Abstract

Background

The effect of low dose corticosteroids, equivalent to 15 mg prednisolone daily or less, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis has been questioned. We reviewed the trials that compared corticosteroids with placebo or non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs.

Objectives

To determine whether short‐term (i.e. as recorded within the first month of therapy), oral low‐dose corticosteroids (corresponding to a maximum of 15 mg prednisolone daily) is superior to placebo and non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Search methods

PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, reference lists and a personal archive. Date of last search Nov 2007.

Selection criteria

All randomised trials comparing an oral corticosteroid (not exceeding an equivalent of 15 mg prednisolone daily) with placebo or a non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drug were eligible if they reported clinical outcomes within one month after start of therapy. For adverse effects, long‐term trials were also selected.

Data collection and analysis

Decisions on which trials to include were made independently by two observers based on the methods sections of the trials. Standardised mean difference (random effects model) was used for the statistical analyses.

Main results

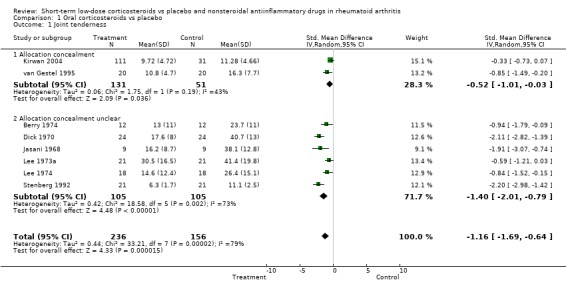

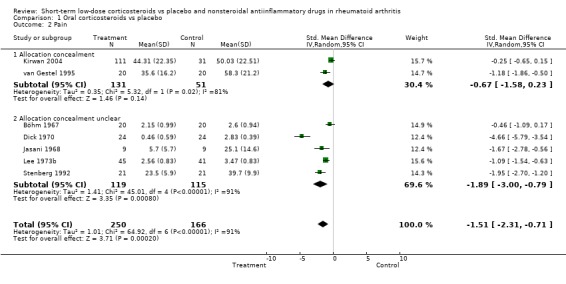

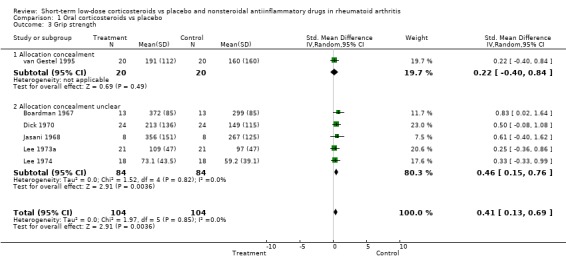

Eleven trials, involving 462 patients, were included. Two placebo‐controlled trials had adequate allocation concealment. For joint tenderness, the standardised mean difference was ‐0.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.01 to ‐0.03, for pain it was ‐0.67, 95% CI ‐1.58 to 0.23, and for grip strength, 0.22, 95% CI ‐0.40 to 0.84. The estimates for the other trials were considerably larger.

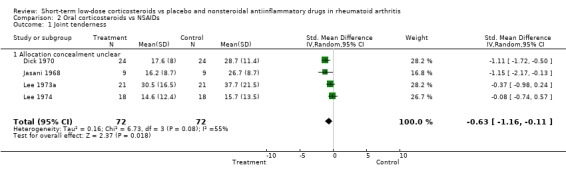

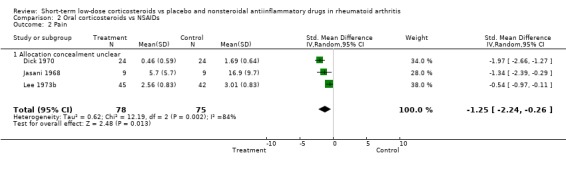

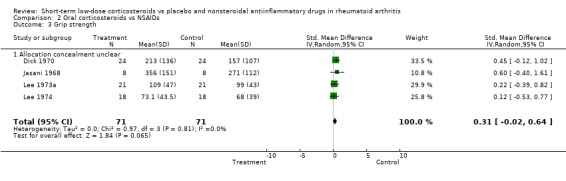

Prednisolone also had a greater effect than non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs on joint tenderness (‐0.63, 95% CI ‐1.16 to ‐0.11) and pain (‐1.25, 95% CI ‐2.24 to ‐0.26), whereas the difference in grip strength was not significant (0.31, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.64). The main harms in long‐term treatment were vertebral fractures and infections.

Authors' conclusions

Prednisolone in low doses (not exceeding 15 mg daily) may be used intermittently in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, particularly if the disease cannot be controlled by other means. The risk of harms needs to be considered, however, especially the risk of fractures and infections. Since prednisolone is highly effective, short‐term placebo controlled trials studying the clinical effect of low‐dose prednisolone or other oral corticosteroids are no longer necessary.

Plain language summary

Corticosteroids versus placebo and NSAIDs for rheumatoid arthritis

Short‐term low‐dose corticosteroids compared with placebo and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

Corticosteroid drugs can relieve inflammation, and in high doses they have a dramatic effect on the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. They are used only temporarily, however, because of serious adverse effects during long‐term use. The review found that corticosteroids in low doses are very effective. They are more effective than usual anti‐arthritis medications (non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs). The risk of harms needs to be considered, however, especially the risk of fractures and infections.

Background

Corticosteroids were first shown to be effective in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in an uncontrolled study (Hench 1949). In 1959, a two‐year randomised trial showed that an initial dose of prednisolone 20 mg daily was significantly superior to aspirin 6 g daily (Joint Committee 1959). Important harms were also noted, however, and the authors concluded that the highest acceptable dose for long‐term therapy is probably in the region of 10 mg daily.

Corticosteroids have received renewed interest in recent years because of their possible beneficial effect on radiological progression (Weiss 1989). Tendencies towards such an effect have been noted both in the early trials and in a more recent report (Kirwan 1995) and will be examined in a Cochrane review (Kirwan 2007).

These findings are interesting, but oral corticosteroids are still being used mainly in high doses for their symptomatic effect, for example for acute exacerbations of rheumatoid arthritis and as "bridge therapy", before slow‐acting drugs have taken effect (Harris 1983). The effect of low doses has been variable, and was questioned as late as in 1995 when the most recent trial of low‐dose steroids was published (van Gestel 1995). We performed a systematic review of randomised trials which compared corticosteroids, given at a dose equivalent to no more than 15 mg prednisolone daily, with placebo or with non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs. Our review is limited to the short‐term effect, i.e. as recorded within the first month of therapy. However, in an analysis of the harms of steroids we also included long‐term trials.

