Abstract

Background

Surgical site infection and other hospital‐acquired infections cause significant morbidity after internal fixation of fractures. The administration of antibiotics may reduce the frequency of infections.

Objectives

To determine whether the prophylactic administration of antibiotics in people undergoing surgical management of hip or other closed long bone fractures reduces the incidence of surgical site and other hospital‐acquired infections.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group Specialised Register (December 2009), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2009, Issue 4), MEDLINE (1950 to November 2009), EMBASE (1988 to December 2009), other electronic databases including the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (December 2009), conferences proceedings and reference lists of articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials comparing any regimen of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis administered at the time of surgery, compared with no prophylaxis, placebo, or a regimen of different duration, in people with a hip fracture undergoing surgery for internal fixation or prosthetic replacement, or with any closed long bone fracture undergoing internal fixation. All trials needed to report surgical site infection.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened papers for inclusion, assessed risk of bias and extracted data. Pooled data are presented graphically.

Main results

Data from 8447 participants in 23 studies were included in the analyses. In people undergoing surgery for closed fracture fixation, single dose antibiotic prophylaxis significantly reduced deep surgical site infection (risk ratio 0.40, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.67), superficial surgical site infections, urinary infections, and respiratory tract infections. Multiple dose prophylaxis had an effect of similar size on deep surgical site infection (risk ratio 0.35, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.62), but significant effects on urinary and respiratory infections were not confirmed. Although the risk of bias in many studies as reported was unclear, sensitivity analysis showed that removal from the meta‐analyses of studies at high risk of bias did not alter the conclusions. Economic modelling using data from one large trial indicated that single dose prophylaxis with ceftriaxone is a cost‐effective intervention. Data for the incidence of adverse effects were very limited, but as expected they appeared to be more common in those receiving antibiotics, compared with placebo or no prophylaxis.

Authors' conclusions

Antibiotic prophylaxis should be offered to those undergoing surgery for closed fracture fixation.

Keywords: Humans; Antibiotic Prophylaxis; Orthopedic Procedures; Arthroplasty; Femoral Fractures; Femoral Fractures/surgery; Fracture Fixation, Internal; Fractures, Closed; Fractures, Closed/surgery; Hip Fractures; Hip Fractures/surgery; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Surgical Wound Infection; Surgical Wound Infection/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Antibiotic prophylaxis for surgery for proximal femoral and other closed long bone fractures

Infection of bone and soft tissues can result after bone fractures. Fractures which penetrate the skin are called 'open' or 'compound'. If the skin remains intact despite the fracture, it is called 'simple' or 'closed'. If a closed fracture is treated by a surgical operation, bacteria can contaminate the wound, and cause surgical site infection. This, and other hospital‐acquired infections, can be life threatening in people following surgery for thigh and other closed long bone fractures. Antibiotics have been given routinely since the 1970s in an effort to reduce infections from bacteria such as staphylococcus. This review included 23 trials, involving a total of 8447 participants. The review found that antibiotics are effective in reducing the incidence of infection, both at the surgical‐wound site and in the chest and urinary tract. The effect of a single dose of antibiotic is similar to that from multiple doses if the antibiotic chosen is active through the period from the beginning of surgery until the wound is sealed. There were too few data available to confirm the expected tendency for increased adverse drug‐related events such as gut problems and skin reactions.

Background

The principles of prophylaxis against post‐surgical infection were established in laboratory studies in the early 1960s (Burke 1961). The administration of antibiotic prior to surgery is now widely accepted. The period of administration of prophylaxis has been reduced but the optimal duration remains uncertain. Antibiotic prophylaxis during the operative management of closed fractures has been claimed to reduce infection rates from around five per cent to less than one per cent (Bodoky 1993). As the pathogenesis of post‐surgical infection is similar after osteosynthesis of any closed fracture, it has been suggested that combining data from similar prophylactic regimens used during different surgical procedures is quite appropriate (Platt 1991).

Closed hip fractures in the elderly are common, and surgical management is normal in the developed world. The majority of studies of the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in closed fracture fixation have focused on this group of people. Early randomised trials completed in the 1970s suggested a small but definite prophylactic effect. These trials were individually small, and some used prolonged courses of antibiotic. Many further trials have been reported since then. These have addressed a range of issues: duration of administration, route of administration, and antimicrobial spectrum.

Before the production of the first version of this review (published 1998), a number of descriptive reviews of antibiotic prophylaxis in orthopaedic surgery were available (Doyon 1989; Norden 1991), in which some attempt had been made to assess methodological quality and include this in the interpretation of results. However, there was sufficient persisting uncertainty about the efficacy, optimal duration, and cost‐effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis during the surgical treatment of hip and other long bone fractures to justify a systematic review of the evidence from randomised trials. This update continues the systematic review of the evidence.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to determine whether the prophylactic administration of antibiotics in people undergoing surgical management of hip or other closed long bone fractures reduces the incidence of surgical site and other hospital‐acquired infections.

The following hypotheses are tested:

1. Antibiotic prophylaxis leads to a reduction in the proportion of people developing a surgical site infection, either deep or superficial, compared with those given a placebo or no prophylaxis.

2. 'Single dose' antibiotic prophylaxis leads to a significant reduction in the proportion of people developing a surgical site infection compared with those given 'longer duration' prophylaxis.

3. Antibiotic prophylaxis leads to a significant reduction in the proportion of people developing septicaemia, respiratory or urinary tract infection, compared with those given a placebo or no prophylaxis.

4. 'Single dose' antibiotic prophylaxis leads to a significant reduction in the proportion of people developing septicaemia, respiratory, or urinary tract infection after surgical management of a hip or other long bone fracture compared with those given three or more doses.

5. Oral administration of a prophylactic regimen leads to a significant reduction in the proportion of people experiencing a surgical site infection, respiratory or urinary tract infection, or adverse drug effect, compared with those receiving parenteral prophylaxis.

6. There is a significant increase in the proportion of people with conditions such as gastro‐intestinal symptoms or skin reactions in those allocated antibiotic prophylaxis when compared with those receiving placebo or no prophylaxis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

The predetermined inclusion criteria were broad so as to include any controlled study testing a prophylactic antibiotic in closed fracture surgery.

1. The study must test some method of antibiotic prophylactic intervention aimed at reducing the surgical site infection rate in closed fracture surgery and compare it against a placebo or alternative intervention group.

2. The study must be a controlled study, either randomised or quasi‐randomised.

3. The study population must be defined to enable identification of the operative intervention, ideally with relevant subgroups given if more than one. Studies which included participants undergoing various orthopaedic procedures were included only if disaggregated data were available for the participants undergoing closed fracture surgery.

4. Surgical site infection must be one of the primary outcome measures.

Types of participants

Any person undergoing surgery for internal fixation or replacement arthroplasty as treatment for a closed fracture of the proximal femur, or any other long bone.

Types of interventions

Any regimen of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis administered at the time of surgery. Comparisons between antibiotic agents were included only if their purpose was to compare single dose prophylaxis or day of surgery prophylaxis against a longer multiple dose regimen.

Types of outcome measures

1. Surgical site infection. The reference definition of surgical site infection for quality assessment was: Deep surgical site infection: A surgical wound infection which occurs within one year, if an implant is in place and infection involves tissues or spaces at or beneath the fascial layer. Superficial surgical site infection: A surgical wound infection which occurs at the incision site within 30 days after surgery and involves the skin subcutaneous tissue, or muscle located above the fascial layer. 2. Urinary tract infection 3. Respiratory tract infection 4. Adverse reaction to antibiotic (gastro‐intestinal symptoms, skin reactions) 5. Cost‐effectiveness outcomes (length of hospital stay, reoperation due to infection).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group Specialised Register (December 2009), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2009, Issue 4), MEDLINE (1950 to November 2009), EMBASE (1988 to December 2009), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970 to December 2009), and LILACS (1982 to December 2009).

In MEDLINE (Ovid) subject‐specific search terms were combined with the sensitivity‐maximising version of the MEDLINE trial search strategy (Lefebvre 2009), The strategy was modified for use in The Cochrane Library (Wiley InterScience), EMBASE (Ovid), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (Ovid) and LILACS. Search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

We also searched proceedings of meetings of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (1980 to 2001), the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (1990 to 2001), and the Societe Internationale de Chirurgie Orthopedique (1980 to 2001).

We searched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (December 2009) to identify any ongoing or recently completed trials.

No language restrictions were applied.

