Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the symptom dimensions of Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD; irritability, defiance) and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; inattention, hyperactivity-impulsivity) as predictors of academic performance, depressive symptoms, and peer functioning in middle childhood.

Method:

Children (N=346; 51% female) were assessed via teacher-report on measures of ODD/ADHD symptoms at baseline (grades K-2) and academic performance, depressive symptoms, peer rejection, and victimization on 7 occasions over 4 school-years (from K-2 through 3-5). Self-report and GPA data collected in grades 3-5 served as converging outcome measures. Latent growth curve and multiple regression models were estimated using a hierarchical/sensitivity approach to assess robustness and specificity of effects.

Results:

Irritability predicted higher baseline depressive symptoms, peer rejection, and victimization, whereas defiance predicted higher baseline peer rejection; however, none of these ODD-related effects persisted 3 years later to grades 3-5. In contrast, inattention predicted persistently poorer academic performance, persistently higher depressive symptoms, and higher baseline victimization; hyperactivity-impulsivity predicted subsequent peer rejection and victimization in grades 3-5. In converging models, only inattention emerged as a robust predictor of 3-year outcomes (namely, GPA, depressive symptoms, peer rejection, and relational victimization).

Conclusions:

Broadly, ODD dimensions—particularly irritability—may be linked to acute disturbances in social-emotional functioning in school-age children, whereas ADHD dimensions may predict more persistent patterns of peer, affective, and academic problems. By examining all four ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions simultaneously, the present analyses offer clarity and specificity regarding which dimensions affect what outcomes, and when. Findings underscore the importance of multi-dimensional approaches to research, assessment, and intervention.

Keywords: Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), symptom dimensions, peer functioning, academic performance

Introduction

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are among the most common and impairing psychological conditions in childhood, affecting about 12.6% and 8.7% of youth, respectively (Merikangas et al., 2010). Dimensionally and categorically, both disorders show distinct predictive validity in relation to important clinical and functional outcomes (Frick & Nigg, 2012). Symptoms of ODD/ADHD have particularly key implications for children’s social-emotional and educational functioning in middle childhood, which may have cascading effects throughout subsequent development. However, it remains unclear which aspects of these symptoms affect what psychosocial outcomes, and when. Although ample research has examined psychosocial outcomes between disorders (ODD vs. ADHD), and more recent studies have disentangled the effects of specific symptom dimensions within ODD (irritability vs. defiance) or ADHD (inattention vs. hyperactivity-impulsivity), the relative dimensional effects of irritability, defiance, inattention, and hyperactivity-impulsivity remain unclear. This is an important gap in part because ODD/ADHD symptoms are highly correlated; about 35.0% of those with ODD also have ADHD (Nock et al., 2007), while 46.5% of those with ADHD have ODD (Kessler et al., 2014). Thus, a multidimensional examination of ODD/ADHD symptoms could help advance clinical science toward more targeted and personalized intervention.

Accordingly, the present study investigates the four ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions as distinct predictors of psychosocial trajectories in four developmentally pivotal domains: academic performance, depressive symptoms, peer rejection, and peer victimization. In doing so, we adopt a developmental psychopathology framework (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2002), (a) recognizing that typical and atypical development are mutually informative, (b) examining the individual across contexts and domains of functioning (social, academic), and (c) elucidating multifinality by disentangling typical and atypical trajectories across middle childhood from grades K-2 to 3-5. Further, we use a multi-informant hierarchical modeling approach to help clarify specifically which dimensions affect what outcomes, when (e.g., immediately, long-term), and according to whom (e.g., teacher, child, school records).

Multidimensionality of ODD and ADHD Symptoms

Previously conceptualized as unidimensional, ODD is increasingly recognized as heterogeneous and multidimensional. Most studies have identified the dimensions of irritability (touchy/annoyed, angry/resentful, loses temper) and defiance (argues, defies/refuses, blames, annoys, spiteful/vindictive; Evans et al., 2017). Although highly correlated, factor-analytic work, latent class analysis, and longitudinal studies support their distinction across development (e.g., Burke et al., 2014a; Evans et al., 2017). Specifically, ODD-irritability is linked to depression, anxiety, and reactive aggression, while ODD-defiance is associated with more severe conduct problems and proactive aggression (e.g., Evans et al., 2016; Ezpeleta et al., 2012; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009a,b; Rowe et al, 2010).

Similarly, symptoms of ADHD are comprised of two dimensions: inattention (e.g., distractibility, forgetfulness) and hyperactivity-impulsivity (e.g., fidgeting, interrupting; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Like ODD, ADHD’s dimensions are highly correlated but distinct across development (Milich, Balentine, & Lynam, 2001). Youth with predominantly inattentive symptoms experience more internalizing and academic problems than those with a combined presentation (Milich et al., 2001; Weiss, Worling, & Wasdell, 2003), whereas those with predominantly hyperactive-impulsive symptoms are more likely to have externalizing problems (Connor & Ford, 2012; Decker et al., 2001).

A better understanding of ODD symptom dimensions might come from considering them in relation to ADHD, and vice versa. Much of the relevant literature (reviewed below) tends to focus on ODD and ADHD either in isolation or at the disorder level. Nonetheless, the evidence clearly shows their relevance to academic performance, depressive symptoms, and peer rejection/victimization.

ODD/ADHD Symptoms and Academic, Emotional, and Social Functioning

Associations with academic performance.

Youth with ADHD experience a variety of academic problems (e.g., lower achievement, greater classroom difficulties, and the need for various academic supports) across development (Daley & Birchwood, 2010; Frazier et al., 2007). In elementary through high school, youth with combined or inattentive ADHD subtypes demonstrate lower achievement than their typically developing peers; however, academic performance does not differ between subtypes (e.g., Chhabildas, Pennington, & Willcutt, 2001; McConaughy et al., 2009; Nigg et al., 2002). Semrud-Clikeman (2012) suggested that this lack of difference can be explained by inattention, which was found to uniquely predict poor academic performance among youth with ADHD. Additional research supports inattention as the key factor linking ADHD to academic outcomes (Sayal, Washbrook, & Propper, 2015) from early childhood (McGee et al., 1991) into adulthood (Miranda et al., 2014). These associations hold even after controlling for variables like IQ, SES, behavior problems, and learning disorders (Carmine et al., 2009; Daley & Birchwood, 2010; Polderman et al., 2010; Semrud-Clikeman, 2012).

The relation between ODD and academic achievement is less clear. While some research demonstrates that oppositional behaviors are associated with academic problems in middle childhood and adolescence (e.g., Drabick, et al., 2004; McGee et al., 1985), the majority of studies suggest that ODD symptoms do not uniquely predict poor academic performance (especially after controlling for ADHD symptoms; Daley & Birchwood, 2010; Clark, Prior, & Kinsella, 2002; Frazier et al., 2007; McGee, Williams, & Silva, 1985). Fergusson and colleagues (1993) suggest that antisocial behavior seems to be associated with low academic performance only because of the high co-occurrence of ODD and ADHD. Yet, other studies have found that ODD exacerbates classroom behavior problems in elementary through high school age youth with ADHD (Liu, Huang, Kao, & Gau, 2017) and can predict significant functional outcomes (e.g., relational, occupational, and educational difficulties) into adulthood (Burke, Rowe, & Boylan, 2014). However, it remains unclear whether irritability or defiance may be most directly associated with academic functioning, thereby limiting targeted prevention efforts.

Associations with depressive symptoms.

Children with ADHD are more likely to exhibit depressive symptoms than typically developing peers, and they are at an increased risk of developing depression in adolescence and adulthood (Erskine et al., 2016; Meinzer, Pettit, & Viswesvaran, 2014). Additionally, children and adolescents with co-occurring ADHD and depression experience more impairment than youth affected by either disorder alone (Meinzer et al., 2014). Research suggests the association between ADHD and depression may vary across subtypes of ADHD, with multiple studies finding that inattention, but not hyperactivity-impulsivity, is associated with internalizing problems across developmental periods (Hinshaw, 1994; Lahey & Carlson, 1991; Lahey et al., 1987).

Similarly, depression-ODD comorbidity exists at greater-than-chance levels, and longitudinal studies show that ODD typically precedes depression in preschool-through high school-age youth (Boylan et al., 2007; Burke, Hipwell, & Loeber, 2010). In fact, ODD during middle childhood is a strong predictor of depression at age 18 in boys after accounting for other forms of psychopathology, including depression (Burke et al., 2005). Among ODD symptom dimensions, only irritability appears to predict depression across development, whereas defiance is not associated with internalizing problems (e.g., Burke, Hipwell, & Loeber, 2010; Rowe et al., 2010; Evans et al., 2017). Disentangling the relative contribution of ADHD/ODD symptom dimensions to depressive symptoms during middle childhood may have important implications for curtailing the developmental progression to clinically significant symptoms during adolescence, when rates of depression peak (Merikangas et al., 2010).