Objectives

To compare the short‐term beneficial and harmful effects, i.e. as recorded within the first month of therapy, of oral low‐dose corticosteroids with that of placebo and non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

To compare the harms in long‐term trials of oral low‐dose corticosteroids with that of placebo and non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised trials comparing an oral corticosteroid with placebo or a non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drug in patients with rheumatoid arthritis were eligible if they reported clinical outcomes within one month after start of therapy. When there were data from several visits, the data which came closest to one week of therapy was used for the analyses. We excluded studies with high‐dose steroids (exceeding an equivalent of 15 mg prednisolone daily); studies of combination therapies, for instance of a steroid and a non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drug, and studies using quasi‐randomisation methods, such as allocation by date of admission or by toss of a coin (no such studies were found).

To study the harms in more detail, we also identified moderate‐ and long‐term randomised trials, which had compared low‐dose steroids with placebo or a non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drug.

Types of participants

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis, in all but one study defined by the criteria of the American Rheumatism Association (Arnett 1988) (the criteria have changed slightly over the years).

Types of interventions

Experimental: oral low‐dose corticosteroids (not exceeding an equivalent of 15 mg prednisolone daily). Control: placebo or oral non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs.

Types of outcome measures

Joint tenderness (usually Ritchie's joint index), pain, grip strength.

Search methods for identification of studies

PubMed was searched from 1966 to November 2007: "Arthritis, Rheumatoid"[mh] AND placebo AND "Glucocorticoids"[Pharmacological Action]. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials was searched in November 2007: (glucocorticoids explode all trees (MeSH) and (Arthritis, Rheumatoid explode all trees (MeSH)) and placebo. The reference lists were scanned for additional trials and an archive in possession of one of the authors was scanned. Since most of the retrieved trials were very old and the steroid drugs were non‐proprietary ones, authors and companies were not asked about possible unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Decisions on which trials to include were taken independently by two observers based on the methods sections of the trials; disagreements were resolved by discussion. Details on the nature and dosage of treatments, number of randomised patients, the randomisation and blinding procedures, and exclusions after randomisation were noted. Since the outcomes were measured on different scales, even when they referred to the same quality, e.g. tender joints, we calculated the standardised mean difference. With this method, the difference in effect between two treatments is divided by the standard deviation of the measurements. By that transformation, the effect measures become dimension‐less and outcomes from trials which have used different scales may therefore often be combined. As an example, the tender joint count may be recorded either as the number of tender joints or as Ritchie's index in which each joint is scored on a scale from zero to three for pain on firm palpation, and the scores are added. If the patients have very severe disease, Ritchie's index may be higher, but the standard deviation will then also be higher, and by dividing the counts with their standard deviations, the effect sizes will be of the same magnitude.

The random effects model was used since there was substantial heterogeneity. As the trials were all small, this would not be expected to lead to overestimation of treatment effects. Since data from crossover trials were only reported in summary form, as if they had been generated from a group comparative trial, we analysed them accordingly. We therefore assumed that no important carry‐over effects had occurred.

Results

Description of studies

Thirty‐five randomised trials were initially identified, several of which had been published more than once. Twenty‐four trials were excluded for various reasons. Eleven trials did not fulfil the inclusion criteria for the meta‐analysis: one was not randomised although so labelled in PubMed (Hantzschel 1976), five had studied combination drugs (Badia Flores 1969; Gum 1966; Jick 1965; Siegmeth 1974; Zuckner 1969), three used too high dose (Hansen 1999; Joint Committee 1954; Joint Committee 1959), in one, 4 mg methylprednisolone was given to all the patients in the placebo group (Slonim 1969), and one concerned patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (Kvien 1982) (this trial found prednisolone to be significantly better than placebo). The other 15 excluded studies were potentially eligible for the review. However, one was a five‐way crossover trial (Deodhar 1973) with a grossly unbalanced design; for instance, placebo was given to 9, 13, 3, 6, and 6 patients during weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. Because of the regression towards the mean effect, we found it inappropriate to include this trial. Another trial was also unbalanced, since the steroid group was kept mobile whereas the control group received bed rest and splints for the inflamed joints (Million 1984). Two trials were too poorly reported to be usable (Fearnley 1966; Murthy 1978), and one only reported on joint size (Webb 1973). Three of these trials found prednisolone or prednisone to be significantly more effective than placebo, and one compared prednisolone and indomethacin and gave no numerical data but just reported that there was "no significant difference in response" (Murthy 1978). The eight other excluded trials were long‐term studies that did not report short‐term data as well (Capell 2004; Chamberlain 1976; Empire Rheum 1955; van Everdingen 2002; Harris 1983; Kirwan 1995; Leszczynski 2000; Rau 2000). Eleven trials, involving 462 patients, were included in the review. Most of the trials were quite old and rather small. In all but one (Böhm 1967), the criteria of the American Rheumatism Association for classical or definite rheumatoid arthritis (Arnett 1988) were fulfilled. Age, proportion of females and disease duration were only reported in about half of the trials but they were typical for studies in rheumatoid arthritis. As would be expected for patients becoming enrolled in steroid trials, the severity of the disease, expressed as number of tender joints or Ritchie's tender joint index, was quite pronounced (see graphs). Prednisolone was used in seven trials and prednisone in four. Since prednisone is equipotent with prednisolone and is a pro‐drug to prednisolone, we will refer to "prednisolone" as a general term in the following. The doses were 2.5‐7.5 mg in four studies, 10 mg in three studies, and 15 mg in four. Data were available after one week for all studies but two for which two‐week and four‐week data (as two‐week data were difficult to read on the graphs (Kirwan 2004)) were used, respectively.

Risk of bias in included studies

The randomisation method was only described in one of the trial reports (Kirwan 2004) but details were obtained from the authors of another study (van Gestel 1995); the treatment allocation appeared to have been adequately concealed in these two studies. All studies were double‐blind apart from a single‐blind study in which the patients appeared to have been blinded (Lee 1973b). Eight of the studies were of a crossover design but only one of them reported to have tested for sequence effects (Stenberg 1992). Apart from one study (Stenberg 1992), the tender joint count was recorded as Ritchie's index; pain was recorded on a ranking scale with 4 or 5 classes in two studies (Böhm 1967; Lee 1973b), on a visual analogue scale in three studies (Berry 1974; Kirwan 2004; van Gestel 1995), and as a composite pain index in two studies (Jasani 1968; Stenberg 1992).