Searching other resources

We also checked reference lists of articles and contacted published researchers in the field.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The full reports of identified studies were assessed independently by the two review authors to ascertain if these met the review inclusion criteria. Differences were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Data were independently extracted by both authors using a data extraction tool which had undergone prior testing. Differences were resolved by discussion. We approached three groups of trialists for clarification of data relevant to the review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Methodological assessment was undertaken in the original review by the two authors, using the criteria described in Appendix 2, supplemented by a pre‐designed coding manual. Disagreement was resolved by discussion between raters. With further reference to original study reports where necessary, and using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009), risk of bias assessments were completed for all included studies. The risk categories assessed were adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, and incomplete outcome data. As loss to follow up was not an item in the assessment criteria in Appendix 2, we allocated 'low risk' for incomplete outcome data to studies which reported their losses in each group and an appropriate sensitivity analysis, high risk to those with losses of 5% or more without a sensitivity analysis, and unclear in those with losses less than 5% or which did not report losses.

Measures of treatment effect

We used risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for dichotomous outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

For studies with multiple intervention groups, we ensured that unit of analysis issues arising from inclusion of any participants more than once in a meta‐analysis were avoided.

Dealing with missing data

Using Microsoft Excel, we calculated what the effect of missing data might have been on the number of deep infections in each group of each included study.

If the total number of people randomised but not the distribution between participant groups was given, but the number analysed and the losses were available for each group, the number randomised to each group was calculated.

If the total number of losses but not the distribution by groups was known, we explored three assumptions: that the losses were evenly distributed (using nearest integer) between groups; that two thirds of the losses were in the experimental group; and that two thirds of the losses were in the control group.

We assumed that the risk of events amongst lost treatment group participants was that present amongst known control group participants in that study, and that the risk amongst lost control group participants was that present amongst known treatment group participants. In this way, we imputed a reasonable, but conservative estimate of the number of lost participants in each group sustaining a deep infection.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between pooled trials was assessed using a combination of visual inspection of the graphs, consideration of the Chi2 test, and the I2 statistic.

Data synthesis

For comparable groups of trials, pooled risk ratios with 95 per cent confidence intervals were derived using the fixed‐effect model. Where there was substantial statistical heterogeneity we planned to pool the data, if appropriate, using the random‐effects model. Where appropriate, absolute risk reduction was calculated. For the main outcome of interest, deep surgical site infection, the data were presented by subgroups to investigate any possible heterogeneity associated with participant context. In the main analysis, we used for each included study the data on number of participants and number of events in each group provided in the study report, and explored the implications of missing data by imputation and sensitivity analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

For this update we conducted, as well as the exploration of the implications of missing data described above, a sensitivity analysis to explore how robust the conclusions of our review remain when the risk of bias in the included studies was taken into account. Studies assessed at high risk of bias in two or more of the four risk categories, or at high risk of bias in one category and uncertain status in the other three categories, were removed from the main analysis in order to determine the effect on statistical and clinical significance.

Results

Description of studies

The search strategy for this update identified one additional candidate study in LILACS, which after translation from Portuguese was excluded (Da Silva 1987). Included in two systematic reviews, published since the last update of this review, were three studies that did not meet our inclusion criteria (Ali 2006; Garotta 1991; Liebergall 1995) and one study (Lindberg 1978) which did meet our inclusion criteria but had not been identified in our previous searches. Thus, since the review was first published, 54 completed trials have been identified that might have met the inclusion criteria.

We found two ongoing studies (ISRCTN75423827; NCT00610987) that are likely to be eligible for inclusion in this review when data become available.

Thirty‐one of the completed studies (seeCharacteristics of excluded studies) were excluded because either the participants had sustained an open fracture prior to the administration of antibiotics, or participants had not sustained a fracture, or no usable data were reported for participants undergoing internal fixation of closed fractures. The remaining 23 studies were included and are described in detail in the Characteristics of included studies. One study (Buckley 1990) contributed data to three comparisons. All included studies contributed data to the analyses of surgical site infection. Data on incidence of urinary tract infection were reported in nine studies, and of respiratory infection in seven studies.

The comparisons evaluated were:

1. A pre‐operative dose and two or more post‐operative doses of parenteral (injected) antibiotic compared with a placebo or with no treatment. Data from 10 studies were included in this category, in seven of which the participants underwent hip fracture surgery (Bodoky 1993; Boyd 1973; Buckley 1990; Burnett 1980; Ericson 1973; Lindberg 1978; Tengve 1978), and in three of which (Bergman 1982; Gatell 1984; Paiement 1994) other closed fracture fixation procedures were carried out. Three studies (Bergman 1982; Boyd 1973; Ericson 1973) evaluated the effect of narrow spectrum beta‐lactamase sensitive or penicillinase‐resistant penicillins; the remainder evaluated first or second generation cephalosporins.

2. A single preoperative dose of parenteral antibiotic compared with a placebo or no treatment. Data from seven studies were included in this category, in five of which (Buckley 1990; Hjortrup 1990; Kaukonen 1995; Luthje 2000; McQueen 1990) the participants underwent hip fracture surgery, and in two of which a range of closed fracture fixation procedures were carried out (Boxma 1996; Hughes 1991). Boxma 1996 used a third generation cephalosporin; the remainder evaluated second generation cephalosporins.

3. A single dose of parenteral antibiotic compared with multiple doses of the same agent. Data from two studies were included in this category, in one of which (Buckley 1990) the participants underwent hip fracture surgery, and in the other (Gatell 1987), a range of different closed fracture fixation procedures were carried out.

4. A single dose of parenteral antibiotic using an agent with a long half‐life, compared with multiple doses of other agents with shorter half lives. Data from three studies were included in this category. Garcia 1991 included both participants undergoing hip fracture surgery and others undergoing other closed fracture surgery. In Karachalios 1987 the participants underwent hip fracture surgery, and in Jones 1987b a range of different closed fracture fixation procedures were carried out.

5. Multiple doses of parenteral antibiotic administered over 24 hours or less, compared with a longer period of administration. Two studies (Hedstrom 1987; Nelson 1983;) whose participants underwent hip fracture surgery reported comparisons in this category.

6. Oral administration of antibiotic compared with parenteral administration. There was one study (Nungu 1995) in this category.

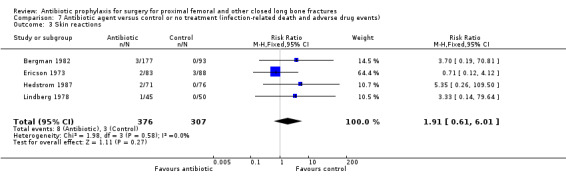

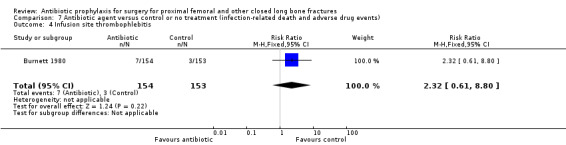

7. Antibiotic agent versus control or no treatment (infection‐related death and adverse drug events). Only one study (Burnett 1980) recorded the incidence of septicaemia, but data for infection‐associated death were available for eight studies (Boyd 1973;Buckley 1990; Burnett 1980; Ericson 1973; Garcia 1991; Gatell 1984; Kaukonen 1995; Tengve 1978). Only four studies contributed data on adverse events (Bergman 1982; Burnett 1980; Ericson 1973; Hedstrom 1987).

Risk of bias in included studies

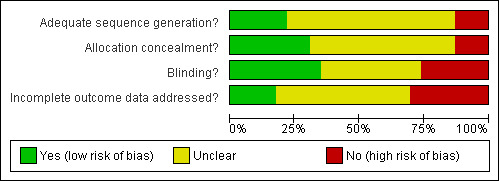

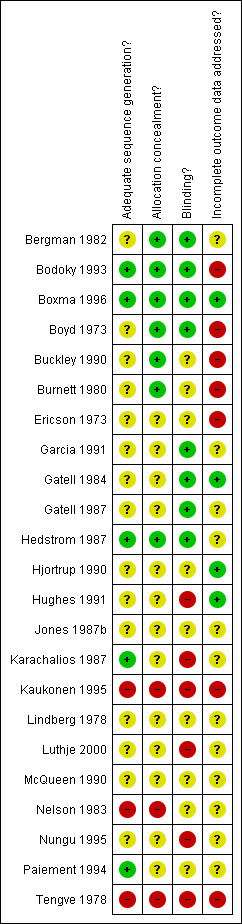

Summaries of the risk of bias assessment are shown graphically in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Only one study (Boxma 1996) was assessed as low risk of bias in all four domains. The method of sequence generation for randomisation indicated low risk of bias in five trials and was unclear in 15. There was a high risk of bias in the three quasi‐randomised trials (Kaukonen 1995; Nelson 1983; Tengve 1978). In seven trials the description of the randomisation process implied prior concealment of allocation, thus indicating low risk of bias; in 13 studies it was unclear, and in the three quasi‐randomised trials assignment was clearly not concealed. Blinding appeared adequate in eight trials, details were unclear in nine, and absent or inadequate blinding carried a high risk of bias in six studies. Incomplete outcome data was assessed as carrying low risk of bias in four studies, high risk of bias in seven, and was unclear in 12.

