Abstract

Strobilurin fungicides are used primarily in fruits and vegetables, but recently, a patent was issued for one strobilurin fungicide, azoxystrobin, in mold-resistant wallboard. This raises concerns about the potential presence of these chemicals in house dust and potential exposure indoors, particularly in young children. Furthermore, recent toxicological studies have suggested that strobilurins may cause neurotoxicity. Currently, it is not clear whether or not azoxystrobin applications in wallboard lead to exposures in the indoor environments. The purpose of this study was to determine if azoxystrobin, and related strobilurins, could be detected in house dust. We also sought to characterize the concentrations of azoxystrobin in new wallboard samples. To support this study, we collected and analyzed 16 new dry wall samples intentionally marketed for use in bathrooms to inhibit mold. We then analyzed 188 house dust samples collected from North Carolina homes in 2014-2016 for azoxystrobin and related strobilurins, including pyraclostrobin, trifloxystrobin and fluoxastrobin using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Detection frequencies for azoxystrobin, pyraclostrobin, trifloxystrobin and fluoxastrobin ranged from 34 – 87%, with azoxystrobin being detected most frequently and at the highest concentrations (geometric mean=3.5 ng/g; maximum=10,590 ng/g). Azoxystrobin was also detected in mold-resistant wallboard samples, primarily in the paper covering where it was found at concentrations up to 88.5 μg/g. Cumulatively, these results suggest that fungicides present in wallboard may be migrating to the indoor environment, leading to exposure in the residences that would constitute a separate exposure pathway independent of dietary exposures.

Keywords: azoxystrobin, indoor exposure, house dust, strobilurin fungicides, wallboard

Introduction

Strobilurin pesticides, which include azoxystrobin, pyraclostrobin, fluoxastrobin and trifloxystrobin, are fungicides originally derived from the fungus Strobilurus tenacellus and are most commonly applied to fruits and vegetables. Strobilurin fungicides act as disruptors of mitochondrial respiration by binding to QO sites of the cytochrome bc1 complex in target fungi (1). Given that mitochondria are the target of these fungicides, they may potentially elicit a wide range of acute and chronic toxic effects. These fungicides are highly toxic to many vertebrate and invertebrate aquatic species (2–7); however, comparatively little is known about toxic effects in non-aquatic species, including mammals. Recently, a review paper raised concerns about the use of fungicides in food and provided risk quotients for a variety of common use fungicides (7). Interestingly, a meta-analysis included in the paper found pyraclostrobin and azoxystrobin to have the highest risk quotients. Other studies highlighted the potential for these chemicals to cause neurotoxicity in vitro (8, 9). Additionally, pyraclostrobin has been demonstrated to stimulate mitochondrial dysfunction and adipogenic activity in human cell lines (10, 11); however, effects by other strobilurins have not been evaluated. It is interesting to note that strobilurins have been dissolved in aqueous vehicles when dosing animals in some toxicity studies; however, pyraclostrobin is not soluble in water at the doses used in these studies, suggesting that the true dose or exposure to pyraclostrobin and other strobilurin fungicides was likely much lower than the intended dose, and as a consequence, their toxicity may be underestimated (12). These findings raise concerns about human health consequences from exposures to these pesticides, particularly in mixtures, and the extent to which humans are exposed to these pesticides.

