Abstract

Background and aims

Vulnerability to stress appears to be a potential predisposing factor for developing specific internet-use disorders, such as Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD). Studies investigating the protective effect of psychological resilience against the impact of perceived stress on IGD and weekly gameplay have yet to be reported in the existing literature. The aim of this study was to examine the potential moderating relationships between perceived stress and online gaming (more specifically operationalized as IGD and weekly gameplay) with psychological resilience.

Methods

An online survey was administered to 605 participants (males = 82%, Mage = 24.01 years, SDage = 6.11). A multivariate multiple regression model was applied to test for the possible contribution of perceived stress and psychological resilience to weekly gameplay and IGD.

Results

Perceived stress was associated with higher scores of IGD, whereas psychological resilience was related to lower scores of IGD. In addition, the combination of having higher perceived stress and lower level of psychological resilience was associated with a particularly high hours of gameplay per week.

Discussion and conclusions

These findings further support the importance of personal traits (perceived stress and psychological resilience) in online gaming (IGD severity and weekly gameplay), and also emphasize the unique moderating relationship between perceived stress and weekly gameplay with lack of resilience. Enhancing psychological resilience to decrease the likelihood of online gamers who experience higher level of stress from spending more hours per week gaming is recommended.

Keywords: gaming, Internet Gaming Disorder, IGD, problematic gaming, resilience, stress

Introduction

There is growing evidence sustaining that Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) constitutes a public health concern, and can have negative consequences (e.g., Rumpf et al., 2018). Despite the ongoing debate about the definition and conceptualization of IGD (e.g., Griffiths et al., 2016; King et al., 2018), recent research demonstrates that problematic gaming is characterized by an extensive engagement in gaming activities in terms of time spent gaming (e.g., displacing other important activities), addictive-like symptoms, and significant impairments in daily life (Marino & Spada, 2017; Pontes & Griffiths, 2015). It has been advocated that compared to the huge numbers of gamers worldwide, only a small proportion is affected by IGD (e.g., Snodgrass et al., 2017). However, the World Health Organization (WHO) recently asserted that the increasing time people spend gaming should be monitored and evaluated as it may constitute a risk factor for developing IGD (WHO, 2018). Based on this assertion, this study included measures of both weekly gameplay (hours) and IGD as outcome variables to simultaneously investigate the role of perceived stress and psychological resilience in explaining both aspects of problematic gaming.

According to a recent model on the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders (i.e., Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution model; Brand, Young, Laier, Wölfling, & Potenza, 2016), vulnerability to stress is a potential predisposing factor for developing specific internet-use disorders. The model highlights that perceived stress resulting from abnormal mood, personal conflicts, or life events may potentially influence how people use the internet (e.g., coping with problems in various psychosocial domains). Perceived stress is defined as the level to which someone tends to perceive stressful situations as uncontrollable, unpredictable, and severe (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). Recent studies have shown perceived stress is positively associated with internet addiction and/or IGD (Che et al., 2017; Rosenkranz, Müller, Dreier, Beutel, & Wölfling, 2017). Highly stressed online gamers may use gaming as a potential vehicle to relieve their preexisting life stress, which might amplify their stress experience (Snodgrass et al., 2014).

