Abstract

The probability flux and velocity in stochastic reaction networks can help in characterizing dynamic changes in probability landscapes of these networks. Here, we study the behavior of three different models of probability flux, namely, the discrete flux model, the Fokker-Planck model, and a new continuum model of the Liouville flux. We compare these fluxes that are formulated based on, respectively, the chemical master equation, the stochastic differential equation, and the ordinary differential equation. We examine similarities and differences among these models at the nonequilibrium steady state for the toggle switch network under different binding and unbinding conditions. Our results show that at a strong stochastic condition of weak promoter binding, continuum models of Fokker-Planck and Liouville fluxes deviate significantly from the discrete flux model. Furthermore, we report the discovery of stochastic oscillation in the toggle-switch system occurring at weak binding conditions, a phenomenon captured only by the discrete flux model.

I. INTRODUCTION

Networks of chemical reactions can depict how interactions among molecules of DNA, RNA, and protein regulate gene expression. These networks, called gene regulatory networks, play important roles in biological processes such as cell fate determination,1,2 signal transduction,3,4 and metabolic regulations.5,6 When genes, transcription factors, signaling molecules, and regulatory proteins are in small quantities, stochasticity plays important roles.7–9 Characterizing the probability surfaces of molecules of gene regulatory networks can help us to understand their behavior.

The general stochastic process dictated by chemical reactions has two complementary representations, one in the form of a reaction path or reaction trajectory and another in the form of a time-evolving probability density function. The microstates of the chemical reaction system are integer vectors of copy numbers of different types of molecules. Specifically, the Stochastic Chemical Kinetics (SCK) processes of reactions can be described either by trajectories of reaction paths, which follow random-time changed integral equations of the Poisson process,10,11 or by the time-evolving probability density function governed by the discrete chemical master equation.12–14

The Stochastic Simulation Algorithm (SSA) and related methods11,15–18 can be used to generate trajectories of reaction paths following the random time changed Poisson integral equation. A number of methods have also been developed, which can be used to compute the time-evolving probability density function.19–23 Among these, the ACME (Accurate Chemical Master Equation) method constructs an explicit state space optimally enumerated on an n-simplex and can be used to compute the time-evolving probability density function for a large number of networks, with truncation errors a priori bounded.22,23

When the microstates of the reaction system are approximated as vectors in the continuous space, the corresponding continuous stochastic processes can be represented either by reaction trajectories following stochastic differential equations (SDEs) such as the chemical Langevin equation16 or by the time-evolving probability density governed by the Fokker-Planck equation.24–29

Ordinary differential equation models, under further simplifying assumptions of large copy numbers in large volume, can describe changes in mean concentrations of the molecular species, although stochasticity is not taken into account.30,31

Furthermore, it is also essential to characterize the probability flux in reaction systems for understanding the biochemistry of living things.24,25,32–37 Probability flux and velocity field can help us to infer the mechanisms of network functions such as switching between cellular states32,33 and to identify barriers and checkpoints between cellular states.28 Furthermore, the flux and velocity fields of probability can characterize the departure of nonequilibrium steady state from equilibrium, aiding in understanding of the nonlinear behavior of these networks.29,36,38 Computing probability fluxes and velocity fields has also found applications in studies of stem cell differentiation,39 cell cycle,28 and cancer development.40,41

Among early studies of probability fluxes, Hill examined reaction fluxes of the discrete-state continuous-time Markov model and introduced various forms of fluxes, including one-way transition flux, net flux, cycle fluxes, and operational flux.42 Hill’s study and many subsequent important studies are based on a view centered on reactions, where states correspond to specific nodes on diagrams of kinetic reactions, representing various forms of molecular species. We regard these models of fluxes as those of Lagrangian fluxes. An alternative view is to center on microstates in the state space, which are integer vectors of copy numbers. With this viewpoint, one examines fluxes resulting from firing of different chemical reactions, which flow into and out of individual fixed microstates. We regard such models of fluxes as Eulerian fluxes.

The universal discrete flux model based on chemical stochastic kinetics was developed in a previous study for arbitrary stochastic networks of chemical reactions,37 with the Eulerian fluxes formulated based on the discrete calculus defined for chemical stochastic kinetics. Relationships between the discrete Eulerian fluxes and reaction-based discrete Lagrangian fluxes were also given. This model enables the construction of global flow-maps of fluxes in all directions at every microstate while satisfying the discrete version of the continuity equation. It can also be used to tag the probability fluxes of outflow and inflow as reactions proceed.37

While different models have been used to analyze gene regulatory networks, it is important to understand their applicability and limitations. For analysis of the probability distribution of microstates, models based on ordinary differential equations are generally not applicable to stochastic systems, for example, those with low copy numbers of molecules or with large differences in reaction rates.31,43–45 Models based on continuum approximations of the discrete Markov jump processes also have limitations: Fokker-Planck models may fail to capture the presence of multistability arising from slow switching between the ON and the OFF states.46 Moreover, when systems are far from equilibrium, the probability landscape constructed using models based on continuum approximations is also of inadequate accuracy.47 In general, the applicability and validity of these models for a specific network needs to be investigated individually.14,31,44–50

Assessing the applicability and limitations of different models in the analysis of probability flux and velocity is more challenging. In this work, we study the applicability and the limitations of three classes of flux models. The first is the universal discrete flux models based on the original stochastic chemical kinetic model.37 This model overcomes limitations in previous discrete models of probability flux and velocity in Refs. 32 and 51–54, such as restrictions to analysis of single reactional trajectories,51,52 to partial flux functions,32,53 or to single-species reactions.54

Our second class of models are diffusion approximations of the stochastic chemical kinetics, which can be represented either by the chemical Langevin equation for its stochastic trajectories16 or by the Fokker-Planck equation for its time-evolving probability density.24–29 The Fokker-Planck model we study is derived from the Kramers-Moyal expansion of the discrete chemical master equation following Ref. 24. Our third class of models is a novel probability flux model called the Liouville flux model, which is the deterministic limit of the stochastic kinetic models. It is based on chemical rate equations and ordinary differential equations (ODEs). Although deterministic models of flux based on ODEs are generally not applicable to gene regulatory networks, the Liouville flux model treats the probability flux with a precomputed probability distribution at individual states. It can be directly compared with the universal discrete flux and the Fokker-Planck flux.

We examine the behavior of the probability fluxes using the toggle switch system. We study the steady state fluxes under two conditions: (i) when the binding rates of the transcription factors to promoters of genes are much higher than the unbinding rates, under which the system exhibits three stable states, and (ii) when the unbinding rates are of the same magnitude as the binding rates, under which the system is strongly stochastic and exhibits four stable states. Our results show that fluxes computed with these three different models all have similar behavior under the first condition, but exhibit markedly different behaviors under the second condition. Furthermore, we show that the universal discrete stochastic flux can uncover the oscillating behavior of the toggle switch system at the nonequilibrium steady state, while the Fokker-Planck and Liouville models fail to capture this highly stochastic phenomenon.

Our paper is organized as follows: We first introduce the three flux models and give closed-forms of the differences among these models. We then examine the details of the differences in probability fluxes in the toggle switch network under the two conditions.

II. MODELS AND METHODS

A. Model of biochemical reactions networks

We consider a well-mixed system of reactions with constant volume and temperature. It has n molecular species Xi, i = 1, …, n, which participate in m reactions Rk, k = 1, …, m. The microstate x(t) of the system at time t is a column vector of copy numbers of the molecular species: , where all values are non-negative integers. A reaction Rk takes the general form of

so that Rk brings the system from a microstate x to x + sk, where the stoichiometry vector sk is defined as

| (1) |

which gives the unit vector of the discrete increment of reaction Rk. sk also defines the direction of Rk.

B. Discrete chemical master equation (dCME)

The discrete Chemical Master Equation (dCME) consists of a set of linear ordinary differential equations describing the changes of probability over time at each microstate of a reaction system.2,11,20,55 Denote the probability of the system to be at a particular microstate x at time t as . Denote the probability surface or landscape over the state space Ω as p(t) = {p(x(t)|x(t) ∈ Ω)}. The dCME at an arbitrary microstate x = x(t) can be written in the general form as

| (2) |

x − sk, x ∈ Ω. Here, the reaction propensity Ak(x) is determined by the product of the intrinsic reaction rate rk and the combinations of copies of relevant reactants at the current microstate x: .

For computing the probability distribution, we employ the recently developed ACME method22,23 to solve the dCME underlying the stochastic network and obtain its exact time-evolving probability surfaces. This eliminates potential problems arising from inadequate sampling, where rare events of low probability are difficult to quantify using techniques such as the stochastic simulation algorithm (SSA).11,17,18,56

C. Continuum approximations of dCME

1. Deterministic equation from the law of mass action

The deterministic model of reactions describes the time-evolving mean value or concentration ⟨Xi⟩ of each molecular species Xi. The ordinary differential equations can be written generically at ⟨X⟩ = (⟨X1⟩, …, ⟨Xn⟩) as

| (3) |

Here, the functions

| (4) |

characterize how the vector of molecular concentrations ⟨X⟩ changes with time.

