Abstract

Aim

To examine the efficacy of transdiagnostic internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT), mindfulness-enhanced iCBT, and stand-alone online mindfulness training compared with a usual care control group (TAU) for clinical anxiety and depression.

Method

Individuals (N = 158) with a DSM-5 diagnosis of a depressive and/or anxiety disorder were randomised to one of the three clinician-guided online interventions, or TAU over a 14-week intervention period. The primary outcomes were self-reported depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) severity at post-treatment. Secondary outcomes included adherence rates, functional impairment (WHODAS-II), general distress (K−10), and diagnostic status at the 3-month follow-up (intervention groups).

Results

All three programs achieved significant and large reductions in symptoms of depression (g = 0.89–1.53), anxiety (g = 1.04–1.40), and distress (g = 1.25–1.76); and medium to large reductions in functional impairment (g = 0.53–0.98) from baseline to post-treatment and 3-month follow-up. Intention-to-treat linear mixed models showed that all three online programs were superior to usual care at reducing symptoms of depression (g = 0.89–1.18) and anxiety (g = 1.00–1.23).

Conclusion

Transdiagnostic iCBT, mindfulness-enhanced iCBT and online mindfulness training are more efficacious for treating depression and anxiety disorders than usual care, and represent an accessible treatment option for these disorders.

Keywords: Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), Mindfulness, E-health, Internet, Anxiety, Depression

Highlights

-

•

Recruited participants with DSM-5 anxiety disorders and/or depression

-

•

Compared internet CBT, mindfulness-enhanced CBT, and mindfulness training with TAU

-

•

Reductions in anxiety, depression, distress and functional impairment were observed.

-

•

All three clinician-guided online programs were more efficacious than usual care.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, considerable advances have been made in the development and evaluation of transdiagnostic internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) for anxiety disorders (Johnston et al., 2011; Nordgren et al., 2014), and comorbid anxiety and depression (Newby et al., 2013; Titov et al., 2011). Transdiagnostic iCBT interventions achieve comparable outcomes to disorder-specific iCBT programs (Dear et al., 2015; Newby et al., 2017; Titov et al., 2015), and have been found to have medium to large effect size superiority over control conditions for anxiety (Hedge's g = 0.78) and depressive (g = 0.84) symptoms (g = 0.78) (Newby et al., 2016). As a group, iCBT interventions have high treatment fidelity and reduce barriers to accessing face-to-face care, such as a shortage of trained clinicians, long waiting times, and out-of-pocket costs of attending treatment (Andrews et al., 2015b), making them convenient and accessible, scalable and cost-effective (Andrews et al., 2015a). However, a significant proportion of individuals do not adequately benefit from iCBT, with only 50% achieving full recovery following treatment (Sunderland et al., 2012) and a quarter of patients being classified as non-responders to iCBT (Rozental et al., 2019). It is therefore imperative that existing iCBT interventions are improved and alternative online interventions are developed and tested, to assist those who do not benefit from the available treatments, as well as thosewho are seeking alternative treatment options to iCBT.

One way to improve transdiagnostic iCBT is by incorporating additional strategies that better target the underlying mechanisms shared by anxiety and depressive disorders. For instance, evidence suggests that maladaptive emotion regulation, repetitive negative thinking, and experiential avoidance – processes known to have a functional role across anxiety and depressive disorders (Aldao and Nolen, 2010; Aldao et al., 2010; Chawla and Ostafin, 2007; Ehring and Watkins, 2008; Harvey et al., 2004) – appear to be resistant to treatment with standard CBT (Berking et al., 2008; Chambers et al., 2009; Hayes et al., 1996; Kingston et al., 2007; Roemer and Orsillo, 2002b; Roemer et al., 2013; Teper et al., 2013; Watkins et al., 2007). These processes are, however, known to be simultaneously targeted during mindfulness training and practice (Baer, 2003; Baer, 2007; Hofmann et al., 2010), and some (e.g., repetitive negative thinking) have been shown to mediate treatment gains following mindfulness-based interventions (Gu et al., 2016). In fact, preliminary evidence suggests that adding mindfulness components to standard CBT treatment appears to enhance treatment effects on these maladaptive coping processes (Berking et al., 2013). Taken together, these diverse lines of research support the notion that adding online mindfulness training into an existing iCBT protocol could help directly address these transdiagnostic processes in treatment, thereby potentially enhancing or broadening treatment effects.

Mindfulness is a skill of purposely paying attention to and observing the ongoing stream of external and internal stimuli, such as physical sensations, thoughts, and emotions, without judging or trying to control one's subjective experience (Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Marlatt and Kristeller, 1999). Developed through mindfulness meditation practice, which promotes the intentional self-regulation of attention (Kabat-Zinn, 1982), mindfulness practice has been shown to improve psychological well-being, adaptive functioning, and quality of life (Brown et al., 2007; Keng et al., 2011). Mindfulness has also been shown to improve a number of core mechanisms underlying anxiety and depressive disorders, such as emotion regulation, experiential avoidance, and ruminative thinking (Baer, 2003). In the context of psychopathology, mindfulness training encourages individuals to develop awareness of the fleeting nature of cognitive-emotional phenomena and to practice suspending maladaptive, habitual attempts to rid oneself of unwanted cognitions and emotions (Grabovac et al., 2011; Teasdale, 1999). This in turn can assist individuals to develop a less reactive and more compassionate relationship with their psychological difficulties (Segal et al., 2004), thereby reducing the distress associated with their symptoms. Evidence from the face-to-face treatment literature (Berking et al., 2013; Roemer and Orsillo, 2002a; Roemer et al., 2013) suggests that the experiential, emotion-regulation properties of mindfulness practice could complement the techniques of traditional CBT, thereby enhancing treatment outcomes by facilitating individuals' processing of their affective experiences (Hofmann and Asmundson, 2008; Lang, 2013). Delivering such mindfulness training via the internet has great capacity to increase access to mindfulness techniques, and disseminate treatment in an affordable and scalable way.

Internet-delivered mindfulness programs typically consist of audio tracks, video instructions, and written materials that teach the principles and practice of mindfulness (Spijkerman et al., 2016). To explore whether online mindfulness training could be effectively combined with transdiagnostic iCBT to improve treatment effects, we integrated mindfulness instruction and training within an existing iCBT program for depression and anxiety (Newby et al., 2013). This new Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT program consisted of the core strategies from our previously developed iCBT program (e.g., behavioural activation, cognitive restructuring), with the inclusion of mindfulness education, mindfulness exercises (e.g., mindfulness during daily activities), and guided mindfulness meditations to complement each of the core CBT skills. For instance, the concept of being mindful and engaged in everyday activities was taught alongside behavioural activation and activity scheduling. The skill of noticing and letting go of thoughts (e.g., during Mindfulness of the Breath and Body Scan) was taught alongside psychoeducation about the fight-or-flight response to reduce reactivity to bodily cues, and emphasised once more during cognitive restructuring to enhance the recognition of maladaptive interpretations and to facilitate disengagement from worry and rumination. Mindfulness and acceptance of unpleasant experiences was taught alongside graded exposure, including interoceptive and emotion exposures (see methods for further information). This new online program showed favourable results in a pilot trial with a predominantly comorbid (80%) clinical sample of 22 participants (Kladnitski et al., 2018), with large pre- to post-treatment reductions in anxiety (g = 1.39) and depression (g = 1.96) symptoms observed. Further, the popularity of the pilot trial and speed of recruitment suggested the acceptability of online mindfulness-based support and strategies among this population. However, despite these promising findings, a lack of control group prevented us from establishing whether mindfulness-enhanced iCBT was superior to usual care, as well as from assessing how it compares to the original iCBT program. The current RCT sought to address these gaps.

In this RCT, we also sought to test, for the first time, whether internet-delivered mindfulness training is safe and effective as a stand-alone treatment for clinical depression and anxiety. Compared with the evidence base for iCBT treatment of anxiety disorders (Olthuis et al., 2016) and depression (Andrews et al., 2010), research into internet-delivered mindfulness programs is in its infancy (Spijkerman et al., 2016). Despite recent evidence showing positive effects of guided and unguided online mindfulness programs on stress, general mental wellbeing (Spijkerman et al., 2016), and symptoms of anxiety and depression in non-clinical populations (Krusche et al., 2013), little is known about the acceptability, efficacy, and safety of internet-delivered mindfulness training as a stand-alone intervention for those with clinical anxiety and depressive disorders. Only one RCT to date has investigated the efficacy of internet-delivered mindfulness training for anxiety disorders in a clinical sample. Boettcher et al. (2014a) evaluated an 8-module audio-based online mindfulness program in a Swedish sample of individuals who met diagnostic criteria for a primary anxiety disorder (including social anxiety disorder, panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, GAD, or anxiety disorder not otherwise specified). Results showed large pre-to-post treatment effect sizes for anxiety (Cohen's d = 1.33) and depression (d = 1.58), which were maintained at 6-month follow-up, as well as moderate to large between-group effect sizes compared with an online discussion forum control condition for anxiety (g = 0.76) and depression (g = 0.49). While these findings are promising, they warrant replication and further testing in anxious and depressed samples. Given the popularity and wide-spread adoption of mindfulness-based interventions, evaluation of the clinical utility and safety of mindfulness training as stand-alone mental health intervention for clinically depressed and anxious individuals is timely and important (Creswell, 2017).

