Abstract

Background and aims

Problem gambling is characterized by high stigma and self-stigma, making relevant measurement of the burden of the disorder complex. The aim of our qualitative study was to describe health-related quality of life (HRQOL) impacted by problem gambling from the patients’ perspective.

Methods

We conducted 6 focus groups with 25 current or lifetime at-risk problem gamblers to identify key domains of quality of life impacted by problem gambling. A content analysis from the focus groups data was conducted using Alceste© software, using descendant hierarchical classification analysis, to obtain stable classes and the significant presences of reduced forms. The class of interest, detailing the core of impacted quality of life, was described using a cluster analysis.

Results

Thematic content analysis identified three stable classes. Class 1 contained the interviewers’ speech. Class 3 was composed of the vocabulary related to gambling practice, games and gambling venues (casino, horse betting, etc.). Class 2 described the core of impact of gambling on quality of life and corresponded to 43% of the analyzed elementary context units. This analysis revealed seven key domains of impact of problem gambling: loneliness, financial pressure, relationships deterioration, feeling of incomprehension, preoccupation with gambling, negative emotions, and avoidance of helping relationships.

Conclusions

We identified, beyond objective damage, the subjective distress felt by problem gamblers over the course of the disorder and in the helping process, marked in particular by stigma and self-stigma. Four impacted HRQOL areas were new and gambling-specific: loneliness, feeling of incomprehension, avoidance of helping relationships, and preoccupation with gambling. These results support the relevance of developing, in a next step, a specific HRQOL scale in the context of gambling.

Keywords: quality of life, problem gambling, patient-reported outcome, focus groups, health-related quality of life, qualitative research

Introduction

Problem gambling is responsible for significant impairment and distress (Browne et al., 2016). Negative impact of problem gambling can be reported through objective outcomes, such as financial ones, diagnostic criteria, or gambling-related harms (Browne et al., 2016; Langham et al., 2015), or subjective outcomes, such as quality of life (QOL). Diagnostic criteria as a measurement for negative impact of problem gambling appear to be a conflation of the two concepts (clinical symptoms and harms as an outcome), and a neglect of the possibility that harms may occur with or without an addiction (Browne et al., 2016). Harms are defined by Langham et al. (2015) as any initial or exacerbated adverse consequence due to an engagement with gambling (Langham et al., 2015). QOL is a larger concept than harm related to a particular disease. QOL captures patients’ subjective feelings about domains of functioning that are important to them (Carr, Gibson, & Robinson, 2001). QOL is a concept based on the definition of health given by the WHO in 1948 (EMA, 2005) and has been discussed in the medical literature since the 1960s (Elkinton, 1966). It became more and more important in heath care to measure outcomes beyond morbidity and biological functioning (Karimi & Brazier, 2016). The practice of medicine is often based on the identification and management of symptoms, while patients’ expectations go beyond management of symptoms: they are looking for optimal well-being (Luquiens & Aubin, 2014). In addition, QOL assessment matches with the treatment goal of enhanced client functioning and predict treatment adherence (Laudet, 2011). Moreover, participants with addiction at all stages of recovery expressed concerns about multiple areas of functioning (Laudet, Becker, & White, 2009). QOL is composed of: (a) general QOL, which explores a subjective feeling of satisfaction with life, regardless of any health condition and (b) health-related quality of life (HRQOL) that explores the impact of disease and treatment(s) on one’s daily life (EMA, 2005; Leidy, Revicki, & Genesté, 1999). HRQOL is often included as a secondary endpoint in clinical trials, reflecting patients’ feelings and functioning and the impact of their health condition beyond simple symptom assessment (Carr et al., 2001). HRQOL has been explored in alcohol use disorder through a qualitative analysis: specific impacted areas were found (Luquiens et al., 2015). However, to date, HRQOL specific to problem gambling has not been explored.

Much work has focused on factors that contribute to the development of gambling behavior and gambling disorder. Some researches emphasized the role of environment, including socioeconomic and political aspects (Delfabbro & King, 2017); others, the individual vulnerability in a medical perspective (Livingstone et al., 2018). These different approaches have led to different social representations of gambling, problem gambling, and recovery (Reith & Dobbie, 2012). Studying QOL implies taking these representations into account. The subject’s perception of his/her own reality in a given environment leads to the study of his/her subjectivity rather than symptoms that can be observed from the outside.

Some authors have recently underlined the role of subjectivity in the helping relationships, arguing that all clinical encounters involve a translation between health as a biomedical phenomenon and healing as lived experience (Kristeva, Moro, Ødemark, & Engebretsen, 2018). It has been demonstrated that cooperative relationships contribute in accepting that the truth is subjective (Fisher, Knobe, Strickland, & Keil, 2017). The development of cooperative patient-centered approaches in addiction necessarily involves integrating patients’ subjectivity as the truth to improve (Arpinelli & Bamfi, 2006). Patient’s subjectivity is conditioned by the system of values of the society in which he lives. Problem gambling is characterized by high stigma, as the general population tends to consider problem gamblers as more responsible for their difficulties than are other addicts (Konkolÿ Thege et al., 2015). Stigma is known to be a barrier to help-seeking in problem gambling (Evans & Delfabbro, 2005). In this context, it would be interesting to explore the impact of gambling and related medical care. HRQOL explores subjective impact of a condition and of related treatments (EMA, 2005).

To our knowledge, two instruments measuring HRQOL have been used in the literature in problem gambling studies:

-

(1)

The Medical Outcomes Study Item Short-Form Health Survey and short versions (Brazier, Roberts, & Deverill, 2002; Brazier, Usherwood, Harper, & Thomas, 1998; McHorney, Ware, & Raczek, 1993; Ware, 2000; Ware & GlaxoSmithKline, 2001; Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1996),

-

(2)

The European Quality of Life Questionnaire and the EQ-Visual Analogue Scale (EuroQol Group, 1990; Scott & Huskisson, 1976).