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Studies judged at high risk of bias for sensitivity analysis purposes were: Ericson 1973; Kaukonen 1995; Luthje 2000; Nelson 1983; Nungu 1995; Tengve 1978.

Effects of interventions

Results in each comparison category are shown in the analyses. We accepted that there was variation between studies in the reported definition of the main outcome measures, but considered that these definitions were clinically sufficiently consistent to permit pooling. Also, although the regimens of antibiotic prophylaxis within each category varied in respect of the agent and the details of timing, we found that all reported trials employed agents likely to be widely effective at the time of the study against Staphylococcus aureus, the principal organism implicated in post‐operative surgical site infection.

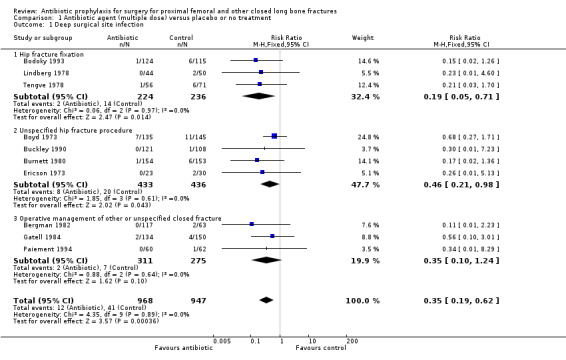

1. A pre‐operative dose and two or more post‐operative doses of parenteral (injected) antibiotic compared with a placebo or with no treatment

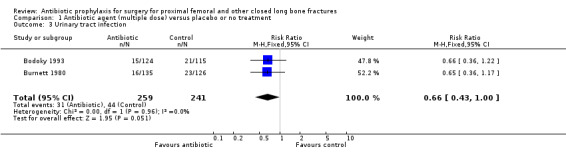

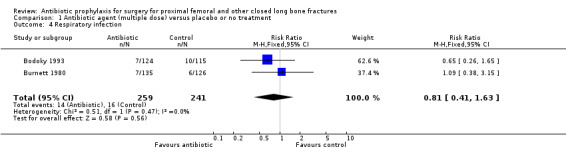

Data from 10 studies (1915 participants) were pooled for the deep surgical site infection outcome. Regimens in this category significantly reduced the incidence of deep surgical site infection (risk ratio (RR) 0.35, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 0.19 to 0.62; Analysis 1.1), and of superficial surgical site infection (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.66; Analysis 1.2), and may have reduced the incidence of infection of the urinary tract (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.00; Analysis 1.3). There was no significant reduction in the rate of respiratory infection (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.63; Analysis 1.4). The absolute risk of deep surgical site infection in the control group participants was 0.043, and the risk difference was ‐0.03, (95% CI ‐0.04 to ‐0.01).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic agent (multiple dose) versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 Deep surgical site infection.

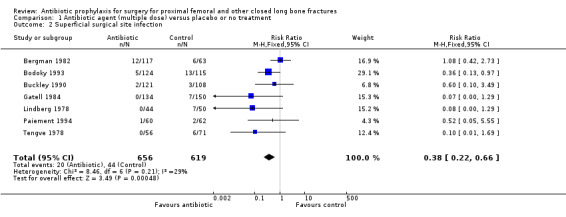

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic agent (multiple dose) versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 Superficial surgical site infection.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic agent (multiple dose) versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 Urinary tract infection.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic agent (multiple dose) versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4 Respiratory infection.

2. A single preoperative dose of parenteral antibiotic compared with a placebo or no treatment

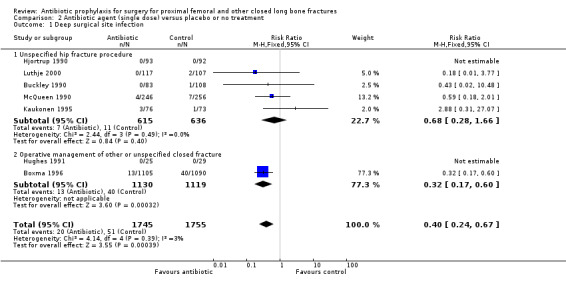

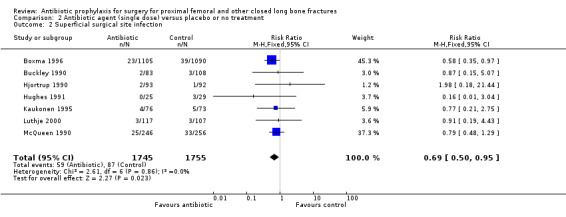

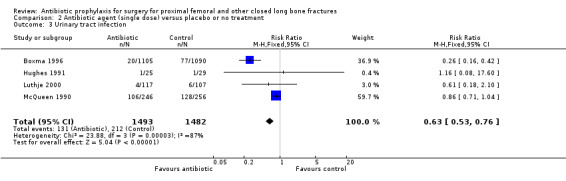

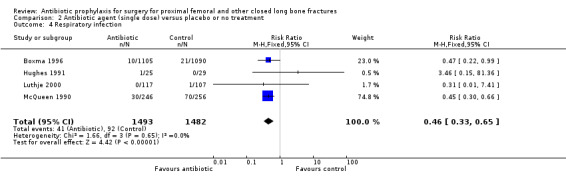

Data for deep surgical site infection were pooled from seven studies (3500 participants), including one large multi‐centre trial (Boxma 1996). Regimens in this category reduced the incidence of deep surgical site infection (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.67; Analysis 2.1), superficial surgical site infection (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.95; Analysis 2.2), urinary tract infection (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.76; Analysis 2.3), and respiratory infection (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.65; Analysis 2.4 ). The absolute risk of deep surgical site infection in the control group participants was 0.03, and the absolute risk reduction was ‐0.02 (95% CI ‐0.03 to ‐0.01).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antibiotic agent (single dose) versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 Deep surgical site infection.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antibiotic agent (single dose) versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 Superficial surgical site infection.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antibiotic agent (single dose) versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 Urinary tract infection.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antibiotic agent (single dose) versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4 Respiratory infection.

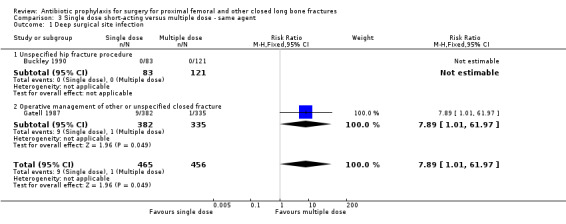

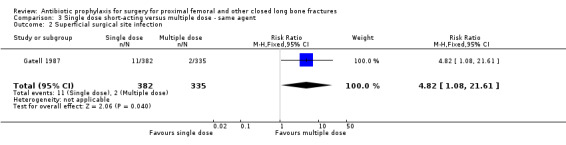

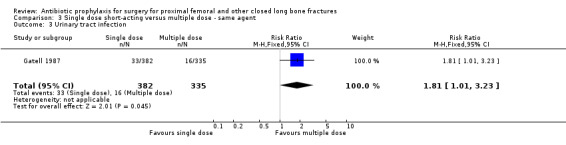

3. A single dose of short‐acting parenteral antibiotic compared with multiple doses of the same agent

Data for deep surgical site infection were pooled from two studies (921 participants), one of which (Gatell 1987) dominated the analysis by virtue of its size. A single dose of cefamandole, in the circumstances described in Gatell 1987 was less effective (with marginal statistical significance) than multiple doses in preventing deep surgical site infection (risk ratio 7.89, 95% CI 1.01 to 61.97; Analysis 3.1), superficial surgical site infection (RR 4.82, 95% CI 1.08 to 21.61; Analysis 3.2) and urinary tract infection (RR 1.81 to 95% CI 1.01 to 3.23; Analysis 3.3) after surgery for closed fracture than a multiple dose regimen (see Discussion for the implications of the sensitivity analysis).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Single dose short‐acting versus multiple dose ‐ same agent, Outcome 1 Deep surgical site infection.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Single dose short‐acting versus multiple dose ‐ same agent, Outcome 2 Superficial surgical site infection.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Single dose short‐acting versus multiple dose ‐ same agent, Outcome 3 Urinary tract infection.