Effects of interventions

Eleven trials, involving 462 patients were included. The results are shown in the graphs. It should be noted that if prednisolone is better than control, the standardised mean difference is negative for joint tenderness and pain, but positive for grip strength. There was large heterogeneity in the effects, and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Two placebo‐controlled trials had adequate allocation concealment. For joint tenderness, the standardised mean difference was ‐0.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.01 to ‐0.03, for pain it was ‐0.67, 95% CI ‐1.58 to 0.23, and for grip strength, 0.22, ‐95% CI 0.40 to 0.84. The estimates for the other trials were considerably larger.

Prednisolone also had a greater effect than non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs on joint tenderness (‐0.63, 95% CI ‐1.16 to ‐0.11) and pain (‐1.25, 95% CI ‐2.24 to ‐0.26), whereas the difference in grip strength was not significant (0.31, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.64).

The harms were poorly described. Five of the eleven studies we included for efficacy analyses did not report any data on harms; one study reported that no side effects occurred (Jasani 1968); two patients on prednisone had "subjective reactions" in one study (Boardman 1967); and one patient developed acute psychosis while on prednisone in one study (Lee 1973b). The three remaining studies were moderate‐term studies from which we extracted short‐term efficacy data (Kirwan 2004; Stenberg 1992; van Gestel 1995) and moderate‐ term adverse effects.

We found 12 moderate‐ and long‐term randomised trials which had compared low‐dose steroids with placebo or a non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drug (Table 3). Because of differences in evaluation of harms and in reporting them, we did not try to pool these data. In five of the trials (203 vs 202 patients), where X‐ray had been used to detect vertebral fractures, nine fractures on corticosteroids and four on placebo were reported. The incidence of infections was also increased with corticosteroids (for other reported harms, see Table 3).

1. Harms in moderate‐ and long‐term studies.

| Study | Drugs | Length of study | Number of patients | Harms |

| Capell 2004 | Prednisolone 7 mg, placebo | 2 years | 84 vs 83 | Withdrawals: 6 (3 weight gain, facial swelling, nausea, gastrointesinal bleeding) vs 2 (nausea, diarrhoea); Fractures: none reported; No difference in bone mineral content, blood pressure or weight. |

| Chamberlain 1976 | Prednisolone 3 and 5 mg, placebo | 2 years | 20 vs 10 vs 19 | Withdrawals: none because of harms; Vertebral fractures: 1 vs 0 vs 1; Moon face (difficult to decide): 5 vs 2 vs 1; Mild dyspepsia: 3 vs 4 vs 4. |

| Empire Rheum 1955 | Cortisone 75 mg, Aspirin 4 g | 3 years | 50 vs 50 | Withdrawals: 3 (2 hypertension, indigestion) vs 5(gastrointestinal symptoms); Fractures: 1 (after a fall) vs 0; Oedema: 4 vs 0; Gastrointestinal symptoms: 4 vs 17; Mild psychiatric disturbance: 4 vs 0; Infection: 10 vs 4. (These are 1‐year data) |

| Harris 1983 | Prednisone 5 mg, placebo | 2 years | 18 vs 16 | Withdrawals: none reported; Vertebral fractures detected with X‐ray: 2 vs 0; Ocular changes: none. |

| Joint Committee 1954 | Cortisone 80 mg, Aspirin 4.5 g | 1 year | 30 vs 31 | Withdrawals: none because of harms; Fractures: none reported; Most common harms on steroid: 11 moon face or rubicundity, 5 depression, 4 euphoria; on Aspirin: 13 gastrointestinal symptoms, 11 tinnitus, 10 deafness. |

| Joint Committee 1959 | Prednisolone 17.4 mg, NSAIDs | 2 years | 45 vs 39 | Withdrawals: none because of harms; Vertebral fractures detected with X‐ray: 2 vs 1; Acute phychosis: 2 vs 0; Peptic ulcer: 3 vs 0; Major infection: 4 vs 3. |

| Kirwan 1995 | Prednisolone 7.5 mg, placebo | 2 years | 61 vs 67 | Withdrawals: 1 vs 2 hypertension and weight gain, 0 vs 1 diabetes; Fractures: none reported; Other harms: only listed, not divided on treatment groups. |

| Kirwan 2004 | Budesonide 3 and 9 mg, prednisolone 7.5 mg, placebo | 12 weeks | 37, 36, 39, 31 | Withdrawals: no data, only symptoms listed; Serious harms: budesonide 3 mg (1 angina), prednisolone (1 with ischaemic heart diesase died); Fractures: none reported; Respiratory infection: 7 vs 4 vs 6 vs 1; Viral infection: 4 vs 1 vs 0 vs 0. Abdominal pain: 4 vs 3 vs 4 vs 2. |

| Rau 2000 | Prednisolone 5 mg, placebo | 2 years | 80 vs 86 | Withdrawals: none; Vertebral fractures detected with X‐ray: none; Other fractures: 1 (pubic ramus) vs 0 (plus 4 caused by trauma, not divided on treatment groups); Cushing: 5 vs 0; Hypertension: 6 vs 2; Weight gain: 5 kg vs 0.3 kg; Cataract: 5 vs 6; Gastric ulcers: 3 vs 0. Headache: 4 vs 0. |

| Stenberg 1992 | Prednisolone 3 mg, placebo | 3 months | 18 (crossover) | Withdrawals: none reported; Fractures: none reported; Weight gain: 3 vs 2; Hypertension: 1 vs 3; Gastrointestinal symptoms: 2 vs 2; Insomnia: 1 vs 0. |

| van Everdingen 2002 | Prednisolone 10 mg, placebo | 2 years | 40 vs 41 | Withdrawals: none because of harms; Vertebral fractures detected with X‐ray: 5 vs 2; Respiratory infections: 13 vs 13; Diabetes: 2 vs 1; Peptic ulcer: 1 vs 2; Depression: 1 vs 2. |

| van Gestel 1995 | Prednisolone 10 mg (tapered to 2.5 mg), placebo | 44 weeks | 20 vs 20 | Withdrawals: none reported; Vertebral fractures detected with X‐ray: none; Other harms: none reported. |

Discussion

Low‐dose prednisolone is not only highly effective for short‐term therapy, but also significantly more effective than non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs. A systematic review of the effect of low‐dose prednisolone after six months also found a significantly better effect of drug than of placebo (Criswell 1998).

