Abstract

Patient-derived organoids (PDO) and patient-derived xenografts (PDX) continue to emerge as important preclinical platforms for investigations into the molecular landscape of cancer. While the advantages and disadvantage of these models have been described in detail, this review focuses in particular on the bioinformatics and state-of-the art techniques that accompany preclinical model development. We discuss the strength and limitations of currently used technologies, particularly ‘omics profiling and bioinformatics analyses, in addressing the ‘efficacy’ of preclinical models, both for tumour characterization as well as their use in identifying potential therapeutics. We select pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) as a case study to highlight the state of the art of the field, and address new avenues for improved bioinformatics characterization of preclinical models.

Keywords: Xenograft, Organoid, Disease model, Bioinformatics, Computational biology

1. Introduction

A growing number of preclinical models are on the rise as surrogate biological systems that promise to elucidate disease pathogenesis, and which are hypothesized to be effective for preclinical treatment testing. This encompasses a range of engineered cells and tissues of varying genomic complexity, spanning both in-vitro and in-vivo models. Over the past decade of cancer research, there has been an explosion of patient-derived tumour xenografts (PDX) and patient-derived organoids (PDO) for a variety of cancer types [1]. Development of these preclinical models in particular aims to serve multi-fold purposes: recapitulating genetic and phenotypic tumour heterogeneity, assessing cancer evolutionary dynamics, analyzing mechanisms of cancer progression, and identifying potentially viable therapeutics [1], [2]. PDX and PDO models for personalized drug testing are superseding use of human cancer cell lines for several key reasons. The artificial environment of human cancer cell lines produces homogenous populations that no longer genetically recapitulate the original tumour, and there have been significant differences observed in the gene expression profiles of tumours and matching cell lines [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. PDX models are developed by engrafting surgically resected tumour samples into immunocompromised mice, and can be propagated by serial passaging in mice [8], [9], [10]. Organoids are derived from stem cells (pluripotent stem cells or adult specific stem cells) that are grown in 3D in Matrigel alongside niche factors; these ex-vivo models mimic the in vivo architecture of the original tumour, and can be characterized using nucleic acid and proteomic methods [11], [12].

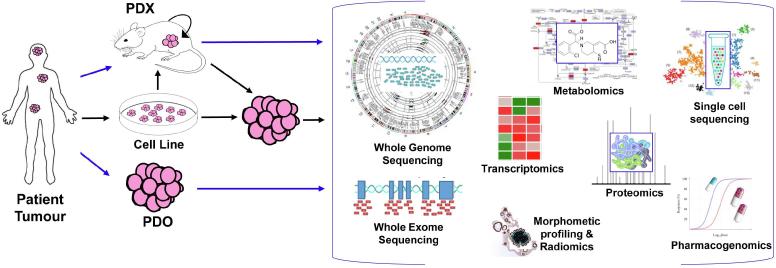

Interrogation of anti-cancer therapeutics using PDX and PDO models focuses on two main directions. The first is precision and personalized medicine. The underlying assumption here, is that the complexity of human tumours, and the ensuing range of pharmacological responses, vary substantially from patient to patient [2], [5], [8]. Patient-specific organoids for individualistic treatment of cystic fibrosis patients has been met with success [13], [14], [15], and has served both as a proof-of-concept and trigger for drug testing in organoids across multiple cancer types. PDO models have become a more preferable model to PDX, owing to shorter time frames and versatility to produce a spectrum of drug-sensitivity data [8], [16]. In addition to small-scale, personalized patient treatment, PDX and PDO models are being exploited for the purpose of grander preclinical decision making. In that context, the intention is to capture population diversity, and from it, identify clinically actionable genetic alterations [8], [17]. Population-based drug screens also provides insight into mechanisms of therapeutic resistance, as well as large-scale genotype-phenotype correlations [8]. A pertinent example of this approach is a recent population-based drug screen has been carried out on the ‘PDX Encyclopedia’, a compendium of >1000 PDX models across a range of solid cancers [8], [18]. In that screen, Gao et al. [18] used a 1 × 1 × 1 testing approach to assess population responses to 62 treatments across 6 indications, using PDX models that contain a diverse set of driver mutations. Through this analysis, they identified therapeutic candidates that had not been realized using in vitro models, and succeeded in using this large panel to validate previously proposed biomarkers of drug sensitivity [8], [18]. Whether for precision medicine or population-wide screening, the use of omics profiling, and the ensuing bioinformatics and computational biology analyses, have played a large role in the assessment of model fidelity (Fig. 1). For precision medicine, single- and multi-omics profiling is employed to assess whether molecular changes in the patient are also identified when transplanted to the disease model. For population-wide screens, these omics platforms are used to highlight the spectrum of genetic changes that can be identified across both the population and sub-populations (in some cases, tumour subtypes), when the tumours are grown into in vivo or ex vivo models.

