Abstract

Background

Prostaglandins have mainly been used for postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) when other measures fail. Misoprostol, a new and inexpensive prostaglandin E1 analogue, has been suggested as an alternative for routine management of the third stage of labour.

Objectives

To assess the effects of prophylactic prostaglandin use in the third stage of labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (7 January 2011). We updated this search on 25 May 2012 and added the results to the awaiting classification section.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing a prostaglandin agent with another uterotonic or no prophylactic uterotonic (nothing or placebo) as part of management of the third stage of labour. The primary outcomes were blood loss 1000 mL or more and the use of additional uterotonics.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed eligibility and trial quality and extracted data.

Main results

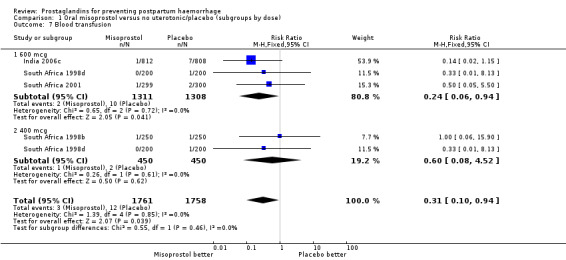

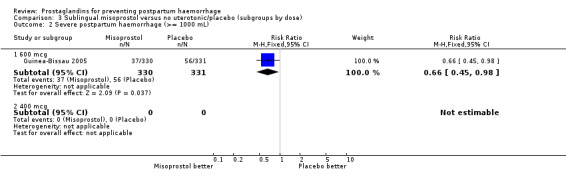

We included 72 trials (52,678 women). Oral or sublingual misoprostol compared with placebo is effective in reducing severe PPH (oral: seven trials, 6225 women, not totalled due to significant heterogeneity; sublingual: risk ratio (RR) 0.66; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.45 to 0.98; one trial, 661 women) and blood transfusion (oral: RR 0.31; 95% CI 0.10 to 0.94; four trials, 3519 women).

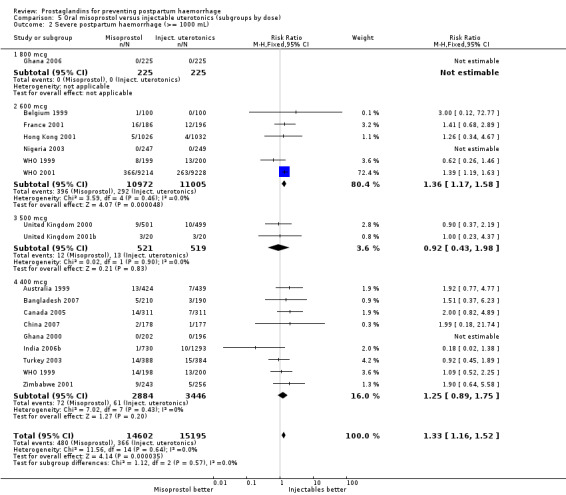

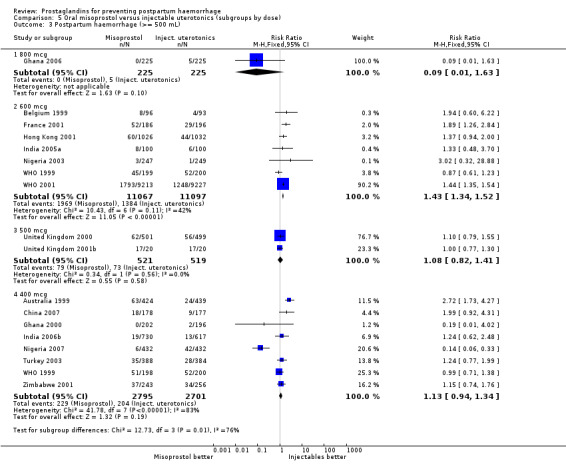

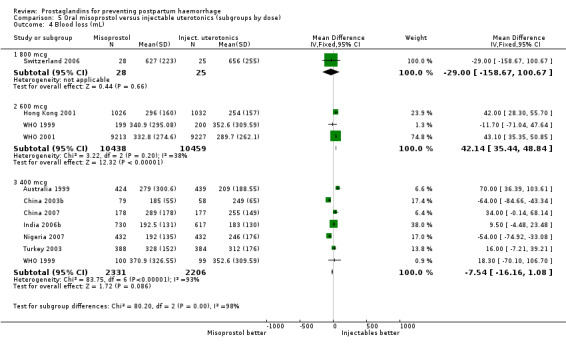

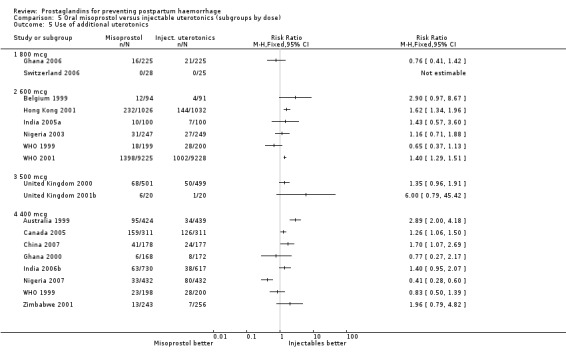

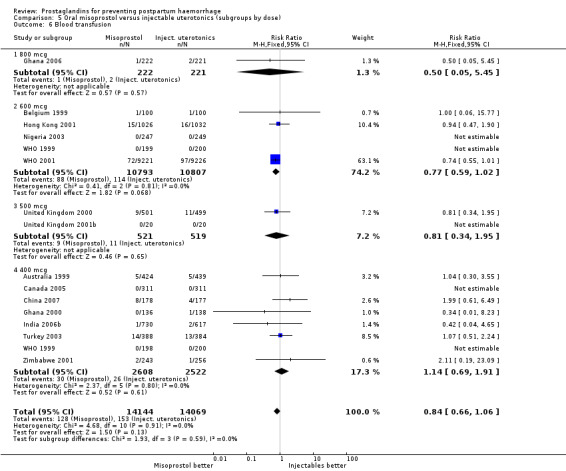

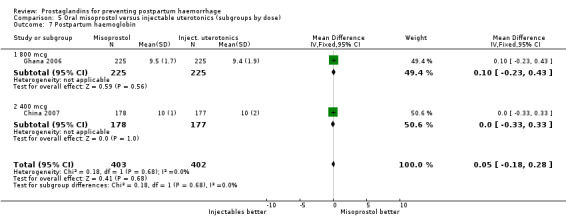

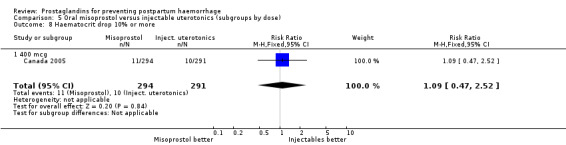

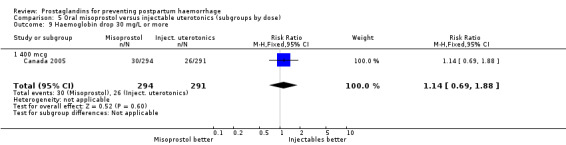

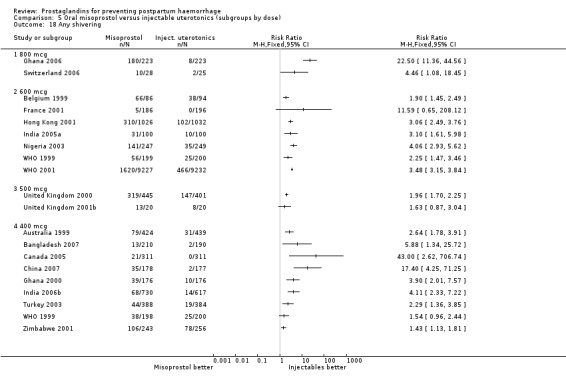

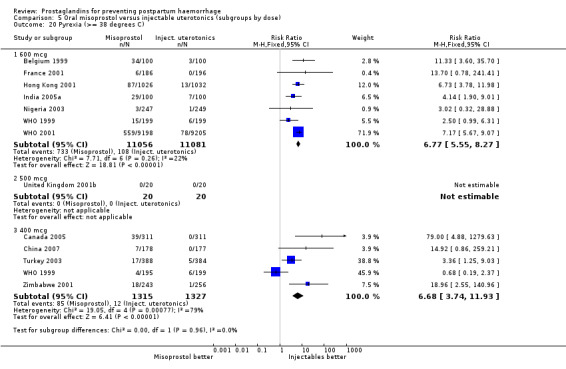

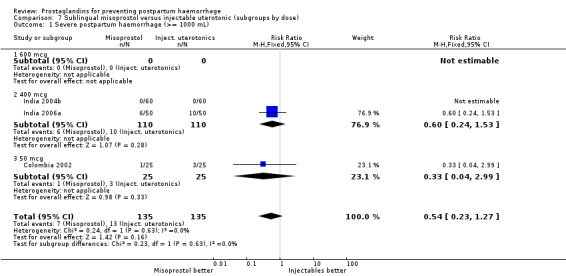

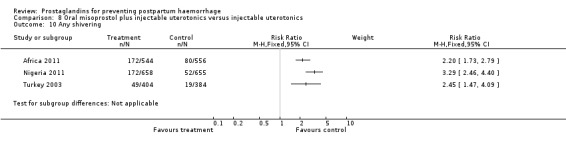

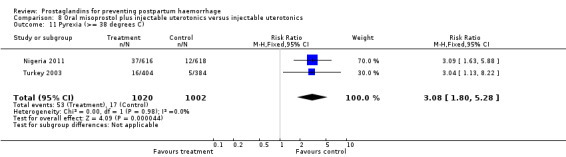

Compared with conventional injectable uterotonics, oral misoprostol was associated with higher risk of severe PPH (RR 1.33; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.52; 17 trials, 29,797 women) and use of additional uterotonics, but with a trend to fewer blood transfusions (RR 0.84; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.06; 15 trials; 28,213 women). Additional uterotonic data were not totalled due to heterogeneity. Misoprostol use is associated with significant increases in shivering and a temperature of 38º Celsius compared with both placebo and other uterotonics.

Authors' conclusions

Oral or sublingual misoprostol shows promising results when compared with placebo in reducing blood loss after delivery. The margin of benefit may be affected by whether other components of the management of the third stage of labour are used or not. As side‐effects are dose‐related, research should be directed towards establishing the lowest effective dose for routine use, and the optimal route of administration.

Neither intramuscular prostaglandins nor misoprostol are preferable to conventional injectable uterotonics as part of the management of the third stage of labour especially for low‐risk women; however, evidence has been building for the use of oral misoprostol to be effective and safe in areas with low access to facilities and skilled healthcare providers and future research on misoprostol use in the community should focus on implementation issues.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Labor Stage, Third; Administration, Oral; Administration, Sublingual; Fever; Fever/chemically induced; Misoprostol; Misoprostol/adverse effects; Misoprostol/therapeutic use; Oxytocics; Oxytocics/adverse effects; Oxytocics/therapeutic use; Postpartum Hemorrhage; Postpartum Hemorrhage/prevention & control; Prostaglandins; Prostaglandins/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Shivering

Plain language summary

Prostaglandins for preventing postpartum haemorrhage

An injectable uterotonic is the drug of choice for routine third stage management when the placenta is delivered. Oral or sublingual misoprostol may be used where no injectable uterotonic is available.

After her baby is born, the woman's womb (uterus) contracts and bleeding decreases. If the womb does not contract, postpartum haemorrhage (heavy bleeding) can occur, which can be life threatening. A prostaglandin, oxytocin and ergometrine are all drugs that cause contractions of the womb (uterotonics). This review of 72 randomised controlled trials, involving 52,678 women, found that oral or sublingual prostaglandin (misoprostol) is effective in reducing severe haemorrhage after giving birth and the need for blood transfusions. Misoprostol is not as effective as oxytocin and has more side‐effects. The main side‐effects are shivering, high temperature and diarrhoea, occurring in a significant proportion of women. Twenty‐six of the trials included centres in low‐ and middle‐income countries only. Misoprostol may be useful in places where injectable uterotonics are not available, perhaps because of poor access to skilled healthcare providers. Injectable prostaglandin may be effective in reducing blood loss but has adverse effects of vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea and costs more.

Background

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality during childbirth, especially in low‐ and middle‐income countries. The contribution of PPH to maternal death in low‐ and middle‐income countries is more marked in domiciliary or rural settings where trained staff are scarce, transport facilities are inadequate and the availability of uterotonic agents and blood are limited. According to the latest population‐based maternal mortality survey in Ghana, haemorrhage is the main cause, accounting for 24% of the maternal deaths (Ghana 2009).

The third stage of labour is defined as the period from birth of the baby until the delivery of the placenta and its membranes. This stage usually takes less than 10 minutes when active management is used. Active management of the third stage of labour is a term to express the use of uterotonics, early cord clamping and active efforts to deliver the placenta following birth. It is not always clearly defined and universally applied in a standard manner. PPH is usually defined as blood loss of 500 mL or more and severe PPH as 1000 mL or more in the third stage of labour. The 'normal' amount of blood loss is difficult to ascertain because different ways of managing the third stage and assessing the blood loss lead to markedly different amounts.

It has been well demonstrated that active management of the third stage of labour is associated with less blood loss. There seems to be general agreement that if the blood loss exceeds 500 mL close monitoring and additional measures such as administering uterotonics or checking for a cause of bleeding are prudent measures.

Traditionally, oxytocin and ergot preparations have been used as uterotonic agents for PPH prophylaxis mostly as part of active management of the third stage of labour. These agents, although effective in decreasing the blood loss, have the disadvantage of instability in tropical climates (Hogerzeil 1996) and also require the use of syringes and trained personnel for administration. Another disadvantage, mainly related to ergot preparations, is the relatively high incidence of side‐effects such as nausea, vomiting and increase in blood pressure.

Prostaglandins have strong uterotonic properties and are used widely in obstetric and gynaecological practice for cervical ripening, together with mifepristone for termination of pregnancy and for induction of labour. Prostaglandin preparations are available in injectable, tablet or gel forms according to their intended use. These agents do not cause hypertension, which enables them to be used in hypertensive patients. In the management of the third stage of labour, prostaglandins have been mainly used for intractable PPH as a last resort when other measures fail. To date, the main disadvantages of prostaglandins have been their cost and availability. Since the mid‐1990s, misoprostol, a prostaglandin E1 analogue used orally for the prevention of peptic ulcer disease has also been reported for use in the management of the third stage of labour (El‐Refaey 1997). Misoprostol is inexpensive, can be administered orally and is stable at ambient temperatures. There is considerable experience with misoprostol use, both for peptic ulcer disease and as a uterotonic in obstetrics and gynaecology. The main side‐effects of prostaglandins are nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. Shivering and elevated body temperature have been reported with the use of misoprostol in the third stage of labour.

The use of prostaglandins in general, and of misoprostol in particular, could have implications for the efficacy and acceptability of active management of the third stage of labour. The rate and nature of side‐effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, shivering) could influence the immediate relationship between the mother and her baby in the hours following birth.

Active management of the third stage of labour (by use of uterotonics, early cord clamping and active efforts to deliver the placenta) decreases blood loss during the third stage of labour (Begley 2011).

This review is one in a series of reviews evaluating strategies to prevent PPH (Cotter 2001; McDonald 2004) and focuses on the role of prostaglandins in the active management of the third stage of labour.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of prophylactic prostaglandin use compared with placebo or conventional uterotonics as part of the routine management of the third stage of labour.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials with a comparison between a prostaglandin and either another uterotonic agent or no uterotonic agent (placebo or nothing) were considered for inclusion in the review. We excluded quasi‐random studies.

Types of participants

Women after the birth of their baby were the participants of this review. These women could be at high or low risk for postpartum haemorrhage. The definitions of high risk used by the trialists were accepted in general. These typically included having had a previous postpartum haemorrhage, grand multiparity and multiple pregnancy among others.

Studies including women with caesarean births were eligible.

Types of interventions

In the earlier version of this review we included the use of prostaglandins when used 'as part of active management of the third stage of labour'. Recently, there has been increasing interest in evaluating the individual components of the 'active management' package and at least one trial has evaluated the use of a uterotonic without other components of active management of the third stage of labour. We included the use of a prostaglandin alone within the scope of this review.

The experimental intervention evaluated in this review is the prophylactic use of prostaglandins in the management of the third stage of labour. Prostaglandin preparations are currently available in injectable and tablet forms, therefore different routes may be used and compared either with each other or with conventional injectable uterotonic agents. Different routes of administration are analyzed in separate comparisons.

The choice of routine uterotonic drug used during the third stage of labour varies greatly around the world. In this review, oxytocin (Syntocinon®), ergometrine‐oxytocin (Syntometrine®) and ergometrine are grouped together as 'conventional injectable uterotonics'. In cases where the comparison is made between two different types of conventional uterotonics, oxytocin is selected as the conventional uterotonic as it is the drug used in most of the studies included in this review.

The main categories of prostaglandins evaluated in the review are misoprostol (prostaglandin E1 analogue), which is available in tablets and PGF2alpha and E2 preparations that are administered parenterally for use in the third stage of labour. Misoprostol tablets are administered either orally, sublingually or rectally. Since the absorption of misoprostol from these two routes is currently unknown and likely to be different, these routes have been evaluated separately.

Injection of oxytocin or saline, or both, into the umbilical vein (reviewed elsewhere on retained placenta) and intramyometrial injection of prostaglandins other than at caesarean section (not used for routine active management) were not eligible for inclusion in this review.