Associations with peer rejection and victimization.

ADHD symptoms are linked to both peer rejection (Bagwell et al., 2001; Diamantopoulou, Henricsson, & Rydell, 2005; Pardini & Fite, 2010) and victimization (Mitchell et al., 2016; Sciberras, Ohan, & Anderson, 2012; Taylor et al., 2010; Wiener & Mak, 2009) during middle childhood and adolescence. Similarly, ODD symptoms have been consistently associated with peer rejection (Evans et al., 2016; Pardini & Fite, 2010) and victimization (Fite et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2016; Sciberras et al., 2012) during middle childhood and adolescence. Social impairments linked to ADHD and ODD symptoms appear to emerge early in childhood (e.g., Stengseng et al., 2016; Verlinden et al., 2015) and may persist across the lifespan. For example, adolescents diagnosed with ADHD in childhood were found to have fewer close friends and greater peer rejection than those without a history of ADHD, regardless of whether they still met diagnostic criteria (Bagwell et al., 2001). Similarly, Burke and colleagues (2014b) found that childhood ODD symptoms predicted poor peer, parental, and romantic relationships, fewer friendships, and work-related problems in young adulthood.

The preponderance of evidence suggests that ODD and ADHD symptoms confer risk for both physical (e.g., physical attacks or threats) and relational (e.g., ostracism, rumor spreading) forms of victimization among children and adolescents (Fite et al., 2014; Sciberras et al., 2012; Wiener & Mak, 2009), but little is known about how specific symptom dimensions relate to peer rejection and victimization. Waschbusch, Andrade, and King (2006) suggest that the social problems experienced by inattentive children might be accounted for by their difficulty attending to social cues. Indeed, cross-sectional evidence indicates that inattention, but not hyperactivity-impulsivity, is related to lower peer acceptance in children and adolescents (Becker et al., 2015; Scholtens et al., 2012). Still, hyperactivity-impulsivity may increase risk for peer rejection and victimization through aggressive and impulsive behaviors (Evans et al., 2015; Nijmeijer et al., 2008). Similarly, irritable and defiant children may provoke conflict and be perceived as aversive by their peers. Cross-sectionally, irritability and defiance were both related to relational victimization and peer rejection, but only irritability was uniquely linked to physical victimization among school-age children (Evans et al., 2016). Youth develop foundational social skills during early and middle childhood that set the stage for increasing social demands as they enter adolescence. Considering the potential long-term effects of ODD/ADHD on social functioning (Bagwell et al., 2001; Burke et al., 2014b), research is needed to understand the associations between ODD/ADHD symptoms and peer rejection and victimization to inform assessment and intervention efforts.

The Present Study

In summary, the literature shows that childhood symptoms of ODD and ADHD are associated with academic performance, depressive symptoms, peer rejection, and peer victimization, with important implications for adolescent and adult outcomes. Previous evidence is limited by failing to examine these symptoms as continuous dimensions in relation to one another, within and across diagnoses. Examining the developmental sequelae of inattention, hyperactivity-impulsivity, irritability, and defiance may advance assessment, prevention, and intervention by clarifying the developmental pathways from ADHD and ODD symptom dimensions to psychosocial outcomes. To our knowledge, no studies have prospectively considered the outcomes of ODD and ADHD dimensions simultaneously. Given these gaps, we examined the four ODD/ADHD dimensions as predictors of social, emotional, and academic trajectories throughout elementary school. This developmental period, from grades K-2 through 3-5, is critical for early identification and intervention for behavioral, academic, and social problems.

Based on the research reviewed above, and adopting a developmental psychopathology framework, we put forth general hypotheses regarding the relative effects of symptom dimensions in predicting typical vs. atypical trajectories in social-emotional and academic domains. It was expected that relative to ODD, ADHD symptom dimensions would have more robust and persistent effects on academic performance, with inattention being more prominent than hyperactivity-impulsivity. Additionally, we expected the dimensions of ODD-irritability and ADHD-inattention to increase risk for depressive symptoms over time. Regarding the peer rejection and victimization, the mixed evidence and theoretical arguments did not support specific hypotheses; rather, this study sought to help clarify which disruptive behavior dimensions might confer the most risk for these outcomes over time.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

This study was conducted at an elementary school in a small town in the U.S. Midwest, with teachers and students comprising our sample. Data were collected on seven occasions over 4 school-years from fall 2012 to spring 2016 (all semesters except spring 2013). Of 379 students enrolled in mainstream K-2 classes at baseline, teacher-report data were obtained for 91.3% (N=346; ages 5-8; 51% female), including 90.1% (n=109) of eligible kindergartners, 84.1% (n=111) of 1st graders, and 100.0% (n=126) of 2nd graders. Teacher-rated ODD/ADHD symptoms were collected at baseline, and peer rejection, physical and relational victimization, academic functioning, and depressive symptoms were collected at baseline and all subsequent occasions. Converging measures (self-report and school records) were collected 3 years after baseline, when students were in grades 3-5 and self-report measurement became developmentally appropriate. School records were matched to study ID numbers then de-identified prior to sharing with the research team. Aggregate school data from the baseline year (sample grades K-2) indicate that 21% of students self-identified as being from an ethnic/racial minority or multiracial background (9% Black/African-American, 2% Asian/Asian-American, 6% Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 4% Native American; 5% Hispanic ethnicity) and that 35% were eligible for free or reduced lunch. Census records for the community during the same year showed a middle-class community with a median per capita income of $26,679 and median household income of $65,197.

Teacher data were collected in the last 2 months of each semester. Participating teachers rated their students on brief measures via online survey, earning up to $50-65 per semester. Student data were collected at the end of their 3rd-5th grade fall semester, roughly concurrent with teacher-report data collection for that occasion. Students earned small prizes (colorful pencils) for their participation. Self-report measures were read aloud by trained research assistants while students followed along with paper and pencil. Teachers and non-participating students were absent from classrooms during administration. All procedures were approved by the researchers’ institutional review board as well as the school’s administrators. Teacher and parent consent and youth assent were collected prior to data collection.

Across variables and occasions, missing data rates averaged 13.0% for teacher-report measures (T1-T7: 0, 9, 15, 15, 25, 18, and 18%), 32.4% for each self-report measure, and 18.5% for GPA data. T-tests (with unequal variances where indicated by Levine’s test p<.05) were used to explore the possibility of response or selection bias by comparing those with vs. without self-report data on gender, grade, and teacher-reported measures at all occasions. Missing self-report data at T6 was associated with lower teacher-reported academic performance at both T1 (M[SD]: 3.13[1.19] vs. 3.38[1.09], t(343)=−1.988, p=.048) and T3 (3.27[1.06] vs. 3.57[1.05], t(293)=−2.085, p=.038). Although this is some evidence of possible selection bias, the overall pattern (ps >.103 on 39 of 41 comparisons) suggested that missingness did not appear linked to participant characteristics in a manner that was longitudinally consistent or exceeding what might be expected due to chance.

Measures

ODD/ADHD symptoms (teacher).

Teachers rated students’ ODD/ADHD symptoms using the Disruptive Behavior Disorder Checklist (DBDC; Pelham et al., 1992). The DBDC assesses DSM symptoms for ODD (8 items) and ADHD (18 items). Teachers rated items on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 4 (Very much). For the current study, mean scores reflecting the two previously established ODD dimensions (Burke et al., 2014a; Evans et al., 2017), irritability and defiance, were computed. Irritability was measured with three items (touchy; angry; temper) and defiance with five (argues; defies; blames; annoys; spiteful). Similarly, hyperactivity-impulsivity and inattention mean scores were averaged from 9 items assessing inattention (e.g., often easily distracted, often has difficulty sustaining attention), and 9 items assessing hyperactivity-impulsivity (e.g., often fidgets with hands or squirms in seat, often interrupts or intrudes on others). Internal consistency was good for irritability (α=.86), defiance (α=.89), inattention (α=.96) and hyperactivity-impulsivity (α=.95).

Academic performance (teacher, school records).