To answer this question, we extended the previous literature by developing a new stand-alone online mindfulness skills training program as a third comparison group. The aim of the present RCT was to evaluate the efficacy of these three internet interventions – an iCBT program, a Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT program, and stand-alone Mindfulness Training program – on symptoms of depression, anxiety, distress and functional impairment, compared to usual care. This study sought to replicate past research showing iCBT is superior to usual care control groups (Andrews et al., 2018), and sought to extend existing literature by establishing whether the mindfulness-enhanced iCBT and stand-alone internet-delivered mindfulness programs were superior to usual care in reducing depressive and anxiety symptom severity in clinical samples who met criteria for DSM-5 depressive and/or anxiety disorder diagnoses. We also administered diagnostic interviews and self-report assessments at 3-months follow-up, to explore whether the therapeutic gains we expected were maintained beyond the end of treatment, and to compare rates of symptom reduction and of diagnostic recovery across the three intervention groups. We hypothesised that all three online interventions would be superior to the usual care control group, and that the benefits of all three programs would be maintained at 3-months following treatment. Further, we also hypothesised that the Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT program would lead to the largest improvements in depression and anxiety symptom severity overall, relative to the iCBT and stand-alone internet mindfulness training groups. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine whether transdiagnostic internet-delivered mindfulness programs (alone, and in combination with iCBT) outperform usual care in a clinical sample of individuals meeting criteria for DSM-5 anxiety and/or depressive disorders. Further, it is the first study internationally to compare the acceptability, adherence, safety and efficacy of mindfulness-enhanced iCBT, iCBT and internet-delivered mindfulness training.

2. Method

2.1. Design

A CONSORT 2010 compliant (Schulz et al., 2010) parallel RCT compared the efficacy of three online programs (iCBT, Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT, internet-delivered Mindfulness Training [iMT]) to a treatment-as-usual control group (TAU). Treatment was delivered over a 14-week period. Allocation ratio was 1:1:1:1. Participants were assessed at pre-treatment, mid-treatment, and post-treatment, and at 3-month follow-up, except for the TAU group, who were offered the Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT Program after the post-treatment assessment. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of St Vincent's Hospital (Sydney, Australia) (HREC/14/SVH/170), and the trial was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12615000927527. All participants provided electronic informed consent to participate.

2.2. Power calculation and sample size

We initially based the power calculations on the findings from the pilot trial, and sought to power the trial to detect a d = 0.6 between the mindfulness-enhanced iCBT and iCBT program. We planned to recruit 50 participants per group, as 45/group were needed to detect a between groups effect size (Cohen's d) of 0.6 at 80% power, and alpha set at 0.05. Based on past research (Andrews et al., 2018), we also expected a large (d = 1.0 or higher) difference between the iCBT, mindfulness-enhanced iCBT group and the TAU control group. Thus a sample size of 17/group would be needed to detect superiority of the intervention groups over the TAU control group. Although we had no difficulties recruiting, we chose to discontinue recruitment once we recruited N = 160. The primary reasons for this were that the study was completed as part of NK's doctoral thesis, and it was not feasible to continue recruitment further due to time constraints associated with completing the trial within a PhD, and because the study was unfunded, so we did not have the resources to continue recruitment further.

2.3. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Participants were included if they were: (i) aged over 18 and an Australian resident, (ii) scored >9 on the GAD-7 and/or PHQ-9, and met DSM-5 criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), panic disorder (PD), agoraphobia (AG), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and/or major depressive disorder (MDD) according to an abbreviated diagnostic interview, the Anxiety and Related Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-5, administered via telephone (ADIS-5; Brown and Barlow, 2014), (iii) provided their name, phone number and address, and their general practitioner (GP's) details, (iv) had a phone, computer and printer, and (v) if they were taking medications were on a stable dose for at least two months. (vi) concurrent supportive counselling was not an explicit exclusion criteria. However, if they were receiving counselling, they must not have commenced treatment in the past two months. Exclusion criteria included the presence of psychosis or bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, drug or alcohol dependence, current suicidality, current use of antipsychotic or regular benzodiazepine medications, severe depression (PHQ-9 total score > 23), or completion of an online program for anxiety or depression in the past year.

2.4. Description of treatments and clinician guidance

All three online programs were delivered over 14 weeks via the Virtual Clinic website (www.virtualclinic.org.au). The programs consisted of six comic-style, story-based lessons, downloadable lesson summaries, reflective worksheets, and extra support materials including frequently asked questions and troubleshooting of common difficulties (see Table 1). Participants were contacted via e-mail and/or phone by a clinician (JN or NK) following Lessons 1 and 2 to encourage adherence, and then as needed throughout the program contingent on: patient request for contact, a rise in a participant's K-10 and/or PHQ-9 scores, indication of suicidal ideation on PHQ-9 question 9, or failure to log-in to complete a lesson in >10 days.

Table 1.

Lesson-by-lesson overview of the three online treatment programs.

| iCBT program |

MEiCBT program |

iMT program |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesson # and title | Lesson content | Lesson # and title | Lesson content | Lesson # and title | Lesson content |

| Lesson 1: About Depression and Anxiety |

|

Lesson 1: About Depression and Anxiety |

|

Lesson 1: About Mindfulness |

|

| Lesson 2: Identifying Thoughts and Tackling Low Activity |

|

Lesson 2: Tackling Physical Symptoms and Low Activity |

|

Lesson 2: Listening to Your Body |

|

| Lesson 3: Tackling Thoughts |

|

Lesson 3: Learning About Your Mind |

|

Lesson 3: Learning About Your Mind |

|

| Lesson 4: Tackling Avoidance |

|

Lesson 4: Tackling Negative Thoughts |

|

Lesson 4: Mindfulness Roadblocks |

|

| Lesson 5: Mastering Your Skills |

|

Lesson 5: Learning to Face Your Fears |

|

Lesson 5: Working With Difficulty |

|

| Lesson 6: Preventing Relapse and Getting Even Better |

|

Lesson 6: Staying Well |

|

Lesson 6: Mastering Your Skills |

|

| Extra resources | Extra resources | Extra resources | |||

| Good Sleep Guide; Medication Information; 100 Things To Do; About Assertiveness; About Panic Attacks; Boosting; Motivation; Conversation Skills; In Case of Emergency; Labelling Emotions; Worry Stories; Worry Time; Frequently Asked Questions | Good Sleep Guide; Medication Information; 100 Things To Do; About Assertiveness; About Panic Attacks; Boosting; Motivation; Conversation Skills; In Case of Emergency; Labelling Emotions; Worry Stories; Worry Time; Frequently Asked Questions; 50 Daily Activities to Do Mindfully Common Difficulties with Mindfulness |

50 Daily Activities to Do Mindfully; Common Difficulties with Mindfulness; Frequently Asked Questions; In Case of Emergency | |||

| Work-sheets | Work-sheets | Work-sheets | |||

| Activity Planning Monitor; Challenging Beliefs about Worry and Rumination; Exposure Planner; Exposure Stepladder Form; Facing Your Fears Worksheet; Positives Hunt Worksheet; Structured Problem Solving Worksheet; Thought Challenging Worksheet; Thought Monitoring Form | Activity Planning Monitor; Challenging Beliefs about Worry and Rumination; Exposure Planner; Exposure Stepladder Form; Facing Your Fears Worksheet; Positives Hunt Worksheet; Structured Problem Solving Worksheet Thought Challenging Worksheet; Thought Monitoring Form; Mindfulness Practice Diary |

Mindfulness Practice Diary | |||

2.4.1. The iCBT program

(See (Newby et al., 2013)) included psychoeducation about depression and anxiety, and the CBT cycle, as well as core CBT skills including behavioural activation, cognitive therapy (including thought monitoring and cognitive restructuring), strategies to manage rumination and worry, graded exposure, and relapse prevention.

2.4.2. The Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT program

(See (Kladnitski et al., 2018)) was a condensed and refined version of the 7-lesson Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT Program evaluated in the pilot study. It consisted of the iCBT components described above, combined with education about mindfulness principles, informal mindfulness exercises (e.g., mindfulness during daily activities) and a total of nine guided meditations adapted from Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) (Segal et al., 2012; Teasdale et al., 2013) and Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) (Kabat-Zinn, 2013) to complement the CBT skills taught. For instance, mindfulness of daily activities was taught alongside behavioural activation. The skill of noticing and letting go of thoughts (e.g., during Mindfulness of the Breath and Body Scan) was taught alongside psychoeducation about the fight-or-flight response to reduce reactivity to bodily cues, and throughout cognitive restructuring to facilitate the recognition of maladaptive thinking patterns and disengagement from worry and rumination. Mindfulness and acceptance of unpleasant experiences (e.g., Mindfulness of Physical Discomfort and Mindfulness of a Difficulty) was taught alongside graded exposure to facilitate emotion regulation and to reduce experiential and behavioural avoidance. Psychoeducation about the use of mindfulness practice in daily life was also incorporated into relapse prevention both to increase recognition of early warning signs, as well as to reduce reactivity to and catastrophic interpretations of symptom lapses.

