Abstract

Background:

Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase (INPP5A) has been shown to play a role in the progression of actinic keratosis to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) and the progression of localized disease to metastatic disease. Currently, no cSCC biomarkers are able to risk stratify recurrent and metastatic disease (RMD).

Objective:

To determine the prognostic value of INPP5A expression in cSCC RMD.

Methods:

This was a multi-center, single-institutional, retrospective cohort study within the Mayo Clinic Health System using immunohistochemical staining to examine cSCC INPP5A protein expression in primary tumors and RMD. Dermatologists and dermatopathologists were blinded to outcome.

Results:

Low staining expression (LSE) of INPP5A of RMD was associated with poor overall survival (OS) of 31.0 months vs. 62.0 months for high staining expression (HSE) (p=0.0272). A composite risk score (CRS) (CRS=primary + RMD; with HSE=0 & LSE=1; range 0–2) of 0 was predictive of improved OS compared to a CRS of ≥1 (HR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.21 to 0.84, p=0.0113).

Limitations:

This is a multi-center, but single institution study with a Caucasian population.

Conclusion:

Loss of INPP5A expression predicts poor OS in RMD of cSCC.

Keywords: Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase (INPP5A), Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC), Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Capsule Summary

Recurrent and metastatic disease of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is associated with a poor prognosis. Currently, no biomarkers are able to risk stratify this population.

Low immunohistochemical staining expression of inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase predicts poor overall survival in recurrent and metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.

Introduction:

Non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) is the most common cancer in humans with five million cancers per year in the United States.1 Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common type of NMSC with a 14–20% lifetime risk in the non-Hispanic Caucasian population.2,3 According to recent Medicare data, the incidence of cSCC has doubled from 1992 to 2012 with an equal incidence of cSCC and basal cell carcinoma (BCC).1 The economic burden and incidence of cSCC has increased disproportionally to other cancers.4–6 As such, optimal, cost-effective risk stratification and management is critical.

Unlike BCC, cSCC have higher risks of local recurrence (4.6%), nodal metastasis (3.7%), and of disease-specific death (2.1%).7 Metastatic cSCC has a poor 5-year survival of 25–35% and accounts for up to 8791 deaths annually.8 The most widely used staging systems, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), focus on clinical and histological risk factors of the primary tumor as a predictor of recurrence and metastasis.9–11 There is a paucity of data predicting outcomes of recurrent and metastatic disease (RMD).

Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase (INPP5A), a membrane-associated type I inositol phosphatase, plays a role in the progression of actinic keratosis to cSCC as well as localized disease to metastatic disease in oropharyngeal SCC and cSCC.12–14 Loss of INPP5A expression in cSCC is correlated with aggressive tumor behavior and worse clinical outcomes.14 The prognostic value of INPP5A in RMD is unknown. We hypothesize that loss of INPP5A expression level in RMD will correlate with aggressive disease and predict a poor outcome.

Methods:

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic institutional review board. Cases were identified through our retrospective cSCC database which includes patients from Rochester, Arizona, and Florida. All cases within the database that had a clear delineation of the causal lesion that recurred or metastasized with a minimum of two years follow-up were included in the study. If it was not possible to determine the primary cSCC for the RMD, the case was excluded. All clinical data was obtained through a retrospective chart review. All cases in the database used for this study underwent histological re-review and staging (DJD). The protocol was written for discrepant cases to be reviewed by two dermatopathologists (DJD & SAN) for consensus however, no cases were discrepant. Immunohistochemical staining was used to examine INPP5A protein expression in both primary tumors and RMD (defined as locally recurrent (LR), locally metastatic, and distantly metastatic). First, RMD was analyzed as one group. As a sub-analysis, we analyzed local recurrence and metastasis separately. The metastatic group was composed of in-transit metastasis, nodal metastasis, and distant metastasis. In-transit metastasis was defined as cSCC without an epidermal connection that had spread at least 2cm from the lesion of origin but was not within a lymph node. Locally metastatic disease was defined as in-transit metastases or nodal metastatic disease within the draining lymph node basin. Distant metastatic disease was defined as nodal disease outside the draining node basin or other organ involvement.