Until recently, the primary source of exposure to strobilurin pesticides for the general population has been assumed to occur through the diet via consumption of produce containing strobilurin residues. However, additional pathways may contribute to exposures. For example, strobilurins are used to treat fungal diseases in lawns, landscaping and turf grass in formulations such as Heritage (Syngenta; azoxystrobin), DiseaseEX (Scotts; azoxystrobin), Insignia (BASF, pyraclostrobin), Compass (Bayer, trifloxystrobin) and Cabrio (Bayer, fluoxastrobin). These are not restricted-use pesticides, and they are used by both homeowners and professionals. Strobilurin concentrations, provided on the product label, can vary widely depending on formulation (e.g., 0.31-50% w/w for azoxystrobin). It is possible that the use of these fungicides on home lawns and landscapes may contribute to human exposures not only during application but also from contact during time spent outdoors and from tracking treated soil and plant matter into the home environment where they may ultimately accumulate in house dust. Additionally, azoxystrobin has been patented for use in mold-resistant building materials, including wallboard. Although these products were first registered with the EPA in 2004 (13), they were not available in the U.S. market until 2009, and use of mold-resistant wallboard in new construction and home renovations raises concerns about potential human exposure to these fungicides. Strobilurin-treated wallboard products include the XP line of Gold Bond® Purple® gypsum board (National Gypsum), and M-Bloc™ gypsum board product line (American Gypsum). These products are treated with azoxystrobin, along with thiabendazole, marketed as Sporgard™ (Lanxess Corporation) and AzoTech™ (Syngenta). The presence and amount of fungicides in treated wallboard is not listed on the product, and the purchaser may be unaware that the product contains these fungicides. Additionally, whether or not strobilurins in treated construction materials migrate into the indoor environment and contribute to exposure is currently unknown. While estimates of human exposure to strobilurins are available from dietary sources and for occupational exposures, estimates of exposure for these pesticides from non-dietary sources, particularly in indoor environments, have not been evaluated for the general population.

The presence of these compounds in house dust would suggest that the indoor environment is a potential source of exposure for strobilurin pesticides, outside of diet. Children, in particular, receive higher exposure to chemicals found in house dust as they have smaller bodies and have more contact with dust particles. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to quantify the distribution of a group of strobilurins in samples of house dust and to quantify azoxystrobin levels in new wallboard samples. We collected 16 wallboard samples from home improvement stores across several states within the U.S. that were intentionally marketed to inhibit mold. We analyzed both the paper and the mineral content in each dry wall sample and reported the concentrations. To examine exposure potential, we collected 188 house dust samples in 2014-2016 in central North Carolina as part of the Toddlers Exposure to Semi-volatile organic chemicals in the Indoor Environment study (“TESIE”). Children’s potential exposure to the fungicides was then estimated using exposure factors from the U.S. EPA’s Exposure Factors Handbook 2011 Edition.

Methods

Wallboard Sample Collection and Preparation

Convenience samples of wallboard (n=16) were collected by a group of friends and family living in various states around the U.S., including CA, CO, DE, IN, MD, NC, NJ, NV, NY, PA and WA. All samples purchased new from large chain stores and were marketed for use in damp locations. The paper covering was removed from the gypsum layer and both components were analyzed separately.

House Dust Collection

House dust was collected as part of the TESIE study based in central North Carolina (14,15). Details describing the cohort recruitment are reported in Hoffman et al. (14). Briefly, between 2014 and 2016, families with children 3-6 years of age were invited to participate in TESIE. As described by Phillips, Hammel, et al., study staff conducted a home visit with 188 enrolled families and collected a dust sample from the main living area of the home using a vacuum cleaner fitted with a thimble for dust collection (15). All study protocols and related materials were reviewed and approved by the Duke Medicine Institutional Review Board (Duke IRB Protocol #55540). Legal guardians provided informed consent prior to the collection of samples and questionnaire data for the TESIE study. To explore whether azoxystrobin in the home might be related to when the homes were built or the size of the home, housing data were obtained using county property tax records. Tax assessment information was available for 122 homes but was unavailable for public housing units, apartments and mobile homes/trailers thus housing characteristics for these homes were unknown (n=65).

Analysis of Strobilurin Pesticides

Analyses focused on four strobilurin pesticides, which have not been previously quantified in house dust. Dust sample collection and preparation details are reported by Phillips, Hammel et al. (15). Briefly, dust samples (~ 100 mg) and wallboard paper and gypsum (100 mg) were extracted by sonication for 15 min in 5 mL 1:1 dichloromethane:hexane (v/v). Extracts were cleaned with Super-clean ENVI-Florisil (6 mL, 500 mg bed) in three fractions: hexane (F1), ethyl acetate (F2), and methanol (F3). Strobilurins eluted in F2. To evaluate the efficiency of our extraction method, we measured the recoveries of a 50 ng spike of each strobilurin into 100 mg of a Standard Reference Material (SRM) (NIST SRM 2585) in triplicate. These spiked SRM samples were treated the same way as the dust samples.

