Abstract

The oxidative homocoupling of para-alkenyl phenols and subsequent trapping of the resulting quinone methide with a variety of oxygen and nitrogen nucleophiles was achieved. Both β-β and β-O coupling isomers can be synthesized via either C-C coupling and two nucleophilic additions of one water molecule (β-β isomer) or C-O coupling followed by one nucleophilic addition of a water molecule (β-O isomer), respectively. Selectivity between these outcomes was achieved by leveraging understanding of the mechanism. Specifically, a qualitative predictive model for the selectivity of the coupling was formulated based on catalyst electronics, solvent polarity, and concentration.

Keywords: vanadium, lignans, biomimetic, phenol oxidation, oxidative coupling, tetrahydrofurans

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Lignans are a class of molecules found abundantly in nature (Figure 1). Some natural products in this class have been found to possess potent biological activities including antimalarial1 antioxidant, antiparasitic, antifungal2, and antimicrobial properties.3 The tetrahydrofuranyl scaffold lignans have potent activity against T. cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas disease4 as well as being highly active platelet-activating factor (PAF) inhibitors.5

Figure 1.

Examples of alkenyl phenol homocoupling products found in nature.

Vanadium (V) oxo catalysts have been used to selectively and enantioselectivily homocouple hydroxy aryl systems, such as phenols, naphthols, and hydroxycarbazoles.6–10 We hypothesized that alkenyl phenols should also be oxidizable by this class of vanadium catalysts. These catalysts have the advantage of being able to be turned over by molecular oxygen and are relatively inexpensive to prepare compared to precious metal catalysts.

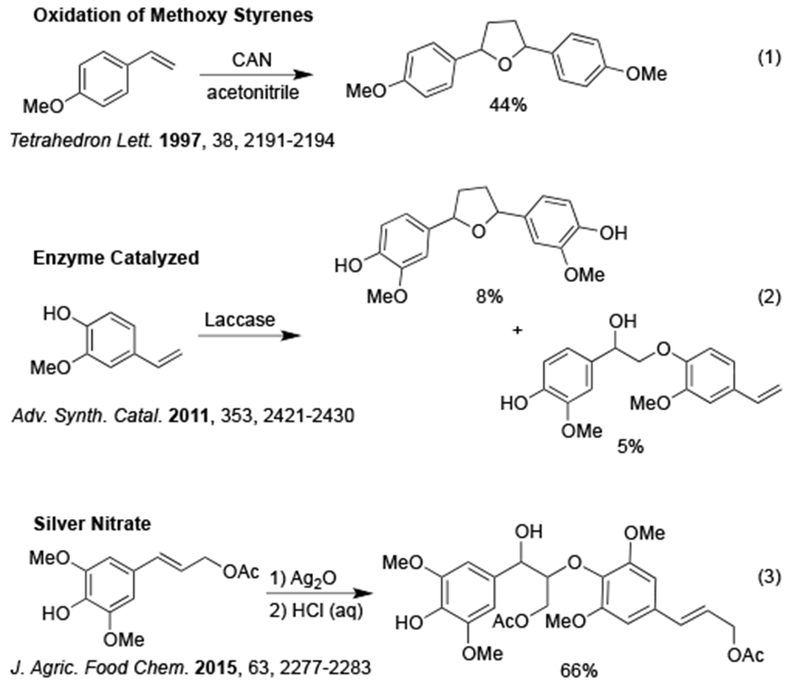

To the best of our knowledge, no general method exists to catalytically and oxidatively homocouple terminal alkenyl phenols selectively. In 1997, it was reported that para-methoxy styrene could be homocoupled to give the quinone intermediate that was trapped with water to form a diaryl furan (β-β coupling) in modest yields using ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN) (Scheme 1.1).11 In 2011, the oxidative enzyme laccase was studied with a simple styrene and was found to give a variety of oxidation products, including tetrahydrofuranyl and aryl ether scaffolds of interest, as a low yielding mixture (Scheme 1.2).12 In 2015, a method was reported to generate the aryl ether linkage (β-O coupling) seen in virolin. This method lacked generalizability and required stoichiometric silver as an oxidant (Scheme 1.3).13 While other methods to synthesize tetrahydrofuranyl lignans have been reported, none follow a biomimetic oxidative homocoupling route.14–15

Scheme 1.