The following comparisons have been used in the review:

oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo;

oral misoprostol versus injectable (conventional) uterotonics;

rectal misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo;

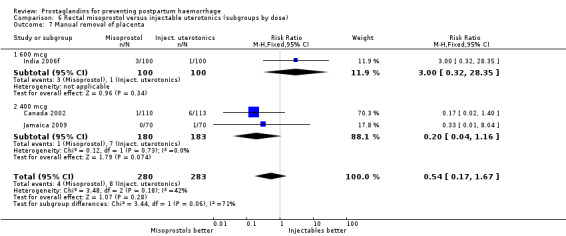

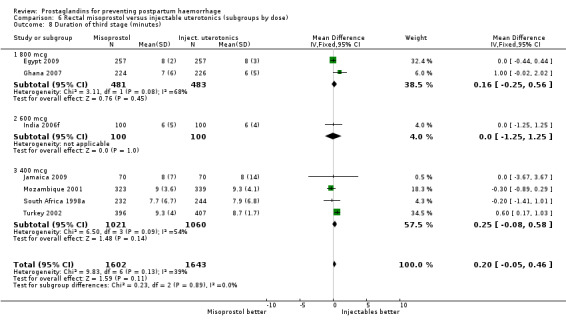

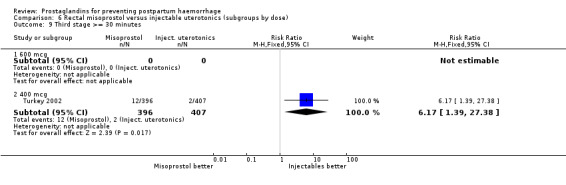

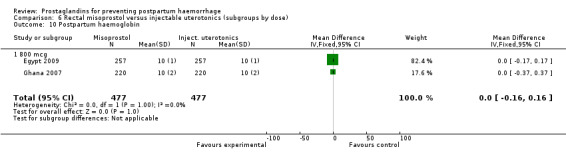

rectal misoprostol versus injectable uterotonics;

rectal misoprostol versus intramuscular prostaglandins;

sublingual misoprostol versus no uterotonics/placebo;

sublingual misoprostol versus injectable uterotonics;

intramuscular prostaglandins versus rectal misoprostol;

intramuscular prostaglandin versus no uterotonic/placebo;

intramuscular prostaglandin versus injectable uterotonics;

comparisons of different prostaglandins or different dose/routes of the same prostaglandin;

comparisons of different prostaglandins plus injectable uterotonics versus injectable uterotonics or other prostaglandins.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcomes of this review are blood loss of 1000 mL or more and the use of additional uterotonics in the third stage of labour. Maternal death is included as an outcome but it is unlikely that the review will have power to evaluate this outcome.

Reported blood loss is influenced by the assessment technique. Measurement of blood and clots in jars and weighing of linen are likely to be more precise than clinical estimation used in some studies. The latter is known to underestimate blood loss (Andolina 1999). Also, the duration of measurement and reporting the amount as 'greater than' or 'greater than or equal to' a certain cut‐off level (e.g. 500 or 1000 mL) may affect the total reported amount of blood loss especially when this amount is estimated. This becomes less of a problem for comparison between treatment and control groups when the trials blind their assessment processes.

Primary outcomes

Severe postpartum haemorrhage (at least 1000 mL);

use of additional uterotonics in the third stage of labour.

Secondary outcomes

Postpartum haemorrhage (at least 500 mL);

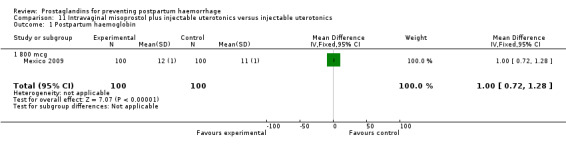

mean blood loss (mL);

blood transfusion;

manual removal of placenta;

duration of third stage (minutes);

third stage longer than 30 minutes;

any side‐effect reported;

any side‐effect requiring treatment;

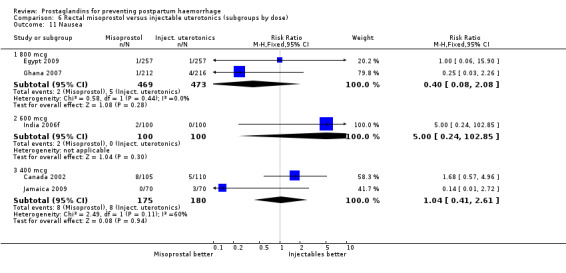

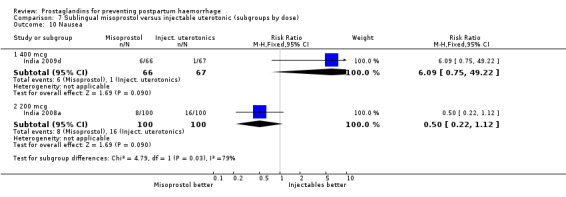

nausea;

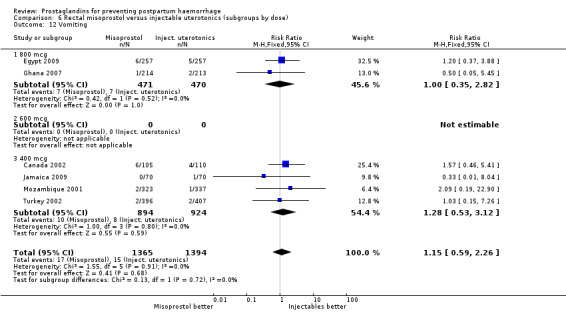

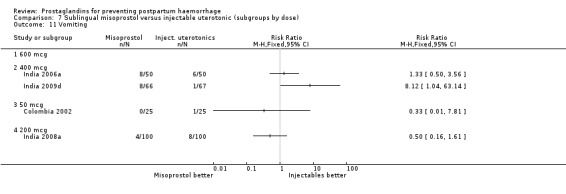

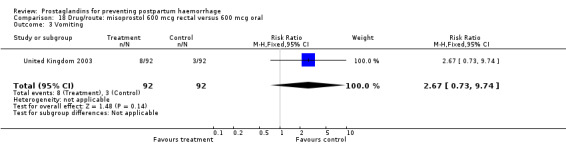

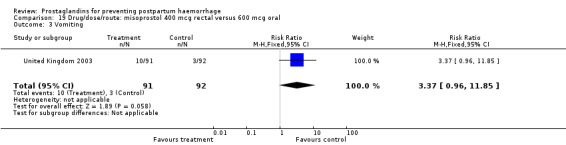

vomiting;

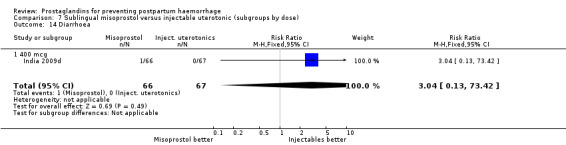

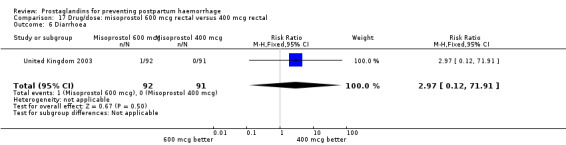

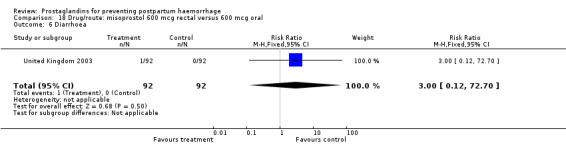

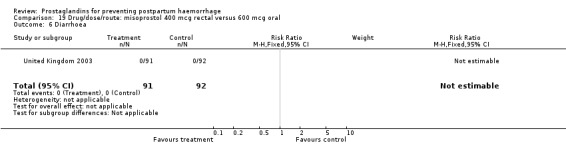

diarrhoea;

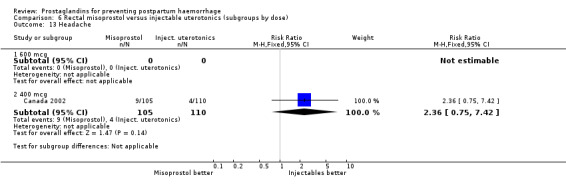

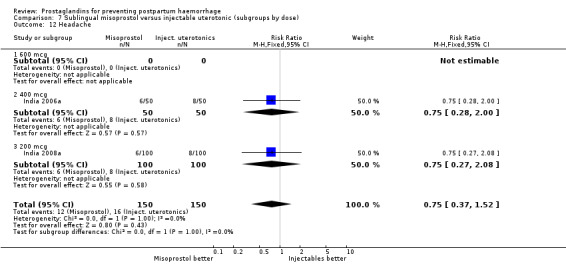

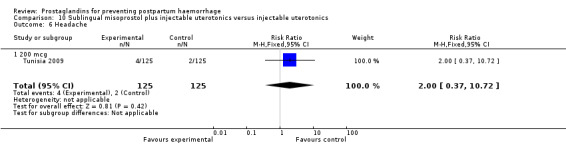

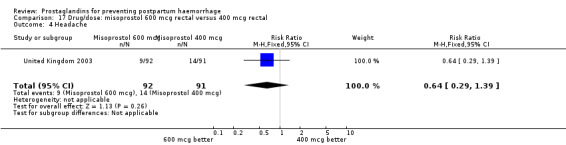

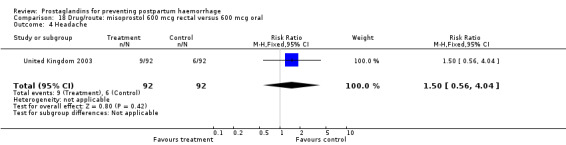

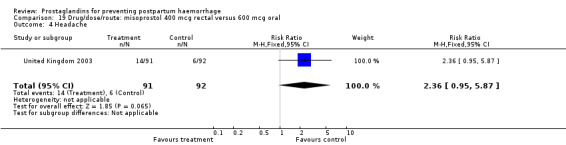

headache;

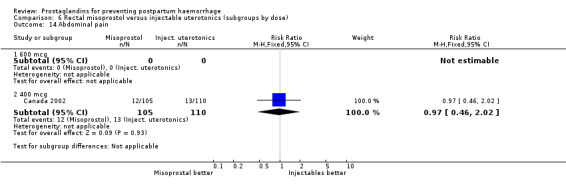

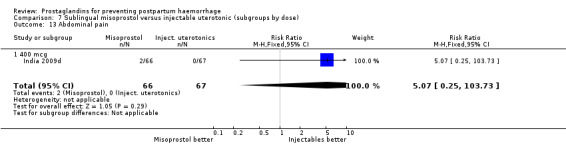

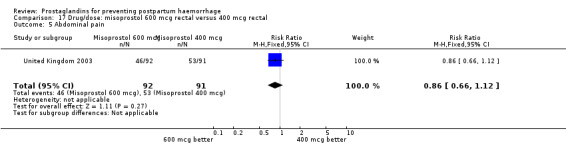

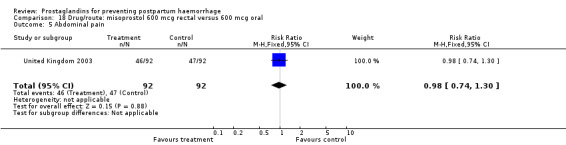

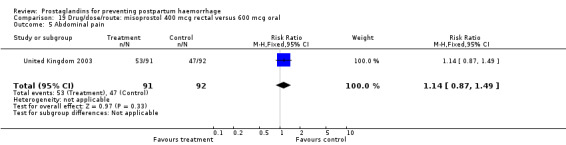

abdominal pain;

high blood pressure;

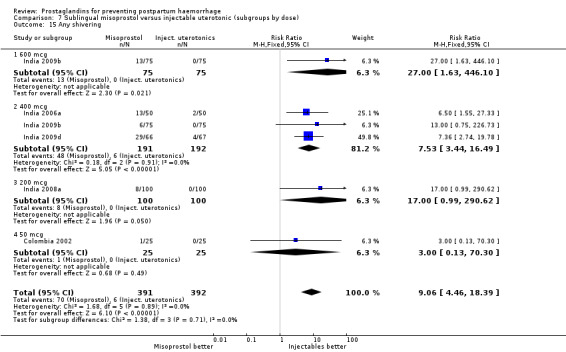

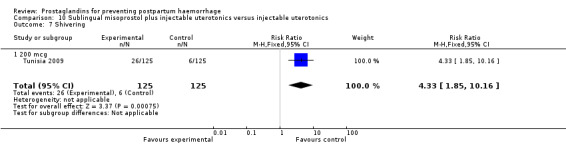

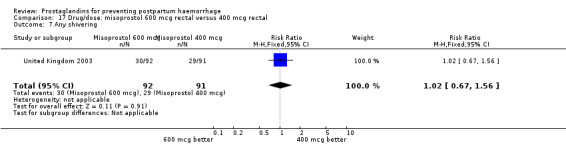

shivering;

severe shivering;

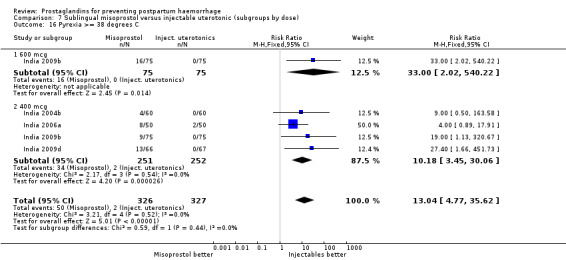

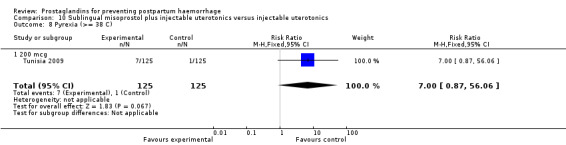

pyrexia (at least 38 ºC);

severe pyrexia (at least 40 ºC);

other.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (7 January 2011). We updated this search on 25 May 2012 and added the results to the awaiting classification section.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 1.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, by consulting the third author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third author. We entered the data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; 'as treated' analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting bias (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5))

We described for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We included cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We adjusted their sample sizes and standard errors using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we used ICCs from other sources, we reported this and conducted sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identified both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we planned to synthesise the relevant information. We considered it reasonable to combine the results from both if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely.

We also acknowledged heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and performed a subgroup analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analyzed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the protocol for this review, we specified that if heterogeneity was significant (i.e. P value less than 0.10 or I² greater than 50%), we would not use random‐effects right away and we would not total the results due to this heterogeneity. However, we discussed the trials and outcomes individually in the text.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there were 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually, and used formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes we used the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes we used the test proposed by Harbord 2006. If asymmetry was detected in any of these tests or was suggested by a visual assessment, we performed exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we planned to use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. We would have treated the random‐effects summary as the average range of possible treatment effects and discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials.

If we had used random‐effects analyses, we would have presented the results as the average treatment effect with its 95% confidence interval, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce it. Subgroup analyses were restricted to the review's primary outcomes.

We carried out the following subgroup analyses.

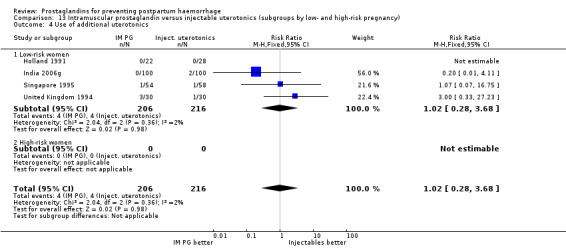

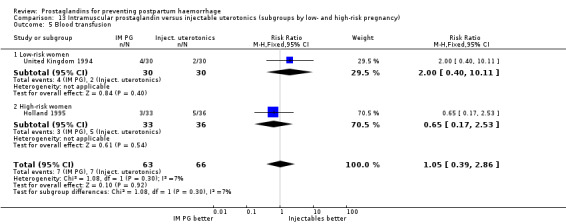

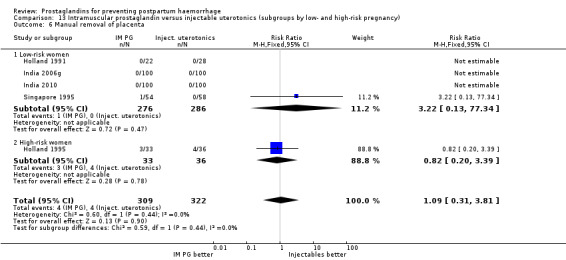

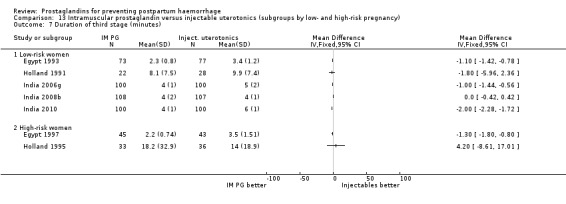

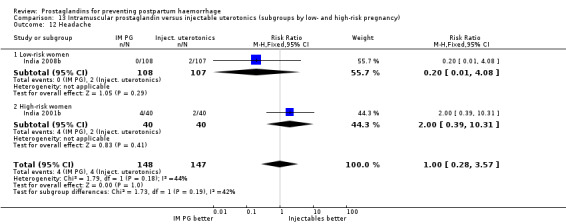

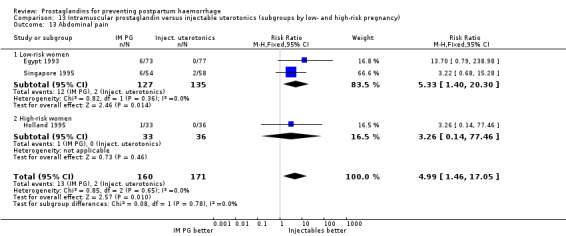

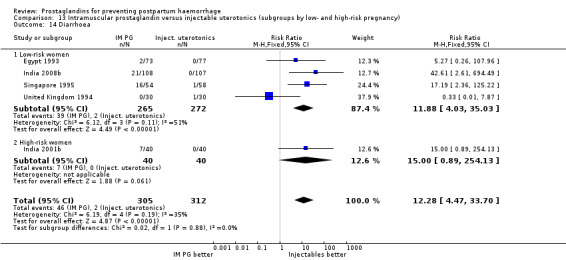

Prespecified low‐ and high‐risk group pregnancies for studies comparing injectable prostaglandins.