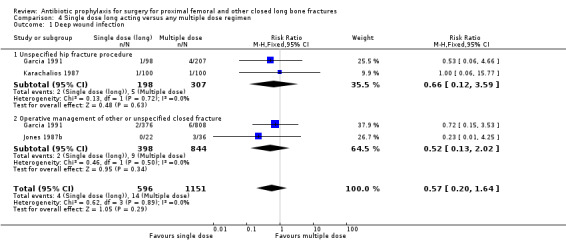

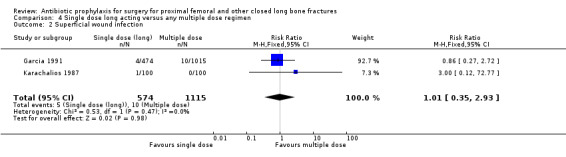

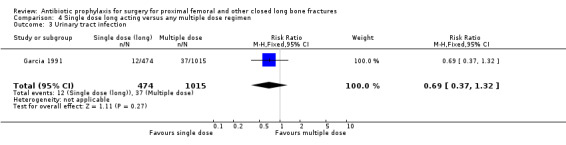

4. A single dose of parenteral antibiotic using an agent with a long half‐life, compared with multiple doses of other agents with shorter half life

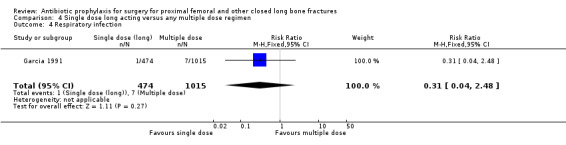

Data for deep surgical site infection were pooled from three studies (1747 participants) in this category. One of these (Garcia 1991) was a large trial of moderate quality, but despite its size, analysis of the pooled data failed to show a significant difference between the two types of regimen for the outcomes of deep surgical site infection (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.64; Analysis 4.1), superficial surgical site infection (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.35 to 2.93; Analysis 4.2), urinary tract infection (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.32; Analysis 4.3), or respiratory infection (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.04 to 2.48; Analysis 4.4).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Single dose long acting versus any multiple dose regimen, Outcome 1 Deep wound infection.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Single dose long acting versus any multiple dose regimen, Outcome 2 Superficial wound infection.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Single dose long acting versus any multiple dose regimen, Outcome 3 Urinary tract infection.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Single dose long acting versus any multiple dose regimen, Outcome 4 Respiratory infection.

5. Multiple doses of parenteral antibiotic administered over 24 hours or less, compared with a longer period of administration

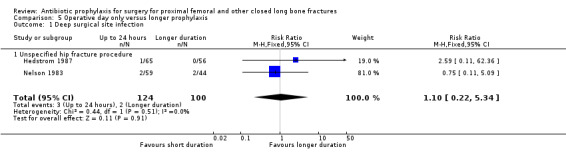

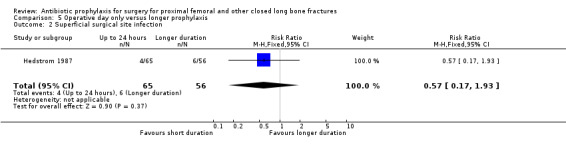

Data for deep surgical site infection were pooled from the two small studies (224 participants) in this category. There was no evidence of difference between the two types of regimen for the outcomes of deep (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.22 to 5.34; Analysis 5.1) or superficial surgical site infection (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.93; Analysis 5.2).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Operative day only versus longer prophylaxis, Outcome 1 Deep surgical site infection.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Operative day only versus longer prophylaxis, Outcome 2 Superficial surgical site infection.

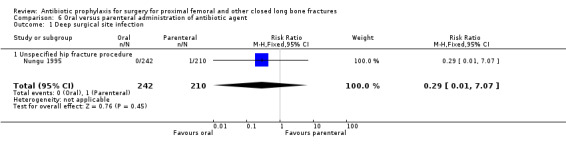

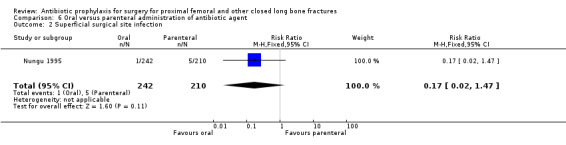

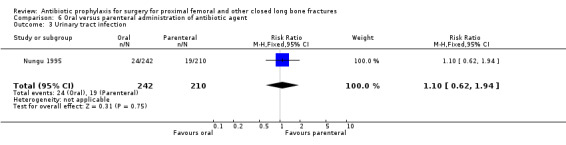

6. Oral administration of antibiotic compared with parenteral administration

One study (Nungu 1995) (452 participants) evaluated this comparison for the outcomes of deep and superficial surgical site infection, and urinary infection. No significant difference between the routes was demonstrated for deep infection (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.01 to 7.07; Analysis 6.1), superficial infection (RR 0.17, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.47; Analysis 6.2) or urinary infection (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.94; Analysis 6.3).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oral versus parenteral administration of antibiotic agent, Outcome 1 Deep surgical site infection.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oral versus parenteral administration of antibiotic agent, Outcome 2 Superficial surgical site infection.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oral versus parenteral administration of antibiotic agent, Outcome 3 Urinary tract infection.

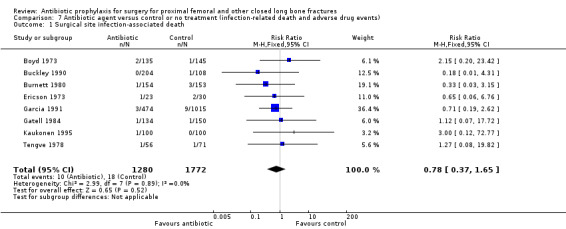

7. Antibiotic agent compared with control or no treatment (infection‐related death and adverse drug events)

Infection associated death

There was insufficient evidence from eight studies to demonstrate any effect of antibiotic prophylaxis on infection associated death (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.65; Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Antibiotic agent versus control or no treatment (infection‐related death and adverse drug events), Outcome 1 Surgical site infection‐associated death.

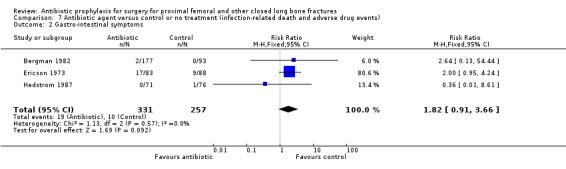

Adverse effects of antibiotic prophylaxis

Adverse events which might be associated with administration of antibiotics were more common in participants receiving prophylaxis than in controls, but the difference was not significant for gastro‐intestinal symptoms (RR 1.82, 95% CI 0.91 to 3.66; Analysis 7.2), skin reactions (RR 1.91, 95% CI 0.61 to 6.01; Analysis 7.3), or infusion site thrombophlebitis (RR 2.32, 95% CI 0.61 to 8.80; Analysis 7.4).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Antibiotic agent versus control or no treatment (infection‐related death and adverse drug events), Outcome 2 Gastro‐intestinal symptoms.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Antibiotic agent versus control or no treatment (infection‐related death and adverse drug events), Outcome 3 Skin reactions.

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Antibiotic agent versus control or no treatment (infection‐related death and adverse drug events), Outcome 4 Infusion site thrombophlebitis.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses are presented in Table 1, and discussed below.

1. Sensitivity analyses: deep surgical site infection.

| Comparison | Main analysis: RR [95% CI] | Sensitivity 1. Studies at high risk of bias removed from analysis | Sensitivity 2. Effect of losses to follow up |

| 1. AB multiple dose versus placebo | 0.35 [0.19 to 0.62] | 0.37

[0.20 to 0.69] Small reduction in point estimate of effect size: direction of effect unchanged. Two studies (Ericson 1973; Tengve 1978) were removed from this analysis. |

0.50

[0.30 to 0.83] Reduction in effect size: direction of effect unchanged |

| 2. AB single dose versus placebo | 0.40 [0.24 to 0.67] | 0.36

[0.21 to 0.62] Small reduction in point estimate of effect size: direction of effect unchanged Two studies (Kaukonen 1995; Luthje 2000) were removed from this analysis. |

0.48

[0.30 to 0.76] Reduction in effect size: direction of effect unchanged |

| 3. Single versus multiple doses same agent | 7.89 [1.01 to 61.97] | 7.89

[1.01 to 61.97] No change. No studies were removed from this analysis. |

4.09

[0.89 to 18.79] Difference no longer significant |

| 4. Single dose long acting versus any multiple dose regimen | 0.57 [0.20 to 1.64] | 0.57

[0.20 to 1.64] No change. No studies were removed from this analysis. |

0.57

[0.20 to 1.64] No change |

| 5. Operative day versus longer prophylaxis | 1.10 [0.22 to 5.34] | 2.59

[0.11 to 62.36] Change in point estimate of effect size: interpretation unchanged One study (Nelson 1983) was removed from this analysis. |

1.10

[0.22 to 5.34] No change |

| 6. Oral versus parenteral administration | 0.29 [0.01 to 7.07] | The single study in this analysis (Nungu 1995) was removed. | 0.29

[0.01 to 7.07] No change |

AB = antibiotic

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review confirms the effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing the risk of infection, both superficial and deep, after fracture surgery. The 23 trials reported were conducted over a period of 27 years. In the early studies, penicillins effective against gram positive cocci were used. As resistant organisms appeared, subsequent generations of penicillins, and then cephalosporins have been studied in prophylaxis against placebo or no treatment, or against other agents. The evidence for efficacy of prophylaxis in reducing the incidence of infections of the urinary and respiratory tracts, which were secondary outcome measures in many of the included trials, comes from studies which evaluated cephalosporins.