Strobilurin Analysis:

The house dust extraction method was evaluated for strobilurins, which eluted from the dust extracts in the ethyl acetate (F2) fraction of the Florisil cleanup for dust extracts. Strobilurins were analyzed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS; Agilent 6460 QQQ MS) with separation on a Luna 2.5 μm C18 50×2 mm column (Phenomenex) using a gradient of 10% formic acid (A) / 10% formic acid in methanol (B) (30% B 0-0.2 min, to 99% B at 2 min, hold 99% B to 6 min) at 0.3 mL/min and with a 20 μL injection. Deuterated (D6) linuron (CDN Isotopes, Pointe-Claire, QC, Canada) was used as an internal standard. Analytes were detected by multiple reaction monitoring for the following transitions: azoxystrobin 404.1>372.0 m/z; fluoxastrobin 459.1>427.0 m/z; pyraclostrobin 388.1>194.0 m/z; trifloxystrobin 409.1>185.9 m/z; D6-linuron 255.1>175 m/z. Wallboard paper and gypsum samples were analyzed for azoxystrobin by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry with electron impact ionization (GC/MS-EI) (Agilent 6900 GC/5975 MS) with 1 μL pulsed splitless injection on a programmable temperature inlet (80-300°C, 10°C/s). 13C6-cis permethrin (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc, MA) was used as the internal standard. Separation was achieved with DB-5MS 30m x 250 μm, 0.25 μm film column with constant flow (1.3 mL/min) and a thermal gradient of 80°C for 2 min; to 250°C at 20°C/min; to 260°C at 1.5°C/min; to 300°C at 25°C/min for 20 min. The transfer line and EI source were held at 300°C, with emission 35 μA, electron energy 70 eV. Analytes were detected by selected ion monitoring: azoxystrobin 344.1 m/z and 13C6-cis permethrin 189 m/z. Very little to no strobilurins were detected in the lab processing blanks and ranged from 0.002-1.21 ng for azoxystrobin, 0.001-0.253 ng for fluoxastrobin, 0.001-0.027 ng for pyraclostrobin, and 0.002-0.004 ng for trifloxystrobin.

Recoveries of the 50 ng spike of strobilurins into SRM 2585 varied across the compounds, from 68% for azoxystrobin to 151% for fluoxastrobin. Dust SRM 2585 was below detection for azoxystrobin and fluoxastrobin in unspiked samples, while pyraclostrobin and trifloxystrobin were detected at 1.21±0.36 and 0.45±0.19 ng/g, respectively (Table 1). These concentrations were measured alongside the other dust samples and then verified with high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry (HRAMS) to reduce interferences from non-strobilurin ions of similar mass. HRAMS was performed on a Q-Exactive GC hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap GC-MS/EI-MS (Thermo Scientific™) equipped with a Thermo TraceGOLD TG-5HT column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 μm film thickness) operating under chromatographic conditions described above. Mass accuracies were <5 ppm at a resolution of 60,000 (200 m/z). Quantification and qualifier ions, respectively, included 344.1029678 and 388.0927970 for azoxystrobin, 188.058029 and 219.0764187 for fluoxastrobin, 132.0443904 and 164.0706051 for pyraclostrobin, and 116.0494758 and 131.0729509 for trifloxystrogin. For the wallboard sample extractions, which did not require a Florisil cleanup or purification step, azoxystrobin spike recoveries were 92% and 96% of a 10 and 100 ng matrix spikes, respectively.

Table 1.