Styrene and styrenyl phenol oxidative coupling to affect β-β coupling and β-O coupling

Results and Discussion

En route to synthesizing a carpanone16–17 analog utilizing a vanadium (V) catalyst, we discovered that a tetrahydrofuran product was formed instead (Scheme 2). Based on this outcome, ten equivalents of water were added to the reaction mixture in order to facilitate the formation of the tetrahydrofuran product. This strategy proved effective, resulting in a 46% yield of product as a mixture of cis and trans tetrahydrofuranyl isomers.

Scheme 2.

Discovery reaction

Curious as to whether para-alkenyl phenol substrates would react similarly, these substrates were also investigated. Notably, two avenues were observed arising from either C-C coupling and two nucleophilic additions of one water molecule (β-β isomer) or C-O coupling followed by one nucleophilic addition of a water molecule (β-O isomer). With substrate, 1b, which gives both β-β and the β-O coupling isomers in relatively high yield, solvent screening revealed a strong correlation between the ratio of the coupling products and the dipole moment of reaction solvent (Scheme 3). Using this data, conditions were devised that led to selectivity for either the β-β or β-O coupling products. Optimal results for the β-β coupling product were obtained in acetonitrile while 1,4-dioxane was best to generate the β-O coupling products.

Scheme 3. Optimization of selectivity by high-throughput experimentationa.

aRatios are of peak areas from UPLC analysis of the reaction mixture using UV-Vis detection with TWC.

Further screening was undertaken with catalysts having different electronic and structural properties (Figure 2). The yield and selectivity (Table 1) were not sensitive to the properties of the monomeric catalysts. However, the dimeric catalyst B gave 5.8:1 selectivity in favor of the β-O product (Table 1 Entry 2). This outcome could arise from either a synergistic effect between the two vanadium centers or from the effectively higher concentration of vanadium centers/catalytic sites in solution. Base additives seemed to suppress the desired reactivity (Table 1, Entries 6-9).

Figure 2.

Catalysts screened for selectivity.

Table 1.

Ratio of products from screening of catalysts and additivesa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Additive | Catalyst | % β-βa | % β-Oa | β-O/β-β |

| 1 | None | A | 28 | 68 | 2.4 |

| 2 | None | B | 12 | 70 | 5.8 |

| 3 | None | C | 19 | 73 | 3.8 |

| 4 | None | D | 22 | 66 | 3.0 |

| 5 | None | E | 14 | 49 | 3.5 |

| 6 | NaHCO3 | A | 18 | 12 | 2.8 |

| 7 | Na2CO3 | A | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| 8 | KOH | A | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| 9 | K2CO3 | A | 0 | 0 | N/A |

Yields determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the reaction mixture with CH2Br2 as internal standard.

From these observations it appears that the concentrations of both the catalytic species and substrate impact the selectivity. It was hypothesized that dilution of the reaction mixture would therefore result in different selectivity ratios by biasing pathways with lower molecularity (Figure 3). Two parallel sets of experiments were performed in acetonitrile and 1,4-dioxane, as these were found to give the best results for each isomer. For the trials in 1,4-dioxane it was found that a linear relationship existed between the selectivity ratio and the starting concentration of the phenol. At very low concentrations in 1,4-dioxane, only decomposition was observed. In acetonitrile, the selectivity followed a more logarithmic trend. In both cases lower concentrations resulted in more β-β coupling product, while higher concentrations gave more β-O coupling product.

Figure 3.

Dilution effects on selectivity. (Yields determined by NMR 1H NMR spectroscopy of the reaction mixture with CH2Br2 as internal standard. Reaction conditions: 10 mol% catalyst A, 16 h, 10 equiv water, 80 °C.)

A double reciprocal analysis of the selectivity versus the global concentration in acetonitrile showed a linear trend with excellent correlation (R2 = 0.98) (Figure 3, inset). This result indicated that at high concentration of substrate in acetonitrile the catalyst was being saturated by substrate while at low concentrations not all of the catalytic sites were being used.

