Abstract

Background and aims

Chasing is a behavioral marker and a diagnostic criterion for gambling disorder. Although chasing has been recognized to play a central role in gambling disorder, research on this topic is relatively scarce. This study investigated the association between chasing, alcohol consumption, and mentalization among habitual gamblers.

Method

A total of 132 adults took part in the study. Participants were administered the South Oaks Gambling Screen, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, the Reflective Functioning Questionnaire, and a laboratory task assessing chasing behavior. Participants were randomly assigned to three experimental conditions (Control, Loss, and Win). To deeply investigate chasing behavior, participants were requested to indicate the reasons for stopping or continuing playing at the end of the experimental session.

Results

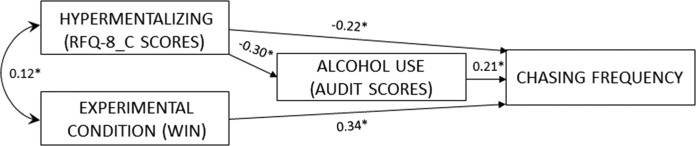

Logistic regression analysis showed that the choice to stop or continue playing depended on experimental condition and alcohol use. Hierarchical linear regression indicated that chasing propensity was affected by experimental condition, alcohol consumption, and deficit in mentalization. The results of path analysis showed that hypermentalizing predicts chasing not only directly, but also indirectly via alcohol consumption.

Conclusions

Overall, these results for the first time showed that hypermentalization plays a key role in chasing behavior over and above gambling severity. Since these findings support the idea that chasers and non-chasers are different subtypes of gamblers, clinical interventions should consider the additive role of chasing in gambling disorder.

Keywords: gambling, gambling disorder, chasing, chasing losses, chasing wins, habitual players

Introduction

Chasing consists in continuing gambling to recoup previous losses (Lesieur, 1979). According to Lesieur (1984), “the ‘chase’ begins when a gambler bets either to pay everyday bills that are due or to ‘get even’ from a fall” (p. 1). From the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1987) to the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), chasing losses is considered as a behavioral marker and a diagnostic criterion for disordered gambling. Loss chasing is such a common phenomenon in gambling (e.g., McBride, Adamson, & Shevlin, 2010; O’Connor & Dickerson, 2003; Sacco, Torres, Cunningham-Williams, Woods, & Unick, 2011) that 75.9% of problem gamblers chase (Toce-Gerstein, Gerstein, & Volberg, 2003). Furthermore, as suggested by Yakovenko, Fortgang, Prentice, Hoff, and Potenza (2018), chasing is a useful criterion for identifying at-risk gamblers, since, “all other factors being equal, increased chasing behavior is related to greater gambling involvement, which could potentially generate problems relating to a significant frequency and expenditure of money spent on gambling activities” (p. 381).

According to DSM, chasing implies returning to gamble on another day in the hope of recouping lost money. However, chasing is not confined, as DSM criteria might suggest, to between-session chasing (i.e., returning on a later day to recoup lost money). Chasing also refers to the tendency to gamble too long within a particular session (within-session chasing; Breen & Zuckerman, 1999, p. 1080).

Although originally chasing refers mainly to continue gambling in an attempt to recoup previous losses starting a new gambling session, subsequent research focused on chasing wins also, that is, to continue gambling after a win in the hope to gain more (e.g., Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002; O’Connor & Dickerson, 2003; Subramaniam, Chong, Browning, & Thomas, 2017). For instance, Blaszczynski and Nower’s pathways model (2002) postulates that there are two forms of chasing, namely chasing losses and chasing wins, since chasing behavior also refers to persistent gambling both when losing or winning within a gambling session (Goodie, Fortune, & Shotwell, 2019). Indeed, in both cases, players show the inability to stop gambling to tempting fate further. In this sense, chasing wins and chasing losses would be two sides of the same coin (Nigro, Ciccarelli, & Cosenza, 2018a), if only because, since the house always wins, in the long run, continuing gambling will turn wins into losses. Ultimately, continuing to gamble for longer than originally intended, to increase winnings or recover losses within a gambling session, reflects “the increasing excitement and arousal associated with gambling behavior” (Campbell-Meiklejohn, Woolrich, Passingham, & Rogers, 2008, p. 293). Indeed, Ciccarelli, Cosenza, Griffiths, D’Olimpio, and Nigro (2019) found that the heightened levels of craving and the inability to tolerate delays in gratification play a role in both the decision to chase losses and chasing persistence.

The extant literature has shown that chasing represents an important step in the development and maintenance of gambling disorder (Breen & Zuckerman, 1999; Goudriaan, Yücel, & van Holst, 2014; Lesieur, 1984; see also Corless & Dickerson, 1989; Sharpe, 2002; for a review, see Nigro, Ciccarelli, & Cosenza, 2018b), and is one of the few observable signs for disordered gambling (Gainsbury, Suhonen, & Saaststamoinen, 2014), and the only criterion of gambling addiction absent in substance use disorder (Quester & Romanczuk-Seiferth, 2015). Prior research found that chasing is associated, among others, with impulsivity (Breen & Zuckerman, 1999), sensation seeking (Linnet, Røjskjær, Nygaard, & Maher, 2006), increased activation in brain regions related to reward expectation (Campbell-Meiklejohn et al., 2008), low sensitivity to punishment (Kim & Lee, 2011), poor decision-making (Nigro et al., 2018a), disinhibition (Nigro et al., 2018b), alexithymia (Bibby, 2016), and shortened time horizon (Ciccarelli, Cosenza, D’Olimpio, et al., 2019).

Two latent class analyses (Kong et al., 2014; James, O’Malley, & Tunney, 2016) have demonstrated that non-chasers and chasers belong to quite different subtypes of gamblers. Using a large sample of past-year adolescent gamblers, Kong et al. (2014) identified four gambling classes, one of which (at-risk chasing gambling) is “characterized by relatively elevated probabilities of gambling to win back lost money and gambling more money over time” (p. 426). In a study investigating the latent structure of gambling disorders among adults, James et al. (2016) identified three classes of gamblers, namely initial, intermediate, and high-severity disordered gamblers. The intermediate class includes gamblers who are characterized by loss chasing and loss preoccupation, without showing a range of other symptoms. In brief, these studies further support the findings by Toce-Gerstein et al. (2003), according to whom, chasing “often occurs in the absence of other criteria, and almost as frequently with very few other signs as when many are present” (p. 1668). Notably, regardless of gambling severity, chasers, compared to non-chasers, were found to perform poorer on a behavioral task assessing affective decision-making task (Nigro et al., 2018a), to score higher on the Personality Inventory for the DSM-5 (PID-5) maladaptive personality domains (Nigro et al., 2018b), and to be more oriented to the present, rather than thinking about the future (Ciccarelli, Cosenza, D’Olimpio, et al., 2019).