Over time, shorter durations of prophylaxis have been used. For effective prophylaxis, experimental evidence indicates that the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the antibiotic in the tissues must be exceeded for at least the period from incision to wound closure (Burke 1961). In practice, this initially meant using regimens with several consecutive doses, and the pooled data support their effectiveness. The availability of agents with a long elimination half life has allowed single dose prophylaxis reliably to meet Burke's prerequisite. Amongst published trials the large multi‐centre Netherlands trial (Boxma 1996), which used an antibiotic which provided concentrations exceeding MIC for 12 to 24 hours, dominates the analysis in this category. This trial supported the hypothesis that single dose intravenous prophylaxis is effective in reducing the incidence of both deep and superficial surgical site infection. The effect sizes are similar to those of from multi‐dose prophylaxis.

Direct comparisons of multiple and single dose prophylaxis have also been conducted by Gatell 1987 and Buckley 1990. Buckley 1990 was underpowered to distinguish between the two regimens tested. Gatell 1987, a large single centre study, concluded that single dose prophylaxis was inferior, but the statistical significance in the main analysis was marginal, and no longer present in one of the three plausible sensitivity analyses examining the effect of losses to follow up. Also, the tissue MIC may not have been reliably exceeded throughout the procedure for all participants in Gatell 1987, in which an agent (cefamandole 2 g) with a short half life was administered 30 minutes prior to the planned onset of surgery.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Despite the lack of power in many of the individual studies, pooling of the accumulated evidence supports the hypothesis of effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing surgical site infection. Boxma 1996 included an economic evaluation based on the effectiveness data which indicates a cost saving of a little under 500 US dollars per participant given prophylaxis. This may be conservative as the evaluation does not appear to take into account the costs of urinary and respiratory infections prevented.

Albers and colleagues (Albers 1994) have calculated that antibiotic prophylaxis for closed fracture surgery is cost effective if the absolute risk reduction of deep surgical site infection is 0.25% (0.0025) or more; the pooled estimates for absolute risk reduction for single dose or multiple dose prophylaxis in this review exceed that. We should note, however, that the economic analysis was based on a detailed study of 16 participants with infection (eight with deep surgical site infection, eight with superficial surgical site infection) compared with 16 participants without surgical site infection. From this small sample, it is possible that the true costs of uncommon adverse events may have been underestimated. Antibiotics are the major factor driving the emergence of drug resistance (Levy 2002), and the additional costs of antibiotic‐resistant infections are substantial (Roberts 2009). The ecological impact of antibiotic prophylaxis in closed fracture surgery was the focus of one of the ongoing studies (ISRCTN75423827) identified for this update.

Quality of the evidence

The trialists' reported definitions of outcome measures varied somewhat. In most reports, the definition of surgical site infection was clinical and did not require microbiological confirmation, although it was often sought. The duration of follow up varied, and it was not always clear whether late follow up was active or opportunistic. So it is possible that some late infections were missed, or that some participants whom we have included as sustaining superficial infections may have presented later with a deep infection.

Only one study (Boxma 1996) approached contemporary standards of conduct and reporting, and was assessed as being at low risk of bias. Using the approach to assessment across studies suggested in Table 8.7.a in Higgins 2009, risk of bias was assessed as high or unclear in one or more domain in the other 22 included studies; this leads to an overall assessment that the impact of bias in the individual studies on the results of this review is unclear. We discuss this in the next paragraph.

Potential biases in the review process

Since the reports of the methods and results of 21 of the 22 included studies in which risk of bias was unclear or high preceded the publication of the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement, first published in 1996, and updated in 2001 (Moher 2001), we have explored our results through the use of sensitivity analyses as described (seeData collection and analysis). We believe that the evidence from our meta‐analysis is robust. The sensitivity analyses (Table 1) showed that the results of all but one comparison were robust when risk of bias in the included studies was taken into account, both overall and with particular assessment of losses to follow up. The marginally significant difference between single and multiple dose prophylaxis, dependent on one study, was no longer evident in Analysis 3.1 on sensitivity analysis assuming a 2:1 distribution between multiple dose and single dose losses in Gatell 1987.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We found three other systematic reviews relevant to antibiotic prophylaxis for closed fracture management. Southwell‐Keely 2004 focused on hip fracture surgery and included 15 studies. Their findings were consistent with those of this review. Slobogean 2008 conducted a meta‐analysis of single versus multiple‐dose antibiotic prophylaxis in the surgical treatment of closed fractures and other clean orthopaedic surgery. Using slightly different inclusion criteria to those of this review, they included seven trials with 3,808 participants and found no evidence that single dose prophylaxis was inferior to a multiple dose regimen (RR 1.24; 95% CI 0.60 to 2.60). Their finding was also consistent with this review.

A recent systematic review and economic analysis (Cranny 2008) has addressed the issue of whether the choice of agent for routine antibiotic prophylaxis for surgery should take account of multiple antibiotic resistance amongst gram positive organisms by a switch from non‐glycopeptide to glycopeptide prophylaxis. Cranny 2008 concluded that there is at present "insufficient evidence to determine whether there is a threshold prevalence of MRSA at which switching from non‐glycopeptide to glycopeptide antibiotic prophylaxis might be clinically effective and cost‐effective".

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. Antibiotic prophylaxis for closed fracture surgery is an effective intervention for reducing the incidence of deep and superficial surgical site infection. Application of cost‐modelling has indicated that it also appears to be cost‐effective, although this model took no account of the impact of prophylaxis on the development of antibiotic resistance. 2. Single dose intravenous prophylaxis does not appear inferior to multiple dose regimens, particularly if the agent used provides tissue levels exceeding the minimum inhibitory concentration over a 12 hour period.

Implications for research.

1. Further placebo controlled trials to evaluate the effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in closed fracture surgery would be unlikely to be ethical. 2. Further trials comparing different antibiotic regimens would require to be very large to confirm differences between candidate regimens. 3. Economic analysis will continue to be important in choice of preferred antibiotic as established agents lose their efficacy due to resistance and new agents become available.

Feedback

Comment sent 12 January 1999

Summary

I very much enjoyed reading the new Cochrane review of antibiotic usage in fracture prosthetic surgery. This is full of fascinating information, and is a good marriage of high‐quality statistical and clinical input. I have made our Orthopaedic surgeons aware of the review's findings, and have proposed a change to our agreed prophylactic protocols as a result.

The review usefully examined the effects of long‐ and short‐half life agents, but another common point of debate is the choice of narrow‐spectrum (mainly isoxazolyl penicillin) versus broad‐spectrum (e.g. cefuroxime, or isoxazolyl penicillin plus gentamicin) prophylaxis. There is a suggestion in the classic Lidwell/MRC study reports that broad spectrum prophylaxis may reduce infection rates (by reducing deep Gram‐negative infections), but others have been concerned about costs, side effects (principally Clost. difficile diarrhoea) and induction of resistance associated with broader‐spectrum agents. Did the group consider this approach? Could it be examined in the future?

Reply

Many thanks for your interest in our review. We did not identify any trial which compared narrow and broad spectrum agents in the closed fracture population. There are in joint replacement (Pollard 1979;Vainionpaa 1988), and in open fracture management (Patzakis 1977); these studies were in our excluded trials table. If we have missed any that you know about, I would be most interested to hear of them. In Nelson 1983 (a study which we included comparing antibiotic versus placebo), the choice of antibiotic was at the discretion of the treating surgeon, but the trial did not compare these options. There seems to be evidence of a beneficial effect in limiting urinary tract infection when a cephalosporin was compared with a placebo (see the analyses in our review).