Strobilurin background levels measured in dust SRM 2585 and measured recoveries in spiked dust.

| Azoxystrobin | Fluoxastrobin | Pyraclostrobin | Trifloxystrobin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDL (ng/g) | <0.001 | 5.23 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| SRM 2585 (ng/g) | <MDL | <MDL | 1.21 ± 0.36 | 0.45 ± 0.19 |

| Spike Recovery (%) | 68 ± 37 | 151 ± 3 | 116 ± 13 | 89 ± 7.0 |

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Office 2011) or R (version 3.4.2), with statistical significance defined at the alpha = 0.05 level. Method detection limits (MDLs) were calculated by multiplying the standard deviation of the laboratory processing blanks by three. All dust and wallboard concentrations were blank corrected using the average level measured in the laboratory processing blanks (i.e., organic solvents only). Descriptive statistics were calculated for wallboard and house dust samples. These analyses revealed that concentrations of strobilurins were not normally distributed, and accordingly, we report medians, geometric means and used non-parametric statistical tests as appropriate. We evaluated characteristics of the homes and their potential associations with azoxystrobin concentrations in house dust. Given that azoxystrobin-treated wallboard did not come to market until around 2004, we explored whether or not azoxystrobin in household dust might be related to when the homes were built, which may determine the types of materials used in construction. We grouped homes by year of construction: <1960, 1960-1977, 1978-1989, 1990-2003, 2004-2008 and 2009-2014 and evaluated relationships between the year of home construction and azoxystrobin concentrations using a Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test. Similar analyses were conducted for the size of the home (categorized as <1500, 1500-2500, >2500 or unknown square footage). Values less than the MDL (e.g., 13 dust samples for azoxystrobin) were replaced with a value equal to MDL/2 for statistical analyses (16).

Results

Azoxystrobin in wallboard

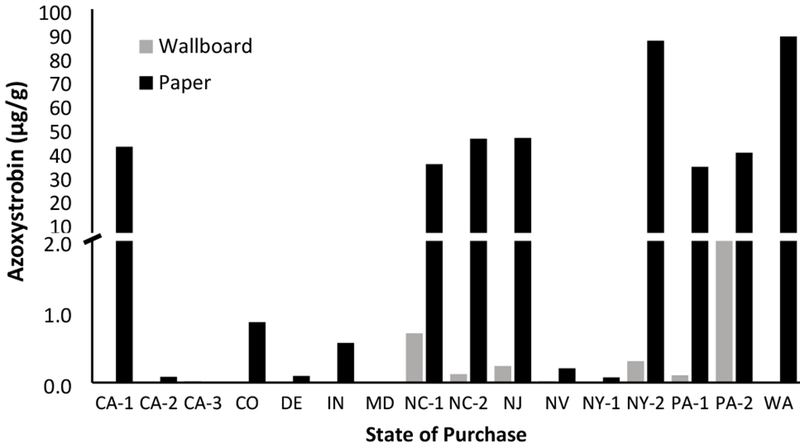

To investigate alternate sources of azoxystrobin in the indoor environment, we evaluated mold-resistant wallboard currently on the market and readily available to homeowners. As azoxystrobin formulations are likely applied to the paper covering in wallboard, we analyzed the paper independently from the interior gypsum mineral. Azoxystrobin in the gypsum portion was detected in 50% of the 16 samples tested, while in the paper portion azoxystrobin was detected in 94% of samples (Figure 1). In our samples of mold-resistant wallboard, the paper contained the majority of azoxystrobin, ranging from 0.01-88.5 μg/g and averaging 17.3 μg/g.

Figure 1.

Azoxystrobin (μg/g) in mold-resistant wallboard samples collected across multiple states.

Characterization of strobilurins in North Carolina house dust samples

All strobilurins investigated were detected in house dust at varying frequencies and ranges as shown in Table 2. Azoxystrobin was the most frequently detected (93% of dust samples) and found at the highest concentrations, ranging from <MDL to 10,587 ng/g in house dust samples. The remaining three compounds were observed at much lower frequencies and concentrations: fluoxastrobin (73% detection, <MDL-40.7 ng/g), pyraclostrobin (36% detection, <MDL-35.6 ng/g), and trifloxystrobin (38% detection, <MDL-2.61 ng/g).

Table 2.