Different doses of misoprostol used in the studies.

Data relating to high‐ and low‐risk women were analyzed separately as well as together (totals). Recent trials (mostly misoprostol) focused on a general population of women with vaginal or caesarean section delivery without specifying any risk status. Therefore, the high‐ and low‐risk subgroupings were not used in the misoprostol comparisons. However, if future trials falling into these comparisons specifically study a risk group these subgroups will be added to the list of comparisons.

If a particular (risk) group was not specified, this implied that all women are included in that analysis regardless of their risk status. Studies that did not specify the risk status of women included are put in the low‐risk category where such distinctions are made.

In meta‐analyses with significant heterogeneity (statistical or visual), we discuss the trials individually (i.e. without totals).

Sensitivity analysis

We did not conduct sensitivity analyses for this update, because all of the larger trials in this systematic review were at low risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

Fifty‐three reports of 34 trials were identified and considered for inclusion in this updated review. Eight trials were excluded (seeCharacteristics of excluded studies table). Altogether, 26 trials were included in this 2011 update and this review now includes a total of 72 trials involving 52,678 women ‐ seeCharacteristics of included studies for details. Of these, 49 evaluated misoprostol, eight studies evaluated misoprostol plus oxytocin and the remainder evaluated injectable and intramuscular prostaglandins (12 PGF2alpha and three PGE2). One trial report remains in Studies awaiting classification (Yuan 2003). Two reports are in the Ongoing studies section. (Twelve additional reports from an updated search in May 2012 have been added to Studies awaiting classification for consideration at the next update.)

Settings

The review includes trials conducted in all continents from both low‐ to middle‐income countries and industrialized countries. Twenty‐six trials included centres in low‐ and middle‐income countries only. The WHO 2001 trial was conducted in nine countries in Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America. The Africa 2011 trial was conducted in South Africa, Nigeria and Uganda. In Africa, 10 countries contributed 20 trials (five in South Africa). Sixteen trials were conducted in India and four trials were conducted in China.

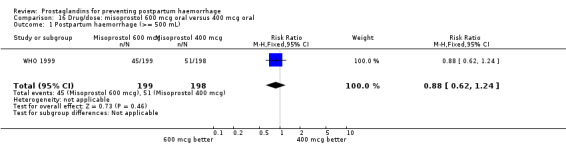

The WHO 2001 trial is the largest trial in the review with 18,530 participants from nine countries. The WHO 1999 trial is a pilot dose‐finding trial which preceded the WHO 2001 trial and used the same protocol. Side‐effects of misoprostol during the first hour after delivery from the WHO 2001 trial are included in the meta‐analyses, but further data describing side‐effects in the first 24 hours after delivery were published in a separate article and are described in the results section.

Most trials (68/72) were conducted in hospitals where births were performed by skilled caregivers. Two trials (Gambia 2005; Pakistan 2011) were community‐based. In Gambia 2005 traditional birth attendants were trained in trial procedures and blood loss measurement provided the interventions (oral misoprostol and oral ergometrine as placebo). Traditional birth attendants were trained in the management of third stage of labour in the Pakistan 2011 trial and provided 600 mcg oral misoprostol to women delivering in the community. In the Guinea‐Bissau 2005 trial, midwives administered sublingual misoprostol or placebo to women delivering at primary care centres. In the India 2006c trial, auxiliary nurse‐midwives administered oral misoprostol or placebo tablets to women delivering either at primary care centres (approximately 55%) or at home (approximately 45%).

Management of the third stage of labour

In 48 trials, the third stage was managed actively (at least two of the components of active management described, or specified as 'active'); two trials used 'expectant management' (Holland 1991; India 2006c); 10 trials did not mention management of third stage and three were mixed with components of both active or passive management used. The remaining nine trials included women with caesarean section births and did not report any particular form of management.

Risk status

Four studies specifically studied women who were at high risk for postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) (China 2003b; Egypt 1997; Holland 1995; India 2001b). The participants were classified as high risk if they had a history of PPH or conditions such as multiple pregnancy and grand multiparity.

Mode of delivery

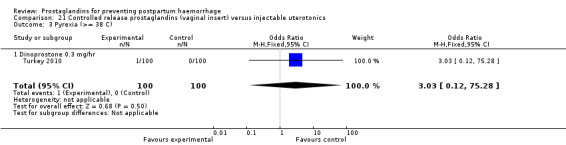

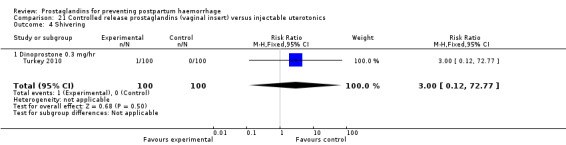

Nine trials included only caesarean section births (India 2006a; Iran 2009; Mexico 2009; Switzerland 2006; Tunisia 2009; United Kingdom 1994; United Kingdom 2001b; USA 1990; USA 2005). There were two trials which included both caesarean sections and vaginal births (China 2003b; Turkey 2010).

Blood loss assessment

The majority of the trials (n = 41) used some form of measurement, some using detailed weighing and hematin‐dye techniques. Clinical estimation was used in 25 trials, haemoglobin change or level, or both, was used in three and no method was mentioned in the remaining four trials (Colombia 2002; India 2001b; India 2005a; Mexico 2009). Overall, 11 trials used drapes to assess blood loss (China 2003b; Guinea‐Bissau 2005; India 2006c; India 2006f; India 2009d; India 2010; Iran 2009; Jamaica 2009; Tibet 2009; Tunisia 2009; United Kingdom 2001c).

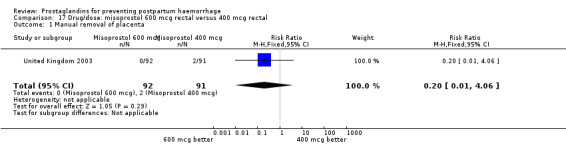

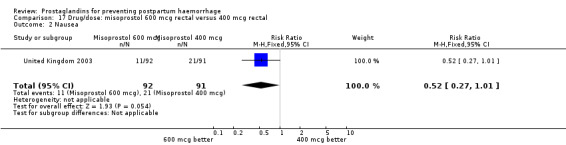

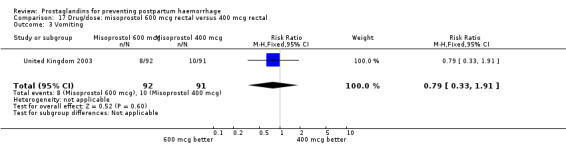

Comparisons

Of the 72 trials included in the review, 36 evaluated misoprostol in doses ranging from 50 mcg to 800 mcg and using oral, sublingual, buccal and rectal routes. Misoprostol was compared with placebo in 11 trials (China 2003a; France 2001; Gambia 2005; Guinea‐Bissau 2005; India 2006c; Pakistan 2011; South Africa 1998b; South Africa 1998c; South Africa 1998d; South Africa 2001; Switzerland 1999) and with conventional injectable uterotonics in 25 trials. It should be noted that although Gambia 2005 is grouped under placebo trials, it used oral ergometrine as a placebo. In most of the trials, the uterotonic agent was oxytocin 10 international units (IU) intramuscularly or intravenously. In some trials, the uterotonic group received oxytocin or ergometrine‐oxytocin depending on the hospital routine (Australia 1999) or depending on whether the woman was hypertensive or not (United Kingdom 2000). Some trials had several treatment arms. One of the intramuscular prostaglandin trials (Holland 1991) and two misoprostol trials (France 2001; South Africa 1998d) had three arms, one of which was a placebo control group. The WHO 1999 trial was also a three‐arm trial comparing misoprostol 600 mcg, 400 mcg orally and oxytocin 10 IU. The United Kingdom 2003 trial had three arms comparing oral misoprostol 600 mcg, rectal misoprostol 600 mcg, and rectal misoprostol 400 mcg. The India 2008a trial compared intravenous oxytocin with sublingual misoprostol in doses of 100 mcg and 200 mcg, whereas the India 2009b compared it with sublingual misoprostol in doses of 400 mcg and 600 mcg.

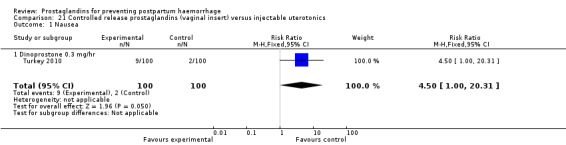

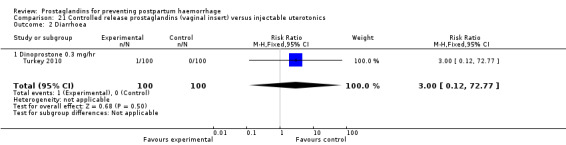

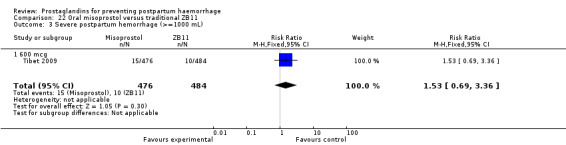

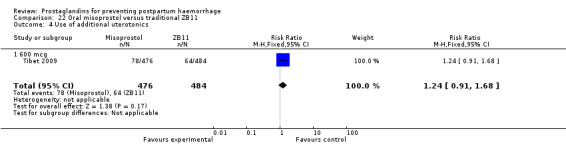

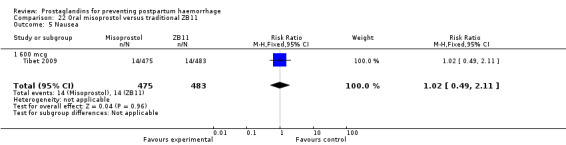

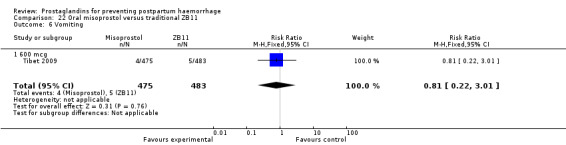

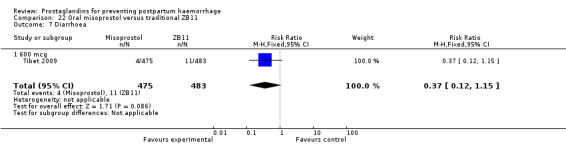

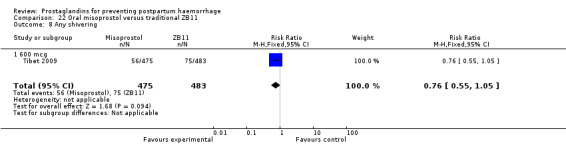

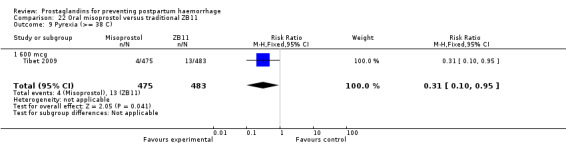

One trial compared oral misoprostol with a Tibetan traditional medicine Zhi Byed 11 (Tibet 2009) and one trial used controlled release PGE2 intravaginal insert (Turkey 2010).

Concurrent routine uterotonic use

Two trials from Turkey had four arms, comparing misoprostol 400 mcg after cord clamp followed by misoprostol 100 mcg at four and eight hours postpartum; the same regimen of misoprostol combined with intravenous oxytocin; intravenous oxytocin only; and intramuscular methyl ergometrine only. For blood loss and other early outcomes assessed before the follow‐up doses of misoprostol were given, the dosage is regarded as 400 mcg. The only differences between these two trials were that Turkey 2002 used rectal misoprostol and Turkey 2003 used oral misoprostol. The USA 2004 and USA 2005 trials compared 200 mcg buccal misoprostol with placebo in women delivering vaginally and by caesarean section respectively. All women received 20 IU oxytocin infusion at a rate of 10 mL/minute for 30 minutes and then 125 mL/hour for eight hours. Africa 2011 and Nigeria 2011 both used 400 mcg misoprostol plus oxytocin versus only oxytocin.

The review includes unpublished data from Canada 2005, South Africa 1998d, WHO 1999, United Kingdom 2000, WHO 2001 and India 2008b trials.

Risk of bias in included studies

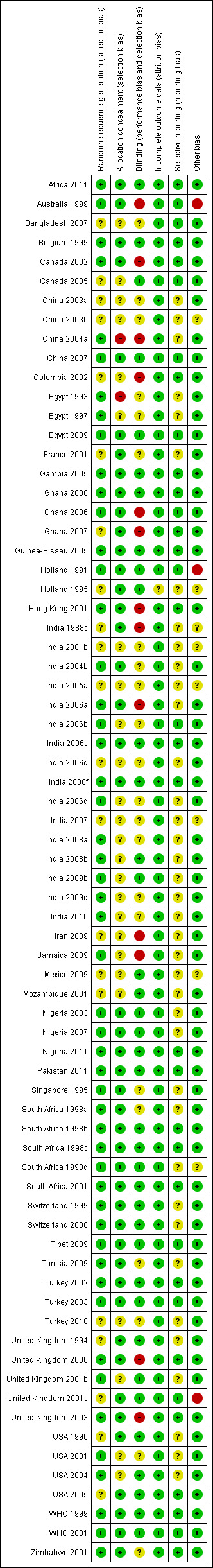

Figure 1 summarizes the risk of bias analysis for all the studies included in this review. Random sequence generation was considered adequate in 51 studies and unclear in 21 studies. Allocation concealment was considered adequate in 48 studies that used sealed envelopes, opaque containers, or identical numbered boxes containing trial medications. Holland 1995 excluded 15% of the women after randomisation, mostly due to women being randomised despite being ineligible (for augmentation of labour), and Turkey 2003 excluded 12.6% of the women after randomisation secondary to them requiring caesarean sections. There were an unspecified but small number of postrandomisation exclusions in South Africa 1998a. These were due to hypertension being discovered after randomisation, which resulted in the exclusion of some women allocated to ergometrine‐oxytocin.

1.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

In trials evaluating different interventions in the third stage of labour, PPH is often the primary outcome. Assessment of PPH is prone to bias if the staff making the assessments are not blind to the intervention. In this review, all outcome assessments were blinded in 21 trials. Some outcome assessments were blinded in two trials.

In this review, trials comparing misoprostol with other uterotonics are, in essence, equivalence trials designed to evaluate whether misoprostol is as effective as others given its advantage of oral or rectal route of administration. The majority of such trials have set relatively large margins of equivalence and are therefore, in practical terms, underpowered to test an equivalence hypothesis. The WHO 2001 trial is the largest trial in the review which set an a priori clinical equivalence margin (within 35% efficacy of oxytocin). In this trial the primary outcomes were blood loss greater than or equal to 1000 mL and the use of additional uterotonics. Misoprostol versus placebo or no treatment trials are superiority trials and do not have the problem mentioned above.

The South African trials and the United Kingdom 2001b trial evaluating oral misoprostol used non‐identical placebos. The women participating in the South African trials took the medications out of an opaque container with care being taken to conceal the tablets from midwives. Although this method of blinding is not 100% safe, the authors provided the review authors with the information that unblinding was unlikely to occur in the settings in which the trials were conducted. In the United Kingdom 2001b trial, side‐effect assessments were blinded.

One study (Holland 1995) was stopped prematurely before reaching a prespecified interim analysis to determine an appropriate sample size. This was due to the manufacturer of the drug issuing a warning about serious cardiovascular side‐effects after intramuscular use of sulprostone, a synthetic PGE2 derivative. Another study (Australia 1999), was stopped after recruitment of 863/1862 women following the unsatisfactory results of an interim analysis.

Effects of interventions

The results are based on 37 misoprostol and nine intramuscular prostaglandin trials.

Misoprostol trials

Primary outcomes

Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment (11 trials, comparisons 01, 02, 03, 04)

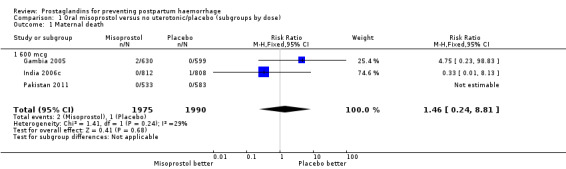

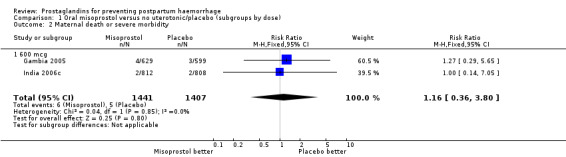

Oral misoprostol was used in seven trials (comparison 01: 6225 women total, 5325 in six 600 mcg trials), rectal (comparison 02), sublingual (03) and buccal (04). There were three maternal deaths in misoprostol and one in placebo groups overall in nine trials.

