data only}

- Callaway L. A randomized controlled trial using exercise to reduce gestational diabetes and other adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in obese pregnant women ‐ the pilot study. Australian Clinical Trials Registry (www.actr.org.au) (accessed 21 June 2007).

- Callaway L, McIntyre D, Colditz P, Byrne N, Foxcroft K, O'Connor B. Exercise in obese pregnant women: a randomized study to assess feasibility. Hypertension in Pregnancy 2008;27(4):549. [Google Scholar]

Granath 2006 {published data only}

- Granath AB, Hellgren MS, Gunnarsson RK. Water aerobics reduces sick leave due to low back pain during pregnancy. JOGNN ‐ Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing 2006;35(4):465‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hui 2006 {published data only}

- Hui AL, Ludwig SM, Gardiner P, Sevenhuysen G, Murray R, Morris M, et al. Community‐based exercise and dietary intervention during pregnancy: a pilot study. Canadian Journal of Diabetes 2006;30(2):169‐75. [Google Scholar]

Kihlstrand 1999 {published data only}

- Kihlstrand M, Stenman B, Nilsson S, Axelsson O. Water gymnastics reduced the intensity of back/low back pain in pregnant women. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1999;78:180‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kulpa 1987 {published data only}

- Kulpa PJ, White BM, Visscher R. Aerobic exercise in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1987;156:1395‐403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lawani 2003 {published data only}

- Lawani M, Alihonou E, Akplogan B, Poumarat G, Okou L, Adjadi N. Effect of antenatal gymnastics on childbirth: a study on 50 sedentary women in the Republic of Benin during the second and third quarters of pregnancy [L'effet de la gymnastique prenatale sur l'accouchement: etude sur 50 femmes beninoises sedentaires au cours des deuxieme et troisieme trimestres de grossesse]. Sante 2003;13(4):235‐41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McAuley 2005 {published data only}

- McAuley SE, Jensen D, McGrath MJ, Wolfe LA. Effects of human pregnancy and aerobic conditioning on alveolar gas exchange during exercise. Canadian Journal of Physiology & Pharmacology 2005;83(7):625‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McDonald 2001 {published data only}

- Lynch AM, Goodman C, Choy PL, Dawson B, Newnham JP, McDonald S, et al. Maternal physiological responses to swimming training during the second trimester of pregnancy. Research in Sports Medicine 2007;15:33‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SJ, Newnham JP, Evans SF, Lynch AM, Goodman C. The effect of aquatic exercise during pregnancy on fetal wellbeing. 20th Conference on Priorities in Perinatal Care in Southern Africa; 2001 March 6‐9; KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa. 2001.

Polley 2002 {published data only}

- Polley B, Wing R, Sims C. Randomized controlled trial to prevent excessive weight gain in pregnant women. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders 2002;26(11):1494‐502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Quinlivan 2007 {published data only}

- Quinlivan J. A randomised trial of a multidisciplinary teamcare approach involving obstetric, dietary and clinical psychological input in obese pregnant women to reduce the incidence of gestational diabetes. Australian Clinical Trials Register (www.actr.org.au) (accessed 6 December 2005).

Satyapriya 2009 {published data only}

- Satyapriya M, Nagendra HR, Nagarathna R, Padmalatha V. Effect of integrated yoga on stress and heart rate variability in pregnant women. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2009;104(3):218‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Varrassi 1989 {published data only}

- Varrassi G, Bazzano C, Edwards WT. Effects of physical activity on maternal plasma beta‐endorphin levels and perception of labor pain. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1989;160:707‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yeo 2008 {published data only}

- Yeo S, Davidge S, Ronis DL, Antonakos CL, Hayashi R, O'Leary S. A comparison of walking versus stretching exercises to reduce the incidence of preeclampsia: a randomized clinical trial. Hypertension in Pregnancy 2008;27(2):113‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

Haakstad 2008 {published data only}

- Haakstad L. Effect of regular exercise in prevention of excessive weight gain in pregnancy. ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) (accessed 20 February 2008).