2.4.3. The Mindfulness Training (iMT) program

Developed for this study, comprised of education about mindfulness, guidance on using mindfulness skills to manage symptoms, nine guided meditations (e.g., Mindfulness of Breath, Body Scan), guidance on using mindfulness skills in day-to-day life, and tips for overcoming common difficulties associated with practice.

2.4.4. The TAU group

Were advised to seek assistance from their general practitioner (GP) or access health services from their usual healthcare provider.

2.5. Procedure and study flow

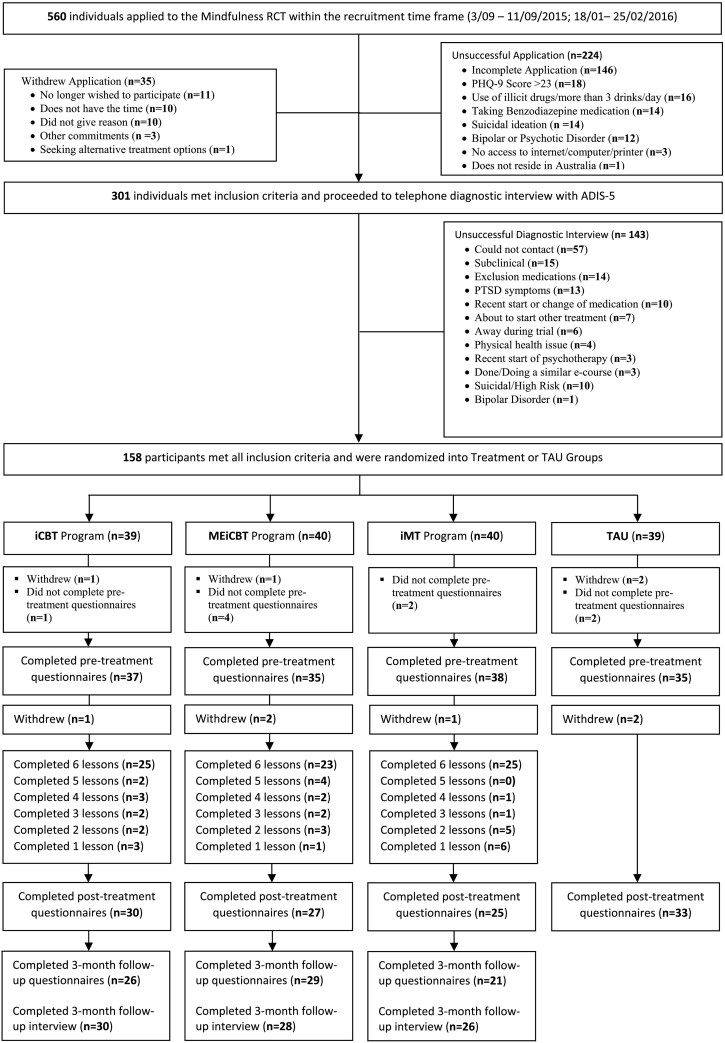

Fig. 1 presents the study flow chart. Recruitment took place from September 2015 to February 2016. The study was advertised on Facebook, and to a waiting list of individuals interested in taking part in online treatment research. Interested individuals applied online (N = 560 started an application) via the Virtual Clinic website before then taking part in a telephone administered risk assessment and ADIS-5 (n = 244), which was used to assess the presence of DSM-5 (APA, 2013) diagnoses of current GAD, PD, SAD, AG, OCD and/or MDD. Eligible participants (n = 158) were then randomised1 in an equal allocation ratio to either iCBT (n = 39), mindfulness-enhanced iCBT (n = 40), iMT (n = 40), or TAU (n = 39), and were administered self-report assessments at pre-, mid-, and post-treatment, and at 3-month follow-up (treatment groups only; the TAU was offered mindfulness-enhanced iCBT after post-treatment assessments). The Kessler-10 Psychological Distress scale (K-10; Kessler et al., 2002) was administered before each lesson, to alert clinicians to deterioration or severe scores (>30). The three treatment groups took part in a diagnostic interview to assess the presence of the same DSM-5 diagnoses at 3-month follow-up.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow chart.

Note. PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale; iCBT – internet-delivered Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, MEiCBT – Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT; iMT – internet-delivered Mindfulness Training; TAU – Treatment-as-Usual.

2.6. Measures

Socio-demographic information, current and past treatments, and previous experience with CBT and mindfulness was assessed at baseline. At application and prior to being randomised, we assessed participants' treatment preference by asking which of the three programs being evaluated in the study they would choose to do if they had were given a choice. To assess this, they were provided a choice based on the title of the program (i.e., the CBT Program, the Mindfulness and CBT Program, and the Mindfulness Program), and asked to choose one. The ADIS-5 (Brown and Barlow, 2014) was administered at baseline and 3-month follow-up (treatment groups only) to assess the presence and number of current diagnoses and comorbidities.2 Follow-up diagnostic interviews were conducted by MJ, an experienced Psychiatrist who was blind to the treatment group. The primary self-report outcomes were depression severity according to the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (α = 0.85)(PHQ-9, Kroenke et al., 2001) and anxiety severity according to the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item (α = 0.89) (GAD-7, Spitzer et al., 2006). Secondary outcomes included general psychological distress (K-10; Kessler et al., 2002), and functional impairment (The 12-item World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS-II) (α = 0.90).3

Following randomization and immediately prior to starting the first lesson, participants completed the Treatment Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ) (Devilly and Borkovec, 2000) using a 9-point scale (1 = not at all successful – 9 = very successful) to rate how logical the program they were about to begin seemed at that point (i.e., treatment credibility), and how successful they thought the program would be at reducing their symptoms of depression and/or anxiety (i.e., expectancy of benefit). Adherence and engagement was assessed using three indices: the number of participants who completed 100% of the lessons (i.e. 6/6), the number of participants who completed 75% of the lessons (at least 4/6), and the self-reported time spent reading lessons and completing between-lesson tasks (assessed lesson-by-lesson). Side-effects were measured at post-treatment by asking participants to describe any unwanted effects or negative events that they thought occurred because of the program. Free-text responses were coded by two independent researchers to categorise side effects into themes.

2.7. Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 24. Groups were compared at baseline using between-subjects analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and chi square analyses. Intention-to-treat (ITT) linear mixed models, with fixed factors of time, group, and time by group were conducted for each outcome measure, using maximum likelihood estimation (West et al., 2014),4 and unstructured covariance structure. Within-group effect sizes were calculated for pre-to-post (and pre to follow-up) changes on outcome measures, and between-group effect sizes (Hedge's g) were calculated at post and 3-month follow-up. Reliable change scores were calculated (RCI; Jacobson and Truax, 1991) between baseline and post-treatment, as well as between baseline and follow-up for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores,5 to determine rates of clinically reliable improvement and deterioration. A change of 4.96 points on the PHQ-9, and 5.82 points on the GAD-7 was considered statistically reliable change.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 2. Participants (n = 158) ranged between 19 and 71 years old (M = 39.2 years, SD = 12.14), with the majority being female (86.1%), born in Australia (82.9%), and in full-time (33.5%) or part-time (36.31%) paid employment. There were no significant differences between groups on any of the demographic or clinical measures, including GAD-7, PHQ-9, K-10 scores, diagnostic status, treatment expectancy ratings, or preference (ps >0.05).

Table 2.