On this basis, catalyst loading was expected to have an effect on selectivity. Indeed, in both 1,4-dioxane and acetonitrile there were strong linear relationships between catalyst loading and selectivity (Figure 4). In both solvents, the amount of β-O product increased with catalyst loading relative to β-β product. It is reasonable to conclude that a metal-bound pathway contributes more to the production of β-O coupling product than the β-β coupling product.

Figure 4.

Catalyst loading effect on selectivity. (Yields determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the reaction mixture with CH2Br2 as internal standard. Reaction conditions: x mol% catalyst A, 16 h, 10 equiv water, 0.2 M substrate, and 80 °C.)

To better understand these observations a series of experiments was performed to measure selectivity while changing the concentration of phenol and holding the concentration of catalyst constant (Figure 5). From the above observations it was expected that higher concentrations of phenol would lead to more β-β product relative to β-O coupling product. Indeed this trend was observed and, in conjunction with previous results, indicated that free phenol could be displacing bound oxidized phenol, allowing free phenoxy radical to couple in an uncatalyzed fashion to generate β-β coupling product.

Figure 5.

[Phenol] vs selectivity in 1,4-dioxane. (Ratios are of peak areas from UPLC analysis of the reaction mixture using UV-Vis detection with TWC. Reaction conditions: 0.724 mL dioxane, 0.01 M catalyst A, 16 h, 1 M H2O, and 80 °C.)

With this understanding, conditions could be rationally designed that would produce the β-β coupling product selectively (Table 2). The catalyst library was screened and again the ratio of isomers was insensitive to catalyst electronics. However, the electron-rich dimethylamino-substituted catalyst (catalyst A) gave fewer byproducts. This observation can be explained by the strong electron-donating groups on the ligand which stabilize the high oxidation state of the metal, making the catalyst a milder oxidant relative to the other variants. The reaction mixture was diluted as much as was operationally reasonable to minimize the coupling of catalyst bound intermediate and maximize the coupling of free phenoxy radicals. At very dilute (0.005M) concentration in acetonitrile, moderate yields of the β-β coupling product were obtained with 1:4 (β-O/β-β) selectivity.

Table 2.

Optimization of β-β couplinga

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | [Phenol](M) | Cat | % β-β | % β-O | β-O/β-β |

| 1 | 0.2 | A | 40 | 46 | 1.2 |

| 2 | 0.2 | B | 39 | 43 | 1.1 |

| 3 | 0.2 | C | 32 | 38 | 1.2 |

| 4 | 0.2 | D | 26 | 28 | 1.1 |

| 5 | 0.2 | E | 39 | 34 | 0.87 |

| 6 | 0.01 | A | 43 | 25 | 0.58 |

| 7 | 0.005 | A | 65 | 16 | 0.25 |

Yields determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the reaction mixture with CH2Br2 as internal standard.

Several common oxidants other than oxygen were tested to ensure a stronger oxidant was not needed to achieve higher yields. Substrate 1b was subjected to the conditions optimized for β-β coupling and the reaction mixture was measured by 1H NMR spectroscopy using an added internal standard. All four oxidants tested gave poorer performance and selectivity than with oxygen as the terminal oxidant for substrate 1d (Table 3). This result likely arises from direct over-oxidation of product by the other oxidants.

Table 3.

1H NMR yield for β-β and β-O coupling products using four chemical oxidants

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Oxidant | % 1ba | % β-O couplinga | % β-β couplinga |

| 1 | tert-butyl hydroperoxide (70% in H2O) | trace | 28 | 28 |

| 2 | (NH4)2S2O8 | 10 | 12 | trace |

| 3 | iodosobenzene | 10 | 12 | 52 |

| 4 | H2O2 (30% in H2O) | 30 | 20 | 32 |

Yields determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the reaction mixture with CH2Br2 as internal standard.

Seeing that control of selectivity could be achieved by selection of solvent, catalyst, and concentration, the mechanism was probed using TEMPO as a free radical trap. Two equivalents of TEMPO were added to the optimized β-β coupling conditions and TEMPO trapped products were isolated (see SI for experimental details and characterization data). This result indicates that free radical intermediates persist in solution (Scheme 4, intermediate 4). The major product was not the expected β-β coupling product as predicted for these conditions in the absence of TEMPO. It appears sequestering free phenoxy radical drove the reaction toward the β-O coupling product through a catalyst bound intermediate that interacts less readily with TEMPO.