Hofman 2005 {published data only}

- Hofman P, Hopkins S. Randomised controlled study of the effects of exercise during pregnancy on maternal insulin sensitivity and neonatal outcomes. Australian Clinical Trials Register (http://www.actr.org/actr) (accessed 6 December 2005).

Ko 2008 {published data only}

- Ko CW. Effect of physical activity on metabolic syndrome in pregnancy and fetal outcome. ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) (accessed 9 April 2008).

Morkved 2007 {published data only}

- Morkved S. Effects of regular exercise during pregnancy. ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) (accessed 20 February 2008).

Oostdam 2009 {published data only}

- Oostdam N, Poppel MN, Eekhoff EM, Wouters MG, Mechelen W. Design of FitFor2 study: the effects of an exercise program on insulin sensitivity and plasma glucose levels in pregnant women at high risk for gestational diabetes. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2009;9:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Alderson 2004

- Alderson P, Green S, Higgins JPT, editors. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.2.2 [updated March 2004]. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1, 2004. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Artal 1989

- Artal R, Masaki D, Khodiguian N, Romem Y, Rutherford S, Wiswell R. Exercise prescription in pregnancy: weight‐bearing versus non‐weight‐bearing exercise. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1989;161(6 Pt 1):1464‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brenner 1999

- Brenner IK, Wolfe LA, Monga M, McGrath MJ. Physical conditioning effects on fetal heart rate responses to graded maternal exercises. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise 1999;31:792‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clapp 1993

- Clapp JF, Little KD, Capeless EL. Fetal heart rate response to sustained recreational exercise. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1993;168:198‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dye 2003

- Dye TDV, Fernandez D, Rains A, Fershteyn Z. Recent studies in the epidemiologic assessment of physical activity, fetal growth, and preterm delivery: a narrative review. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003;46(2):415‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Evenson 2004

- Evanson K, Savitz D, Huston S. Leisure‐time physical activity among pregnant women in the US. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 2004;18:400‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hatoum 1997

- Hatoum N, Clapp JF, Newman MR, Dajani N, Amini SB. Effects of maternal exercise on fetal activity in late gestation. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal Medicine 1997;6:134‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Henriksen 1995

- Henriksen TB, Hedegaard M, Secher NJ, Wilcox AJ. Standing at work and preterm delivery. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1995;102:198‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2008

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Leet 2003

- Leet T, Flick L. Effect of exercise on birthweight. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003;46(2):423‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lokey 1991

- Lokey EA, Tran ZV, Wells CL, Myers BC, Tran AC. Effects of physical exercise on pregnancy outcomes: a meta‐analytic review. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise 1991;23:1234‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magann 2002

- Magann EF, Evans SF, Newnham J. Antepartum, intrapartum, and neonatal significance of exercise on healthy low‐risk pregnant working women. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2002;99(3):466‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mamelle 1984

- Mamelle N, Laumon B, Lazar P. Prematurity and occupational activity during pregnancy. American Journal of Epidemiology 1984;119:309‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Manson 1999

- Manson JE, Hu FB, Rich‐Edwards JW, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willet WC, et al. A prospective study of walking as compared with vigorous exercise in the prevention of coronary heart disease in women. New England Journal of Medicine 1999;341:650‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mozurkewich 2000

- Mozurkewich EL, Luke B, Avni M, Wolf FM. Working conditions and adverse pregnancy outcome: a meta‐analysis. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2000;95:623‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Perkins 2007

- Perkins CCD, Pivarnik JM, Paneth N, Stein AD. Physical activity and fetal growth during pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2007;109:81‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pijpers 1984

- Pijpers L, Wladimiroff JW, McGhie J, Bom N. Effect of short‐term maternal exercise on maternal and fetal cardiovascular dynamics. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1984;91:1081‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2008 [Computer program]