A standard approach for such a characterization is based on chemical rate equations.57 Here, the rate of a chemical reaction is directly proportional to the product of the activities or concentrations of the reactants. Therefore, functions Fi(⟨X⟩) in Eq. (4) can be written as

| (5) |

where are the components of stoichiometry vector sk and rk is the intrinsic reaction rate of reaction Rk.

The law of mass action can be derived from the dCME [Eq. (2)] using the theory of moment-closure approximations at high copy numbers.43,58–60

2. Approximation model of the Fokker-Planck equation

The continuous diffusion approximation in the form of a Fokker-Planck model can be derived from the discrete chemical master equation under the assumptions of (i) small jumps between states due to firing of reactions, namely, |sk/V| < ϵ, where , and (ii) slow changes of the probability, namely, |p(x) − p(x + sk/V)| < δ, where for reaction Rk, whose stoichiometry is sk and the system volume is V. With these assumptions, the transition kernel Ak(x − sk/V)p(x − sk/V, t) is differentiable to a high degree.

The model of the Fokker-Planck equation considered in this work is derived from the multivariate Taylor expansion or the Kramers-Moyal expansion of the dCME,24

| (6) |

In Fokker-Planck models, terms higher than two are neglected.24

D. Continuity equation of probability

The evolution of the probability landscape can be viewed as a process of movement of probability mass in the state space. The total probability mass is conserved at any time and sums up to one. This is captured by the continuity equation for probability.61,62 It is defined on a set of average molecular mass concentrations ,

| (7) |

which defines J(⟨X⟩, t), the vector of probability flux, namely, the flow of probability in the direction of each species.

As the velocity of the probability is related to the flux by the relationship v(⟨X⟩, t) = J(⟨X⟩, t)/p(⟨X⟩, t), the continuity equation can also be written for velocity as

| (8) |

Similar to Eq. (7), a discrete version of the continuity equation,

| (9) |

holds for the total reactional flux defined in Ref. 37.

E. Models of probability flux

1. Liouville flux model

Here, we introduce a Liouville flux model based on the ordinary differential equations for mean concentrations of molecules from mass action. It is a set of forward differential equations in which the increment in the mean concentration of molecular specie over time ∂⟨X⟩/∂t, given ∂t → 0, defines the Liouville velocity vL(⟨X⟩, t) of reactional mass of the average molecular concentration ⟨X⟩,

where the components of F(⟨X⟩, t) are defined by Eq. (5).

To compare with other flux models, we now restrict the values of the function vL = vL(⟨X⟩, t) to the discrete state space Ω, where the probability values are computed using the ACME method.22,23 We use the notation vL ≡ vL(x, t).

The Liouville flux is defined in the discrete subset Ω of the continuous space U as

| (10) |

2. Fokker-Planck flux model

We rewrite the right-hand side of Eq. (6) by taking the operator ∇x(·) outside the parentheses,

From Eq. (7), the flux for the Fokker-Planck model JFP(x, t) can be written as follows:

| (11) |

The Fokker-Plank flux equation (11) has two components: the drift term of and the diffusion term of . The drift term is driven by chemical reactions occurring at x. The diffusion term approximates linearly the stochastic fluctuations of the system.

3. Universal discrete flux model

A model of discrete flux was recently introduced in Ref. 37. As it can account for both reactional flux and species flux, we call it the universal discrete flux model. Briefly, we define an unambiguous order of ascending relationship “≺” over all microstates and have them ordered as .37 The single-reactional flux of probability for reaction Rk is

Jk(x, t) depicts the change in p(x, t) at the state x due to one firing of reaction Rk. If x ≺ x + sk, Jk(x, t) describes the outflux at x due to one firing of reaction Rk. If x ≺ x − sk, Jk(x, t) describes the influx to x due to one firing of reaction Rk.

The total reactional flux or r-flux Jr(x, t), which describes the probability flux at a microstate x at time t, is defined as37 Intuitively, the r-flux Jr(x, t) is the vector of rate change of the probability mass at x in directions of all reactions. Jr(x, t) satisfies the discrete continuity equation (9). Details can be found in Ref. 37.

The total species flux, or s-flux, is the sum of the stoichiometry projections of m single-reaction species flux vectors at a microstate ,

| (12) |

F. Differences between flux models

We now compare the three flux models and define analytically their differences.

1. Difference between discrete flux and Fokker-Planck flux

The difference between the universal discrete flux of Eq. (12) and the Fokker-Planck flux of Eq. (11) at V = 1 is

| (13) |

For reactions generating discrete flux out-flowing from x to x + sk, the values of the discrete flux and Fokker-Planck flux differ only in the diffusion term of the Fokker-Planck flux. For reactions generating flux flowing-in from x − sk to x, the discrete flux and Fokker-Planck flux differ in both the diffusion term and the drift term.

We examine the difference further by taking the linear Taylor expansion: Ak(x − sk)p(x − sk, t) ≈ Ak(x)p(x, t) − sk∇xAk(x)p(x, t). While the gradient of the flux defines the change of the probability with time from the continuity equation, we now skip the second-order term of the Taylor expansion. Equation (13) now becomes

Hence, the drift terms for both fluxes are the same and equal to Ak(x)p(x, t). The difference in these two flux models resides only in the noise encoded by the diffusion term.

2. Difference between Liouville flux and Fokker-Planck flux

The difference between the Fokker-Planck flux from Eq. (11) and the Liouville flux from Eq. (10), given V = 1, is

| (14) |

In this case, difference exists in both the drift term and the diffusion term.

However, for the special case when there is only one type of reactant and |sk| = 1, we have F(x, t)p(x, t) = skAk(x)p(x, t). In this case, the drift terms of the two fluxes are the same.

Moreover, in the limiting case of large concentrations, we have . Therefore, the difference between the Fokker-Planck flux and Liouville flux is only in the diffusion term, which is generally of the order of .

3. Difference between discrete flux and Liouville flux

The difference between the discrete universal flux [Eq. (12)] and the Liouville flux [Eq. (10)] is

| (15) |

We consider the special case of reactions involving only a single molecule species of reactants with |sk| = 1. We have F(x, t)p(x, t) = skAk(x)p(x, t). For reactions with the probability flux flowing from x to x + sk (x − sk ≺ x), both fluxes are the same. For reactions with the probability flux flowing from x − sk to x, we can examine this difference by taking the linear terms of the Taylor expansion of Ak(x − sk)p(x − sk, t) ≈ Ak(x)p(x, t) − sk∇xAk(x)p(x, t). Equation (15) now becomes

In this case, under the assumption F(x, t)p(x, t) = skAk(x)p(x, t), the drift terms are the same. The fluxes differ only in the diffusion term sk∇xAk(x)p(x, t).

III. RESULTS

A. The multistable toggle switch model

1. Network and reactions

The toggle switch network consists of two genes whose protein products mutually inhibit each other. This network plays important roles in molecular decision-making and is widely found in nature.63–67 The toggle switch has been studied extensively, with its stability, dynamics, switching mechanisms, and most-probable paths analyzed through outflow probability fluxes,32 quasipotential landscape reconstruction,68 as well as weighted-ensemble trajectory simulations using the string-method.33 In this study, we employ a detailed model of the toggle switch,20,69 where the binding and unbinding reactions are explicitly modeled. This is different from the simplified model used in several other studies.63,70,71

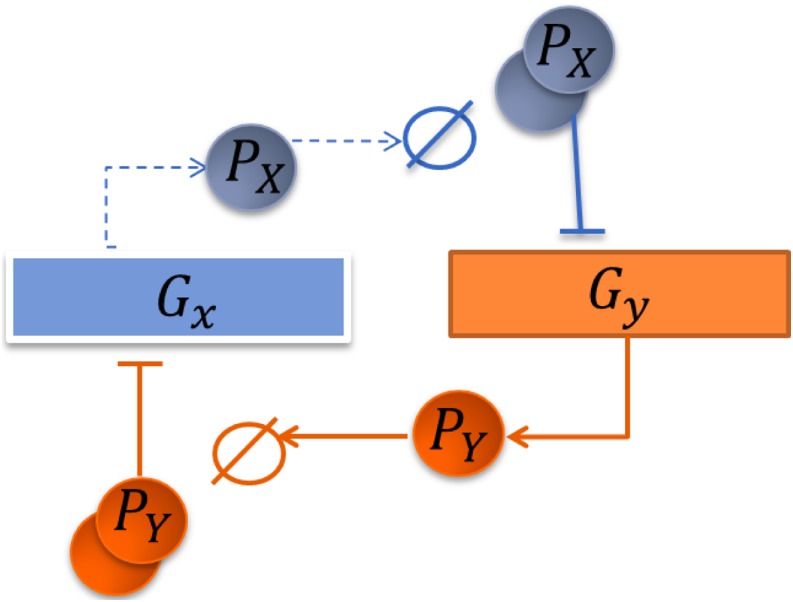

There are six molecular species in our model: genes Gx and Gy, which express proteins PX and PY, as well as protein-DNA complexes and , with protein PY bound on gene Gx and protein PX bound on gene Gy, respectively (Fig. 1). The dimer of protein product PX of gene Gx inhibits the activity of gene Gy, and the dimer of protein product PY of gene Gy inhibits the activity of gene Gx.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the toggle switch genetic network.