Demographics and sample characteristics for the treatment groups and control group.

|

iCBT n = 39 |

MEiCBT n = 40 |

iMT n = 40 |

TAU n = 39 |

Statistic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) | Range | M(SD) | Range | M(SD) | Range | M(SD) | Range | ||

| Age (years) | 36.69(11.53) | 21–60 | 41.38(13.30) | 19–69 | 37.10(12.35) | 21–71 | 41.69(10.75) | 23–63 | F(3, 154) = 1.97, p = .12 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 6 | 15.4 | 4 | 10.0 | 6 | 15.0 | 6 | 15.4 | χ2 (3) = 0.69, p = .88 |

| Female | 33 | 84.6 | 36 | 90.0 | 34 | 85.0 | 33 | 84.6 | |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single/never married | 13 | 33.3 | 16 | 40 | 15 | 37.5 | 10 | 25.6 | χ2 (15) = 12.6, p = .63 |

| Married/de-facto | 19 | 48.7 | 17 | 42.5 | 21 | 52.5 | 20 | 51.3 | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 7 | 17.9 | 7 | 17.5 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 23.1 | |

| Educational status | |||||||||

| No qualification | 4 | 10.3 | 1 | 2.5 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 7.7 | χ2 (27) = 24.08, p = .63 |

| High school | 5 | 12.8 | 5 | 12.5 | 3 | 7.5 | 7 | 17.9 | |

| Tertiary (Undergraduate) | 18 | 46.2 | 23 | 57.5 | 21 | 52.5 | 18 | 46.2 | |

| Tertiary (Postgraduate) | 4 | 10.3 | 5 | 12.5 | 7 | 17.5 | 6 | 15.4 | |

| Technician, trade, or other certificate | 8 | 20.5 | 6 | 15 | 5 | 12.5 | 5 | 12.8 | |

| Employment status | |||||||||

| At home parent | 2 | 5.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.6 | χ2 (27) = 31.50, p = .25 |

| Full-time paid work | 13 | 33.3 | 13 | 32.5 | 14 | 35.0 | 17 | 43.6 | |

| Part-time paid work | 14 | 35.9 | 14 | 35.0 | 17 | 42.5 | 8 | 20.5 | |

| Unemployed | 3 | 7.7 | 7 | 17.5 | 3 | 7.5 | 7 | 18.0 | |

| Student | 7 | 17.9 | 3 | 7.5 | 4 | 10.0 | 3 | 7.7 | |

| Retired | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7.5 | 1 | 2.5 | 1 | 2.6 | |

| Disabled | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 | 1 | 2.6 | |

| Current medications | 15 | 38.5 | 16 | 40.0 | 18 | 45.0 | 15 | 38.5 | χ2 (3) = 0.48, p = .92 |

| Current medications (Type) | χ2 (9) = 6.80, p = .66 | ||||||||

| SSRI | 9 | 23.1 | 10 | 25 | 10 | 25 | 4 | 10.3 | |

| SNRI | 5 | 12.8 | 3 | 7.5 | 6 | 15 | 7 | 17.9 | |

| Other | 1 | 2.6 | 3 | 7.5 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 10.3 | |

| Current CBT treatment | 3 | 7.7 | 3 | 7.5 | 2 | 5.0 | 2 | 5.1 | χ2 (3) = 0.42, p = .93 |

| Previous experience with CBT | 16 | 41.0 | 12 | 30.0 | 9 | 22.5 | 15 | 38.5 | χ2 (3) = 3.82, p = .28 |

| Previous experience with mindfulness | 30 | 76.9 | 27 | 67.5 | 25 | 62.5 | 31 | 79.5 | χ2 (3) =3.69, p = .30 |

| M(SD) | Range | M(SD) | Range | M(SD) | Range | M(SD) | Range | ||

| Perceived credibility of treatment | 6.71 (1.86) | 1–9 | 7.29 (1.99) | 2–9 | 7.40 (1.62) | 5–9 | n/a | n/a | F(2, 108) = 1.53, p = .22 |

| Expectancy of benefit | 5.40 (1.64) | 1–9 | 5.89 (1.83) | 2–9 | 5.90 (1.54) | 2–9 | n/a | n/a | F(2, 108) = 1.11, p = .34 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Pre-treatment primary diagnosis | |||||||||

| MDD | 12 | 30.8 | 13 | 32.5 | 12 | 30.0 | 9 | 23.1 | χ2 (3) = 0.98, p = .81 |

| GAD | 12 | 30.8 | 11 | 27.5 | 17 | 42.5 | 19 | 48.7 | χ2 (3) = 4.99, p = .17 |

| SAD | 12 | 30.8 | 12 | 30.0 | 7 | 17.5 | 8 | 20.5 | χ2 (3) = 2.86, p = .41 |

| PD | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 2.5 | 3 | 7.5 | 1 | 2.6 | χ2 (3) = 2.01, p = .57 |

| AG | 1 | 2.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5.1 | χ2 (3) = 3.83, p = .28 |

| OCD | 1 | 2.6 | 3 | 7.5 | 1 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | χ2 (3) = 3.83, p = .28 |

Note. Except where noted, values refer to number and percentage scores. Educational Status = highest level of education received. iCBT = internet-delivered CBT; MEiCBT = Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT; iMT = internet-delivered Mindfulness Training; TAU = Treatment as Usual. M = mean, SD = standard deviation. SSRI = Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor; SNRI = Selective Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor; CBT = Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; GAD = Generalised Anxiety Disorder; SAD = Social Anxiety Disorder; PD = Panic Disorder; AG = Agoraphobia; OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

3.1.1. Diagnostic status at baseline

Participants met criteria for an average of 2.5 diagnoses (SD = 1.31, range = 1–6), and 70.8% presented with comorbid disorders: 15 (9.5%) participants met criteria for MDD only, 31 (19.6%) met criteria for a single anxiety disorder without MDD, 71 participants (44.9%) met criteria for both MDD and an anxiety disorder, and 41 (25.9%) met criteria for two or more anxiety disorders without MDD. Primary diagnoses (defined as the disorder most disabling/impairing for the individual) were most commonly GAD (n = 59, 37.3%), MDD (n = 46, 29.1%), or SAD (n = 39, 24.7%), followed by PD (n = 6, 3.8%), AG (n = 3, 1.9%) and OCD (n = 5, 3.2%). Sixty four participants (40.5%) were taking antidepressant medication and ten participants (6.3%) were undergoing counselling/psychotherapy. Only 32.9% of the participants reported receiving CBT in the past. In contrast, over two thirds (71.6%) had previous experience with mindfulness.

3.1.2. Treatment preference, perceived treatment credibility, and expectancy of benefit

The majority of participants (83% overall) indicated preference for the Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT program. As seen in Table 2, there were no significant differences in treatment preference between groups, with majority of participants in each group (84.6% in iCBT; 77.5% in MEiCBT; 85% in iMT; 84.6% in TAU) indicating they would have selected the Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT Program given the choice. There were also no significant differences between groups in expectancy of how logical and successful the treatment program participants were allocated to would be.

3.1.3. Adherence

Adherence to the first four lessons was 30/37 (81.1%) for the iCBT group, 29/35 (82.9%) for MEiCBT, and 25/38 (65.7%) for iMT, and although these rates appeared lower in the iMT group, they were not statistically significant (χ2 (2) = 2.09, p = .35). There were no group differences in completion rates (χ2 (2) = 0.397, p = .82), with 66.3% overall completion rates (iCBT: 25/37, 67.6%; Mindfulness-enhanced iCBT: 23/35, 65.7%; iMT: 25/38, 65.7%). Post-hoc analyses were conducted to compare completers versus non-completers on a range of variables: there were no significant differences in age, number of diagnoses, or baseline severity on the outcome measures (p's > 0.05).

3.2. Within-group effects

Table 3 presents results for primary and secondary outcomes, including effect sizes. All time by group interactions were significant at the p < .001 level (PHQ-9: F(3, 124.09) = 7.84; GAD-7: F(3, 128.16) = 9.81; K-10: F(3, 129.27) = 8.31; WHODAS-II: F(3, 126.59) = 7.70). Large effect sizes between baseline and post-treatment (gs = 1.04–1.49), and between baseline and follow-up (gs = 0.89–1.76) were observed for all three intervention groups on the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and K-10, with moderate to large effect sizes (gs = 0.53–0.98) observed in WHODAS-II scores. Changes in the TAU group were small and not significant.

Table 3.

Estimated marginal means and within-group effect sizes for main outcome measures.

| Measure | Group |

Pre |

Mid-treatment |

Post-treatment |

Follow-up |

Pre to post g |

Pre to follow-up g |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | g | (95% CI) | g | (95% CI) | ||

| K-10 | iCBT | 28.62 | 6.16 | 21.12 | 6.90 | 19.67 | 7.11 | 19.81 | 6.03 | 1.37 | 0.85–1.90 | 1.47 | 0.92–2.02 |

| MEiCBT | 27.89 | 6.16 | 19.99 | 6.90 | 18.09 | 6.94 | 17.56 | 6.18 | 1.35 | 0.80–1.90 | 1.57 | 1.00–2.13 | |

| iMT | 29.95 | 6.16 | 23.74 | 6.61 | 21.80 | 6.85 | 20.34 | 5.99 | 1.38 | 0.83–1.93 | 1.76 | 1.17–2.34 | |