The point estimate for the difference in effect between prednisolone and non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs on grip strength was 12 mm Hg, which is the same as the point estimate for the difference in effect between non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs and placebo (Gøtzsche 1989b). It is not surprising that the difference in grip strength between prednisolone and non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs was not statistically significant, since this effect measure is considerably less sensitive to drug effects than pain and joint tenderness (Gøtzsche 1990a).

There was substantial heterogeneity between the trials. Our attempts to explain its causes have been rather unsuccessful. Since most of the studies were performed decades ago, earlier trials could have overestimated the effect, for instance because of insufficiently concealed randomisation methods (Schulz 1995). However, the methodological quality of the trials was rather similar in the whole time span of 40 years and it was also similar to the quality of comparative drug trials of non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory (Gøtzsche 1989a). In accordance with this, there were no time trends for the differences in joint tenderness and pain between prednisolone and placebo (see graphs). Blinding did not seem to have been important for the heterogeneity. Only one trial was not double‐blind and this trial did not yield larger effect estimates than the other trials.

Small trials may exaggerate the effect because of publication bias (Dickersin 1993; Stern 1997) and other biases. The trials were all rather small, but the effect was so pronounced that it would have been unreasonable to plan large, confirmatory trials. In this respect , steroid trials resemble trials of non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs which have been shown to be effective in small crossover trials against placebo (Gøtzsche 1990a).

A possible cause for the heterogeneity could be varying degrees of concomitant therapy. Although sometimes prohibited in trial protocols, it may be difficult to ensure that patients do not take additional drugs. Since there was very sparse information on drug intake in the reports, this possibility could not be evaluated.

Another source of heterogeneity could be the use of different measurement scales. Pain, for example, was measured on three different types of scales. They were all ranking scales, and we would therefore have preferred to analyse pain with rank sum tests, or as binary data after reduction of the level of measurement. Since the original authors had used parametric statistics, we decided to do so as well, rather than discard the data.

There was no clear relation between dose and effect despite the fact that the doses varied from 2.5 mg to 15 mg daily. It was not the aim of our review, however, to study dose‐response relationships which are elucidated more reliably in studies where patients are randomised to different doses. A remarkable effect was seen in a study in which the average dose was only 3 mg daily but where the patients were allowed to start on 7.5 mg when they experienced flares of the arthritis and were advised to take nothing when they were well (Stenberg 1992). This study suggests that it could be an advantage to take steroids intermittently which would also diminish their harms.

It could be discussed whether we were too liberal by including crossover trials for which we assumed that no important carryover effects had occurred. We believe our approach is justified since one would not expect carryover problems for drugs with relatively quick and reversible symptomatic effects such as steroids or non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In fact, in a meta‐analysis of non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs, very similar results were obtained with the two trial designs (Gøtzsche 1989b). Only three studies were of a group comparative design, and the heterogeneity we found could not be explained by type of design.

The titles of the included trials were generally quite uninformative and some of them would not have been too easy to find since they were performed within experiments designed to study other factors. Several of the studies were retrieved from an archive in possession of one of the authors, assembled during work on a thesis (Gøtzsche 1990b), before the electronic data searches were performed. The authors of a long‐term study (van Gestel 1995) had only found one of five trials comparing steroids with placebo in long‐term studies, and none of the nine short‐term trials included in our review. These short‐term trials were described in eleven reports which were all indexed in PubMed with the term for rheumatoid arthritis; in addition, all but one (Jasani 1968) contained the terms for clinical trial or comparative study. Further, all nine trials were identifiable by using the search term placebo* and (prednisone or prednisolone). This illustrates the value of a systematic and careful search of the literature before starting new clinical trials. To diminish the risk of unnecessary research, funding bodies and ethical review committees should demand a systematic review of the relevant literature before approving of new clinical research (Savulescu 1996).

We found two studies of matched cohorts that described the harms of corticosteroids (McDougall 1994; Saag 1994). One of the matched cohort studies had included 112 patients who had received 15 mg prednisolone or less for at least 12 months and 112 matched controls (Saag 1994). It used a survival type analysis and found a large difference in time to first adverse event, with a total of 92 events in the steroid group and 31 in the untreated group. The risk of fracture increased with increasing doses: odds ratio 32.3 (95% confidence interval 4.6 to 220) for >10‐15 mg prednisolone daily, 4.5 (95% CI 2.1 to 9.6) for 5‐10 mg, and 1.9 (95% CI 0.8 to 4.7) for less than 5 mg daily. The overall risks for first event were: fracture 3.9 (95% CI 0.8 to 18.1), infection 8.0 (95% CI 1.0 to 64.0), gastrointestinal bleed or ulcer 3.3 (95% CI 0.9 to 12.1). This study also included patients who received oral steroid "pulses", which do not necessarily lead to the same incidence and severity of adverse effects as continuous low‐dose treatment. The other cohort study followed two groups of 122 patients for 10 years (McDougall 1994). Fractures were noted in 31 vs 19 patients, osteonecrosis in 5 vs 2, and cataracts in 36 vs 22.

The main problem with such studies are that the two groups can never be completely comparable, since patients treated with steroids must be expected to be more severely affected than those not treated. This fact may escape notice by traditional measures of morbidity, or the difference may be statistically significantly for one (McDougall 1994) or more (Saag 1994) indicators of disease severity, as in the two cohort studies we reviewed. It is noteworthy, for example, that the first study (Saag 1994) found a similarly increased risk for fractures as for ulcers, since five meta‐analyses of around one hundred randomised trials of steroids in a variety of diseases have shown either no increase in risk, or, at most, a marginally increased risk of ulcers, which lacks clinical significance (Gøtzsche 1994). Another meta‐analysis of 71 randomised trials, which looked at the risk of infectious complications, showed no increase in risk in patients given less than 10 mg prednisolone daily, and the relative risk for a mean dose less than 20 mg was only 1.3 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.6) (Stuck 1989), which is in contrast to the 8‐fold increased risk in the cohort study (Saag 1994). Although the confidence intervals were wide in the cohort study, this illustrates the well‐known dangers of non‐randomised comparisons.

All treatments for rheumatoid arthritis, including non‐steroidal, anti‐inflammatory drugs and slow‐acting antirheumatic drugs, may cause important harms that may occasionally be life‐threatening. We therefore suggest that short‐term prednisolone in low doses, i.e. not exceeding 15 mg daily, may be used intermittently in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, particularly if they have flares in their disease which cannot be controlled by other means. This suggestion is in accordance with detailed reviews of the harms of low‐dose steroids (Caldwell 1991; Da Silva 2006). Since prednisolone is highly effective, short‐term placebo controlled trials studying the clinical effect of low‐dose prednisolone or other oral corticosteroids are no longer necessary.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Prednisolone in low doses (not exceeding 15 mg daily) may be used intermittently in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, particularly if the disease cannot be controlled by other means. The risk of harms needs to be considered, however, especially the risk of fractures and infections.