According to the General Theory of Addictions (Jacobs, 1986), potential factors that have been found to interact in the relationship between stress and addictive behaviors are personality variables. For example, personality traits moderated the effect of stress on addictive behaviors or decision-making under ambiguity (Canale, Rubaltelli, Vieno, Pittarello, & Billieux, 2017). Among the personality variables, a relevant one is psychological resilience, defined as the ability to adapt to adverse situations in a positive manner (Lussier, Derevensky, Gupta, Bergevin, & Ellenbogen, 2007). Psychological resilience can be considered a resource that helps individuals in coping with adversity, facilitates adequate adjustment, and aids development (Hu, Zhang, & Wang, 2015) because it provides them with the required ability to respond effectively under stressful circumstances (Dyrbye et al., 2010). Consequently, low levels of psychological resilience can be a disadvantage. In fact, tendencies toward lack of psychological resilience when confronted with daily stress have been considered problematic in the context of addicted use of specific internet applications. For instance, Hou et al. (2017) found the association between perceived stress and problematic social networking site (SNS) use was statistically significant for college students who reported a lack of psychological resilience (and not for those with a higher level of psychological resilience). This highlights that psychological resilience may prevent the development of problematic behaviors (e.g., Green, Beckham, Youseef, & Elbogen, 2014) because individuals who report higher levels of psychological resilience are less affected by adverse risks and stress (Roy, Carli, & Sarchiapone, 2011; Stoddard, Zimmerman, & Bauermeister, 2012). Although the potential (modest) protective effects of psychological resilience on SNS/IGD have been reported among Chinese adults/college students (Hou et al., 2017; Wu, Chen, Tong, Yu, & Lau, 2018), studies investigating the protective effect of psychological resilience against the impact of perceived stress on IGD and weekly gameplay have yet to be reported. To date, only one study has tested the moderating effect of psychological resilience in the relationships between psychological distress (depression/anxiety) and IGD, and no significant buffering effect was found in general Chinese adult populations (Wu et al., 2018). However, an important limitation was that they operationalized psychological distress as a combined measure of depression and anxiety, two of the three subscales of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond,1995) while specifically excluding stress (i.e., the third subscale of DASS-21). This omission is important, because their measure of psychological distress did not consider individual vulnerability to stress. However, the degree to which an individual tends to perceive stressful events as uncontrollable, unpredictable, and severe is likely to be a potential predisposing factor for developing IGD (Brand et al., 2016). Consequently, the present study addresses this gap in the literature.

The purposes of this study were to: (a) further confirm the relationship between perceived stress, psychological resilience, and IGD (alongside weekly number of gameplay hours); and (b) test the potential interaction effects of perceived stress with psychological resilience on weekly gameplay and IGD in a general adult sample. It was hypothesized that: (a) perceived stress would be positively related to weekly gameplay and IGD; (b) psychological resilience would be negatively associated with weekly gameplay and IGD; and (c) low psychological resilience would moderate (i.e., strengthen) the association between perceived stress and weekly gameplay and IGD, by showing that the association between perceived stress and weekly gameplay/IGD would be statistically significant for individuals with lower levels of psychological resilience, whereas there would be no significant association for those with a higher level of psychological resilience.

Methods

Procedure and participants

This study utilized a cross-sectional online survey from June 1 to October 15, 2017. Participants were recruited through online advertisements on research-related websites and Facebook groups. Inclusion criteria were: (a) being at least 18 years old, (b) being able to complete the questionnaire in Italian, and (c) reporting online gaming of at least half an hour per week. A total of 699 respondents began the survey, and 87% completed it without any financial incentives. The final sample size was 605 participants (males = 82%; Mage = 24.01 years, SDage = 6.11, age range = 18–61 years). With regard to game genre, 27.5% of the participants reported playing massively multiplayer online games. The average of total number of years of gaming experience was approximately 9 years ranging from 1 to 20 years in the present sample. Other data, not related with this study, will be presented elsewhere.

Measures

Trait perceived stress

Trait perceived stress was assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), which assesses the degree to which life events are appraised as stressful (Cohen et al., 1983; Italian translation: Fossati, 2010). The PSS comprises 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very frequently). Higher scores reflect higher levels of perceived stress in response to stressful situations. The internal consistency of the PSS in this study was 0.83 [95% CI = 0.81–0.85].

Psychological resilience

Psychological resilience was assessed using the 10-item Resilience Scale (RS-10; Wagnild & Young, 1993; Italian version: Peveri, 2010), which assesses the ability to successfully cope with change or misfortune. Responses are rated on a 7-point scale (ranging from disagree to agree). Higher scores represent higher psychological resilience. The internal consistency of the RS-10 in this study was 0.84 [95% CI = 0.82–0.86].

Weekly gameplay

Weekly gameplay reflected participants’ weekly time spent playing on computers, consoles, and/or other gaming platforms (e.g., handheld devices). For this measure, a single item was used: How many hours (if any) do you usually spend on online videogames in a week?

Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD)

The severity of IGD and its detrimental effects over a 12-month period was assessed using the Italian version of the nine-item (short form) of the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale (IGDS9-SF; Monacis, Palo, Griffiths, & Sinatra, 2016; original English version by Pontes & Griffiths, 2015) based on the nine IGD DSM-5 items (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Responses are rated on a 5-point scale (never to very often). On the basis of α = .84 in this study [95% CI = 0.82–0.86], responses were averaged to obtain a synthetic measure, where higher scores represented a higher IGD severity (i.e., minimum 1 and maximum 5).

Sociodemographics

The survey also included questions concerning sociodemographics characteristics of the participants including gender, age, game genre, and gaming experience.

Statistical analysis

To test for the possible contribution of perceived stress and psychological resilience to weekly gameplay and IGD simultaneously, multivariate multiple regression was applied (e.g., for modeling multiple simultaneous dependent variables with a single set of independent variables), using the package lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) of the open-source software R (R Development Core Team, 2013). The covariance matrix of the observed variables was analyzed using a maximum likelihood method estimator. The variables considered for moderation analyses were mean-centered to reduce possible collinearity with interaction terms. To probe the moderating effect, the recommendations of Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken (2003) were followed for the interpretation of the moderation between the dependent variable and the moderator variable. More specifically, the association between the independent variable and the dependent variable was plotted when the levels of the moderator variable were 1 SD below and above the mean value of the moderator variable. Tests of the simple slopes were also performed by testing the statistical significance of each of the two slopes (Aiken, West, & Reno, 1991). According to previous studies that have demonstrated that gender and age (e.g., Hawi, Samaha, & Griffiths, 2018; Kuss & Griffiths, 2012; Lemmens, Valkenburg, & Gentile, 2015) are associated with IGD and weekly gameplay, gender and age were included as control variables in the multivariate multiple regression model. To evaluate the goodness of fit of the multivariate regression model, the R2 of each dependent variable and the total variance explained by the model were considered [total coefficient of determination (TCD); Canale et al., 2016; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996; Marino, Mazzieri, Caselli, Vieno, & Spada, 2018].

Ethics

The ethical committee of the University of Padova provided approval for the study. All participants were informed about the study aims and gave their informed consent prior to the online survey, which took approximately 25 min to complete. This study did not involve human and/or animal experimentation and conformed to all guidelines according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the means, standard deviations (SDs), and bivariate correlations among the study variables. The average amount of weekly gameplay was 22.13 hr (SD = 16.87 hr per week, minimum = 0.5 hr and maximum = 112 hr, skewness = 1.65, kurtosis = 3.90). Almost one third of the sample (27.2%) reported playing games for more than 30 hr per week. The average severity of IGD was small 1.90 (SD = 0.72, range = 1–5, skewness = 1.18, kurtosis = 1.18). The severity of IGD was correlated moderately with playing time per week (r = .32, p < .001). No multicollinearity issues were detected for the multiple regression analyses model. All predictors had tolerance values of at least 0.65 and variance inflation factor (VIF) values below 1.51. Tolerance values over 0.02 and a value under 2.5 for VIF are considered reliable cut-off points for the absence of multicollinearity (Craney & Surles, 2002). In addition, Cook’s distance was used to assess the influence of individual observations on the multivariate multiple regression model for weekly gameplay scores and IGD scores. Cook’s distance was less than 1 (Cook & Weisberg, 1982), so none of the participants fulfilled the criteria for outliers as assessed by Cook’s distance.

Table 1.

Mean (M), standard deviations (SDs), and correlation between variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M (%) | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (males) | – | 82.00 | ||||||

| 2. Age | .04 | – | 24.00 | 6.11 | ||||

| 3. Psychological resilience | −.07 | .09* | – | 5.11 | 1.01 | |||

| 4. Perceived stress | .20*** | −.15*** | −.544*** | – | 2.00 | 0.70 | ||

| 5. Weekly gameplay | −.10* | −.13** | −.15*** | .13** | – | 22.13 | 16.87 | |

| 6. IGD score | −.05 | −.15*** | −.35*** | .39*** | .32*** | – | 1.90 | 0.72 |

Note. IGD: Internet Gaming Disorder.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

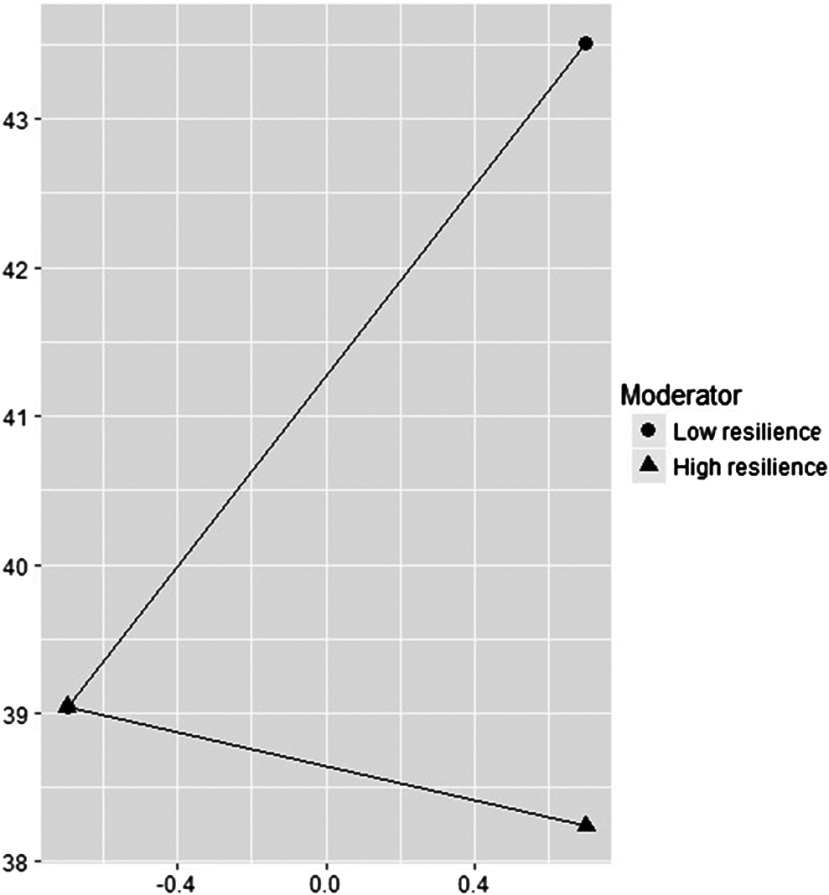

The results from the multivariate multiple regression analyses (Table 2) showed that higher levels of perceived stress were associated with higher IGD scores (β = 0.32, p < .001), whereas higher psychological resilience scores were associated with lower IGD scores (β = −0.17, p < .001). With regard to the control variables, age (β = −0.08, p = .04) and gender (β = −0.13, p = .001) were negatively associated with IGD scores. The results for the weekly gameplay showed that perceived stress and psychological resilience were not associated with gameplay during the week. The two-way interaction between perceived stress and psychological resilience was significantly related to weekly gameplay (β = −0.10, p = .020). To probe the interaction-effect, a simple slope test was conducted (Aiken et al., 1991), which showed weekly gameplay as a function of perceived stress and psychological resilience (Figure 1). The positive association between perceived stress and weekly gameplay was statistically significant among participants with lower levels of psychological resilience (simple slope = 3.41, SE = 1.35, t value = 2.55, p = .011), whereas it was non-significant for those with higher levels of psychological resilience (simple slope = −0.13, SE = 1.43, t value = −0.09, p = .926). This means that low psychological resilience strengthened the association between perceived stress and weekly gameplay. Finally, gender (β = −0.10, p = .009) and age (β = −0.11, p = .006) had a significant negative association with weekly gameplay.

Table 2.

Unstandardized beta (B), the standard error for the unstandardized beta (SE B), the standardized beta (β), and z values for weekly gameplay and Internet Gaming Disorder score

| Weekly gameplay | IGD score | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | z value | p | B | SE B | β | z value | p | |

| Gender (2 = female) | −4.61 | 1.76 | −0.10 | −2.62 | .009 | −0.24 | 0.004 | −0.13 | −3.47 | .001 |

| Age | −0.30 | 0.10 | −0.11 | −2.77 | .006 | −0.01 | 0.004 | −0.08 | −2.06 | .040 |

| Psychological resilience (PR) | −1.22 | 0.80 | −0.08 | −1.62 | n.s. | −0.12 | 0.030 | −0.17 | −3.96 | <.001 |

| Perceived stress (PS) | 1.65 | 1.15 | 0.07 | 1.43 | n.s. | 0.32 | 0.040 | 0.32 | 7.21 | <.001 |

| PR × PS | −1.77 | 0.76 | −0.10 | −2.33 | .020 | 0.02 | 0.030 | 0.03 | 0.81 | n.s. |

| R2 | 0.06 | 0.20 | ||||||||

Note. IGD: Internet Gaming Disorder; SE: standard error.

Figure 1.

Interaction between perceived stress (x axis) and low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of psychological resilience on weekly gameplay (y axis)

The regression model accounted for 20% of the variance of IGD with less variance for weekly hours (i.e., 6%; Table 2). Finally, the total amount variance explained by the multivariate regression model (TCD = 0.22) indicated a good fit to the observed data. In terms of effect size, TCD = 0.22 corresponded to a correlation of r = .47 (which is a medium effect size according to the traditional criteria of Cohen, 1988).

Discussion

This study offers new insight into the psychosocial mechanisms by which perceived stress might influence online gaming. Perceived stress was positively related to IGD. The finding that participants who had high levels of perceived stress were more susceptible to IGD severity compared to participants with low levels of perceived stress supports previous findings (e.g., Che et al., 2017; Rosenkranz et al., 2017), suggesting that individual vulnerability to stress is strongly associated with IGD severity. Online gaming may help individuals to satisfy their need for psychological escape when confronted with challenging and/or stressful situations (Young & de Abreu, 2010). Other possible explanations are that perceived stress may influence: (a) cognitive processes by seeking out immediate reward despite long-term negative consequences; (b) motivation-seeking for reducing stress and/or to experience pleasure (e.g., Brand et al., 2016); and (c) risky decision-making, which is related to IGD (e.g., Ko et al., 2017). Highly stressed online gamers may use online gaming as a way to relieve their perceived life stress (Snodgrass et al., 2014) or may react with withdrawal symptoms when exposed to gaming-related cues (Brand et al., 2016).

This study also found that psychological resilience was negatively associated with IGD. This finding is consistent with a previous Chinese study where psychological resilience was weakly correlated with IGD (Wu et al., 2018). A possible explanation is that resilient individuals might possess some positive characteristics (e.g., high tolerance for negative feelings, a responsible nature, and/or a robust capacity for self-reflection; Vanderpol, 2002), which enable such individuals to be more proactive in challenging situations and being less likely to develop negative behaviors (e.g., problematic gaming; Hou et al., 2017). Moreover, psychological resilience was not negatively associated with weekly gameplay. Previous studies found that some motives (e.g., escapism and coping) are more strongly associated with problematic online gambling than the amount of gaming (e.g., Király, Tóth, Urbán, Demetrovics, & Maraz, 2017; Kircaburun, Jonason, & Griffiths, 2018). Consequently, psychological resilience may help gamers cope with and combat gaming-related symptoms but does not have a coping mechanism role in weekly time spent gaming online.

This is the first study to demonstrate that psychological resilience moderates the relationships between perceived stress and weekly gameplay. More specifically, the results indicated that the relationship between perceived stress and weekly gameplay was positive for students who reported a lack of psychological resilience. It is possible that individuals with a greater vulnerability to stress in combination with a lack of psychological resilience may be more inclined to use dysfunctional and/or impulsive coping strategies, which make them more likely to react with an urge for mood regulation (e.g., going online for stress-relieving capabilities) when confronted with a stressful situation (Brand et al., 2016). Thus, consistent with Garmezy, Masten, and Tellegen’s (1984) protective factor model, specific (positive) personal attributes reduce the negative influence of stress on adaptive behaviors. Moreover, the hypothesized moderating effect of psychological resilience on the association between perceived stress and IGD was not found in this study. It is possible that the protective effect of psychological resilience being less affected by stress or adverse risks helps individuals in being less distracted by an exciting activity such as online gaming (less gameplay), rather that preventing the development of addictive gaming and/or compulsive behavioral patterns.

Consistent with findings reported in previous studies (e.g., Ko, Yen, Chen, Chen, & Yen, 2005; Lee, Ko, & Chou, 2015), gender and age differences were found. More specifically, males and young adults appeared to report more adverse consequences and be more engaged in gaming activities.

This study has some limitations that also need to be considered. First, the data were cross-sectional. Consequently, longitudinal studies are needed to clarify issues relating to causality of the variables examined here. Second, the study comprised a self-selected sample of Italian gamers utilizing self-report methods to collect data. Future research is therefore needed using more nationally representative data and using other methodologies (e.g., comparing objective tracking data online with subjective self-report data; Auer & Griffiths, 2017). Third, the variance explained in the weekly gameplay was only 6% and some effects found in this study were modest. It is possible that the effect of perceived stress and psychological resilience is more salient in emerging adulthood (around age 20 years), a developmental period characterized by important tasks as searching for and accomplishing work and romantic relationship goals (Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004), and by emerging adult-related lifestyle norms that may facilitate addiction problems (Sussman & Arnett, 2014). Considering that experimental studies addressing the reactivity to stress on a subjective and neurobiological level in behavioral addictions are scarce (Canale et al., 2017; Kaess et al., 2017), future studies could test the buffering effect of psychological resilience between stress vulnerability and IGD. Fourth, weekly gaming scores had skewness/kurtosis values >1.5. All these limitations suggest that the results of this study should be interpreted cautiously, and hence further replication studies are warranted. Finally, participants were asked to estimate the weekly time spent playing online video games. Although this measure is consistent with previous works (e.g., King & Delfabbro, 2016; Pontes, & Griffiths, 2015), future studies should also assess the time spent gaming on both weekdays and weekends in order to quantify gaming time more accurately.

Despite these limitations, this is the first study to demonstrate the moderating effect of psychological resilience on the relationship between perceived stress and weekly gameplay. At the practice level, among individuals who lacked resilience, participants with higher levels of perceived stress spent more hours engaged in weekly online gaming (43.5 hr) compared to low stress participants (39 hr). This difference of extra hours could be crucial, considering that disordered gamers typically devote at least 30 hr per week gaming (APA, 2013). Therefore, one avenue for online gaming-related prevention is to contemplate that enhancing psychological resilience may help in decreasing the amount of time spent on weekly online gaming for individuals who face high levels of stress in the life. The finding that psychological resilience is a potential protective factor against IGD might suggest that problematic online gamers could benefit from resilience programs that facilitate social–emotional competence and help develop positive coping skills.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: No external funding source has been received for this study.

Authors’ contribution

NC, CM, and AV are responsible for the study concept and design. NC performed the analysis. CM and AV supervised the statistical analysis and NC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed, revised and approved the final version of the manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aiken L. S., West S. G., Reno R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [APA]. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Auer M., Griffiths M. D. (2017). Self-reported losses versus actual losses in online gambling: An empirical study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(3), 795–806. doi: 10.1007/s10899-016-9648-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M., Young K. S., Laier C., Wölfling K., Potenza M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canale N., Rubaltelli E., Vieno A., Pittarello A., Billieux J. (2017). Impulsivity influences betting under stress in laboratory gambling. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10745-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canale N., Vieno A., Ter Bogt T., Pastore M., Siciliano V., Molinaro S. (2016). Adolescent gambling-oriented attitudes mediate the relationship between perceived parental knowledge and adolescent gambling: Implications for prevention. Prevention Science, 17(8), 970–980. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0683-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che D., Hu J., Zhen S., Yu C., Li B., Chang X., Zhang W. (2017). Dimensions of emotional intelligence and online gaming addiction in adolescence: The indirect effects of two facets of perceived stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1206. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craney T. A., Surles J. G. (2002). Model-dependent variance inflation factor cutoff values. Quality Engineering, 14(3), 391–403. doi: 10.1081/QEN-120001878 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for behavioral science (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Cohen P., West S. G., Aiken L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Kamarck T., Mermelstein R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook R. D., Weisberg S. (1982). Residuals and influence in regression. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye L. N., Power D. V., Massie F. S., Eacker A., Harper W., Thomas M. R., Szydlo D. W., Sloan J. A., Shanafelt T. D. (2010). Factors associated with resilience to and recovery from burnout: A prospective, multi-institutional study of US medical students. Medical Education, 44(10), 1016–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03754.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A. (2010). Traduzione Italiana della scala per lo stress percepito [Italian translation of the Perceived Stress Scale]. Milan, Italy: Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N., Masten A. S., Tellegen A. (1984). The study of stress and competence in children: A building block for developmental psychopathology. Child Development, 55(1), 97–111. doi: 10.2307/1129837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green K. T., Beckham J. C., Youssef N., Elbogen E. B. (2014). Alcohol misuse and psychological resilience among US Iraq and Afghanistan era veterans. Addictive Behaviors, 39(2), 406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D., Van Rooij A., Kardefelt-Winther D., Starcevic V., Király O., Pallesen S., Müller K., Dreier M., Carras M., Prause N., King D. L., Aboujaoude E., Kuss D. J., Pontes H. M., Lopez Fernandez O., Nagygyorgy K., Achab S., Billieux J., Quandt T., Carbonell X., Ferguson C. J., Hoff R. A., Derevensky J., Haagsma M. C., Delfabbro P., Coulson M., Hussain Z., Demetrovics Z. (2016). Working towards an international consensus on criteria for assessing Internet gaming disorder: A critical commentary on Petry et al. (2014). Addiction, 111(1), 167–175. doi: 10.1111/add.13057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawi N. S., Samaha M., Griffiths M. D. (2018). Internet gaming disorder in Lebanon: Relationships with age, sleep habits, and academic achievement. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(1), 70–78. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X. L., Wang H. Z., Guo C., Gaskin J., Rost D. H., Wang J. L. (2017). Psychological resilience can help combat the effect of stress on problematic social networking site usage. Personality and Individual Differences, 109, 61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T., Zhang D., Wang J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs D. F. (1986). A general theory of addictions: A new theoretical model. Journal of Gambling Behavior, 2(1), 15–31. doi: 10.1007/BF01019931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog K. G., Sörbom D. (1996). LISREL 8: User’s reference guide. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Kaess M., Parzer P., Mehl L., Weil L., Strittmatter E., Resch F., Koenig J. (2017). Stress vulnerability in male youth with Internet gaming disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 77, 244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King D. L., Delfabbro P. H. (2016). The cognitive psychopathology of Internet gaming disorder in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(8), 1635–1645. doi: 10.1007/s10802-016-0135-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King D. L., Delfabbro P. H., Potenza M. N., Demetrovics Z., Billieux J., Brand M. (2018). Internet gaming disorder should qualify as a mental disorder. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(7), 615–617. doi: 10.1177/0004867418771189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Király O., Tóth D., Urbán R., Demetrovics Z., Maraz A. (2017). Intense video gaming is not essentially problematic. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(7), 807–817. doi: 10.1037/adb0000316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircaburun K., Jonason P. K., Griffiths M. D. (2018). The Dark Tetrad traits and problematic online gaming: The mediating role of online gaming motives and moderating role of game types. Personality and Individual Differences, 135, 298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ko C. H., Wang P. W., Liu T. L., Chen C. S., Yen C. F., Yen J. Y. (2017). The adaptive decision-making, risky decision, and decision-making style of Internet gaming disorder. European Psychiatry, 44, 189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko C. H., Yen J. Y., Chen C. C., Chen S. H., Yen C. F. (2005). Gender differences and related factors affecting online gaming addiction among Taiwanese adolescents. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193(4), 273–277. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000158373.85150.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss D. J., Griffiths M. D. (2012). Internet gaming addiction: A systematic review of empirical research. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10(2), 278–296. doi: 10.1007/s11469-011-9318-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. H., Ko C. H., Chou C. (2015). Re-visiting Internet addiction among Taiwanese students: A cross-sectional comparison of students’ expectations, online gaming, and online social interaction. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(3), 589–599. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9915-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens J. S., Valkenburg P. M., Gentile D. A. (2015). The Internet Gaming Disorder Scale. Psychological Assessment, 27(2), 567–582. doi: 10.1037/pas0000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond P. F., Lovibond S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier I., Derevensky J. L., Gupta R., Bergevin T., Ellenbogen S. (2007). Youth gambling behaviors: An examination of the role of resilience. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21(2), 165–173. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Mazzieri E., Caselli G., Vieno A., Spada M. M. (2018). Motives to use Facebook and problematic Facebook use in adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 276–283. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino C., Spada M. M. (2017). Dysfunctional cognitions in online gaming and Internet gaming disorder: A narrative review and new classification. Current Addiction Reports, 4(3), 308–316. doi: 10.1007/s40429-017-0160-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monacis L., Palo V. D., Griffiths M. D., Sinatra M. (2016). Validation of the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale – Short-Form (IGDS9-SF) in an Italian-speaking sample. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(4), 683–690. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peveri L. (2010). Resilienza e regolazione delle emozioni. Un approccio multimodale [Resilience and emotion regulation. A multimodal approach] (Doctoral dissertation). Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes H. M., Griffiths M. D. (2015). Measuring DSM-5 Internet gaming disorder: Development and validation of a Short Psychometric Scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/

- Roisman G. I., Masten A. S., Coatsworth J. D., Tellegen A. (2004). Salient and emerging developmental tasks in the transition to adulthood. Child Development, 75(1), 123–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00658.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz T., Müller K. W., Dreier M., Beutel M. E., Wölfling K. (2017). Addictive potential of Internet applications and differential correlates of problematic use in Internet gamers versus generalized Internet users in a representative sample of adolescents. European Addiction Research, 23(3), 148–156. doi: 10.1159/000475984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A., Carli V., Sarchiapone M. (2011). Resilience mitigates the suicide risk associated with childhood trauma. Journal of Affective Disorders, 133(3), 591–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpf H. J., Achab S., Billieux J., Bowden-Jones H., Carragher N., Demetrovics Z., Higuchi S., King D. L., Mann K., Potenza M., Saunders J. B., Abbott M., Ambekar A., Aricak O. T., Assanangkornchai S., Bahar N., Borges G., Brand M., Chan E. M., Chung T., Derevensky J., Kashef A. E., Farrell M., Fineberg N. A., Gandin C., Gentile D. A., Griffiths M. D., Goudriaan A. E., Grall-Bronnec M., Hao W., Hodgins D. C., Ip P., Király O., Lee H. K., Kuss D., Lemmens J. S., Long J., Lopez-Fernandez O., Mihara S., Petry N. M., Pontes H. M., Rahimi-Movaghar A., Rehbein F., Rehm J., Scafato E., Sharma M., Spritzer D., Stein D. J., Tam P., Weinstein A., Wittchen H. U., Wölfling K., Zullino D., Poznyak V. (2018). Including gaming disorder in the ICD-11: The need to do so from a clinical and public health perspective. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(3), 556–561. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass J. G., Dengah H. F., Lacy M. G., Bagwell A., Van Oostenburg M., Lende D. (2017). Online gaming involvement and its positive and negative consequences: A cognitive anthropological cultural consensus approach to psychiatric measurement and assessment. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass J. G., Lacy M. G., Dengah H. F., II, Eisenhauer S., Batchelder G., Cookson R. J. (2014). A vacation from your mind: Problematic online gaming is a stress response. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 248–260. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard S. A., Zimmerman M. A., Bauermeister J. A. (2012). A longitudinal analysis of cumulative risks, cumulative promotive factors, and adolescent violent behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(3), 542–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00786.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S., Arnett J. J. (2014). Emerging adulthood: Developmental period facilitative of the addictions. Evaluation & The Health Professions, 37(2), 147–155. doi: 10.1177/0163278714521812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderpol M. (2002). Resilience: A missing link in our understanding of survival. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 10(5), 302–306. doi: 10.1080/10673220216282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagnild G. M., Young H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1(2), 165–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2018). Gaming disorder. Retrieved November 29, 2018, from http://www.who.int/features/qa/gaming-disorder/en/

- Wu A. M., Chen J. H., Tong K. K., Yu S., Lau J. T. (2018). Prevalence and associated factors of Internet gaming disorder among community dwelling adults in Macao, China. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(1), 62–69. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K. S., De Abreu C. N. (Eds.). (2010). Internet addiction: A handbook and guide to evaluation and treatment. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]