| TAU | 28.14 | 6.16 | 26.50 | 7.16 | 26.58 | 7.17 | – | – | 0.21 | −0.27 - 0.70 | – | – | |

| PHQ-9 | iCBT | 13.28 | 4.50 | 9.06 | 4.67 | 7.51 | 5.00 | 7.66 | 5.79 | 1.08 | 0.58–1.59 | 0.89 | 0.37–1.40 |

| MEiCBT | 12.86 | 4.50 | 6.95 | 4.69 | 6.21 | 4.91 | 5.29 | 5.91 | 1.49 | 0.93–2.05 | 1.53 | 0.97–2.09 | |

| MP | 13.36 | 4.50 | 8.47 | 4.49 | 7.87 | 4.89 | 9.02 | 5.70 | 1.18 | 0.65–1.71 | 0.90 | 0.37–1.43 | |

| TAU | 12.74 | 4.50 | 11.54 | 4.84 | 12.04 | 5.04 | – | – | 0.16 | −0.32 - 0.64 | – | – | |

| GAD-7 | iCBT | 11.23 | 5.11 | 7.54 | 4.69 | 5.89 | 4.68 | 5.68 | 4.19 | 1.07 | 0.56–1.57 | 1.32 | 0.78–1.86 |

| MEiCBT | 10.69 | 5.11 | 6.34 | 4.73 | 5.15 | 4.61 | 4.24 | 4.32 | 1.04 | 0.51–1.57 | 1.40 | 0.85–1.95 | |

| iMT | 11.33 | 5.11 | 7.49 | 4.48 | 6.26 | 4.56 | 5.94 | 4.10 | 1.08 | 0.55–1.60 | 1.14 | 0.60–1.69 | |

| TAU | 12.51 | 5.11 | 10.71 | 4.90 | 10.98 | 4.75 | – | – | 0.34 | −0.14 - 0.82 | – | – | |

| WHODAS-II | iCBT | 25.74 | 7.70 | – | – | 21.14 | 7.15 | 20.33 | 6.34 | 0.77 | 0.27–1.26 | 0.85 | 0.33–1.37 |

| MEiCBT | 24.80 | 7.70 | – | – | 20.03 | 7.17 | 18.46 | 6.55 | 0.63 | 0.12–1.14 | 0.93 | 0.41–1.45 | |

| iMT | 26.18 | 7.70 | – | – | 21.41 | 6.97 | 19.79 | 6.09 | 0.53 | 0.02–1.04 | 0.98 | 0.42–1.55 | |

| TAU | 26.43 | 7.70 | – | – | 28.10 | 7.31 | – | – | −0.21 | −0.70 - 0.27 | – | – | |

Note. ES = effect size; M = mean, SD = standard deviation, CI = confidence interval, g = Hedge's g. K-10 = Kessler 10-item Psychological Distress Scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7 – Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale; WHODAS-II = The 12-item World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Schedule; iCBT = internet-delivered Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; MEiCBT = Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT; iMT = internet-delivered Mindfulness Training; TAU = Treatment-as-Usual.

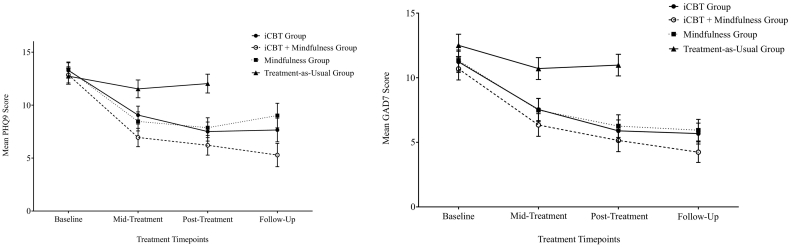

3.3. Between-group effects

A seen in Table 4, medium to large effect sizes were observed between each of the intervention groups and TAU at post-treatment on the PHQ-9 (gs = 0.89–1.18), GAD-7 (gs = 1.00–1.23), K-10 (gs = 0.67–1.19), and WHODAS-II (gs = 0.92–1.10). Fig. 2 presents PHQ-9 and GAD-7 results by group. There were small but non-significant effect sizes in favour of the MEiCBT program over both the iCBT and the iMT programs for all measures, and small effect sizes in favour of the iCBT program over the iMT program at post-treatment for K-10 scores (distress), although they did not reach statistical significance and should be interpreted with caution.

Table 4.

Mean differences and between-group effect sizes at post-treatment and follow-up.

| Measure |

Post-treatment between-group ES |

Follow-up between-group ES |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | g | (95% CI) | g | (95% CI) |

| K10 | ||||

| iCBT vs TAU | 0.96 | 0.43–1.48 | ||

| MEiCBT vs TAU | 1.19 | 0.64–1.74 | ||

| iMT vs TAU | 0.67 | 0.14–1.20 | ||

| MEiCBT vs iCBT | 0.22 | −0.29–0.73 | 0.36 | −0.17–0.89 |

| MEiCBT vs iMT | 0.53 | −0.01–1.07 | 0.45 | −0.09–0.99 |

| iCBT vs iMT | 0.30 | −0.22–0.83 | 0.09 | −0.46–0.63 |

| PHQ-9 | ||||

| iCBT vs TAU | 0.89 | 0.37–1.41 | ||

| MEiCBT vs TAU | 1.16 | 0.61–1.70 | ||

| iMT vs TAU | 1.18 | 0.63–1.74 | ||

| MEiCBT vs iCBT | 0.26 | −0.25–0.77 | 0.40 | −0.13–0.93 |

| MEiCBT vs iMT | 0.33 | −0.20–0.87 | 0.63 | −0.08–1.19 |

| iCBT vs iMT | 0.07 | −0.44–0.59 | 0.23 | −0.32–0.78 |

| GAD-7 | ||||

| iCBT vs TAU | 1.07 | 0.54–1.59 | ||

| MEiCBT vs TAU | 1.23 | 0.68–1.78 | ||

| iMT vs TAU | 1.00 | 0.46–1.54 | ||

| MEiCBT vs iCBT | 0.16 | −0.35–0.67 | 0.33 | −0.19–0.86 |

| MEiCBT vs iMT | 0.24 | −0.29–0.77 | 0.40 | −0.15–0.94 |

| iCBT vs iMT | 0.08 | −0.44–0.60 | 0.06 | −0.49–0.61 |

| WHODAS-II | ||||

| iCBT vs TAU | 0.95 | 0.42–1.48 | ||

| MEiCBT vs TAU | 1.10 | 0.55–1.65 | ||

| iMT vs TAU | 0.92 | 0.37–1.47 | ||

| MEiCBT vs iCBT | 0.15 | −0.36–0.67 | 0.29 | −0.25–0.82 |

| MEiCBT vs iMT | 0.19 | −0.34–0.73 | 0.21 | −0.36–0.77 |

| iCBT vs iMT | 0.04 | −0.49–0.56 | 0.09 | −0.49–0.66 |

Note. ES = effect size; M = mean, SD = standard deviation, CI = confidence interval, g = Hedge's g. K-10 = Kessler 10-item Psychological Distress Scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7 – Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale; WHODAS-II = The 12-item World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Schedule; iCBT = internet-delivered Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; MEiCBT = Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT; iMT = internet-delivered Mindfulness Training; TAU = Treatment-as-Usual.

Fig. 2.

Mean PHQ-9 (depression) and Mean GAD-7 (anxiety) scores across time-points.

3.4. Reliable change

3.4.1. PHQ-9-scores

Table 5 presents the reliable change results. Results are presented for the intention-to-treat sample, so that the percentage scores represent the proportion of the group that had baseline data. Between baseline and post-treatment there was a significant group difference in the proportion who experienced reliable change (χ2 (6) = 21.77, p ≤.001). One participant in each of the treatment groups and four participants in the TAU group showed clinically reliable deterioration in PHQ-9 scores between pre and post-treatment. Between baseline and follow-up, for the three treatment groups only, there was also a significant group difference (χ2 (4) = 10.57, p = .032). Deterioration in scores from baseline to follow-up was observed for four (16.7%) participants in the iMT group, but none of the iCBT or Mindfulness-enhanced iCBT groups.

Table 5.

Reliable change results.

|

iCBT |

MEiCBT |

iMT |

TAU |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre to post n(%) |

Pre to follow-up n(%) |

Pre to post n(%) |

Pre to follow-up n(%) |

Pre to post n(%) |

Pre to follow-up n(%) |

Pre to post n(%) |

Pre to follow-up n(%) | |

| n = 39 | n = 39 | n = 40 | n = 40 | n = 40 | n = 40 | n = 39 | ||

| PHQ-9 | ||||||||

| No reliable change | 9 (23.1) | 10 (25.6) | 10 (25.0) | 9 (22.5) | 10 (25.0) | 5 (12.5) | 23 (57.5) | n/a |

| Reliable improvement | 21 (53.8) | 17 (43.6) | 17 (42.5) | 20 (50.0) | 16 (40.0) | 15 (37.5) | 5 (12.8) | n/a |

| Reliable deterioration | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | 4 (10) | 4 (10.3) | n/a |

| Missing data | 9 (23.1) | 13 (33.3) | 12 (30.0) | 11 (27.5) | 13 (33.3) | 16 (40.0) | 7 (17.9) | n/a |

| GAD-7 | ||||||||

| No reliable change | 15 (38.5) | 13 (33.3) | 16 (40.0) | 12 (30.0) | 12 (30.0) | 10 (25.0) | 25 (64.1) | n/a |

| Reliable improvement | 16 (41.0) | 14 (35.9) | 12 (30.0) | 17 (42.5) | 14 (35.0) | 13 (32.5) | 5 (12.5) | n/a |

| Reliable deterioration | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.1) | n/a |

| Missing data | 9 (23.1) | 13 (33.3) | 12 (30.0) | 11 (27.5) | 13 (32.5) | 16 (40.0) | 7 (17.9) | n/a |

Note. PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7 – Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale; iCBT = internet-delivered Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; MEiCBT = Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT; iMT = internet-delivered Mindfulness Training; TAU = Treatment-as-Usual. Sample sizes based on intention-to-treat.