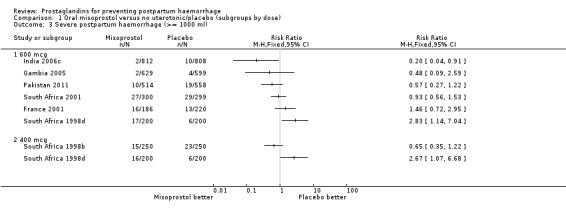

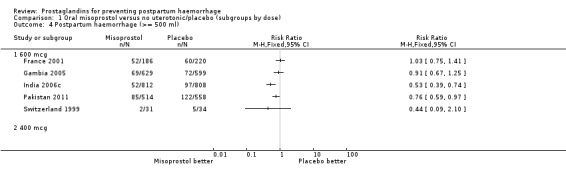

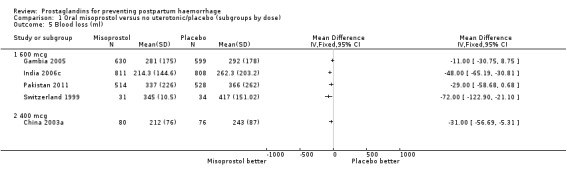

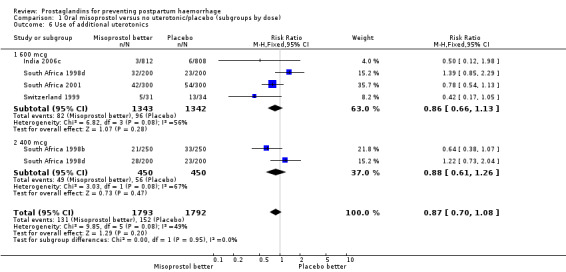

There was significant statistical heterogeneity for the outcome severe postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) in the oral misoprostol versus placebo comparison. Earlier trials (France 2001; South Africa 1998d; South Africa 2001) did not indicate any reduction in severe PPH while the more recent Gambia 2005 (risk ratio (RR) 0.48; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.09 to 2.59, 2/629 versus 4/599) and India 2006c (RR 0.20; 95% CI 0.04 to 0.91, 2/812 versus 10/808) and Pakistan 2011 (RR 0.57; 95% CI 0.27‐1.22, 10/514 versus 19/558) trials suggest some protective effect of misoprostol on severe PPH. The use of additional uterotonics was less when misoprostol was used in four out of six trials but not in the South Africa 1998d trial that had both 600 and 400 mcg treatment arms. As South Africa 1998d is the only study in this comparison suggesting superiority of placebo over oral misoprostol, which is biologically implausible, we re‐conducted the analyses excluding this study for the primary outcomes. Oral misoprostol was protective against the use of additional uterotonics (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.08, five trials, 3585 women) compared with the placebo group. Compared with placebo, oral misoprostol reduced the need for blood transfusions required (RR 0.31; 95% CI 0.10 to 0.94, four trials, 3519 women).

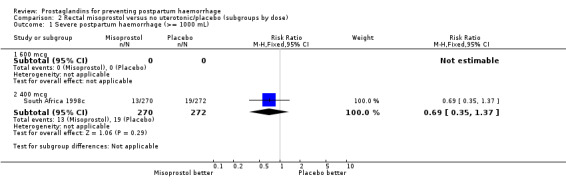

One rectal misoprostol trial South Africa 1998c using 400 mcg did not show a statistically significant difference in severe PPH (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.35 to 1.37).

The Guinea‐Bissau 2005 trial used 600 mcg sublingual misoprostol and showed a statistically significant difference in reducing severe PPH (RR 0.66; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.98, 37/330 versus 56/331).

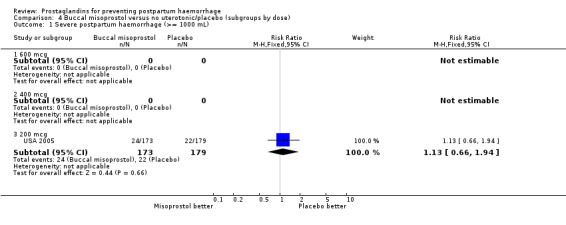

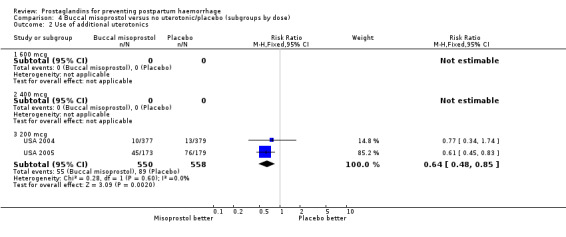

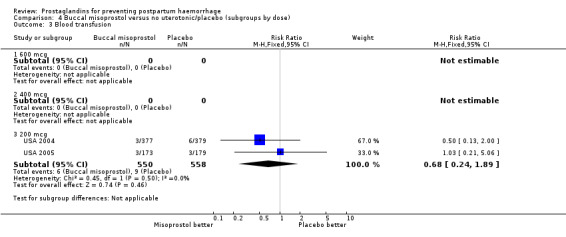

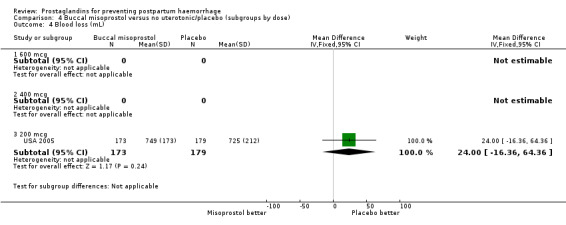

The USA 2004 and USA 2005 trials used 200 mcg buccal misoprostol in women undergoing vaginal delivery and caesarean section respectively. All women received 20 IU oxytocin infusion in 1 litre of saline. In the USA 2005 trial there were 24/173 versus 22/179 cases of severe PPH in the misoprostol and placebo groups respectively, whereas there were no cases of severe PPH in the USA 2004 trial. In both trials the protocol included oxytocin infusion after delivery of the placenta.

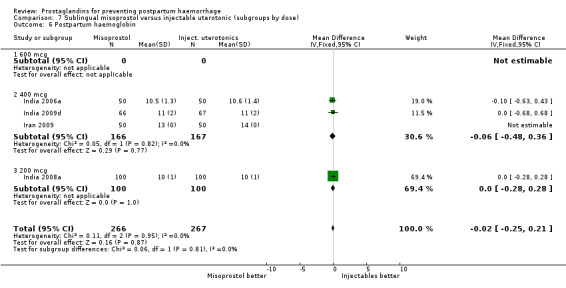

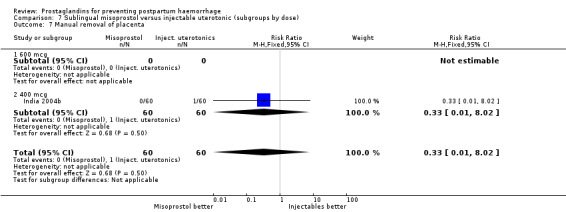

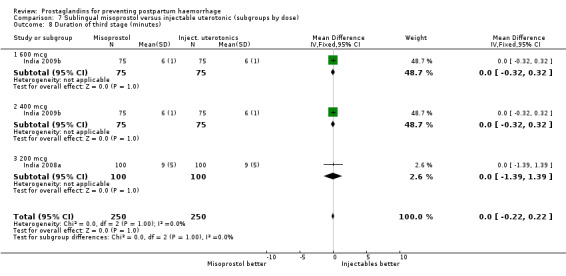

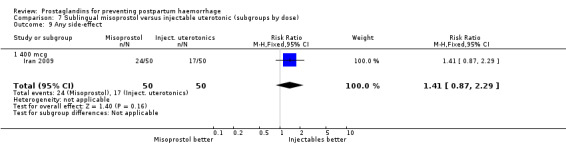

Misoprostol versus conventional injectable uterotonics (39 trials, comparisons 05, 06, 07)

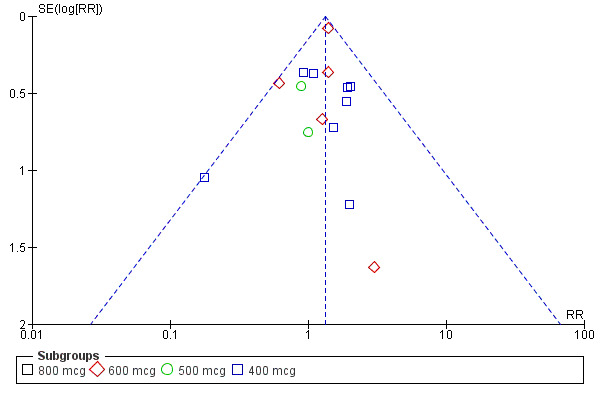

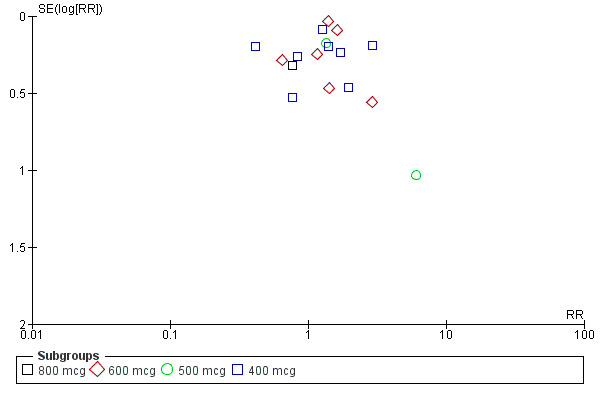

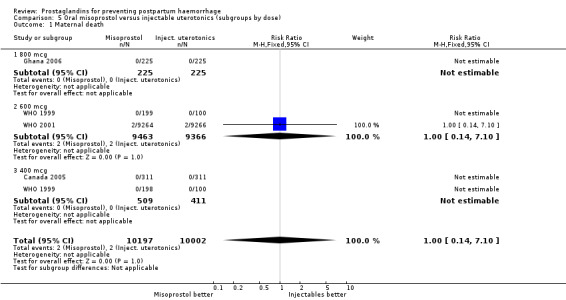

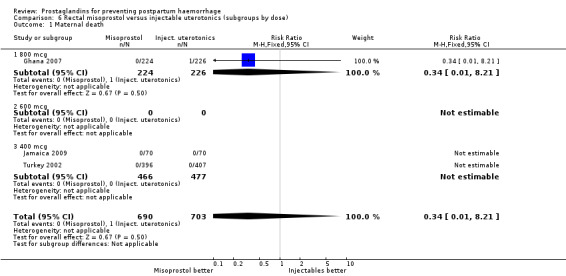

Twenty‐one trials compared oral misoprostol (comparison 05), 10 compared rectal (comparison 06) and eight compared sublingual (comparison 07) with injectable uterotonics (oxytocin intramuscular or intravenous, ergometrine, ergometrine + oxytocin). Maternal deaths were reported only in the WHO 2001 trial (2/9264 versus 2/9266) and Ghana 2007 (0/224 versus 1/226). There were no deaths in the Ghana 2006, Canada 2005, Turkey 2002 and WHO 1999 trials. The other trials did not mention whether or not there were any deaths. The funnel plots for the primary outcomes suggest no publication bias (Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

Funnel plot of comparison: 5 Oral misoprostol versus injectable uterotonics, outcome: 5.2 Severe postpartum haemorrhage (>= 1000 ml).

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 5 Oral misoprostol versus injectable uterotonics, outcome: 5.5 Use of additional uterotonics.

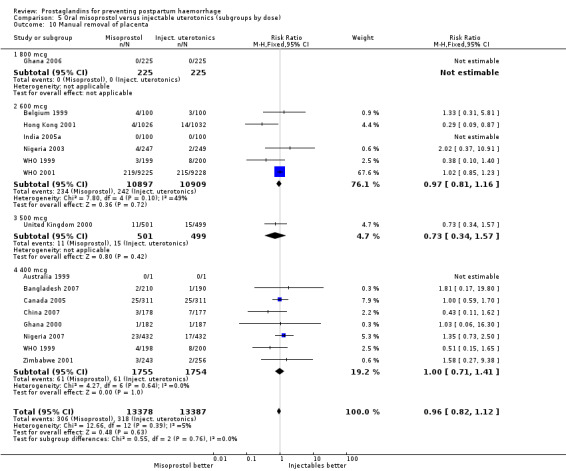

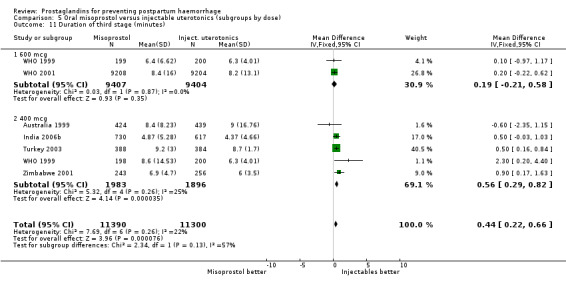

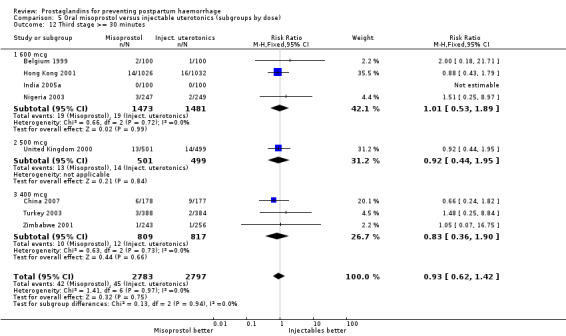

Oral misoprostol was associated with a statistically significant higher risk of severe PPH (RR 1.33; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.52, 17 trials, 29,797 women). While the large WHO 2001 trial results dominated the meta‐analysis, the majority of trials showed similar results with no statistically significant heterogeneity across different doses or trials. Although the results were not totalled due significant statistical heterogeneity, overall, the use of additional uterotonics showed a similar trend among different dose groups. There was also a trend towards fewer blood transfusions with misoprostol (RR 0.84; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.06, 15 trials, 28,213 women).

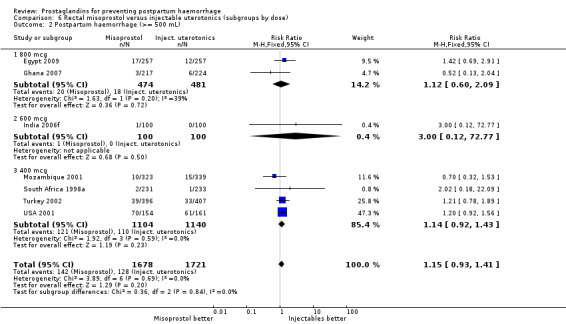

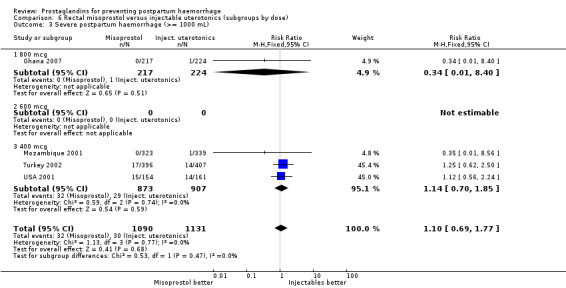

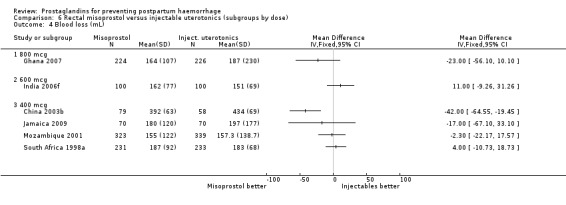

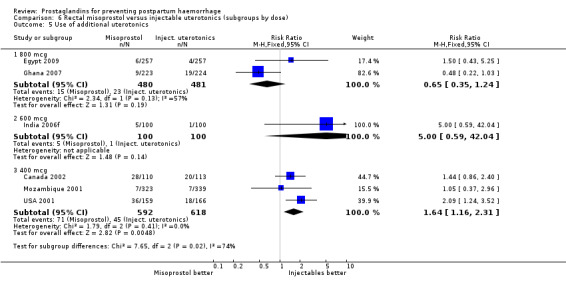

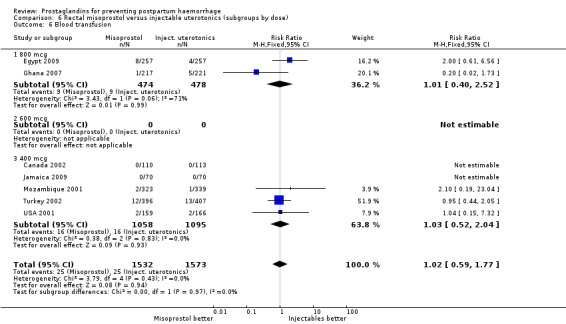

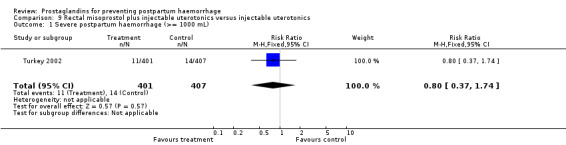

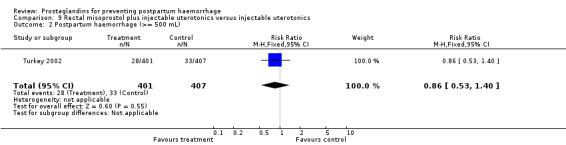

Three 400 mcg rectal misoprostol versus injectables trials reported on severe PPH and there were similar numbers of women with this outcome in the two groups (RR 1.14; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.85, three trials, 1780 women). More women who received misoprostol required additional uterotonics (RR 1.64; 95% CI 1.16 to 2.31). One study using 800 mcg rectal misoprostol (Ghana 2007) reported only one case of severe PPH reported in the control group.