The molecular reactions of the network are listed as follows:

| (16) |

The microstate of the system is defined as an ordered quadruplet (X, Y, x, y) of copy numbers of PX, PY, Gx, and Gy, respectively. The copy numbers of bound genes and are denoted as and , respectively. Correspondingly, and , as there is only one copy of each of genes x and y in this system. The binding states of the two operator sites are denoted as “On-On” when x = 1 and y = 1, “On-Off” when x = 1 and y = 0, “Off-On” when x = 0 and y = 1, and “Off-Off” when x = 0 and y = 0.

There are a number of stochastic processes encoded in this network. The synthesis of proteins PX and PY from gene Gx and gene Gy is represented by reactions R1 and R2, respectively, with the rates of sx = sy. The degradation of proteins PX and PY is represented by reactions R3 and R4, respectively, with the rates dx = dy. Reaction R5 represents the binding of two copies of protein PX to the promoter site of Gy to form a protein-DNA complex , with rate by. Reaction R7 represents the unbinding of the complex at a rate of uy. Similarly, reaction R6 represents the binding of two copies of protein PY to the promoter site of Gx to form a protein-DNA complex , with rate bx. Reaction R8 represents the unbinding of the complex at a rate of ux.

Here, we consider the scenario where gene regulation is much slower than protein synthesis and degradation. In eukaryotic cells, epigenetics processes such as histone modification and DNA methylation can reduce the binding rates of transcription factors to their targeting DNA sites. Recent findings in the genetic switch of bacteriophage λ showed that slower binding and unbinding also occur in bacterial cells.72 In the regime of slow binding and unbinding reactions, where by and bx (reactions R5 and R6) and uy and ux (reactions R7 and R8) are smaller than synthesis rates sx and sy (reactions R1 and R2), there are up to four peaks of probability over certain regions of protein copy numbers, in which one of the two genes is expressed and the other gene repressed as well as two genes being either expressed or repressed simultaneously, as reported in Ref. 20.

A well-known phenomenon in genetic switches such as the toggle switch system is the extreme stability of the “On-Off” or the “Off-On” states: it is exceedingly rare for the system to switch from one of these two stable states to the other, even in the presence of perturbations.67,73 In this study, we show that the toggle switch can switch frequently between these two stable states without external perturbations. Furthermore, these switching events can turn the toggle switch into a stochastically oscillating system.

2. Fluxes in the toggle switch network

For the universal discrete flux, we first impose an ascending order on the microstates in the direction of the increasing copies of X. At a fixed value of X, we then order the states in increasing copy number of Y. Subsequently, we order the states in increasing copy number of x and, finally, in the order of increasing copy number of y. Following Eq. (12), the components of the universal discrete stochastic fluxes at the microstate (X, Y, x, y) in the directions of X and Y are

Following Eq. (10), the Liouville flux at the microstate (X, Y, x, y) is

Following Eq. (11), the Fokker-Planck flux for V = 1 at the microstate (X, Y, x, y) is

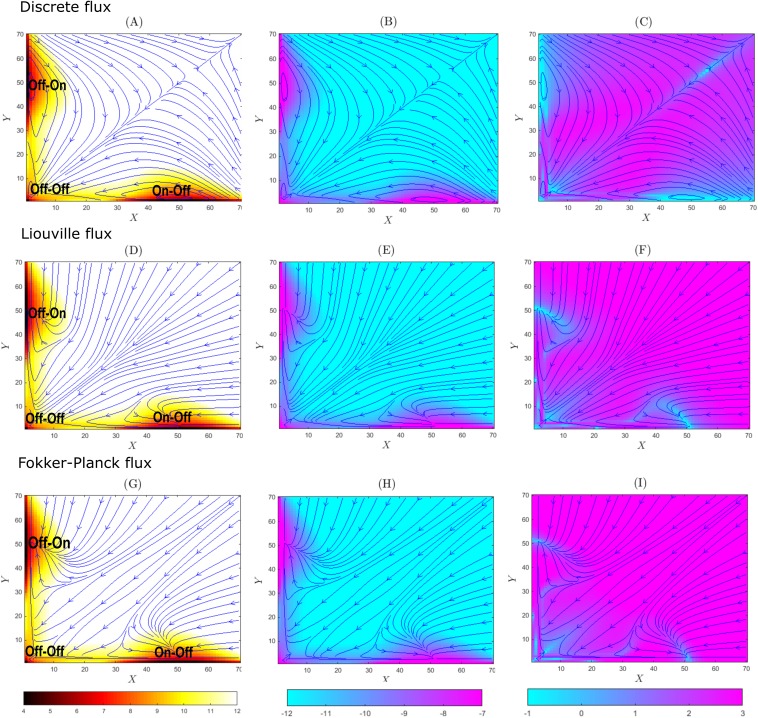

B. Probability flux and velocity in the toggle switch with strong promoter binding

We first consider the system with strong promoter binding. The binding rates are set to bx = by = 1 × 10−2, the synthesis rates sx = sy = 50, the degradation rates dx = dy = 1, and unbinding rates ux = uy = 0.1. At the steady state, there are three probability peaks located at (X, Y) = (0, 0), (50, 0), and (0, 50), corresponding to the states of the genes Gx and Gy of “Off-Off” (x = 0, y = 0), “On-Off” (x = 1, y = 0), and “Off-On” (x = 0, y = 1) [Figs. 2(a), 2(d), and 2(g)].

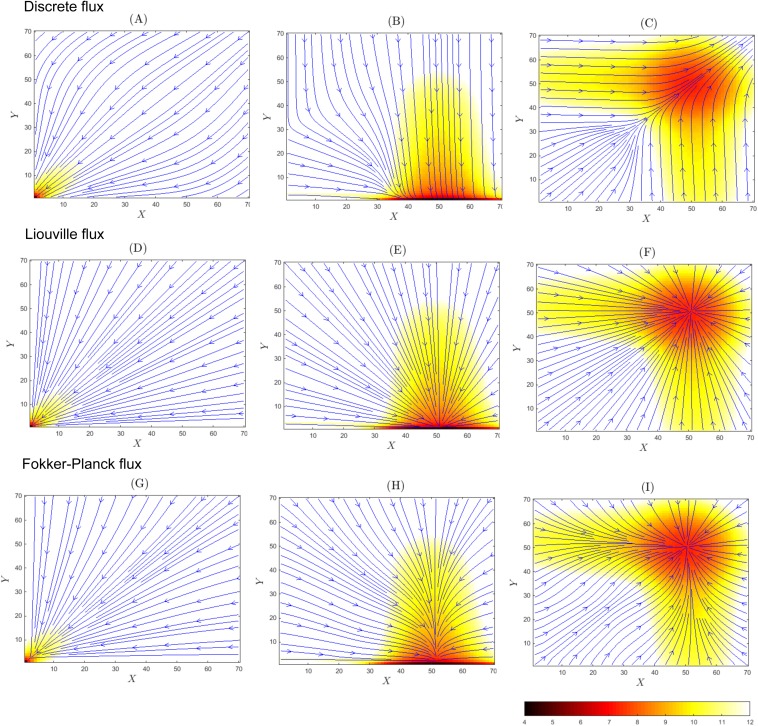

FIG. 2.

The probability surfaces, fluxes, and velocities of the toggle switch system with strong promoter binding (b = 1 × 10−2) at the steady state. Probability value is given by the color scale, and the fluxes/velocities are shown by blue solid lines. The discrete stochastic flux model with probability surface in −log(p(x, y)) (a), flux in log |Js(x, y)| (b), and velocity in log |vs(x, y)| (c); the Liouville flux model with the probability surface in −log(p(x, y)) (d), flux in log |JL(x, y)| (e), and velocity in log |vL(x, y)| (f); and the Fokker-Planck flux model with probability surface in −log(p(x, y)) (g), flux in log |JFP(x, y)| (h), and velocity in log |vFP(x, y)| (i).

The steady state probability distribution of reactions (R1, R3), given x = 1 [Eq. (16)], which are birth-and-death processes, is the Poisson distribution with the maximum at its expected value of X = sX/dX = 50.74 Similarly, the steady state probability distribution for the birth-and-death process of reactions (R2, R4), given y = 1 [Eq. (16)], is the Poisson distribution with the maximum at its expected value of Y = sY/dY = 50. When the binding reaction has a higher propensity than unbinding, the genetic state “On-On” (x = 1, y = 1) disappears. With the multiplication factor of the copy number of molecules, this occurs even when by is an order of magnitude smaller than uy.