3.4.2. GAD-7 scores

One participant in the iMT and two in the TAU group demonstrated deterioration in GAD-7 scores between baseline and post-treatment; no iCBT or MEiCBT participants deteriorated. There was a significant group difference in reliable change, across groups (χ2 (6) = 13.81, p = .032). Between baseline and follow-up, in the three treatment groups, only one participant in the iMT group deteriorated. The group difference was not significant (χ2 (4) = 2.64, p = .62).

3.5. Diagnostic status (follow-up)

As seen in Table 6, groups did not differ significantly in the average number of diagnoses present at follow-up (F(2, 81) = 0.68, p = .51), nor the number of individuals who continued to meet the diagnostic criteria for MDD or anxiety disorders following treatment. Overall, of the participants who were interviewed at follow-up, 60% of the iCBT group, 60.7% in the Mindfulness-enhanced iCBT group, and 73.1% in the iMT group no longer met criteria for any disorder. However, given the attrition rates at follow-up, particularly in the iMT group, these results need to be interpreted with caution.

Table 6.

Average number of diagnoses and the proportion of participants meeting criteria for a diagnosis at baseline and follow-up across treatment groups.

|

iCBT group |

MEiCBT group |

iMT group |

Statistic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 39) |

Follow-up (n = 39) |

Baseline (n = 40) |

Follow-up (n = 40) |

Baseline (n = 40) |

Follow-up (n = 40) |

||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| Number of diagnoses | 2.56 (1.35) | 0.53 (0.78) | 2.45 (1.40) | 0.57 (0.84) | 2.25 (1.13) | 0.35 (0.63) | F(2, 81) = 0.68, p = .51 |

| Diagnosis (any) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | Statistic |

| MDD | 22 (56.4) | 3 (7.7) | 24 (60) | 1 (2.5) | 22 (55) | 2 (5.0) | χ2 (4) = 2.31, p = .68 |

| GAD | 28 (71.8) | 5 (12.8) | 25 (62.5) | 2 (5.0) | 27 (67.5) | 4 (10.0) | χ2 (4) = 2.70, p = .61 |

| SAD | 27 (69.2) | 6 (15.4) | 26 (65) | 10 (25.0) | 27 (67.5) | 3 (7.5) | χ2 (4) = 5.89, p = .21 |

| PD | 5 (12.8) | 1 (2.6) | 8 (20) | 1 (2.5 | 6 (15) | 0 (0) | χ2 (4) = 2.24, p = .69 |

| AG | 9 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 7 (17.5) | 1 (2.5) | 6 (15) | 0 (0) | χ2 (4) = 3.38, p = .50 |

| OCD | 8 (20.5) | 1 (2.6) | 8 (20) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | χ2 (4) = 2.24, p = .69 |

| Missing data | 0 (0) | 9 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 12 (30.0) | 0 | 14 (35.0) | |

Note. Except where noted, values refer to number and percentage scores. iCBT = Internet-Delivered CBT; MEiCBT = Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT; iMT = Internet-Delivered Mindfulness Training. M = mean, SD = standard deviation. MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; GAD = Generalised Anxiety Disorder; SAD = Social Anxiety Disorder; PD = Panic Disorder; AG = Agoraphobia; OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

3.6. Participant time spent

There was no significant difference between groups in self-reported time spent on working through the program content – ranging from 47 to 65 min per lesson in iCBT, 63–97 min per lesson in MEiCBT, and 43–48 min per lesson in iMT. There were no differences in the self-reported time spent practicing the skills taught – ranging from 69 to 118 min per lesson in iCBT, 90–125 min per lesson in MEiCBT, and 66–81 min per lesson in iMT.

3.7. Self-reported side effects attributed to the program

At post-treatment the majority of participants across the groups (iCBT: 78.6%; MEiCBT: 89.3%; iMT: 92%) did not report experiencing any side effects attributable to the programs. Independent coding of responses revealed two categories – (1) ‘side-effects’ - unwanted or unpleasant experiences that were directly caused by participants' completion of the programs, which were further coded into (a) increase in unpleasant emotions (e.g., anxiety, sadness) and (b) increase in unpleasant thoughts (e.g., worry); and (2) ‘other difficulties’, such as being busy and finding it hard to motivate self to complete the lessons, which were unrelated to the treatment program but had influenced participants' ability to adhere to treatment.

3.8. Clinician time

Clinicians recorded the number of minutes spent in the Virtual Clinic system, after each contact was made with a participant. Clinicians (NK and JN) spent on average just under an hour per participant in e-mail or phone contact with participants over the course of treatment, with the least clinician time recorded in the MEiCBT group (F(2, 116) = 3.07, p = .050) (iCBT: M(SD): 51.64 (32.08), range: 3–136; MEiCBT: M(SD): 37.58 (21.77), range: 3–104 min; iMT: M(SD): 57.37 (50.42), range 15–247 min).

3.9. Treatment satisfaction

The majority of the participants – 90% in iCBT, 100% in the MEiCBT, and 80.8% in the iMT – reported being ‘mostly’ or ‘very’ satisfied with the treatment program they received. One participant (3.3%) in the iCBT group reported feeling dissatisfied and five participants (19.2%) in the iMT group reported feeling neutral about the program.

4. Discussion

The present RCT was the first to compare outcomes of three transdiagnostic clinician-guided internet-delivered treatment programs –cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) (Newby et al., 2013), mindfulness-enhanced iCBT (Kladnitski et al., 2018) and internet-delivered mindfulness training for depression and anxiety, to a usual care control group (TAU). In a predominantly comorbid clinical sample (71% met criteria for two or more disorders), all three treatment groups demonstrated significant reductions in self-reported symptoms of depression (gs = 0.89–1.53), anxiety (gs = 1.04–1.40), distress (gs = 0.67–1.19), and functional impairment (gs = 0.53–0.98) from baseline to post-treatment, and were superior to the treatment as usual (TAU) control group at post-treatment on all outcome measures. Relative to TAU, large between-group differences in anxiety severity (gs = 1.00–1.23), depression (gs = 0.89–1.18), distress (gs = 1.35–1.76) and functional impairment (gs = 0.92–1.10) were observed. While attrition rates were considerable (23–35%), among those who completed blinded diagnostic interviews at the 3-month follow-up, over 60% of participants in each group no longer met criteria for any disorder.

Although lower than expected based on past studies of similar programs (Newby et al., 2013; Titov et al., 2015), adherence rates (66–68%) were comparable across programs. Further, reliable improvements observed in this sample on PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were in line with previous research (Newby et al., 2013). These outcomes were observed with, on average, less than an hour of clinician time per participant spent monitoring and providing guidance throughout the 14-week course of treatment. While some participants required a considerable amount of clinician time, primarily for the purposes of encouraging adherence and risk monitoring, majority of participants required considerably less clinician time than would have been spent providing equivalent dose of face-to-face treatment. Therefore, the range of clinician time spent per person did vary across participants as we sought to provide minimal, on-demand support according to patient preference and need. Further research is required with more standardised support time and levels across participants to replicate the current findings. However, our findings are consistent with recent research which has shown that ‘on-demand’ or optional clinician support achieves similarly large effects on depression and anxiety as weekly clinician support (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2017), although at the expense of lower completion rates.