Scheme 4.

Proposed mechanism for oxidative coupling of para-alkenyl phenols.

From the above data, the following mechanism is proposed (Scheme 4). First, free phenol undergoes ligand exchange with the catalyst and is oxidized to form intermediate 3. Binding of the phenol oxygen to the catalyst should be facile given the known Lewis acidity of vanadium (V) oxo catalysts.18 Evidence for coordination of the substrates was obtained with 51V NMR spectroscopy (see SI for details). Electron-rich phenols shift the 51V signal more significantly than electron-poor phenols. Mixing catalyst A or B with electron rich 2-fluoro-6-methoxy-4-vinyl phenol (1h) or 2,6-dimethoxy4-vinyl phenol (1j) substrates results in a quick loss of catalyst 51V signal and the appearance of a new signal downfield. In the case of the 2-iodo-6-methoxy4-vinyl phenol (1b) with catalyst B, the catalyst signal decreases and a smaller peak appears over several hours. The 51V signal is shifted further downfield the more electron-rich the ligand, as expected for complexes of vanadium (V).20–21 On the other hand, the 2-methoxy-6-nitro-4-vinyl phenol (1i) does not affect the vanadium chemical shift of either catalyst, indicating a very weak or disfavorable coordination. These results together indicate that electron-rich phenols interact more readily with the catalysts than electron-poor phenols, which is consistent with the observed reaction profiles (slower reactions for electron poor substrates, see below).

The reaction undergoes a single turnover when conducted under nitrogen indicating that the vanadium (V) species can act on the substrate without oxygen. The resultant intermediate 3 is biased to attack by the phenolic oxygen of unbound 4 to form the aryl ether bond giving intermediate 5, and after addition of water, the β-O coupling product 6. Coupling to form the C-O bond is preferred in this case because the Lewis acidic vanadium polarizes the bound substrate rendering the beta position harder and thus more susceptible to attack by oxygen instead of carbon. This result is consistent with the finding of more C-O at higher concentrations of the vanadium catalyst (allows sufficient 3 to be present; see Figure 4). Alternatively, the oxidized free radical species 4 could homocouple leading to the β-β coupling product 8, after addition of water. Dissociation from the catalyst is more likely in more polar solvents such as acetonitrile due to stabilization of the resulting cationic vanadium species such that less 3 is present, favoring C-C coupling and disfavoring C-O coupling. Coupling to form the C-C bond from the unbound phenolic radical is favored due to greater density of the SOMO at the β-carbon (see SI) as well as less steric hindrance at the β-carbon vs the oxygen. This sequence is consistent with the mechanism proposed for an enzyme catalyzed oxidative homocoupling of coniferyl alcohol.19

The substrate scope was explored for both the β-O coupling and the β-β coupling. For the β-O coupling (Scheme 5) scope, modestly electron-poor alkenyl phenols gave the best results. Very electron poor alkenyl phenols, like the nitro-substituted 1i, react more slowly requiring elevated reaction temperatures and leaving unreacted starting material. More electron-rich substrates are active but do not convert to the desired products under these conditions, instead a complex reaction mixture results. These observations are consistent with the hypothesized mechanism. Electron-poor phenols are harder to oxidize and require harsher conditions while more electron-rich phenols are more readily oxidized and may have a tendency to over-oxidize or decompose under the reaction conditions.

Scheme 5. Scope of the β-O couplinga.

aReaction at 1 mmol scale.

Unfortunately, phenols which are unsubstituted at one ortho position do not give significant amount of β-O product. Yields for the β-O coupled products are moderate, partially due to the instability of the product and difficult purification from related byproducts. However, no method has been reported for this coupling across such a range of substrates. Scaling up the reaction did impact the yield (Scheme 5, 6b). Substituted alkenes gave poorer yields (Scheme 5, 6f) compared to the unsubstituted counterparts, potentially due to greater steric hindrance toward attack by the phenoxy radical (Scheme 4, 3 to 5) or water (Scheme 4, 5 to 6).