Detection frequency and summary statistics for strobilurins in house dust.

|

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azoxystrobin |

Fluoxastrobin |

Pyraclostrobin |

Trifloxystrobin |

|

| Detection | 175 (93%) | 138 (73%) | 69 (36%) | 71 (38%) |

| n=188 | ng/g |

ng/g |

ng/g |

ng/g |

| MDLa | 0.366 ± 0.726 | 0.103 ± 0.208 | 0.590 ± 1.14 | 0.046 ± 0.091 |

| Summary | ||||

| Minimum | <MDL | <MDL | <MDL | <MDL |

| Median | 2.39 | 0.113 | <MDL | <MDL |

| Maximum | 10,587 | 40.7 | 35.6 | 2.61 |

| Geomean | 3.35 | 0.318 | 0.513 | 0.051 |

MDL values were calculated individually for each sample based on the mass of dust analyzed and averaged across samples for this table.

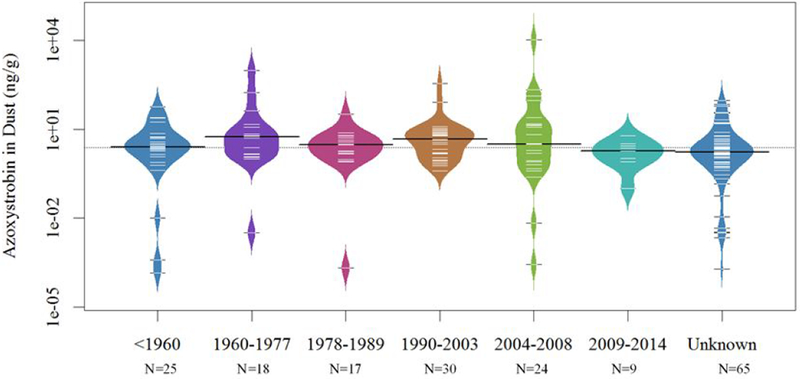

Azoxystrobin levels did not differ significantly by the year of home construction (p=0.14), and levels varied widely for all years (Figure 2). In addition, we evaluated whether the square footage of the home (categorized as <1500, 1500-2500, >2500 or unknown square feet), which could be a proxy for the amount of drywall in the space, was associated with azoxystrobin in dust, but we observed no association (p=0.54).

Figure 2.

Azoxystrobin in dust by year of home construction from property tax records. Homes with unknown year of construction are included in the unknown category. The distribution of the data (shape of the violin plot) are shown with individual colors for each year bin. Black bands represent the median value per category and the dashed white lines indicate individual measured values in individual dust samples. The overall median azoxystrobin concentration (in all categories) is shown by the dashed line.

Exposure Estimates

The U.S. EPA’s EFH provides data for use in estimating exposure via various pathways. For children’s exposure to chemicals in house dust, the EFH suggests using a central tendency estimate of 60 mg of dust ingested per day for children 1-6 years of age (17). If we assume an average child in this age range weighs 15 kg (average weight at 1 year~10 kg and at 6 years~20 kg), then their estimated exposure to azoxystrobin via incidental ingestion of house dust would be 0.013 ng/kg/day, using the geometric mean levels measured in dust with a maximum of 42.3 ng/kg/day using the highest concentration measured.

Discussion

Our results suggest that fungicides are present in wallboard and may be migrating to the indoor environment. We evaluated mold-resistant wallboard samples purchased at stores around the U.S. and found that the majority contained azoxystrobin, particularly in the paper portion. To our knowledge, this is the first report of analysis of azoxystrobin in wallboard. The formulations used to treat wallboard may contain 15-19% w/w azoxystrobin; however, the amount applied during treatment is unknown. Notably, some products contained little to no azoxystrobin, even though the sample came from a product marketed as mold-resistant. This suggests that these products may be treated with formulations that contain something other than azoxystrobin. Overall, these results support the possibility that treated wallboard may contribute to azoxystrobin levels in house dust. Further research is needed to more fully characterize azoxystrobin levels in commercial mold-resistant wallboard as well as the factors that affect the rate and extent of migration to the indoor environment.