Implications for research.

Since prednisolone is highly effective, short‐term placebo controlled trials studying the clinical effect of low‐dose prednisolone or other oral corticosteroids are no longer necessary.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. CMSD ID: C076‐R |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the unpublished data provided by Anke van Gestel and Roland Laan.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Oral corticosteroids vs placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Joint tenderness | 8 | 392 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.16 [‐1.69, ‐0.64] |

| 1.1 Allocation concealment | 2 | 182 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.52 [‐1.01, ‐0.03] |

| 1.2 Allocation concealment unclear | 6 | 210 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.40 [‐2.01, ‐0.79] |

| 2 Pain | 7 | 416 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.51 [‐2.31, ‐0.71] |

| 2.1 Allocation concealment | 2 | 182 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.67 [‐1.58, 0.23] |

| 2.2 Allocation concealment unclear | 5 | 234 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.89 [‐1.00, ‐0.79] |

| 3 Grip strength | 6 | 208 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.13, 0.69] |

| 3.1 Allocation concealment | 1 | 40 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.22 [‐0.40, 0.84] |

| 3.2 Allocation concealment unclear | 5 | 168 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.15, 0.76] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral corticosteroids vs placebo, Outcome 1 Joint tenderness.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral corticosteroids vs placebo, Outcome 2 Pain.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral corticosteroids vs placebo, Outcome 3 Grip strength.

Comparison 2. Oral corticosteroids vs NSAIDs.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Joint tenderness | 4 | 144 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.63 [‐1.16, ‐0.11] |

| 1.1 Allocation concealment unclear | 4 | 144 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.63 [‐1.16, ‐0.11] |

| 2 Pain | 3 | 153 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.25 [‐2.24, ‐0.26] |

| 2.1 Allocation concealment unclear | 3 | 153 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.25 [‐2.24, ‐0.26] |

| 3 Grip strength | 4 | 142 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.31 [‐0.02, 0.64] |

| 3.1 Allocation concealment unclear | 4 | 142 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.31 [‐0.02, 0.64] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral corticosteroids vs NSAIDs, Outcome 1 Joint tenderness.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral corticosteroids vs NSAIDs, Outcome 2 Pain.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oral corticosteroids vs NSAIDs, Outcome 3 Grip strength.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Berry 1974.

| Methods | Crossover study; one‐week periods, and one‐week wash‐out. Randomisation not mentioned; only that the study was double‐blind. | |

| Participants | 12 patients with definite or classical rheumatoid arthritis (ARA criteria). | |

| Interventions | Prednisolone 15 mg/d, placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Pain (visual analogue scale) Duration of morning stiffness Ritchie's index Joint size Paracetamol consumption Technetium index Indium index Patient preference | |

| Notes | No test for carry‐over and period effects. No data on side effects. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Boardman 1967.

| Methods | Crossover study; one‐week periods. Sequential analysis of joint size. Randomisation not mentioned; only that the study was double‐blind. | |

| Participants | 13 patients with definite or classical rheumatoid arthritis (ARA criteria). | |

| Interventions | Prednisone 7.5 mg/d, placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Joint size Grip strength Patient preference | |

| Notes | No test for carry‐over and period effects. We included two patients, who the authors had excluded because of too little difference in joint size, in the analysis by assuming that their grip strength difference was zero. Grip strength data were missing for another patient. Two patients on prednisone had 'subjective reactions'. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Böhm 1967.

| Methods | Four‐way crossover study; eight‐day periods. Randomisation method not described. Double‐blind. | |

| Participants | 20 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. | |

| Interventions | Prednisolone 2.5 mg, two combination drugs, placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Pain (4 point ranking scale) | |

| Notes | No test for carry‐over and period effects. No data on side effects. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dick 1970.

| Methods | Four‐way crossover study; one‐week periods. Randomisation method not described. Double‐blind. | |

| Participants | 24 patients with definite or classical rheumatoid arthritis (ARA criteria). | |

| Interventions | Prednisolone 10 mg/d, ibuprofen 1200 mg/d, aspirin 4 g/d, placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Global evaluation Knee tenderness score Ritchie's index Grip strength Joint size | |

| Notes | No test for carry‐over and period effects. Average of ibuprofen and aspirin used in the analysis. No data on side effects. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Jasani 1968.

| Methods | Four‐way crossover study; one‐week periods. Randomisation method not described. Double‐blind. | |

| Participants | 9 patients with definite or classical rheumatoid arthritis (ARA criteria). | |

| Interventions | Prednisolone 15 mg/d, ibuprofen 750 mg/d, aspirin 5 g/d, placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Joint pain Joint stiffness Pain index (composite scale) Ritchie's index Grip strength Joint size | |

| Notes | No test for carry‐over and period effects. Average of ibuprofen and aspirin used in the analysis. No side effects occurred with prednisolone or placebo. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Kirwan 2004.

| Methods | Group comparative study; 12 weeks, data after 2 weeks available. Randomisation method: "Predefined sequence of randomly generated allocations kept in sealed envelopes", "Patients allocated to next available study number". Double‐blind: "double‐dummy". | |

| Participants | 143 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (ARA criteria). | |

| Interventions | Budesonide 3 and 9 mg, 7.5 mg prednisolone, placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Tender joint count Pain Global assessments Physical function (HAQ) SF‐36 | |

| Notes | Data after 2 weeks from author; SDs estimated from graphs after 4 weeks. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Lee 1973a.

| Methods | Three‐way crossover study; one‐week periods. Randomisation method not described. Double‐blind. | |

| Participants | 21 patients with definite or classical rheumatoid arthritis (ARA criteria). | |

| Interventions | Prednisolone 15 mg/d, aspirin 5 g/d, placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Functional index Ritchie's index Time to walk 50 feet Grip strength | |

| Notes | No test for carry‐over and period effects. No data on side effects. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lee 1973b.

| Methods | Group comparative study of three drugs; two weeks. Randomisation method not described. Single‐blind; probably the patient was blinded. | |

| Participants | 141 patients with rheumatoid arthritis according to ARA criteria. | |

| Interventions | Prednisone 15 mg/d, aspirin 3.9 g/d, placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Global evaluation Pain (5 point ranking scale) Number of days withdrawn from trial | |

| Notes | Thirteen patients were excluded after randomisation (failed to complete the trial), three on prednisolone, five on aspirin, and five on placebo. One patient developed acute psychosis on prednisone. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lee 1974.