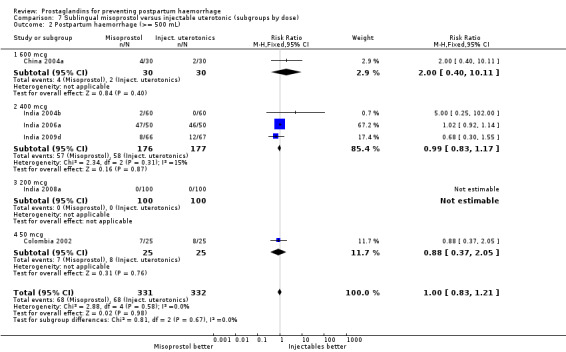

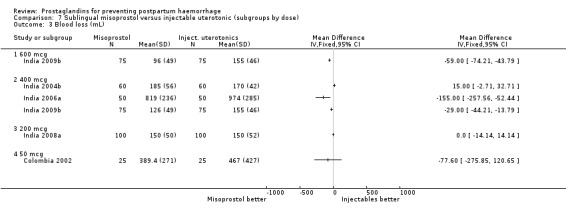

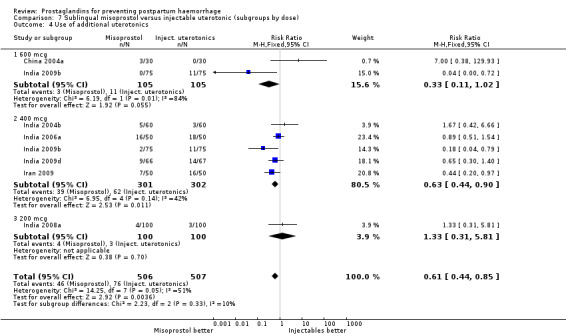

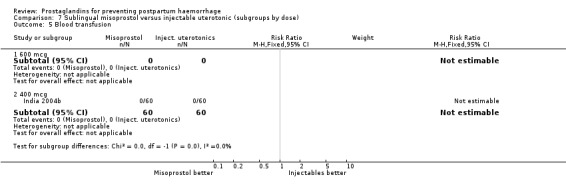

Seven trials compared sublingual misoprostol versus injectables. Use of additional uterotonics reported by all the trials were less likely among misoprostol group compared with injectables (RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.44 to 0.85, seven trials, 1013 women).

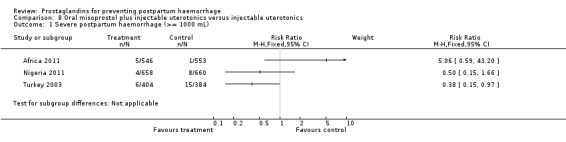

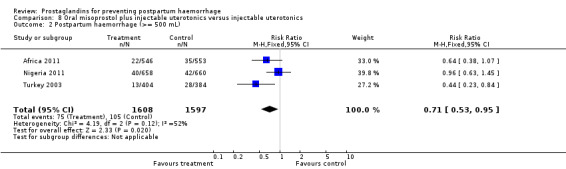

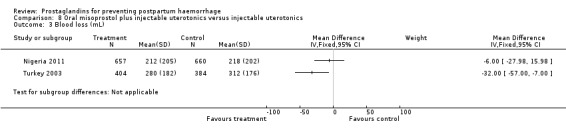

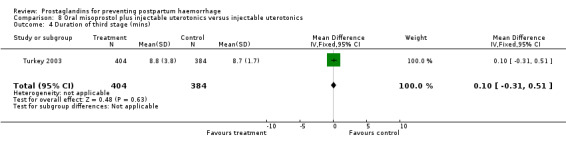

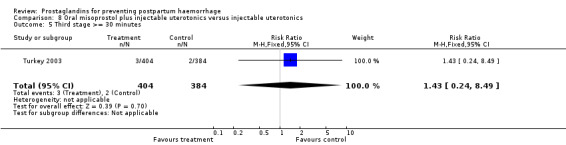

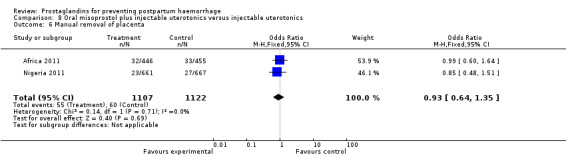

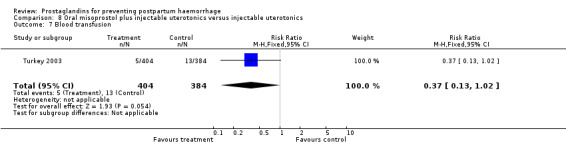

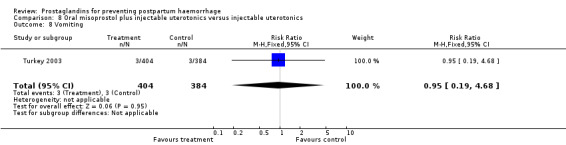

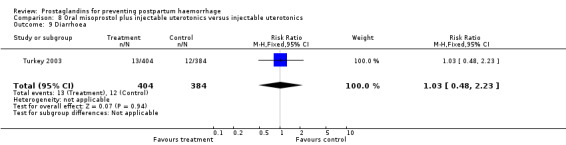

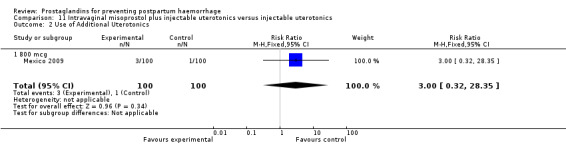

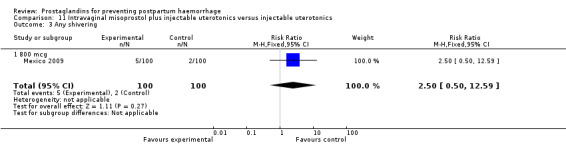

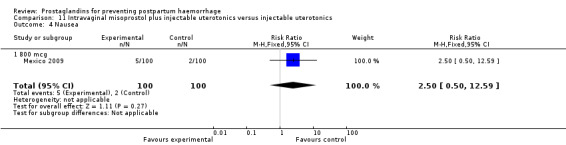

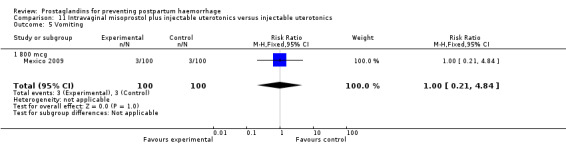

Concurrent routine uterotonic use (comparisons 08, 09, 10 and 11)

Oral misoprostol combined with oxytocin were compared with conventional uterotonics in the Africa 2011, Nigeria 2011 and Turkey 2003 trials. Oral misoprostol when combined with oxytocin was more effective than placebo and oxytocin in decreasing PPH (RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.53 to 0.95, three trials, 3205 women) and although not totalled due to heterogeneity, a similar trend can be observed for severe PPH. It should be noted here that for outcomes assessed within four hours, including all blood loss outcomes, the effective dose was 400 mcg in Africa 2011 and Nigeria 2011, whereas Turkey 2003 added 100 mcg to the initial 400 mcg dose after four and eight hours.

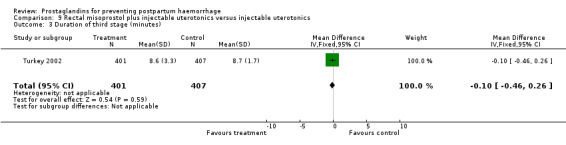

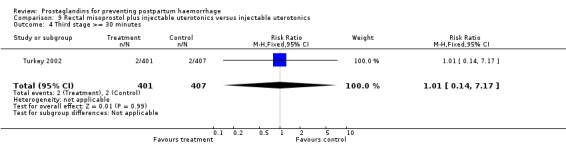

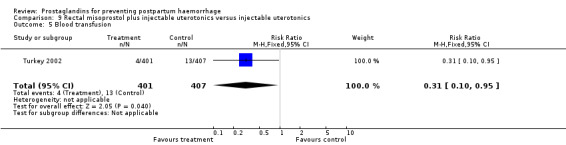

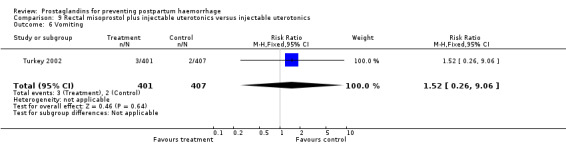

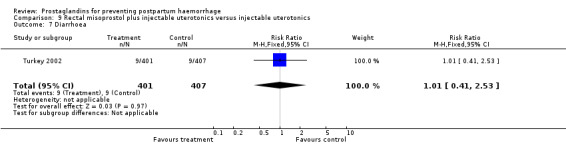

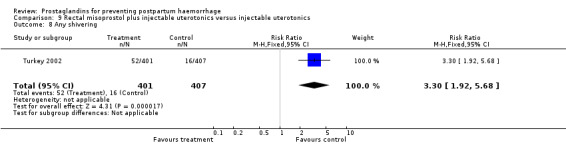

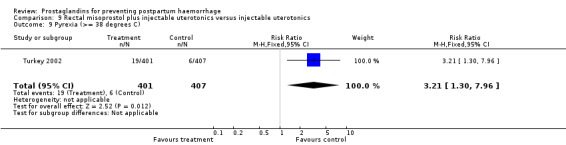

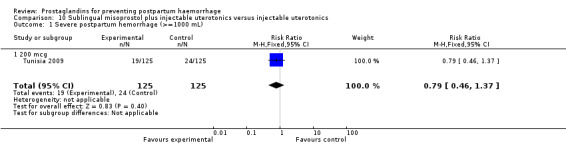

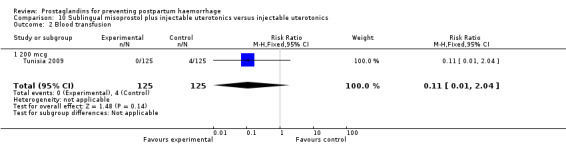

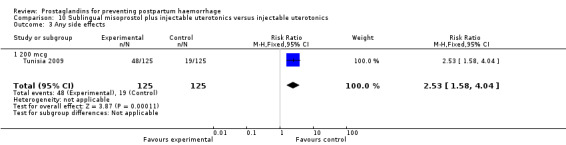

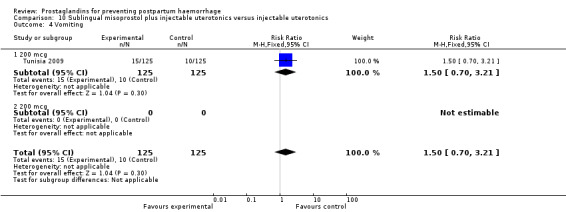

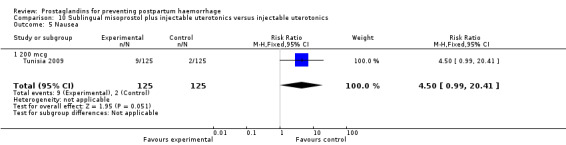

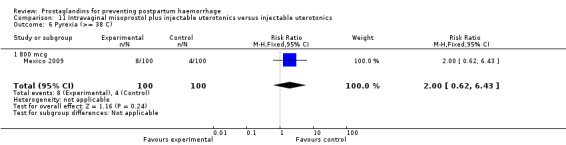

The Turkey 2002 trial compared rectal misoprostol and oxytocin, Tunisia 2009 compared sublingual misoprostol and oxytocin with conventional uterotonics in women who had caesarean sections, whereas Mexico 2009 used a combination of intravaginal misoprostol and oxytocin.

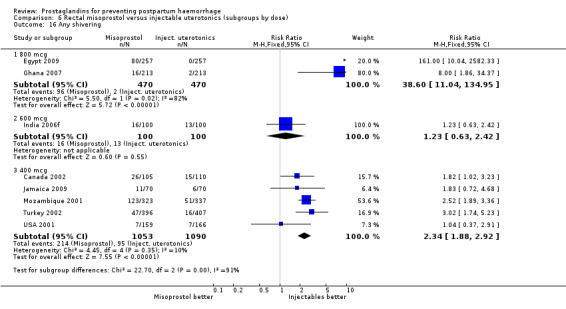

Side‐effects

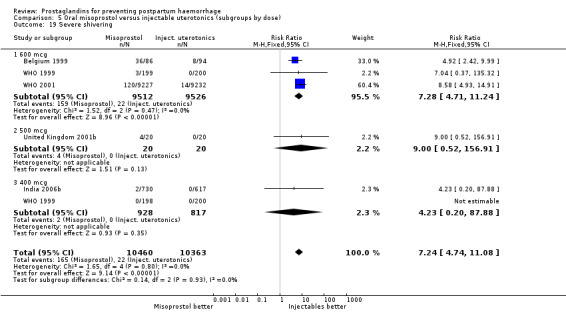

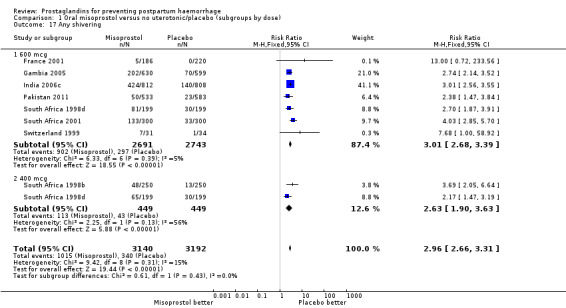

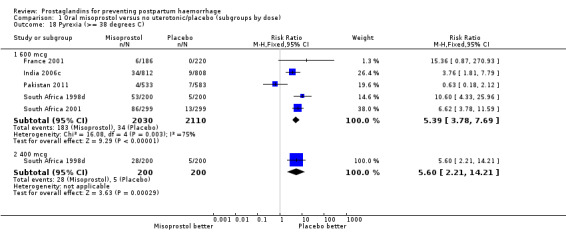

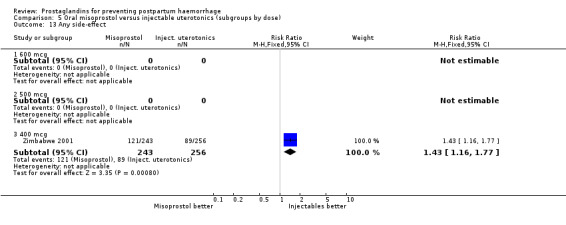

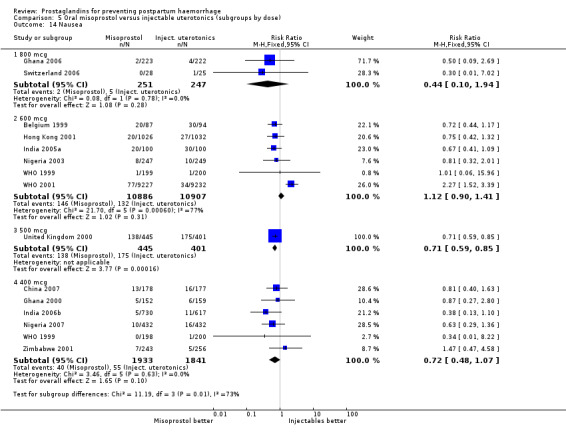

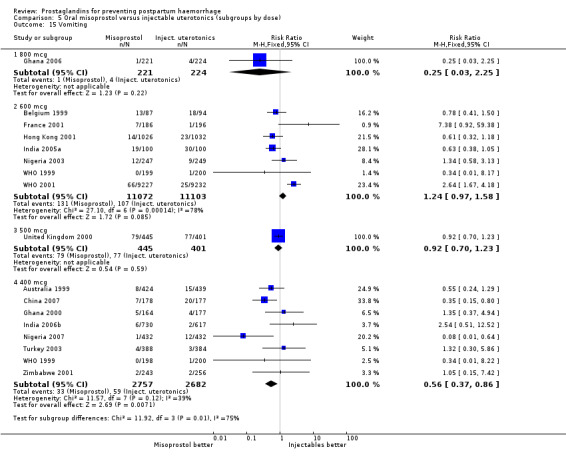

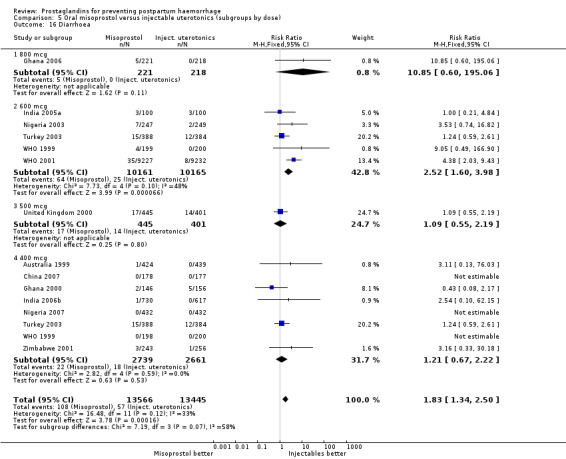

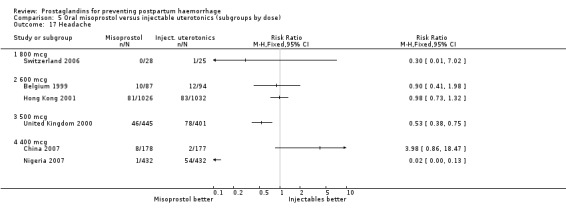

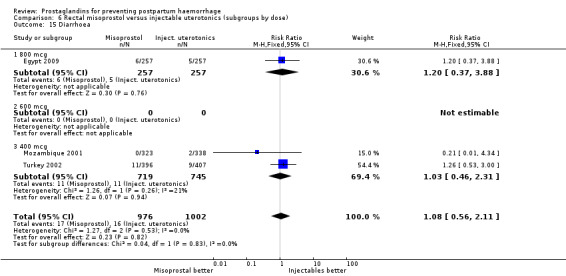

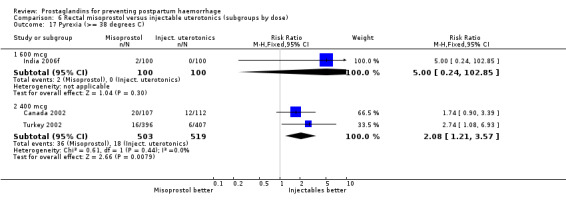

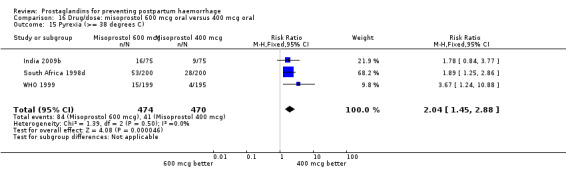

Oral misoprostol 600 mcg was consistently associated with higher rates of prostaglandin‐related side‐effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea as well as for 'any' shivering, severe shivering and pyrexia (greater than 38 °C) when compared with placebo as well as with conventional uterotonics. Not all of the side‐effects were totalled due to heterogeneity under Comparison 5.0, however, in the meta‐analyses both severe shivering and diarrhoea were more likely to occur among the misoprostol group participants: RR 7.24; 95% CI 4.74‐11.08, five trials, 20823 women and RR: 1.83; 95% CI 1.34‐2.50; 13 trials, 27011 women, respectively. For 'any' shivering, the individual trial RRs ranged between 1.43 and 69.10.