From computed p(X, Y, x, y), we show its projection to the plane of (X, Y) in Fig. 2, namely, we show p(X, Y) = p(X, Y, 0, 0) + p(X, Y, 1, 0) + p(X, Y, 0, 1) + p(X, Y, 1, 1). Similarly, Js(X, Y), JL(X, Y), JFP(X, Y), vs(X, Y), vL(X, Y), and vFP(X, Y) are shown as projected in Fig. 2.

The steady-state probability surfaces in −log p(x, t) are shown in Figs. 2(a), 2(d), and 2(g), with high probability regions in red and regions where probability is close to zero in white. The trajectories of the flux field at the steady state are shown in blue for the universal discrete flux field Js(x, t) in Figs. 2(a)–2(c), for the Liouville flux field JL(x, t) in Figs. 2(d)–2(f), and for the Fokker-Planck flux field JFP(x, t) in Figs. 2(g)–2(i). In Figs. 2(b), 2(e), and 2(h), regions with large absolute values of flux are shown in purple and regions with small absolute values of flux are shown in turquoise blue. In Figs. 2(c), 2(f), and 2(i), regions with large absolute values of probability velocity are shown in turquoise blue and regions with small absolute values of velocity are shown in purple.

1. Universal discrete stochastic flux and velocity fields

The heatmaps of the universal discrete probability flux in log |Js(x, t)| and velocity in log |vs(x, t)| [Figs. 2(b) and 2(c), respectively] show that locations with larger flux values also have higher probability. The states “Off-Off,” “On-Off,” and “Off-On” can be regarded as attractors of the probability flux. The flux lines converge to the regions of states near “On-Off” and “Off-On,” after first reaching the state “Off-Off.” Figure 2(c) [log |vs(X, Y)|] shows that the velocity has larger values at locations where the flux trajectories are close to be straight lines [purple regions, Fig. 2(c)] but drops significantly when the trajectories make turns [turquoise regions, Fig. 2(c)].

2. Liouville flux for the toggle switch network

In the Liouville flux, larger values are associated with higher probabilities [Figs. 2(d) and 2(e)]. The states “On-Off” and “Off-On” are the sinks. The flux and velocity lines converge to the states “On-Off” and “Off-On,” after first reaching toward the state “Off-Off.” These patterns are the same as those of the universal discrete flux [Fig. 2(a)]. Detailed examination shows that the flux sinks are located at the states (X = 50, Y = 0) and (X = 0, Y = 50). These are local maxima of the probability surface. The absolute value of the velocity function log |vL(X, Y)| shows that the probability velocity has larger values at locations where the flux trajectories are close to be straight lines [purple regions, Fig. 2(f)] but drops significantly when the trajectories make turns [turquoise regions, Fig. 2(f)].

Liouville flux trajectories and the universal discrete flux trajectories depict overall similar behavior of the system. The flux lines converge to the states “Off-On” and “On-Off” after going through the state “Off-Off,” an intermediate attractor of the flux. However, there are significant differences. The sinks at “Off-On” and “On-Off” are single states of (X = 50, Y = 0) and (X = 0, Y = 50) in the Liouville flux [Fig. 2(f)], but they are regions consisting of states in the discrete flux close to (X = 50, Y = 0) and (X = 0, Y = 50), where the flux trajectories fluctuate [Fig. 2(c)]. The flux trajectories for the Liouville flux start at the source located at (+∞, +∞). This is different from the discrete flux, where the trajectories starting from the states with sufficiently large copy numbers converge to a sink at (+∞, +∞), although these states have very small probability mass.

3. Fokker-Planck flux for the toggle switch network

In the heat map of the Fokker-Planck probability flux, larger values are associated with higher probabilities [Figs. 2(g)–2(i)]. The states “Off-Off,” “On-Off,” and “Off-On” are attractors of the flux. The velocity and flux lines converge to the states “On-Off” and “Off-On,” after first reaching the state “Off-Off.” These are the same as the Liouville flux and similar to the discrete flux [Figs. 2(a) and 2(d)]. Flux sinks are located at the states “On-Off” and “Off-On,” represented by single states (X = 50, Y = 0) and (X = 0, Y = 50) as in the case of Liouville flux. These two states correspond to the maxima of the Poisson distribution of the birth-and-death process [Eq. (16)] of reactions (R1, R3), given x = 1, and (R2, R4), given y = 1, respectively. The absolute value of velocity function log |vL(X, Y)| shows that the velocity has larger values at locations where the flux trajectories are close to be straight lines [purple regions, Fig. 2(i)] but drops significantly when the trajectories make turns [turquoise regions, Fig. 2(i)].

There are significant differences between the Fokker-Planck flux and the discrete stochastic flux. The states “Off-On” and “On-Off” are single states with (X = 50, Y = 0) and (X = 0, Y = 50) in the Fokker-Planck flux [Fig. 2(i)], but they involve sets of the states close to (X = 50, Y = 0) and (X = 0, Y = 50) in the discrete flux [Fig. 2(c)]. The source of the flux for the Fokker-Planck flux is located at (+∞, +∞) at infinity. This is again different from the universal discrete stochastic flux, where a sink is at (+∞, +∞).

The Liouville flux trajectories and the Fokker-Planck trajectories depict similar behavior but with some differences. Starting from the same initial locations, for instance, (X = 70, Y = 40) or (X = 40, Y = 70), the Liouville trajectories first tend to reach the state “Off-Off” and then converge to the states “On-Off” or “Off-On.” In contrast, the Fokker-Planck flux starting from the same states tends to converge to the “Off-On” or the “On-Off” directly.

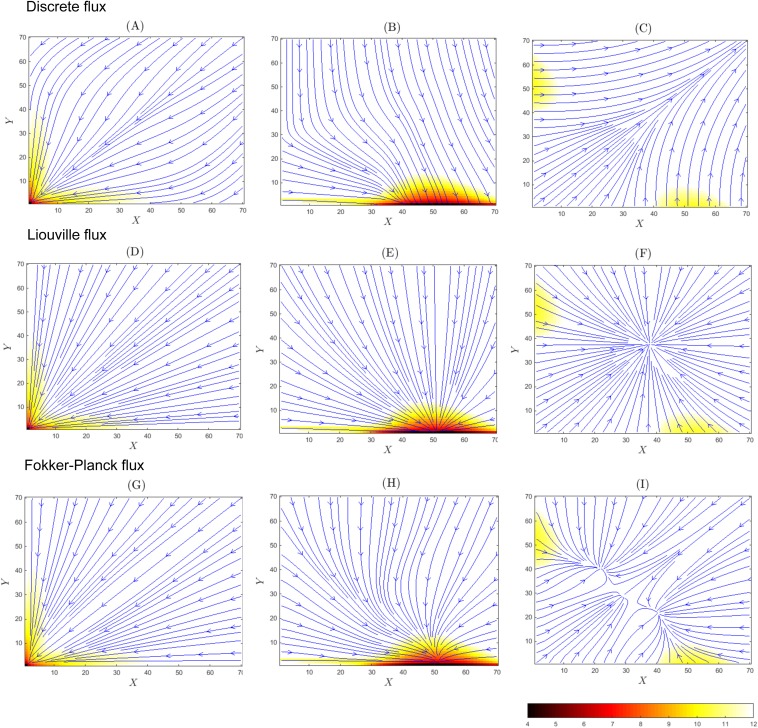

4. Flux in different genetic states

While previous discussions are based on projections in the (X, Y) plane with different genetic states of (x, y) marginalized, we now examined fluxes in each of the specific genetic states of genes x and y, namely, the “Off-Off” state at the gene copy number of (x = 0, y = 0) [Figs. 3(a), 3(d), and 3(g)], the “On-Off” state at (x = 1, y = 0) [Figs. 3(b), 3(e), and 3(h)], and the “On-On” state at (x = 1, y = 1) [Figs. 3(c), 3(f), and 3(i)]. We neglect the case of (x = 0, y = 1) as it is symmetric to that of (x = 1, y = 0).

FIG. 3.

Fluxes of the toggle switch system described at strong promoter binding of b = 1 × 10−2. The “Off-Off” gene state (x = 0, y = 0): (a) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 0, 0) and flux lines of Js(X, Y, 0, 0), (d) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 0, 0) and flux lines of JL(X, Y, 0, 0), and (g) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 0, 0) and flux lines of JFP(X, Y, 0, 0). The “On-Off” gene state (x = 1, y = 0): (b) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 0) and flux lines of Js(X, Y, 1, 0), (e) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 0) and flux lines of JL(X, Y, 1, 0), and (h) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 0) and flux lines of JFP(X, Y, 1, 0). The “On-On” gene state (x = 1, y = 1): (c) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 1) and flux lines for Js(X, Y, 1, 1), (f) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 1) and flux lines for JL(X, Y, 1, 1), and (i) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 1) and flux lines for JFP(X, Y, 1, 1).