| Methods | Three‐way crossover study; one‐week periods. Randomisation method not described. Double‐blind. | |

| Participants | 18 patients with definite or classical rheumatoid arthritis (ARA criteria). | |

| Interventions | Prednisolone 10 mg/d, sodium salicylate 4 g/d, placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Functional index Ritchie's index Grip strength | |

| Notes | No test for carry‐over and period effects. No data on side effects. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Stenberg 1992.

| Methods | Crossover study; each flare treated for five days. Randomisation not described; only that the study was double‐blind, half of the patients starting on each drug. | |

| Participants | 22 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (ARA criteria). | |

| Interventions | Prednisone (average dose 3 mg/d), placebo. Prednisone was only taken during flares: 7.5 mg day 1, 5 mg next 3 days, and 2.5 mg day 5. | |

| Outcomes | Tender joint count Swollen joint count Pain (composite score) Global assessment Morning stiffness Painful joint count Time until fatigue Medication usage | |

| Notes | Tested for carry‐over effects. Three randomised patients were excluded because of poor response to prednisone in an introductory test period. We included these patients in the analysis by assuming that the differences between prednisone and placebo were zero. One additional patient dropped out for personal reasons. No data on short‐term side effects since multiple flares were treated during a three months period. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

van Gestel 1995.

| Methods | Group comparative study; 44 weeks, data after one week provided by authors. Randomisation method: list of random numbers; a pharmacist coded the packages. Double‐blind. | |

| Participants | 40 patients with definite or classical rheumatoid arthritis (ARA criteria); all started parenteral gold. | |

| Interventions | Prednisone 10 mg/d, placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Joint pain (visual analogue scale) Global evaluation Morning stiffness Ritchie's index Number of swollen joints Grip strength Functional capacity X‐ray progression | |

| Notes | Grip strength recalculated as mm Hg from kPa. Long‐term study, no data on short‐term side effects. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Badia Flores 1969 | Combination drug (prednisolone 2.5 mg + oxiphenbutazone 100 mg) vs placebo. |

| Capell 2004 | Long‐term study with assessment after 1 and 2 years (7 mg prednisolone vs placebo, 167 patients). |

| Chamberlain 1976 | Long‐term study with assessment after 1, 2, and 3 years (3 and 5 mg prednisolone vs placebo, 49 patients). |

| Deodhar 1973 | Unbalanced design (five‐way crossover trial comparing prednisolone 10 mg with placebo and three NSAIDs). |

| Empire Rheum 1955 | Long‐term study with assessment after 6 and 12 months (75 mg cortisone vs aspirin 4 g, 100 patients). |

| Fearnley 1966 | No data on dispersion (prednisone 7.5 mg vs flufenamic acid 600 mg). |

| Gum 1966 | Only 50 of 68 patients had rheumatoid arthritis; combination drug (paramethasone 1.5 g + aspirin 3 g + propoxyphene 192 mg vs aspirin 3 g + propoxyphene 192 mg). |

| Hansen 1999 | Dose of prednisolone too high, 30 mg daily in first week. |

| Hantzschel 1976 | Not a randomised trial. |

| Harris 1983 | Long‐term study with assessment after 12 and 24 weeks (prednisone 5 mg vs placebo, 34 patients). |

| Jick 1965 | Combination drug (dexamethasone 1.5 mg vs dexamethasone 0.75 mg + aspirin 1.5 g). |

| Joint Committee 1954 | Cortisone dose too high (300‐100 mg in the first week, average dose corresponding to 16 mg prednisolone, comparison with aspirin 6 g, 62 patients). |

| Joint Committee 1959 | Prednisolone dose 20 mg initially with an average of 17.4 mg after 4 weeks. Long‐term study vs aspirin or other analgesics, 84 patients. |

| Kirwan 1995 | Long‐term study with no short‐term data. |

| Kvien 1982 | Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (prednisolone 0.4 mg/kg vs placebo). |

| Leszczynski 2000 | Concerns osteoporosis, no clinical outcomes. |

| Million 1984 | Randomised to activity + steroid and to rest; therefore, not valid for testing the effect of steroid versus no steroid. Further, the dose was up to 20 mg prednisolone. |

| Murthy 1978 | No data presented on the original interval scales, only data on reduced (trinomial) scales shown. |

| Rau 2000 | Concerns radiological progression, no clinical data. |

| Siegmeth 1974 | Combination drug (prednisolone 2.5 mg + oxiphenbutazone 100 mg vs flufenamic acid 200 mg). |

| Slonim 1969 | Stepwise increasing dose of methylprednisolone up to 16 mg but placebo group received 4 mg methylprednisolone daily. |

| van Everdingen 2002 | Long‐term study with assessments every 3 months (10 mg prednisolone vs placebo, 81 patients with early disease). |

| Webb 1973 | Only joint size recorded (prednisolone 7.5 mg vs aspirin 4.8 g vs placebo). |

| Zuckner 1969 | Describes an unpublished crossover trial of 20 patients; combination therapy, steroid + analgesics versus analgesics. |

Contributions of authors

PCG wrote the draft protocol and manuscript. HKJ commented on the drafts. Both authors contributed to selection of studies and extraction of data. PCG is guarantor for the study

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Medical Research Council, Denmark.

Declarations of interest

None.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Berry 1974 {published data only}

- Berry H, Huskisson EC. Isotopic indices as a measure of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1974;33:523‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boardman 1967 {published data only}

- Boardman PL, Dudley Hart F. Clinical measurement of the anti‐inflammatory effects of salicylates in rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ 1967;4:264‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Böhm 1967 {published data only}

- Böhm C. Zur medikamentösen Langzeittherapie der primär chronischen Polyarthritis. Med Welt 1967;35:2047‐50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoger GA. Zur beurteilung der Wirkung einer Kombination von Salicylaten und Prednisolon bei rheumatischen Erkrankungen. Arzneimittel‐Forschung 1968;18:758‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dick 1970 {published data only}

- Dick WC, Nuki G, Whaley K, Deodhar S, Buchanan WW. Some aspects in the quantitation of inflammation in joints of patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Phys Med 1970;suppl 10:40‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jasani 1968 {published data only}

- Jasani MK, Downie WW, Samuels BM, Buchanan WW. Ibuprofen in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1968;27:457‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kirwan 2004 {published data only}