Strobilurin pesticides were detected frequently in house dust collected in central North Carolina (2014-2016). Among the strobilurins investigated, azoxystrobin stands out not only as the most frequently detected compound but also the compound detected at the highest levels. Median (2.7 ng/g) values for azoxystrobin were approximately an order of magnitude higher than for other strobilurin pesticides. Notably, the maximum measured azoxystrobin concentration (10, 587 ng/g) was 297 times greater than pyraclostrobin. Although little is known about the fate and persistence of strobilurins in the indoor environment, the higher levels and range in concentrations of particularly azoxystrobin observed in house dust suggest that azoxystrobin on food is not the only source of this compound in the indoor environment when compared to levels observed for other strobilurins also used on foods.

The levels of azoxystrobin in house dust were lower than what we have measured in these samples for other environmentally relevant chemicals including organophosphates (e.g., tris (1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate and tris(2-chloropropyl) phosphate, geometric means (GM) = 4 818 and 4 843 ng/g, respectively (15)), phthalates (e.g., diethylhexyl phthalate, GM = 118 820 ng/g (18)), and brominated flame retardants (e.g., brominated diphenyl ethers 47 and 99, GM = 452 and 741 ng/g, respectively (19)). With regard to other pesticides, the range of values detected for azoxystrobin is similar to that observed for other types of pesticides in indoor dust (e.g., up to 11,000 and 15,100 ng/g for diazinon and chlorpyrifos, respectively (20)); however, the reported values for the median (17.5 and 135 ng/g, respectively) were similar to azoxystrobin measured in the current study (3.35 ng/g).

We hypothesized that the year of construction could be associated with azoxystrobin in dust because drywall formulations containing azoxystrobin were first used in the U.S. in 2008, suggesting that homes built after this time period may have higher levels in dust. However, we did not observe associations between housing characteristics (e.g., housing age and size) and azoxystrobin in household dust. One limitation of the data used to evaluate this hypothesis is that the year of construction does not reflect any home renovations, which frequently involve updates in kitchens and bathrooms where mold-resistant wallboard would be installed. Unfortunately, information about home improvements or any materials used during renovations or construction were not included in the questionnaire for this study; future investigations into the source of azoxystrobin in indoor environments may benefit from gathering this information. It’s also possible that azoxystrobin could be tracked into homes from outdoors, and accumulate in house dust, following applications of fungicides to residential lawns.

Our estimate of children’s potential exposure to azoxystrobin from house dust ingestion based on the geometric mean level was approximately an order of magnitude lower than 1.15 ng/kg/day estimated for dietary azoxystrobin exposure reported by Winter (21). However, based on the highest concentration measured in this study, azoxystrobin exposures via ingested dust could far exceed dietary exposures.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that strobilurin fungicides are present in house dust and represent a potential exposure pathway outside of diet. Furthermore, our analyses suggest that a fair percentage of wallboard samples sold on the market today contain azoxystrobin. The recent introduction and use of this fungicide in wallboard may explain the higher detection frequency and levels of azoxystrobin measured in house dust samples; however, we encourage more research to identify the primary sources to the indoor environment. Our exposure estimates suggest that children may be receiving exposure at levels as high as 42 ng/kg/day in homes with high levels of azoxystrobin in house dust. Given that a recent study ranked azoxystrobin second for the highest risk quotient among fungicides, more research may be warranted to evaluate health risks for some populations, particularly children who are more vulnerable to neurodevelopmental effects.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Grant 83564201) and NIEHS (R01 ES016099). Additional support for ALP and JR was provided by NIEHS (T32-ES021432 and P42ES010356, respectively). We also thank our participants for opening their homes to our study team and helping us gain a better understanding of children’s exposures to pesticides.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest in relation to the work described.