Four domains were identified in these instruments: interpersonal relationships, activities, physical health, and psychological health. No specific instrument to assess QOL of subjects with problem gambling exists to date. Karimi and Brazier (2016) underlined that given HRQOL explores how one disease affects QOL, HRQOL instruments should ideally be specific to the disease of interest. Generic instruments do not necessarily explore the entire spectrum of subjects’ concerns regarding the impact of problem gambling on QOL. There is a potential loss of information due to low specificity and irrelevancy of some of the content of these scales, given the sociocultural component of problem gambling. Moreover, none of these instruments have benefitted from gamblers’ input in their development. Even if they are self-reported ones, the gambler’s perspective is missing, and the relevance of currently assessed areas from the gambler’s perspective is unknown. Documenting the impact of gambling on HRQOL from the patient’s perspective and without any a priori is critical to conceptualize and implement care in a patient-centered approach (Arpinelli & Bamfi, 2006).

HRQOL is a specific type of patient-reported outcome that is defined as any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else (Arpinelli & Bamfi, 2006; EMA, 2005). The best-suited method seems to be the qualitative approach that ensures understanding and completeness of subjective patients’ health condition (Arpinelli & Bamfi, 2006).

The aim of this qualitative study was to describe HRQOL related to problem gambling from patients’ perspective.

Methods

This study was conducted in compliance with the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research guideline (O’Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed, & Cook, 2014).

Sample

Subjects were recruited from three sites in France: (a) Two addiction-specialized treatment services in French hospitals: Paul-Brousse Hospital in Villejuif and Nantes University Hospital; (b) Gamblers Anonymous meetings in Paris. We chose three sites of recruitment to get heterogeneous focus groups in order to explore as much as possible various aspects of the impact of gambling on HRQOL (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007). Subjects with a current or remitted problem gambling were proposed to enter the study by face-to-face contact or telephone call. They were contacted first by their psychiatrist (for outpatients) then the investigator, or directly by the investigator at Gambling Anonymous meetings. They received no financial compensation.

Inclusion criteria were: (a) A Problem Gambling Severity Index of the Canadian Problem Gambling Index (CPGI-PGSI) nine-item score above three during the past 12 months or in the lifetime (we chose this cut-off because a CPGI score up to three is associated with consequences related to gambling and because it allows including described different levels of severity of problem gambling) (Cox, Yu, Afifi, & Ladouceur, 2005; Ferris, Wynne, Ladouceur, Stinchfield, & Turner, 2001); (b) age 18 years or more; (c) subjects had to give their signed and informed consent and had to be affiliated to Social Security. Exclusion criteria were: (a) learning difficulties that prevented reading and responding to questionnaires; (b) major physical comorbidity as judged by the investigator to have a significant influence on the subject’s day-to-day life; (c) major psychiatric comorbidity (clinically assessed by a psychiatrist used to assess mental disorders and able to make diagnoses) that has a significant influence on the subject’s day-to-day life (e.g., acute mania or current major depression); (d) current addictive comorbidity as assessed by clinicians’ judgment (with the exception of nicotine dependence); (e) being unable to give fully informed consent; (f) significant cognitive impairment, clinically assessed; and (g) being under curatorship or guardianship. Demographics and disorder characteristics were collected. Substance use disorders were assessed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.0 (Sheehan et al., 1998).

The focus groups were designed to ensure heterogeneity of the sample while keeping some homogeneity within groups to ease discussion and disclosure. They were made up according to the following variables: age, sex, CPGI-PGSI score, current gambling status, and type of gambling. We decided that no further inclusion was necessary when there was a sampling saturation, that is, when two co-investigators (NAB and AL) estimated that no new topic had been formulated in two successive groups.

Focus groups

The focus groups aimed at exploring the impact on QOL of problem gambling and treatment from gamblers’ point of view. These were semi-structured group interviews that explored a specific domain. This technique is built on the notion that the group interaction encourages respondents to explore and clarify individual and shared perspectives on a health issue (Tong et al., 2007). This technique was also chosen because it was used previously in a similar research (Luquiens et al., 2015). Focus groups were led according to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ; Tong et al., 2007). One trained interviewer (NAB) facilitated the group discussion and used the discussion guide to organize it. The discussion guide was built from the four aforementioned domains identified in the two HRQOL instruments previously used in problem gambling, complimented by three other domains typically explored in general QOL and that could be relevant here: living conditions, financial concerns, and medical care. These QOL domains are classically reported as negative consequences in gambling problem (Langham et al., 2015) and as impacted HRQOL areas in other addictions, as in alcohol use disorder (Luquiens et al., 2015). Participants were initially invited to share their own experience of the impact of gambling on their QOL. During the discussion, if any of the aforementioned domains was not discussed spontaneously, the interviewer proposed it to the participants and made them react. The interviewer focused the discussion on the impact of problem gambling on QOL. Participants were encouraged to talk and interact with each other (Tong et al., 2007). The groups were audio-recorded and transcribed. The duration of the focus groups was around one and a half hours.

Data analysis

The focus groups transcripts were merged to create a corpus (86,348 words, 204 single-spaced pages) that composed an entity due to reference to the same theme, that is, QOL of subjects with problem gambling. We employed content analysis to analyze the corpus. This analysis was facilitated by the textual statistic software Alceste© (ALCESTE, V. 2015, Societé IMAGE, Toulouse, France). We chose this method because it is more adapted to large corpora. In addition, this type of software-assisted analysis limits the analyst’s a priori. This is very valuable given the overuse of politicized and polemical language in academic/scientific contexts that some authors question (Delfabbro & King, 2017). Moreover, the step following the computer-assisted analysis was a work on meaning, because all reduced forms were recontextualized. Indeed, Alceste© conducted lexical analysis using the descending hierarchical classification method to obtain stable classes of words that were the most significant structures of the corpus. It operated in the following four stages: (a) Lemmatization: the words were identified and reduced to their radicals, called a reduced form and classified as “analyzable” (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, etc.) or “supplementary” (prepositions, pronouns, verb “to be” or “to have,” etc.) forms; (b) Text segmentation: the corpus was segmented into elementary context units (ECUs), which were text segments that contained a characteristic idea; (c) Definition of a contingency table of “analyzable” reduced forms occurring at least four times in the corpus called “analyzed forms” and ECUs; and (d) Top-down hierarchical classification analysis performed to obtain stable classes. In each stable class, the most character defining forms were then listed in either their presence or their absence (tested by χ2), comparatively to their presence in the whole corpus (tested by χ2). The parameterization characteristics were: double classification on units of context, a maximum of eight classes after classification. Each analyzed word had to appear at least four times. Then, we qualitatively analyzed theses classes based on both the significant words and the significant ECUs of each class. The χ2 value between words/ECUs and classes enabled the interpretation of classes’ meanings allowing to grasp the ideas that defined each of them. To understand the content of classes, we located back the significant words of each class in the context of its significant ECUs.

One of the classes was considered as the core of QOL, that is, our class of interest. This class was analyzed using cosine similarity method with Alceste©. Cosine similarity method allows building clusters of co-occurring forms that are often together in the same units of context. Lines represent a statistical association between these clusters. To understand the content of each cluster, we located back the significant words of each cluster in the context of its significant ECUs. Thus, we were able to specify what theses clusters meant and their content.

Ethics

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Comité de Protection des Personnes – C.P.P IDF VII on September 3, 2016. All subjects were informed about the study and all provided written informed consent. Confidentiality was preserved.

Results

Six focus groups were conducted in France (two in Nantes and four in Villejuif) with a total of 25 subjects. Demographics and disorder characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. The combined sample represented a large range in terms of sociodemographics, gambling problem severity, and gambling problem status, that is, current or remitted. Saturation was reached across the two last focus groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the focus groups patient sample

| Characteristic | Focus groups sample (n = 25) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean, SD) | 49.5 (14.0) |

| Sex [n (%)] | |

| Male | 17 (68) |

| Female | 8 (32) |

| Relationship status [n (%)] | |

| Married or living as | 12 (48) |

| Not married or living as | 13 (52) |

| Children [n (%)] | |

| Yes | 16 (64) |

| No | 9 (36) |

| Employment status [n (%)] | |

| Working | 15 (60) |

| Not working | 10 (40) |

| Financial difficulties [n (%)] | |

| Yes | 16 (64) |

| No | 9 (36) |

| Lifetime CPGI score (mean, SD) | 16.5 (5.5) |

| Last 12 months CPGI score (mean, SD) | 11.7 (7.2) |

| Age of first gambling experience (mean, SD) | 21.9 (10.5) |

| Age of the beginning of gambling problem (mean, SD) | 37.8 (13.7) |

| Time since the beginning of gambling problem (years) (mean, SD) | 11.7 (11.6) |

| Gambling frequency [n (%)] | |

| No gambling session | 15 (60) |

| <3 gambling sessions a week | 4 (16) |

| ≥ 3 gambling sessions a week | 6 (24) |

| Current gambler [n (%)] | |

| Yes | 10 (40) |

| No | 15 (60) |

| Months since first contact with health services (mean, SD) | 19.5 (14.1) |

| Types of gambling [n (%)] | |

| Scratchcards | 13 (52) |

| Lottery | 9 (36) |

| Horse racing betting | 5 (20) |

| Sports betting | 5 (20) |

| Offline poker | 2 (8) |

| Slot machines | 3 (12) |

| Other casino gambling | 3 (12) |

| Online horse racing betting | 1 (4) |

| Online sports betting | 3 (12) |

| Online poker | 2 (8) |

| Other online gambling | 1 (4) |

| Past substance use disorder (yes) [n (%)] | |

| Alcohol | 6 (24) |

| Opiate | 1 (4) |

| Cocaine | 1 (4) |

| Cannabis | 1 (4) |

| Sedative | 0 |

| Tobacco | 5 (20) |

Note. SD: standard deviation; CPGI: Canadian Problem Gambling Index.

Findings from the focus groups

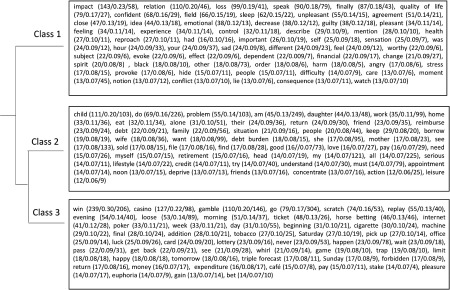

Discussion was smooth. Subjects gave spontaneous positive feedback from the focus groups, and some identified direct benefits from sharing their experiences. One group was marked by highly emotional testimony. Problem gambling was reported by participants to impact a broad spectrum of life domains. The thematic content analysis of the focus group transcripts was performed using Alceste© software that took into account 72% of the ECUs (n = 2,581 ECUs), which is considered to characterize a rich corpus. Thematic content analysis identified three stable classes. Figure 1 presents the dendrogram from the top-down hierarchical classification analysis of the classes and major associated words. Class 1 contained the interviewers’ speech. Class 3 was composed of the vocabulary related to gambling practice, games, and gambling venues (i.e., casino, horse betting, etc.). Class 2 described the core of impact of gambling on QOL and corresponded to 43% of the analyzed ECUs.

Figure 1.

The dendrogram (from top-down hierarchical classification analysis) and the major associated words (χ2 ≥ 12) on the corpus [form (χ2/Φ/frequency)]. Note. Theses major associated words were translated from French to English

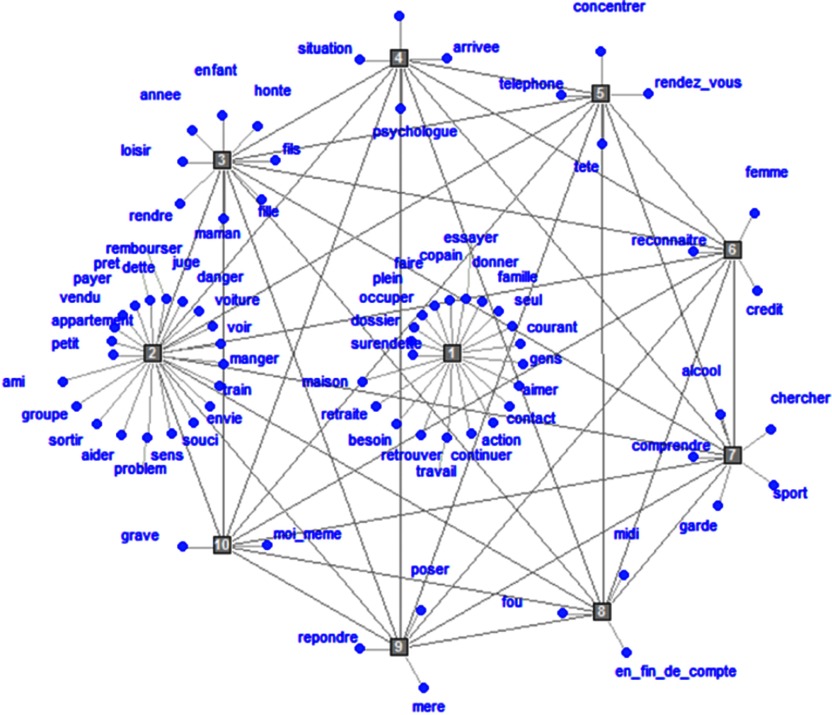

A cluster analysis of this class allowed identifying 10 clusters (Figure 2). Six clusters were considered as very close in content two by two and were grouped into three domains. Clusters 3 and 6 focused on familial relationships deterioration and sentimental relationships deterioration, respectively. We grouped them into one class: relationships deterioration. Clusters 5 and 8 were about ideational encroachment and temporal encroachment, respectively; we considered them as exploring close themes, linked by preoccupation with gambling, and grouped them into one class called preoccupation with gambling. Finally, Clusters 4 and 9 were about difficulties in asking for psychological/medical help and avoiding talking about gambling problem, respectively; we grouped them into one class called avoidance of helping relationships. Seven domains of HRQOL were impacted by problem gambling: loneliness, financial pressure, relationships deterioration, feeling of incomprehension, preoccupation with gambling, negative emotions, and avoidance of helping relationships. The identified domains of impact are described below. Each domain is illustrated by quotes from focus groups’ participants in-text and by additional quotes in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Cluster analysis of Class 2 (French corpus) (cosines similarity). Translation from French to English of the associated words of each cluster cited in proximity order: cluster 1 loneliness: indebtedness, file, to keep busy, full, to make, buddies, to try, to give, family, alone, to fill somebody in, people, to love, contact, action, to keep in, work, to meet up with, need, retirement, and home; cluster 2 financial pressure: small, flat, sold, to pay, loan, debt, to reimburse, judge, danger, car, to see, to eat, ongoing, desire, worry, sense, problem, to help, to go out, group, and friend; cluster 3 relationships deterioration: hobby, year, child, shame, son, daughter, mummy, to realize; cluster 4 avoidance of helping relation: situation, to treat (invisible from this screenshot), to get here, psychologist; cluster 5 preoccupation with gambling: phone, to concentrate, rendez-vous, mind; cluster 6 relationships deterioration: to admit, woman, credit; cluster 7 feeling of incomprehension: to understand, alcohol, to search for, sport; cluster 8 preoccupation with gambling: mad, midday, in the end; cluster 9 avoidance of helping relationships: to answer, to ask, mother; cluster 10 negative emotions: myself, serious. Note. To understand the content of clusters, it is necessary to locate back the significant words of each cluster in the context of its significant ECUs. We cannot provide all the significant ECU’s links to the significant words because of their large number. However, we provided a sufficient number of quotes to allow the reader to understand the meaning of clusters in-text and in-table

Table 2.

Quotes from focus groups’ participants for each domain of health-related quality of life impacted by gambling disorder

| Domain | Focus group | Sex | Age (years) | Quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | V-1 | Woman | 46 | I was no longer myself. I usually love talking to people, being close to them. I cut off myself from the rest of the world |

| V-3 | Man | 27 | Gambling makes me live in my own world. It’s as if you were dragged and after a while people go away | |

| Financial pressure | V-4 | Woman | 60 | I went gambling praying to win because I had to pay back the credit I had got for gambling |

| Relationships deterioration | V-2 | Man | 55 | Due to gambling, my wife is asking for a divorce |

| N-1 | Woman | 42 | One of my children stopped talking to me for an entire month. He wouldn’t talk to me anymore | |

| Feeling of incomprehension | N-1 | Man | 37 | If I explain to someone I know or to a stranger what it is to have an alcohol use disorder or a tobacco use disorder, I guess everybody will get it, but as regards gambling disorder, they won’t |

| V-1 | Woman | 68 | I tried and failed to understand | |

| Preoccupation with gambling | V-2 | Woman | 65 | I try my best to do something else, but I can’t concentrate, it’s like being attracted by a magnet! |

| V-2 | Woman | 65 | Gambling made me forget to catch my children after school | |

| N-1 | Man | 65 | Gambling took up my whole time and life. I had three children but my family was not my priority! Gambling was my priority! | |

| Negative emotions | V-4 | Man | 34 | I’m suffering a lot. I have to work hard on myself |

| N-1 | Man | 37 | [Gambling] can lead to a nervous breakdown and dark thoughts | |

| Avoidance of helping relationship | V-2 | Woman | 65 | I waited too long to come and have a treatment. Last year, even if my children had drawn me with chains to the hospital, I wouldn’t have come |

Note. V: Villejuif; N: Nantes.

Loneliness

Subjects described how gambling cut themselves off from others. They reported that they withdrew into themselves because they were caught up in gambling: “at first, we want to [gamble] in a friendly way, then, afterward, we are on our own, on our own, on our own” (focus group N-1, 37-year-old man). Gambling caused profound loneliness: “to be all stressed out in the corner alone and say to myself: what the fuck happened, how am I gonna get out of it?” (focus group V-4, 71-year-old man). Subjects also described how they felt unable to cope with gambling alone, in particular when they experienced craving: “When we wanted to gamble, then you don’t even have to talk to us” (focus group V-1, 37-year-old man). They described a vicious circle: gambling caused loneliness and loneliness reinforced gambling behavior: “The lack of confidence from those around you is driving you further and further away. And you remain on your own while gambling” (focus group V-2, 65-year-old women).

Financial pressure

Subjects reported having financial harms (credits and debts) that jeopardized the familial financial health and increased anxiety: “When you get a message, you are thinking it’s from the bank. Anxiety grows. It is the same fear of answering to the banker […] Going to the bank feels like a cow that goes to the slaughterhouse” (focus group N-1, 27-year-old man). Chasing was the imputable behavior identified as jeopardizing living conditions. Subjects described feeling constraint to sell their houses, deprivations, and illegal acts (embezzlement, robberies, and prostitution) that increased guilt: “We follow the urges, that’s it. Well, I feel like stealing to play, well, I steal to play, I did. Sad, isn’t it? And then, on the other hand, we lose sleep over it, we blame ourselves for it. Which is fair. It’s good to feel remorse, it’s a shame to feel it afterward, it’s too bad to have done that” (focus group V-1, 27-year-old man).

Relationships deterioration

Participants described that gambling impacted their behavior toward people close to them and had sustainable consequences on their relationships. They experienced damaged social, familial, and intimate relationships, up to the complete disruption of relationships. They reported decreased time spent with relatives. Significant others were less inclined to trust them as lies had several times come up to cover for gambling: “the children say “take care of yourself”: the day when you will recover, we will trust you again” (focus group V-2, 65-year-old woman). Moreover, some participants reported that they came to neglect some of their relatives’ needs. This could lead to staking the money, which they had saved for a birthday present. Participants also described a role reversal with their children: “I would rather help my children than ask them for help” (focus group V-4, 60-year-old woman). For instance, some participants reported having borrowed money from their children. Others had to move in with their children’s after having lost their housing. Participants reported being watched over by their relatives.

Feeling of incomprehension

Participants suffered from not being understood by their relatives. They reported that people did not understand why they gambled excessively. The lack of substance in the addictive process seemed to increase their relatives’ perplexity and limit the relevance of experience from peers suffering from a substance use disorder: “When talking to an alcoholic, I do not understand him and he does not understand me. Every problem is different. I was misunderstood all the time” (focus group V-1, 27-year-old man). In addition, participants reported painful difficulties in understanding their own choices and gambling behavior. They insisted on this point: they were aware that they were putting themselves in danger and that certain thoughts were irrational, but they could not understand how it could happen to them: “You see the danger, the danger is there and you keep going. I don’t understand, I can tell you. It’s a force that attracts you” (focus group V-2, 55-year-old man); “I don’t understand why our brains say: I’m going to chase money. Because every time, we go, we lose, but, even so, we tell ourselves we’re going to gamble again to chase money” (focus group V-4, 34-year-old man). Finally, they often failed to understand their own loss of control: “That’s what’s hard to define. Since you blame yourself for gambling, why are you going back?” (focus group V-1, 68-year-old women).

Preoccupation with gambling

Participants described that gambling became an intrusive obsession that prevented them from concentrating and working, led them to forget duties and appointments, and to lose a sense of time: “I was not efficient at work. As soon as I wanted to be interested in something, I thought about gambling! I loved playing, I had to go playing. It was exhausting” (focus group N-1, 54-year-old man). For instance, some gamblers reported that they could forget to eat at lunchtime or to pick up their children at school: “Gambling made me forget to pick up my children after school” (focus group V-2, 65-year-old woman).

Negative emotions

Subjects expressed a range of negative emotions. Common feelings were guilt, shame, anxiety, depression, and dark thoughts: “And then I shut myself off, sadness” (focus group V-4, 60-year-old woman). Loss of self-esteem was extreme and gamblers could use words that were very hard on themselves: “I tell myself I’m not going to make it, that I’m less than nothing, I insult myself. That I’m less than nothing, that I’m shit, that I’m worthless” (focus group V-4, 60-year-old woman); “Oh I was insulting myself! I was getting lower than the ground” (focus group V-1, 68-year-old woman); “In the end, it’s true that what bothered me the most was feeling like a jerk, stupid and dumb” (focus group V-1, 37-year-old man).

Avoidance of helping relationships

Conceiving excessive gambling as a psychological dysfunction was perceived by participants as a painful process that leads to avoidance of helping relationships: “I just couldn’t understand the psychological side of the problem” (focus group V-4, 34-year-old man). Moreover, participants reported practicing tabooing. They tried very hard to look the same as they always had: “Kids are happy to see you. They want to play. But you’re in total distress. You don’t want to show that distress” (focus group V-2, 55-year-old man); “You’d rather die than have everyone known what you did” (focus group V-1, 68-year-old woman). Tabooing is fueled by the fact that the disorder is often invisible to relatives: “Nobody realized it, since I hadn’t changed my behavior towards others” (focus group V-1, 68-year-old women); “Frankly, no one around me knew I was playing. Including my wife. Nobody, nobody!” (focus group V-2, 55-year-old man); “Compared to an addiction like alcohol or drugs, gambling doesn’t leave a physical trace. It’s definitely harder to detect than other addictions” (focus group V-1, 26-year-old man). They reported an active avoidance of the subject of gambling with their relatives and a psychological tension due to this effort to hide their practice and their loss of control. Different from denial, participants pointed out that, although they felt aware of the excessiveness and irrationality of their behavior, they felt painful to consider problem disorder as a mental disorder and had low perception of self-efficacy to change: “Not only have we lost money, we have lost our self-confidence. There’s no reward. That’s what hurts me the most” (focus group N-2, 65-year-old woman). They avoided the subject of gambling to avoid being asked to change as they felt unable to, and they would rather get out on their own: “I would have wanted to get myself out of my shit and to avoid people the consequences of my gambling” (focus group V-4, 60-year-old woman). They reported difficulty in feeling able to benefit from a helping relationships, as well as fear of coercive measures: “But when they control you, you feel diminished, dependent. Not a help at all” (focus group N-2, 65-year-old woman).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore HRQOL from the patients’ perspective in problem gambling. We conducted a qualitative analysis of focus groups of 25 current or lifetime problem gamblers. We identified seven domains of HRQOL subjectively impacted by problem gambling: loneliness, financial pressure, relationships deterioration, feeling of incomprehension, preoccupation with gambling, negative emotions, and avoidance of helping relationships.

Impact on HRQOL is a different concept from harm related to a particular disease. HRQOL is about catching the subjective suffering of the thinking subject in the particular situation that is being affected by a disease, in the society with its representations, at a particular moment. First, some harms may lead to negligible impact on QOL, whereas others may have a severe impact (Browne & Rockloff, 2017). Second, HRQOL investigates subjectivity, intimacy, and personal perception of a disease on life. It depends conceptually from an individual’s values. However, subjective reporting of QOL has been previously shown to correlate with a range of harms in the addiction field (Luquiens, Falissard, & Aubin, 2016). Therefore, it is important to compare our results to findings on harms related to problem gambling. Our findings are in line with previous high quality works particularly by the Productivity Commission’s (2010) and by Langham et al. (2015) who performed a qualitative work in subjects with problem gambling and significant others. The financial pressure, relationships deterioration, and negative emotions domains, which were found in this study, support findings on harms identified by Langham through the following domains (Langham et al., 2015): financial harms, relationship disruption, conflict or breakdown, and emotional and psychological distress. However, our results allowed the detection of associated suffering in these areas. For instance, indebtedness or financial difficulties are different from financial pressure that catches the personal experience of problem gamblers who have to face creditors’ reminders in anguish and come to avoid picking up the phone or opening their emails. Moreover, four impacted domains found in this study were not mentioned as categories of harms per se in Langham’s study (Langham et al., 2015) nor in HRQOL instruments previously used in problem gambling (Brazier et al., 1998, 2002; EuroQol Group, 1990; McHorney et al., 1993; Scott & Huskisson, 1976; Ware, 2000; Ware & GlaxoSmithKline, 2001; Ware et al., 1996): preoccupation with gambling, loneliness, feeling of incomprehension, and avoidance of helping relationships.

Our analysis supported Langham’s findings on reduced performance at work and relationships disruption but led to the identification of the preoccupation with gambling dimension as an entity. Preoccupation with gambling dimension was characterized by obsessive thoughts about gambling and a lost sense of time. Participants’ input allowed investigation of intimate feelings and bridging of the different domains. Particularly, participants described how preoccupation with gambling was associated with attentional difficulties that secondarily contributed to reduced performance at work. To date, to our knowledge, attentional difficulties were not part of any gambling-specific instrument to assess efficacy or severity of the disorder. We found that obsessive preoccupation for gambling provoked distress in participants. Preoccupation has so far been considered as a symptom for diagnosis. It is the fourth criteria of problem gambling’s diagnosis in DSM-5 – “often preoccupied with gambling” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Our findings support this DSM-5 criterion and enlighten its subjective importance for gamblers. Participants’ input allowed considering distress related to objective clinically observable symptoms. Moreover, a bridge between preoccupation and lack of interest in other activities was also indicated by participants. This is in line with the ICD-11 beta draft description of problem gambling with “increasing priority given to gambling over other activities” (WHO, 2017).

Loneliness is to be distinguished from social isolation or solitude. Participants described feeling lonely as having to face inability to control their gambling behavior alone. From an evolutionary perspective, loneliness could serve as a signal to increase social connection (Cacioppo, Cacioppo, & Boomsma, 2014). However, this signal can act inversely in some people, creating a feeling of a threatening environment and leading to more decreased social contact (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). Loneliness is conceptualized by other authors as a multidimensional concept with two facets: emotional loneliness due to inadequate access to satisfactory social relationships and a social loneliness due to absence of a close relationship with family or love relationship (Porter, Ungar, Frisch, & Chopra, 2004). Links between loneliness and actual isolation are not clear, and loneliness can also occur when being well-surrounded, as a consequence of depression for instance. There is an increasing interest in studying how loneliness and addiction relate, possibly through mediating factors (Dyal & Valente, 2015). Reciprocally, loneliness has been found to mediate marital status and problem gambling in older men (Botterill, Gill, McLaren, & Gomez, 2016). Even if loneliness can be considered as a negative emotion, the importance of this construct for participants justified our choice to make it a dimension on its own. Other authors previously chose to consider loneliness as distinct from other negative emotions (Langham et al., 2015).

Feeling of incomprehension could be a new critical dimension to explore because understanding its own disorder is an important step of care. Psychoeducation strategies widely rely on enabling subjects understanding their functioning and disease. Psychoeducation has been shown to improve QOL of subjects with other mental disorders, as bipolar disorder (Colom & Lam, 2005), but feeling of self-incomprehension had not, to our knowledge, been identified as content of the disorder burden. We believe feeling of self-incomprehension could be the underlying mechanism of some psychological and emotional distress, namely self-stigma. Moreover, considering the feeling of not being understood could be critical to overcome perceived stigma that is consistently reported to be elevated in problem gambling (Birtel, Wood, & Kempa, 2017; Konkolÿ Thege et al., 2015; Langham et al., 2015).

Finally, the avoidance of helping relationships dimension obviously cannot be considered as a dimension of harm. The identification of avoidance of helping relationships dimension as part of QOL of subjects with problem gambling illustrates how harms and QOL are two distinct concepts. Gamblers considered that the intimate process leading them to consider problem gambling as a mental disorder and to ask for help was painful, and thus actively avoided it. The avoidance of helping relationships could be seen as the opposite of acceptance, which has been studied in various chronic illnesses, mainly in chronic pain (Van Bost, Van Damme, & Crombez, 2017). Acceptance is defined as the abandonment of the dominant search for a definitive solution of a disease and a reorientation of attention toward positive aspects of life. Acceptance involves a reevaluation of personal goals, values, and life priorities (Van Damme, Crombez, Van Houdenhove, Mariman, & Michielsen, 2006). Motivational approach is defined as an approach to facilitate and reinforce change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Acceptance could be more explicitly considered as a lever of the motivational approach. The avoidance of helping relationships raises also the stages of change in addiction (Norcross & Prochaska, 2002). It could be interesting to underline the suffering that accompanies change in problem gamblers.

Overall, these last three emerging areas, loneliness, feeling of incomprehension, and avoidance of the helping relationships, could be the demonstration, from the problem gambler’s perspective, of the part of the burden of disorder that is related to society and its representation of problem gambling, beyond the medical conceptualization of the disorder, symptoms, and objective gambling behavior. Objectifying subjectivity and painful processes experienced by problem gamblers could help lower the treatment gap, particularly by promoting empathy, fighting against stigma and self-stigma in this disorder and promoting initiatives to meet gamblers where they are.

Willing to get out of problem gambling by one’s own has been reported to increase the treatment gap. Moreover, if spontaneous remissions have been reported in problem gambling (Fröberg et al., 2015), it has been shown that at least one third of remitted problem gamblers tend to relapse in the following year. Lowering treatment gap is then needed to reduce damages related to problem gambling that increase episode after episode. Our findings could help understand the subjective perspective of problem gamblers that prevent them from treatment access or delay it, actively avoiding the helping relationships. Taking into account the reported difficulties in the helping relationships is critical to innovate and rethink the building of therapeutic alliance with problem gamblers.

A similar study had been conducted by our team in alcohol use disorder. If we tend to highlight the role of self-stigma in the burden of the disorder and its contribution to lower self-esteem in people with an alcohol use disorder, we had not identified such an importance of incomprehension and of avoidance of helping relationships. It appears that the community has not yet realized that gambling is not an ordinary commodity, whereas it has for alcohol many years ago (Babor, Edwards, Caswell, & Caetano, 2004).

The particular representation for gambling disorder in society and its subjective specificities, for some, unexplored in currently used instruments (Pickering, Keen, Entwistle, & Blaszczynski, 2018) supports the relevance of developing, in a next step, a HRQOL scale specific to gambling disorder that could explore the broad spectrum of impacted areas in a single instrument relevant from gamblers’ perspective.

This study presents some limits. First, the lack of an instrument for assessing mental health did not allow documenting comorbidity problems that could also impact the QOL of subjects. Nevertheless, clinicians systematically assessed if there was a significant influence of a disease on the subject’s day-to-day life, which was a non-inclusion criteria. Second, participants were outpatients or people attending mutual-help groups. They could be more advanced in terms of stage of change than non-treatment-seeking gamblers. Given that only around 10% of problem gamblers access to healthcare settings (Suurvali, Cordingley, Hodgins, & Cunningham, 2009), some domains of life could have been left out and some reported one could have taken particular salience in this study. Even if we were very careful to ensure heterogeneity of our sample, and if we included gamblers until having reached saturation of the reported themes, our sample cannot be considered entirely representative. Some additional areas of life may be impacted by problem gambling. Third, some of the groups had a limited size. It could have been interesting to mix groups and individual interviews. However, participant reported feeling comfortable in the proposed setting to share their experience. Finally, some HRQOL domains impacted by gambling were conceptually very closely associated. Although these themes are necessarily intertwined, the gamblers have developed them extensively. Therefore, it seemed justified, in view of the richness of each theme, to leave them separate.

Conclusions

We identified seven domains of HRQOL subjectively impacted by problem gambling. Moreover, subjectivity allowed the emergence of additional unreported areas as part of the disorder burden and impacting problem gamblers’ QOL: loneliness, feeling of incomprehension, avoidance of helping relationships, and preoccupation with gambling. Beyond symptoms and a list of negative consequences, this qualitative work allowed identifying the additional and subjective part of the burden that seems to be related to the representation of gambling disorder in the community characterized by stigma. Considering these subjective dimensions could contribute to developing the patient-centered approach in problem gambling, rethinking care, and finally reducing the treatment gap. These results support the relevance of developing, as a next step, a specific HRQOL scale in the context of gambling disorder.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the “Fondation des Gueules Cassées” for their helpful contribution.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: None.

Authors’ contribution

NAB, AL, and H-JA drafted the protocol. NAB, AL, MG-B, and JC have built the focus groups. NAB led the focus groups. NAB and AL analyzed the data. NAB generated items and drafted the manuscript. H-JA, AL, AB, MG-B, JC, and FL critically revised the protocol and the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

MG-B and JC received the endowment fund of the Nantes University Hospital, collects donations of gambling operators (FDJ and PMU) in the form of corporate sponsorship. Scientific independence is guaranteed. AL has received sponsorship to attend scientific meetings, speaker honoraria, and consultancy fees from Lundbeck and Indivior. He is investigator in studies founded by public grants implying a collaboration with Winamax and with the ARJEL. NAB, FL, AB, and H-JA have no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Arpinelli F., Bamfi F. (2006). The FDA guidance for industry on PROs: The point of view of a pharmaceutical company. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4(1), 85. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor T., Edwards G., Caswell S., Caetano R. (2004). Alcohol: No ordinary commodity – Research and public policy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Birtel M. D., Wood L., Kempa N. J. (2017). Stigma and social support in substance abuse: Implications for mental health and well-being. Psychiatry Research, 252, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botterill E., Gill P. R., McLaren S., Gomez R. (2016). Marital status and problem gambling among Australian older adults: The mediating role of loneliness. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(3), 1027–1038. doi: 10.1007/s10899-015-9575-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier J., Roberts J., Deverill M. (2002). The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. Journal of Health Economics, 21(2), 271–292. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00130-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier J., Usherwood T., Harper R., Thomas K. (1998). Deriving a preference-based single index from the UK SF-36 Health Survey. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 1115–1128. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00103-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne M., Langham E., Rawat V., Greer N., Li E., Rose J., Rockloff M., Donaldson P., Thorne H., Goodwin B., Bryden G., Best T. (2016, April 11). Assessing gambling-related harm in Victoria: A public health perspective. Retrieved May 25, 2017, from https://www.responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/information-and-resources/research/recent-research/assessing-gambling-related-harm-in-victoria-a-public-health-perspective

- Browne M., Rockloff M. J. (2017). The dangers of conflating gambling-related harm with disordered gambling. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 317–320. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J. T., Cacioppo S., Boomsma D. I. (2014). Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cognition and Emotion, 28(1), 3–21. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2013.837379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A. J., Gibson B., Robinson P. G. (2001). Measuring quality of life: Is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? BMJ, 322(7296), 1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom F., Lam D. (2005). Psychoeducation: Improving outcomes in bipolar disorder. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 20(5–6), 359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox B. J., Yu N., Afifi T. O., Ladouceur R. (2005). A national survey of gambling problems in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 50(4), 213–217. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfabbro P., King D. (2017). Gambling is not a capitalist conspiracy: A critical commentary of literature on the ‘industry state gambling complex’. International Gambling Studies, 17(2), 317–331. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2017.1281994 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyal S. R., Valente T. W. (2015). A systematic review of loneliness and smoking: Small effects, big implications. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(13), 1697–1716. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1027933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkinton J. R. (1966). Medicine and the quality of life. Annals of Internal Medicine, 64(3), 711–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-64-3-711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMA. (2005). Reflection paper on the regulatory guidance for the use of health-related quality of life (HRQL) measures in the evaluation of medicinal products. London, UK: Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. [Google Scholar]

- EuroQol Group. (1990). EuroQol – A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 16(3), 199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans L., Delfabbro P. H. (2005). Motivators for change and barriers to help-seeking in Australian problem gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21(2), 133–155. doi: 10.1007/s10899-005-3029-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris J., Wynne H., Ladouceur R., Stinchfield R., Turner N. (2001). The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: Final report (p. 59). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M., Knobe J., Strickland B., Keil F. C. (2017). The influence of social interaction on intuitions of objectivity and subjectivity. Cognitive Science, 41(4), 1119–1134. doi: 10.1111/cogs.12380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröberg F., Rosendahl I. K., Abbott M., Romild U., Tengström A., Hallqvist J. (2015). The incidence of problem gambling in a representative cohort of Swedish female and male 16–24 year-olds by socio-demographic characteristics, in comparison with 25–44 year-olds. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(3), 621–641. doi: 10.1007/s10899-014-9450-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L. C., Cacioppo J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M., Brazier J. (2016). Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: What is the difference? PharmacoEconomics, 34(7), 645–649. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkolÿ Thege B., Colman I., el-Guebaly N., Hodgins D. C., Patten S. B., Schopflocher D., Wolfe J., Wild T. C. (2015). Social judgments of behavioral versus substance-related addictions: A population-based study. Addictive Behaviors, 42, 24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristeva J., Moro M. R., Ødemark J., Engebretsen E. (2018). Cultural crossings of care: An appeal to the medical humanities. Medical Humanities, 44(1), 55–58. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2017-011263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langham E., Thorne H., Browne M., Donaldson P., Rose J., Rockloff M. (2015). Understanding gambling related harm: A proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 80. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2747-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet A. B. (2011). The case for considering quality of life in addiction research and clinical practice. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 6(1), 44–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet A. B., Becker J. B., White W. L. (2009). Don’t wanna go through that madness no more: Quality of life satisfaction as predictor of sustained remission from illicit drug misuse. Substance Use & Misuse, 44(2), 227–252. doi: 10.1080/10826080802714462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidy N. K., Revicki D. A., Genesté B. (1999). Recommendations for evaluating the validity of quality of life claims for labeling and promotion. Value in Health: The Journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 2(2), 113–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.1999.02210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone C., Adams P., Cassidy R., Markham F., Reith G., Rintoul A., Schull N. D., Woolley R., Young M. (2018). On gambling research, social science and the consequences of commercial gambling. International Gambling Studies, 18(1), 56–68. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2017.1377748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luquiens A., Aubin H.-J. (2014). Patient preferences and perspectives regarding reducing alcohol consumption: Role of nalmefene. Patient Preference and Adherence, 8, 1347–1352. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S57358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luquiens A., Falissard B., Aubin H. J. (2016). Students worry about the impact of alcohol on quality of life: Roles of frequency of binge drinking and drinker self-concept. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 167, 42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luquiens A., Whalley D., Crawford S. R., Laramée P., Doward L., Price M., Hawken N., Dorey J., Owens L., Llorca P. M., Falissard B., Aubin H. J. (2015). Development of the Alcohol Quality of Life Scale (AQoLS): A new patient-reported outcome measure to assess health-related quality of life in alcohol use disorder. Quality of Life Research, 24(6), 1471–1481. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0865-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney C. A., Ware J. E., Raczek A. E. (1993). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care, 31(3), 247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W., Rollnick S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norcross J., Prochaska J. (2002). Using the stages of change. Harvard Mental Health Letter, 18(11), 5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien B. C., Harris I. B., Beckman T. J., Reed D. A., Cook D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89(9), 1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering D., Keen B., Entwistle G., Blaszczynski A. (2018). Measuring treatment outcomes in gambling disorders: A systematic review. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 113(3), 411–426. doi: 10.1111/add.13968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J., Ungar J., Frisch G. R., Chopra R. (2004). Loneliness and life dissatisfaction in gamblers. Journal of Gambling Issues, 11, 1–12. doi: 10.4309/jgi.2004.11.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Productivity Commission. (2010). Gambling. Canberra, Australia: Productivity Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Reith G., Dobbie F. (2012). Lost in the game: Narratives of addiction and identity in recovery from problem gambling. Addiction Research & Theory, 20(6), 511–521. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2012.672599 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J., Huskisson E. C. (1976). Graphic representation of pain. Pain, 2(2), 175–184. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(76)90113-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D. V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K. H., Amorim P., Janavs J., Weiller E., Hergueta T., Baker R., Dunbar G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl. 20), 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suurvali H., Cordingley J., Hodgins D. C., Cunningham J. (2009). Barriers to seeking help for gambling problems: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(3), 407–424. doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9129-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bost G., Van Damme S., Crombez G. (2017). The role of acceptance and values in quality of life in patients with an acquired brain injury: A questionnaire study. PeerJ, 5, e3545. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme S., Crombez G., Van Houdenhove B., Mariman A., Michielsen W. (2006). Well-being in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: The role of acceptance. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61(5), 595–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J. E. (2000). SF-36 health survey update. Spine, 25(24), 3130–3139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J. E., & GlaxoSmithKline. (2001). How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: A manual for users of the of the SF-8 health survey : (With a supplement on the SF-6 health survey). Lincoln, RI/Boston, MA: QualityMetric, Inc./Health Assessment Lab. [Google Scholar]

- Ware J. E., Kosinski M., Keller S. D. (1996). A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 34(3), 220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2017). ICD-11 beta draft. Washington, DC: WHO; Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/f/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f960730313 [Google Scholar]