- Kirwan JR, Hallgren R, Mielants H, Wollheim F, Bjorck E, Persson T, et al. A randomised placebo controlled 12 week trial of budesonide and prednisolone in rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of Rheumatic Diseases 2004;63(6):688‐95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan JR, Hickey SH, Hallgren R, Mielants H, Bjorck E, Persson T, et al. The effect of therapeutic glucocorticoids on the adrenal response in a randomized controlled trial in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54(5):1415‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 1973a {published data only}

- Lee P, Jasani MK, Dick WC, uchanan W. Evaluation of a functional index in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 1973;2:71‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 1973b {published data only}

- Lee P, Anderson JA, Miller J, Webb J, Buchanan WW. Evaluation of analgesic action and efficacy of antirheumatic drugs. J Rheumatol 1976;3:283‐94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P, Webb J, Anderson J, Buchanan WW. Method for assessing therapeutic potential of anti‐inflammatory antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ 1973;2:685‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 1974 {published data only}

- Lee P, Baxter A, Carson Dick W, Webb J. An assessment of grip strength measurement in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 1974;3:17‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stenberg 1992 {published data only}

- Stenberg VI, Fiechtner JJ, Rice JR, Miller DR, Johnson LK. Endocrine control of inflammation: rheumatoid arthritis. Double‐blind, crossover clinical trial. Int J Clin Pharm Res 1992;12:11‐18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

van Gestel 1995 {published and unpublished data}

- Gestel AM van, Laan RFJM, Haagsma CJ, Putte LBA van de, Riel PLCM van. Oral steroids as bridge therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients starting with parenteral gold. A randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial. Br J Rheumatol 1995;34:347‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laan RFJM, Riel PLCM van, Putte LBA van de, Erning LJTO van, Hof MA van't, Lemmens JAM. Low‐dose prednisone induces rapid reversible axial bone loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:963‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Badia Flores 1969 {published data only}

- Badia Flores J. Valoracion del GP‐40705 en la artritis reumatoide. Prensa Med Mex 1969;34,9:382‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Capell 2004 {published data only}

- Capell HA, Madhok R, Hunter JA, Porter D, Morrison E, Larkin J, et al. Lack of radiological and clinical benefit over two years of low dose prednisolone for rheumatoid arthritis: results of a randomised controlled trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2004;63(7):797‐803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chamberlain 1976 {published data only}

- Chamberlain MA, Keenan J. The effect of low doses of prednisolone compared with placebo on function and on the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Rehabil 1976;15:17‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deodhar 1973 {published data only}

- Deodhar SD, Dick WC, Hodgkinson R, Buchanan WW. Measurement of clinical response to anti‐inflammatory drug therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Quarterly J Med 1973;166:387‐401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Empire Rheum 1955 {published data only}

- Empire Rheumatism Council. Multi‐centre controlled trial comparing cortisone acetate and acetyl salicylic acid in the long‐term treatment of rheumaoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1955;14:353‐63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Empire Rheumatism Council. Multi‐centre controlled trial comparing cortisone acetate and acetyl salicylic acid in the long‐term treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1957;16:277‐89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fearnley 1966 {published data only}

- Fearnley ME, Masheter HC. A controlled trial of flufenamic acid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Phys Med 1966;8:204‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnly ME. An investigation of possible synergism between flufenamic acid and prednisone. Ann Phys Med 1966;suppl:109‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gum 1966 {published data only}

- Gum OB. A controlled study of two preparations, paramethasone, propoxyphene, and aspirin and propoxyphene and aspirin in the treatment of arthritis. Am J Med Sci 1966;251:328‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hansen 1999 {published data only}

- Hansen M, Podenphant J, Florescu A, Stoltenberg M, Borch A, Kluger E, et al. A randomised trial of differentiated prednisolone treatment in active rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical benefits and skeletal side effects. Ann Rheum Dis 1999;58(11):713‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hantzschel 1976 {published data only}

- Hantzschel H, Otto W, Astapenko MG, Tautenhahn B, Trofimowa TM, Fischer H, et al. [Results of different long term treatments of patients in the early stages of rheumatoid arthritis]. Z Gesamte Inn Med 1976;31:934‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Harris 1983 {published data only}

- Harris ED, Emkey RD, Nicols JE, Newberg A. Low dose prednisone therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a double blind study. J Rheumatol 1983;10:713‐21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jick 1965 {published data only}

- Jick H, Pinals RS, Ullian R, Slone D, Muench H. Dexamethasone and dexamethasone‐aspirin in the treatment of chronic rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 1965;2:1203‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jick H, Slone D, Dinan B, Muench H. Evaluation of drug efficacy by a preference technic. N Engl J Med 1966;275:1399‐1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Joint Committee 1954 {published data only}

- Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation. A comparison of cortisone and aspirin in the treatment of early cases of rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ 1954;1:1223‐7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation. A comparison of cortisone and aspirin in the treatment of early cases of rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ 1955;2:695‐700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation. Long‐term results in early cases of rheumatoid arthritis treated with either cortisone or aspirin. BMJ 1957;1:847‐50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Joint Committee 1959 {published data only}

- Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation. A comparison of prednisolone with aspirin or other analgesics in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1959;18:173‐88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Committee of the Medical Research Council and Nuffield Foundation. Comparison of prednisolone with aspirin or other analgesics in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1960;19:331‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West HF. Reumatoid arthritis. The relevance of clinical knowledge to research activities. Abstracts World Med 1967;41:401‐17. [Google Scholar]

Kirwan 1995 {published data only}

- Haugeberg G, Strand A, Kvien TK, Kirwan JR. Reduced loss of hand bone density with prednisolone in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from a randomized placebo‐controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine 2005;165(11):1293‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickling P, Jacoby RK, Kirwan JR. Joint destruction after glucocorticoids are withdrawn in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism Council Low Dose Glucocorticoid Study Group. Br J Rheumatol 1998;37:930‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan JR and the Arthritis and Rheumatism Council Low‐dose Glucocorticoid Study Group. The effect of glucocorticoids on joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 1995;333:142‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kvien 1982 {published data only}

- Kvien TK, Hoyeraal HM, Sandstad B. Assessment methods of disease activity in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis ‐ evaluated in a prednisolone/placebo double‐blind study. J Rheumatol 1982;9:696‐702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leszczynski 2000 {published data only}

- Leszczynski P, Lacki J K, Mackiewicz S H. Osteoporoza posteroidowa u chorych na reumatoidalne zapalenie stawow. Przegl Lek 2000;57(2):108‐10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Million 1984 {published data only}