Contributors

Comment sent from: Dr Mark Farrington, Cambridge, UK Reply from: Prof William Gillespie, Dunedin, New Zealand Processed by: Dr Helen Handoll, Edinburgh, UK Dr Rajan Madhok, Hull, UK (criticism editor)

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 February 2010 | New search has been performed | Completion of new search (updated to December 2009). One additional study included, and details of two ongoing studies recorded. Three previously unidentified studies excluded. One study published in abstract in 1993, formerly in 'Studies awaiting classification', excluded. Risk of bias assessments completed for all included studies to replace previous methodological assessment. Sensitivity analysis of main results conducted to explore effects of risk of bias assessment. Presentation of methods, results, and discussion revised to meet current recommended structure, and provide greater clarity. The term "wound infection" changed where appropriate to "surgical site infection" in keeping with current practice. |

| 14 February 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Substantive reappraisal of the evidence using risk of bias assessment and sensitivity analyses. Terminology, presentation of methods, results, and discussion revised to meet current recommendations and practice. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1995 Review first published: Issue 4, 1998

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 November 2008 | New search has been performed | Converted to new review format. |

| 26 November 2000 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | This review was updated in Issue 2, 2001. This involved including data from a new randomised controlled trial (Luthje 2000) comparing a single dose antibiotic regimen with no prophylaxis. The conclusions of the review were unchanged. |

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the help of the following who assisted with searching, retrieval of studies, and methodological assessment for the 1998 version: Dr Helen Handoll, Mrs Lesley Gillespie, Dr Chris Hoffman. We would also like to thank the following for useful comments from the initial editorial review in 1998: Dr Helen Handoll, Dr Rajan Madhok, Prof Gordon Murray and Dr Antony Berendt. Dr Mario Lenza kindly translated a study identified for the 2009 update from Portuguese into English. Previous versions of this review were supported by Chief Scientist Office, Department of Health, The Scottish Office, Health Research Council of New Zealand, and the HealthCare Otago Endowment Trust, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

2009 update

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Wiley InterScience interface)

#1 MeSH descriptor Antibiotic Prophylaxis, this term only #2 MeSH descriptor Anti‐Bacterial Agents explode all trees #3 (antibiotic* or antimicrob*):ti,ab,kw in Clinical Trials #4 (#1 OR #2 OR #3) #5 MeSH descriptor Infection, this term only #6 MeSH descriptor Wound Infection explode all trees #7 MeSH descriptor Sepsis explode all trees #8 (infect*):ti,ab,kw in Clinical Trials #9 (#5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8) #10 MeSH descriptor Fractures, Bone explode all trees #11 MeSH descriptor Fracture Fixation explode all trees #12 (fractur*):ti,ab,kw in Clinical Trials #13 (#10 OR #11 OR #12) #14 (#4 AND #9 AND #13) (88 records)

MEDLINE (Ovid interface)

1. Antibiotic Prophylaxis/ 2. exp Antibiotics/ 3. (antibiotic$ or antimicrob$).tw. 4. or/1‐3 5. Infection/ 6. exp Wound Infection/ 7. Sepsis/ 8. infect$.tw. 9. or/5‐8 10. exp Fractures, Bone/ 11. exp Fracture Fixation/ 12. fractur$.tw. 13. or/10‐12 14. pc.fs. 15. and/4,9,13‐14 16. randomized controlled trial.pt. 17. controlled clinical trial.pt. 18. randomized.ab. 19. placebo.ab. 20. drug therapy.fs. 21. randomly.ab. 22. trial.ab. 23. groups.ab. 24. or/16‐23 25. exp Animals/ not Humans/ 26. 24 not 25 27. and/15,26 (144 records)

EMBASE (Ovid interface)

1. exp Antibiotic Agent/ 2. (antibiotic$ or antimicrob$).tw. 3. or/1‐2 4. exp Infection/ 5. infection prevention/ 6. Infection Complication/ 7. or/4‐6 8. exp Fracture/ 9. exp Fracture Treatment/ 10. fractur$.tw. 11. or/8‐10 12. and/3,7,11 13. exp Randomized Controlled trial/ 14. exp Double Blind Procedure/ 15. exp Single Blind Procedure/ 16. exp Crossover Procedure/ 17. Controlled Study/ 18. or/13‐17 19. ((clinical or controlled or comparative or placebo or prospective$ or randomi#ed) adj3 (trial or study)).tw. 20. (random$ adj7 (allocat$ or allot$ or assign$ or basis$ or divid$ or order$)).tw. 21. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj7 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 22. (cross?over$ or (cross adj1 over$)).tw. 23. ((allocat$ or allot$ or assign$ or divid$) adj3 (condition$ or experiment$ or intervention$ or treatment$ or therap$ or control$ or group$)).tw. 24. or/19‐23 25. or/18,24 26. limit 25 to human 27. and/12,26 (561 records)

International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (Ovid interface)

1. (antibiotic$ or antimicrob$).mp. 2. (infect$ or septic or sepsis).mp. 3. fracture$.mp. 4. and/1‐3 (16 records)

LILACS (BIREME interface)

((Pt RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL OR Pt CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL OR Mh RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS OR Mh RANDOM ALLOCATION OR Mh DOUBLE‐BLIND METHOD OR Mh SINGLE‐BLIND METHOD OR Pt MULTICENTER STUDY) OR ((Tw ensaio or Tw ensayo or Tw trial) and (Tw azar or Tw acaso or Tw placebo or Tw control$ or Tw aleat$ or Tw random$ or (Tw duplo and Tw cego) or (Tw doble and Tw ciego) or (Tw double and Tw blind)) and Tw clinic$)) AND NOT ((Ct ANIMALS OR Mh ANIMALS OR Ct RABBITS OR Ct MICE OR Mh RATS OR Mh PRIMATES OR Mh DOGS OR Mh RABBITS OR Mh SWINE) AND NOT (Ct HUMAN AND Ct ANIMALS)) [Words] and antibiotic$ or antimicrob$ [Words] and fract$ [Words] (1 record)

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment

Approach for risk of bias in individual studies

| Domain | Description requested for RM5 risk of bias table | Scoring rules |

|

Sequence generation Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? |

Describe the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups. |

Score “Yes” if a random component in the sequence generation was described e.g. use of a random number table, computer random number generator, coin‐toss, minimization Score “No” if a non‐random method was used e.g. date of admission, odd or even date of birth, case record number, clinician judgment, participant preference, risk factor score or test results, availability of intervention Score “Unclear” if sequence generation method was not specified |

|

Allocation concealment Was allocation adequately concealed? |

Describe the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to determine whether intervention allocations could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment. |

Score “Yes” if allocation concealment was described as by central allocation (telephone, web‐based, or sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes Score “No” if in studies using individual randomization investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments and thus introduce selection bias, e.g. assignment envelopes unsealed, non‐opaque, or not sequentially numbered, date of birth, case record number, clinician judgment, participant preference. Score “Unclear” if there was insufficient information to make a judgment of “yes” or “no” |

|

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study? |

Describe all measures used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. Provide any information relating to whether the intended blinding was effective. |

Score “Yes” if blinding of participants and key personnel was unlikely to have been broken Score “No” if appropriate placebo control was not provided in the “control” group OR assessment of infection was made by an assessor who was clearly not blinded to the allocated intervention Score “Unclear” if there was insufficient information to make a judgment of “yes” or “no” |

|

Incomplete outcome data Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? |

Describe the completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. State whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers in each intervention group (compared with total randomized participants), reasons for attrition/exclusions where reported, and any re‐inclusions in analyses performed by the review authors. |

Score “Yes” if there are no missing outcome data OR reasons for missing outcome data are likely to be unrelated to true outcome OR missing outcome data are balanced in number and reason for loss across groups )OR the proportion of missing outcomes, compared with the observed event risk, is unlikely to have a clinically relevant impact OR missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods Score “No” if there were missing outcome data, but these were likely to bias the result, since they did not meet criteria for a score of “yes” Score “Unclear” if details of losses are insufficient to make a judgment of “yes” or “no”. |

Approach for summary assessments of risk of bias (across domains) within and across studies

| Risk of bias | Interpretation | Within a study | Across studies |

| Low risk of bias | Plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results. | Low risk of bias for all key domains. | Most information is from studies at low risk of bias. |

| Unclear risk of bias | Plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results | Unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains. | Most information is from studies at low or unclear risk of bias. |

| High risk of bias | Plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results. | High risk of bias for one or more key domains. | The proportion of information from studies at high risk of bias is sufficient to affect the interpretation of the results. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Antibiotic agent (multiple dose) versus placebo or no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Deep surgical site infection | 10 | 1915 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.35 [0.19, 0.62] |

| 1.1 Hip fracture fixation | 3 | 460 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.05, 0.71] |

| 1.2 Unspecified hip fracture procedure | 4 | 869 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.21, 0.98] |

| 1.3 Operative management of other or unspecified closed fracture | 3 | 586 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.35 [0.10, 1.24] |

| 2 Superficial surgical site infection | 7 | 1275 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.22, 0.66] |

| 3 Urinary tract infection | 2 | 500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.43, 1.00] |

| 4 Respiratory infection | 2 | 500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.41, 1.63] |