Further analysis of side‐effects during the first 24 hours in the WHO 2001 trial showed that in comparison to oxytocin, women who received misoprostol had a higher incidence of 'any' shivering (RR 4.70; 95% CI 1.90 to 11.20), and of pyrexia (RR 6.3; 95% CI 3.70 to 10.80) in the period two to six hours after delivery. Diarrhoea was also more common in the misoprostol group in the period two to six hours (RR 21.00; 95% CI 5.10 to 86.50) and seven to 12 hours (RR 7.70; 95% CI 2.30 to 25.40).

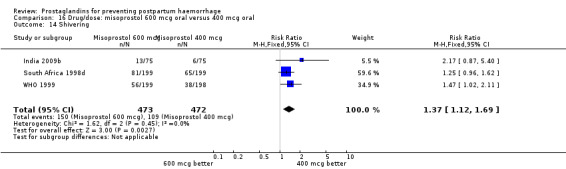

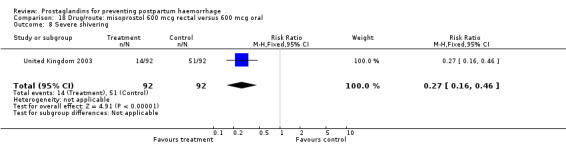

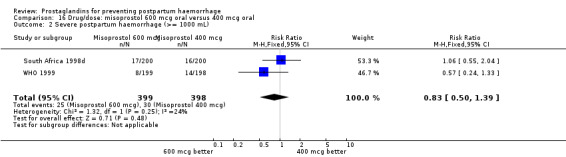

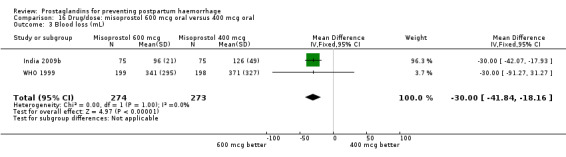

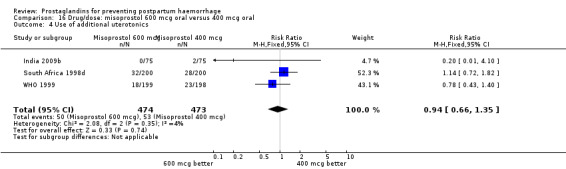

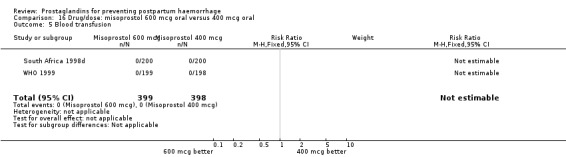

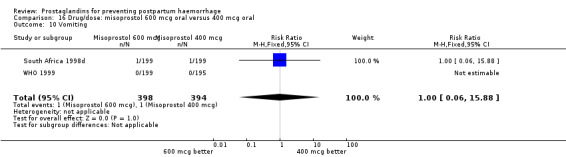

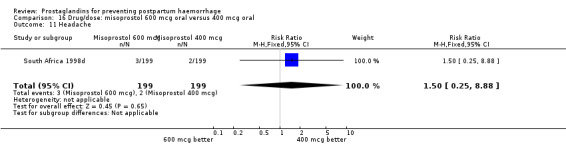

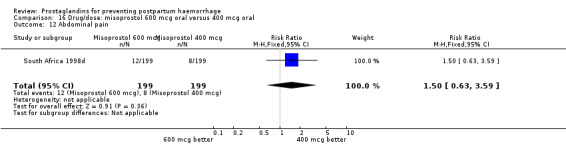

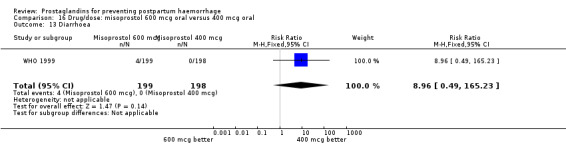

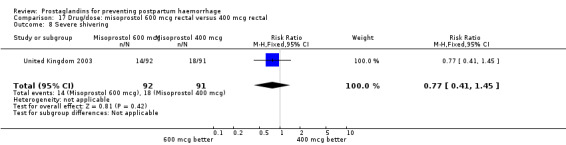

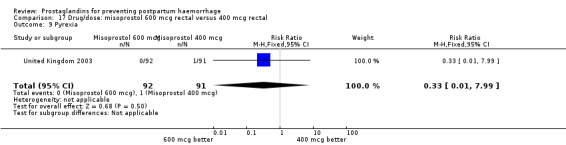

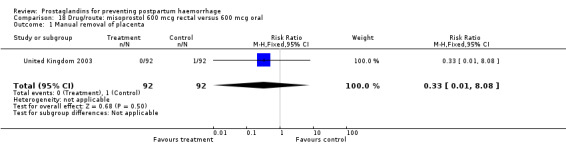

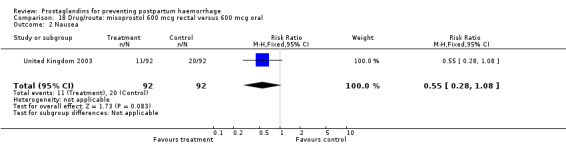

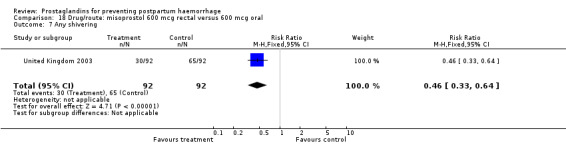

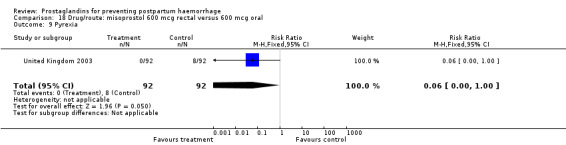

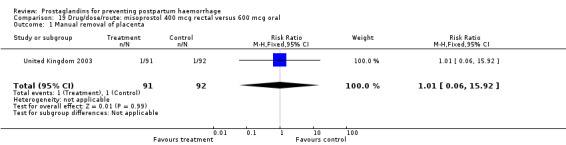

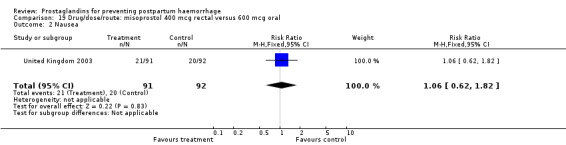

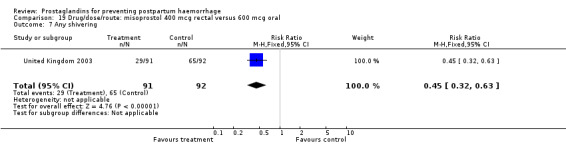

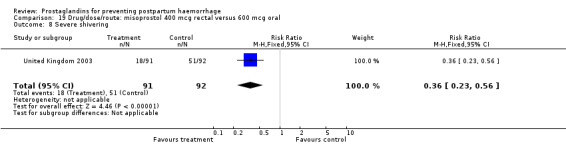

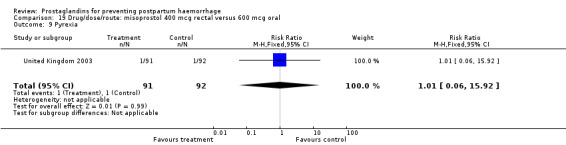

The results of three trials (India 2009b; South Africa 1998d; WHO 1999) where 600 mcg and 400 mcg doses of oral misoprostol were compared indicate that side‐effects are dose‐related (any shivering RR 1.37; 95% CI 1.12 to 1.69) (Analysis 16.14). This might not apply, however, to rectal misoprostol, as there were no significant differences in the one trial (United Kingdom 2003) that evaluated 600 mcg and 400 mcg doses of rectal misoprostol. A comparison of 600 mcg rectal versus 600 mcg oral misoprostol in the same trial showed that rectal misoprostol resulted in less pyrexia, 'any' shivering, and severe shivering (RR 0.27; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.46) (Analysis 18.8) than oral misoprostol. Severe shivering was also observed more frequently among all different doses of misoprostol compared with injectable uterotonics (Analysis 5.19).

16.14. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Drug/dose: misoprostol 600 mcg oral versus 400 mcg oral, Outcome 14 Shivering.

18.8. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Drug/route: misoprostol 600 mcg rectal versus 600 mcg oral, Outcome 8 Severe shivering.

5.19. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Oral misoprostol versus injectable uterotonics (subgroups by dose), Outcome 19 Severe shivering.

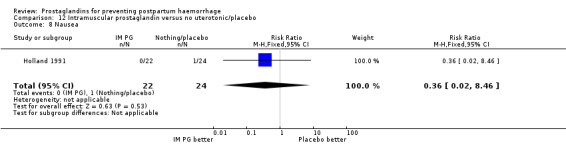

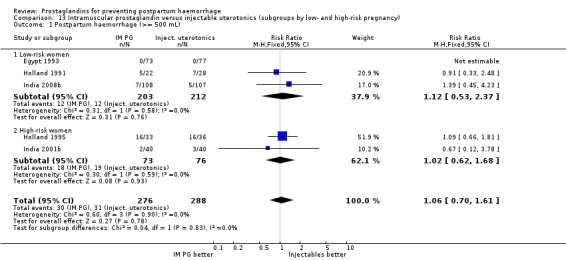

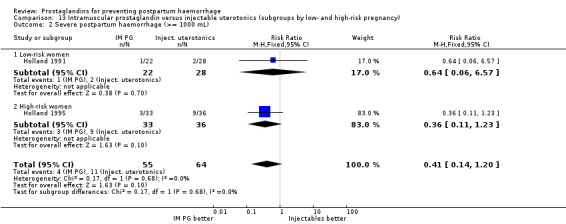

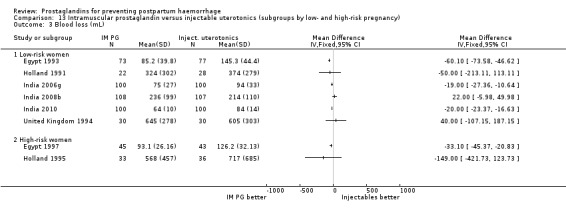

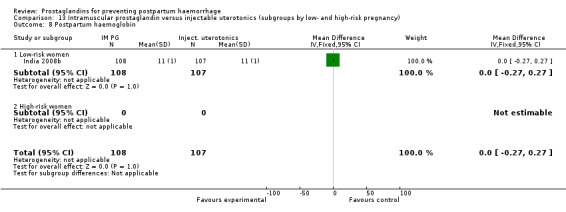

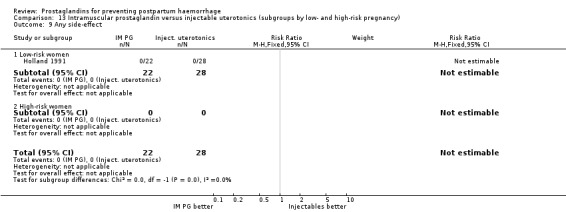

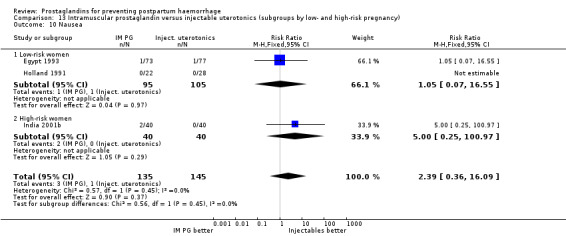

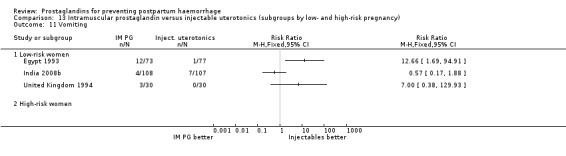

Intramuscular prostaglandin trials (comparisons 12, 13, 14, 15)

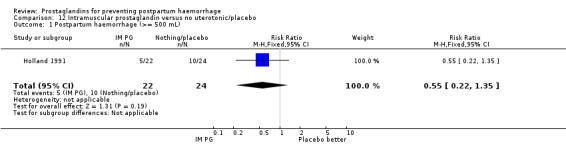

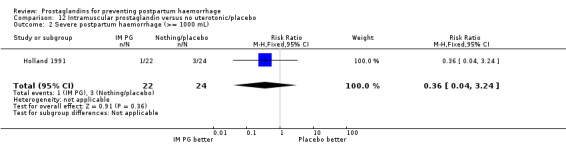

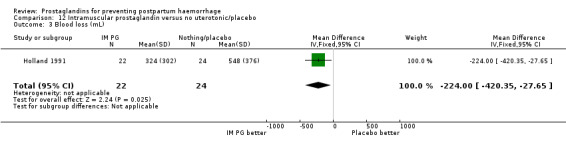

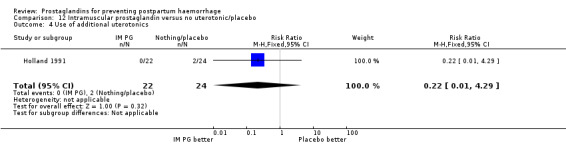

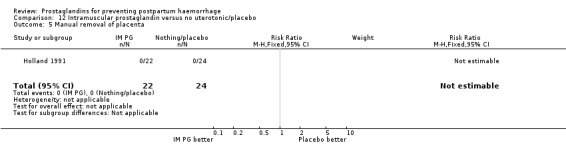

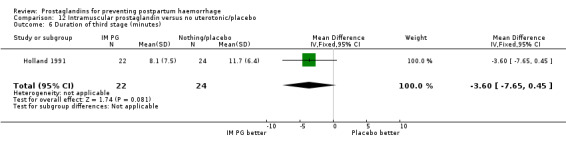

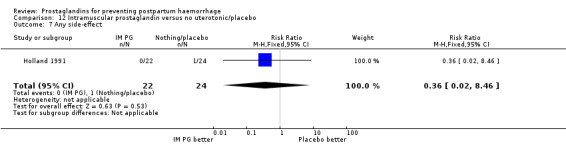

One trial (Holland 1991) was a three‐arm trial with a placebo arm in addition to sulprostone and oxytocin. Thirteen trials compared injectable prostaglandins with conventional injectable uterotonics. The occurrence of primary outcomes such as a blood loss of 1000 mL or more and the use of additional uterotonics were too few to give reliable estimates.

Intramuscular prostaglandins had less mean blood loss when compared with no uterotonic use in the one trial with 46 women (Holland 1991) that examined this outcome (‐224 mL mean difference (MD); 95% CI ‐420.35 to ‐27.65 mL). Other outcomes evaluated in this study were not statistically significant.

When compared with conventional uterotonics, intramuscular prostaglandins resulted in less blood loss and shorter duration of the third stage of labour (‐1.25 minutes MD; 95% CI ‐1.42 to ‐1.08 minutes). Blood loss data were not totalled because of heterogeneity due to one small trial having the results in the opposite direction. Five other trials showed less blood loss with injectable prostaglandin.

Vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea were more common with intramuscular prostaglandins.