Fig. 1.

The range of bioinformatics and computational biology analyses applied to assessing disease model fidelity. In the most direct approach (blue arrows), tumour cells from the patient are grown directly into a xenograft model (in-vivo), or as a 3D organoid (ex-vivo). Other intermediate steps (black arrows) towards growing PDX and PDO involve propagation of tumour cells in cell lines (in-vitro), followed by transfer to PDX to PDO prior to profiling. Patient tumours and resultant disease models are then assessed using various ‘omic profiling technologies that can then be analyzed to determine molecular and functional changes, including: mutation load (WGS, WES), copy number and structural variation changes (WGS, WES), gene expression for bulk tumour (transcriptomics and RNAseq) or across individual cells (single-cell RNAseq), protein expression changes (proteomics), response to therapy (pharmacogenomics), enrichment of biological pathways (metabolomics) and tumour histoarchitectural agreement (morphometric profiling and radiomics). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2. Bioinformatics approaches towards preclinical disease modelling

‘How well do PDX and PDO recapitulate the patient tumour?’ This remains a key question at the forefront of any analysis involving preclinical models, whether for the intended use of these models in tumour characterization, or for preclinical testing. Defining whether a given PDX or PDO model serves a representative tumour analog, or ‘patient avatar’, remains a rather complex question [16] that is largely dependent on the aspect of the tumour being modelled. A number of high-throughput ‘omics technologies and bioinformatics approaches (Fig. 1, Table 1) have been used to address the question from a number of angles. A large majority of publications (representative examples in Table 1) have focused on whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), RNA sequencing (RNAseq) and more recently, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA). We highlight some of these technologies below.

Table 1.

Overview of commonly used bioinformatics and high-throughput analytical approaches towards assessing the molecular landscape, as well as donor fidelity, of PDX and PDO models across different cancer types.

| Technology Used | Bioinformatics Analysis & Outcomes | Representative Examples and Organ type(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) |

|

[19], [20], [25] Gastric Pancreas Oral Cavity |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) |

|

[20], [21], [22], [23] Esophagus Breast Pancreas Oral Cavity |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA) |

|

[26], [27], [28], [29] Brain Colorectal Lung Breast |

| Proteomic profiling |

|

[30] Colorectal |

| Metabolomics |

|

[31], [32] Breast Intestine |

Whole-exome sequencing approaches have been largely used to address model fidelity by demonstrating that a patient and matching disease model share similar mutation profiles, particularly for mutations pertaining to well-recognized driver genes of the tumour. Exome profiling demonstrates that PDO models recapitulate subtype-specific mutational profiles of key driver genes and pathways that are observed in patient tissues of gastric cancer [19]. Variant conservation, distribution of variant allele frequencies, and overlap of mutational load between primary tumours and PDX have also been used as metric to demonstrate PDX model fidelity [20].

Whole-genome sequencing approaches provide a more encompassing picture of complex genomic events, including mutations, structural variations, and copy number changes. Similar to WES, WGS can shed deep insights into whether mutations are retained when tumours are transplanted into PDX and PDO. To this end, SNP-based sample clustering from WGS data has been used to assess the genetic distance between patient tissues and organoids across 33 breast cancer patients [21]. Distributions of mutations can also be analyzed to identify key mutational signatures in cancer; the expectation is there will be a concordance of signature types identified in matching tumour-model pairs [21]. Further characterization using WGS profiling focuses on more complex genomic events. Consistency of large-scale structural alterations and overall copy number profiles, compared to SNVs, has been observed in esophageal organoids [22]. WGS has also been used to demonstrate that chromothriptic events, which represent concerted, chromosomal structural rearrangements, are retained in esophageal and pancreatic organoids [22], [23]. Notably however, not all events are always concordant between donor-model pairs. Using the same technology, the authors also noted cases of discordance between tumour-donor pairs, including the addition or reduction of large-scale amplifications when tumours were transplanted to the PDX and PDO models [22], [23]. In addition to complex genomic events, whole genome sequencing has also been exploited to assess copy number changes, as well as investigate clonal structure and dynamics. It has been demonstrated in breast and hematopoietic cancers that copy number aberrations acquired through PDX passaging are substantially different from their parental tumours [24]. Accordingly, assessment of copy number aberrations, and agreement across multiple passages of PDX and PDO, sheds light on the genomic stability of these models and their association with drug therapy [20], [21], [22].

3. A bioinformatics case study: pancreatic cancer

Despite advancements in the use of PDX and PDO model to examine the molecular cancer landscape and to conduct preclinical testing, assessment of model fidelity for donor-model fidelity remains largely centered on qualitative, rather than quantitative, comparisons of genomic alterations. This poses a significant hurdle for translation of these models into the clinic, particularly for highly lethal and therapy-recalcitrant tumours [33], [34], [35], [5]. As a representative example, we focus on Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC), which has a relatively unchanged 5-year survival rate, and is notoriously considered to have the worst prognosis amongst solid tumours [36], [37].

WES profiling of PDAC cell lines and PDX models has been thoroughly conducted, across both primary and metastatic tumour [25], [38], [39]. Xie et al. [39] addressed somatic SNV characterization of paired primary tumours, metastasis, and matching PDX. In particular, the authors focused on allele frequency distributions and the agreement of functional mutations (driver genes and tumour suppressors) for matched data sets across three PDAC patients. Despite the limited patient and sample size of the study, the authors argue that their findings demonstrate that PDX models closely approximate PDAC genetics, particularly for advanced or end-stage disease [39]. Witkiewicz et al. [25], and Knudsen et al. [38] conducted a more detailed comparison of matched cell lines and PDX models that are derived from the same tumour, and demonstrated PDX utility in recapitulating patient-specific therapeutic sensitivities. Knudsen et al. [38] compared genetic events across 27 profiled PDAC patients, including primary tumour, matched PDX, and in some cases, cell lines derived from PDX. They indicated preservation of PDAC oncogenic driver mutations (ex: KRAS, TP53, SMAD4) and high allele frequencies in the cell lines, and conservation of >75% of nonsynonymous mutations across primary tumours and PDX [38]. In a similar vein, Wikiewicz et al. [25] conducted an interrogation into actionable genetic events that are retained in matched models, and a detailed investigation into therapeutic sensitivity of these models following drug treatment. Out of 28 cases, they identified a genetic event with sensitivity to a therapeutic strategy, and stressed upon the functional relevance of using patient-derived models to identify the significance of potentially actionable genetic events [25]. Collectively, these studies aimed to emphasize the fidelity of PDAC disease models at the genomic level based on mutational profiles. However, sole agreement of mutational profiles, and in particular for only a subset of driver genes, presents only a marginal characterization that is largely unreflective of the diverse molecular heterogeneity of the disease. Actionable driver mutations in PDAC remain to be identified; few patients with BRCA2 and KRAS mutations, for example, have been identified benefitting from targeted therapies [37], [40]. As such, much more comprehensive analyses need to be undergone, that are reflective of PDAC tumours and disease models at different levels of genomic complexity.

As a larger encompassing ‘omics platform, whole-genome sequencing has been used to assess the genomic complexity of resected PDAC tumours [37], [41], [42], [43], and has shed light on complex genomic events, such as catastrophic mitotic phenomena (chromothripsis) that occur with high frequency [43]. WGS profiling has only been addressed very recently for PDAC PDX and PDO models [23], [40], including work conducted by our laboratory [23]. To this end, WGS analysis is starting to play a role in assessing agreement of structural variation (SV) and copy number variation (CNV) across donor-model pairs in PDAC, with a focus on events which play a significant role in PDAC drug response and tumourigenesis [23], [40], [44], [45], [46]. Our laboratory in particular has conducted the first quantitative assessment of whole-genome comparisons between PDAC tissue and matched model systems; this presented a new opportunity for investigation of PDX and PDO fidelity at single-gene, chromosome- and genome-wide levels [23]. Our findings indicated that PDX and PDO demonstrate concordance of SV genomic events against patient tumours, particularly for chromosomes demonstrating chromothriptic behaviour [23]. Additionally, our assessment of a unique cohort of matched patient, PDX, and PDO ‘trios’ underscored that PDO models better recapitulate patients if grown using tumour tissue directly, rather than being grown from a PDX [23]. This is a pertinent observation, given increased findings that suggest PDO models are better able to reconstitute the PDAC tumour niche, compared to PDX and cell lines [47], [48], [49], [50].

In comparison to PDX, PDO models pose several advantages as PDAC tumour surrogates, given their increased ability to demonstrate ductal- and stage-specific characteristics, and that their 3-D architecture promotes interaction between pancreatic cells that better reflect the original tumour [47], [48], [50], [51]. Only recently, screening of large-scale PDAC organoid libraries has provided additional insight as to the efficacy of these models for widespread screening of therapeutics. Using a combination of whole-genome sequencing, transcriptomic profiling, and therapeutic profiling (‘pharmacotyping’), Tiriac et al. demonstrated that PDO models demonstrate heterogeneity in chemotherapy response, and identified transcriptional signatures that mirrored patient outcomes in two clinical cohorts [40]. Such findings present new avenues for further use of these models in population-wide therapeutic screens, and highlight the role of computational analyses in validating the efficacy of these models.

As of yet, clonal analysis using single-cell sequencing, or other approaches, has not been thoroughly addressed for organoid models [52]. Single-cell RNAseq conducted on PDAC primary tumours [53] has been used to identify subsets of cells with different proliferative features that may serve as biomarkers for antitumor immune response. Comprehensive assessment of clonal heterogeneity in disease models, as well as primary tumours, is expected to provide further insight into the underlying factors behind chemo-refractory disease in patients [52], and as well as heterogeneous responses to drug treatment [27].

4. Platforms for growth

Despite ongoing advancements, much remains to be done towards fully probing PDX and PDO at various molecular levels for several cancer types. One of the platforms that remains largely unaddressed is metabolomics (Fig. 1). Both NMR- and mass-spectrometry based metabolomics play a role in systems biology understanding of tumorigenesis, by 1) linking metabolic changes and regulatory mechanisms with transcriptomics and proteomics, and 2) highlighting how microenvironmental factors ultimately influence the cancer phenotype [54], [55], [56], [57]. Metabolic profiling of preclinical models has been addressed for a small number of cancer types including breast [31], [58], pancreas [59], and colorectal cancers [32], [60]. Nicolle et al. [59] incorporated metabolic profiles into a multi-omic clustering of PDAC xenografts; by harnessing information of metabolite transport and correlating it with transcriptomic profiles of pathway expression, they proposed pathways and molecular functions that could aid in the further characterization of PDAC subtypes (ex: distinguishing classical from basal subtypes). Similarly, integration of MS-based metabolomics and lipidomics of cell-enriched intestinal organoids [32], along with gene expression dynamics, highlighted several enzymatic activities and pathways that are reflective of different cell-enriched organoid populations. Such an integration of metabolomics and transcriptomics has also been harnessed to assess subtype-specific drug response to treatment in breast cancer PDX models [58]. These findings underscore how incorporation of metabolic profiles provides newer insights into disease model fidelity in a translational context, instead of remaining as of yet, a distal ‘omics platform.

Integration of metabolomics, along with other technologies, emphasizes the importance of multi-omic, as opposed to single-omic, characterization of PDX and PDO. Indeed, optical imaging of metabolic heterogeneity, across both tumours and disease models, is proposed to provide spatially and temporally comprehensive picture of tumour metabolism [61], and can be harnessed to predict therapeutic response of PDX and PDO [31]. Despite advancements, poor model characterization still affects development of anticancer treatments, and attributes to only a small percent of potential drugs passing FDA approval at the clinical stage [62], [63], [64]. Accordingly, to efficiently identify whether these models can be used as disease surrogates, the focus needs to shift from limited snapshots of donor-model comparisons, towards sufficient integration of data which embodies different molecular and functional states of the tumour.

5. Summary & outlook

PDX and PDO models continue to be utilized towards for the identification of both patient-specific patterns and population-wide trends that are characteristic of major cancer types. The main objective is to address whether such models can serve as disease model surrogates for patients, and to what molecular extent do they substitute for the original patient tumour. Bioinformatics approaches are in continuous demand to elucidate the molecular landscape of patient-derived xenografts and organoids, and to determine whether these models recapitulate genetic and phenotypic diversity of their parent tumours. There have already been great strides into ‘omics profiling of PDX and PDO, particularly using WGS, WES, and transcriptomics, and these technologies and ensuing computational analyses have shed deep insight into the nature of these preclinical models. However, there still remains a need for comprehensive bioinformatics analysis that is focused on multi-omic integration, and which provides quantitative, rather than qualitative, assessments of model fidelity. Additionally, there remains untapped potential behind some technologies, including proteomics and metabolomics, which has yet to be fully realized. Shifting the approach of how bioinformatics and computational analyses are used to conduct donor-model comparisons promises to provide greater insight on the ability of PDX and PDO models to serve as tractable and transplantable systems across various tumour types.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Bleijs M., van de Wetering M., Clevers H., Drost J. Xenograft and organoid model systems in cancer research. EMBO J. 2019;38(15) doi: 10.15252/embj.2019101654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-David U., Beroukhim R., Golub T.R. Genomic evolution of cancer models: perils and opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19(2):97–109. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0095-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Ruiter J.R., Wessels L.F.A., Jonkers J. Mouse models in the era of large human tumour sequencing studies. Open Biol. 2018;8(8) doi: 10.1098/rsob.180080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein W.D., Litman T., Fojo T., Bates S.E. A Serial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE) database analysis of chemosensitivity: comparing solid tumors with cell lines and comparing solid tumors from different tissue origins. Cancer Res. 2004;64(8):2805–2816. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weeber F., Ooft S.N., Dijkstra K.K., Voest E.E. Tumor organoids as a pre-clinical cancer model for drug discovery. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24(9):1092–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilding J.L., Bodmer W.F. Cancer cell lines for drug discovery and development. Cancer Res. 2014;74(9):2377–2384. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domcke S., Sinha R., Levine D.A., Sander C., Schultz N. Evaluating cell lines as tumour models by comparison of genomic profiles. Nat Commun. 2013;4(1):2126. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne A.T., Alferez D.G., Amant F., Annibali D., Arribas J., Biankin A.V. Interrogating open issues in cancer precision medicine with patient-derived xenografts. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(4):254–268. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tentler J.J., Tan A.C., Weekes C.D., Jimeno A., Leong S., Pitts T.M. Patient-derived tumour xenografts as models for oncology drug development. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(6):338–350. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sereti E., Karagianellou T., Kotsoni I., Magouliotis D., Kamposioras K., Ulukaya E. Patient Derived Xenografts (PDX) for personalized treatment of pancreatic cancer: emerging allies in the war on a devastating cancer? J Proteomics. 2018;188:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clevers H., Tuveson D.A. Organoid models for cancer research. Ann Rev Cancer Biol. 2019;3(1):223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dutta D., Heo I., Clevers H. Disease modeling in stem cell-derived 3D organoid systems. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23(5):393–410. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakradhar S. Put to the test: organoid-based testing becomes a clinical tool. Nat Med. 2017;23(7):796–799. doi: 10.1038/nm0717-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dekkers J.F., van der Ent C.K., Beekman J.M. Novel opportunities for CFTR-targeting drug development using organoids. Rare Dis. 2013;1(1) doi: 10.4161/rdis.27112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dekkers J.F., Wiegerinck C.L., de Jonge H.R., Bronsveld I., Janssens H.M., de Winter-de Groot K.M. A functional CFTR assay using primary cystic fibrosis intestinal organoids. Nat Med. 2013;19:939. doi: 10.1038/nm.3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aparicio S., Hidalgo M., Kung A.L. Examining the utility of patient-derived xenograft mouse models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(5):311–316. doi: 10.1038/nrc3944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Magnen C., Dutta A., Abate-Shen C. Optimizing mouse models for precision cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(3):187–196. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao H., Korn J.M., Ferretti S., Monahan J.E., Wang Y., Singh M. High-throughput screening using patient-derived tumor xenografts to predict clinical trial drug response. Nat Med. 2015;21:1318. doi: 10.1038/nm.3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan H.H.N., Siu H.C., Law S., Ho S.L., Yue S.S.K., Tsui W.Y. A comprehensive human gastric cancer Organoid Biobank captures tumor subtype heterogeneity and enables therapeutic screening. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23(6) doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.09.016. 882-97 e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell K.M., Lin T., Zolkind P., Barnell E.K., Skidmore Z.L., Winkler A.E. Oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma xenografts retain complex genotypes and intertumor molecular heterogeneity. Cell Rep. 2018;24(8):2167–2178. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sachs N., De Ligt J., Kopper O., Gogola E., Bounova G., Weeber F. A living biobank of breast cancer organoids captures disease heterogeneity. Cell. 2018;172(1–2) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.010. 373-86 e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X., Francies H.E., Secrier M., Perner J., Miremadi A., Galeano-Dalmau N. Organoid cultures recapitulate esophageal adenocarcinoma heterogeneity providing a model for clonality studies and precision therapeutics. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2983. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05190-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gendoo D.M.A., Denroche R.E., Zhang A., Radulovich N., Jang G.H., Lemire M. Whole genomes define concordance of matched primary, xenograft, and organoid models of pancreas cancer. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019;15(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ben-David U., Ha G., Tseng Y.-Y., Greenwald N.F., Oh C., Shih J. Patient-derived xenografts undergo mouse-specific tumor evolution. Nat Genet. 2017 doi: 10.1038/ng.3967. advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Witkiewicz Agnieszka K., Balaji U., Eslinger C., McMillan E., Conway W., Posner B. Integrated patient-derived models delineate individualized therapeutic vulnerabilities of pancreatic cancer. Cell Rep. 2016;16(7):2017–2031. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quadrato G., Nguyen T., Macosko E.Z., Sherwood J.L., Min Yang S., Berger D.R. Cell diversity and network dynamics in photosensitive human brain organoids. Nature. 2017;545(7652):48–53. doi: 10.1038/nature22047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roerink S.F., Sasaki N., Lee-Six H., Young M.D., Alexandrov L.B., Behjati S. Intra-tumour diversification in colorectal cancer at the single-cell level. Nature. 2018;556(7702):457–462. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim K.-T., Lee H.W., Lee H.-O., Kim S.C., Seo Y.J., Chung W. Single-cell mRNA sequencing identifies subclonal heterogeneity in anti-cancer drug responses of lung adenocarcinoma cells. Genome Biol. 2015;16(1):127. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0692-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eirew P., Steif A., Khattra J., Ha G., Yap D., Farahani H. Dynamics of genomic clones in breast cancer patient xenografts at single-cell resolution. Nature. 2015;518(7539):422–426. doi: 10.1038/nature13952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cristobal A., van den Toorn H.W.P., van de Wetering M., Clevers H., Heck A.J.R., Mohammed S. Personalized proteome profiles of healthy and tumor human colon organoids reveal both individual diversity and basic features of colorectal cancer. Cell Rep. 2017;18(1):263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh A.J., Cook R.S., Sanders M.E., Aurisicchio L., Ciliberto G., Arteaga C.L. Quantitative optical imaging of primary tumor organoid metabolism predicts drug response in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74(18):5184–5194. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindeboom R.G., van Voorthuijsen L., Oost K.C., Rodríguez-Colman M.J., Luna-Velez M.V., Furlan C. Integrative multi-omics analysis of intestinal organoid differentiation. Mol Syst Biol. 2018;14(6) doi: 10.15252/msb.20188227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bleijs M., van de Wetering M., Clevers H., Drost J. Xenograft and organoid model systems in cancer research. EMBO J. 2019;38(15):e101654-e. doi: 10.15252/embj.2019101654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Byrne A.T., Alférez D.G., Amant F., Annibali D., Arribas J., Biankin A.V. Interrogating open issues in cancer precision medicine with patient-derived xenografts. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:254. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muthuswamy S.K. Organoid models of cancer explode with possibilities. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22(3):290–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biankin A.V., Waddell N., Kassahn K.S., Gingras M.-C., Muthuswamy L.B., Johns A.L. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature. 2012;491(7424):399–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waddell N., Pajic M., Patch A.-M., Chang D.K., Kassahn K.S., Bailey P. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518(7540):495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knudsen E.S., Balaji U., Mannakee B., Vail P., Eslinger C., Moxom C. Pancreatic cancer cell lines as patient-derived avatars: genetic characterisation and functional utility. Gut. 2017 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie T., Musteanu M., Lopez-Casas P.P., Shields D.J., Olson P., Rejto P.A. Whole exome sequencing of rapid autopsy tumors and xenograft models reveals possible driver mutations underlying tumor progression. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tiriac H., Belleau P., Engle D.D., Plenker D., Deschenes A., Somerville T.D.D. Organoid profiling identifies common responders to chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discovery. 2018;8(9):1112–1129. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bailey P., Chang D.K., Nones K., Johns A.L., Patch A.-M., Gingras M.-C. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531(7592):47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collisson E.A., Sadanandam A., Olson P., Gibb W.J., Truitt M., Gu S. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat Med. 2011;17(4):500–503. doi: 10.1038/nm.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Notta F., Chan-Seng-Yue M., Lemire M., Li Y., Wilson G.W., Connor A.A. A renewed model of pancreatic cancer evolution based on genomic rearrangement patterns. Nature. 2016;538(7625):378–382. doi: 10.1038/nature19823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feuk L., Carson A.R., Scherer S.W. Structural variation in the human genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(2):85–97. doi: 10.1038/nrg1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pinto N., Dolan M.E. Clinically relevant genetic variations in drug metabolizing enzymes. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12(5):487–497. doi: 10.2174/138920011795495321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willyard C. Copy number variations' effect on drug response still overlooked. Nat Med. 2015;21(3):206. doi: 10.1038/nm0315-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boj Sylvia F., Hwang C.-I., Baker Lindsey A., Chio Iok In, Engle Dannielle D., Corbo V. Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2015;160(1-2):324–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greggio C., De Franceschi F., Figueiredo-Larsen M., Gobaa S., Ranga A., Semb H. Artificial three-dimensional niches deconstruct pancreas development in vitro. Development (Cambridge, England) 2013;140(21):4452–4462. doi: 10.1242/dev.096628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang L., Holtzinger A., Jagan I., BeGora M., Lohse I., Ngai N. Ductal pancreatic cancer modeling and drug screening using human pluripotent stem cell– and patient-derived tumor organoids. Nat Med. 2015;21:1364. doi: 10.1038/nm.3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krempley B.D., Yu K.H. Preclinical models of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Chin Clin Oncol. 2017;6(3):25. doi: 10.21037/cco.2017.06.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seino T., Kawasaki S., Shimokawa M., Tamagawa H., Toshimitsu K., Fujii M. Human pancreatic tumor organoids reveal loss of stem cell niche factor dependence during disease progression. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22(3) doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.12.009. 454-67.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tiriac H., Plenker D., Baker L.A., Tuveson D.A. Organoid models for translational pancreatic cancer research. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2019;54:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peng J., Sun B.-F., Chen C.-Y., Zhou J.-Y., Chen Y.-S., Chen H. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intra-tumoral heterogeneity and malignant progression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Res. 2019;29(9):725–738. doi: 10.1038/s41422-019-0195-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aboud O.A., Weiss R.H. New opportunities from the cancer metabolome. Clin Chem. 2013;59(1):138–146. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.184598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kang Y.P., Ward N.P., DeNicola G.M. Recent advances in cancer metabolism: a technological perspective. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50(4):31. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0027-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaushik A.K., DeBerardinis R.J. Applications of metabolomics to study cancer metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta, Rev Cancer. 2018;1870(1):2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muir A., Danai L.V., Vander Heiden M.G. Microenvironmental regulation of cancer cell metabolism: implications for experimental design and translational studies. Dis Models Mech. 2018;11(8):dmm035758. doi: 10.1242/dmm.035758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Borgan E., Lindholm E.M., Moestue S., Maelandsmo G.M., Lingjaerde O.C., Gribbestad I.S. Subtype-specific response to bevacizumab is reflected in the metabolome and transcriptome of breast cancer xenografts. Mol Oncol. 2013;7(1):130–142. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nicolle R., Blum Y., Marisa L., Loncle C., Gayet O., Moutardier V. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma therapeutic targets revealed by tumor-stroma cross-talk analyses in patient-derived xenografts. Cell Rep. 2017;21(9):2458–2470. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu M., Sanderson S.M., Zessin A., Ashcraft K.A., Jones L.W., Dewhirst M.W. Exercise inhibits tumor growth and central carbon metabolism in patient-derived xenograft models of colorectal cancer. Cancer Metabol. 2018;6(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s40170-018-0190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sengupta D., Pratx G. Imaging metabolic heterogeneity in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2016;15(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0481-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Begley C.G., Ellis L.M. Drug development: raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 2012;483(7391):531–533. doi: 10.1038/483531a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hutchinson L., Kirk R. High drug attrition rates–where are we going wrong? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(4):189–190. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kola I., Landis J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2004;3(8):711–715. doi: 10.1038/nrd1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]