At the “Off-Off” state (x = 0, y = 0), we observe the existence of a sink at (X = 0, Y = 0) for all three models of fluxes [Figs. 3(a), 3(d), and 3(g)]. This is expected, as it is the state where both genes are bound, and the probability distribution has a peak. The Fokker-Planck and the Liouville flux trajectories converge to the state (X = 0, Y = 0) [Fig. 3(d)] following straight lines evenly spread out in the X–Y plane, whereas the discrete flux trajectories bend toward the axes of X = 0 and Y = 0.

At the “On-Off” state (x = 1, y = 0), we observe the existence of the flux sink at (X = 50, Y = 0) for the Liouville and Fokker-Planck models [Figs. 3(e) and 3(h)]. The discrete stochastic flux trajectories converge to an area consisting of states near (X = 50, Y = 0) [Fig. 3(b)].

At the “On-On” state, where X ∈ [40, 60] and Y ∈ [40, 60], both genes are unbound and there is overall a small amount of probability mass associated with this genetic state. The three flux models give markedly different results, with sinks located at very different locations. The Liouville flux has the sink at (X = 39, Y = 39) [Fig. 3(f)]. There are three sinks for the Fokker-Planck flux [Fig. 3(i)]. The discrete flux appears to have the sink at (+∞, +∞) [Fig. 3(c)].

It is informative to examine the behavior of the system with high copy numbers of PX and PY in the regime where the law of mass action applies. We can obtain the critical points for each of the four genetic states. For the “On-On” state, we have , . For the “On-Off” state, we have ⟨X⟩ = (sX + uy)/dX ≈ 50, ⟨Y⟩ = 0. For the “Off-On” state, we have ⟨X⟩ = 0, ⟨Y⟩ = (sY + ux)/dY ≈ 50. For the “Off-Off” state, we have ⟨X⟩ = (ux)/dX ≈ 0, ⟨Y⟩ = uy/dY ≈ 0. The eigenvalues for all four critical points are negative, indicating that all four are sinks. At the states “On-On” and “Off-Off,” the eigenvalues are equal and matrices are multiples of the unit matrix and then flux lines form a star.75

These critical points are exactly where the sinks of the Liouville flux are located. The sink (X = 0, Y = 0) at the state “Off-Off” exists for all flux models. The sink at (X = 50, Y = 0)/(X = 0, Y = 50) for the “On-Off”/“Off-On” state exists for the Liouville and Fokker-Planck models. In contrast, the discrete flux lines converge to a broader set of states near the peak (X = 50, Y = 0) [(X = 0, Y = 50)]. For the “On-On” state, the Liouville flux converges to the sink at (X ≈ 37, Y ≈ 37), while there are multiple sinks for the Fokker-Planck flux. The discrete flux does not converge to a single sink.

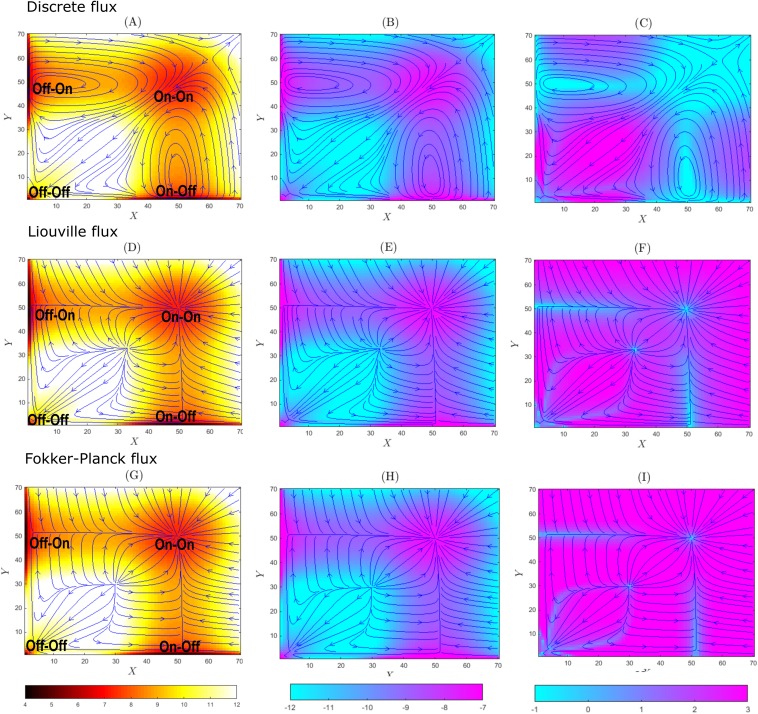

C. Flux and velocity fields in the toggle switch with weak promoter binding from three methods

We now consider the system with weak promoter binding. The binding rates are bx = by = 1 × 10−4, the synthesis rates are sx = sy = 50, the degradation rates are dx = dy = 1, and unbinding rates are ux = uy = 0.1. At the steady state, there are four probability peaks located at (X, Y) = (0, 0), (50, 0), (0, 50), and (50, 50) corresponding to the states of genes Gx and Gy of “Off-Off” (x = 0, y = 0), “On-Off” (x = 1, y = 0), “Off-On” (x = 0, y = 1), and “On-On” (x = 1, y = 1) [Figs. 4(a), 4(d), and 4(g)]. The steady state probability distribution for the birth-and-death process of reactions (R1, R3) of Eq. (16), given x = 1, is the Poisson distribution with the maximum at its expected value of X = sX/dX = 50.74 Similarly, the steady state probability distribution for the birth-and-death process of reactions (R2, R4), given y = 1, is the Poisson distribution with the maximum at its expected value of Y = sY/dY = 50. From computed p(X, Y, x, y), we show p(X, Y), Js(X, Y), JL(X, Y), JFP(X, Y), vs(X, Y), vL(X, Y), and vFP(X, Y) projected on the plane of (X, Y) in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

The probability surfaces, fluxes, and velocities of the toggle switch system with weak promoter binding (b = 1 × 10−4) at the steady state. The probability value is given by the color scale, and the fluxes/velocities are shown by blue solid lines. The discrete stochastic flux model with probability surface in −log(p(x, y)) (a), flux in log |Js(x, y)| (b), and velocity in log |vs(x, y)| (c); the Liouville flux model with probability surface in −log(p(x, y)) (d), flux in log |JL(x, y)| (e), and velocity in log |vL(x, y)| (f); and the Fokker-Planck flux model with probability surface in −log(p(x, y)) (g), flux in log |JFP(x, y)| (h), and velocity in log |vFP(x, y)| (i).

The steady-state probability surface in −log p(x, t) is shown in Figs. 4(a), 4(d), and 4(g), where high probability regions are in red and regions where probability is close to zero in white. The trajectories of the flux field at the steady state are shown in blue for the universal discrete flux field Js(x, t) in Figs. 4(a)–4(c), for the Liouville flux field JL(x, t) in Figs. 4(d)–4(f), and for the Fokker-Planck flux field JFP(x, t) in Figs. 4(g)–4(i). In Figs. 4(b), 4(e), and 4(h), regions with large absolute values of flux are shown in purple and regions with low absolute values of flux are shown in turquoise blue. In Figs. 4(c), 4(f), and 4(i), regions with large absolute values of velocity are shown in turquoise blue. In Figs. 4(c), 4(f), and 4(i), regions with small absolute values of velocity are shown in purple.

1. Universal discrete stochastic flux and velocity fields

The heatmaps of the universal discrete probability flux in log |Js(x, t)| and velocity in log |(x, t)| are shown in Figs. 4(b) and 4(c), respectively. We note that locations with larger flux values also have higher probability. Unlike the previous case of strong promoter binding, we observe the presence of stochastic oscillations around both “On-Off” and “Off-On” states. In addition to the oscillations between the states “Off-On” (“On-Off”) and “On-On,” the system also fluctuates from the state “On-On” to “Off-Off” and then to “Off-On”/“On-Off.” Figure 4(c) [log |vs(X, Y)|] shows that the velocity drops significantly when the trajectories make turns [turquoise regions, Fig. 4(c)].

There are more states with large flux values compared to the condition of strong promoter binding, i.e., there are more purple regions of higher probability mass in Fig. 4(b) than in Fig. 2(b). With more distributed probability mass and the observation of oscillations, the steady state of the toggle switch system with weak promoter binding is overall markedly less stable than that with strong promoter binding.