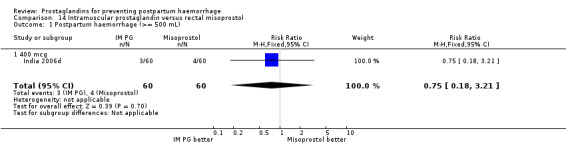

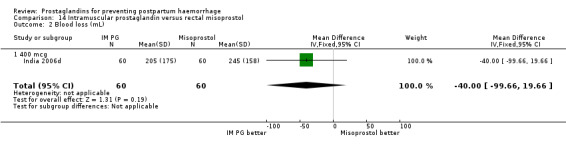

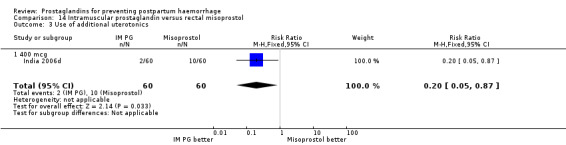

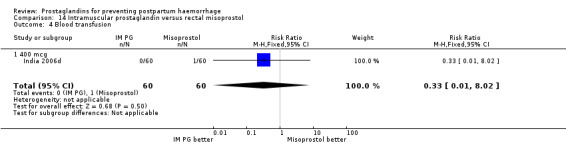

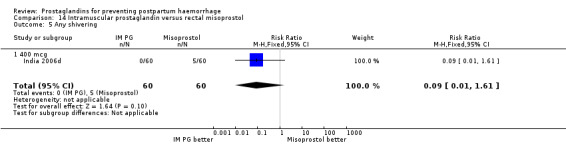

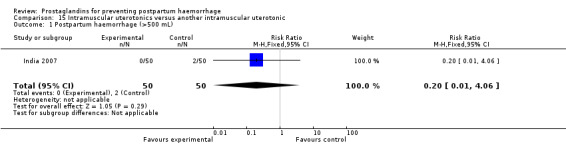

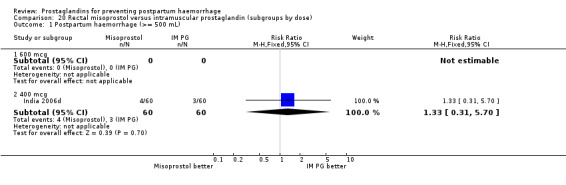

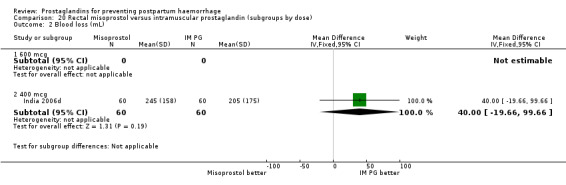

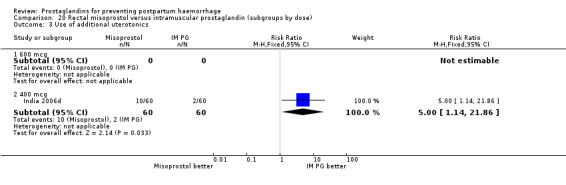

Intramuscular prostaglandin F2alpha was compared with rectal misoprostol 400 mcg in one small trial with 120 women (India 2006d). There were more women requiring additional uterotonics (2/60 versus 10/60) but the study was too small to give any guiding evidence. Another small trial compared intramyometrial injection of PGF2alpha with intramyometrial oxytocin in women having caesarean section births (USA 1990).

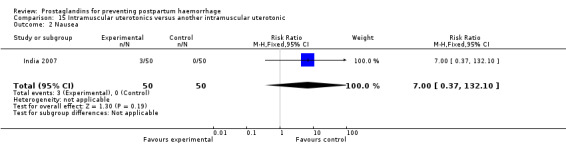

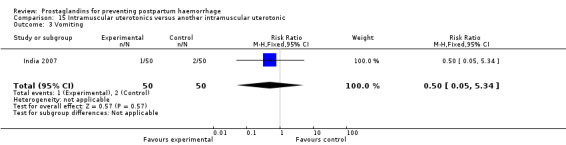

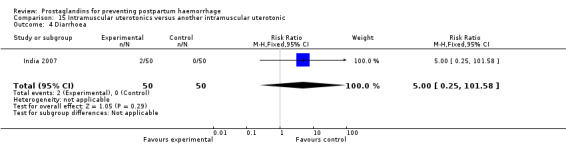

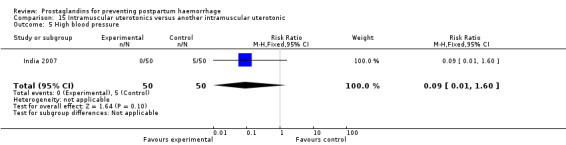

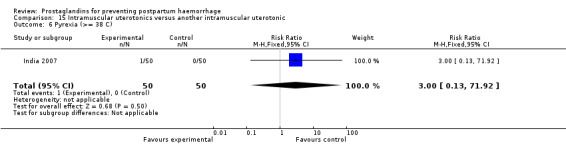

One small study compared two different intramuscular prostaglandins and observed that intramuscular carboprost was less likely to result in PPH (less than 500 mL) but more likely to cause nausea and diarrhoea compared with intramuscular methylergometrine maleate (MEM) (India 2007).

Discussion

This review includes comparisons of intramuscularly, orally, and rectally administered prostaglandins with placebo, and with conventional injectable uterotonics. We did not combine misoprostol with other prostaglandins in the meta‐analyses. Misoprostol tablets are used via oral, rectal, sublingual or buccal routes while other prostaglandins are used intramuscularly (or intramyometrial during caesarean section). In terms of outcomes, we gave emphasis to blood loss of at least 1000 mL and the use of additional uterotonics as the most clinically relevant outcomes. We recorded maternal death data systematically but did not anticipate having sufficient power to analyse this outcome.

Misoprostol for PPH prevention in the community: While the results of earlier trials comparing misoprostol (used orally or rectally) with placebo or no treatment were somewhat equivocal, the results of the recent trials are more promising (Gambia 2005; Guinea‐Bissau 2005; India 2006c; Pakistan 2011). It is important to note that all four recent trials have design and setting differences that make the summing up of their results difficult. The Gambia 2005 trial had a lower than expected number of events and although the direction of effect favours misoprostol the trial is not powered adequately. In addition, oral ergometrine was assumed to be equivalent to placebo and although the value of oral ergometrine is questionable (WHO 1994), it may not be zero. However, we kept this comparison in the misoprostol versus placebo comparison, because the authors' a priori assumption was that the direction and the pharmacokinetics of oral ergometrine suggests that it is unlikely to be effective. The third stage management was 'active'. This trial is the one of the two trials that used traditional birth attendants to administer the trial interventions. The Guinea‐Bissau 2005 trial used sublingual misoprostol within the context of active management and showed greater effect with higher blood loss (i.e. 1000 mL compared to 500 mL). Almost half of the women in this trial (150/330 and 170/331 in the misoprostol and placebo groups) experienced blood loss of 500 mL or more which is unusual in postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) trials with active management. The India 2006c trial used oral misoprostol in the context of 'expectant' management of the third stage of labour. Therefore, its findings are more applicable to settings where this type of third stage management is the norm. It is not known whether with other components of active management being in place the same magnitude of effect would hold or not. The Pakistan 2011 trial used 600 mcg oral misoprostol versus placebo delivered via traditional birth attendants at home births and the third stage management was 'active'. Recent analysis by Hofmeyr et al. using the data from 46 studies included in the earlier version of this review concluded that 400 mcg of misoprostol were found to be safer than doses larger than 600 mcg and just as effective (Hofmeyr 2009).

With the addition of four non‐hospital based trials, it is possible to make some inferences for those settings although all four trials have important differences. All four trials were conducted either at home or at primary care centres and it is reassuring to see that there were no major adverse events related to misoprostol use. The Guinea‐Bissau, Pakistan and India trials were conducted by caregivers trained in third stage management although only the Guinea‐Bissau 2005 had fully qualified midwives.

The addition of several smaller misoprostol versus injectable uterotonic trials confirm the findings of the earlier version of the review. Overall, injectable uterotonics are more effective than misoprostol. Various injectables were used in the included trials. The data with regard to the comparative efficacy of oxytocin 10 international units (IU) versus ergometrine suggest that there are no major advantages of either of them (McDonald 2004). Ergot preparations seem to be somewhat more effective in reducing blood loss but are associated with a higher rate of side‐effects and the choice should be made according to the trade‐off between the benefit and harm (Carroli 2001).

The results of the large WHO 2001 trial, conducted in nine countries with the participation of 18,530 women, dominate the systematic review's comparison between misoprostol 600 mcg and injectable uterotonics, mostly 10 IU of oxytocin. This comparison demonstrates that oral misoprostol up to 600 mcg is associated with a higher risk of blood loss and the use of additional uterotonics (up to 16% of women will require additional uterotonic treatment) when compared with a policy of injectable uterotonics. There is a consistent increase in all prostaglandin‐related side‐effects. Considering that the observed rate of side‐effects is already high, it is unlikely that higher doses of oral misoprostol (to increase efficacy) could be used for the routine prevention of PPH among healthy women although the Ghana 2006 trial used 800 mcg oral misoprostol.

Although in almost all of the trials these side‐effects were reported as not severe, they cause discomfort. For example, women in the WHO 2001 trial rated to have severe shivering needed extra blankets or other comfort measures. Amant reported that women who had shivering had their teeth chattering for 10 to 20 minutes and had no control over their body movements during this period (Amant 2001). On the other hand, in the case of pyrexia (greater than 38 °C), the staff may be concerned for the woman about the risk of postpartum infections and the need for initiating any unnecessary antibiotic treatment. Furthermore, fever may delay blood transfusion.

The largest trial (WHO 2001), used oxytocin both intramuscularly or intravenously. While it is obvious that intravenous injection provides faster availability of the drug, pharmacokinetic data show that with the intramuscular route oxytocin is circulating in the blood within two to three minutes (Gibbens 1972). Furthermore, the pharmacokinetics of oral misoprostol demonstrate that misoprostol acid reaches its peak in the plasma between 20 to 30 minutes after oral administration (Zieman 1997), well after the mean time from delivery until placental expulsion observed in the WHO 2001 (8.3 minutes, standard deviation (SD) 14.6) and Mozambique 2001 (9.0 minutes, SD 3.6) trials. Therefore, we do not think that the route of administration of oxytocin will affect its efficacy.

The nine studies which enrolled women undergoing caesarean section births have been included together with the others in the analysis. The amount of blood loss during and after caesarean section may be different, due to additional bleeding not directly related to the contractility of the uterus and, due to inevitable contamination with other fluids. However, a differential effect between different uterotonics is unlikely. Therefore, a sensitivity analysis according to the mode of delivery was not conducted. The problems associated with measurement of blood loss at caesarean section may, however, obscure any smaller differences in efficacy and push the results towards 'no difference'. In this review, these studies were analyzed within the group of studies that included women at low risk for PPH, when appropriate. Different from the prior version of the review, there are two studies (China 2003b; Turkey 2010) which included both caesarean sections and vaginal births in their study and comparison groups. It should be noted that unlike all the other studies, Turkey 2010 compared a controlled release PGE2 vaginal insert with intravenous oxytocin.

With the data available so far, there do not seem to be major differences between intramuscular prostaglandins and conventional injectable uterotonics (oxytocin or ergometrine) in reducing blood loss in the third stage of labour. These trials had few women who experienced the primary outcomes of this review, although the mean blood loss (a secondary outcome) was reduced by 22 mL to 34 mL on average for women who received intramuscular prostaglandins, based on the dose. Vomiting and diarrhoea were common side‐effects with intramuscular prostaglandins. The studies reported, however, that side‐effects did not need treatment. The concerns of safety, cost and side‐effects are important limitations of intramuscular prostaglandins.

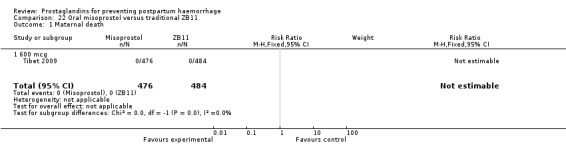

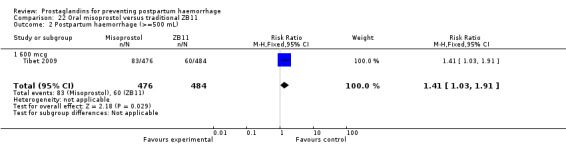

One article (Tibet 2009) compared a traditional Tibetan herbal medicine (ZB11) used for prevention of PPH with oral misoprostol and concluded that misoprostol is more effective in reducing the rates of PPH, however, there were no differences between the two groups in terms of severe PPH and mean blood loss.

Further evidence has been building around the use of oral misoprostol plus injectable uterotonics versus uterotonics. Three trials (Africa 2011; Nigeria 2011; Turkey 2003) have shown that the combination has been more effective in reducing severe PPH compared with uterotonics alone, although side‐effects like shivering and fever were more frequent with the combination. Based on the results of these studies, it is important to underline the effectiveness of a dose as low as 400 mcg versus placebo in women who received oxytocin. Given that in settings where oxytocin is available, it will reduce PPH significantly, it is not clear whether routine concurrent use should be a priority.

A WHO systematic review on the cause of maternal deaths identified obstetric haemorrhage as the largest cause of maternal death in Africa and Asia where the majority of maternal deaths occur (Khan 2006). Prevention of PPH with appropriate, evidence‐based interventions such as oxytocin and misoprostol when oxytocin is not available could prevent a substantial proportion of deaths in these two regions.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The uterotonic of choice in settings where active management is practiced is oxytocin 10 IU administered intravenously or intramuscularly. Oxytocin retains more than 85% active drug after storage for one year at under 30 °Celsius. Getting oxytocin used as widely as possible should be the primary aim for births occurring outside hospitals at peripheral levels of the healthcare system. If these conditions for oxytocin use cannot be met then misoprostol could be used based on the current evidence. The empirical dosage most used in trials to date is 600 mcg orally. Promising results against placebo have also been reported in individual trials of 400 mcg orally (over and above the routine use of oxytocin) and 600 mcg sublingually.

More efforts should be devoted to making injectable uterotonics available, especially using strategies such as that of disposable prefilled syringes, e.g. Uniject (PATH 2001; Tsu 2009). Developing the skills to administer injections in areas where this is not currently available will have the additional benefit of enabling other effective treatments such as parenteral antibiotics or anticonvulsants to be used. However, recent studies have been promising to show that oral misoprostol use has been effective and safe in community settings with low access to facilities and skilled healthcare providers. These recommendations are in line with the most recent WHO Essential Medicines List which approved misoprostol “for the prevention of PPH in settings where oxytocin is not available or cannot be safely used” (WHO 2011).

Intramuscular prostaglandins are not preferable to conventional uterotonics in the routine management of the third stage of labour especially for low‐risk women.

Implications for research.

The recent misoprostol versus placebo trials conducted outside hospitals showed promising results and future research on misoprostol use in the community should focus on implementation issues such as giving misoprostol in advance during the antenatal period to women or to traditional birth attendants for use after childbirth or other means of improving access to and safe use of uterotonics in home births. As side‐effects are dose‐related and life‐threatening hyperpyrexia has been reported with 800 mcg orally (Chong 1997), research should be directed towards establishing the lowest effective dose for routine use, and the optimal route of administration.

For the settings in which active management of the third stage is the norm, there is no need for further trials comparing misoprostol with injectable uterotonics. Future research in the third stage of labour could focus on investigating the effectiveness of the particular components of active management.

Intramuscular prostaglandins may be studied for the management of high‐risk cases since they are unlikely to find widespread use in low‐risk cases due to their costs and side‐effects.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 20 June 2011 | New search has been performed | Search updated in January 2011. Number of included studies has increased from 46 to 72 studies. We updated the search in May 2012 and have added the results to Studies awaiting classification for consideration at the next update. |

| 20 June 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Main conclusions remain unchanged. More evidence has accumulated on oral misoprostol versus placebo comparison in community‐based settings and misoprostol versus conventional oxytocics in facilities. New review author helped to prepare this update. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1997 Review first published: Issue 4, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 January 2011 | Amended | Search updated. Forty‐five new reports added to Studies awaiting classification. |

| 19 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 23 May 2007 | New search has been performed | Search updated on 28 February 2007. The current update includes 14 new trials bringing the total to 46 trials. The review now includes more evidence on misoprostol compared to placebo at non‐hospital, peripheral settings. The conclusions related to misoprostol comparison to conventional injectable uterotonics and that of intramuscular prostaglandins remain unchanged. Three papers from China are in the awaiting assessment section pending their translation. |

| 23 May 2007 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The statistics editor noticed some discrepancies in standard deviation figures of continuous data in some trials. In Switzerland 1999 the data were actually reported as standard error and this has been corrected. Continuous data from India 1988c, Nigeria 2003 and Ghana 2000 have ben excluded because they could not be reconciled by looking at the paper again. |

| 21 November 2003 | New search has been performed | The current update includes 5104 additional women from seven misoprostol trials (Canada 2002; Colombia 2002; France 2001; Nigeria 2003; Turkey 2002; Turkey 2003; United Kingdom 2003) and some excluded trials. The conclusions of the review have not changed. |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful Dr Hany Abdel‐Aleem, Dr Hazem El‐Refaey, Dr Antonio Bugalho, Dr Thomas Baskett, Dr Lars Høj and Dr Pralhad Kushtagi for providing additional data and to the referees for their comments.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods used to assess trials included in previous versions of this review

Two review authors independently evaluated trials under consideration for methodological quality and appropriateness for inclusion without consideration of their results. No language preferences were applied either during the search or selection of trials. Two authors independently extracted data regardless of whether they participated in a particular included trial or not.

We assessed methodological quality in terms of adequacy of allocation concealment as described in Higgins 2005.

In addition to the main outcomes, we systematically extracted the following data for each study:

trial entry criteria (high versus low risk, other specific exclusion criteria);

exclusions and missing data after randomization;

management of the third stage of labour;

the duration and technique of assessment of blood loss.