The results of the present study are consistent with previous meta-analyses of iCBT showing iCBT to be superior to inactive controls including waitlist and usual care groups (Andrews et al., 2018; Newby et al., 2016). They also provide further evidence in support for the efficacy of transdiagnostic iCBT for mixed depressive and anxiety disorder diagnoses (Johnston et al., 2013; Johnston et al., 2011; Newby et al., 2013; Titov et al., 2015; Titov et al., 2011). In addition, the results extended our previous pilot evaluation of the Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT program (Kladnitski et al., 2018). The condensed 6-lesson Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT program appeared to have slightly higher adherence than in the pilot evaluation (66% versus 59% in the pilot study). While arguably the most interesting question of this study was whether the Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT program was superior to the other treatment groups, unfortunately the relatively small sample sizes meant that the study was underpowered to detect group differences. Although all three treatment groups were more effective than usual care across all outcome measures, there were no differences between the three treatment groups on depression, anxiety, distress or wellbeing outcomes. The between group effect sizes for the difference between the indfulness-nhanced iCBT group relative to the iCBT and mindfulness groups were only small and not statistically significant, and were much lower than what we expected based on the pilot trial results (which our power calculations were based on). Based on the results of this study, future randomised trials would need to include at least 200 participants per group to be adequately powered to detect any group differences among the treatment groups. A replication of these findings in a larger powered superiority trial is warranted and will allow for a detailed evaluation of outcome moderators and mediators of treatment effects across the intervention groups, including patient preferences, sample characteristics, and measures of the transdiagnostic processes (e.g., negative repetitive thinking, experiential avoidance, mindful awareness).6

The novel finding from this study was the superiority of the two new mindfulness-based online programs over the TAU control group. We do note however, the TAU group more closely mirrors a waiting list control group, as participants were allowed access to an online program at the end of the 14-week waiting period, and there was relatively minimal service use in this group. This study showed, for the first time internationally, that online training in mindfulness practice with minimal guidance from an instructor or clinician (alone or in combination with CBT) is an acceptable and efficacious transdiagnostic treatment option for individuals with clinical depression and anxiety. These results are consistent with meta-analyses showing the positive effects of transdiagnostic mindfulness-based interventions on anxiety and depression symptom severity (Newby et al., 2015). Unexpectedly, we found large differences between the iMT program compared with the control condition for anxiety (g = 1.00) and depression (g = 1.18), whereas Boettcher et al., 2014a found only medium differences between an internet-based mindfulness treatment for anxiety disorders on anxiety (g = 0.76) and depression (g = 0.49) symptom severity relative to discussion forum control. These findings add to the emerging body of literature which suggests that stand-alone mindfulness training could be a viable treatment option for individuals with depression and anxiety, however, replication of these findings is imperative.

Delivering mindfulness training online, without the in-person guidance and support of an experienced mindfulness practitioner, is an emerging field. It was therefore important to test not only the efficacy but also the safety of such a program in a clinical sample. We excluded participants with PTSD and severe depression (PHQ-9 scores >23). While only one participant in the iMT group showed clinically reliable deterioration on depression and anxiety scores between pre- and post-treatment, four participants (16.7%) demonstrated clinically reliable deterioration in symptoms of depression between pre-treatment and 3-month follow-up. This suggests that gains following the online mindfulness program may not be maintained by all participants, and is consistent with findings from Boettcher et al. (2014a) who also observed a significant increase in symptoms of depression between post-treatment and 6-month follow-up in some participants. These results are inconsistent with the body of literature showing the relapse-prevention properties of mindfulness training as part of MBCT for those in remission from depression (Piet and Hougaard, 2011). They suggest that although mindfulness training on its own may have beneficial effects on acute symptoms, gains may not be maintained beyond completion of treatment for a small proportion of individuals, who may require additional intervention. Furthermore, although overall rates of completion were similar across groups, almost 20% of participants in the iMT group dropped out during the first four lessons, whereas participants in the iCBT and mindfulness-enhanced iCBT groups did not do so. While the positive effects of iMT were observed overall across the group, these may have only been driven by a subset of participants who remained in treatment. It is not clear whether treatment benefit is achieved in fewer sessions (e.g., as a result of learning about the principles of mindfulness), or whether drop-out early in the iMT program was due to disengagement, deterioration, or challenges maintaining active and regular mindfulness practice as recommended by the program.

Assessing side-effects in online psychological interventions is a relatively novel area, with only a handful of studies assessing their nature and frequency (Boettcher et al., 2014b; Rozental et al., 2014; Rozental et al., 2015; Rozental et al., 2017). In the present study, 7–18% reported experiencing unwanted effects as a result of completing the program, with the highest proportion being in the iCBT group. These were mainly an increase in negative thoughts (e.g., worry) and feelings (e.g., sadness, anxiety, guilt) as a result of reading about and reflecting on the nature and impact of their symptoms, and when confronting difficulties. While it is not uncommon to experience worsening of symptoms in the early stages of psychotherapy (Foulkes, 2010), further research is needed to systematically assess participants' experiences of side effects and how they influence engagement and drop-out, as well as to identify methods to mitigate them.

Adherence presented a challenge, with fewer than anticipated completing all of the lessons across the programs, and those in the iMT dropping out much sooner. Interestingly, participants' ratings of expected benefit from treatment were moderate for all three of the programs, with some participants expecting to derive no benefit to their symptoms. It may be the case that although adherence is a better predictor of outcome than treatment expectancy (LeBeau et al., 2013), treatment expectancy is likely to moderate adherence. In addition, participants' ratings of perceived treatment credibility at baseline were highest for the iMT program (although group differences were not significant), which suggests that individuals perceived mindfulness to be a logical intervention for their difficulties. This could be partly explained by the popularity of mindfulness in the lay context of mental health, which could contribute to a ‘halo’ effect of these interventions at present similar to the ‘halo’ of CBT when it first gained popularity (Friborg and Johnsen, 2017; Johnsen and Friborg, 2015), or this could be explained by the low awareness of what ‘CBT’ is in the general public, which has direct implications for individuals seeking psychological treatment for their difficulties. In addition, these higher ratings of credibility could explain the overwhelming pre-treatment preference for the combined MEiCBT program (82.9%). Although this could be interpreted as participants preferring the ‘best of both worlds’ treatment, still more people – 21 out of 158 (13.3%) preferred the pure mindfulness program, with only six out of 158 individuals (3.8%) indicating they would select pure iCBT if given a choice. This disproportional preference for and perceived credibility of mindfulness over CBT is particularly interesting given that only 32.9% of individuals in this highly comorbid clinical sample reported previously receiving CBT, while over 70% reported some kind of previous experience with mindfulness (e.g., self-help books, meditation classes or groups, retreats).

Such findings can be tentatively interpreted to suggest that, although individuals who report struggling with persistent, clinically significant, and comorbid symptoms of anxiety and depression are actively seeking relief, they may be favouring ‘well-being’ interventions, which is what the concept of ‘mindfulness’ currently represents, rather than more traditional ‘treatment’. Typically, only 39% of individuals with a diagnosable emotional disorder seek professional mental health help (Harris et al., 2015), so future studies could ascertain whether the addition of well-being components like mindfulness into treatment interventions could increase the proportion seeking and accessing treatment.

Overall, the findings of the present RCT study were encouraging because it was the first study to recruit a clinical sample of individuals with depressive and anxiety disorders (who had a significant history of mental health difficulties), and demonstrate the efficacy of both the MEiCBT and the stand-alone mindfulness training delivered online. In particular, the RCT extended previous research by controlling for the role of non-specific factors, such as the structure and number of sessions, treatment duration, mode of delivery, as well as those present in face-to-face treatment, such as the role of an empathic therapist or mindfulness teacher, the interpersonal factors associated with session attendance, and the validating role of group members or group activities. Finally, the RCT provided evidence that these interventions can be offered to individuals with clinically diverse presentations, provided the clinicians guiding them through such treatments are adequately trained in assessment and treatment of mental disorders.

4.1. Limitations

The results of the present study should be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. First, the sample was comprised mostly of well-educated and motivated participants, and the majority met criteria for either GAD, MDD or SAD, despite recruitment being open to participants meeting criteria for any anxiety disorder and/or MDD. Most of the participants had tried mindfulness in the past (71.5%), and 83% reported a preference for the Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT program. It would be very difficult to find a sample who was naïve to both mindfulness and CBT strategies, especially given the popularity of mindfulness (Creswell, 2017). Nonetheless, sample selection bias may have influenced the findings. Together with the high rates of exclusion at application and interview this may have narrowed the profile of included participants and limits generalisability of the findings to other samples. Higher rates of attrition from the study and lower than expected adherence contributed to a substantial amount of missing data, which may have resulted in a selection bias towards a skewed sample and potential over-estimation of treatment effects. Because the study was only powered to detect a medium to large effects – which was sufficient to detect differences between interventions and usual care - the study lacked power to detect any differences between the three online interventions.

In addition, as outlined in our trial registration, we expected a medium difference between the Mindfulness-Enhanced iCBT program and the iCBT alone, based on the large effect sizes found in our pilot trial of the MEiCBT program. However, we acknowledge in hindsight that this expectation of a medium difference with an adjunctive intervention component was overly optimistic (Bell, Marcus & Goodlad, 2013). In addition, although we did not have any difficulties recruiting participants, the study was unfunded, and completed as part of the first author's dissertation project. Therefore, we had to stop recruitment due to restricted resources and time-frame. Another limitation was that the follow-up period (3 month follow-up) was relatively short for testing the long-term effects of the interventions, and we did not conduct diagnostic interviews at post-treatment. Finally, objective fidelity checks were not conducted on clinician phone calls resulting in the possibility of therapist allegiance effects and/or blending of therapies. Overall, replication of the present findings with larger, more demographically and clinically diverse samples, with the addition of fidelity checks and longer-term follow-up, as well as cost-effectiveness evaluation of these interventions, will be crucial in future research.