- Million R, Kellgren JH, Poole P, Jayson MIV. Long‐term study of management of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 1984;i:812‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West HF. Reumatoid arthritis. The relevance of clinical knowledge to research activities. Abstracts World Med 1967;41:401‐17. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckner J, Uddin J, Ramsey RH. Adrenal‐pituitary relationships with porlonged low dosage steroid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Missouri Med 1969;66:649‐58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Murthy 1978 {published data only}

- Murthy MHV, Rhymer AR, Wright V. Indomethacin or prednisolone at night in rheumatoid arthritis?. Rheumatol Rehab 1978;17:8‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rau 2000 {published data only}

- Rau R, Wassenberg S, Zeidler H. Low dose prednisolone therapy (LDPT) retards radiographically detectable destruction in early rheumatoid arthritis ‐ preliminary results of a multicenter, randomized, parallel, double blind study. Z Rheumatol 2000;59 Suppl 2:II/90‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassenberg S, Rau R, Steinfeld P, Zeidler H. Very low‐dose prednisolone in early rheumatoid arthritis retards radiographic progression over two years: a multicenter, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52(11):3371‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Siegmeth 1974 {published data only}

- Siegmeth W, Herkner W. Erfahrungen mit einem neuen Kombinationspräparat (Realin) bei der Behandlung akuter rheumatischer Zustandsbilder. Wien Med Wochenschr 1974;124:569‐73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Slonim 1969 {published data only}

- Slonim RR, Kiem IM, Howell DS, Brown HE. Evaluation of drug responses in the patient severely afflicted with rheumatoid arthritis. J Florida Med Assoc 1969;56,5:336‐41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

van Everdingen 2002 {published data only}

- Huisman AM, Siewertsz van Everdingen AA, Wenting MJ, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor up‐regulation in early rheumatoid arthritis treated with low dose prednisone or placebo. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2003;21(2):217‐20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everdingen AA, Jacobs JW G, Siewertsz Van Reesema DR, Bijlsma JW J. Low‐dose prednisone therapy for patients with early active rheumatoid arthritis: clinical efficacy, disease‐modifying properties, and side effects: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 2002;136(1):1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everdingen AA, Siewertsz van Reesema DR, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW. Low‐dose glucocorticoids in early rheumatoid arthritis: discordant effects on bone mineral density and fractures?. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2003;21(2):155‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everdingen AA, Siewertsz van Reesema DR, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW. The clinical effect of glucocorticoids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis may be masked by decreased use of additional therapies. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51(2):233‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Webb 1973 {published data only}

- Webb J, Downie WW, Dick WC, Lee P. Evaluation of digital joint circumference measurements in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 1973;2:127‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zuckner 1969 {published data only}

- Zuckner J, Uddin J, Ramsey RH. Adrenal‐pituitary relationships with porlonged low dosage steroid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Missouri Med 1969;66:649‐58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Arnett 1988

- Arnett FC, Edsworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The 1987 revised American Rheumatism Association criteria for classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 1988;31:315‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Caldwell 1991

- Caldwell JR, Furst DE. The efficacy and safety of low‐dose corticosteroids for rheumatoid arthritis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 1991;21:1‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Criswell 1998

- Criswell LA, Saag KG, Sems KM, Welch V, Shea B, Wells G, Suarez‐Almazor ME. Moderate‐term, low‐dose corticosteroids for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1998, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001158] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Da Silva 2006

- Silva JA, Jacobs JW, Kirwan JR, Boers M, Saag KG, et al. Safety of low dose glucocorticoid treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: published evidence and prospective trial data. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2006;65(3):285‐93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dickersin 1993

- Dickersin K, Min Y‐I. NIH clinical trials and publication bias. Online J Curr Clin Trials 1993 Apr 28;Doc No 50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gøtzsche 1989a

- Gøtzsche PC. Methodology and overt and hidden bias in reports of 196 double‐blind trials of nonsteroidal, antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Controlled Clinical Trials 1989;10:31‐56 (erratum: 356). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gøtzsche 1989b

- Gøtzsche PC. Meta‐analysis of grip strength: most common, but superfluous variable in comparative NSAID trials. Danish Medical Bulletin 1989;36:493‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gøtzsche 1990a

- Gøtzsche PC. Sensitivity of effect variables in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta‐analysis of 130 placebo controlled NSAID trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1990;43:1313‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gøtzsche 1990b

- Gøtzsche PC. Bias in double‐blind trials (thesis). Danish Medical Bulletin 1990;37:329‐36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gøtzsche 1994

- Gøtzsche PC. Steroids and peptic ulcer: an end to the controversy? (editorial). Journal of Internal Medicine 1994;236:599‐601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hench 1949

- Hench PS, Kendall EC, Slocumb CH, Polley HF. The effect of a hormone of the adrenal cortex (17‐hydroxy‐11‐dehydrocorticosterone: compound E) and of pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone on rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin 1949;24:181‐97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kirwan 2007

- Kirwan JR, Bijlsma JWJ, Boers M, Shea B. Effects of glucocorticoids on radiological progression in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006356] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McDougall 1994

- McDougall R, Sibley J, Haga M, Russell A. Outcome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving prednisone compared to matched controls. Journal of Rheumatology 1994;21:1207‐13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saag 1994

- Saag KG, Koehnke R, Caldwell JR, Brasington R, Burmeister LF, Zimmerman B, et al. Low dose long‐term corticosteroid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: an analysis of serious adverse events. American Journal of Medicine 1994;96:115‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Savulescu 1996

- Savulescu J, Chalmers I, Blunt J. Are research ethics committees behaving unethically? Some suggestions for improving performance and accountability. BMJ 1996;313:1390‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schulz 1995

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman D. Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273:408‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stern 1997

- Stern JM, Simes RJ. Publication bias: evidence of delayed publication in a cohort study of clinical research projects. BMJ 1997;315:640‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stuck 1989

- Stuck AE, Minder CE, Frey FJ. Risk of infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticosteroids. Reviews of Infectious Diseases 1989;11:954‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weiss 1989

- Weiss MM. Corticosteroids in rheumatoid arthritis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 1989;19:9‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Gøtzsche 1998

- Gøtzsche PC, Johansen HK. Meta‐analysis of short‐term low‐dose prednisolone vs placebo and nonsteroidal, antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ 1998;316:811‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gøtzsche 2001

- Gøtzsche PC, Johansen HK. Short‐term low‐dose corticosteroids vs placebo and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000189.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]