Comparison 2. Antibiotic agent (single dose) versus placebo or no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Deep surgical site infection | 7 | 3500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.24, 0.67] |

| 1.1 Unspecified hip fracture procedure | 5 | 1251 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.28, 1.66] |

| 1.2 Operative management of other or unspecified closed fracture | 2 | 2249 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.17, 0.60] |

| 2 Superficial surgical site infection | 7 | 3500 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.50, 0.95] |

| 3 Urinary tract infection | 4 | 2975 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.53, 0.76] |

| 4 Respiratory infection | 4 | 2975 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.33, 0.65] |

Comparison 3. Single dose short‐acting versus multiple dose ‐ same agent.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Deep surgical site infection | 2 | 921 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.89 [1.01, 61.97] |

| 1.1 Unspecified hip fracture procedure | 1 | 204 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.2 Operative management of other or unspecified closed fracture | 1 | 717 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.89 [1.01, 61.97] |

| 2 Superficial surgical site infection | 1 | 717 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.82 [1.08, 21.61] |

| 3 Urinary tract infection | 1 | 717 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.81 [1.01, 3.23] |

Comparison 4. Single dose long acting versus any multiple dose regimen.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Deep wound infection | 3 | 1747 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.20, 1.64] |

| 1.1 Unspecified hip fracture procedure | 2 | 505 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.12, 3.59] |

| 1.2 Operative management of other or unspecified closed fracture | 2 | 1242 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.13, 2.02] |

| 2 Superficial wound infection | 2 | 1689 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.35, 2.93] |

| 3 Urinary tract infection | 1 | 1489 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.37, 1.32] |

| 4 Respiratory infection | 1 | 1489 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.04, 2.48] |

Comparison 5. Operative day only versus longer prophylaxis.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Deep surgical site infection | 2 | 224 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.22, 5.34] |

| 1.1 Unspecified hip fracture procedure | 2 | 224 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.22, 5.34] |

| 2 Superficial surgical site infection | 1 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.17, 1.93] |

Comparison 6. Oral versus parenteral administration of antibiotic agent.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Deep surgical site infection | 1 | 452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.01, 7.07] |

| 1.1 Unspecified hip fracture procedure | 1 | 452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.01, 7.07] |

| 2 Superficial surgical site infection | 1 | 452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.17 [0.02, 1.47] |

| 3 Urinary tract infection | 1 | 452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.62, 1.94] |

Comparison 7. Antibiotic agent versus control or no treatment (infection‐related death and adverse drug events).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Surgical site infection‐associated death | 8 | 3052 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.37, 1.65] |

| 2 Gastro‐intestinal symptoms | 3 | 588 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.82 [0.91, 3.66] |

| 3 Skin reactions | 4 | 683 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.91 [0.61, 6.01] |

| 4 Infusion site thrombophlebitis | 1 | 307 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.32 [0.61, 8.80] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bergman 1982.

| Methods | RCT Location: University Hospital, Sweden Recruitment period: 1974‐1977 Losses to follow up: none described | |

| Participants | 180 analysed (92 women, 88 men, mean age 47 years) Inclusion criteria: undergoing surgery for closed ankle fracture. Exclusion criteria: none described. | |

| Interventions | a. Dicloxacillin 2 g pre‐operatively and 6 hourly for 48 hours b. Benzyl penicillin 3 million international units (IU), same regimen c. Saline placebo, same regimen | |

| Outcomes | 1. Deep surgical site infection 2. Superficial surgical site infection 3. Adverse reactions | |

| Notes | This report also contains data for use of the same regimen in 90 open fractures. The total number of individuals given antibiotics was 270 (antibiotic 177, placebo 93); the adverse reaction data are reported and analysed using these denominators. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | "Random number" |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | "Drugs were packed in coded boxes according to random number" |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | No description. Placebo controlled, so assessor blinding probable. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | No losses described. |

Bodoky 1993.

| Methods | RCT Location: University Hospital, Switzerland Recruitment period: 1984‐1987 Losses to follow up: 45 of 284 (16%) | |

| Participants | 239 analysed (female 184, male 55, mean age 77 years) Inclusion criteria: undergoing internal fixation for intracapsular hip fracture. Exclusion criteria: pre‐existing infection, antibiotic allergy, antibiotic prophylaxis for other reason e.g. valve, immunosuppression, polytrauma. | |

| Interventions | a. Cefotiam 2 g at induction of anaesthesia; 2 g once 12 hours later b. Placebo at induction: once 12 hours later | |

| Outcomes | 1. "Major" surgical site infection. In the analysis, considered as "deep" 2. "Minor" surgical site infection In the analysis, considered as "superficial" 3. Urinary tract infection 4. Pulmonary infection 5. Septicaemia 6. Adverse drug effects 7. Infection related death | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | "Computer randomisation was performed by the pharmaceutical company." |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sequentially labelled packages assigned consecutively. Code unbroken until after completion of the study. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Code unbroken until after completion of the study. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Losses to follow up: 45 of 284 (16%). Insufficient description is available to assess the risk of bias due to this proportion of missing outcome data. |

Boxma 1996.

| Methods | RCT Location: Multi‐centre study, Netherlands Recruitment period: 1989‐1991 Loss to follow up: 249 of 2195 at 4 months (11.3%) | |

| Participants | 2195 analysed (female 1132 mean age 65, male 1063, mean age 44 years) Inclusion criteria: undergoing surgery for closed fracture. Exclusion criteria: external fixation or percutaneous wire fixation, pregnancy, immunosuppressive treatment, known hypersensitivity to cephalosporins, antimicrobial use or symptoms of infection in the week prior to surgery. | |

| Interventions | a. Ceftriaxone 2 g given intravenously at induction of anaesthesia for surgery b. Placebo by same regimen | |

| Outcomes | 1. Deep surgical site infection 2. Superficial surgical site infection 3. Respiratory infection 4. Urinary tract infection | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | "randomly allocated to receive a single dose of ceftriaxone (Rocephin, F Hoffmann‐La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) or placebo." "...numbered by use of blocked randomisation tables" |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | "Vials of ceftriaxone powder (2 g) and placebo, identical in appearance and numbered by use of blocked randomisation tables, were distributed to the local treatment centres in boxes of forty (twenty of each) and allocated sequentially in the order in which the patients were enrolled." "The groups were comparable with respect to demographic and clinical features such as sex ratio, age, injury severity score (ISS), underlying illnesses, and time in hospital before operation ... Nor were there any important inter‐group differences in the distribution of fracture types and locations or in such perioperative data as the time between fracture and surgery, the presence of invasive catheters, timing of drug administration, duration of surgery, use of tourniquets, drapes, and drains, or method of fracture fixation". |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "Group assignments were not disclosed to the physicians responsible for clinical evaluation or to the patients until the end of the study." |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | "Follow‐up was discontinued when superficial or deep surgical site infection developed. Other reasons for discontinuation were missing evaluations, further operations on the fracture, violation of protocol (for example, because of the need for additional antibiotics within 5 days after surgery), patient refusal, death, and loss to follow‐up." At final assessment at 4 months, losses (excluding deaths) were 75 of 1105 (6.8%) in the treatment group and 88 of 1090 (8.1%) in the placebo group. The authors reported that they had conducted "worst case" and "best case" sensitivity analyses and found the significant reduction in infections was maintained. |

Boyd 1973.

| Methods | RCT Location: University Hospital, Boston, USA Recruitment period: 1966‐1969 Losses to follow up: 68/348 (20%) | |

| Participants | 280 analysed (female 203, male 77, age range 40‐90+) Inclusion criteria: undergoing operative treatment for proximal femoral fracture, either fixation or endoprosthesis. Exclusion criteria: pre‐existing infection, Antibiotic allergy. | |

| Interventions | a. Nafcillin systemically 500 mg Theatre call; 500 mg 6 hourly i.m. for 48 hours b. Placebo (glucose in saline ) Theatre call; same regimen | |

| Outcomes | 1. Deep infection (all infected haematomas were treated as deep infections in the analysis) 2. Superficial infection 3. Adverse drug effects 4. Infection related death | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Insufficient detail |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | "The hospital pharmacists made two kinds of packets for the double‐blind study: (I) unmarked packets that each contained ten vials of 500 milligrams of sodium nafcillin in each vial, and (2) identical unmarked packets that each contained ten vials of 500 milligrams of sterile glucose in each vial. The packets were filled with either antibiotic or glucose, according to the plan for randomisation. The packets were each numbered and placed in serially numbered envelopes, the envelope corresponding to the patient’s study number, and were sent to the floor when requested by the nurse." |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "Neither the physician, the nurse, nor the patient knew whether antibiotic or glucose was being administered. .......The code was available to attending physicians when the information was necessary for the patient’s welfare. Any patient for whom the code had to be broken prematurely was followed but excluded from the tabulated results." |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | ".. sixty‐eight were excluded after randomization: fifty‐three because none of the medication doses prescribed for the study was received; thirteen in the treatment group (Group I) because the minimum dosage was not received, and one in the treatment group because hives developed; and one in the control group (Group II) because antibiotics were erroneously started on the first day after operation. The fifty‐three patients who were excluded after randomisation because they had not received any of the prescribed medications for the study were divided about equally between the control and treatment groups". |