4.2. Conclusions

The results of the present study demonstrated that iCBT and the two new transdiagnostic programs for anxiety and depression – mindfulness-enhanced iCBT and internet-delivered mindfulness training – were more efficacious than usual care in reducing symptoms and associated functional impairment at post-treatment, with gains mostly maintained at 3-month follow-up. While these results remain preliminary and in need of replication in larger samples, it is encouraging that, for those who remain in treatment, structured internet-delivered cognitive behavioural and mindfulness-based treatment programs can lead to clinically significant improvements and diagnostic recovery with minimal clinician guidance. These findings add to the growing body of literature into transdiagnostic internet-delivered interventions, which have the capacity to increase access to efficient, affordable treatment.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was partially supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) and Medical Research Future Fund Fellowships awarded to Dr. Jill Newby (grant numbers: 1037787, 1145382), and by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship awarded to Natalie Kladnitski. The NHMRC and MRFF had no involvement in any aspect of the study, nor the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Random numbers were generated using www.random.org by a team member not involved in the study, and sealed in opaque envelopes. Allocation concealment was maintained until the applicant met inclusion criteria on the phone interview, at which point the interviewer opened the sealed envelope to reveal the study group.

Thirty two (20%) of the recorded interviews were then de-identified and rated by JN. Inter-rater reliability was excellent for MDD (k = 1.0), GAD (k = 1.0), PD (k = 0.91), Ag (k = 0.90), SAD (k = 0.92), and OCD (k = 0.89).

Additional measures of wellbeing, repetitive thinking, emotion regulation, experiential avoidance and mindfulness were also measured and will be reported in a separate study.

Missing Data Analysis. To test the missing at random assumption, participants with and without missing data were compared at post-treatment to explore whether there were group differences and whether baseline severity or demographic variables explained the missing data patterns. There were no differences between groups in the proportion of missing data at post-treatment. In addition, there were no significant differences between the sample who had complete data versus those with missing data in their age, gender, or baseline PHQ-9, K-10, or GAD-7 scores (ps > 0.05).

For PHQ-9, the RCI was calculated using the test-retest alpha of 0.84 (Kroenke et al., 2001) and the pre-treatment pooled standard deviation of 4.47 of the present sample. For GAD-7, the test-retest alpha of 0.83 (Spitzer et al., 2006) was used with the pre-treatment standard deviation of 5.1. Using these measures, a change of 4.96 points on the PHQ-9, and a change of 5.82 points on the GAD-7 was considered reliable change.

We administered process measures in this study; mediators of treatment effects will be reported in a separate paper.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2020.100310.

Contributor Information

Natalie Kladnitski, Email: n.kladnitski@unswalumni.com.

Mathew A. James, Email: mathew.james@health.nsw.gov.au.

Adrian R. Allen, Email: adrian@hydeparkcp.com.au.

Gavin Andrews, Email: gavina@unsw.edu.au.

Jill M. Newby, Email: j.newby@unsw.edu.au.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

CONSORT 2010 checklist

References

- Aldao A., Nolen-Hoeksema S. Specificity of cognitive emotion regulation strategies: a transdiagnostic examination. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010;48(10):974–983. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A., Nolen-Hoeksema S., Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010;30(2):217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Cuijpers P., Craske M.G., McEvoy P., Titov N. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Newby J.M., Williams A.D. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders is here to stay. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(1):533. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Newby J.M., Williams A.D. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders is here to stay. Current psychiatry reports. 2015;17(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Basu A., Cuijpers P., Craske M.G., McEvoy P., English C.L., Newby J.M. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: an updated meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer R.A. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003;10(2):125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Baer R.A. Mindfulness, assessment, and transdiagnostic processes. Psychol. Inq. 2007;18(4):238–242. [Google Scholar]

- Bell E.C., Marcus D.K., Goodlad J.K. Are the parts as good as the whole? A meta-analysis of component treatment studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(4):722–736. doi: 10.1037/a0033004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berking M., Wupperman P., Reichardt A., Pejic T., Dippel A., Znoj H. Emotion-regulation skills as a treatment target in psychotherapy. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008;46(11):1230–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berking M., Ebert D., Cuijpers P., Hofmann S.G. Emotion regulation skills training enhances the efficacy of inpatient cognitive behavioral therapy for major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2013;82(4):234–245. doi: 10.1159/000348448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher J., Åström V., Påhlsson D., Schenström O., Andersson G., Carlbring P. Internet-based mindfulness treatment for anxiety disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Ther. 2014;45(2):241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher J., Rozental A., Andersson G., Carlbring P. Side effects in internet-based interventions for social anxiety disorder. Internet Interv. 2014;1(1):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Brown T.A., Barlow D.H. Oxford University Press; USA: 2014. Anxiety and Related Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-5 (ADIS-5) - Adult Version. [Google Scholar]

- Brown K.W., Ryan R.M., Creswell J.D. Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychol. Inq. 2007;18(4):211–237. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R., Gullone E., Allen N.B. Mindful emotion regulation: an integrative review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009;29(6):560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla N., Ostafin B. Experiential avoidance as a functional dimensional approach to psychopathology: an empirical review. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007;63(9):871–890. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.D. Mindfulness interventions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2017;68:491–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear B., Staples L., Terides M., Karin E., Zou J., Johnston L., McEvoy P. Transdiagnostic versus disorder-specific and clinician-guided versus self-guided internet-delivered treatment for generalized anxiety disorder and comorbid disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2015;36:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilly G.J., Borkovec T.D. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 2000;31(2):73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T., Watkins E.R. Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2008;1(3):192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes P. The therapist as a vital factor in side-effects of psychotherapy. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2010;44(2):189. doi: 10.3109/00048670903487274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friborg O., Johnsen T.J. 2017. The Effect of Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy as an Antidepressive Treatment Is Falling: Reply to Ljòtsson Et al.(2017) and Cristea Et al.(2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabovac A.D., Lau M.A., Willett B.R. Mechanisms of mindfulness: a Buddhist psychological model. Mindfulness. 2011;2(3):154–166. [Google Scholar]

- Gu J., Strauss C., Bond R., Cavanagh K. 2016. “ how Do Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Improve Mental Health and Wellbeing? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Mediation Studies”: Corrigendum. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Schneider L.H., Edmonds M., Karin E., Nugent M.N., Dirkse D., Titov N. Randomized controlled trial of internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy comparing standard weekly versus optional weekly therapist support. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2017;52:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M. G., Hobbs, M. J., Burgess, P. M., Pirkis, J. E., Diminic, S., Siskind, D. J., Whiteford, H. A. (2015). Frequency and quality of mental health treatment for affective and anxiety disorders among Australian adults. Med. J. Aust., 202(4), 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Harvey A.G., Watkins E., Mansell W., Shafran R. Oxford University Press; USA: 2004. Cognitive Behavioural Processes across Psychological Disorders: A Transdiagnostic Approach to Research and Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C., Wilson K.G., Gifford E.V., Follette V.M., Strosahl K. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: a functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996;64(6):1152. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S.G., Asmundson G.J. Acceptance and mindfulness-based therapy: new wave or old hat? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008;28(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S.G., Sawyer A.T., Witt A.A., Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010;78(2):169. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N.S., Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991;59(1):12. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen T.J., Friborg O. The effects of cognitive behavioral therapy as an anti-depressive treatment is falling: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015;141(4):747. doi: 10.1037/bul0000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L., Titov N., Andrews G., Spence J., Dear B.F. A RCT of a transdiagnostic internet-delivered treatment for three anxiety disorders: examination of support roles and disorder-specific outcomes. PLoS One. 2011;6(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L., Titov N., Andrews G., Dear B.F., Spence J. Comorbidity and internet-delivered transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2013 doi: 10.1080/16506073.2012.753108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 1982;4(1):33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003;10(2):144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Hachette UK; 2013. Full Catastrophe Living, Revised Edition: How to Cope with Stress, Pain and Illness Using Mindfulness Meditation. [Google Scholar]

- Keng S.-L., Smoski M.J., Robins C.J. Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011;31(6):1041–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R., Andrews, G., Colpe, L., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D., Normand, S., Zaslavsky, A. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. J. Res. Psychiatry Allied Sci., 32(6), 959–976. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kingston T., Dooley B., Bates A., Lawlor E., Malone K. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for residual depressive symptoms. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2007;80(2):193–203. doi: 10.1348/147608306X116016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kladnitski N., Smith J., Allen A., Andrews G., Newby J.M. Online mindfulness-enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety and depression: outcomes of a pilot trial. Internet Interv. 2018;13:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R., Williams J. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krusche A., Cyhlarova E., Williams J.M.G. Mindfulness online: an evaluation of the feasibility of a web-based mindfulness course for stress, anxiety and depression. BMJ Open. 2013;3(11) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A.J. What mindfulness brings to psychotherapy for anxiety and depression. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30(5):409–412. doi: 10.1002/da.22081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBeau R.T., Davies C.D., Culver N.C., Craske M.G. Homework compliance counts in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2013;42(3):171–179. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2013.763286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt G.A., Kristeller J.L. 1999. Mindfulness and Meditation. [Google Scholar]