2. Liouville flux

In the heat map of Liouville flux, larger values are associated with higher probabilities [Figs. 4(d) and 4(e)]. The states “Off-Off,” “On-Off,” “Off-On,” and “On-On” are the attractors of the flux. While the stochastic discrete flux exhibits strong oscillations, Liouville flux trajectories converge to the probability peak at the “On-On” state after traveling through peaks at “On-Off,” “Off-On,” and “Off-Off” states. The source of the flux is at both infinity and the states (X = 35, Y = 35). The sink is located at the states (X = 49, Y = 49). The absolute values of the velocity function log |vL(X, Y)| are larger at locations where the flux trajectories are close to straight lines [purple regions, Fig. 4(f)] but drop significantly when the trajectories make turns [turquoise regions, Fig. 4(f)].

The Liouville flux trajectories and the universal discrete flux trajectories exhibit significantly different behavior. Due to fast unbinding relative to binding at this condition of prominent stochasticity, the toggle switch system constantly alternates between the bounded and unbounded states for genes x and y. However, this phenomenon is not captured by the Liouville flux.

3. Fokker-Planck flux for the toggle switch network

In the heat map of the Fokker-Planck probability flux, larger values are associated with higher probabilities [Figs. 4(g)–4(i)]. The states “Off-Off,” “On-Off,” “Off-On,” and “On-On” are the attractors of the flux. While the stochastic discrete flux exhibits strong oscillations, Fokker-Planck flux trajectories, as the Liouville flux, converge to the probability peak at the “On-On” state after traveling through peaks at “On-Off,” “Off-On,” and “Off-Off” states. The source of the flux is at both infinity and the states (X = 30, Y = 30). The sink is located at the states (X = 50, Y = 50). The absolute value of the velocity function log |vL(X, Y)| is larger at locations where the flux trajectories are close to straight lines [purple regions, Fig. 4(i)] but drop significantly when the trajectories make turns [turquoise regions, Fig. 4(i)].

The Liouville flux trajectories and the Fokker-Planck trajectories depict almost identical behavior of the system. There are some small differences. The sink for the gene state (x = 1, y = 1) for the Liouville flux is at (X = 49, Y = 49), which is different for the sink for the Fokker-Planck flux, which is at (X = 50, Y = 50) [Figs. 4(g)–4(i)]. There are significant differences between the Fokker-Planck flux and the discrete stochastic flux. Whereas the stochastic discrete flux exhibits oscillations, Fokker-Planck flux trajectories converge to the system probability peak at the state “On-On” (X = 50, Y = 50).

4. Flux in different genetic states

We now examined the fluxes in each of the specific genetic states. At the “Off-Off” state (x = 0, y = 0) [Figs. 5(a), 5(d), and 5(g)], we observe the existence of the sink at (X = 0, Y = 0) for all three models of fluxes. This is expected, as it is the state where both genes are bound, and the probability peak is located at (X = 0, Y = 0). The Fokker-Planck and the Liouville flux trajectories converge to this state (X = 0, Y = 0) following straight lines, which are evenly spread off in the X–Y plane, whereas the discrete flux trajectories bend toward the axes of X = 0 and Y = 0.

FIG. 5.

Fluxes of the toggle switch system described at weak promoter binding of b = 1 × 10−4. The “Off-Off” gene state (x = 0, y = 0): (a) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 0, 0) and flux lines of Js(X, Y, 0, 0), (d) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 0, 0) and flux lines of JL(X, Y, 0, 0), and (g) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 0, 0) and flux lines of JFP(X, Y, 0, 0). The “On-Off” gene state (x = 1, y = 0): (b) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 0) and flux lines of Js(X, Y, 1, 0), (e) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 0) and flux lines of JL(X, Y, 1, 0), and (h) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 0) and flux lines of JFP(X, Y, 1, 0). The “On-On” gene state (x = 1, y = 1): (c) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 1) and flux lines for Js(X, Y, 1, 1), (f) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 1) and flux lines for JL(X, Y, 1, 1), (i) heat map of −log p(X, Y, 1, 1) and flux lines for JFP(X, Y, 1, 1).

At the “On-Off” state (x = 1, y = 0) [Figs. 5(b), 5(e), and 5(h)], we observe the existence of a flux sink at (X = 50, Y = 0) for the Liouville and Fokker-Planck models [Figs. 5(d) and 5(e)]. The discrete stochastic flux trajectories converge to an area of states near (X = 50, Y = 0).

At the “On-On” state where both genes are unbound [Figs. 5(c), 5(f), and 5(i)], the three flux models give markedly different results, with sinks at different locations. The Liouville flux has the sink at (X = 50, Y = 50) [Fig. 5(f)], and the Fokker-Planck flux has the sink at (X = 49, Y = 49) [Fig. 5(i)]. The discrete flux appears to have a sink at (+∞, +∞) [Fig. 5(c)].

It is informative to examine the condition of high copy numbers of PX and PY, where the law of mass action applies. We can obtain the critical points for each of the four genetic states. For the state “Off-Off,” we have ⟨X⟩ = ux/dX ≈ 0, ⟨Y⟩ = uy/dY ≈ 0. For the state “On-Off,” we have ⟨X⟩ = (sX + uy)/dX ≈ 50, ⟨Y⟩ = 0. For the state “Off-On,” we have ⟨X⟩ = 0, ⟨Y⟩ = (sY + ux)/dY ≈ 50. For the state “On-On,” we have , . The eigenvalues at all four critical points are negative, indicating that they are sinks. At the states “On-On” and “Off-Off,” the eigenvalues are equal and matrices are multiples of the unit matrix and then flux lines form a star.75

These critical points are where the sinks of Liouville and Fokker-Planck fluxes located. The sink (X = 0, Y = 0) at the state “Off-Off” exists for all flux models. For the “On-Off”/“Off-On” state, the sink at (X = 50, Y = 0)/(X = 0, Y = 50) exists for the Liouville and Fokker-Planck fluxes, while the discrete flux lines converge to a set of the states near (X = 50, Y = 0) [(X = 0, Y = 50)]. For the “On-On” state, the Liouville and Fokker-Planck fluxes converge to (X = 50, Y = 50) and (X = 49, Y = 49), respectively. The discrete stochastic flux does not converge to any sink.

IV. STOCHASTIC FLUCTUATION AND OSCILLATIONS IN THE TOGGLE SWITCH

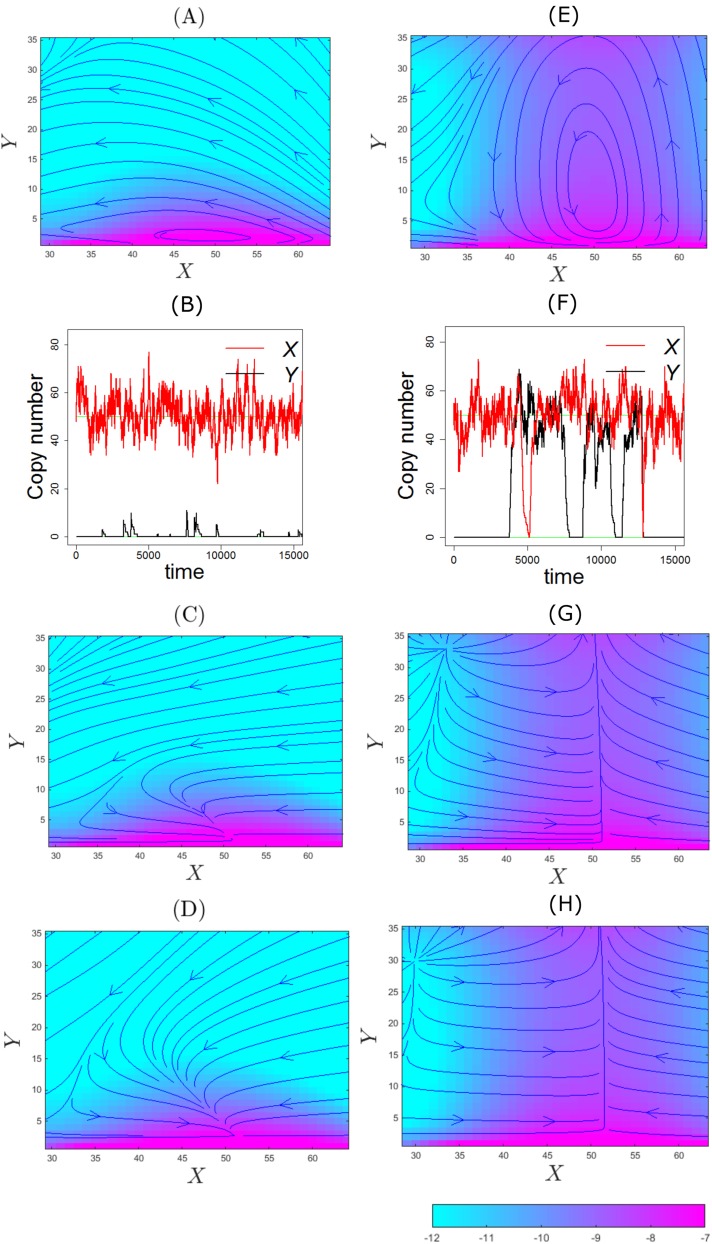

A. Strong promoter binding

With strong promoter binding (b = 1 × 10−2), the three flux models are overall similar but with important differences in details. Discrete flux trajectories exhibit small fluctuations around the “On-Off” peak at (X = 50, Y = 0) [and symmetrically at (X = 0, Y = 50), Fig. 6(a)]. While changes in Y are just a handful copies of the molecule, the amount of molecules of X fluctuates more significantly [Fig. 6(a)].