Since water acts as the nucleophile to trap intermediate quinone methide 5 (Scheme 4), other nucleophiles were examined (Scheme 6). Addition of alcohol nucleophiles was effective using 1,2-dichloroethane as solvent (to more readily exclude water) using the highest yielding substrate (1b) and the optimal conditions for β-O coupling.

Scheme 6.

Scope of the β-O coupling with alcohol nucleophiles

The scope for the β-β coupling is more general and tolerates both electron-rich and electron-poor alkenyl phenol substrates (Scheme 7). Apparently, the low concentration of the reaction mixture reduces undesired side reactions and the tetrahydrofuranyl scaffold is more stable overall. The yields are moderate to good with 1.2-1.8:1 of the cis:trans tetrahydrofuran isomers. The yield and selectivity are not significantly impacted by the scale of the reaction (Scheme 7, 8j). In some cases, isolated yields are limited by difficulty purifying the product from isomers or decomposed species. The β-β and β-O reactions with water and aniline are especially effected, but reactions with alcohols are much easier to separate as the ether products (9d) have significantly different behavior on silica gel. Both mono and bis ortho-substituted phenols tolerated these reaction conditions, however a poor yield was seen for the mono substituted example (Scheme 7, 8p), most likely due to a greater number of possible byproducts.

Scheme 7. Scope of the β-β couplinga.

aDiastereomeric ratios of trans:cis were determined from comparison with 1H NMR spectra of analogous tetrahydrofurans.22 b1 mmol scale.

After exploring the scope of the β-β coupling, nucleophiles other than water were investigated as trapping agents for the intermediate quinone methide 7 (Scheme 4). Aniline was found to be an effective nucleophile in the β-β coupling (Scheme 8). Higher concentrations of substrate were needed to accelerate the reaction and to prevent decomposition of the aniline nucleophile.

Scheme 8.