References

- 1.Esser L, Yu CA, Xia D. Structural basis of resistance to anti-cytochrome bc(1) complex inhibitors: implication for drug improvement. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(5):704–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruhl CA, Schmidt T, Pieper S, Alscher A. Terrestrial pesticide exposure of amphibians: an underestimated cause of global decline? Sci Rep. 2013;3:1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooser EA, Belden JB, Smith LM, McMurry ST. Acute toxicity of three strobilurin fungicide formulations and their active ingredients to tadpoles. Ecotoxicology. 2012;21(5):1458–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia W, Mao LG, Zhang L, Zhang YN, Jiang HY. Effects of two strobilurins (azoxystrobin and picoxystrobin) on embryonic development and enzyme activities in juveniles and adult fish livers of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere. 2018;207:573–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H, Cao FJ, Zhao F, Yang Y, Teng MM, Wang CJ, et al. Developmental toxicity, oxidative stress and immunotoxicity induced by three strobilurins (pyraclostrobin, trifloxystrobin and picoxystrobin) in zebrafish embryos. Chemosphere. 2018;207:781–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang JH, Shi Y, Yu RX, Chen LP, Zhao XP. Biological response of zebrafish after short-term exposure to azoxystrobin. Chemosphere. 2018;202:56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zubrod JP, Bundschuh M, Arts G, Bruhl CA, Imfeld G, Knabel A, et al. Fungicides: An Overlooked Pesticide Class? Environ Sci Technol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson BL, Simon JM, McCoy ES, Salazar G, Fragola G, Zylka MJ. Identification of chemicals that mimic transcriptional changes associated with autism, brain aging and neurodegeneration. Nat Commun. 2016;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regueiro J, Olguin N, Simal-Gandara J, Sunol C. Toxicity evaluation of new agricultural fungicides in primary cultured cortical neurons. Environmental Research. 2015;140:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassotis CD, Hoffman K, Stapleton HM. Characterization of Adipogenic Activity of House Dust Extracts and Semi-Volatile Indoor Contaminants in 3T3-L1 Cells. Environmental Science & Technology. 2017;51(15):8735–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luz AL, Kassotis CD, Stapleton HM, Meyer JN. The high-production volume fungicide pyraclostrobin induces triglyceride accumulation associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, and promotes adipocyte differentiation independent of PPARgamma activation, in 3T3-L1 cells. Toxicology. 2018;393:150–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuttle AH, Salazar G, Cooper EM, Stapleton HM, Zylka MJ. Choice of vehicle affects pyraclostrobin toxicity in mice. Chemosphere. 2019;218:501–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azoxystrobin MoldRetardant 2.08 SC, (2004).

- 14.Hoffman K, Hammel SC, Phillips AL, Lorenzo AM, Chen A, Calafat AM, et al. Biomarkers of exposure to SVOCs in children and their demographic associations: The TESIE Study. Environ Int. 2018;119:26–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips AL, Hammel SC, Hoffman K, Lorenzo AM, Chen A, Webster TF, et al. Children’s residential exposure to organophosphate ester flame retardants and plasticizers: Investigating exposure pathways in the TESIE study. Environ Int. 2018;116:176–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antweiler RC, Taylor HE. Evaluation of statistical treatments of left-censored environmental data using coincident uncensored data sets: I. Summary statistics. Environmental Science & Technology. 2008;42(10):3732–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US EPA. Exposure Factors Handbook: 2011 Edition https://wwwepagov/sites/production/files/2015-09/documents/techoverview_efh-completepdf. 2011.

- 18.Hammel SC, Lavasseur JL, Hoffman K, Phillips AL, Lorenzo A, Chen A, et al. Children’s Exposure to Phthalates and Non-Phthalate Plasticizers in the Home: The TESIE Study. In Process. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Stapleton HM, Misenheimer J, Hoffman K, Webster TF. Flame retardant associations between children’s handwipes and house dust. Chemosphere. 2014;116:54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan MK, Wilson NK, Chuang JC. Exposures of 129 Preschool Children to Organochlorines, Organophosphates, Pyrethroids, and Acid Herbicides at Their Homes and Daycares in North Carolina. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2014;11(4):3743–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winter CK. Chronic dietary exposure to pesticide residues in the United States. Int J Food Contam. 2015;2(1). [Google Scholar]