We evaluated statistical heterogeneity across trial results using the chi‐square test as calculated in MetaView. Whenever statistical (P < 0.1) or visual heterogeneity was encountered, we explored the possible reasons. In meta‐analyses with significant heterogeneity (statistical or visual), we discuss the trials individually (i.e. without totals).

It is not clear how components of third stage management, other than the uterotonic, affect the blood loss. While the comparison of the uterotonic might be valid, if other components of active management are effective, then the scope for any difference between a prostaglandin and a placebo or another uterotonic could be minimized if those components are used.

These factors are assessed as possible sources of heterogeneity where appropriate and if there are adequate numbers of studies to allow such assessments.

Because of the significant differences in pharmacokinetics and possibly other properties, we analysed oral, rectal, sublingual and buccal misoprostol and intramuscular prostaglandins (PGF2alpha and synthetic E2) separately.

We did not exclude trials on the basis of a predetermined cut‐off value for loss to follow‐ups and postrandomization exclusions. We systematically extracted this information and discussed as appropriate for each trial.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Maternal death | 3 | 3965 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.24, 8.81] |

| 1.1 600 mcg | 3 | 3965 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.24, 8.81] |

| 2 Maternal death or severe morbidity | 2 | 2848 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.36, 3.80] |

| 2.1 600 mcg | 2 | 2848 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.36, 3.80] |

| 3 Severe postpartum haemorrhage (>= 1000 ml) | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 600 mcg | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 400 mcg | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Postpartum haemorrhage (>= 500 ml) | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 600 mcg | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 400 mcg | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Blood loss (ml) | 5 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 600 mcg | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 400 mcg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Use of additional uterotonics | 5 | 3585 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.70, 1.08] |

| 6.1 600 mcg | 4 | 2685 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.66, 1.13] |

| 6.2 400 mcg | 2 | 900 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.61, 1.26] |

| 7 Blood transfusion | 4 | 3519 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.10, 0.94] |

| 7.1 600 mcg | 3 | 2619 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.06, 0.94] |

| 7.2 400 mcg | 2 | 900 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.6 [0.08, 4.52] |

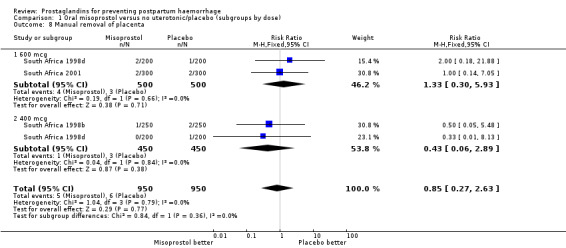

| 8 Manual removal of placenta | 3 | 1900 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.27, 2.63] |

| 8.1 600 mcg | 2 | 1000 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.30, 5.93] |

| 8.2 400 mcg | 2 | 900 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.06, 2.89] |

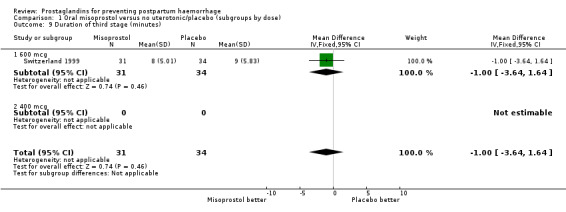

| 9 Duration of third stage (minutes) | 1 | 65 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.0 [‐3.64, 1.64] |

| 9.1 600 mcg | 1 | 65 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.0 [‐3.64, 1.64] |

| 9.2 400 mcg | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

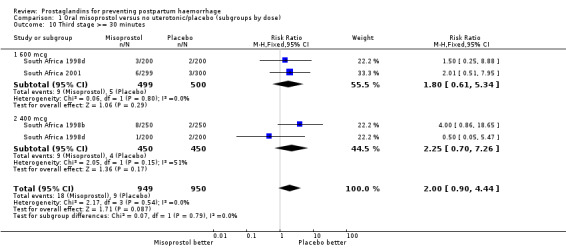

| 10 Third stage >= 30 minutes | 3 | 1899 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.00 [0.90, 4.44] |

| 10.1 600 mcg | 2 | 999 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.80 [0.61, 5.34] |

| 10.2 400 mcg | 2 | 900 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.25 [0.70, 7.26] |

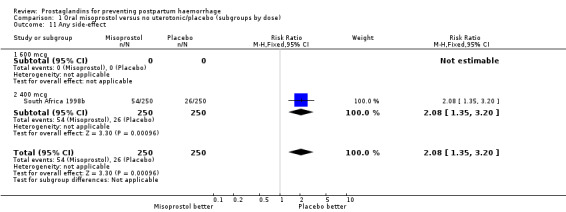

| 11 Any side‐effect | 1 | 500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.08 [1.35, 3.20] |

| 11.1 600 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.2 400 mcg | 1 | 500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.08 [1.35, 3.20] |

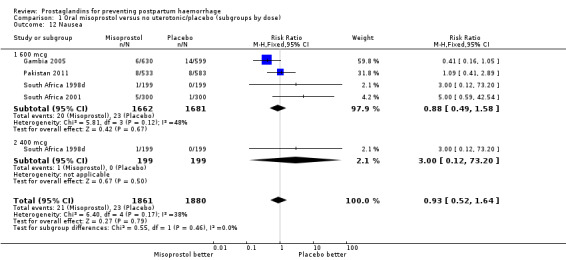

| 12 Nausea | 4 | 3741 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.52, 1.64] |

| 12.1 600 mcg | 4 | 3343 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.49, 1.58] |

| 12.2 400 mcg | 1 | 398 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.12, 73.20] |

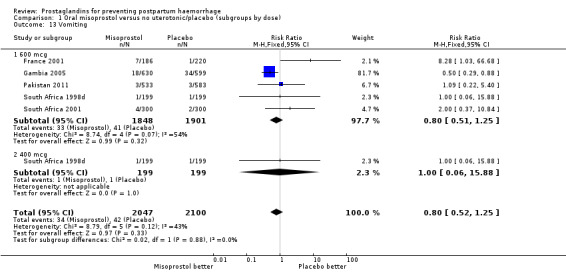

| 13 Vomiting | 5 | 4147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.52, 1.25] |

| 13.1 600 mcg | 5 | 3749 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.51, 1.25] |

| 13.2 400 mcg | 1 | 398 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.06, 15.88] |

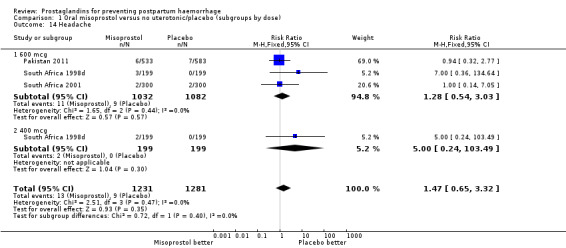

| 14 Headache | 3 | 2512 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.47 [0.65, 3.32] |

| 14.1 600 mcg | 3 | 2114 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.54, 3.03] |

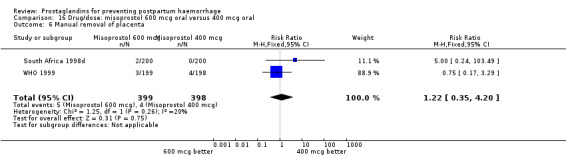

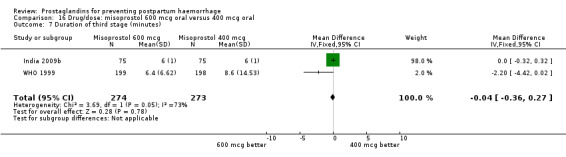

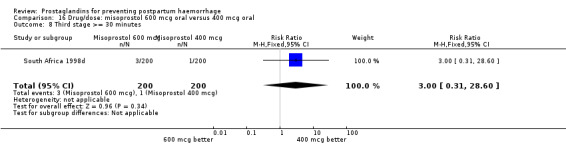

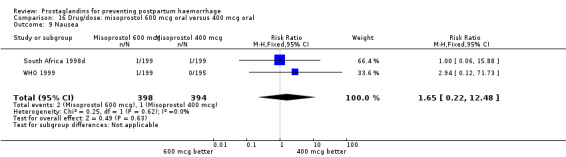

| 14.2 400 mcg | 1 | 398 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.24, 103.49] |

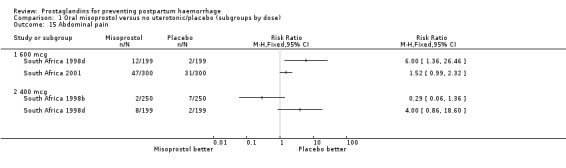

| 15 Abdominal pain | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 15.1 600 mcg | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 15.2 400 mcg | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

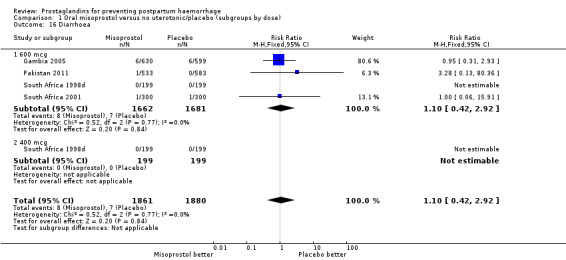

| 16 Diarrhoea | 4 | 3741 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.42, 2.92] |

| 16.1 600 mcg | 4 | 3343 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.42, 2.92] |

| 16.2 400 mcg | 1 | 398 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17 Any shivering | 8 | 6332 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.96 [2.66, 3.31] |

| 17.1 600 mcg | 7 | 5434 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.01 [2.68, 3.39] |

| 17.2 400 mcg | 2 | 898 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.63 [1.90, 3.63] |

| 18 Pyrexia (>= 38 degrees C) | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 18.1 600 mcg | 5 | 4140 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.39 [3.78, 7.69] |

| 18.2 400 mcg | 1 | 400 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.6 [2.21, 14.21] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 1 Maternal death.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 2 Maternal death or severe morbidity.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 3 Severe postpartum haemorrhage (>= 1000 ml).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 4 Postpartum haemorrhage (>= 500 ml).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 5 Blood loss (ml).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 6 Use of additional uterotonics.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 7 Blood transfusion.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 8 Manual removal of placenta.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 9 Duration of third stage (minutes).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 10 Third stage >= 30 minutes.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 11 Any side‐effect.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 12 Nausea.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 13 Vomiting.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 14 Headache.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 15 Abdominal pain.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 16 Diarrhoea.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 17 Any shivering.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 18 Pyrexia (>= 38 degrees C).

Comparison 2. Rectal misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Severe postpartum haemorrhage (>= 1000 mL) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 600 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.2 400 mcg | 1 | 542 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.35, 1.37] |

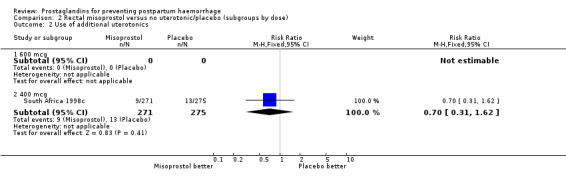

| 2 Use of additional uterotonics | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 600 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 400 mcg | 1 | 546 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.31, 1.62] |

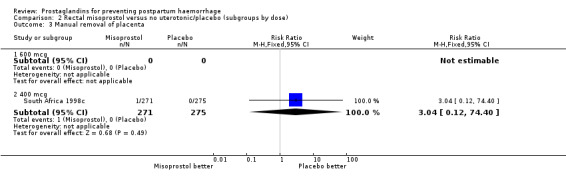

| 3 Manual removal of placenta | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 600 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.2 400 mcg | 1 | 546 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.04 [0.12, 74.40] |

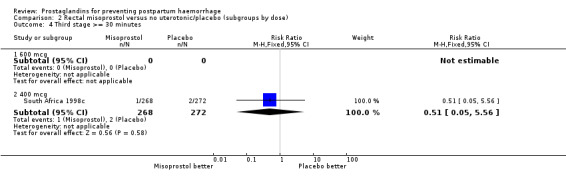

| 4 Third stage >= 30 minutes | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 600 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.2 400 mcg | 1 | 540 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.05, 5.56] |

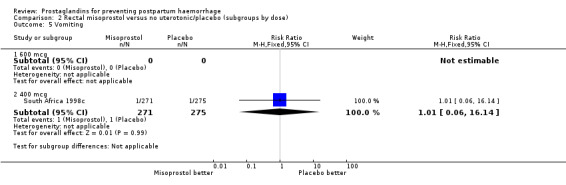

| 5 Vomiting | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 600 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.2 400 mcg | 1 | 546 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.06, 16.14] |

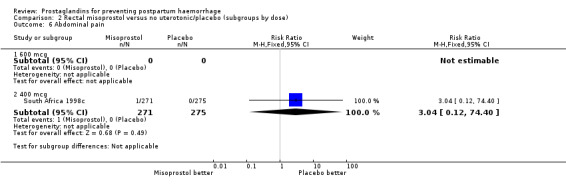

| 6 Abdominal pain | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 600 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.2 400 mcg | 1 | 546 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.04 [0.12, 74.40] |

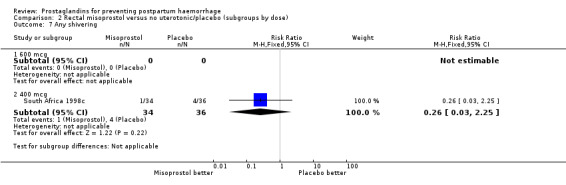

| 7 Any shivering | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 600 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.2 400 mcg | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.26 [0.03, 2.25] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Rectal misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 1 Severe postpartum haemorrhage (>= 1000 mL).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Rectal misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 2 Use of additional uterotonics.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Rectal misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 3 Manual removal of placenta.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Rectal misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 4 Third stage >= 30 minutes.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Rectal misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 5 Vomiting.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Rectal misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 6 Abdominal pain.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Rectal misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 7 Any shivering.

Comparison 3. Sublingual misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

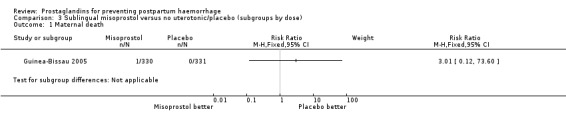

| 1 Maternal death | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 Severe postpartum haemorrhage (>= 1000 mL) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 600 mcg | 1 | 661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.45, 0.98] |

| 2.2 400 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

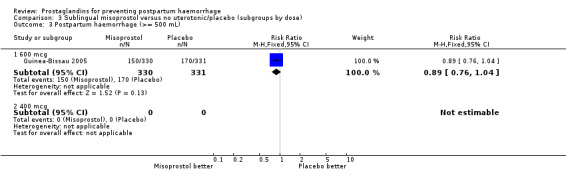

| 3 Postpartum haemorrhage (>= 500 mL) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 600 mcg | 1 | 661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.76, 1.04] |

| 3.2 400 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

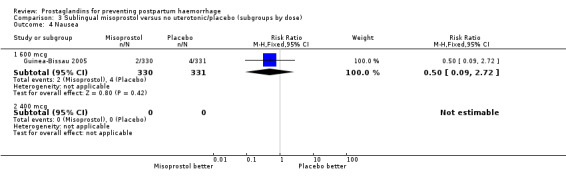

| 4 Nausea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 600 mcg | 1 | 661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.09, 2.72] |

| 4.2 400 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

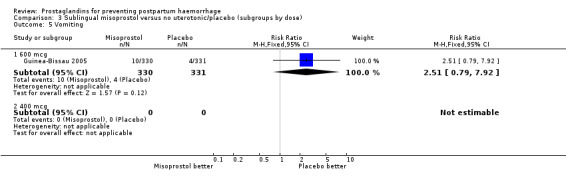

| 5 Vomiting | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 600 mcg | 1 | 661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.51 [0.79, 7.92] |

| 5.2 400 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

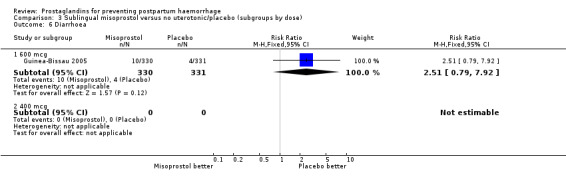

| 6 Diarrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 600 mcg | 1 | 661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.51 [0.79, 7.92] |

| 6.2 400 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

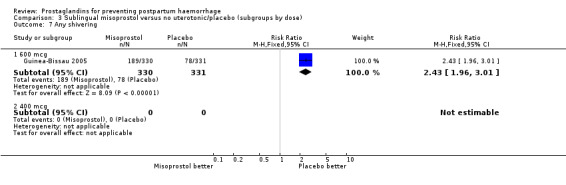

| 7 Any shivering | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 600 mcg | 1 | 661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.43 [1.96, 3.01] |

| 7.2 400 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

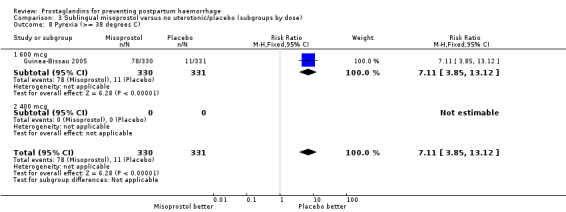

| 8 Pyrexia (>= 38 degrees C) | 1 | 661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.11 [3.85, 13.12] |

| 8.1 600 mcg | 1 | 661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.11 [3.85, 13.12] |

| 8.2 400 mcg | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Sublingual misoprostol versus no uterotonic/placebo (subgroups by dose), Outcome 1 Maternal death.

3.2. Analysis.