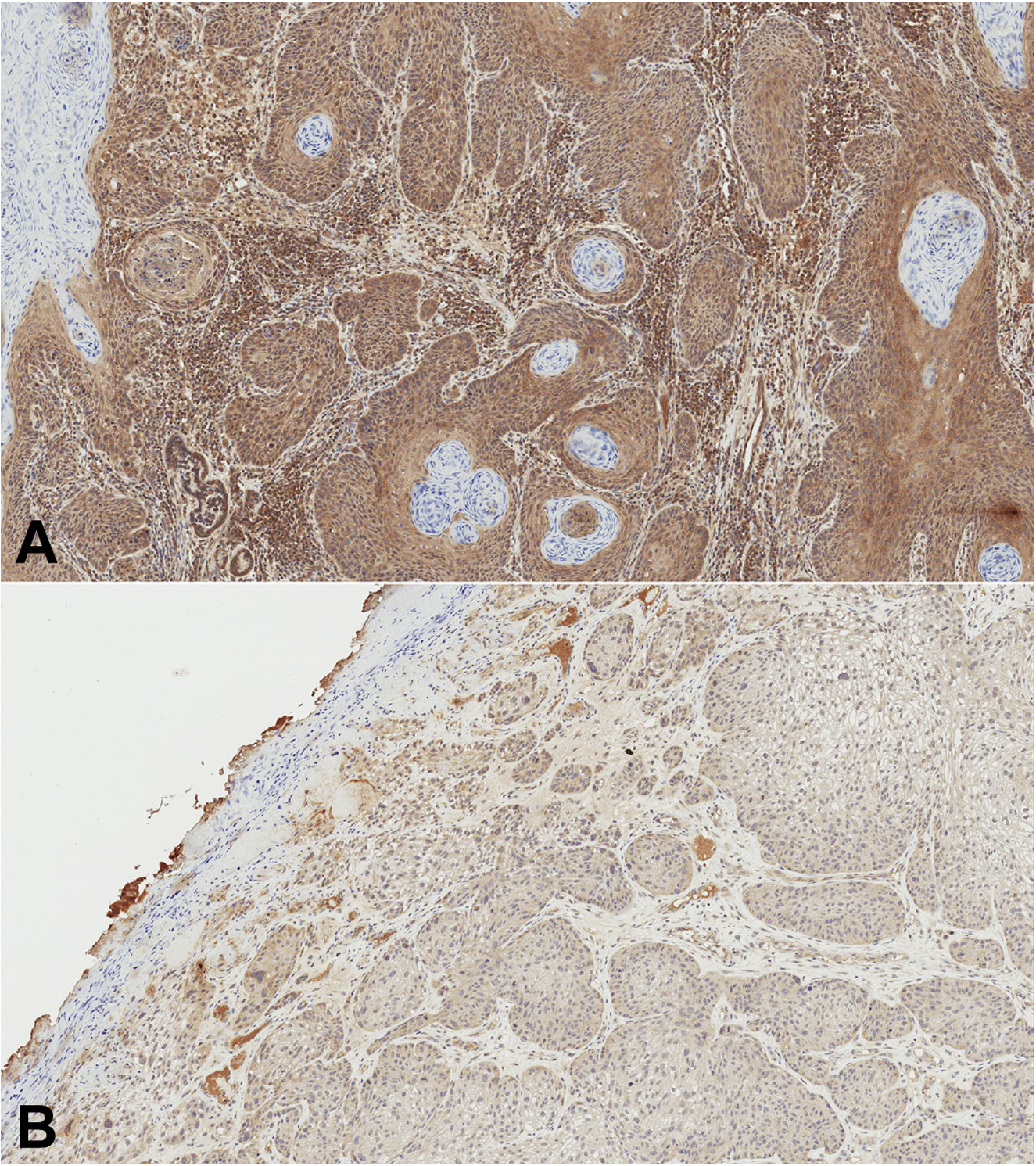

All slides were stained using the technique outlined in our previous study.14 INPP5A protein expression levels were scored on a 4-point scale (0–3) by the consensus diagnosis (ARM & DJD). Both reviewers were blinded to patient outcome. An INPP5A score of 3 was defined as normal expression, a score of 2 was partially diminished, a score of 1 was significantly diminished, and a score of 0 was complete loss. INPP5A staining examples are shown in Fig. 1. High staining expression (HSE) was defined as a score of 2 or 3. Low staining expression (LSE) was defined as a score of 0 or 1. All expression levels were compared with adjacent normal epidermis. A control of normal epidermis was used to gauge the overall strength of the INPP5A signal for each corresponding batch; this was used to adjust for any slight variations in staining batch to batch. If normal epidermis was not available, the control of normal epidermis for the same batch was utilized.

Figure 1.

Examples of the INPP5A stain. (A) cSCC with a grade 3 staining intensity. (B) cSCC with a grade 1 staining intensity.

Overall survival (OS) was compared based upon INPP5A expression at the primary tumor level, change in INPP5A status from primary tumor to events (HSE to LSE, LSE to HSE, unchanged HSE, unchanged LSE), and an INPP5A Composite Risk Score (CRS) (LSE = 1, HSE = 0, score range of 0–2 based upon the summation of primary tumor and the RMD tumor). A CRS of zero indicated both the primary and RMD had HSE, a CRS of one demonstrated either the primary or RMD had LSE, and a CRS of two indicated both the primary and RMD had LSE.

Statistical analysis:

Demographic characteristics and clinical characteristics at the patient and tumor level were summarized and compared between INPP5A groups using Fisher’s exact, Wilcoxon rank sum test, or Kuskal-Wallis test when applicable. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to test if there was a difference between primary tumor INPP5A level and event tumor INPP5A level. The OS was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between INPP5A groups using a log-rank test. Cox regression was used to estimate the hazard ratio for INPP5Agroups. A subgroup analysis of recurrent disease, metastatic disease, and RMD excluding 5 SCC in-situ cases were implemented in a similar manner.

Results:

50 patients with RMD cSCC, 52 tumors, and 64 events (27 local recurrence, 32 local metastasis, and five distant metastasis) were examined. Ten primary tumors had multiple events: eight tumors with two events and two tumors with three events. There were no significant differences in age, gender, race, Fitzpatrick skin type, number of tumors, skin cancer history, number of skin cancer diagnoses when comparing patients with local recurrence and metastasis (Table 1). 14 patients (28.6%) were immunosuppressed: 64.3% were solid organ transplant recipients, 21.4% had chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and 14.3% had iatrogenic immunosuppression secondary to an inflammatory disease. There were significantly more immunosuppressed patients in the metastatic group (33% vs 11.1%, p = 0.0271).

Table 1:

Patient Demographics and Tumor Characteristics

| Patient Demographics (n=50) | |

|---|---|

| Age at Biopsy of cSCC of interest | |

| Mean (SD) | 73.1 (10.5) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 14 (28.0%) |

| Male | 36 (72.0%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 49 (100%) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Fitzpatrick skin type | |

| I | 1 (4.3%) |

| II | 18 (78.3%) |

| III | 4 (17.4%) |

| Missing | 27 |

| Immunosuppressed and History of Skin Cancer | |

| Immunosuppressed | 14 (28.6%) |

| History of Skin Cancer | 45 (90.0%) |

| Reason for Immunosuppression (One or Multiple) | |

| Organ Transplant | 9 (64.3%) |

| Chronic Lymphocytic leukemia | 3 (21.4%) |

| Inflammatory Disease | 2 (14.3%) |

| Tumor Characteristics of Primary Tumors for High and Low INPP5A Expression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brigham and Women’s Hospital T-Staging | ||||

| High INPP5A (n=41) | Low INPP5A (n=11) | Total (n=52) | P-value | |

| T0 | 5 (12.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (9.6%) | |

| T1 | 15 (36.6%) | 2 (18.2%) | 17 (32.7%) | |

| T2a | 13 (31.7%) | 2 (18.2%) | 15 (28.8%) | 0.06451 |

| T2b | 7 (17.1%) | 5 (45.5%) | 12 (23.1%) | |

| T3 | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (18.2%) | 3 (5.8%) | |

| Primary Tumor Diameter (cm) | ||||

| High INPP5A (n=40) | Low INPP5A (n=11) | Total (n=51) | P-value | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.2 (1.9) | 2.5 (2.1) | 2.3 (1.9) | 0.41552 |

| Primary Tumor Depth of Invasion | ||||

| High INPP5A (n=41) | Low INPP5A (n=11) | Total (n=52) | P-value | |

| In Situ | 5 (41.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (27.8%) | |

| Dermis/Subcutaneous Fat | 5 (41.7%) | 3 (50.0%) | 8 (44.4%) | 0.14081 |

| Cartilage/Muscle | 2 (16.7%) | 3 (50.0%) | 5 (27.8%) | |

| Primary Tumor Depth (mm) | ||||

| High INPP5A (n=21) | Low INPP5A (n=9) | Total (n=30) | P-value | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.7 (2.8) | 5.8 (3.1) | 4.3 (3.0) | 0.04152 |

| Primary Tumor Differentiation | ||||

| High INPP5A (n=41) | Low INPP5A (n=11) | Total (n=52) | P-value | |

| Well | 9 (28.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (22.0%) | |

| Moderate | 15 (46.9%) | 3 (33.3%) | 18 (43.9%) | 0.05211 |

| Poor | 8 (25.0%) | 6 (66.7%) | 14(34.1%) | |

| Perineural Invasion | ||||

| High INPP5A (n=41) | Low INPP5A (n=11) | Total (n=52) | P-value | |

| Perineural Invasion | 3 (8.8%) | 4 (44.4%) | 7 (16.3%) | 0.02571 |

| Tumor Characteristics: Local Recurrence, Metastasis, and Both | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brigham and Women’s Hospital T-Staging | |||||

| Local Recurrence (n=20) | Metastasis (n=29) | Both (n=3) | Total (n=52) | P-Value | |

| T0 | 5 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (9.6%) | |

| T1 | 12 (60.0%) | 4 (13.8%) | 1 (33.3%) | 17 (32.7%) | |

| T2a | 1 (5.0%) | 13 (44.8%) | 1 (33.3%) | 15 (28.8%) | 0.00011 |

| T2b | 2 (10.0%) | 9 (31.0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 12 (23.1%) | |

| T3 | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (10.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.8%) | |

| Primary tumor diameter (cm) | |||||

| Local Recurrence (n=19) | Metastasis (n=29) | Both (n=3) | Total (n=51) | P-Value | |

| Mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.5) | 2.7 (2.1) | 2.2 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.9) | 0.00853 |

| Primary Tumor Depth of Invasion | |||||

| Local Recurrence (n=5) | Metastasis (n=12) | Both (n=l) | Total (n=18) | ||

| In Situ | 5 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (27.8%) | |

| Dermis / Subcutaneous Fat | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (58.3%) | 1 (100.0%) | 8 (44.4%) | |

| Cartilage / Muscle | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (41.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (27.8%) | |

| Primary Tumor Depth (mm) | |||||

| Local Recurrence (n=2) | Metastasis (n=26) | Both (n=2) | Total (n=30) | P-Value | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.6) | 4.4 (3.1) | 5.4 (4.0) | 4.3 (3.0) | 0.70903 |

| Primary Tumor Differentiation | |||||

| Local Recurrence (n=10) | Metastasis (n=29) | Both (n=2) | Total (n=41) | P-Value | |

| Well | 8 (80.0%) | 1 (3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (22.0%) | |

| Moderate | 0 (0.0%) | 17 (58.6%) | 1 (50.0%) | 18 (43.9%) | <0.00011 |

| Poor | 2 (20.0%) | 11 (37.9%) | 1 (50.0%) | 14 (34.1%) | |

| Perineural Invasion | |||||

| Local Recurrence (n=17) | Metastasis (n=24) | Both (n=2) | Total (n=43) | P-Value | |

| Perineural Invasion | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (29.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (16.3%) | 0.06221 |

Fisher’s Exact,

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum,

Kruskal Wallis,

INPP5A: inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase

The primary tumors were comprised of 9.6% BWH T0, 32.7% BWH T1, 28.8% BWH T2a, 23.1% BWH T2b, and 5.8% BWH T3 (Table 1). We compared the INPP5A expression of the primary tumors and RMD event tumors. 41/52 (78.8%) of primary tumors had HSE and 11/52 (21.2%) had LSE. 36/52 (69.2%) of RMD had HSE and 16/52 (30.8%) had LSE. Primary tumors with LSE had greater depth (5.8mm vs 3.7mm, p=0.0415) and higher rates of perineural invasion (44% vs 9%, p=0.0257), but were not significantly different by BWH staging (p = 0.0645) or differentiation (p = 0.0521) (Table 1).

Patients with RMD disease had only metastatic tumors in 55.8% of cases, LR tumors in 38.5% of cases, and both metastatic and LR disease in 5.8% of cases. All three groups of RMD (local recurrence, metastasis, and both) differed significantly in BWH staging, primary tumor diameter, depth of invasion, tumor differentiation, and perineural invasion (Table 1). When comparing CRS 0, 1, and 2 for RMD tumors, there were significant differences in primary tumor depth of invasion (p = 0.0372) and primary tumor differentiation (p = 0.0102). After excluding 5 SCC in-situ patients, depth of invasion and tumor differentiation were no longer different between RMD risk factor groups (p = 0.25 and p = 0.20, respectively).

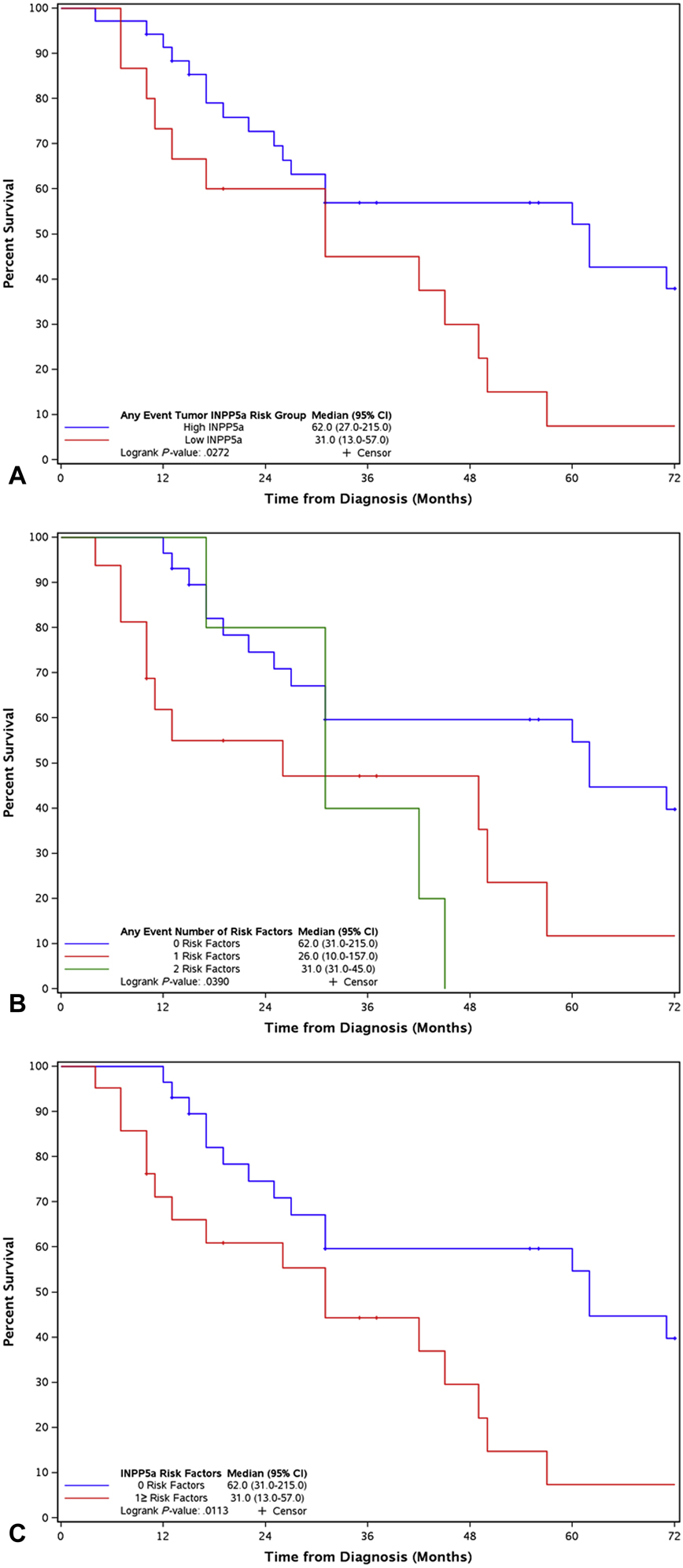

OS of RMD was not affected by INPP5A level of the primary tumor (31.0 months LSE vs 57.0 months HSE, p = 0.0897). However, INPP5A level of the RMD event tumor was predictive of OS (31.0 months LSE vs 62.0 months HSE, p = 0.0272, Fig. 2a). OS was not different between INPP5A group transitions (HSE to LSE group, 31.0 months, 20% of cases; LSE to HSE group, 26.0 months, 12% of cases; unchanged HSE group, 62.0 months, 58% of cases; and unchanged LSE group, 10% of cases, 31.0 months, p = 0.0899). The CRS of INPP5A was predictive of OS (risk score = 0, 62.0 months; risk score = 1, 26.0 months; and risk score = 2, 31.0 months, p = 0.039, Fig. 2b). OS comparing CRS of zero versus CRS ≥ 1 was significantly different (risk score = 0, 62.0 months; risk score = 1 or more, 31.0 months, p = 0.0113, Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Recurrent and metastatic disease overall survival by (A) any event tumor INPP5A levels, (B) INPP5A composite risk score (LSE = 1, HSE = 0, score range of 0–2 based upon the summation of primary and RMD score), (C) INPP5A composite risk score grouping of zero risk factors vs. one or more risk factors.

Due to the difference in tumor characteristics amongst the CRS of 0–2, a sub-analysis excluding the five SCC in-situ cases was performed. OS of INPP5A levels of the primary tumor and CRS of 0–2 was non-significant. However, the OS of CRS risk score of zero versus CRS ≥ 1 remained significant (CRS=0 62.0 months vs CRS ≥ 1 31.0 months, p = 0.0325).

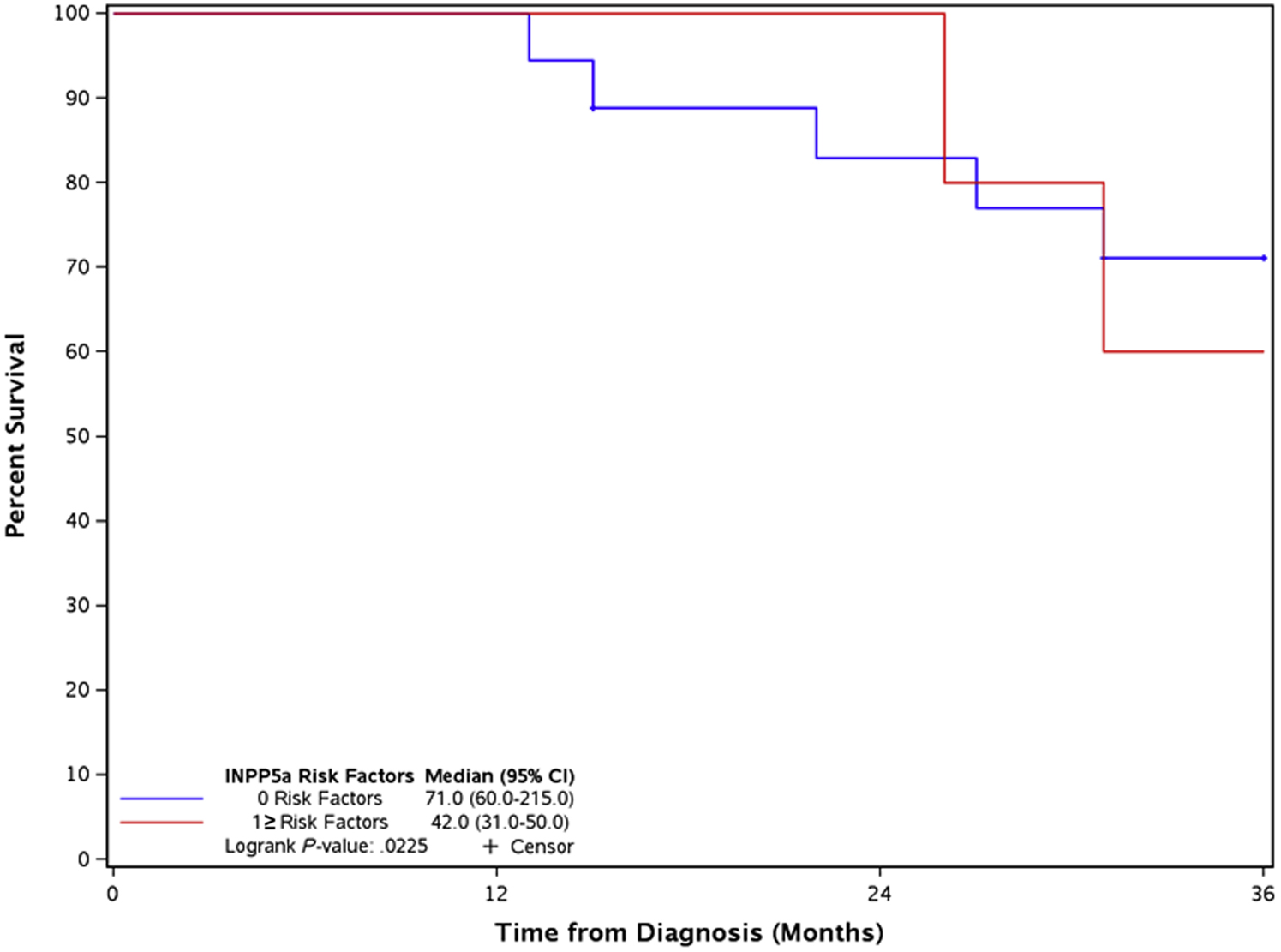

A subgroup analysis of LR and metastatic disease was performed. For LR, patient demographics and tumor characteristics across all analysis were non-significant except for immunosuppression, which was more common in those with a CRS ≥ 1 (p = 0.0005). In LR disease, LSE of INPP5A at the primary tumor level was associated with a worse OS (HSE 71.0 months and LSE 31.0 months, p = 0.0296). INPP5A expression at the event level of LR was non-significant (HSE 71.0 months and LSE 45.5 months, p = 0.0884). A CRS ≥ 1 was associated with a poor OS (CRS = 0 median survival 71.0 months vs CRS ≥ 1 median survival 42.0 months, p = 0.0225) (Fig. 3). LSE of INPP5A at the primary tumor, event tumor level or CRS ≥ 1 of metastatic disease was not associated with a worse OS.

Figure 3.

Local recurrence overall survival comparing composite risk factor grouping of zero vs. one or more risk factors.

Discussion:

We found that LSE of INPP5A of RMD was associated with poor OS (median survival 31.0 months LSE vs. 62.0 months HSE, p = 0.0272) and HSE of INPP5A in the primary and RMD (CRS of 0) was predictive of improved OS (HR = 0.42, 95% CI: 0.21 to 0.84, p=0.0113). The OS of high-risk RMD by INPP5A staining (26% & 31% at 2 years) and CRS ≥ 1 (31% at 2 years), was similar to prior studies with lymph node metastasis, in which OS ranged from 33% at 2 years to 46.7% at 3 years, and recurrent head and neck cSCC, in which the OS at 1-year was 43.2%.15–17 Once verified, INPP5A expression at the primary tumor and nodal level may be used to risk stratify individuals both for and with RMD. Furthermore, risk stratification may be possible in cases of RMD without primary tissue and in tumors of unknown primary.

Prior studies have identified tumor size, differentiation, depth, and location as risk factors for the development of RMD.7,8,10,18,19 LSE of INPP5A at the primary tumor is predictive of more aggressive behavior, HR of 2.71 for OS and an HR of 4.71 for local/regional metastasis.14 Tumors in our cohort with LSE had higher rates of perineural invasion (44% vs 9%, p=0.0257) and greater depth (5.8mm vs 3.7mm, p=0.0415), but no difference by BWH stages or differentiation. These findings are similar to our prior work which found an association of LSE and perineural invasion, poor differentiation, tumor size greater than 2cm, and invasion beyond the fat.14 The cohort in this study was smaller and all tumors were high risk with RMD and similar risk factors.

We examined INPP5A expression of primary tumors, RMD, and created a CRS. LSE of the RMD and a CRS ≥ 1 were noted of being associated with poor OS. However, there were significant differences between tumor groups with more aggressive tumors in both groups. These differences were thought to be secondary to 5 SCCIS in the study. Therefore, we excluded the 5 cases of SCC in-situ, and the differences between groups were non-significant. Re-analysis without the SCCIS found a trend with LSE score at the primary tumor or RMD and decreased OS (p=0.089) and a decreased OS in those with a CRS ≥ 1 (CRS=0 62.0 months vs CRS ≥ 1 31.0 months, p = 0.0325). Therefore, we believe that a CRS ≥ 1 is a potential marker of poor outcome independent of BWH T-stage. Larger studies are needed to verify these findings.

We performed a sub-analysis of LR and metastatic tumors. LSE in primary tumors with LR was associated with poor OS (median survival 31.0 months LSE vs 71.0 months HSE, p=0.0296). Interestingly, there was only a trend for LSE of the LR event tumor (p = 0.0884). This difference is likely due to a lack of power. A CRS ≥ 1 in LR tumors was predictive of poor OS (HR = 3.88, 95% CI: 1.10 – 13.69, p=0.0225). Importantly, there were no differences in tumor characteristics suggesting that CRS may be useful in risk stratification independent of BWH T-stage. Subgroup analysis of the demographics of LR cSCC by CRS found a higher rate of immunosuppression in the CRS≥ 1. Immunosuppressed patients have worse OS which may account for the findings in the LR CRS≥ 1 group.20 INPP5A expression and CRS were not able to risk-stratify metastatic tumors for OS. The metastatic cohort was advanced at initial diagnosis, had a worse OS at baseline, and therefore would require a larger number of cases to risk stratify. 86.2% of primary tumors that went on to have metastatic disease were T2a or above versus 15% of tumors for recurrent disease. Further studies with larger cohorts of metastatic disease need to be conducted.