FIG. 6.

The flow maps of the probability fluxes and trajectories of the toggle switch system near the state “On-Off” with strong promoter binding (b = 1 × 10−2) shown in log |Js(x, y)| (a), log |JL(x, y)| (c), log |JFP(x, y)| (d) and with weak promoter binding (b = 1 × 10−4) shown in log |Js(x, y)| (e), log |JL(x, y)| (g), and log |JFP(x, y)| (h). Sampled Gillespie trajectories starting from the state (X = 50, Y = 0, x = 1, y = 0) are also shown for strong binding (b) and for weak binding (f).

To gain better understanding of the observed fluctuations, we examine reaction trajectories sampled using the SSA algorithm from the initial state of (X = 50, Y = 0, x = 1, y = 0), where the “On-Off” peak is located. Figure 6(b) shows how trajectories of copy numbers of protein PX (red lines) and protein PY (black lines) fluctuate. PX fluctuates around X = 50. This is due to stochasticity in the synthesis and the degradation of PX at the genetic state of x = 1. The trajectories of copy number of protein PY (black lines) also fluctuate around Y = 0 but with overall much smaller magnitude. This is because gene Gy occasionally becomes unbound (X > 0), upon which PY is synthesized. However, since promoter binding is strong and at this condition, PX is in a much larger amount than PY, gene Gy rapidly becomes inhibited by PX again.

The fluctuations observed in reaction trajectories are well explained by the flux lines shown in Fig. 6(a), which form closed, x-axis-oriented horizontal ellipses around the state (X = 50, Y = 0) [Fig. 6(a)]. The major axis of the ellipse corresponds to the stochastic fluctuations with larger magnitude in copies of PX and the minor axis to fluctuations with smaller magnitude in copies of PY.

While the behavior of stochastic fluctuation observed in reaction trajectories is well captured in the flowmap of computed discrete stochastic flux, these fluctuations, however, are not captured by either the Liouville flux [Fig. 6(c)] or the Fokker-Planck flux [Fig. 6(d)], where both converge to a single state (X = 50, Y = 0) [and symmetrically to (X = 0, Y = 50)].

B. Weak promoter binding

With weak promoter binding (b = 1 × 10−4), there are significant differences between the discrete flux and fluxes based on continuum approximations. The discrete flux lines [Fig. 4(a) and enlarged in Fig. 6(a)] exhibit strong oscillations between (X = 50, Y = 50) and (X = 50, Y = 0) and symmetrically between (X = 50, Y = 50) and (X = 0, Y = 50). Furthermore, probability flux also flows from (X = 50, Y = 50) to (X = 0, Y = 0), then to (X = 50, Y = 0), and back to (X = 50, Y = 50). A symmetric oscillatory pattern is also seen, where flux lines flow back to (X = 50, Y = 50) via (X = 0, Y = 0) and (X = 0, Y = 50). In addition, occasionally oscillation can be seen between (X = 50, Y = 0) and (X = 0, Y = 50) via the state of (X = 50, Y = 50).

To gain better understanding of the stochastic oscillations uncovered from the discrete flux model, we examine the reaction trajectories sampled from the initial state of (X = 50, Y = 0, x = 1, y = 0), where the “On-Off” peak is located. Figure 6(f) shows trajectories of copy numbers of protein PX (red lines) and protein PY (black line). PX fluctuates with small magnitude around X = 50. This is due to stochasticity in PX synthesis and degradation at x = 1. This is similar to the fluctuation in PX shown in Fig. 6(b) where promoter binding is fast. PY exhibits similar fluctuation around Y = 50.

However, there is significant oscillation in PY (black line) of larger magnitude between Y = 50 and Y = 0. This is due to stochastic switching between the gene state of y = 1 and y = 0. Similarly, PX (red) also oscillates between X = 50 and X = 0 due to switching between x = 1 and x = 0. Unlike that of strong promoter binding [Fig. 6(b)], the trajectory of PY (black line) exhibits no fluctuations around Y = 0 [Fig. 6(f)]. This is because when gene Gy becomes unbound (y = 1), the system has sufficient time to transit from (Y = 0) to (Y = 50) before gene Gy becomes bound again (y = 0), as promoter binding of PX to Gy is slow. Furthermore, the durations of simultaneous high copies of PX and PY (X = 50, Y = 50) are relatively short.

The oscillations observed in reaction trajectories are well-explained by the flowmap of the discrete flux [Figs. 6(e) and 4(a)]. The closed vertical ellipses with foci at states (X = 50, Y = 0) and (X = 50, Y = 50) correspond to the larger stochastic fluctuations in Y (black line) and smaller magnitude fluctuations in X (red line) [Fig. 6(f)]. Shown in Fig. 4(a) but not in Fig. 6(e) for clarity, the closed horizontal ellipses with foci at states (X = 0, Y = 50) and (X = 50, Y = 50) correspond to the larger stochastic fluctuations in X (red line) and smaller magnitude fluctuations in Y (black line). Furthermore, corresponding to the shorter durations in trajectories when both PX and PY are high at 50 [Fig. 6(f)], the state (X = 50, Y = 50) indeed is a transient state in the flow maps of the discrete flux [Figs. 4(a)–4(c)].

Overall, the behavior of stochastic oscillations and fluctuations observed in reaction trajectories is well captured in the computed discrete stochastic flux. These oscillating behaviors, however, are not captured by either the Liouville flux [Fig. 6(c)] or the Fokker-Planck flux [Fig. 6(d)], where in either case the system converges to a single state of (X = 50, Y = 50).

V. CONCLUSION

In this work, we studied three different models of probability flux, one directly based on the discrete chemical master equation (dCME) and two based on the continuum approximation of the dCME. While continuum probability flux in stochastic models has been mostly based on Fokker-Planck formulations, we introduce here the Liouville flux based on mass-action kinetics. Using the toggle-switch system, we constructed global flow maps of probability flux at the nonequlibrium steady state for all three models.

Under the conditions when the rates of transcription factor to promoter binding are much faster than the unbinding rates, all three flux models show overall similar patterns, but with some important differences: the flux lines of the continuum models flow to single-states for both the “On-Off” and “Off-On” states [Figs. 6(c) and 6(d)], while the flux lines of the discrete model form ellipses [Fig. 6(a)], with better correspondence to the exhibited fluctuations of uneven magnitude in the two proteins as seen in SSA-generated reaction trajectories [Fig. 6(b)]. In the region of large copy numbers of proteins, the flux lines of the discrete model converge to infinity (Figs. 2 and 4), whereas the flux lines of continuum models converge to the sinks at “Off-Off,” “On-Off,” or “Off-On” states. States with large copy numbers have very low probability for the toggle switch system, and the behavior of the system in these states is not representative to the overall system behavior. Furthermore, examination of details of the flow maps at different genetic states reveals significant differences among these three models for the (1, 1) genetic state: the discrete flux flows to infinite, the Liouville flux flows to one sink, and the Fokker-Planck flux flows to three sinks.

Under the highly stochastic condition of slow promoter binding, the differences between the discrete and the continuum flux models are more prominent. The discrete flux model reveals the existence of stochastic oscillations, where flux lines form ellipses, with the “On-On” and “On-Off” states as foci, which are consistent with the SSA-generated reaction trajectories. In contrast, both Fokker-Planck and Liouville fluxes converge to the “On-On” state and do not exhibit oscillatory behavior.