Teachers rated students on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Well below average) to 5 (Well above average) for two items reflecting performance compared to other individuals in their class and in their grade and for another item relative to a 5-point letter grade scale ranging from 1=F to 5=A. Thus, higher scores reflected better academic performance. Similar procedures have demonstrated reliability and validity in earlier work (e.g., Evans et al., 2016; Evans & Fite, 2018). Across occasions, teacher-rated academic performance showed excellent internal consistency (αs=.92-.96). As a converging academic measure, we computed students’ fall semester grade-point averages (GPAs) based on all available school records from when they were in grades 3-5. GPA was calculated by averaging grades across five core subjects (math, science, reading, language arts, and social sciences) over the two quarters of the fall semester. This method provides a composite index of overall academic functioning that is sensitive to inter-individual variability, ecologically valid, and corresponds to student academic records collected roughly concurrently with the timing of teacher- and student-report data collection at T6. A standard 4-point GPA scale was used, such that A=4.0, B=3.0, with “plus-minus” grading translated as +/− 0.3 points (e.g., A+=4.3, B-=2.7).

Depressive symptoms (teacher, youth).

Teachers completed the 8-item Withdrawn-Depressed scale of the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Items include behavioral signs of depression (e.g., sadness) and social withdrawal (e.g., prefers to be alone). Previous psychometric evaluations have found excellent reliability and validity (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). As a converging measure, students completed the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Angold et al., 1995) during their 3rd-5th grade year. This scale consists of 13 items including cognitive (e.g., nobody really loved me) and behavioral indicators (e.g., cried a lot) of depression. Students rated items from 0 (Not true) to 2 (True) regarding the past 2 weeks. Mean scores were computed by averaging the 8 and 13 items, respectively. Internal consistency was good for both teacher- (αs=.87-.90) and youth- (α=.89) report.

Peer rejection (teacher, youth).

Peer rejection was assessed using four parallel items drawn from the TRF (teacher-report) and the Youth Self Report form (self-report; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). These items measure students’ experiences with social rejection and peer difficulties (e.g., gets teased, not liked by others) over the past 6 months. These brief scales have exhibited evidence for convergent, divergent, and criterion-related validity in conjunction with other measures of peer interactions by both teacher- and youth-report (e.g., Evans et al., 2016; Fite et al., 2013a). Items were rated on a scale from 1 (Not true) to 3 (Very or often true) and averaged for analyses. The teacher (αs =.78-.90) and student (α=.72) versions of this measure showed acceptable internal consistency.

Peer victimization (teacher, youth).

Experiences of peer victimization were assessed using teacher- and self-reports. Teachers completed a modified version of the six-item Social Experiences Questionnaire – Teacher Report (Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005) for each student in their classroom. As a converging measure, students completed the nine-item Victimization of Self scale of the Peer Experiences Questionnaire (Dill et al., 2004). Both scales assess for physical (e.g., getting hit, kicked or punched) and relational (e.g., getting ignored by others, kids spreading rumors) victimization. Teachers (1=Never to 5=Almost Always) and students (1=Never to 5=Several Times a Week) responded on a five-point scale. These measures have previously demonstrated good psychometric properties (Dill et al., 2004; Williford, Fite, & Cooley, 2015). Physical and relational victimization mean scores were calculated for each respondent. Internal consistency was adequate for teacher relational (αs=.76-.89), teacher physical (αs=.79-.96), student relational (α=.85), and student physical (α=.77).

Analytic Plan

Prior to exploring the effects of ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions, unconditional latent growth curve (LGC) models were estimated to identify which one fit the data best. These sequences began with a latent intercept, then adding linear, quadratic, and cubic slope terms. Higher-order terms were added with and without random variance to assess inter-individual variability around the average pattern. These nested LGC models were evaluated through consideration of (a) the Satorra-Bentler chi-square (SB-χ2) difference test, appropriate for robust estimation; (b) predictive fit indices, including the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), and sample-adjusted BIC (SABIC); (c) relative fit indices, including the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI); and (d) absolute fit indices, the Root Mean Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Models are considered to have adequate/good fit when CFI and TLI ≥.90/.95, RMSEA and SRMR ≤.08/.05; and comparison models show improved fit over nested models when the SB-χ2 test is significant and when more complex models no longer produce decrements in predictive fit indices. The best-fitting LGC models were then re-estimated to explore covariate effects (grade, gender).

Only victimization was measured as a two-dimensional construct, consisting of relational and physical types. Accordingly, a bivariate LGC model was used, with growth terms for relational and physical victimization added simultaneously in the modeling sequence. Covariances were estimated between residuals of co-occurring observations of different variables (e.g., T1 relational with T1 physical), as well as for corresponding growth terms (e.g., physical intercept with relational intercept). By examining both victimization types in the same model, results elucidate their trajectories individually (accounting for the other) and collectively (e.g., cross-type correlations).

Of central interest were the conditional LGC models examining the four ODD/ADHD dimensions as predictors of teacher-reported outcome trajectories. Specifically, these models explored irritability, defiance, inattention, and hyperactivity-impulsivity in terms of their unique effects on each outcome’s (a) baseline levels at grades K-2 (latent intercepts at T1), (b) patterns of change over time (linear slopes), and (c) longer-term outcomes when children were in grades 3-5 (latent intercepts at T6; corresponding to converging measure models). To ascertain whether these effects were truly robust and not artifacts of multicollinearity, we employed a hierarchical/sensitivity modeling sequence. In Model 1, each dimension was entered individually with covariates to identify its basic association with intercepts and slopes (i.e., four models). In Model 2, the dimensions were aggregated by disorder, combining irritability with defiance and inattention with hyperactivity-impulsivity (i.e., two models). In Model 3, all four dimensions were aggregated together along with covariates (i.e., one final model). Thus, coefficients that remain significant in the same direction across all three models can be confidently viewed as robust, revealing which dimension shows unique effects on what outcome variables, and at what time point.

The converging outcome models followed a similar approach, using multivariate regression models to examine 3rd-5th grade outcomes only. Teacher-rated ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions at T1 were examined as predictors of GPA records and child-reported depressive symptoms, peer rejection, and victimization at T6 (grades 3-5). Like the teacher LGC models, these models included covariates (gender, grade) and followed the same three-model sequence to clarify which ODD/ADHD dimension effects were unique and robust. Unlike the teacher LGC models, it was not possible to control for baseline levels given that the children were in grades K-2 at that time, precluding self-report. Thus, the converging models were estimated with and without adjusting for teacher-reported levels of corresponding baseline variables.

Models were estimated in Mplus Version 8. Students’ clustering by different classrooms/teachers each year was not specified due to the prohibitive complexity of cross-classified models with four different data structures. Rather, the effects of cross-classified dependencies were mitigated (a) through a multi-wave latent variable modeling framework (with growth terms based on 7 ratings by 4 teachers over 8 semesters), (b) by allowing residual terms to co-vary for observations collected within the same school-year, and (c) through a series of sensitivity analyses.1 Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used to accommodate for non-normality and missing data.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations of interest are presented in Table 1, with further univariate and longitudinal characteristics provided in the Supplement. As expected, data showed moderate departures from normality (generally, skewness <|3.0| and kurtosis <|8.0|) with varying degrees of teacher/classroom-related dependencies (Mdn ICC=.09). All four ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions were more common among boys than girls, while only defiance was significantly (negatively) associated with grade. Zero-order correlations were high within and across the dimensions of ODD and ADHD. This high covariation was expected and controlled for in subsequent models by adding terms hierarchically and interpreting results across models. Multicollinearity was within an acceptable range for all four symptom dimensions across all LGC and regression models (tolerance<0.42; VIF<4.99).2 Boys had higher levels of irritability, defiance, inattention, hyperactivity-impulsivity, physical victimization, and peer rejection. Girls had higher GPAs, but teacher-rated academic performance was not correlated with gender. Defiance was higher among students in younger grades. No other variables showed consistent correlations with gender or grade level. The stability of repeated measures and their zero-order associations with baseline ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions varied across outcomes and occasions (see Table 1 and Supplement).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables across all occasions

| Variable/Time a (Grade Levels) | Univariate b |

Baseline Variables (T1) |

Repeated Measures |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7T1 | 8T2 | 9T3 | 10T4 | 11T5 | 12T6 | ||

| Baseline Variables (Teacher-Report at T1) | ||||||||||||||

| 1. | Female1 (K-2) | -- | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 2. | Grade1 (K-2) | 1.05 (0.82) | .04 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 3. | Irr1 (K-2) | 1.32 (0.63) | −.26** | −.09 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 4. | Def1 (K-2) | 1.28 (0.54) | −.19** | −.11* | .86** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 5. | Ina1 (K-2) | 1.56 (0.75) | −.29** | .06 | .51** | .57** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 6. | Hyp1 (K-2) | 1.49 (0.72) | −.28** | −.09 | .63* | .70** | .77** | 1.00 | ||||||

| Repeated Measures (Teacher-Report at T1-T7) | ||||||||||||||

| 7. | Aca1 (K-2) | 3.30 (1.13) | .10 | −.02 | −.11* | −.10 | −.42** | −.28** | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. | Aca2 (1-3) | 3.48 (1.10) | .09 | .14* | −.11* | −.10 | −.35** | −.24** | .66** | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. | Aca3 (1-3) | 3.50 (1.06) | .04 | .09 | −.11 | −.11 | −.37** | −.22** | .64** | .83** | 1.00 | |||

| 10. | Aca4 (2-4) | 3.54 (1.07) | .07 | .10 | −.11 | −.12* | −.39** | −.26** | .62** | .73** | .71** | 1.00 | ||

| 11. | Aca5 (2-4) | 3.56 (1.03) | .08 | .08 | −.10 | −.12 | −.40** | −.28** | .61** | .73** | .71** | .87** | 1.00 | |

| 12. | Aca6 (3-5) | 3.65 (0.95) | .14* | .06 | −.16** | −.19** | −.46** | −.31** | .57** | .63** | .63** | .71** | .70** | 1.00 |

| 13. | Aca7 (3-5) | 3.66 (1.00) | .17** | −.03 | −.17** | −.22** | −.44** | −.32** | .66** | .63** | .72** | .71** | .86** | |

| 7. | Dep1 (K-2) | 1.16 (0.32) | .00 | .12* | .24** | .16** | .26** | .08 | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. | Dep2 (1-3) | 1.24 (0.38) | −.05 | .03 | .05 | .04 | .17** | .07 | .27** | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. | Dep3 (1-3) | 1.26 (0.40) | −.05 | .11 | .05 | .03 | .18** | .07 | .27** | .73** | 1.00 | |||

| 10. | Dep4 (2-4) | 1.22 (0.38) | .05 | −.13* | .14* | .18** | .20** | .16** | .24** | .31** | .30** | 1.00 | ||

| 11. | Dep5 (2-4) | 1.19 (0.33) | −.12 | −.02 | .10 | .14* | .16** | .12 | .25** | .24** | .27** | .75** | 1.00 | |

| 12. | Dep6 (3-5) | 1.18 (0.34) | .10 | −.07 | .19** | .21** | .20** | .10 | .23** | .28** | .29** | .36** | .35** | 1.00 |

| 13. | Dep7 (3-5) | 1.17 (0.32) | −.11 | −.05 | .18* | .16** | .17** | .07 | .29** | .27** | .32** | .37** | .48** | .72** |

| 7. | Rej1 (K-2) | 1.11 (0.28) | −.15** | −.04 | .75** | .78** | .50** | .60** | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. | Rej2 (1-3) | 1.16 (0.32) | −.06 | .02 | .22** | .28** | .32** | .40** | .30** | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. | Rej3 (1-3) | 1.20 (0.37) | −.09 | .00 | .28** | .36** | .35** | .41** | .36** | .75** | 1.00 | |||

| 10. | Rej4 (2-4) | 1.13 (0.30) | −.12* | −.04 | .30** | .35** | .34** | .41** | .30** | .37** | .39** | 1.00 | ||

| 11. | Rej5 (2-4) | 1.16 (0.36) | −.04 | .00 | .22** | .28** | .26** | .33** | .21** | .38** | .41** | .66** | 1.00 | |

| 12. | Rej6 (3-5) | 1.17 (0.36) | −.15** | .00 | .28** | .34** | .33** | .32** | .35** | .34** | .44** | .38** | .34** | 1.00 |

| 13. | Rej7 (3-5) | 1.19 (0.40) | −.15* | .00 | .23** | .28** | .24** | .26** | .28** | .31** | .38** | .30** | .19 | .60** |

| 7. | RVic1 (K-2) | 1.17 (0.45) | −.09 | .07 | .50** | .46** | .45** | .40** | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. | RVic2 (1-3) | 1.30 (0.62) | .04 | −.03 | .09 | .17** | .21** | .22** | .05 | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. | RVic3 (1-3) | 1.46 (0.71) | .09 | −.17** | .09 | .16** | .14* | .15** | .03 | .61** | 1.00 | |||

| 10. | RVic4 (2-4) | 1.15 (0.41) | .13* | .01 | .19** | .22** | .14* | .18** | .19** | .13* | .09 | 1.00 | ||

| 11. | RVic5 (2-4) | 1.25 (0.57) | .10 | .06 | .11 | .15* | .23** | .31** | .07 | .23** | .19** | .41** | 1.00 | |

| 12. | RVic6 (3-5) | 1.22 (0.53) | .02 | .09 | .05 | .11 | .12 | .14* | .00 | .14* | .17** | .12 | .19** | 1.00 |

| 13. | RVic7 (3-5) | 1.30 (0.60) | .08 | .16** | .03 | .10 | .09 | .15* | .06 | .14* | .25** | .02 | .21** | .66** |

| 7. | PVic1 (K-2) | 1.15 (0.38) | −.29** | −.05 | .62** | .56** | .53** | .55** | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. | PVic2 (1-3) | 1.12 (0.32) | −.22** | −.14* | .13* | .22** | .19** | .19** | .15** | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. | PVic3 (1-3) | 1.24 (0.47) | −.25** | −.34** | .17** | .22** | .16** | .26** | .23** | .62** | 1.00 | |||

| 10. | PVic4 (2-4) | 1.04 (0.19) | −.21** | −.15** | .15* | .15* | .06 | .17** | .04 | .06 | .27** | 1.00 | ||

| 11. | PVic5 (2-4) | 1.05 (0.23) | −.15* | −.02 | .03 | .06 | .16* | .29** | .12 | .03 | .09 | .12* | 1.00 | |

| 12. | PVic6 (3-5) | 1.07 (0.26) | −.16** | .07 | .13* | .16** | .12 | .16** | .10 | .13* | .12* | .04 | .19** | 1.00 |

| 13. | PVic7 (3-5) | 1.08 (0.28) | −.26** | .08 | .20** | .26** | .25** | .34** | .27** | .25** | .27** | .12* | .26** | .57** |

| Converging Outcome Measures (Child-Report and School Records at T6) c | ||||||||||||||

| 12. | CRej6 (3-5) | 3.74 (0.54) | −.01 | −.01 | .02 | .04 | .20** | .11 | .07 | .18** | .13* | .25** | .24** | .26** |

| 12. | CDep6 (3-5) | 0.41 (0.42) | .03 | .12 | .05 | .07 | .19** | .10 | .08 | −.06 | −.05 | .02 | .11 | −.02 |

| 12. | CRVic6 (3-5) | 1.37 (0.45) | −.05 | −.06 | .12 | .16* | .28** | .19** | .18** | .09 | .19** | .07 | .14* | .29** |

| 12. | CPVic6 (3-5) | 1.46 (0.70) | −.10 | −.08 | .14* | .20** | .26** | .18** | .21** | .06 | .16* | .06 | .07 | .08 |

| 12. | RGPA6 (3-5) | 1.40 (0.62) | .12* | −.37** | −.14* | −.19* | −.41** | −.26** | .40** | .38** | .37** | .46** | .46** | .50** |

Note.

Note. All variable names are suffixed with numbers representing the measurement occasion (T1-T7) followed by the cohort’s current grade level in parentheses (kindergarten through fifth grade [K-5]). Note that T1, T2, T4, and T6 are fall semester occasions; all others are spring.

Of the univariate characteristics, only means and standard deviations are reported here for clarity; see Table S1 for a full reporting (count, range, skewness, kurtosis, scale consistency, teacher/classroom ICCs).

Variables are prefixed to indicate method—child report (C) or school records (R). Italicized coefficients denote cross-method correlations among child-report and school records variables at T6 and the corresponding teacher-reported variables from T1-T6 (T1 was used in adjusted regression models, Table 3).

Irr=irritability, Def=defiance, Hyp=hyperactivity-impulsivity, Ina=Inattention, Aca=academic performance, Dep=depressive symptoms, Rej=peer rejection, RVic=relational victimization, PVic=physical victimization, GPA=grade-point average.

p<.05,

p<.01.

Unconditional LGC Models and Covariate Effects

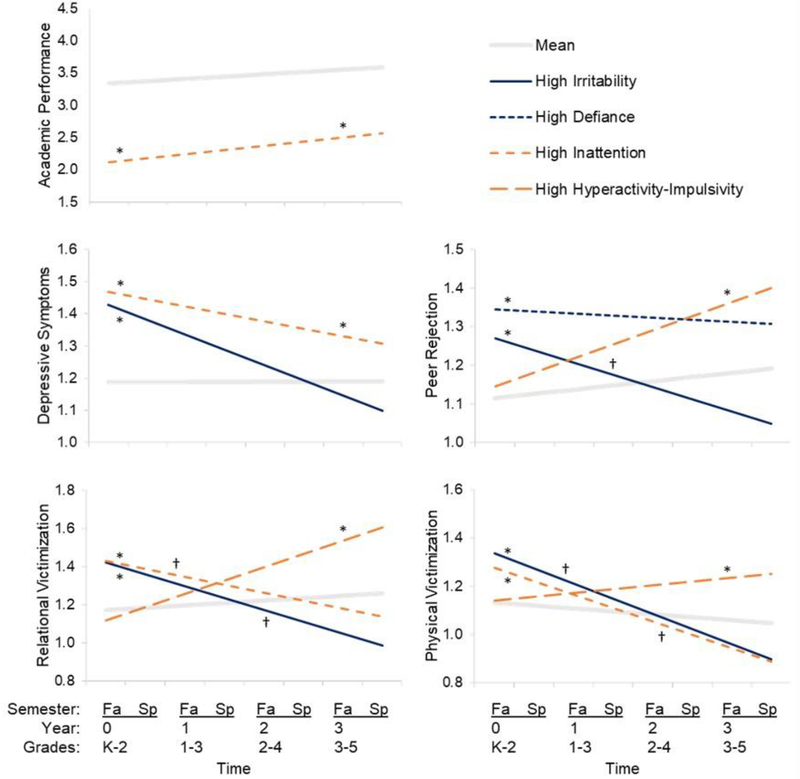

The full model-building sequence is described in the Supplement, with model fit statistics reported in Table S2. In short, the best-fitting models specified variable linear slopes (random effects) for academic performance and depressive symptom, and constrained linear slopes (fixed effects) for peer rejection and victimization. The average growth trajectories are briefly summarized as follows (all estimates p<0.05) and plotted in light gray in Figure 1 (as estimated in later conditional models).

Figure 1. Model-estimated trajectories at high levels of ODD (dark blue) and ADHD (orange) symptom dimensions, compared to average trajectories (light gray).

Note. For clarity, trajectories are only presented if the symptom dimension was found to have a significant effect on the baseline intercept, slope, or 3-year intercept (*p<.05 effect on intercept; †p<.05 effect on slope). Effects from Model 3 models are presented here, only if they were robust across models (i.e., also significant in the same direction in Models 1 and 2). High-symptom trajectories represent individuals at two standard deviations above the mean (i.e., clinically significant levels) on the specified variable and at the mean (i.e., normative levels) of all other variables. Average trajectories are mean-centered on all variables, thus serving as a common basis of comparison for all high-symptom trajectories. Models control for the effects of grade level, gender, and other ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions.

On average, academic performance began slightly above the scale’s midpoint (intercept=3.34) at baseline and improved slowly over time (slope=0.07), with significant inter-individual variability in scores and rates of change. Depressive symptoms started low at baseline (intercept=1.19) and showed intra-individual stability over time (slope ns), but with significant inter-individual variability around both the intercept and slope. Similarly, peer rejection levels began low (intercept=1.12) at baseline, with significant inter-individual variability, and then increased significantly (slope=0.02) with negligible slope variability. In the unconditional bivariate model for peer victimization, relational and physical intercepts were highly correlated (r=.59) and their slopes showed negligible variability. Levels of victimization were similarly low at baseline (relational intercept=1.16; physical intercept=1.12), but relational victimization increased over time (slope=0.03) while physical victimization decreased (slope=−0.02). Regarding covariates, girls had lower initial peer rejection (B=−0.07) and physical victimization (B=−0.15) but showed no difference in relational victimization. Over time, the gender discrepancy in peer rejection remained stable, but boys showed a slower rate of decrease in physical victimization over time (B=0.02) while girls showed a sharper increase in relational victimization (B=0.04). Students in earlier grades had higher initial levels (B=−0.06) and a sharper decrease (B=0.02) in physical victimization than those in later grades. No other significant effects were found for gender or grade.

Conditional LGC Models with ODD/ADHD Symptom Dimensions

Table 2 summarizes the effects of ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions on baseline intercepts (Panel A), linear slopes (Panel B), and 3-year intercepts (Panel C) of all outcome variables across Models 1 (one symptom dimension), 2 (two dimensions from same diagnostic category), and 3 (all four ODD/ADHD dimensions entered together). See Table S2 for model fit statistics. Figure 1 presents the average trajectories of all outcome variables, overlain with the trajectories that would result from elevated symptom dimension levels where effects were significant and robust. Consistent with our developmental psychopathology framework, we plotted trajectories at the mean and 2 SD above the mean on the indicated symptom dimension, thereby presenting the trajectories of two hypothetical cases: (a) a typically developing child, following the average trajectory in light gray; and (b) a child with clinically significant scores on an ODD/ADHD symptom dimension, following a trajectory that departs from the mean. Below, we interpret these results by outcome, emphasizing only those effects that were consistent in all three models (underlined in Table 2 and presented in Figure 1).

Table 2.

ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions in grades K-2 as predictors of teacher-report outcome trajectories

| Predictors (TR at K-2) | Academic Performance | Depressive Symptoms | Peer Rejection | Peer Victimization |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relational | Physical | ||||||||||||||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | |

| A. Baseline Intercept On | |||||||||||||||

| Female | – | – | −.12 | – | – | .06* | – | – | .03+ | – | – | .09* | – | – | −.08*** |

| Grade | – | – | .17** | – | – | .02 | – | – | .01 | – | – | .01 | – | – | −.04** |

| Irritability | −.15+ | −.18 | −.18 | .12*** |

.18** |

.19*** |

.31*** |

.13** |

.12** |

.29*** |

.18* |

.20* |

.22*** |

.15* |

.16* |

| Defiance | −.14 | .04 | .65** | .09** | −.09 | −.12 | .37*** |

.25*** |

.21*** |

.31*** | .14 | .04 | .23*** | .09 | .01 |

| Inattention | −.57*** |

−.78*** |

−.82*** |

.12*** |

.19*** |

.19*** |

.18*** | .05 | .03 | .23*** |

.18** |

.17** |

.16*** |

.10** |

.10** |

| Hyper-Imp | −.39*** | .22+ | .01 | .05+ | −.10** | −.14*** | .22*** | .18*** | .02 | .20*** | .06 | −.04 | .16*** | .08+ | .01 |

| B. Linear Slope On | |||||||||||||||

| Female | – | – | .03 | – | – | −.03** | – | – | −.02 | – | – | .02 | – | – | .00 |

| Grade | – | – | −.03 | – | – | −.01+ | – | – | .00 | – | – | .02 | – | – | .02* |

| Irritability | −.00 | .09+ | .08+ | −.02+ | −.07** | −.08** | −.07*** |

−.07** |

−.07** |

−.07*** |

−.11** |

−.12** |

−.07*** |

−.07** |

−.08** |

| Defiance | −.03 | −.12* | −.15* | −.00 | .07** | .08** | −.07*** | −.00 | −.03 | −.06* | .05 | .04 | −.07*** | .00 | .02 |

| Inattention | .02+ | .03 | .04 | −.02 | −.03 | −.03+ | −.02 | −.01 | −.01 | −.04* |

−.07* |

−.07* |

−.05*** |

−.06** |

−.06** |

| Hyper-Imp | .00 | −.02 | .01 | −.01 | .02 | .02 | −.02 | −.01 | .04+ | −.01 | .05 | .08* | −.03** | .01 | .04+ |

| C. 3-Year Intercept On | |||||||||||||||

| Female | – | – | −.04 | – | – | −.04 | – | – | −.02 | – | – | .15*** | – | – | −.08*** |

| Grade | – | – | .08 | – | – | −.02 | – | – | .01 | – | – | .06* | – | – | .02 |

| Irritability | −.16+ | .09 | .07 | .05+ | −.04 | −.04 | .11** | −.08 | −.08 | .08* |

−.14* | −.15* | .02 | −.07+ | −.08+ |

| Defiance | −.24* | −.33+ | .20 | .08* | .12 | .13 | .17*** | .24** | .12 | .16** | .30** | .17 | .06* | .12* | .07 |

| Inattention | −.57*** |

−.69*** |

−.70*** |

.07** |

.11* |

.09* |

.13*** | .02 | .01 | .13*** | −.03 | −.04 | .03 | −.07 | −.07+ |

| Hyper-Imp | −.38*** | .16 | .03 | .03 | −.05 | −.09* | .16*** |

.15** |

.13* |

.18*** |

.20** |

.20** |

.07** |

.13** |

.13** |

Note. Values are unstandardized regression coefficients. M1, M2, M3 = Models 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In Model 1, four models were estimated separately, one for each substantive predictor. In Model 2, two models were estimated, with ODD dimensions (irritability, defiance) in one model and ADHD dimensions (inattention, hyperactivity) in another. In Model 3, one model was estimated with all terms combined. Covariates (female, grade) are only reported for Model 3 because their values vary across earlier models. Underlining denotes significance in the same direction across all three models. TR=teacher-report. Hyper-Imp=hyperactivity-impulsivity.

p<.1,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Academic performance.

Results of the three academic performance models showed that only inattention robustly predicted lower levels of academic performance at grades K-2 (see Table 2, Panel A), and this effect persisted to grades 3-5 (Panel C). Hyperactivity-impulsivity and defiance (but not irritability) showed signs of associations with academic performance at one or both of these occasions, but both were attenuated to nonsignificance when controlling for other symptom dimensions. Similarly, there were no robust effects on the linear slope over time (Table 2, Panel B). To summarize, these models revealed a pronounced and persistent effect of inattention predicting poorer academic performance over time, whereas the effects of hyperactivity-impulsivity, irritability, and defiance were all inconsistent or nonsignificant depending on what other symptom dimensions were included in the model (see Figure 1).

Depressive symptoms.

Across all three models, high levels of irritability were robustly associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms at grades K-2 (Table 2, Panel A), but this effect did not persist 3 years later at grades 3-5 (Panel C). Defiance was associated with depressive symptoms at grades K-2 and 3-5, but these effects were attenuated when irritability was added in Model 2. Inattention was a robust predictor of elevated depressive symptoms at both occasions, again revealing a lasting effect. No other ODD/ADHD symptom effects on intercepts or slopes were found to be significant and robust across models. In sum (as shown in Figure 1), only inattention and irritability uniquely predicted depressive symptoms concurrently, and only inattention predicted them longitudinally.

Peer rejection.

Irritability was robustly associated with the baseline intercept and slope for peer rejection but not with the 3-year intercept. That is, irritable children had higher levels of peer rejection in grades K-2 (Table 2, Panel A), and this irritability predicted less positive linear change in peer rejection relative to the average, increasing trajectory (Panel B), leading to 3-year outcomes that were not different from the mean after controlling for other ODD/ADHD symptoms (Panel C). Similarly, defiance also showed robust, unique associations with peer rejection at grades K-2, but again this effect did not persist to grades 3-5. Although hyperactivity-impulsivity and inattention both showed signs of association with peer rejection at grades K-2 and 3-5, these effects were mostly attenuated when controlling for irritability and defiance, with one exception: hyperactivity-impulsivity emerged as the sole robust predictor of elevated peer rejection 3 years later at grades 3-5. Overall, all ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions showed some evidence of association with peer rejection; in terms of robust effects, however, only irritability and defiance showed unique cross-sectional associations with peer rejection, whereas only hyperactivity-impulsivity uniquely predicted peer rejection longitudinally (see Figure 1).

Peer victimization.

In the bivariate victimization model, similar patterns were found for both relational and physical victimization (see Table 2 and Figure 1). Irritability robustly showed positive associations with K-2 intercepts for relational and physical victimization (Table 2, Panel A), negative associations with their linear slopes (Panel B), and no associations with their 3-year intercepts (Panel C). That is, children with high irritability in grades K-2 also had higher concurrent victimization of both forms, but then followed trajectories of relative decline (compared to the average trajectories), and irritability’s effects on victimization did not persist to grades 3-5 (some coefficients remained significant, but their directionality changed across Models 1-3). Inattention followed a parallel pattern, emerging as a significant robust predictor of relational and physical victimization at grades K-2 but not at grades 3-5, predicting a pattern of relative decline in the interim. In contrast, hyperactivity-impulsivity was not robustly associated with the K-2 intercept or slope of either victimization type, but emerged as the only robust predictor of higher levels of relational and physical victimization in grades 3-5. In sum, and similar to the peer rejection results, all ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions showed some associations with greater levels of relational and physical aggression; however, only inattention and irritability showed robust cross-sectional links to victimization (both forms) at grades K-2, and only hyperactivity-impulsivity was robustly longitudinally predictive of greater victimization in grades 3-5.

Converging Models: Self-Report Measures and GPA at Grades 3-5

Results of regression models predicting child-reported and GPA outcomes are presented in Table 3. Again, results that remained robust across models 1-3 are emphasized. In the unadjusted models (without controlling for baseline teacher-report), only inattention robustly predicted these converging 3-year outcomes. Children with higher levels of teacher-reported inattention in grades K-2 had significantly lower GPAs, higher depressive symptoms, and higher peer rejection in grades 3-5. These associations were robust after controlling for teacher report at baseline in the adjusted models (Table 3, bottom panel). Associations with victimization were less consistent. Teacher-reported inattention robustly predicted relational victimization in grades 3-5 in the unadjusted models, but this effect was attenuated to marginal significance when adjusted to control for baseline teacher-report. Regarding physical victimization, no ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions were significant and robust, but inattention clearly trended in that direction (significant in Unadjusted Models 1-2 but marginal in 3). No unique effects of irritability, defiance, or hyperactivity-impulsivity were found on any self-report/GPA outcomes.

Table 3.

ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions in grades K-2 as predictors of converging outcome measures 3 years later

| Predictors (TR at K-2) | Overall GPA (School Records) | Depressive Symptoms (Child-Report) | Peer Rejection (Child-Report) | Peer Victimization (Child-Report) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relational | Physical | ||||||||||||||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | |

| Unadjusted Models | |||||||||||||||

| Female | – | – | .04 | – | – | .07 | – | – | .04 | – | – | .04 | – | – | −.05 |

| Grade | – | – | −.23*** | – | – | .05 | – | – | −.02 | – | – | −.07 | – | – | −.07 |

| Irritability | −.11** | .14+ | .09 | .05 | −.03 | −.01 | .01 | −.06 | −.04 | .12 | −.07 | −.04 | .12 | −.14 | −.11 |

| Defiance | −.19*** | −.33*** | −.07 | .07+ | .10 | −.01 | .03 | .09 | −.05 | .18* | .26+ | .03 | .20+ | .34+ | .22 |

| Inattention | −.29*** |

−.33*** |

−.33*** |

.12** |

.16* |

.16* |

.13** |

.19* |

.20* |

.27** |

.33* |

.33* |

.21** | .26* | .22+ |

| Hyper-Imp | −.20** | .06 | .04 | .08+ | −.05 | −.04 | .07+ | −.08 | −.04 | .18* | −.08 | −.07 | .13+ | −.07 | −.11 |

| Adjusted Models a | |||||||||||||||

| Female | – | – | .04 | – | – | .07 | – | – | .03 | – | – | .05 | – | – | −.04 |

| Grade | – | – | −.23*** | – | – | .05 | – | – | −.02 | – | – | −.06 | – | – | −.06 |

| Irritability | −.09* | .14+ | .12 | .04 | −.04 | −.01 | −.05 | −.08 | −.05 | −.08 | −.20 | −.13 | .00 | −.21+ | −.15 |

| Defiance | −.16*** | −.30** | −.17 | .07 | .10 | −.01 | −.03 | .04 | −.07 | .00 | .18 | .03 | .12 | .30 | .22 |

| Inattention | −.20** |

−.22* |

−.20* |

.12** |

.16* |

.16* |

.14* |

.19* |

.19* |

.21* | .28* | .27+ | .17+ | .24+ | .21 |

| Hyper-Imp | −.13* | .02 | .04 | .07+ | −.05 | −.04 | .06 | −.07 | −.04 | .08 | −.11 | −.07 | .07 | −.09 | −.11 |

| Stability 1 a | – | – | .14*** | – | – | −.00 | – | – | .11 | – | – | .07R | – | – | .12P |

| Stability 2 a | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | .26P | – | – | .03R |

Note. Values are unstandardized regression coefficients. M1, M2, M3 = Models 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In Model 1, four models were estimated separately, one for each substantive predictor. In Model 2, two models were estimated, with ODD dimensions (irritability, defiance) in one model and ADHD dimensions (inattention, hyperactivity) in another. In Model 3, one model was estimated with all terms combined. Covariates (female, grade) and stability coefficients are only reported for Model 3 because their values vary across earlier models. Bold denotes significance. Underlining denotes significance in the same direction across all three models. TR=teacher-report. Hyper-Imp=hyperactivity-impulsivity.

Adjusted models control for the corresponding teacher-rated variable (Stability 1) collected at baseline/K-2, such as teacher-rated academic performance for GPA (all other constructs go by the same name). Victimization models also control for the other subtype (Stability 2), identified by superscripts (R=relational, P=physical).

p<.1,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Discussion

Using a developmental psychopathology framework (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2002), we examined teacher-reported symptom dimensions of ODD (irritability, defiance) and ADHD (inattention, hyperactivity-impulsivity) as predictors of multi-informant social, emotional, and academic outcomes across middle childhood. Broadly, results suggest that ODD dimensions—especially irritability—are robustly associated with several concurrent social-emotional difficulties that are acutely elevated but then decline over time. Irritability was linked to depressive symptoms, peer rejection, and both types of victimization in grades K-2, while defiance was uniquely linked to peer rejection; however, none of these effects persisted through grades 3-5. In contrast, ADHD symptom dimensions were uniquely associated with fewer concurrent difficulties but predicted stable and subsequent problems in academic, social, and emotional domains. Inattention predicted lower levels of academic performance and higher levels of depressive symptoms that were stable over time (significant at grades K-2 and 3-5) and higher levels of peer victimization in grades K-2 only. Hyperactivity-impulsivity predicted future peer rejection and victimization in grades 3-5. In converging models, only inattention emerged as a robust predictor of 3-year outcomes, including GPA, depressive symptoms, peer rejection, and relational victimization.

As hypothesized, inattention predicted pronounced, robust, and long-lasting difficulties with academic performance, which is consistent with a large body of evidence spanning developmental periods (e.g., Daley & Birchwood, 2010; Frazier et al., 2007, Pingault et al., 2011). As previous work suggests (Sayal et al., 2015; Semrud-Clikeman, 2012; McGee et al., 1991), academic impairment was uniquely tied to inattention among ADHD symptoms, whereas hyperactivity-impulsivity was unassociated with academic outcomes. While the ADHD-academics link is well-established, this is the first study to our knowledge to document this relation while controlling for all four ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions. Further, this result was corroborated by GPA outcomes. Among children with any form of ODD/ADHD-related difficulties—irrespective of diagnostic status or subtype—it is inattention that seems to most clearly predict whether children in grades K-2 will follow a typical or atypical academic trajectory in middle childhood. From an educational perspective, then, inattention may be an especially important target for intervention within the spectrum of ODD/ADHD symptoms. However, this is not to discount the importance of total ADHD or ODD symptoms (e.g., Burke et al., 2014b).

Partially supporting our hypotheses, inattention and irritability predicted higher teacher-reported depressive symptoms, but only the effect of inattention persisted over time and was also supported by self-report outcomes. This finding converges with evidence demonstrating the equifinality of depression, such that it is an outcome of both inattention (e.g., Humphreys et al., 2013) and irritability (e.g., Vidal-Ribas et al., 2016) from childhood through adulthood. Moreover, this finding contributes to the literature by demonstrating the unique nature of these effects relative to one another. The emotional sequelae of irritability appear to be more acute, whereas inattention more clearly and specifically differentiates a depressive trajectory from the average trajectory. Alternatively, this result may underscore the importance of irritability as being relevant to depression in childhood (APA, 2013).

In the social domain, irritability and defiance were linked to peer rejection while irritability and inattention were linked to both forms of victimization; yet, none of these effects persisted over time. These results correspond to the acute but subsiding effects of ODD dimensions noted above for academics and depressive symptoms. Interestingly, ADHD symptoms predicted persistent and myriad peer difficulties, but outcomes varied by dimensions and informants. Hyperactivity-impulsivity was a robust predictor of teacher-reported peer rejection and victimization (relational and physical) in grades 3-5. This is consistent with research on the peer difficulties experienced by children with ADHD diagnoses and symptoms during middle childhood and adolescence (e.g., Bagwell et al., 2001; Hoza et al., 2005; Weiner & Mak, 2009), with hyperactive-impulsive behaviors thought to be particularly detrimental to peer functioning in school-age youth (Nijmeijer et al., 2008). Notably, these effects were evident by teacher-but not child-report, a finding which is consistent with the positive illusory bias exhibited by children with ADHD with respect to social functioning and other domains (Volz-Sidiropoulou et al., 2016). The longitudinal peer outcomes of inattention were more evident and robust by self-report than by teacher-report. Specifically, inattention predicted higher levels of self-reported peer rejection and relational victimization 3 years later, with a similar trend for physical victimization. Such findings converge with the view that inattention’s social effects may result in impaired friendship and social skill development, which could contribute to peer problems over time (Nijmeijer et al., 2008).

These are among the first data to report peer and academic outcomes of ODD symptom dimensions, and they paint a somewhat less discouraging picture than results from large epidemiological samples (e.g., Rowe et al., 2010; Stringaris & Goodman 2009b), which provide most of the evidence for ODD symptom dimensions to date (Evans et al., 2017). There are several possible explanations for why we did not find robust long-term outcomes of ODD dimensions. First, irritability and defiance are dimensional and context-dependent. In school settings, overall levels and rates of ODD symptoms may be low and linked to current problems but not reliably predicting longer-term outcomes. Still, the lack of persistent effects should not be interpreted as a lack of validity or clinical importance, as other studies have shown ODD (Biederman et al., 2008; Kessler et al., 2012) and related categories (Axelson et al., 2012; Mayes et al., 2015) to have relatively low longitudinal stability, despite clearly warranting clinical attention (Evans et al., 2017). Second, unlike prior research, we focused on the long-term predictive effects unique to each dimension both before and after controlling for all others, thereby ignoring associations that may be significant only when not controlling for symptom overlap (e.g., see results from Model 1 models). A third explanation relates to measurement and historical differences between ODD and ADHD. For decades, ADHD has been defined by 18 indicators which comprise two a priori distinct symptom dimensions. In contrast, ODD is defined by only 8 indicators, which have only recently been separated post hoc into symptom dimensions. Thus, the long-term effects of ADHD dimensions may reflect more sensitive and specific measurement properties for these dimensions as compared to ODD. If true, this would be an artifact of DSM criteria, underscoring the need for alternative assessment methods for irritability and defiance. Finally, results may be partly explained by using teacher-report in a school sample. While ADHD affects children across settings, ODD is often present only in the home/family context (APA, 2013). Thus, teachers may not be ideally situated to assess all ODD/ADHD dimensions equally; rather, they may only identify more severe and pervasive manifestations of ODD symptoms.

Several multi-informant patterns are notable. Teacher LGC and converging regression models showed similar results for inattention and its associations with depressive symptoms, peer rejection, and academic outcomes. In many cases, however, one informant’s assessment of an outcome revealed an association that the others did not. According to self-, but not teacher-, report, inattention predicted subsequent increases in relational and (marginally) physical victimization. Also, hyperactivity-impulsivity predicted increases in peer rejection and relational victimization and more stable patterns of physical victimization according to teacher-, but not self-, report. Perhaps teachers are not noticing the full occurrence of peer victimization, especially those acts that affect children with inattention; indeed, many acts of victimization occur outside of the immediate school context or in locations where adult monitoring is limited (Fite et al., 2013b). Alternatively, it may be that a student with hyperactivity-impulsivity could have interactions with peers that a teacher would identify as rejection/victimization even if the student does not, consistent with the positive illusory bias (Volz-Sidiropoulou et al., 2016).

It is informative to place these findings against a backdrop of normative academic, social, and emotional development. Average levels of oppositional and aggressive behaviors decline in the K-2 period, making it a key window for early identification of those at risk for poor outcomes. Indeed, Figure 1 shows that children with elevated levels of certain teacher-rated ODD/ADHD symptoms in these early grade levels were likely to depart from average trajectories thereafter. The ensuing years between early and late elementary school are a time characterized by social, emotional, and academic skill-building. At the peer level, social ecologies are expanding and crystalizing, and children have increasingly more time without direct adult supervision. In our data, peer rejection and victimization occurred with variability within and across individuals, and ODD/ADHD dimensions accounted for some of that variance. For example, irritability predicted peer functioning trajectories that fell from atypical to typical over time whereas hyperactivity-impulsivity predicted the opposite pattern. Similarly, rates of depression are relatively low in childhood then increase in adolescence. Irritability and inattention could be monitored to identify those at risk for depression before the developmental period where it may become more severe.

In sum, the complex findings resulting from our multi-informant approach, especially as it applies to peer rejection and peer victimization, are a significant contribution to the literature on the developmental psychopathology of ODD and ADHD. An open question for future research will be to disentangle whether these divergent outcomes reflect differences in how these acts are perpetrated by peers, experienced by children with ADHD symptoms, or observed and interpreted by teachers. Here, it is also important to note that both ODD/ADHD symptoms have been linked to aggression across youth development (Fite et al., 2014; Verlinden et al., 2015). Children who exhibit both aggression and victimization are at the greatest risk for maladjustment and tend to show higher levels of ADHD symptoms as compared to aggressors and victims (e.g., Schwartz, 2000; Verlinden et al., 2015). Less is known, however, regarding the prospective relations between ODD/ADHD symptoms, aggression, and status as an aggressive-victim; this remains another important direction for future research.

Limitations and Implications

Several limitations and caveats should be noted. This was a predominately White sample at a single elementary school in the U.S. Midwest. We therefore caution against generalizing results beyond similar populations and recommend further research among clinically referred and more diverse populations. Statistically, it is important to reiterate that these findings are based on the unique and robust effects of ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions on various outcomes; thus, the associations that we do not interpreted as significant results within our approach are not necessarily insignificant in a practical or statistical sense. Indeed, zero-order correlations (Table 1) show that all ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions are associated with virtually every outcome on at least some occasions. Thus, we emphasize that results do not indicate that irritability and defiance do not have persistent effects, or that inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity cannot have acute effects. An additional limitation is that, while we controlled for grade level and gender, other important covariates (e.g., family socioeconomic status, cognitive abilities) were not available. Future research should include a broader selection of covariates.

As previously discussed, children were cross-classified within four classrooms over seven occasions. This complex data structure was not specified in our models; however, steps were taken (e.g., correlated residuals, sensitivity analyses) to help address these dependencies. Additionally, ODD/ADHD symptoms were assessed exclusively by teacher-report and therefore only accounts for symptoms observable at school. Though teacher-reports of behavioral symptoms accurately identify youth with clinical diagnoses (Tripp et al., 2006), this is worth noting as previous research suggests poor agreement (van der Oord et al., 2006) between informants of disruptive behavior symptoms. Thus, our data would not capture evidence of symptoms seen in other contexts. Finally, although the longitudinal design of the current study is a notable strength, the final data collection occurred when the oldest students started fifth grade, which may have hindered the ability to demonstrate longitudinal associations with outcomes, such as depressive symptoms, that continue to increase as youth enter adolescence (Merikangas et al., 2009).

Overall, the present study advances the literature by incorporating teacher- and self-report, as well as using sophisticated longitudinal models, dimensional measures, and social-emotional/academic outcomes and unique symptom dimensions rather than diagnoses. Results both reflect and advance the current evidence regarding ODD/ADHD symptom dimensions. ADHD symptoms and their developmental outcomes are well established by decades of research, whereas ODD symptom dimensions are relatively new and require further investigation. The present results show that ODD and ADHD symptom dimensions are associated with different patterns of developmental trajectories over middle childhood. Irritability, defiance, hyperactivity-impulsivity, and, perhaps especially, inattention are important to assess in early elementary school, and may help facilitate targeted interventions for social, emotional, behavioral, and academic difficulties in the school context.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the students, teachers, staff, and administrators who participated in this research. We gratefully acknowledge support from the American Psychological Foundation (Elizabeth Munsterberg Koppitz Child Psychology Graduate Fellowships, SCE and JLC), the University of Kansas (Lillian Jacobey Baur Early Childhood Fellowship, SCE; Doctoral Student Research Fund Awards, SCE and JBB; Pioneers Classes Dissertation Research Award, SCE; Faculty Research Fund Award, PJF), the National Institutes of Mental Health (T32 Training Fellowship MH015442, JLC), and AIM for Mental Health (AIM Clinical Science Fellowship, SCE).

Footnotes

We re-estimated all major conditional and unconditional models with clustering specified at the first, last, and highest-ICC occasions. In virtually all cases, parameters of interest remained unchanged, or the changes were modest, inconsistent, or inconsequential for study results. Thus, sensitivity analyses support the robustness of the primary results reported here.

Multicollinearity statistics vary depending on which predictors and participants are included in the model, but the outcome variable is not included in these calculations and thus can be interpreted similarly across all models. Tolerance and VIF estimates did not change appreciably when covariates (grade and gender) were included.

Contributor Information

Spencer C. Evans, Department of Psychology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

John L. Cooley, Developmental Psychobiology Research Group, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, CO

Jennifer B. Blossom, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA

Casey A. Pederson, Clinical Child Psychology Program, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS

Elizabeth C. Tampke, Clinical Child Psychology Program, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS

Paula J. Fite, Clinical Child Psychology Program, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, & Pickles A (1995). Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5, 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D, Findling RL, Fristad MA, Kowatch RA, Youngstrom EA, Horwitz SM, ... & Gill MK (2012). Examining the proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder diagnosis in children in the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73(10), 1342–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Molina BSG, Pelham WE, & Hoza B (2001). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and problems in peer relations: Predictions from childhood to adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1285–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Langberg JM, Evans SW, Girio-Herrera E, & Vaughn AJ (2015). Differentiating anxiety and depression in relation to the social functioning of young adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44, 1015–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Dolan C, Hughes S, Mick E, Monuteaux MC, & Faraone SV (2008). The long-term longitudinal course of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder in ADHD boys: findings from a controlled 10-year prospective longitudinal follow-up study. Psychological medicine, 38(7), 1027–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan K, Vaillancourt T, Boyle M, & Szatmari P (2007). Comorbidity of internalizing disorders in children with oppositional defiant disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 16, 484–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Boylan K, Rowe R, Duku E, Stepp SD, Hipwell AE, & Waldman ID (2014a). Identifying the irritability dimension of ODD: Application of a modified bifactor model across five large community samples of children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123, 841–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Hipwell AE, & Loeber R (2010). Dimensions of Oppositional Defiant Disorder as predictors of depression and conduct disorder in preadolescent girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Loeber R, Lahey BB, & Rathouz PJ (2005). Developmental transitions among affective and behavioral disorders in adolescent boys. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 1200–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Rowe R, & Boylan K (2014b). Functional outcomes of child and adolescent oppositional defiant disorder symptoms in young adult men. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 264–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmine Pastura GM, Mattos P, & Campos Araújo APDQ (2009). Academic performance in ADHD when controlled for comorbid learning disorders, family income, and parental education in Brazil. Journal of Attention Disorders, 12(5), 469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabildas N, Pennington BF, & Willcutt EG (2001). A comparison of the neuropsychological profiles of the DSM-IV subtypes of ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29, 529–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Rogosch FA (2002). A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 70(1), 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C, Prior M, & Kinsella G (2002). The relationship between executive function abilities, adaptive behaviour, and academic achievement in children with externalising behaviour problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(6), 785–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor DF, & Ford JD (2012). Comorbid symptom severity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A clinical study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73, 711–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullerton-Sen C, & Crick NR (2005). Understanding the effects of physical and relational victimization: the utility of multiple perspectives in predicting social-emotional adjustment. School Psychology Review, 34, 147–160 [Google Scholar]

- Daley D, & Birchwood J (2010). ADHD and academic performance: Why does ADHD impact on academic performance and what can be done to support ADHD children in the classroom? Child: Care, Health and Development, 36, 455–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker SL, McIntosh DE, Kelly AM, Nicholls SK, & Dean RS (2001). Comorbidity among individuals classified with attention disorders. International Journal of Neuroscience, 110, 43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulou S, Henricsson L, & Rydell A (2005). ADHD symptoms and peer relations of children in a community sample: Examining associated problems, self-perceptions, and gender differences. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 388–398. [Google Scholar]

- Dill EJ, Vernberg EM, Fonagy P, Twemlow SW, & Gamm BK (2004). Negative affect in victimized children: the roles of social withdrawal, peer rejection, and attitudes towards bullying. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 159–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabick DA, Gadow KD, Carlson GA, & Bromet EJ (2004). ODD and ADHD symptoms in Ukrainian children: External validators and comorbidity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(6), 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine HE, Norman RE, Ferrari AJ, Chan GCK, Copeland WE, Whiteford HA, & Scott JG (2016). Long-term outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55, 841–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SC, & Fite PJ (2018). Dual pathways from reactive aggression to depressive symptoms in children: Further examination of the failure model. Advance online publication. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SC, Burke JD, Roberts MC, Fite PJ, Lochman JE, de la Peña FR, & Reed GM (2017). Irritability in child and adolescent psychopathology: An integrative review for ICD-11. Clinical Psychology Review, 53, 29–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SC, Fite PJ, Hendrickson ML, Rubens SL, & Mages AK (2015). The role of reactive aggression in the link between hyperactive-impulsive behaviors and peer rejection in adolescents. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 46, 903–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SC, Pederson CA, Fite PJ, Blossom JB & Cooley JL (2016). Teacher-reported irritable and defiant dimensions of Oppositional Defiant Disorder: Social, behavioral, and academic correlates. School Mental Health, 8, 292–304. [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta L, Granero R, de la Osa N, Penelo E, & Domenech JM (2012). Dimensions of Oppositional Defiant Disorder in 3-year-old preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 1128–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, & Lynskey MT (1993). The effects of conduct disorder and attention deficit in middle childhood on offending and scholastic ability at age 13. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34(6), 899–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]