Buckley 1990.

| Methods | RCT Location: University Hospital, Canada Recruitment period: 1985‐1988 Losses to follow up: 40/352 (12%) | |

| Participants | 312 analysed (female 225, male 87, mean age 77 years) Inclusion criteria: undergoing hip fracture surgery. Exclusion criteria: cephalosporin allergy, pathologic fracture, previous surgery on fractured hip, antibiotic treatment with other agent, more than 7 days in hospital before operation. | |

| Interventions | a. Cefazolin 2 g iv induction; 1 g 6 hourly iv 3 more doses b. Cefazolin 2 g iv induction; placebo (saline) 6 hourly iv 3 doses c. Placebo (saline) iv induction; placebo (saline) 6 hourly iv 3 doses | |

| Outcomes | 1. Deep surgical site infection 2. Superficial surgical site infection | |

| Notes | Numbers of participants allocated to groups a. multiple dose and c. placebo are reversed in some of the text (including the abstract) compared with the tables in the report. We used the numbers which were consistent with the results (percentages etc) given in the report. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | "Patients were allocated blindly and at random" |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | "Patients were allocated blindly and at random...... no‐one involved in the patient's primary care was aware of the group to which patient had been assigned" |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | "all patients had their surgical site checked by the wound study nurse". Not clear if this nurse was considered to be "involved in the patient's primary care .....no‐one involved in the patient's primary care was aware of the group to which patient had been assigned" |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Losses to follow up: 40/352 (12%) |

Burnett 1980.

| Methods | RCT Location: County hospital, Minneapolis, USA Recruitment period: 1973‐1977 Losses to follow up: 46/307 (15%) | |

| Participants | 261 analysed (161 women, 100 men, mean age 72 years) Inclusion criteria: undergoing hip fracture surgery. Exclusion criteria: history of allergy to cephalosporin, active infection requiring therapy, history of previous infection about the involved hip. | |

| Interventions | a. Cephalothin 1 g iv 4 hourly for 72 hours b. Placebo iv 4 hourly for 72 hours | |

| Outcomes | 1. Deep surgical site infection 2. Urinary tract infection 3. Pulmonary infection 4. Septicaemia 5. Death from infection | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | "on entry into the study, each patient was assigned a study number by the hospital pharmacist. Each number had previously been randomly assigned to either a cephalothin or placebo group". No table of characteristics of participants by assignment provided. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | "on entry into the study, each patient was assigned a study number by the hospital pharmacist. Each number had previously been randomly assigned to either a cephalothin or placebo group". Not entirely explicit, but likely to represent adequate concealment. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | "No one involved in the patient's primary care was aware of which assignment had been made" |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | 46 of 367 randomised were excluded from analysis, of whom 17 were "eliminated from the study at the discretion of the primary physician". Of the other 29, follow up was inadequate in 4, variations from protocol occurred in 26, and 3 participants died in the follow‐up period. High risk of bias. |

Ericson 1973.

| Methods | RCT Location: University and regional hospital, Sweden Recruitment period: 1970‐1972 Losses to follow up: 59/230 (25%) overall; losses for hip fracture subgroup not described. See notes. | |

| Participants | Subgroup of 53 analysed in this review. (39 internal fixation of trochanteric fracture, 14 hemiarthroplasty, mean age 70 years). Inclusion criteria: undergoing hip arthroplasty for arthritis, or hip fracture surgery. Exclusion criteria: none described. | |

| Interventions | a. Cloxacillin 1 g IM, 1 hour before operation and for three further doses at six hourly intervals. Thereafter 1 g orally 6 hourly, with probenecid 1 g twice daily until day 14 b. Placebo to same regimen | |

| Outcomes | 1. Surgical site infection (interpreted as deep infection) 2. Adverse drug reactions | |

| Notes | This report also contains data for use of the same regimen in total hip replacement for hip arthritis. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | States "consecutively and randomly assigned to antibiotic or placebo groups". Unclear whether randomisation was stratified |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | States only "consecutively and randomly assigned to antibiotic or placebo groups". |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | "The double‐blind technique was used". |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | The total number of participants recruited was 230, and of participants included in the analysis was 171 (antibiotic 83, placebo 88); the adverse reaction data are reported and analysed using these denominators. Losses were reasonably balanced in number from each group, but no data were available for the subgroup analysed in this review. |

Garcia 1991.

| Methods | RCT Location: University Hospital, Spain Recruitment period: 1987‐89 Losses to follow up: no losses described | |

| Participants | 1489 (976 female, 513 male, mean age 68 years) analysed. Inclusion criteria: undergoing fracture fixation surgery, of which 305 had a Moores arthroplasty inserted, 697 had an Ender nail inserted, and 487 had another device used to fix a closed fracture. Exclusion criteria: undergoing total joint replacement, known allergy to cephalosporin or penicillin, receiving immunosuppression or antibiotics for other infection, history of infection in the operative field, open fracture. | |

| Interventions | a. Cefonicid 2 g iv at induction of anaesthesia (474 participants) b. Cefamandole 2 g iv 3 doses (510 participants; 30 minutes pre‐op, 2, 8 hours) c. Cefamandole 2g iv 5 doses (505 participants; 30 minutes pre‐op, 2, 8, 14, 20 hours) | |

| Outcomes | 1. Deep infection 2. Superficial infection 3. Urinary tract infection 4. Respiratory infection 5. Infection related death | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | "The patients were randomly assigned ..." |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | "neither the patients nor the physicians involved in their evaluation knew which schedule of medication had been given" |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "neither the patients nor the physicians involved in their evaluation knew which schedule of medication had been given" |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Data provided for all 1489 participants enrolled. |

Gatell 1984.

| Methods | RCT Location: University Hospital, Spain Recruitment period: not given Losses to follow up: 16 of 300 (6%) | |

| Participants | 284 analysed (169 female, 145 male, mean age 55 years) Inclusion criteria: undergoing internal fixation of a long bone fracture. Exclusion criteria: participants having a total joint replacement or a procedure directly involving the hip joint, participants on immunosuppression or with a history of sensitivity to penicillins or cephalosporins. | |

| Interventions | a. Cefamandole 2 g by intravenous injection 30 minutes before surgery, and at 2, 8,14 and 20 hours after the start of surgery b. Placebo using the same regimen as group a. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Deep surgical site infection 2. Superficial surgical site infection | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | "Patients were randomly assigned ..." |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | "neither the patients nor the physicians involved in their evaluation knew which schedule of medication had been given" |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "neither the patients nor the physicians involved in their evaluation knew which schedule of medication had been given" |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Balanced losses to follow up: 16 of 300 (6%) (7 antibiotic, 9 placebo). All losses were attributed to variation from trial protocol. |

Gatell 1987.

| Methods | RCT Location: University Hospital, Spain Recruitment period: not described Losses to follow up: 33/750 (4%) | |

| Participants | 717 analysed (445 female, 272 male, mean age 65 years). Inclusion criteria: undergoing closed fracture fixation Exclusion criteria: open fractures, previous total joint replacement, known allergy to penicillin or cephalosporin, immunosuppressive treatment, previous infection in the operative field, already on antibiotics. | |

| Interventions | a. Single dose of cefamandole 2 g by intravenous injection 30 minutes before start of surgery and four doses of placebo at 2, 8,14, and 20 hours b. Cefamandole 2 g by intravenous injection 30 minutes before the start of surgery and at 2,8,14, and 20 hours | |

| Outcomes | 1. Deep infection 2. Superficial infection 3. Urinary tract infection | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | "Patients were randomly assigned.." |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | " the physicians involved in the evaluation of infection did not know which schedule of medication had been given" |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | " the physicians involved in the evaluation of infection did not know which schedule of medication had been given" |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Losses to follow up: 33/750 (4%). Distribution of losses between groups not described. |

Hedstrom 1987.

| Methods | RCT Location: University Hospitals, Sweden Recruitment period: 1982‐1984 Losses to follow up: 26/ 147 (18%) | |

| Participants | 121 analysed (female 87, male 34, mean age 77 years) Inclusion criteria: undergoing surgery for fixation of trochanteric fracture. Exclusion criteria: decreased renal function, severe senility, known or suspected allergy to penicillins or cephalosporins. | |

| Interventions | a. 1 day of prophylaxis (cefuroxime 750 mg thrice daily on the operative day followed by 6 days of placebo tablets) b. 7 days of prophylaxis (cefuroxime 750 mg thrice daily on the operative day followed by cephalexin 0.5 g thrice daily orally for 6 days) | |

| Outcomes | 1. Deep infection 2. Superficial infection 3. Adverse effects | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |