Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common chronic metabolic disorder with an increasing prevalence worldwide. According to a previous study, physicians' treatment patterns or patients' behaviors change when they become aware of the risk for cardiovascular (CV) disease in patients with DM. However, there exist controversial reports from previous studies in the impact of physicians' behaviors on the patients' quality of life (QoL) improvements. So we investigate the changes in QoL according to physicians and patients' behavioral changes after the awareness of CV risks in patients with type 2 DM.

Methods

Data were obtained from a prospective, observational study where 799 patients aged ≥40 years with type 2 DM were recruited at 24 tertiary hospitals in Korea. Changes in physicians' behaviors were defined as changes in the dose/type of antihypertensive, lipid-lowering, and anti-platelet therapies within 6-month after the awareness of CV risks in patients. Changes in patients' behaviors were based on lifestyle modifications. Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life comprising 19-life-domains was used.

Results

The weighted impact score change for local or long-distance journey (P=0.0049), holidays (P=0.0364), and physical health (P=0.0451) domains significantly differed between the two groups; patients whose physician's behaviors changed showed greater improvement than those whose physician's behaviors did not change.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that changes in physicians' behaviors, as a result of perceiving CV risks, improve QoL in some domains of life in DM patients. Physicians should recognize the importance of understanding CV risks and implement appropriate management.

Keywords: Cardiovascular diseases, Diabetes mellitus, Risk management, Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common chronic metabolic disorder, with an increasing prevalence worldwide [1]. According to the World Health Organization, the number of patients with DM increased from 108 million (4.7%) in 1980 to 420 million (8.5%) in 2014 [2] and the pool of patients with DM in 2030 is predicted to double than that in 2000 [3]. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) reports that the prevalence of DM in 2017 is 8.8% worldwide and 6.8% in South Korea after adjusting for age, sex, and ethnicity [4].

Patients with DM reported a markedly low health-related quality of life (QoL) [5], and diabetic complications further undermine their QoL [6]. Particularly, the onset of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), such as angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, stroke, and atherosclerosis, are intimately associated with DM [7]. In addition, DM patients with CVD show a greater reduction in QoL than those without CVD [8]. Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3), which is an indicator of QoL, is approximately 10% lower in patients with DM who experienced stroke than those who did not [9], and mortality caused by these CVDs accounts for 80% of the total mortality in patients with DM [10].

To prevent CVD in patients with DM, the American Diabetes Association and IDF recommend lifestyle modifications (e.g., diet, exercise) or medication care (e.g., blood pressure [BP] and lipid control) [11,12]. In addition, the Screening for Heart Attack Prevention and Education guideline provided by the Association for Eradication of Heart Attack recommends classifying patients with a high risk for CVD using an atherosclerosis test [13]. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Risk Engine score [14] can also be computed to detect the risk for CVD.

To prevent CVD in patients with DM, the American Diabetes Association and IDF recommend lifestyle modifications (e.g., diet, exercise) or medication care (e.g., blood pressure [BP] and lipid control) [11,12]. In addition, the Screening for Heart Attack Prevention and Education guideline provided by the Association for Eradication of Heart Attack recommends classifying patients with a high risk for CVD using an atherosclerosis test [13]. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Risk Engine score [14] can also be computed to detect the risk for CVD.

According to a previous study, physicians' treatment patterns or patients' behaviors change when they become aware of the risk for CVD in patients with DM [15]. However, there exist controversial reports from previous studies in the impact of physicians' behaviors on the patients' QoL improvements. In the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, patients with DM under strict BP control showed a lower QoL than those under less strict control [16]. On the other hand, a study reported that the QoL can be improved by instilling a belief that the health status of DM patients can be managed by physicians [17].

To provide further information, we investigated the change in QoL, using the Korean version of the Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life (K-ADDQoL), according to the physicians' behavior change after becoming awareness of cardiovascular (CV) risks in patients with type 2 DM. Also, we explored the change in QoL by the patients' lifestyle modification.

METHODS

Study design and data collection

This study was part of improving the QoL in the CV risk factors management in asymptomatic diabetic subjects outcomes research (CV risk in DM Outcomes Research), which was a prospective, observational study conducted in 24 tertiary hospitals in Korea [15]. The study included patients who were with type 2 DM, aged ≥40, and taken first ever carotid artery ultrasound (CUS) but excluded patients who had previously undergone CUS, who had a history of coronary artery disease, symptomatic congestive heart failure, coronary revascularization, cerebrovascular disease, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or documented peripheral vascular disease (e.g., peripheral artery disease, abdominal aneurysm, or carotid artery stenosis), or who were participating in any interventional studies. Calculation of sample size on basis of statistics is not required since this study was an observational study to describe further on the patients without any hypothesis. Based on the origin of this study, all of the participating investigators made a consensus that 40 patients for 3 months considering the inclusion/exclusion criteria, from each participating hospitals are sufficient to be representative to the target population and thus finally recruited 799 patients.

Prior to the patient enrollment, the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating institution of the study (IRB No. 09-104, Hallym University Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital). Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Physician and patient behavior

Physicians' and patients' behavioral changes were observed after they became aware of the patients' CV risks through CUS. Changes in physicians' behaviors were observed based on changes of treatment pattern (antihypertensive, lipid-lowering, and anti-platelet therapy). Changes in physician behaviors were defined as any changes in the dose (including increasing or decreasing) or class of prescribed drugs (including adding on or reducing drug classes of antihypertensive, lipid lowering, and anti-platelet therapy) within the 6-month period.

We defined the changes in patient behaviors based on lifestyle modification (smoking, drinking, exercise, stress, nutrition management, and drug compliance). Smoking, drinking, exercise, and stress were measured using the corresponding items on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) [18], and nutritional management was assessed based on the Customized Visiting Health Management Project Needs Survey by the Ministry of Health and Welfare [19]. Drug compliance was measured using the Korean-translated self-reported questionnaire developed by Morisky et al. [20]. Changes in patients' behaviors were defined as any positive changes in smoking, drinking, exercise, stress, nutritional management, or drug compliance scores within the 6-month period.

K-ADDQoL

The validated K-ADDQoL, a specialized instrument for patients with DM, was used to ensure high reliability [21]. The ADDQoL is widely used to measure QoL of patients with DM, because of its higher sensitivity than other general QoL measures [22].

The ADDQoL begins with two global questions. The first global question, ‘In general, my present quality of life is,’ aims to provide a possible single-item indicator of QoL by assessing the participants' present global QoL. The second global question, ‘If I did not have diabetes, my quality of life would be,’ is a diabetes-specific item that aims to assess the diabetes-dependent global QoL.

The subsequent 19 domain-specific items ask the participants to rate how particular aspects of their lives would be if they did not have DM. For each of these items, participants provide the impact (range, −3 [greatest negative impact] through 0 [no impact] to +1 [positive impact]) and importance (range, 0 [not at all important] to 3 [very important]) scores. Weighted impact (WI) is calculated by multiplying importance and impact ratings, ranging from −9 (negative impact) to +9 (positive impact). The products of these two ratings for each domain are summed and then divided by the number of applicable domains to produce the average weighted impact (AWI) score.

The AWI is the mean WI for each of the 19 domains, ranging from −9 to +9. A lower AWI (closer to −9) reflects that DM has a more negative impact on the patient's life, whereas a higher AWI (closer to +9) reflects that DM has a less negative impact on the patient's life (Supplementary Table 1) [23].

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were presented as mean±standard deviation, and categorical data were presented as frequency and percentage. K-ADDQoL results were shown with the mean of impact, importance, and WI for each 19-domain and AWI. We compared the changes of WI and AWI in the 6-month period using paired t-tests. Changes in WI in relation to physician and patient behaviors were compared using t-tests.

To identify the factors affecting AWI, we performed a univariate analysis with the participants' demographic and clinical haracteristics. Student's t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for categorical variables, and correlation analysis was performed for continuous variables. Significant variables in the univariate analysis (P>0.1) and clinically meaningful variables were included in a multivariate linear regression. Statistical significance was considered when the two-tailed P value less than 5%. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 799 patients with type 2 DM were enrolled in this study. The mean age was 60.17 years, and 49.56% of the participants were women. The mean duration of DM was 8.12 years and a total of 74.34% of patients had comorbidities. At baseline, the mean fasting glucose level was 145.78 mg/dL and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was 7.64%. Mean of BP and laboratory figures were within normal level both at baseline and follow-up and not much differed in subgroups. After perceiving CV risks, 43.2% of physicians changed their behaviors, and 88.7% patients altered their own lifestyles (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

| Characteristic | Total (n=799) | Change in physician's behaviora | Change in patient's behavior | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=294) | No (n=387) | Yes (n=708) | No (n=90) | |||||||

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | |

| Ageb, yr | 60.17±9.51 | - | 62.05±9.50 | - | 59.77±9.19 | - | 60.43±9.43 | - | 57.88±9.78 | - |

| Female sex | 396 (49.56) | - | 152 (51.70) | - | 190 (49.10) | - | 348 (49.15) | - | 48 (53.33) | - |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.13±3.20 | 25.17±3.08 | 25.30±3.25 | 25.35±3.20 | 25.22±3.17 | 25.17±3.06 | 25.15±3.22 | 25.19±3.09 | 24.98±2.94 | 24.93±3.03 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 87.16±8.19 | 86.91±8.30 | 87.51±8.49 | 86.90±8.62 | 87.20±8.05 | 87.20±8.20 | 87.26±8.22 | 86.96±8.30 | 86.31±7.79 | 86.53±8.38 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 125.38±14.51 | 125.99±13.96 | 127.33±14.40 | 126.59±13.88 | 124.02±14.13 | 125.18±14.25 | 125.79±14.46 | 126.37±13.98 | 122.48±14.42 | 122.82±13.49 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 75.36±10.09 | 75.63±9.53 | 75.91±10.49 | 75.44±9.49 | 74.57±9.63 | 75.28±9.45 | 75.41±9.89 | 75.87±9.34 | 75.01±11.59 | 73.93±10.83 |

| DM duration, yr | 8.12±7.12 | - | 8.66±7.11 | - | 8.20±7.18 | - | 8.31±7.10 | - | 6.67±7.11 | - |

| <5 | 294 (37.98) | - | 99 (33.90) | - | 138 (37.50) | - | 253 (36.77) | - | 40 (47.06) | - |

| 5–9 | 190 (24.55) | - | 68 (23.29) | - | 95 (25.82) | - | 168 (24.42) | - | 22 (25.88) | - |

| 10–14 | 157 (20.28) | - | 70 (23.97) | - | 74 (20.11) | - | 145 (21.08) | - | 12 (14.12) | - |

| ≥14 | 133 (17.18) | - | 55 (18.84) | - | 61 (16.58) | - | 122 (17.73) | - | 11 (12.94) | - |

| Comorbidityb | ||||||||||

| Yes | 594 (74.34) | - | 234 (79.59) | - | 303 (78.29) | - | 534 (75.42) | - | 59 (65.56) | - |

| No | 205 (25.66) | - | 60 (20.41) | - | 84 (21.71) | - | 174 (24.58) | - | 31 (34.44) | - |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 146.70±98.83 | 137.94±78.19 | 149.57±96.61 | 140.25±79.55 | 149.33±104.49 | 142.17±81.18 | 145.54±99.04 | 138.35±79.88 | 156.19±97.58 | 134.57±62.89 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 99.28±33.33 | 88.76±29.49 | 101.37±32.62 | 91.06±29.18 | 97.35±34.00 | 86.96±29.13 | 99.65±34.13 | 88.54±29.42 | 96.91±27.65 | 91.85±30.84 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 48.26±13.80 | 49.69±13.61 | 47.02±12.42 | 49.66±13.80 | 48.81±14.00 | 49.19±12.24 | 48.05±13.89 | 49.70±13.76 | 49.84±13.19 | 49.60±12.46 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 171.84±38.98 | 162.03±36.80 | 172.58±40.70 | 162.81±42.85 | 171.36±39.52 | 160.24±31.73 | 171.08±39.60 | 161.60±37.20 | 178.06±33.54 | 165.89±33.54 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 145.78±50.61 | - | 149.37±53.02 | - | 141.49±46.37 | - | 148.19±51.85 | - | 124.78±31.21 | - |

| HbA1c, % | 7.64±1.68 | - | 7.68±1.66 | - | 7.58±1.65 | - | 7.70±1.72 | - | 7.27±1.30 | - |

| ≥7 | 438 (58.40) | - | 174 (61.27) | - | 203 (57.34) | - | 393 (59.46) | - | 45 (51.14) | - |

| <7 | 312 (41.60) | - | 110 (38.73) | - | 151 (42.66) | - | 268 (40.54) | - | 43 (48.86) | - |

| Insulin therapy | ||||||||||

| Yes | 147 (18.40) | 141 (17.65) | 65 (22.11) | 63 (21.43) | 61 (15.76) | 57 (14.73) | 139 (19.63) | 133 (18.79) | 8 (8.89) | 8 (8.89) |

| No | 652 (81.60) | 658 (82.35) | 229 (77.89) | 231 (78.57) | 326 (84.24) | 330 (85.27) | 569 (80.37) | 575 (81.21) | 82 (91.11) | 82 (91.11) |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin.

aPhysician behavior change means treatment change. Patient's behavior change means any change of smoking, drinking, exercise, stress management and adherence, bComorbidity “yes” means any one of hypertension, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, fatty liver, diabetic neuropathy, thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism, asthma, chronic obstruction pulmonary disease, and etc.

K-ADDQoL

In global questions of ADDQoL, the score of present QoL (“My present quality of life”) and QoL without DM (“If I did not have diabetes”) between baseline and after 6 months were not significantly different, respectively; score of present QoL was 0.49±0.92 at baseline vs. 0.47±0.86 after 6 months (P=0.613); score of QoL without DM were −1.48±0.98 at baseline and −1.47±0.91 after 6 months (P=0.6723).

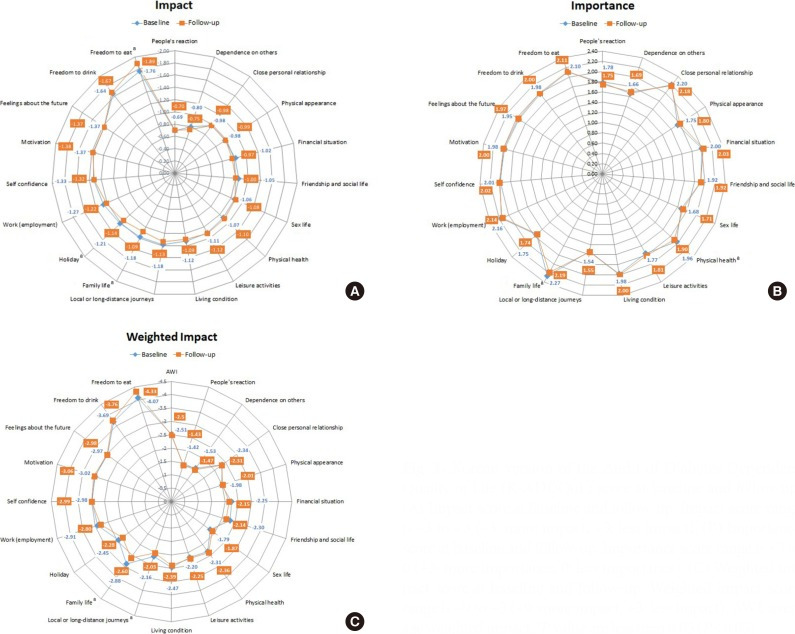

The impact ratings at baseline for the 19 domains for K-ADDQoL ranged from −1.76 to −0.69, which were changed to −1.89 and −0.70 after 6 months. DM had the greatest impact on the freedom to eat domain, with scores significantly rising from −1.76±0.93 at baseline to −1.89±0.90 at 6 months (P=0.003). The domain with the least impact was people's reaction (−0.69±0.88 at baseline and −0.70±0.88 at 6 months). The impacts on holidays (P=0.038) and family life (P=0.004) significantly decreased at 6 months from the baseline scores. The impact score of friendship and social life domain decreased at 6 months from the baseline scores in statistically boarder-line (P=0.0550) (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Korean version of the Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life (K-ADDQoL) score at baseline and follow-up. (A) Impact score at baseline and follow-up. Impact score range is −3 to +3 (−3: more impact, +3: less impact). (B) Importance score at baseline and follow-up. Importance score range is +3 to 0 (+3: more importance, 0: less importance). (C) Weighted impact score at baseline and follow-up. Weighted impact score range is −9 to +3 (−9: more impact, +3: less impact). AWI, average weighted impact. aP value are less than 0.05 (P<0.05).

The importance ratings at baseline for the 19 domains ranged from 1.54 to 2.27 and 1.55 to 2.19 at 6 months. Family life was perceived as the most important (2.27±0.66, 2.19±0.68), while local or long-distance journey were perceived as relatively less important (1.54±0.81, 1.55±0.75) both at baseline and 6 months. The importance of physical health (P=0.022) and family life (P=0.001) decreased after 6 months from the baseline (Fig. 1B).

WI at baseline ranged from −4.07 to −1.42 and from −4.33 to −1.43 after 6 months. DM had the highest negative impact on freedom to eat (−4.07±2.87 at baseline and −4.33±2.83 at 6 months), and the negative impact significantly increased after 6 months compared to that at baseline (P=0.049). DM had relatively less negative impact on people's reaction (−1.42±2.11 at baseline and −1.43±2.11 at 6 months) compared with other domains. WI on the family life (P=0.001) and friendship and social life (P=0.027) domains changed significantly less negatively over 6 months. AWI score was −2.51±1.36 at baseline and −2.50±1.29 after 6 months. AWI changed insignificantly over 6 months (0.02±1.43) (Fig. 1C).

Changes of QoL by physician and patient behavior

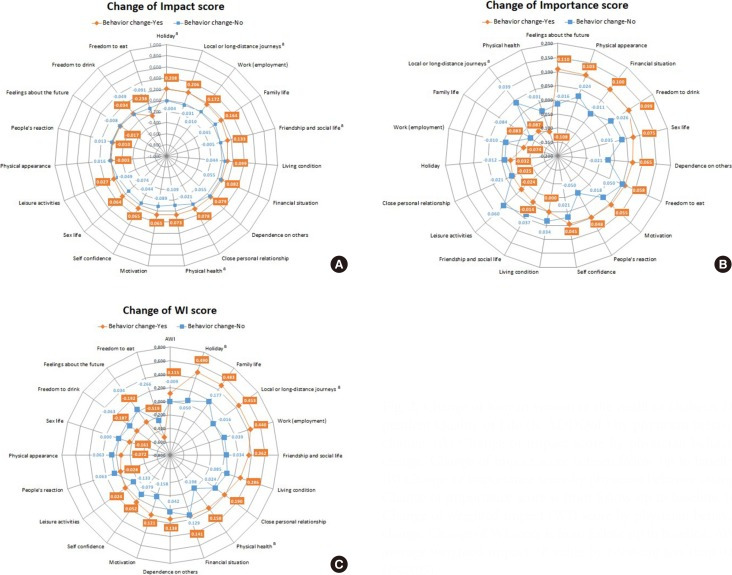

We compared changes of K-ADDQoL scores in relation to changes of physicians' treatment pattern over 6 months. The impact scores for local or long-distance journey (P=0.001), holidays (P=0.008), physical health (P=0.008) and friendship and social life (P=0.040) were significantly different between patients whose physician's behaviors remained the same and those whose physician's behaviors changed. Compared to the former group, the latter group had less negative impact on these domains after 6 months (Fig. 2A). The importance rating for local or long-distance journey (P=0.042) also significantly differed between the two groups, and the group of patients whose physician behavior changed perceived the domain to be less important after 6 months while perceiving their feelings about the future (P=0.0671) to be more important after 6 months (Fig. 2B). The positive changes of WI score in the most domains were bigger in the group of patients whose physician behavior changed than the other group. In particular, the WI score for the local or long-distance journey (P=0.005), physical health (P=0.045), and holiday (P=0.036) domains significantly differed between the two groups (Fig. 2C). However, changes in several domains such as freedom to eat, freedom to drink, sex life, and feelings about the future showed opposite trends, in which the negative changes were bigger in the group whose physician changed treatments than the other group. Changes of AWI was not significantly differed between groups (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. Change of Korean version of the Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life (K-ADDQoL) by physician behavior change. (A) Change of impact score by physician behavior change. Change of impact score is from follow-up to baseline. (B) Change of importance score by physician behavior change. Change of importance score is from follow-up to baseline. (C) Change of weighted impact (WI) score by physician behavior change. Change of WI score is from follow-up to baseline. AWI, average weighted impact. aP value by t-test are less than 0.05 (P<0.05).

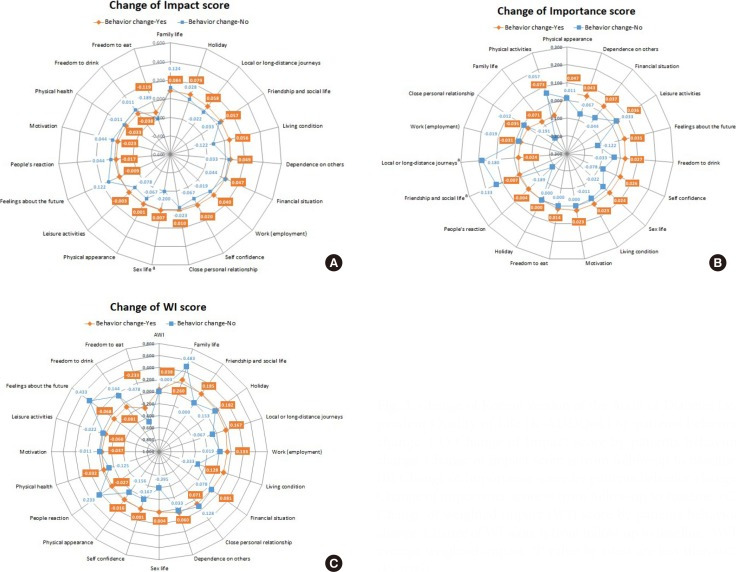

Fig. 3 shows the changes of K-ADDQoL scores in relation to patient behaviors for a 6-month period. The changes of the impact rating for sex life (P=0.028) significantly differed between the group of patients who changed their behaviors and those who did not, where the former group had less negative impact on sex life after 6 months (Fig. 3A). With regard to importance ratings, local or long-distance journey (P=0.002) and friendship and social life (P=0.015) domains significantly differed between the two groups, wherein the group whose patients' behaviors had changed perceived these domains to be less important, whereas the other group (no change of patient behaviors) perceived these domains to be more important after 6 months (Fig. 3B). Significant differences were not observed in the changes in WI in any of the domains over 6 months (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. Change of Korean version of the Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life (K-ADDQoL) by patients behavior change. (A) Change of Impact score by patients behavior change. Change of impact score is from follow-up to baseline. (B) Change of Importance score by patients behavior change. Change of importance score is from follow-up to baseline. (C) Change of weighted impact (WI) score by patients behavior change. Change of WI score is from follow-up to baseline. AWI, average weighted impact. aP value by t-test are less than 0.05 (P<0.05).

Factors associated with AWI at follow-up

In univariate analysis, duration of DM (P=0.062), glucose (P= 0.022), HbA1c (P=0.009), insulin therapy (P=0.032), and changes in patient behaviors (P=0.012) showed a statistical significance. Patients who had their treatment altered by physicians showed less negative AWI score compared to those who have no treatment changes although there was no statistical significance. Among the factors indicating a statistical significance in the univariate analysis, we excluded glucose from the multivariate regression model in consideration of its correlation with HbA1c. Table 2 shows the results of multivariate analysis after adjusting for age and gender. The higher HbA1c level (P=0.012) and the longer duration of DM (P=0.044) were associated with the lower AWI. Patients who changed their behaviors showed negative AWI score compared to those who didn't change their behaviors although there was no statistical significance (P=0.085) (Table 2).

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analyses of average weighted impact score at follow-up.

| Variable | Mean±SD | Univariate | Multivariatea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | P value | Coeff. | P valueb | ||

| Age, yr | 0.030 | 0.399c | 0.043 | 0.306 | |

| Gender | 0.572 | 0.567d | |||

| Male | −2.51±1.24 | 0.016 | 0.693 | ||

| Female | −2.48±1.33 | Reference | |||

| BMI | 0.001 | 0.984c | |||

| Waist circumference | 0.012 | 0.772c | |||

| SBP | 0.051 | 0.156c | |||

| DBP | 0.018 | 0.613c | |||

| DM duration, yr | −0.067 | 0.062c | −0.087 | 0.044 | |

| <5 | −2.43±1.29 | 3.080 | 0.380e | ||

| 5–9 | −2.42±1.28 | ||||

| 10–14 | −2.50±1.10 | ||||

| ≥15 | −2.65±1.41 | ||||

| Comorbidity | −1.485 | 0.138d | |||

| Yes | −2.46±1.26 | ||||

| No | −2.61±1.36 | ||||

| Triglycerides | 0.030 | 0.431c | |||

| LDL-C | 0.005 | 0.902c | |||

| HDL-C | 0.022 | 0.569c | |||

| Total cholesterol | 0.001 | 0.979c | |||

| Glucose | −0.093 | 0.022c | |||

| HbA1c | −0.095 | 0.009c | −0.110 | 0.012 | |

| Insulin therapy | −2.144 | 0.032d | |||

| Yes | −2.68±1.30 | −0.016 | 0.721 | ||

| No | −2.45±1.28 | Reference | |||

| Physician behavior change | 0.584 | 0.559d | |||

| Yes | −2.45±1.29 | 0.040 | 0.326 | ||

| No | −2.52±1.31 | Reference | |||

| Patients behavior change | 2.501 | 0.012d | |||

| Yes | −2.54±1.28 | −0.070 | 0.085 | ||

| No | −2.19±1.22 | Reference | |||

SD, standard deviation; Coeff., coefficient; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin.

aAdjusted by age and gender, bP value by multivariate linear regression, cP value by Spearman correlation analysis, dP value by Mann-Whitney U test, eP value by Kruskal-Wallis test.

DISCUSSION

This investigated changes of QoL for 6 months according to changes in physicians' and patients' behaviors after perceiving CV risks in patients with type 2 DM aged ≥40 years.

Patients included in this study showed a baseline AWI of −2.51, which was similar to that reported by previous studies in Korea (−2.93 and −2.73, respectively) [24,25]. The AWI reported in a Singaporean study [26] was also similar, at −2.5, suggesting that QoL of patients with DM is similar across Asian countries.

With regard to WI scores for each of 19 domains that compose the K-ADDQoL, the scores were the lowest for the freedom to eat and freedom to drink domains, indicating that DM has the greatest negative impact on these domains of life. On the other hand, WI scores were relatively high for the people's reaction and dependence on others, indicating that DM has a relatively less negative impact on these domains of life. These findings were similar to those of a previous Korean study [24]. Further, as with our findings, the freedom to eat domain was the most negatively impacted domain in studies conducted in other Asian, European, and South American countries (Singapore, UK, Malaysia, Argentina, Taiwan, Greece, and Slovakia) [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Many countries, including Asian countries, enforce dietary management for patients with DM to prevent CV complications, and subsequently, DM had the greatest negative impact on dietary domains.

Although the QoL of patients with DM has been extensively studied in the literature, data on changes of their QoL over time in usual practice have not yet been reported sufficiently. In this context, we investigated changes in QoL over a 6-month period from the enrollment in the study. After 6 months, the AWI score was −2.50±1.29, which was not significantly different from that at the baseline. The WI score for the freedom to eat domain, which was the greatest negative impact at the baseline, showed worse score at 6 months. Patients with DM are recommended to reduce salt intake in their diets to prevent complications. “Salt intake from soups” is high and accounts for approximately 11% of Koreans' total salt intake [33]; however, recommendations to reduce soup intake poses a considerable restriction on patients' food intake, possibly contributing to a low QoL related to the freedom to eat in patients with DM. On the other hand, the WI scores for the family life and friendship and social life domains improved after 6 months.

In our previous study [15], treatment patterns and patient behaviors changed when physicians and patients perceived the risks of CVDs. In this study, we further analyzed the changes in QoL scores in relation to changes of physicians and patients' behaviors. Those patients who had a treatment change showed an improvement in impact scores related to local or long-distance journey, holidays, physical health, and friendship and social life domains, suggesting a less negative impact on these domains. When treatment is altered, patients with DM may feel that they are receiving intensive care by physicians and that the QoL is improved in the certain domains because patients feel that DM is improving.

The impact rating for sex life improved in the group of patients who changed their behaviors, indicating a less negative impact on sex life after 6 months compared to that at the baseline. DM is one of the risk factors for sexual dysfunction, and most female patients with type 2 DM express problems with their sex lives [34]. We believe that patients who feel uncomfortable with their sex life due to the disease may think their health condition is better after changing their lifestyle and have less negative influence on their sex life.

The WI scores of QoL which reflect the importance domains in life and the impact of DM on patients' life improved in the most domains when physicians' behavior changed. However, since worsening of the score in some domains (freedom to eat, freedom to drink, etc.) were shown in groups where the behavior of physician changed, AWI score was not finally differed between groups. We assume that the worsening in those domains may be derived as patients were restricted in their daily life for better disease management with intensive treatment.

The AWI measured after 6 months from the baseline was associated with the duration of DM and Hb1Ac levels. The higher the Hb1Ac levels, the lower the AWI score. High Hb1AC levels are known to increase the risk of CVD [24], and aggressive dietary and intensive care by the physician to maintain Hb1Ac at normal ranges intensify the inconvenience in a patient's life, thereby impairing the QoL. The longer the duration of DM, the lower the AWI score, and the greater the negative impact of DM on a patient's life. The longer duration of the dietary regimen for DM management has a negative impact on a patient's freedom to eat, which is consistent with the results in a Singaporean study [26]. Furthermore, patients' behavioral changes were more negatively associated with AWI compared to no change of patients' behaviors with statistically marginal significance. Patients who changed their behaviors showed worse score of WI than patients who did not change their behaviors in the domains of feeling about the future, leisure activities, motivation, people's reaction, and freedom to drink. Most of those domains are linked to social life, thus their social life may be restricted while the patients made efforts in modification in their life style due to DM.

This study has a few limitations. First, this was conducted only on patients with DM aged ≥40 years. Previous studies showed the higher AWI score among patients with DM younger than 40 years (−3.75) [24], suggesting that a patients' perceived QoL may differ across age groups. Although the fact that observing changes in a patient's QoL over a 6-month period may be one of our study's strengths since no study has investigated the changes of AWI, the observation period of 6 months would be insufficient to explore the QoL changes among the patients having the DM for mean 8.12 years. Further, in this study, we assumed that the changes in behaviors of physicians and patients during the follow-up were related to the awareness of CV risks after CUS. However, physicians often change the treatments when the patients' glycemic control or BP worsened or the patients' conditions changed. Therefore, we suggest a further study, including the proper control group matching to patients who do not aware of their CV risks and for longer observational periods.

DM had negative impacts majorly on food-related life domains and the longer duration of DM showed the greater and the negative impact on their life due to the loss of freedom to eat for the disease control. Changes in physicians' behaviors, as a result of perceiving CVD risks, could improve the quality of some domains of life in patients with DM, which would be resulted by instilling a belief into patients regarding physicians' utmost efforts for provision of personalized management of the disease. Therefore, physicians should recognize the importance of understanding CVD risks associated with DM and implement appropriate management to improve the QoL and reduce CV complications in patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Korea Ltd. The authors wish to thank the following research investigators: Tae-Sik Jung from Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Hye-Soon Kim from Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Ho Sang Shon from Daegu Catholic University Medical Center, Eun-Gyoung Hong from Hallym University Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital, Chul-Woo Ahn from Gangnam Severance Hospital, Sook Chon from Kyung Hee University-Industry Cooperation Foundation, Young-Sik Choi from Kosin University Gospel Hospital, Hyung Jin Kim from Kim Hyung Jin Department of Internal Medicine, In-Joo Kim from Pusan National University Hospital, Jung-Hyun Park from Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Soo-Kyung kim from CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Kyu Yeon Hur from Samsung Medical Center, Heung Yong Jin from Chonbuk National University Hospital, Sung Hoon Kim from Cheil General Hospital, Jae-Taek Kim from Chung-Ang University Hospital, Chung-Ang University Industry Academic Cooperation Foundation, Ji-Hyun Ahn from Chung-Ang University Hospital, and Ok-Hyun Ryu from Hallym University Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: This study was funded by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Korea Ltd. No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

- Conception or design: Y.J.K., I.K.J., S.G.K., D.H.C., C.H.K., C.S.K., W.Y.L., K.C.W., J.H.C., J.L., D.M.K.

- Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Y.J.K., I.K.J., S.G.K., D.H.C., C.H.K., C.S.K., W.Y.L., K.C.W., J.H.C., J.L., D.M.K.

- Drafting the work or revising: Y.J.K., J.H.C., D.M.K.

- Final approval of the manuscript: Y.J.K., I.K.J., S.G.K., D.H.C., C.H.K., C.S.K., W.Y.L., K.C.W., J.H.C., J.L., D.M.K.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2018.0251.

Nineteen domains of Korean version of the Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life

References

- 1.Kim DJ. The epidemiology of diabetes in Korea. Diabetes Metab J. 2011;35:303–308. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2011.35.4.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. Geneva: WHO Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 8th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Shehri AH, Taha AZ, Bahnassy AA, Salah M. Health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:352–360. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2008.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryu J, Lee HA, Lee WK, Kim M, Min J, Hong YS, Park H. The association of self-care behavior and the quality of life among outpatients with diabetes. Korean J Fam Pract. 2014;4:122–130. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozorgmanesh M, Hadaegh F, Sheikholeslami F, Azizi F. Cardiovascular risk and all-cause mortality attributable to diabetes: Tehran lipid and glucose study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012;35:14–20. doi: 10.3275/7728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu AZ, Qiu Y, Radican L, Luo N. Marginal differences in health-related quality of life of diabetic patients with and without macrovascular comorbid conditions in the United States. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:825–832. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9819-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maddigan SL, Feeny DH, Johnson JA. Health-related quality of life deficits associated with diabetes and comorbidities in a Canadian National Population Health Survey. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1311–1320. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-6640-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:229–234. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Standards of medical care in diabetes-2016: summary of revisions. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:S4–S5. doi: 10.2337/dc16-S003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Diabetes Federation. Global guideline for type 2 diabetes. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naghavi M, Falk E, Hecht HS, Jamieson MJ, Kaul S, Berman D, Fayad Z, Budoff MJ, Rumberger J, Naqvi TZ, Shaw LJ, Faergeman O, Cohn J, Bahr R, Koenig W, Demirovic J, Arking D, Herrera VL, Badimon J, Goldstein JA, Rudy Y, Airaksinen J, Schwartz RS, Riley WA, Mendes RA, Douglas P, Shah PK SHAPE Task Force. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient. Part III: executive summary of the Screening for Heart Attack Prevention and Education (SHAPE) task force report. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:2H–15H. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens RJ, Kothari V, Adler AI, Stratton IM United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. The UKPDS risk engine: a model for the risk of coronary heart disease in type II diabetes (UKPDS 56) Clin Sci Lond. 2001;101:671–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong IK, Kim SG, Cho DH, Kim CH, Kim CS, Lee WY, Won KC, Kim DM. Impact of carotid atherosclerosis detection on physician and patient behavior in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a prospective, observational, multicenter study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16:220. doi: 10.1186/s12872-016-0401-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients is affected by complications but not by intensive policies to improve blood glucose or blood pressure control (UKPDS 37) Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1125–1136. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.7.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Quality of life and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 1999;15:205–218. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199905/06)15:3<205::aid-dmrr29>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. The third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Sejong: KIHASA; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Health Promotion Foundation. Customized visiting health management project. Sejong: KIHASA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morisky DE, Levine DM, Green LW, Shapiro S, Russell RP, Smith CR. Five-year blood pressure control and mortality following health education for hypertensive patients. Am J Public Health. 1983;73:153–162. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Speight J, Reaney MD, Barnard KD. Not all roads lead to Rome: a review of quality of life measurement in adults with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2009;26:315–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradley C, Todd C, Gorton T, Symonds E, Martin A, Plowright R. The development of an individualized questionnaire measure of perceived impact of diabetes on quality of life: the ADDQoL. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:79–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1026485130100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley C, Speight J. Patient perceptions of diabetes and diabetes therapy: assessing quality of life. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18:S64–S69. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung JO, Cho DH, Chung DJ, Chung MY. An assessment of the impact of type 2 diabetes on the quality of life based on age at diabetes diagnosis. Acta Diabetol. 2014;51:1065–1072. doi: 10.1007/s00592-014-0677-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung JO, Cho DH, Chung DJ, Chung MY. Assessment of factors associated with the quality of life in Korean type 2 diabetic patients. Intern Med. 2013;52:179–185. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.7513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shim YT, Lee J, Toh MP, Tang WE, Ko Y. Health-related quality of life and glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Singapore. Diabet Med. 2012;29:e241–e248. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sundaram M, Kavookjian J, Patrick JH, Miller LA, Madhavan SS, Scott VG. Quality of life, health status and clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes patients. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:165–177. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jannoo Z, Yap BW, Musa KI, Lazim MA, Hassali MA. An audit of diabetes-dependent quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Malaysia. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:2297–2302. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0969-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pichon-Riviere A, Irazola V, Beratarrechea A, Alcaraz A, Carrara C. Quality of life in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients requiring insulin treatment in Buenos Aires, Argentina: a cross-sectional study. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4:475–480. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang HF, Yeh MC. The quality of life of adults with type 2 diabetes in a hospital care clinic in Taiwan. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:577–584. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papazafiropoulou AK, Bakomitrou F, Trikallinou A, Ganotopoulou A, Verras C, Christofilidis G, Bousboulas S, Μelidonis Α. Diabetes-dependent quality of life (ADDQOL) and affecting factors in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 in Greece. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:786. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1782-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmanova E, Ziakova K. Audit diabetes-dependent quality of life questionnaire: usefulness in diabetes self-management education in the Slovak population. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:1276–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yon M, Lee Y, Kim D, Lee J, Koh E, Nam E, Shin H, Kang BW, Kim JW, Heo S, Cho HY, Kim CI. Major sources of sodium intake of the Korean population at prepared dish level: based on the KNHANES 2008 & 2009. Korean J Community Nutr. 2011;16:473–487. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaya Erten Z, Zincir H, Ozkan F, Selcuk A, Elmali F. Sexual lives of women with diabetes mellitus (type 2) and impact of culture on solution for problems related to sexual life. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:995–1004. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Nineteen domains of Korean version of the Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life