This study had several limitations. This was a single institution study with a Caucasian population. Our study was underpowered to detect differences in outcome of INPP5A at the primary tumor level for all RMD and disease-specific death. Additionally, the metastatic cohort was significantly more stage advanced than the recurrent cohort.

In conclusion, loss of INPP5A expression predicts poor OS in RMD of cSCC. INPP5A CRS of 0 is associated with a superior OS of locally recurrent cSCC. Our study demonstrates the potential for INPP5A expression level to be used as an adjunct tumor marker for clinical management and risk stratification of locally RMD disease in cSCC. An additional study with a larger cohort is justified in order to determine if INPP5A expression may serve as a biomarker to stratify OS in individuals with metastatic disease.

Funding:

Dermatology Foundation - Career Development Award & NIH Grant 5R01CA179157

Abbreviations and acronyms:

- NMSC

Non-melanoma skin cancer

- cSCC

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

- BCC

Basal cell carcinoma

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- BWH

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

- RMD

Recurrent and metastatic disease

- INPP5A

Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase

- LR

Local recurrence

- HSE

High staining expression

- LSE

Low staining expression

- OS

Overall survival

- CRS

Composite risk score

- HR

Hazard ratio

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest and no financial disclosure

Data presented at the 2019 Society for Investigative Dermatology Meeting.

References:

- 1.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, Coldiron BM. Incidence Estimate of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer (Keratinocyte Carcinomas) in the U.S. Population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(10):1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potenza C, Bernardini N, Balduzzi V, Losco L, Mambrin A, Marchesiello A, et al. A Review of the Literature of Surgical and Nonsurgical Treatments of Invasive Squamous Cells Carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9489163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Housman TS, Feldman SR, Williford PM, Fleischer AB Jr., Goldman ND, Acostamadiedo JM, et al. Skin cancer is among the most costly of all cancers to treat for the Medicare population. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2003;48(3):425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, Tollefson MM, Otley CC, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. Jama. 2005;294(6):681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muzic JG, Schmitt AR, Wright AC, Alniemi DT, Zubair AS, Olazagasti Lourido JM, et al. Incidence and Trends of Basal Cell Carcinoma and Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Population-Based Study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000 to 2010. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(6):890–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmults CD, Karia PS, Carter JB, Han J, Qureshi AA. Factors predictive of recurrence and death from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a 10-year, single-institution cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(5):541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013;68(6):957–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edge S, Byrd D, Compton C, Fritz A, Greene F, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7 ed. New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karia PS, Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Harrington DP, Murphy GF, Qureshi AA, Schmults CD. Evaluation of American Joint Committee on Cancer, International Union Against Cancer, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital tumor staging for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(4):327–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Review of the Eighth Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Guidelines, Prognostic Factors, and Histopathologic Variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24(4):171–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sekulic A, Kim SY, Hostetter G, Savage S, Einspahr JG, Prasad A, et al. Loss of inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase is an early event in development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer prevention research. 2010;3(10):1277–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel AB, Mangold AR, Costello CM, Nagel TH, Smith ML, Hayden RE, et al. Frequent loss of inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(1):e36–e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cumksy HJ, Costello CM, Zhang N, Butterfield R, Buras M, Schmidt J, et al. The Prognostic Value of Inositol Polyphosphate 5-Phosphatase in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore BA, Weber RS, Prieto V, El-Naggar A, Holsinger FC, Zhou X, et al. Lymph node metastases from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(9):1561–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraus DH, Carew JF, Harrison LB. Regional lymph node metastasis from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124(5):582–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun L, Chin RI, Gastman B, Thorstad W, Yom SS, Reddy CA, et al. Association of Disease Recurrence With Survival Outcomes in Patients With Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck Treated With Multimodality Therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wermker K, Kluwig J, Schipmann S, Klein M, Schulze HJ, Hallermann C. Prediction score for lymph node metastasis from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the external ear. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(1):128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullen JT, Feng L, Xing Y, Mansfield PF, Gershenwald JE, Lee JE, et al. Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: defining a high-risk group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(7):902–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson AK, Kelley BF, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Baum CL. Risk Factors for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Recurrence, Metastasis, and Disease-Specific Death: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(4):419–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]