Abstract

Background and aims

Responsible gambling (RG) tools and initiatives have been introduced by social RG operators as a means to help prevent problem gambling. One such initiative is the use of mandatory play breaks (i.e., forced session terminations). Recommendations by RG experts for gambling operators to implement mandatory play breaks appear to be intuitively sensible but are not evidence-based.

Methods

The present authors were given access by the Norwegian gambling operator Norsk Tipping to data from 7,190 video lottery terminal (VLT) players who gambled between January and March 2018. This generated 218,523 playing sessions for further analysis. Once a gambling session reaches a 1-hr play duration, a forced session termination of 90 s comes into effect. This study evaluated the effect of mandatory play breaks on subsequent gambling.

Results

Compared to similar sessions identified using a matched-pairs design, results demonstrated that there was no significant effect of the forced termination regarding the amount of money staked in the subsequent gambling session or on the time duration of the subsequent gambling session.

Conclusions

Although expenditure was higher in the subsequent 24 hr for terminated sessions, this is likely due to higher intensity gamblers being more likely to trigger mandatory breaks. Implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: gambling, responsible gambling, responsible gambling tools, problem gambling, mandatory play breaks, forced session termination

Introduction

In the gambling studies field, responsible gambling (RG) has become an important topic for researchers, regulators, policymakers, and the gaming industry. RG tools and initiatives have been introduced by social RG operators as a means to help players gamble more responsibly and to help in the prevention of problem gambling (Harris & Griffiths, 2017). One such initiative is the use of mandatory play breaks. In a comprehensive review of RG tools and social responsibility in gambling initiatives, Griffiths (2012) recommended that continuous gambling games (i.e., any game that can be played continually without breaks such as the rapid, high event frequency slots games) should feature a mandatory break after 1 hr of continuous gambling. He also recommended that this break “should be for at least five minutes (if not longer)” (p. 239) for two reasons. First, such a break was deemed as important for gamblers who find it difficult to stick with self-imposed limits. Second, enforced breaks in play provide gamblers with a reflective “time out” (i.e., “cool off”) period allowing a gambler to think more rationally about whether they want to continue playing. Griffiths also asserted that such breaks inhibit a player from using gambling as a way to escape from their problems by entering into a dissociative (trance-like) state through continuous gambling (Griffiths, Wood, Parke, & Parke, 2006; Wood & Griffiths, 2007).

Such a recommendation concerning mandatory play breaks appears to be intuitively sensible but was not evidence-based (mainly because there was no empirical evidence at the time, the recommendations were made). It has been claimed that RG initiatives that force gamblers to take a break in play provide a mechanism for dissociative states to be broken and that such initiatives are derived from robust theoretical underpinnings. However, Harris and Griffiths (2017) noted that

The use of enforced breaks in play…may be challenged on theoretical grounds, which indicate that breaks in play may actually have an adverse effect on the gambler. For example, the Behaviour Completion Mechanism Model (McConaghy, 1980) posits that driven behaviours, which includes pathological gambling, build a neuronal model of behaviour which is facilitated by conditioning effects. Exposure to a conditioned stimulus or cue results in the activation of the neuronal model, and any interruption to the expression of the behaviour results in an aversive state, or a state of craving, which drives the individual to the completion of the behaviour (Blaszczynski, Cowley, Anthony, & Hinsley, 2015). Recent research testing the efficacy of imposing breaks in play as an RG tool challenges the use of breaks in play as a standalone RG approach. (p. 199)

To date (and to the present authors’ knowledge), only one study has ever empirically investigated the direct effects of play breaks in gambling. In a laboratory-based study, Blaszczynski et al. (2015) tested various lengths of breaks in play and their impact on gambling cravings. The study comprised university students (n = 141; 78 females) who played a simulated electronic blackjack game for 15 min. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions (8-min play break, 3-min play break, or no break at all). Using the Gambling Craving Scale (Young & Wohl, 2009), Blaszczynski et al. reported that participants’ craving was significantly higher in the 8-min break condition compared with the other two conditions (and those in the 3-min break condition had significantly higher craving than in the no break condition). The study also reported no difference in levels of dissociation in the three groups (using Jacobs’, 1988 Dissociative Experience Scale), although there was a significant positive correlation between cravings and feelings of dissociation (and therefore supporting the theoretical position for dissociation’s role in the continuation of within-session gambling). These findings suggest that enforcing breaks in gambling play may have unintended consequences and that play breaks alone may not be a good standalone RG initiative for gambling operators to implement (e.g., play breaks accompanied by RG messaging may be more effective).