Although the increasing acknowledgment that people can continue gambling either in the hope of recovering lost money or gaining more money, only two studies have investigated both chasing losses and chasing wins (Lister, Nower, & Wohl, 2016; O’Connor & Dickerson, 2003). O’Connor and Dickerson (2003), who first analyzed the role of chasing in relation to impaired control over gambling, found no difference between returning later to chase after large wins or after losing. Lister et al. (2016) reported that gamblers with higher winning money motivation were more likely to decide to chase and chased more in response to both losses and wins. The findings from the aforementioned studies support the idea that “problem gamblers have difficulty quitting, regardless of whether they are losing or winning” (Breen & Zuckerman, 1999, p. 1098).

Given the difficulties in reproducing in the laboratory between-session chasing, as defined by Lesieur (1979) and the DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria for disordered gambling, the few behavioral tasks devoted to assessing chasing focused on within-session chasing. With the only exception of Linnet et al. (2006), who measured episodic chasing within the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), some authors have developed or implemented ad hoc procedures for estimating within-session chasing (Bibby, 2016; Breen & Zuckerman, 1999; Campbell-Meiklejohn et al., 2008; Lister et al., 2016; Nigro et al., 2018a; Worhunsky, Potenza, & Rogers, 2017). Although laboratory tasks have assessed chasing in quite different ways, they share the following features at least: (a) the task simulates real-life game situations in which participants are allowed to stop in any moment; (b) the game is apparently chance-based; (c) the outcomes are manipulated; (d) participants win or lose some virtual money; and (e) both the decision to chase and the number of trials played are considered variables of interest.

Prior research reported an association between deficit in metacognitive abilities and disordered gambling among both adolescents and adults (e.g., Cosenza, Ciccarelli, & Nigro, 2019; Lindberg, Fernie, & Spada, 2011; Spada & Roarty, 2015). Interestingly, Brevers et al. (2013, 2014) found a relationship between poor decision-making and biased metacognition in pathological gamblers. Indeed, during a gambling-like task (Brevers et al., 2013), as well as a non-gambling task (Brevers et al., 2014), relative to healthy participants, problem gamblers who were asked to wager on their own decisions (post-decision wagering) erroneously believed that they were performing much better than they actually were. Unlike controls, the confidence level in problem gamblers did not vary substantially according to their performance. In other words, they tended to wager highly while performing poorly. Being overconfident in own ability to control future outcomes but ignoring the severe negative consequences in the long run is quintessential of chasing. As suggested by Goodie (2005), overconfidence steams from the illusion of control and promotes greater betting, which in turn can lead to impaired betting performance. It may be that the decision to continue playing depends mainly on sensitivity to loss and rewards (e.g., Fleming & Dolan, 2010; Schurger & Sher, 2008) and/or on cognitive distortions (for a review, see Goodie et al., 2019). However, the aforementioned findings about the association between poor mentalization and gambling severity suggest clarifying whether and to what extent mentalization failures affect chasing behavior that, in turn, might fuel further gambling addiction.

According to Fonagy, Bateman, and Luyten (2012), mentalization, also known as reflective functioning (RF) [Mentalization and metacognition are conceptually similar. They differ each other mostly in terms of theoretical background (cognitive vs. psychodynamic) and therapeutic implications (see Fonagy et al., 2016; Ridenour, Knauss, & Hamm, 2019)], refers to a form of social cognition characterized by the capacity to perceive and interpret both one’s own and others’ behavior in terms of intentional mental states, such as thoughts, feelings, desires, wishes, goals, and attitudes. Mentalization failures have been found to be associated with a wide range of mental disorders, such as borderline and antisocial personality disorders (Fonagy et al., 2016), depression (Luyten, Fonagy, Lemma, & Target, 2012), eating disorders (Pedersen, Poulsen, & Lunn, 2015; Skårderud, 2007; see also Fonagy et al., 2016), substance abuse (Allen, Fonagy, & Bateman, 2008; Lecointe, Bernoussi, Masson, & Schauder, 2016; Möller, Karlgren, Sandell, Falkenström, & Philips, 2016), as well as with other forms of out-of-control behaviors, such as sexual (Berry & Berry, 2014) and food addiction (Innamorati et al., 2017). Moreover, impairment in mentalization has been associated to gambling disorder in adolescents (Cosenza et al., 2019).

As noted by Lister et al. (2016), who examined the role of gambling achievement orientation on chasing behavior in young adult gamblers, research on chasing has focused mostly on the role of individual differences, largely neglecting the role of motivational factors in the choice to continue or stop playing. Given that investigating gamblers’ motivations in chasing behavior seem to be a promising avenue in gambling studies, we have analyzed both gambling and chasing motivations, if only because, over and above gambling severity, chasers and non-chasers seem to belong to two different subtypes of gamblers (James et al., 2016; Kong et al., 2014). Finally, asking participants about chasing motivation allowed us to test the effectiveness of experimental manipulation.

Although some studies proved that gambling disorder and alcohol abuse often co-occur at greater than chance levels (for reviews, see Black & Show, 2019; Tackett et al., 2017), little research has been conducted on the co-occurrence of alcohol use and chasing behavior. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, only O’Connor and Dickerson (2003) focused on this issue. Specifically, they found a significant association between retrospective report of chasing and the perceived role of alcohol in chasing, e.g., to what extent participants believed alcohol contributed to their chasing (alcohol-related chasing). Since prior research has found greater persistence in gambling after alcohol consumption and shorter latency between betting decisions (Kyngdon & Dickerson, 1999) and has evidenced a steeper cumulative loss function following alcohol (Phillips & Ogeil, 2007), we were interested in further investigating the role of alcohol consumption in chasing behavior, not only because concurrent drinking and gambling is prevalent among gamblers, but also because some studies on alcohol dependence have found an association between alcohol misuse and mentalizing deficits (e.g., Le Berre, 2019; Maurage, de Timary, Tecco, Lechantre, & Samson, 2015; Uekermann, Channon, Winkel, Schlebusch, & Daum, 2007).

Therefore, the main aim of this study was to first investigate the interplay between chasing, mentalization, and alcohol use in a sample of adult habitual gamblers. A second purpose of the study was to analyze the role of motivational factors, namely gambling motives, in chasing behavior. Although previous research investigating chasing by means of a behavioral task did not find differences between chasing losses and chasing wins (Lister et al., 2016), since we added a control condition that could be considered less attractive for participants, it was expected that participants in the control condition would decide to chase less and less frequently than participants in the Loss and Win conditions, respectively. Furthermore, considering the above-cited literature, it was expected that chasing would be associated with poor mentalization and higher alcohol consumption.

Methods

Participants and procedure

A convenience sample of 132 Italian adults (82.6% males), aged between 18 and 72 years (Mage = 37.93 years; SD = 15.82), were recruited from five video lottery terminal gambling venues offering the same range of gambling activities (games of chances, such as slot machines, casino games, etc.). Of the participants, 62.9% were single, 24.2% married, 10.6% separated or divorced, and 2.3% widowed. About modal occupation status, 27.3% of participants were unemployed, 21.2% manual workers, and 19.7% office workers. The two inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) participants reported to gamble once a week or more, and (b) were 18 years of age or over. Participants were tested individually in a quiet room made available by the management. Two hundred and one habitual players were requested to participate voluntarily, and no compensation was provided for this study. The percentage of people who declined to take part in the study was about 34% (N = 68). The participants completed a computerized task and three questionnaires. For each condition, half of the participants completed the computerized task at the beginning of the session, the other half at the end. In such a way, the (potential) influence of the experimental task on the paper-and-pencil measures, and vice versa, was balanced. As chasing task had three conditions (Control, Loss, and Win, respectively), an equal number of participants (N = 44) was randomly assigned to each condition following block randomization procedure.

The questionnaires were administered in counterbalanced order. The administration of the instruments required from a minimum of about 30 min to a maximum of about 45 min. A brief post-experimental interview investigating the reasons for stopping or continuing playing ended the session.

Measures

The participants were administered the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesieur & Blume, 1987; Italian translation: Cosenza, Matarazzo, Baldassarre, & Nigro, 2014) to assess the degree and level of problem gambling severity, the Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (RFQ-8; Fonagy et al., 2016; Italian validation: Morandotti et al., 2018); to assess mentalization, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993); and to assess alcohol consumption, drinking behaviors, and alcohol-related problems, and a computerized task developed to measure chasing behavior (ChasIT; Nigro et al., 2018a).

The SOGS is a self-report measure assessing the frequency and the gravity of gambling problems. Although the SOGS has been found to produce inflated pathological gambling estimates, it is still frequently used as a screen in experimental research (James et al., 2016). In this study, the SOGS was chosen to allow comparisons with previous researches on chasing (e.g., Breen & Zuckerman, 1999; Brevers et al., 2013, 2014; Campbell-Meiklejohn et al., 2008; Ciccarelli, Cosenza, D’Olimpio, et al., 2019, Ciccarelli, Cosenza, Griffiths, D’Olimpio, & Nigro, 2019; Linnet et al., 2006; Nigro et al., 2018a, 2018b). The questionnaire is composed of 20 scored items and some unscored items. The total score ranges from 0 to 20. The unscored items request participants to indicate the frequency of participation in different gambling activities (“not at all,” “less than once a week,” or “once a week or more”), and the largest amount of money gambled in 1 day. Furthermore, we asked participants to indicate the main reasons for gambling in a list of motives (Volberg, 1993). In this study, Cronbach’s α was .88.

The RFQ-8 is an eight item self-rating questionnaire assessing RF. The RFQ-8 contains two subscales, tapping into different processes: Certainty about mental states (RFQ-8_C) and Uncertainty about mental states (RFQ-8_U). Low agreement on the RFQ-8_C scale reflects a tendency to develop excessive but inaccurate mentalizing (hypermentalizing), whereas high agreement reflects more genuine mentalizing. Similarly, higher scores on the RFQ_U reveal an almost complete lack of knowledge about mental states (hypomentalizing), whereas lower scores reflect acknowledgment of the opaqueness of one’s own mental states and that of others, which is characteristic of genuine mentalizing. Internal consistency was satisfactory for the RFQ_C dimension (0.71) and the RFQ_U subscale (0.70).

Chasing behavior

Chasing behavior was measured by means of a 60-trial computerized task (ChasIT; Nigro et al., 2018a) simulating a card game in which participants played against the house. The initial amount of money was €10 and participants were asked to treat the initial stake as real money. Each trial presented two cards, each one reporting a number ranging from 1 to 9. Participants were told they would win €1, if they had the highest card, but lose €1, if the house had the highest card. For each of the first 30 trials (phase 1), participants received a positive (You won €1!) or a negative (You lost €1!) feedback. After the first phase, participants in the Control condition saved the entire budget, in the Win condition gained €2 extra, and in the Loss condition lost not only the entire budget, but also €2. For the subsequent 30 trials (phase 2), after each trial, participants received the following feedback: “You won (or lost) 1 Euro! Now, your credit is X Euros. If you want to continue playing, please, press the key “M” on the computer keyboard. If you decide to stop playing, please, press the key “Z” on the computer keyboard.” In such a way, participants could decide, in any moment, if they would like to continue or stop the game, simply by pressing the designated key. According to the experimental condition (Control, Loss, and Win, respectively), the wins and losses (15 and 15 in the Control condition, 9 and 21 in the Loss condition, 21 and 9 in the Win condition) were randomly distributed throughout the gambling session, but the sequence of wins and losses was the same for every participant in that condition. At the end of the second phase, that is after another block of 30 trials, the final budget was €10 in the Control condition, minus €14 in the Loss condition, and €24 in the Win condition.

Participants who chose to quit the game at the beginning of the second phase were considered non-chasers, whereas participants who decided to continue gaming were classified as chasers. Since participants could play till the end, the highest chasing total score was 30. The decision to quit or continue gaming and the number of trials played (chasing frequency) were the two dependent measures of interest.

Statistical analyses

Data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 20.0 (Armonk, NY, USA). The α level was set at p < .05. All variables were initially screened for missing data, distribution abnormalities, and outliers (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Since the distribution of the SOGS was positively skewed, square-root transformation was performed on this variable, so that assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity had been adequately met.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationships among the study variables (chasing frequency, age, years of education, SOGS, RFQ-8, and AUDIT scores). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess mean differences on continuous variables. For categorical data (motives for gambling) differences in percentages were compared with the chi-square test. The independent associations between age, education, experimental condition, RFQ-8 subscales, SOGS and AUDIT scores, and the decision to chase were analyzed using logistic regression. A hierarchical linear regression analysis was performed to examine the unique contribution of predictor variables to chasing proneness or chasing propensity, as measured by chasing frequency. To control for the presence of multicollinearity, before interpreting the regression coefficients, we calculated the variance inflation factors (Ryan, 1997).

Finally, considering linear regression analysis results and evidences from the aforementioned research, two path analyses was performed to analyze the causal relationships among variables contributing to chasing frequency. Path analyses were conducted with the EQS 6.2 software (Encino, CA, USA) program for structural equation modeling (Bentler, 2008). For each estimated model, goodness of model fit was evaluated with the likelihood ratio χ2 test statistic corrected for data non-normality with Satorra and Bentler’s (1994) method (SeB χ2), as well as with four descriptive fit indices: the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with its 90% confidence interval (90% CI), the goodness of fit index (GFI), and the comparative fit index (CFI). Acceptable fits between model and data are reflected by a non-significant S-B χ2, GFI, and CFI indexes of 0.95 or greater, RMSEA of between 0.05 and 0.08.

Ethics

The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research team’s University Ethics Committee approved the study. All participants were informed about the study and all provided informed consent.

Results

Means and standard deviations by experimental condition are presented in Table 1. For ease of interpretation, descriptive statistics are reported for the untransformed variables.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations (SDs) by experimental condition

| Control (N = 44) | Loss (N = 44) | Win (N = 44) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| SOGS total score | 4.18 | 3.99 | 4.14 | 4.46 | 5.07 | 4.33 |

| RFQ-8 | ||||||

| Certainty | 1.06 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.70 | 1.22 | 0.88 |

| Uncertainty | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.56 |

| AUDIT | 6.20 | 5.36 | 7.44 | 6.57 | 6.30 | 6.20 |

| Chasing frequency | 8.98 | 12.06 | 8.95 | 15.27 | 12.87 | 8.98 |

Note. SOGS total score: South Oaks Gambling Screen – untransformed score; RFQ-8: Reflective Functioning Questionnaire; AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Preliminarily, to ascertain whether participants assigned to the three different experimental conditions differed in terms of gender, age, education, marital status, occupation, SOGS, RFQ-8, and AUDIT scores, data were submitted to χ2 test or univariate ANOVA. The results indicated that the three groups did not differed each other regarding gender [χ2(2, N = 132) = 0.11, p = .95, Cramér’s V = 0.03], age (F2, 129 = 2.03, p = .14, ηp2 = .03), education (F2, 129 =1.32, p = .20, ηp2 = .02), marital status [χ2(6, N =132) = 7.22, p = .30, Cramér’s V = 0.17], occupation [χ2(16, N = 132) = 11.77, p = .76, Cramér’s V = 0.21], SOGS scores (F2, 129 = 0.86, p = .43, ηp2 = .01), RFQ-8 scores (Certainty: F2,129 = 1.19, p = .31, ηp2 = .02; Uncertainty: F2, 129 = 1.70, p = .19, ηp2 = .03), and AUDIT scores (F2, 129 = 0.19, p = .83, ηp2 = .003).

To ascertain whether chasing frequency, SOGS, RFQ-8, and AUDIT scores varied by gender, data were submitted to univariate ANOVA. Effects of gender were observed only on RFQ_U scores (F1, 130 = 4.93, p < .05, ηp2 = .04), with females outperforming males.

To ascertain whether there were associations between age associations between age, years of education, chasing frequency, SOGS, RFQ-8, and AUDIT scores, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. The results showed that chasing proneness was significantly positively associated with SOGS (r = .18, p < .05) and AUDIT scores (r = .28, p < .01), but negatively with RFQ_C scores (r = −.24, p < .01). Gambling severity was positively associated with RFQ_U (r = .29, p < .01) and AUDIT scores (r = .23, p < .01), and negatively with education (r = −.30, p < .01) and RFQ_C scores (r = −.29, p < .01). Finally, the choice to continue playing correlated negatively with age (r = −.25, p < .01).

To verify whether, as hypothesized, chasing frequency varied by experimental condition, data were submitted to univariate ANOVA. The results showed a significant difference due to experimental condition in chasing frequency (F2, 129 = 7.98, p < .001, ηp2 = .11). Bonferroni post-hoc test (p < .05) revealed that, compared to other groups, participants in the Win condition chased significantly more often.

The χ2 test was used to ascertain whether there was a relationship between the choice to chase and each motive for gambling. Although about a third of the participants reported they gamble mainly for winning money (31.64%) or for fun (23.05%), the results revealed that, relative to non-chasers, chasers continue to play significantly more to socialize [χ2(1, N = 132) = 4.49, p < .05].

As far as chasing motivations, participant responses revealed that the reason for stopping or continuing gambling varied across the experimental conditions. For instance, in the Control condition, participants stopped playing because they were satisfied, because they were winning, or to avoid losses. On the contrary, participants continued gambling to gain more money or because the money at stake was virtual. In the Loss condition participants tendentially chose to quit because they were losing and continued to recoup the budget. Finally, in the Win condition, participants who decided to stop playing as well as those who chose to go further shared the same motivation: they were winning. Table 2 shows motivations (in percentages) for stopping or continuing gambling as a function of experimental condition.

Table 2.

Percentages of motivations to stop or continue playing as a function of experimental condition

| Control (N = 44) | Loss (N = 44) | Win (N = 44) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Stop (N = 20) | Play (N = 24) | Stop (N = 23) | Play (N = 21) | Stop (N = 12) | Play (N = 32) |

| To gain more money | – | 20.8 | – | – | – | 18.8 |

| No loss | – | 8.3 | – | – | – | – |

| For winning | – | 16.7 | – | 14.3 | – | 12.5 |

| For fun/excitement/challenge/tempting fate | – | 12.5 | – | 9.5 | – | 15.6 |

| Low chance to win | 10.0 | – | 4.4 | – | – | – |

| To save budget | 20.0 | 8.3 | – | – | – | – |

| Was satisfied | 25.0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| To avoid losses | 20.0 | – | 21.7 | – | 25.0 | – |

| Was winning | 5.0 | 4.2 | – | – | 75.0 | 34.4 |

| Was losing | – | – | 52.2 | 9.5 | – | – |

| To recoup budget | – | – | – | 52.4 | – | – |

| For craving | – | – | – | 4.8 | – | 3.1 |

| Low financial risk | – | – | – | 4.8 | – | 12.5 |

| Unattractive task | 5.0 | – | 17.4 | – | – | – |

| Was tired/bored | 5.0 | – | 4.4 | – | – | – |

| Virtual/not own money | 10.0 | 29.2 | – | 4.8 | – | 3.1 |

To assess the relative contribution of age, education, experimental condition (after dummy coding), mentalization (RFQ-8 scores), alcohol consumption (AUDIT scores), and gambling severity (SOGS scores) for the choice to chase, a hierarchical logistic regression analysis was conducted, using the two groups (chasers and non-chasers) as the criterion variable. For the regression, the Hosmer and Lemeshow’s test was not significant [χ2(8, N = 132) = 6.8, p = .56], indicating an adequate model fit. The results of the final regression model showed that the Win condition and AUDIT scores were significant predictors of the choice to chase (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of the final logistic regression model

| B | SE | Wald | df | p | Odds ratio [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.037 | 0.013 | 8.772 | 1 | .003 | 0.963 [0.940–0.987] |

| Condition: Win | 1.242 | 0.446 | 7.767 | 1 | .005 | 0.289 [0.121–0.692] |

| AUDIT | 0.072 | 0.544 | 4.964 | 1 | .026 | 1.075 [1.009–1.146] |

Note. Dependent variable: Group (non-chasers/chasers); Model: χ2 = 22.07; Nagelkerke’s R2 = .207. Overall percentage accuracy rate = 70%. AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; SE: standard error; CI: confidence interval.

To identify the potential predictors of chasing frequency, age, education (in years), experimental condition (after dummy coding), scores on SOGS, RFQ-8, and AUDIT were input to a multiple regression analysis with chasing frequency as the dependent measure. Linear regression analysis (Table 4) showed that, along with the Win condition, AUDIT and RFQ_C scores were significant predictors of chasing frequency (R2adj = .21, F4, 127 = 9.88, p < .001).

Table 4.

Summary of hierarchical linear regression analysis

| Variable | B | R2 | ΔR2 | β | t | p | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||||||

| Education | 0.540 | .023 | .023 | 0.152 | 1.756 | .081 | 1.000 |

| Step 2 | |||||||

| Education | 0.708 | .037 | .114 | 0.200 | 2.418 | .017 | 1.020 |

| Condition: Win | 8.640 | 0.340 | 4.120 | .000 | 1.020 | ||

| Step 3 | |||||||

| Education | 0.621 | .204 | .067 | 0.175 | 2.191 | .030 | 1.029 |

| Condition: Win | 8.581 | 0.338 | 4.244 | .000 | 1.020 | ||

| AUDIT | 0.490 | 0.260 | 3.285 | .001 | 1.009 | ||

| Step 4 | |||||||

| Education | 0.531 | .237 | .033 | 0.150 | 1.890 | .061 | 1.084 |

| Condition: Win | 9.095 | 0.358 | 4.551 | .000 | 1.032 | ||

| AUDIT | 0.384 | 0.204 | 2.508 | .013 | 1.103 | ||

| RFQ-8 certainty | −2.876 | −0.195 | −2.358 | .020 | 1.138 | ||

Note. Dependent variable: chasing frequency. B: unstandardized coefficient; ΔR2: R2 change; β: standardized regression coefficient; VIF: variance inflation factor; AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; RFQ-8: Reflective Functioning Questionnaire.

Finally, to ascertain if hypermentalizing (low scores on the RFQ-8_C subscale) was on the path from alcohol use to chasing proneness or if alcohol consumption was the mediator of the impact of hypermentalizing on chasing propensity, we compared two different models: the former (Model 1) assumed that alcohol use can predict chasing not only directly, but also indirectly via hypermentalizing; the latter (Model 2) assumed that hypermentalizing can predict chasing not only directly, but also indirectly via alcohol consumption. Model fit statistics (GFI and CFI estimates, RMSEA and SRMR values) for the two models are displayed in Table 5. As Table 5 shows, relative to the first model, the second one fit better to the data.

Table 5.

Path analysis fit indexes for alternative models

| S-B χ2 | df | GFI | CFI | RMSEA [90% CI] | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 2.16 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.09 [0.000, 0.042] | 0.042 |

| Model 2 | 1.16 | 1 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.00 [0.000, 0.017] | 0.011 |

Note. S-B χ2: Satorra–Bentler scaled χ2 statistic; GFI: goodness of fit index; CFI: comparative fit index; RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation; 90% CI: 90% confidence interval for RMSEA; SRMR: standardized root mean square residual.

Summing up, low scores on the RFQ-8_C scale predict chasing frequency directly, as well as indirectly via high AUDIT scores (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Path diagram for Model 2. Note. *Standardized solution

Discussion

This study first empirically investigated the interplay between mentalization, alcohol use, and chasing, including motivation to chase, in a sample of adult habitual gamblers. The results of regression analyses showed that the choice to stop or continue playing depended on experimental condition and alcohol consumption, whereas chasing proneness was predicted by experimental condition, alcohol use, and poor mentalization. Although there is an overlap between the variance explained by both regression models, it is interesting to note that poor mentalization affects only chasing frequency.

Unlike O’Connor and Dickerson (2003) as well as Lister et al. (2016), who did not observe significant differences between chasing losses and chasing wins, our results showed that, compared to participants in both the control and loss conditions, participants in the Win condition chased more and more frequently. It may be that in our computerized task the Win condition has been considered more attractive, more challenging, or simply less “dangerous” in terms of financial risk. Similarly, since we did not measure loss of aversion nor risk propensity, it cannot be ruled out that, relative to participants in the other groups, subjects in the Loss condition were more sensitive to losses and/or less willing to accept risk.

As regards to alcohol consumption, our results are consistent with prior research on the association between chasing and alcohol use (Kyngdon & Dickerson, 1999; O’Connor & Dickerson, 2003; Phillips & Ogeil, 2007). Indeed, both logistic and linear regression analyses showed that high levels of alcohol use predict both the choice to chase and chasing frequency. As stressed by Cronce and Corbin (2010), who have shown that alcohol influences the average amount bet and leads to more rapid loss of available funds, “maladaptive behavior occurring within a single gambling session […] may set the stage for the development of gambling psychopathology. This type of within-session chasing may lead to long-term gambling problems by precipitating between-session chasing” (pp. 145–146). Alcohol could contribute to chasing via diminished judgment or disinhibitory effects (O’Connor & Dickerson, 2003). Indeed, a recent study reported a positive association between alcohol consumption and chasing frequency among habitual players and found that disinhibition, as measured by the Personality Inventory for DSM-5–Brief Form (PID-5-BF), was not only a powerful predictor of the choice to chase, but also the most powerful predictor of chasing frequency (Nigro et al., 2018b).

Notably, since regression analyses excluded SOGS scores from the final model, this finding further supports the idea that, ceteris paribus, chasers and non-chasers belong to two quite different categories of gamblers (Ciccarelli, Cosenza, D’Olimpio, et al., 2019; James et al., 2016; Kong et al., 2014; Nigro et al., 2018a, 2018b).

As far as mentalization, the results of both correlation and linear regression analyses highlighted a strong association between chasing frequency and low scores on the RFQ-8_C subscale. Reporting low scores on this dimension is considered a marker of hypermentalizing (excessive theory of mind) that arises from having developed very complex models of the mind that, nonetheless, have little or no correspondence to observable evidence (Fonagy et al., 2016). Specifically, hypermentalizing or pseudomentalizing “can be defined as a social-cognitive process that involves making assumptions about other people’s mental states that go so far beyond observable data that the average observer will struggle to see how they are justified” (Sharp et al., 2013, p. 4). Individuals who strongly disagree with RFQ-8_C statements such as “I don’t always know why I do what I do,” “Sometimes I do things without really knowing why,” or “People’s thoughts are a mystery to me” are prone to hypermentalizing. In brief, they are excessively self-confident and are likely to overestimate their ability to interpret both the self and others’ behavior in terms of intentional mental states.

The significant correlation between SOGS and RFQ-8 scores we observed is consistent with the findings of Brevers et al. (2013) on post-decision wagering, namely wagering contingent on a previous decision. As stated above, these authors explored the association between a metacognitive process (the ability to reflect and evaluate the awareness of one’s own decision) and performance on the IGT in a group of pathological gamblers and in a normal control group and found that pathological gamblers exhibit impairments in their ability to correctly assess risk in situations that involve ambiguity, as well as in their ability to correctly express metacognitive judgments about their own performance. Recently, Cosenza et al. (2019), who observed a close relationship between gambling severity and impairment in mentalizing among adolescent gamblers, concluded that gamblers’ post-decisional wagering could reflect a more general impairment in mentalization (p. 166).

As suggested by Brevers et al. (2013), disordered gamblers show a “double impairment”: in their ability to assess risk, as well as in their ability to correctly express metacognitive judgment about their own performance (p. 126). However, it may be also that the attempts of recouping lost money or gaining more by continuing gambling mirror ultimately the inability to stop gambling, since evaluating rationally the quality of one’s own decisions could conflict with the urge to gamble. In such a perspective, hypermentalizing could be either the cause or the consequence of chasing propensity.

As the analysis of chasing motivations revealed that the choice to continue playing after a series of losses (Loss condition) was mostly driven by the hope of recouping lost money (which is typical of chasing losses), whereas persisting in gambling after a series of wins (Win condition) was largely driven by the hope of further wins (which is typical of chasing wins). Regardless of experimental condition, participants’ motivations for chasing confirmed that “Gamblers frequently continue to gamble for longer than originally intended to increase their winnings or recover losses” (Campbell-Meiklejohn et al., 2008, p. 293). Believing that a successful outcome is due after a run of bad luck (gamble’s fallacy) or that the winning streak will continue after a run of good luck (hot-hand fallacy) might depend on failure to recognize the meaning of randomness and the independence of chance events (Goodie et al., 2019; Subramaniam et al., 2017). Blaszczynski and Nower’s pathways model (2002) postulated that, irrespective of the reasons for which individuals start gambling, once a pattern of habitual gambling is established, the excitement resulting from gambling and the irrational beliefs related to the probability of winning may encourage both chasing losses and chasing wins. In such a perspective, chasing appears to be an instrumental behavior in the maintenance of problem gambling (Ciccarelli, Cosenza, Griffiths, et al., 2019) and being unaware of how poor is own real performance as Brevers’ findings indicated (Brevers et al., 2014), is, paradoxically, a “protective factor” against to stop gambling.

If poor mentalizing is a core feature of chasing proneness, then mentalization-based treatments tailored on problematic chasers could help reducing gambling dependence. The results of clinical interventions on borderline disorder (e.g., Bateman & Fonagy, 2015; Bo, Sharp, Fonagy, & Kongersley, 2017), depression (Luyten, Blatt, & Fonagy, 2013), and alcohol use disorder (Caselli, Martino, Spada, & Wells, 2018) are encouraging. However, one should bear in mind that different disorders and different subtypes of the same disorder, if any, need different intervention treatments.

Limitations and future directions

Although several strengths characterized this study, including the use of a behavioral task to assess chasing, there are some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the present results. First, the participants were recruited using convenient sampling of Italian habitual players. Second, the current data are mainly based on self-report measures, which may limit the generalizability of the results due to recall bias and social desirability. Furthermore, gambling severity was assessed through a measure that has been criticized for excessive false positives (Goodie et al., 2013). However, it is worth noting that the SOGS demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity (Stinchfield, 2002). Finally, although the information collected during the post-experimental interview was somewhat encouraging as with the ecological validity of our procedure (ChasIT task), we acknowledge that additional effort should be made so that the task resembles increasingly to games performed in daily life, if only because to reduce the “tension between the need for control and the need to preserve the essence of the phenomenon under investigation” (Baddeley, 1989, p. 104).

Future research should be addressed to analyze the role of cognitive distortions in chasing behavior, focusing on gambler’s fallacy and hot-hand fallacy and (perhaps more importantly) focus on testing ad hoc mentalization-based treatments for disordered gamblers with or without chasing propensity.

Conclusions

To the best of authors’ knowledge, this study provides new information regarding the relationship between chasing behavior, alcohol use, and mentalization abilities. Furthermore, this is the first study to examine motivations underlying the decision to continue or stop gaming, allowing us to distinguish chasing behavior from gambling habituation or gambling tolerance. The findings regarding the association between chasing and poor mentalization and, as path analysis indicated, the mediating role of alcohol use are highly novel. Among others, these findings support further the idea that gamblers can fall into two quite different categories, namely chasers and non-chasers, regardless gambling severity.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all study participants for their contributions.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: No financial support was received for this study.

Authors’ contribution

GN and MCo designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MCo conducted literature searches and provided summaries of previous research studies. MCi, FD, and GN conducted the statistical analysis. OM revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allen J., Fonagy P., Bateman A. (2008). Mentalizing in clinical practice. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [APA]. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd rev. ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [APA]. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A. (1989). Finding the bloody horse In Poon L. W., Rubin D. C., Wilson B. A. (Eds.), Everyday cognition in adulthood and late life (pp. 104–105). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Fonagy P. (2015). Borderline personality disorder and mood disorders: Mentalizing as a framework for integrated treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(8), 792–804. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P. M. (2008). EQS structural equation modeling software. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software. [Google Scholar]

- Berry M. D., Berry P. D. (2014). Mentalization-based therapy for sexual addiction: Foundations for a clinical model. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 29(2), 245–260. doi: 10.1080/14681994.2013.856516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bibby P. A. (2016). Loss-chasing, alexithymia, and impulsivity in a gambling task: Alexithymia as a precursor to loss-chasing behavior when gambling. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 3. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black D. W., Shaw M. (2019). The epidemiology of gambling disorder In Heinz A., Romanczuk-Seiferth N., Potenza M. (Eds.), Gambling disorder (pp. 29–48). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczynski A., Nower L. (2002). A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction, 97(5), 487–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo S., Sharp C., Fonagy P., Kongerslev M. (2017). Hypermentalizing, attachment, and epistemic trust in adolescent BPD: Clinical illustrations. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 8(2), 172–182. doi: 10.1037/per0000161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen R. B., Zuckerman M. (1999). ‘Chasing’ in gambling behavior: Personality and cognitive determinants. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(6), 1097–1111. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00052-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brevers D., Cleeremans A., Bechara A., Greisen M., Kornreich C., Verbanck P., Noël X. (2013). Impaired self-awareness in pathological gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(1), 119–129. doi: 10.1007/s10899-012-9292-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brevers D., Cleeremans A., Bechara A., Greisen M., Kornreich C., Verbanck P., Noël X. (2014). Impaired metacognitive capacities in individuals with problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(1), 141–152. doi: 10.1007/s10899-012-9348-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Meiklejohn D. K., Woolrich M. W., Passingham R. E., Rogers R. D. (2008). Knowing when to stop: The brain mechanisms of chasing losses. Biological Psychiatry, 63(3), 293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli G., Martino F., Spada M. M., Wells A. (2018). Metacognitive therapy for alcohol use disorder: A systematic case series. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2619. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli M., Cosenza M., D’Olimpio F., Griffiths M. D., Nigro G. (2019). An experimental investigation of the role of delay discounting and craving in gambling chasing behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 93, 250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli M., Cosenza M., Griffiths M. D., D’Olimpio F., Nigro G. (2019). The interplay between chasing behavior, time perspective, and gambling severity: An experimental study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(2), 259–267. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corless T., Dickerson M. (1989). Gamblers’ self-perceptions of the determinants of impaired control. Addiction, 84(12), 1527–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03936.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosenza M., Ciccarelli M., Nigro G. (2019). The steamy mirror of adolescent gamblers: Mentalization, impulsivity, and time horizon. Addictive Behaviors, 89, 156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosenza M., Matarazzo O., Baldassarre I., Nigro G. (2014). Deciding with (or without) the future in mind: Individual differences in decision-making In Bassis S., Esposito A., Morabito F. (Eds.), Recent advances of neural network models and applications (pp. 435–443). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cronce J. M., Corbin W. R. (2010). Effects of alcohol and initial gambling outcomes on within-session gambling behavior. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18(2), 145–157. doi: 10.1037/a0019114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming S. M., Dolan R. J. (2010). Effects of loss aversion on post-decision wagering: Implications for measures of awareness. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(1), 352–363. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Bateman A., Luyten P. (2012). Introduction and overview In Bateman A., Fonagy P. (Eds.), Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice (pp. 3–41). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Luyten P., Moulton-Perkins A., Lee Y. W., Warren F., Howard S., Ghinai R., Fearon P., Lowyck B. (2016). Development and validation of a self-report measure of mentalizing: The Reflective Functioning Questionnaire. PLoS One, 11(7), e0158678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainsbury S. M., Suhonen N., Saastamoinen J. (2014). Chasing losses in online poker and casino games: Characteristics and game play of Internet gamblers at risk of disordered gambling. Psychiatry Research, 217(3), 220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodie A. S. (2005). The role of perceived control and overconfidence in pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21(4), 481–502. doi: 10.1007/s10899-005-5559-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodie A. S., Fortune E. E., Shotwell J. J. (2019). Cognitive distortions in disordered gambling In Heinz A., Romanczuk-Seiferth N., Potenza M. (Eds.), Gambling disorder (pp. 49–71). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Goodie A. S., MacKillop J., Miller J. D., Fortune E. E., Maples J., Lance C. E., Campbell W. K. (2013). Evaluating the South Oaks Gambling Screen with DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria: Results from a diverse community sample of gamblers. Assessment, 20(5), 523–531. doi: 10.1177/1073191113500522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudriaan A. E., Yücel M., van Holst R. J. (2014). Getting a grip on problem gambling: What can neuroscience tell us? Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 141. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innamorati M., Imperatori C., Harnic D., Erbuto D., Patitucci E., Janiri L., Lamis D. A., Pompili M., Tamburello S., Fabbricatore M. (2017). Emotion regulation and mentalization in people at risk for food addiction. Behavioral Medicine, 43(1), 21–30. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2015.1036831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James R. J., O’Malley C., Tunney R. J. (2016). Loss of control as a discriminating factor between different latent classes of disordered gambling severity. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(4), 1155–1173. doi: 10.1007/s10899-016-9592-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. Y., Lee J. H. (2011). Effects of the BAS and BIS on decision-making in a gambling task. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(7), 1131–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong G., Tsai J., Krishnan-Sarin S., Cavallo D. A., Hoff R. A., Steinberg M. A., Rugle L., Potenza M. N. (2014). A latent class analysis of pathological-gambling criteria among high school students: Associations with gambling, risk and health/functioning characteristics. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 8(6), 421–430. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyngdon A., Dickerson M. (1999). An experimental study of the effect of prior alcohol consumption on a simulated gambling activity. Addiction, 94(5), 697–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9456977.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Berre A. P. (2019). Emotional processing and social cognition in alcohol use disorder. Neuropsychology, 33(6), 808–821. doi: 10.1037/neu0000572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecointe P., Bernoussi A., Masson J., Schauder S. (2016). Affective mentalizing in addictive borderline personality: A literature review. L’Encephale, 42(5), 458–462. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur H. R. (1979). The compulsive gambler’s spiral of options and involvement. Psychiatry, 42(1), 79–87. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1979.11024008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur H. R. (1984). The chase: Career of the compulsive gambler. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman. [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur H. R., Blume S. B. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(9), 1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg A., Fernie B. A., Spada M. M. (2011). Metacognitions in problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27(1), 73–81. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9193-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnet J., Røjskjær S., Nygaard J., Maher B. A. (2006). Episodic chasing in pathological gamblers using the Iowa Gambling Task. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47(1), 43–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00491.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister J. J., Nower L., Wohl M. J. (2016). Gambling goals predict chasing behavior during slot machine play. Addictive Behaviors, 62, 129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyten P., Blatt S. J., Fonagy P. (2013). Impairments in self structures in depression and suicide in psychodynamic and cognitive behavioral approaches: Implications for clinical practice and research. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 6(3), 265–279. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2013.6.3.265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luyten P., Fonagy P., Lemma A., Target M. (2012). Depression In Bateman A., Fonagy P. (Eds.), Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice (pp. 385–417). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Maurage F., de Timary P., Tecco J. M., Lechantre S., Samson D. (2015). Theory of mind difficulties in patients with alcohol dependence: Beyond the prefrontal cortex dysfunction hypothesis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(6), 980–988. doi: 10.1111/acer.12717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride O., Adamson G., Shevlin M. (2010). A latent class analysis of DSM-IV pathological gambling criteria in a nationally representative British sample. Psychiatry Research, 178(2), 401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller C., Karlgren L., Sandell A., Falkenström F., Philips B. (2016). Mentalization-based therapy adherence and competence stimulates in-session mentalization in psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder with co-morbid substance dependence. Psychotherapy Research, 27(6), 749–765. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1158433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morandotti N., Brondino N., Merelli A., Boldrini A., De Vidovich G.Z., Ricciardo S., Abbiati V., Ambrosi P., Caverzasi E., Fonagy P., Luyten P. (2018). The Italian version of the Reflective Functioning Questionnaire: Validity data for adults and its association with severity of borderline personality disorder. PLoS One, 13(11), e0206433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro G., Ciccarelli M., Cosenza M. (2018a). The illusion of handy wins: Problem gambling, chasing, and affective decision-making. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 256–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro G., Ciccarelli M., Cosenza M. (2018b). Tempting fate: Chasing and maladaptive personality traits in gambling behavior. Psychiatry Research, 267, 360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor J., Dickerson M. (2003). Definition and measurement of chasing in off-course betting and gaming machine play. Journal of Gambling Studies, 19(4), 359–386. doi: 10.1023/A:1026375809186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S. H., Poulsen S., Lunn S. (2015). Eating disorders and mentalization: High reflective functioning in patients with bulimia nervosa. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 63(4), 671–694. doi: 10.1177/0003065115602440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. G., Ogeil R. P. (2007). Alcohol consumption and computer blackjack. The Journal of General Psychology, 134(3), 333–353. doi: 10.3200/GENP.134.3.333-354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quester S., Romanczuk-Seiferth N. (2015). Brain imaging in gambling disorder. Current Addiction Reports, 2(3), 220–229. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0063-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridenour J., Knauss D., Hamm J. A. (2019). Comparing metacognition and mentalization and their implications for psychotherapy for individuals with psychosis. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 49(2), 79–85. doi: 10.1007/s10879-018-9392-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T. P. (1997). Modern regression methods. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco P., Torres L. R., Cunningham-Williams R. M., Woods C., Unick G. J. (2011). Differential item functioning of pathological gambling criteria: An examination of gender, race/ethnicity, and age. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27(2), 317–330. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9209-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J. B., Aasland O. G., Babor T. F., de la Fuente J. R., Grant M. (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A., Bentler P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis In von Eye A., Clogg C. C. (Eds.), Latent variables analysis: Applications for developmental research (pp. 399–419). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Schurger A., Sher S. (2008). Awareness, loss aversion, and post-decision wagering. Trends in Cognitive Science, 12(6), 209–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C., Ha C., Carbone C., Kim S., Perry K., Williams L., Fonagy P. (2013). Hypermentalizing in adolescent inpatients: Treatment effects and association with borderline traits. Journal of Personality Disorders, 27(1), 3–18. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2013.27.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe L. (2002). A reformulated cognitive-behavioral model of problem gambling: A biopsychosocial perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(1), 1–25. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00087-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skårderud F. (2007). Eating one’s words, part I: ‘Concretised metaphors’ and reflective function in anorexia nervosa – An interview study. European Eating Disorders Review, 15(3), 163–174. doi: 10.1002/erv.777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada M. M., Roarty A. (2015). The relative contribution of metacognitions and attentional control to the severity of gambling in problem gamblers. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 1, 7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinchfield R. (2002). Reliability, validity, and classification accuracy of the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS). Addictive Behaviors, 27(1), 1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00158-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam M., Chong S. A., Browning C., Thomas S. (2017). Cognitive distortions among older adult gamblers in an Asian context. PLoS One, 12(5), e0178036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B. G., Fidell L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Tackett J. L., Krieger H., Neighbors C., Rinker D., Rodriguez L., Edward G. (2017). Comorbidity of alcohol and gambling problems in emerging adults: A bifactor model conceptualization. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(1), 131–147. doi: 10.1007/s10899-016-9618-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toce-Gerstein M., Gerstein D. R., Volberg R. A. (2003). A hierarchy of gambling disorders in the community. Addiction, 98(12), 1661–1672. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00545.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uekermann J., Channon S., Winkel K., Schlebusch P., Daum I. (2007). Theory of mind, humour processing and executive functioning in alcoholism. Addiction, 102(2), 232–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01656.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volberg R. A. (1993). Gambling and problem gambling among adolescents in Washington State (). Albany, NY: Gemini Research. [Google Scholar]

- Worhunsky P. D., Potenza M. N., Rogers R. D. (2017). Alterations in functional brain networks associated with loss-chasing in gambling disorder and cocaine-use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 178, 363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovenko I., Fortgang R., Prentice J., Hoff R. A., Potenza M. N. (2018). Correlates of frequent gambling and gambling-related chasing behaviors in individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 375–383. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]