Overall, our results show that fluxes computed with these three different models can exhibit significantly different results. Although the Fokker-Planck flux model and the discrete flux model have been shown to have similar behavior in several well-studied networks, including the Schnakenberg system,24,37 this work reveals that there can be significant differences between them. Using the universal discrete stochastic flux model, we uncovered the strong oscillating behavior of the toggle switch at the nonequilibrium steady state, which is due to strong fluctuations between binding and unbinding events. In contrast, Fokker-Planck and Liouville models fail to capture this phenomenon. Simulated stochastic trajectories fully confirmed the findings obtained using the universal discrete models.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support from Grant Nos. NIH R35 GM127084, NIH R01 CA204962, and NSF-DMS 1759535 is gratefully acknowledged. We thank an anonymous referee for helpful suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maamar H., Raj A., and Dubnau D., Science 317, 526 (2007). 10.1126/science.1140818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao Y., Lu H.-M., and Liang J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 18445 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.1001455107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inui M., Martello G., and Piccolo S., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 252 (2010). 10.1038/nrm2868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.J. E. Ferrell, Jr., Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 140 (2002). 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00314-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Düvel K., Yecies J. L., Menon S., Raman P., Lipovsky A. I., Souza A. L., Triantafellow E., Ma Q., Gorski R., Cleaver S. et al. , Mol. Cell 39, 171 (2010). 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Covert M. W. and Palsson B. Ø., J. Bio. Chem. 277(31), 28058 (2002). 10.1074/jbc.M201691200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Érdi P. and Tóth J., Mathematical Models of Chemical Reactions: Theory and Applications of Deterministic and Stochastic Models (Manchester University Press, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elowitz M. B., Levine A. J., Siggia E. D., and Swain P. S., Science 297, 1183 (2002). 10.1126/science.1070919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swain P. S., Elowitz M. B., and Siggia E. D., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 12795 (2002). 10.1073/pnas.162041399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurtz T. G., Stochastic Processes Appl. 6, 233 (1978). 10.1016/0304-4149(78)90020-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillespie D. T., J. Phys. Chem. 81, 2340 (1977). 10.1021/j100540a008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnakenberg J., Rev. Mod. Phys. 48, 571 (1976). 10.1103/revmodphys.48.571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillespie D. T., Physica A 188, 404 (1992). 10.1016/0378-4371(92)90283-v [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Kampen N. G., Stochastic Processes in Physics and Chemistry (Elsevier, 1992), Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillespie D. T., J. Comput. Phys. 22, 403 (1976). 10.1016/0021-9991(76)90041-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillespie D. T., J. Chem. Phys. 113, 297 (2000). 10.1063/1.481811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.B. J. Daigle, Jr., Roh M. K., Gillespie D. T., and Petzold L. R., J. Chem. Phys. 134, 044110 (2011). 10.1063/1.3522769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao Y. and Liang J., J. Chem. Phys. 139, 025101 (2013). 10.1063/1.4811286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munsky B. and Khammash M., J. Chem. Phys. 124, 044104 (2006). 10.1063/1.2145882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao Y. and Liang J., BMC Syst. Biol. 2, 30 (2008). 10.1186/1752-0509-2-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sidje R. and Vo H., Math. Biosci. 269, 10 (2015). 10.1016/j.mbs.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao Y., Terebus A., and Liang J., Bull. Math. Biol. 78, 617 (2016). 10.1007/s11538-016-0149-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao Y., Terebus A., and Liang J., Multiscale Modeling and Simulation (SIAM, 2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu L., Shi H., Feng H., and Wang J., J. Chem. Phys. 136, 165102 (2012). 10.1063/1.3703514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J., Xu L., and Wang E., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 12271 (2008). 10.1073/pnas.0800579105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan R., Wang X., Ma Y., Yuan B., and Ao P., Phys. Rev. E 87, 062109 (2013). 10.1103/physreve.87.062109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang Y., Yuan R., and Ao P., Phys. Rev. E 89, 062112 (2014). 10.1103/physreve.89.062112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C. and Wang J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 14130 (2014). 10.1073/pnas.1408628111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bianca C. and Lemarchand A., Physica A 438, 1 (2015). 10.1016/j.physa.2015.06.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodwin B. C. et al. , Temporal Organization in Cells: A Dynamic Theory of Cellular Control Processes (Academic Press, New York, 1963). [Google Scholar]

- 31.McAdams H. H. and Arkin A., Trends Genet. 15, 65 (1999). 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01659-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strasser M., Theis F. J., and Marr C., Biophys. J. 102, 19 (2012). 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.11.4000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Margaret J. T., Chu B. K., Roy M., and Read E. L., Biophys. J. 109, 1746 (2015). 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.08.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zia R. and Schmittmann B., J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp. 2007, P07012. 10.1088/1742-5468/2007/07/p07012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li C., Wang E., and Wang J., Biophys. J. 101, 1335 (2011). 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X.-J., Qian H., and Qian M., Phys. Rep. 510, 1 (2012). 10.1016/j.physrep.2011.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terebus A., Liu C., and Liang J., J. Chem. Phys. 149, 185101 (2018). 10.1063/1.5050808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Oliveira L. R., Bazzani A., Giampieri E., and Castellani G. C., J. Chem. Phys. 141, 065102 (2014). 10.1063/1.4891515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J., Xu L., Wang E., and Huang S., Biophys. J. 99, 29 (2010). 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.03.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li C. and Wang J., J. R. Soc., Interface 11, 20140774 (2014). 10.1098/rsif.2014.0774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang Y., Yuan R., Wang G., Zhu X., and Ao P., Sci. Rep. 7, 15762 (2017). 10.1038/s41598-017-15889-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill T. L., Free Energy Transduction and Biochemical Cycle Kinetics (Dover, Mineola, New York, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurtz T., J. Appl. Probab. 8, 344 (1971). 10.1017/s002190020003535x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilkinson D. J., Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 122 (2009). 10.1038/nrg2509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szekely T. and Burrage K., Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 12, 14 (2014). 10.1016/j.csbj.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duncan A., Liao S., Vejchodskỳ T., Erban R., and Grima R., Phys. Rev. E 91, 042111 (2015). 10.1103/physreve.91.042111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grima R., Thomas P., and Straube A. V., J. Chem. Phys. 135, 084103 (2011). 10.1063/1.3625958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanggi P., Grabert H., Talkner P., and Thomas H., Phys. Rev. A 29, 371 (1984). 10.1103/physreva.29.371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ceccato A. and Frezzato D., J. Chem. Phys. 148, 064114 (2018). 10.1063/1.5016158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karlebach G. and Shamir R., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 770 (2008). 10.1038/nrm2503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mou C. Y., Luo J.-l., and Nicolis G., J. Chem. Phys. 84, 7011 (1986). 10.1063/1.450623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmiedl T. and Seifert U., J. Chem. Phys. 126, 044101 (2007). 10.1063/1.2428297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schultz D., Walczak A. M., Onuchic J. N., and Wolynes P. G., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 19165 (2008). 10.1073/pnas.0810366105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bazzani A., Castellani G. C., Giampieri E., Remondini D., and Cooper L. N., J. Chem. Phys. 136, 235102 (2012). 10.1063/1.4725180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McQuarrie D. A., J. Appl. Probab. 4, 413 (1967). 10.2307/3212214 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuwahara H. and Mura I., J. Chem. Phys. 129, 165101 (2008). 10.1063/1.2987701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keener J. and Sneyd J., Biochemical Reactions (Springer, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurtz T. G., J. Chem. Phys. 57, 2976 (1972). 10.1063/1.1678692 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gillespie C. S., IET Syst. Biol. 3, 52 (2009). 10.1049/iet-syb:20070031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smadbeck P. and Kaznessis Y. N., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 14261 (2013). 10.1073/pnas.1306481110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shankar R., Principles of Quantum Mechanics (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu S., Sheng P., and Liu C., Commun. Math. Sci. 12, 779 (2014). 10.4310/CMS.2014.v12.n4.a9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gardner T. S., Cantor C. R., and Collins J. J., Nature 403, 339 (2000). 10.1038/35002131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sekine R., Yamamura M., Ayukawa S., Ishimatsu K., Akama S., Takinoue M., Hagiya M., and Kiga D., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 17969 (2011). 10.1073/pnas.1105901108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu M., Su R.-Q., Li X., Ellis T., Lai Y.-C., and Wang X., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 10610 (2013). 10.1073/pnas.1305423110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Balázsi G., van Oudenaarden A., and Collins J. J., Cell 144, 910 (2011). 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lugagne J.-B., Carrillo S. S., Kirch M., Köhler A., Batt G., and Hersen P., Nat. Commun. 8, 1671 (2017). 10.1038/s41467-017-01498-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim K.-Y. and Wang J., PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, e60 (2007). 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schultz D., Onuchic J. N., and Wolynes P. G., J. Chem. Phys. 126, 245102 (2007). 10.1063/1.2741544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang J., Zhang J., Yuan Z., and Zhou T., BMC Syst. Biol. 1, 50 (2007). 10.1186/1752-0509-1-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Verd B., Crombach A., and Jaeger J., BMC Syst. Biol. 8, 43 (2014). 10.1186/1752-0509-8-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fang X., Liu Q., Bohrer C., Hensel Z., Han W., Wang J., and Xiao J., Nat. Commun. 9, 2787 (2018). 10.1038/s41467-018-05071-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Warren P. B. and ten Wolde P. R., J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 6812 (2005). 10.1021/jp045523y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gardiner C. W. et al. , Handbook of Stochastic Methods (Springer Berlin, 1985), Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jordan D. W. and Smith P., Nonlinear Ordinary Differential Equations: An Introduction to Dynamical Systems (Oxford University Press, USA, 1999), Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]