However, there are some major limitations of the study particularly in relation to ecological validity. The number of participants was very small, the participants were not gamblers (i.e., they were all university students), and the participants did not actually gamble because they played a simulated gambling game in which no real money was involved. It is also arguable whether 8 min constitutes a “long” play break. It may be that much longer breaks are needed for cravings and dissociative feelings to dissipate. Furthermore, 15 min of continuous play is unlikely have been enough time for participants to have reached a dissociative state. Consequently, the efficacy of enforced play breaks should not be disregarded based on the results of this study alone.

Landon, Palmer du Preez, Bellringer, Page, and Abbott (2016) studied views and experiences of pop-up messages from a range of gamblers and gambling venue staff. They found that venue staff members viewed pop-up messages much more negatively than gamblers. Venue staff members were also very negative about the additional hassles and confusion for players. However, they believed that pop-up messages were useful in reducing gambling-related harm.

Two other peripherally related real-world studies (i.e., Auer & Griffiths, 2015; Auer, Malischnig, & Griffiths, 2014) examined whether gambling operators using pop-up messages could persuade players to stop their gambling after 1,000 consecutive plays (approximately 1 hr of gambling) on an online slot machine. In the first study (Auer et al., 2014) comprising approximately 50,000 online gamblers, approximately 1% of the sessions that lasted 1,000 consecutive games (45 sessions out of 4,205) led to a play break by the gamblers when they viewed a “simple” pop-up message (“You have now played 1,000 slot games. Do you want to continue?”). In the second study (i.e., Auer & Griffiths, 2015) comprising approximately 70,000 online gamblers, the efficacy of two different pop-up messages [“simple” (same as the aforementioned study) vs. “enhanced” (“We would like to inform you, that you have just played 1,000 slot games. Only a few people play more than 1,000 slot games. The chance of winning does not increase with the duration of the session. Taking a break often helps, and you can choose the duration of the break”)] in getting players to take a break in play were compared. In the “simple” pop-up condition, 0.67% of the sessions that lasted 1,000 consecutive games (75 sessions out of 11,232) led to a play break by the gamblers. In the “enhanced” pop-up condition, 1.39% of the sessions that lasted 1,000 consecutive games (169 sessions out of 11,878) led to a play break by the gamblers.

Given the lack of empirically based studies examining the effect of mandatory play breaks (i.e., forced terminations) on subsequent gambling behavior, this study was a real-world investigation using behavioral tracking data supplied by a gambling operator. Given the paucity of previous research, this study was exploratory and there were no specific hypotheses. However, the authors speculated that the 90-s mandatory play break would perhaps lead to reduced monetary stakes during the following session following termination. It was also speculated that mandatory play break may lead to a longer break until the start of the next gambling session. This study also investigated whether the mandatory play break would reduce gambling intensity during the next 24 hr. None of these types of evaluation have ever been tested previously with real-world gamblers.

Methods

Participants

The authors were given access by Norsk Tipping to 7,190 Belago video lottery terminal (VLT) players who gambled between January and March 2018. This represents a 20% random sample of all active Belago players at the same time period. Belago is one of two VLT products that Norsk Tipping offers adults who reside in Norway. Belago VLTs are located in bingo halls across Norway. At Norsk Tipping, all gambling behavior is identified via a player card and each and every player’s gambling behavior is tracked across game types. VLTs can only be played with a personalized player card and a personal pincode. Apart from VLTs, Norsk Tipping also offers lottery games, online casino games, and sports betting. The maximum loss per day on Belago VLTs is limited to 900 Norwegian Krone (NOK; approx. €90) and the maximum loss per month is limited to NOK 4,400 (approx. €440). Across all game types, Norsk Tipping players’ loss is limited to NOK 20,000 (approx. €2,000) per month. The average age of the 7,190 players in the present sample was 48.52 years (SD = 16.25) and 36.3% of the players were female. There was a significant difference in age (t = 3.68, p < .001) between males (mean = 50.3 years, SD = 14.7) and females (mean = 53.6 years, SD = 16.3).

Between January and March 2018, the active players in that time period generated 218,523 playing sessions. A player was regarded as “active” if at least one game was played. A session starts when a player inserts the personal player card into the VLT and types in a personal pincode and it ends when the player card is removed. One RG tool used by Norsk Tipping is a forced session termination, followed by a short mandatory play break. One in 28 Belago VLT sessions (n = 7,666) was terminated by Norsk Tipping between January and March 2018 because the session duration lasted 60 min (i.e., 4%). The termination does not always happen at exactly 60 min, because sessions are not terminated while the player is playing a game. The termination is followed by a 90-s mandatory break during which the player cannot begin another playing session. Not every mandatory play break lasts exactly 90 s due to technical issues (but the vast majority do).

In this study, three metrics were examined: (a) the time until the next session (i.e., the number of minutes from the end time of the last game of a session until the start time of the first game of the next session), (b) the next session’s gambling intensity (i.e., the total amount wagered across the whole of the next session across all games played), and (c) the gambling intensity during the next 24 hr (i.e., the amount staked on all games during the 24 hr after the last game of a session).

Rationale for matched-pairs design

The aim of this study was to determine whether the forced session termination and the subsequent mandatory 90 s play break had an effect on the time until the next gambling session starts, the size of the next session’s stake, and the amount wagered during the next 24 hr. To conduct a controlled experiment, the authors would have to contain access to sessions, which were not subject to a forced termination. This would allow for the establishment of a cause and effect relationship between the session termination and subsequent gambling behavior. However, this was not possible. Therefore, in order to be able to investigate the effect of the termination, the authors decided to follow a matched-pairs design similar to that used by Auer and Griffiths (2015; Auer, Hopfgartner, & Griffiths, 2018). Matched-pairs designs are often applied when an experimental design is not possible or feasible (Larsen, Larouche, Buliung, & Faulkner, 2018; Quanbeck et al., 2018). For each of the 7,666 sessions that were terminated, the present authors attempted to identify most similar sessions, which were not terminated.

For the 218,523 sessions (including the 7,666 terminated sessions), the amount of money staked, won, and session duration was computed. Subsequently, for the 7,666 terminated sessions, most similar sessions with respect to the three aforementioned criteria were matched. The amount of money staked had to be within 2% of the terminated session’s criteria. If a terminated session’s amount of money staked was NOK 100, the matched session’s stake had to be between NOK 98 and NOK 102. The amount of money won had to be within 5% of the terminated session’s amount won. This larger percentage is due to the fact that the amount of money won is much more influenced by chance than the amount of money staked. If a terminated session’s amount of money won was NOK 50, the matched session’s amount of money won had to be between NOK 47.5 and NOK 52.5, and if a terminated session lasted for 60 min, the matched session had to last between 54 and 66 min. In addition, only sessions that lasted for at least 55 min were considered for comparison. A matched session had to be from a different player to that of the terminated session. Out of the 7,666 terminated sessions, 3,376 were removed from population because no session could be matched according to the aforementioned criteria. This means that the final sample comprised 4,290 terminated sessions. The 4,290 sessions comprised 1,331 players. Of these, 553 of the players had one terminated session (42%), 268 players had two terminated sessions (20%), and 510 players had three or more sessions (38%). The 4,290 sessions for which a match was found had a median and mean stake of NOK 2,399 and NOK 3,111, respectively. The median and mean session duration was 59 min. The 3,290 sessions for which no match was found had a median and mean stake of NOK 1,808 and NOK 3,112, respectively. The median session duration was 59 min and the mean session duration was 60 min. A Mann–Whitney U Test was significant for both stake and session durations (W = 61,29,000, p < .001; W =82,36,000, p < .001).

For the 4,290 terminated sessions for which at least one matched session was found, the most similar session was selected. To determine the most similar non-terminated session, the percentage deviations regarding the amount of money staked in a session, amount of money won in a session, and session duration were computed. Non-parametric statistical tests (Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for matched pairs) were conducted. According to the Shapiro–Wilk normality test, the amount of money staked per session (W = 0.835, p < .001), amount of money won per session (W = 0.814, p < .001), and session length duration (W = 0.761, p < .001) were not normally distributed. Moreover, the play break duration length following the sessions had a non-normal distribution (W = 0.211, p < .001).

Ethics

Ethical approval for the study was given by the research team’s university ethics committee and was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

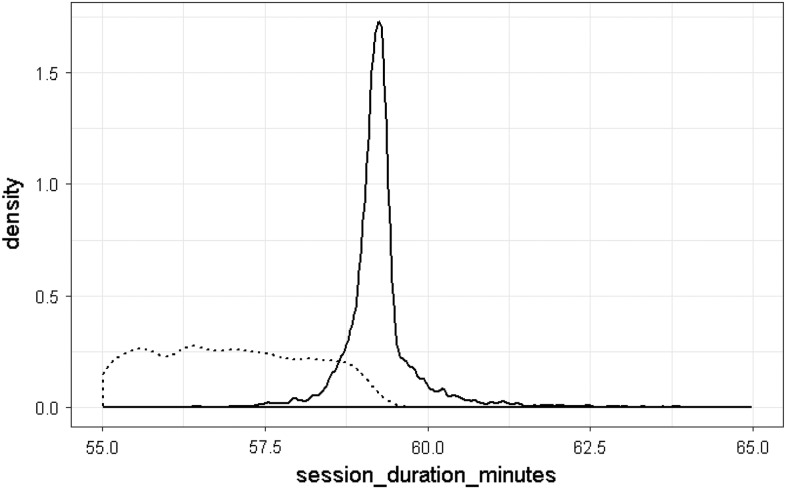

Table 1 reports the amount staked, amount won, and session duration for the terminated and matched non-terminated sessions, respectively. Terminated sessions had a median amount staked of NOK 2,399. The matched non-terminated sessions’ median amount staked was NOK 2,418. The corresponding mean average values were NOK 3,111 and NOK 3,112. Terminated sessions’ median amount won was NOK 2,366. The matched non-terminated sessions’ median amount won was NOK 2,377. The corresponding mean average values for median amount won were NOK 3,191 and NOK 3,190. The median playing duration of terminated sessions was 59.2 min and that of the matched non-terminated sessions was 56.9 min. The corresponding mean average values were 59.3 and 57.0 min.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for terminated sessions and matched non-terminated sessions

| P25 | Median | Mean | P75 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of money staked (NOK) | Terminated | 1,544 | 2,399 | 3,111 | 3,810 |

| Matched | 1,543 | 2,418 | 3,112 | 3,813 | |

| Amount of money won (NOK) | Terminated | 1,452 | 2,366 | 3,191 | 3,939 |

| Matched | 1,445 | 2,377 | 3,190 | 3,948 | |

| Session length duration (min) | Terminated | 59.0 | 59.2 | 59.3 | 59.4 |

| Matched | 55.9 | 56.9 | 57.0 | 58.0 | |

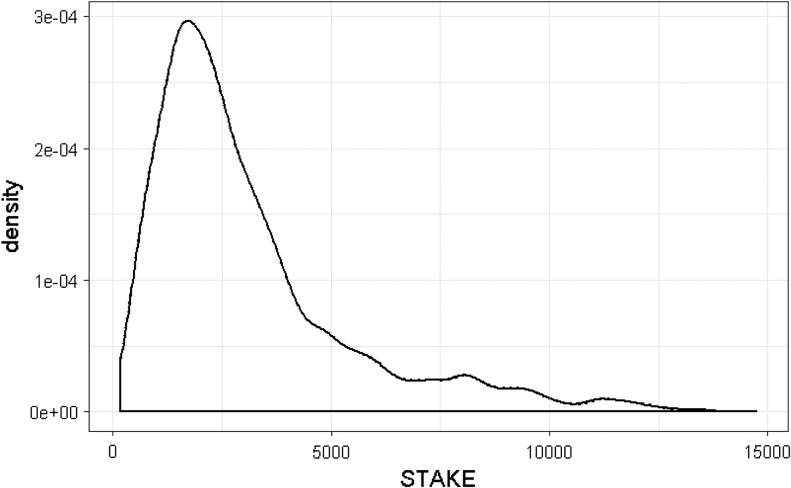

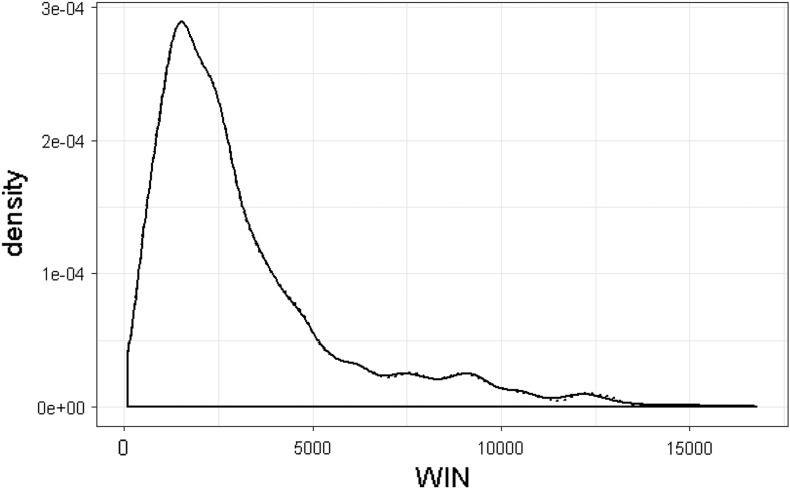

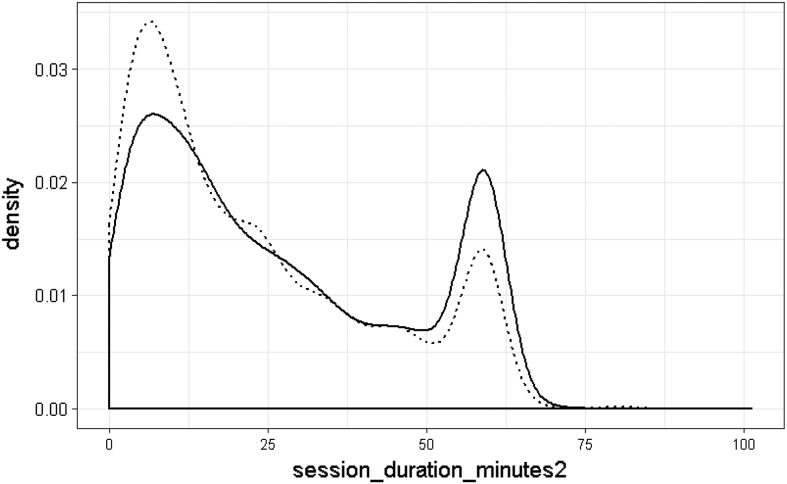

Figure 1 displays the distribution of the amount staked per session for terminated and matched non-terminated sessions. Figure 2 displays the distribution of the amount of money won per session for terminated and matched non-terminated sessions. There was no significant difference between the terminated and the matched non-terminated sessions with respect to amount of money staked per session (V = 43,48,500, p = .073) and amount of money won per session (V = 46,68,200, p = .14). Figure 3 displays the session length duration for the terminated and the matched non-terminated sessions. The session length duration of the terminated sessions was slightly longer. This is to be expected because the termination depends on the session duration. This difference was significant (V = 91,48,000, p < .001).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the amount of money staked for terminated (solid) and matched non-terminated sessions (dotted). Note. The two curves are so similar that hardly any difference is visible

Figure 2.

Distribution of the amount of money won for terminated (solid) and matched non-terminated sessions (dotted). Note. The two curves are so similar that hardly any difference is visible

Figure 3.

Distribution of the session length duration in minutes for terminated (solid) and matched non-terminated sessions (dotted)

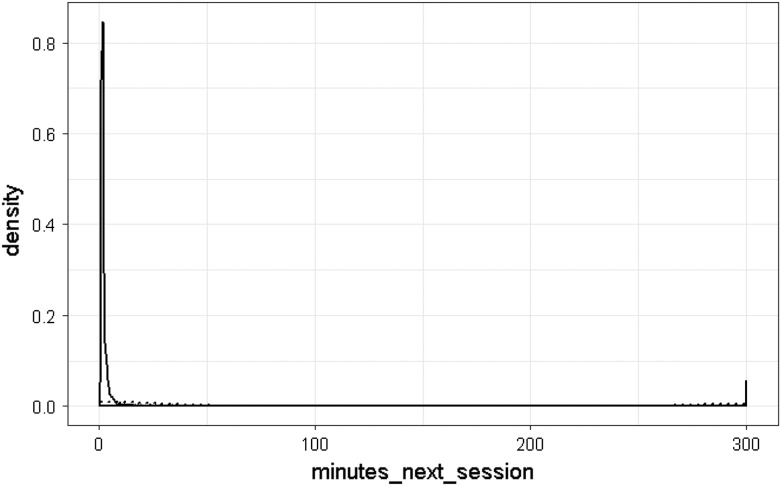

Table 2 reports the amount of money staked per session and session length duration for the succeeding session following the terminated and matched non-terminated sessions, respectively. Terminated sessions were followed by a session with a median amount staked of NOK 882. The matched non-terminated sessions were followed by a session with a median amount staked of NOK 780. The corresponding mean average values were NOK 1,543 and NOK 1,213. Terminated sessions were followed by a session with a median duration of 21 min. Matched non-terminated sessions were followed by a session with a median length duration of 17 min. The corresponding mean average values were 27 and 23 min. The median play break until the next session lasted 1.4 min for terminated sessions and 7.1 min for matched non-terminated sessions. The corresponding mean average values were 11.5 and 116.1 min. All sessions’ play breaks (terminated as well as matched non-terminated), which lasted longer than 300 min, were replaced with a value of 300. This outlier replacement was performed because sessions could be followed by a break, which lasted for a few days, weeks, or even months.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the next gambling session following the terminated gambling sessions and matched non-terminated sessions

| P25 | Median | Mean | P75 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of money staked (NOK) | Terminated | 353 | 882 | 1,543 | 1,937 |

| Matched | 300 | 780 | 1,213 | 1,560 | |

| Session length duration (min) | Terminated | 9 | 21 | 27 | 45 |

| Matched | 7 | 17 | 23 | 35 | |

| Length of play break (min) | Terminated | 1.1 | 1.4 | 11.5 | 2.3 |

| Matched | 0.8 | 7.1 | 116.0 | >300 |

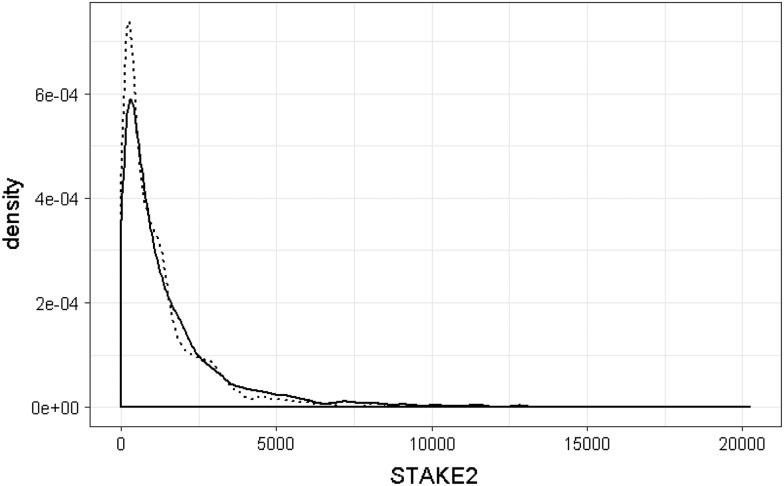

There was a significant difference between the terminated sessions and the matched non-terminated sessions with respect to the next sessions’ amount of money staked (V = 52,74,800, p < .001). Figure 4 displays the distribution of the next session’s stake for terminated and non-terminated sessions. There was a significant difference between the terminated sessions and the matched non-terminated sessions with respect to the next sessions’ duration length in minutes (V = 53,45,300, p < .001). Figure 5 displays the distribution of the next session’s duration in minutes for terminated and non-terminated sessions. There was a significant difference between the terminated sessions and the matched non-terminated sessions with respect to the play break length in minutes until the next session started (V = 18,07,200, p < .001). Figure 6 displays the distribution of the play break in minutes for the terminated and matched non-terminated sessions.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the amount of money staked during the next session for terminated (solid) and matched non-terminated sessions (dotted)

Figure 5.

Distribution of the next session duration for terminated (solid) and matched non-terminated sessions (dotted)

Figure 6.

Distribution of the play break duration until the next session (in minutes) for terminated (solid) and matched non-terminated sessions (dotted)

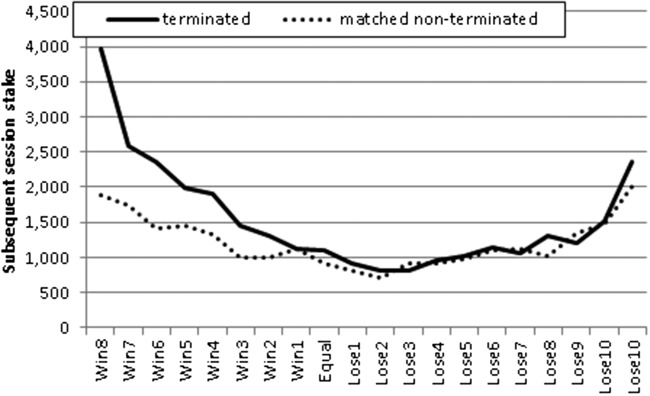

Another question raised during data exploration was whether the intensity of the next session depended on the previous sessions’ winning experience. On the x-axis, Figure 7 indicates whether a session paid out more than a player had staked (left side) or paid out less than a player had staked (right side). The different categories each contain an equal number of sessions. “Equal” indicates sessions in which the payout was equal to the amount staked. For both terminated sessions and matched non-terminated sessions, there is a non-linear relationship. Sessions where players lose a lot of money and sessions where players win a lot of money tend to be followed by sessions with higher stakes. However, terminated sessions in which players win much more than they staked (left side) tend to be followed by sessions with higher stakes. This happens to a much lesser extent for matched non-terminated sessions. This means if players have a winning experience they are willing to stake more if their session is terminated compared to players whose sessions are not terminated.

Figure 7.

Average stake of the next session depending on whether players won more than they staked (left) or won less than they staked (right). Equal indicates sessions where players won as much money as they staked

Another metric examined was the amount of money staked during the 24 hr after the terminated sessions and the corresponding matched non-terminated sessions. The median amount of money staked during the 24 hr after the terminated sessions was NOK 3,023 and the mean amount staked was NOK 4,972. The corresponding values for the matched non-terminated sessions were NOK 1,842 and NOK 3,519. A Wilcoxon matched-pairs test showed a significant difference with terminated session gamblers spending significantly more money than non-terminated session gamblers (V = 5,808,000, p < .001).

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of a forced VLT session termination after 60 min followed by a 90-s mandatory play break on subsequent gambling behavior. Players who play on Belago VLTs at Norsk Tipping are subject to a number of restrictions such as a daily maximum loss limit of NOK 900 and a monthly maximum loss limit of NOK 4,400 in this particular game category. Furthermore, Norsk Tipping’s players cannot lose more than NOK 20,000 across all games in a month. One aspect that sets Norsk Tipping apart from most other gambling operators is identified playing across all games and channels. The VLT forced session termination after 60 min is another RG tool employed by Norsk Tipping.

Unlike laboratory settings, the present authors were unable to conduct a controlled experiment as all sessions were potentially subject to a forced termination. For that reason, the study utilized a matched-pairs design during which terminated sessions were matched with similar non-terminated sessions. The matched non-terminated sessions were not significantly different with respect to amount of money staked or amount of money won. However, they were slightly different with respect to the session duration. This was to be expected, because sessions are terminated after approximately 60 min. Due to the nature of the long sessions, this study’s players are most likely to have been high-intensity gamblers, which means that findings do not necessarily apply to the whole spectrum of players. This study’s goal was to investigate whether this forced termination and mandatory play break led to higher or lower subsequent money being staked and/or to a shorter or longer play break. There was a significant effect of the forced termination regarding the amount of money staked in the next gambling session as well as the duration length of the next gambling session. Terminated sessions were followed by sessions with higher stakes and longer playing durations. These sessions also had a significantly shorter play break compared to matched non-terminated sessions. This means that a player whose sessions were terminated and subject to a 90-second mandatory play break started to gamble again earlier compared to a player who stopped the sessions voluntarily. The amount of money staked over the next 24 hr was also significantly higher for terminated sessions compared to matched non-terminated sessions. The most likely explanation for this finding is that those gamblers experiencing forced terminations are “heavier” gamblers in general and more likely to stake more money than those gamblers whose sessions are never terminated. This is due to the selection bias of the underlying study because all sessions that last 60 min are subject to a mandatory play break, whereas the matched sessions last slightly less than 60 min. For this reason, the results have to be interpreted with caution because only an experimental approach could truly confirm or disconfirm the findings in this study.

The only previous study that studied the effects of forced play breaks with varying length was the laboratory study conducted by Blaszczynski et al. (2015) outlined in the “Introduction” section. Blaszczynski and colleagues’ study concluded that self-reported craving was higher after an 8-min play break compared to a 3-min play break or no play break. However, the playing duration before the play break was only 15 min, which is only one-quarter of the 60-min duration in this study.

Both the studies by Auer and colleagues (Auer et al., 2014; Auer & Griffiths, 2015) investigated whether gambling operator-instigated pop-ups were effective in persuading gamblers to take a break from gambling after the playing of 1,000 consecutive slot games on an online gambling website. Both these studies demonstrated that very few gamblers ceased their play on seeing the pop-up message while playing in-session (0.67%–1.39%). The time spent continuously gambling (i.e., 60 min continuously) could be a barrier for players to stop voluntarily because such gamblers might be in an increased state of dissociation due to the longer playing session. Gamblers often report dissociation from reality and absorption in the gambling task (Griffiths et al., 2006; Monaghan, 2009). This lack of self-awareness can lead to chasing losses and spending more money than the gamblers can afford (Harris & Parke, 2016).

Another finding is related to players’ behavior following the winning of money. It appears that players who experience a winning session in which they have won more than they staked reacted differently if the session was terminated. The termination led to gambling with higher stakes during the next session compared to sessions that ended voluntarily. Winning sessions that end voluntarily are followed by sessions where players gamble with lower stakes.

This study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The major limitation was that this study was conducted with VLT players from just one gambling operator. This limitation somewhat limits the external validity as well as the reliability of the results in terms of generalizability to other VLT operators. Another major limitation was the lack of an experimental approach, which does not allow for any conclusions regarding cause and effect. To investigate the effect of the mandatory play break, the authors chose a matched-pairs design similar to that of Auer and Griffiths (2015; Auer et al., 2018). However, not all sessions were subject to a forced termination and a mandatory play break could be matched with non-terminated sessions. Terminated sessions that could be matched with non-terminated sessions had significantly higher stakes. The findings in this study are therefore only applicable to the sessions that could be matched. It could also be that players who experience frequent forced terminations gamble in a different way compared to players who do not experience such events. Some players actively play little bit less than 60 min trying to avoid an enforced termination. It is very likely that high-intensity players were not part of the final matched-pairs sample somewhat limiting the conclusions that can be made. The only way to overcome this limitation would be to use an experimental approach in which randomly selected players were subject to mandatory play breaks and others were not. Moreover, it cannot be ruled out that forced terminations would affect players differently if they were presented in a different way or if the pop-up conveyed a different message or was designed differently. Auer and Griffiths (2015) showed that references to RG tools and normative feedback increased the number of online players who voluntarily stopped their play after seeing a pop-up message. Future studies should preferably implement an experimental set-up in a real-world gambling environment with different lengths of session before they are forcibly terminated (e.g., after 30 or 45 min or longer than 60 min) and different lengths of play breaks (e.g., 5 min or much longer breaks such as 15 or 30 min).

To the authors’ knowledge, forced session terminations and mandatory play breaks are frequently used by online gambling operators as well as land-based operators who use player card technology (such as those based in Sweden and Norway). Many accreditation organizations (such as GamCare in the UK) require gambling operators to introduce these RG tools to receive a certification. However, there are very few laboratory and real-world research studies that have investigated the efficacy of these tools (Harris & Griffiths, 2017). Given the fact that these tools could potentially create more intense gambling based on the findings of this study, in the case of forced gambling session termination and the length of the mandatory play break following session termination, it is evident that further testing to determine the optimal session length and optimal length of play break to facilitate RG are required.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: This research was funded by Norsk Tipping, the Norwegian Government’s national lottery operator.

Authors’ contribution

All authors contributed to the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

MA was subcontracted by Nottingham Trent University. MDG’s university received funding from Norsk Tipping (the gambling operator owned by the Norwegian Government) for this work and also has received funding for a number of research projects in the area of gambling education for young people, social responsibility in gambling, and gambling treatment from Gamble Aware (formerly the Responsibility in Gambling Trust), a charitable body that funds its research program based on donations from the gambling industry. MA and MDG undertake consultancy for various gaming companies in the area of social responsibility in gambling.

References

- Auer M., Griffiths M. D. (2015). Testing normative and self-appraisal feedback in an online slot-machine pop-up message in a real-world setting. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 339. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer M., Hopfgartner N., Griffiths M. D. (2018). The effect of loss-limit reminders on gambling behavior: A real world study of Norwegian gamblers. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 1056–1067. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer M., Malischnig D., Griffiths M. D. (2014). Is ‘pop-up’ messaging in online slot machine gambling effective as a responsible gambling strategy? An empirical re-search note. Journal of Gambling Issues, 29(29), 1–10. doi: 10.4309/jgi.2014.29.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczynski A., Cowley E., Anthony C., Hinsley K. (2015). Breaks in play: Do they achieve intended aims? Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(2), 789–800. doi: 10.1007/s10899-015-9565-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D. (2012). Internet gambling, player protection and social responsibility In Williams R., Wood R., Parke J. (Eds.), Routledge handbook of Internet gambling (pp. 227–249). London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D., Wood R. T. A., Parke J., Parke A. (2006). Dissociative states in problem gambling In Allcock C. (Ed.), Current issues related to dissociation (pp. 27–37). Melbourne, Australia: Australian Gaming Council. [Google Scholar]

- Harris A., Griffiths M. D. (2017). A critical review of the harm-minimisation tools available for electronic gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(1), 187–221. doi: 10.1007/s10899-016-9624-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A., Parke A. (2016). The interaction of gambling outcome and gambling harm-minimisation strategies for electronic gambling: The efficacy of computer generated self-appraisal messaging. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14(4), 597–617. doi: 10.1007/s11469-015-9581-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs D. (1988). Evidence for a common dissociative-like reaction among addicts. Journal of Gambling Behavior, 4(1), 27–37. doi: 10.1007/BF01043526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landon J., Palmer du Preez K., Bellringer M., Page A., Abbott M. (2016). Pop-up messages on electronic gaming machines in New Zealand: Experiences and views of gamblers and venue staff. International Gambling Studies, 16(1), 49–66. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2015.1093535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen K., Larouche R., Buliung R. N., Faulkner G. E. (2018). A matched pairs approach to assessing parental perceptions and preferences for mode of travel to school. Journal of Transport & Health, 11, 56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2018.09.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McConaghy N. (1980). Behavioral completion mechanisms rather than primary drive maintain behavioural patterns. Activitas Nervosa Superior (Praha), 22, 138–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan S. (2009). Responsible gambling strategies for Internet gambling: The theoretical and empirical base of using pop-up messages to encourage self-awareness. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(1), 202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2008.08.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quanbeck A., Brown R. T., Zgierska A. E., Jacobson N., Robinson J. M., Johnson R. A., Deyo B. M., Madden L., Tuan W. J., Alagoz E. (2016). A randomized matched-pairs study of feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of systems consultation: A novel implementation strategy for adopting clinical guidelines for opioid prescribing in primary care. Implementation Science, 13(1), 21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0713-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood R. T. A., Griffiths M. D. (2007). A qualitative investigation of problem gambling as an escape-based coping strategy. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 80(1), 107–125. doi: 10.1348/147608306X107881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young M. M., Wohl M. J. A. (2009). The Gambling Craving Scale: Psychometric validation and behavioural outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(3), 512–522. doi: 10.1037/a0015043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]