β-β Coupling with aniline as the nucleophile

In conclusion, mechanistic experiments and strategic high throughput experimentation were investigated to rationally optimize reaction conditions and bias the outcome of the oxidative coupling of alkenyl phenols. The result is a general method to generate tetrahydrofuranyl lignan derivatives via a biomimetic coupling mechanism. We also report the synthesis of several aryl-ether coupling products, which to our knowledge, have no known catalytic synthesis. The products resulting from both methods can be further diversified by using either alcohol or aniline nucleophiles. Complex structures can be synthesized selectively in one step to afford multiple products from one substrate. These structures have potential biological relevance, due to their similarities to common natural products. The use of molecular oxygen as an environmentally benign terminal oxidant and the relatively low toxicity of vanadium minimizes the impact of waste streams.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to the NSF (CHE1764298) and the NIH (R35 GM131902, RO1 GM112684) for financial support of this research. Partial instrumentation support was provided by the NIH and NSF (1S10RR023444, 1S10RR022442, CHE-0840438, CHE-0848460, 1S10OD011980, CHE-1827457). Dr. Charles W. Ross III is acknowledged for obtaining accurate mass data.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures for all experiments and characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang H-J; Tamez PA; Hoang VD; Tan GT; Hung NV; Xuan LT; Huong LM; Cuong NM; Thao DT; Soejarto DD; Fong HHS; Pezzuto JM, Antimalarial Compounds from Rhaphidophora decursiva. Journal of Natural Products 2001, 64, 772–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rye CE; Barker D, Asymmetric Synthesis and Anti-protozoal Activity of the 8,4'-oxyneolignans Virolin, Surinamensin and Analogues. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2013, 60, 240–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teponno RB; Kusari S; Spiteller M, Recent Advances in Research on Lignans and Neolignans. Natural Product Reports 2016, 33, 1044–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartmann AP; de Carvalho MR; Bernardes LSC; Moraes M. H. d.; de Melo EB; Lopes CD; Steindel M; da Silva JS; Carvalho I, Synthesis and 2D-QSAR Studies of Neolignan-based Diaryl-tetrahydrofuran and -Furan Analogues with Remarkable Activity Against Trypanosoma cruzi and Assessment of the Trypanothione Reductase Activity. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2017, 140, 187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung KY; Kim DS; Oh SR; Park S-H; Lee IS; Lee JJ; Shin D-H; Lee H-K, Magnone A and B, Novel Anti-PAF Tetrahydrofuran Lignans from the Flower Buds of Magnolia fargesii. Journal of Natural Products 1998, 61, 808–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu L; Carroll PJ; Kozlowski MC, Vanadium-Catalyzed Regioselective Oxidative Coupling of 2-Hydroxycarbazoles. Organic Letters 2015, 17, 508–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang H; Herling MR; Niederer KA; Lee YE; Vasu Govardhana Reddy P; Dey S; Allen SE; Sung P; Hewitt K; Torruellas C; Kim GJ; Kozlowski MC, Enantioselective Vanadium-Catalyzed Oxidative Coupling: Development and Mechanistic Insights. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 2018, 83, 14362–14384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HY; Takizawa S; Sasai H; Oh K, Reversal of Enantioselectivity Approach to BINOLs via Single and Dual 2-Naphthol Activation Modes. Organic Letters 2017, 19, 3867–3870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang D-R; Chen C-P; Uang B-J, Aerobic Catalytic Oxidative Coupling of 2-naphthols and Phenols by VO(acac)2. Chemical Communications 1999, 1207–1208. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo Z; Liu Q; Gong L; Cui X; Mi A; Jiang Y, The Rational Design of Novel Chiral Oxovanadium(iv) Complexes for Highly Enantioselective Oxidative Coupling of 2-naphthols. Chemical Communications 2002, 914–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nair V; Mathew J; Kanakamma PP; Panicker SB; Sheeba V; Zeena S; Eigendorf GK, Novel Cerium(IV) Ammonium Nitrate Induced Dimerization of Methoxystyrenes. Tetrahedron Letters 1997, 38, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gavezzotti P; Navarra C; Caufin S; Danieli B; Magrone P; Monti D; Riva S, Synthesis of Enantiomerically Enriched Dimers of Vinylphenols by Tandem Action of Laccases and Lipases. Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis 2011, 353, 2421–2430. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kishimoto T; Takahashi N; Hamada M; Nakajima N, Biomimetic Oxidative Coupling of Sinapyl Acetate by Silver Oxide: Preferential Formation of β-O-4 Type Structures. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2015, 63 (8), 2277–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jagtap PR; Císařová I; Jahn U, Bioinspired Total Synthesis of Tetrahydrofuran Lignans by Tandem Nucleophilic Addition/redox Isomerization/oxidative Coupling and Cycloetherification Reactions as Key Steps. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2018, 16, 750–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albertson AKF; Lumb J-P, A Bio-Inspired Total Synthesis of Tetrahydrofuran Lignans. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2015, 54, 2204–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liron F; Fontana F; Zirimwabagabo J-O; Prestat G; Rajabi J; Rosa CL; Poli G, A New Cross-Coupling-Based Synthesis of Carpanone. Organic Letters 2009, 11, 4378–4381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman OL; Engel MR; Springer JP; Clardy JC, Total Synthesis of Carpanone. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1971, 93, 6696–6698. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rana S; Haque R; Santosh G; Maiti D, Decarbonylative Halogenation by a Vanadium Complex. Inorganic Chemistry 2013, 52, 2927–2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davin LB; Lewis NG, Dirigent Phenoxy Radical Coupling: Advances and Challenges. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2005, 16, 398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cornman CR; Colpas GJ; Hoeschele JD; Kampf J; Pecoraro VL, Implications for the Spectroscopic Assignment of Vanadium Biomolecules: Structural and Spectroscopic Characterization of Monooxovanadium(V) Complexes Containing Catecholate and Hydroximate Based Noninnocent ligands. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1992, 114, 9925–9933. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Priebsch W; Rehder D, Preparation and vanadium-51 NMR Characteristics of Oxovanadium(V) Compounds. Relation Between Metal Shielding and Ligand Electronegativity. Inorganic Chemistry 1985, 24, 3058–3062. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imada Y; Okada Y; Noguchi K; Chiba K, Selective Functionalization of Styrenes with Oxygen Using Different Electrode Materials: Olefin Cleavage and Synthesis of Tetrahydrofuran Derivatives. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2019, 58, 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.